1. Introduction

For over thirty years, the achievement of conservation by various institutions and communities via ecotourism development has proven effective for local people living around protected areas [

1]. Ecotourism is one of the vibrant and ever-growing sectors of the tourism industry [

2] and has been an initiative adopted by countries globally to conserve their natural and cultural heritage [

3] It is a preferred form of tourism by many countries because of its economic gains aside from its primary purpose of conservation [

4]. Drumm and Moore [

1] indicate that ecotourism promises the promotion of the local community, generating new businesses and providing a win-win situation for all involved. Ecotourism is now seen as alternative tourism and is now being embraced all around the world because it has proven effective in sustainable development; hinting that many developing countries are now including it in their development strategies [

7]. [

4] argues the necessity of ecotourism regarding the recently set sustainable development goals and how one of the goals (SDG 11) strongly supports documentation, continuity, and sustainability of cities and communities.

Most ecotourism sites only engage in sightseeing activities of the conserved fauna, flora, and water bodies. Undertaking these activities only would not help enrich the experiences of tourists while motivating them to stay for longer periods at the ecotourism facilities. Therefore, there have been attempts by some ecotourism sites to introduce other extended activities to improve visitors' experience [

8]. One such activity that can improve visitors' experience while generating additional revenue for ecotourism sites and the local people in the communities where the ecotourism facility is located is the introduction of ecomuseums that provide tangible evidence of conservation [

9]. The introduction of ecomuseums at ecotourism sites would ensure the creation of landscape communities, where cultural affiliations and interpretations of the landscapes at the ecotourism site can be offered to tourists [

10]. Tourists are very much attracted not only to the natural scenery offered at ecotourism sites but also to the cultural and natural heritage [

11] that are often not offered by most sites. Yet, the place's identity history and the artistic as well as lifestyle heritage of the fringed communities where an ecotourism site has been set up contributes to tourists' desire to stay more and spend more in an ecotourism region [

7].

It is important to introduce ecomuseums at ecotourism sites because culture, heritage, nature, and tourism have always been interconnected [

12] and perceived to enrich tourists' experience [

13].The natural heritage which is the primary focus of ecotourism is closely knit with the cultural heritage that projects the lived experiences of the people [

4] with both of them contributing to a richer visitor experience. Introducing ecomuseums at ecotourism sites is a sure way of drawing in the members of the local communities around the facility to support conservation, after all, it would open various entrepreneurial avenues for them Exhibitions at the ecomuseums could be used as platforms for discussing environmentally accepted behaviours [

14] that most times agree with the accepted cultural ethos of the local communities. Such fora organised as part of the activities of museums have the capability of instilling a love for nature and conservation ideals in both domestic and international visitors [

15].

In Ghana, the Nature Conservation Research Centre (NCRC) and the Ghana Wildlife Society have initiated the setting up of various community-based ecotourism centres at the existing forest and wildlife reserves [

16]. The ecotourism sites were established with the sole objective of widening the benefits from the tourism industry to rural communities [

17]. This would serve as a means of boosting the rural economies [

18]. However, if the ecotourism facilities cannot provide enough entrepreneurial opportunities for the local people, then it will defeat one of its key purposes of job generation for local communities. Therefore, extended activities made possible through the establishment of ecomuseums could be a catalyst not only for maintaining the environmental and cultural heritage of the ecotourism facility but also for generating numerous job opportunities for the people [

19,

20]. Preliminary research at the

Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary at Kumawu revealed that they do not have extended activities aside from the sightseeing of the wildlife resources tourists. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the possibility of establishing an ecomuseum and its allied activities as a likely means of boosting ecotourism development at the sanctuary. This ecomuseum is considered from the perspective of a museum as an institution within a physical structure and not the unconventional museum of ideologies of space. The research questions that guided this scholarly inquiry were:

What is the state of ecotourism development at the Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary, Ghana?

How can the ecotourism potential at the Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary be increased to generate more revenue for the Wildlife Division and the local communities in the region?

How can the establishment of an ecomuseum promote ecotourism development, enhance visitors’ tourism experience, generate revenue for the local people and promote the cultural heritage of host communities?

How should a typical ecomuseum be designed and constructed to increase the interest of both domestic and international visitors as an extended activity at Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary?

1.1. Ecomuseum: Towards a Definition

Globally, ecomuseums provide a growing array of themes and models to save cultural and natural heritage due to their adaptable framework. While a consistent methodology is absent, ecomuseums significantly influence history, culture, environment, heritage, tourism, and the sustainability of communities over the long term. Defining the concept of an ecomuseum is challenging since it consistently represents a singular experience, an “invention” tailored to the local environment and spearheaded by passionate individuals, often lacking any museum expertise [

21]. Eco museums uniquely integrate intangible elements, such as historical recollections, to illustrate the dynamic nature of human existence. Historically, the 1960s witnessed an increase in environmental consciousness that has since integrated into the social and political mainstream, exemplified by the focus on the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development 1992. Environmental awareness extends beyond the pursuit of technological solutions to the environmental catastrophe; it fundamentally interrogates the relationships among nature, culture, and community. This understanding, together with a renewed emphasis on strengthening local communities, extended to the institution of the museum, prompting enquiries into the definition of heritage and its preservation, exhibition, and transmission. A revolution in museology emerged, necessitating museums to address societal demands, beyond the conventional framework of buildings, collections, and research. This museum revolution necessitated that museums address the requirements of society, governance, and the environment [

22]. In 1971, George-Henri Rivière and Hugues de Varine introduced the term

ecomuseum in response to the request for a redefinition of museology. The primary aim was to conserve history within its original context referred to as

in situ, a concept that denotes the preservation and exhibition of cultural or historical artefacts at their original place, enabling visitors to engage with them in their natural environment.

The ecomuseum constituted a movement rather than a novel institution. Rivière articulated the changing concept of the ecomuseum and characterised it as possessing limitless variation [

23] shaped and energised by public authority and the local community. The latest definition of an ecomuseum is provided by [24:116] who defines it as “a community-oriented museum or heritage initiative that promotes sustainable development.” Davis’s concept emphasises the need for local community engagement, indicating that heritage is a component of sustainable community development. The ecomuseum gathers, maintains, shows, and investigates legacy, akin to a regular museum [

25]. However, it additionally engages local people in heritage conservation and museum advancement [

5]. A significant feature of the ecomuseum is its presentation of history, specifically

in situ, maintaining its connection to the community’s daily life [

26,

27]. The distinction between ecomuseums and open-air museums lies in the fact that the latter does not incorporate a community as an integral component of the museum. Although

eco in ecomuseum largely denotes community, ecomuseums also conserve natural environments. In contrast to conventional museums, which operate in a more institutionalised fashion, ecomuseums emphasise the integration of dynamic processes and activities [

28]. In another perspective, Keyes [

29] defines ecomuseum as a type of museum created for, by, and concerning individuals within their

own environment. By this definition, the ecomuseum serves as a framework for conveying and safeguarding a region’s natural and cultural heritage, and for the advancement of a location through a communal methodology. All committed players and agents of local development recognise the importance, indeed the need, of including the entire community at every level of any initiative that may affect the lives and environment of the populace. Their deliberate endorsement and proactive involvement will serve as the most effective assurances for the project’s success.

