1. Introduction

Machine Translation (MT) – the automatic translation of text or speech from one language to another – has long been recognized as one of the most challenging tasks in artificial intelligence. Over the past decade, advances in neural network architectures and the availability of large parallel corpora have led to dramatic improvements in MT quality [

1]. Recently, the emergence of large language models (LLMs) has further revolutionized the field. General-purpose LLMs trained on massive multilingual data have demonstrated the ability to perform translation without explicit parallel training, raising the question of whether they can replace or augment dedicated MT systems [

2]. For example, GPT-5 (a state-of-the-art LLM), can produce highly fluent translations in many languages, suggesting that LLMs are now at a point where they could potentially serve as general MT engines. However, the extent of their advantages over traditional neural MT and their limitations across different languages remain active areas of research.

Early evaluations indicate a mixed picture. On one hand, LLMs like ChatGPT/GPT-5 have achieved translation quality on high-resource language pairs that is competitive with or even surpasses specialized MT models in certain cases. For instance, a recent study [

3] in the medical domain found GPT-4’s translations from English to Spanish and Chinese were over 95% accurate, on par with commercial MT (Google Translate) in those languages. However, GPT-4’s accuracy dropped to 89% for English–Russian, trailing Google Translate’s performance in that case. Another evaluation comparing ChatGPT to Google’s MT on patient instructions found ChatGPT excelled in Spanish (only 3.8% of sentences mistranslated vs 18.1% for Google) but underperformed in Vietnamese, with ChatGPT mistranslating 24% of sentences compared to 10.6% for Google [

4]. These discrepancies highlight that LLM translation quality varies widely by language, content, and context. In literary translation, for example, one study observed that human translators still significantly outperformed ChatGPT in accuracy (94.5% vs 77.9% on average), even though ChatGPT’s output was often fluent and grammatically correct [

5]. Such findings reinforce that being fluent is not the same as being faithful: LLMs may produce very natural-sounding text but can subtly distort meaning, especially in nuanced or domain-specific content.

A key challenge, therefore, is how to evaluate translation quality in this new era. Traditional automatic metrics like BLEU, ROUGE, or TER – based on

n-gram overlap with reference translations – are fast and reproducible, but they have well-documented limitations [

6,

7]. They often correlate poorly with human judgments, failing to capture semantic adequacy or subtle errors. As a result, researchers have argued for more comprehensive evaluation frameworks. The Multidimensional Quality Metrics (MQM) paradigm, for instance, evaluates translations along multiple error categories (accuracy, fluency, terminology, style, etc.) instead of a single score [

8,

9]. It provides a more granular assessment compared to single-score metrics. Such multi-aspect human evaluation provides deeper insight, revealing cases where a translation might score high on adequacy but still contain grammatical errors or unnatural phrasing. Recent studies have shown that MQM can effectively capture the nuances of translation quality, especially when used with human annotations [

9,

10]. In recent MT competitions, the WMT24 Metrics Shared Task utilized MQM to benchmark LLM-based translations, confirming the robustness of fine-tuned neural metrics [

10]. The MT competitions have increasingly relied on MQM-style human assessments, confirming that even human evaluators often disagree when forced to give a single overall score. This suggests that breaking down quality into linguistic dimensions yields more reliable and informative assessments.

Interestingly, LLMs themselves are now being explored as evaluation tools. If an LLM can understand and generate language, perhaps it can also judge translation quality by comparing a translation against the source for fidelity and fluency. Early studies are promising: some have found that certain LLMs’ judgments correlate surprisingly well with human evaluation. For example, Kocmi and Federmann showed in [

11] that ChatGPT (GPT-3.5) can rank translations with correlations comparable to traditional human rankings. Research on LLM-based evaluators (sometimes called GPT evaluators or G-Eval) has demonstrated that prompting GPT-5 with detailed instructions and even chain-of-thought reasoning can yield evaluation scores approaching human agreement [

12]. Beyond translation, similar concerns about annotation reliability have been raised in low-resource NLP tasks. A recent comparative study assessed annotation quality across Turkish, Indonesian, and Minangkabau NLP tasks, showing that while LLM-generated annotations can be competitive—particularly for sentiment analysis—human annotations consistently outperform them on more complex tasks, underscoring LLM limitations in handling context and ambiguity [

13]. Building on this, Nasution et al. [

14] benchmarked 22 open-source LLMs against ChatGPT-4 and human annotators on Indonesian tweet sentiment and emotion classification, finding that state-of-the-art open models can approach closed-source LLMs but with notable gaps on challenging categories (e.g., Neutral sentiment, Fear emotion). These studies highlight broader themes of evaluator calibration, annotation reliability, and model consistency in low-resource settings—issues that directly parallel the challenges of using LLMs for MT evaluation.

In summary, the landscape of MT in 2025 is being reshaped by large language models, bringing both opportunities and open questions. This paper aims to contribute along two fronts: (1) assessing how a specialized smaller-scale LLM for a particular language pair (English–Indonesian) compares to larger general models on translation quality, and (2) examining the efficacy of a multi-dimensional evaluation approach that combines human judgments and GPT-5. We focus on three core dimensions of translation quality – morphosyntactic accuracy (grammar/syntax and word form correctness), semantic accuracy (fidelity to source meaning), and pragmatic effectiveness (appropriate style, tone, and coherence in context). Using these fine-grained criteria, we evaluate translations produced by three different LLMs. Human evaluators and GPT-5 are both used to rate the translations, allowing us to analyze where an LLM evaluator agrees with or diverges from human opinion. By concentrating on a relatively under-studied language pair (English–Bahasa Indonesia) and a detailed evaluation scheme, our study provides new insights into LLM translation capabilities and the feasibility of AI-assisted evaluation. The goal is to inform both the development of more effective translation models and the design of evaluation frameworks that can reliably benchmark translation quality in the era of LLMs.

In this work, we present a comprehensive evaluation of three LLM-based translation systems of different scales on an English–Indonesian translation task. We introduce a multi-aspect evaluation framework with human raters and GPT-5, and we analyze the correlation and differences between GPT-based and human-based assessments. The experimental results demonstrate that a moderately-sized, translation-focused LLM can outperform a larger general-purpose model on this task, and that GPT-5’s evaluation aligns with human judgment to a high degree (overall correlation ≈0.82) while systematically giving higher scores. We discuss the implications of these findings for developing cost-effective translation solutions and hybrid human–AI evaluation methods. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to report detailed human vs GPT-5 evaluation on a real translation task, especially for Indonesian, and we hope it provides a useful case study for deploying LLMs in MT. We next situate our study within recent work on LLM-based MT and multi-aspect evaluation.

To summarize, this paper contributes to MT evaluation and translation pedagogy in four main ways. First, it proposes a multidimensional evaluation framework incorporating Morphosyntactic, Semantic, and Pragmatic aspects. Second, it empirically demonstrates that GPT-5 can approximate human judgments across these dimensions with high reliability. Third, it provides a novel classroom validation study showing that rubric calibration significantly enhances students’ scoring consistency. Finally, it bridges automated evaluation and translation education, offering a unified framework for both model assessment and evaluator training.

3. Method

3.1. MQM Mapping and Evaluation Rubric

To ensure that the three proposed linguistic metrics are not ad hoc but grounded in a recognized translation quality framework, we mapped them to the Multidimensional Quality Metrics (MQM) standard. MQM provides a taxonomy of translation errors categorized by accuracy, fluency, style, locale conventions, and related subcategories. By aligning our rubric-based metrics with MQM, we ensure methodological validity and comparability with prior MT evaluation studies.

Morphosyntactic corresponds to MQM categories under Linguistic Conventions and Accuracy, specifically targeting Grammar, Agreement, and Word Form issues, as well as errors in textual conventions, transliteration, or hallucinated forms. This dimension captures whether the translation is grammatically well-formed and morphologically consistent.

Semantic aligns with MQM categories such as Accuracy, Design and Markup, and Audience Appropriateness, covering subcategories including Mistranslation, Omission, and Addition. It evaluates the fidelity of the conveyed meaning, ensuring that no critical content is missing or distorted.

Pragmatic relates to MQM categories Design and Markup, Locale Conventions, and Terminology, with subcategories including Style, Formality, and Audience Appropriateness. It addresses appropriateness of tone, register, and cultural or contextual fit, extending beyond purely linguistic correctness.

Table 1 and

Table 2 present a structured mapping of our three linguistic metrics to the corresponding MQM categories and subcategories, together with their optimized descriptions. This mapping provides transparency on how the proposed rubric-based evaluation integrates into the broader MQM framework and clarifies the interpretability of the scores.

Human annotators followed a detailed 5-point rubric for each dimension (Morphosyntactic, Semantic, Pragmatic). The condensed 5-point evaluation rubric for translation quality is listed in

Table 3. The rubric defines scoring guidelines for every level from 1 (very poor) to 5 (excellent), covering grammar and morphology, semantic fidelity, and pragmatic appropriateness. The full rubric is provided in

Appendix A.

3.2. Models and Translation Task

We evaluate three different LLM-based models on an English–Indonesian translation task. These models represent a spectrum of sizes and training strategies:

Qwen 3 (0.6B): A relatively small-scale LLM with about 0.6 billion parameters. Qwen 3 is a general-purpose language model (comparable in size to GPT-2-medium) that has some multilingual capability but no specialized training for MT. We include it to represent a lightweight baseline model and to examine how a smaller LLM handles translation into Indonesian.

LLaMA 3.2 (3B): A larger 3-billion-parameter model based on Meta’s LLaMA architecture (likely LLaMA-2 or an internal variant). This model is multilingual and significantly bigger than Qwen, though still much smaller than GPT-5. It has not been explicitly fine-tuned for translation, but given its size and training on a large corpus including multiple languages, it is expected to perform zero-shot translation reasonably well. We denote it as LLaMA 3.2 (3B) for simplicity. This model stands in for a state-of-the-art general LLM (smaller than GPT-5) that might be used for translation tasks.

Gemma 3 (1B): A 1-billion-parameter model distributed through the Ollama library. We used Gemma exactly as provided, without any fine-tuning or customization. Although not explicitly trained for English–Indonesian translation, it is capable of producing translations when prompted appropriately, making it a useful comparison point against Qwen and LLaMA.

The translation direction is English to Bahasa Indonesia, chosen because Indonesian is a widely spoken language that nonetheless qualifies as a moderately resourced language (it has a substantial web presence and some translation corpora, but far less than languages like French or Chinese). This allows us to explore how LLMs handle a language that is neither extremely high-resource nor truly low-resource. Indonesian also presents interesting linguistic challenges; It has relatively simple morphology (no gender or plural inflections, but extensive affixation), flexible word order, and contextual pronoun drop, which means translations require care in preserving meaning that might be implicit in English pronouns or tense markers.

Each model was used to translate a test set of 100 English sentences. The English source sentences were sampled to cover a range of content: factual statements, colloquial expressions, and a few idiomatic or culturally specific phrases. The sentence length ranged from short (5–6 words) to moderately long (around 20–25 words). Examples of source sentences include general knowledge statements (“Archimedes was an ancient Greek thinker, and ...”), conversational remarks (“So the project is going very, very well, and ...”), and abstract/philosophical sentences (“There are things that are intrinsically wrong ...”). This variety ensures we test not only straightforward translations but also more nuanced ones that might stress semantic understanding and pragmatic rendering.

