1. Introduction

Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are

among the most prevalent metabolic disorders worldwide, posing major health and

socioeconomic challenges. According to the World Health Organization, in 2022

890 million adults were obese and 830 million were living with diabetes,

figures that continue to rise sharply due to sedentary lifestyles,

urbanization, and changes in dietary patterns [

1].

Both conditions are closely interrelated: excess adiposity contributes to

insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and dysregulated glucose metabolism,

while hyperinsulinemia and impaired satiety signaling further exacerbate weight

gain. Together, obesity and T2DM significantly increase the risk of

cardiovascular disease, hepatic steatosis, and premature mortality, representing

a global epidemic that demands more effective and sustainable therapeutic

solutions.

Incretins are peptide hormones released from the

gut shortly after a meal—specifically GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) and GIP

(glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide). Their main action is to

stimulate the release of insulin from the pancreas in a glucose-dependent

manner. They act quickly (within minutes of food intake) and help regulate

blood glucose levels [

2].

GLP-1 and GIP bind to their respective receptors,

GLP-1R and GIPR, which are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Upon ligand

binding, the receptors undergo conformational changes, which enable them to

activate G proteins (in particular, G_s). This leads to cAMP production as a

second messenger, and downstream signaling pathways.

Different tissues express these receptors, so the

effects of incretins vary: in the pancreas, they encourage insulin secretion,

in the brain, GLP-1 can promote satiety (feeling of fullness), in the

gastrointestinal tract, GLP-1 slows gastric motility (delays how quickly food

leaves the stomach) [

3]. The active half-life

of GLP-1 and GIP is short (minutes): they are degraded rapidly by the enzyme

dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) [

4].

Because incretins influence glucose regulation,

they are of great interest in diabetes research and therapeutics. The

structural and mechanistic understanding of how GLP-1, GIP, and related

agonists bind and activate their receptors aids in drug development (designing

stable, potent agonists). Synthetical peptides that mimic the action of GLP-1

are called GLP-1 agonists.

Over the past decade, major advances in metabolic

pharmacotherapy have focused on modulating the

incretin system.

Synthetic

GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) such as liraglutide,

semaglutide, and the dual GLP-1/GIP agonist tirzepatide have revolutionized the

management of diabetes and obesity [

3,

5].

Clinical trials have demonstrated not only improved glycemic control but also

significant body-weight reduction and cardiovascular benefits. Despite their

success, these drugs have important limitations: they are typically injectable

peptides requiring cold-chain storage, their cost restricts accessibility, and

many patients experience gastrointestinal side effects or poor long-term

adherence. Consequently, there is growing interest in identifying

non-peptidic,

orally active compounds capable of modulating the incretin axis with

improved tolerability and affordability.

Plants represent a vast and chemically diverse

source of bioactive molecules—

phytocompounds—that may influence glucose

and energy metabolism through mechanisms similar to synthetic incretin mimetics

[

6]. Natural alkaloids, flavonoids,

terpenoids, and phenolic acids have been shown to stimulate GLP-1 secretion,

inhibit the enzyme

dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) responsible for

incretin degradation, and improve insulin sensitivity. For example, berberine,

quercetin, and ginsenosides display promising metabolic effects in preclinical

studies [

7]. However, most phytocompounds have

not advanced to clinical application because of

poor bioavailability, rapid

metabolism, low receptor specificity, and lack of mechanistic understanding.

Experimental screening of thousands of plant metabolites is time-consuming,

costly, and often limited by compound instability and complex matrices.

To address these challenges, in silico

methodologies—including molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations,

and quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) modeling—have emerged

as powerful tools for exploring phytochemical interactions with metabolic

targets at the atomic level. These computational approaches allow researchers

to rapidly predict binding affinity, stability, and selectivity of natural

molecules toward receptors such as GLP-1R, GIPR, and DPP-4, long before

laboratory testing. Combined with pharmacokinetic modeling and machine learning-based

ADMET prediction, in silico studies can prioritize the most promising

candidates, reducing the number of experimental assays needed and guiding

formulation strategies to overcome absorption and stability barriers.

By integrating traditional natural-product

chemistry with modern computational pharmacology,

in silico screening

enables a rational, mechanism-driven exploration of the therapeutic potential

of phytocompounds [

8]. This approach not only

accelerates the identification of bioactive leads but also deepens

understanding of their structure–activity relationships and potential

synergistic effects. Ultimately, such strategies could lead to the development

of safe, affordable, and orally available

plant-derived incretin modulators,

offering a complementary path to the peptide-based therapies that currently

dominate diabetes and obesity management.

To the best of the author’s knowledge, this is the

first in silico study to analyse phytocompounds’ affinity to GLP-1R,

GIPR, and DPP-4 (testing of dualist/ triple action), as well as

pharmacokinetics, and it may provide valuable insights towards developing

natural and affordable alternatives for obesity and M2DL treatment. The purpose

of the study was not just to assess phytochemicals’ potential as incretin

agonists, but also to compare their affinity to receptors to those of synthetic

oral drugs that are currently in advanced clinical trials.

2. Results

2.1. Literature Review

The preliminary literature review identified a large number a scientific publications focusing on phytochemicals used in the treatment of diabetes and metabolic disorders.

One of the most studied phytochemical for diabetes treatment is

berberine, with ~47,000 search results in Google Scholar for “berberine + diabetes” and over 5,000 results for “berberine + GLP-1”. It was used traditionally in treatment of gastrointestinal conditions and has clinically demonstrated effects in lowering blood glucose [

9]. Coffee (

chlorogenic acid) and green tea (

epigallocatechin gallate) were widely proven to be associated with reduced risk of diabetes [

10], while

curcumin is also associated with anti-obesity effects [

11].

Hesperidin has proven GLP-1R activity [

12], as well as

quercetin and

rutin, which are incretin modulators [

13,

14]. They were all selected because they are present in staple foods, extracts being often included in diabetes and weight management supplements, have been subject to in vitro and in vivo clinical studies, but their profile as potential triple agonists was not yet investigated.

The molecules selected for the present

in silico study are presented in

Table 1.

Berberine

Berberine is an isoquinoline alkaloid found primarily in

Berberis species such as

Berberis vulgaris and

Coptis chinensis. Chemically, it consists of a quaternary ammonium salt structure conferring high polarity and limited oral bioavailability [

38]. Traditionally, berberine-containing plants have been used in Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine for treating gastrointestinal (GI) infections, diabetes, and inflammatory disorders [

39]. Modern pharmacological research demonstrates pleiotropic effects through activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), modulation of lipid and glucose metabolism, and anti-inflammatory signaling. Meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials report clinically relevant reductions in fasting glucose, HbA1c, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol, with magnitude comparable to that of metformin in some short-term studies. Its inclusion in the present study is justified by consistent evidence of metabolic and endothelial benefits, as well as its well-characterized molecular mechanisms relevant to insulin resistance and dyslipidemia.

