3.1. Changes in CO2 and CH4 Column Concentrations in Hefei Region

This study reveals significant temporal variations in the column-averaged concentrations of carbon dioxide (XCO₂) and methane (XCH₄) over the Hefei region. Analysis of ground-based and satellite observations from 2009 to 2020 indicates a clear upward trend in both gases.

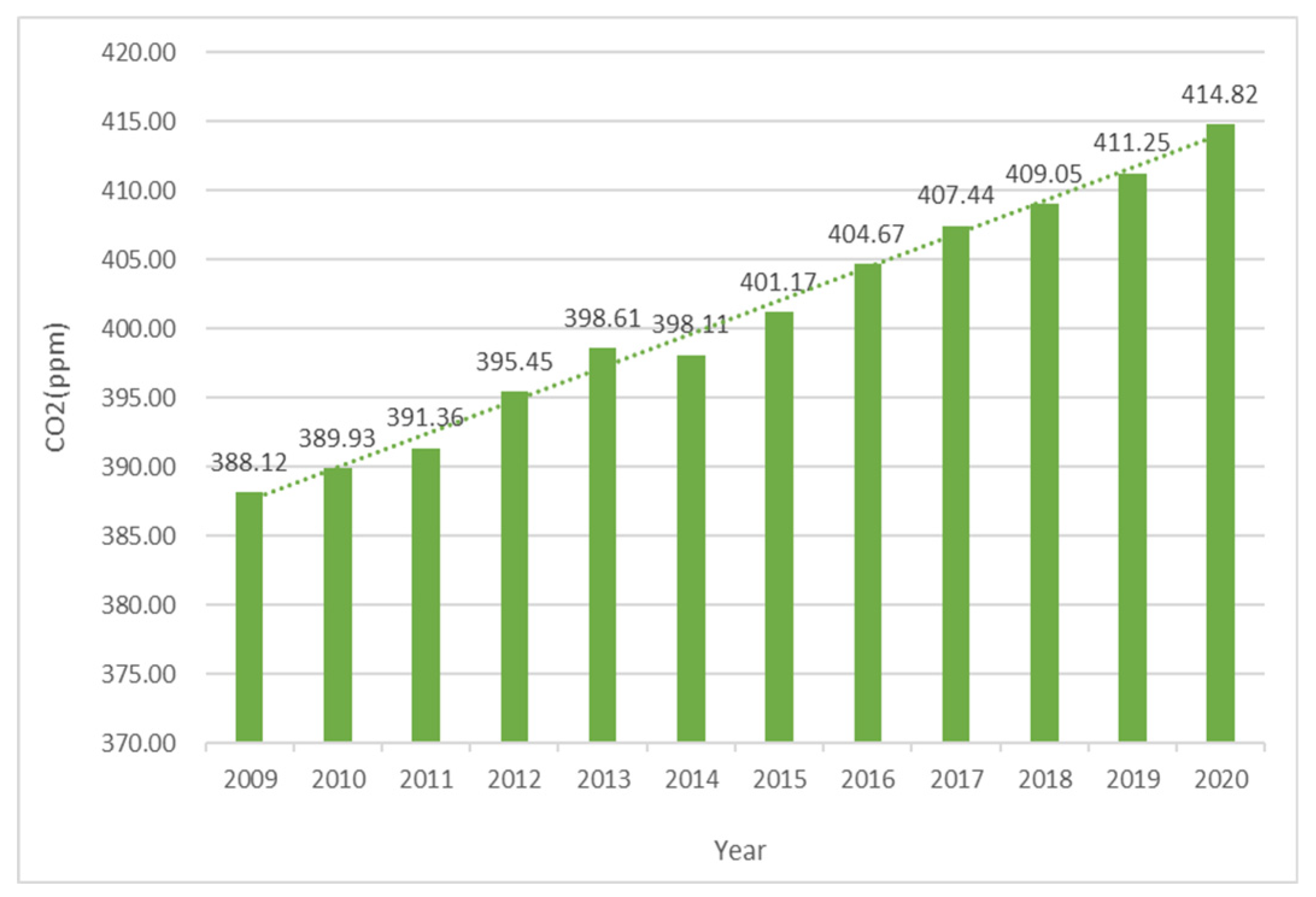

Figure 1 displays the annual average changes in CO

2 concentrations in Hefei from 2009 to 2020. Overall, CO

2 concentrations showed an upward trend during this period, with a slight decrease only in 2014 and steady increases in all other years. Specifically, from 2009 to 2020, CO

2 concentrations rose from 388.12ppm to 414.82ppm, representing a net increase of 26.70ppm and an annual growth rate of 2.43ppm/year.

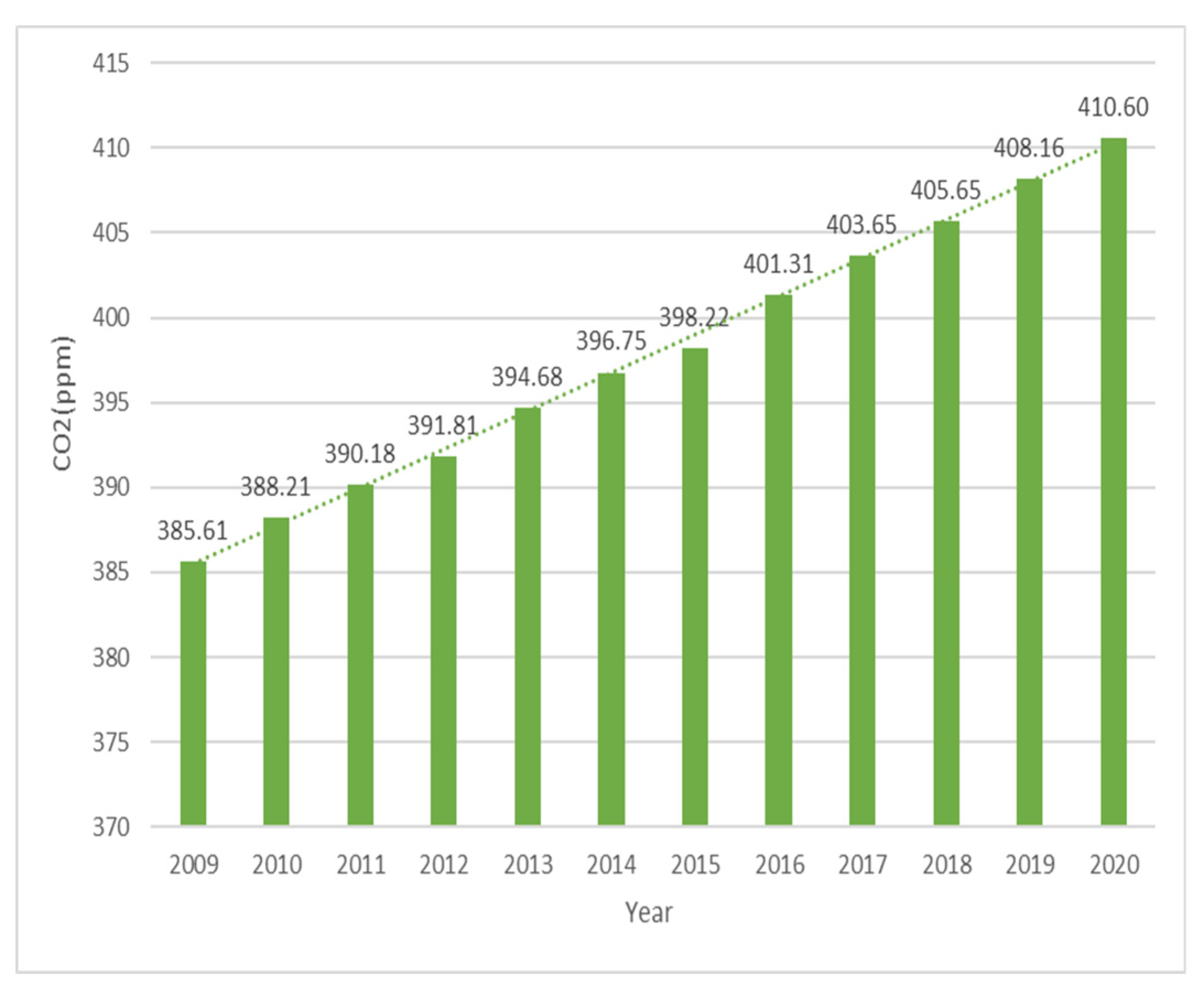

When comparing

Figure 1 with

Figure 2, it is evident that the annual growth rate of CO

2 concentrations in Hefei is higher than the global average. This discrepancy may be attributed to the inclusion of sparsely populated areas in the global data, which tends to lower the overall figure. In contrast, Hefei, as a densely populated city, naturally reports higher CO

2 concentrations. However, it is noteworthy that Hefei's CO

2 concentration in 2020 was approximately 414.82ppm, which is quite close to the global average of 410.60ppm. This similarity further confirms the global nature of CO

2 concentration increases. From a broader perspective, the impact of global climate change is also evident. According to the “Global Climate Change Indicators Report” the human-induced warming over the past decade (2014-2023) has risen to 1.19℃, higher than the 1.14℃ of the previous decade2. This data not only echoes the upward trend in CO

2 concentrations but also reminds us once again of the severity of global climate change.

