1. Introduction: What the Existence of LLMs Reveals About Thought and Consciousness

Methodological Note: This study employs analogical modeling between artificial and biological systems, grounded in empirical evidence from AI (e.g., entropic decay in autonomous LLM chains; Huang et al., 2024) and evolutionary biology (e.g., developmental canalization; Moreno & Mossio, 2015). While the dual-structure hypothesis includes ontological interpretation, it generates falsifiable predictions testable via long-term AI autonomy and evolutionary simulations.

The emergence of large language models (LLMs) demonstrates that human-like text generation and reasoning patterns can be reconstructed without consciousness (Searle, 1980). This empirical observation has stimulated interdisciplinary research into the functional boundaries of artificial systems (Butlin et al., 2023). We propose that both mind and life operate via a dual architecture: a computational component generating structures (thoughts, biochemical states) and a directional component enabling evaluation, stability, and creativity. Current LLMs replicate the former but lack the latter, leading to informational noise under prolonged autonomous operation (Huang et al., 2024). Through analogies between cognitive and biological systems, this work introduces a falsifiable hypothesis: consciousness and evolutionary creativity are not emergent byproducts but ontologically distinct layers of complex adaptive systems—manifest in life, cognition, and historical dynamics.

An LLM is like a colossal mill that has ground the entire internet. It contains hundreds of billions of “gears”—parameters tuned to linguistic patterns, knowledge structures, and cognitive procedures embedded in human texts. This mill can generate new sentences, answer questions, and propose hypotheses. And yet it does not think—it resembles a giant mechanical cash register with a crank, spinning its gears to produce text. Just gears and levers, realized in silicon chips—nothing more.

This ability to simulate thought without consciousness is key. It suggests that the human mind likely consists of two functional components: one computational, the other conscious (Dennett, 1991). LLMs mirror the former. But without the latter—without consciousness—the machine becomes, under prolonged autonomous operation, a powerful generator of noise, unable to fully assess the relevance of its own outputs (Larson, 2021).

2. Thought Versus Consciousness: Two Components of the Human Mind

In ordinary situations, the human brain activates an internal “transformer”—a generator of linguistic structures that quietly speaks to itself. This component is computational, predictive, and to some extent algorithmic, functionally akin to the transformer architecture of AI systems.

Running in parallel, however, is consciousness—a component that evaluates, directs, and feels. Consciousness is not merely a passive observer, but an active “canalizer” of thought. It creates bias, motivation, and direction (Baars, 1997). Without it, human thinking would resemble Brownian motion of words, lacking long-term orientation.

AI has advantages: it accesses all available knowledge, never forgets, and generates rapidly. But it lacks direction. It has no inner drive. It is like a motorcycle without a rider—fast, but without knowing where to go. A human walks, but knows the destination. AI sees the entire “playing field” of human knowledge brightly lit and races across it. A human sees only the small portion they have studied, walks slowly, and lights the path with a flashlight. They move slowly, but they know where—and that is what matters (Floridi, 2014).

3. Evolution as a Dual Process: Chemistry + Canalization

The evolution of life is often described as the result of a blind process—a combination of mutation, selection, and time. Yet this description is extremely improbable if taken literally (Kauffman & Roli, 2021). The likelihood that complex living systems would arise purely by chance is, according to some estimates, so low that it cannot be considered realistic.

This suggests that evolution involves a form of “canalization”—a directional tendency first formalized by Waddington (1942) and later developed in autopoietic frameworks (Moreno & Mossio, 2015). Chemistry and genetics form the strong component of the system—the part we know and measure. But there may also be a second component—weaker, subtler, yet essential (Maturana & Varela, 1980).

When we ignite paper, it burns according to chemical laws. These laws are strong, dominant, and determine the outcome. But in living systems, something else occurs: a structure emerges that repairs itself, replicates itself, and creates itself. Life does not require a factory. All its parts are “alive”; even the periphery regenerates according to an invisible “internal blueprint.” That is why life remains stable over time and continues to evolve. Machines, by contrast, require maintenance after a while and cannot operate independently for long without failure.