Since the inception of the word ecomuseum, interest in the concept has continued to surge among both the public and academic circles. ecomuseums have been studied within the academic discipline of ecomuseology, which is closely associated with anthropology, sociology, and museology. Research in ecomuseology has thus far focused on theoretical dimensions [

30,

31], cultural studies and anthropology [

32,

33] landscape studies [

34,

35] and economic, ecological, and socio-cultural development [

27,

36], Within a broader scope, ecomuseums provide an opportunity for outsiders to see the life of local inhabitants, while also possessing the capacity to enhance tourism [

37]. Ecomuseums seek to foster self-awareness and self-education within the local community by deviating from the conventional pedagogical paradigm of museums [

38]. Ecomuseums are seen as a sustainable methodology for preserving and exhibiting a particular community’s tangible and intangible history, enhancing cultural identity via community involvement in the preservation process [

39].

The ecomuseum, as an innovative museological form, serves as a hub for community engagement, showcasing history, shaping identity and representation, and fostering creative solutions for communal challenges. René Rivard developed conceptual frameworks to juxtapose the traditional museum (building + collections + specialists + visitor) with the ecomuseum (territory + heritage + memory + community). He differentiated between ecological museums, such as natural history museums, ecological museums, including field centres and nature parks, and ecomuseums, which Rivard characterised as the interplay between human presence and their environment [40:69]. According to Hodges [41:150], “the new museum is a concept, not a place” ecomuseums often see both the museum structure and the adjacent human and natural ecosystems as integral components of the ecomuseum. Although ecomuseums welcome visitors, their principal objective is to cater to community interests rather than attract tourists or produce profit. The idea of the ecomuseum by highlighting that we typically perceive a museum as a repository of artistic artefacts, a sanctuary of commodities, and culture encapsulated [

42]. In many societies, individuals perceive the museum structure just as a gathering space, while the surrounding environment or community is considered the museum termed as an “ecomuseum” [42:35]. The concept of an ecomuseum as an institution beyond the confines of constructed spaces fosters an environment that cultivates democratic and reciprocal relationships; the museum’s-built environment engages with the wider community, while the heritage of the community’s past interacts with contemporary and future concerns. The definition of an ecomuseum is primarily based on its origin and function rather than its physical attributes or the artefacts it houses, leading to diverse interpretations of the concept globally, which differ markedly from its original industrial emphasis. In the strictest sense, an ecomuseum must be founded on the character of the larger region and depend on the involvement and cooperation of citizens, associations, and other municipal and governmental authorities, employing a bottom-up approach. An essential prerequisite for guaranteeing the sustainability of such a project is its intrinsic linkage to the sectors of production, processing, tourism, and culture.

1.2. The Ecomuseum as a Mediator

Several scholars have underscored ecomuseums as an effective long-term approach for the protection of local history and the promotion of sustainable community development, while also emphasising their efficacy in cultural heritage conservation and preservation [

27,

35,

36,

43,

44]. As identified earlier, ecomuseums are community-based museums that explore the interplay between individuals, society, and environment context. This is accomplished through the integration of local agri-food and craft production, manufacturing and processing, small-scale tourism, and cultural, and educational activities. A significant number of the world’s ecomuseums are situated in Mediterranean nations; namely, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and predominantly southern France. In Greece, the notion of an ecomuseum is not extensively prevalent, resulting in a limited number of ecomuseums throughout the country. Most importantly, ecomuseums are very effective in preserving the varied attributes of rural and natural environments. For example, ecomuseums in Denmark and the Netherlands emphasise the preservation of traditional traditions and rural lifestyles [

45]. Hubert [46:186] asserts that the ecomuseum idea prioritises communal memory, highlighting the importance of geography, memory, and identity for unique, sensitive, or marginalised populations. An illustration of this is the Him Dak ecomuseum in Arizona, overseen by the Ak-Chin Indian Community [

47,

48], which seeks to enhance tribal identity, promote community cohesion, and enrich cultural legacy. The notion of a

feeling of place relies on the active engagement of the community [

49], deemed fundamental in this domain [

26] ecomuseums offer a venue for community members and the public to participate in the planning and implementation process, allowing them to understand, critique, and navigate the issues they face [26:81]. An ecomuseum characterised as a community-based museum or heritage initiative also fosters sustainable development [24:199], wherein sustainable growth generally includes heritage conservation alongside the social and economic progress of the community, as illustrated by the pivotal ‘twenty-one principles’ outlined by [

50,

51] drawing from earlier works by researchers [

40,

52].

Additional growth of the ecomuseum’s mission development appears to be occurring. A comprehensive strategy for the sociocultural advancement of the local region is evolving [

53]an ecomuseum can yield substantial economic advantages for a community or the local economy by fostering sustainable tourism that highlights local heritage, culture, and natural surroundings. This results in heightened visitor expenditure, job creation in associated sectors such as hospitality and guiding services, and potential economic diversification for the region, while simultaneously cultivating local pride and community involvement [

54]. By enticing visitors eager to engage with genuine local culture and scenery, an ecomuseum may yield substantial cash from admission fees, guided tours, and ancillary activities such as workshops, culinary experiences, and lodging. The financial streams of ecomuseums are derived from several programmes, research initiatives, organisations, educational and tourism activities, and cultural and other events. These sources encompass admission tickets, and the selling of goods/services, among others. ecomuseums provide products and services such as agriculture and livestock farming, local cuisine, local art, cultural industries, thematic routes, experiential guided tours, and various recreational and educational facilities, often enhanced by new technologies and innovations [

55]. The functioning of an ecomuseum generates job prospects for local inhabitants in roles such as guides, interpreters, event coordinators, hospitality personnel, and craftspeople, thus enhancing the local economy [

56]. In the framework of ecomuseums, community maps [

57] have emerged as one of the most prevalent instruments for specialised participatory practices and the preservation of cultural heritage. Community maps serve as tools for locals to articulate their representations of cultural heritage, encompassing the environment, knowledge, and customs of the area. These procedures are essential for strengthening the consciousness and identity of a community [

58]. It also serves as a repository of memories, illuminating the aspirations individuals wish to convey to future generations. It typically comprises a cartographic representation or a composition derived from that representational logic in which the community may recognise itself. The foundation of the knowledge and comprehension may subsequently facilitate the advancement and eventual revival of culinary production and artisanal traditions, potentially enabling the conservation and promotion of the area and its products through the active engagement of the local community.