Methane emissions and its contribution to global warming are second only to carbon dioxide. Globally, methane emissions are growing rapidly, and since the Industrial Revolution, human-induced methane emissions have contributed about a quarter to global warming. The anthropogenic sources of methane are widespread, including coal mining, oil and gas leaks, rice cultivation, ruminant digestion, animal manure, fuel combustion, landfill, and wastewater treatment. Among them, agriculture is the primary source of methane, with 32% of agricultural methane emissions coming from ruminant digestion and 8% from rice cultivation. Hefei has a total cultivated area of 486,300 hectares, of which 414,100 hectares are paddy fields, accounting for 85.15%.

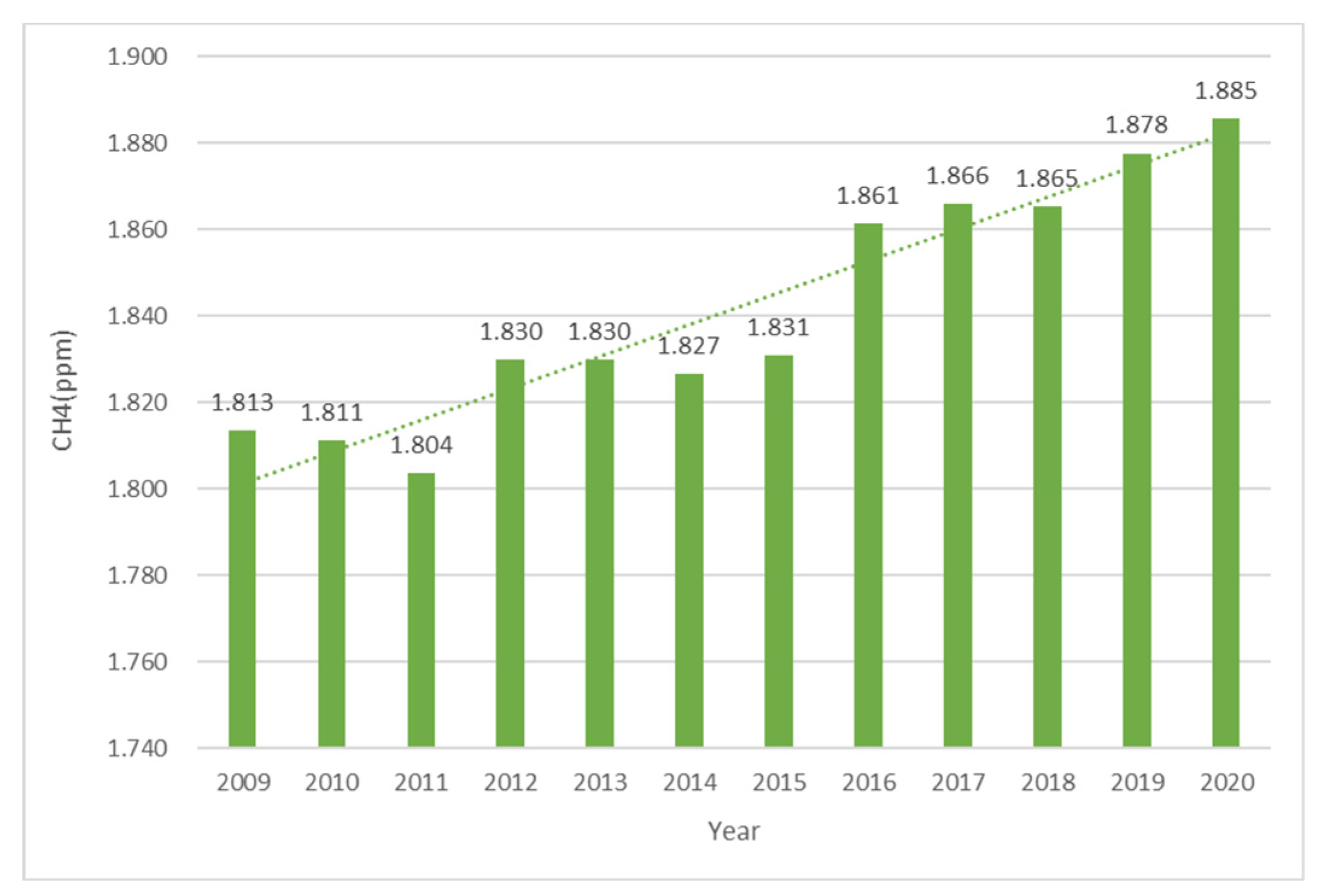

Figure 3 visually presents the trend of CH

4 concentration from 2009 to 2020. During this period, the overall CH

4 concentration showed an upward trend, but the growth process was unstable. Specifically, from 2009 to 2011, the CH

4 concentration decreased by a total of 9 ppb. However, in 2012, the concentration suddenly increased by 26 ppb, and although it stabilized afterwards, it still exhibited a downward trend. By 2016, the CH

4 concentration rose significantly again, reaching 30 ppb. Over these 11 years, the net increase in CH

4 concentration was 72 ppb, with an annual growth rate of approximately 6.545 ppb/year. The growth process of CH

4 concentration was quite intense, indicating that besides natural sources, fluctuations in anthropogenic sources had a significant impact on CH

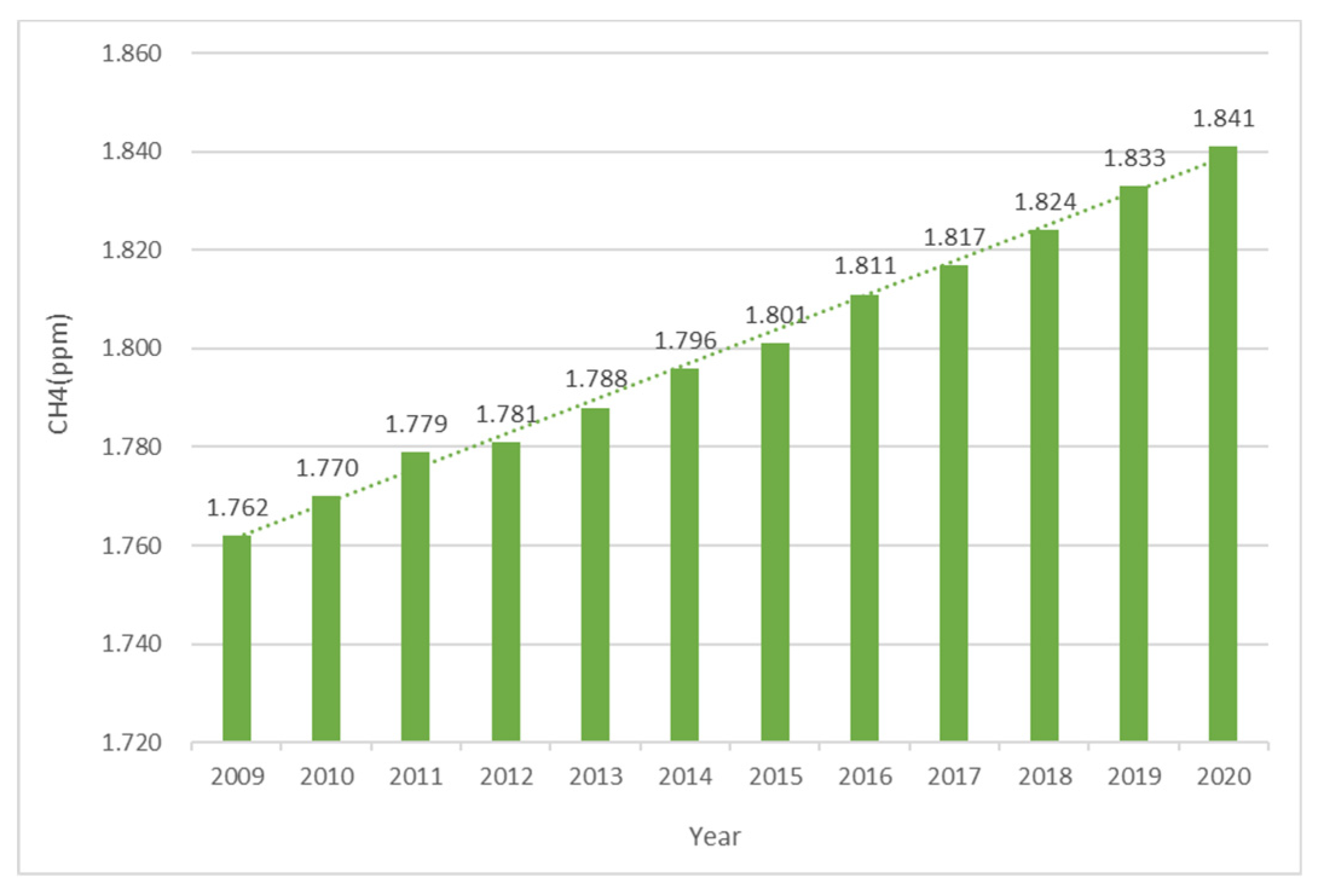

4 concentrations. Compared with global CH

4 data, the annual growth rate in Hefei was relatively low. However, in 2009, the CH