All models were run in a consistent inference setting: greedy or high-probability sampling decoding (to minimize randomness in outputs) with any available translation or instruction prompts configured similarly. The three models (Qwen 3 (0.6B), LLaMA 3.2 (3B), and Gemma 3 (1B)) were used exactly as provided in the Ollama library, without any additional fine-tuning or customization. For each model, we employed a simple prompt format such as: “Translate the following English sentence to Indonesian: [sentence]”. The output from each model—the Indonesian translation hypothesis—was then recorded for evaluation.

The reference translations were only used to compute BLEU scores in the preliminary experiment. For both the LLM-based and human evaluations, the reference translations were hidden to avoid bias from reference phrasing. Instead, evaluators relied solely on the source and the system output, ensuring that adequacy, fluency, and the three linguistic metrics were judged directly rather than by overlap with a gold standard.

3.3. Human Evaluation Procedure

We recruited three bilingual evaluators to assess the translation outputs. All three evaluators are native or fluent speakers of Indonesian with advanced proficiency in English. Two have backgrounds in linguistics and translation studies, and the third is a professional translator. This mix was intended to balance formal knowledge of language with practical translation experience. Before the evaluation, we conducted a brief training session to familiarize the evaluators with the rating criteria and ensure consistency. We provided examples of translations and discussed how to interpret the rating scales for each aspect.

Each evaluator was given the source English sentence and the model’s Indonesian translation, and asked to rate it on three aspects:

Morphosyntactic Quality: Is the translation well-formed in terms of grammar, word order, and word forms? With this aspect, raters do not yet focus on whether a translation is meaningfully accurate, but focus entirely on the accuracy of the morphology and syntax. They check for issues such as incorrect affixes, plurality, tense markers (where applicable in Indonesian), word order mistakes, agreement errors, or any violation of Indonesian grammatical norms. A score of 5 means the sentence is grammatically perfect and natural; a 3 indicates some awkwardness or minor errors; a 1 indicates severely broken grammar that impedes understanding.

Semantic Accuracy: Does the translation faithfully convey the meaning of the source? This is essentially adequacy: how much of the content and intent of the original is preserved. Raters compare the Indonesian translation against the source English to identify any omissions, additions, or meaning shifts. A score of 5 means the translation is completely accurate with no loss or distortion of meaning; a 3 means some nuances or minor details are lost/mistranslated but the main message is there; a 1 means it is mostly incorrect or missing significant content from the source.

Pragmatic Appropriateness: Is the translation appropriate and coherent in context and style? This covers aspects like tone, register, and overall coherence. Raters judge if the translation would make sense and be appropriate for an Indonesian reader in the intended context of the sentence. For example, does it use the correct level of formality? Does it avoid unnatural or literal phrasing that, while grammatically correct, would sound odd to a native speaker? This category also captures whether the translation is pragmatically effective – e.g., if the source had an idiom, was it translated to an equivalent idiom or explained in a way that an Indonesian reader would understand the intended effect? A score of 5 means the translation not only is correct but also feels native – one could not easily tell it was translated. A 3 might indicate it’s understandable but has some unnatural phrasing or slight tone issues. A 1 would mean that it is pragmatically inappropriate or incoherent (perhaps overly literal or culturally off-base).

Each aspect was rated on an integral 1–5 scale (where 5 = excellent, 1 = very poor). We explicitly instructed that scores should be considered independent – e.g., a grammatically perfect but meaning-wrong translation could get Morphosyntactic=5, Semantic=1. By collecting these separate scores, we obtain a profile of each translation’s strengths and weaknesses.

To ensure consistency, the evaluators first did a pilot round of 10 sample translations (covering all three models in random order) and discussed any discrepancies in the scoring. After refining the shared understanding of the criteria, they proceeded to rate the full set. Each model’s 100 translations were mixed and anonymized, so evaluators did not know which model produced a given translation (to prevent any bias). In total, we collected 3 (evaluators) (sentences) (aspects) human ratings per model, or 2700 ratings overall.

For analysis, we often consider the average human score on each aspect for a given translation. We compute per-sentence averages across the three evaluators for Morphosyntactic, Semantic, and Pragmatic dimensions. This gives a more stable score per item and smooths out individual rater variance. We also compute an overall human score per sentence by averaging all three aspect scores (this overall is not used for primacy in evaluation, but for correlation analysis and summary).

3.4. GPT-5 Evaluation Procedure

In parallel to human evaluation, we employed OpenAI’s GPT-5 (gpt-5-chat) model to evaluate the translations on the same aspects. We used the June 2025 version of GPT-5 accessible via an API (Azure AI Foundry), with the default large language model behavior (which has a high level of linguistic competence). The motivation was to see if GPT-5 can approximate human judgments and to identify where it might differ.

For each English source sentence and its machine translation, we crafted a prompt for GPT-5 instructing it to act as a translation quality evaluator. The prompt was:

“You are a bilingual expert in English and Indonesian. You will be given an English sentence and an Indonesian translation of it. Evaluate the translation on a scale of 1 to 5 for three criteria: (A) Morphosyntactic correctness (grammar/wording), (B) Semantic accuracy (meaning fidelity), (C) Pragmatic naturalness/appropriateness. Provide the three scores as numbers.”

We avoided revealing which model produced the translation, and we randomized the order of sentences, so GPT-5 evaluated each translation independently. GPT-5 then returned three scores. We verified qualitatively on a few cases that GPT-5’s scoring was reasonable (for example, it gave lower scores to sentences where obvious meaning errors were present). Thereafter, we automated this process for all 100 sentences for each model. We denote the scores GPT-5 gave as Morphosyntactic-GPT, Semantic-GPT, Pragmatic-GPT for each translation.

Notably, GPT-5 was not given any “reference” or hint beyond the source and translation. This is effectively a zero-shot evaluation. We did not use chain-of-thought or explanations to avoid incurring high cost and to streamline the output (though we acknowledge that including reasoning might further improve reliability). Still, GPT-5’s strong language understanding suggests it can make decent judgments even with this straightforward prompting.

Using GPT-5 as an evaluator allows us to compare its ratings directly with the average human ratings for each translation and aspect. We treat GPT-5 as an additional “evaluator 4,” and we can compute metrics like Pearson correlation between GPT-5’s scores and the human average scores on each aspect. High correlation would indicate GPT-5 agrees with humans on which translations are good or bad; consistent differences in magnitude would indicate bias. We can also identify specific instances where GPT-5 disagrees with all humans, to qualitatively analyze potential reasons (though due to brevity we focus mostly on aggregate results in this paper).

All prompts and model outputs were logged for transparency. The combination of human and GPT-5 evaluations provides a rich evaluation dataset for analysis.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

Our evaluation involved human judgments, so we adhered to proper ethical guidelines. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at our institution. All evaluator participants gave informed consent and were compensated for their time. They were informed that the translations they evaluate were machine-generated and that their ratings would be used for research purposes to improve MT systems. No personally identifiable or sensitive content was included in the test sentences. We also maintained confidentiality of the evaluators’ identities and individual scores, only analyzing aggregated results. By ensuring voluntary participation and transparency in use of the data, we aimed to follow the highest ethical standards in our human-subject research.

3.6. Classroom Evaluation Study

To complement the quantitative analysis, a classroom experiment was conducted to evaluate whether rubric-based calibration activities improve students’ evaluation consistency. A total of 26 undergraduate translation students participated in this study. Students acted as evaluators using the same 5-point rubric (Morphosyntactic, Semantic, Pragmatic) applied in the main evaluation. The experiment consisted of three phases using Google Forms:

Pre-test: Students rated 15 translations (5 English–Indonesian sentences × 3 models: Qwen 3 (0.6B), LLaMA 3.2 (3B), and Gemma 3 (1B)).

Post-test: After a short discussion clarifying how to apply the rubric and what constitutes scores 1–5, students re-evaluated the same items.

Final test: Students rated 5 new items (indices 25, 47, 52, 74, and 97), each translated by the three models.

All ratings were compared against majority scores determined by three human experts and GPT-5. Two evaluation metrics were computed for each phase: Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Exact Match Rate. MAE captures the average deviation from the majority score, while Exact Match Rate represents the proportion of identical scores.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Evaluation Scores

After collecting all ratings, we first examine the average scores obtained by each model on each aspect, as evaluated by humans and by GPT-5.

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 summarizes these results, including mean scores and standard deviations, for the three models. Each score is on a 1–5 scale (higher is better). The human scores are averaged across the three human evaluators per item, then across all items for the model; the GPT scores are averaged across the 100 items for the model.

