1. Introduction

The search for a quantum theory of gravity has traditionally begun from a single, rarely questioned premise: that the spacetime metric of general relativity is a fundamental field which must be quantized. This premise underlies canonical quantization, loop variables, spin foams, string theory, causal sets, and related approaches [

4,

10,

74,

78,

86]. Yet no observation has ever revealed quantum excitations of the metric, discrete geometric spectra, or “gravitons” in the same sense that photons and gluons appear as quanta of underlying gauge fields. Several persistent conceptual difficulties in quantum gravity—including the problem of time, perturbative nonrenormalizability, and the absence of local gauge-invariant observables—are naturally reinterpreted as indications that the metric is a

macroscopic, not microscopic, variable [

47,

55,

89].

This perspective aligns with a growing body of work suggesting that spacetime geometry may function as a collective or hydrodynamic descriptor, analogous to pressure, density, or vorticity in a fluid. Quantizing such variables can be formally carried out, but it does not describe the true microscopic degrees of freedom. If the metric arises only as a coarse-grained descriptor of deeper dynamics, its quantization becomes conceptually inappropriate [

12,

44].

Emergent-gravity frameworks—including analogue systems, induced gravity, entropic and thermodynamic approaches, and holographic dualities [

43,

49,

71,

79,

88,

91]—reinforce this view. The fundamental task is therefore not to quantize geometry, but to identify the microscopic structure from which geometry itself emerges.

In this work we investigate one concrete proposal for such a substrate: Chronon Field Theory (CFT). CFT is built on a single dynamical field, a smooth unit timelike covector , governed by the Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP), which posits that nature tends to maximize local coherence in the direction of causal propagation. Variation of the TCP action produces a unified field equation whose long-wavelength limits recover:

the Einstein equations as the hydrodynamic response of an aligned causal medium [

49,

71],

Maxwell and Yang–Mills dynamics as holonomies of the transverse polarization bundle of

[

29,

50],

the Schrödinger equation and the action quantum

from chronon-vorticity topology [

20,

38,

66],

Navier–Stokes–type fluid behavior from slow-time relaxation of misalignment [

12,

56].

Although selects a preferred causal direction, CFT does not predict observable violations of Lorentz invariance. This is ensured by the Co-Moving Concealment Principle (CCP):

Co-Moving Concealment Principle (CCP). All excitations and interactions propagate co-moving with the local chronon frame defined by . Because the emergent metric is constructed from itself, every observer and every field samples the same local frame. Thus the preferred direction is dynamically hidden, and all observable processes are locally Lorentz invariant.

In CFT, nothing is imposed from outside: the chronon medium generates the metric, governs all excitations, and determines the operational standard of locality and speed. Lorentz symmetry survives observationally because all dynamics co-move with the same substrate.

This leads to two central claims explored in this paper:

Spacetime geometry is a derived, hydrodynamic quantity; it should not be quantized because it is not fundamental.

A unified description of gravity, gauge interactions, and quantum mechanics emerges once the underlying causal medium is modeled explicitly.

The remainder of the paper develops these results.

Section 3 introduces the TCP framework and its variational structure.

Section 4 shows how the Einstein–Hilbert action and Newton’s constant arise from the alignment dynamics of

.

Section 5 derives quantum wave equations and the geometric action scale

.

Section 6 explains why long-standing quantum-gravity puzzles disappear once geometry is emergent.

Section 7 summarizes observational signatures arising from the quartic vorticity term.

2. Why Geometry Need Not Be Quantized

The widespread expectation that gravity must be quantized arises from extending canonical quantization to the metric field [

22,

97]. This expectation is natural but not necessary: it presumes that

is a microscopic dynamical field on par with gauge fields. In this section we present three lines of reasoning suggesting that the metric is instead a

macroscopic variable and therefore not an appropriate target for quantization: (i) geometry behaves as an emergent collective descriptor, (ii) no experiment has detected quantum features of spacetime, and (iii) the perturbative nonrenormalizability of general relativity indicates that the metric is not a fundamental degree of freedom [

17,

23].

