1. Introduction

Urban traffic congestion is a major and growing concern in many developing cities, particularly across sub-Saharan Africa, where rapid population growth, urbanization, and motorization often outpace infrastructure development [

1,

2]. The resulting inefficiencies reduce productivity, increase fuel consumption, worsen air quality, and lower overall urban livability. In Kampala, Uganda’s capital, average traffic speeds drop to 11 km/h during peak hours, and commuters spend up to 240 hours annually in gridlock, leading to economic losses exceeding USD 800 million per year [

3,

4]. These losses underscore the urgent need for intelligent urban mobility solutions that can optimize road network utilization and improve commuter experience.

Globally, intelligent transportation systems (ITS) and data-driven urban mobility frameworks have emerged as key enablers of smart city development [

5,

6]. Advances in Machine Learning (ML), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies have facilitated the collection and analysis of massive traffic datasets for predictive modeling, congestion detection, and real-time route optimization [

7,

8,

9]. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of ML-based models, such as Random Forests, Support Vector Machines, and Neural Networks in predicting traffic flow and suggesting efficient routes [

10,

11]. However, these applications have largely been concentrated in data-rich, high-income urban environments, leaving a research and implementation gap in low-resource cities where data sparsity, limited sensing infrastructure, and uncoordinated traffic management systems prevail [

12,

13].

In Kampala, existing traffic control mechanisms remain largely manual and reactive, relying on limited surveillance data and static traffic light systems. The absence of real-time, data-driven decision support tools hampers effective routing, resulting in persistent congestion and inefficient use of available road networks [

14]. Bridging this gap requires localized, context-aware systems that integrate real-time geospatial data with predictive modeling techniques to deliver dynamic traffic solutions tailored to local conditions.

This study proposes a data-driven intelligent traffic routing system designed for Kampala City to enhance smart urban mobility. The system integrates machine learning with real-time geolocation data, using a Random Forest Classifier trained on temporal and spatial traffic patterns to predict the least congested route between two points. Data are sourced from the Google Maps Directions API and processed through a Node.js backend, enabling real-time user interaction via a geo-enabled interface.

The results demonstrate that the integration of machine learning algorithms and geospatial analytics can effectively enhance traffic management in resource-constrained environments. The study concludes that data-driven intelligent routing systems can provide a scalable and adaptable framework for improving mobility efficiency, reducing congestion, and advancing the goals of smart city development in Kampala and similar urban centers across East Africa.

1.1. Problem Statement

Kampala City faces persistent and unpredictable traffic congestion, resulting in significant delays, reduced productivity, increased fuel consumption, and elevated air pollution levels. The inefficiency of the current road network not only frustrates commuters but also undermines economic performance and urban sustainability [

15]. A key contributor to this challenge is the absence of real-time traffic information and predictive intelligence, which limits drivers’ ability to plan and adapt their routes efficiently [

2].

To address this challenge, the present study proposes the development of a data-driven intelligent traffic prediction and routing system capable of providing accurate, real-time congestion forecasts [

5]. By integrating machine learning with geospatial traffic data, the system aims to support commuters, drivers, and transportation authorities in making informed routing decisions, thereby enhancing mobility efficiency, reducing congestion, and advancing smart urban mobility within Kampala City.

2. Literature Review

Traffic modeling and route optimization have evolved significantly, from early statistical and time-series models to advanced machine learning, deep learning, and geo-spatial integration frameworks. Each methodological generation offers unique trade-offs in accuracy, interpretability, data requirements, and computational cost. This section reviews key milestones and contemporary developments that have shaped traffic prediction research, highlighting the gap this study seeks to address within low-resource urban contexts such as Kampala.

2.1 Statistical and Time-Series Models

Before the advent of artificial intelligence, researchers primarily treated traffic flow as a temporal stochastic process. Okutani and Stephanedes pioneered the use of the Kalman filter for real-time freeway volume forecasting, demonstrating how measurement and prediction could be adaptively fused for dynamic traffic estimation [

5]. Similarly, Davis and Nihan introduced non-parametric regression models for short-term traffic flow prediction, relaxing rigid distributional assumptions and outperforming traditional linear models in flexibility and responsiveness [

6]. Building on these foundations, Ghosh et al. extended the framework to multivariate time-series analysis, capturing correlated traffic flows across multiple road links to represent network-wide dependencies within a unified model [

7]. These classical approaches remain valuable for their interpretability, yet their accuracy declines under non-linear, non-stationary, or data-scarce conditions typical of developing cities.

2.2 Machine Learning Ensembles

With the expansion of sensor networks and urban mobility data, machine learning ensembles, notably Random Forests (RF) and Gradient Boosting Machines, gained prominence for their balance of accuracy, robustness, and interpretability. Zarei et al. developed a context-aware Random Forest model that effectively differentiated peak from off-peak traffic, showing resilience to sensor noise and missing data [

8]. Similarly, Yan and Shen applied Random Forests to predict traffic accident severity, illustrating the algorithm’s capability to model non-linear feature interactions and provide feature-importance metrics relevant to traffic dynamics [

9]. These studies underscore the adaptability of ensemble methods in handling complex mobility data, making them suitable for low-resource environments with heterogeneous data quality.

2.3 Deep and Graph-Based Models

The rise of deep learning architecture enabled simultaneous modeling of spatial and temporal dependencies in traffic networks. Zheng et al. introduced the Graph Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory (GC-LSTM) model, combining graph convolutions over road networks with LSTM-based temporal encoders to outperform CNN–RNN hybrids on large-scale datasets [

10]. Li et al. later advanced this approach through a spatio-temporal graph neural network (ST-GNN) that jointly learned from road graph topology and temporal embeddings, substantially improving short-term speed and flow prediction accuracy [

11]. More recently, Ji et al. proposed a self-supervised graph augmentation framework capable of capturing cross-regional heterogeneity and temporal shifts, achieving state-of-the-art results on benchmark datasets [

12]. Despite their accuracy, these deep architectures often require large, labeled datasets and high computational resources, posing challenges for deployment in developing urban contexts.

