Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

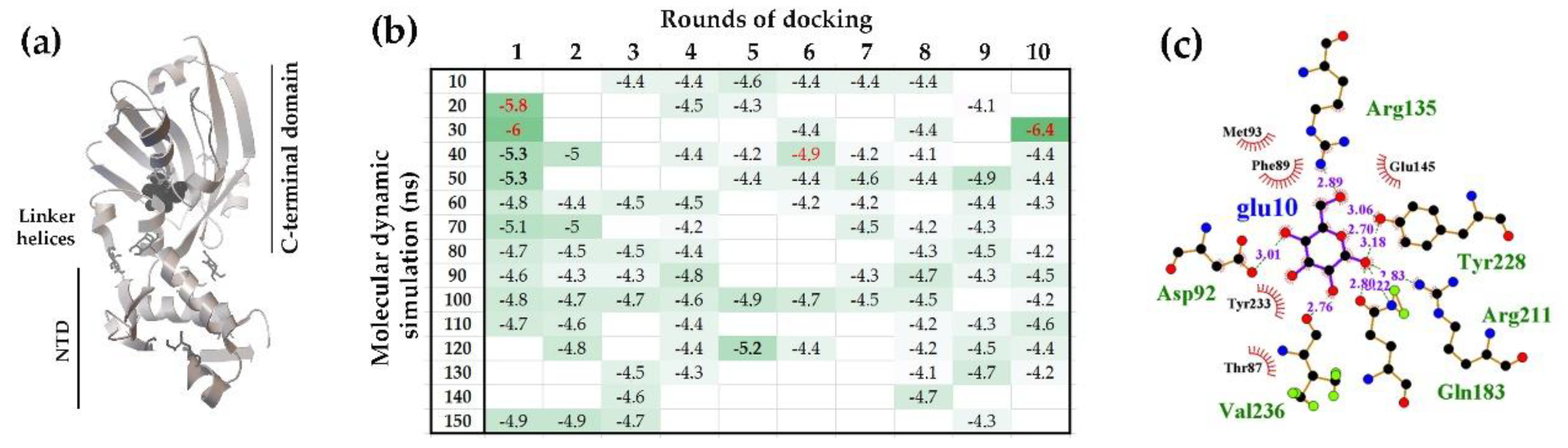

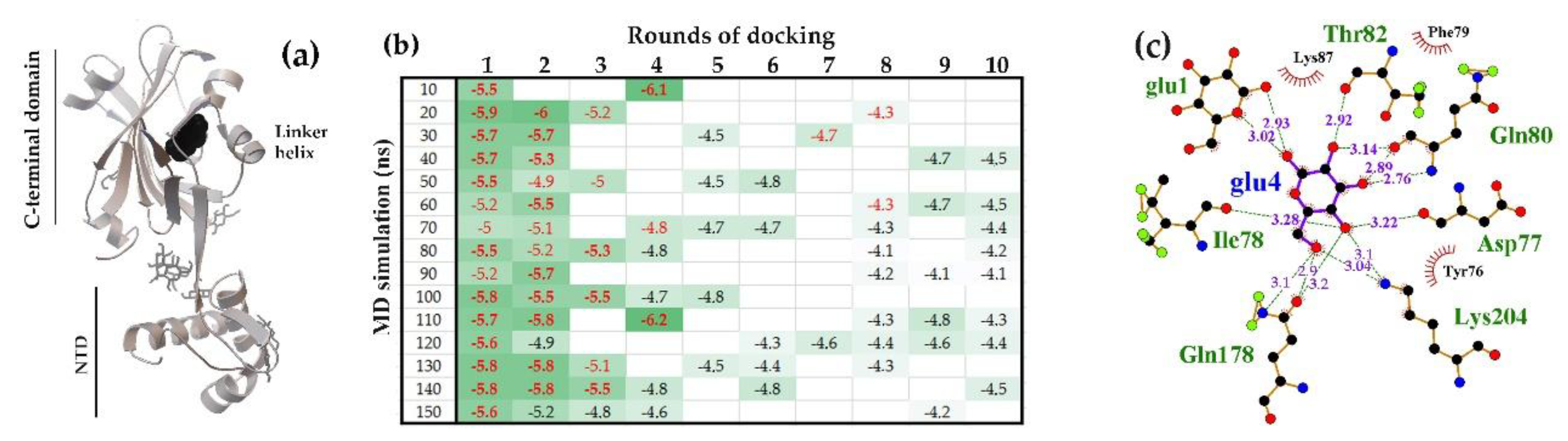

2.1. Modes of Carbohydrates Interaction with Inter-Domain Linkers of E. coli UxuR TF

2.1.1. The Flexible Inter-Domain Linker of the UxuR Monomer Exhibited Low Carbohydrate Binding Efficiency but Provided a Platform for their Clustering