1. Worts Sustainability Model

Douglas Worts sustainability model (

Figure 1) shows how the economy and society are nested within the environment and the rest on a foundation of culture was chosen as theory to underpin this study. Worts[

59] emphasizes that ecomuseum is centred on the principles of sustainability and aid in addressing the environmental, social, economic and cultural needs of a society. A good ecomuseum initiative should be pivoted on culture. This is because the aim of ecomuseum primarily is to project the cultural identity of local communities [

26]. Culture is the single element that drives and shapes the daily activities of a society; and sustainability is ultimately a cultural matter [

60]. Also, an ecomuseum must be a socio-economic driver for development in society [

61]. This study’s understanding of of an ecomuseum resonates with the perception of Worsts that a good ecomuseum must be based solidly on projecting the place identity and culture of local communities where the ecomuseum facility is set up. More so, ecomuseum should be a driver of environmental education, inciting local people, domestic and international tourists to drive the ideals of conservation and sustainability. In addition, we assert, just like Worsts, that a good ecomuseum facility must drive socio-economic development of local communities. It should be able to create job avenues especially for local people. Hence, our adoption of Worsts sustainability model as a theoretical bedrock for this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Approach

The research approach for the study was the convergent mixed methods design because it was necessary to get a more holistic understanding [

62] of the roles of the proposed ecomuseum structure in extending the activities of the Bomfobiri wildlife sanctuary to achieve sustainable development. Both qualitative and quantitative data sets were gathered to get mutual confirmation to validate the results generated from the study [

63]. Combining mixed-methods approaches was essential to cross-validate results and strengthen the study's validity. Qualitative insights offered nuanced contextual understanding, while quantitative metrics enabled broader generalisation. This dual perspective facilitated a comprehensive analysis that inspired the ecomuseum's potential as a driver for sustainable ecotourism initiatives and community-based development.

2.2. Research Methods

The research adopted the community-based participatory method that aims at bringing together multiple study participants from diverse disciplines, including non-academic stakeholders in a transdisciplinarity positionality [

64] in the communities to shed light on the proposed ecomuseum project. The researchers were from the fields of cultural anthropology, architecture, artists, geography, nature conservation, education, hospitality, environmental science and museum studies. Others included park officers at the

Bomfobiri Wildlife sanctuary, traditional authorities, elderly people, and youth, farmers and hunters in the two forest-fringed communities, namely, Kumawu and Bodomase, that are closest to the sanctuary. They were involved in all the phases of the project from the setting of research questions through to data collection and analyses stages [

65] such that knowledge was co-created collaboratively between the researchers and the stakeholders [

66]. Principles in phenomenology that requires long engagement with the study participants were employed [

67]. Descriptive survey design under the quantitative research approach aided in the systematic collection of data from study participants including their behaviours, characteristics and perspectives on the phenomenon under investigation [

68].

2.3. Data Collection Instruments

Questionnaire that comprised of structured questions [

69]. It was categorised into three sections namely the demographic data (age, gender, region of residence, educational level and profession), perceptions on the benefits of ecotourism at the wildlife sanctuary, and perceptions on the proposed ecomuseum[

70]. Likert-scale items were used in eliciting quantitative responses. Open-ended structured interviews and descriptive focus group discussions were used to collect richer data and added textual data to the quantitative dataset [

71,

72]. The interviews included important informants who were purposefully selected. The data from the interview transcripts were thematically examined to flesh out significant themes which were discussed in relation to the research questions for the study. The quantitative and qualitative instruments were pre-tested on twenty study participants. Revisions were made for them based on the feeback from the selected study participants to enhance their reliability and clarity.\

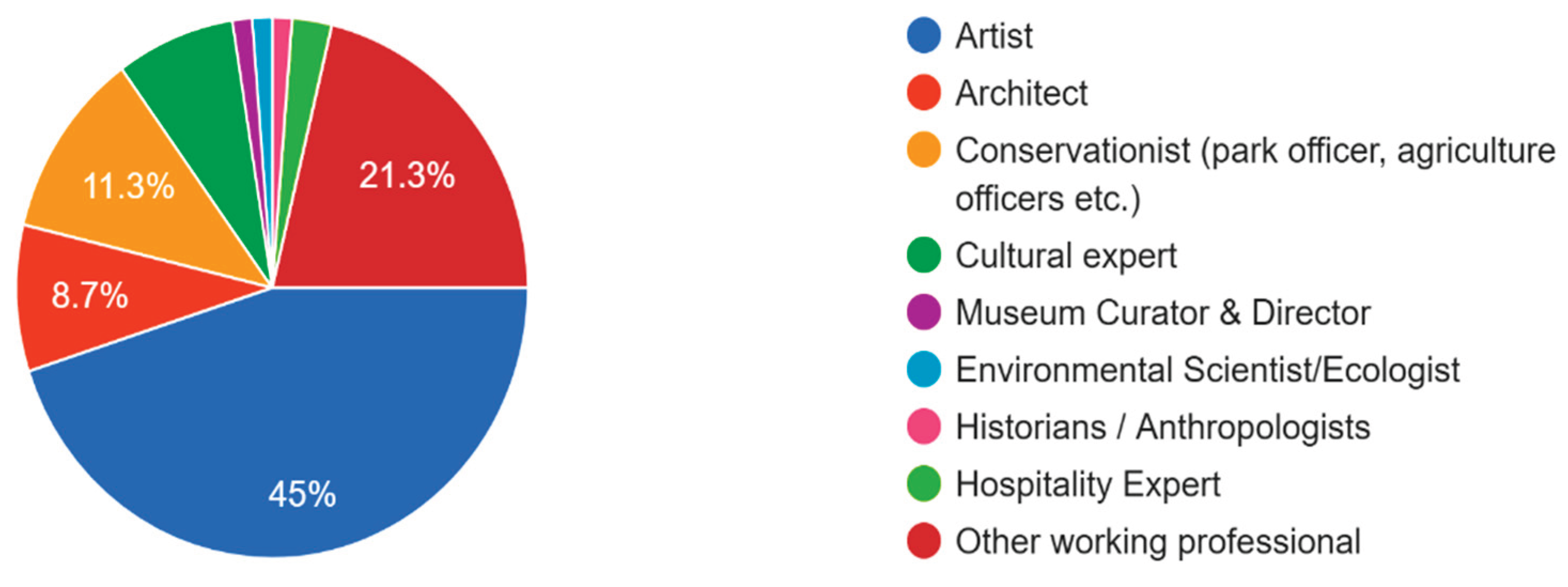

2.4. Population, Sampling and Participants

A total sample size of 97 study participants were selected using both purposive and stratified random sampling techniques. Seventeen (17) study participants (

