1. Introduction

The modification of solid dosage forms has attracted increasing attention in the pharmaceutical industry as a strategy to enhance the solubility of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [

1]. Various solid-state forms, including salts, solvates, low-melting mixtures, co-crystals, and amorphous forms, have been explored [

2,

3]. Due to their higher solubility, amorphous forms have emerged as an effective approach to address the poor solubility of many APIs [

4]. However, the intrinsic physical instability of amorphous forms during manufacturing and storage often leads to recrystallization, which significantly restricts their commercial application [

5]. Notably, co-amorphous (CAM) systems can overcome these limitations by improving the physicochemical properties and stability of APIs [

6]. A co-amorphous system is defined as a single-phase amorphous material characterized by a single glass transition temperature (T

g), formed by combining APIs with small molecules such as other drugs or excipients. The physical stability of these systems is primarily enhanced by intermolecular interactions, particularly hydrogen bonding, between the API and the co-former [

7,

8]. Of special interest are drug-drug co-amorphous systems, which can simultaneously improve the efficacy of one API while reducing the toxicity or side effects of another [

9,

10].

Curcumin (CUR), a phytochemical with a favorable safety profile and minimal side effects, has been extensively studied. It possesses a broad spectrum of biological activities, including anti-oxidant, anti-cancer, anti-bacterial, anti-viral and neuroprotective effects [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Nevertheless, its clinical application has been limited by its extremely low solubility and poor bioavailability [

13,

14]. To achieve adequate oral absorption, high doses of CUR are often required, which may cause gastrointestinal side effects such as diarrhea, headache, rash, and yellow stool [

15]. Several co-amorphous forms of CUR have been reported, such as CUR-piperine [

16,

17], CUR-myricetin [

18], CUR-L-arginine [

19], and CUR-acetyl salicylic acid[

20], all of which demonstrated superior dissolution rates compared with pure CUR. Co-amorphization can also improve the stability of CUR and the co-former [

16], achieve the simultaneous release of both components [

16], enhance the bioavailability of CUR [

17,

18,

19], and produce synergistic pharmacological effects such as anti-inflammatory [

19,

20] and anti-cancer [

21] activities. The phenolic hydroxyl, enolic C-OH, and methoxyl groups of curcumin are generally regarded as key functional sites that can act as hydrogen bond donors or acceptors during interactions with coformers [

16,

19,

22].

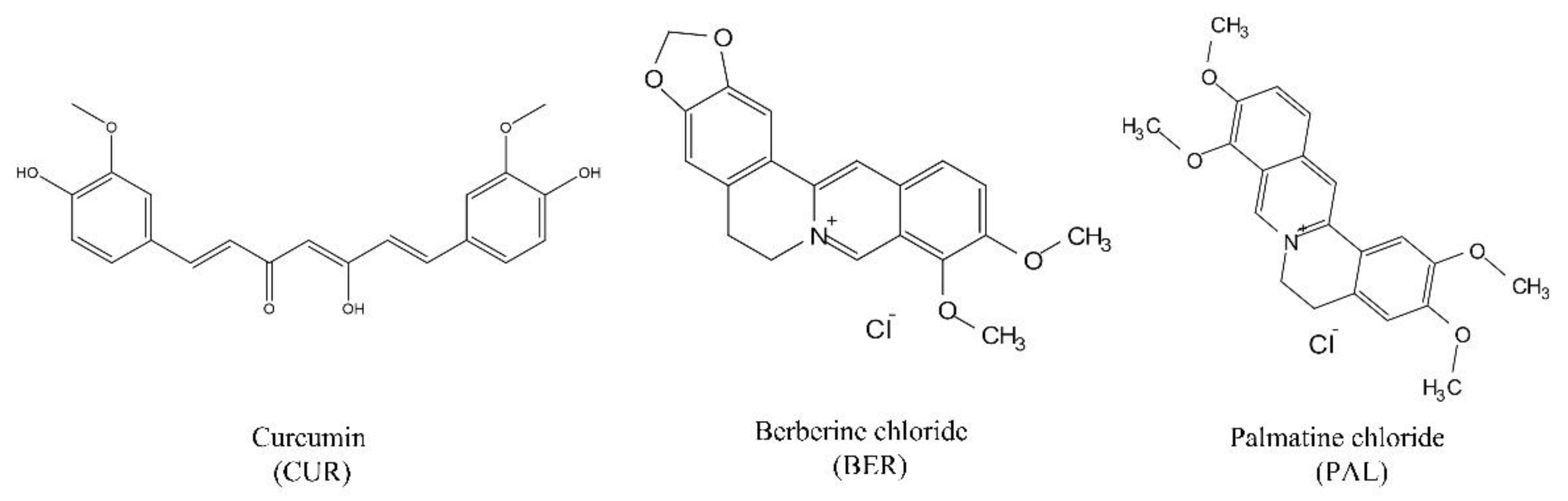

Berberine chloride (BER), an isoquinoline alkaloid derived from

Rhizoma Coptidis, has long been used in traditional Chinese medicine. It exhibits diverse pharmacological activities, including anti-bacterial, hypolipidemic, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, hypolipidemic, and anti-obesity effects [

23,

24]. Palmatine chloride (PAL), a structurally related natural isoquinoline alkaloid, also possesses anti-bacterial, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer properties [

25,

26]. The structural similarity of BER and PAL lies in their rigid skeletons and multiple oxygen atoms, which serve as strong hydrogen bond acceptors. These oxygen atoms can engage in hydrogen bonding with functional groups such as carboxyl, sulfonyl and hydroxyl groups [

27,

28,

29]. Therefore, the use of oxygen-containing alkaloids such as BER and PAL as co-formers with CUR provides a promising strategy for the design of CUR-based drug-drug co-amorphous systems. The molecular structures of CUR, BER and PAL are shown in

Figure 1.

In this work, CUR-BER and CUR-PAL CAM systems were successfully developed and characterized. The combination of these natural drugs enhanced the physicochemical properties of CUR and produced synergistic therapeutic effects. Systematic analyses were conducted using PXRD, DSC and ssNMR. Both CAM systems demonstrated higher stability, significantly improved solubility, and enhanced dissolution performance compared with amorphous CUR. Furthermore, in vitro assays confirmed their synergistic antioxidant and antitumor activities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Curcumin (CUR, purity ≥ 98%), berberine hydrochloride dihydrate (BER·2H2O, purity ≥ 97%), and palmatine hydrochloride trihydrate (PAL·3H2O, purity ≥ 97%) were purchased from Dalian Meilun Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Methanol (purity ≥ 99.7%) was obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. All chemicals were used without further purification.

2.2. Preparation of Amorphous and Co-Amorphous Samples

Amorphous CUR was prepared by solvent evaporation under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator. Specifically, 100 mg of CUR was dissolved in 20 mL of methanol, and the solvent was subsequently removed using a rotary vacuum evaporator at 55 °C. Co-amorphous samples were prepared in a similar manner. CUR and BER (or PAL) were mixed at a 1:1 molar ratio (0.3 mmol each) and dissolved in 30 mL of methanol. The solvent was removed using a rotary vacuum evaporator at 55 °C. All obtained samples were further dried under vacuum at 60 °C for 12 h to remove residual solvents and then stored in a vacuum desiccator at room temperature until further use. The two co-amorphous samples were designated as CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM, respectively.

2.3. Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD)

PXRD patterns of all solid samples were recorded on a SmartLab X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan) using Cu Kα radiation at 40 kV and 40 mA. Data were collected in reflection mode over a 2θ range of 3–50° at a scanning speed of 20°/min with a step size of 0.02°.

2.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC measurements were performed on a DSC214 instrument (Netzsch, Germany). Approximately 5 mg of each sample was sealed in an aluminum pan with a pinhole lid and heated from 30 to 300 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen purge (20 mL/min).