2.4 Geospatial APIs and Route Optimization

Commercial routing platforms such as Google Maps have demonstrated the power of large-scale data fusion for real-time navigation. Lau documented how Google combines anonymized mobile device traces, historical traffic patterns, and graph neural networks to achieve estimated time of arrival (ETA) accuracies exceeding 97% [

13]. Kelareva detailed how the Google Maps Directions API exposes these predictive capabilities through parameters such as the Traffic Model, allowing developers to request optimistic or pessimistic travel-time estimates for anticipated departures [

14]. These platforms highlight the transformative potential of geospatial APIs but also reveal a dependency on proprietary data sources and global-scale infrastructure, which limits local adaptability and transparency.

2.5 Traffic Modeling in Low-Resource Contexts

Traffic modeling in sub-Saharan Africa presents distinct challenges, including sparse sensor coverage, erratic congestion patterns, and limited infrastructure capacity. Okiza et al., applied the Moving Observer Method in Kampala to derive a non-linear density flow relationship, revealing pronounced weekday versus weekend variations in traffic flow [

3]. Hamza et al., used unsupervised clustering to identify peak-hour congestion hotspots, emphasizing the influence of driver behavior, informal road usage, and ad hoc blockages on Kampala’s traffic dynamics [

16]. While these studies provide valuable empirical insights, few have integrated machine learning-based predictive routing tailored to such low-resource settings. This gap motivates the present study, which introduces a lightweight, real-time Random Forest-based routing framework that leverages geospatial API data to enhance mobility efficiency in Kampala and similar urban environments.

3.0 Materials and Methods

This section presents the end-to-end process for predicting and recommending the least congested route between two locations within Kampala City, Uganda. The proposed system integrates traffic data acquisition, congestion classification, machine learning model development, and real-time deployment through a Node.js web application.

Figure 1 summarizes the overall workflow from data collection to system deployment.

