1. Introduction

The Arctic is often called the "World’s treasure trove" due to the vast reserves of mineral resources hidden here. Oil, gas, rare earth metals, diamonds, etc. are recovered in Russian Arctic region. Intensive industrial activity leads to emergency situations and the accumulation of environmental damage [

1]. The elimination of pollution from petroleum products and heavy metals is an important task for the preservation of this vulnerable region. Modern technologies of soil purification include physical and chemical methods, which are not always applicable in the conditions of the North due to harsh climate and imperfect logistics [

2]. Bioremediation is considered an eco-friendly, economical, and sometimes the only possible method to restore polluted soils in the Polar regions [

3]. It is the most effective method, leading to the complete mineralization of hydrocarbons [

4]. The possibilities of bioremediation, including biostimulation (fertilization, moistening, aeration) and bioaugmentation (introduction of additional oil-degrading bacteria), are described in detail in reviews [

5,

6]. Adverse environmental conditions, a short growing season, and poor soils determine the persistence of anthropogenic pollution and extremely low rates of soil self-purification in the Polar regions. Decreasing temperature leads to an increase in the viscosity of spilled oil and delayed evaporation of low-molecular-weight toxic compounds, which slows down the microbial degradation of hydrocarbons [

7]. Although microbial activity has been proven even at subzero temperatures, the rate of hydrocarbon biodegradation under such conditions is extremely low [

8,

9,

10]. The ability of soil microbiota to resist oil pollution depends on the type of pollutant and the duration of exposure [

11]. Over time, the pollutant penetrates into the pores of soil aggregates, its polymerization occurs, and it reacts with soil humus, complicating the biodegradation process [

12,

13]. In Antarctic soils, hydrocarbons persisted and were detected more than 40 years after contamination [

14].

When soils are contaminated simultaneously with petroleum products and heavy metals (HMs), microorganisms are subjected to double stress and are forced to adapt to several additional aggressive factors. The simultaneous effect of petroleum products and heavy metals on the microbial community has been poorly studied. While hydrocarbons can be completely degraded by microorganisms to carbon dioxide and water, heavy metals remain in the soil. The mechanisms of interaction between microorganisms and metals can be different, associated with cellular metabolism and specific enzymes (intracellular separation and extracellular precipitation) or simple physicochemical interactions (adsorption on cell wall components) [

15,

16]. Microorganisms are capable of participating in the accumulation and sorption of heavy metals, affecting their solubility, toxicity, and mobility [

17,

18]. The combined use of bacteria and plants promotes the conversion of heavy metals into safer forms and their removal from soils

in situ, which is important for soil restoration in hard-to-reach places [

19]. Iron-reducing microorganisms possess enzymes that reduce heavy metals and metalloids such as U(VI), Tc(VIII), Cr(VI), and Co(III), using acetate, lactate, pyruvate, and aromatic hydrocarbons as substrates [

20,

21,

22]. The ability to grow on hydrocarbons with the reduction of heavy metals has been shown for bacteria of the genera

Geobacter and

Rhizobium [

23,

24].

The presence of anthropogenic pollutants in the soil leads to changes in the composition of the microbial community, an increase in the proportion of groups tolerant to it, and the disappearance of sensitive ones. Soil pollution with heavy metals leads to the inhibition of microorganism growth and hydrocarbon biodegradation [

25,

26,

27].

The choice of remediation technology used depends on the characteristics of the soils, the pollutant, and environmental conditions [

28,

29]. The rate of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) degradation depends on the type of hydrocarbons, the target oil-degrading strain, or consortium of strains [

30]. The selection of fertilizers for Northern soils, initially poor in nitrogen and phosphorus, has shown that oligotrophic biostimulation is more effective than eutrophic approaches [

31].

Under laboratory conditions was shown that the most effective method for cleaning soil from PAHs was a combination of biostimulation and bioaugmentation [

32]. In addition to fertilizers, an enrichment culture of oil-oxidizing bacteria isolated from the same soil was introduced, which allowed for the removal of 87% of the pollutant in 80 days, while self-purification achieved only 42%. Heavy metals had less effect on the microbial community than PAHs in soils with aged PAHs and HMs contamination [

33].

The goal of the present work was to determine the composition of microorganisms in Russian Subarctic soil with long-standing pollution by petroleum products and heavy metals and outside this zone, and the potential ability of microorganisms to participate in the self-purification of the soil.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description and Soil Sampling

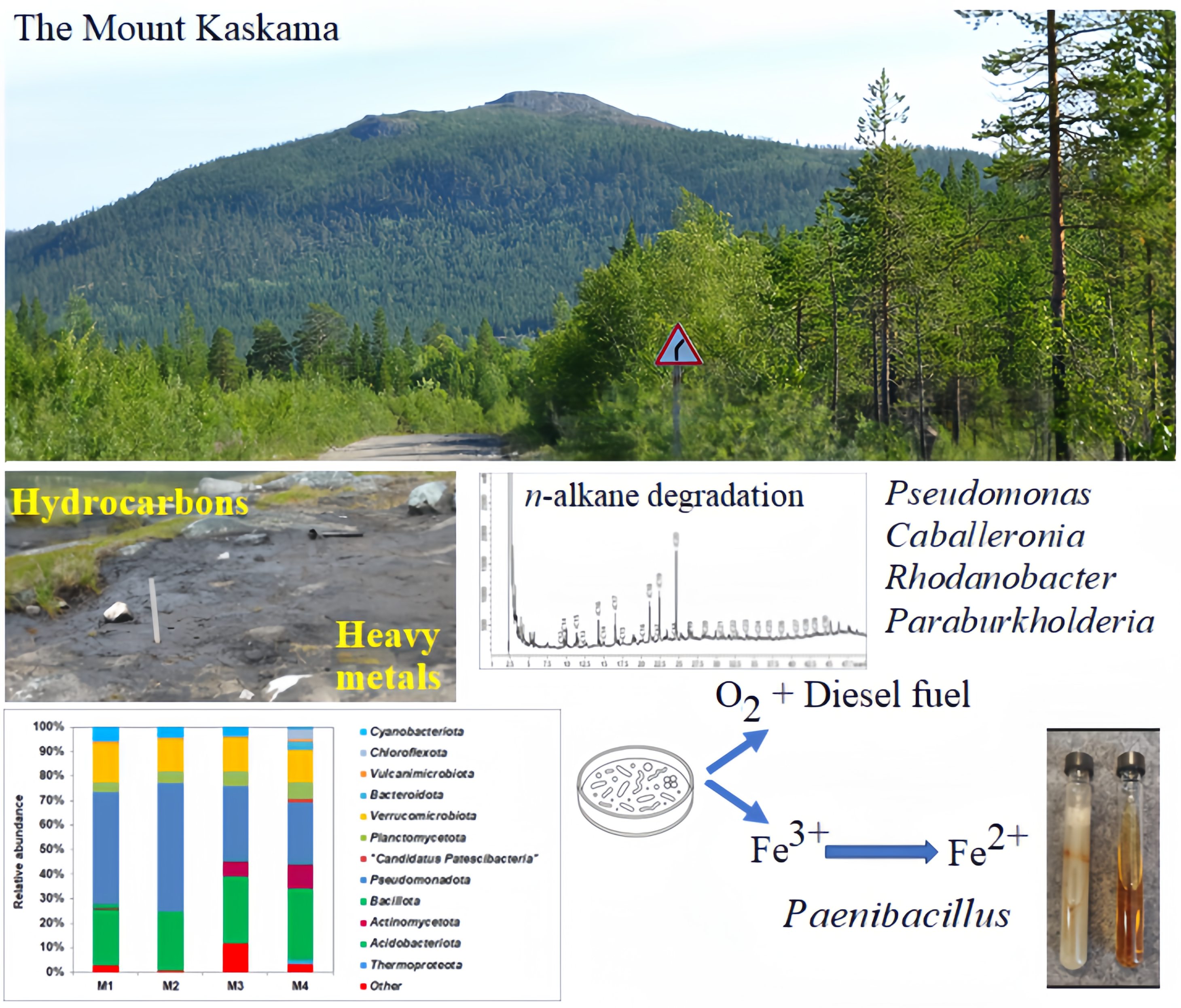

Soil samples were collected on October 07, 2022, and August 02, 2023, on the southeastern slope of Mount Kaskama (N 69° 16' 44''; E 29° 28' 33''; Pechengsky District, Murmansk Region, Russia). Mount Kaskama is located in the subarctic climate zone, and the sampling site, considering altitudinal zonation, can be classified as a mountain tundra zone [

34]. The height of the sampling point was about 300 m; it was located 50 m downhill from the top.