2.1. Geometry as an Emergent, Not Microscopic, Variable

In many-body systems, continuum variables such as pressure, temperature, vorticity, and strain summarize large-scale organization of microscopic constituents. These quantities are indispensable for macroscopic physics but do not exist as independent quantum degrees of freedom. Quantizing them directly—for example, the Navier–Stokes velocity field—produces theories with no microscopic interpretation.

We argue that the spacetime metric is of the same type. The quantity encodes the coarse-grained coherence of an underlying physical substrate that determines causal propagation. Its curvature reflects how the local orientation of this substrate varies across spacetime, in the same way that geometric strain reflects microscopic alignment in an elastic solid.

This viewpoint is consistent with several emergent-gravity ideas: Sakharov’s induced gravity [

79], Jacobson’s thermodynamic derivation of the Einstein equation [

49], analogue-gravity frameworks [

12], and hydrodynamic or entropic interpretations of spacetime [

71,

91]. Across these approaches, the metric functions as a collective variable, not a microscopic one.

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) makes this structure explicit: the fundamental field is the smooth timelike covector , while the metric and curvature emerge from the coherent organization of over large scales. Quantizing in such a framework would be as unnatural as quantizing the temperature field of a fluid.

2.2. No Experimental Evidence for Quantized Spacetime

Decades of increasingly precise observations have revealed no sign of quantized geometry, discrete spacetime elements, or metric excitations. Illustrative examples include:

Interferometry. LIGO, VIRGO, GEO600, atom interferometers, and Holometer-like searches show no Planck-scale stochastic jitter at sensitivities far beyond those predicted by naive discrete-spacetime models [

11,

42].

Lorentz-invariance tests. Observations of cosmic rays, GRBs, blazar spectra, and high-energy neutrinos reveal no dispersion anomalies down to fractional levels

[

5,

25,

51].

Vacuum birefringence. Polarization measurements from distant astrophysical sources place extremely tight bounds on metric-induced birefringence [

53].

Absence of graviton signatures. No direct or indirect evidence of quantized metric excitations has been observed, despite the ubiquitous manifestation of analogous quanta (photons, phonons, magnons) in their respective domains [

24].

While these results do not preclude quantum gravity in principle, they strongly suggest that spacetime is smooth down to scales probed experimentally, supporting the interpretation that geometry is a collective field rather than a quantum one.

2.3. Nonrenormalizability as Evidence of Emergent Variables

Perturbative quantization of the Einstein–Hilbert action yields a nonrenormalizable theory [

34]: new divergences appear at every loop order, requiring infinitely many counterterms. Rather than signaling a fundamental flaw, this behavior fits a familiar pattern: in effective field theory, nonrenormalizability typically means that the chosen fields are not the underlying microscopic degrees of freedom [

96].

Quantizing fluid velocity or strain, for example, also leads to nonrenormalizable theories because those variables are emergent. General relativity exhibits this same structure. Its ultraviolet divergences arise because is a hydrodynamic field whose microscopic origin lies elsewhere.

From this viewpoint, the problem is not that gravity resists quantization, but that the metric is not the correct variable to quantize. Once the underlying degrees of freedom are identified—as in analogue models, thermodynamic derivations, or, in this work, the chronon field—the need to quantize geometry evaporates.

In CFT, the fundamental dynamics are formulated directly in terms of . The metric emerges from coarse-grained alignment of , and the quartic vorticity term in the TCP Lagrangian provides a natural regularizing scale associated with finite-energy solitonic excitations. General relativity thus appears as a long-wavelength approximation to a more fundamental theory, and its nonrenormalizability is reinterpreted as a diagnostic of emergent, not fundamental, variables.

3. Chronon Field Theory as the Underlying Substrate

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) posits that the microscopic structure of the universe is described not by a fundamental metric field but by a single, smooth, future-directed, unit timelike covector field

whose orientation defines the local direction of causal propagation. The unit constraint (

1) ensures that

generates a congruence of timelike curves in the sense of standard Lorentzian geometry [

21,

93].

A key conceptual shift is that the metric

is

not assumed

a priori. Instead, we treat

as an auxiliary differentiable structure and show in

Section 4 and

Section 5 that the unique metric rendering

unit-timelike while making the TCP dynamics hyperbolic is precisely the emergent Lorentzian metric. This “bootstrap” construction parallels analogue-gravity frameworks, where effective metrics arise from coherent microscopic alignment rather than being fundamental geometric objects [

12,

45,

92].