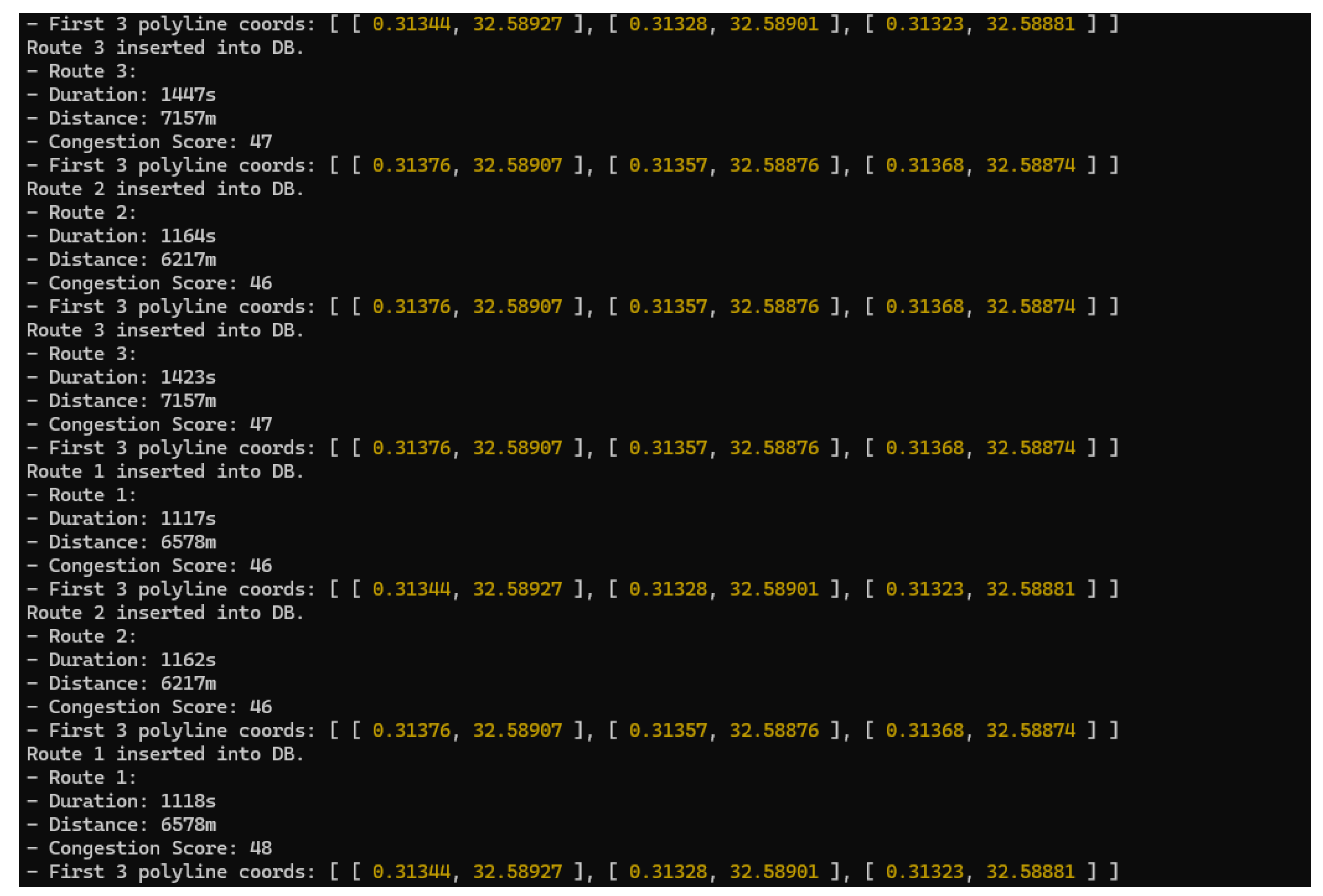

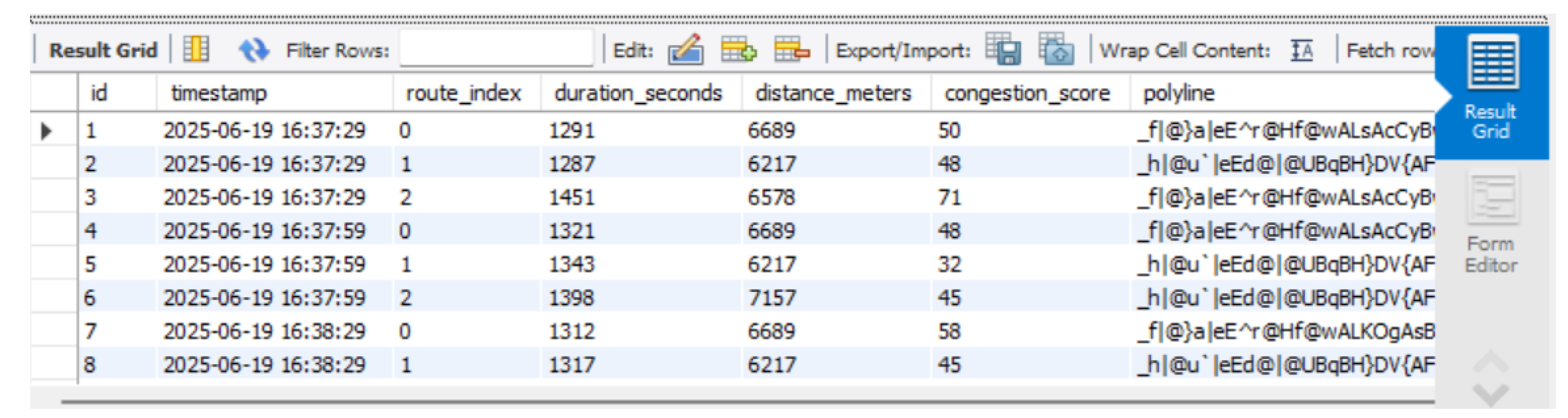

3.1 Traffic Data Collection

Traffic data were collected using the Google Maps Directions API, which provides multiple route alternatives between specified origin, destination pairs.

To capture temporal variations in traffic flow, API requests were executed at different times of the day and across all days of the week. For each route, metadata such as estimated duration, distance, and traffic-adjusted travel time were extracted. The API’s

duration_in_traffic field, which combines historical and live data through Google’s internal predictive traffic models, served as the basis for congestion estimation [

13,

14]. Each response record was parsed and inserted into a PostgreSQL database schema named co

ngestion_manager, as illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

3.2 Congestion Classification Schema

To quantify traffic congestion, a congestion score was computed as the ratio of duration_in_traffic to free-flow travel time. Routes with congestion scores exceeding a predefined threshold were labeled “congested”, while others were labeled “non-congested.”

This binary classification served as the target variable for supervised model training. The threshold was empirically tuned through exploratory analysis of temporal traffic distributions across the dataset.

3.3 Feature Engineering and Dataset Preparation

The final dataset incorporated both temporal and route-specific features, including: Day of the week; Time of day (morning, midday, evening); Route index; Distance and duration metrics; Congestion score.

All categorical variables were numerically encoded, and the data were divided into training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets. Feature selection prioritized temporal relevance, as traffic conditions in Kampala show marked differences between weekdays and weekends and between peak and off-peak periods [

3]. Normalization was applied to distance and duration attributes to stabilize model performance.

3.4 Model Training and Evaluation

A Random Forest Classifier (RFC) was implemented due to its robustness to noisy data, capacity to model non-linear relationships, and interpretability [

9]. The RFC employs an ensemble learning mechanism that aggregates multiple decision trees to yield optimal predictions [

8].

The model was trained to predict congestion status based on engineered features, particularly the congestion_score, hour_of_day, and day_of_week. Performance was evaluated using standard classification metrics: Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and ROC-AUC. Analysis of feature importance was also conducted to identify key predictors influencing congestion outcomes.

