1. Introduction

The rise of the People's Republic of China as a primary architect of a new multi polar world order. Central to this ascent is a foreign policy doctrine that increasingly leverages economic strength and cultural outreach to build strategic partnerships, particularly in the Global South [

1]. While Uruguay, a small and stable country that has a strategical location in South America towards the Southern Cone, has emerged as an important partner for China within Mercosur. It can be said, that they have a strong trade relationship, which is focused on the Uruguayan agricultural exports and Chinese manufactured articles, which finally shapes the bases of the bilateral relationship between the two countries that has matured into a comprehensive strategic partnership that encloses politics, culture, and no less important, education.

It is also important to clarify that the China-Uruguay dynamic does not occur as an isolated but as a global strategy in which Uruguay aligns to global features regarding stability that minimize conflict with other powers, making of this country a safe partner. “Geopolitical competition between the United States and China has led to an increased reliance on economic statecraft. In this context, understanding the conditions that trigger trade, aid, or investment weaponization becomes crucial” [

2]. United with the Chinese, the soft power strategy and people-to-people, the cooperation in education operated in a wider geostrategic dynamic.

What is more, in the words of the existence of a South-South partnership does not just respond to an altruistic action but a combination of such motivation together with domestic, political, and self-interests goals, in which the domestic and political priorities are attended to while playing a core role in the new strategies for development [

3]. In this sense, the cooperative relationship between China and Uruguay depicts a mutual gain dynamic instead of a hierarchical donation on behalf of China. What is more, it highlights the lead cooperation driven by mutual developmental objectives.

The present article explores the educational dimension. It depicts that it constitutes a foundation of the bilateral connection that summits valuable and tangible benefits that involve both countries. Moving beyond the often-disbelieving discourse that surrounds the Chinese soft power [

4,

5], this study is centered on the practical advantages and synergistic results of this cooperation and connection between the two nations. What is more, the placement of the Confucius Institute at the Universidad de la República (UdelaR) in the year 2017 marked a significant pillar in the formalization of the cultural and linguistic exchange between China and Uruguay. Nevertheless, another important event, the announcement in 2022 of China's full funding and construction of a public, full-time school in Montevideo, which placed a starting point in the cultural and educational sphere, marking the beginning of a socioeconomically challenge, which was centered in Casavalle. This event represents an unprecedented evolution of this partnership, going from a university-level exchange to a direct community-level investment in fundamental education.

Together with this, it must be said that this study will analyze the Casavalle project, not as a mere and isolated act of aid, but as the result of a conscious and reciprocal agreed strategy. In the case of Uruguay, it represents a direct welcoming of resources into the country’s public education system, mitigating economic pressure while also supporting its developmental objectives. Whereas for China, it is an action that empowers its public diplomacy and a build bonds with a stable country as Uruguay, it is said to be, cultivating a strong country to country relationship, demonstrating its commitment to the Belt and Road Initiative’s (BRI's) stated principles of shared development and "a community with a shared future for humankind as can be read in Khan, [

6,

7]. In this way, this study will examine this synergy through the following structure: Firstly, the theoretical framework of soft power and South-South cooperation will be developed. Secondly, the historical context and deepening of Sino-Uruguayan relations will be detailed. Thirdly, the socioeconomic overview of Casavalle to contextualize the project's impact and nature will be provided. Fourthly, a thorough analysis of the Casavalle school project's parameters and benefits will be offered. Fifthly, the Chinese broader educational strategy in Uruguay will be situated. And finally, a synthesis on the mutual benefits and the project's significance as a model for international cooperation will be developed.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employs a qualitative, interpretive approach, which combines documentary and content analysis together with a case study methodology. Official documents, government communications, and academic literature were examined to study the design, motives, and implementation of China-Uruguay educational cooperation, with a focus on the Casavalle School Project (Escuela N. º 319 “República Popular China”).

Furthermore, documentary material was analyzed using thematic coding in order to identify recurring patterns and key themes. The process involved multiple readings, highlighting significant ideas, assigning and grouping initial and similar codes, into broader thematic categories. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion between to two authors to ensure consistency and reliability.

The main themes identified (

Table 1) include: educational diplomacy, encompassing initiatives such as the Confucius Institute, language instruction, cultural programs, scholarships, and pedagogy alignment; mutual benefits, reflecting tangible gains such as infrastructure investment, improved educational quality, social inclusion, human capital development, and cultural understanding; and cooperation strategies, covering bilateral agreements, strategic partnerships, co-funding, policy alignment, local engagement, and people-to-people programs. Additional themes related to monitoring and transparency capture project tracking, evaluation, and public accountability.

This thematic coding provides a structured framework for analyzing the practical and strategic dimensions of the China-Uruguay educational partnership, linking evidence from documents to the overarching themes presented in

Table 1.

3. Theoretical Framework: Soft Power, South-South Cooperation, and Mutually Beneficial Development

The cooperation between China and Uruguay could be best understood through the intersecting point of view of Joseph Nye through the concept of soft power and the practice of South-South collaboration.

3.1. Soft Power as a Positive Force

Joseph Nye et al. (2004) explain soft power as "the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion or payments [

8]." In other words, it means that power arises from the attractiveness of a country's culture, political ideals, and policies. While some scholars have a critical view of it, that implies that China's soft power strategy has been developed as a form of sharp power, which has the final goal of manipulation [

9], An alternative point of view comprehends its potential for building real and genuine positive results. What is more, in the words, the Chinese soft power tools, which include educational projects, could be "a resource for connectivity and development" [

8]that, in the end, will benefit both China and its partners [

10]. While respectful partnerships are developed, as is the case with the cooperation between China and Uruguay, these initiatives can build bonds of understanding and the facilitation of tangible development and resources, making soft power in which both countries can obtain benefits.

Besides, another important point to be explained is the concept of educational diplomacy. This term is usually defined as the strategic use of education as a tool of foreign policy, aiming to build long-term influence and trust between states [

11]. In the case of China, strategy involves important factors such as the Confucius Institutes, government scholarships, language programs, cultural exchanges, and targeted infrastructure investments. Scholars debate whether such initiatives are primarily altruistic, cooperative, or instrumental for soft-power projection [

12].

