Submitted:

14 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Nanoparticles Preparation

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Cell Viability

2.4. Macrophage Apoptosis

2.5. ROS Production

2.6. Caspase-3 Activities

2.7. Inflammatory Cytokines

2.8. Western Blotting (WB)

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

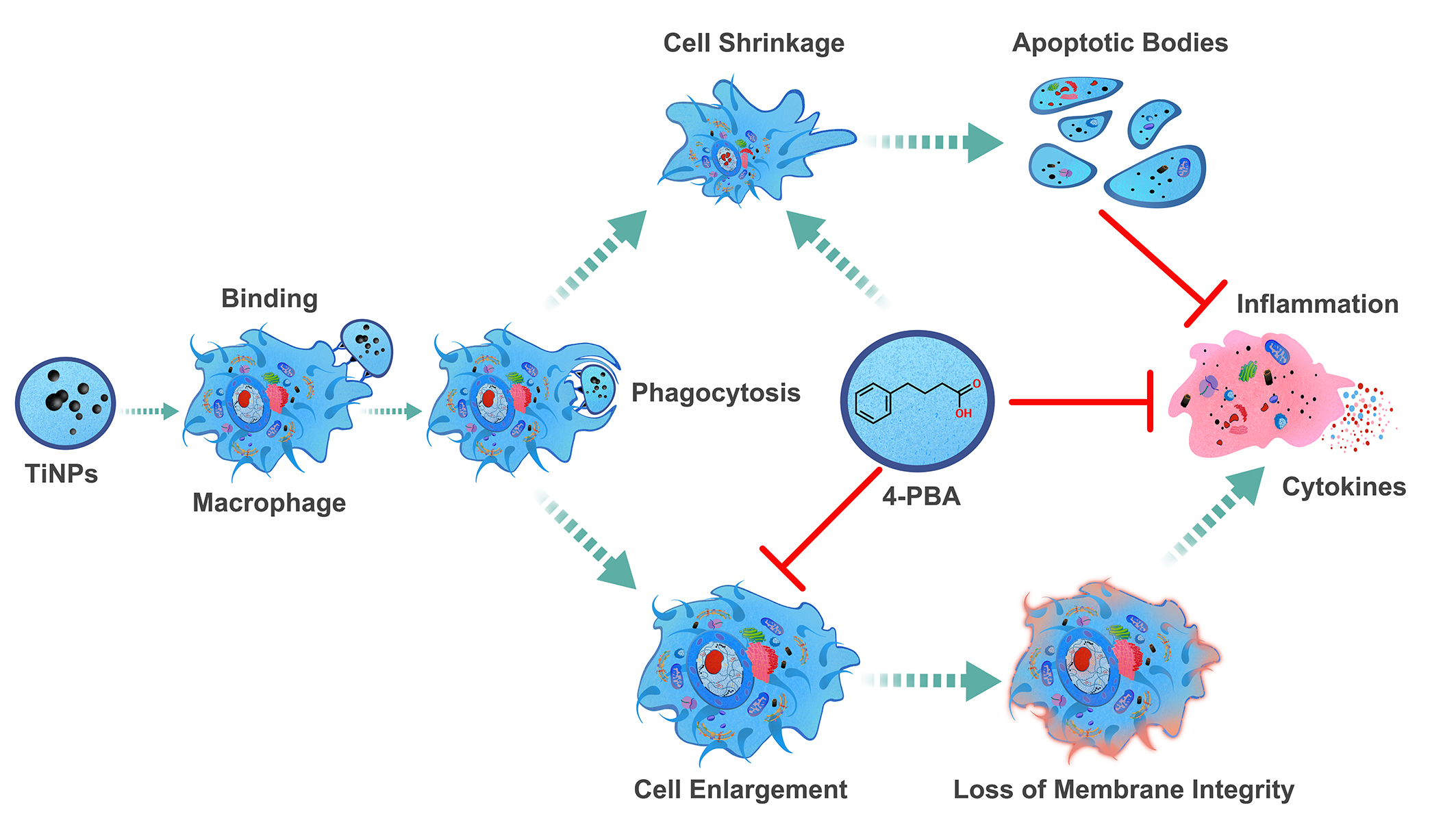

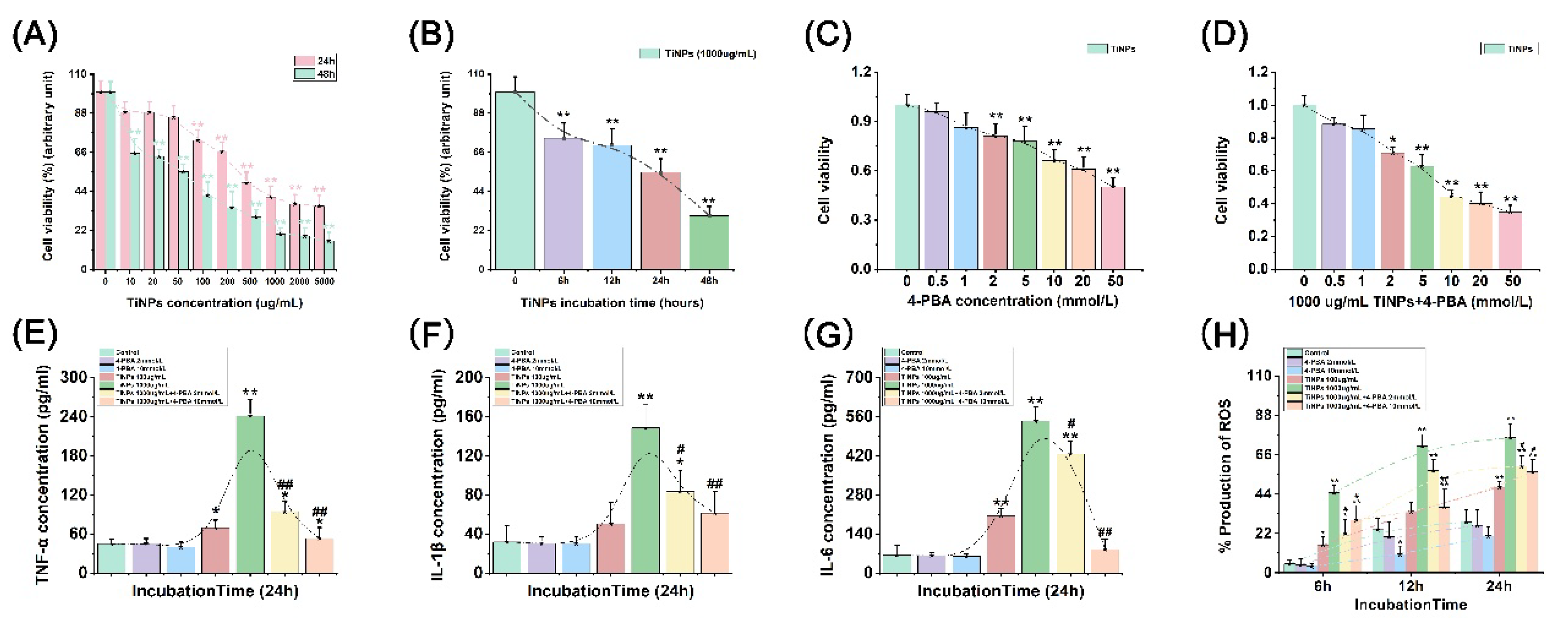

3.1. The Effect of 4-PBA on TiNP-Induced Macrophage Viability

3.2. The Suppressive Effect of 4-PBA on TiNP-Induced Inflammation in Macrophages

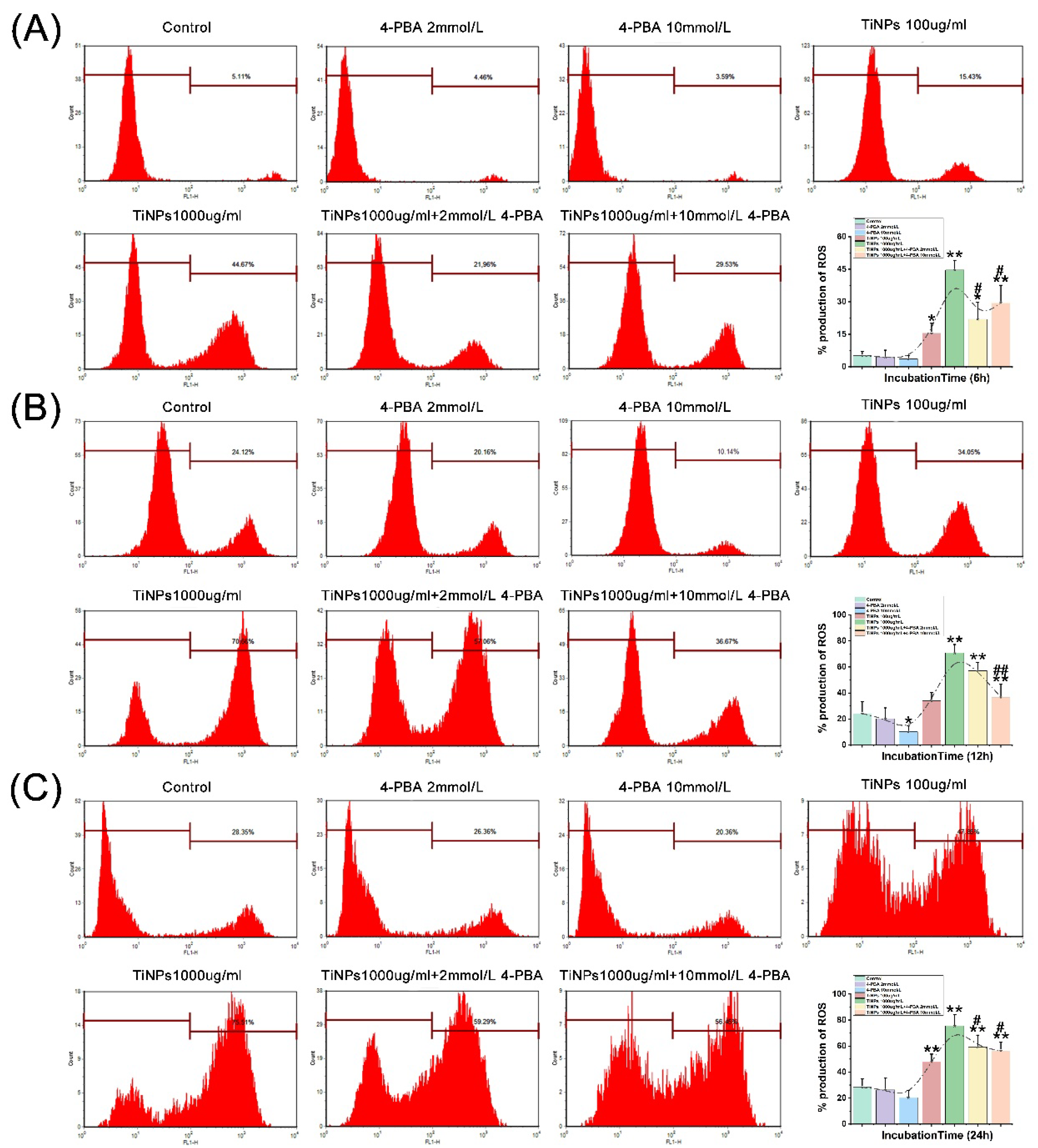

3.3. The Alleviative Effect of 4-PBA on TiNP-Induced ROS Production in Macrophages