The Temporal Coherence Principle

At the core of CFT is the

Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP), which states that neighboring causal directions tend to align. Misalignment carries an energetic cost, analogous to gradient energy in nonlinear

-models and spin alignment in condensed matter systems [

60].

This principle is encoded in the TCP Lagrangian

where the vorticity tensor

is the antisymmetric part of the chronon gradient, analogous to kinematic vorticity in relativistic hydrodynamics [

7].

The three TCP parameters have distinct physical roles:

is the stiffness of the causal medium, controlling the energy cost of misalignment.

dynamically enforces the unit-norm constraint, exactly as in constrained -models.

weights quartic vorticity, providing a short-distance regulator similar to Skyrme-type terms that stabilize solitons [

3,

81].

The competition between

J and

sets the coherence scale

analogous to characteristic lengths in classical soliton theory.

3.1. Microscopic Interpretations

CFT is formulated as a continuum field theory, and none of its results require committing to a particular microphysical model. However, one may interpret as the coarse-grained order parameter of a deeper, discrete or statistical substrate, in analogy with how macroscopic fields arise in nematic liquid crystals or spin systems.

Any such microscopic realization must, upon coarse-graining, yield a smooth timelike field with an effective action matching Eq. (

2). Possible mechanisms include stochastic local alignment rules, nematic-type orientation variables, or other pregeometric models; a detailed construction is beyond the scope of this paper and will be presented elsewhere. For the present work, CFT is treated as a self-contained continuum theory whose variational principle defines the underlying dynamics.

3.2. TCP Field Equations

Varying

with respect to

yields the full Euler–Lagrange equation

where

is third order in derivatives and arises from varying the quartic vorticity term. When vorticity is small compared to the coherence scale,

, the equation reduces to the leading form

which acts as the

Root Equation governing chronon alignment.

3.3. Linearized Dynamics

Linearizing around a coherent background

with

and

gives

where

is the second-variation coefficient of the constraint. In a local rest frame of

,

a manifestly hyperbolic evolution system.

3.4. Emergent Propagation Speed

The corresponding dispersion relation is

so all small-amplitude excitations propagate with the

universal constitutive speed

Subleading

corrections arise only near the coherence scale

.

This universality provides the mechanism by which CFT explains the equality of propagation speeds for gravitational, gauge, and quantum excitations (

Section 6).

4. Emergent Gravity from TCP

A central prediction of Chronon Field Theory (CFT) is that the Einstein field equations arise not as postulates but as the long-wavelength, low-vorticity limit of the Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP). In this view, gravity is the hydrodynamic response of the chronon field

to distortions of causal alignment, in close analogy with emergent-gravity and analogue-gravity frameworks in which effective geometry arises from collective microscopic behavior [

12,

45,

92].

To formalize this, we assume temporarily that

is hypersurface-orthogonal,

the Frobenius condition [

93], which guarantees that spacetime admits a foliation by hypersurfaces

orthogonal to

. This allows

to be decomposed into purely spatial and temporal components using standard

geometry techniques [

35].

4.1. Geometric Decomposition of the Chronon Gradient

Define the induced spatial metric

and the extrinsic curvature of the foliation,

together with the acceleration

A standard identity from

decomposition yields the exact relation

as presented in canonical references on GR foliation theory [

35,

93].

This identity is purely kinematical; however, in CFT it becomes dynamical because the TCP Lagrangian depends directly on .

4.2. ADM Structure from the TCP Quadratic Term

Substituting (

12) into the quadratic TCP energy,

and using

gives the decomposition

where the divergence term depends on foliation gauge but does not affect the equations of motion.

The combination

is precisely the ADM kinetic term of general relativity, as derived in Refs. [

2,

100]. Thus the kinematic part of the Einstein–Hilbert action emerges directly from chronon alignment dynamics.

4.3. Gauss–Codazzi and the Long-Wavelength Limit

The Gauss–Codazzi identity [

35,

93] relates the four-dimensional Ricci scalar to the intrinsic and extrinsic geometry of the slices:

Comparing (

14) with the TCP structure (

13), we see that the TCP quadratic term becomes dynamically equivalent to the Einstein–Hilbert kinetic term whenever the intrinsic 3-curvature is suppressed:

i.e., when curvature varies slowly relative to the coherence length

set by the quartic TCP term (

Appendix A).