2.5. Solid-State 13C NMR Spectroscopy (ssNMR)

Solid-state 13C NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker AVANCE III spectrometer (Bruker, Germany) operating at 400 MHz. Cross-polarization (CP) techniques, high-power TPPM decoupling, and magic angle spinning (MAS) were employed to enhance sensitivity. Sample was packed into a 4 mm rotor and spun at 10 kHz. The KBr method was used to calibrate the magic angle. The 1H-13C cross-polarization magic-angle spinning (CP/MAS) experiment (νrot = 10 kHz), performed with high-power 1H decoupling, was conducted under the condition ω1H/2π = γHH1H/2π = 60 kHz. The recycle delay was set at 6.5 s. Data were acquired with an H/X dual resonance solid-state probe in TOSS mode at a resonance frequency of 100.625 MHz. Each spectrum was obtained from 480 scans, providing adequate signal-to-noise ratios. All experiments were conducted at room temperature.

2.6. In Vitro Dissolution Test

The release behavior was evaluated using an RC806ADK dissolution tester (Tianjin Tianda Tianfa, China) in a water bath maintained at 37 °C, with a stirring speed of 100 rpm (Chinese Pharmacopoeia paddle method). To ensure uniformity, samples were sieved through a 100-mesh screen (mesh size 0.15 mm). An amount equivalent to 50 mg CUR was dispersed in 250 mL deionized water containing 0.5% Tween-80. At predetermined intervals, 2 mL of suspension was withdrawn, filtered through a 0.45 μm nylon membrane, and analyzed by HPLC. Each test was performed in triplicate.

2.7. Equilibrium Solubility

Equilibrium solubility was determined using the shake-flask method. The dissolution media included deionized water (with 0.5% Tween-80), 0.1 M hydrochloric acid (pH 1.2), 0.05 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 6.8, with 0.5% Tween-80), and 0.05 M sodium acetate-acetic acid buffer (pH 4.0, with 0.5% Tween-80). These media were selected to simulate different physiological environments and to assess the pH-dependent dissolution characteristics of the formulations. A total of 100 mg of each sample was added to 2 mL of dissolution medium. Suspensions were sonicated for 10 min and then shaken at 37 °C for 48 h to reach equilibrium. The samples were centrifuged, and the supernatants were filtered through 0.45 μm nylon membranes. After appropriate dilution, CUR, BER, and PAL concentrations were measured by HPLC. All tests were performed in triplicate.

2.8. High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

Concentrations of CUR, BER, and PAL were quantified using a Shimadzu LC-20AD HPLC system equipped with a Shim-pack GIST C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm, 5 μm). The mobile phase consisted of methanol (A) and 0.2% aqueous phosphoric acid solution (B) in a 70:30 ratio, delivered at 1.0 mL/min. The column oven was maintained at 30 °C, and the injection volume was 5 μL. Detection wavelengths were set at 430 nm for CUR and 415 nm for BER or PAL.

2.9. Physical Stability

To evaluate physical stability, amorphous CUR, CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM samples were stored under stress conditions. Samples were placed in a SHH-100GD-2 photostability chamber (Chongqing Yongsheng, China) at 4500 Lx light intensity, or in a LHH-150SD stability test chamber (Shanghai Yiheng, China) at 60 °C or 40 °C/75% RH. PXRD was performed at predetermined intervals to monitor recrystallization.

2.10. DPPH Radical-Scavenging Activity

The DPPH assay was performed following a published method [

30]. A 6 × 10

-5 M DPPH solution was prepared in ethanol, and subsequently, 100 μL of this solution was mixed with 100 μL of sample solution at varying concentrations in a 96-well microtiter plate. After incubation in the dark at room temperature for 30 min, the absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a Spark microplate reader (Tecan, Switzerland). Radical scavenging activity was calculated as: Inhibition rate (%) = [(A

B − A

S)/A

B] × 100%, where A

B and A

S denote the absorbance values of the blank and sample, respectively. All measurements were conducted in triplicate, and results were expressed as mean ± SD.

2.11. ABTS+ Radical-Scavenging Activity

ABTS

+ radical scavenging was assessed using a literature method [

30]. ABTS

+ solution was generated by reacting 7 mM ABTS with 2.54 mM potassium persulfate, incubated in the dark for 16 h at room temperature. The working solution was diluted with ethanol to an absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. Test samples (100 μL) were mixed with ABTS

+ solution (100 μL) in a 96-well microtiter plate. After 5 min, absorbance was measured at 734 nm, and radical scavenging activity was calculated using the same formula as in the DPPH assay. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.12. Antitumor Activity

The antitumor activity was evaluated using the MTT assay in HT-29 cells. Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 4.0 × 103 cells/well and incubated overnight. The cells were then treated with varying concentrations of samples for 24, 48, or 72 h. After treatment, 20 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL, solution in PBS) was added to each well, and plates were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. After removing the supernatant, 200 μL of DMSO was added to each well, and the plates were shaken gently for 10 min. The optical density (OD) of each well was measured by a microplate reader at 570 nm. The inhibition rate (IR) was calculated as: Inhibition rate (%) = (1 − ODtreatment/ODcontrol) × 100%. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

The results of radical-scavenging and antitumor assays are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA with Origin 2018 software. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05 (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Solid-State Characterization by PXRD and DSC

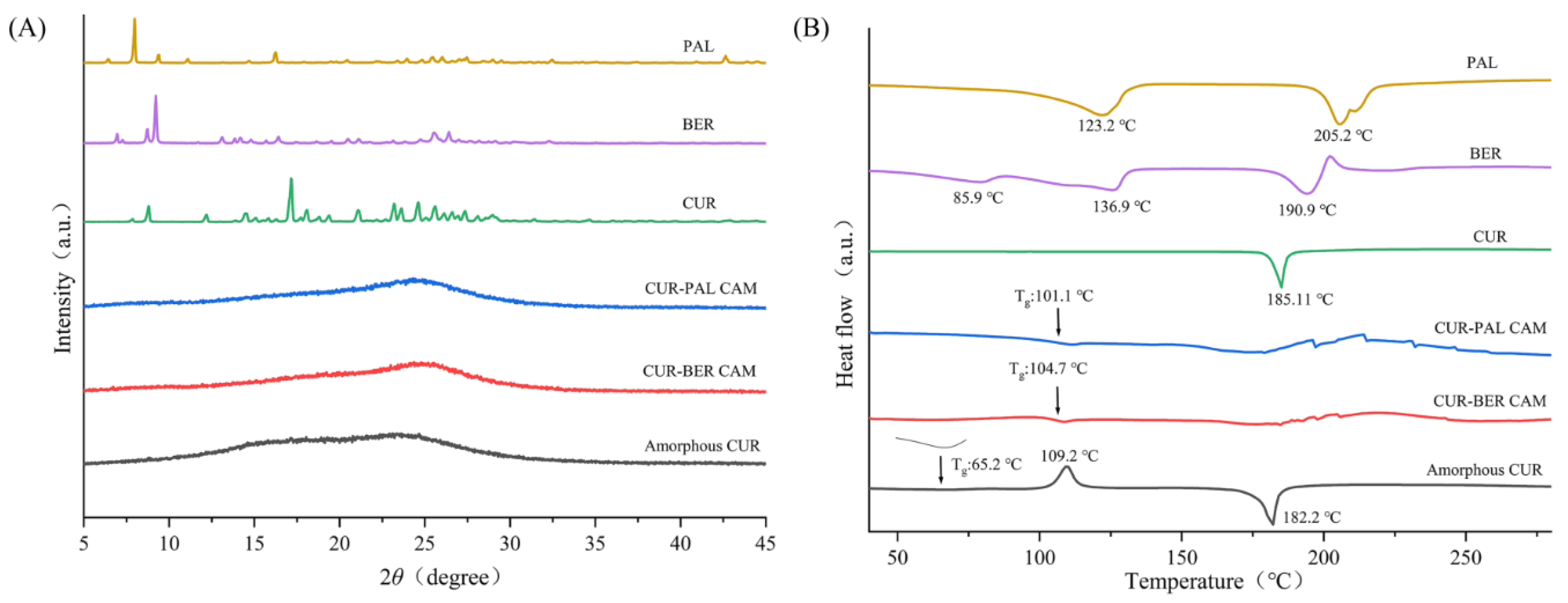

As shown in

Figure 2A, the PXRD pattern of raw materials (CUR, BER and PAL) displayed sharp diffraction peaks characteristic of a highly ordered crystalline lattice. In contrast, CUR obtained by rotary evaporation (amorphous CUR) exhibited broad and diffuse halos without distinct reflections, indicating an amorphous state. Similarly, both CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM showed no crystalline diffraction peaks, confirming the absence of long-range order and suggesting successful amorphization of the samples.