4 concentration in Hefei was 51 ppb higher than the global figure. This indirectly suggests that CH

4 concentrations tend to be higher in densely populated areas. Looking at the data for 2020, the CH

4 concentration in Hefei was 1.885 ppm, slightly higher than the global average for that year, but the difference was not significant. Overall, although the data from Hefei and the global average were generally similar, the fluctuations in Hefei's data were greater. This was mainly attributed to the large population and the influence of human activities.

Figure 3.

The trend of CH4 column concentration in Hefei from 2009 to 2020.

Figure 3.

The trend of CH4 column concentration in Hefei from 2009 to 2020.

Figure 4.

The trend of global CH4 concentration from 2009 to 2020.

Figure 4.

The trend of global CH4 concentration from 2009 to 2020.

3.2. The Seasonal Variation of Column Concentrations of Greenhouse Gases CO2 and CH4

The concentration of greenhouse gases (such as carbon dioxide, methane, etc.) in the atmosphere is not constant. They are subject to variations influenced by multiple natural and human factors. Seasonal changes are one of the important influencing factors. Due to seasonal climate variations (such as temperature, precipitation, wind direction, etc.) and changes in human activities (such as fossil fuel combustion, agricultural production, etc.), the concentration of greenhouse gases may exhibit seasonal fluctuations. The impact of seasonal changes on the greenhouse effect is mainly reflected in variations in greenhouse gas concentration and distribution, changes in Earth's surface temperature, and the resulting alterations in climate patterns.

Firstly, seasonal changes affect the concentration and distribution of greenhouse gases. Human activities (such as fossil fuel combustion) and natural processes (such as plant growth and decay) differ across seasons, leading to variations in the emission and absorption rates of greenhouse gases. For example, during winter, the increased demand for heating may result in a rise in the use of fossil fuels like coal and oil, subsequently increasing emissions of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide. These seasonal changes impact the total amount and distribution of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, thereby influencing the greenhouse effect. Secondly, seasonal changes lead to variations in Earth's surface temperature, which is also a significant manifestation of the greenhouse effect. Due to the periodic changes in Earth's rotation and revolution, the angle and intensity of solar radiation reaching Earth vary with seasons, causing changes in Earth's surface temperature. These temperature variations affect the absorption and radiation characteristics of greenhouse gases like water vapor and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, further regulating the greenhouse effect. Lastly, seasonal changes also trigger alterations in climate patterns. The global warming caused by the greenhouse effect exacerbates the instability of the climate system, increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events (such as heatwaves, droughts, heavy rainfall, etc.). These extreme weather events are often closely related to seasonal changes; for instance, high temperatures and heatwaves are more likely to occur in summer, while cold waves and snowfall are more prevalent in winter. These changes in climate patterns not only affect human production and life but also have profound impacts on ecosystems and the natural environment. Specifically, during winter, the increased demand for heating may lead to a rise in the use of fossil fuels like coal and oil, resulting in higher emissions of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide. Additionally, the atmospheric structure is relatively stable in winter, which is not conducive to the dispersion of pollutants, potentially leading to an increase in greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. Conversely, in summer, the higher temperatures make the atmospheric structure relatively unstable, favoring the dispersion of pollutants. However, these seasonal changes are not absolute, as greenhouse gas concentrations are also influenced and diluted by factors such as global climate change, the intensity of human activities, geographical location, and others, which may result in relatively lower concentrations of greenhouse gases.

Hefei's climate is classified as a subtropical humid monsoon climate, with distinct seasons, each possessing its unique climatic characteristics. For instance, spring is characterized by heavy rainfall, summer by intense heat, autumn by cool temperatures, and winter by cold weather. These seasonal variations not only influence weather patterns but also have profound impacts on the local ecology, agriculture, and residents' lives. In this paper, the data from March to May is considered as spring, June to August as summer, September to November as autumn, and December to February as winter.

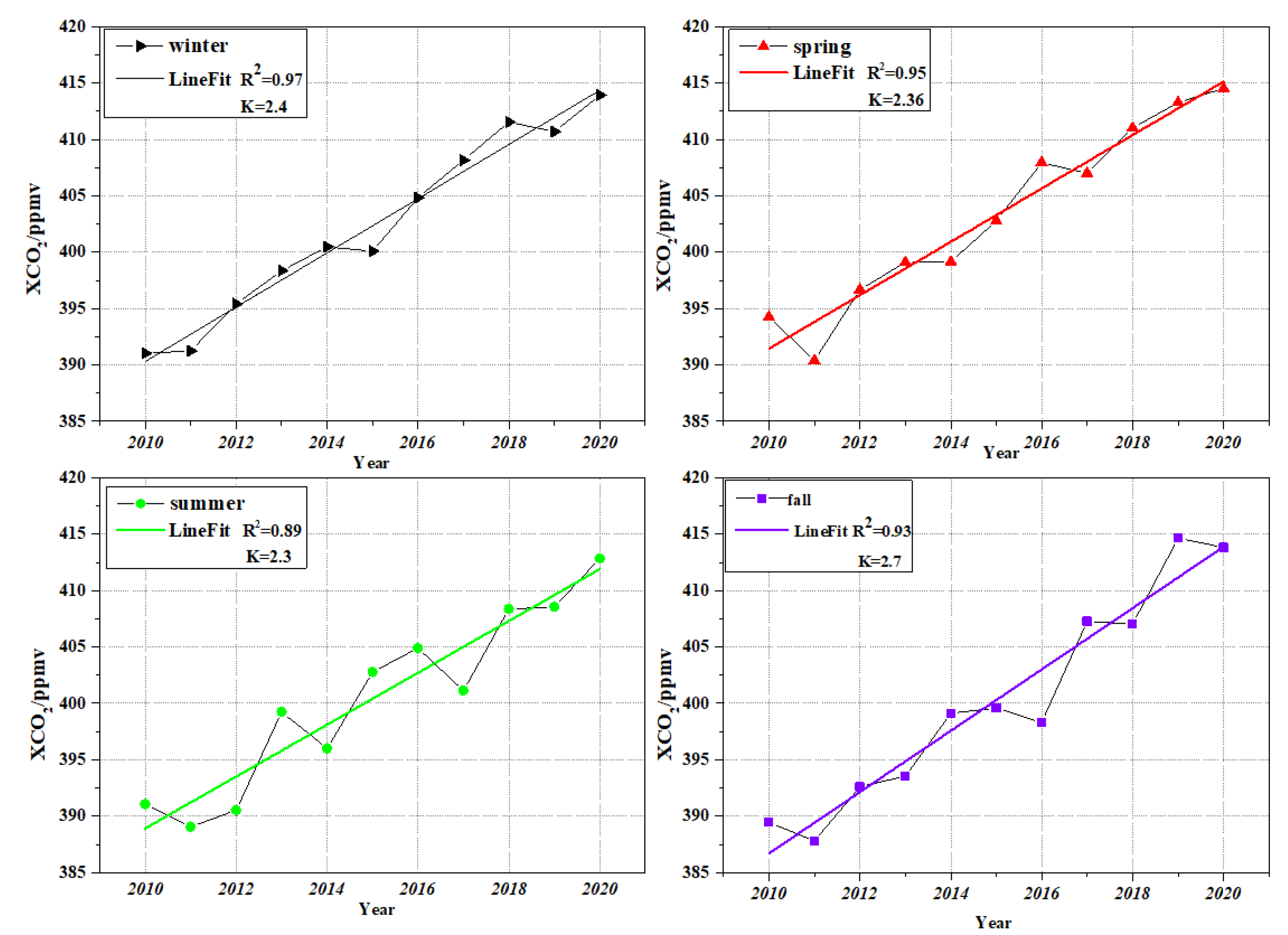

Figure 5 displays the trend of XCO

2 concentration over time (from 2010 to 2020) across different seasons (winter, spring, summer, and autumn) in Hefei. By fitting the data points with a linear regression model, it is evident from the figure that XCO