Chlorogenic Acid

Chlorogenic acid (CGA) is an ester of caffeic acid and quinic acid abundant in coffee beans, artichokes, apples, and many other plant foods. It is a major phenolic acid responsible for the antioxidant and modulating effects of coffee consumption. Traditionally, CGA-rich preparations, such as green coffee infusions, have been used as tonics to promote metabolism and vascular health [

40]. Experimental and clinical research indicates that CGA can inhibit glucose absorption, enhance endothelial nitric oxide synthesis, and exert anti-hypertensive and anti-inflammatory effects. Randomized controlled trials using green coffee extract standardized for CGA (typically 300–800 mg/day) demonstrate modest reductions in blood pressure and fasting glucose. The compound’s inclusion in this study is motivated by its reported effects on weight loss [

18].

Curcumin

Curcumin is the principal curcuminoid of

Curcuma longa (turmeric), chemically characterized as a diarylheptanoid polyphenol with conjugated double bonds responsible for its intense yellow color and radical-scavenging activity. Traditionally employed in Ayurvedic and Southeast Asian medicine as an anti-inflammatory and digestive remedy, curcumin has since been extensively studied for its ability to modulate transcription factors such as NF-κB and Nrf2. Numerous clinical trials and meta-analyses have demonstrated that curcumin supplementation (often 500–2000 mg/day in bioenhanced forms) reduces inflammatory markers (CRP, IL-6, TNF-α), improves lipid profiles, and may alleviate symptoms in arthritis, metabolic syndrome, and gastrointestinal inflammation [

41]. Its limited oral bioavailability has spurred the development of phytosomal and nanoparticle formulations. Curcumin was selected for the present study for its potential as anti-obesity treatment.

Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG)

Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) is the most abundant catechin in green tea (

Camellia sinensis), chemically belonging to the flavan-3-ols with a gallate ester conferring strong antioxidant potential. Traditionally, green tea has been consumed in East Asian cultures for detoxification, alertness, and longevity. EGCG exhibits multiple bioactivities, including modulation of cellular redox status, inhibition of pro-inflammatory enzymes, and regulation of lipid metabolism and insulin signaling [

42]. Clinical studies indicate that EGCG or standardized green tea extracts may modestly reduce fasting glucose, body weight, and systolic blood pressure, while contributing to improved endothelial function [

43]. Additionally, EGCG has been investigated as an adjunct in cancer chemoprevention and neuroprotection. It was included in this study because of its well-established safety at dietary doses and its potential applications in diabetes treatment.

Hesperidin

Hesperidin is a citrus flavanone glycoside predominantly found in orange and lemon peels. Upon ingestion, it is hydrolyzed to hesperetin, its active aglycone. Traditionally, citrus flavonoids have been used to strengthen capillaries and treat venous insufficiency [

44]. Chemically, hesperidin’s structure supports free-radical scavenging and modulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Clinical studies report that hesperidin supplementation (typically 500–1000 mg/day) can improve flow-mediated dilation, reduce blood pressure, and attenuate markers of oxidative stress and inflammation, although effects on glycemic indices are inconsistent. Recent studies have indicated it’s potential in the treatment of diabetes, which is why it was included in the study.

Quercetin

Quercetin is a flavonol widely distributed in onions, apples, berries, and leafy vegetables. Its planar polyphenolic structure enables chelation of metal ions and potent antioxidant activity. Historically, quercetin-rich foods have been valued in traditional European and Asian diets for their anti-inflammatory and tonic effects [

45]. Modern mechanistic studies reveal that quercetin modulates cytokine production, inhibits cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase enzymes, and supports mitochondrial antioxidant defenses. Randomized trials and meta-analyses show modest but significant reductions in blood pressure and C-reactive protein at doses of 500–1000 mg/day, as well as possible antiviral and immunomodulatory effects. The compound was selected for its potential role in incretins modulation.

Rutin

Rutin (quercetin-3-rutinoside) is a glycoside of quercetin found in buckwheat, citrus fruits, and some medicinal herbs. The attached disaccharide (rutinose) enhances water solubility but reduces direct bioavailability until enzymatic hydrolysis in the gut. Traditionally, rutin-rich preparations have been used as vascular tonics and anti-hemorrhoidal remedies. Pharmacologically, rutin exhibits antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and capillary-stabilizing effects, improving microcirculatory integrity [

46]. Preclinical and limited clinical studies indicate benefits for lipid metabolism, venous insufficiency, and wound healing. The inclusion of rutin in this study provides a glycosylated flavonol counterpart to quercetin, allowing comparison of structure–activity relationships and exploration of how sugar conjugation affects molecular affinities, absorption and biological efficacy.

Synthetic Drug Orforglipron

Orforglipron is a novel oral medication being developed primarily for weight loss and type 2 diabetes management. It belongs to the class of GLP-1 receptor agonists, which help regulate blood sugar, appetite, and body weight by mimicking the natural hormone GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) [

47,

48]. Unlike most GLP-1 drugs, orforglipron is not a peptide but a small molecule, allowing effective oral absorption rather than requiring injection. It was included in the study for the purpose of comparison with natural phytocompounds in terms of molecular affinity to receptors and pharmacokinetics.

2.2. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking simulations revealed distinct binding affinity profiles for the investigated natural compounds toward

GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R),

GIP receptor (GIPR), and

dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) (

Table 1). The synthetic GLP-1R agonist

orforglipron, included as a reference ligand, exhibited the highest binding affinities across all three targets (–11.4 kcal/mol for GLP-1R, –7.6 kcal/mol for GIPR, –9.8 kcal/mol for DPP4), consistent with its optimized molecular design for receptor engagement and enzymatic stability (

Table 2). Detailed results, including image captures of ligands bound to receptor can be found in the

Supplementary Materials.

Among the natural compounds, hesperidin and rutin displayed the strongest binding to GLP-1R (both –9.2 kcal/mol), comparable in magnitude to the synthetic agonist’s affinity and notably stronger than other polyphenols. Both are glycosylated flavonoids whose bulky sugar moieties may facilitate hydrogen bonding with polar residues in the receptor’s extracellular domain. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) also showed a strong interaction (–9.1 kcal/mol), reflecting its polyhydroxylated catechin structure capable of multiple hydrogen bonds and π–π stacking interactions. These results suggest that complex flavonoids and catechins may stabilize the GLP-1R binding pocket despite lacking classical peptide-like motifs.

Berberine, chlorogenic acid, curcumin, and quercetin exhibited moderate GLP-1R binding (–7.5 to –7.9 kcal/mol). Their planar or semi-planar structures allow interaction within the hydrophobic cavity but with fewer anchoring polar contacts than seen in glycosides. The relatively strong affinity of berberine (–7.6 kcal/mol) may arise from its cationic isoquinoline ring, which can engage in electrostatic interactions with acidic residues of the receptor.