DSC analysis was further employed to confirm the amorphous nature of the samples. As shown in

Figure 2B, the DSC thermogram of amorphous CUR differed markedly from that of crystalline CUR. Crystalline CUR exhibited a single endothermic melting peak at 185.1 °C. In contrast, amorphous CUR displayed a glass transition temperature (T

g) at 65.2 °C. This was followed by an exothermic recrystallization peak at 109.2 °C and an endothermic melting peak at 182.2 °C, reflecting the inherent thermodynamic tendency of amorphous CUR to recrystallize. By contrast, the DSC thermograms of CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM did not showed the characteristic recrystallization peak observed in amorphous CUR. Instead, both samples exhibited only a broad endothermic event in the range of 150-200 °C, further supporting their amorphous character and indicating that recrystallization was effectively suppressed.

More importantly, CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM each exhibited a single T

g, measured at 104.7 °C and 101.1 °C, respectively. The presence of a single T

g strongly indicates homogeneous single-phase amorphous systems, i.e., co-amorphous forms [

31]. The markedly higher T

g values compared with amorphous CUR suggest enhanced molecular-level stabilization and improved thermal stability. This effect is most likely attributable to intermolecular interactions, such as probable hydrogen bonding between CUR and BER/PAL, which reduce molecular mobility and hinder rearrangement into a crystalline lattice. Such stabilization is consistent with the superior thermal stability of CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM observed in subsequent physical stability studies. Together, the PXRD and DSC data provide compelling evidence that CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM form stable co-amorphous systems.

3.2. Solid-State 13C NMR Spectroscopy (ssNMR)

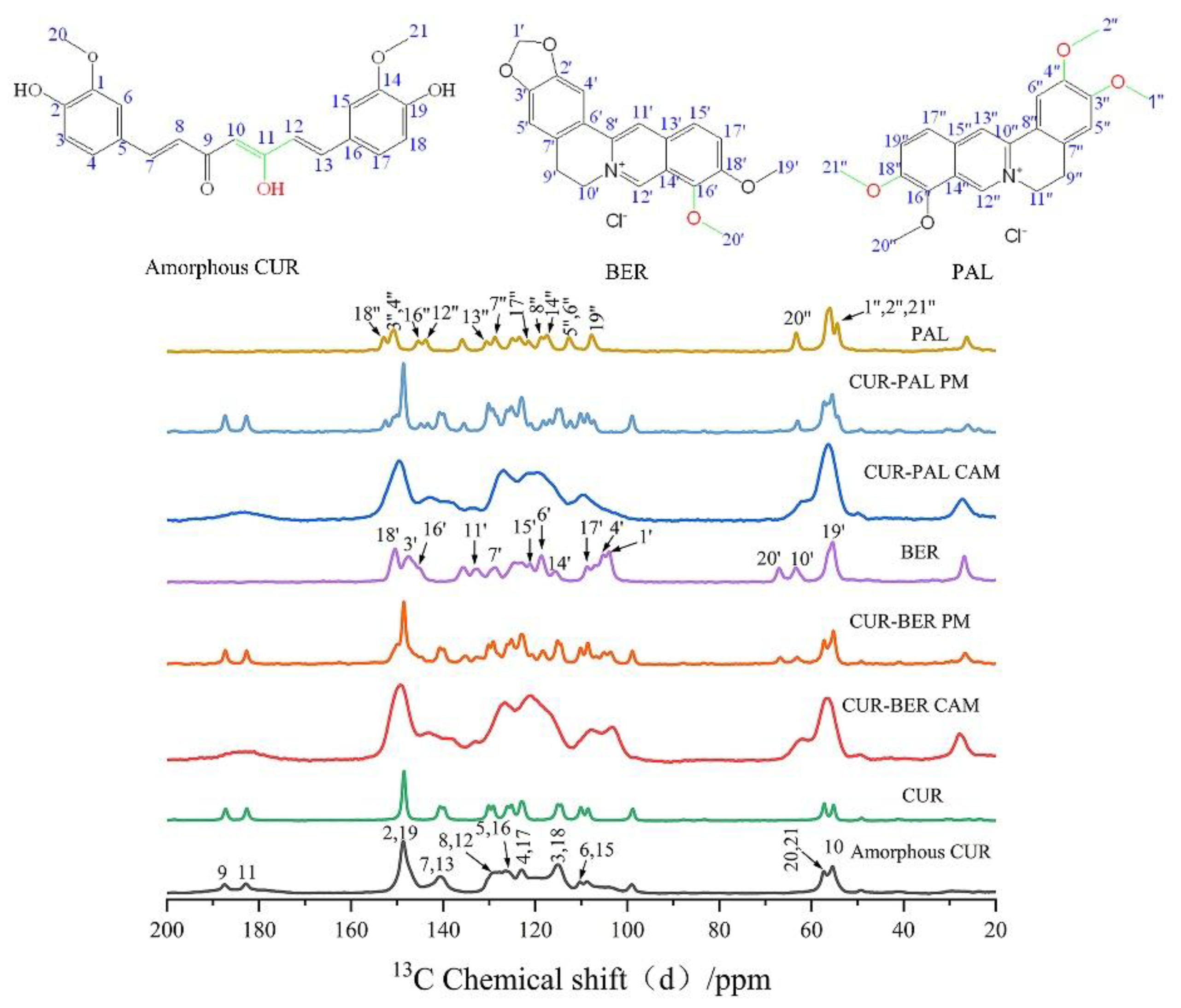

To elucidate the intermolecular interactions, particularly hydrogen bonding, between CUR and BER/PAL in the co-amorphous systems, the

13C ssNMR spectra of BER, PAL, CUR, amorphous CUR, CUR-BER CAM, CUR-PAL CAM, and the physical mixtures of BER/PAL with CUR (PMs) were recorded (

Figure 3). It is well established that curcumin exists in the keto-enol tautomeric form in the solid state [

14,

32]. For CUR or amorphous CUR, the signals at 183.5 and 187.5 ppm correspond to the carbon atoms C11 (enolic C-OH) and C9 (C=O group), respectively. For BER, the chemical shifts at 145.27 and 150.46 ppm are attributed to C16′ and C18′ attached to methoxy groups, while the peaks at 55.4 and 66.9 ppm correspond to the methyl carbons C19′ and C20′ in the methoxy groups. Similarly, for PAL, the chemical shifts at 145.42, 150.68, and 153.16 ppm correspond to C16′′, C3′′/C4′′, and C18′′, all associated with methoxy substituents. The peaks at 54.1 and 63.5 ppm are assigned to the methyl carbons C1′′/C2′′/C21′′and C20′′ in the methoxy groups.

