1. Introduction

The construction industry is seeking innovative, sustainable solutions in response to rising activity and mounting pressure to manage waste efficiently [

1]. Construction and demolition waste (CDW) originates from debris and poor practices (deficient planning, inadequate handling) and, owing to its chemical nature, is not amenable to aerobic/anaerobic digestion, composting, or chemical degradation; it often ends up in informal dumps, creating environmental liabilities. In 2018 the global average was estimated at 604 kg·capita⁻¹·year⁻¹, with a projected +60% increase by 2050 [

2,

3,

4]. These volumes exacerbate soil and water pollution and contribute to climate change through GHG emissions [

2,

3].

In Peru, construction is a major waste source; Lima reported 3,881,000 t of municipal waste in 2020 (+7.4% vs. 2019), and in La Libertad building activity grew 3.8% per year (2013–2022), reflecting expansion driven by self-construction and housing/infrastructure demand [

5,

6]. This context increases CDW and strains management capacity; hence recycling and valorization strategies that integrate CDW into material value chains are required [

7]. The Peruvian legal framework (Law No. 1278 and its regulations; PLANRES; municipal ordinances) promotes minimization, segregation, material/energy recovery, traceability, and extended producer responsibility (EPR), establishing the basis for safely and standardly integrating CDW into construction materials [

8,

9,

10].

Leveraging CDW in materials reduces landfill demand and extraction of non-renewable resources (the sector consumes ≈ 3 billion tonnes of raw materials per year), enabling circular-economy pathways [

11,

12]. The literature proposes supplementary cementitious materials (silica fume, fly ash, quicklime, ceramic wastes, palm-oil by-products), with effects on strength, durability, and waste-management cost [

4]. In La Libertad (2017 census), 58.8% of dwellings use brick/concrete block, making PLR and PCR relevant fractions in the CDW stream [

13].

Within CDW, recycled brick powder (PLR)—rich in Si–Al—has been used as a cement replacement, with mechanical improvements around ≈15% substitution; some studies report no significant losses with 15% PLR and 30% recycled aggregates [

14,

15,

16]. Recycled concrete powder (PCR)—rich in Ca—is the most abundant residue globally, but its structural reuse is limited by abrasion, bulk density, and absorption, restricting it to non-structural applications [

17,

18].

Geopolymers emerge as a lower-carbon alternative to Portland cement: alkali activation of aluminosilicates forms N-A-S-H networks and, in the presence of Ca, C-A-S-H domains, achieving competitive mechanical and durability performance [

19,

20,

21]. Activation of Si–Al–Ca-rich materials (e.g., ceramic–cementitious CDW) shows favorable results at T ≥ 60 °C and low L/B ratios, consistent with dissolution → condensation → gelation/crystallization (Si–O–Al linkages) [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Activator chemistry is critical: Na₂SiO₃/NaOH (and solid variants Na₂CO₃, Na₂SiO₃·5H₂O) allows tuning workability, microstructure, and compressive strength (fc); the silicate modulus (SiO₂/Na₂O), NaOH molarity, and the use of KOH modulate strength and network densification [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

Evidence with PLR and ceramic tiles (BCR) shows that curing at 80–90 °C with 8–14 M NaOH yields 40–60 MPa, with clear influences of fineness and porosity of the precursor [

37,

38]. For PCR, single-precursor systems typically underperform (<10–27 MPa) unless co-activated with metakaolin or clinker and cured at 70 °C; typical limitations are a low SiO₂/(Al₂O₃+CaO) ratio and secondary carbonation [

38,

39]. Various binary PLR+PCR studies report synergies: 20–50% PCR densifies the matrix and improves fc, whereas excess PCR reduces reactive Si–Al species; optima around ≈10–20% PCR have been observed (lot/activator/curing dependent) [

40,

41,

42].

Despite advances, the literature shows two cross-cutting limitations: (i) inconsistent process variables (activator, L/S, curing) hinder inter-study comparisons and quantification of the pure effect of %PCR; (ii) scale decoupling: many mechanical results lack the multi-technique support (XRD/FTIR/SEM-EDS) needed to build convergent mechanistic arguments. Therefore, this article proposes to assess whether an optimal PCR fraction exists that maximizes compressive strength by enabling C-A-S-H/N-A-S-H synergy, and whether this can be demonstrated using independent tracers (FWHM in XRD, Δν in FTIR, and Ca (at.%) in SEM-EDS) under constant activator and curing conditions, thereby validating the role of Ca and gel coexistence reported for CDW systems [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

Accordingly, the general objective is to evaluate the effect of PCR/PLR proportion on the microstructure and compressive strength of geopolymer pastes, employing constant activator and curing, and triangulating XRD, FTIR, and SEM-EDS. We expect to demonstrate that an intermediate %PCR (with moderate Ca) maximizes network densification through C-A-S-H/N-A-S-H coexistence, translating into a peak compressive strength, as reported in [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44].

The contributions of this research are: isolation of the net effect of %PCR under constant activator and curing (uncommon in the CDW literature); multi-technique triangulation (fc–XRD–FTIR–SEM-EDS) to build a convergent argument on the Ca effect; a reproducible methodology (cylinder geometry, loading rates, normalized metrics) that facilitates transfer to other CDW families; and mapping of an optimal design window as a function of %PCR, supporting scale-up and quality-control roadmaps under feedstock variability [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

2. Materials and Methods

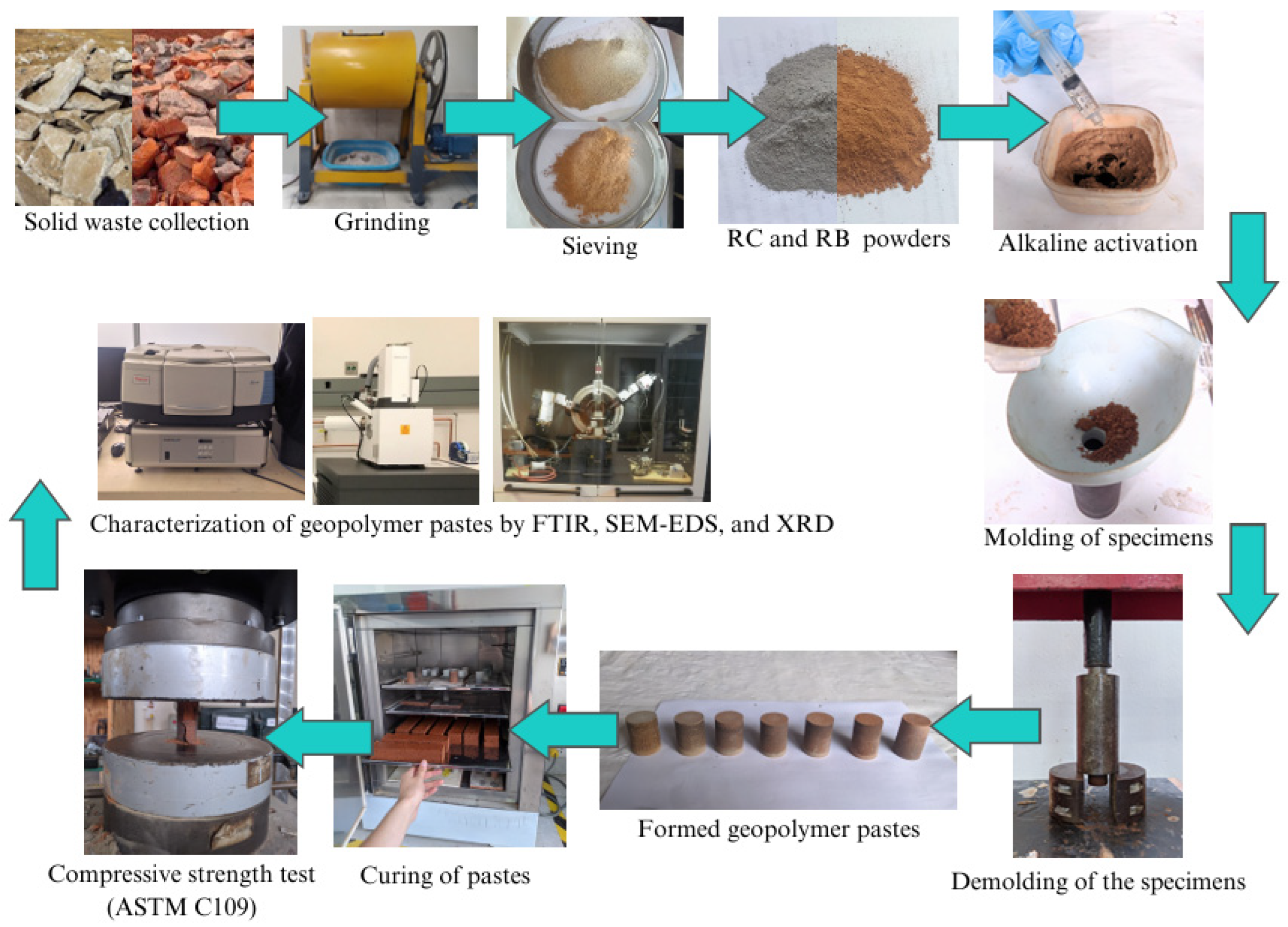

2.1. Materials

Recycled concrete powder (PCR/RCP) and recycled brick powder (PLR/RBP) were collected from construction and demolition waste (CDW) generated in Trujillo, Peru. Both were used as aluminosilicate precursors in alkali-activated geopolymer pastes.