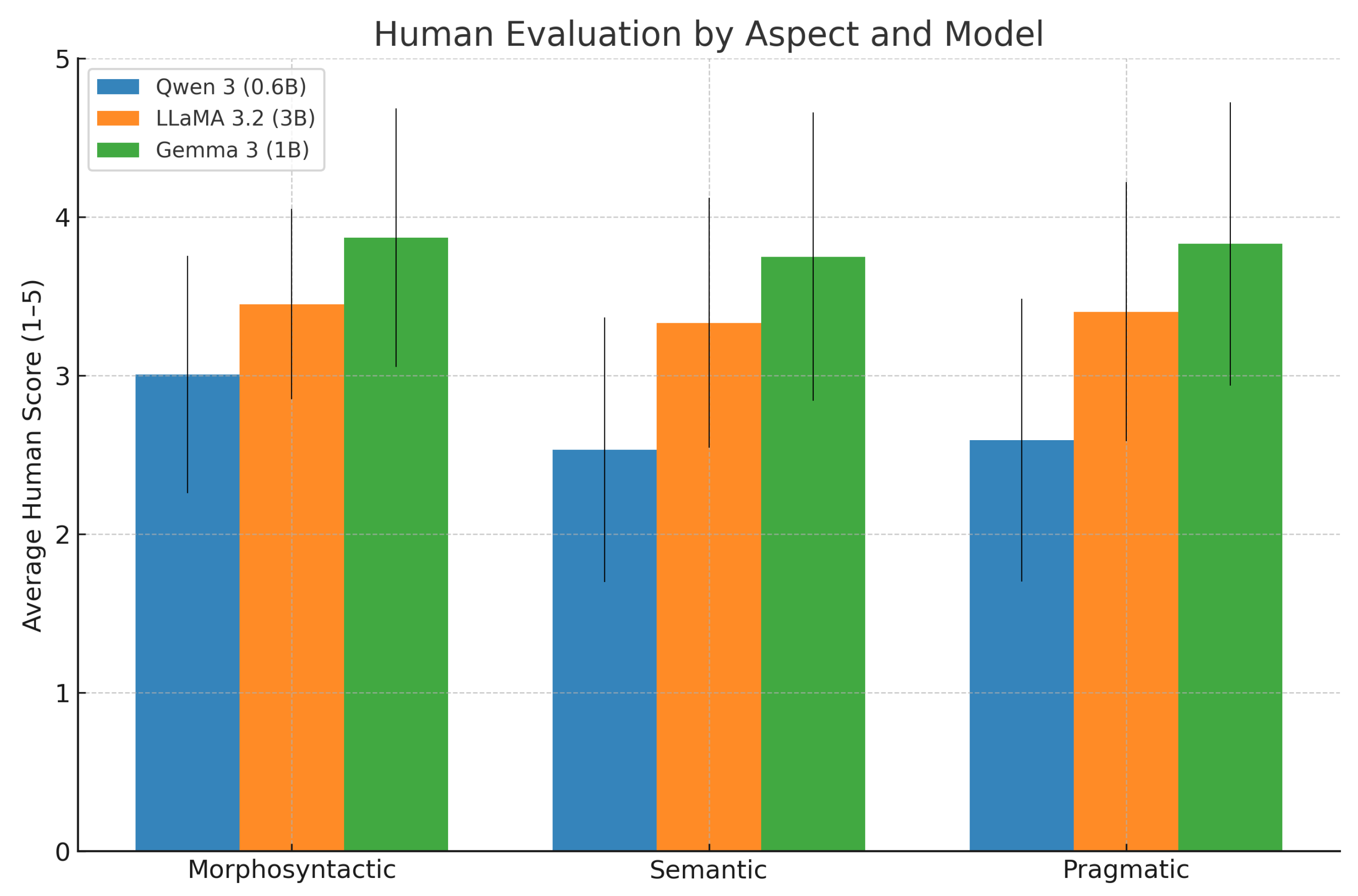

Gemma 3 achieves the highest human-rated scores on all three aspects. For example, Gemma’s average Semantic score is 3.75, compared to 3.33 for LLaMA and 2.53 for Qwen. This indicates Gemma’s translations most accurately preserve meaning. Similarly, for Morphosyntactic quality, Gemma averages 3.87 (approaching “very good” on our scale), higher than LLaMA’s 3.45 and Qwen’s 3.01. Pragmatic quality shows a similar ranking (Gemma 3.83 > LLaMA 3.40 > Qwen 2.59). In terms of overall quality (the average of all aspects), human evaluators rated Gemma around 3.82/5, LLaMA about 3.40/5, and Qwen only 2.71/5. In practical terms, Gemma’s translations were often deemed good on most criteria, LLaMA’s were fair to good with some issues, and Qwen’s were between poor to fair, frequently requiring improvement.

The differences between models are statistically significant. We performed paired t-tests on the human scores (pairing by source sentence since each sentence was translated by all models). For each aspect, Gemma’s scores were significantly higher than LLaMA’s ( in all cases), and LLaMA’s were in turn significantly higher than Qwen’s (). This confirms a clear ordering: Gemma > LLaMA > Qwen in translation quality. Notably, Gemma, despite having fewer parameters than LLaMA (1B vs 3B), outperforms it – suggesting that model design and training data composition, even without task-specific fine-tuning, can significantly influence translation quality.

All models scored lower on Semantic accuracy than on the other aspects (in human eval). For each model, the Semantic scores in

Table 5 (3.75, 3.33, 2.53 respectively) is the lowest among the three aspects. This suggests that meaning preservation is the most challenging aspect for the systems. Many translations that were fluent and grammatical still lost some nuance or made minor errors in meaning. For example, Qwen often dropped subtle content or mistranslated a word, earning it a lower semantic score even if the sentence was well-formed. LLaMA and Gemma did better but still occasionally missed culturally specific meanings or implied context. By contrast, Morphosyntactic scores are the highest for two of the models (LLaMA and Gemma). This indicates that from a purely grammatical standpoint, the translations were quite solid, especially for Gemma which likely reflects its model design and pretraining/data composition. Qwen’s morphosyntax score (3.01) was a bit higher than its pragmatic and much higher than its semantic, reflecting that even when it produces grammatically correct Indonesian, it often fails to convey the full meaning. Pragmatic scores were in between: e.g., LLaMA’s pragmatic 3.40 vs morph 3.45 (almost equal), Gemma’s pragmatic 3.83 vs morph 3.87 (almost equal). This means that aside from pure accuracy, the naturalness and appropriateness of translations track closely with overall fluency for these models. Gemma and LLaMA produce fairly natural-sounding translations, with only occasional hints of unnatural phrasing or wrong tone. Qwen, on the other hand, had a pragmatic score (2.59) closer to its semantic (2.53), meaning the poorer translations were both inaccurate and awkwardly worded.

These tendencies align with known behaviors of MT systems and LLMs. The fact that accuracy (semantic) lags behind fluency is a common observation: modern neural models often produce fluent output (thanks to strong language modeling) that can mask internal errors in meaning [

22]. Our evaluators caught those, hence the lower semantic scores. This underscores the value of evaluating aspects separately – if we had only a single score, we might not realize that meaning fidelity is a pain point. It also corroborates what Ataman

et al. noted about LLM translations: they tend to be more paraphrastic and sometimes compromise on strict fidelity [

1].

Next, we examine how the GPT-5 (AI) evaluation compares. The GPT columns in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 show that GPT-5’s scores were consistently higher than the human scores for all models and aspects. For instance, GPT-5 rated Gemma’s Morphosyntactic quality as 4.25 on average, whereas humans gave 3.87. GPT-5 even gave Qwen’s translations a ∼3.09 in morphosyntax (above “acceptable”), whereas humans averaged 3.01 (just borderline acceptable). This suggests GPT-5 was slightly more lenient on grammar. The difference is more pronounced in Pragmatic aspect: GPT-5 gave Gemma 4.35 vs humans’ 3.83, and LLaMA 4.09 vs humans’ 3.40. It appears GPT-5 found the translations more pragmatically acceptable than the human evaluators did. One possible reason is that GPT-5 might not pick up on subtle style or tone issues as strictly as a human native speaker would – it might focus on whether the content makes sense and is coherent, which it usually does, and thus give a high score. Human evaluators, however, might notice if a phrase, while coherent, is not the way a native would phrase it in that context (slight awkwardness). This points to a potential bias of GPT-5 to overestimate naturalness. Another contributing factor could be that GPT-5, lacking cultural intuition, assumes something is fine if grammatically fine, whereas humans use real-world expectations.

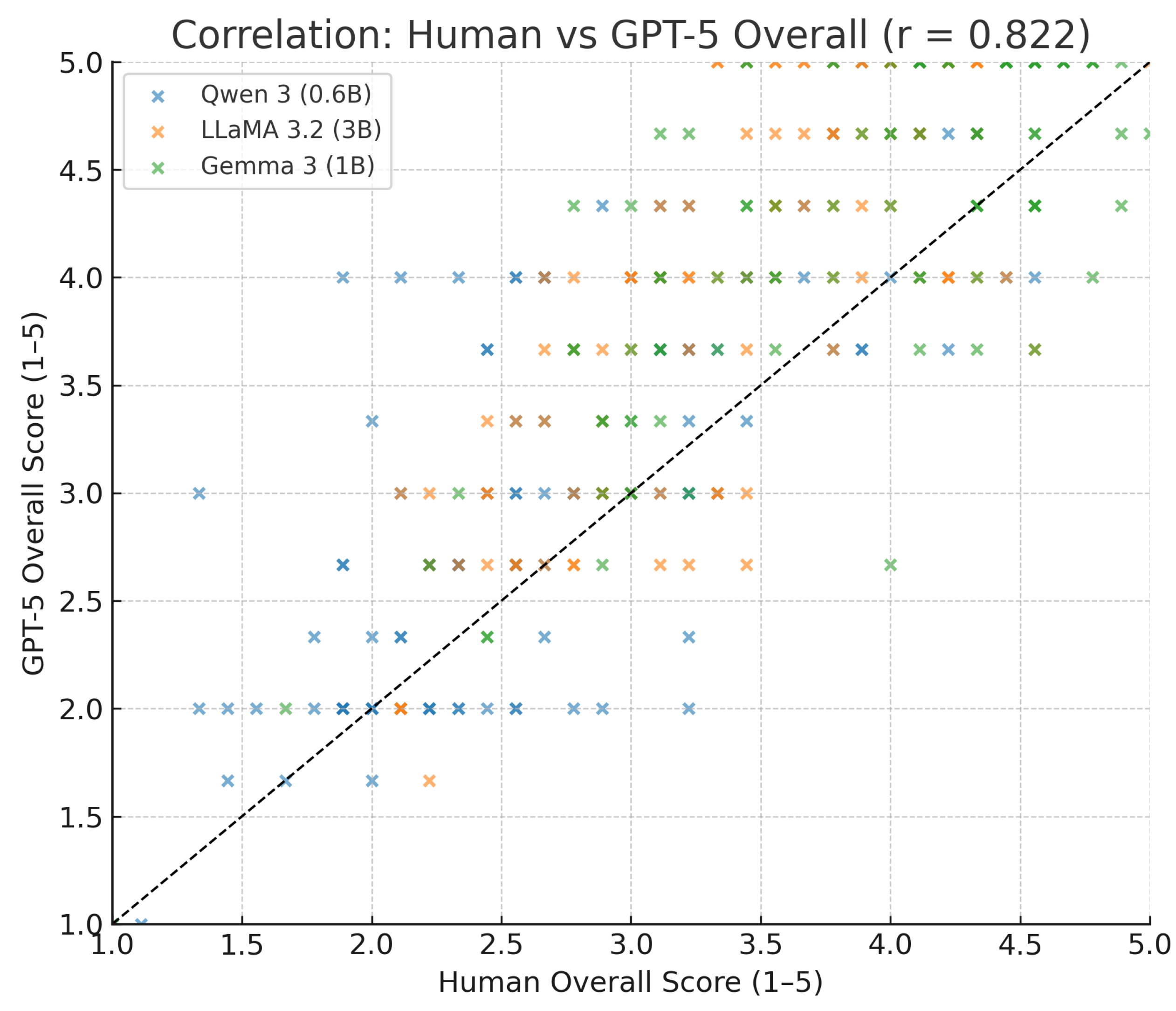

That said, it’s remarkable that GPT-5’s scores follow the same ranking of models: Gemma > LLaMA > Qwen. For example, GPT-5’s overall scores are ∼4.20 for Gemma, 3.92 for LLaMA, 3.04 for Qwen, maintaining the relative differences. Even on a per-aspect basis, GPT-5 consistently scored Gemma highest and Qwen lowest. We can visualize these comparisons in the figures below.

From

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, we clearly see the upward shift in GPT-5’s scoring. For instance, on Pragmatic quality (rightmost group of bars), GPT-5 scored even Qwen’s translations around 3.2 on average, whereas human evaluators scored them around 2.6. For LLaMA and Gemma, GPT-5 gave many translations a full 5 for pragmatics (finding them perfectly acceptable in tone), whereas human raters often gave 4, explaining the ∼0.5–0.7 gap in means. Despite this discrepancy in absolute terms, the correlation in trend is strong.