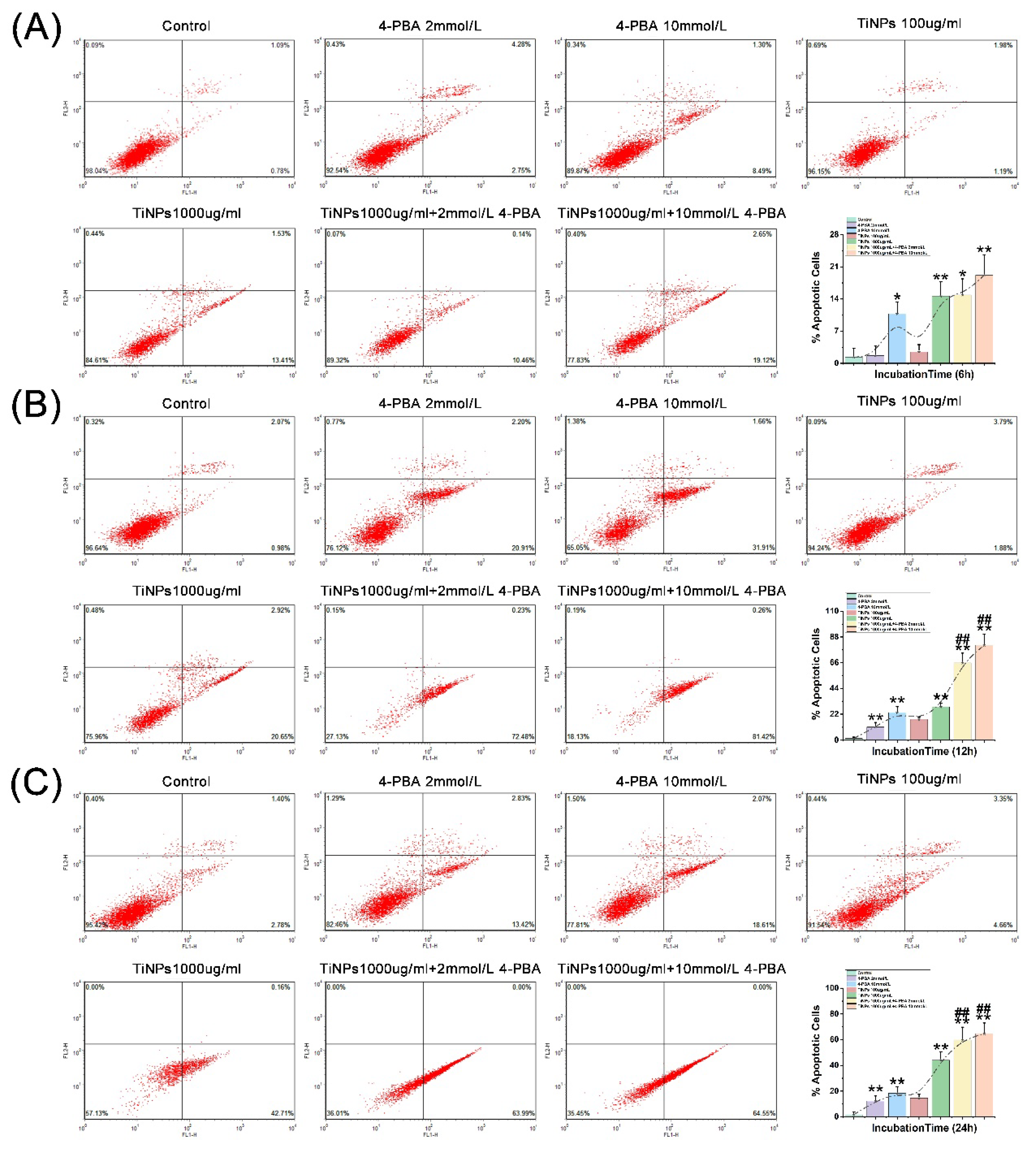

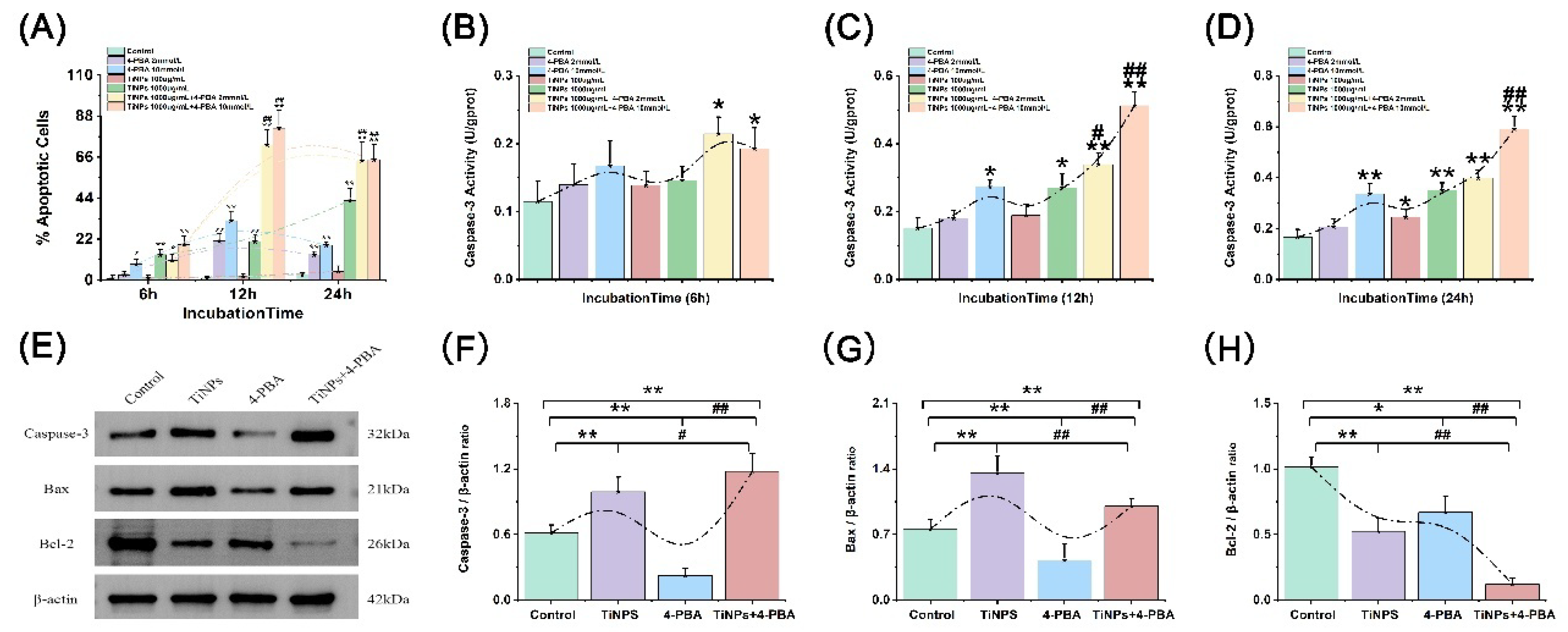

3.4. The Facilitatory Effect of 4-PBA on TiNP-Induced Macrophage Apoptosis

3.5. The Effect of 4-PBA on TiNP-Induced Apoptotic Regulatory Proteins in Macrophage Apoptosis

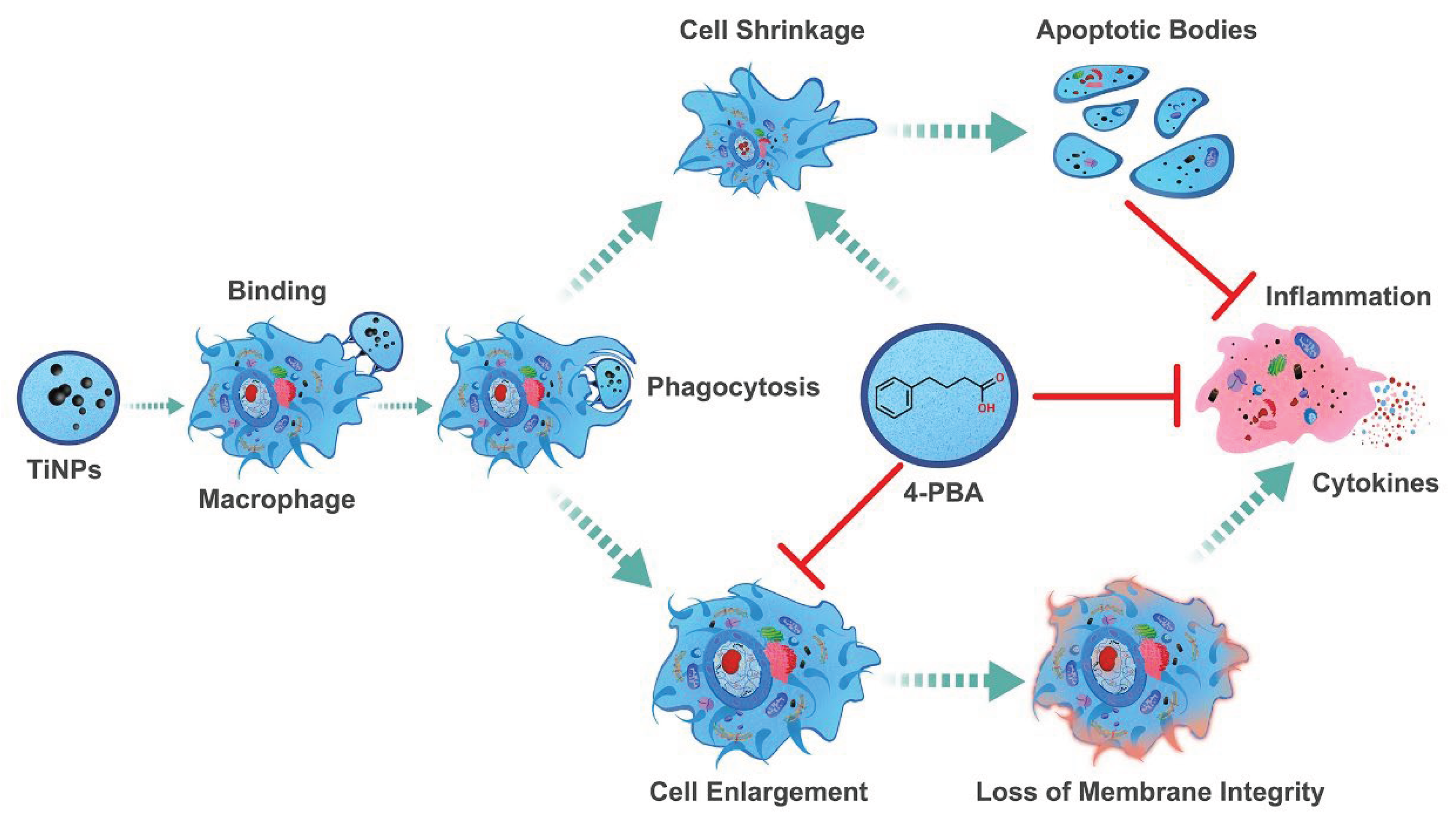

4. Discussion

4.1. The Role of Wear Particle in Macrophage-Mediated Inflammatory Injury

4.2. The Role of Macrophages in Wear Particle-Induced Aseptic Osteolysis

4.3. The Crosstalk Between Macrophage Apoptosis and Inflammation in Periprosthetic Microenvironment

4.4. The Protective Role of Chemical Chaperone 4-PBA in Wear Particle-Induced Macro-Phage-Mediated Inflammatory Injury

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Abbreviations

| 4-PBA | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| TiNP | Titanium Nanoparticle |

| TiNPs | Titanium Nanoparticles |

| ERS | Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| UPR | Unfolded Protein Response |