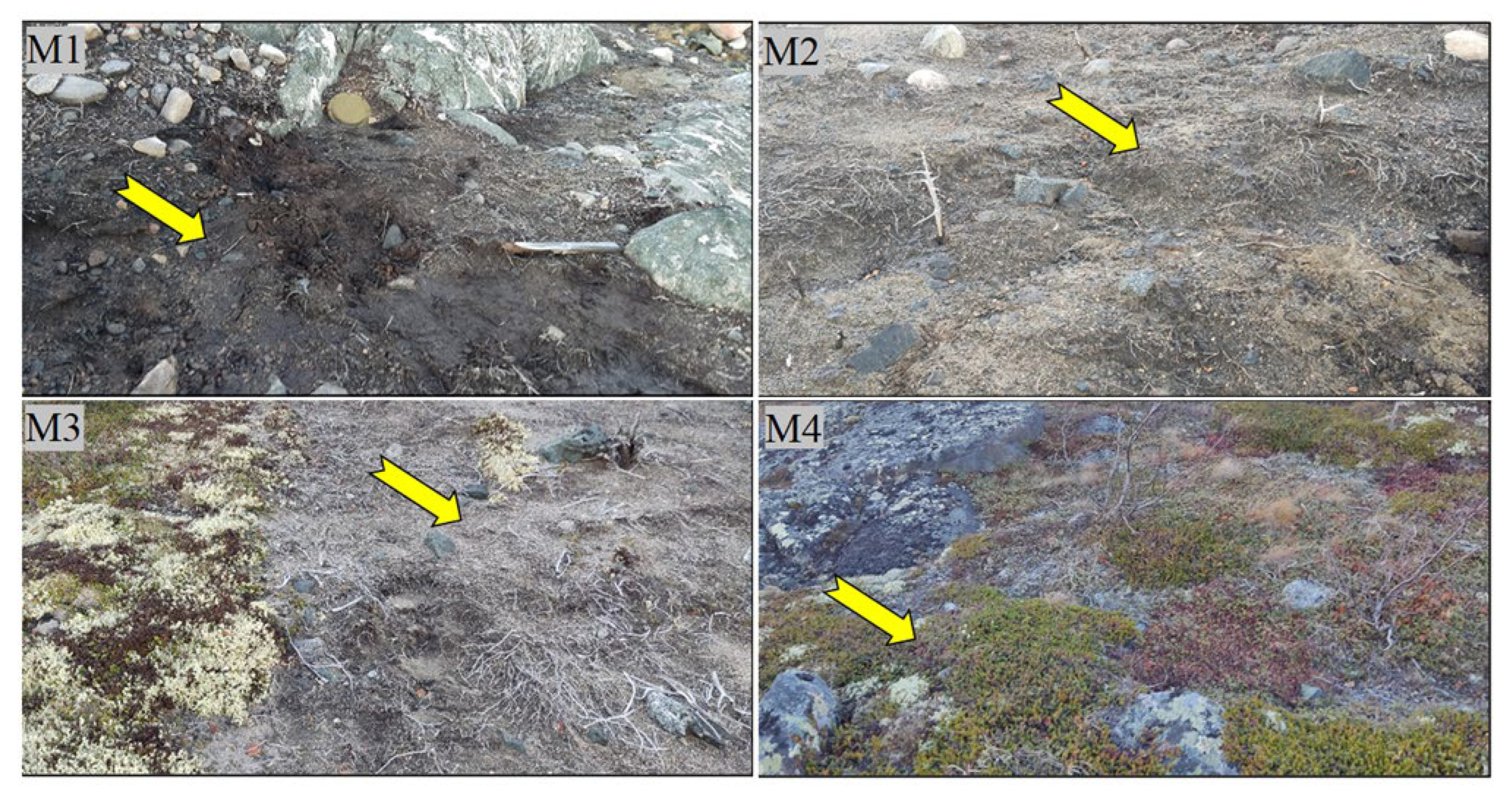

As a result of anthropogenic impact, a zone of long-standing contamination (over 20 years) with petroleum products (presumably fuels and lubricants), scrap metal, and fragments of equipment had formed. Four sites were selected – from the center of the visible fuel pollution towards the periphery, arranged in a horizontal line approximately 10 m apart from each other (

Figure 1). Sites No. 1 and No. 2 were located directly within the contaminated area, site No. 3 was on the border of the contaminated and conditionally clean zone, and site No. 4 was on the conditionally clean zone (with no visible fuel contamination and with preserved vegetation cover). In 2022, samples were collected from depths of 0–10 cm and 10–15/20 cm from the surface (at the boundary with the underlying rocks) aseptically into sterile containers using the X-shaped sampling method. In 2023, samples were collected from a depth of 0–20 cm. The collected samples were stored at +4°C until analysis.

2.2. Culture Media Composition

The number of microorganisms was determined by the tenfold serial dilution method on selective media. The average weight of the soil sample (10 g) was mixed with 90 ml of sterile tap water and shaken for 30 min at 110 rpm. After precipitation of large particles for 1–2 minutes, the resulting aqueous suspension was used for inoculation of selective media. Aerobic organotrophic bacteria (AOB) were enumerated in a liquid R2A medium (per liter distilled water): 0.5 g peptone; 0.5 g yeast extract; 0.5 g glucose; 0.5 g casein hydrolysate; 0.5 g starch; 0.3 g Na pyruvate; 0.3 g K

2HPO

4; 0.024 g MgSO

4·7H

2O; 1.0 g NaCl; pH 6.0 ± 0.2 [

35]. Oligotrophic bacteria (OL) were enumerated on a medium (per liter distilled water): 0.8 g Na

2HPO

4; 0.5 g KH

2PO

4; 0.5 g NH

4Cl; 0.2 g MgSO

4; 0.1 g CaCl

2·2H

2O; 1.0 g NaCl; 0.05 g yeast extract, pH 6.0 ± 0.2. Hydrocarbon-oxidizing bacteria (HOB) were analyzed on a medium (per liter distilled water): 0.75 g KH

2PO

4; 1.5 g K

2HPO

4; 1.0 g NH

4Cl; 1.0 g NaCl; 0.1 g KCl; 0.2 g MgSO

4·7H

2O; 0.02 g CaCl

2·2H

2O, pH 6.0 ± 0.2.. After sterilization, 0.1% (

v/

v) sterile diesel fuel was added to the medium as a carbon source. To determine the number of iron-oxidizing bacteria (FeOx), a medium [

36] was used (per liter distilled water): 0.5 g K

2HPO

4; 0.5 g (NH

4)

2SO

4; 0.5 g NaNO

3; 0.5 g MgSO

4·7H

2O; 5.9 g FeSO

4·7H

2O; 10.0 g citric acid; 2.0 g sucrose; 1.0 g tryptone; рН 6.6–6.8.

Anaerobic microorganisms were cultivated in Hungate’s tubes. Argon was used as the gas phase. Fermentative bacteria were enumerated on a medium (per liter distilled water): 10.0 g glucose; 4.0 g peptone; 2.0 g Na

2SO

4; 1.0 g MgSO

4; 0.5 g FeSO

4(NH

4)

2SO

4·6H

2O; pH 6.0 ± 0.2. For iron-reducing bacteria (FeRed), a medium [

37] of the following composition was used (per liter distilled water): 1.5 g NH

4Cl; 1.0 g NaCl; 0.75 g KH

2PO

4; 1.5 g K

2HPO

4; 0.1 g CaCl

2·2H

2O; 0.6 g NaH

2PO

4·H

2O; 0.1 g MgCl

2·6H

2O; 0.1 g KCl; 0.005 g MnCl

2×4H

2O; 0.001 g Na

2MoO4; 2.5 g NaHCO

3 16.2 g Fe

3+ citrate; 2.0 g Na acetate; 5.0 g yeast extract; рН 7.0±0.2. A trace elements solution (1 ml·L

–1) [

38] was added to each medium after sterilization. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Cultivation was carried out for 14 days at 15 °C.

The growth of AOB and OL was determined by changes in the medium turbidity. The growth of iron-oxidizing bacteria was determined by the color change of the medium from light green to rusty brown. The growth of fermentative bacteria was assessed by the increase in H2 and CO2 in the gas phase. The growth of iron-reducing bacteria was detected by a decrease in Fe3+ and an increase in Fe2+ content, determined by the method of complexometric titration with sulfosalicylic acid. Microbial growth was also controlled by microscopy.

Pure cultures of AOB were isolated on R2A agar medium. The temperature range for bacterial growth was determined on R2A medium, and the salinity range was determined on R2A medium with varying NaCl content. The growth of iron-reducing bacteria on hydrocarbons was determined on the medium [

37] without yeast extract and acetate, supplemented with diesel fuel (2 g·L

–1). Bacterial growth on crude oil and other substrates was determined on the mineral medium for HOB; sugars and protein substrates were added at a concentration of 5 g·L

–1, salts of organic acids and alcohols – 2.5 g·L

–1, crude oil and diesel fuel – 2.0 g·L

–1. Growth in the presence of heavy metals was determined in liquid R2A medium; heavy metals were added as NiCl

2·2H

2O, CuSO

4·2H

2O, and Pb(NO

3)

2 to final concentrations of Ni

2+ – 40 μg·L

–1, Cu

2+ – 75 μg·L

–1, and Pb

2+ – 100 μg·L

–1. The effect of metals on bacterial growth was evaluated (in %) by the ratio of turbidity in cultures grown on R2A medium without heavy metals and with metals.

2.3. Analytical Methods

The gas phase composition was determined using a "Kristall 5000.2" chromatograph ("Khromatek", Russia). The actual acidity of the soil and soil moisture were determined as described previously [

34]. The total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPHs) were extracted from a soil sample with tetrachlorocarbon; the extract was purified on a column with aluminum oxide and then examined by using the AN-2 analyzer [

34]. The biodegradation of petroleum

n-alkanes was analyzed as described previously [

39]. The total content of heavy metals was determined by atomic absorption spectrometry using a spectrometer AAS "Kvant-2M" ("Kortek", Russia) after microwave digestion of the soil sample in a mixture of concentrated hydrochloric acid, nitric acid, and hydrofluoric acid (MVI 80–2008).

2.4. DNA Isolation and the 16S rRNA Gene V3–V4 Fragments Sequencing

DNA from pure cultures was isolated using the Fast DNA Spin Kit (MPBio, Solon, Ohio, USA), followed by amplification of the 16S rRNA gene with universal primers 8–27f and 1492r [

40]. Sequencing was performed on a 3730 DNA Analyzer using the BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kits (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). Assembly and analysis of the obtained sequences were performed using the Bioedit package (

http://jwbrown.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html, accessed on 9 October 2025) and the GenBank database using the BLAST algorithm (NCBI server,

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/, accessed on 17 September 2025). For DNA isolation from soil samples, the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro DNA isolation kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions and an average weight of the soil sample (10 g). The PCR amplification of 16S rRNA gene fragments comprising the V3–V4 variable regions was carried out using the universal prokaryotic primers 341F_Fr (5′–CCT AYG GGD BGC WSC AG–3′) and 806R_Fr (5′–GGA CTA CNV GGG THT CTA AT–3′) as described previously [

41,

42].