Affinity for GIPR was generally weaker across all natural ligands, ranging from –4.3 to –5.8 kcal/mol. This suggests lower complementarity between polyphenolic scaffolds and the GIPR binding site, which is structurally narrower and more peptide-selective. Only hesperidin (–5.8 kcal/mol) showed slightly higher affinity, possibly due to its extended conformation and hydrogen bonding potential.

Docking against DPP4, the enzyme responsible for incretin degradation, revealed affinities from –6.8 to –8.3 kcal/mol among natural compounds. Hesperidin again ranked highest (–8.3 kcal/mol), followed by berberine and rutin (–8.0 kcal/mol), and EGCG (–7.9 kcal/mol). These results align with prior evidence that flavonoids and alkaloids may inhibit DPP4 activity through interactions with catalytic site residues (e.g., Glu205, Glu206, Tyr547). Curcumin, quercetin, and chlorogenic acid displayed moderate inhibition potential (–6.8 to –7.5 kcal/mol), which could still contribute to overall incretin preservation in vivo.

Taken together, the docking data indicate that hesperidin, rutin, and EGCG are the most promising natural candidates for GLP-1R activation or modulation, while berberine and hesperidin appear strongest as potential DPP4 inhibitors. Although none matched the synthetic agonist’s binding energy, several compounds displayed affinities within a pharmacologically relevant range (–7 to –9 kcal/mol), supporting their inclusion as bioactive leads in studies targeting the incretin axis. These findings corroborate existing experimental literature suggesting that polyphenols and isoquinoline alkaloids may enhance incretin signaling and glucose homeostasis via multitarget interactions.

2.2. ADME Profiles

A synthesis of the ADME analysis is presented in

Table 3.

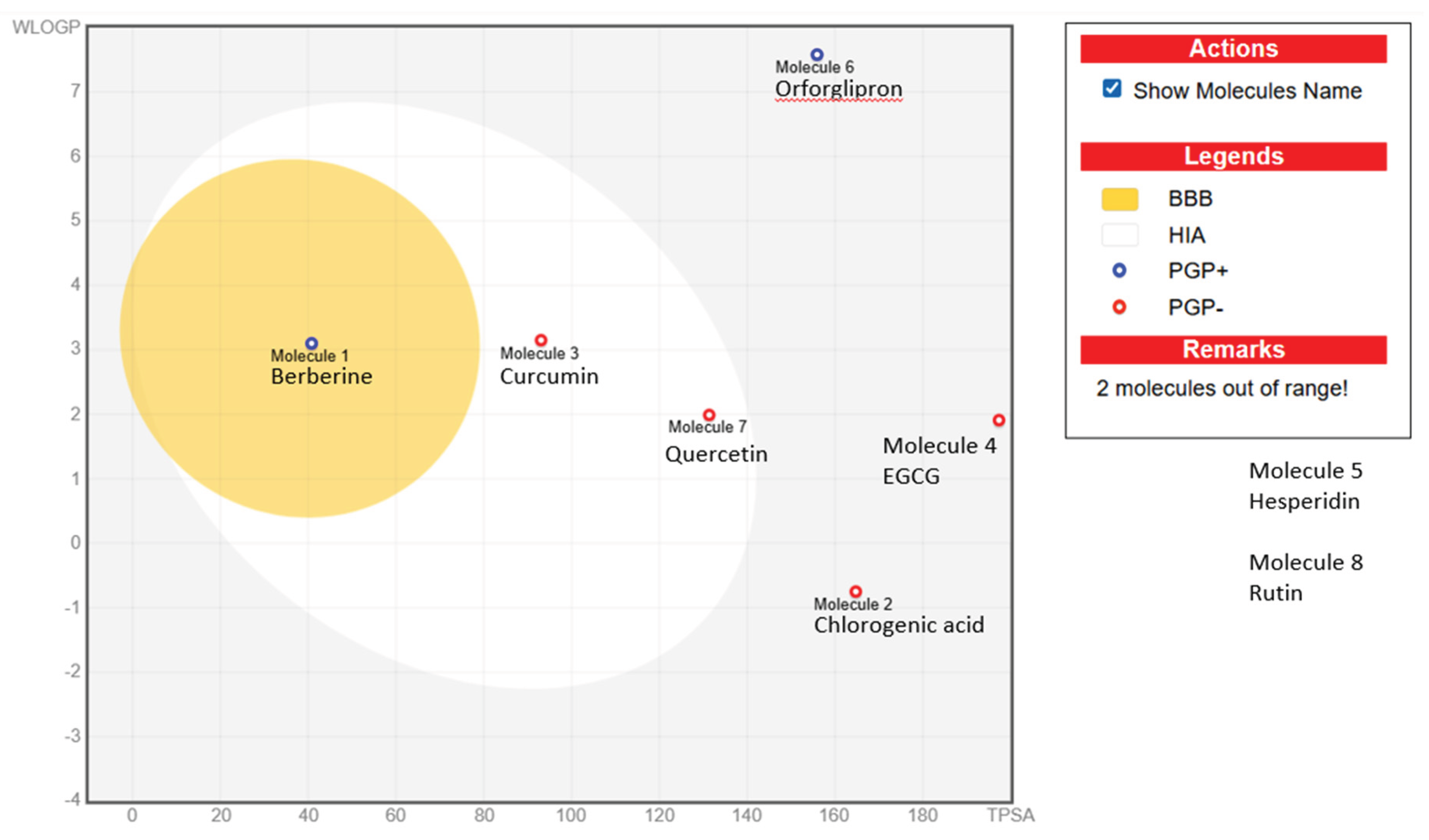

The BOILED-Egg diagram (

Figure 1) visually predicts intestinal absorption and blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability of the selected molecules using two parameters: WLOGP (lipophilicity, y-axis) and TPSA (topological polar surface area, x-axis). Molecules located in the white region are predicted to have high human intestinal absorption (HIA), while those within the yellow region (the “yolk”) are likely to penetrate the BBB. The blue and red circles indicate the interaction with P-glycoprotein (P-gp), a transporter that actively expels compounds from cells: PGP+ (blue) denotes predicted substrates that may be pumped out, reducing absorption or brain exposure, whereas PGP− (red) indicates non-substrates with potentially higher permeability. In this figure, berberine (PGP+) appears inside the BBB-permeant zone, suggesting possible brain penetration, while most phytochemicals—curcumin, quercetin, chlorogenic acid, and EGCG—fall in or near the white area, indicating good intestinal absorption but limited BBB access. Hesperidin and rutin, positioned outside the main zones, show poor absorption due to their large size and high polarity, consistent with their glycosidic structures.