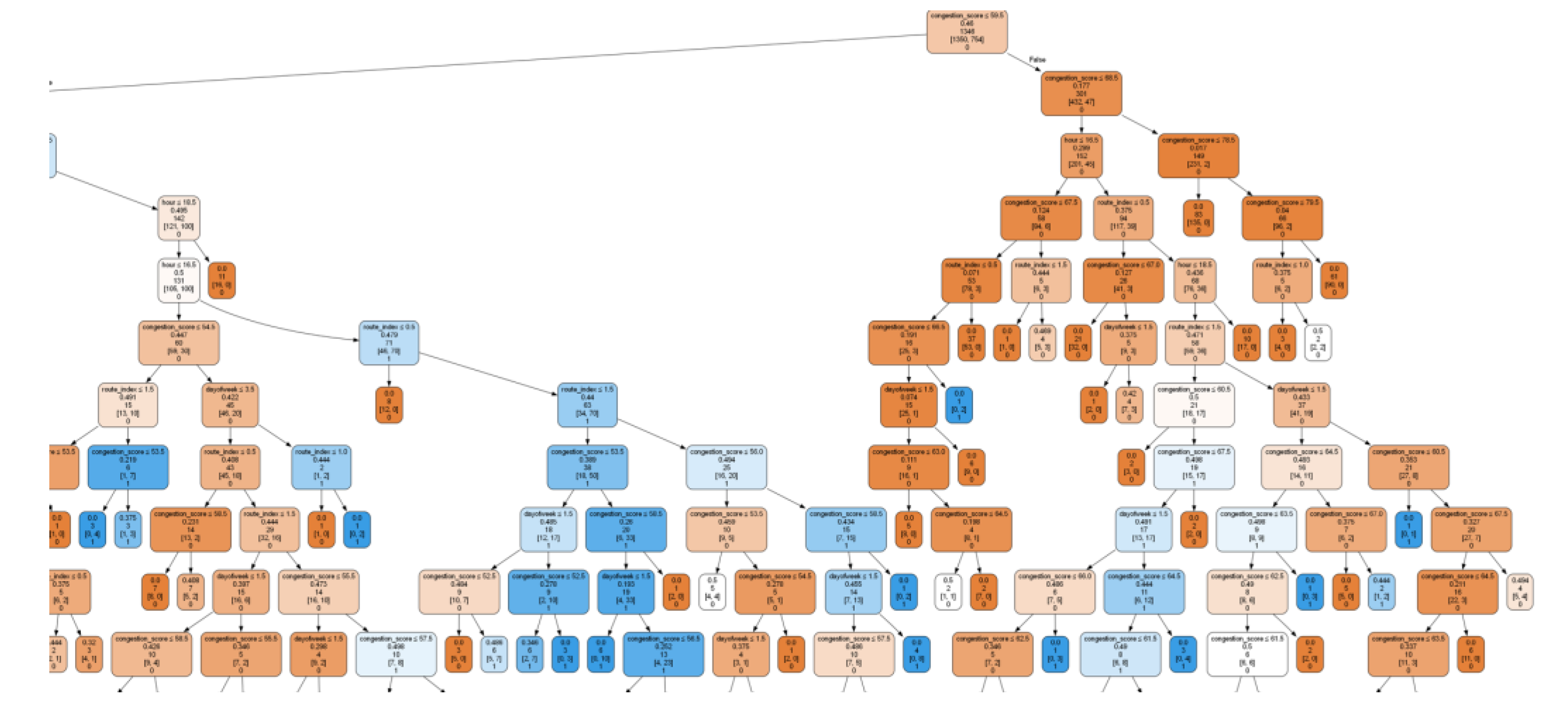

Figure 3 below shows a section of a decision tree from the Random Forest Classifier illustrating decision-making rules based on

congestion_score and temporal features. Each node in the decision tree represents:

Splitting Condition: Determines the next node transition (e.g., congestion_score ≤ 59.5).

Gini Impurity: Quantifies the purity of samples at the node (e.g., 0.46).

Sample Count: Number of training samples reaching the node (e.g., 1346).

Sample Distribution: Representation of class counts [1350, 754].

Predicted Class: The resulting output—0 = Congested Route, 1 = Least Congested Route.

The Random Forest achieved balanced performance across all metrics, confirming its suitability for real-time traffic prediction in low-resource contexts.