Activator. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) flakes/pellets, ≥98 wt%, ACS (Macron), and potassium hydroxide (KOH) pellets, ≥90 wt%, ACS (Macron), were used. Sodium silicate (Na₂SiO₃) was a commercial solution with silica modulus (Mₛ = SiO₂/Na₂O) = 3.2, water as balance (reference density ~1.38 g mL⁻¹ at 20 °C). Deionized water was used to prepare the activator.

2.2. Activator Preparation

The ternary activator was formulated at a mass ratio of 0.10 NaOH : 0.60 Na₂SiO₃ : 0.30 KOH. For preparation, the hydroxides were dissolved separately in deionized water, allowed to cool to 23–25 °C, and then the Na₂SiO₃ solution was added under stirring to reach the target volume. Prior to mixing with the precursors, the activator was homogenized (5 min) and rested (≥15 min) to stabilize temperature and degassing. We report the formulation in mass fractions and the Na₂SiO₃ modulus (Mₛ = 3.2) as a sufficient chemical specification to reproduce the activator chemistry without resorting to molarities.

2.3. Mix Design and Paste Preparation

Seven formulations were produced by replacing PLR with PCR at 0, 10, 30, 50, 70, 90, and 100 wt% of the precursor (PLR provides the complementary fraction to 100% in each mix). The liquid-to-binder ratio (L/B) was fixed at 0.15 for all compositions; details are shown in

Table 2.

Powder conditioning. PCR and PLR were dried at 105 °C for 24 h, ground, and sieved to <37 μm (400 mesh) to minimize granulometry effects on early reactivity.

Table 1 reports the chemical composition of the raw materials.

2.4. Mixing Procedure

The dry powders (PCR, PLR) were pre-mixed for 2 min to homogenize. The activator was then added and mixed for 3 min at low speed in a Hobart paste mixer. Pastes were cast into metal cylinders, 25 mm diameter × 50 mm height, using compression molding (500 psi). Demolding was performed at 24 h. Curing was carried out in an oven at 40 °C for 72 h; specimens were then cooled and stored at room temperature until the testing ages (7, 14, and 28 days).

Table 2 lists the mixes produced.

2.5. Compressive Strength Test

Compressive strength was measured on a Tecnotest Modena universal testing machine (F060/EV) with parallel platens and verified alignment. Tests were run under displacement control at 1.0 mm·min⁻¹, with n = 5 specimens per age (7, 14, and 28 days). Strength is reported as mean ± SD.

2.6. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

Phase identification was performed on a Bruker D8 Advance powder diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å, 40 kV, 40 mA), θ–2θ mode. The scan covered 5–80° 2θ, step 0.020°, count time 1.0 s/step, with sample spinner enabled. Finely ground powders were mounted on low-background (Si-zero) holders. A Rietveld-type (semiquantitative) refinement was applied to estimate residual amorphous gels.

2.7. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

Spectra were acquired in ATR mode (Thermo Fisher Scientific iS50, diamond crystal) over 4000–400 cm⁻¹, 4 cm⁻¹ resolution, 32 scans per spectrum, with background correction prior to each measurement. Samples were dried at 60 °C for 24 h before analysis to limit physically adsorbed water.

2.8. Scanning Electron Microscopy and EDS (SEM-EDS)

Microstructure and local chemistry were examined on a Thermo Scientific Axia ChemiSEM (real-time EDS integration). Imaging was performed in high vacuum using SE (topography) and BSE (compositional contrast) detectors, with typical operating conditions of 5 kV (SE) and 15 kV (BSE), working distance 9–12 mm. At least five fields of view per sample (representative areas) were recorded, with magnification and scale reported on each micrograph.

2.9. Statistical Treatment and Quality Control

Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5 per age). Normality was checked with Shapiro–Wilk; when applicable, one-way ANOVA was used (α = 0.05). Instrument QA/QC: XRD was verified with Si standard (NIST SRM 640d); FTIR with a polystyrene film (reference bands check); SEM-EDS with internal/commercial standards (gain adjustment and drift correction).

Figure 1 shows the experimental workflow.