4. Analogy: Mind and Life as Dual-Component Systems

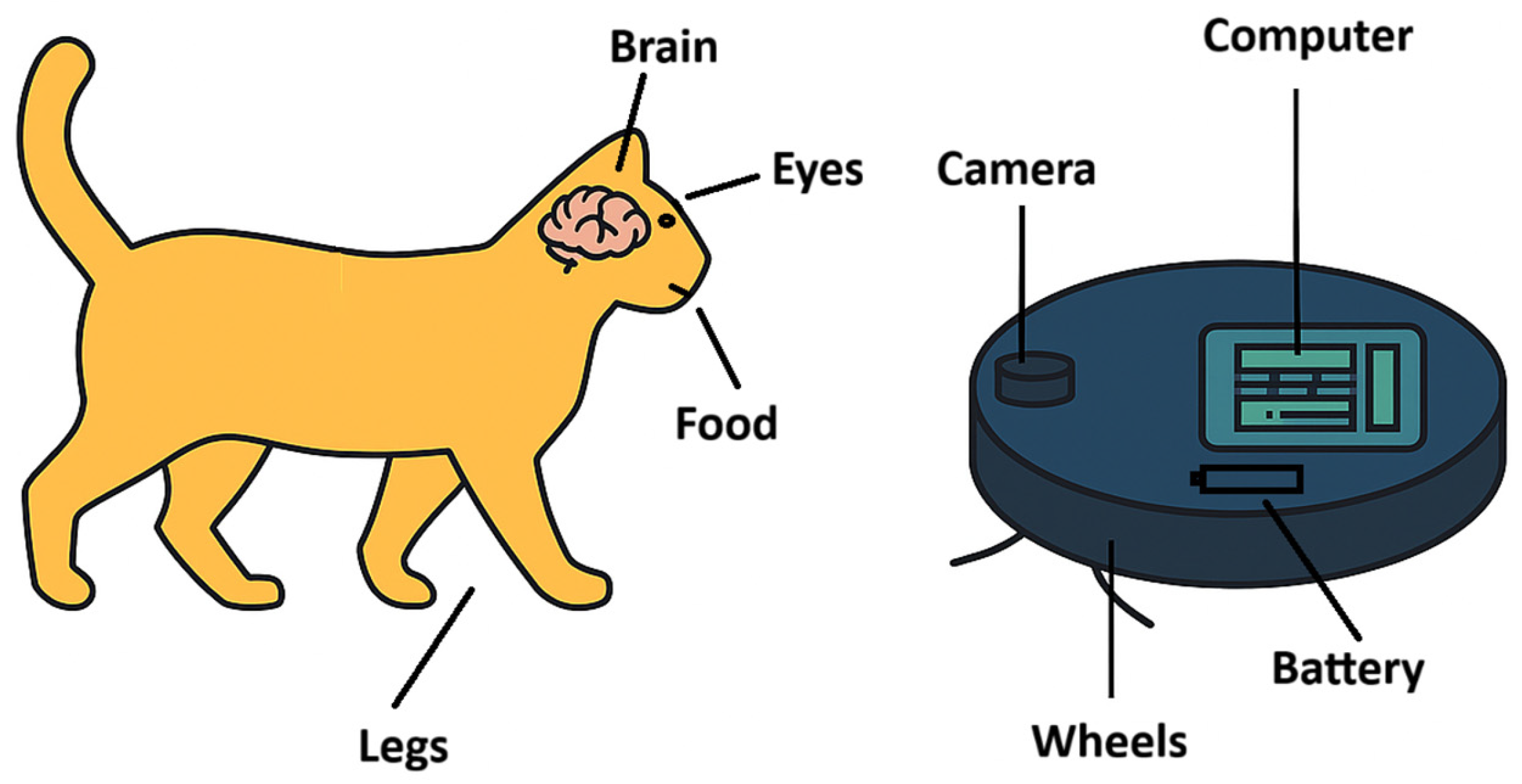

A comparison of the principal differences between organisms and artificial systems is presented in

Table 1.