2 concentrations exhibit an annual increasing trend in all seasons. The rates of increase are relatively stable in winter, spring, and autumn, whereas in summer, the rate fluctuates, resulting in a slightly lower R² value and a poorer fit between the model and the data. For winter, spring, and autumn, the data points show a consistent yearly upward trend, with high R² values (above 0.95) for the linear regression equations, indicating a good fit between the model and the data. The slopes for all four seasons are greater than 2.3, suggesting that the annual growth rate of XCO

2 is above 2.3 ppmv for each season. The growth rates for spring, summer, and winter hover around 2.3, while the growth rate for autumn reaches 2.7 ppmv, possibly due to weakened plant photosynthesis and enhanced respiration, as well as human activities such as burning crop residues like wheat straw. The figure also reveals significant seasonal variations in CO

2 concentrations in the region. Specifically, CO

2 concentrations are generally lower in summer and higher in winter. This seasonal pattern is particularly pronounced in Hefei's atmosphere. During summer, enhanced plant photosynthesis leads to the absorption of large amounts of CO

2, reducing its concentration in the atmosphere. Conversely, in winter, weakened plant photosynthesis coupled with increased human activities such as heating contribute to higher CO

2 emissions, thereby elevating atmospheric CO

2 concentrations. Overall, the seasonal changes in CO

2 concentrations in Hefei are influenced by a combination of factors, including plant photosynthesis, human activities, and meteorological conditions.

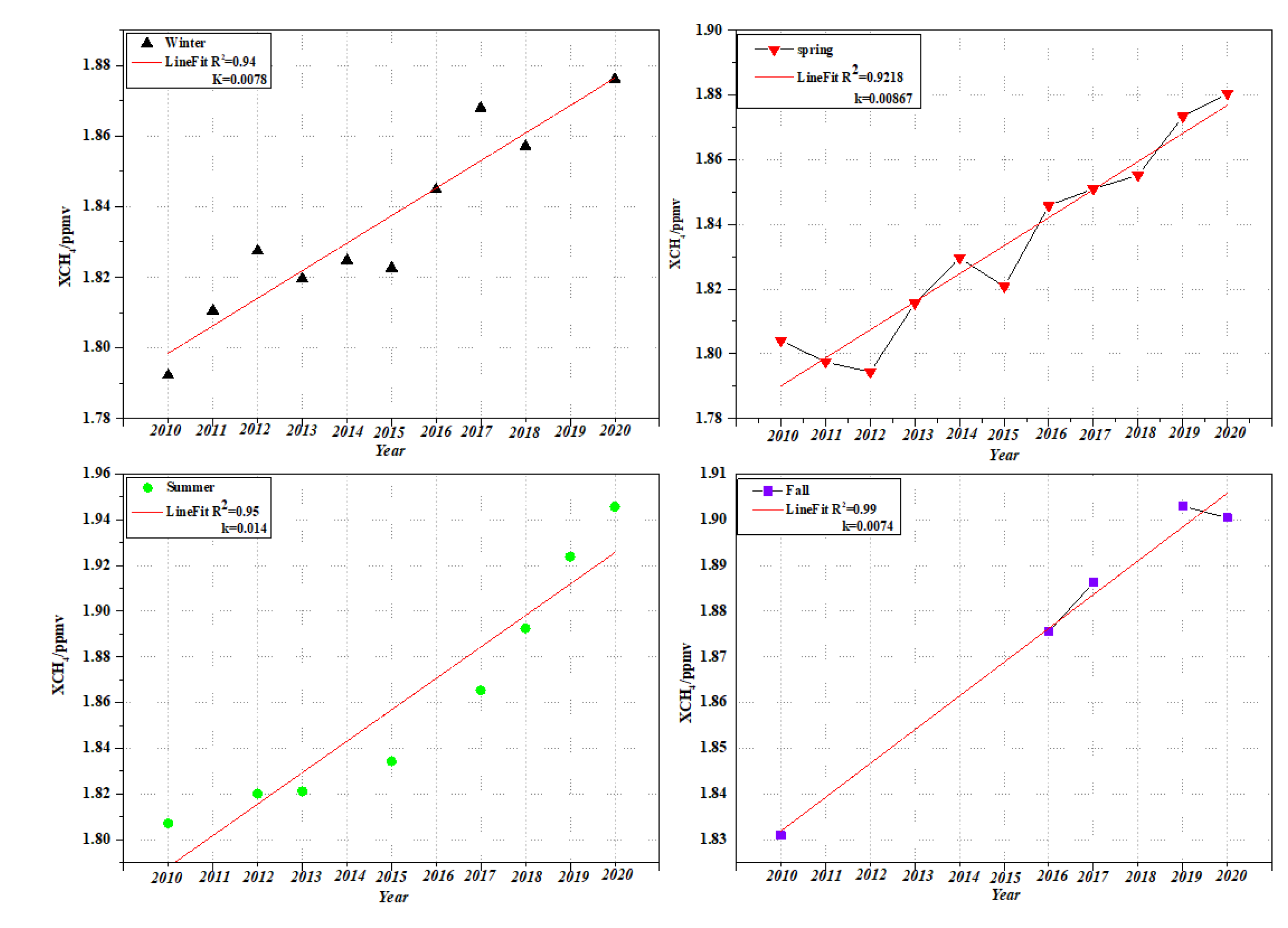

The

Figure 6 illustrates the trend of XCH

4 over time from 2010 to 2020. It is evident from the figure that the concentration of CH

4 in the atmosphere of Hefei exhibits distinct seasonal variations and an annual upward trend. The column concentration of CH

4 in Hefei is higher during summer and autumn, while it is relatively lower in winter and spring. This seasonal variation may be attributed to complex factors such as the balance between sources and sinks, as well as meteorological and climatic conditions. For instance, during summer, enhanced plant activity and potential increased emission sources (such as agricultural activities) may lead to an increase in atmospheric CH

4 concentration. Conversely, in winter, weakened plant activity, reduced emission sources, and possibly poorer atmospheric dispersion conditions result in relatively lower CH

4 concentrations. The linear fit coefficients for all four seasons are above 0.92 (with potential bias in the fit for autumn due to limited data), indicating a good fit. Despite seasonal fluctuations, the overall concentration of CH

4 in the atmosphere of Hefei shows a gradual annual increase. XCH

4 exhibits an upward trend in different seasons, but the rate and variability of this increase differ. The rates of increase are relatively slower in winter and autumn, while the fastest increase is observed in summer, with an average annual growth rate of XCH

4 reaching 0.014 ppmv.

3.3. The Correlation Between XCH4 and XCO2

The main sources of carbon dioxide include natural processes and human activities. Natural processes such as respiration and volcanic eruptions, and human activities such as fossil fuel combustion and deforestation. Carbon dioxide is one of the main components of greenhouse gases. The increase of its concentration will lead to the intensification of the greenhouse effect, which will lead to a series of environmental problems such as global warming, glacier melting, sea level rise and so on. Carbon monoxide mainly comes from incomplete combustion of carbonaceous substances, such as coal, wood, natural gas, etc. Automobile exhaust, factory exhaust and indoor heating equipment are common sources.