3. Results

3.1. Compression Resistance

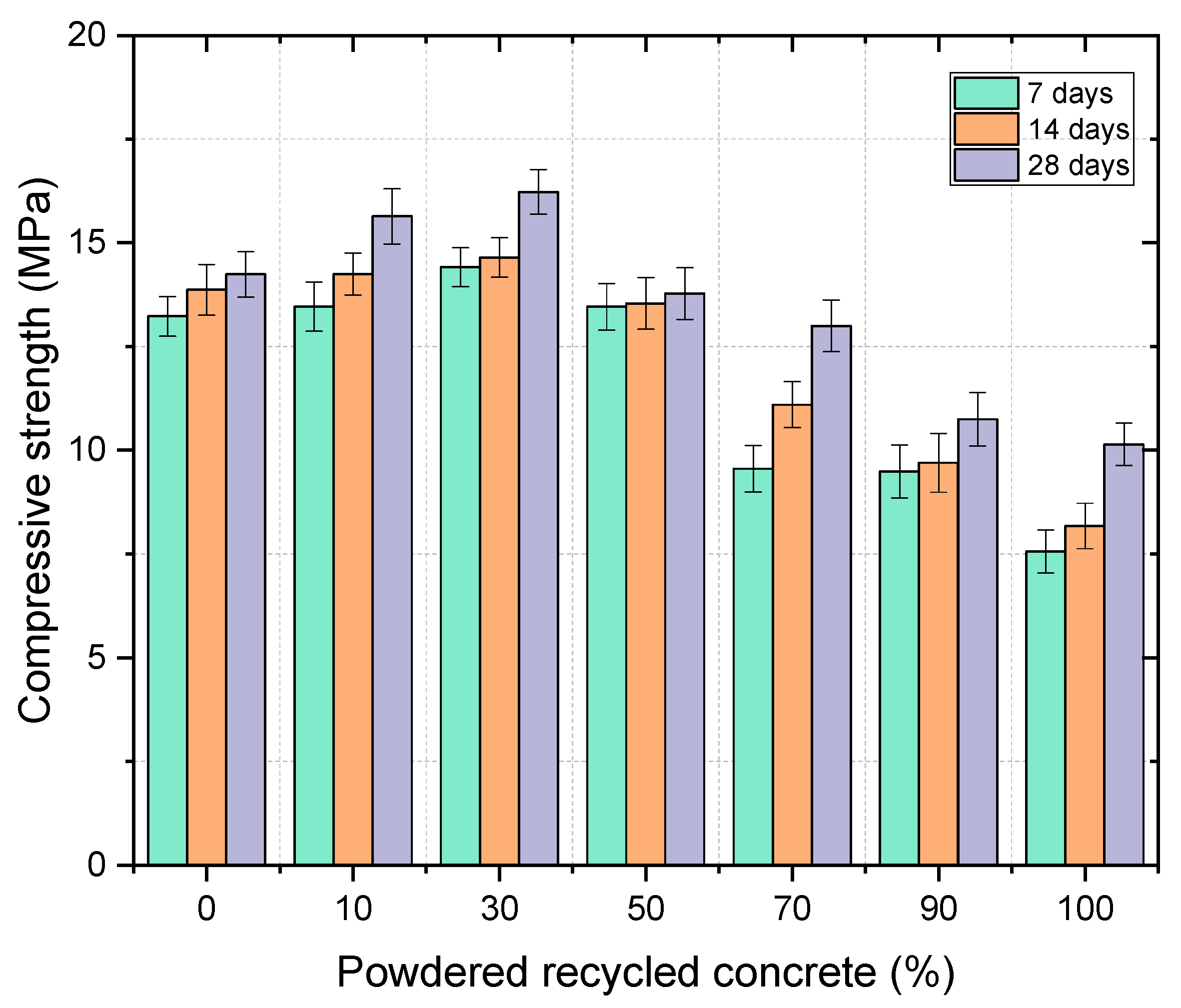

Figure 2 shows the fc of PLR–PCR pastes at 7, 14, and 28 days for PCR contents between 0–100%. A systematic increase in fc was observed between 0–30% PCR, followed by a loss for substitutions ≥50%. The 0% PCR (100% PLR) mix reached 13.2, 13.9, and 14.2 MPa (7, 14, and 28 d). With 10% PCR, values were 13.5, 14.3, and 15.6 MPa (+2.27%, +2.88%, and +9.86% vs. 0% PCR). The local maximum occurred at 30% PCR: 14.4, 14.7, and 16.2 MPa (+9.09%, +5.76%, and +14.08%). At 50% PCR, fc dropped to 13.5, 13.55, and 13.8 MPa (−2.27%, −2.52%, and −2.82%), with larger decreases at 70% PCR (9.5, 9.7, and 10.8 MPa; −28.03%, −30.21%, and −23.94%) and 100% PCR (7.6, 8.2, and 10.1 MPa; −42.00%, −41.01%, and −28.87%). Error bars (SD) reflect the dispersion typical of alkali-activated systems.

3.2. X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Compositional Effect

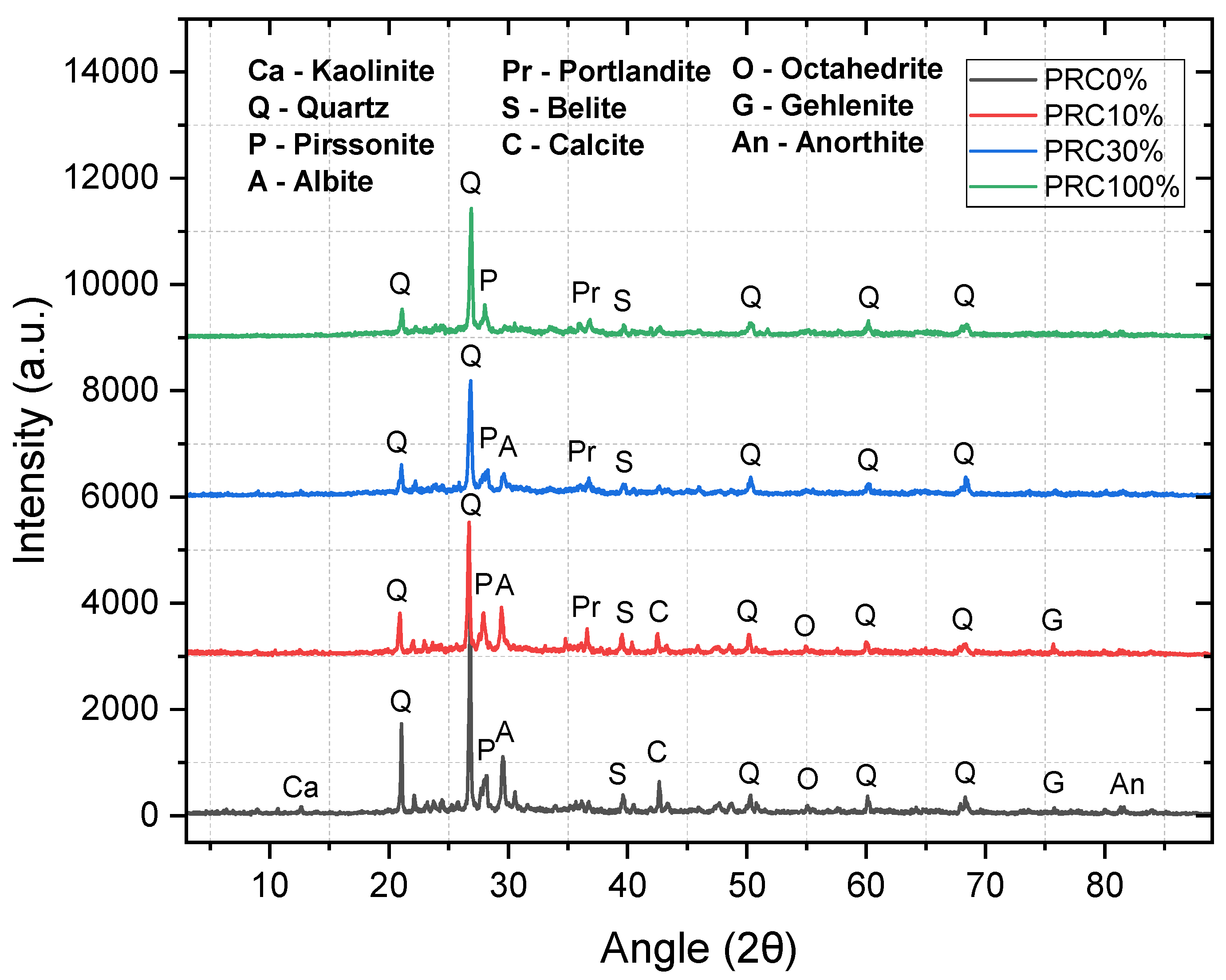

Figure 3 compares 28-day XRD patterns for 0, 10, 30, and 100% PCR. 0% PCR (pure PLR): broad set of crystalline phases (kaolinite, quartz, albite, belite, calcite, octahedrite, gehlenite, anorthite), with quartz dominant. 10–30% PCR: portlandite (~36.6° 2θ) appears (indicating hydration of residual clinker from PCR); the variety of PLR phases decreases while quartz (~26.7° 2θ) remains. At 30% PCR the relative intensity of albite decreases, consistent with aluminosilicate consumption and a larger amorphous fraction associated with reaction gels. 100% PCR: simplified pattern dominated by quartz and portlandite, with lower crystalline diversity, indicating the preeminence of Ca-rich products and reduced aluminosilicate contribution.