Table 1) were purposively selected and interviewed using key informant interviews and focus group discussions for detailed information on the issues on ecomuseum investigated. The key criterion for their recruitment was that their profession should contribute to the ecomuseum discourse. On the other hand, Eighty (80) study particpants drawn using stratified random sampling answered structured questions on a researcher-designed questionnaire based on the research questions for the study. This was to triangulate the different datasets to gain a more holistic understanding of how ecomuseums could potentially aid in boosting ecotourism development in the study area. All the study particpants were drawn from different professions to engage in this transdisciplinary study. We needed to have a fair representation of all stakeholders who could potentially play crucial roles in the discourse on ecomuseum for ecotourism development in the Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary. These included artists, architects, conservationists, cultural experts, museum experts, environmental scientists, historians and anthropologists, hospitality experts and others (such as education, geography, tourism, economics, and entrepreneurship) (

Figure 2).

2.5. Data Analysis

The qualitative dataset was analyzed using the qualitative data analysis spiral [

73] which involves iterative steps of data organization, deepening, coding, categorization, and synthesis. On the other hand, the quantitative dataset was analyzed using descriptive statistics (SPSS). It provided frequency distributions, percentages, pie charts and measures of central tendency to summarise study participants’ quantitative insights.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The researchers maintained respondent anonymity by excluding names from any responses. Participants' privacy and autonomy were respected, allowing data to be gathered most conveniently. Ethical standards were upheld to collect relevant data for analysis. Also, scholarly works and data were appropriately referenced and cited, following the guidelines of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology's code of conduct to meet research objectives. Approval for the study was secured from the African Art and Culture Research Ethics Committee in the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology to guarantee compliance with ethical research standards.

2.7. Study Area

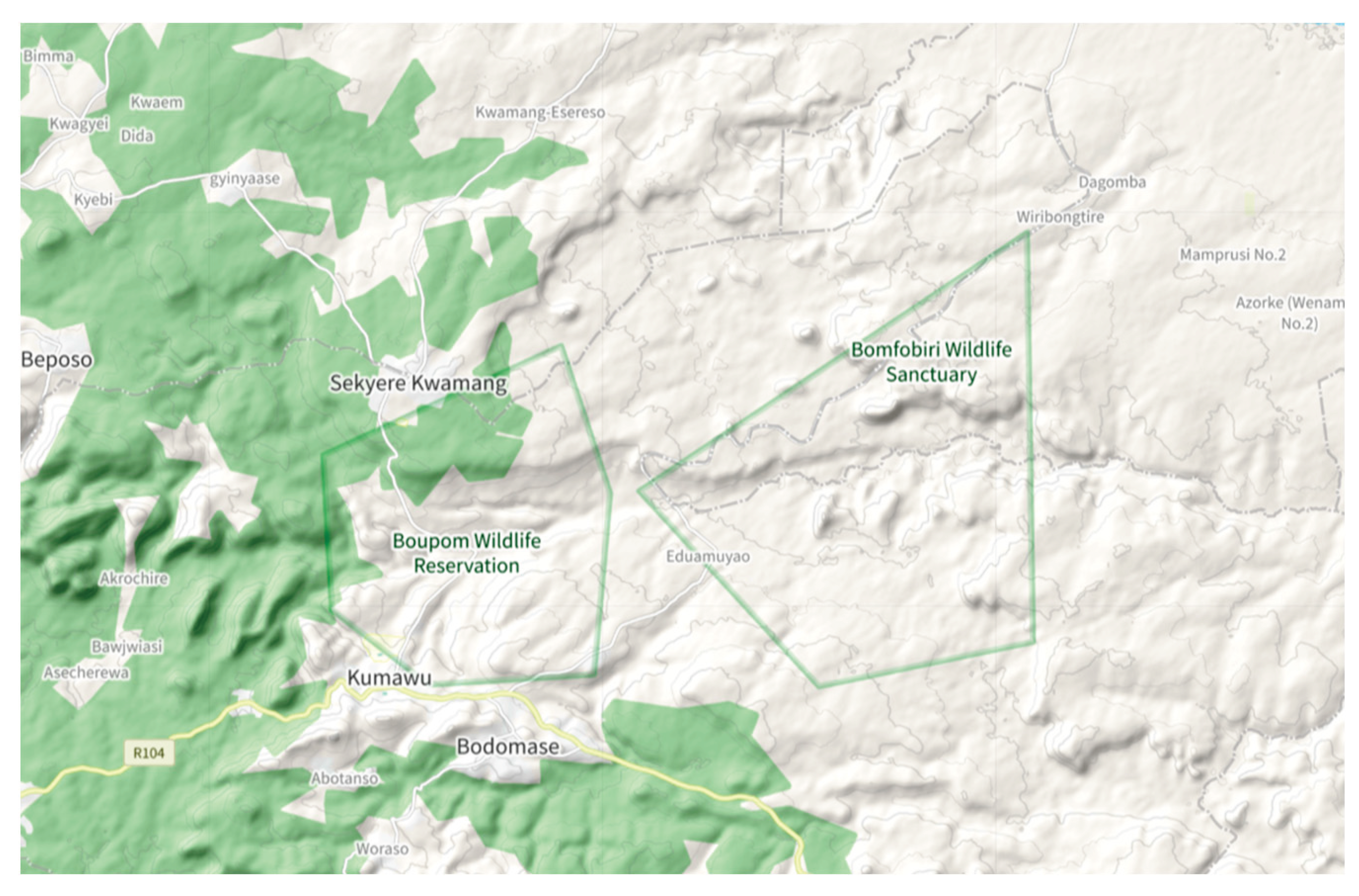

Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary (Kumawu, Ashanti)

Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary (BWS) is one of the eighteen Protected Areas managed by the Wildlife Division of Forestry Commission and one of the reserves situated within the transitional zone of the country. It covers a total area of 53km² and was carved out of the Boumfum Forest Reserve. BWS was established in 1975 by the Wildlife Reserves (Amendment) Regulations, L.I. 1022. The Sanctuary is situated between 6° 54’ to 6° 61’ N latitude and 1° 07’ to 1° 13’ W longitude and has a total area of 53 km². It is found in the Kumawu Traditional Area in the Ashanti Region, 67km North-West of Kumasi the Ashanti Regional capital (

Figure 3). Bomfobiri is one of the three designated Wildlife Sanctuaries in the country and was established mainly for its diverse topography of plants and animal species and associated ecological values. Originally about two-thirds of its vegetation was reputed to be semi-deciduous rainforest while the rest remains as typical savannah. However, the incidence of bushfires has downgraded the rainforest to a mosaic of remnant forests interspersed with savanna grasses and woodlands. Despite these circumstances the sanctuary still boasts of substantial number of animal species of conservation and research interest. Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary is surrounded by several communities. The communities can however be categorized into two: those that existed before the establishment of the reserve and those that emerged well after the reserve was created. Kumawu, Bodomase, Besoro, Temate and Drobonso are among communities in the first category. Communities in the second category tend to be situated closer to the reserve boundary, relatively smaller in size and have direct interaction with the reserve. They include Wala, Yirebontri,Wenamda, Soboyo, Dagomba,Pame-Ase, Mamprusi I, Mamprusi II, Amobia and Kokode, wenamda, Azoke,Nhyiaso, and other smaller satellite settlement areas.