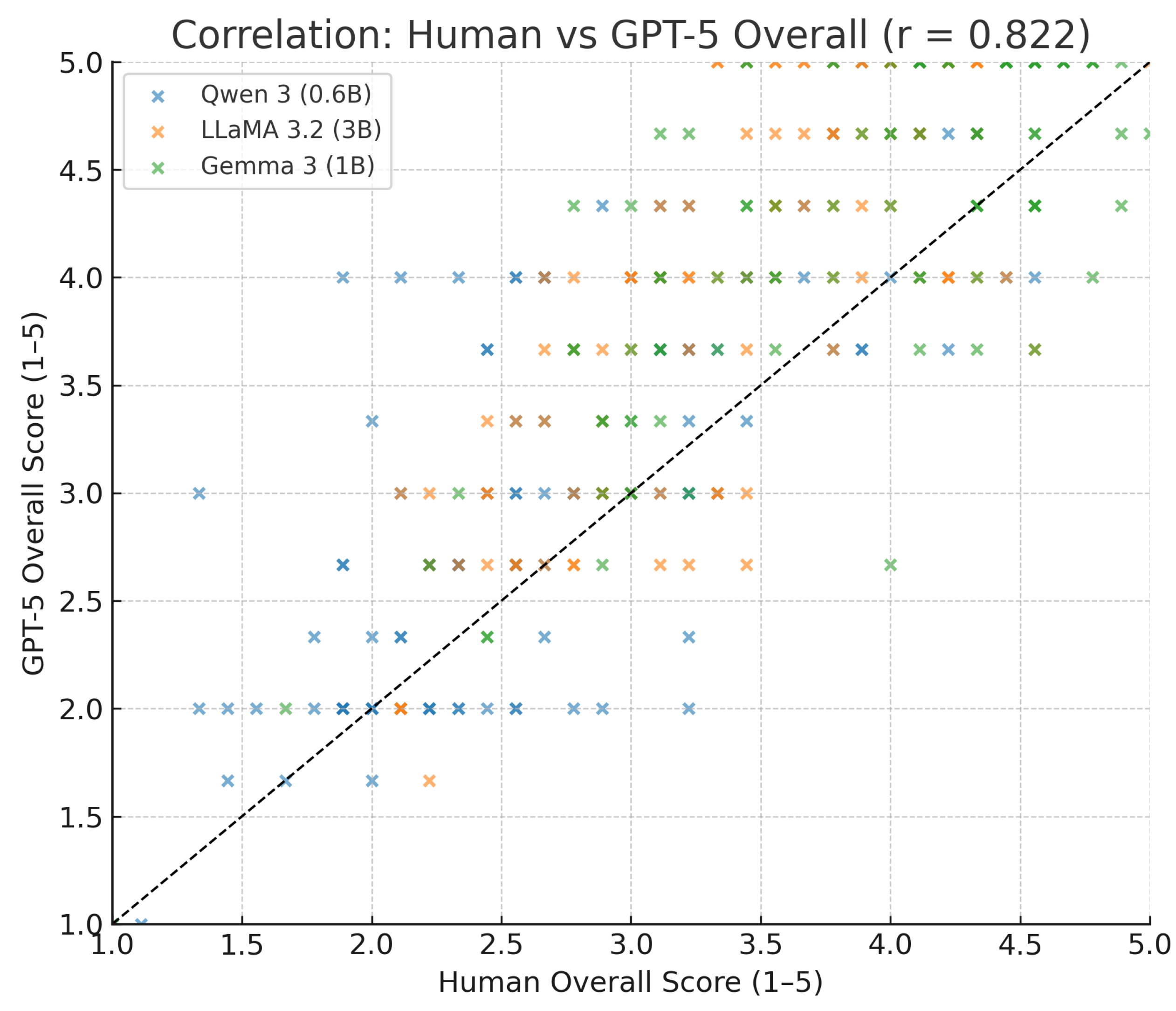

We calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient between GPT-5’s scores and the average human scores, across the set of 300 translation instances (100 sentences × 3 models). This was done separately for each aspect. The results are:

All correlation coefficients are high and statistically significant (

). Semantic accuracy had the highest agreement (

), which is encouraging – it means GPT-5 often concurred with human evaluators on which translations got the meaning right versus which did not. Morphosyntactic had a slightly lower correlation (∼0.72), possibly because GPT-5 might sometimes miss minor grammatical errors that humans catch (or vice versa, GPT might penalize something humans didn’t mind). Pragmatic is in between (∼0.78). We also computed an overall correlation (pairing each translation’s average of the three human scores with the average of GPT-5’s three scores). This yielded

, as shown in

Figure 3.

The consistency in model ranking and the high correlations suggest that GPT-5 largely agrees with human evaluators on relative quality – it discerns that Gemma’s outputs are better than Qwen’s, etc. This is notable: GPT-5 was not told anything about which model produced which output; it discerned quality purely from the translation content. The AI evaluator can thus differentiate good translations from bad ones in a similar way to humans. This finding is in line with recent research indicating LLMs can serve as effective judges of NLG quality.

However, the systematic score difference (GPT-5 being more generous) points to a calibration issue. GPT-5 might benefit from being “trained” or adjusted to match human severity if it were to be used as an automatic metric. In our results, GPT-5’s mean scores were higher by about 0.3–0.6 points. One could imagine applying a linear rescaling or subtracting a bias to better align it to the human scale. Alternatively, one could focus on rankings rather than absolute scores, since GPT-5 clearly ranks systems correctly and presumably would rank translations in a pairwise comparison correctly most of the time.

To delve deeper, we also analyzed the distribution of scores. Gemma’s translations received a human score of 4 or 5 (good to excellent) in 67% of instances for Morphosyntactic, 60% for Semantic, and 62% for Pragmatic. Qwen, by contrast, got 4 or 5 in only 30% of instances for Morphosyntactic, and under 20% for Semantic and Pragmatic – meaning the majority of Qwen’s outputs were mediocre or poor in meaning and style. LLaMA was intermediate, with roughly 50% of its outputs rated good. GPT-5’s scoring, on the other hand, rated a larger fraction as good. For example, GPT-5 gave Gemma a full 5 in pragmatics for 55% of sentences, whereas humans gave a 5 for only 40%. It’s worth noting that even humans rarely gave a perfect 5; they were using the full range. GPT-5 seemed to cluster scores at 3–5 and seldom used 1 or 2 except for clear failures. Humans likewise didn’t use 1 often (since outright incoherent translations were few), but they did use 2’s for some Qwen outputs where meaning was severely compromised.

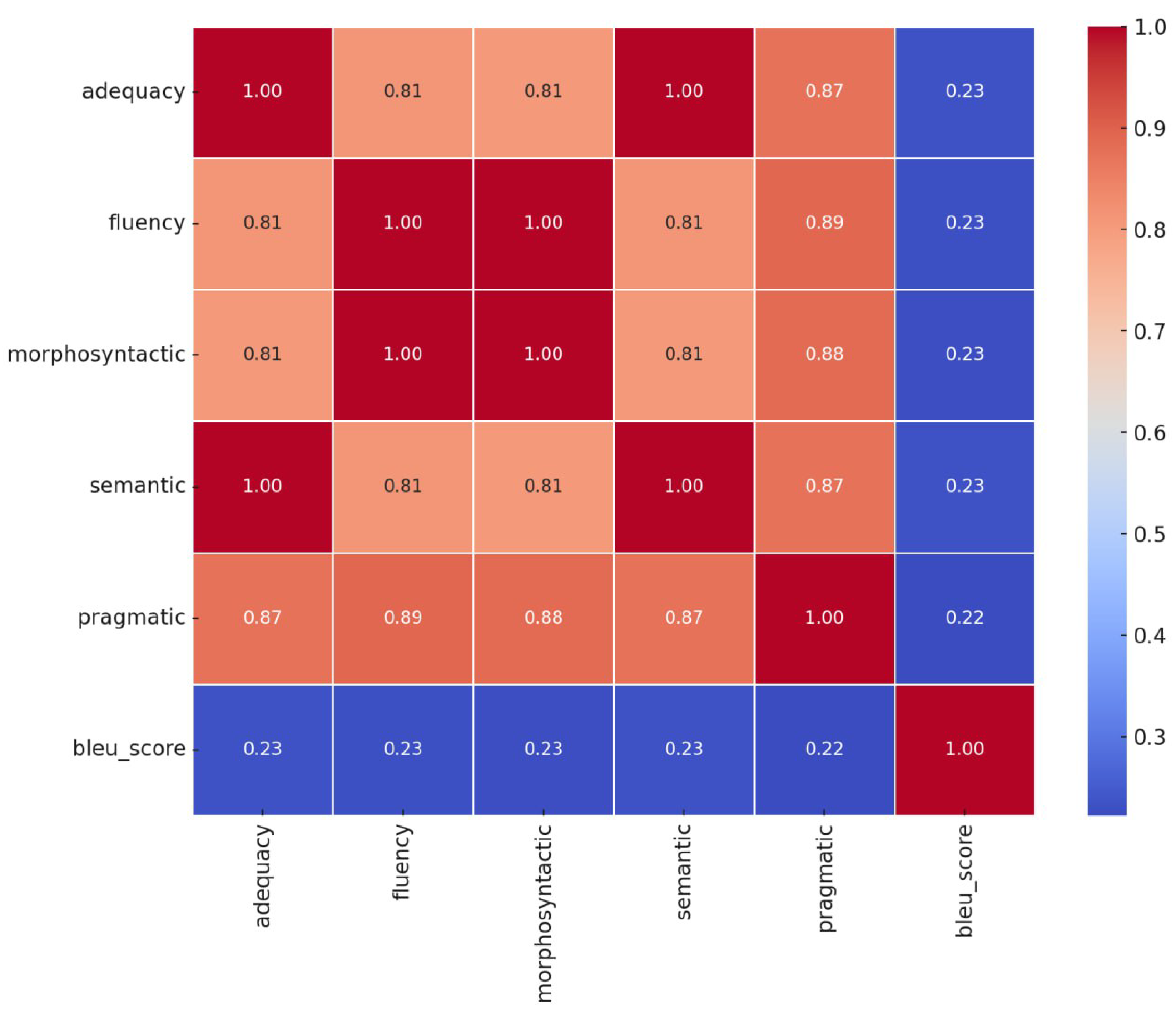

4.2. Cross-Metric Correlation in the Final 100-Item Study

Figure 4 visualizes the Pearson correlations among all evaluation metrics in the final experiment (Adequacy, Fluency, Morphosyntactic, Semantic, Pragmatic, and BLEU). Two strong convergence patterns emerge. First,

Adequacy and Semantic are nearly indistinguishable at the item level (r ≈ 1.00), indicating that the rubric used for Adequacy closely operationalizes the same construct as our Semantic dimension—faithfulness to source content. Second,

Fluency and Morphosyntactic are also essentially collinear (r ≈ 1.00), suggesting that the sentence-level grammatical well-formedness we captured under Morphosyntactic is the primary driver of perceived Fluency on our dataset. Cross-dimension correlations remain high (e.g., Adequacy↔Fluency ≈ 0.81; Morphosyntactic↔Pragmatic ≈ 0.88; Adequacy↔Pragmatic ≈ 0.87), consistent with the trends in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 and the ranking agreement observed in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

From a measurement perspective, the matrix suggests a

two-factor structure: (i) a

meaning factor where Adequacy and Semantic load near-1.0, and (ii) a

form/fluency factor where Fluency and Morphosyntactic load near-1.0.