3.2. The Ethos of South-South Cooperation

South-South cooperation (SSC) pertains to the technical and economic cooperation among developing countries in the Global South, which is conventionally differentiated from North-South collaboration by its principles of mutual benefit, non-conditionality, lack of interference in domestic affairs, and equality [

13]. In this sense, China has positioned itself as the leader of SSC, while structuring its global engagements, which include the Belt and Road Initiative, within this global work prototype. This framing undertakes the Uruguayan dynamics. The relationship of cooperation is actually mutual, there is not a part that acts as the benefited and the other as the benefactor as it would be the case of a of a developed and powerful country which is in front of a developing recipient, but all the contrary, it is about two sovereign countries that are engaged in a partnership in which both of them negotiate terms and from where clear benefits are derived as it is reflected in the work of [

14]. In the words of Uruguay's former Foreign Minister, Rodolfo Nin Novoa, the relationship with China is one of "sovereign partners, based on mutual respect and shared interest" [

15]. This ethos declines the view that is often associated with Western aid and aligns with Uruguay's foreign policy principles of autonomy and solidarity.

In this sense, the Casavalle school project is a materialization of this bilateral framework, which in a word, would represent soft power in full action, while attracting Uruguay through the benefits that it would obtain, which in the end, would firmly operate within the SSC model. The result: a project agreed by two sovereign nations under the for veil of mutual development.

4. The Sino-Uruguayan Strategic Partnership: From Commerce to Comprehensive Cooperation

The educational cooperation between China and Uruguay did not arise in isolation. It is the result of a genuine, intentional, and accelerated strengthening of bilateral ties throughout the last twenty years, which transformed a straight commercial relationship into a multidimensional strategy between partners. What is more, a sustainable development is of great importance to maintain the development of a socioeconomic partnership environment [

16].

