Submitted:

17 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

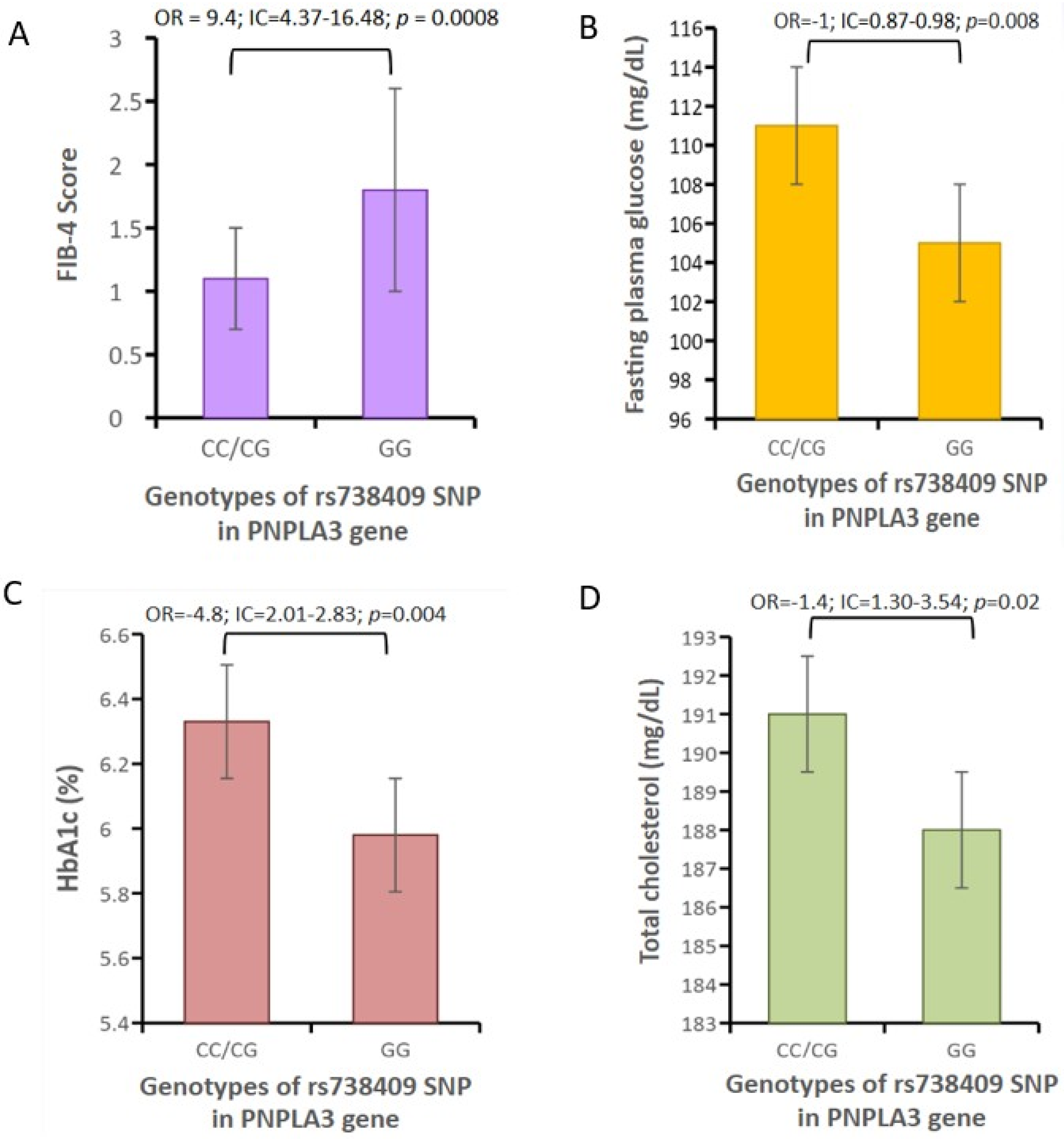

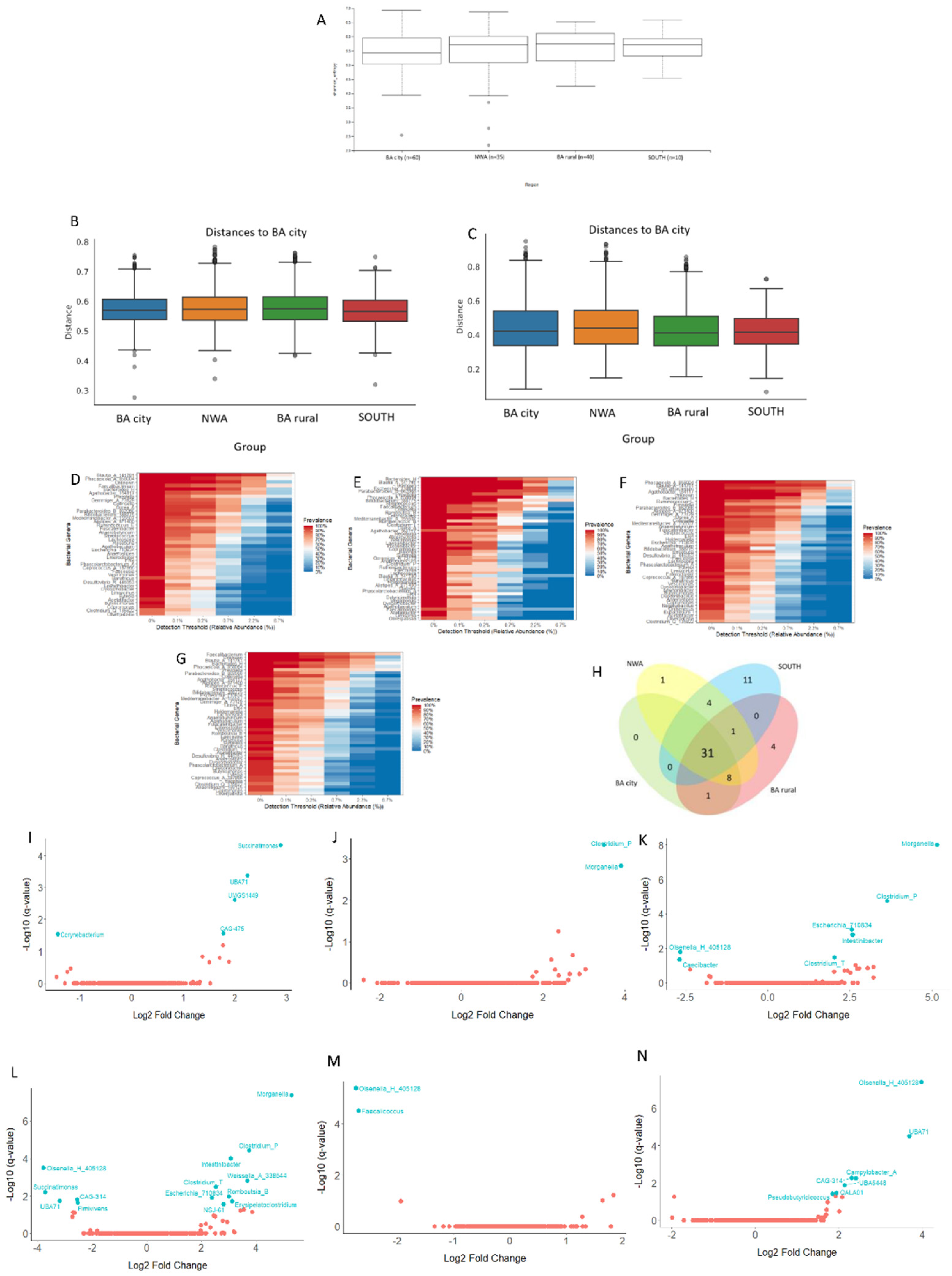

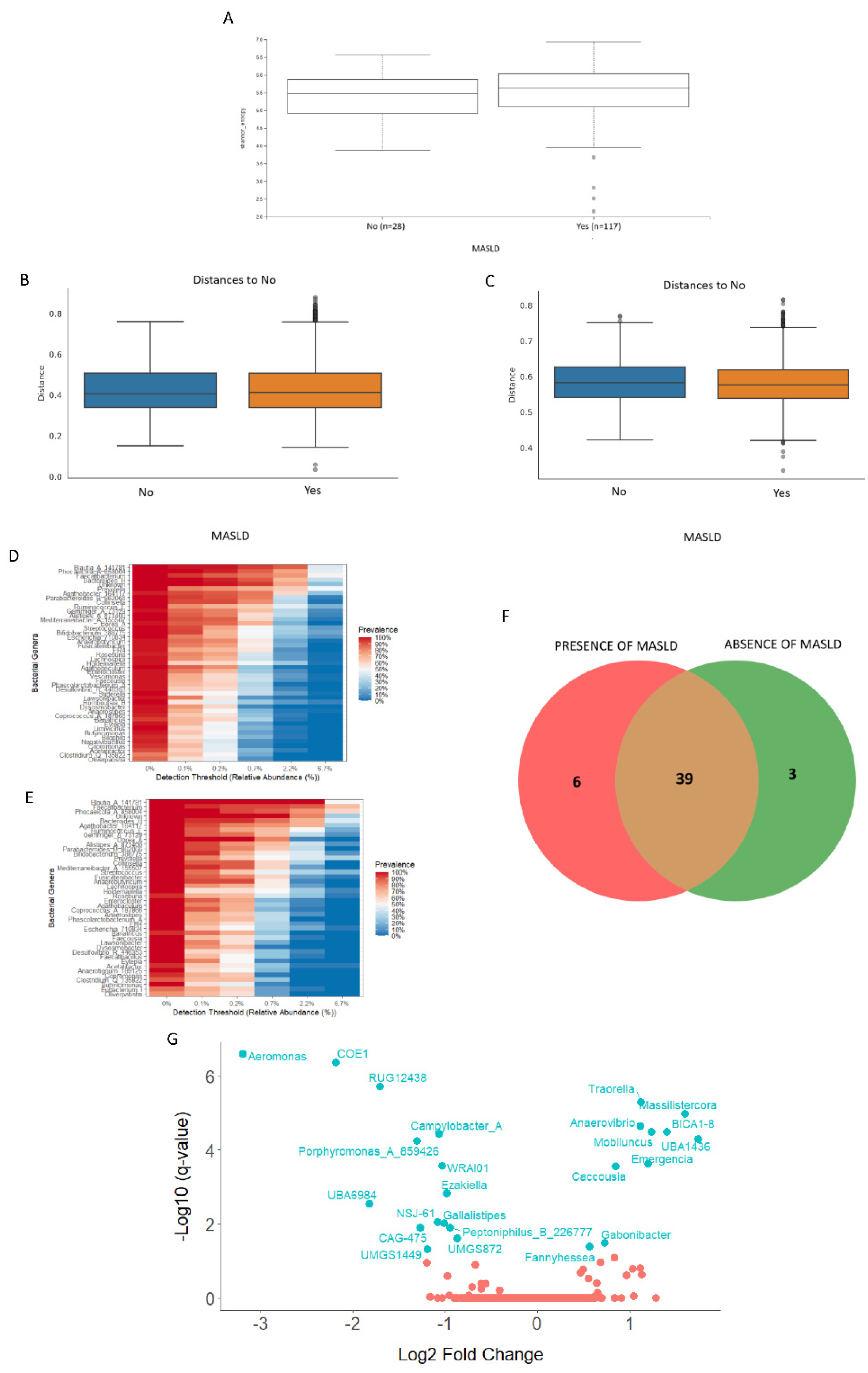

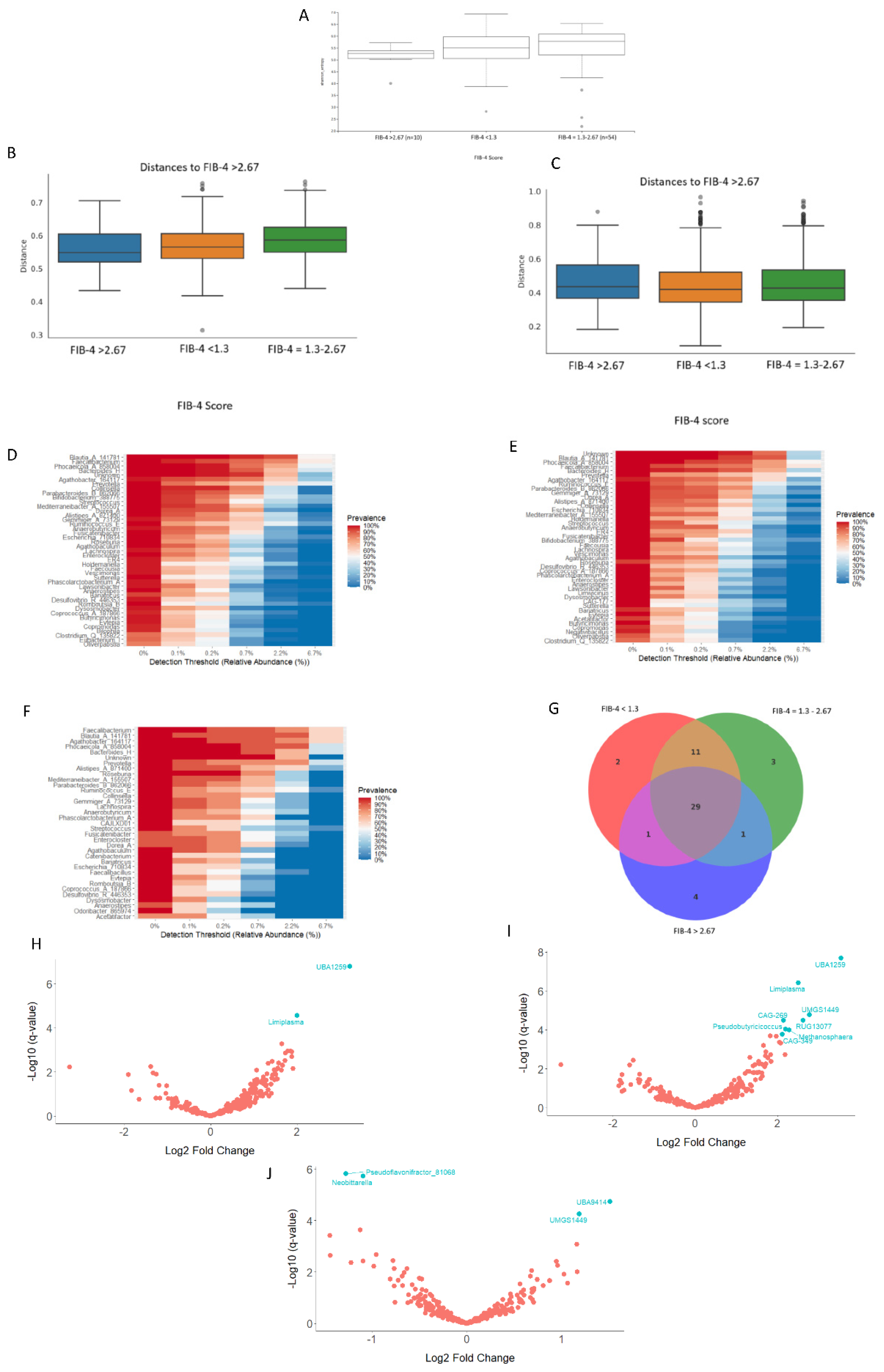

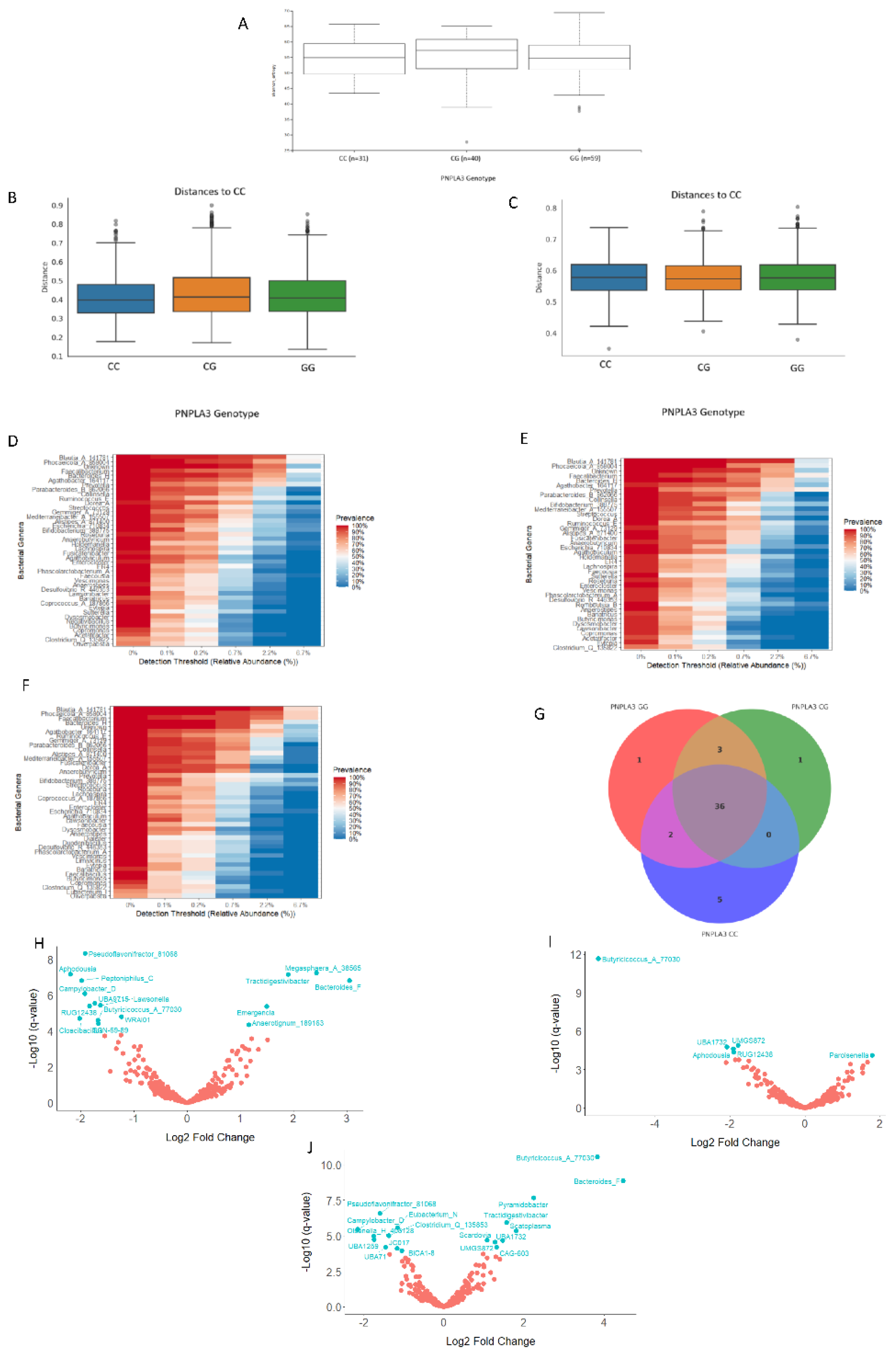

Background: Local specific biomarkers for MASLD risk stratification are urgently needed in Argentina. Aim: To characterized the interaction of gut microbiome signatures, genetic and clinical risk factors for MASLD in diabetics from different regions of Argentina. Material Methods: We recruited 214 diabetics from different regions. Anthropometric, clinical, and