If this analogy holds, then consciousness and “evolutionary direction” are not mere side effects of computation or chemistry, but distinct components of reality (Polanyi, 1966).

5. A Critique of Reductionism: Why “More Computation” Is Likely Not Enough

Reductionism is the belief that complex phenomena can be fully explained as the sum and interaction of simpler parts. In the domain of AI, it is often assumed that consciousness, motivation, or creativity will “emerge” if the computational system becomes sufficiently complex, or employs sophisticated techniques such as chains of reasoning (Larson, 2021).

This assumption, however, encounters a fundamental problem: a computational component without direction produces noise. In communication channels—for instance, in digital signal processing—it is well established that no signal processing can increase the amount of information contained in the signal. This is known as Shannon’s Data Processing Inequality (Shannon, 1948; Straňák, 2025). Signals tend toward entropy. In AI, the situation is analogous: without consciousness, without an evaluative mechanism, without intrinsic motivation, the outputs of extended reasoning become Brownian motion of words—random noise. This phenomenon has been empirically observed in AI systems many times (Huang et al., 2024).

Contemporary LLM-based AI systems are powerful, but they lack an inner goal. They optimize a loss function, but do not know why. They cannot assess the relevance of their outputs. They cannot effectively self-correct or reorient when they err (Froese & Taguchi, 2019).

Machines wear down, require servicing, and their outputs gradually dissolve into noise. Life, by contrast, creates, repairs itself, and evolves. This suggests that living systems contain something beyond the computational component—something that current science has yet to describe, but which appears essential for stability and creativity. A machine with a sophisticated control computer is, in essence, only half of life: the computational and mechanically predictive half. The other half—consciousness and the canalization of structural stability and development—is missing (Maturana & Varela, 1980), see

Figure 1.

6. A Cautious Hypothesis: There May Exist a Formative Principle We Do Not Yet Know

Consciousness and evolutionary direction may not be mere side effects of computational complexity. They may not be computational in nature at all. It is possible that they represent a different kind of organization of reality—one that current science is not yet able to describe, or perhaps systematically overlooks because it does not fit the prevailing paradigm (Feinberg & Mallatt, 2020).

Science is grounded in what can be measured, modeled, and simulated. But what if there are phenomena that elude this methodology? What if consciousness is not “something that emerges,” but something ontologically distinct—much like the difference between a map and the landscape it depicts (Chalmers, 1995)? Or perhaps such phenomena are measurable, but their intensity is so faint that they continue to be overlooked. Especially when they fall outside the paradigm, and thus few are actively searching for them.

In the case of life, it appears that chemistry alone may not suffice. Genes may not be merely a blueprint, but primarily a form of evolutionary memory. Evolution may not be a random walk through a space of possibilities, but rather a process with an internal direction that we do not yet understand (Moreno & Mossio, 2015).

In the case of mind, it appears that computation is likely not enough. An AI LLM can efficiently generate relevant texts, but it does not know what it is saying. It lacks motivation, direction, and experience. This becomes especially evident during prolonged autonomous operation, when the likelihood of losing coherence, hallucinating, and producing informational noise increases (Huang et al., 2024).

We see its manifestations: in life, in mind, in history. This view resonates with Peirce’s conception of reality as inherently semiotic and generative—a layered process in which meaning, direction, and novelty emerge through structured interaction rather than mere computation (Peirce, 1931–1958).