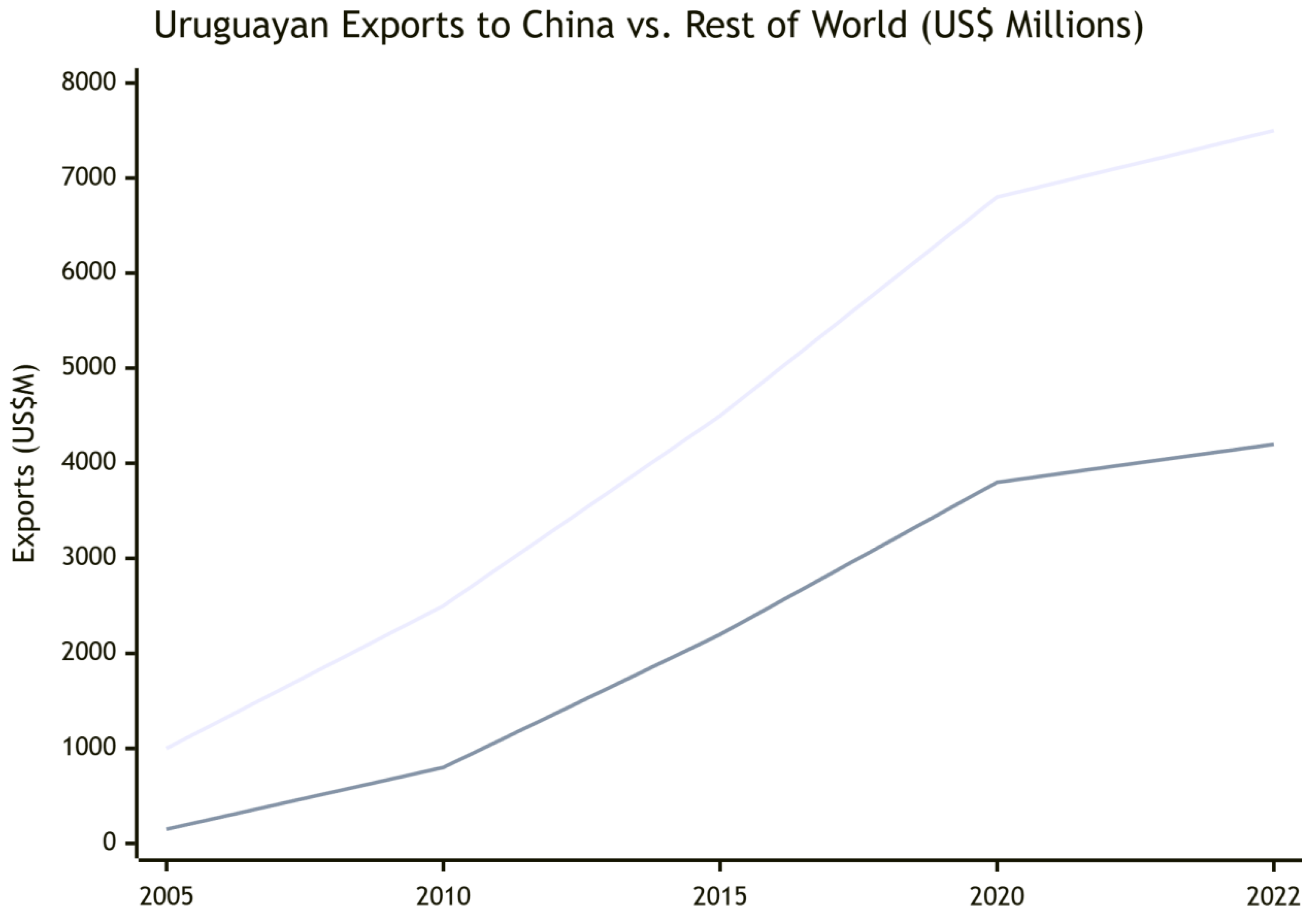

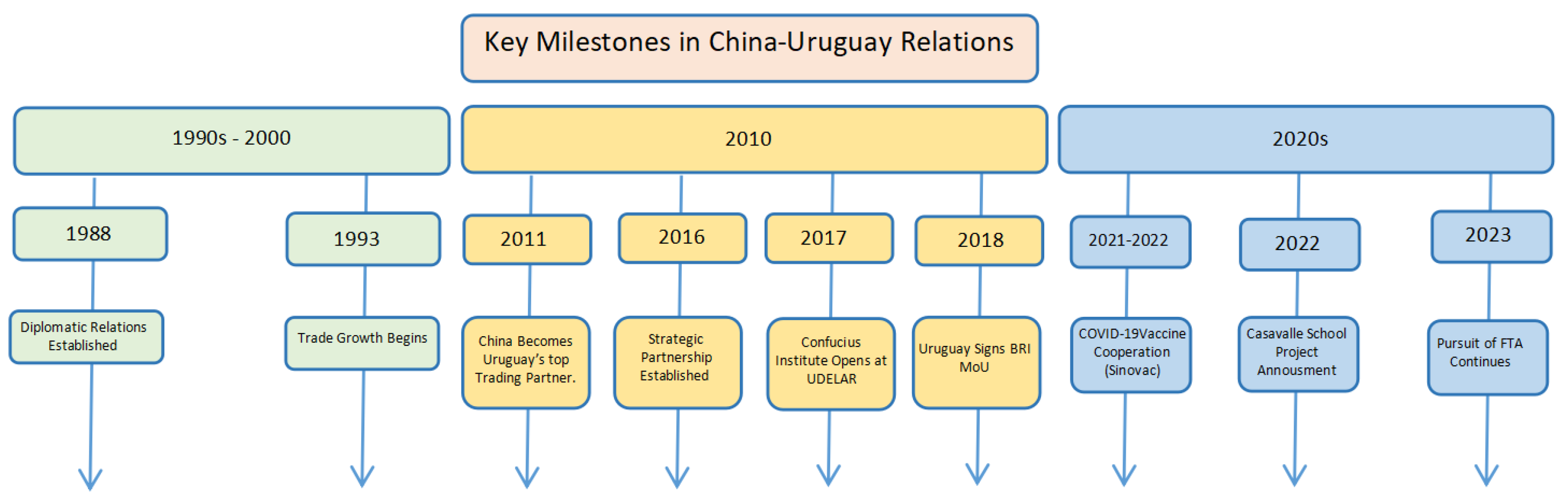

Back in 1988, diplomatic relations between Uruguay and China were established 1988, concerning the trading market as it can be seen in

Figure 1. While Uruguay found an expanding market for its products, such as soybeans, beef, pulp, wool, China accessed a reliable source of high-quality food and raw materials, such as the already mentioned products; nevertheless, according to [

17,

18,

19]. The qualitative shift in the Uruguay-China relationship took place during the presidency of José Mujica (2010-2015), who actively worked to diversify and expand Uruguay's international partnerships. This policy was continued and intensified by his successor, Tabaré Vázquez (2015-2020), Luis Lacalle Pou (2020-2025), while the current president, Yamandú Orsi, seems to align with this cooperation framework.

Banco Central del Uruguay,

Observatorio de Economía Internacional: Comercio Exterior Uruguayo [

20]. Major achievements highlighting this evolution include:

Strategic Partnership (2016): Under President Vázquez, bilateral relations were elevated to a "Strategic Partnership," the highest diplomatic designation in China's foreign policy lexicon, signaling a long-term commitment [

21,

22].

Belt and Road MoU (2018): Uruguay became the first Mercosur member to sign a Memorandum of Understanding to join the Belt and Road Initiative, a pivotal move that opened new avenues for cooperation in infrastructure, trade, and cultural exchange [

23].

COVID-19 Cooperation (2020-2021): China became a crucial partner during the pandemic, supplying Uruguay with vaccines, medical equipment, and expertise. As it was referred to by [

24]. This period demonstrated the reliability of the partnership in a crisis and built immense goodwill, further paving the way for collaborative projects like the Casavalle school.

Note. Trade data from

UN Comtrade Database and

World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) [

25,

26,

27,

28].

Diplomatic milestones based on official government press releases from Uruguay’s Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores (MRREE) and China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA).

“Uruguay has a long history of a commercial relationship with China. It has been one of the main destinations of Uruguayan wool export for several decades. Because of these economic ties, the Uruguayan government has recognized the People’s Republic of China since it returned to democracy in 1985” [

29]. These circumstances of clear trust and understating result on an escalating collaboration, as it can be depicted in

Figure 2 from the year 1990, which essential for present and future agreements. Besides, Uruguay was the first Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR) member to support the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2018 which, in this way, has deepen the relationship between these two countries[

14]. Furthermore, the educational initiatives do not only operate individually as cultural projects but are actually, integrated elements that work together with government-to-government strategic alignment. What is more, both nations, Uruguay and China have invested political capital in developing a relationship of cooperation that pragmatically introduce concrete results, showing education as key component where these results are visibly achieved.

5. The Casavalle School Project: A Case Study in Mutually Beneficial Cooperation

5.1. The Casavalle Community: A Focus for Transformative Investment

The location chosen for this educational project is not incidental but it clearly depicts a strategic and empathetic understanding of social priorities in Uruguay. Casavalle is one of the most historically disadvantaged neighborhoods in Montevideo but even though it is socioeconomically challenging i also has a strong sense of community and resilience.

According to data from Uruguay's National Institute of Statistics[

30], this neighborhood presents indicators that it is below national averages, which means:

Higher poverty and indigence rates.

Lower median income and higher unemployment.

Educational deficits, showing elevated student attrition and lower secondary education completion rates.

While the Uruguayan government has consistently recognized that improving educational outcomes in vulnerable contexts is a national priority, the reality is that it is still very difficult to overcome the difficulties. Therefore, policies such as the "Áreas Pedagógicas" plan and the full-time school project have been especially designed to provide pragmatic support to give real opportunities to break cycles of poverty through education [

31].

The fact that the Chinese government chose to invest in Casavalle, directly aligns with Uruguay's own domestic development objective, demonstrating that China is not just imposing its national agenda in order to work on its already mention soft power but on the contrary, it is responsive to the identified needs of its partner, in this case, Uruguay. What is more, this alignment exemplifies a central and real commitment to the Uruguayan educational and cultural development highlighting real, effective, and empathetic South-South cooperation. In the words of former President, "The offer from China was precisely in line with our priorities. It wasn't them telling us what we needed; it was them asking how they could help us achieve our goals" [

32]. This approach ensures the project's sustainability and local ownership, as it is embraced rather than imposed.

5.2. Project Origins and Rationale

Casavalle project, Escuela N.º 319 (School N.º 319), is the school, generally called among the population, as Escuela "República Popular China" commonly referred to in the press by the same name. It has its origins in “Cuenca Casavalle” and the assignation to this place was due to the local educational needs. “Cuenca Casavalle” Casavalle is a socio-spatial construct representing the concentrated poverty and urban marginalization on the periphery of Montevideo [

33]. It involves three neighborhood, Borro, Marconi, and Villa García.

Besides, this region has been rapidly growing since the mid-20th century onwards by settling informal settlements known as “cantegriles” and social housing projects. What is more, this area has encounter significant challenges from the beginning, which includes improper infrastructure, lack of full access to quality public services such as education and health and problems related to public safety and drug traffic and addiction among its population. As a result, Cuenca Casavalle has often been stigmatized in by the Uruguayan society and media being a symbol of urban exclusion and poverty.

In addition to this, in the academic and social field, "Cuenca Casavalle" has served as an object of study regarding urban inequality, the inefficiencies of non-participatory housing programs, and the resilience of communities in environments of deep social exclusion. In this way, the Plan Cuenca Casavalle, began in 2013, representing a paradigmatic change in in the Uruguayan social policies giving an integrated and territorial approach to tackling urban poverty [

34]. This inter-institutional action pursued coordinated actions taking into account not only education but also housing, and social development in a historically disadvantaged area of the Uruguayan capital city. As a result, the Casavalle project was accomplished in cooperation with the Government of the People's Republic of China under Uruguay's broader Plan Cuenca Casavalle and municipal initiatives to promote and encourage the already descripted area giving it a new positive perspective.