The

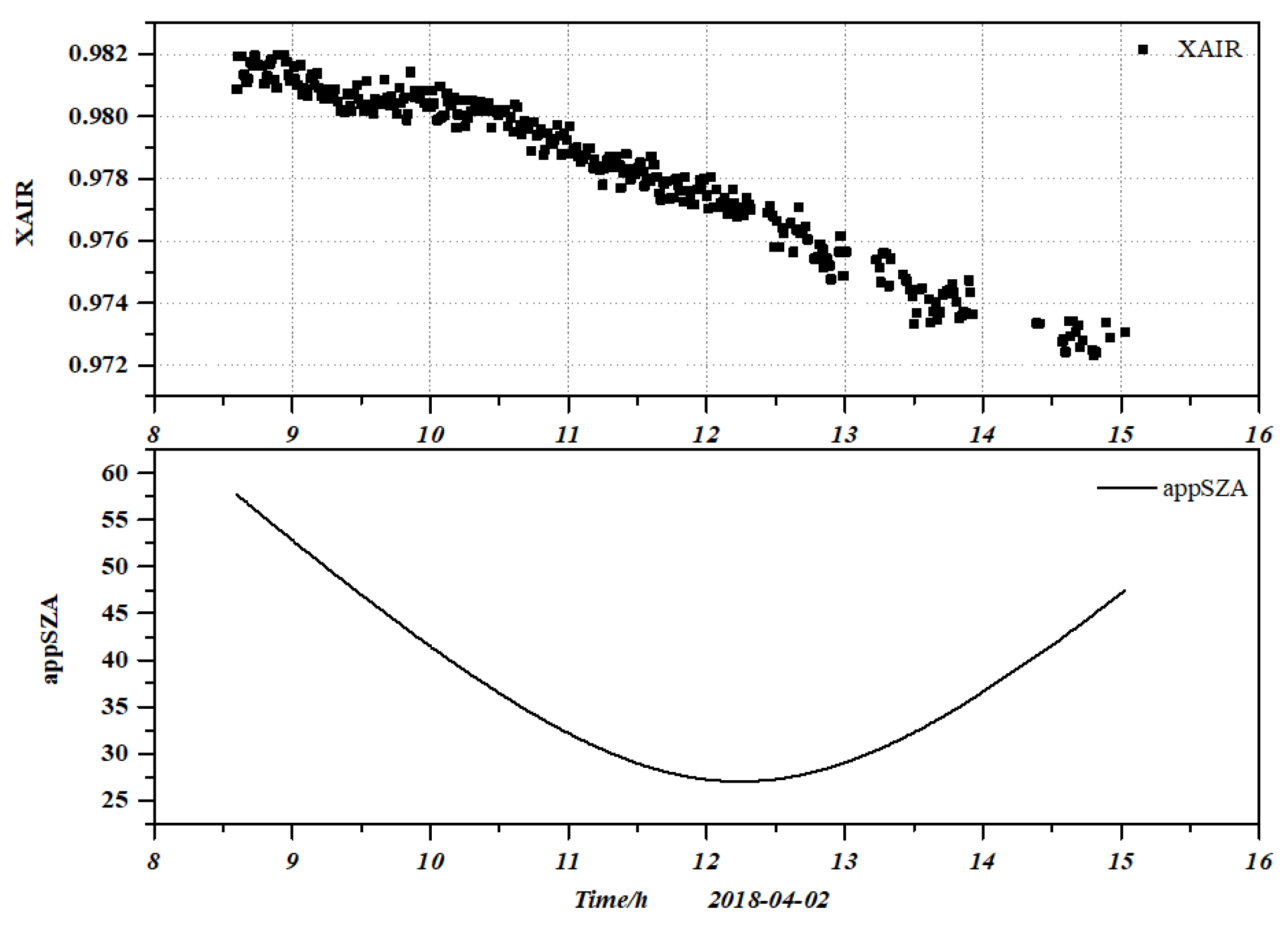

Figure 7 shows variation of air quality and zenith angle with time. XAIR likely represents a parameter related to air quality or atmospheric transmission. It shows a decreasing trend from 9:00 to 15:00. This decline could reflect changes in atmospheric scattering/absorption (e.g., due to aerosols or trace gases). The apparent solar zenith angle (appSZA) follows a U-shaped curve, reaching a minimum around noon. This matches the diurnal cycle of solar elevation (zenith angle is smallest when the sun is highest).

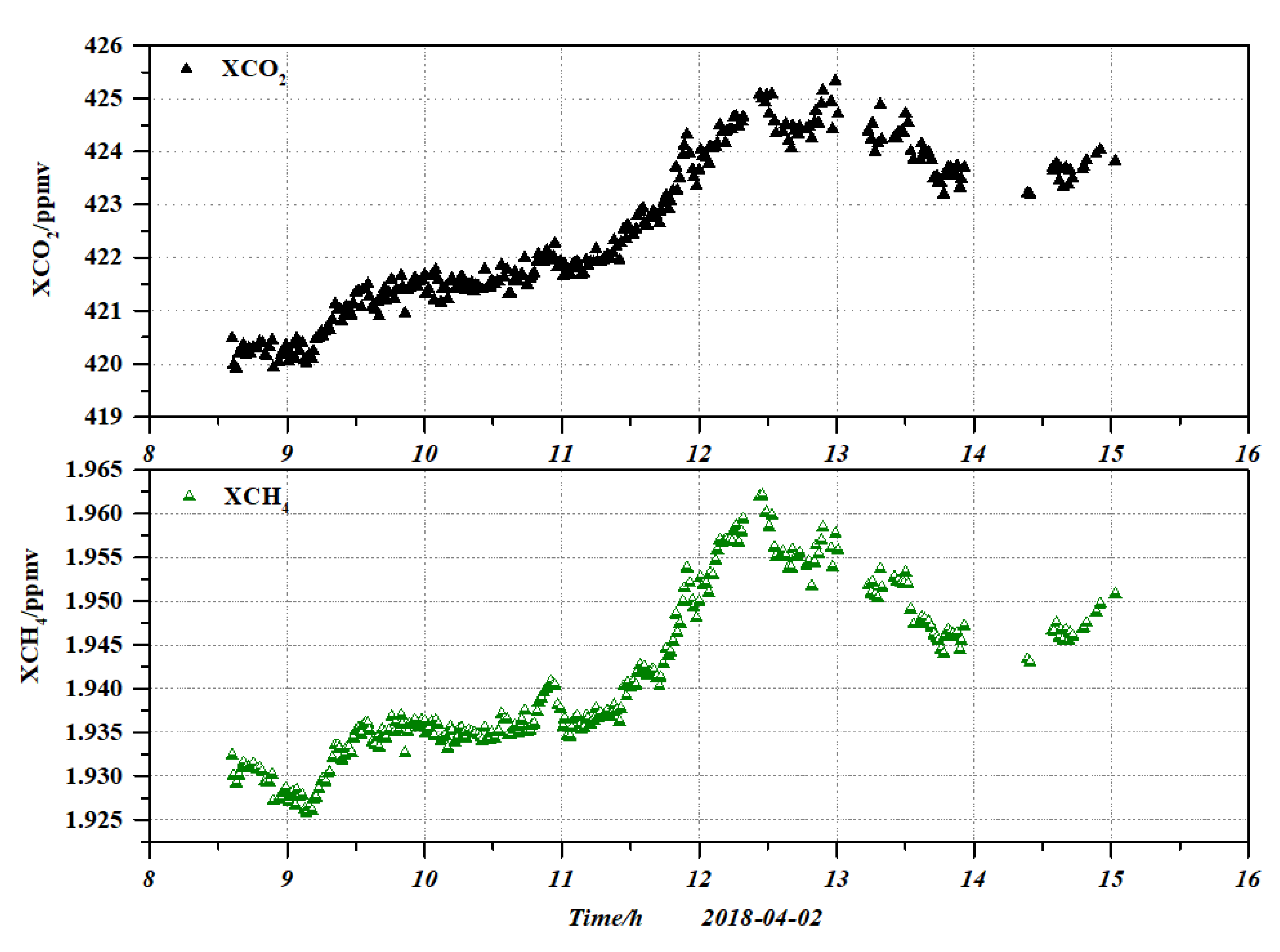

The diurnal variations of CO

2 and CH

4 were further analyzed. The

Figure 8 shows the diurnal variations in column concentrations of CO

2 and CH

4 retrieved by Fourier transform spectrometer on April 2, 2018. The weather on that day was sunny and the observation conditions were superior. It can be seen from the figure that the air quality showed a linear relationship with time. The change trends of CO

2 and CH

4 shown in the figure are similar, showing the characteristics of low in the morning and evening and high at noon, and reaching the peak at 13:00 noon. The observed trends can be attributed to the following factors. First, the daily periodic characteristics of human activity emissions, the early peak of urban traffic and the start of industrial production release a large number of CO

2 and CH

4 gases. At the same time, the main CH

4 emission sources in agricultural production, such as paddy field irrigation and livestock breeding, are enhanced under the condition of sufficient sunshine. The second is the regulation of boundary layer dynamics. When the solar radiation increases, the surface heat causes convective activities, and the height of the boundary layer rises. This process will vertically transport the gas emitted from the surface to the top of the mixing layer, resulting in the measured column concentration gradually rising with the development of the mixing layer. In the afternoon, the boundary layer tends to be stable, and the diffusion ability of pollutants in the vertical direction is weakened, forming the concentration accumulation effect.

The change trends of CO2 and CH4 are highly synchronous, indicating that they have their homologous emission characteristics, which may be due to the coordinated change of common emission sources such as traffic sources, energy production and waste disposal during the day, resulting in the same trend of daily change patterns of the two. The correlation between the two will be analyzed in next Section.

Figure 8.

The diurnal variations XCO2 and XCH4 retrieved by Fourier transform spectrometer on April 2, 2018.

Figure 8.

The diurnal variations XCO2 and XCH4 retrieved by Fourier transform spectrometer on April 2, 2018.