There are presently 34 members of staff stationed at Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary. The staff currently are made of 1 Park Manager (professional), 1 Senior Wildlife Ranger(middle grade), 3 Principal Technical Assistant, 13 Senior Technical Assistant, 6 Technical Assistant, 9 Wildlife Guards (all technical grade) and 1 Driver. In all deliberations of the sanctuary the Park Manager in charge is answerable to the Regional Wildlife Manager station at Sunyani in the Brong Ahafo Region who intend is answerable to the Executive Director of the Wildlife Division. The total annual budget for the sanctuary, excluding staff remuneration, averages between US$ 10,000 -. US$ 25,000 subject to quarterly work plan preparation to the Executive Director of the Wildlife Division.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The State of Ecotourism Development at the Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary

The findings from the study highlight that while Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary has significant ecotourism potential, its development remains limited. Currently, the sanctuary primarily offers wildlife sightseeing without additional engaging activities that could enhance visitor experiences. During data collection, 90% of respondents indicated that the lack of extended activities, including cultural and educational components, as key contributors of low visitor retention at the

Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary. Compared to other ecotourism sites such as Mole National Park and Shai Hills, Bomfobiri lacks complementary attractions that could encourage tourists to stay longer. Despite these challenges, a key management member of the facility revealed that visitor numbers at

Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary have increased tremendously from about 800 annually to over 2,000 visitors. This underscores the need for diversified ecotourism offerings, particularly cultural heritage, and conservation education, to enhance the sanctuary’s appeal. The findings align with existing literature, which emphasizes that ecotourism development is crucial for conservation and economic growth [

1,

2]. Studies have shown that successful ecotourism sites integrate cultural and natural heritage to create immersive visitor experiences [

5,

74]. Ecotourism flourishes when it goes beyond passive sightseeing to include interactive experiences [

75]. The study findings reinforce this assertion that an ecomuseum could bridge the gap between conservation efforts and community involvement by offering visitors a richer and more engaging experience.

3.2. Revenue Generation of Ecotourism Potential at the Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary

The study findings suggest that 93.8% of respondents believed an ecomuseum would enhance ecotourism in Kumawu and its surrounding communities. Additionally, 79 respondents agreed that ecotourism has the potential to generate more revenue for the Wildlife Division and local communities. This is consistent with the argument by [

2] that ecotourism serves as an economic driver, generating employment and business opportunities. Other research also supports this notion, that ecotourism initiatives can strengthen rural economies [

18]. The survey results indicate that 79 out of 80 respondents, that is 98.8% of respondents believe that ecotourism can generate more revenue for the Wildlife Division and local communities. This implies that ecotourism has a huge potential at the

Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary. During the field study, one of the key informants revealed that:

“There is the need for infrastructure, marketing, and artifacts in place to attract people to patronize to boosts cultural heritage and educates people” (Personal Communication, May 2024).

This sentiment is supported by qualitative data, which suggest that strategic investments in infrastructure, marketing, dramatic reenactments and cultural exhibits could attract more visitors and subsequently increase revenue streams through entrance fees, tour packages, and the sale of local handicraft [

2,

76,

77]. Additionally, respondents emphasized that integrating local cultural heritage, such as indigenous festivals, guided tours, interactive exhibits, and eco-friendly accommodations are potential strategies to enhance revenue generation while preserving the sanctuary’s ecological integrity.

3.3. Ecomuseum and Ecotourism Development for Visitors’ Tourism Experience

The findings reinforce the importance of providing interactive and educational experiences for visitors. 91.3% of respondents agreed that the proposed ecomuseum would contribute significantly to local communities, and 76 out of 80 respondents believed it would effectively promote the cultural heritage of Kumawu. This supports the argument by [

78] that museums play a crucial role in conservation education and cultural sustainability. As an attempt to for ecomuseum and ecotourism development at the

Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary, the respondents indicated the need for an effective collaboration among stakeholders in the community. One of the key respondents highlighted that:

“Collaborating with community leaders to design activities (e.g., fire dance performances, craft workshops) would ensure cultural respect while appealing to domestic tourists unfamiliar with northern traditions. Also, modest promotion through social media or partnerships with travel agencies could draw curious locals. Framing these events as “living heritage” experiences paired with guided storytelling would amplify their appeal” (Personal Communication, June 2024).

During the data collection, it was identified that the ecomuseum could serve as a platform for storytelling, reinforcing the historical significance of the sanctuary and its surrounding communities. Respondents also noted that an ecomuseum would facilitate knowledge exchange and inspire conservation efforts among domestic and international tourists. With regards to eco-tourism initiatives or activities needed to be implemented at the Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary, 51% agreed to educational workshops or outreach programmes for local schools. 50% mentioned cultural experiences that involves the community, 40% opted for Adventure tourism and wild conservation tours and activities. By incorporating these interactive exhibits, guided tours, storytelling, and conservation education, the ecomuseum would offer a full visitor experience that extends beyond conventional sightseeing, aligning with studies emphasizing the need for culture-driven tourism [

79].

3.4. Ecomuseum and Ecotourism as a Cultural Heritage Preservation Tool

One of the key motivations for establishing an ecomuseum is to promote the rich cultural heritage of the host communities. The survey revealed that 71 respondents were interested in participating in cultural events or workshops organized by the proposed ecomuseum. This aligns with findings by Perera [

80], who highlighted the interconnection between nature, tourism, and cultural heritage. The study findings suggest that an ecomuseum would play a pivotal role in safeguarding and promoting the cultural heritage of Kumawu and its fringe communities [

81]. Approximately 91.3% of respondents believed that the ecomuseum could significantly contribute to local communities by fostering cultural pride and economic opportunities such as the integration of traditional festivals, craft workshops, and historical narratives. This makes it more attractive destination for domestic and international visitors [

82]. Participants advocated for incorporating local craftsmanship, traditional architecture, and indigenous storytelling into the museum’s exhibits. This approach would not only attract tourists but also provide employment and skill development opportunities for local artisans. The integration of cultural festivals, workshops, and indigenous knowledge-sharing sessions could further enhance the museum’s role as a cultural preservation hub.