lifestyle data were obtained from all participants, who also underwent abdominal ultrasound for MASLD diagnosis and oral swabbing. PNPLA3 gene was amplified by PCR from the swabs, and rs738409 genotype was determined by bidirectional sequencing. To profile the MASLD-associated microbiome, stool was collected from 170 participants. V4 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed and reads were analysed using QIIME2 2024.10.1. R Studio 2022.12.0 was used for statistical analyses. Results: MASLD prevalence was 77.9%, with similar rates in all regions. FIB-4 scores <1.3 and >2.67 were detected in 55.3% and 7.4% of patients, respectively. Half of diabetics had PNPLA3-GG genotype, with the highest rates in Northwestern Argentina (64.9%; p=0.02 vs Buenos Aires). PNPLA3-GG genotype was an independent risk factor for FIB-4 score (p=0.0008), and a protective factor against HbA1c (p=0.004), fasting plasma glucose (p=0.008), and cholesterol levels (p=0.02). Marked regional differences were observed in microbiota diversity and composition in Argentina. After adjusting for geographical region, Negativibacillus genus was exclusively detected in diabetics with MASLD and GG carriers. Catenibacterium genus was related to FIB-4>2.67. Short-chain fatty acids-producing bacteria were linked to absence of MASLD. Conclusions: These specific signatures could be potentially useful as MASLD biomarkers for risk stratification in diabetics from Argentina.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data and Sample Collection

2.3. Isolation of Human Genomic DNA and Determination of PNPLA3 rs738409 Genotype

2.4. Microbial DNA Extraction, 16S rRNA Library Preparation and NGS

2.5. Bioinformatic Processing and Statistical Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic, Clinical and PNPLA3 Genetic Background of the Study Subjects