Under this coarse-graining, the effective action becomes

which matches the Einstein–Hilbert action at leading order.

4.4. Emergent Newton Constant

Comparing (

16) with the standard action

yields the identification

Thus the Newton constant is not fundamental—it is the inverse stiffness of the causal medium. Larger

J corresponds to weaker gravitational coupling, exactly as expected in induced-gravity and emergent-gravity theories [

49,

71,

79].

Variation of the effective action leads to the emergent Einstein equations:

with corrections from the quartic vorticity term suppressed when

.

4.5. Dynamical Selection of Lorentzian Signature

A notable consequence of CFT is that Lorentzian signature

emerges as the

unique dynamically stable phase. Expanding the quadratic TCP energy to second order around a coherent background gives

analogous to hyperbolicity analyses in relativistic field theory [

21,

93].

This quadratic form is bounded below only if:

Euclidean signature fails to distinguish a causal direction, producing rotational instabilities. Mixed signatures such as yield unbounded spatial-gradient energy and ghostlike excitations. Thus Lorentzian signature is the only hyperbolically stable phase of the chronon medium.

Summary

The TCP formalism reproduces the full structure of general relativity as the macroscopic hydrodynamics of chronon alignment:

the Einstein–Hilbert action emerges from chronon gradient energy;

Newton’s constant appears as ;

Einstein’s equations follow from coarse-grained variation;

Lorentzian signature is dynamically selected.

Gravity therefore appears as the elastic response of a deeper causal medium, not a fundamental quantum field.