Pragmatic correlates strongly with both factors (0.87–0.89), acting as a bridge between “being correct” and “sounding right.” This aligns with our qualitative analysis: items can be grammatically flawless yet miss nuance (Semantic shortfalls), or semantically faithful yet stylistically off (Pragmatic shortfalls). The high but not perfect cross-links (e.g., ∼0.81 between Adequacy and Fluency) reinforce the value of reporting aspects separately rather than collapsing to a single overall score.Moreover, the

low correlations between

BLEU and all rubric-based metrics (about 0.22–0.23 across the board) underscore that reference-overlap captures a different signal than the human/GPT-5 rubric scores. In our setting—where human and LLM evaluators judge fidelity and naturalness

without seeing the references—BLEU provides limited explanatory power for item-level quality variation. This observation complements the earlier results (Tables –

Table 7) and echoes known limitations of reference-based metrics for paraphrastic yet faithful translations. Taken together, the heatmap supports our design choice to foreground

semantic and

pragmatic judgments in addition to fluency/morphology and to treat BLEU as an auxiliary, not primary, signal in the final 100-item study.

For analysis and modeling, the near-collinearity suggests two practical simplifications: (1) report either Adequacy or Semantic (preferably retain Semantic as the construct-aligned label) to avoid redundancy; and (2) report either Fluency or Morphosyntactic (we keep Morphosyntactic to remain MQM-consistent). Pragmatic should remain separate, as it contributes distinct variance that is most sensitive to tone/idiom/style and where GPT-5 exhibited the largest leniency. Finally, if a single composite is needed, a two-factor aggregation (Meaning + Form, with Pragmatic partially loading on both) would be statistically justifiable and easier to calibrate across human and GPT-5 scales.

4.3. Preliminary GPT-Only Screening

Table 7 summarizes the 1,000-sample preliminary experiment scored solely by GPT-5 alongside BLEU. All three metrics—BLEU, Adequacy, and Fluency—produce a consistent ranking of systems:

Gemma 3 (1B) > LLaMA 3.2 (3B) > Qwen 3 (0.6B). Numerically, Gemma attains the highest BLEU (0.208) and the top GPT-only adequacy/fluency means (4.080/4.260), followed by LLaMA (0.072; 3.750/3.830) and Qwen (0.006; 2.720/3.100). This echoes the final 100-sample human+GPT study in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 and

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, indicating that a large GPT-only screening can correctly anticipate model ordering before a costlier human evaluation.

Beyond ranking,

Table 7 hints at where the models differ qualitatively. Adequacy spreads are larger than fluency spreads (e.g., 4.080 vs 3.750 vs 2.720 for adequacy, compared to 4.260 vs 3.830 vs 3.100 for fluency), mirroring the human finding that

meaning fidelity is harder than well-formedness. Notably, BLEU tracks adequacy at the model-average level (Gemma > LLaMA > Qwen) but is conservative in absolute values—especially for LLaMA and Qwen—reinforcing that reference overlap can understate quality when paraphrastic but faithful renditions are produced.

Practically, these preliminary results justify using GPT-only screening for triaging systems: when human budget is limited, screen at scale with GPT (and BLEU if references exist) to identify likely front-runners, then invest human effort where differences appear small or contentious. This workflow is consistent with the comparative patterns we later observe in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 and

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

4.4. Per-Aspect Dispersion and Human–GPT Means

Table 8 restates the per-aspect means and standard deviations for both human experts and GPT-5. Three observations emerge. First, GPT-5’s

means are uniformly higher than human means across models and aspects (e.g., for Gemma Morphosyntactic: H=3.870 vs GPT=4.25; for LLaMA Pragmatic: H=3.403 vs GPT=4.09), quantifying the leniency already visible in

Figure 2 relative to

Figure 1. Second, GPT-5’s

dispersion (SD) is comparable to or slightly higher than human SDs (e.g., Qwen Pragmatic: H=0.890 vs GPT=1.001), suggesting the LLM uses the full scale but hesitates to assign very low scores, which inflates means without collapsing variance.

Third, comparing across aspects, human SDs tend to be largest for

Semantic and

Pragmatic—the dimensions where nuanced disagreements are likeliest (e.g., Qwen Semantic SD=0.834; LLaMA Pragmatic SD=0.816). GPT-5 mirrors this pattern (e.g., LLaMA Semantic SD=1.055; Gemma Pragmatic SD=0.936), which aligns with our item-level examples where style/idiom and subtle meaning shifts drive disagreement. Together, Table 4 complements

Figure 1–2 by showing that the human–GPT difference is a mostly

level shift (bias) rather than a fundamental change in relative spreads, supporting the case for simple calibration of GPT-5’s scale.

4.5. Inter-Annotator Agreement by Model and Aspect

Table 9 reports Krippendorff’s

(ordinal) and averaged quadratic weighted

across humans+GPT-5, broken out by model and aspect. Agreement is

moderate overall, with the highest values for

Semantic—e.g., Gemma:

,

; Qwen:

,

—and lower values for

Morphosyntactic and

Pragmatic in LLaMA (e.g., Pragmatic

). Two patterns are noteworthy: (i) higher-quality outputs (Gemma) yield higher agreement, likely because errors are clearer (fewer borderline cases), and (ii)

Pragmatic shows the most variability across models, consistent with style/tone being more subjective and context-sensitive.

The closeness between and weighted within aspects indicates that pairwise rater consistency and multi-rater reliability tell a coherent story here. Importantly, these values are in the “moderate-to-substantial” band for Semantic and Pragmatic—precisely the dimensions we most care about for user-facing quality. This supports the reliability of the rubric and suggests our guidance was sufficiently specific for consistent judgments without over-constraining raters.

4.6. Annotator Competence (MACE) Across Aspects

Table 10 summarizes MACE competence (probability of correctness) per annotator and aspect. GPT-5 attains the highest or near-highest competence in

Morphosyntactic (0.651) and

Semantic (0.634), closely followed by the strongest human rater(s); in

Pragmatic, Evaluator 2 (0.601) slightly surpasses GPT-5 (0.572), reflecting the human advantage on cultural/register nuances already discussed. The spread among human annotators is modest (e.g., Semantic: 0.533–0.611), indicating a reasonably tight human panel.

Taken together,

Table 10 positions GPT-5 as a competent fourth rater that can reduce variance and cost in large-scale evaluations, while humans retain an edge on pragmatic subtleties. In practice, one could weight annotators by MACE competence in a pooled score or use GPT-5 for triage plus human adjudication on items likely to involve tone/idiom. We note that our Likert data were treated as categorical for MACE; while this is common, ordinal-aware alternatives (e.g., Gwet’s AC2) can be reported in parallel for completeness (we already supply Krippendorff’s

and weighted

).

4.7. Examples of Evaluation Differences

To illustrate the evaluation in concrete terms, it’s useful to consider a few example sentences and how each model performed:

-

Source: “Archimedes was an ancient Greek thinker, and ...” (continuation omitted).

- -

Qwen’s translation: “Archimedes adalah peneliti ahli Yunani sebelum...” (translates roughly to “Archimedes was a Greek expert researcher from before...”). This got Morph=3, Sem=2, Prag=3 from humans. They commented that “peneliti ahli” (“expert researcher”) is an odd choice for “thinker” (a semantic error) and the sentence trailed off inaccurately.

- -

LLaMA’s translation: “Archimedes adalah pemikir Yunani kuno...” (similar to Gemma’s but missing the article or some nuance) got Morph=5, Sem=4, Prag=4. Here all models were grammatically okay (hence Qwen Morph=3 not too low, just one minor grammar issue with “peneliti ahli”), but the semantic accuracy separated them – Qwen changed the meaning, LLaMA preserved meaning but omitted a slight detail, Gemma was spot on. GPT-5 gave scores of (3, 2, 3) to Qwen, (5, 4, 5) to Gemma, (5, 4, 4) to LLaMA – matching the human pattern, though GPT-5 rated Qwen’s grammar a bit higher than humans did (perhaps not catching the issue with “peneliti ahli”).

- -

Gemma’s translation: “Archimedes adalah seorang pemikir Yunani Kuno...” (literally “Archimedes was an Ancient Greek thinker...”), which is almost a perfect translation. Humans gave it Morph=5, Sem=5, Prag=5, a rare unanimous perfect score.

-

Source: “When the devil bites another devil, it actually…” (colloquial expression). This is tricky pragmatically because it’s figurative.

- -

Qwen’s translation actually mistranslated the structure, yielding something incoherent (Prag=1, Sem=1). In this case, GPT-5 somewhat overrated the pragmatic aspect for Gemma and LLaMA, giving them Prag=4 where humans gave 2. GPT-5 likely saw a grammatically correct sentence and, not recognizing the idiom, assumed it was acceptable, whereas human translators knew it missed the idiomatic meaning. This example illustrates a limitation: GPT-5 lacked cultural context to see the pragmatic failure.

- -

LLaMA’s translation was similarly literal and got Morph=4, Sem=4, Prag=2 as well.

- -

Gemma’s translation: “Ketika iblis menggigit iblis lainnya, sebenarnya...”, which is very literal (“When a devil bites another devil, actually...”). Indonesian evaluators noted this was grammatically fine but pragmatically odd – “iblis menggigit iblis” isn’t a known saying. They gave it Morph=4, Sem=4, Prag=2, citing that the tone didn’t carry over (maybe the source was implying conflict between bad people, an idiom that wasn’t localized).

-

Source: “The project is going very, very well, and…” (conversational tone).

- -

Qwen: “Proyek ini berjalan sangat, sangat baik, dan…” (literal translation; in Indonesian doubling “sangat” is a bit unusual but understandable). Humans: Morph=4 (a slight stylistic issue), Sem=5, Prag=3 (tone a bit off, could use “sangat baik sekali” instead).

- -

LLaMA: “Proyeknya berjalan dengan sangat baik, dan…” (more natural phrasing), got Morph=5, Sem=5, Prag=5.

- -

Gemma: “Proyek ini berjalan dengan sangat baik, dan…” (also excellent). Here all convey the meaning; it’s about style. Qwen’s phrasing was less idiomatic (hence pragmatic 3). GPT-5 gave Qwen a Prag=4 (it didn’t flag the style issue), showing again a slight leniency or lack of that nuance.

Overall, our results show each model’s strengths and weaknesses clearly, and GPT-5’s evaluation, while not identical to humans, is largely in agreement with human assessments on a broad scale. Gemma as a fine-tuned model excelled in both fluency and accuracy; it made the fewest errors, and those it did were minor (e.g., perhaps overly literal at times, but still correct). LLaMA had generally good translations but occasionally dropped details or used phrasing that was correct yet slightly unnatural. Qwen, being smallest and not specialized, had numerous issues: mistranslations (hence low semantic scores), and some clunky Indonesian constructions (lower pragmatic scores).