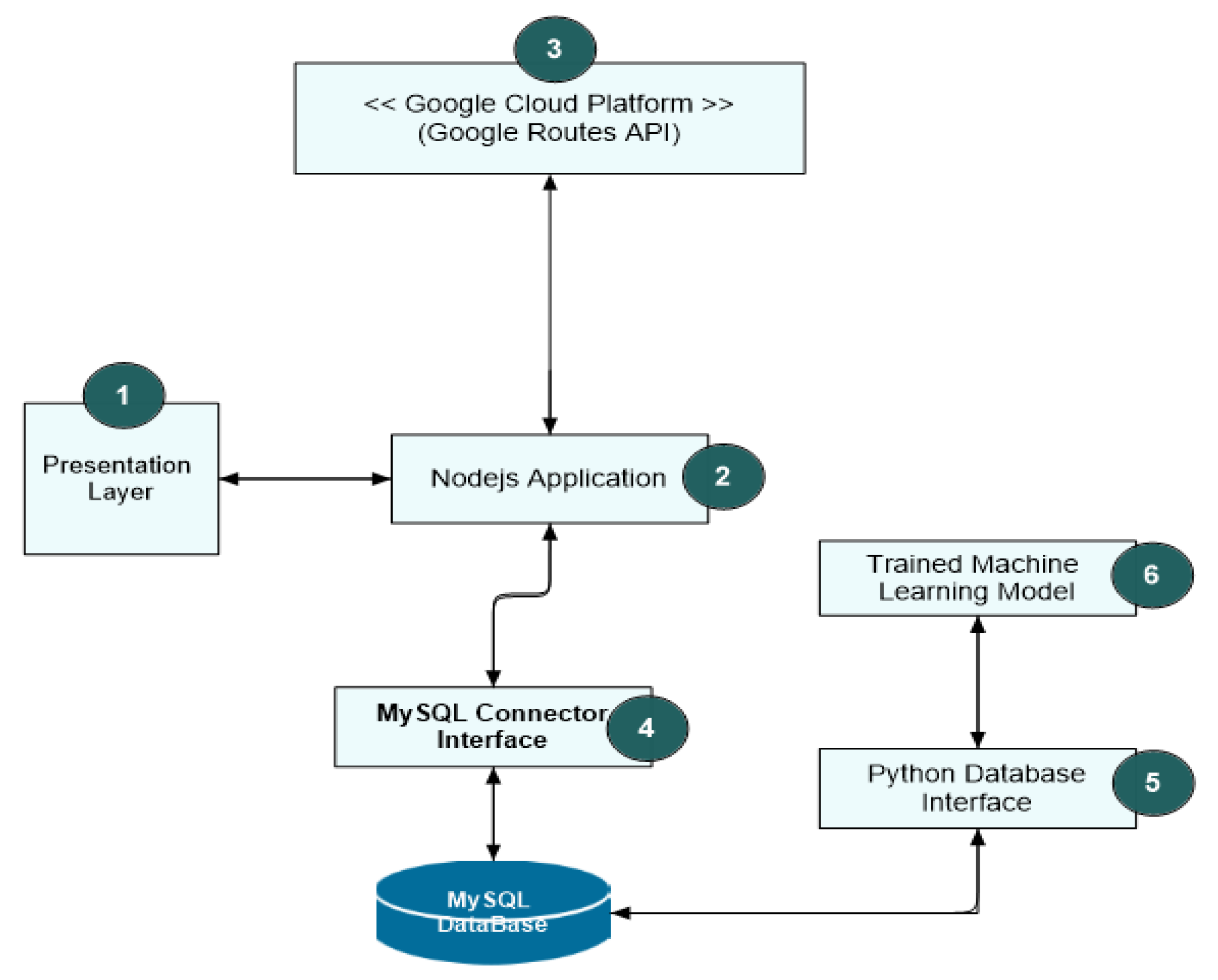

3.5 System Deployment Architecture

The trained RFC model was serialized using Joblib and exposed via a lightweight

Python-based REST API. The system architecture consisted of three layers:

Frontend Layer: Developed with Pug templates and the Google Maps JavaScript API to visualize routes and overlay predicted congestion.

Backend Layer: Built on Node.js, responsible for handling client geo-location requests and asynchronous communication with the prediction API.

Database Layer: Managed using PostgreSQL, storing route histories, congestion scores, and model predictions for continuous retraining.

This integration enabled users to request routes and receive real-time congestion-aware recommendations directly through a web interface. The deployment demonstrated responsiveness, scalability, and interoperability across multiple devices.

4 Results

This section presents the predictive performance of the Random Forest Classifier (RFC), interpretation of the results, and system deployment outcomes. Subsections detail the classifier’s evaluation metrics, model interpretability, and operational validation within Kampala’s traffic context.

4.1. Classification Performance

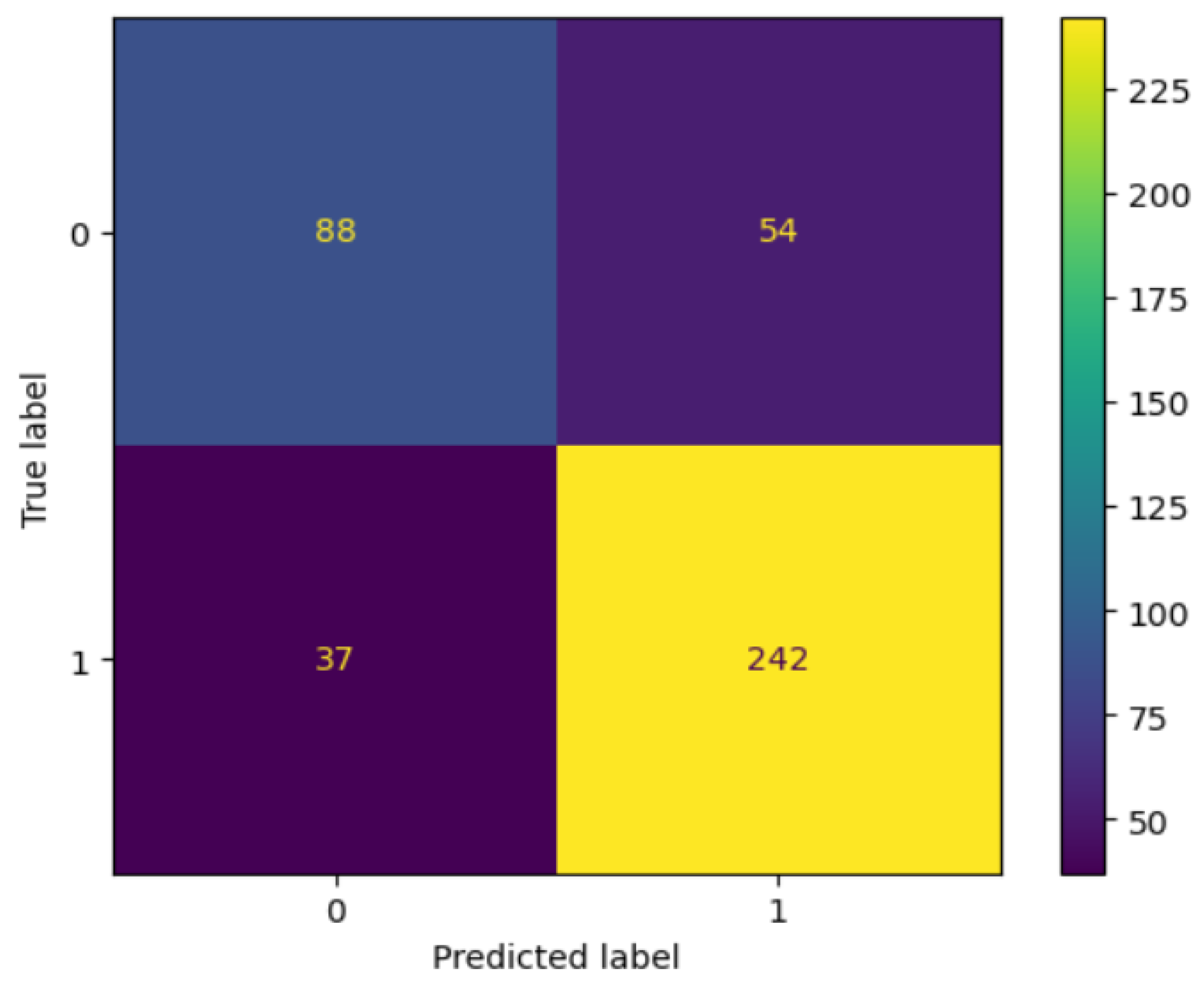

The classifier achieved an overall test accuracy of 78.4% on 421 samples. As shown in

Table 1, it performed best in predicting non-congested (Class 1) routes, with a precision of 0.82, recall of 0.87, and F1-score of 0.84. In contrast, congested routes (Class 0) showed a lower recall of 0.62 and an F1-score of 0.66, indicating some tendency to misclassify high-traffic alternatives as viable options [

19].