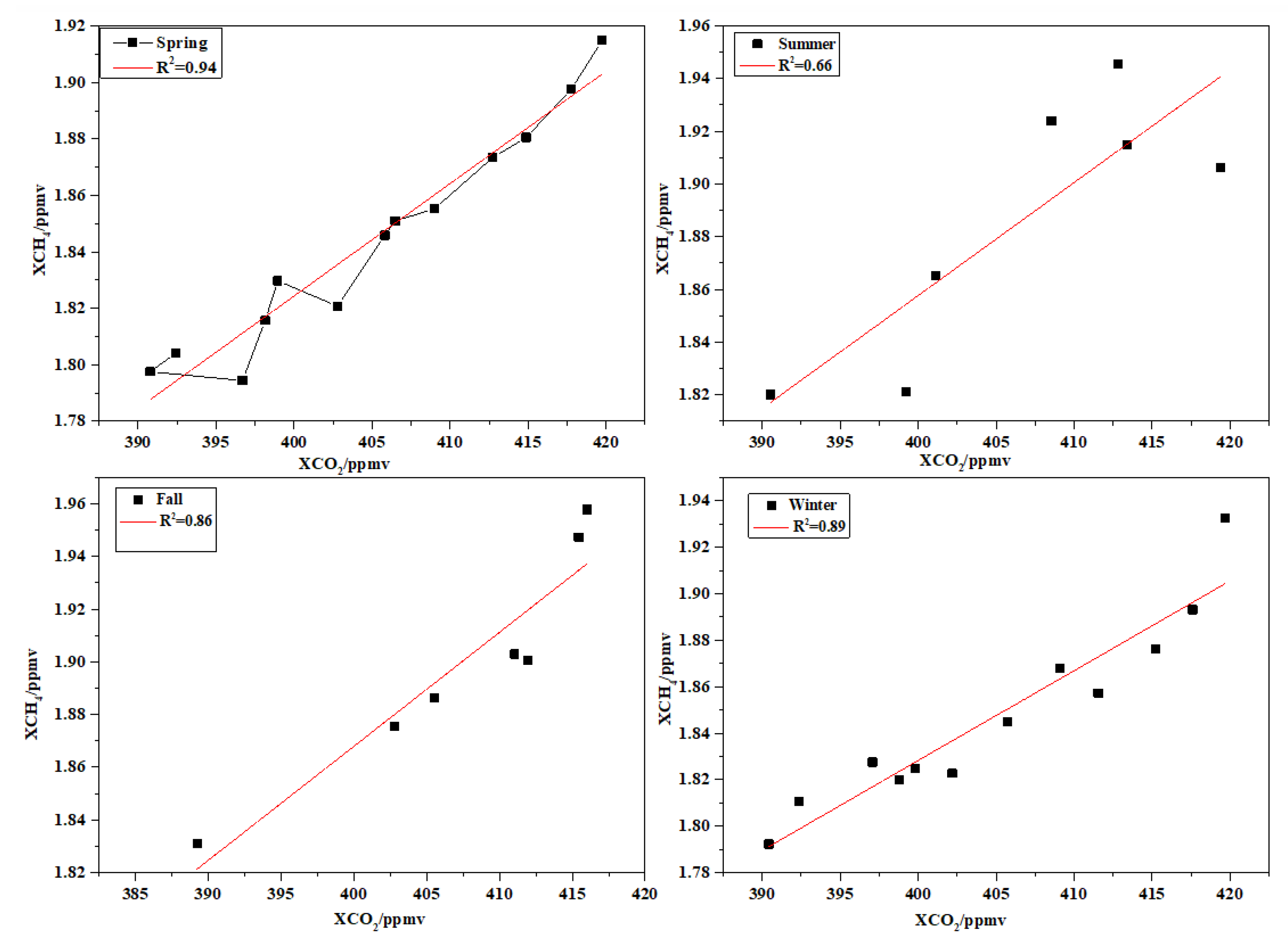

Figure 9.

The correlation between CO2 and CH4 in different seasons.

Figure 9.

The correlation between CO2 and CH4 in different seasons.

Linear analysis is usually used to determine whether they both come from combustion sources. It can be seen from the figure that the correlation degree of CO

2 and CH

4 concentrations is very high in spring, autumn and winter, and the correlation coefficient R

2 is higher than 0.86, especially 0.94 in spring, indicating that they are driven by the same emission activities or atmospheric processes. This is because the boundary layer is low and the atmosphere is stable in spring, autumn and winter, and the diffusion of CO

2 and CH

4 emitted from the surface is limited in the vertical direction. At this time, seasonal anthropogenic activities such as coal-fired heating and biomass combustion release two kinds of gases simultaneously, and their emission intensity is strongly coupled with meteorological conditions (such as low temperature and calm wind), thus showing a high correlation. In summer, photosynthesis is strong, and plants absorb a large amount of CO

2 through photosynthesis, while high temperature promotes CH

4 emissions from natural sources such as wetlands and paddy fields, resulting in a decrease in the correlation between the two sources. In addition, strong convective weather enhances pollutant diffusion and further weakens the synchronization of concentration changes. From the daily variation

Figure 8, we can see that the peaks of CO

2 and CH

4 are consistent, indicating that they do not have homology. This may be related to the monsoon. For further analysis, the backward trajectory model is used for analysis.