2.1.2. Interacting with the UxuR Dimer, Carbohydrates do not Form Clusters with Inter-Domain Linkers, but Connect them to the α-Helix of the Effector Domain.

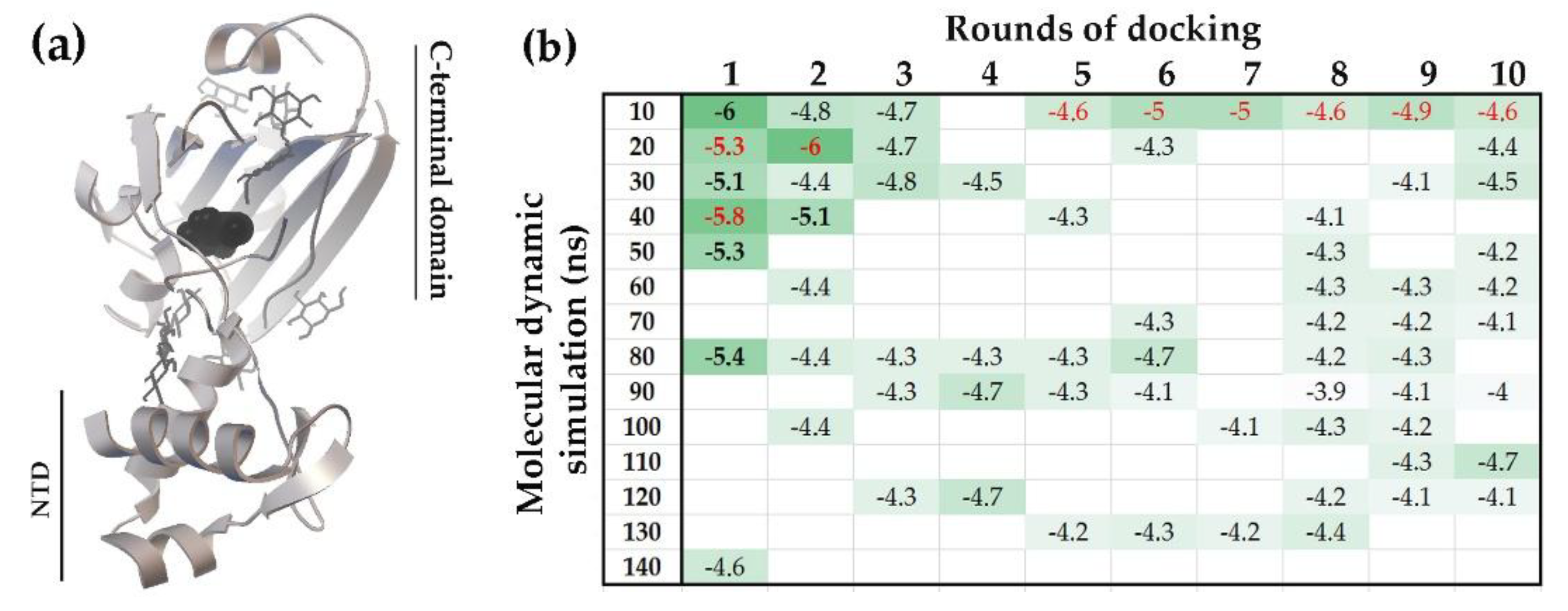

2.2. Similarities and Diversity of D-Glucose Binding Modes with Unstructured Linkers of Other Transcription Factors

2.2.1. The Linker-Separated Subdomains of E. coli GntR and B. subtilis AraR, Formed High-Affinity Binding Pockets for D-Glucose but Differed in its Non-Specific Binding