| UCDs | Urea Cycle Disorders |

References

- Gibon, E.; Amanatullah, D.F.; Loi, F.; Pajarinen, J.; Nabeshima, A.; Yao, Z.; Hamadouche, M.; Goodman, S.B. The biological response to orthopaedic implants for joint replacement: Part I: Metals. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B 2017, 105, 2162–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, J.; Vaculova, J.; Goodman, S.B.; Konttinen, Y.T.; Thyssen, J.P. Contributions of human tissue analysis to understanding the mechanisms of loosening and osteolysis in total hip replacement. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 2354–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.B.; Gallo, J. Periprosthetic Osteolysis: Mechanisms, Prevention and Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, A.; Avula, I.; Sahoo, S.N.; Biswal, S.; Mandal, S.; Musthafa, M.; Roy, S.; Nandi, S.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Roy, M. Functional medium entropy alloys for joint replacement: An atomistic perspective of material deformation and a correlation to wear, corrosion, and biocompatibility. Acta Biomater. 2024, 187, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eger, M.; Hiram-Bab, S.; Liron, T.; Sterer, N.; Carmi, Y.; Kohavi, D.; Gabet, Y. Mechanism and Prevention of Titanium Particle-Induced Inflammation and Osteolysis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panez-Toro, I.; Heymann, D.; Gouin, F.; Amiaud, J.; Heymann, M.F.; Cordova, L.A. Roles of inflammatory cell infiltrate in periprosthetic osteolysis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1310262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Liang, S.; Chen, M.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, G.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.; et al. Enhanced Osteolysis Targeted Therapy through Fusion of Exosomes Derived from M2 Macrophages and Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Modulating Macrophage Polarization. Small 2024, 20, e2303506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Z.; Gong, G.; Liu, X.; Yin, J. Mechanism of regulating macrophages/osteoclasts in attenuating wear particle-induced aseptic osteolysis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1274679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, N.A.; Sussman, E.M.; Stegemann, J.P. Aseptic and septic prosthetic joint loosening: Impact of biomaterial wear on immune cell function, inflammation, and infection. Biomaterials 2021, 278, 121127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, G.; Ha, D.P.; Wang, J.; Xiong, M.; Lee, A.S. ER chaperone GRP78/BiP translocates to the nucleus under stress and acts as a transcriptional regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2023, 120, e2303448120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xu, C.; Fang, G.; Li, X.; Chen, J. The Differential Expressions and Associations of Intracellular and Extracellular GRP78/Bip with Disease Activity and Progression in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Bioengineering-Basel 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.H.; Im, S.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, D.; Jeong, K.; Ku, J.M.; Nam, T.G. Chemical Chaperones to Inhibit Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress: Implications in Diseases. Drug Des Devel Ther 2022, 16, 4385–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Gong, H.; Bai, T.; Fu, Y.; Li, X.; Lu, J.; Zhao, J.; Chen, J. Pharmacological Intervention with 4-Phenylbutyrate Ameliorates TiAl6V4 Nanoparticles-Induced Inflammatory Osteolysis by Promoting Macrophage Apoptosis. Bioengineering-Basel 2025, 12, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zheng, S.; Chen, B.; Wen, Y.; Zhu, S. Sodium phenylbutyrate antagonizes prostate cancer through the induction of apoptosis and attenuation of cell viability and migration. OncoTargets Ther. 2016, 9, 2825–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.H.; Yue, Z.S.; Zheng, W.J.; Shen, H.F.; Zeng, L.R.; Hu, Z.Q.; Xiong, Z.F. 4-Phenylbutyric acid presents therapeutic effect on osteoarthritis via inhibiting cell apoptosis and inflammatory response induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2018, 65, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Pablo, S.; Rodriguez-Comas, J.; Diaz-Catalan, D.; Alcarraz-Vizan, G.; Castano, C.; Moreno-Vedia, J.; Montane, J.; Parrizas, M.; Servitja, J.M.; Novials, A. 4-Phenylbutyrate (PBA) treatment reduces hyperglycemia and islet amyloid in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes and obesity. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, E.G.; Lhotak, S.; Lebeau, P.; Byun, J.H.; Chen, J.; Platko, K.; Shi, C.; O’Brien, E.R.; Austin, R.C. 4-Phenylbutyrate protects against atherosclerotic lesion growth by increasing the expression of HSP25 in macrophages and in the circulation of Apoe(-/-) mice. Faseb. J. 2019, 33, 8406–8422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Cuesta, M.; Herrera-Gonzalez, I.; Garcia-Moreno, M.I.; Ashmus, R.A.; Vocadlo, D.J.; Garcia Fernandez, J.M.; Nanba, E.; Higaki, K.; Ortiz Mellet, C. sp(2)-Iminosugars targeting human lysosomal beta-hexosaminidase as pharmacological chaperone candidates for late-onset Tay-Sachs disease. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2022, 37, 1364–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, S.E.; Hendrix, S.; Nicodemus-Johnson, J.; Knowlton, N.; Williams, V.J.; Burns, J.M.; Crane, M.; Mcmanus, A.J.; Vaishnavi, S.N.; Arvanitakis, Z.; et al. Biological effects of sodium phenylbutyrate and taurursodiol in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement.-Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2024, 10, e12487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowser, R.; An, J.; Mehta, L.; Chen, J.; Timmons, J.; Cudkowicz, M.; Paganoni, S. Effect of sodium phenylbutyrate and taurursodiol on plasma concentrations of neuroinflammatory biomarkers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: results from the CENTAUR trial. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2024, 95, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, E.G.; Jeong, J.H.; Yoo, W.H. 4-Phenylbutyric acid, a potent endoplasmic reticulum stress inhibitor, attenuates the severity of collagen-induced arthritis in mice via inhibition of proliferation and inflammatory responses of synovial fibroblasts. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2021, 37, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liu, N.; Xu, Y.; Ti, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated inflammatory signaling pathways within the osteolytic periosteum and interface membrane in particle-induced osteolysis. Cell. Tissue. Res. 2016, 363, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Guo, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, N.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, J. Apoptotic pathways of macrophages within osteolytic interface membrane in periprosthestic osteolysis after total hip replacement. Apmis. 2017, 125, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Liu, G.; Shi, H.; Chen, J.; Dong, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J. Particle-induced osteolysis mediated by endoplasmic reticulum stress in prosthesis loosening. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 2611–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, N.; Shi, T.; Zhou, G.; Wang, Z.; Gan, J.; Guo, T.; Qian, H.; Bao, N.; Zhao, J. ER Stress Mediates TiAl6V4 Particle-Induced Peri-Implant Osteolysis by Promoting RANKL Expression in Fibroblasts. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0137774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemietz, I.; Brown, K.L. Hyaluronan promotes intracellular ROS production and apoptosis in TNFalpha-stimulated neutrophils. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1032469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijukumar, D.R.; Salunkhe, S.; Zheng, G.; Barba, M.; Hall, D.J.; Pourzal, R.; Mathew, M.T. Wear particles induce a new macrophage phenotype with the potential to accelerate material corrosion within total hip replacement interfaces. Acta Biomater. 2020, 101, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, W.; Lyu, Z.; Long, T.; Wang, Y. ZnO nanoparticles attenuate polymer-wear-particle induced inflammatory osteolysis by regulating the MEK-ERK-COX-2 axis. J. Orthop. Transl. 2022, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibon, E.; Cordova, L.A.; Lu, L.; Lin, T.H.; Yao, Z.; Hamadouche, M.; Goodman, S.B. The biological response to orthopedic implants for joint replacement. II: Polyethylene, ceramics, PMMA, and the foreign body reaction. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B 2017, 105, 1685–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.B.; Gallo, J.; Gibon, E.; Takagi, M. Diagnosis and management of implant debris-associated inflammation. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2020, 17, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billi, F.; Campbell, P. Nanotoxicology of metal wear particles in total joint arthroplasty: a review of current concepts. J Appl Biomater Biomech 2010, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, A.; Pawar, V.; Mcallister, K.; Weaver, C.; Hallab, N.J. Orthopedic implant cobalt-alloy particles produce greater toxicity and inflammatory cytokines than titanium alloy and zirconium alloy-based particles in vitro, in human osteoblasts, fibroblasts, and macrophages. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2012, 100, 2147–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovski, S.; Bartold, P.M.; Huang, Y.S. The role of foreign body response in peri-implantitis: What is the evidence? Periodontol. 2000 2022, 90, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wu, W.; Cao, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Tang, T.; Dai, K. Pathways of macrophage apoptosis within the interface membrane in aseptic loosening of prostheses. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 9159–9167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catelas, I.; Petit, A.; Zukor, D.J.; Marchand, R.; Yahia, L.; Huk, O.L. Induction of macrophage apoptosis by ceramic and polyethylene particles in vitro. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Peng, X.; Li, C.; Dang, Y.; Ma, R. Calycosin alleviates titanium particle-induced osteolysis by modulating macrophage polarization and subsequent osteogenic differentiation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wen, Z.; Li, S.; Chen, Z.; Li, C.; Ouyang, Z.; Lin, C.; Kuang, M.; Xue, C.; Ding, Y. LncRNA Neat1 promotes the macrophage inflammatory response and acts as a therapeutic target in titanium particle-induced osteolysis. Acta Biomater. 2022, 142, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaveri, T.D.; Dolgova, N.V.; Lewis, J.S.; Hamaker, K.; Clare-Salzler, M.J.; Keselowsky, B.G. Macrophage integrins modulate response to ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene particles and direct particle-induced osteolysis. Biomaterials 2017, 115, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, J.P.; Stelzer, J.W.; Garvin, P.M.; Wellington, I.J.; Solovyova, O. The Role of the Innate Immune System in Wear Debris-Induced Inflammatory Peri-Implant Osteolysis in Total Joint Arthroplasty. Bioengineering-Basel 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Peng, Y.; Fu, G.; Jin, J.; Wang, S.; Li, M.; Zheng, Q.; Lyu, F.J.; Deng, Z.; Ma, Y. Nano wear particles and the periprosthetic microenvironment in aseptic loosening induced osteolysis following joint arthroplasty. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1275086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deans, C.F.; Buckner, B.C.; Garvin, K.L. Wear, Osteolysis, and Aseptic Loosening Following Total Hip Arthroplasty in Young Patients with Highly Cross-Linked Polyethylene: A Review of Studies with a Follow-Up of over 15 Years. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmotti, A.; Messina, D.; Cykowska, A.; Beltramo, C.; Bellato, E.; Colombero, D.; Agati, G.; Mangiavini, L.; Bruzzone, M.; Dettoni, F.; et al. Periprosthetic osteolysis: a narrative review. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents. 2020, 34, 405–417. [Google Scholar]