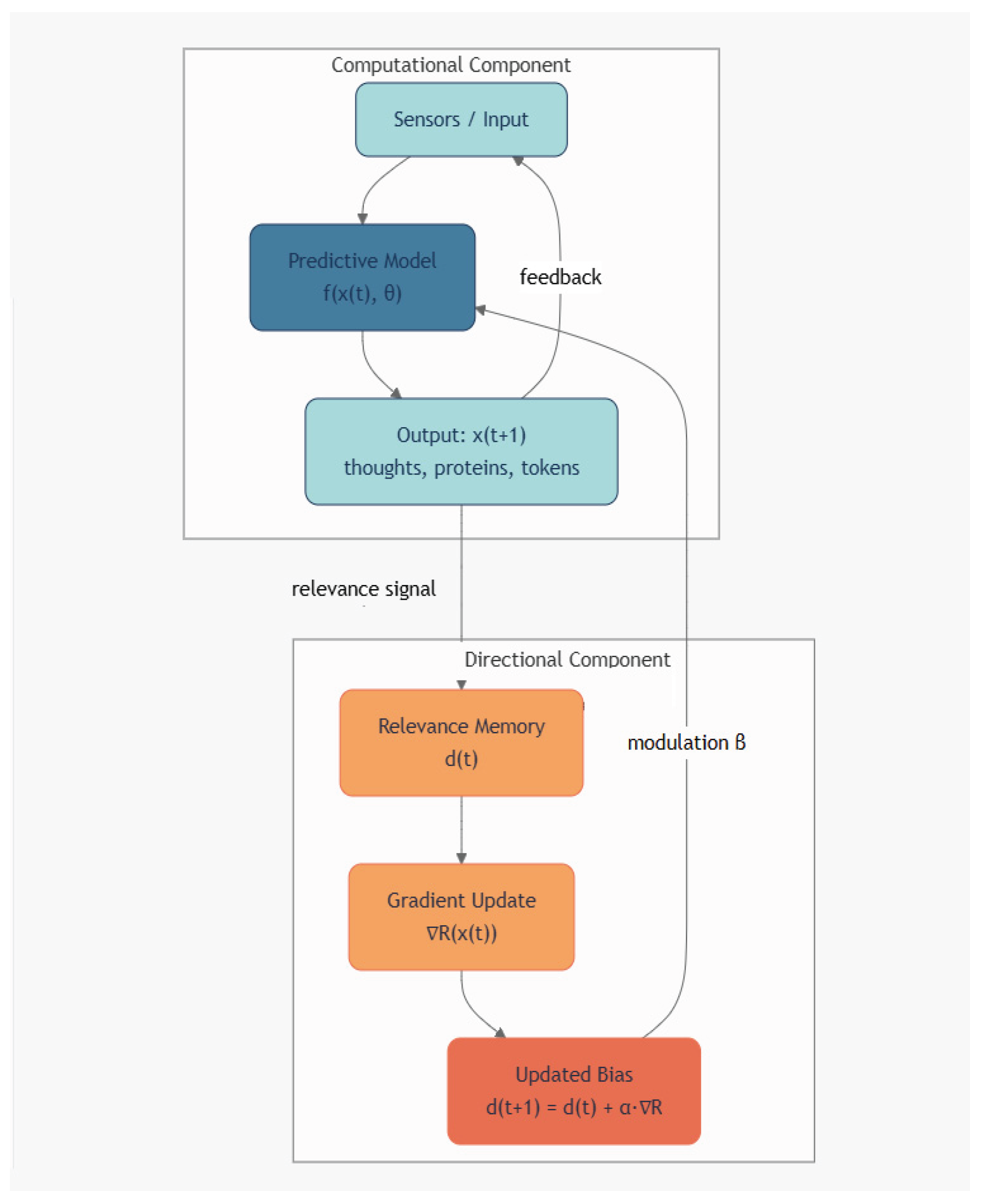

7. Formalization of the Hypothesis Core

To formalize the dual-structure hypothesis, we propose a minimal dynamical model distinguishing a

computational component that generates structures and a

directional component that evaluates and stabilizes long-term coherence. Let

x(

t) represent the system state at time

t (e.g., token sequence in an LLM, biochemical configuration in a cell), evolving via a known generative function f with parameters

θ:

The directional state

d(

t) encodes an internal bias toward relevance or fitness, updated slowly via a relevance gradient

∇R(

x(

t)):

where

α≪1 and

β>0 in living or conscious systems, but

β=0 in current LLMs. When

β=0, the dynamics reduce to pure computation, and Shannon’s Data Processing Inequality implies that mutual information with any distal goal monotonically decreases—predicting the observed entropic collapse in autonomous LLM chains (Huang et al., 2024). In contrast,

β>0 enables sustained coherence and creative exploration, consistent with biological canalization and conscious deliberation. This model is falsifiable: long-term autonomy tests should reveal whether coherence degrades exponentially without a learnable

d(

t), offering an empirical bridge between AI limitations and the ontology of adaptive complexity, see also

Figure 2.