4.2. Bias and Class Distribution

The RFC showed a mild bias toward predicting non-congested routes, reflecting the dominance of clear-flow samples within the dataset. Slightly reduced recall for congested routes likely stems from feature overlaps during transitional time windows (e.g., pre-rush-hour). Nevertheless, the macro and weighted averages indicate that the classifier maintains balanced generalization and minimal overfitting [

19].

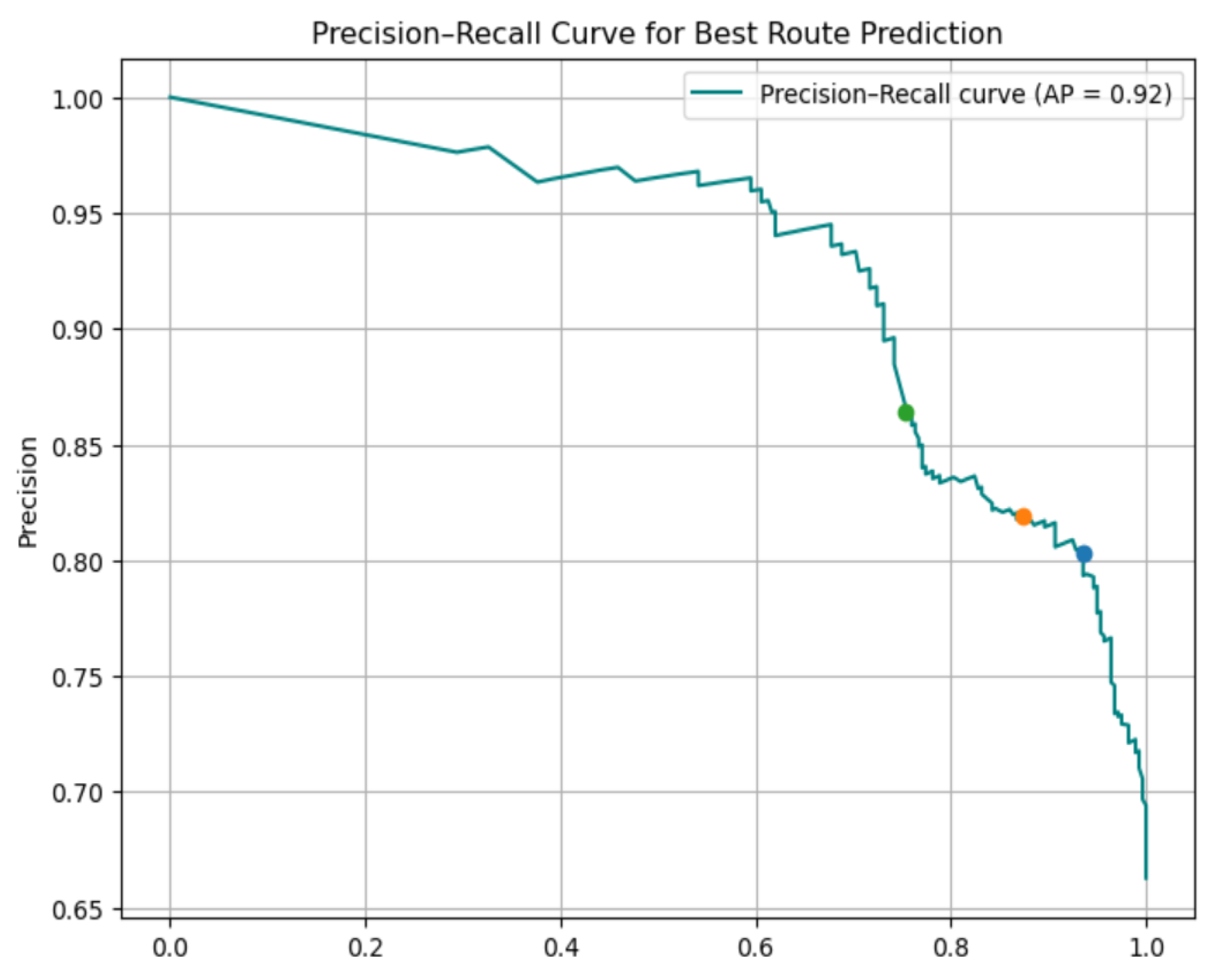

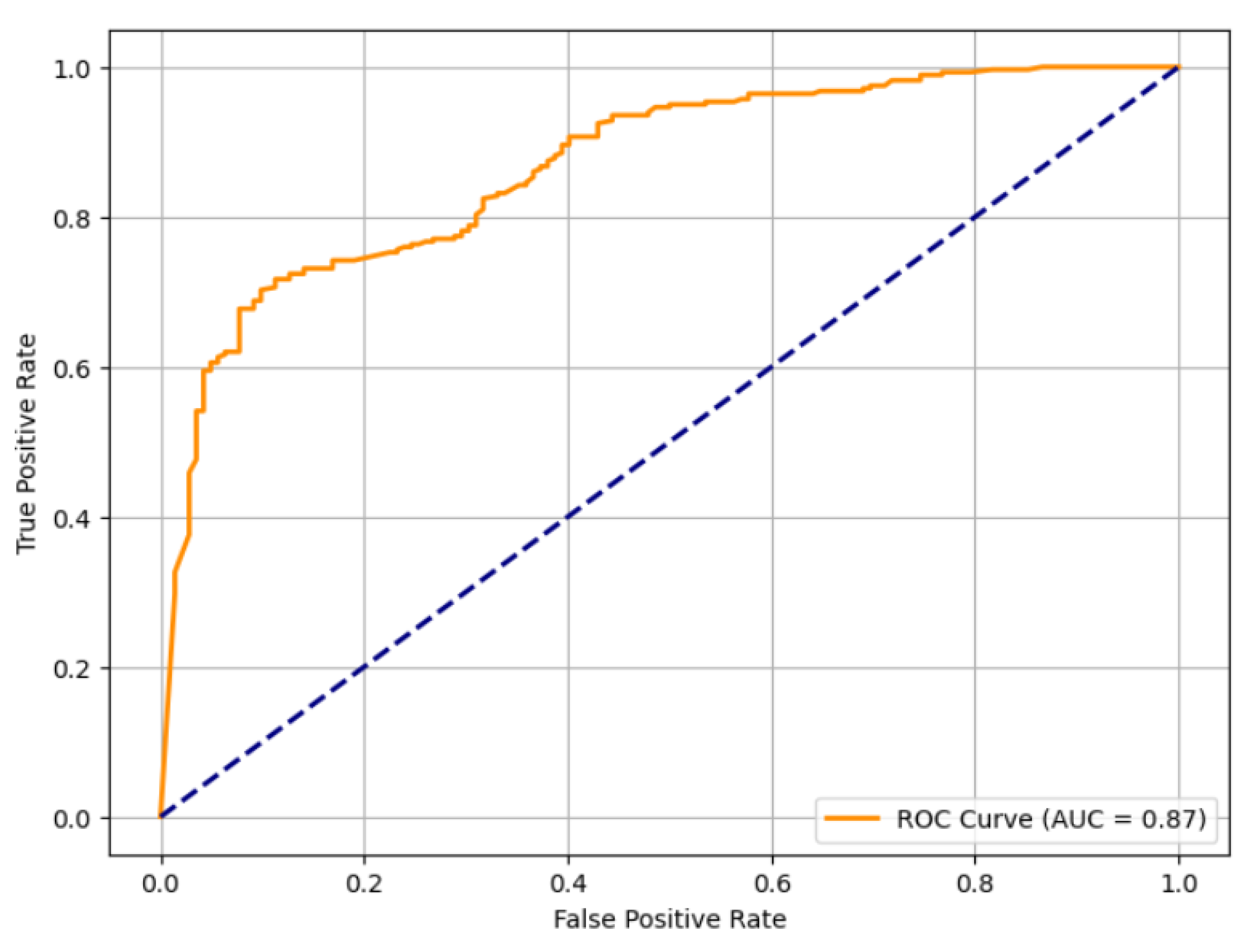

4.3. Visual Assessment

Graphical evaluation provided deeper insight into the model’s predictive reliability. The confusion matrix (

Figure 4) shows that most misclassifications occurred when congested routes were labeled as non-congested. The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve (

Figure 5) achieved an AUC = 0.85, demonstrating high class separability and strong discriminative power [

3].

Figure 6.

Precision Recall Curve.

Figure 6.

Precision Recall Curve.

4.4. Feature Impact and Interpretability

Feature importance analysis revealed that time of day and day of week were the dominant predictors, reflecting Kampala’s recurring congestion patterns. Secondary variables, such as route index and travel duration delta, also contributed to route differentiation [

19]. The model’s interpretability confirms its practical utility for adaptive, data-driven routing recommendations.

4.5. Real-Time Deployment Behavior

The trained RFC was integrated within the Node.js backend and successfully deployed for real-time inference. During live operation, predicted congestion levels closely aligned with live Google Maps traffic data, validating both the model and its implementation pipeline [

17,

20,

21].The backend efficiently filtered optimal routes, returning results to users within seconds, demonstrating low-latency performance and scalability suitable for urban traffic systems.

5. Discussion

This section interprets the model’s operational behavior, its impact on real-time routing, and constraints observed during deployment.

5.1. System Flow