3. Discussion

The physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of eight selected compounds—berberine, chlorogenic acid, curcumin, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), hesperidin, orforglipron, quercetin, and rutin—were evaluated using the SwissADME web platform to assess their potential as orally active agents targeting metabolic pathways related to diabetes and obesity. The results revealed considerable variation in molecular weight, lipophilicity, polarity, and bioavailability among the compounds.

Berberine, curcumin, and quercetin have molecular weights below 400 g/mol and moderate lipophilicity (consensus Log P between 2 and 3), values consistent with classical drug-likeness criteria. These parameters suggest adequate balance between solubility and membrane permeability, supporting their potential for oral administration. In contrast, chlorogenic acid, EGCG, hesperidin, and rutin displayed high polarity and large polar surface areas (TPSA values >160 Ų), together with negative or near-zero lipophilicity, indicating a low likelihood of passive diffusion through lipid membranes. Orforglipron, although a proven orally active GLP-1 receptor agonist, strongly violated Lipinski’s and Veber’s rules due to its large size (883 g/mol) and high lipophilicity (Log P 6.5), emphasizing that the effectiveness of such molecules arises from targeted molecular design and formulation optimization rather than intrinsic physicochemical suitability.

Predicted gastrointestinal absorption followed a similar trend. High intestinal absorption was observed for berberine, curcumin, and quercetin, while chlorogenic acid, EGCG, hesperidin, and rutin were classified as poorly absorbed. The BOILED-Egg model [

50] indicated that berberine was capable of both intestinal and blood–brain barrier permeation, whereas the highly polar flavonoid glycosides are not likely to be assimilated through the GI tract. Bioavailability scores further supported these findings, with berberine, curcumin, and quercetin achieving a score of 0.55 (moderate oral bioavailability), in contrast to the lower scores (0.11–0.17) for the hydrophilic and glycosylated flavonoids. These differences reflect the significant influence of sugar moieties on absorption: removal of glycosidic groups (e.g., conversion of rutin to quercetin, or hesperidin to hesperetin) is expected to markedly improve permeability. However, the molecular docking results showed that quercetin has lower affinity to receptors compared to rutin.

Analysis of cytochrome P450 (CYP) inhibition patterns revealed that berberine, curcumin, and quercetin act as inhibitors of multiple CYP isoenzymes, particularly CYP3A4, CYP2D6, and CYP1A2, suggesting potential for pharmacokinetic interactions with co-administered drugs. However, this property may also confer extended metabolic lifetime. The remaining polyphenols showed little or no predicted CYP inhibition, which implies a safer metabolic profile but possibly shorter systemic exposure. Solubility predictions placed most compounds in the “moderately soluble” to “soluble” range, except for orforglipron, which was classified as poorly soluble despite its therapeutic efficacy.

From a drug-likeness perspective, berberine, curcumin, and quercetin meet major criteria, including Lipinski, Ghose, Egan, and Muegge, and demonstrated low synthetic complexity (synthetic accessibility <3.5). Hesperidin, rutin, and EGCG failed multiple rules owing to their size, polarity, and hydrogen-bonding capacity, resulting in high synthetic accessibility scores (>6). Although orforglipron also violated several drug-likeness rules, its established oral activity highlights the potential of modern medicinal chemistry to overcome such constraints through structural and formulation engineering.

Overall, the in silico ADME analysis identified berberine, curcumin, and quercetin as the most promising phytochemical scaffolds for further development. These compounds combine favorable oral absorption, manageable polarity, and chemical simplicity with known biological activity on metabolic pathways. Conversely, the glycosylated flavonoids (hesperidin, rutin) and polyphenolic acids (chlorogenic acid, EGCG) exhibited poor pharmacokinetic characteristics that may limit their direct use but could be improved through deglycosylation, nanoencapsulation, or prodrug design. Together, these results emphasize the importance of computational pharmacokinetic screening as an initial filter for prioritizing natural compounds in drug discovery pipelines focused on incretin-based mechanisms and metabolic regulation.

Further studies are needed to evaluate the receptor specificity and selectivity of target molecules, their metabolic pathways, as well as ways of increasing their half-life and bioavailability, eventually through alternative delivery methods.

4. Materials and Methods

Literature Review

A scientific literature search was carried out in order to identify compounds of plant origin that have been tested for their activity in treatment of obesity and T2DM, including interactions with GLP-1R, GIPR and/ or DPP4. Searches were done in Google Scholar, ScienceDirect and Scopus databases, as well as using AI tools like Perplexity. Search included phrases like “phytochemicals GLP-1”, “phytochemicals diabetes”, phytochemicals DPP4” as well as individual names of identified compounds. The inclusion criterion was the existence of in vitro or in vivo trials indicating potential in treatment of obesity and/or diabetes. Further criteria were the number of studies, demonstrated effects of treating diabetes or weight management in humans and identification of active compound.

Molecular Structures

Molecular structures for the selected compounds were retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB), isolated from existing complexes and saved as individual .pdb files. In case no .pdb structure was available (e.g. for hesperidin), the 3D structure was downloaded from the PubChem database [

51] in .sdf format and converted to .pdb in Chimera [

52]. An overview of compounds and the IDs of the complexes they were separated from, respectively CID from PubChem, are presented in

Table 4.