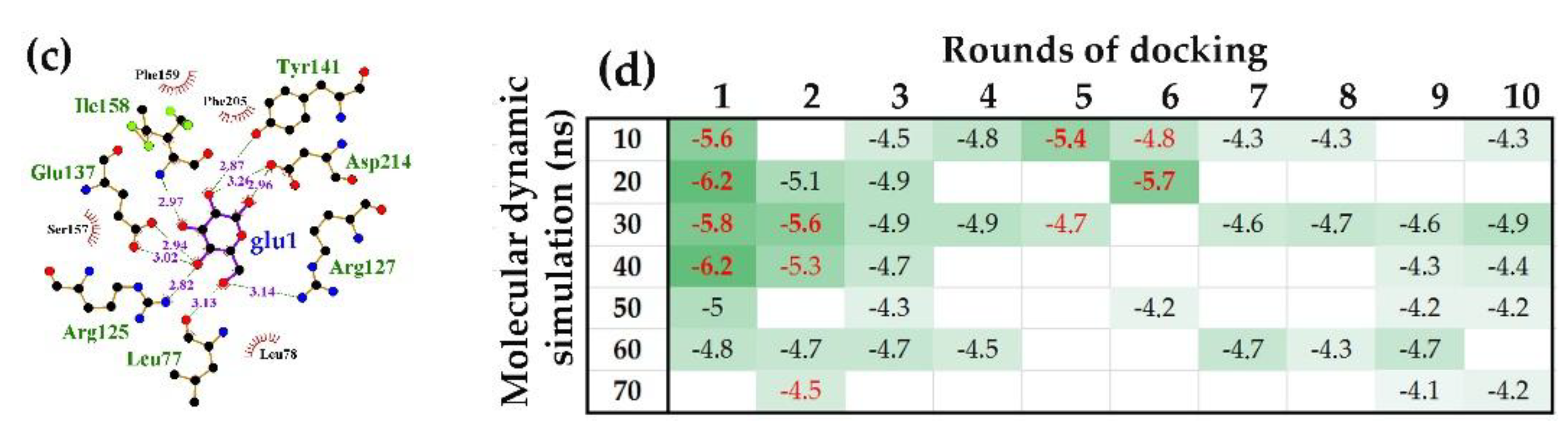

2.2.2. The Patterns of the NagR and FarR Interaction with D-glucose Correlate with the Structure of the Polypeptide Chain Forming a High-Affinity Binding Site in the CTD

2.2.3. A putative Transcription Factor YydK with structural Homology to NagR and FarR Interacted with D-Glucose in a NagR-like Manner

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Structural Models of Carbohydrates Used in the Study