In this way, Escuela República Popular China, the core element in Casavalle project, underscores the severity of the local deficit and functions as a key asset within these broader policy frameworks represents this community, endorsed for increased school capacity and future collaboration agreements while meetings with Chinese authorities enabled the donation and financing that made the new school possible. This project was formally closed through a presidential resolution in 2020 [

31]. Official municipal and national communications document the project's conception, construction phases, and community engagement [

35,

36].

5.3. The Casavalle School Project: A Paradigm of Mutually Beneficial Cooperation

In July 2022, former President Luis Lacalle Pou and Chinese Ambassador Wang Gang, announced in official sources, the Casavalle school project. They manifested that this initiative a concrete proof of the strategic and collaboration. What is more, they mentioned that it illustrates a carefully designed initiative with clear benefits for both parties. This event was reported by the National Administration of Public Education [

37].

5.4. Project Specifications and Uruguayan Benefits

The Casavalle project comprehends the integrated design and construction of a full-time public school for 250 children, from initial education, meaning 3-5 years old children, through primary school. The Chinese government, through its embassy in Uruguay, financed the entire project, estimated at $5-6 million USD. The Chinese state-owned enterprise Shandong Hi-Speed Group, which already had experience in Uruguayan infrastructure projects, was awarded the contract. On its behalf, the Uruguayan state, through the National Public Education Administration (ANEP), facilitated the land where the school was built and was responsible for the school's staffing, maintenance, and operation upon completion.

The benefits for Uruguay are direct and substantial:

1. Infrastructure Investment Without public expenditure responsibility. This means that this project represented a multi-million-dollar investment in public educational infrastructure at no upfront capital investment to the Uruguayan state. This released national resources for other critical areas, like teacher salaries or educational content.

2. Addressing a Key Social Priority: One of the main goals of the project is to promote equity, since the school is located in a community with high social vulnerability, the project can support social inclusion and equality through education.

3. Quality and Modern Facilities: The school was designed according to modern standards, involving "architectural elements of both countries" [

37], providing children in Casavalle with a high-quality learning environment, support that they deserve.

4. Cultural Enrichment: Plans to incorporate elements of Chinese language and culture into the curriculum offer Uruguayan students a meaningful opportunity to have access to a major world culture, supporting and encouraging intercultural competence from a young age.

5.5. Chinese Benefits and Diplomatic Objectives

While for China, the Casavalle project exemplifies a model of public diplomacy and serves several key strategic interests:

1. Strengthening community level trust and support: China has invested in pragmatical and social projects that have made a difference in normal people live. This builds a deep reservoir of positive sentiment towards China. This "gratitude factor" is a powerful component of soft power that can go beyond political periods.

2. Demonstrating the Belt and Road’s initiative (BRI) "People-to-People Bonds": The project is a quintessential example of the Chinese values, and the cultural and humanitarian nature of the Belt and Road Initiative. Besides, the Casavalle project has helped the BRI to be widely known in Uruguay, demonstrating that its initiative goes beyond ports and roads, showing a direct and positive impact on human and sociocultural development.

3. Strengthening the Bilateral Partnership: With such a demonstration of cooperative intent, the bonds between the two nations have strengthened, and the overall relationship, fostering an environment of trust that facilitates cooperation in other areas, has evolved from merely commercial collaboration to a more committed one.

4. Creating a Positive Model: This project serves as a positive example for other countries in South America and the region. Through the accomplishment of this project, China is perceived as a trustworthy, generous, and empathetic nation, a nation that is interested in the holistic development of its partners.

In conclusion, this collaboration generates a reciprocal advantage. This means that while Uruguay receives a fundamental societal asset, China empowers its international image and strengthens its strategic position as a receptive country. The Casavalle project is proof of the fact that national interest and altruistic collaboration are not mutually exclusive in international relations.