3.3. XRD at Curing Ages

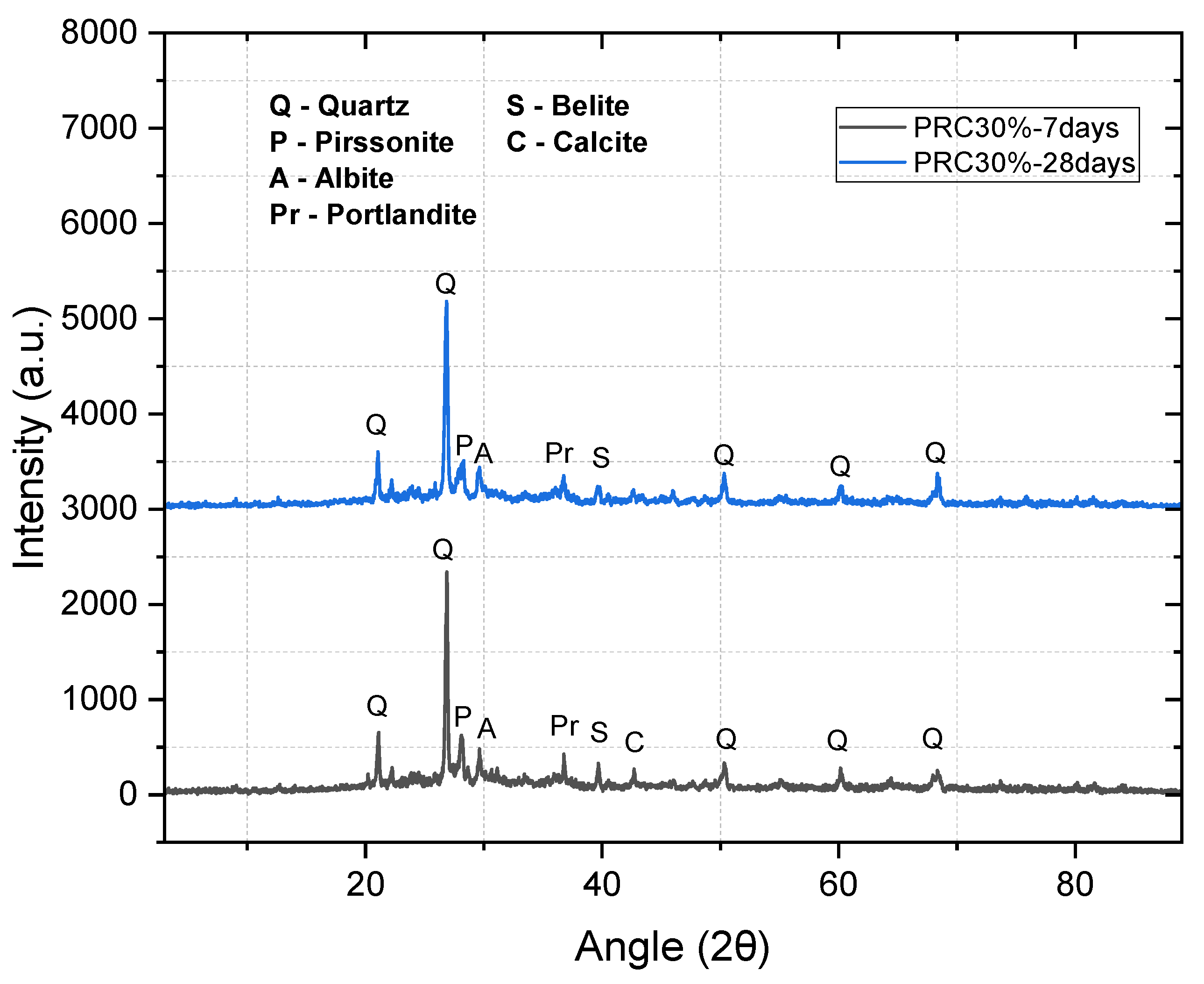

Figure 4 (30% PCR, 7 vs. 28 d) shows stable peak positions (quartz, albite, portlandite, belite, calcite) with a slight decrease in portlandite/belite intensities at 28 d, consistent with reaction progress and reorganization toward amorphous phases of the geopolymer network.

3.4. SEM-EDS: Microstructure and Local Chemistry

Figure 5 compares 28-day microstructures. 0% PCR: noticeable porosity and microcracks; unreacted particles present. EDS dominated by Si–Al (N-A-S-H matrix) with low Ca. 10% PCR: greater compaction with less perceptible microcracks; EDS shows higher Si and a slight rise in Ca, consistent with PCR addition. 30% PCR: denser matrix, no visible porosity/microcracks, and extensive amorphous regions; EDS evidences higher Ca (vs. 0–10%), indicative of C-A-S-H gels co-existing with N-A-S-H. 100% PCR: microdefects reappear (pores/microcracks) despite locally compact zones; EDS with higher Ca and lower relative Al–Si, suggesting heterogeneity and incomplete consolidation of a continuous aluminosilicate network.

3.5. FTIR: Network Signatures and Carbonates

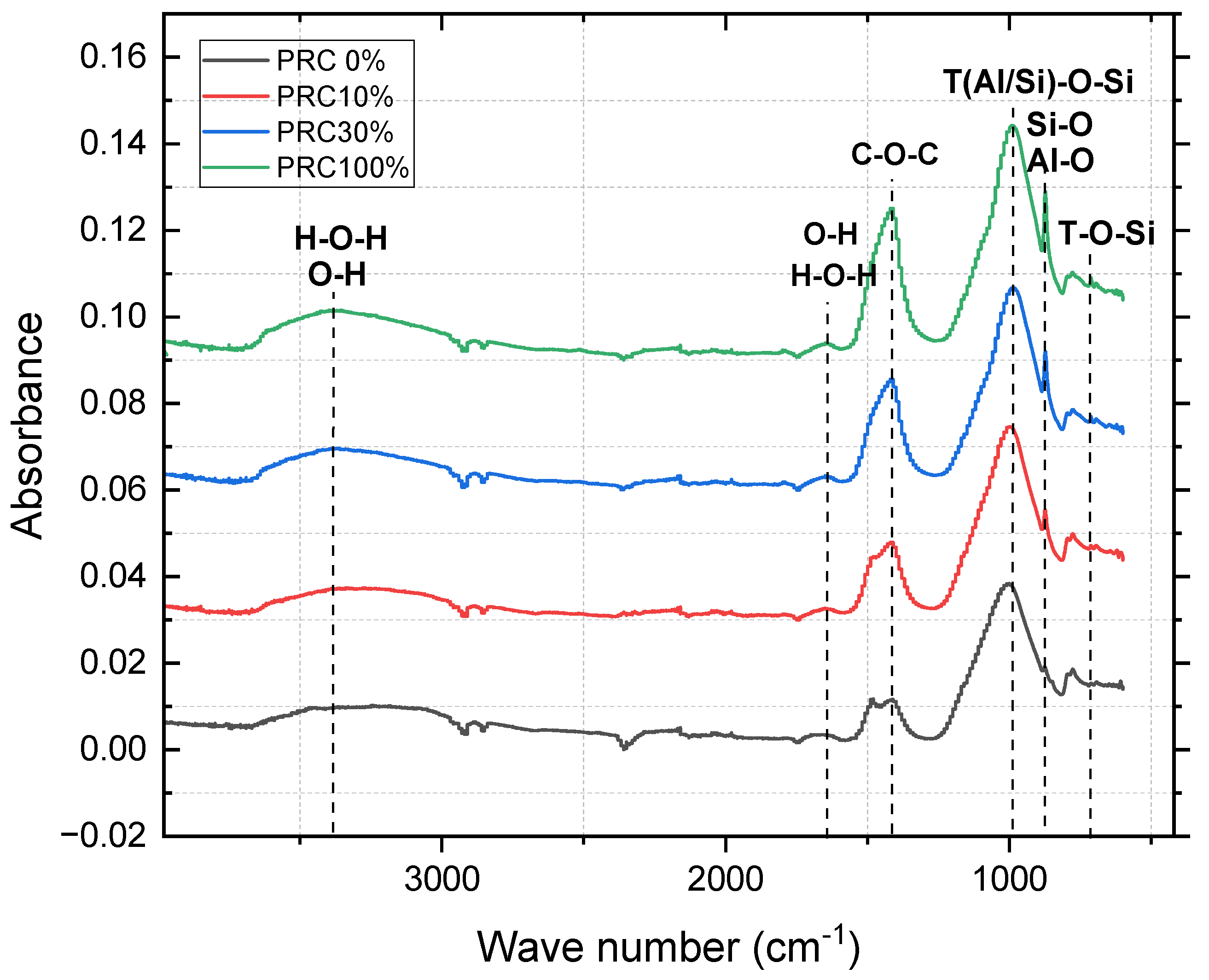

Figure 6 (0, 10, 30, and 100% PCR; 28 d) shows: (a) O–H/H–O–H (3440–3320 and 1690–1600 cm⁻¹): structural/interlayer water associated with gels. (b) Carbonates (C–O) (≈1460–1380 cm⁻¹): more pronounced with higher Ca (PCR), consistent with secondary carbonation. (c) T–O–Si (Si/Al) (≈1020–958 cm⁻¹) and Si–O–(Si/Al) (≈725–707 cm⁻¹): intensify at intermediate PCR, consistent with greater network polymerization.