4.1. Structural Models of Transcription Factors Used in the Study

4.2. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

4.3. Flexible Molecular Docking

4.4. Statistics

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Browning, D.F.; Busby, S.J. Local and global regulation of transcription initiation in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 2016, 14, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busby, S.J.W. Transcription activation in bacteria: ancient and modern. Microbiology (Reading) 2019, 165, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Bautista, E.; Hernandez-Guerrero, R.; Huerta-Saquero, A.; Tenorio-Salgado, S.; Rivera-Gomez, N.; Romero, A.; Ibarra, J.A.; Perez-Rueda, E. Deciphering the functional diversity of DNA-binding transcription factors in Bacteria and Archaea organisms. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0237135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inukai, S.; Kock, K.H.; Bulyk, M.L. Transcription factor-DNA binding: beyond binding site motifs. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2017, 43, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleif, R.F. Modulation of DNA binding by gene-specific transcription factors. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 6755–6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.J.; Schleif, R. Helical Behavior of the Interdomain Linker of the Escherichia coli AraC Protein. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 2867–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Richet, E.; Han, Z.; Chai, J. Structural basis for negative regulation of the Escherichia coli maltose system. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, R.; Nagarajaram, H.A. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: An Overview. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 14050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, N.E. The functional importance of structure in unstructured protein regions. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2019, 56, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, H.J.; Wright, P.E. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005, 6, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Vucetic, S.; Iakoucheva, L.M.; Oldfield, C.J.; Dunker, A.K.; Uversky, V.N.; Obradovic, Z. Functional anthology of intrinsic disorder. 1. Biological processes and functions of proteins with long disordered regions. J Proteome Res 2007, 6, 1882–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Lee, R.; Buljan, M.; Lang, B.; Weatheritt, R.J.; Daughdrill, G.W.; Dunker, A.K.; Fuxreiter, M.; Gough, J.; Gsponer, J.; Jones, D.T.; Kim, P.M.; Kriwacki, R.W.; Oldfield, C.J.; Pappu, R.V.; Tompa, P.; Uversky, V.N.; Wright, P.E.; Babu, M.M. Classification of intrinsically disordered regions and proteins. Chem Rev 2014, 114, 6589–6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R; Raduly, Z.; Miskei, M.; Fuxreiter, M. Fuzzy complexes: Specific binding without complete folding. FEBS Lett 2015, 589, 2533–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgia, A.; Borgia, M. B.; Bugge, K.; Kissling, V.M.; Heidarsson, P.O.; Fernandes, C.B.; Sottini, A.; Soranno, A.; Buholzer, K.J.; Nettels, D.; Kragelund, B.B.; Best, R.B.; Schuler, B. Extreme disorder in an ultrahigh-affinity protein complex. Nature 2018, 555(7694), 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.J.; Sodhi, J.S.; McGuffin, L.; Buxton, B.F.; Jones, D.T. Prediction and functional analysis of native disorder in proteins from the three kingdoms of life. J Mol Biol. 2004, 337, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.; Oldfield, C.J.; Radivojac, P.; Vacic, V.; Cortese, M.S.; Dunker, A.K.; Uversky, V.N. ; Analysis of molecular recognition features (MoRFs). J Mol Biol. 2006, 362, 1043–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Dunker, A.K.; Uversky, V.N.; Kurgan, L. Molecular recognition features (MoRFs) in three domains of life. Mol Biosyst 2016, 12, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Y.Q.; Otting, G.; Furukubo-Tokunaga, K.; Affolter, M.; Gehring, W.J.; Wüthrich, K. NMR structure determination reveals that the homeodomain is connected through a flexible linker to the main body in the Drosophila antennapedia protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 10738–10742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompa, P.; Schad, E.; Tantos, A.; Kalmar, L. Intrinsically disordered proteins: emerging interaction specialists. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2015, 35, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Y.; Maffei, M.; Igea, A.; Amata, I.; Gairí, M.; Nebreda, A.R.; Bernadó, P.; Pons, M. Lipid binding by the Unique and SH3 domains of c-Src suggests a new regulatory mechanism. Sci Rep 2013, 3, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxreiter, M. Classifying the Binding Modes of Disordered Proteins. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 8615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.; Teilum, K.; Kragelund, B.B. Behaviour of intrinsically disordered proteins in protein-protein complexes with an emphasis on fuzziness. Cell Mol Life Sci 2017, 74, 3175–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miskei, M.; Horvath, A.; Vendruscolo, M.; Fuxreiter, M. Sequence-Based Prediction of Fuzzy Protein Interactions. J Mol Biol 2020, 432, 2289–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaleo, E.; Saladino, G.; Lambrughi, M.; Lindorff-Larsen, K.; Gervasio, F.L.; Nussinov, R. The role of protein loops and linkers in conformational dynamics and allostery. Chem Rev 2016, 116, 6391–6423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhou, H.X. Protein allostery and conformationa dynamics. Chem Rev 2016, 116, 6503–6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Shen, C.; Wang, T.; Quan, J. Structural basis for the inhibition of polo-like kinase 1. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2013, 20, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Nussinov, R. The mechanism of ubiquitination in the cullin-RING E3 ligase machinery: conformational control of substrate orientation. PLoS Comput Biol 2009, 5, e1000527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuravleva, A.; Gierasch, L.M. Allosteric signal transmission in the nucleotide-binding domain of 70-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp70) molecular chaperones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 108, 6987–6992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, R. S.; Khosla, C. Role of linkers in communication between protein modules. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2000, 4, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Tsai, C-J. ; Haliloğlu, T.; Nussinov, R. Dynamic Allostery: Linkers Are Not Merely Flexible. Structure 2011, 19, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, P.E.; Dyson, H.J. Linking folding and binding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2009, 19, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.J.; Ma, B.; Kumar, S.; Son, H. W. L.; Nussinov, R. Protein folding: binding of conformationally fluctuating building blocks via population selection. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol 2001, 36(5), 399–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammes, G.G.; Chang, Y.C.; Oas, T.G. Conformational selection or induced fit: a flux description of reaction mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009, 106(33), 13737–13741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiberger, M.I.; Wolynes, P.G.; Ferreiro, D.U.; Fuxreiter, M. Frustration in Fuzzy Protein Complexes Leads to Interaction Versatility. J Phys Chem B 2021, 125, 2513–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüschweiler, S.; Schanda, P.; Kloiber, K.; Brutscher, B.; Kontaxis, G.; Konrat, R.; Tollinger. M. Direct observation of the dynamic process underlying allosteric signal transmission. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 3063–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Velos, J.; Gardino, A.; Kivenson, A.; Karplus, M.; Kern, D. Segmented transition pathway of the signaling protein nitrogen regulatory protein C. J Mol Biol 2009, 392, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, D.R.; Wilson, J.J.; Kovall, R. A RAM-induced allostery facilitates assembly of a notch pathway active transcription complex. J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283, 14781–14791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, G.; Keskin, O.; Gursoy, A.; Nussinov, R. Allostery and population shift in drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol 2010, 10, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenakin, T.; Miller, L.J. Seven transmembrane receptors as shape-shifting proteins: the impact of allosteric modulation and functional selectivity on new drug discovery. Pharmacol. Rev 2010, 62, 265–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, K.; Ma, B.; Nussinov, R. Is allostery an intrinsic property of all dynamic proteins? Proteins 2004, 57, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Nussinov, R. Allostery: An Overview of Its History, Concepts, Methods, and Applications. PLoS Comput Biol 2016, 12, e1004966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobi, D.; Bahar, I. Structural changes involved in protein binding correlate with intrinsic motions of proteins