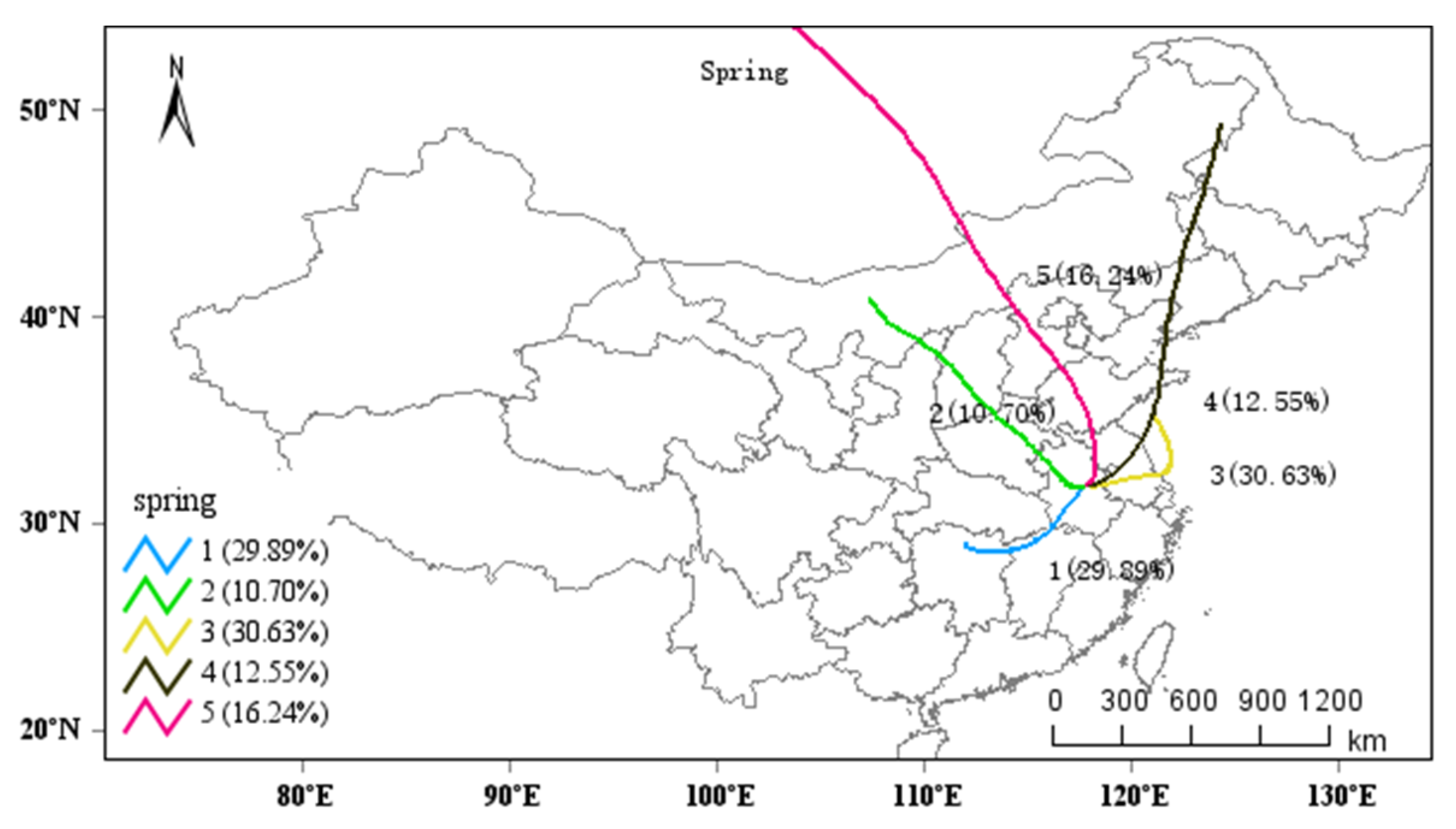

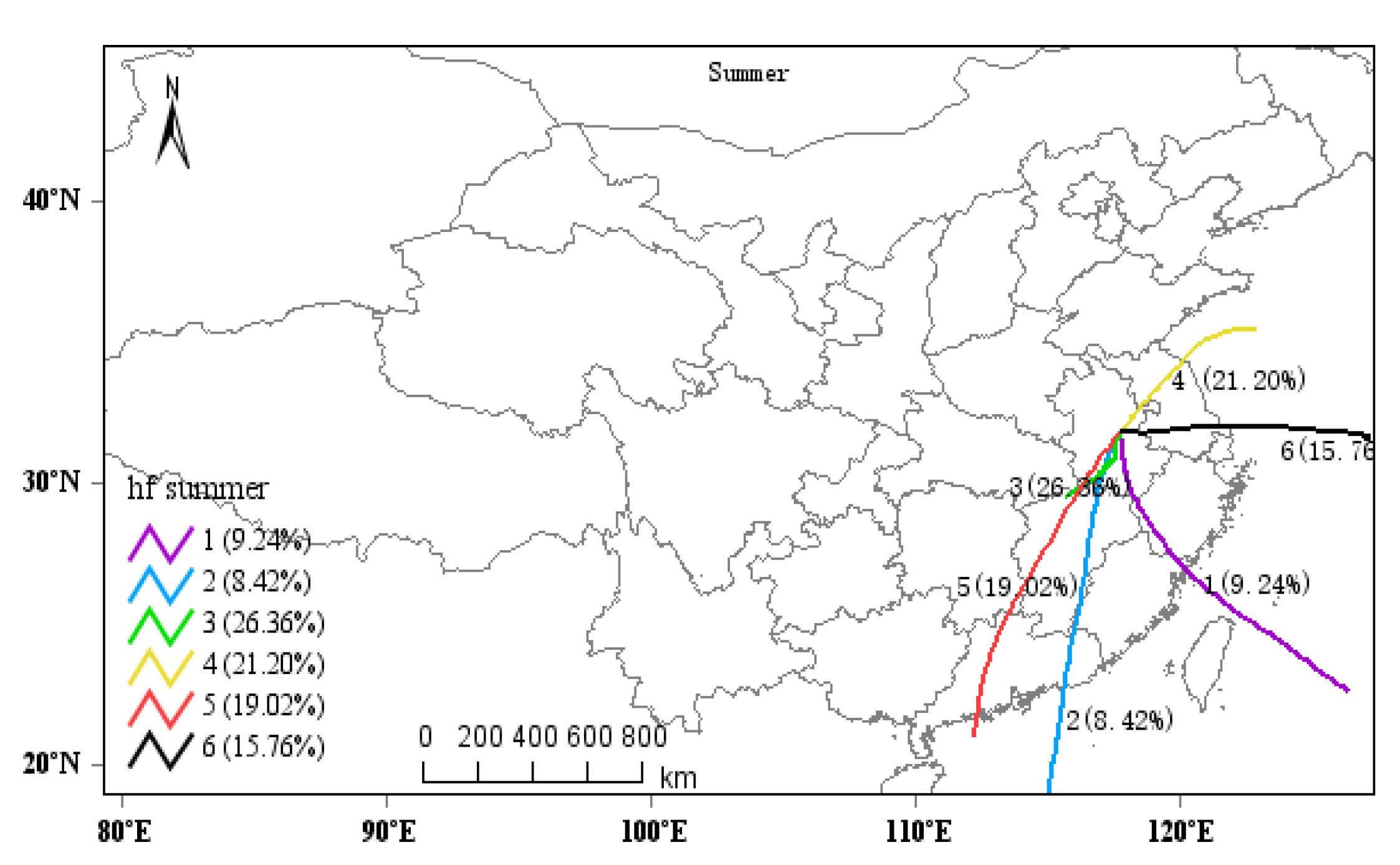

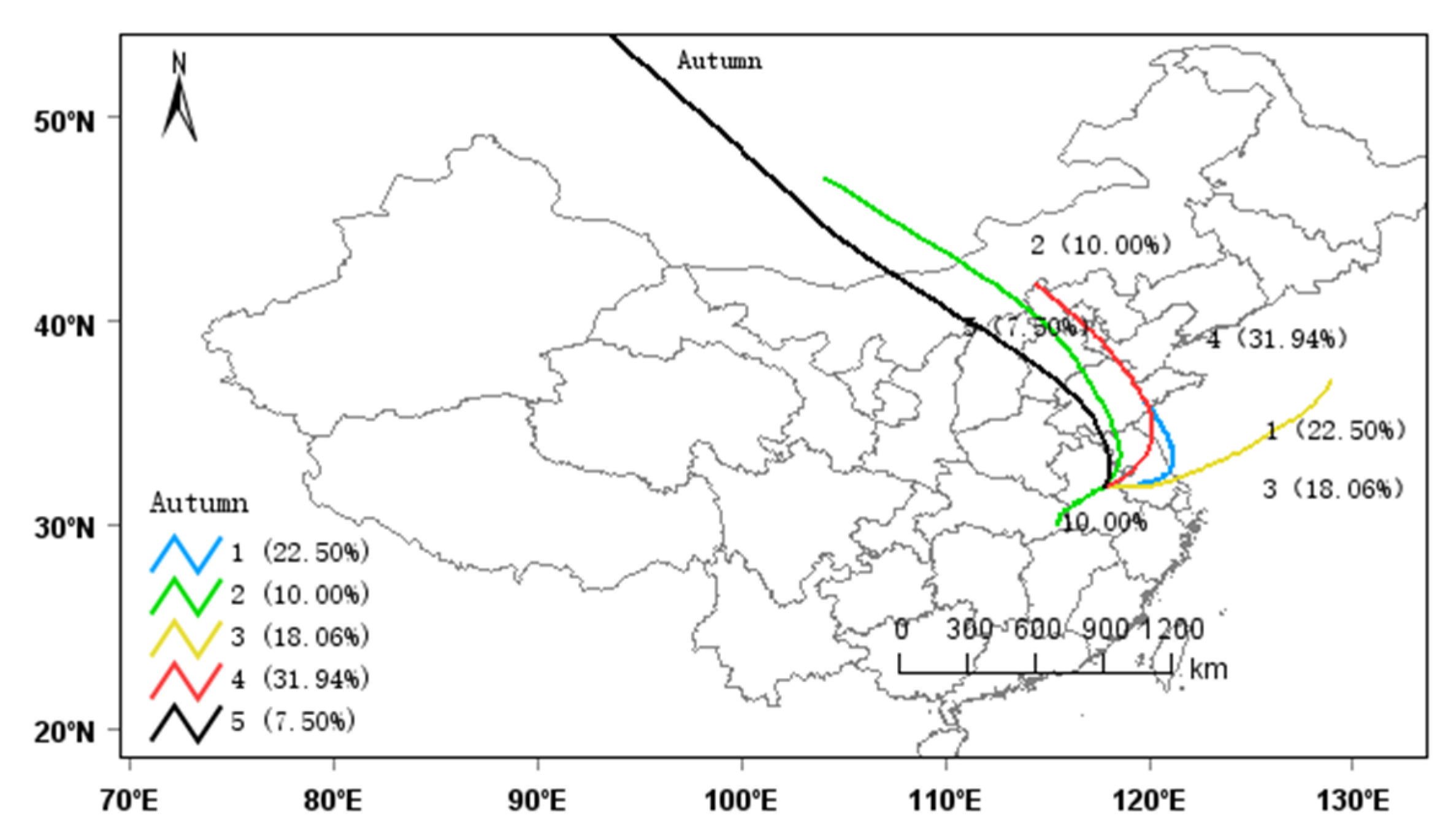

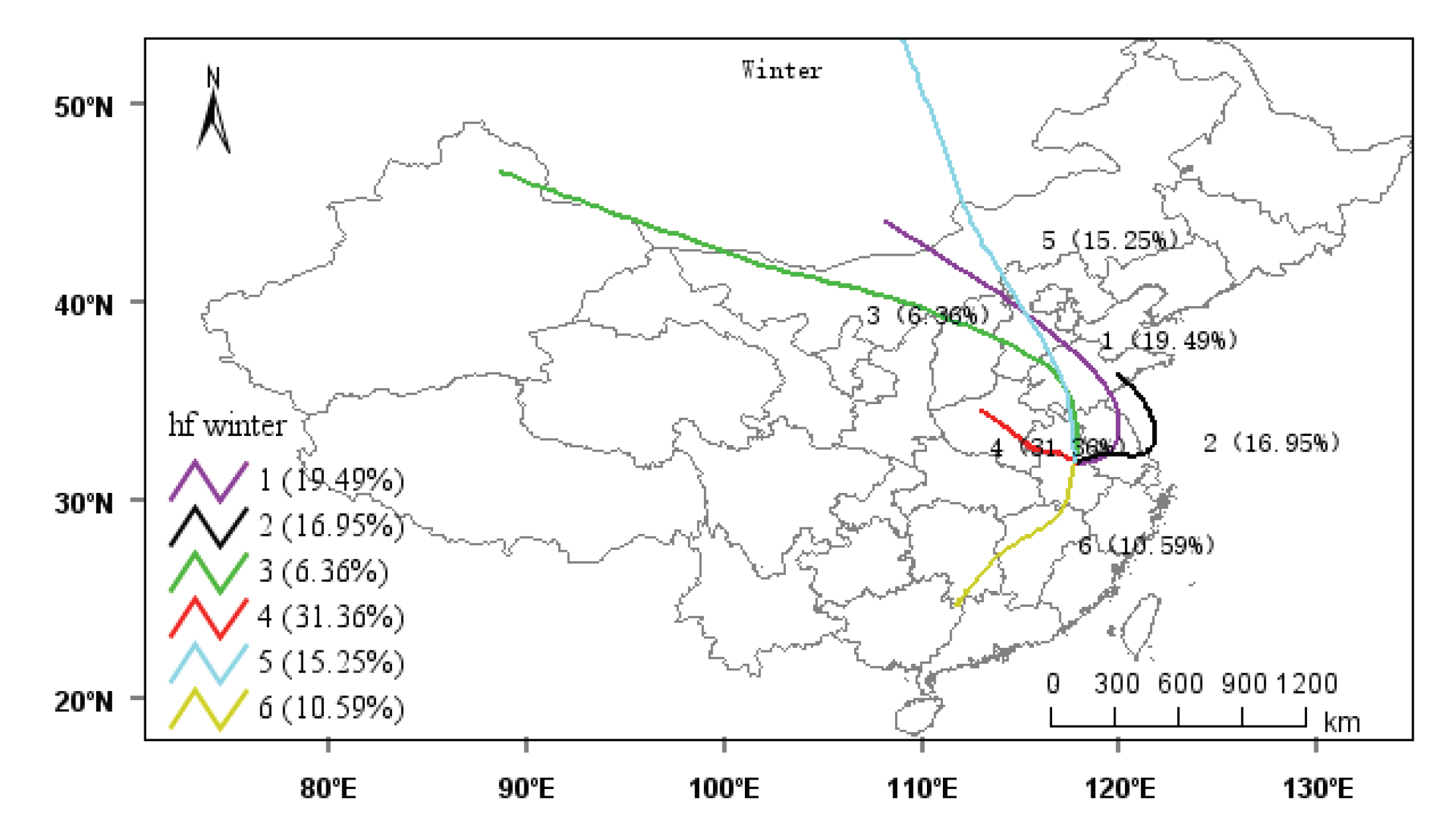

In this study, the model was applied to Hefei (31.51°N, 117.17°E) to simulate daily 72-hour backward trajectories from January to December 2020. The meteorological year was divided into four seasons: spring (March–May), summer (June–August), autumn (September–November), and winter (December–February). Simulations were conducted for three arrival heights (500 m, 1000 m, and 1500 m above ground level) to represent different transport layers. A clustering analysis was subsequently performed on the trajectory endpoints for each season to identify dominant transport pathways and their seasonal variations.

Figure 10.

Cluster analysis of 72 h back trajectories of HeFei in spring, 2020.

Figure 10.

Cluster analysis of 72 h back trajectories of HeFei in spring, 2020.

The three prevailing trajectories during spring comprise a southwesterly trajectory (30.63%, originating from the Indian Peninsula/Bay of Bengal), a northwesterly trajectory (29.89%, originating from Central Asia), and a northerly trajectory (16.24%, originating from Mongolia/Siberia). Air masses are characterized by diverse origins, reflecting both maritime and continental influences.

The southwesterly trajectory may facilitate the transport of methane emissions from agricultural activities in South Asia—such as rice cultivation and livestock—as well as CO₂ derived from biomass burning practices, including seasonal agricultural residue burning in spring. The northwesterly trajectory, traversing the arid regions of Central Asia, is associated with relatively low local anthropogenic emissions. However, it may convey background levels of greenhouse gases resulting from long-range transport from industrial regions in Europe or Western Asia. The northerly trajectory originates from the relatively pristine boreal forests and high-latitude zones, and is generally associated with lower background concentrations of greenhouse gases.

Trajectories during summer exhibit a high degree of spatial concentration, with notably shortened paths clustered around the study region, indicating the dominance of strong local circulation systems. The predominant southeastern and southern trajectories collectively account for the highest proportion (26.36% + 21.20%), reflecting the overwhelming influence of the summer monsoon originating from the ocean.

The prevalence of marine air masses—clean and moist—from the Pacific Ocean leads to dilution of greenhouse gas concentrations at the receptor site. Consequently, the observed levels are likely closer to regional background values. Furthermore, summer corresponds to the peak growing season in the Northern Hemisphere, during which vegetation acts as a strong CO₂ sink. The dominance of local trajectories implies that the carbon sequestration effect of ecosystems around the receptor site significantly contributes to reducing observed CO₂ concentrations.

In contrast, elevated temperatures and rice paddy irrigation during this season enhance methane emissions. Local trajectories are likely to capture these intense regional methane sources.