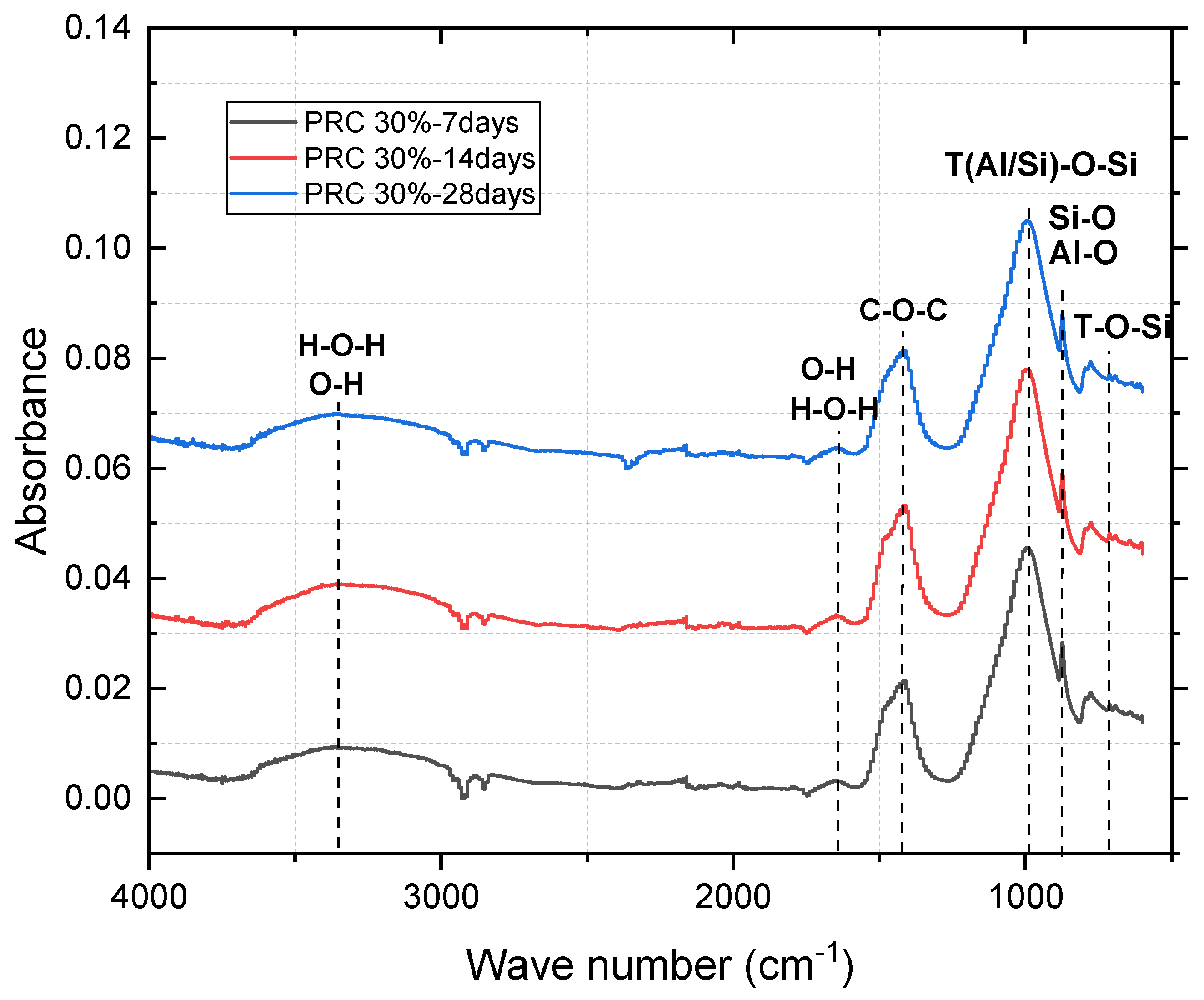

Figure 7 (30% PCR, 7–14–28 d) shows a sustained increase of the 1020–958 cm⁻¹ band, evidencing advancing condensation and time-dependent densification of the matrix.

4. Discussion

4.1. Reinforcement Mechanism: 30% PCR Mix

The mechanical data (

Figure 2) show a non-linear response with a peak fc at ≈30% PCR and progressive deterioration for substitutions ≥50%. This behavior is explained by a gel synergy whereby Ca provided by PCR nucleates C–A–S–H domains that bridge and densify the N–A–S–H network originating from the aluminosilicates in PLR [

43,

44,

45,

46]. While the Ca input remains moderate, the C–A–S–H/N–A–S–H co-existence increases connectivity, decreases effective porosity, and enhances load transfer; in contrast, once the PCR fraction exceeds that threshold, Ca²⁺ overloading together with dilution of reactive Si–Al species interrupts aluminosilicate crosslinking and activates competing routes (accelerated C–S–H formation and/or secondary carbonation), leading to a drop in fc [

42,

47,

48,

49]. This trend is consistent with systems where high PCR substitutions or Ca-rich fillers (calcite) dilute reactive aluminosilicates and penalize strength [

48,

49].

4.2. Diffractometric Evidence: Mineralogical Simplification and Growth of the Amorphous Fraction

The 28-day XRD patterns (

Figure 3) show that pure PLR (0% PCR) exhibits a broad crystalline palette (kaolinite, quartz, albite, belite, calcite, octahedrite, gehlenite, anorthite), in line with the ceramic nature of the precursor [

51,

52]. Upon introducing 10–30% PCR, portlandite (~36.6° 2θ) appears and the diversity of PLR phases decreases (e.g., albite), while quartz around 26.7° 2θ remains. This reduction of crystalline phases together with the emergence of Ca-rich phases indicates consumption/dilution of PLR crystalline aluminosilicates and growth of the amorphous fraction associated with N–A–S–H/C–A–S–H gels, in line with the fc increase at 30% PCR [

54,

55]. At 100% PCR, the pattern simplifies and is dominated by quartz/portlandite, evidencing Ca predominance and limitations of the aluminosilicate network, consistent with strength loss [

56,

57].

The correlation of FWHM and the amorphicity index over 18–38° 2θ maximizes at 30% PCR, whereas I_Q(26.7°) and I_Pr(36.6°) behave consistently with greater polymerization at intermediate Ca fractions and with crystalline simplification at 100% PCR (r(fc,FWHM) ≈ +0.86; r(fc,Amorphicity) ≈ +0.88) [

54,

55,

56,

57].

4.3. Spectroscopic Evidence (FTIR): Strengthening of T–O–Si Linkages and Secondary Processes

The 28-day FTIR spectra show reinforcement of the T–O–Si band (≈1020–958 cm⁻¹) in mixes with intermediate PCR, consistent with greater network extent and densification (in agreement with XRD and fc). The carbonate signal (≈1460–1380 cm⁻¹) becomes more pronounced in Ca-rich compositions, compatible with secondary carbonation that may locally stiffen but, at the network scale, interferes with aluminosilicate crosslinking when Ca is excessive [

42,

47,

48,

49,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72]. The time evolution (30% PCR, 7→28 d) with increasing T–O–Si confirms condensation progress under the applied curing protocol [

50].

4.4. Microstructure (SEM-EDS): Densification, Heterogeneity, and Chemical Balance

28-day SEM micrographs show a transition from a porous matrix with microcracks (0% PCR) to a compact microstructure with minimal defects (10–30% PCR), and then back to a heterogeneous state with reintroduced microdefects (100% PCR). EDS supports this narrative: the increase of Ca (at./wt.%) from 0→30% PCR underpins nucleation and bridging of C–A–S–H domains, whereas at 100% PCR high Ca with a lower relative Al–Si fraction is observed, consistent with less continuous networks and lower fc [

62,

63,

64,

65]. In sum, the triple triangulation (XRD–FTIR–SEM/EDS) supports the performance maximum around 30% PCR.

4.5. Kinetics and Curing: Initial Acceleration and Consolidation

Thermal pre-curing (40 °C, 72 h) accelerates dissolution–condensation of dissolved species and favours early gel formation; subsequently, room-temperature curing enables network reorganization and maturation, as reflected by the fc growth from 7→14→28 d and the intensification of structural FTIR bands [

37,

38,

50]. This sequence reproduces the directionality reported for ceramic–cement alkali-activated systems, provided the Ca/Si–Al balance remains moderate [

37,

38].

4.6. Role of Quartz and Albite: from Inherited Phase to Partial Reactive Precursor

Quartz (26.7° 2θ) behaves mainly as an inherited phase and a marker of residual crystallinity: higher intensities associate with lower amorphicity and lower fc (mild-to-moderate negative correlation in our metrics). Albite (29.54° 2θ), by contrast, acts as a source of Al/Si; its relative decrease at 30% PCR suggests consumption toward more extensive amorphous networks (N–A–S–H/C–A–S–H), matching the fc peak and reports for PLR-dominant matrices under controlled Ca inputs [

47,

54,

55].