2.5. Bioinformatic Analysis

The quality of the obtained V3–V4 region sequences was analyzed using UPARSE software [

43], and then grouped into OTUs with ≥97% similarity using USEARCH [

44]. The OTUs were taxonomically identified using SILVA v.138 rRNA sequence database and the VSEARCH v. 2.14.1 algorithm (SILVA release 138.1) [

45]. Further sequence analysis was performed as described previously [

42]. A heat map of community members at the genus level was constructed using the ClustVis online resource [

46]. Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) was performed in the PAST 4.03 program [

47].

2.6. Nucleotide Sequence Accession Number

The 16S rRNA gene V3–V4 fragment sequences of M1–M4 microbial communities have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and are available via the BioProject PRJNA1346952. Nucleotide sequences of the 16S rRNA gene of pure cultures were deposited into GenBank under accession nos: PX457869, PX457873, PX464108, PX457728, PX462097, PX462100, PX462107, PX462110, PX457785, PX463341, PX463725–PX463727, PX457871, PX457722, PX457868, PX460839, PX457726, and PX463338.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Characteristics of the Soil Samples and Culturable Microorganisms

The physicochemical parameters of the soils sampled in different climatic seasons (October 2022 and August 2023) are shown in

Table 1. The measured humidity and temperature values corresponded to the climatic norms of the Murmansk region. The temperature in October was 11–12 °C lower than in August. Soil moisture increased significantly in autumn (and exceeded 80%); this indicator was highest in the area with maximum hydrocarbon pollution (M22-1–M22-3 sites). The pH values of the aqueous soil extracts ranged from 4.33 to 6.39 in October and 5.75–5.80 in August, which may be related to the precipitation regime. Petroleum products were found in all the samples studied, even in a visually clean area (M22-4). In 2022, the total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) concentration in the upper layer of Site 4 (M22-4-(0-10)) exceeded the approximate permissible concentration (APC), but was significantly lower than at sites M22-1–M22-3.

The content of petroleum products in the lower soil layer was higher than on the surface, with the exception of site M22-4. A similar distribution and seepage of hydrocarbons (HC) deep into the soil has previously been noted by researchers [

48]. The binding of HC to the soil matrix decreases their bioavailability and makes soil restoration more difficult. Changes in the TPH concentration in 2022 and 2023 can be caused by the process of soil self-purification, a certain mobility of the pollutant in mountainous conditions, and heterogeneity of pollution.

The content of heavy metals in almost all M1-M4 sites was higher of approximate permissible concentration (APC). The Cd content was more than 3 times higher, and for Cu and Ni it was more than 2 times higher than the corresponding value of the APC. The visually clean site M4 was also significantly polluted with Cu and Ni, and the Cd content in was also higher than APC value in 0-10 cm soil layer. But in the 10-20 cm soil layer of site M4, the content of heavy metals was below the APC.

The number of culturable microorganisms of the main physiological groups (

Figure S1) was determined in all selected soil samples. It is known that a change in season leads to changes in the composition and abundance of microorganisms in the soil, with temperature and humidity being the main factors [

49,

50]. On average, the microbial community was more numerous in soil samples taken in August, when the air temperature was 16-17 °C, than in soils taken in October, at 4-5 °C. In the 2023 samples, the abundance of FeOx and fermentative bacteria was highest in the most polluted M1 sample and decreased as it moved away from the contaminated zone. A high abundance of oligotrophic microorganisms is typical for the soils of the northern regions [

51]. The data obtained are consistent with those presented earlier [

52]. A change in the sampling depth of 0–10 and 10–20 cm did not lead to a significant change in the number and redistribution of the physiological groups of the studied microorganisms.

3.2. Microbial Diversity

The composition of prokaryotes was determined in soil samples, taken in 2023 year, using high-throughput of 16S rRNA gene V3–V4 fragments sequencing.

Among the studied samples, the alpha diversity was slightly higher in the uncontaminated M4 site, as evidenced by a higher Shannon index compared to other soil samples (

Table S1). It is likely that a number of microorganisms are sensitive to contamination by petroleum products and heavy metals. The values of the Shannon index for all samples M1–M4 were comparable and even exceeded the values for other, including Arctic, soils [

33,

49,

53,

5][]. In general, it seems that the soil community has adapted to pollutants. The presence of numerous minor representatives suggests a significant diversity. Rare taxa (minor in the soil community) are able to survive under certain conditions even in polluted sites and may play a role in regulating microbial interactions in response to environmental changes [

55].

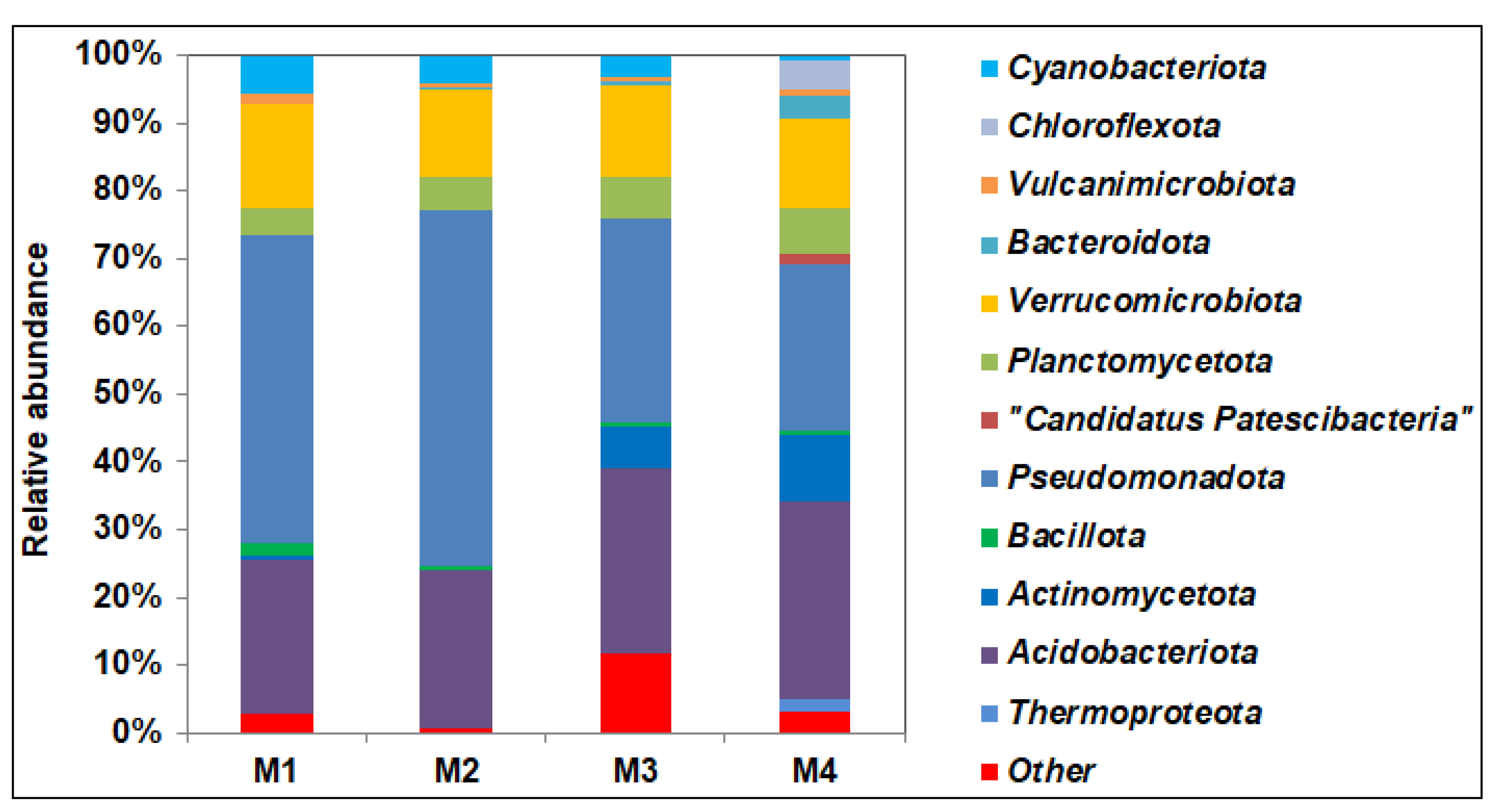

Bacteria dominated in all soil samples obtained; the proportion of Archaea did not exceed 2% (of the total number of sequences in the library) and was highest in the M4 sample (

Figure S2). 16S rRNA gene sequencing confirmed community shift in the contaminated soil. An increase in the content of petroleum products in the soil led to a significant increase in the proportion bacteria of the phyla

Pseudomonadota (from 23.6 to 45.4–52.5%),

Verrucomicrobiota (from 13.2 to 15.4%),

Cyanobacteriota (from 0.7 to 5.7%), and

Bacillota (from 0.4 to 1.72) and a decrease of

Acidobacteriota,

Actinomycetota,

Planctomycetota,

Thermoproteota,

Bacteroidota, and

Candidatus Patescibacteria (

Figure 2). Despite the fact that the phylum

Actinomycetota contains active hydrocarbon degraders, its share in the M1 sample is significantly lower than that of the phylum

Pseudomonadota, whose representatives apparently gained an advantage here due to rapid growth and broad metabolic abilities. This distribution was previously detected in soils with long-standing creosote contamination [

56]. The predominance of proteobacteria over actinobacteria in the community was noted also in soils in cold regions [

57,

58]. The predominance of

Pseudomonas in soil microbial communities, in response to pollution by hydrocarbons and heavy metals has been shown in laboratory conditions [

55].