3.5. Design Concept and Philosophy of the Ecomuseum

The design concept of the proposed Kumawu ecomuseum integrates the local cultural and ecological foundations through sustainable architecture that mirrors the ecology within the jurisdiction. The ecomuseum design unifies local cultural symbols of the people of Kumawu with contemporary architectural possibilities to balance place-identity and cultural heritage with modern sustainability and tourism practices. Local materials including stone, clay, bamboo, and thatch were featured in the ecomuseum design because they represent the natural bond between the region and its environment. These were interspersed with modern architectural materials such as glass. Elemental selections at the ecomuseum build upon local aesthetics in addition to encouraging visitors toward a complete cultural comprehension of the ecomuseum attributes. The ecomuseum floor plan unfolds as a storytelling sequence because each section of the ecomuseum will direct visitors to explore the history of Kumawu and its natural landscapes together with its cultural heritage. The ecomuseum arranges its exhibits to progress like traditional Kumawu practices while creating visual and emotional bond experiences for visitors. The arrangement of open courtyards with circular structures combined with natural ventilation systems in the ecomuseum’s design creates an atmosphere for peaceful reflection which connects visitors to the exhibits and surrounding outdoor areas at the same time. The ecomuseum design adopts sustainable practices by using environmentally friendly building methods together with low-impact materials for its construction. Passive cooling systems unite with rainwater collection methods along with solar panel installation to achieve a lower carbon footprint throughout the museum structure. The museum construction with local materials together with native building techniques will not only decrease transportation-related costs and emissions but also support the local economy through employment of local craftsmen.

Design elements of the ecomuseum incorporate nearby natural elements while combining indoor and outdoor areas together harmoniously. The landscape design incorporates pathways together with gardens alongside green spaces which guide visitors to appreciate the native local flora and fauna. Native plants and sustainable agricultural demonstration areas have been included in the ecomuseum structure to reinforce its commitment to environmental protection. Outdoor exhibits along with nature trails will provide visitors with direct contact to Kumawu's biodiversity to enhance their hands-on experience of the ecosystem. The essential concept guiding the ecomuseum design serves as a learning center. Visitors will experience interactive educational spaces in the design that let them directly join the learning process. Research areas along with workshop facilities and community-based learning spaces regarding conservation practices and sustainable agriculture and local traditional practices would be located on the high floors of the ecomuseum. Innovative learning spaces, such as digital and interactive exhibits, will allow visitors to engage with the region’s history and biodiversity through multimedia presentations, virtual reality experiences, and hands-on displays.

The wildlife unit at the ecomuseum functions as an essential feature which supports biodiversity protection together with environmental instruction and ecologically sustainable tours. Through immersive interaction this unit will create a space that displays the diverse local flora and fauna along with their necessary ecological value, so visitors understand the critical need for protection.

Figure 4.

Frontal View of the Proposed Bomfobiri Ecomuseum.

Figure 4.

Frontal View of the Proposed Bomfobiri Ecomuseum.

Figure 5.

Aerial view of the proposed Bomfobiri ecomuseum.

Figure 5.

Aerial view of the proposed Bomfobiri ecomuseum.

Figure 6.

Exhibition and Gift Shop.

Figure 6.

Exhibition and Gift Shop.

Figure 7.

Production Unit.

Figure 7.

Production Unit.

Figure 8.

Ecomuseum Library.

Figure 8.

Ecomuseum Library.

Figure 9.

Virtual Interactive session of the Bomfobiri Ecomuseum.

Figure 9.

Virtual Interactive session of the Bomfobiri Ecomuseum.

Figure 10.

Wildlife Unit of the Bomfobiri Ecomuseum.

Figure 10.

Wildlife Unit of the Bomfobiri Ecomuseum.

3.6. Design and Construction of an Ecomuseum for Domestic and International Appeal

Respondents provided insightful comments regarding the design and construction of the proposed ecomuseum. The study findings suggest that respondents preferred a design that incorporates local materials such as bamboo, clay, and wood to reflect the natural environment and cultural heritage of Kumawu. Sustainable architectural features, including passive cooling systems, solar panels, and rainwater harvesting, were also recommended. As a means to solicit ideas for the best practice in terms of ecotourism construction, a key community opinion leader pronounced that:

“I will go for a roofing that is fire-proof because the place is known for wildfires so the materials must withstand fire. It’s always good to use our own materials to construct it. Some local materials like bamboo, wood, thatch, and these local materials will be sustainable in the next 30 to 40 years depending on how we ourselves manage the place. The design is nice and very beautiful” (Personal Communication, June 2024).

These findings align with the principles of ecomuseology, which emphasise sustainable development and community involvement [

24,

83]. Also, 80% of the respondents emphasised the need for incorporating guided tours, interactive storytelling exhibits, and digital learning spaces. This would further enhance the museum’s appeal, attract diverse audiences and encouraging prolonged visitor engagement [

83]. Additionally, the proposed ecomuseum’s integration with conservation initiatives and wildlife education aligns with international best practices for eco-tourism [

27]. Its design should balance sustainability and durability, ensuring long-term viability. The project would require private-sector partnerships to overcome funding limitations. The construction of Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary would serve as a cultural and educational hub, creating jobs and enhancing visitors’ experiences. By implementing these strategies, Bomfobiri could become a premier ecotourism destination in Ghana.

4. Conclusions

Ecomuseums offer a sustainable and community-centred alternative to conventional museum models. By ensuring local involvement and cultural continuity, they protect heritage and stimulate social and economic benefits for the regions they serve. The study’s results highlight a strong public consensus on the economic potential of ecotourism, with an overwhelming majority believing it can generate substantial revenue for the wildlife division. The proposed ecomuseum is expected to attract visitors primarily for educational and cultural experiences, reinforcing its role as both a learning hub and a heritage preservation center. The findings suggest that effective implementation of ecomuseums can be a powerful tool for heritage conservation, education, and community empowerment. However, for ecomuseums to thrive, strong institutional support, interdisciplinary collaborations, innovative management strategies, effective policies, and community dedication are essential in ensuring the longevity and success of ecomuseums.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, DA; methodology, DA, OP.; software SK, MAE; validation, DA, OP, RN, MAE and SK.; formal analysis, EJP; investigation, DA, OP, RN, SK; resources, RN, SK, DA; data curation, DA, OP; writing—original draft preparation, DA, OP, MAE, and EJP.; writing—review and editing, DA, OP, RN, MAE and SK.; visualization, OP, DA.; supervision, DA.; project administration, DA, OP; funding acquisition, RN All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Department of Educational Innovations in Science and Technology, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana (protocol code DEIST00122023 and 04/01/2023) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data for the study will be made available by the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support received from the study participants including the park officers at the Bomfobiri wildlife sanctuary, traditional chiefs, elders and people of Kumawu.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Drumm, A. , & Moore, A. (2005). An introduction to ecotourism planning (Vol. 1). Nature Conservancy.