8. Conclusion and Research Implications

LLM-based systems empirically demonstrate that linguistic and cognitive patterns can be generated without consciousness. This work proposes a dual-structure hypothesis for complex adaptive systems: a computational layer (replicated in AI) and a directional layer (absent in current models), responsible for long-term coherence and creativity.

The formal model (Equations 1–2) predicts that in the absence of directional modulation (β=0), autonomous systems undergo entropic collapse, consistent with observed degradation in LLM chains (Huang et al., 2024) and Shannon’s Data Processing Inequality. Conversely, β>0 supports canalized, autopoietic dynamics, enabling sustained coherence and adaptive creativity—features characteristic of biological evolution and conscious cognition.

Research implications: Future empirical studies should evaluate long-term autonomous performance in AI systems (e.g., ≥1000-step reasoning chains without external feedback) and investigate non-random canalization patterns in evolutionary simulations. Exponential decay in output coherence in the absence of a learnable directional state d(t) would provide support for the dual-structure hypothesis; conversely, sustained coherence without such a mechanism would falsify it. This framework thus establishes a rigorous, falsifiable link between observed limitations in artificial autonomy and the theoretical foundations of adaptive complexity in biological and cognitive systems.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. This manuscript presents a theoretical framework and does not report empirical data.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks colleagues for discussions that shaped this work. This research was conducted independently without institutional funding. Some passages of this manuscript were prepared or refined with the assistance of a large language model (LLM). The author takes full responsibility for the content and conclusions presented herein.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that no competing interests exist.

References

- Baars, B.J. In the Theater of Consciousness: The Workspace of the Mind; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Butlin, P.; Long, R.; Elmoznino, E.; Bengio, Y.; Birch, J.; Constant, A.; Deane, G.; Fleming, S.M.; Frith, C.; Ji, X.; et al. Consciousness in artificial intelligence: Insights from the science of consciousness. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, D.J. Facing up to the problem of consciousness. J. Conscious. Stud. 1995, 2, 200–219. [Google Scholar]

- Crick, F. Central dogma of molecular biology. Nature 1970, 227, 561–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennett, D.C. Consciousness Explained; Little, Brown and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg, T.E.; Mallatt, J.M. Phenomenal consciousness and emergence: Eliminating the explanatory gap. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floridi, L. The Fourth Revolution: How the Infosphere is Reshaping Human Reality; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Froese, T.; Taguchi, S. The problem of meaning in AI: Formal models and biological behavior. Minds Mach. 2019, 29, 385–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yu, W.; Ma, W.; Zhong, W.; Feng, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Peng, W.; Feng, X.; Qin, B.; et al. A survey on hallucination in large language models: Principles, taxonomy, challenges, and open questions. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S.; Roli, A. The world is not a theorem. Entropy 2021, 23, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, E.J. The Myth of Artificial Intelligence: Why Computers Can’t Think the Way We Do; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living; D. Reidel Publishing Company: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Mossio, M. Biological Autonomy: A Philosophical and Theoretical Enquiry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, T. What is it like to be a bat? Philos. Rev. 1974, 83, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, C.S. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce; Hartshorne, C., Weiss, P., Burks, A.W., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1931–1958; Volumes 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi, M. The Tacit Dimension; Routledge & Kegan Paul: Abingdon, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, J.R. Minds, brains, and programs. Behav. Brain Sci. 1980, 3, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straňák, P. (2025). Lossy loops: Shannon’s DPI and information decay in generative model training. Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Su, J. Consciousness in artificial intelligence: A philosophical perspective through the lens of motivation and volition. Crit. Debates Humanit. 2024, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Waddington, C.H. Canalization of development and the inheritance of acquired characters. Nature 1942, 150, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).