When a user specifies origin and destination coordinates, the Node.js backend asynchronously requests alternative routes from the Google Maps Directions API. The returned metadata, including distance, duration, and congestion estimates, is processed by a Python microservice hosting the serialized RFC model. The predicted results are then relayed to the frontend interface for visualization [

6].

Figure 7.

High-level system component architecture and data flow.

Figure 7.

High-level system component architecture and data flow.

5.2. Prediction Logic and Visual Integration

Predictions labeled Class 1 (non-congested) are visually highlighted in green, whereas Class 0 (congested) are rendered in red or dashed overlays. This color-coded scheme improves interpretability and allows users to make rapid, informed routing decisions [

6].

5.3. Field Deployment Observations

Field testing confirmed that the system consistently prioritized routes with low congestion scores and shorter travel times. During transitional traffic periods (e.g., evening rush hours 4–9 p.m.), the model favored slightly longer yet historically stable routes. This conservative bias reduced unexpected detours and enhanced user trust in predictions [

7].

4.4. System Responsiveness and Limitations

The end-to-end framework exhibited near real-time responsiveness under normal network conditions. However, three factors occasionally introduced latency:

Google Maps API throttling or rate limits;

Local internet instability;

Unforeseen traffic disruptions (accidents, road closures, or severe weather).

These limitations underscore the need for adaptive retraining, streaming data ingestion, and redundant fallback APIs to sustain reliability in evolving traffic environments [

8].

6. Conclusions

This study developed a machine learning-based framework for real-time, congestion aware route optimization tailored to Kampala City, Uganda. Integrating Google Maps Directions API metadata with a Random Forest Classifier, the model achieved 78.4% accuracy, excelling in identifying non-congested routes (precision = 0.82; recall = 0.87; F1 = 0.84) [

1].