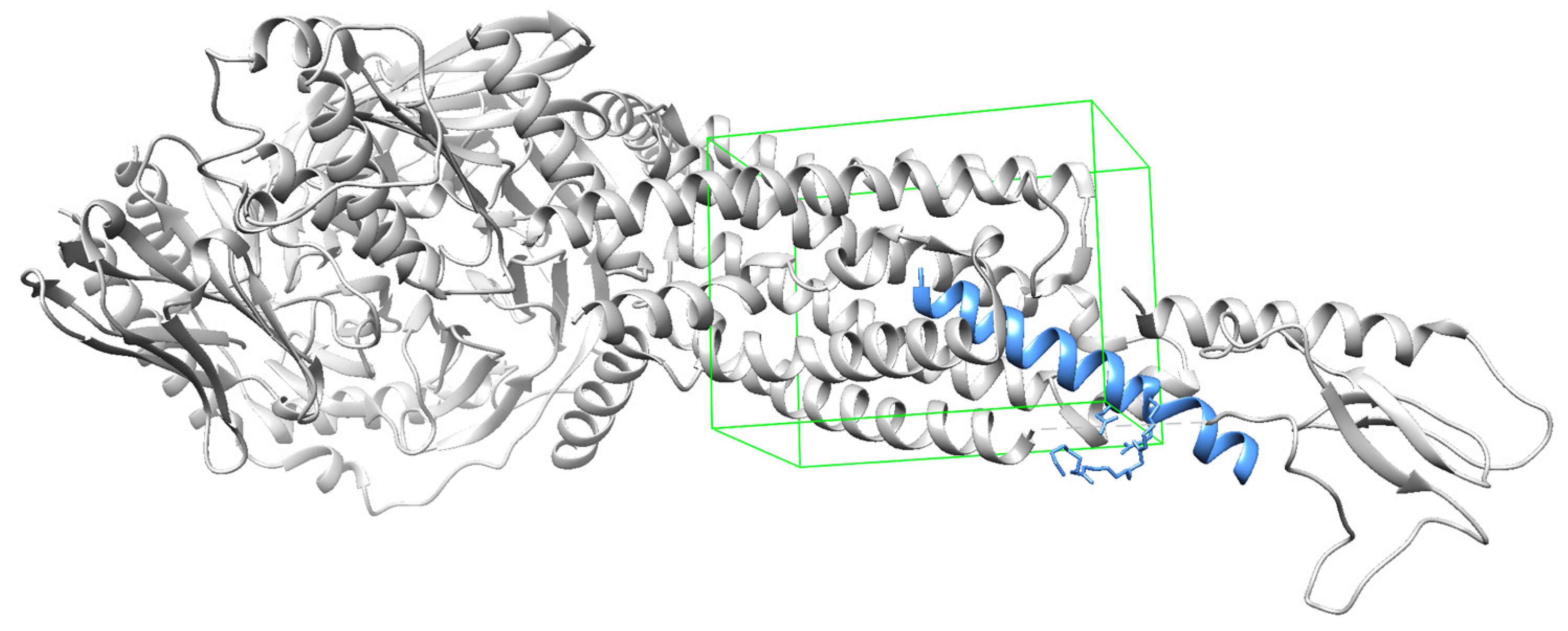

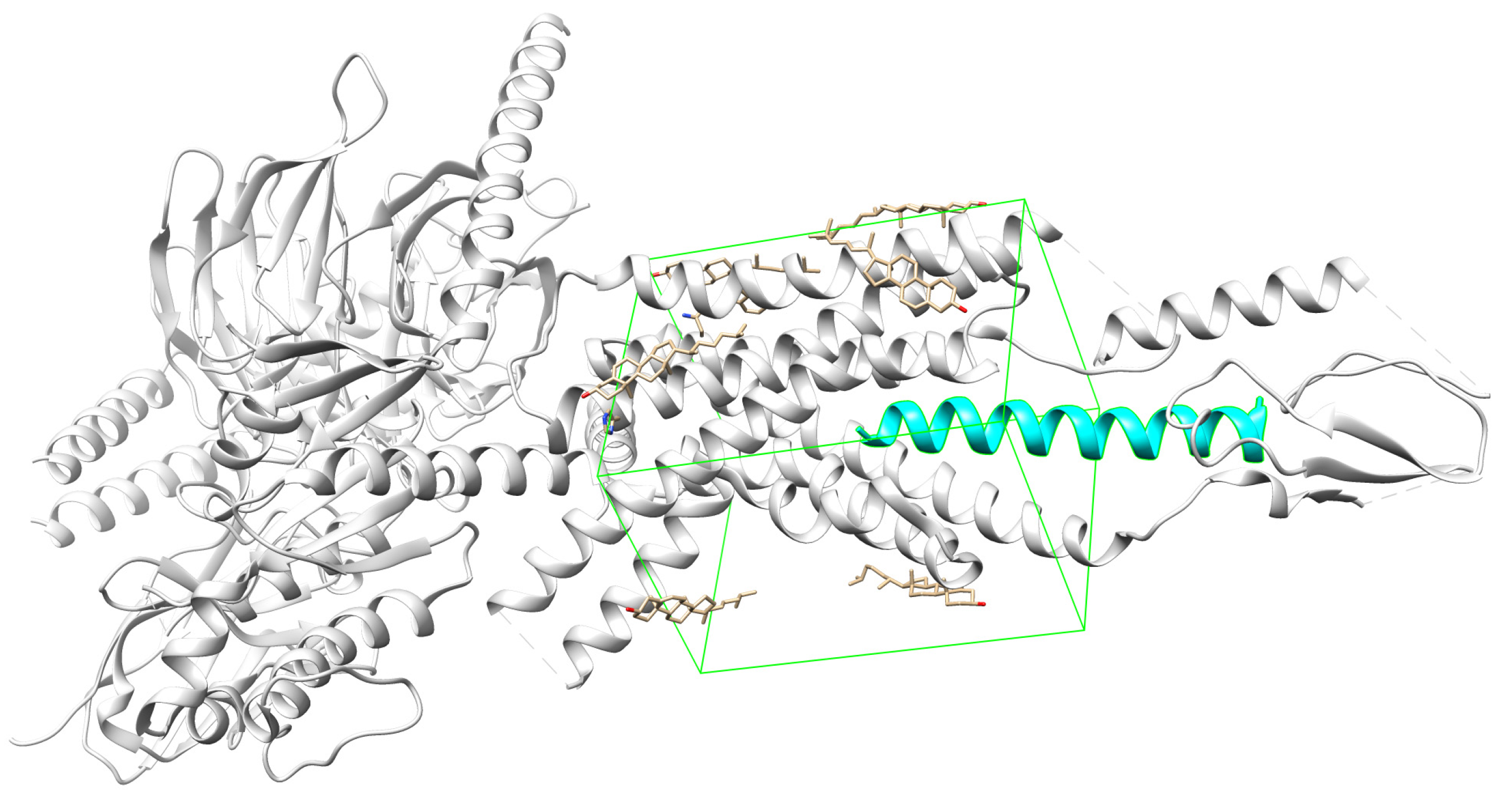

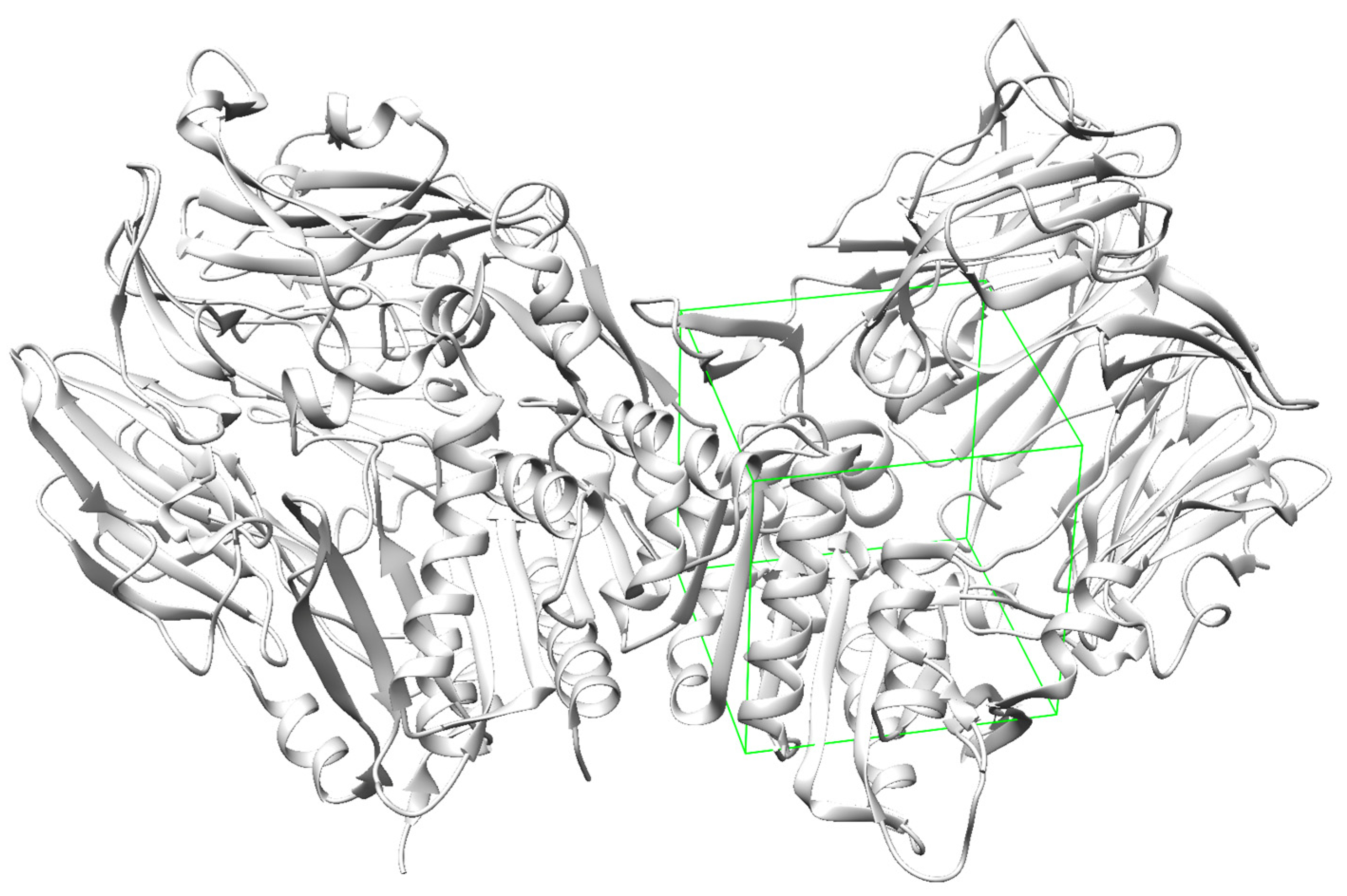

Molecular Docking

The docking sites for each receptor were defined according to existing complexes, namely semaglutide bound to GLP-1R (

Figure 2), tirzepatide bound to GIPR (

Figure 3), and DPP4 bound to a ligand 34a (

Figure 4). The docking sites are represented with green wire boxes in the figures.

Molecules preparation for docking included removal of water, adding hydrogens and adding charges. All molecular processing was carried out in UCSF Chimera software version 1.19 [

52], while the actual molecular docking calculations used Autodock Vina 4.2 [

63], called from Chimera module.

ADME Profile

An ADME profile describes how a compound is Absorbed, Distributed, Metabolized, and Excreted by the body, offering a snapshot of its pharmacokinetic behavior and drug-likeness. It can be rapidly estimated in the early stages of drug discovery using free

in-silico platforms such as SwissADME [

49], which predicts key properties like gastrointestinal absorption, blood–brain barrier penetration, lipophilicity (LogP), solubility, metabolic interactions (e.g., CYP450 inhibition), P-glycoprotein substrate status, and medicinal chemistry filters (Lipinski, Veber, etc.).

An overview of the ADME profile in presented in

Table 5.

By inputting a SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) string or drawing the molecule, SwissADME automatically runs computational models to generate a predictive ADME report, enabling researchers to screen candidate compounds efficiently before moving to experimental testing.

The SMILES strings of the selected compounds were retrieved from the PubChem database and submitted to the SwissADME online tool, which returned the ADME profile of each compound (

Table 6).

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

AI was used to search and analyse published articles and research results and to summarise findings. Main AI platforms used were perplexity.ai and chatgpt.com.

5. Conclusions

Among the tested compounds, Berberine, Curcumin, and Quercetin show the most favorable in silico pharmacokinetic profiles and drug-likeness. Their properties suggest potential for oral delivery after optimisation, however, molecular docking did not reveal any particular affinity of these compounds to the target receptors.