The autumn trajectory pattern is characterized by the coexistence of a long-range northwesterly path (31.94%) and a short-range local path (22.50%). This period represents a transitional phase in which the summer monsoon has retreated, while the full establishment of the winter monsoon has not yet occurred, resulting in complex airflow regimes. The northwesterly trajectory is likely associated with elevated CO₂ concentrations, attributable to the commencement of heating activities—primarily fossil fuel combustion—in regions of Central Asia and Siberia.

In contrast, the local trajectory reflects biogenic influences during the autumn season: vegetation senescence leads to a reduction in carbon sink capacity, and ecosystems may transition toward becoming net carbon sources due to processes such as soil respiration and litter decomposition. Air masses associated with this local path may thus capture the shift in regional ecosystem function from a carbon sink to a carbon source.

The winter trajectory pattern is distinctly dominated by a long-range northwesterly path (31.36%), characterized by its straight and stable pathway, reflecting the influence of a strong and persistent winter monsoon. Additional trajectories include a northern path (19.49%) and a southwestern path (16.95%), which play secondary roles. The northwesterly trajectory acts as a critical pollution transport corridor, passing over regions with substantial heating demands in northern China and Central Asia. This pathway carries significant amounts of CO₂ derived from fossil fuel combustion. The rapid and stable airflow ensures highly efficient transport, effectively moving greenhouse gases emitted in upwind regions to downwind areas such as southeastern China, leading to episodic concentration peaks at the receptor site. In contrast, the southwesterly trajectory may convey modest levels of methane originating from South Asia. However, its influence is generally overshadowed by the dominant northwesterly flow in terms of overall impact on greenhouse gas concentrations.

Figure 11.

Cluster analysis of 72 h back trajectories of HeFei in summer, 2020.

Figure 11.

Cluster analysis of 72 h back trajectories of HeFei in summer, 2020.

Figure 12.

Cluster analysis of 72 h back trajectories of HeFei in autumn, 2020.

Figure 12.

Cluster analysis of 72 h back trajectories of HeFei in autumn, 2020.

Figure 13.

Cluster analysis of 72 h back trajectories of HeFei in winter, 2020.

Figure 13.

Cluster analysis of 72 h back trajectories of HeFei in winter, 2020.

Based on the above analysis, it is evident that the Hefei region exhibits a pronounced seasonal cycle in greenhouse gas characteristics, which is predominantly governed by the East Asian monsoon system. During the summer half of the year, clean marine air masses and the carbon sequestration effect of ecosystems lead to relatively lower greenhouse gas concentrations. In contrast, the winter half-year is characterized by the dominance of polluted continental air masses and emissions from fossil fuel combustion, resulting in elevated concentration levels.

The northwestern inland regions are identified as the most critical external source area influencing CO₂ concentrations at the receptor site during winter. Meanwhile, the areas surrounding the receptor site in summer function as significant CO₂ sinks, although their substantial methane emissions cannot be overlooked. Additionally, South Asia appears to contribute persistently to the background methane levels at the receptor site during both spring and winter seasons.