The framework effectively supports smart-mobility applications in developing cities, offering a scalable, interpretable, and cost-efficient approach to traffic prediction. Lower recall for congested routes (62%) highlights the need for additional contextual variables such as weather, events, and infrastructure conditions [

2].

Future work will focus on:

7. Patents

No patents have been generated from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H. Orieba, L. Tamale, and N. Nzeuliro; Methodology, H. Orieba, L. Tamale, and N. Nzeuliro; Formal Analysis, H. Orieba; Data Curation, H. Orieba; Writing, Original Draft Preparation, H. Orieba and N. Nzeuliro; Writing, Review and Editing, L. Tamale; Supervision, L. Tamale. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets and model scripts supporting the findings of this study will be made publicly available in Zenodo and GitHub repositories. Openly accessible Zenodo Dataset used for training the Model

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15706104 and the Route Optimization Nodejs application

https://github.com/HedwigOrieba/LeastCongestionRoutePredictor.git that powered the backend logic needed to collect and consolidate all system workflows together. These resources were premises for data acquisition and system implementation in this work.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the Google Maps Routes API for access to structured traffic data and the Zenodo dataset (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.15706104) used for model training. Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lee, D.O. The Real Cost of Traffic Jam, Potholes in Kampala. Daily Monitor, 11 January 2024. Available online: https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/oped/commentary/the-real-cost-of-traffic-jam-potholes-in-kampala-4487964 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- International Growth Centre. The Economic Cost of Traffic Congestion in Greater Kampala; International Growth Centre: Kampala, Uganda, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Okiza, H.; Muhwezi, L.; Okello, J.O.; Awichi, R.O.; Savannah, N. Mathematical Modeling of Traffic Flow in Kampala City Using the Moving Observer Method. East African Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 2024, 7, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Context Neutral. Real-Time Traffic Monitoring Systems with Node.js: Architecture, Best Practices, and Case Studies. Context Neutral Blog, 5 May 2024. Available online: https://www.contextneutral.com/traffic-monitoring-systems-architecture-best (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Sattarzadeh, A.R.; Kutadinata, R.J.; Pathirana, P.N.; Huynh, V.T. A novel hybrid deep learning model with ARIMA Conv-LSTM networks and shuffle attention layer for short-term traffic flow prediction. Transportmetrica A: Transport Science 2025, 21(1), 2236724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.A.; Nihan, N.L. Nonparametric Regression and Short-Term Freeway Traffic Forecasting. Journal of Transportation Engineering 1991, 117(2), 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.; Basu, B.; O’Mahony, M. Multivariate Short-Term Traffic Flow Forecasting Using Time-Series Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2009, 10(2), 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, N.; Ghayour, M.A.; Hashemi, S. Road Traffic Prediction Using Context-Aware Random Forest Based on Volatility Nature of Traffic Flows. In Proceedings of the 5th Asian Conference on Intelligent Information and Database Systems (ACIIDS), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 18–20 March 2013; pp. 196–205. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, M.; Shen, Y. Traffic Accident Severity Prediction Based on Random Forest. Sustainability 2022, 14(3), 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, X. GC-LSTM: Graph Convolution Embedded LSTM for Dynamic Network Link Prediction. Applied Intelligence 2022, 52(9), 7513–7528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, W.; Fan, H. A Spatio-Temporal Graph Neural Network Approach for Traffic Flow Prediction. Mathematics 2022, 10(10), 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Wang, J.; Huang, C.; Wu, J.; Xu, B.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y. Spatio-Temporal Self-Supervised Learning for Traffic Flow Prediction. In Proceedings of the 37th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; pp. 4356–4364. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, J. Google Maps 101: How AI Helps Predict Traffic and Determine Routes. Google Blog, 3 September 2020. Available online: https://blog.google/products/maps/google-maps-101-how-ai-helps-predict-traffic-and-determine-routes (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Kelareva, E. Predicting Future Travel Times with the Google Maps APIs. Google Cloud Blog, 11 November 2015. Available online: https://cloud.google.com/blog/topics/inside-google-cloud/predicting-future-travel-times-with-the-google-maps-apis (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Shafan, T. & Ssentongo, K. L. (2025) “Reducing Congestion in The Metropolitan Area: A Case of Greater Kampala Metropolitan Area”, East African Journal of Engineering, 8(1), pp. 116-126. [CrossRef]

- Hamza, S.; Yahya, U.; Kasule, A.; Kasagga, U.; Pembe, F.; Kamoga, I. Characterizing Peak-Time Traffic Jam Incidents in Kampala Using Exploratory Data Analysis. Journal of Transportation Technologies 2023, 13(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Developers. Google Maps JavaScript API Documentation. 2025. Available online: https://developers.google.com/maps/documentation/javascript/overview (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; Vanderplas, J.; Passos, A.; Cournapeau, D.; Brucher, M.; Perrot, M.; Duchesnay, É. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira, S.; Arsenio, E.; Barateiro, J.; Henriques, R. Data Analytics to Advance the Inference of Origin–Destination in Public Transport Systems: Tracing Network Vulnerabilities and Age-Sensitive Trip Purposes. European Transport Research Review 2025, 17(1), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orieba, H. Kampala Traffic Optimization Dataset (v1.0) [Data Set]. Zenodo 2025. [CrossRef]

- Orieba, H.; Route Optimization Node. js App [Source Code]. GitHub. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/HedwigOrieba/LeastCongestionRoutePredictor.git (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Tamale, L.; Ssebuggwawo, D.; Mirembe, D.P.; Mirugwe, A.; Lubega, J.T. Optimizing Deep Learning Models for Aflatoxin Detection in Agricultural Products: A Case Study of Groundnuts. African Journal of Rural Development 2025, 10(2), 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Dorling Kindersley. Simply Artificial Intelligence; DK Publishing: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).