3.2. Correlations Between PNPLA3 rs738409 Genotype and Clinical Markers

3.3. Analyses of the Gut Bacterial Metagenome of T2DM Patients

3.3.1. Analyses of the Gut Bacterial Metagenome According to the Geographical Origin of the Samples

3.3.2. Analyses of the Gut Bacterial Metagenome According to the MASLD Diagnosis

3.3.3. Analyses of the Gut Bacterial Metagenome According to the FIB-4 Score

3.3.4. Analyses of the Gut Bacterial Metagenome According to the PNPLA3 rs738409 Genotype

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Younossi, Z.M.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Lazarus, J.V.; Wong, V.W.; Yilmaz, Y.; Duseja, A.; Eguchi, Y.; Castera, L.; Pessoa, M.G.; Oliveira, C.P.; et al. Global Consensus Recommendations for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2025, 169, 1017–1032.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanyal, A.J.; Castera, L.; Wong, V.W. Noninvasive Assessment of Liver Fibrosis in NAFLD. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 21, 2026–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinks, J.; Mascardi, M.F.; Gadano, A.; Marciano, S. Omics-based biomarkers as useful tools in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease clinical practice: How far are we? World J Gastroenterol 2024, 30, 1982–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kassas, M.; Othman, H.A.; Elbadry, M.; Alswat, K.; Yilmaz, Y. Risk Stratification of Patients with Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Steatotic Liver Disease: Steatohepatitis, Fibrosis, and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2025, 15, 102415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto Marques Souza de Oliveira, C.; Pinchemel Cotrim, H.; Arrese, M. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Risk Factors in Latin American Populations: Current Scenario and Perspectives. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2019, 13, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, J.P.; Díaz, L.A.; Dirchwolf, M.; Mark, H.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Vaughan, E.; Méndez-Sánchez, N.; Oliveira, C.P.; Gadano, A.; Arrese, M. NAFLD: Challenges and opportunities to address the public health problem in Latin America. Ann Hepatol 2021, 24, 100359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Kalligeros, M.; Henry, L. Epidemiology of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol 2025, 31, S32–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, L.A.; Arab, J.P.; Idalsoaga, F.; Perelli, J.; Vega, J.; Dirchwolf, M.; Carreño, J.; Samith, B.; Valério, C.; Moreira, R.O.; et al. Updated recommendations for the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) by the Latin American working group. Ann Hepatol 2025, 30, 101903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bril, F.; Gray, M. Noninvasive tests to identify liver fibrosis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease are affected by race. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2024, 32, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tincopa, M.A.; Díaz, L.A.; Huang, D.Q.; Arab, J.P.; Arrese, M.; Gadano, A.; Oliveira, C.P.; Bettencourt, R.; Madamba, E.; Kim, S.; et al. Disparities in screening and risk stratification for Hispanic adults with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Hepatology 2025, 81, 1792–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlitina, J.; Sookoian, S. Global Epidemiological Impact of PNPLA3 I148M on Liver Disease. Liver Int 2025, 45, e16123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaiou, M.; Joubert, O. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in NAFLD: Harnessing Epigenetic and Gut Microbiota Pathways for Targeted Therapeutic Approaches. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hullar, M.A.J.; Jenkins, I.C.; Randolph, T.W.; Curtis, K.R.; Monroe, K.R.; Ernst, T.; Shepherd, J.A.; Stram, D.O.; Cheng, I.; Kristal, B.S.; et al. Associations of the gut microbiome with hepatic adiposity in the Multiethnic Cohort Adiposity Phenotype Study. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1965463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belbin, G.M. , Nieves-Colón, M.A.; Kenny, E.E.; Moreno-Estrada, A.; Gignoux, C.R. Genetic diversity in populations across Latin America: implications for population and medical genetic studies. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2018, 53, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byndloss, M.; Devkota, S.; Duca, F.; Niess, J.H.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Orho-Melander, M.; Sanz, Y.; Tremaroli, V.; Zhao, L. The Gut Microbiota and Diabetes: Research, Translation, and Clinical Applications-2023 Diabetes, Diabetes Care, and Diabetologia Expert Forum. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 1491–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunta J, Marciano S, Alzueta G, Basbus M, Bruzzone S, Carulla R, Cicchitti A, et al. Prevalencia de Hígado Graso Asociado a Disfunción Metabólica (MASLD) en Pacientes con Diabetes tipo 2: Estudio Transversal Multicéntrico Argentino [Prevalence of Fatty Liver Associated with Metabolic Dysfunction (MASLD) in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: An Argentine Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study]. RSAD in press. 2025.