In accordance with the slightly acidic conditions in the soils, the bacteria of the

Acidobacteriota phylum adapted to these conditions prevailed in the microbial community. It is one of the most widespread soil bacterial phyla found worldwide, from tropical agricultural to Arctic soils and sphagnum peat bogs [

59,

60,

61].

Acidobacteriota have been found in microbial communities of bottom sediments of reservoirs contaminated with uranium (U) [

62]. For chronically polluted soils around the oldest oil wells in Poland, as well as in the communities we studied, there was a decrease in the proportion of

Acidobacteriota as pollution increased [

63]. The authors found the greatest diversity in communities of samples taken directly near the well, where

Mycobacteriaceae,

Methylococcaceae,

Bradyrhizobiaceae,

Rhizobiaceae,

Rhodobacteraceae,

Acetobacteraceae,

Hyphomicrobiaceae, and

Sphingomonadaceae bacteria dominated.

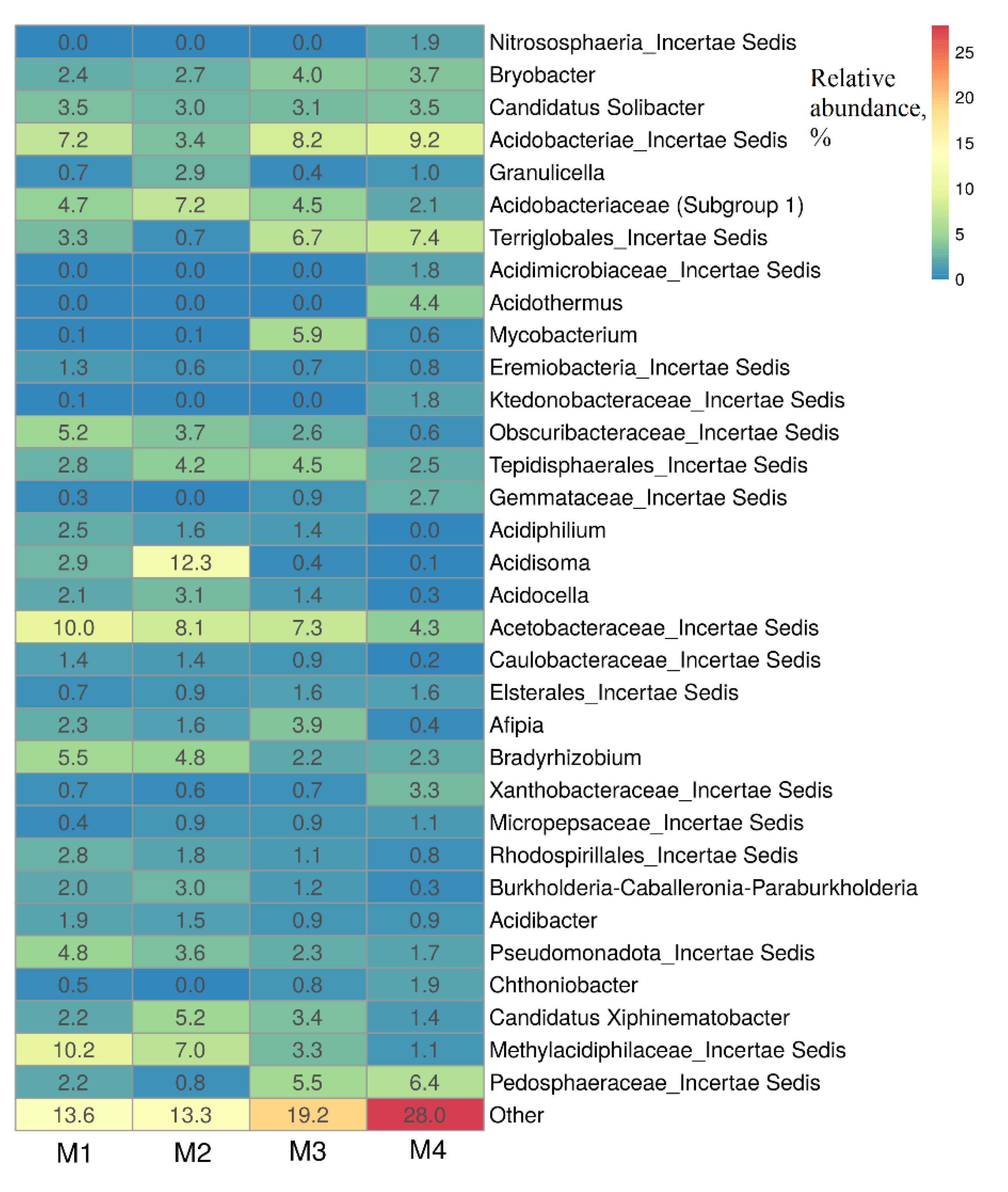

In the M1–M4 soil samples were detected uncultivated bacteria of the families

Acetobacteraceae,

Acidobacteraceae,

Methylacidiphilaceae, as well as bacteria of the genera

Acidisoma,

Bryobacter,

Acidothermus,

Acidocella,

Acidiphilum and others (

Figure 3).

These bacteria include acidophilic and acidotolerant heterotrophic bacteria capable of growing at low temperatures, such as

Acidisoma bacteria isolated from acidic tundra soil [

64]. Bacteria of the genus

Bryobacter, identified in all M1–M4 samples, are chemoorganotrophs, which were previously isolated from acidic sphagnum peat bogs [

59].

In the studied soil samples the increase in the

Pseudomonadota was not due to the rapidly growing

Gammaproteobacteria, which includes the most famous oil-degrading bacteria of the genera

Pseudomonas,

Marinobacter, and

Alkanivorax but due to

Alphaproteobacteria (genera

Acidiphilum,

Acidisoma,

Acidocella, and

Bradyrhizobium). These bacteria are adapted to inhabit acidic soils, mines, and swamps [

64]. Bacteria of the genus

Acidiphilum are resistant to the presence of heavy metals [

65]. Strains of

Acidocella aromatica are able to grow on phenol, reduce Fe

3+, and resistant to heavy metals [

66]. Nodule bacteria of the genus

Bradyrhizobium are resistant to heavy metals and pesticides, contain genes determining the oxidation of aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons, and have been found in microbial communities of oil-contaminated soils [

67,

68,

69,

70]. Bacteria of the genus

Burkholderia, belonging to the class

Betaproteobacteria of the phylum

Pseudomonadota, are capable of using hydrocarbons, and have been isolated from various sources, including oil-contaminated soils [

71]. The

Burkholderia fungorum FM-2 strain, which oxidizes phenanthrene in a wide range of pH values and resistant to heavy metals, was isolated from the oil-contaminated soil of an oil field in China [

27]. Microbial communities of the studied soils also contained uncultivated bacteria. The search for conditions for the isolation and research of such microorganisms will make it possible to better understand the functioning of the entire soil community of Polar soils [

72].