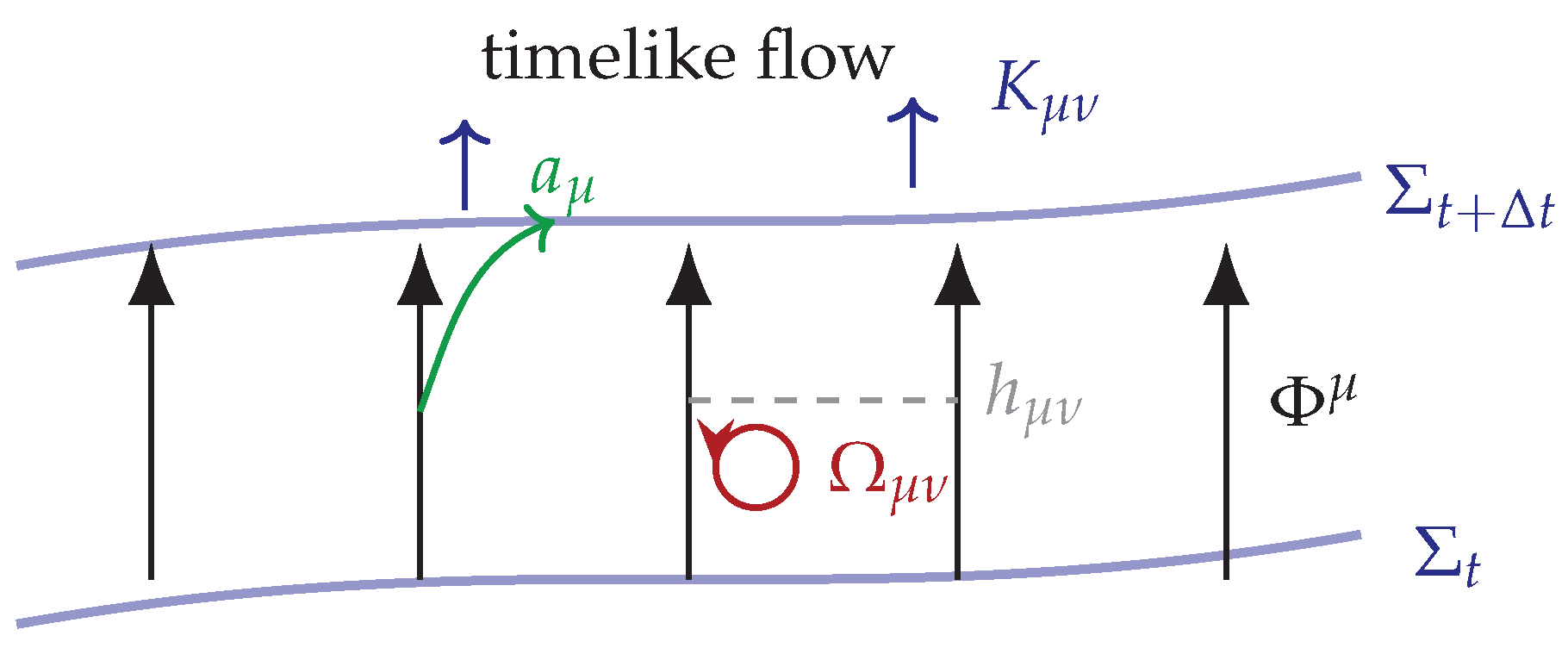

Figure 1.

Geometric structure induced by the chronon field . Integral curves of generate a foliation of spacetime into spacelike hypersurfaces . The projector maps tensors onto the transverse 3–surface. The extrinsic curvature describes the bending of successive slices, while the acceleration and vorticity characterize deviations from geodesic and irrotational flow.

Figure 1.

Geometric structure induced by the chronon field . Integral curves of generate a foliation of spacetime into spacelike hypersurfaces . The projector maps tensors onto the transverse 3–surface. The extrinsic curvature describes the bending of successive slices, while the acceleration and vorticity characterize deviations from geodesic and irrotational flow.

5. Emergent Quantum Mechanics from TCP

In Chronon Field Theory (CFT), quantum dynamics arise not from canonical quantization or operator postulates, but from the linearized, phase-coherent regime of the Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP). When the chronon field undergoes small oscillations about a coherent, stationary background, the resulting perturbations propagate as hyperbolic waves with a well-defined phase, analogous to emergent collective excitations in condensed-matter systems [

12,

92]. The eikonal limit of these waves yields the Hamilton–Jacobi equation, as in standard WKB theory [

16,

61], whose paraxial expansion reproduces the Schrödinger equation. Finally, topological quantization of chronon vorticity parallels vortex quantization in superfluids and gauge defects [

28,

70], and fixes the emergent action unit

.

This section derives these results systematically and makes explicit the assumptions under which quantum theory emerges.

5.1. Linearization and the Hyperbolic Wave Equation

Let

be a stationary, coherent background satisfying

. We parametrize small fluctuations by

To linearize the TCP equation (

5), we work in a local rest frame of the background,

and impose the transverse gauge

which removes unphysical perturbations along the chronon direction.

Expanding the TCP action to quadratic order gives, for the spatial components

,

a hyperbolic wave equation similar to excitations in nonlinear

-models [

31,

76].

5.2. Eikonal Expansion and the Hamilton–Jacobi Equation

To extract the phase dynamics, we introduce a WKB ansatz for each transverse polarization [

16,

54,

94]:

Inserting this into (

20) produces a hierarchy in powers of

. The highest-order terms yield the

eikonal equation

which is precisely the relativistic Hamilton–Jacobi equation familiar from semiclassical gravity [

64].

5.3. Paraxial Limit: Nonrelativistic Hamilton–Jacobi Equation

Write the phase as

and expand (

21) in the paraxial limit to obtain

the standard nonrelativistic Hamilton–Jacobi equation [

33].

5.4. Emergence of Schrödinger Dynamics

Define the wavefunction

as in the Madelung hydrodynamic interpretation [

15,

62].

Using (

22) gives

which is the Schrödinger equation.

Thus nonrelativistic quantum mechanics emerges as the paraxial, phase-coherent limit of chronon dynamics.

5.5. Topological Origin of the Action Quantum

The vorticity tensor,

defines a flux through any closed two-surface. Single-valuedness of the chronon phase enforces the quantization rule

directly analogous to vortex flux quantization in superfluids and superconductors [

28,

68,

70].

Using the coherence scale

and the typical vorticity amplitude

yields

up to an order-unity prefactor, similar to geometric quantization of topological defects [

92,

102].

Summary

Chronon Field Theory yields quantum mechanics through:

hyperbolic chronon waves with universal speed ,

a WKB expansion producing the Hamilton–Jacobi equation,

a paraxial expansion yielding the Schrödinger equation,

vorticity-flux quantization producing the action unit .