- Pontoriero, A.C.; Trinks, J.; Hulaniuk, M.L.; Caputo, M.; Fortuny, L.; Pratx, L.B.; Frías, A.; Torres, O.; Nuñez, F.; Gadano, A.; et al. Influence of ethnicity on the distribution of genetic polymorphisms associated with risk of chronic liver disease in South American populations. BMC Genet 2015, 16, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apprill, A.; Mcnally, S.; Parsons, R.; Weber, L. Minor Revision to V4 Region SSU RRNA 806R Gene Primer Greatly Increases Detection of SAR11 Bacterioplankton. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 2015, 75, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada, A.E.; Needham, D.M.; Fuhrman, J.A. Every base matters: assessing small subunit rRNA primers for marine microbiomes with mock communities, time series and global field samples. Environ Microbiol 2016, 18, 1403–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 21 Amir, A.; McDonald, D.; Navas-Molina, J.A.; Kopylova, E.; Morton, J.T.; Zech Xu, Z.; Kightley, E.P.; Thompson, L.R.; Hyde, E.R.; Gonzalez, A.; et al. Deblur Rapidly Resolves Single-Nucleotide Community Sequence Patterns. mSystems 2017, 2, e00191-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirarab, S.; Nguyen, N.; Warnow, T. SEPP: SATé-enabled phylogenetic placement. Pac Symp Biocomput 2012, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Kaehler, B.D.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.; Bolyen, E.; Knight, R.; Huttley, G.A.; Gregory Caporaso, J. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome 2018, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, D.; Jiang, Y.; Balaban, M.; Cantrell, K.; Zhu, Q.; Gonzalez, A.; Morton, J.T.; Nicolaou, G.; Parks, D.H.; Karst, S.M.; et al. Greengenes2 unifies microbial data in a single reference tree. Nat Biotechnol 2024, 42, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J. A New Method for Non-Parametric Multivariate Analysis of Variance. Austral Ecology 2001, 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Peddada, S.D. Multigroup analysis of compositions of microbiomes with covariate adjustments and repeated measures. Nat Methods 2024, 21, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microbiome R package. Available online: https://doi.org/10.18129/B9.bioc.microbiome (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer-Verlag: New York, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusi, K.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Apovian, C.M.; Balapattabi, K.; Bannuru, R.R.; Barb, D.; Bardsley, J.K.; Beverly, E.A.; Corbin, K.D.; ElSayed, N.A.; et al. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) in People With Diabetes: The Need for Screening and Early Intervention. A Consensus Report of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, 1057–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luisi, P.; García, A.; Berros, J.M.; Motti, J.M.B.; Demarchi, D.A.; Alfaro, E.; Aquilano, E.; Argüelles, C.; Avena, S.; Bailliet, G.; et al. Fine-scale genomic analyses of admixed individuals reveal unrecognized genetic ancestry components in Argentina. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0233808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senghor, B.; Sokhna, C.; Ruimy, R.; Lagier, J.C. Gut microbiota diversity according to dietary habits and geographical provenance. Hum Microbiome 2017, 7-8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Ji, X.; Liu, W. The gut microbiota facilitate their host tolerance to extreme temperatures. BMC Microbiol 2024, 24, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Lee, S.H.; Min, H.; Nam, T.W.; Hong, S.G.; Oh, B.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, Y.R.; Kim, B.S.; Seok, Y.J. Longitudinal gut microbiota dynamics in Antarctic research mission crews. Front Microbiol 2025, 16, 1593617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zou, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Z. The relationship of Megamonas species with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents revealed by metagenomics of gut microbiota. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 22001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaroque, C.; Chervy, M.; Gewirtz, A.T.; Chassaing, B. Social overcrowding impacts gut microbiota, promoting stress, inflammation, and dysglycemia. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 2000275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, F.B.; Maghini, D.; Oduaran, O.H.; Brewster, R.; Hulley, M.R.; Sahibdeen, V.; Norris, S.A.; Tollman, S.; Kahn, K.; Wagner, R.G.; et al. Short- and long-read metagenomics of urban and rural South African gut microbiomes reveal a transitional composition and undescribed taxa. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, J.; Lee, G.; You, H.J.; Joo, S.K.; Lee, D.H.; Ku, B.J.; Park, S.; Kim, W.; Ko, G. Gut microbiome signatures distinguish type 2 diabetes mellitus from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2021, 19, 5920–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, H.; Yang, X.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Q.; Wei, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lu, D.; Ye, L.; Cui, P.; et al. The role of gut microbiota in the occurrence and progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front Microbiol 2024, 14, 1257903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natividad, J.M.; Lamas, B.; Pham, H.P.; Michel, M.L.; Rainteau, D.; Bridonneau, C.; da Costa, G.; van Hylckama Vlieg, J.; Sovran, B.; Chamignon, C.; et al. Bilophila wadsworthia aggravates high fat diet induced metabolic dysfunctions in mice. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Mocanu, V.; Deehan, E.C.; Hotte, N.; Zhu, Y.; Wei, S.; Kao, D.H.; Karmali, S.; Birch, D.W.; Walter, J.; et al. Recipient microbiome-related features predicting metabolic improvement following fecal microbiota transplantation in adults with severe obesity and metabolic syndrome: a secondary analysis of a phase 2 clinical trial. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2345134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriachenko, Y.; Falalyeyeva, T.; Korotkyi, O.; Molochek, N.; Kobyliak, N. Crosstalk between gut microbiota and antidiabetic drug action. World J Diabetes 2019, 10, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speliotes, E.K.; Schneider, C.V. PNPLA3 I148M Interacts With Environmental Triggers to Cause Human Disease. Liver Int 2025, 45, e16106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, Y.; Lin, X.; Fang, Y.; Wan, J.; Wei, B. Associations of PNPLA3 rs738409 Polymorphism with Plasma Lipid Levels: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Horm Metab Res 2022, 54, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.M.; Leite, N.C.; França, P.H.; Cardoso, C.R.; Salles, G.F.; Villela-Nogueira, C.A. PNPLA3 gene polymorphism in Brazilian patients with type 2 diabetes: A prognostic marker beyond liver disease? Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2019, 29, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luukkonen, P.K.; Nick, A.; Hölttä-Vuori, M.; Thiele, C.; Isokuortti, E.; Lallukka-Brück, S.; Zhou, Y.; Hakkarainen, A.; Lundbom, N.; Peltonen, M.; et al. Human PNPLA3-I148M variant increases hepatic retention of polyunsaturated fatty acids. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e127902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentin, R.; Benhamed, F.; Pégorier, J.P.; Foufelle, F.; Viollet, B.; Vaulont, S.; Girard, J.; Postic, C. Polyunsaturated fatty acids suppress glycolytic and lipogenic genes through the inhibition of ChREBP nuclear protein translocation. J Clin Invest Oct 2005, 115, 2843–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Yahagi, N.; Izumida, Y.; Nishi, M.; Kubota, M.; Teraoka, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Matsuzaka, T.; Nakagawa, Y.; Sekiya, M.; et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids selectively suppress sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 through proteolytic processing and autoloop regulatory circuit. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 11681–11691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Adolph, T.E.; Moschen, A.R. Multiple Parallel Hits Hypothesis in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Revisited After a Decade. Hepatology 2021, 73, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ni, M.; Yu, H.; Wang, L.; Zhou, X.; Chen, T.; Liu, G.; Gao, Y. Gut Microbiota and Liver Fibrosis: One Potential Biomarker for Predicting Liver Fibrosis. Biomed Res Int 2020, 2020, 3905130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Fang, F.; Wu, K.; Song, J.; Li, Y.; Lu, X.; Liu, J.; Zhou, L.; Yu, W.; Yu, F.; et al. Gut microbiota-bile acid crosstalk regulates murine lipid metabolism via the intestinal FXR-FGF19 axis in diet-induced humanized dyslipidemia. Microbiome 2023, 11, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ALL (n=214) | BA City (n=71) | Rural BA (n=40) | NEA (n=20) | NWA (n=52) | SOUTH (n=31) | q Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 61.7 (14) | 62.5 (17.25) | 63 (13.5) | 63.6 (11) | 62.9 (10) | 59.9 (14) | 0.07 |