In terms of error types, by cross-referencing low-scoring cases we found that Qwen’s errors were often outright mistranslations or omissions. For example, it might translate “not uncommon” as “common” (flipping meaning) – a semantic mistake leading to a Semantic score of 1 or 2. LLaMA’s errors were more subtle – e.g., it might choose a wrong synonym or fail to convey a nuance like a modal particle, resulting in a Semantic 3 or 4 but rarely 1. Gemma’s “errors” were mostly stylistic choices or slight over-formality. There were almost no cases of Gemma clearly mistranslating content; its Semantic scores were mostly 4–5, indicating high adequacy. Its lowest pragmatic scores (a few 2’s) happened on idiomatic or colloquial inputs where a more culturally adapted translation existed but Gemma gave a literal rendering. This aligns with the known difficulty of pragmatic equivalence – something even professional translators must handle carefully.

Finally, it’s worth emphasizing that none of the models produced dangerously wrong outputs in our test. Unlike some reports of LLMs “hallucinating” in translations, we did not observe cases where entirely unrelated or extraneous information was introduced. This may be due to the relatively simple, self-contained nature of our test sentences. More complex inputs might provoke hallucinations or large errors, which would be important for future work to test (especially for tasks like summarizing then translating, or translating ambiguous inputs).

4.8. Results of the Classroom Evaluation Study

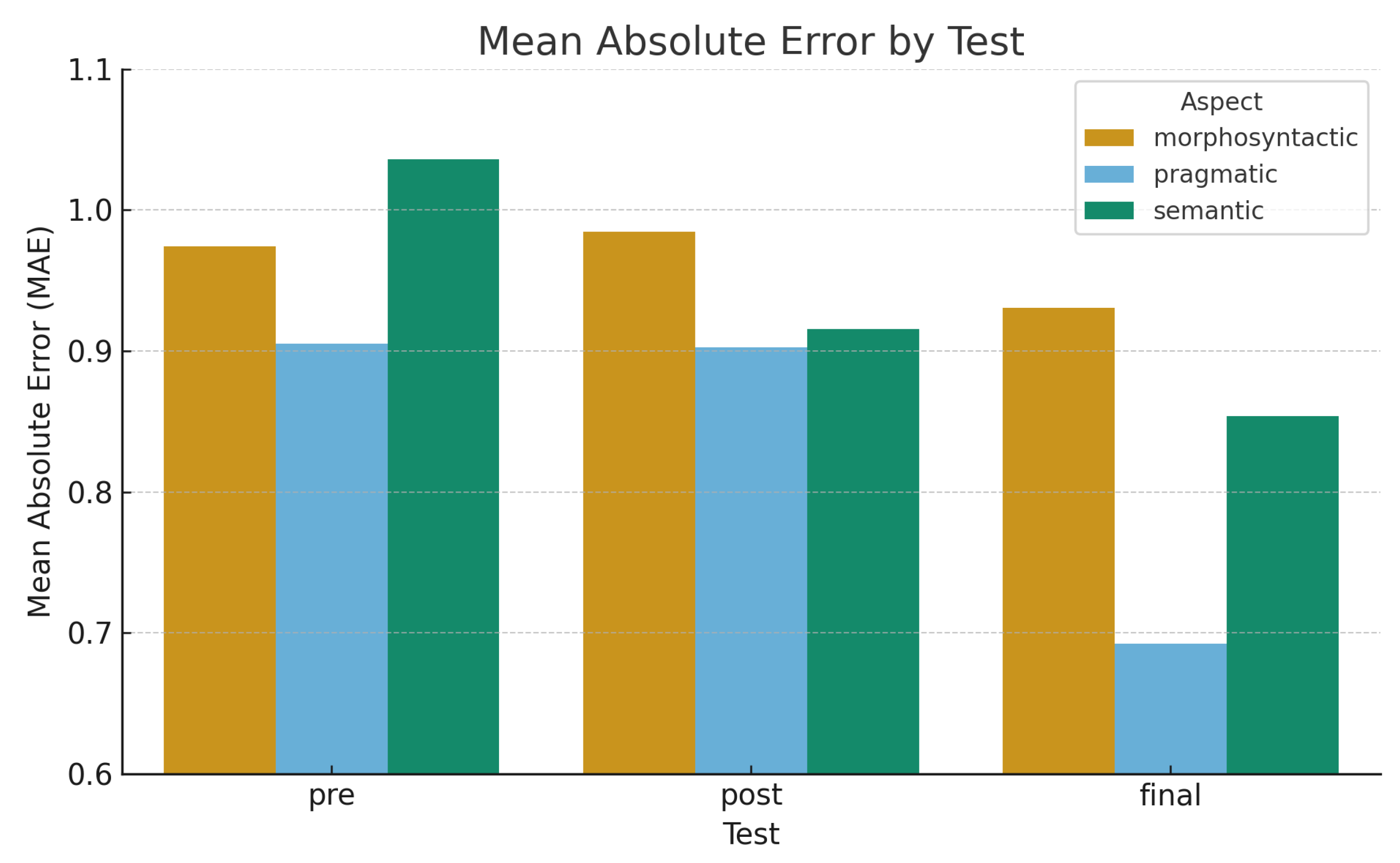

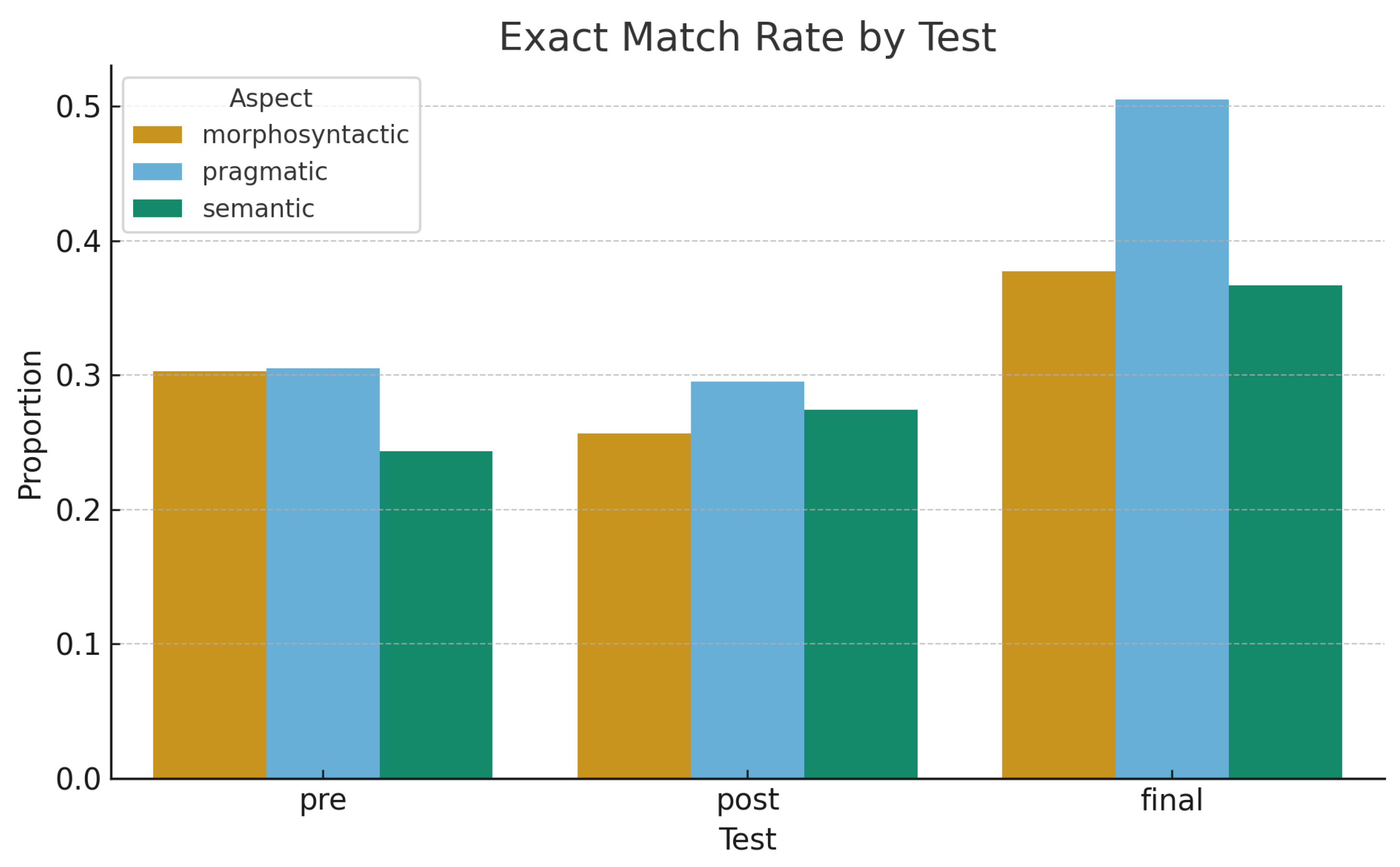

The descriptive statistics in

Table 11 show that rubric calibration improved both accuracy and consistency of student judgments. The overall MAE decreased steadily (0.97 → 0.83), indicating that students’ ratings became closer to the majority reference. The largest reduction appeared in the Semantic dimension (1.03 → 0.86), reflecting an improved grasp of meaning fidelity after rubric clarification. Morphosyntactic and Pragmatic dimensions also exhibited smaller yet steady improvements, implying that students grew more consistent in recognizing structural and stylistic quality. The Exact Match Rate increased from 0.30 to 0.50, meaning half of the students’ scores in the final test were identical to expert/GPT-5 judgments. The absence of “Outside” deviations (beyond

) further confirms that calibration aligned students’ interpretations with the rubric scale, minimizing rating variability.

Figure 5 illustrates how the mean absolute error (MAE) decreased across all tests and aspects, confirming a steady convergence toward the majority reference. Students initially showed greater variation in the Semantic aspect (highest MAE in the pre-test), suggesting difficulties in assessing meaning fidelity. After rubric clarification and in-class discussion, the MAE for the Semantic aspect dropped sharply in the post-test and continued to improve in the final test. Morphosyntactic and Pragmatic aspects also exhibited downward trends, indicating that students became more consistent in judging grammatical accuracy and tone appropriateness. Overall, the decreasing MAE trend demonstrates that rubric calibration and iterative evaluation practice effectively reduced scoring deviation across linguistic dimensions.

As shown in

Figure 6, the Exact Match Rate increased steadily from pre- to final test, indicating improved alignment between student and majority ratings. The most notable increase occurred in the final test, where half of all scores matched the majority exactly. This trend demonstrates that students internalized the scoring criteria and applied them consistently, even to new and unseen data. Combined with the MAE results, this pattern suggests that brief rubric calibration sessions, supported by GPT-5 majority feedback, significantly enhanced students’ evaluative precision.

5. Discussion

5.1. Specialized Smaller LLM vs General Larger LLM

One of the most striking findings is that Gemma 3 (1B) outperformed LLaMA 3.2 (3B) across all evaluation aspects. Despite having only one-third the parameters, Gemma 3 delivered higher Morphosyntactic, Semantic, and Pragmatic scores. This indicates that scaling laws alone do not guarantee better translation performance; model architecture and pretraining/data composition can be equally (or more) decisive for a given language pair and domain. In our setting—English→Indonesian—Gemma 3’s design and training mixture appear better aligned than the larger general model, leading to consistently stronger quality under human and GPT-5 evaluation.