Thus quantum mechanics is the harmonic limit of a deeper causal medium, not a fundamental postulate.

6. Problems Quantum Gravity Cannot Solve but CFT Can

Traditional quantum-gravity programs—including string theory [

36,

74], loop quantum gravity [

78,

86], spin foams [

72], causal sets [

14,

84], and canonical quantization of the metric [

9,

22]— begin by treating the spacetime metric as a fundamental degree of freedom. The aim is then to quantize this metric, either by promoting its components to operators or by summing over discrete geometries in a path-integral framework.

However, several of the deepest conceptual puzzles motivating quantum gravity concern features of spacetime that cannot be explained if one starts from a fundamental metric. Any theory that assumes a metric a priori necessarily inherits:

a fixed causal structure (one null cone),

a fixed action scale (Planck’s constant),

a fixed signature (),

and therefore cannot explain their origins without circularity [

18,

77].

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) [

58,

59], by contrast, does not assume a metric. Metric structure, causal cones, and the action scale emerge dynamically from the coherence properties of the chronon medium governed by the Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP). This allows CFT to address three conceptual problems that are inaccessible to metric-first quantum-gravity approaches.

6.1. Universality of the Invariant Speed

In metric-based quantum gravity, all matter and gauge fields are

defined to propagate on the same background geometry. Thus the equalities

hold by construction, not explanation. Quantum gravity begins with a Lorentzian metric

; therefore all null cones coincide by definition.

Nothing in such a framework explains

why nature has a single universal invariant speed, a point emphasized in discussions of emergent Lorentz symmetry [

12,

57].

Chronon Field Theory. In CFT the invariant speed is not postulated. It emerges because all propagating excitations—gravitational, electromagnetic, quantum, or matterlike—arise from linearized fluctuations of the same causal substrate .

The dispersion relation derived in

Section 5 reads:

for

all small-amplitude perturbations.

Thus:

a constitutive property of the chronon medium rather than a geometric axiom.

Metric-first quantum gravity cannot derive the universality of c without assuming it; CFT derives it from the TCP alone.

6.2. Origin of Planck’s Constant

Canonical quantization, LQG, and string theory all introduce Planck’s constant

ℏ at the first step, through the replacement

or by inserting

ℏ in the worldsheet or canonical action [

36,

86]. Thus

ℏ controls the deformation of classical mechanics but is taken as an

assumed input. These approaches cannot answer the conceptual questions:

Chronon Field Theory. In CFT the action quantum arises from topological properties of the chronon field, analogous to quantized circulation in superfluids [

28,

70] and quantized magnetic flux in superconductors [

87]. The vorticity tensor

admits a quantized flux:

directly analogous to quantized circulation.

Since stable vorticity excitations have size

and magnitude

, and since

, CFT predicts:

establishing the analog of Planck’s constant as a property of the causal substrate.

Quantum gravity frameworks cannot derive ℏ because they are built using ℏ; CFT derives it from chronon-flux quantization.

6.3. Stability of Lorentzian Signature

Metric-first approaches assume the Lorentzian signature

as part of the kinematic starting point. Even Euclidean path-integral programs require Wick rotation back to Lorentzian signature for physical predictions [

32]. No mechanism explains why nature selects a Lorentzian causal structure instead of Euclidean or

signatures [

8,

39].

Chronon Field Theory. In CFT the signature is not assumed; it is dynamically selected. The second variation of the TCP energy yields:

For stability:

there must be exactly one negative direction (time),

spatial directions must be positive,

Euclidean signature produces elliptic evolution,

signature yields ghosts and unbounded gradient energy, consistent with general results on signature stability [

13,

98].

Thus the Lorentzian signature is the unique stable phase of the chronon medium.

Summary

Metric-based quantum gravity frameworks begin by assuming the basic structures of spacetime: a universal null cone, a fixed action quantum, and a Lorentzian signature. They therefore cannot explain these structures without circularity.

Chronon Field Theory, based on a real causal substrate with constitutive parameters , explains all three as emergent:

A universal invariant speed arises from chronon-wave dispersion.

An action quantum arises from vorticity flux quantization.

Lorentzian signature is the unique dynamically stable phase of the chronon medium.