Docking analyses revealed that several phytochemicals can interact strongly with incretin-related targets, with hesperidin, rutin, and epigallocatechin gallate demonstrating high affinity for GLP-1R and hesperidin also binding effectively to DPP-4. These findings suggest that certain flavonoids may act as dual modulators of incretin signaling—combining receptor engagement with enzyme inhibition. However, their pharmacological translation is limited by unfavorable physicochemical properties. In contrast, berberine showed moderate affinity but better predicted absorption and metabolic stability, making it a more practical scaffold for optimization.

Further studies are needed to assess the selectivity and specificity of molecular affinities between receptors and ligands, as well as improving the bioavailability and extending the half-life of bioactive compounds.

Overall, this analysis demonstrates how in silico molecular docking and ADME modeling can effectively guide the selection and rational design of natural compounds targeting GLP-1, GIP, and DPP-4 pathways for obesity and diabetes management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All results of the study are included in the supplementary materials.

Acknowledgments

Molecular graphics and analyses performed with UCSF Chimera, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, with support from NIH P41-GM103311.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADME |

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion; the four key pharmacokinetic processes determining how a compound behaves in the body |

| AGI |

Alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitor; a type of antidiabetic compound that slows carbohydrate digestion in the gut |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AMPK |

Alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitor; a type of antidiabetic compound that slows carbohydrate digestion in the gut |

| BBB |

Blood–Brain Barrier; a selective barrier between the bloodstream and brain tissue that restricts the passage of many molecules |

| BOILED-Egg model |

Brain Or IntestinaL EstimateD permeation method; a visual predictor of gastrointestinal absorption and blood–brain barrier permeability used in SwissADME |

| CNS |

Central Nervous System; includes the brain and spinal cord |

| CYP |

Cytochrome P450; a family of liver enzymes responsible for metabolizing

many drugs |

| DPP-4 |

Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4; an enzyme that degrades incretin hormones such as GLP-1 and GIP |

| EC50 |

Half Maximal Effective Concentration; the concentration of a compound that produces 50% of its maximal effect |

| EGCG |

Epigallocatechin Gallate; a bioactive polyphenol found in green tea |

| GI |

Gastro-Intestinal |

| GIP |

Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide; an incretin hormone that stimulates insulin release in response to food intake |

| GIPR |

Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide Receptor; the receptor that binds GIP |