LLaMA 3.2, as a downscaled version of a general LLM, presumably knows some Indonesian and can translate via its multilingual pre-training, but it may lack the robustness that Gemma exhibited in this evaluation. Our finding supports recent arguments that for many practical MT applications, fine-tuned NMT systems or fine-tuned LLMs can be more effective than using a large model zero-shot, especially when computational resources or latency is a concern. There is a cost-benefit angle too: Gemma 3 is much smaller and faster to run than a multi-billion-parameter model, making it attractive for deployment, yet we did not sacrifice quality – in fact, we gained quality. This is encouraging for communities working with languages that might not yet have a full GPT-5 level model: a moderately sized model focused on their translation needs could surpass using a giant LLM off the shelf.

5.2. Quality Aspect Analysis – Fluency vs Accuracy

By separating fluency (morphosyntax) and accuracy (semantic) in our evaluation, we confirmed a commonly observed trend: our models (like most neural MT systems) tend to be more fluent than they are accurate. All three models had their lowest human scores in the semantic dimension. Qualitatively, even Qwen’s outputs rarely devolved into word salad – they usually looked like plausible Indonesian sentences – but that did not mean they conveyed the right meaning. This fluency/accuracy gap is precisely why automatic metrics that rely on surface similarity (BLEU, etc.) can be fooled by fluent outputs that use different wording. Our human evaluators could detect when something was “off” in meaning. For example, Qwen translated “what makes this gift valuable is...” to a form that literally meant “what makes this gift so valuable is...”, dropping the emphasis – a subtle but important nuance. They penalized Semantic while still giving decent Morphosyntactic scores. In MT evaluation discussions, this touches on the concept of “critical errors” – an otherwise fluent translation might contain one mistranslated term (say, “respirator” vs “ventilator”) which is a critical error in context (medical) but a lexical choice that automatic metrics might not heavily penalize. Our multi-aspect approach catches that because Semantic accuracy would be scored low. The results therefore reinforce the value of multidimensional evaluation: we get a clearer diagnostic of systems. For instance, if one were to improve these models, the focus for Qwen and LLaMA should be on improving semantic fidelity (perhaps through better training or prompting), whereas their fluency is largely adequate. Meanwhile, to improve pragmatic scores, one might incorporate more colloquial or domain-specific parallel data so the model learns more natural phrasing and idioms (Gemma’s slight pragmatic edge likely comes from seeing genuine translations in training).

5.3. GPT-5 as an Evaluator – Potential and Pitfalls

The high correlation between GPT-5 and human scores () is a positive sign for using LLMs in evaluation. GPT-5 effectively identified the better system and, in many cases, gave similar relative scores to translations as humans did. This corroborates other findings that LLMs can serve as surrogate judges for translation quality. Such an approach could dramatically speed up MT development cycles – instead of running costly human evaluations for every tweak, researchers could use an LLM metric to get an estimate of quality differences. Our study adds evidence that GPT-5’s evaluations are fine-grained: it wasn’t just giving all outputs a high score or low score arbitrarily; it differentiated quality on a per-sentence level (with ∼0.8 correlation to human variation). For example, when a translation had a specific meaning error, GPT-5 often caught it and lowered the semantic score accordingly.

However, our analysis also highlights important caveats. GPT-5 was more lenient, especially on pragmatic aspects. In practical terms, if one used GPT-5 to evaluate two systems, it might overestimate their absolute performance. This is less of an issue if one is only looking at comparative differences (System A vs System B), since GPT-5 still ranked correctly. But it could be an issue if one tries to use GPT-5 to decide “Is this translation good enough to publish as-is?” – GPT-5 might say “yes” (score 5) when a human would still see room for improvement. This mirrors findings from recent G-Eval research that LLM evaluators may have a bias towards outputs that seem fluent. We saw that in our scatter plot: GPT-5 rarely gave low scores unless the translation was clearly bad. It’s almost as if GPT-5 was hesitant to be harsh, whereas human evaluators, perhaps following instructions, used the full scale more vigorously.

One reason for GPT-5’s leniency could be that the prompt did not enforce strict scoring guidelines. Our prompt was brief; GPT-5 might naturally cluster towards 3–5. If we had shown it examples of what constitutes a “1” vs “5” (calibration), maybe it would align better. There’s work to be done in prompt engineering for LLM evaluators: giving them reference criteria or anchor examples might reduce bias. Also, using chain-of-thought (asking GPT-5 to explain why it gave a score) could reveal whether it misses some considerations that humans have.

We also observed that GPT-5 may not capture cultural or contextual pragmatics as a human would. The idiom example (“devil bites another devil”) showed GPT-5 was satisfied with a literal translation that technically conveyed the words, whereas humans knew the phrase likely had a deeper meaning. This suggests that for truly evaluating pragmatic equivalence, human intuition is still essential. An LLM, unless explicitly trained on parallel examples of idioms and their translations, might not “know” that something is an idiom that fell flat in translation. In general, nuance detection is an area where current LLMs might fall short – e.g., detecting when a polite form should have been used but wasn’t, or when a translation, though accurate, sounds condescending or sarcastic in an unintended way.

Another interesting point is the self-referential bias: our GPT-5 evaluator was essentially assessing outputs from models that are also LLMs (though smaller). There’s a possibility that GPT-5’s own translation preferences influenced its judgment. For example, if GPT-5 tends to phrase something a certain way in Indonesian, and Gemma’s translation happened to match that phrasing, GPT-5 might inherently favor it as “correct.” If Qwen used a different phrasing that is still correct, GPT-5 might (implicitly) think it’s less natural since it’s not what GPT would do. This is speculative, but it raises the broader issue of evaluators needing diversity – perhaps the best practice in the future is to use a panel of LLM evaluators (from different providers or with different training) to avoid one model’s idiosyncrasies biasing the evaluation.

5.4. Implications for Indonesian MT

Our study shines some light on the state of English–Indonesian MT. Indonesian is a language with relatively simple morphology but some challenging aspects like reduplication and formality levels (e.g., pronouns and address terms vary by politeness). Our human evaluators noted that all models sometimes struggled with formality/tone. For instance, translating “you” can be “kamu”, “Anda”, or just omitted, depending on context and politeness. In a few sentences, models defaulted to a neutral tone that was acceptable, but not always contextually ideal. Gemma, probably due to seeing more examples, occasionally picked a more context-aware phrasing. For truly high-quality Indonesian translation, context (like who is speaking to whom) would be important – something our sentence-level approach did not incorporate. This points to the need for document-level or context-aware translation for handling pragmatics like formality. LLMs, by virtue of handling long contexts, might be advantageous here if they are used on whole documents.

We also observed how each model handled Indonesian morphology such as prefix/suffix usage. Indonesian uses affixes to adjust meaning (me-, -kan, -nya, etc.). Gemma had very few morphological errors, indicating it learned those patterns well. LLaMA had a handful of errors like dropping the me- prefix (common in MT when the model isn’t sure, it might leave a verb in base form). Qwen did this more often. These are relatively minor errors (often didn’t impede comprehension), but they do affect perceived fluency. It’s encouraging that the fine-tuned model essentially mastered them – showing that even a small model can capture such specifics with focused training, which an unfine-tuned LLM might not always do.

5.5. Human Evaluation for Research vs Real-World

Our human evaluators provided extremely valuable judgments, but such evaluations are time-consuming and costly in real-world settings (100 sentences × 3 people is 300 judgments). The fact that GPT-5 can approximate this suggests a hybrid approach: one could use GPT-5 to pre-score thousands of outputs to identify problematic cases, and then have humans focus on those or on a smaller subset for final verification. In a deployment scenario (say a translation service), GPT-5 could serve as a real-time quality estimator, flagging translations that are likely incorrect. However, as our results show, it might not flag everything a human would (especially subtle pragmatic issues), so some caution and possibly a margin of safety (e.g., only trust GPT-5’s “flag” if it’s really confident) should be implemented.

5.6. Toward Better LLM Translators

What do our findings imply for improving LLMs on translation tasks? One takeaway is that specialization for specific language pairs remains highly valuable. If resources allow, developing or adapting models explicitly for a given pair could yield better results than relying on a single general-purpose model to handle all directions. On the other hand, massive models like GPT-5 are already capable of producing strong translations if guided properly—so prompt design or few-shot demonstrations may help close the gap. In our evaluation, we tested Qwen, LLaMA, and Gemma in a zero-shot setting with a simple “Translate:” prompt. It is possible that providing a few in-context translation examples could have improved their outputs (especially for LLaMA). Exploring how much prompting strategies can help general LLMs approximate the performance of specialized models is an important direction for future work.

Another aspect is addressing the semantic accuracy gap. We observed that even the best-performing model (Gemma) lost points mainly on semantic nuances. Techniques to improve accuracy might include consistency checks (e.g., back-translation or source–target comparison), or integrating modules for factual verification. Since LLMs are prone to hallucination, one mitigation strategy is to encourage greater faithfulness to the source, for example by penalizing deviations during generation or by adopting constrained decoding and feedback-based training. Such approaches could reduce meaning drift while maintaining the high fluency that current models already achieve.

5.7. Error Profile and Improvement Targets

Our multi-aspect evaluation confirmed that translation quality is multi-faceted. We saw cases where a translation was grammatically flawless yet semantically flawed, or semantically accurate yet stylistically awkward. By capturing these differences, we can better target improvements. For example, all models in our study need improvement in semantic fidelity, as evidenced by semantic scores trailing fluency scores. Research into techniques to reinforce source–target alignment in LLM outputs—through constraints or improved training objectives—would directly address this gap. We also underline pragmatic and cultural nuances: even the best model (Gemma) occasionally failed to convey tone or idiomatic expression appropriately. Future work could augment training data with more colloquial and context-rich examples or use RLHF focusing on adequacy and style.

5.8. LLM Evaluator Agreement and Calibration

A novel component of our work was comparing GPT-5 with human evaluation. We found strong correlations ( overall), demonstrating the potential of LLM-based evaluation metrics. GPT-5 could rank translations and identify better outputs with high accuracy, effectively mimicking a human evaluator. However, we also observed a systematic bias: GPT-5 tended to give higher absolute scores and was less critical of pragmatic issues. Thus, while LLM evaluators are extremely useful, they need careful calibration before exclusive reliance. In the near term, a hybrid workflow—using LLM evaluators for rapid iteration and humans for final validation or to cover aspects the LLM might miss—is prudent.

5.9. Practical Use and Post-Editing Considerations

For real-world acceptability, the top-performing model (Gemma) achieved an average overall human score of ∼3.8/5, with many sentences rated 4–5. These translations are generally good, but not perfect; human post-editing remains advisable for professional use, particularly to correct meaning nuances or polish style. The predominant errors (minor omissions or stiffness) are typically quick to fix, implying substantial productivity gains from strong MT drafts. By contrast, Qwen often had major errors requiring extensive editing or retranslation; LLaMA’s output was decent and useful where perfect accuracy is not critical or as an editable draft. Matching the MT solution to the use case remains essential (e.g., high-stakes content favors the most accurate systems, potentially combined with human review).