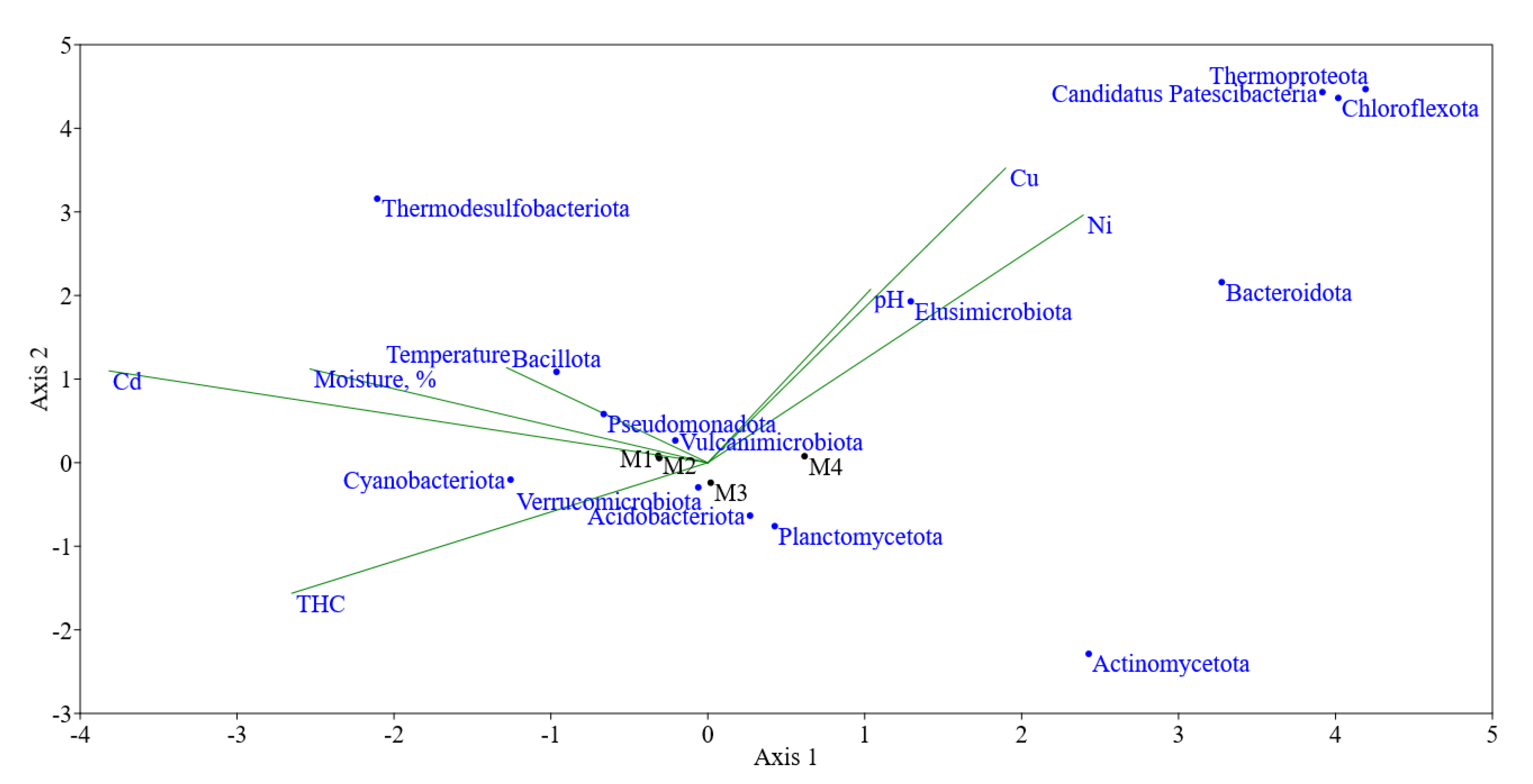

Canonical correspondence analysis showed that a positive correlation can be traced for the content of hydrocarbons in the soil, probably as a substrate used (

Figure 4). If we consider the effects of heavy metals, the correlation was positive for Cu and Ni, and negative for Cd, which is associated with its higher toxicity. Previously, for soils chronically subjected to hydrocarbon and polymetallic contamination, it was shown that PAHs rather than heavy metals have a greater impact on the community [

33].

3.3. Culturable Hydrocarbon-Oxidizing Bacteria Isolated from Contaminated Soil

A total of 20 strains of aerobic heterotrophic bacteria were isolated from soil samples taken in 2022–2023 years (

Table S2). The isolated strains belonged to different taxonomic groups. Most of the pure cultures were gram-negative bacteria, and belonged to the

Pseudomonadota phylum of the classes

Betaproteobacteria (genera

Caballeronia and

Paraburkholderia) and

Gammaproteobacteria (genera

Pseudomonas and

Rhodanobacter). Isolated gram-positive bacteria of the genera

Bacillus,

Cytobacillus, and

Paenibacillus belonged to the

Bacillota phylum and were found among the minor components of the M1–M4 soil communities. Most of the isolates belonged to the genus

Pseudomonas, which can be explained by their high growth rate under specified laboratory conditions.

For further work, 10 strains effectively degrading diesel fuel were selected and their adaptability to the environment was determined, including the temperature range for growth, the use of hydrocarbons and resistance to heavy metals. All the studied strains of the genera

Pseudomonas,

Caballeronia,

Rhodanobacter, and

Paraburkholderia were psychrotolerant, able to grow at low temperatures and at low optimal NaCl content for growth (0–2%,

w/

v) (

Table 2). The substrates used included carbohydrates, alcohols, and volatile fatty acids. The ability to oxidize divalent iron has been shown for

Pseudomonas strains. The strains were able to grow on diesel fuel and crude oil. Most strains used medium-chain

n-alkanes;

P. yamanorum M22-22H and

P. fluorescens M23-K6fo strains used both medium-chain and long-chain

n-alkanes from crude oil (

Figure S3).

Previously, the ability of the indigenous soil microfungi and bacteria for hydrocarbon degradation was demonstrated in a field experiment on the western slope of Mount Kaskama [

34], where aeration and fertilization of the oil-contaminated soil led to a 47% reduction in total hydrocarbon content. The genus

Pseudomonas is probably one of the most studied, the bacteria have a flexible metabolism, a wide range of substrates used (including hydrocarbons), resistance to heavy metals, are found in soils of different geographical regions and are applicable in many biotechnologies [

73]. Bacteria of the genera

Rhodococcus,

Pseudomonas, and

Bacillus have been repeatedly found in oil-contaminated polar soils of the Arctic and Antarctica [

74].

The genus

Caballeronia was formed through the transfer of a number of bacteria from the genus

Burkholderia. These bacteria have been isolated from various types of soil and rhizosphere, grow in a wide range of pH values (from 4.0 to 10.0), and are capable of degrading aromatic compounds and xenobiotics [

75,

76]. A strain of

Paraburkholderia fungorum JT-M8 is described, capable of self-regulation of Cd ion concentration in the cytoplasm and on the cell surface under conditions of simultaneous contamination with PAHs and heavy metals (Cd) with phosphorus deficiency [

77]. Bacteria of the genus

Rhodanobacter are tolerant to low pH values and to contamination with heavy metals, including nickel, copper, and cadmium [

78,

79,

80]. They are found in microbial communities that degrade crude oil [

81]. In the microbial community of oil-contaminated soils of the subarctic zone,

Rhodanobacter ginsengisoli was one of the dominant oil degraders [

82]. Spore-forming bacteria of the genera

Bacillus and

Cytobacillus are common inhabitants of soils, including the soil of the Polar region [

5,

52,

83].

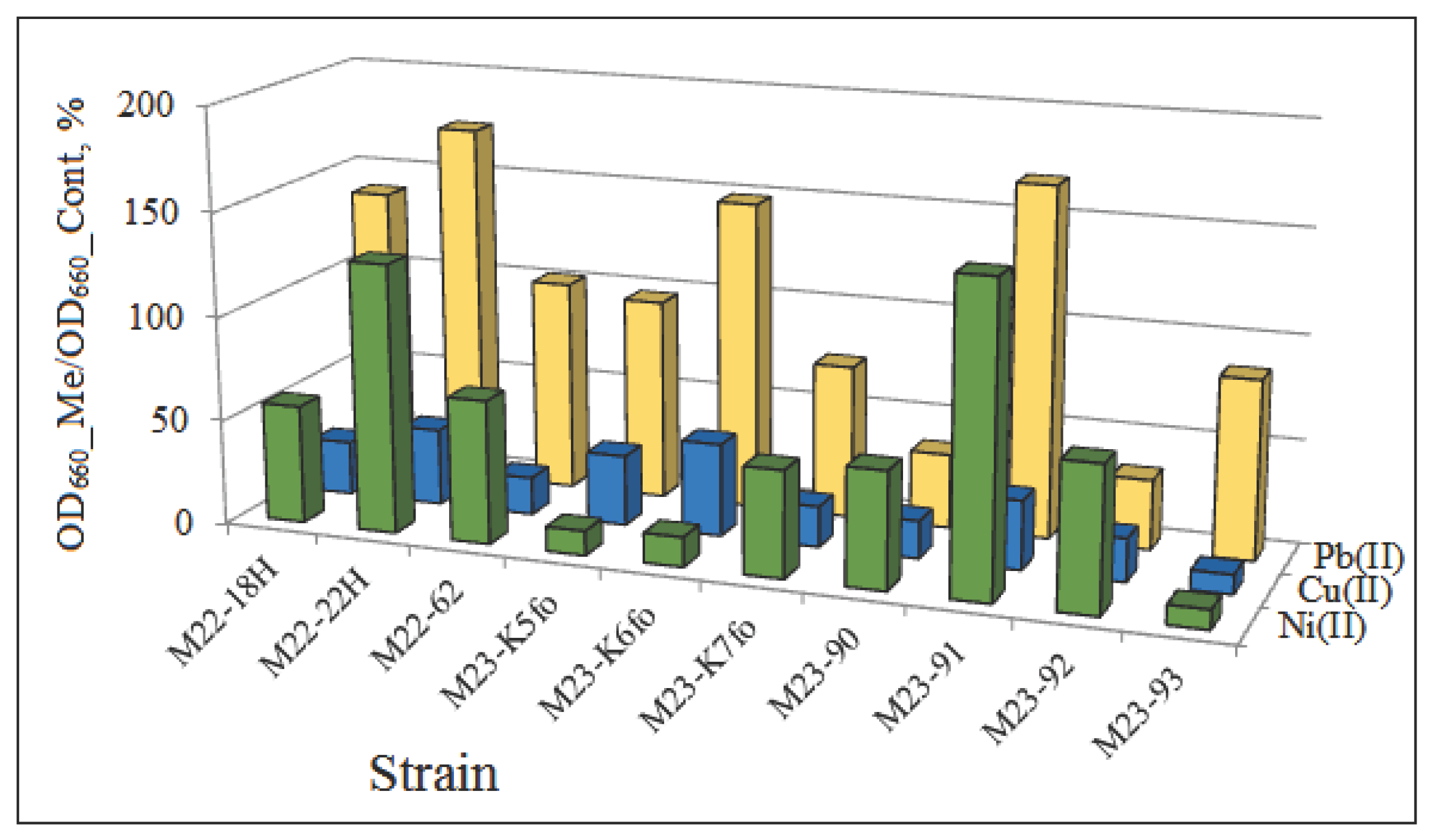

The resistance of the isolates to heavy metals decreased in the range Pb(II)>Ni(II)>Cu(II). The presence of NiCl

2·2H

2O stimulated the growth of strains M22–22H and M23–91, and Pb(NO

3)

2 – strains M22–18H, M22–22H, M23–K6fo, M23–91 compared with the control without heavy metals (

Figure 5). The results obtained are comparable with data from other researchers [

83,

84]. The studied microorganisms are adapted to inhabit soils polluted with heavy metals. These results indicate the adaptation of the isolated strains to the conditions of their habitat and their possible participation in the process of soil self-purification.