in the unbound state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 18908–18913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussinov, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Jang, H. Protein conformational ensembles in function: roles and mechanisms. RSC Chem Biol 2023, 4, 850–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.J.; Benson, M.; Smith, R.D.; Carlson, H.A. Inherent versus induced protein flexibility: Comparisons within and between apo and holo structures. PLoS Comput Biol 2019, 15, e1006705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, F.; Weikl, T.R. How to Distinguish Conformational Selection and Induced Fit Based on Chemical Relaxation Rates. PLoS Comput Biol 2016, 12, e1005067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehr, D.D. During transitions proteins make fleeting bonds. Cell 2009, 139, 1049–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardino, A.K.; Villali, J.; Kivenson, A.; Lei, M.; Liu, C.F.; Steindel, P.; Eisenmesser, E.Z.; Labeikovsky, W.; Wolf-Watz, M.; Clarkson, M.W.; Kern, D. Transient non-native hydrogen bonds promote activation of a signaling protein. Cell 2009, 139, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Sol, A.; Tsai, C.J.; Ma, B.; Nussinov, R. The origin of allosteric functional modulation: multiple pre-existing pathways. Structure 2009, 17, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Arya, G.; Mishra, R.; Singla, S.; Pratap, A.; Upadhayay, K.; Sharma, M.; Chaba, R. ; Molecular mechanisms underlying allosteric behavior of Escherichia coli DgoR, a GntR/FadR family transcriptional regulator. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53, gkae1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sapienza, P.J.; Ke, H.; Chang, A.; Hengel, S.R.; Wang, H.; Phillips, G.N.; Lee, A.L. Crystallographic and nuclear magnetic resonance evaluation of the impact of peptide binding to the second PDZ domain of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1E. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 9280–9291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.J.; del Sol, A.; Nussinov, R. Allostery: absence of a change in shape does not imply that allostery is not at play. J. Mol. Biol 2008, 378, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenakin, T. G protein coupled receptors as allosteric proteins and the role of allosteric modulators. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res 2010, 30, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlović-Lažetić, G.M.; Mitić, N.S.; Kovačević, J.J.; Obradović, Z.; Malkov, S.N.; Beljanski, M.V. Bioinformatics analysis of disordered proteins in prokaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics 2011, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sormanni, P.; Piovesan, D.; Heller, G. T.; Bonomi, M.; Kukic, P.; Camilloni, C.; Fuxreiter, M.; Dosztanyi, Z.; Pappu, R.V; Babu, M.M.; Longhi, S.; Tompa, P.; Dunker, A.K.; Uversky, V.N; Tosatto, S.C.E; Vendruscolo, M. Simultaneous quantification of protein order and disorder. Nat. Chem. Biol 2017, 13, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, O.M.; Torpey, J.H.; Isaacson, R.L. Intrinsically disordered proteins: modes of binding with emphasis on disordered domains. Open Biol 2021, 11, 210222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadi, M.; Anyango, S.; Deshpande, M.; Nair, S.; Natassia, C.; Yordanova, G.; Yuan, D.; Stroe, O.; Wood, G.; Laydon, A.; Žídek, A.; Green, T.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Petersen, S.; Jumper, J.; Clancy, E.; Green, R.; Vora, A.; Lutfi, M.; Figurnov, M.; Cowie, A.; Hobbs, N.; Kohli, P.; Kleywegt, G.; Birney, E.; Hassabis, D.; Velankar, S. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50(D1), D439–D444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; da Costa Gonzales, L.J.; Bowler-Barnett, E.H.; Rice, D.L.; Kim, M.; Wijerathne, S.; Luciani, A.; Kandasaamy, S.; Luo, J.; Watkins, X.; Turner, E.; Martin, M.J. UniProt Consortium The UniProt website API: facilitating programmatic access to protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53(W1), W547–W553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizovtseva, E.; Polikanov, Y.; Kulaeva, O.; Clauvelin, N.; Postnikov, Y. V.; Olson, W. K.; Studitsky, V.M. Opposite effects of histone H1 and HMGN5 protein on distant interactions in chromatin. Mol. Biol 2019, 53, 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, I.; Nardocci, G.; Schwartz, U.; Babl, S.; Barros, M.; Carrasco-Wong, I.; Imhof, A.; Montecino, M.; Längst, G. HMGN5, an RNA or Nucleosome binding protein-potentially switching between the substrates to regulate gene expression. bioRxiv 2022, 2022–07. [Google Scholar]