5.10. Implications of the Classroom Evaluation Study

The classroom experiment demonstrates that rubric-based calibration effectively improved student evaluators’ alignment with expert and GPT-5 majority judgments. The strongest improvement occurred in the Semantic dimension, suggesting that students developed a better understanding of meaning fidelity after guided discussion. Morphosyntactic and Pragmatic dimensions also showed steady gains, implying enhanced awareness of grammatical accuracy and contextual tone.

Importantly, no “Outside” deviations (greater than ) occurred in any phase, indicating complete convergence within the rubric’s interpretive range. This confirms that rubric-guided classroom calibration narrows inter-rater variance and fosters evaluative literacy. Such outcomes underscore the educational potential of integrating LLM-supported majority scoring as a feedback reference, enabling translation students to self-correct and internalize consistent evaluation standards. The results of our experiments provide several insights relevant to machine translation research and the use of LLMs in translation.

5.11. Broader Impacts

Our findings have a few broader implications. First, for practitioners in translation and localization, it demonstrates that one does not necessarily need a 175B-parameter model to get good results – smaller tailored models like Gemma can suffice and even excel. This could democratize MT technology for languages where building a giant model is impractical: a focused approach with available parallel data can yield high quality. Second, the experiment suggests that human translators and AI evaluators can coexist in an evaluation workflow. By understanding where GPT-5 agrees or disagrees with humans, we can start to trust AI to do the heavy lifting of evaluation and involve human experts in edge cases or in refining the evaluation criteria.

For the research community, an interesting point is how to improve LLMs as evaluators further. If one could align GPT-5’s scoring more closely with MQM (perhaps by fine-tuning GPT-5 on a dataset of human evaluations), we might get an automatic evaluator that is not only correlated but also calibrated. That would be a game-changer for benchmarking models rapidly. Our results hint that GPT-5 already contains a lot of this capability intrinsically; it’s a matter of fine-tuning or prompting to bring it out in a trustworthy way.

5.12. Future Work

Building on this study, we identify several directions for further investigation:

Cross-lingual generalization: Extend evaluation to additional language pairs with diverse typological characteristics, including morphology-rich languages (e.g., Turkish, Finnish) and low-resource settings (e.g., regional Indonesian languages), to test the robustness and generalizability of our findings.

Document-level and discourse phenomena: Move beyond sentence-level evaluation to assess how models handle longer context. This includes measuring discourse-level coherence, consistency of terminology, pronominal and anaphora resolution, and appropriate management of register across paragraphs. Methods could involve evaluating paragraph- and document-level translations, designing rubrics for discourse quality, and exploiting LLMs’ extended context windows for both translation and evaluation.

Evaluator calibration: Refine prompts, explore in-context exemplars, or apply lightweight fine-tuning to GPT-5 (gpt-5-chat) as an evaluator in order to reduce its leniency and align it more tightly with rubric-anchored human severity. This could include calibration against reference human ratings on held-out data.

Explainable disagreement analysis: Collect structured rationales from GPT-5 and annotators to better diagnose systematic blind spots. For example, discrepancies on idiomaticity, politeness, or tone could be analyzed qualitatively and linked back to specific rubric dimensions.

Training-time feedback loops: Explore the use of GPT-5 as a “critic” to provide feedback signals during model training, prioritizing low-scoring phenomena (e.g., semantic fidelity errors or pragmatic mismatches). To mitigate evaluator bias, such loops should incorporate confidence thresholds and human-in-the-loop audits.

5.13. Limitations

While our study is comprehensive within its scope, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the test set is relatively small (100 sentences) and may not capture the full diversity of linguistic phenomena. It suffices to reveal clear model differences and common error types, but a larger and more varied set (spanning multiple domains and registers) would be necessary to increase confidence in generalization.

Second, our evaluation was conducted at the sentence level. We did not assess how these models handle document-level translation, which is critical for real deployment scenarios. Longer texts introduce discourse-level phenomena such as pronoun resolution, lexical consistency, topic continuity, and coherence across sentences. Document-level translation is precisely where LLMs, with their large context windows, may demonstrate distinctive strengths or weaknesses. Future work should therefore extend beyond isolated sentences to systematically examine English→Indonesian translation at the paragraph and document level.

Another limitation is that we only tested a single direction (En→Id). It is possible that the dynamics differ in the opposite direction, or for other language pairs. Indonesian→English might be easier in some respects (given that English dominates LLM pretraining data) but could pose different challenges, such as explicitly marking politeness or pronominal distinctions that are implicit in Indonesian. Moreover, languages with richer morphology or very different syntax (e.g., English↔Japanese) may produce different error patterns, perhaps making fluency harder to achieve. Thus, while our results align with trends noted in recent surveys, caution is warranted in extrapolating too broadly.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we presented a comprehensive evaluation of machine translation outputs from three LLM-based models (Qwen 3 (0.6B), LLaMA 3.2 (3B), Gemma 3 (1B)) on an English–Indonesian translation task, using both human raters and GPT-5 as evaluators. We structured the assessment along three key quality dimensions—morphosyntactic correctness, semantic accuracy, and pragmatic appropriateness—to gain deeper insights than a single metric could provide.

We presented a multidimensional evaluation of English–Indonesian MT that combines standard metrics (Adequacy, Fluency) with MQM-inspired linguistic dimensions (Morphosyntactic, Semantic, Pragmatic) and both human and LLM-based judgments. Across a 1,000-sample GPT-only screening and a 100-sample human+LLM study, all results consistently ranked the systems as Gemma 3 (1B) > LLaMA 3.2 (3B) > Qwen 3 (0.6B). Inter-annotator agreement (Krippendorff’s , weighted ) indicated moderate to substantial reliability, and MACE showed GPT-5 (gpt-5-chat) competence on par with the strongest human rater. GPT-5’s scores correlating strongly with human judgments () suggest it is an effective, scalable evaluator, albeit slightly lenient and in need of calibration. Overall, the findings support specialized mid-size models and rubric-guided LLM evaluation as a practical path to dependable MT assessment beyond BLEU.

Beyond numerical validation, this study extends MT evaluation into an educational context through a classroom experiment involving 26 translation students. The classroom results verified that rubric-based calibration can meaningfully transfer the multidimensional metrics to human learners. Students’ alignment with expert and GPT-5 majority judgments improved substantially, especially in the Semantic dimension, confirming the framework’s interpretability and usability in training evaluators. The mean absolute error (MAE) decreased from 0.97 to 0.83 and the Exact Match Rate increased from 0.30 to 0.50 across pre-, post-, and final-test phases. This pedagogical validation highlights the framework’s broader impact: beyond research evaluation, it serves as a practical tool for developing evaluative literacy and self-corrective feedback in translation education.

In future work, we plan to extend this multidimensional framework to additional language pairs and domains, explore automated calibration using GPT-based adaptive feedback, and integrate real-time classroom analytics to support scalable evaluator training.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., A.H.N., W.M., and T.D.; methodology, S.S., A.H.N., and T.D.; software, A.H.N. and W.M.; validation, S.S., A.H.N., W.M., T.D., and A.O.; formal analysis, S.S., A.H.N., W.M., and T.D.; investigation, A.H.N.and W.M.; resources, S.S., A.H.N., T.D. and Y.M.; data curation, S.S. and T.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H.N. and W.M.; writing—review and editing, A.H.N., W.M. and T.D.; visualization, A.H.N. and W.M.; supervision, A.O. and Y.M.; funding acquisition, S.S., A.H.N. and W.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Human evaluation scores by quality aspect for each model. Each group of bars corresponds to an evaluation aspect (Morphosyntactic, Semantic, Pragmatic). Within a group, the three bars represent the average score given to the translations of Qwen 3, LLaMA 3.2, and Gemma 3 respectively (from left to right). Error bars show ±1 standard deviation among the 100 test sentences. Gemma’s bars are highest in all categories, indicating its superior performance, while Qwen’s are lowest. Semantic scores are uniformly lower than the others, reflecting the challenge of meaning fidelity.

Figure 1.

Human evaluation scores by quality aspect for each model. Each group of bars corresponds to an evaluation aspect (Morphosyntactic, Semantic, Pragmatic). Within a group, the three bars represent the average score given to the translations of Qwen 3, LLaMA 3.2, and Gemma 3 respectively (from left to right). Error bars show ±1 standard deviation among the 100 test sentences. Gemma’s bars are highest in all categories, indicating its superior performance, while Qwen’s are lowest. Semantic scores are uniformly lower than the others, reflecting the challenge of meaning fidelity.

Figure 2.

GPT-5 evaluation scores by quality aspect for each model. The same layout as

Figure 1 is used, but the bars here show GPT-5’s average scoring of each model’s outputs. GPT-5’s evaluations also rank Gemma highest and Qwen lowest in all aspects. Note that GPT-5’s absolute scores are higher than the human scores (

Figure 1), especially for Pragmatic quality, suggesting a more lenient or optimistic evaluation compared to human judges.

Figure 2.

GPT-5 evaluation scores by quality aspect for each model. The same layout as

Figure 1 is used, but the bars here show GPT-5’s average scoring of each model’s outputs. GPT-5’s evaluations also rank Gemma highest and Qwen lowest in all aspects. Note that GPT-5’s absolute scores are higher than the human scores (

Figure 1), especially for Pragmatic quality, suggesting a more lenient or optimistic evaluation compared to human judges.

Figure 3.

Correlation between GPT-5 and human overall evaluation scores. Each point represents one translated sentence (from any of the three models). The x-axis is the human evaluators’ average overall score (mean of their three aspect scores) and the y-axis is GPT-5’s overall score (mean of its three aspect scores). The three colors denote the model: blue for Qwen, orange for LLaMA, green for Gemma. The dashed line is the diagonal . We see a strong positive correlation (Pearson ). GPT-5’s scores generally track the human scores – points do not scatter wildly. However, most points lie above the diagonal, reflecting that GPT-5 tends to give higher scores than humans for the same items. This is especially noticeable for the orange and green points (LLaMA and Gemma) in the upper-right: many of Gemma’s translations that humans rated around 4.0 overall were rated 4.5 or even 5 by GPT-5, hence appearing above the line. Qwen’s points (blue, in the lower left) also show GPT often rating them slightly higher than humans did.

Figure 3.

Correlation between GPT-5 and human overall evaluation scores. Each point represents one translated sentence (from any of the three models). The x-axis is the human evaluators’ average overall score (mean of their three aspect scores) and the y-axis is GPT-5’s overall score (mean of its three aspect scores). The three colors denote the model: blue for Qwen, orange for LLaMA, green for Gemma. The dashed line is the diagonal . We see a strong positive correlation (Pearson ). GPT-5’s scores generally track the human scores – points do not scatter wildly. However, most points lie above the diagonal, reflecting that GPT-5 tends to give higher scores than humans for the same items. This is especially noticeable for the orange and green points (LLaMA and Gemma) in the upper-right: many of Gemma’s translations that humans rated around 4.0 overall were rated 4.5 or even 5 by GPT-5, hence appearing above the line. Qwen’s points (blue, in the lower left) also show GPT often rating them slightly higher than humans did.

Figure 4.