3.3. Culturable Fe(III)-Reducing Bacteria

Both aerobic and anaerobic processes are possible in the 0-20 cm soil layer. An analysis of the number and composition of communities revealed the presence of both aerobic hydrocarbon- and iron-oxidizing, as well as anaerobic or facultatively anaerobic bacteria capable of fermentation and reduction of metals. The processes of metal oxidation and reduction can occur in parallel in microzones with different oxygen contents [

85]. Bacteria involved in both the oxidation process and the reduction process in the iron cycle have been described [

86]. Bacteria capable of Fe

3+ reduction can also reduce other metals (Mn

4+, for example) and vice versa [

15,

87], therefore Fe

3+ citrate was chosen as a model compound. The poly-contamination of soils with petroleum products and heavy metals prompted us to check whether HC oxidation is possible in these microbial communities, coupled with the Fe

3+ reduction. A similar process has been shown for bacteria of the genera

Geobacter and

Rhizobium [

15,

24].

Stable enrichment cultures were obtained from M2 and M3 soil samples, which carried out the process of Fe

3+ reduction to Fe

2+, and oxidation of the alkane fraction (

Figure S4). Enrichment culture M2 used medium-chain alkanes to a greater extent, while culture M3 used medium- and long-chain alkanes. The low hydrocarbon biodegradation is probably due to the fact that the rate of anaerobic degradation of hydrocarbons is significantly lower than the aerobic HCs oxidation. Since many iron-reducing bacteria are able to grow aerobically, the resulting enrichment cultures were inoculated on plates with a solid nutrient medium, from which it was possible to isolate the FeRed2 and FeRed3 strains. The isolated strains were able to reduce Fe

3+, as well as grow aerobically on diesel fuel and crude oil (

Figure S5), and were identified as

Paenibacillus pseudetheri and P

aenibacillus nitricinens, respectively (

Table S2) [

88,

89].

Bacteria of the genus

Paenibacillus are able to grow on aromatic hydrocarbons and have previously been isolated from Arctic soils contaminated with petroleum products [

52,

90]. These bacteria are known for their ability to reduce and sorb heavy metals, form siderophores and form floccules, which allow them to be used for water purification from heavy metals [

91,

92,

93].

Paenibacillus spp. demonstrated high resistance to heavy metals (Cd) [

94]. Probably, the bacteria of the genus

Paenibacillus isolated from the studied soils are able to participate in the process of soil self-purification both in the aerobic and anaerobic zones, using anaerobic respiration for the degradation of hydrocarbons.

4. Conclusions

Remediation of long-standing complex soil pollutants in Polar Regions is an important and difficult task. This work shows that a multifunctional autochthonous microbial community capable of biodegradation of hydrocarbons, oxidation and reduction of metals inhabit the soils of Polar Regions with long-standing pollution by petroleum products and heavy metals. The total content of hydrocarbons and heavy metals influenced the composition of microbial communities. An increase in the content of petroleum products in the soil led to a significant increase in the bacteria of the phyla Pseudomonadota, Verrucomicrobiota, Cyanobacteriota, and Bacillota and to a decrease of the Acidobacteriota, Chloroflexota, Actinomycetota, Planctomycetota, Thermoproteota, Bacteroidota, and Candidatus Patescibacteria. The increase in the Pseudomonadota was due to Alphaproteobacteria (genera Acidiphilum, Acidisoma, Acidocella, and Bradyrhizobium) apparently adapted to the conditions of poor northern soils. Culturable bacteria capable of degrading hydrocarbons and oxidizing metals were isolated from the upper aerobic zone, while bacteria capable of reducing Fe3+ for growth on hydrocarbons were present in the anaerobic subsurface zone. Isolated pure cultures of bacteria of the genera Bacillus, Caballeronia, Cytobacillus, Paenibacillus, Paraburkholderia, Pseudomonas, and Rhodanobacter degraded petroleum n-alkanes, strains of the genus Pseudomonas oxidized Fe2+, and Paenibacillus spp. we capable of reducing Fe3+ to Fe2+, which allows them to participate in the process of soil self-purification. The isolated strains are resistant to the used concentrations of heavy metals; their toxicity decreased in the range Cu2+>Ni2+>Pb2+. The data obtained indicate the potential of autochthonous microorganisms for remediation of the studied contaminated soils.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1, Figure S1: The number of culturable microorganisms in soil samples in October 2022 (a) and August 2023 (b); Figure S2: Taxonomic classification of prokaryotes at the level of the Bacteria and Archaea domains in soil samples based on the high-throughput sequencing of 16S rRNA genes; Figure S3: Residual content of

n-alkanes in crude oil (in % relative to the content of

n-alkanes in the sterile control) degraded by

Pseudomonas hamedanensis M22-18H (a),

Pseudomonas yamanorum M22-22H (b),

Pseudomonas synxantha M22-62 (c),

Caballeronia sordidicola M23-90 (d),

Caballeronia udeis M23-92 (e),

Paraburkholderia domus M23-93 (f),

Pseudomonas frederiksbergensis M23-K5fo (g), and

Pseudomonas fluorescens M23-K6fo (h). The bacteria were incubated for 14 days at 15 °C; Figure S4: Residual content of

n-alkanes in diesel fuel (in % relative to the content of

n-alkanes in the sterile control) degraded by Fe

3+-reducing enrichment from M2 (a) and M3 (b) soil samples on the medium with Fe

3+ citrate and diesel fuel. The enrichments were incubated for 60 days at 15 °C; Figure S5: Residual content of

n-alkanes in crude oil (in % relative to the content of

n-alkanes in the sterile control) degraded by strain

Paenibacillus pseudetheri FeRed2 (a) and

Paenibacillus nitricinens FeRed3 (b). The cultures were incubated aerobically with sterile crude oil for 21 days at 23 °C; Table S1: Diversity indices in V3–V4 libraries of prokaryotic 16S rRNA gene fragments from the studied soil samples; Table S2: Taxonomic affiliation of the isolated strains based on the analysis of 16S rRNA genes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.S., M.V.K., and V.A.M.; data curation, E.M.S., T.L.B., D.S.S.; formal analysis, D.S.S.; funding acquisition, M.V.K.; investigation, E.M.S., T.L.B., D.S.S., M.V.K., and V.A.M.; project administration, V.A.M. and M.V.K.; software, D.S.S.; supervision, M.V.K.; validation, E.M.S. and D.S.S.; visualization, E.M.S., D.S.S., M.V.K., and T.N.N.; writing—original draft, E.M.S.; writing—review and editing, E.M.S. and T.N.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The fieldwork and bioinformatics analyses were supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (project FSSF-2024-0023); the publication and funding acquisition were supported by the RUDN University Scientific Projects Grant System (Project 202414-2-000).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The 16S rRNA gene sequences of isolated strains were deposited into GenBank under accession nos: PX457869, PX457873, PX464108, PX457728, PX462097, PX462100, PX462107, PX462110, PX457785, PX463341, PX463725–PX463727, PX457871, PX457722, PX457868, PX460839, PX457726, and PX463338. The raw data generated from 16S rRNA gene profiling of M1–M4 microbial communities have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and are available via the BioProject PRJNA1346952.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of Pasvik State Nature Reserve and head of Pasvik State Nature Reserve, Natalia Polikarpova, for assistance in fieldwork.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Yergeau, E.; Sanschagrin, S.; Beaumier, D.; Greer, C.W. Metagenomic analysis of the bioremediation of diesel-contaminated Canadian high arctic soils. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Ye, X.; Chen, K.; Li, W.; Yuan, J; Jiang, X. Bacterial community shift and hydrocarbon transformation during bioremediation of short-term petroleum-contaminated soil. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 223, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, M.; Barabadi, A.; Barabady, J. Bioremediation treatment of hydrocarbon–contaminated Arctic soils: influencing parameters. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2014, 21, 11250–11265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, H.S.; Zakaria, N.N.; Zulkharnain, A.; Sabri, S.; Gomez–Fuentes, C.; Ahmad, S.A. Bibliometric analysis of hydrocarbon bioremediation in cold regions and a review on enhanced soil bioremediation. Biology 2021, 10, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Chandran, P. Microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbon contaminants: an overview. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2011, 2011, 941810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 6. Kumar, V.; Kumar, M.; Prasad, R. (Eds.) Microbial action on hydrocarbons. Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2018, 663 p. [CrossRef]

- Margesin, R; Schinner, F. Biodegradation of diesel oil by cold-adapted microorganisms in presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate. Chemosphere. 1999, 38, 3463–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivkina, E.M.; Friedmann, E.I.; Mckay, C.P.; Gilichinsky, D.A. Metabolic activity of permafrost bacteria below the freezing point. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 3230–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Amico, S.; Collins, T.; Marx, J.C.; Feller, G.; Gerday, C. Psychrophilic microorganisms: challenges for life. EMBO Rep. 2006, 4, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, E.M.; Tourova, T.P.; Babich, T.L.; Logvinova, E.Y.; Sokolova, D.S.; Loiko, N.G.; Myazin, V.A.; Korneykova, M.V.; Mardanov, A.V.; Nazina, T.N. Crude oil degradation in temperatures below the freezing point by bacteria from hydrocarbon-contaminated arctic soils and the genome analysis of Sphingomonas sp. AR_OL41. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowik, A.; Wyszkowska, J.; Wyszkowski, M. Resistance of aerobic microorganisms and soil enzyme response to soil contamination with Ekodiesel Ultra fuel. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017, 24, 31–24346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzinger, P.B.; Alexander, M. Effect of aging of chemicals in soil on their biodegradability and extractability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1995, 29, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Lu, X.; Suna, Q.; Zhua, W. Aging effect of petroleum hydrocarbons in soil under different attenuation conditions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 149, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aislabie, J.M.; Balks, M.R.; Foght, J.M.; Waterhouse, E.J. Hydrocarbon spills on Antarctic soils: effects and management. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovley, D.R. Dissimilatory metal reduction. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1993, 47, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobby, R.; Desai, N. In: Biodegradation and bioremediation. Environmental Science and Engineering; Kumar, P.; Gurjar, B.R.; Govil, J.N., Eds. Studium Press (India), 2017, 1, chapter 8, 201–220.