5.6. Construction, Financing and Inauguration

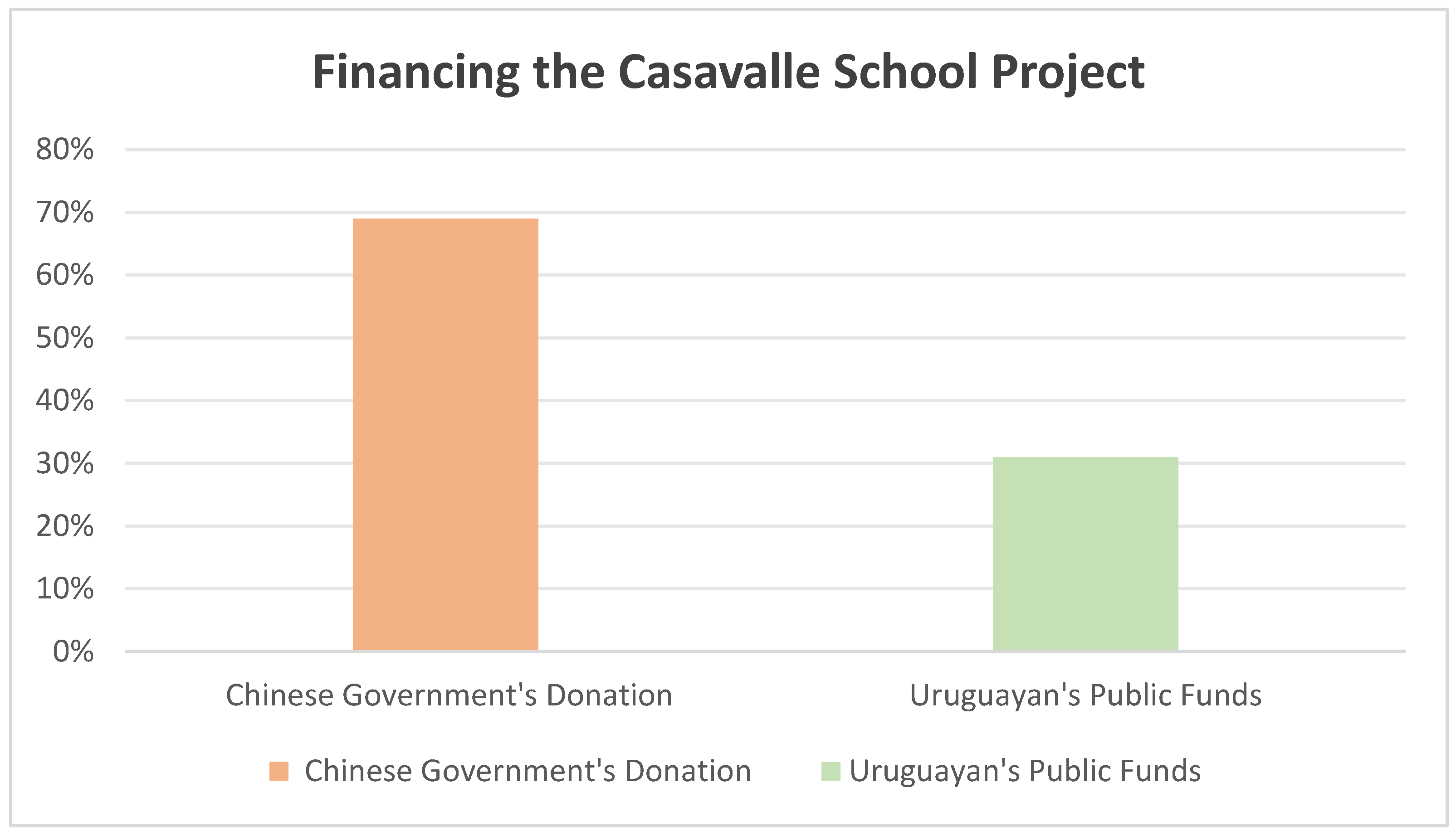

According to the Administración Nacional de Educación Pública (ANEP), the Casavalle project school, Escuela N.º 319 "República Popular China", construction formally began after the foundation stone placement in November 2018 and continued throughout 2019–2020. The completed campus consists of approximately 1,800 m² of built area and wide exterior spaces, which includes playgrounds and green surfaces. In addition, as it is depicted in

Figure 3, to this, the official announcement indicates that the total investment for the building reached approximately USD 2,954,606, of which the Government of China contributed USD 2,040,000, while the remainder was covered by Uruguayan public funds [

38,

39].

The school was completely finished and started being used in early 2020, being a full-time school that includes initial and primary levels and enrolls 300 to 360 students. The school inauguration was initially postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic situation, but was later held with national, departmental, and embassy representatives [

39,

40].

5.7. Programs, Enrollment and Activities

Publications and announcements by ANEP and DGEIP (Dirección General de Educación Inicial y Primaria) confirmed that Escuela N. º 319 operates as a full-time educational center that offers early childhood and primary education, taking into account the community's context and needs, as a full community-conscious project. What is more, the school has also hosted cultural events in which it received national leaders and diplomatic actors visits such as the Uruguayan Presidency’s actors and students, and delegations tied to China-related activities. There are repeated references to exchanges such as student visits and cultural activities that connect school life in Casavalle to broader bilateral programming [

37].

5.8. Transparency and Project Tracking

As a Chinese-funded school construction in Casavalle, the project database documents can be found in AidData, which leads to additional transparency through an independent project-tracking entry. The AidData record summarizes the project information including title and financing elements. What is more, it locates the school within China's project portfolio in Uruguay. In addition to this, public archives from the local government and national authorities which corroborate the financing breakdown and construction timeline, allowing a well-documented assessment of the investment's scope [

35,

38].

5.9. Community and Socioeconomic Impact

The community and social impact that the investment in Casavalle school infrastructure and the expanded educational facilities has indirect many community benefits, not just in the educational field but also in terms of employment during the school construction, local procurement, and the community parenting engagement resources, community events, and a sense of social community. What is more, the full-time school project may also provide nutritional and psychosocial support through different services which would even widen the impact of this project on the community. The Casavalle school's integration with municipal programs and Plan Cuenca initiatives manifests these potential impacts, providing a model of how external financing can align with local development strategies to produce broader social returns [

35].

5.10. Mechanisms of Mutual Benefit

The Casavalle project is an outstanding example that depicts how cooperation in the education field, between China and Uruguay is at ultimately bring benefits to both nations. Furthermore, these channels involve infrastructure investment, curricular and pedagogical exchange, language and cultural education, scholarship and mobility programs, and institutional partnerships.

In words of Pineau (2023), cooperation in the education area, is one of the main pillars of China-Uruguay relationship. This type of collaboration creates reciprocal gains through infrastructure, scholarships, and cultural exchange. A key example of this dynamic is the recent construction of a public school in Casavalle. This project, funded and built by China, exemplifies how this cooperation can be understood as tangible benefits, providing updated educational infrastructure for Uruguay while bolstering China's role as a development partner in the region[

41].

5.10.1. Infrastructure and Local Educational Capacity

As it was stated before, Uruguay has gained practical and tangible benefits concerning the Chinese cooperation in the Casavalle project, which mainly lies in the infrastructure enhancement. This can be appreciated in the financing of a modern, full-time primary school, which involves appropriate learning environments. As a result, it could be said that China's contribution to this project has directly expanded Uruguay's capacity to provide quality education facilities to vulnerable communities in Casavalle. These facilities include: new and updated classrooms, playgrounds, and community hubs, which would improve learning environments, a higher enrollment capacity, and the possibility of new educational actions that may be involved in full-time schooling, such as extended schooling time, integrated services, and extracurricular activities that probably would have taken more time to be implemented without the collaboration of China. The official accounting of the USD 2,040,000 Chinese contribution and the total project cost provides a transparent basis for assessing the scale of this contribution [

35,

40]. There is evidence of a close cooperation in education, both countries developed more than 40 events connected to this field during the period 2020 – 2022 in which the internation cooperation between China and Uruguay[

42].

6. The Broader Educational Ecosystem: Confucius Institutes and Scholarships

The Casavalle school project is the most visible China-Uruguay collaboration and it is identified as an innovative element of a broader and well-established educational approach but it is not the only one withing the two nations’ educational cooperation.

6.1. Language, Culture and Curricular Enrichment

The educational cooperation between China and Uruguay usually involves language teaching and cultural programs. It is the case of the presence of the Confucius Institute at Universidad de la República (Udelar) in Uruguay, which has been the main space for Mandarin instruction and Chinese cultural awareness at the tertiary level. In addition to this, these activities involve a complement for primary-level initiatives since they are creating pathways for students to pursue Chinese-language study and cultural interaction throughout the different educational stages. In this way, the Confucius Institute provides Mandarin teaching, teacher training opportunities as well as curricular materials, which may complement local curricula when it is performed in collaboration to the Uruguayan educators creating durable benefits for both sides: Uruguayans gain language and cross-cultural skills valuable in a globalized economy, while China increases familiarity with Mandarin and Chinese culture [

43].