- Moses, D.; Yu, F.; Ginell, G.M.; Shamoon, N.M.; Koenig, P.S.; Holehouse, A.S.; Sukenik, S. Revealing the Hidden Sensitivity of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins to their Chemical Environment. J Phys Chem Lett 2020, 11, 10131–10136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, H.; Gama-Castro, S.; Lara, P.; Mejia-Almonte, C.; Alarcón-Carranza, G.; López-Almazo, A.G.; Betancourt-Figueroa, F.; Peña-Loredo, P.; Alquicira-Hernández, S.; Ledezma-Tejeida, D.; Arizmendi-Zagal, L.; Méndez-Hernández, F.; Díaz-Gómez, A.K.; Ochoa-Praxedis, E.; Muñiz-Rascado, L.J.; García-Sotelo, J.S.; Flores-Gallegos, F.A.; Gómez, L.; Bonavides-Martínez, C.; del Moral-Chávez, V.M.; Hernández-Álvarez, A.J.; Santos-Zavaleta, A.; Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Gelpí, J.L.; Collado-Vides, J. RegulonDB v12.0: a comprehensive resource of transcriptional regulation in E. coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52(D1), D255–D264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvorova, I.A.; Korostelev, Y.D.; Gelfand, M.S. GntR Family of Bacterial Transcription Factors and Their DNA Binding Motifs: Structure, Positioning and Co-Evolution. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0132618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, I.; Hernandez-Guerrero, R.; Mendez-Monroy, P.E.; Martinez-Nuñez, M.A.; Ibarra, J.A.; Pérez-Rueda, E. Evaluation of the Abundance of DNA-Binding Transcription Factors in Prokaryotes. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rueda, E.; Hernandez-Guerrero, R.; Martínez-Núñez, M.A.; Armenta-Medina, D.; Sanchez, I.; Ibarra, J.A. Abundance, diversity and domain architecture variability in prokaryotic DNA-binding transcription factors. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0195332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigali, S.; Derouaux, A.; Giannotta, F.; Dusart, J. Subdivision of the helix-turn-helix GntR family of bacterial regulators in the FadR, HutC, MocR, and YtrA subfamilies. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 12507–12515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigali, S.; Schlicht, M.; Hoskisson, P.; Nothaft, H.; Merzbacher, M.; Joris, B.; Titgemeyer, F. Extending the classification of bacterial transcription factors beyond the helix-turn-helix motif as an alternative approach to discover new cis/trans relationships. Nucleic Acids Res 2004, 32, 3418–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, D. Allosteric control of transcription in GntR family of transcription regulators: A structural overview. IUBMB Life 2015, 67, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutukina, M.N.; Potapova, A.V.; Vlasov, P.K.; Purtov, Y.A.; Ozoline, O.N. Structural modeling of the ExuR and UxuR transcription factors of E. coli: search for the ligands affecting their regulatory properties. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2016, 34, 2296–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arya, G.; Pal, M.; Sharma, M.; Singh, B.; Singh, S.; Agrawal, V.; Chaba, R. Molecular insights into effector binding by DgoR, a GntR/FadR family transcriptional repressor of D-galactonate metabolism in Escherichia coli. Molecular Microbiology. 2021, 115, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollingsworth, S.A.; Dror, R.O. Molecular Dynamics Simulation for All. Neuron 2018, 99, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDockVina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adasme, M.F.; Linnemann, K.L.; Bolz, S.N.; Kaiser, F.; Salentin, S.; Haupt, V.; Schroeder, M. PLIP 2021: expanding the scope of the protein-ligand interaction profiler to DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49(W1), W530–W534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzenthaler, P.; Mata-Gilsinger, M. , Use of in vitro gene fusions to study the uxuR regulatory gene in Escherichia coli K-12: direction of transcription and regulation of its expression. J Bacteriol 1982, 150, 1040–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionov, D.A.; Mironov, A.A.; Rakhmaninova, A.B.; Gelfand, M.S. Transcriptional regulation of transport and utilization systems for hexuronides, hexuronates and hexonates in gamma purple bacteria. Mol Microbiol 2000, 38, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purtov, Y.A.; Tishchenko, S.V.; Nikulin, A.D. Modeling the Interaction of the UxuR-ExuR Heterodimer with the Components of the Metabolic Pathway of Escherichia coli for Hexuronate Utilization. Biophysics 2021, 66, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, B.C.; Kaczmarek, J.A.; Figueiredo, P.R.; Prather, K.L.J.; Carvalho, A.T.P. Transcription factor allosteric regulation through substrate coordination to zinc. NAR Genom Bioinform 2021, 3, lqab033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessonova, T.A.; Fando, M.S.; Kostareva, O.S.; Tutukina, M.N.; Ozoline, O.N.; Gelfand, M.S.; Nikulin, A.D.; Tishchenko, S.V. Differential Impact of Hexuronate Regulators ExuR and UxuR on the Escherichia coli Proteome. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 8379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purtov, Y.A.; Tutukina, M.N.; Nikulin, A.D.; Ozoline, O.N. The topology of the contacts of potential ligands for the UxuR transcription factor of Escherichia coli as revealed by flexible molecular docking. Biophysics 2019, 64, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; Lepore, R.; Schwede, T. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46(W1), W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guex, N.; Peitsch, M.C.; Schwede, T. Automated comparative protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL and Swiss-PdbViewer: A historical perspective. Electrophoresis 2009, 30, S162–S173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienert, S.; Waterhouse, A.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Tauriello, G.; Studer, G.; Bordoli, L.; Schwede, T. The SWISS-MODEL Repository - new features and functionality. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, D313–D319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Research, 2025; 53(D1), D609–D617.