4.7. Targeted Comparison with the Literature and Positioning of the Contribution

In PLR/BCR systems cured at 80–90 °C with 8–14 M NaOH, 40–60 MPa have been achieved; temperature and precursor fineness/porosity are decisive [

37,

38]. For PCR as a single precursor, <10–27 MPa values are frequent unless co-activated with MK or clinker and cured at 70 °C [

38,

39]. Our binary results confirm the synergy for low-to-intermediate PCR fractions, with a mechanical optimum emerging when Ca is sufficient to percolate C–A–S–H domains but not so high as to dilute the aluminosilicate stock and simplify mineralogy (quartz/portlandite) [

40,

41,

42,

54,

55,

56,

57]. This behavior aligns with studies reporting improvements at 20–50% PCR and penalties at higher substitutions, reinforcing that the origin of the maximum is not a mere “filler effect” but a co-crosslinking of C–A–S–H/N–A–S–H governed by chemical balance [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

48,

49,

55].

4.8. Activator Design and L/B Ratio: Robustness and Bounds

The NaOH/Na₂SiO₃/KOH activator (Mₛ ≈ 3.2) and L/B = 0.15 provide sufficient chemistry to deploy the synergy around 30% PCR. A higher L/B could improve workability but would likely raise porosity and lower fc; a higher Mₛ could increase polymerization (more available Si), albeit with risks of viscosity and early gelation; a lower Mₛ and/or higher KOH would tend to loosen the network and shift the optimal percentage, as inferred from activator-chemistry literature [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36] and from our tracers (FWHM/FTIR) at 30% PCR. However, to isolate the role of %PCR, the present work kept these variables constant, which is part of its methodological contribution.

4.9. Pore Architecture and Defectology: Origin of Deterioration at High PCR

The reappearance of microdefects (pores, microcracks) at 100% PCR suggests: (i) precipitation/growth of Ca-rich products (C–S–H, portlandite) that interrupt network co-continuity; (ii) mismatch of thermo-mechanical moduli among domains of different composition; and (iii) preferential secondary carbonation in high-Ca matrices, which may occlude fine pores but open connectivity via local stresses [

42,

47,

48,

49,

56,

57]. Altogether, this reduces effective load-bearing area and increases microcracking susceptibility, leading to a loss in fc.

4.10. Practical Implications: Quality Control and Scale-Up

The results delineate a design window centered at ≈30% PCR that maximizes densification and performance. For industrial scale-up, we recommend: (i) fast tracers (FTIR 1020–958 cm⁻¹ band and XRD FWHM) as process control; (ii) EDS quantification of Ca (at.%) to verify the Ca/Si–Al balance on receipt; (iii) ensuring adequate fineness and controlled inherited phases (quartz, albite) in PLR/PCR batches; and (iv) maintaining the curing protocol that guarantees the observed kinetic directionality [

37,

38,

50,

54,

55,

56,

57].

4.11. Limitations and Future Work

Activator and L/B were fixed, and neither fineness nor compositional variability of CDW was varied. Next steps include mapping (i) Mₛ and effective molarity of the activator, (ii) granulometry and mineralogy of PLR/PCR, and (iii) curing windows (T–time–RH), to tune C–A–S–H/N–A–S–H co-crosslinking and mitigate secondary carbonation, while preserving inter-study comparability [

37,

38,

39,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

54,

55,

56,

57].

5. Conclusions

5.1 ~30% PCR fraction. Under NaOH/Na₂SiO₃/KOH activation (Mₛ ≈ 3.2) and L/B = 0.15, the binary PLR–PCR pastes exhibited a local maximum in 28-day compressive strength of 16.2 MPa at 30% PCR, higher than 0% PCR (14.2 MPa) and clearly above PCR-rich formulations (≥50%), which showed systematic decreases (e.g., 13.8 MPa at 50%, 10.8–10.1 MPa at 70–100%).

5.2. Mechanism: N-A-S-H/C-A-S-H co-crosslinking. Ca supplied by PCR nucleates C-A-S-H domains that bridge and densify the N-A-S-H network (derived from PLR aluminosilicates), increasing connectivity and load-bearing capacity up to intermediate PCR fractions. Above ~30–50%, excess Ca²⁺ and reduced availability of reactive Si–Al species dilute the aluminosilicate network, promote C-S-H and/or secondary carbonation, and degrade fc.

5.3. XRD at ~30% PCR. At 28 days, 0% PCR exhibits a broad crystalline suite (kaolinite, quartz, albite, belite, calcite, gehlenite, anorthite). With 10–30% PCR, portlandite (~36.6° 2θ) emerges and the relative intensity of albite (29.54° 2θ) and other PLR phases decreases, indicating consumption/dilution of crystalline aluminosilicates and growth of the amorphous fraction associated with reaction gels; this is consistent with the fc peak at 30% PCR. At 100% PCR the pattern simplifies (quartz/portlandite dominant), reflecting Ca predominance and loss of crystalline diversity.

5.4. FTIR evidence of increased polymerization. For 0–10–30–100% PCR (28 d), the T–O–Si band (≈1020–958 cm⁻¹) intensifies at intermediate compositions, indicating greater network extent and densification; carbonates (≈1460–1380 cm⁻¹) increase with Ca, consistent with more prominent carbonation at high PCR. At 30% PCR, the 7→14→28 d evolution shows a sustained growth of T–O–Si, confirming condensation progress.

5.5. SEM–EDS microstructure: densification at 30% PCR. 28-day micrographs show a transition from porosity and microcracking (0% PCR) to a compact matrix with minimal defect population (10–30%), and then reappearance of microdefects at 100% PCR. EDS follows this trend: Ca (wt.%/at.%) increases from 0→30% PCR (favoring C-A-S-H) and is high at 100% PCR alongside a lower relative Al–Si fraction, consistent with heterogeneity and reduced co-continuity of the network.

5.6. Kinetics and curing. Pre-curing at 40 °C/72 h accelerates initial dissolution–condensation and gel formation; subsequent ambient curing consolidates the network, as reflected by the fc increase (7→14→28 d) and intensification of structural FTIR bands. The response depends on the Ca/Si–Al balance: beneficial around 30% PCR and counterproductive at high PCR contents.

5.7. Formulation and control implications. For reproducibility and process control, we recommend: (i) maintaining L/B = 0.15 and an activator with Mₛ ≈ 3.2; (ii) ensuring fineness < 75 μm for PLR/PCR to homogenize reactivity; (iii) monitoring T–O–Si (FTIR) and FWHM/amorphicity index (XRD) as rapid tracers of polymerization; and (iv) verifying Ca (EDS) in incoming batches to sustain the chemical balance that enables N-A-S-H/C-A-S-H synergy.

5.8. Scope and primary limitation. The study isolated the effect of %PCR by keeping activator and L/B constant; thus, it demonstrated that the best performance stems from chemical synergy and microstructural densification around 30% PCR, whereas deterioration at high PCR is associated with excess Ca, mineralogical simplification, and microdefect development. Future work should map Mₛ/molarity, granulometry/mineralogy, and curing windows to refine the optimal range and mitigate secondary carbonation.

The binary valorization of PCR/PLR enables geopolymeric binders with a lower carbon footprint and competitive mechanical/microstructural performance when the Ca contribution from PCR is moderated around ~30%. In that range, N-A-S-H/C-A-S-H co-formation maximizes matrix densification and compressive strength; outside it, Ca overloading dilutes reactive aluminosilicates, increases carbonates/C-S-H, and penalizes performance. These results provide transferable design and control criteria for CDW management in alternative cementitious materials.

Acknowledgments

To the National University of Trujillo, which through the CANON-2022 Competitive Fund Projects. “ALKALINE ACTIVATION OF PASTES AND MORTARS FROM CONSTRUCTION DEBRIS AND CALCAREOUS ORGANIC REMAINS FOR THEIR REUSE: A GREEN ALTERNATIVE TO THE PROBLEM OF CONSTRUCTION WASTE POLLUTION” and “ECOLOGICAL REINFORCEMENT BASED ON SANSEVIERIA TRIFASCIATA FIBERS FOR POLYESTER MATRICES AND ALKALINE CEMENT MORTARS: AN ENVIRONMENTALLY FRIENDLY AND SOCIALLY PROMOTING ALTERNATIVE” financed the equipment necessary for the results of this research article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

Materials and waste

RCD: Construction and Demolition Waste (Spanish acronym).