The Confucius Institute was established in Uruguay in 2017 through a cooperation between the University of the Republic and China's Nankai University. In this way, the Confucius Institute (IC-UdelaR) has become the central path for Chinese language and culture in Uruguay, involving the following central contributions:

Language Access: The IC-UdelaR provides affordable, premium Mandarin courses to hundreds of Uruguayan which gathers, students, professionals in different areas, and general actors, providing them Chinese language skills which are highly valuable in the nowadays globalized economy.

Cultural Understanding: The IC-UdelaRIt organizes multiple events, such as cultural exchange, exhibitions, and academic seminars that gets China closer to Uruguayan people and encourage a better understanding of its history and traditions among Uruguayans.

Academic Exchange: It promotes the cultural exchange between Uruguayan and Chinese students and professionals while building valuable intellectual bridges. In the words of Rector of UdelaR, Rodrigo Arim, the institute represents "a door to the world, that strengthens the internationalization of the university" [

43].

In addition to this, even though the Confucius Institutes have faced global criticism involving academic freedom concerns [

44], the Uruguayan model, in has worked in partnership together with Universidad de la República, a strong and autonomous public university, as a result it has widely avoided such controversies. Contrary to those critics, the Confucius Institute in Uruguay has operated as a cultural and linguistic resource from the beginning, being consistent with Uruguay's interest in expanding its global connections[

45].

In addition to this, it could be said that the Confucius Institutes (CIs) are probably visible instruments of Chinese cultural diplomacy. Beginning in the mid-2000s, more than 40 Confuscious Institutes have been established in Latin America [

46]. Uruguay's CI is located at Universidad de la República and in collaboration with Qingdao University. It offers Mandarin courses, cultural workshops, and academic events. Literature suggests that while CIs are sometimes criticized for advancing Chinese state narratives, they are also valued by host universities for providing funding, materials, and new opportunities for students [

47].

6.2. Scholarship Programs

Inclusive and equitable quality education while promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all, was the core topic of the 4th goal of the United Nations Agenda 2030, aiming highlight education as a sustainable issue in terms of sustainable development goals (SDGs). In this way, providing more educational opportunities around the world, especially to developing country students, would lead to an inclusive and equitable education main for worldwide students[

48]. What is more, after international student graduate and go back to their countries, they may have access to more and better job opportunities while also promoting the development of their own home countries, not only at the ecological level but also in terms of human values, abilities and socioeconomical aspects. In this sense, China has grown an inner commitment, and even though the international students’ program is in the first stage, it is gaining a great importance in its agenda. As a result, China has launched three programs that Uruguayan students may have access to. These programs, such as the Chinese Government Scholarship through the Chinese Scholarship Council [

49] (CSC)(China Scholarship Council, n.d.), [

50] MOFCOM programs (Ministry of Commerce of the PRC, n.d.) and the [

51] (AUGM, n.d.) may provide full funding for Uruguayan undergraduates, postgraduates, and researchers to be able to study in China, covering a wide variety of fields which would directly be linked to the country's export economy (Wilson Center, 2021. These scholarships may result in significant benefits as follows:

Human Capital Development: Uruguay gains a cohort of highly trained professionals with firsthand experience in China, who return with valuable skills and insights applicable to the bilateral relationship and Uruguay's own development.

Deepening Bilateral Ties: Students would become cultural ambassadors, and they would foster long-term people-to-people connections, enabling a strong bilateral relationship.

It must be highlighted that the official embassy and scholarship portal provide information regarding the ongoing scholarship opportunities and the mechanisms to apply to each of them. Furthermore, it must be said that these mobility programs linked to the different scholarship opportunities are mutually beneficial: Uruguay would be able to gain trained professionals and researchers with unique competencies and viewpoints, while China would strengthen people-to-people ties and cultivate a cohort of professionals with firsthand experience of Chinese higher education (Wilson Center, 2021).

How does the Casavalle project fit in this context?

The Casavalle school project, as it was mentioned before, also fits in this frame. While the Confucius Institute and scholarships focus on university students and professionals, the school project extends this cultural and educational opportunity to the fundamental level and to a non-elite community which would enable a deep partnership while having a strong social impact.

6.3. Institutional Partnerships and Research Collaboration

In the case of institutional partnership and research collaboration regarding the university, the Sino-Uruguayan collaboration includes institutional agreements such as cooperation in research projects and exchange arrangements. In this sense, the Confucius Institute at Udelar, as it was mentioned before, was established in partnership with the Chinese university, Qingdao University, which provides a platform for intercultural programming and potential academic cooperation. These two universities have bilateral agreements supported by government dialogues that create a valuable environment and ground for sustained cooperation that goes from vocational training to research collaborations in a great variety of fields. What is more, they may be tailored to Uruguay's development needs. Policy-focused literature on China's educational outreach emphasizes the multiplicity of these mechanisms beyond language centers[

52].

7. Analysis and Discussion

7.1. Weighing Benefits Against Concerns: An Academically Balanced View

Academic and policy literature presents both supportive and critical perspectives on Chinese educational collaboration in Latin America [

53]. Critics argue that such initiatives, often framed as soft-power projects, may influence governance, transparency, and curricula [

54] Supporters, however, emphasize tangible benefits, institutional strengthening, and opportunities for diversifying international partnerships. As noted by Chinese authorities, “Lo que China busca en América Latina es cooperación internacional, respeto mutuo y desarrollo mutuo, China también mantiene una actitud política neutral en cuanto a los asuntos regionales en América Latina” (translated: China pursues international cooperation, mutual respect, and mutual development, while maintaining a neutral stance on regional affairs) [

55].

The Casavalle school project exemplifies the practical benefits of this collaboration. Records indicate improvements such as modern facilities, increased enrollment capacity, and active community engagement, including official inaugurations. Transparency is demonstrated through publicly available documents detailing financing and project timelines. Clear contractual terms safeguard educational autonomy and curricular sovereignty, while local actors participate in decision-making, ensuring the project aligns with Uruguay’s public education priorities.

Overall, the Casavalle school project represents a potentially positive model of bilateral cooperation, contingent on continued oversight, transparency, and alignment with national education policies [

56,

57].

7.2. Policy Implications and Recommendations

Based on the analysis of the Casavalle project and the broader China-Uruguay educational collaboration, several policy recommendations emerge to maximize mutual benefits and mitigate potential risks:

1. Continue to publish detailed records on project financing, procurement, and operational management. Publicly available information, as in the Casavalle project, helps preserve trust and accountability [

35,

40].

2. Teachers, families, and community organizations should actively participate in the design and implementation of projects. Local engagement ensures sustainability and aligns initiatives with community needs [

36].

3. Develop clear linkages between primary, secondary, and higher education programs. For example, primary-level Mandarin instruction can provide pathways to Confucius Institute programs and scholarship opportunities, fostering long-term human capital development [

52].