- Purtov, Y.A.; Ozoline, O.N. Neuromodulators as Interdomain Signaling Molecules Capable of Occupying Effector Binding Sites in Bacterial Transcription Factors. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 15863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, I.S.; Mota, L.J.; Soares, C.M.; de Sá-Nogueira, I. Functional domains of the Bacillus subtilis transcription factor AraR and identification of amino acids important for nucleoprotein complex assembly and effector binding. J Bacteriol 2006, 188, 3024–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needleman, S.B.; Wunsch, C.D. (1970). A General Method Applicable to the Search for Similarities in the Amino Acid Sequence of Two Proteins. Journal of Molecular Biology 1970, 48, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertram, R.; Rigali, S.; Wood, N.; Lulko, A.T.; Kuipers, O.P.; Titgemeyer, F. Regulon of the N-acetylglucosamine utilization regulator NagR in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 2011, 193, 3525–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fillenberg, S.B.; Grau, F.C.; Seidel, G.; Muller, Y.A. Structural insight into operator dre-sites recognition and effector binding in the GntR/HutC transcription regulator NagR. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, 1283–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampaio, M.M.; Chevance, F.; Dippel, R.; Eppler, T.; Schlegel, A.; Boos, W.; Lu, Y.J.; Rock, C.O. Phosphotransferase-mediated transport of the osmolyte 2-O-alpha-mannosyl-D-glycerate in Escherichia coli occurs by the product of the mngA (hrsA) gene and is regulated by the mngR (farR) gene product acting as repressor. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 5537–5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiapei, M.; Chong, S. Roles of intrinsically disordered protein regions in transcriptional regulation and genome organization. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 2025, 90, 102285. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Perumal, N.B.; Oldfield. CJ.; Su, E.W.; Uversky, V.N.; Dunker, A.K. Intrinsic disorder in transcription factors. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 6873–6888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadži, S.; Živič, Z.; Kovačič, M.; Zavrtanik, U.; Haesaerts, S.; Charlier, D.; Plavec, J.; Volkov, A.N.; Lah, J.; Loris, R. Fuzzy recognition by the prokaryotic transcription factor HigA2 from Vibrio cholerae. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Kotelnikov. S.; Egbert, M.E.; Ofaim, S.; Stevens, G.C.; Phanse, S.; Saccon, T.; Ignatov, M.; Dutta, S.; Istace, Z.; Moutaoufik, M.T.; Aoki, H.; Kewalramani, N.; Sun, J.; Gong, Y.; Padhorny, D.; Poda, G.; Alekseenko, A.; Porter, K.A.; Jones, G.; Rodionova, I.; Guo, H.; Pogoutse, O.; Datta, S.; Saier, M.; Crovella, M.; Vajda, S.; Moreno-Hagelsieb, G.; Parkinson, J.; Segre, D.; Babu, M,; Kozakov, D.; Emili, A. Ligand interaction landscape of transcription factors and essential enzymes in E. coli. Cell 2025, 188, 1441–1455.e15. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51(D1), D1373–D1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanwell, M. D.; Curtis, D. E.; Lonie, D. C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G. R. Avogadro: anadvanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J Cheminform 2012, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blattner, F.R.; Plunkett, G. 3rd.; Bloch, C.A.; Perna, N.T.; Burland, V.; Riley, M.; Collado-Vides, J.; Glasner, J.D.; Rode, C.K.; Mayhew, G.F.; Gregor, J.; Davis, N.W.; Kirkpatrick, H.A.; Goeden, M.A.; Rose, D.J.; Mau, B.; Shao, Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 1997, 277, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Matsuura, Y.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53, D672–D677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borriss, R.; Danchin, A.; Harwood, C.R.; Médigue, C.; Rocha, E.P.C.; Sekowska, A.; Vallenet, D. Bacillus subtilis, the model Gram-positive bacterium: 20 years of annotation refinement. Microb Biotechnol 2018, 11, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Li, X.; He, P.; Ho, H.; Wu, Y.; He, Y. Whole-genome sequencing of Bacillus subtilis XF-1 reveals mechanisms for biological control and multiple beneficial properties in plants. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2015, 42, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Cooper, D.R.; Grossoehme, N.E.; Yu, M.; Hung, L.W.; Cieslik, M.; Derewenda, U.; Lesley, S.A.; Wilson, I.A.; Giedroc, D.P.; Derewenda, Z.S. Structure of Thermotoga maritima TM0439: implications for the mechanism of bacterial GntR transcription regulators with Zn2+-binding FCD domains. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2009, 65, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrichs, M.S.; Eastman, P.; Vaidyanathan, V.; Houston, M.; LeGrand, S. Beberg, A.L.; Ensign, D.L.; Bruns, C.M.; Pande V.S. Accelerating Molecular Dynamic Simulation on Graphics Processing Units. J. Comp Chem 2009, 30, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A. J. AutoDockVina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M. F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D. S.; Olson, A. J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).