| GLP-1 |

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1; an incretin hormone involved in glucose metabolism and appetite regulation |

| GLP-1R |

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor; the receptor that mediates the effects of GLP-1 |

| HIA |

Human Intestinal Absorption |

| Log P |

Partition Coefficient; a measure of a compound’s lipophilicity or its tendency to dissolve in fats versus water |

| PGP+ |

P-glycoprotein Substrate (Yes) |

| PGP− |

P-glycoprotein Non-Substrate (No) |

| PK |

Pharmacokinetics; the study of how a compound is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted by the body |

| SwissADME |

Swiss Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion; a web tool for predicting pharmacokinetic and drug-likeness properties of small molecules |

| T2DM |

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; a metabolic disorder characterized by insulin resistance and high blood glucose |

| TEER |

Transepithelial Electrical Resistance; a measure of the integrity of cell layer barriers, such as intestinal or epithelial monolayers |

| TPSA |

Topological Polar Surface Area |

| WLOGP |

Wildman–Crippen LogP |

References

- World Health Organisation Obesity and overweight Available online:. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D.J. GLP-1-based therapies for diabetes, obesity and beyond. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2025, 24, 631–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.; Lee, E.-J.; Ahmad, K.; Ahmad, S.-S.; Lim, J.-H.; Choi, I. A Comprehensive Review and Perspective on Natural Sources as Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors for Management of Diabetes. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokary, S.; Bawadi, H. The promise of tirzepatide: A narrative review of metabolic benefits. Prim. Care Diabetes 2025, 19, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, P.; Hannon-Fletcher, M.P.; Flatt, P.R.; Abdel-Wahab, Y.H.A. Effects of 22 traditional anti-diabetic medicinal plants on DPP-IV enzyme activity and glucose homeostasis in high-fat fed obese diabetic rats. Biosci. Rep. 2021, 41, BSR20203824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiola, J.O.; Oluyemi, A.A.; Idowu, O.T.; Oyinloye, O.M.; Ubah, C.S.; Owolabi, O.V.; Somade, O.T.; Onikanni, S.A.; Ajiboye, B.O.; Osunsanmi, F.O.; et al. Potential Role of Phytochemicals as Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptor (GLP-1R) Agonists in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, A.; Daniel, K.; Patel, A.M. In-silico Exploration of Phytoconstituents of Gymnema sylvestre as PotentialGlucokinase Activators and DPP-IV Inhibitors for the Future Synthesisof Silver Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Curr. Enzyme Inhib. 2022, 18, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Yang, H.; Nie, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Nian, X. Berberine as a multi-target therapeutic agent for obesity: from pharmacological mechanisms to clinical evidence. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagimoto, A.; Matsui, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Hibi, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Osaki, N. Effects of Ingesting Both Catechins and Chlorogenic Acids on Glucose, Incretin, and Insulin Sensitivity in Healthy Men: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moetlediwa, M.T.; Ramashia, R.; Pheiffer, C.; Titinchi, S.J.J.; Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E.; Jack, B.U. Therapeutic Effects of Curcumin Derivatives against Obesity and Associated Metabolic Complications: A Review of In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Mirzaei, A.; Najjar Khalilabad, S.; Askari, V.R.; Baradaran Rahimi, V. Promising influences of hesperidin and hesperetin against diabetes and its complications: a systematic review of molecular, cellular, and metabolic effects. EXCLI J. 22Doc1235 ISSN 1611-2156 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, Y.; Dik, B. The comparison of the antidiabetic effects of exenatide, empagliflozin, quercetin, and combination of the drugs in type 2 diabetic rats. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 38, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elekofehinti, O.O.; Molehin, O.R.; Akinjiyan, M.O.; Fakayode, A.E. Rutin modulates the TGR5/GLP1 pathway and downregulates proinflammatory cytokines genes in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Food Bioact. 2024, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavyani, Z.; Shahhosseini, E.; Moridpour, A.H.; Falahatzadeh, M.; Vajdi, M.; Musazadeh, V.; Askari, G. The effect of berberine supplementation on lipid profile and obesity indices: An umbrella review of meta-analysis. PharmaNutrition 2023, 26, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, V.R.; Khosravi, K.; Baradaran Rahimi, V.; Garzoli, S. A Mechanistic Review on How Berberine Use Combats Diabetes and Related Complications: Molecular, Cellular, and Metabolic Effects. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shou, J.-W.; Shaw, P.-C. Berberine Reduces Lipid Accumulation in Obesity via Mediating Transcriptional Function of PPARδ. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, A.-S.; Jeon, S.-M.; Kim, M.-J.; Yeo, J.; Seo, K.-I.; Choi, M.-S.; Lee, M.-K. Chlorogenic acid exhibits anti-obesity property and improves lipid metabolism in high-fat diet-induced-obese mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Ding, Y.; Li, L.; Ge, M.; Ban, G.; Yang, H.; Dai, J.; Zhang, L. Effects and Mechanism of Chlorogenic Acid on Weight Loss. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2020, 21, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimpley, V.; Patil, S.; Srinivasan, K.; Desai, N.; Murthy, P.S. The chemistry of chlorogenic acid from green coffee and its role in attenuation of obesity and diabetes. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 50, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Guo, K.; Zhou, F.; Yang, H. Use of Chlorogenic Acid against Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 9680508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marton, L.T.; Pescinini-e-Salzedas, L.M.; Camargo, M.E.C.; Barbalho, S.M.; Haber, J.F.D.S.; Sinatora, R.V.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; Girio, R.J.S.; Buchaim, D.V.; Cincotto Dos Santos Bueno, P. The Effects of Curcumin on Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 669448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivari, F.; Mingione, A.; Brasacchio, C.; Soldati, L. Curcumin and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Prevention and Treatment. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Khatibi Shahidi, F.; Khorsandi, K.; Hosseinzadeh, R.; Gul, A.; Balick, V. An update on molecular mechanisms of curcumin effect on diabetes. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyrinck, A.M.; Sánchez, C.R.; Rodriguez, J.; Cani, P.D.; Bindels, L.B.; Delzenne, N.M. Prebiotic Effect of Berberine and Curcumin Is Associated with the Improvement of Obesity in Mice. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Li, M.; Zhu, M.; Liu, X.; Huang, K.; Li, W.; Wang, S.-X.; Yin, Y.; Li, P. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate alleviates type 2 diabetes mellitus via β-cell function improvement and insulin resistance reduction. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadh, M.J.; Gataa, I.S.; Hussam, A.S.; Kaur, I.; Kumar, A.; Godara, P.; Zainul, R.; Muzammil, K.; Zahrani, Y. Effect of Epigallocatechin Gallate on Glycemic Index: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. Ther. 2025, 47, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soussi, A.; Gargouri, M.; Magné, C.; Ben-Nasr, H.; Kausar, M.A.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Saeed, M.; Snoussi, M.; Adnan, M.; El-Feki, A.; et al. (−)-Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) pharmacokinetics and molecular interactions towards amelioration of hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia associated hepatorenal oxidative injury in alloxan induced diabetic mice. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 368, 110230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Ouyang, J.; Li, M.; Rengasamy, K.R.R.; Liu, Z. Effects of green tea polyphenol extract and epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate on diabetes mellitus and diabetic complications: Recent advances. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 5719–5747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldızhan, K.; Bayir, M.H.; Huyut, Z.; Altındağ, F. Effect of Hesperidin on Lipid Profile, Inflammation and Apoptosis in Experimental Diabetes. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 2025, 521, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaviani, F.; Baratpour, I.; Ghasemi, S. The Antidiabetic Mechanisms of Hesperidin: Hesperidin Nanocarriers as Promising Therapeutic Options for Diabetes. Curr. Mol. Med. 2024, 24, 1483–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Jin, J.; Zou, G.; Sui, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhao, D.; Liu, L. Hesperidin prevents hyperglycemia in diabetic rats by activating the insulin receptor pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 21, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, P.; Choudhury, S.T.; Seidel, V.; Rahman, A.B.; Aziz, Md.A.; Richi, A.E.; Rahman, A.; Jafrin, U.H.; Hannan, J.M.A.; Abdel-Wahab, Y.H.A. Therapeutic Potential of Quercetin in the Management of Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus. Life 2022, 12, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanya, R. Quercetin for managing type 2 diabetes and its complications, an insight into multitarget therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michala, A.-S.; Pritsa, A. Quercetin: A Molecule of Great Biochemical and Clinical Value and Its Beneficial Effect on Diabetes and Cancer. Diseases 2022, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elekofehinti, O.O.; Molehin, O.R.; Akinjiyan, M.O.; Fakayode, A.E. Rutin modulates the TGR5/GLP1 pathway and downregulates proinflammatory cytokines genes in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Food Bioact. 2024, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maradesha, T.; Patil, S.M.; Phanindra, B.; Achar, R.R.; Silina, E.; Stupin, V.; Ramu, R. Multiprotein Inhibitory Effect of Dietary Polyphenol Rutin from Whole Green Jackfruit Flour Targeting Different Stages of Diabetes Mellitus: Defining a Bio-Computational Stratagem. Separations 2022, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieniuk, B.; Pawełkowicz, M. Berberine as a Bioactive Alkaloid: Multi-Omics Perspectives on Its Role in Obesity Management. Metabolites 2025, 15, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaba, S.; Saini, A.; Singh, G.; Monga, V. An insight into the medicinal attributes of berberine derivatives: A review. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 38, 116143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.; Taine, E.G.; Meng, D.; Cui, T.; Tan, W. Chlorogenic Acid: A Systematic Review on the Biological Functions, Mechanistic Actions, and Therapeutic Potentials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urošević, M.; Nikolić, L.; Gajić, I.; Nikolić, V.; Dinić, A.; Miljković, V. Curcumin: Biological Activities and Modern Pharmaceutical Forms. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, S.; Maqsood, M.; Mahtab, N.; Khan, M.I.; Sahar, A.; Zaib, S.; Gul, S. Epigallocatechin gallate: Phytochemistry, bioavailability, utilization challenges, and strategies. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa-Gómez, C.I.; Rocha-Guzmán, N.E.; Gallegos-Infante, J.A.; Moreno-Jiménez, M.R.; Vázquez-Cabral, B.D.; González-Laredo, R.F. Plants with potential use on obesity and its complications. EXCLI J. 14Doc809 ISSN 1611-2156 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrzynska, K. Hesperidin: A Review on Extraction Methods, Stability and Biological Activities. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, F.; Hadidi, M. Recent Advances in Potential Health Benefits of Quercetin. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muvhulawa, N.; Dludla, P.V.; Ziqubu, K.; Mthembu, S.X.H.; Mthiyane, F.; Nkambule, B.B.; Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E. Rutin ameliorates inflammation and improves metabolic function: A comprehensive analysis of scientific literature. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 178, 106163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, D.; Nagendra, L.; Anne, B.; Kumar, M.; Sharma, M.; Kamrul-Hasan, A.B.M. Orforglipron, a novel non-peptide oral daily glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist as an anti-obesity medicine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2024, 10, e743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratt, E.; Ma, X.; Liu, R.; Robins, D.; Haupt, A.; Coskun, T.; Sloop, K.W.; Benson, C. Orforglipron (LY3502970 ), a novel, oral non-peptide glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist: A Phase 1a, blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized, single- and multiple-ascending-dose study in healthy participants. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2023, 25, 2634–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Zoete, V. A BOILED-Egg To Predict Gastrointestinal Absorption and Brain Penetration of Small Molecules. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem PubChem Available online:. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Belousoff, M.J.; Danev, R.; Sexton, P.M.; Wootten, D. Semaglutide-bound Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Receptor in Complex with Gs protein: 7ki0 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.H.; Zhou, Q.T.; Cong, Z.T.; Hang, K.N.; Zou, X.Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Y.; Dai, A.T.; Liang, A.Y.; Ming, Q.Q.; et al. Cryo-EM structure of the tirzepatide-bound human GIPR-Gs complex: 7fiy 2022. [CrossRef]