- Anup, K.C. Ecotourism and Its Role in Sustainable Development of Nepal. INTECH 2016, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (2009). World Heritage Cultural Landscapes: A Handbook for Conservation and Management.

- Labadi, S. , Giliberto, F., Rosetti, I., Shetabi, L., & Yildirim, E. (2021). Heritage and sustainable development goals: Policy guidance for heritage and development actors. International Journal of Heritage Studies. https://kar.kent.ac.uk/89231/ T. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Adom, D. The place and voice of local people, culture, and traditions: a catalyst for ecotourism development in rural communities in Ghana. Scientific African 2019, 6, e00184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagul, A.H.B.P. (2009). The success of Ecotourism Sites and Local Community Participation in Sabah, Malaysia. D Phil. Tourism Management Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington.

- Kiper, T. (2013). Role of ecotourism in sustainable development. InTech.

- Pardo-de-Santayana, M. , & Macía, M.J. The benefits of traditional knowledge. Nature 2015, 518, 487–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, M. Rural tourism entrepreneurship survey with emphasis on eco-museum concept. Civil Engineering Journal 2018, 4, 1403–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollgraaff, H. Museums and cultural landscapes: the ICOM-SA and ICOMOS-SA initiative as a case study. South African Museums Association Bulletin 2017, 39, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, S. , Vogt, C. & Jun, S.H. (2004). Heeding the Call for Heritage Tourism. Parks & Recreation, (September), pp. 38–47.

- Corral, Ó.N. , & Fernández, J.F. The importance of ecomuseums and local knowledge for a sustainable future: The La Ponte–Ecomuseu project. Ecomuseums and Climate Change, ed. N Borrelli, P Davis, R Dal Santo 2022, 283-302.

- Li, C. (2024). Collaborating for Museum Innovation: Technological, Cultural, and Organisational Innovation in Spanish Museums, Taylor & Francis.

- Duarte Cândido, M.M. (2024). Museums facing their social and environmental responsibilities: towards an ethical and sustainable model–training and research. In Museums facing their social and environmental responsabilities: towards and ethical and sustainable model. Cycle de débats en ligne.

- Brown, K. Museums and local development: An introduction to museums, sustainability and well-being. Museum International 2019, 71, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCRC, 2004 Community-based Ecotourism Programme (CBEP): Final Report. Accra: Nature Conservation Research Centre, 2004. NCRC Ghana, www.ncrc-ghana.org/publications/cbep-final-report.

- Dorobantu, M.R. , & Nistoreanu, P. (2012). Rural tourism and ecotourism–the main priorities in sustainable development orientations of rural local communities in Romania. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/31480/.

- Amuquandoh, F.E. , Boakye, K.A. & Mensah, E.A. Ecotourism Experiences of International Visitors to the Owabi Wildlife Sanctuary, Ghana. Ghana Journal of Geography 2011, 3, 250–284. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, P. Community-based ecotourism projects as living museums. Journal of Ecotourism 2020, 19, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornhoff, M. , Sothmann, J. N., Fiebelkorn, F. & Menzel, S. Nature Relatedness and Environmental Concern of Young People in Ecuador and Germany. Front Psychol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Canavese, G. , Gianotti, F. & de Varine, H. Ecomuseums and geosites community and project building. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks 2018, 6, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mensch, P.J.A. Magpies on Mount Helicon. In: Scharer, M. (ed.) Museum and Community. Vevey: ICOFOM 1995, 25, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Rivière, G.H. The ecomuseum – An evolutive definition. Museum International 1985, 37, 182–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P. (2007). Ecomuseum and sustainability in Italy, Japan and China: Adaptation through implementation. In Knell, S.J., et al. (eds) Museum revolutions: how museums change and are changed. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 198–214.

- Jamieson, W. An ecomuseum for the Crowsnest pass: Using cultural resources as a tool for community and local economic development. Plan Canada 1989, 29, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, P. (2011). Ecomuseums: a sense of place. London and New York: Leicester University Press.

- Su, D. The concept of the ecomuseum and its practice in China. Museum International 2008, 60, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydemir, D.L.R. (2017). “Safeguarding Maritime Intangible Cultural Heritage: Ecomuseum Batana, Croatia.” In The Routledge Companion to Intangible Cultural Heritage, edited by M. L. Stefano and P. Davis. New York: Routledge.

- Keyes, A.J. (1992). Local participation in the Cowichan and Chemainus Valleys Ecomuseum: An exploration of individual participatory experience. Master thesis. The University of British Columbia.

- Cai, Q. & Yao, T. From open-air buildings museum to ecomuseum: On the progress of protective idea and method of vernacular historical settlement heritage sites. Applied Mechanics and Materials 2012, 174, 2416–2419. [Google Scholar]

- Stokrocki, M. The ecomuseum preserves an artful way of life. Art Education 1996, 49, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.E. La Maison de la Photographie Tafza Berber Ecomuseum. Marrakesh, Morocco. African Arts 2012, 45, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, C. The ecomuseum in Fresnes: Against exclusion. Museum International 2003, 53, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, M. Representing heritage and loss on the Brittany Coast: Sites, things and absence. International Journal of Heritage Studies 2012, 18, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P. Ecomuseum and the representation of place. Rivista Geografica Italiana 2009, 116, 483–503. [Google Scholar]

- Galla, A. Culture and heritage in development: Ha Long Ecomuseum, a case study from Vietnam. Humanities Research 2002, 9, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Doğan, M. The ecomuseum and solidarity tourism: a case study from northeast Turkey. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 2019, 9, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. , & Selim, G. Cultivating ecomuseum practices in China: shifting from objects to users-centred approaches. International Journal of Heritage Studies 2024, 30, 1211–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Laishun, A. & Gjestrum, J. The ecomuseum in theory and practice. The first Chinese ecomuseum established. Nordisk Museologi 2016, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P. (1999). Ecomuseums: A Sense of Place. London: Leicester University Press.