Compared with the spectra of individual components (BER, PAL, and CUR), the CUR-BER and CUR-PAL co-amorphous systems exhibited distinct changes, including chemical shift variations, peak broadening, and disappearance of certain resonances. In contrast, the PMs showed no notable changes relative to the pure APIs, suggesting that such interactions only occur in the co-amorphous state.

In the

13C ssNMR spectra of CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM, marked chemical shifts were observed for the CUR carbon atoms C9 and C11, with the corresponding peaks merging into a broader resonance. This feature indicates an alteration in the conjugation between the keto and enol groups of curcumin, consistent with previously reported CUR-L-arginine and CUR-piperazine co-amorphous system [

19,

33]. Moreover, significant chemical shift changes and peak broadening were observed for carbons in close proximity to the enolic C-OH (C10, C8, C12, C7, and C13), suggesting that the enol hydroxyl of CUR likely participates in hydrogen bonding with BER or PAL molecules.

For BER in the CUR-BER CAM, prominent chemical shift changes were detected for C16′ and C20′ (methoxy groups), as well as neighboring carbons C14′, C17′, C18′, and C19′. Similarly, in the CUR-PAL CAM, shifts were evident for C1′′/C2′′/C21′′, C18′′ and C3′′/C4′′, implying that at least one of the three methoxy groups in PAL is involved in molecular interactions with CUR.

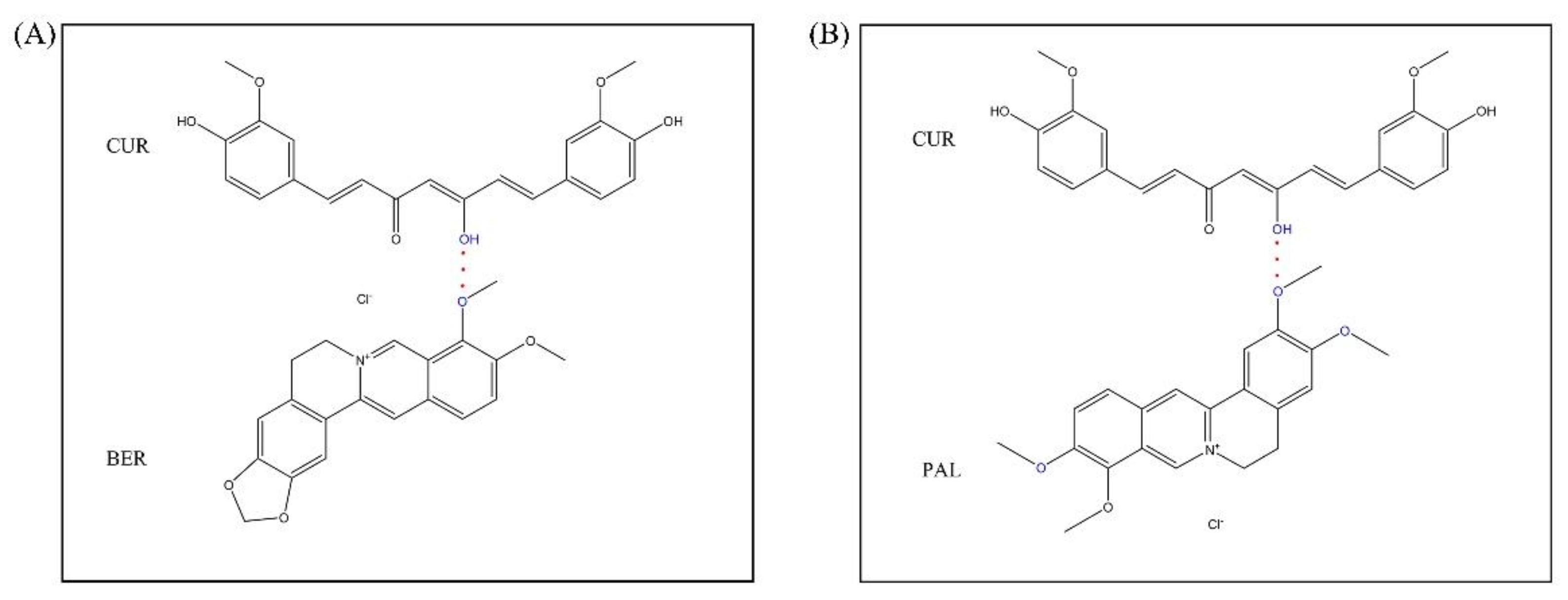

Taken together, these results indicate that strong intermolecular hydrogen bonding interactions probably occur between the enolic hydroxyl group of CUR and the oxygen atoms of the methoxy groups in BER or PAL within the co-amorphous systems. The possible hydrogen-bonding interactions are schematically illustrated in

Figure 4.