- Safonov, A.V.; Babich, T.L.; Sokolova, D.S.; Grouzdev, D.S.; Tourova, T.P.; Poltaraus, A.B.; Zakharova, E.V.; Merkel, A.Y.; Novikov, A.P.; Nazina, T.N. Microbial community and in situ bioremediation of groundwater by nitrate removal in the zone of a radioactive waste surface repository. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, L.; Tiwari, J.; Bauddh, K.; Ma, Y. Recent developments in microbe-plant-based bioremediation for tackling heavy metal-polluted soils. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 731723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Alkasem, M.I.; Hassan, N.H.; Abo Elsoud, M.M. Microbial bioremediation as a tool for the removal of heavy metals. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2023, 47, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Maleva, M.; Bruno, L.B.; Rajkumar, M. Synergistic effect of ACC deaminase producing Pseudomonas sp. TR15a and siderophore producing Bacillus aerophilus TR15c for enhanced growth and copper accumulation in Helianthus annuus L. Chemosphere 2021, 276, 130038. [CrossRef]

- Tebo, B.M.; Obraztsova, A.Y. Sulfate-reducing bacterium grows with Cr (VI), U (VI), Mn (IV), and Fe (III) as electron acceptors. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1998, 162, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, J.R.; Sole, V.A.; Van Praagh, C.V.G.; Lovley, D.R. Direct and Fe (II)-mediated reduction of technetium by Fe (III)-reducing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 3743–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccavo, F.J.; Lonergan, D.J.; Lovley, D.R.; Davis, M.; Stolz, J.F.; McInerney, M.J. Geobacter sulfurreducens sp. nov., a hydrogen- and acetate-oxidizing dissimilatory metal-reducing microorganism. Appl. Environ Microbiol. 1994, 60, 3752–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, B.; Sarkar, A.; Joshi, S.; Chatterjee, A.; Kazy, S.K.; Maiti, M.K.; Satyanarayana, T.; Sar, P. An arsenate-reducing and alkane-metabolizing novel bacterium, Rhizobium arsenicireducens sp. nov., isolated from arsenic-rich groundwater. Arch. Microbiol. 2017, 199, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandrin, T.R.; Maier, R.M. Impact of metals on the biodegradation of organic pollutants. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003, 111, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, C.A.; Yang, X.; Clark, I.M.; Zhao, F.J.; Hirsch, P.R.; McGrath, S.P. Relative impact of soil, metal source and metal concentration on bacterial community structure and community tolerance. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hu, X.; Cao, Y.; Pang, W.; Huang, J.; Guo, P.; Huang, L. Biodegradation of phenanthrene and heavy metal removal by acid-tolerant Burkholderia fungorum FM–2. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Moghny, T.; Mohamed, R.S.A.; El–Sayed, E.; Mohammed Aly, S.; Snousy, M.G. Effect of soil texture on remediation of hydrocarbons–contaminated soil at El–Minia District, Upper Egypt. ISRN Chemical Engineering, 2012, 2012, 406598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evdokimova, G.; Masloboev, V.; Mozgova, N.; Myazin, V.; Fokina, N. Bioremediation of oil-polluted cultivated soils in the Euro-Arctic region. J. Environ. Science and Engineering. 2012, 1(9A), 1130–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Dell'Anno, F.; Brunet, C.; van Zyl, L.J.; Trindade, M.; Golyshin, P.N.; Dell'Anno, A.; Ianora, A.; Sansone, C. Degradation of hydrocarbons and heavy metal reduction by marine bacteria in highly contaminated sediments. Microorganisms 2020, 11, 8–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamet, S.D.; Jimmo, A.; Conway, A.; Teymurazyan, A.; Talebitaher, A.; Papandreou, Z.; Chang, Y.F.; Shannon, W.; Peak, D.; Siciliano, S.D. Soil buffering capacity can be used to optimize biostimulation of psychrotrophic hydrocarbon remediation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 20, 55–9864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeneli, A.; Kastanaki, E.; Simantiraki, F.; Gidarakos, E. Monitoring the biodegradation of TPH and PAHs in refinery solid waste by biostimulation and bioaugmentation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorovtsov, A.; Demin, K.; Sushkova, S.; Minkina, T.; Grigoryeva, T.; Dudnikova, T.; Barbashev, A.; Semenkov, I.; Romanova, V.; Laikov, A.; Rajput, V.; Kocharovskaya, Y. The effect of combined pollution by PAHs and heavy metals on the topsoil microbial communities of Spolic Technosols of the lake Atamanskoe, Southern Russia. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2022, 44, 1299–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myazin, V.A.; Korneykova, M.V.; Chaporgina, A.A.; Fokina, N.V.; Vasilyeva, G.K. The effectiveness of biostimulation, bioaugmentation and sorption-biological treatment of soil contaminated with petroleum products in the Russian Subarctic. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reasoner, D.J.; Geldreich, E.E. A new medium for the enumeration and subculture of bacteria from potable water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharova, Iu.R.; Parfenova, V.V. A method for cultivation of microorganisms oxidizing iron and manganese in bottom sediments of Lake Baikal. Biology Bulletin. 2007, 34, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovley, D.R. , Phillips, E.J.P. Organic matter mineralization with reduction of ferric iron in anaerobic sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1986, 51, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfennig, N.; Lippert, K.D. Über das vitamin B12 – Bedürfnis phototropher Schweferelbakterien. Arch. Microbiol. 1966, 55, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzenkov, I.A.; Milekhina, E.I.; Gotoeva, M.T.; Rozanova, E.P.; Belyaev, S.S. The properties of hydrocarbon oxidizing bacteria isolated from the oilfields of Tatarstan, Western Siberia, and Vietnam. Microbiology (Moscow) 2006, 75, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.J. sequencing. In Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics; Stackebrandt, E., Goodfellow, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, B.; Rime, T.; Phillips, M.; Stierli, B.; Hajdas, I.; Widmer, F.; Hartmann, M. Microbial diversity in European alpine permafrost and active layers. FEMS Microbol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadnikov, V.V.; Ravin, N.V.; Sokolova, D.S.; Semenova, E.M.; Bidzhieva, S.K.; Beletsky, A.V.; Ershov, A.P.; Babich, T.L.; Khisametdinov, M.R.; Mardanov, A.V.; Nazina, T.N. Metagenomic and culture-based analyses of microbial communities from petroleum reservoirs with high-salinity formation water, and their biotechnological potential. Biology 2023, 12, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods. 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2460–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rognes, T.; Flouri, T.; Nichols, B.; Quince, C.; Mahé, F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsalu, T.; Vilo, J. ClustVis: a web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W566–W570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. Past: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Garousin, H.; Pourbabaee, A.A.; Alikhani, H.A.; Yazdanfar, N. A combinational strategy mitigated old–aged petroleum contaminants: ineffectiveness of biostimulation as a bioremediation technique. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 642215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernov, T.; Tkhakakhova, A.K.; Ivanova, E.A.; Kutovaya, O.V.; Turusov, V.I. Seasonal dynamics of the microbiome of chernozems of the long–term agrochemical experiment in Kamennaya Steppe. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2015, 48, 1349–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namsaraev, Z.; Bobrik, A.; Kozlova, A.; Krylova, A.; Rudenko, A.; Mitina, A.; Saburov, A.; Patrushev, M.; Karnachuk, O.; Toshchakov, S. Carbon emission and biodiversity of Arctic soil microbial communities of the Novaya Zemlya and Franz Josef Land Archipelagos. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korneykova, M.V.; Myazin, V.A.; Fokina, N.V.; Chaporgina, A.A.; Nikitin, D.A.; Dolgikh, A.V. Structure of microbial communities and biological activity in tundra soils of the Euro-Arctic region (Rybachy peninsula, Russia). Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, E.M.; Babich, T.L.; Sokolova, D.S.; Dobriansky, A.S.; Korzun, A.V.; Kryukov, D.R. Microbial diversity of hydrocarbon-contaminated soils of the Franz Josef land Archipelago. Microbiology 2021, 90, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, A.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Simpson, R.T.; Moore, J.C. Soil bacterial community composition altered by increased nutrient availability in Arctic tundra soils. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malard, L.A.; Pearce, D.A. Microbial diversity and biogeography in Arctic soils. Env. Microbiol. Rep. 2018, 10, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, F.; Lin, Y.; Chen, W.; Wei, G. Temporal dynamics of microbial communities in microcosms in response to pollutants. Mol. Ecol. 2017, 26, 923–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Juottonen, H.; Siivonen, P.; Quesada, C.L.; Tuomi, P.; Pulkkinen, P.; Yrjälä, K. Spatial patterns of microbial diversity and activity in an aged creosote-contaminated site. ISME J. 2014, 8, 2131–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, L.; Schultz, A.; Beilen, J.; Luz, A.; Pellizari, V.; Labbe´, D.; Greer, C.W. Prevalence of alkane monooxygenase genes in Arctic and Antarctic hydrocarbon-contaminated and pristine soils. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2002, 41, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margesin, R.; Labbe, D.; Schinner, F.; Greer, C.; Whyte, L. Characterization of hydrocarbon–degrading microbial populations in contaminated and pristine alpine soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 3085–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulichevskaya, I.S.; Suzina, N.E.; Liesack, W.; Dedysh, S.N. Bryobacter aggregatus gen. nov., sp. nov., a peat-inhabiting, aerobic chemo-organotroph from subdivision 3 of the Acidobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.R.; Männistö, M.K.; Bromberg, Y.; Häggblom, M.M. Comparative genomic and physiological analysis provides insights into the role of Acidobacteria in organic carbon utilization in Arctic tundra soils. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 82, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Chaves, M.G.; Silva, G.G.Z.; Rossetto, R.; Edwards, R.A.; Tsai, S.M.; Navarrete, A.A. Acidobacteria subgroups and their metabolic potential for carbon degradation in sugarcane soil amended with vinasse and nitrogen fertilizers. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barns, S.M.; Cain, E.C.; Sommerville, L.; Kuske, C.R. Acidobacteria phylum sequences in uranium–contaminated subsurface sediments greatly expand the known diversity within the phylum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 3113–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałązka, A.; Grządziel, J.; Gałązka, R.; Ukalska–Jaruga, A.; Strzelecka, J.; Smreczak, B. Genetic and functional diversity of bacterial microbiome in soils with long term impacts of petroleum hydrocarbons. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belova, S.E.; Pankratov, T.A.; Detkova, E.N.; Kaparullina, E.N.; Dedysh, S.N. Acidisoma tundrae gen. nov., sp. nov. and Acidisoma sibiricum sp. nov., two acidophilic, psychrotolerant members of the Alphaproteobacteria from acidic northern wetlands. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 2283–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Meng, D.; Liu, X.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Jiang, Z.; Zhong, S.; Jiang, C.; Yin, H. Insights into the metabolism and evolution of the genus Acidiphilium, a typical acidophile in acid mine drainage. mSystems 2020, 5, e00867–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.M.; Hedrich, S.; Johnson, D.B. Acidocella aromatica sp. nov.: an acidophilic heterotrophic alphaproteobacterium with unusual phenotypic traits. Extremophiles 2013, 17, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Hayat, S.; Ahmad, A.; Inam, A.; Samiullah. Metal and antibiotic resistance traits in Bradyrhizobium sp. (cajanus) isolated from soil receiving oil refinery wastewater. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2001, 17, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włodarczyk, A.; Lirski, M.; Fogtman, A.; Koblowska, M.; Bidziński, G.; Matlakowska, R. The oxidative metabolism of fossil hydrocarbons and sulfide minerals by the lithobiontic microbial community inhabiting deep subterrestrial Kupferschiefer Black Shale. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manucharova, N.A.; Bolshakova, M.A.; Babich, T.L.; Tourova, T.P.; Semenova, E.M.; Yanovich, A.S.; Poltaraus, A.B.; Stepanov, A.L. , Nazina T.N. Microbial degraders of petroleum and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from sod-podzolic soil. Microbiology 2021, 90, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banasiewicz, J.; Gumowska, A.; Hołubek, A.; Orzechowski, S. Adaptations of the genus Bradyrhizobium to selected elements, heavy metals and pesticides present in the soil environment. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Incau, E.; Ouvrard, S.; Devers–Lamrani, M.; Jeandel, C.; Mohamed, C.E.; Henry, S. Biodegradation of a complex hydrocarbon mixture and biosurfactant production by Burkholderia thailandensis E264 and an adapted microbial consortium. Biodegradation 2024, 35, 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulschen, A.A.; Bendia, A.G.; Fricker, A.D.; Pellizari, V.H.; Galante, D.; Rodrigues, F. Isolation of uncultured bacteria from Antarctica using long incubation periods and low nutritional media. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 14, 8–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korshunova, T.Y.; Bakaeva, M.D.; Kuzina, E.V.; Rafikova, G.F.; Chetverikov, S.P.; Chetverikova, D.V.; Loginov, O.N. Role of bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas in the sustainable development of agricultural systems and environmental protection (Review). Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2021, 57, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aislabie, J.; Saul, D.J.; Foght, J.M. Bioremediation of hydrocarbon–contaminated polar soils. Extremophiles 2006, 10, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobritsa, A.; Samadpour, M. Reclassification of Burkholderia insecticola as Caballeronia insecticola comb. nov. and reliability of conserved signature indels as molecular synapomorphies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 2057–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, I.; Moriuchi, R.; Dohra, H.; Kimbara, K.; Ogawa, N.; Shintani, M. Isolation and genomic analysis of 3-chlorobenzoate-degrading bacteria from soil. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ou, Y.; Wang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, W.; Peng, J.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Z.; Ye, J. Responses of a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon–degrading bacterium, Paraburkholderia fungorum JT–M8, to Cd (II) under P–limited oligotrophic conditions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weon, H.-Y.; Kim, B.-Y.; Hong, S.-B.; Jeon, Y.-A.; Kwon, S.-W.; Go, S.; Koo, B.-S. Rhodanobacter ginsengisoli sp. nov. and Rhodanobacter terrae sp. nov., isolated from soil cultivated with Korean ginseng. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 2810–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemme, C.L.; Deng, Y.; Gentry, T.J.; Fields, M.W.; Wu, L.; Barua, S.; Barry, K.; Tringe, S.G.; Watson, D.B.; He, Z.; Hazen, T.C.; Tiedje, J.M.; Rubin, E.M.; Zhou, J. Metagenomic insights into evolution of a heavy metal–contaminated groundwater microbial community. ISME Journal, 2010, 4, 660–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, О.; Green, S.J.; Singh, P.; Jasrotia, P.; Kostka, J.E. Stress-related ecophysiology of members of the genus Rhodanobacter isolated from a mixed waste contaminated subsurface. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2021, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Yin, N.; Zhan, X. Surfactant-enhanced biodegradation of crude oil by mixed bacterial consortium in contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 14437–14446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melekhina, E.N.; Belykh, E.S.; Markarova, M.Yu.; Taskaeva, A.A.; Rasova, E.E.; Baturina, O.A.; Kabilov, M.R.; Velegzhaninov, I.O. Soil microbiota and microarthropod communities in oil contaminated sites in the European Subarctic. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Pan, C.; Xiao, A.; Yang, X.; Zhang, G. Isolation, identification, and environmental adaptability of heavy-metal-resistant bacteria from ramie rhizosphere soil around mine refinery. 3 Biotech. 2017, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethu, C.S.; Mujeeb Rahiman, K.M.; Saramma, A.V.; Mohamed Hatha, A.A. Heavy metal resistance in Gram–negative bacteria isolated from Kongsfjord, Arctic. Can. J. Microbiol. 2015, 61, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Liu, H.; Zhang, P.; Ma, J.; Jin, M. Co-response of Fe-reducing/oxidizing bacteria and Fe species to the dynamic redox cycles of natural sediment. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 815, 152953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavarzina, D.G.; Gavrilov, S.N.; Chistyakova, N.I.; Antonova, A.V.; Gracheva, M.A.; Merkel, A.Y.; Perevalova, A.A.; Chernov, M.S.; Zhilina, T.N.; Bychkov, A.Y.; Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A. Syntrophic growth of alkaliphilic anaerobes controlled by ferric and ferrous minerals transformation coupled to acetogenesis. ISME J. 2020, 14, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovley, D.R.; Giovannoni, S.J.; White, D.C.; Champine, J.E.; Phillips, E.J.; Gorby, Y.A.; Goodwin, S. Geobacter metallireducens gen. nov. sp. nov., a microorganism capable of coupling the complete oxidation of organic compounds to the reduction of iron and other metals. Arch. Microbiol. 1993, 159, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kämpfer, P.; Lipski, A.; McInroy, J.A.; Clermont, D.; Lamothe, L.; Glaeser, S.P. Criscuolo, A. Paenibacillus auburnensis sp. nov. and Paenibacillus pseudetheri sp. nov., isolated from the rhizosphere of Zea mays. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2023, 73, 005808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra-Tralma, D.; Gaete, A.; Merino-Guzmán, C.; Parada-Ibáñez, M.; Nájera-de Ferrari, F.; Jofré-Fernández, I. Functional and genomic evidence of L-arginine-dependent bacterial nitric oxide synthase activity in Paenibacillus nitricinens sp. nov. Biology (Basel) 2025, 14, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daane, L.L.; Harjono, I.; Barns, S.M.; Launen, L.A.; Palleron, N.J.; Häggblom, M.M. PAH-degradation by Paenibacillus spp. and description of Paenibacillus naphthalenovorans sp. nov., a naphthalene-degrading bacterium from the rhizosphere of salt marsh plants. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B.; Cao, B.; McLean, J.S.; Ica, T.; Dohnalkova, A.; Istanbullu, O.; Paksoy, A.; Fredrickson, J.K.; Beyenal, H. Fe(III) reduction and U(VI) immobilization by Paenibacillus sp. strain 300A, isolated from Hanford 300A subsurface sediments. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 8001–8009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, O.; Lu, C.; Liu, A.; Zhu, L.; Wang, P.M.; Qian, C.D.; Jiang, X.H.; Wu, X.C. Optimization and characterization of polysaccharide-based bioflocculant produced by Paenibacillus elgii B69 and its application in wastewater treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 134, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, E.N.; MacDonald, J.; Liu, L.; Richman, A.; Yuan, Z.C. Current knowledge and perspectives of Paenibacillus: a review. Microb. Cell. Fact. 2016, 15, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Liao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, N.; Xie, X.; Fan, Q. Cadmium resistance, microbial biosorptive performance and mechanisms of a novel biocontrol bacterium Paenibacillus sp. LYX–1. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 68692–68706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).