CDW: Construction and Demolition Waste (English equivalent of RCD).

PCR: Recycled Concrete Powder.

PLR: Recycled Brick Powder.

BCR: Recycled Ceramic Tiles (when citing tile-based literature).

MK: Metakaolin

Activators and chemistry

NaOH: Sodium hydroxide.

KOH: Potassium hydroxide.

Na₂SiO₃: Sodium silicate (commercial solution).

Mₛ: Silica modulus of sodium silicate (Mₛ = SiO₂/Na₂O).

L/B or l/a: Liquid-to-binder ratio (liquid/binder).

N-A-S-H: Sodium Aluminosilicate Hydrate (sodium aluminosilicate gel).

C-A-S-H: Calcium Aluminosilicate Hydrate (calcium aluminosilicate gel).

C-S-H: Calcium Silicate Hydrate (calcium silicate gel).

Properties and metrics

fc: Compressive strength (MPa).

SD: Standard deviation.

FWHM: Full Width at Half Maximum (in XRD).

I_Q(26.7°): Intensity of the quartz peak around 26.7° 2θ.

I_Pr(36.6°): Intensity of the portlandite peak around 36.6° 2θ.

d: Days (curing age, e.g., 7, 14, 28 d).

MPa: Megapascal (unit of stress).

References

- S. Iqbal, T. Naz, and M. Naseem, "Challenges and opportunities linked with waste management under global perspective: A mini review," Journal of Quality Assurance and Applied Sciences, vol. 1, pp. 9-13, 2021.

- M. Olofinnade, I. Manda, and A. N. Ede, "Management of construction & demolition waste: barriers and strategies to achieving good waste practice for developing countries," IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 1036, 2021.

- A. Akhtar and A. K. Sarmah, "Construction and demolition waste generation and properties of recycled aggregate concrete: A global perspective," Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 262, pp. 262-281, 2018.

- J. d. Oliveira, D. Schreiber, and V. D. Jahno, "Circular Economy and Buildings as Material Banks in Mitigation of Environmental Impacts from Construction and Demolition Waste," Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 12, p. 5022, 2024.

- INEI, "Perú: Anuario de Estadísticas Ambientales 2021," Lima, Perú, 2021.

- BCRP, “Caracterización del departamento de La Libertad,” Trujillo, Perú, 2023.

- M. M. Omer, R. A. Rahman, and S. Almutairi, "Construction waste recycling: Enhancement strategies and organization size," Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, vol. 126, p. 103114, 2022.

- Congreso de la República del Perú, "Ley General de Residuos Sólidos, Ley N° 1278," 2000.

- Ministerio del Ambiente del Perú, "Reglamento de la Ley General de Residuos Sólidos, Decreto Supremo N° 014-2017-MINAM," 2017.

- Ministerio del Ambiente del Perú, "Plan Nacional de Gestión Integral de Residuos Sólidos (PLANRES)," 2016.

- F. P. Torgal and J. A. Labrincha, "The future of construction materials research and the seventh UN Millennium development goal: a few insights," Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 40, pp. 729-737, 2013.

- M. Saghafi and Z. Teshnizi, "Recycling value of building materials in building assessment systems," Energy Build., vol. 43, no. 12, pp. 3181-3188, 2011.

- INEI, "Características de las viviendas particulares y los hogares, acceso a servicios básicos," 2018.

- Z. He, A. Shen, H. Wu, W. Wang, L. Wang, C. Yao, and J. Wu, "Research progress on recycled clay brick waste as an alternative to cement for sustainable construction materials," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 274, p. 122113, 2021.

- M. N. A. Khan, N. Liaqat, I. Ahmed, A. Basit, M. Umar, and M. A. Khan, "Effect of brick dust on strength and workability of concrete," IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng., vol. 414, pp. 1-6, 2018.

- V. Letelier, J. M. Ortega, P. Muñoz, E. Tarela, and G. Moriconi, "Influence of waste brick powder in the mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete," Sustainability, vol. 10, no. 1037, pp. 1-16, 2018.

- E. O. Fanijo, J. T. Kolawole, A. J. Babafemi, and J. Liu, "A comprehensive review on the use of recycled concrete aggregate for pavement construction: Properties, performance, and sustainability," Cleaner Materials, vol. 9, p. 100199, 2023.

- X. Ren and L. Zhang, "Experimental study of geopolymer concrete produced from waste concrete," J. Mater. Civ. Eng., vol. 31, pp. 1-14, 2019.

- P. Cong and Y. Cheng, "Advances in geopolymer materials: A comprehensive review," Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering (English Edition), vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 283-314, 2021.

- M. M. Madirisha, O. R. Dada, and B. D. Ikotun, "Chemical fundamentals of geopolymers in sustainable construction," Materials Today Sustainability, vol. 27, p. 100842, 2024.

- A. Allahverdi and E. N. Kani, "Construction wastes as raw materials for geopolymer binders," Int. J. Civ. Eng., vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 154-160, 2009.

- J. L. Gálvez-Martos, D. Styles, H. Schoenberger, and B. Zeschmar-Lahl, "Construction and demolition waste best management practice in Europe," Resour. Conserv. Recycl., vol. 136, pp. 166-178, 2018.

- K. Komnitsas, D. Zaharaki, A. Vlachou, G. Bartzas, and M. Galetakis, "Effect of synthesis parameters on the quality of construction and demolition wastes (CDW) geopolymers," Adv. Powder Technol., vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 368-376, 2015.

- C.-L. Hwang, M. D. Yehualaw, D. H. Vo, and T. P. Huynh, "Development of high strength alkali-activated pastes containing high volumes of waste brick and ceramic powders," Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 218, pp. 519-529, 2019.

- B. S. Mohammed, S. Haruna, M. M. A. Wahab, M. S. Liew, and A. Haruna, "Mechanical and microstructural properties of high calcium fly ash one-part geopolymer cement made with granular activator," Heliyon, vol. 5, no. 9, p. e02255, 2019.

- M. Panizza, M. Natali, E. Garbin, S. Tamburini, and M. Secco, "Assessment of geopolymers with Construction and Demolition Waste (CDW) aggregates as a building material," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 181, pp. 119-133, 2018.

- P. Cong and Y. Cheng, "Advances in geopolymer materials: A comprehensive review," Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering (English Edition), vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 283-314, 2021.

- H. K. Tchakouté, C. H. Rüscher, S. Kong, and others, "Thermal behavior of metakaolin-based geopolymer cements using sodium waterglass from rice husk ash and waste glass as alternative activators," Waste Biomass Valor, vol. 8, pp. 573-584, 2017.

- M. Dong, M. Elchalakani, and A. Karrech, "Development of high strength one-part geopolymer mortar using sodium metasilicate," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 236, p. 117611, 2020.

- M. N. S. Hadi, H. Zhang, and S. Parkinson, "Optimum mix design of geopolymer pastes and concretes cured in ambient condition based on compressive strength, setting time and workability," Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 23, pp. 301-313, 2019.

- C. Ma, B. Zhao, S. Guo, G. Long, and Y. Xie, "Properties and characterization of green one-part geopolymer activated by composite activators," Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 220, pp. 188-199, 2019.

- B. Singh, G. Ishwarya, M. Gupta, and S. K. Bhattacharyya, "Geopolymer concrete: A review of some recent developments," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 85, pp. 78-90, 2015.

- M. Askarian, Z. Tao, G. Adam, and B. Samali, "Mechanical properties of ambient cured one-part hybrid OPC-geopolymer concrete," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 186, pp. 330-337, 2018.

- B. Sri Umniati, P. Risdanareni, F. T. Zulfikar, and Z. Zein, "Workability enhancement of geopolymer concrete through the use of retarder," AIP Conf. Proc., vol. 1887, no. 1, p. 020033, Sep. 2017.

- G. Liang, H. Zhu, Z. Zhang, Q. Wu, and J. Du, "Investigation of the waterproof property of alkali-activated metakaolin geopolymer added with rice husk ash," Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 230, pp. 603-612, 2019.