3.3. In Vitro Dissolution Study

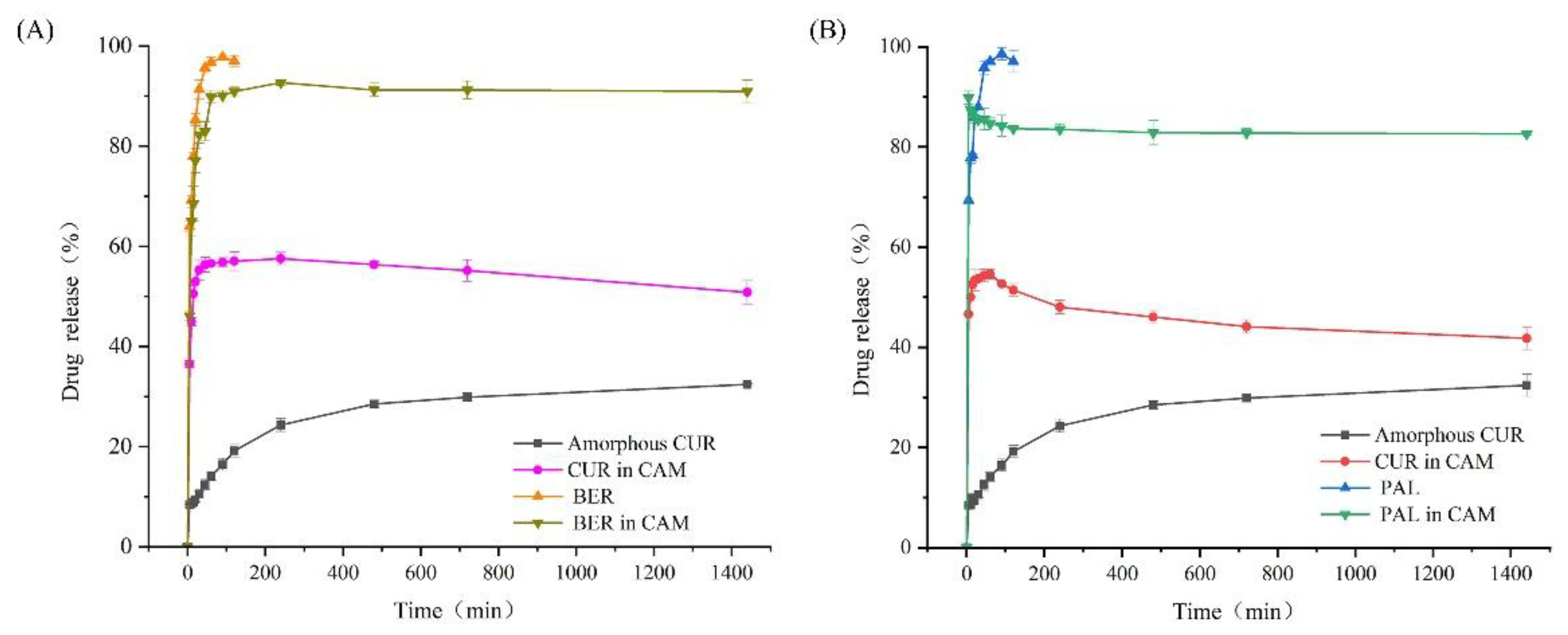

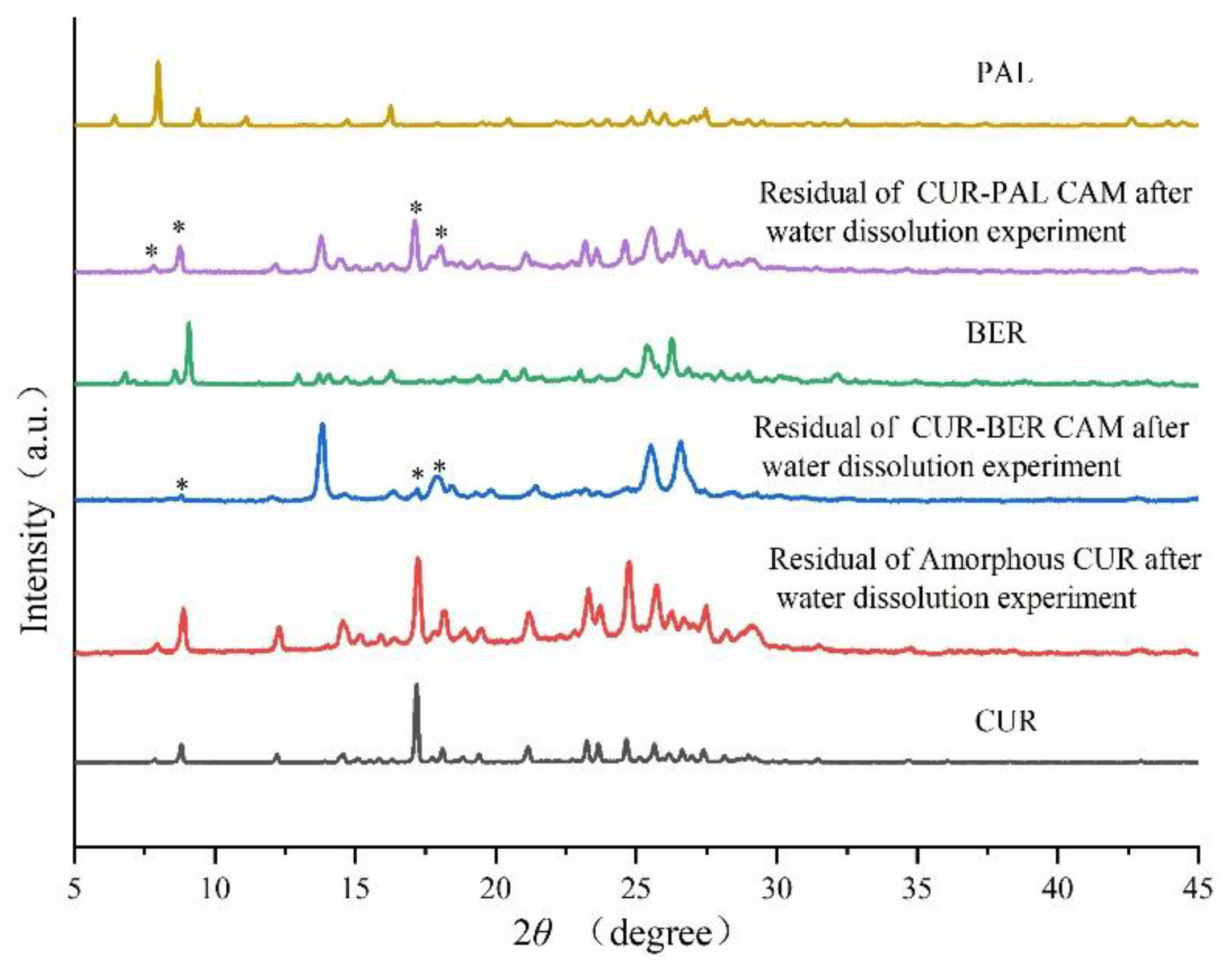

The dissolution behavior of BER, PAL, amorphous CUR and the two co-amorphous systems was investigated to evaluate the impact of co-amorphization on drug release performance. As shown in

Figure 5, both BER and PAL displayed rapid dissolution, reaching complete release within 90 minutes. In contrast, their release from the co-amorphous systems was incomplete throughout the entire dissolution period. Amorphous CUR exhibited a comparatively slow dissolution rate, with only 32.4% of the drug dissolved after 24 hours. Notably, CUR in both co-amorphous systems showed substantially enhanced dissolution behavior. For the CUR-BER CAM, CUR dissolution reached a maximum of 57.3% at 120 minutes, whereas for the CUR-PAL CAM, a maximum dissolution of 54.6% was achieved within 60 minutes. After reaching the peak values, the dissolution of CUR in both co-amorphous systems gradually decreased, showing a characteristic “spring and parachute” profile typical of amorphous formulations [

34]. PXRD analysis of the residual solids after dissolution (

Figure 6) confirmed that the release process was accompanied by the recrystallization of CUR. These findings clearly indicate that the formation of co-amorphous systems between CUR and BER/PAL significantly enhanced both the dissolution rate and the overall extent of CUR release, suggesting potential bioavailability compared with the pure amorphous CUR.

3.4. Equilibrium Solubility Study

The equilibrium solubility of amorphous CUR, CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM was determined in different media containing 0.5% Tween-80, and the results are summarized in

Table 1. Amorphous CUR exhibited distinct pH-dependent solubility, increasing from 10.42 ± 1.88 μg/mL at pH 1.2 to 52.65 ± 3.46 μg/mL at pH 6.8. This pH-dependent behavior is consistent with the weakly acidic nature of CUR.

Co-amorphization of CUR with BER or PAL significantly enhanced the solubility of CUR in all tested media, with the CUR-PAL system showing a more pronounced improvement. In pure water, the solubility of CUR in the CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM systems reached 107.2 ± 3.88 μg/mL and 712.82 ± 3.70 μg/mL, respectively, corresponding to approximately 2.3-fold and 15.1-fold improvements relative to amorphous CUR. Similar enhancement trends were observed at other pH values. For example, at pH 1.2, the solubility of CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM was 3.5- and 10.3-fold higher than that of amorphous CUR, while at pH 6.8, the respective increases were 2.3- and 11.7-fold.

Despite the substantial solubility improvement, both co-amorphous systems maintained a pH-dependent solubility pattern similar to that of amorphous CUR, suggesting that co-amorphization enhances overall solubility without altering the intrinsic pH sensitivity of CUR.