- Hodges, D.J. Museums, anthropology, and minorities: In search of a new relevance for old artifacts. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 1978, 9, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokrocki, M. The ecomuseum preserves an artful way of life. Art Education 1996, 49, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavese, G. , Gianotti, F., and de Varine, H. 2018. Ecomuseums and geosites community and project building. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks 2018, 6, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, M. Representing heritage and loss on the Brittany Coast: Sites, things and absence. International Journal of Heritage Studies 2012, 18, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, C. , Corinto Luigi, G. & Teresa, G. Limits and Potentialities of Ecomuseums in Sicily, Between Tourist Exploitation and Cultural Heritage Preservation. In: 5th International Congress on “Science and Technology for the Safeguard of Cultural Heritage in the Mediterranean Basin”, Istanbul, edited by S. Tardiola, and G. Pingue 2011, 442–450. Centro Copie I’Istantanea.

- Hubert, F. Ecomuseums in France: Contradictions and distortions. Museum International 1985, 37, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, M. & Timothy, D.J. Beyond Tourism and Taxes: The Ecomuseum and Social Development in the Ak-Chin Tribal Community. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 2019, 18, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, G.C. , Sperlich, T., Worts, D., Rivard, R. & Teather, L. (). Fostering Cultures of Sustainability Through Community-Engaged Museums: The History and Re-Emergence of Ecomuseums in Canada and the USA. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, N. & Davis, P. (). How Culture Shapes Nature: Reflections on Ecomuseum Practices. Nature and Culture 2012, 7, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsane, G. (2006). From ‘Outreach’ to ‘In reach’: How Ecomuseum Principles Encourage Community Participation in Museum Processes. In Communication and Exploration: Papers of the International Ecomuseum Forum, Guizhou, China, edited by D. Su, 155–171. Beijing: Forbidden City press.

- Corsane, G. Using Ecomuseum Indicators to Evaluate the Robben Island Museum and World Heritage Site. Landscape Research 2006, 31, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boylan, P. Is Yours a ‘classic’ musuem or an Ecomuseum/’new’musuem? Museums Journal 1992, 92, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Badia, F. , and Deodato, G. 2015. “Strategic profiles of ecomuseum management and community involvement in Italy,” in ENCATC, The Ecology of Culture: Community Engagement, Co-creation, Cross Fertilization, Book Proceedings, 6th Annual Research Session, Bruxelles: Encatc, 31–46.

- Badia, F. , and Donato, F. 2023. Management perspectives for ecomuseums effectiveness: a holistic approach to sociocultural development of local areas. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Polic. /: https. [CrossRef]

- Vrettakis, E. , Katifori, A., Kyriakidi, M., Koukouli, M., Boile, M., Glenis, A., Petousi, D., Vayanou, M., & Ioannidis, Y. Personalization in Digital Ecomuseums: The Case of Pros-Eleusis. Applied Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Negacz, K. , & Para, A. The ecomuseum as a sustainable product and an accelerator of regional development. The case of the Subcarpathian Province. Economic and Environmental Studies 2020, 14, 51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, B. Constructing community through maps? Power and praxis in community mapping. Prof. Geogr. 2006, 58, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaran, A. , & Michelutti, E. Landscape as ‘working field’ for territorial identity in Friuli Venezia Giulia ecomuseums action. Geoj. Libr. 2021, 127, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worts, D. Culture and museums in the winds of change: the need for cultural indicators. Cult. Local Govern. 2011, 3, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrow, D. Museums and culture. Prairie Forum 2019, 40, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Sutter, G.C. & Fletcher, A.J. Highlights and Future Directions for Ecomuseum Development in Saskatchewan. Prairie Forum 2019, 40, 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. & Plano Clark, V.L. (2011). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (2nd Ed.). Sage Publications.

- Molina-Azorin, J. & Cameron, R. The application of mixed methods in organisational research: a literature review. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 2010, 8, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Breckwoldt, A. , Lopes, P.F.M. & Selim, S.A. Look who’s asking – reflections on participatory and transdisciplinary marine research approaches. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, D. , Openjuru, G., Odoch, M., Nono, D. & and Ongom, S. When the Guns Stopped Roaring: Acholi Ngec Ma Gwoko Lobo. Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement 2020, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnhout, E. The politics of co-production: participation, power, and transformation. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2020, 42, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraenkel, J.R. , Wallen, N.E., & Hyun, H.H. (2012). How to desIgn and evaluate research in educatIon (8th ed.). New York.

- Creswell, J.W. & Creswell, J.D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social Research Methods (5th ed.). London: Oxford University Press.

- Tajfel, H. (1978). Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. Academic Press.

- Hollander, J.A. The Social Contexts of Focus Groups. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 2004, 33, 602–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggleby, W. What about Focus Group Interaction Data? Qualitative Health Research 2005, 15, 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D. & Usher, R. (2011). Researching Education: Data Methods and Theory in Educational Inquiry (2nd Ed.). London.

- Lockwood, M. Social impacts of tourism: an Australian regional case study. International Journal of Tourism Research 2006, 10, 365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, S. , Vogt, C. , Hyun, S., & Nicholls, J. Heeding the call for heritage tourism: More visitors want an “experience” in their vacations—something a historical park can provide. Parks & Recreation (Ashburn) 2004, 39, 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Peprah Mensah, E.J. , Adom, D. & Kquofi, S. Historical Narratives of the Eight Akan Clan Systems Using Museum Theater: The Case of Prempeh II Jubilee Museum, Ghana. 2024. Journal of Urban Culture Research 2024, 28, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R. Improving engagement between tourists and staff at natural and cultural heritage tourism sites: exploring the concept of interpretive conversations. Tourism Recreation Research 2017, 43, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuqin, D. The role of natural history museums in the promotion of sustainable development. Museum International 2008, 60, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, T. (2007). The strategic Role of Cultural and Heritage Tourism in the Context of a Mega- event: The case of 2010 Soccer World cup. MCom Tourism Management Thesis, The Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of Pretoria.

- Perera, K. (2013). The Role of Museums in Cultural and Heritage Tourism for Sustainable Economy in Developing Countries. 2013 International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage.

- Canavese, G. , Gianotti, F., & De Varine, H. Ecomuseums and geosites: Community and project building. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2018, 6, 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, B. (2002). Cultural Tourism and Museums. Proceedings of the International Council of Museums Conference, 2002, Seoul, Korea. Lord Cultural Resources, 2002, www.lord.ca/Media/Artcl_CltTourismMSeoulKorea_2002.pdf.

- Vrettakis, E. , Katifori, A. In , & Ioannidis, Y. Digital storytelling and social interaction in cultural heritage-an approach for sites withreduced connectivity. In Proceedings of the Interactive Storytelling: 14th International Conference on Interactive Digital Story-telling, ICIDS 2021, Tallinn, Estonia, 7–10 December 2021; Proceedings 14; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg,Germany, 2021; pp. 157–171. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).