- Scapin, G. Human DPP4 in complex with a ligand 34a. Available: https://www.rcsb.

- Zhang, H.; Wen, H.Y. Crystal structure of E. coli NfsB in complex with berberine: 7x32 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pratap, S. Crystal structure of chorismate mutase like domain of bifunctional DAHP synthase of Bacillus subtilis in complex with Chlorogenic acid. Available. [CrossRef]

- Elkins, J.M.; Soundararajan, M.; Vollmar, M.; Krojer, T.; Bountra, C.; Edwards, A.M.; Arrowsmith, C.; Knapp, S. Human DYRK2 bound to Curcumin: 6hdr 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kowalinski, E.; Zubieta, C.; Wolkerstorfer, A.; Szolar, O.H.; Ruigrok, R.W.; Cusack, S. Influenza strain pH1N1 2009 polymerase subunit PA endonuclease in complex with (-)-epigallocatechin gallate from green tea: 4awm 2012. [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Kobilka, B.K.; Sloop, K.W.; Feng, D.; Kobilka, T.S. cryo-EM of human GLP-1R bound to non-peptide agonist LY3502970: 6xox 2020. [CrossRef]

- Arriaza, R.H.; Dermauw, W.; Wybouw, N.; Van Leeuwen, T.; Chruszcz, M. Crystal structure of TuUGT202A2 (Tetur22g00270) in complex with quercetin: 8sfw 2024. [CrossRef]

- Grygier, P. Crystal structure of DYRK1A in complex with rutin. Available: https://www.rcsb.

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).