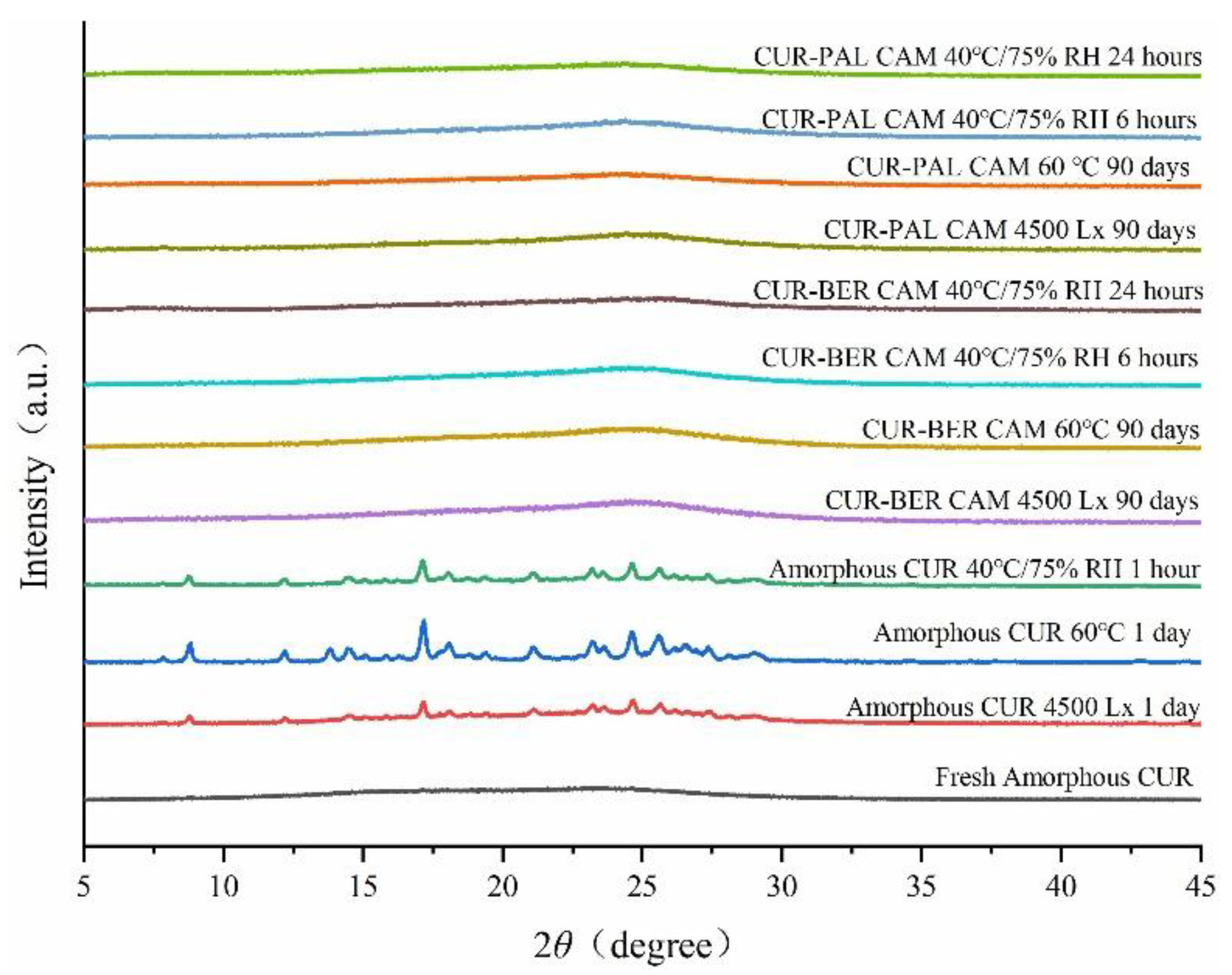

3.5. Physical Stability Analysis

The physical stability of amorphous CUR, CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM was evaluated in accordance with the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2020 Edition) under three stress conditions: 60 °C, light exposure at an intensity of 4500 Lx, and 40 °C/75% relative humidity (RH). Structural evolution during storage was monitored by PXRD, and the corresponding diffraction patterns are presented in

Figure 7. Amorphous CUR rapidly recrystallized, showing almost complete conversion to the crystalline form after only one day under both 60 °C and 4500 Lx conditions. In contrast, the PXRD patterns of the two co-amorphous systems retained the characteristic broad and diffuse halos without distinct reflections throughout the 90 days stability study under the same conditions, suggesting the absence or a markedly slower rate of crystallization. At 40 °C/75% RH, amorphous CUR recrystallized within one hour, whereas both co-amorphous systems exhibited no detectable crystallization within 24 hours. These results clearly demonstrate that humidity exerts a pronounced influence on the physical stability of amorphous forms. Furthermore, strong intermolecular interactions between CUR and BER, as well as between CUR and PAL, increase the energy barriers for molecular rearrangement, thereby delaying the recrystallization of the co-amorphous systems.

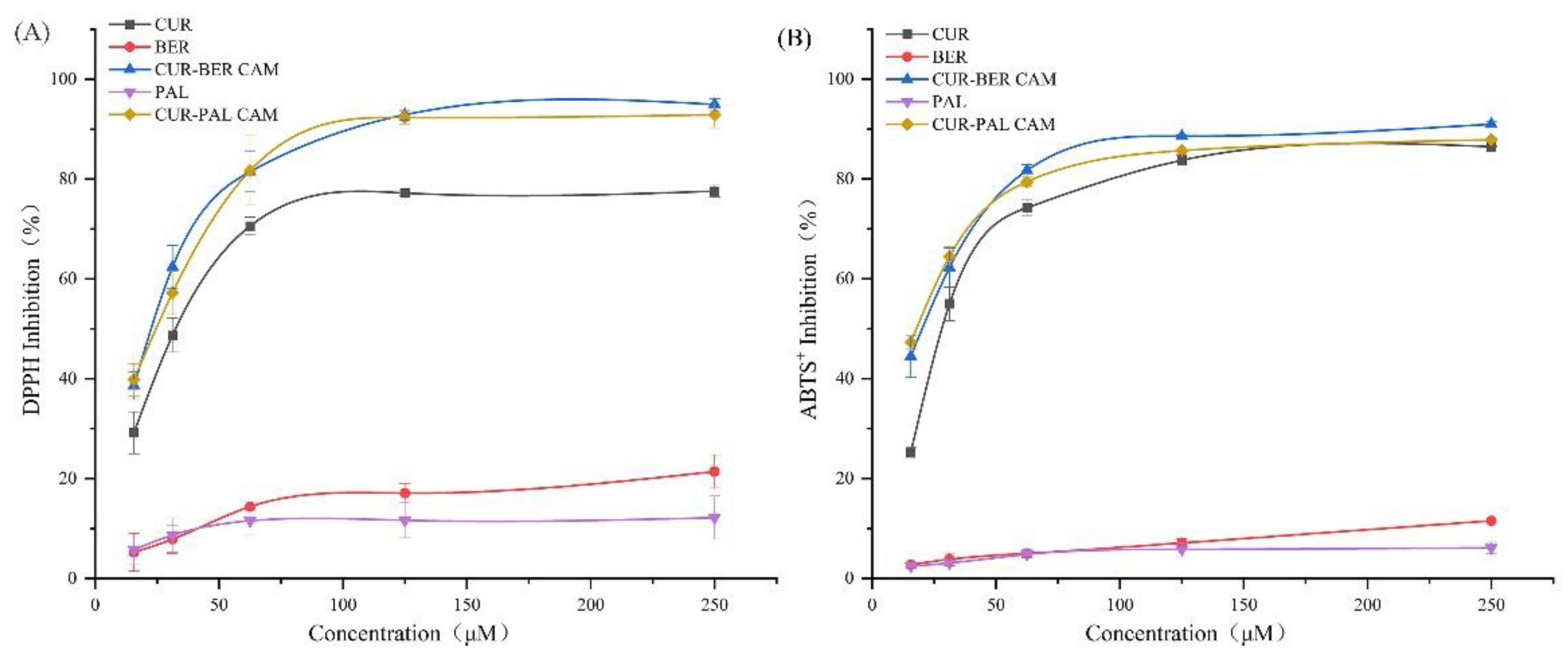

3.6. Antioxidant Assay

The antioxidant activities of CUR, BER, PAL, and the two co-amorphous systems were assessed using DPPH free radical-scavenging and ABTS

+ radical-scavenging assays. The DPPH radical employed in this study is a stable, neutral radical at ambient temperature. In ethanol solution, DPPH exhibits an intense purple color that gradually fades upon reduction by antioxidants [

35]. The ABTS radical, in contrast, is a cationic substrate that forms blue-green ABTS

+ radicals characterized by a distinct absorption maximum at 734 nm. The presence of antioxidants inhibits the generation of ABTS

+, resulting in a decrease in absorbance [

36].