- S. Saha and C. Rajasekaran, "Enhancement of the properties of fly ash based geopolymer paste by incorporating ground granulated blast furnace slag," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 146, pp. 615-620, 2017.

- K. Komnitsas, D. Zaharaki, A. Vlachou, G. Bartzas, and M. Galetakis, "Effect of synthesis parameters on the quality of construction and demolition wastes (CDW) geopolymers," Adv. Powder Technol., vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 368-376, 2015.

- D. Zaharaki, M. Galetakis, and K. Komnitsas, "Valorization of construction and demolition (C&D) and industrial wastes through alkali activation," Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 121, pp. 686-693, 2016.

- R. A. Robayo-Salazar, J. F. Rivera, and R. Mejía de Gutiérrez, "Alkali-activated building materials made with recycled construction and demolition wastes," Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 149, pp. 130-138, 2017.

- A. Allahverdi and E. N. Kani, "Use of construction and demolition waste (CDW) for alkali-activated or geopolymer cements," Construction and Demolition Waste, 2013.

- S. Ouda and M. Gharieb, "Development of the properties of brick geopolymer pastes using concrete waste incorporating dolomite aggregate," J. Build. Eng., vol. 27, p. 100919, 2020.

- S. Ouda and K. L. Abdel-Aal, "Effect of concrete waste on compressive strength and microstructure development of ceramic geopolymer pastes," Trans. Indian Ceram. Soc., vol. 78, no. 3, pp. 146-154, 2019.

- J. Zwaida, A. Dulaimi, N. Mashaan, and M. A. Othuman Mydin, "Geopolymers: The green alternative to traditional materials for engineering applications," Infrastructures, vol. 8, no. 6, p. 98, 2023.

- P. Cong and Y. Cheng, "Advances in geopolymer materials: A comprehensive review," Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering (English Edition), vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 283-314, 2021.

- X. Ren and L. Zhang, "Experimental study of geopolymer concrete produced from waste concrete," Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, vol. 31, no. 3, 2019.

- J. Qian and M. Song, "Study on influence of limestone powder on the fresh and hardened properties of early age metakaolin based geopolymer," Calcined Clays for Sustainable Concrete, K. Scrivener and A. Favier, Eds. RILEM Bookseries, vol. 10, Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 415-422, 2015.

- J. Yang, D. Li, and Y. Fang, "Effect of synthetic CaO-Al₂O₃-SiO₂-H₂O on the early-stage performance of alkali-activated slag," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 167, pp. 65-72, 2018.

- K. Yip, J. L. Provis, G. C. Lukey, and J. S. J. van Deventer, "Carbonate mineral addition to metakaolin-based geopolymers," Cement and Concrete Composites, vol. 30, no. 10, pp. 979-985, 2008.

- S. Ahmari, X. Ren, V. Toufigh, and L. Zhang, "Production of geopolymeric binder from blended waste concrete powder and fly ash," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 35, pp. 718-729, 2012.

- P. Duxson, A. Fernández-Jiménez, J. L. Provis, et al., "Geopolymer technology: the current state of the art," Journal of Materials Science, vol. 42, pp. 2917–2933, 2007.

- S. Iftikhar, K. Rashid, E. U. Haq, I. Zafar, F. K. Alqahtani, and M. I. Khan, "Synthesis and characterization of sustainable geopolymer green clay bricks: An alternative to burnt clay brick," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 259, p. 119659, 2020.

- N. Bih, A. Mahamat, C. Chinweze, O. Ayeni, J. B. Hounkpe, P. Onwualu, and E. Boakye, "The Effect of Bone Ash on the Physio-Chemical and Mechanical Properties of Clay Ceramic Bricks," Buildings, vol. 12, p. 336, 2022.

- X. Li, A. Wanner, C. Hesse, S. Friesen, and J. Dengler, "Clinker-free cement based on calcined clay, slag, portlandite, anhydrite, and C-S-H seeding: An SCM-based low-carbon cementitious binder approach," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 442, p. 137546, 2024.

- M. Vafaei and A. Allahverdi, "Influence of calcium aluminate cement on geopolymerization of natural pozzolan," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 114, pp. 290-296, 2016.

- Mahmoodi, H. Siad, M. Lachemi, and M. Sahmaran, "Synthesis and optimization of binary systems of brick and concrete wastes geopolymers at ambient environment," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 276, p. 122217, 2021.

- A. Kar, "Characterizations of concretes with alkali-activated binder and correlating their properties from micro- to specimen level," 2013.

- A. Xue, A. Shen, Y. Guo, and T. He, "Utilization of construction waste composite powder materials as cementitious materials in small-scale prefabricated concrete," Advances in Materials Science and Engineering. 2016.

- J. E. Oh, Y. Jun, and Y. Jeong, "Characterization of geopolymers from compositionally and physically different Class F fly ashes," Cement and Concrete Composites, vol. 50, pp. 16-26, 2014.

- H. Castillo, H. Collado, T. Droguett, S. Sánchez, M. Vesely, P. Garrido, and S. Palma, "Factors affecting the compressive strength of geopolymers: A review," Minerals, vol. 11, no. 12, p. 1317, 2021.

- R. Sonnier, R. El Hage, P. Hage, S. Beaino, and S. Seif, "Novel foaming-agent free insulating geopolymer based on industrial fly ash and rice husk," Molecules, vol. 27, pp. 1-19, 2022.

- Y. Zhang, W. Sun, Q. Chen, and L. Chen, "Synthesis and heavy metal immobilization behaviors of slag based geopolymer," Journal of Hazardous Materials, vol. 143, no. 1-2, pp. 206-213, 2007.

- Mahmoodi, H. Siad, M. Lachemi, S. Dadsetan, and M. Sahmaran, "Development of normal and very high strength geopolymer binders based on concrete waste at ambient environment," Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 279, p. 123436, 2021.

- J.S.J. van Deventer, J.L. Provis, P. Duxson, and G.C. Lukey, "Reaction mechanisms in the geopolymeric conversion of inorganic waste to useful products," Journal of Hazardous Materials, vol. 139, no. 3, pp. 506-513, 2007.

- J. M. Mejía, R. Mejía de Gutiérrez, and C. Montes, "Rice husk ash and spent diatomaceous earth as a source of silica to fabricate a geopolymeric binary binder," Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 118, pp. 133-139, 2016.

- P. Chindaprasirt, C. Jaturapitakkul, W. Chalee, and U. Rattanasak, "Comparative study on the characteristics of fly ash and bottom ash geopolymers," Waste Management, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 539-543, 2009.

- L. Heller-Kallai and I. Lapides, "Reactions of kaolinites and metakaolinites with NaOH—comparison of different samples (Part 1)," Applied Clay Science, vol. 35, pp. 99-107, 2007.

- M. Tuyan, Ö. Andiç-Çakir, and K. Ramyar, "Effect of alkali activator concentration and curing condition on strength and microstructure of waste clay brick powder-based geopolymer," Composites Part B: Engineering, vol. 135, pp. 242-252, 2018.

- H. Khater, "Effect of Calcium on Geopolymerization of Aluminosilicate Wastes," Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, vol. 24, pp. 92-101, 2012.

- V.H.J. Mendes dos Santos, D. Pontin, G.G.D. Ponzi, A.S. de Guimarães e Stepanha, R.B. Martel, M.K. Schütz, S.M. Oliveira Einloft, F. Dalla Vecchia, "Application of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Coupled with Multivariate Regression for Calcium Carbonate (CaCO3) Quantification in Cement," Construction and Building Materials, vol. 313, p. 125413, 2021.

- A. Hajimohammadi, J. L. Provis, and J. V. Deventer, "One-Part Geopolymer Mixes from Geothermal Silica and Sodium Aluminate," Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, vol. 47, pp. 9396-9405, 2008.

- K. Somna, C. Jaturapitakkul, P. Kajitvichyanukul, and P. Chindaprasirt, "NaOH-activated ground fly ash geopolymer cured at ambient temperature," Fuel, vol. 90, no. 6, pp. 2118-2124, 2011.

- H. R. Razeghi, F. Safaee, A. Geranghadr, et al., "Investigating accelerated carbonation for alkali activated slag stabilized sandy soil," Geotech. Geol. Eng., vol. 42, pp. 575–592, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).