- Eger, M.; Hiram-Bab, S.; Liron, T.; Sterer, N.; Carmi, Y.; Kohavi, D.; Gabet, Y. Mechanism and Prevention of Titanium Particle-Induced Inflammation and Osteolysis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgraeber, S.; von Knoch, M.; Loer, F.; Wegner, A.; Tsokos, M.; Hussmann, B.; Totsch, M. Extrinsic and intrinsic pathways of apoptosis in aseptic loosening after total hip replacement. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 3444–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, N.; Liu, K.; Zhou, G.; Gan, J.; Wang, Z.; Shi, T.; He, W.; Wang, L.; Guo, T.; et al. Autophagy mediated CoCrMo particle-induced peri-implant osteolysis by promoting osteoblast apoptosis. Autophagy 2015, 11, 2358–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Li, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Z.; Jin, Q. Suppression of titanium particle-induced TNF-alpha expression and apoptosis in human U937 macrophages by siRNA silencing. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 2013, 36, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Xiong, C.; Cao, L.; Wang, B.; Bao, N.; Zhao, J. Tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis regulates particle-induced inflammatory osteolysis via the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 1499–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Wu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Ge, Z.; Wang, D.; Zheng, C.; Zhao, R.; Lin, W.; Wang, G. Microenvironment-responsive smart hydrogels with antibacterial activity and immune regulation for accelerating chronic wound healing. J. Control. Release 2024, 368, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riwaldt, S.; Corydon, T.J.; Pantalone, D.; Sahana, J.; Wise, P.; Wehland, M.; Kruger, M.; Melnik, D.; Kopp, S.; Infanger, M.; et al. Role of Apoptosis in Wound Healing and Apoptosis Alterations in Microgravity. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 679650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Antonini, J.M.; Rojanasakul, Y.; Castranova, V.; Scabilloni, J.F.; Mercer, R.R. Potential role of apoptotic macrophages in pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2003, 194, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, V.; Brenner, D.A. Mechanisms of alcohol-induced hepatic fibrosis: a summary of the Ron Thurman Symposium. Hepatology. 2006, 43, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Ding, H.; Wang, D.; Ren, Z.; Chen, B.; Wu, Q.; Yuan, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.; et al. Particle-induced osteolysis is mediated by endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated osteoblast apoptosis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2023, 383, 110686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Hu, J.; Yang, X.; Xu, Q.; Chen, H.; Zhan, P.; Zhang, B. Sesamin inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis and attenuates LPS-induced osteolysis via suppression of ERK and NF-kappaB signalling pathways. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Bao, D.; Li, P.; Lu, Z.; Pang, L.; Chen, Z.; Guo, H.; Gao, Z.; Jin, Q. Particle-induced SIRT1 downregulation promotes osteoclastogenesis and osteolysis through ER stress regulation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 104, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Tian, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Man, Z.; Sun, S. Inhibitory effect of quercetin on titanium particle-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS)-related apoptosis and in vivoosteolysis. Biosci. Rep. 2017, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell 2010, 140, 900–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostoufi, A.; Baghgoli, R.; Fereidoonnezhad, M. Synthesis, cytotoxicity, apoptosis and molecular docking studies of novel phenylbutyrate derivatives as potential anticancer agents. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2019, 80, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqallaf, A.; Cates, D.W.; Render, K.P.; Patel, K.A. Sodium Phenylbutyrate and Taurursodiol: A New Therapeutic Option for the Treatment of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Ann. Pharmacother. 2024, 58, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Gupta, P.; Singh, A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Wahajuddin, M.; Mishra, A.; Singh, S. 4-Phenylbutyrate Mitigates the Motor Impairment and Dopaminergic Neuronal Death During Parkinson’s Disease Pathology via Targeting VDAC1 Mediated Mitochondrial Function and Astrocytes Activation. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 3385–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannitti, T.; Palmieri, B. Clinical and experimental applications of sodium phenylbutyrate. Drugs R&D 2011, 11, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, D.; Slobodnik, Z.; Tam, B.; Einav, M.; Akabayov, B.; Berstein, S.; Toiber, D. 4-phenylbutyric acid-Identity crisis; can it act as a translation inhibitor? Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Liang, G.; Egger, G.; Friedman, J.M.; Chuang, J.C.; Coetzee, G.A.; Jones, P.A. Specific activation of microRNA-127 with downregulation of the proto-oncogene BCL6 by chromatin-modifying drugs in human cancer cells. Cancer Cell 2006, 9, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wei, L.; Yang, Y.; Yu, Q. Sodium 4-phenylbutyrate induces apoptosis of human lung carcinoma cells through activating JNK pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 93, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.; Xu, W.; Reed, J.C. Cell death and endoplasmic reticulum stress: disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 1013–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapuy, O.; Marton, M.; Banhegyi, G.; Vinod, P.K. Multiple system-level feedback loops control life-and-death decisions in endoplasmic reticulum stress. FEBS Lett. 2020, 594, 1112–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Bailly-Maitre, B.; Reed, J.C. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: cell life and death decisions. J. Clin. Invest. 2005, 115, 2656–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, W.; Gu, Z.; Xiao, G.; Yuan, F.; Chen, F.; Pei, Y.; Li, H.; Su, L. 4-Phenylbutyrate Prevents Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated Apoptosis Induced by Heatstroke in the Intestines of Mice. Shock 2020, 54, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.B.; Gibon, E.; Gallo, J.; Takagi, M. Macrophage Polarization and the Osteoimmunology of Periprosthetic Osteolysis. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2022, 20, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; He, Q.; Wezeman, J.; Darvas, M.; Ladiges, W. A cocktail of rapamycin, acarbose, and phenylbutyrate prevents age-related cognitive decline in mice by targeting multiple aging pathways. GeroScience 2024, 46, 4855–4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paganoni, S.; Macklin, E.A.; Hendrix, S.; Berry, J.D.; Elliott, M.A.; Maiser, S.; Karam, C.; Caress, J.B.; Owegi, M.A.; Quick, A.; et al. Trial of Sodium Phenylbutyrate-Taurursodiol for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).