As illustrated in

Figure 8A, both CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM exhibited stronger DPPH radical-scavenging activity than their individual components across the tested concentration range (15.6-250 μM). Moreover, both CAMs displayed a pronounced synergistic effect at lower concentrations. A similar trend was observed in the ABTS

+ radical-scavenging assay (

Figure 8B), where both co-amorphous systems showed enhanced antioxidant performance compared to the pure APIs. Collectively, these findings indicate that the two CAMs possess superior antioxidant capacity, with evident synergistic behavior at low concentrations. This synergism highlights the promising potential of the CAMs as effective antioxidant agents for mitigating free radical-induced oxidative stress in biological systems.

3.7. Anti-Cancer Activity

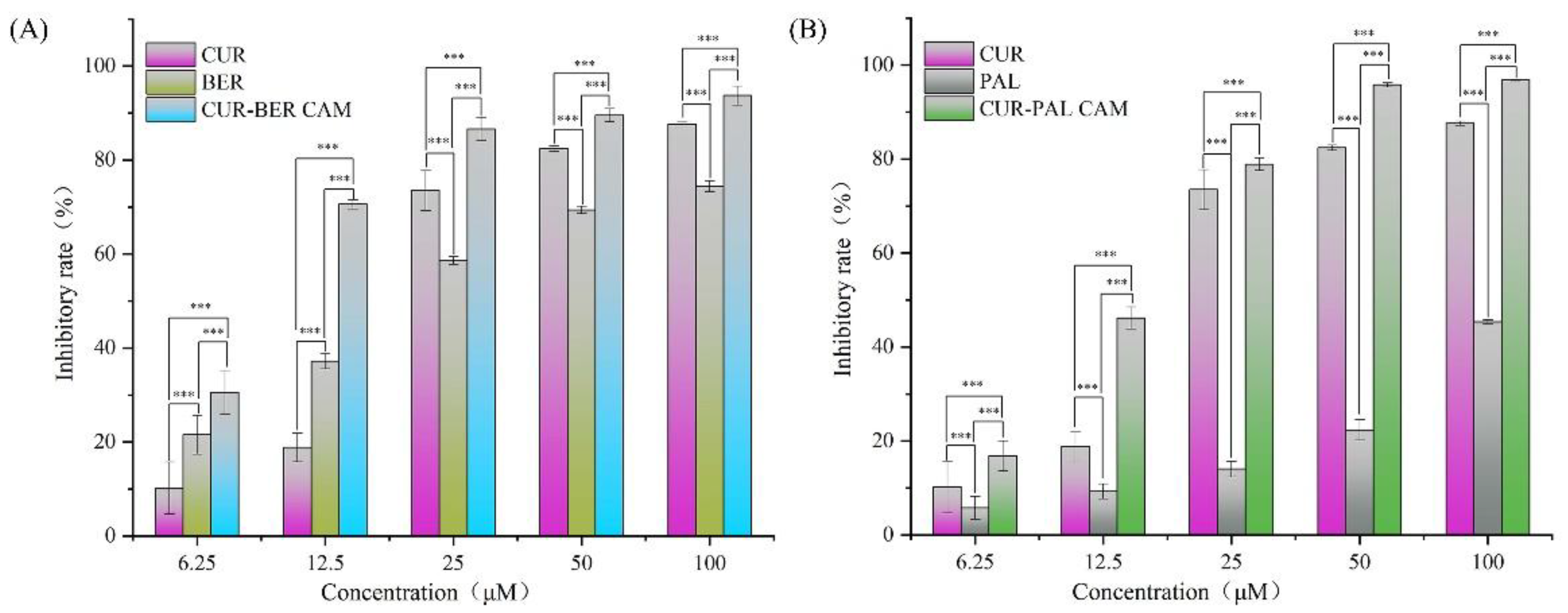

The anti-cancer activities of all samples were evaluated using a cell proliferation assay on the human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line HT-29. As shown in

Figure 9, the inhibitory effects of CUR, BER, PAL, CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM on HT-29 cells increased progressively with rising drug concentrations. In addition, Both CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM exhibited higher inhibitory effects than their respective single components across the concentration range of 6.25-100 μM. Notably, at a concentration of 12.5 μM, the inhibitory rates of CUR-BER CAM and CUR-PAL CAM exceeded the sum of those of the individual components, indicating a definite synergistic interaction between the two compounds at this drug concentration. Furthermore, the IC

50 value of CUR against HT-29 cells was 18.2 μM, whereas those of BER and PAL were 20.0 μM and 142.4 μM, respectively. Remarkably, the IC

50 values of CUR-BER and CUR-PAL CAMs decreased substantially to 7.9 μM and 14.9 μM, respectively, confirming their enhanced cytotoxic efficacy relative to the individual components. These findings highlight the synergistic potential of co-amorphization in improving the anti-cancer activity of CUR in combination with isoquinoline alkaloids.

4. Conclusions

In this study, co-amorphous systems of curcumin with berberine hydrochloride (CUR-BER CAM) and palmatine hydrochloride (CUR-PAL CAM) were successfully developed. Solid-state characterizations, including PXRD, DSC, and ssNMR, confirmed the formation of co-amorphous phases, likely stabilized through strong intermolecular hydrogen bonding between the enolic hydroxyl group of CUR and the oxygen atoms of the methoxy groups in BER or PAL. Both CAMs exhibited markedly improved physical stability over amorphous CUR, as evidenced by elevated glass transition temperatures and effective suppression of recrystallization under thermal, humidity, and light stress conditions. Moreover, the CUR-BER and CUR-PAL CAMs showed significantly enhanced solubility and faster dissolution rates compared with amorphous CUR. In addition, both systems displayed superior antioxidant activity and synergistic anticancer effects against HT-29 cells. Overall, this study demonstrates that co-amorphization of curcumin with isoquinoline alkaloids offers a promising strategy to simultaneously enhance physicochemical properties of curcumin and achieve synergistic pharmacological effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and B.L.; methodology, Q.G.; validation, Y.Z. and L.L.; formal analysis, Y.Z. and Q.G.; investigation, Y.Z. and Q.G.; resources, L.L. and R.S.; data curation, Y.Z. and L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z. and Q.G.; writing—review and editing, B.L.; supervision, M.Z.; project administration, B.L.; funding acquisition, Y.Z., L.L. and B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors appreciate for the support from Fujian Provincial Guiding Science and Technology Program Project (2023Y0076), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2023J05245 and 2025J011261).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| APIs |