| Male gender, % | 51.60% | 51.60% | 55% | 40% | 61.10% | 60% | 0.2 |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 32.3 (7) | 32.5 (6.75) | 32.9 (5) | 32.2 (6.75) | 31.1 (5) | 31.8 (8) | 0.06 |

| Waist circumference, cm, median (IQR) | 105.5 (14) | 106.4 (22) | 105.7 (12.75) | 102.8 (9.75) | 104.3 (14.75) | 103.5 (17) | 0.006 |

| Time since T2DM diagnosis, years, median (IQR) | 11.1 (10.25) | 12.1 (10) | 12.6 (15.5) | 12.9 (14.25) | 11.1 (11) | 8.9 (7) | 0.1 |

| Physical activity, % | 48.9% | 50% | 28% | 82% | 59.4% | 35.5% | 0.005 |

| HbA1c, %, median (IQR) | 7 (1.5) | 6 (1.5) | 7 (1.55) | 6.95 (1.925) | 6.5 (1.9) | 8 (3.75) | 0.4 |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 116 (40.5) | 119 (40) | 116 (48.75) | 126.5 (35.5) | 115 (33) | 114 (107) | 0.5 |

| Total platelets, cells per mm3, median (IQR) | 234000 (73500) | 243000 (68550) | 212500 (93500) | 232000 (71500) | 223000 (70500) | 253000 (72000) | 0.38 |

| ALT, IU/L, median (IQR) | 23 (18.5) | 22 (15.5) | 22 (22.5) | 25.5 (10.35) | 24 (19) | 30 (34) | 0.11 |

| AST, IU/L, median (IQR) | 21 (11.5) | 19 (9.5) | 23 (13.5) | 24.5 (7.2) | 19 (16.5) | 26 (19) | 0.03 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 165.5 (53.5) | 152.5 (55.25) | 163 (55.5) | 175.5 (39.25) | 165 (53.5) | 187 (73) | 0.01 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 136 (77) | 112 (49) | 142 (80) | 166.5 (120.5) | 135 (76) | 166 (77) | 0.48 |

| High blood pressure, % | 68.90% | 74.20% | 77.50% | 80% | 48.60% | 61.30% | 0.03 |

| Cardiovascular risk, high to critic, % | 62.10% | 74.20% | 95% | 95% | 75.70% | 71% | 0.02 |

| PNPLA3, GG genotype, % | 50% | 40.30% | 45% | 60% | 64.90% | 51% | 0.14 |

| Diagnosis of MASL, % | 77.90% | 74.20% | 80% | 85% | 76% | 83.90% | 0.75 |

| FIB-4 score higher than 1.3, % | 44.7% | 32.3% | 65% | 55% | 40.5% | 35.5% | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).