4. Emphasize teacher training, contextualized curriculum development, and professional exchange programs. Collaboration should focus on pedagogical quality in addition to cultural or language promotion [

43].

5. Establish longitudinal monitoring of student attendance, learning outcomes, and community indicators. Independent evaluation, complemented by project-tracking tools like AidData, can ensure accountability and inform future cooperative initiatives [

38].

7.3. Discussion: How does the Casavalle School Project accommodate in a larger strategy?

The Casavalle school project represents a strategic node within China’s broader educational outreach in Latin America. It combines tangible aid, including infrastructure financing, with institutional presence, exemplified by the Confucius Institutes, and people-to-people exchanges, such as scholarships and mobility programs.

For Uruguay, the project provides access to opportunities that would otherwise be difficult for a historically vulnerable community with limited resources. For China, it strengthens cultural familiarity and fosters valuable bilateral ties at the societal level.

The project also demonstrates that even small, well-documented, transparent, and community-integrated initiatives can generate durable goodwill and tangible benefits without displacing or overlapping local government responsibilities. The Casavalle example, alongside the Confucius Institute and other Chinese soft-power initiatives, highlights the heterogeneous nature of China’s educational engagement. These initiatives range from university-level language and scholarship programs to infrastructure projects like the Casavalle school, with outcomes that depend heavily on local governance, transparency, and the host institutions’ capacity to channel benefits effectively [

52,

58].

8. Conclusion

The relation between China and Uruguay regarding educational engagement, manifested in projects as the Escuela N. º 319 "República Popular China" in Casavalle, the Confucius Institute at Universidad de la República, and the scholarship hub, has demonstrated that bilateral educational collaboration is capable of producing mutually beneficial results when it is implemented transparently and clearly and is aligned with local priorities. In the case of Uruguay, Chinese financing and institutional connections have accelerated the needed infrastructure investment and expanded opportunities for language learning, research collaboration, and student mobility. While for China, this linkage fosters cultural exchange while setting the groundwork for long-term interpersonal and institutional ties.

Ultimately, the Casavalle school project therefore, it serves as a concrete, verifiable, and transparent example of positive bilateral educational collaboration, being a model that involves careful governance and constant evaluation. What is more, based on work, the Casavalle project is a cooperation initiative in which cooperation has been motivated by solidarity on the one hand and strategic cooperation on the other, resulting in equitable outcomes. As a result, this case can be instructive for other contexts that aim to utilize international collaborations for local educational development. What is more, the Casavalle school depicts how a small-scale project can be able to generate large returns in terms of domestic development, community trust, and bilateral goodwill. Conclusively, it provides a replicable model: transparent, co-financed, aligned with national education policy, and embedded in a vulnerable community where the impact is most visible.

8.1. Limitations and Areas for Further Research

The current study is based on publicly available documentation, which can be found in official Uruguayan government releases, project records, press coverage, and academic literature. What is more, it must also be highlighted that those documents provide a valuable foundation for assessing the school's financing, building and inauguration but further research could utilize primary fieldwork involving interviews with users and actors who directly implicated in schools matters such as local educators, students, parents, Casavalle community and officials in order to measure any pedagogical impacts and to capture community perceptions throughout the time. Longitudinal quantitative and qualitative data on learning results would also strengthen assertion about the educational effectiveness connected to the project. Finally, developing a comparative work across the regio as comparing Casavalle to other China-supported educational infrastructure project in Latin America would help situate Uruguay's experience within broader regional patterns.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, and data curation, Flavia Tarragona and Zhang Hongyan; Writing original draft, Flavia Tarragona; Writing review and editing, Zhang Hongyan; Supervision and funding acquisition, Zhang Hongyan.

Funding

This research was supported by the The New Think Tank Construction Project of Shihezi University (Optimization and Promotion Strategies for the Group based Education Model of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps) [ZKJS202404].

References

- Shambaugh, D.L. China goes global: The partial power; Oxford University Press Oxford: 2013; Volume 111.

- Zelicovich, J.; Yamin, P.J.L.A.P. Society. Carrots or sticks? Analyzing the application of US economic statecraft towards Latin American engagement with China. 2024, 66, 58–77. [Google Scholar]

- Pauselli, G.J.L.A.P. Society. New Donors, New Goals? Altruism, Self-Interest, and Domestic Political Support in Development Cooperation in Latin America. 2021, 63, 45–73. [Google Scholar]

- d'Hooghe, I. The rise of China's public diplomacy; Netherlands Institute of International Relations" Clingendael": 2007.

- d'Hooghe, I. China's public diplomacy; Martinus Nijhoff Publishers: 2015; Volume 10.

- Khan, M.K.; Sandano, I.A.; Pratt, C.B.; Farid, T.J.S. China’s Belt and Road Initiative: A global model for an evolving approach to sustainable regional development. 2018, 10, 4234.

- Xi, J. Work Together to Build a Community with a Shared Future for Mankind. Available online: (accessed on.

- Nye, J.; Power, S.J.N.Y.P.A. The means to success in world politics. 2004, 193.

- Walker, C.; Ludwig, J.J.S.p.R.a.i. From ‘soft power’to ‘sharp power’: Rising authoritarian influence in the democratic world. 2017, 8-25.

- King, K. China's aid and soft power in Africa: The case of education and training; Boydell and Brewer: 2013.

- Ratzlaff, A. The New Silk Road in Science: China's Science Diplomacy in the Americas. 2024.

- Brito Munita, J.I.; Tagle Montt, F.J.J.R.U. DESPLIEGUE DEL PODER BLANDO CHINO EN AMÉRICA LATINA Y RECEPCIÓN EN LOS PAÍSES DE LA REGIÓN. 2023.

- Cooperation, U.N.O.f.S.-S. About South-South Cooperation. Available online: www.unsouthsouth.

- Volosyuk, O.V.; Cremella, C.Q.J.V.R.I.R. China and the Countries of the Global South: Uruguay and China Economic Cooperation at the Beginning of the 21st Century. 2025, 25, 309-321.

- (MRREE), M.d.R.E.d.U. Declaración de los Ministros de Relaciones Exteriores de Uruguay y China. 2018.

- Li, Y.; Zhu, X.J.S. The 2030 agenda for sustainable development and China’s belt and road initiative in Latin America and the Caribbean. 2019, 11, 2297.

- Ellis, R.E. Uruguay's values-based foreign policy includes growing ties to China. World Politics Review (WPR) June 9 2022.

- Hogenboom, B.; Baud, M.; Vicente, R.G.; Steinhöfel, D. China’s economic and political role in Latin America. 2022.

- Research, H. Uruguay and Mainland China elevate relations to comprehensive strategic partnership. Hong Kong Trade Development Council 2024-01-08 2024.