active pharmaceutical ingredients |

| BER |

berberine chloride |

| CAM |

co-amorphous |

| CP |

cross-polarization |

| CUR |

curcumin |

| DSC |

differential scanning calorimetry |

| HPLC |

high performance liquid chromatography |

| IR |

inhibition rate |

| MAS |

magic angle spinning |

| OD |

optical density |

| PAL |

palmatine chloride |

| PBS |

phosphate-buffered saline |

| PM |

physical mixture |

| PXRD |

powder X-ray diffraction |

| SD |

standard deviation |

| ssNMR |

solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance |

References

- Gui, Y. Solid Form Screenings in Pharmaceutical Development: a Perspective on Current Practices. Pharm. Res. 2023, 40, 2347–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wang, R.; Dong, X.; Chen, P.; Duan, J.; Shi, M.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y. A Survey of Solid Form Landscape: Trends in Occurrence and Distribution of Various Solid Forms and Challenges in Solid Form Selection. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 114, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappa, P.; Jenjeti, R.; Kljun, J.; Mittapalli, S.; Pichler, A.; Desiraju, G. Pharmaceutical Solid Form Screening and Selection: Which Form Emerges? Cryst. Growth Des. 2025, 25, 4783–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, K.; Moseson, D.; Taylor, L. Amorphous Solubility Advantage: Theoretical Considerations, Experimental Methods, and Contemporary Relevance J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 114, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaval, M.; Dudhat, K.; Soniwala, M.; Dudhrejiya, A.; Shah, S.; Prajapati, B. A Review on Stabilization Mechanism of Amorphous Form Based Drug Delivery System. Mater. Today Commn. 2023, 37, 107411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Moinuddin, S.; Cai, T. Advances in Coamorphous Drug Delivery Systems. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2019, 9, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Grohganz, H.; Löbmann, K.; Rades, T.; Hempel, N.-J. Co-Amorphous Drug Formulations in Numbers: Recent Advances in Co-Amorphous Drug Formulations with Focus on Co-Formability, Molar Ratio, Preparation Methods, Physical Stability, In Vitro and In Vivo Performance, and New Formulation Strategies. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Deng, J.; Dai, Q.; Zhang, H. Recent Advances in Coamorphous Systems of Natural Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients: Preparations, Characterizations, and Applications. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 35352–35366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, P.; Ma, R.; Jia, J.; Fu, Q. Drug-Drug Co-Amorphous Systems: An Emerging Formulation Strategy for Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 103883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelke, R.; Velagacherla, V.; Nayak, U. Recent Advances in Dual-Drug Co-Amorphous Systems. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 103863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethiya, A.; Agarwal, D.; Agarwal, S. Current Trends in Drug Delivery System of Curcumin and its Therapeutic Applications. Mini-rev. Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 1190–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Amaroli, A.; Panfoli, I.; Bozzo, M.; Ferrando, S.; Candiani, S.; Ravera, S. The Bright Side of Curcumin: A Narrative Review of Its Therapeutic Potential in Cancer Management. Cancers 2024, 16, 2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Lin, J.; Li, H.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Velkov, T.; Shen, J. The Natural Product Curcumin as an Antibacterial Agent: Current Achievements and Problems. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q. A Perspective on the Chemical Structures and Molecular Mechanisms of Curcumin and its Derivatives and Analogs in Cancer Treatment (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2025, 67, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlings, S.; Kalman, D. Curcumin: A Review of Its Effects on Human Health. Foods 2017, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Tang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y. Insight into Formation, Synchronized Release and Stability of Co-Amorphous Curcumin-Piperine by Integrating Experimental-Modeling Techniques. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 113, 1874–1884. [Google Scholar]

- Han, N.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, P.; Lu, Y.; Du, S.; Wu, K. The Controlled Preparation of a Carrier-Free Nanoparticulate Formulation Composed of Curcumin and Piperine Using High-Gravity Technology. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, H.; Xu, X.; Yan, M.; Yu, Z.; Qian, X.; Liu, X.; Zhu, J. Engineering a Curcumin-Myricetin Co-Amorphous System: Hydrogen Bond-Driven Solubility & Bioavailability Enhancement with 16.7-Fold Oral Exposure Boost. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 114, 107439. [Google Scholar]

- Mancillas-Quiroz, J.; Carrasco-Portugal, M.; Mondragón-Vásquez, K.; Huerta-Cruz, J.; Rodríguez-Silverio, J.; Rodríguez-Vera, L.; Reyes-García, J.; Flores-Murrieta, F.; Domínguez-Chávez, J.; Rocha-González, H. Development of a Novel Co-Amorphous Curcumin and L-arginine (1:2): Structural Characterization, Biological Activity and Pharmacokinetics. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohapatra, T.; Moharana, A.; Swain, R.; Subudhi, B. Coamorphisation of Acetyl Salicylic Acid and Curcumin for Enhancing Dissolution, Anti-inflammatory Effect and Minimizing Gastro Toxicity. J. Drug. Deliv. Sci. Tec. 2021, 61, 102119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, X.; An, J.; Lin, E.; Li, W.; Qin, H.; Zhen, J.; Dai, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, T.; Chen, J. Comparative Investigation on a Eutectic Mixture, Coamorphous Mixture, and Cocrystal of Imatinib and Curcumin: Preparation, Characterization, and Property Evaluation. Cryst. Growth Des. 2025, 25, 5689–5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, H.; Bian, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, S.; Zheng, X.; Du, Z.; Zhang, K.; Ouyang, D. Molecular Interactions for the Curcumin-Polymer Complex with Enhanced Anti-Inflammatory Effects. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Li, L.; Zhao, L.; Yu, P.; Li, D. A Patent Review of Berberine and its Derivatives with Various Pharmacological Activities (2016-2020). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2022, 32, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surampudi, A.; Prasad, S.; Ramanujam, P.; Swain, D.; Wadje, B.; Bharate, S.; Kamalakannan, U.; Kathirvel, M.; Balasubramanian, S. Improving the Oral Bioavailability of Berberine: A Crystal Engineering Approach. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 685, 126177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Han, L.; Yang, H.; Lu, G.; Shi, Z.; Ma, B. From Traditional Remedy to Modern Therapy: a Comprehensive Review of Palmatine’s Multi-Target Mechanisms and Ethnopharmacological Potential. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1624353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Bian, J.; Damdinjav, D.; Dorjsuren, B.; Finko, A.; Ren, Y.; Wang, D.; Yan, T.; Wang, Z. Natural Flavonoid Glycoside-Based Self-Assembled Nanoparticles for Synergistic Antibacterial Activity and Improved Antioxidant Properties. J. Drug. Deliv. Sci. Tec. 2025, 105, 106583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yang, X.; Shang, X.; Han, W.; Wang, F.; Ban, S.; Zhang, S. Novel Multi-Component Crystals of Berberine with Improved Pharmaceutical Properties. IUCRJ 2023, 10, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, D.; Bai, E.; Zhang, H.; Duan, Y.; Huang, Y. Platensimycin-Berberine Chloride Co-Amorphous Drug System: Sustained Release and Prolonged Half-Life. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2022, 179, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; An, Q.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H. Assembly of Two Palmatine Pharmaceutical Salts: Changing the Motifs and Affecting the Physicochemical Properties by Adjusting the Position of -COOH on Salt Formers. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Tec. 2023, 86, 104634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaipong, K.; Boonprakob, U.; Crosby, K.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Byrne, D. Comparison of ABTS, DPPH, FRAP, and ORAC Assays for Estimating Antioxidant Activity from Guava Fruit Extracts. J. Food Compost. Anal. 2006, 19, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wei, Y.; Li, L.; Song, Y.; Pang, Z.; Qian, S.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y.; Heng, W. Gelation Elimination and Crystallization Inhibition by Co-amorphous Strategy for Amorphous Curcumin. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 112, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madinah, R.; Rusydi, F.; Fadilla, R.; Khoirunisa, V.; Boli, L.; Saputro, A.; Hassan, N.; Ahmad, A. First-Principles Study of the Dispersion Effects in the Structures and Keto-Enol Tautomerization of Curcumin. ACS Omega. 2023, 8, 34022–34033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, W.; Lv, J.; Du, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Y. Preparation of Curcumin–Piperazine Coamorphous Phase and Fluorescence Spectroscopic and Density Functional Theory Simulation Studies on the Interaction with Bovine Serum Albumin. Mol. Pharm. 2017, 14, 3013–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schittny, A.; Huwyler, J.; Puchkov, M. Mechanisms of Increased Bioavailability through Amorphous Solid Dispersions: a Review. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2020, 10, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Fan, C.; Dong, W.; Gao, B.; Yuan, W.; Gong, J. Free Radical Scavenging and Anti-Oxidative Activities of an Ethanol-Soluble Pigment Extract Prepared from Fermented Zijuan Pu-Erh Tea. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 59, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaño, D.; Fernández-Pachón, M.; Troncoso, A.; Garcıa-Parrilla, M. The Antioxidant Activity of Wines Determined by the ABTS+ Method: Influence of Sample Dilution and Time. Talanta 2004, 64, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).