- (BCU), B.C.d.U. Observatorio de Economía Internacional: Comercio Exterior Uruguayo. Available online: https://www.bcu.gub.uy/Estadisticas-e-Indicadores/Paginas/Default (accessed on.

- Agency, X.N. China, Uruguay agree to establish strategic partnership. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-10/18/c_135763848 (accessed on.

- Nolte, D. China and Mercosur: An ambivalent relationship. In Proceedings of the China’s Interactions with Latin America and the Caribbean; 2020; pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Portal, B.a.R. Uruguay signs MoU with China to jointly build Belt and Road. Available online: https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov (accessed on.

- Levaggi, A.G.; Barreiro, V.V.J.P. Eurasia Rising. 2021, 9, 170-185.

- (UN), U.N. Comtrade Database. Available online: https://comtradeplus.un.org/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Bank, W. World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS). Available online: https://wits.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- (MRREE, M.d.R.E. Comunicados de prensa oficiales. Available online: https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-relaciones-exteriores/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- (MFA), M.o.F.A.o.t.P.s.R.o.C. Press releases on China–Uruguay relations. (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Bittencourt, G.J.C.S.I.L.A.; CARIBBEAN, T. CHINESE FINANCING IN URUGUAY. 259.

- (INE), I.N.d.E. Encuesta Continua de Hogares (ECH). Available online: https://www.ine.gub.uy/encuesta-continua-de-hogares (accessed on.

- Uruguay, P.d.l.R.O.d. Resolución N.º 93/2020: Acta de entrega entre la República Popular China y la República Oriental del Uruguay relativa al Proyecto de construcción de una Escuela Primaria en el barrio Casavalle de Montevideo. 2020.

- Lacalle Pou, L. China’s Xi meets Uruguay president, upgrades ties. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-xi-meets-uruguay-president-upgrades-ties-2023-11-22/ (accessed on.

- Montevideo, I.d. Cuenca del Casavalle (documento técnico). Master’s thesis.

- (OPP), O.d.P.y.P. Plan Cuenca Casavalle: Memoria 2013-2014. 2014.

- Montevideo, I.d. De China a Casavalle. Available online: https://montevideo.gub.uy/noticias (accessed on.

- Montevideo, I.d. Escuela República Popular China se inaugurará en 2020. Available online: https://montevideo.gub.uy/noticias (accessed on.

- Uruguay, P.d.l.R.O.d. Gobierno y Embajada de China construirá escuela pública en Casavalle. Presidencia de la República Oriental del Uruguay 2022.

- AidData. Chinese official finance to Uruguay: School construction project in Casavalle (Project ID #54986). Available online: https://china.aiddata.org/projects/54986 (accessed on.

- D, M. Escuela República Popular China – Casavalle. Available online: https://municipiod.montevideo.gub.uy/noticias (accessed on.

- Pública, A.N.d.E. Casavalle disfrutó de inauguración de Escuela “República Popular China” aplazada por la pandemia. Available online: https://www.anep.edu.uy/casavalle-disfruto-de-inauguracion-de-escuela-republica-popular-china-aplazada-por-la-pandemia (accessed on.

- Pública, A.N.d.E. La escuela de tiempo completo N.º 319 “República Popular China” de Casavalle cerró el año con la presencia del embajador. Available online: https://www.dgeip.edu.uy/prensa/4439-la-escuela-de-tiempo-completo-n%C2%B0319-%E2%80%9Crep%C3%BAblica-popular-china%E2%80%9D-de-casavalle-cerr%C3%B3-el-a%C3%B1o-con-la-presencia-del-embajador/ (accessed on.

- Internacional, A.U.d.C. Cooperación China – Uruguay fortalece capacidades nacionales en educación. Available online: https://www.gub.uy/agencia-uruguaya-cooperacion-internacional/comunicacion/noticias/cooperacion-china-uruguay-fortalece-capacidades-nacionales-educacion (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- (UdelaR), U.d.l.R. Inauguraron Instituto Confucio de la Universidad de la República. Available online: https://www.universidad.edu.uy/prensa/renderItem/itemId/38438 (accessed on.

- Hubbert, J.J.A.-P.J. Globalizing China: Confucius Institutes and the Paradoxes of Authenticity and Modernity. 2019, 17, e2.

- (UdelaR), U.d.l.R. UdelaR y Hanban firmaron acuerdo para instalar Instituto Confucio [UdelaR and Hanban signed an agreement to install a Confucius Institute]. Available online: https://www.udelar.edu.uy/portal/2016/12/udelar-y-hanban-firmaron-acuerdo-para-instalar-instituto-confucio/ (accessed on.

- Lioy, A.; Kaplanová, A.J.T.H.J.o.D. And Then Came Soft Power: The Literature on Chinese Cultural Diplomacy in Latin America. 2025, 20, 353-367.

- Agency, X.N. Confucius Institute launched in Uruguay. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com (accessed on.

- Wang, Y.; Duan, X.; Chen, Z. Pathways to the Sustainable Development of Quality Education for International Students in China: An fsQCA Approach. 2022, 14, 15254.

- (CSC), C.S.C. Study in China: Chinese Government Scholarship. Available online: https://www.campuschina.org/ (accessed on.

- (MOFCOM), M.o.C.o.t.P.s.R.o.C. MOFCOM scholarship programs.Available online: https://www.china-aibo.cn/ (accessed on.

- AUGM. Beca AUGM–República Popular China. Available online: https://grupomontevideo.org/beca-augm-republica-popular-china/ (accessed on.

- China’s education diplomacy in Latin America. 2024.

- Peters, E.D.J.C.C. China’s recent engagement in Latin America and the Caribbean: Current conditions and challenges. 2019, 99.

- Gauttam, P.; Singh, B.; Singh, S.; Bika, S.L.; Tiwari, R.P.J.H. Education as a soft power resource: A systematic review. 2024, 10.

- Niu, H.J.L.p.d.C.e.A.L.y.e.C. Las políticas y estrategias de China hacia América Latina y el Caribe. 2017, 99-122.

- (AUCI), A.U.d.C.I. China y Uruguay avanzan en la construcción de escuela pública de tiempo completo. Available online: https://www.gub.uy/agencia-uruguaya-cooperacion-internacional/comunicacion/noticias/china-uruguay-avanzan-construccion-escuela-publica-tiempo-completo (accessed on.

- Santín, D.; Sicilia, G.J.L.A.E.R. Measuring the efficiency of public schools in Uruguay: main drivers and policy implications. 2015, 24, 5.

- Duarte, L.; Albro, R.; Hershberg, E. Communicating influence: China's messaging in Latin America and the Caribbean. 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).