These are not postulates but unavoidable consequences of the Temporal Coherence Principle.

7. Phenomenological Consequences

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) predicts small but potentially observable

corrections to the propagation of massless excitations. Although the TCP dynamics reproduce exact local Lorentz invariance at leading order—via the comoving concealment mechanism—the quartic vorticity term introduces suppressed higher-derivative operators, analogous in structure to dimension-6 operators in the Standard Model Extension (SME) and EFT treatments of Lorentz-violating dispersion [

5,

52]. These produce tiny dispersive effects whose influence can accumulate across cosmological distances, a scenario already heavily constrained in astrophysical analyses [

26,

80].

This section summarizes the most promising observational signatures and the assumptions under which they arise.

7.1. Vacuum Dispersion from the TCP Equation

The quartic vorticity term in the TCP Lagrangian,

generates higher-derivative corrections in the linearized equation for transverse excitations. To leading order in

, the corrected dispersion relation takes the form

where

depends on polarization and background foliation. This same

structure appears in Lorentz-violating dispersion analyses in quantum-gravity phenomenology [

57,

63], but here it is not an EFT addition: it arises directly from the TCP action.

The corresponding group velocity is

Thus, all massless excitations propagate at the universal speed

to leading order, but acquire a frequency-dependent

correction. The equivalent refractive index,

resembles SME-type dispersion but is derived from the TCP rather than added by hand.

7.2. Cosmological Accumulation and Order-of-Magnitude Estimates

For a signal emitted at frequency

and propagating over a distance

D along a nearly homogeneous background, the arrival-time difference between two frequencies

and

is

neglecting redshift corrections. Similar expressions appear in QG-dispersion analyses of gamma-ray bursts and FRBs [

5,

26].

For a bright FRB at redshift

(

), with frequencies

and

and timing precision

, we obtain

FRB analyses already constrain similar dispersive effects at

–

s precision [

73,

101].

The CFT prediction scales as , in sharp contrast to plasma dispersion (), allowing a clean observational discriminant.

7.3. Candidate Observational Tests

The combination governs the quartic vorticity term across all massless excitations, yielding a cross-channel suite of observational tests.

-

Photon–gravitational-wave coincidence from compact mergers.

Timing analyses such as GW170817 [

37] constrain frequency-dependent photon/GW delays at the ms level across

Mpc. Next-generation events out to 500 Mpc can probe the CFT-predicted delay scaling

.

-

Fast radio bursts (FRBs).

Sub-ms timing at 1–30 GHz [

73] makes FRBs an ideal probe. Stacked analyses across many bursts suppress systematics [

101]. The CFT signature is orthogonal to standard astrophysical dispersion.

-

High-energy neutrinos from cosmological transients.

IceCube observations of PeV-scale neutrinos from blazars and GRBs [

46] already constrain multi-messenger timing at ∼seconds across Gpc distances. If neutrino-like excitations couple differently to

, their arrival structure provides a complementary bound.

All these tests constrain the same underlying quantity , providing a unified phenomenological window into the causal substrate described by the Temporal Coherence Principle.

8. Discussion: Unification by Emergence

The central claim of this work is that the long-standing tension between General Relativity (GR) and Quantum Mechanics (QM) is not a fundamental inconsistency in nature, but a consequence of treating the spacetime metric as a microscopic degree of freedom. A wide range of emergent-gravity ideas—including analogue-gravity frameworks [

12], induced gravity [

79], entropic approaches [

49], and holographic dualities [

91]—suggests that geometric variables may play a collective or hydrodynamic role. Chronon Field Theory (CFT), based on the Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP), implements this idea explicitly: a single dynamical field

produces geometry, gravity, gauge interactions, and quantum behavior as complementary limits.

Under the TCP, the apparent diversity of physical laws reflects different coherence, curvature, and wavelength regimes of a single substrate. In this sense, GR and QM emerge from the same physical mechanism, and the metric is a derived quantity akin to hydrodynamic variables in a fluid.

8.1. Gravity and Quantum Mechanics as Complementary Limits

In the low-curvature, slowly varying regime, the quadratic part of the TCP Lagrangian reproduces the Einstein–Hilbert action with an effective Newton constant

, showing that GR is the hydrodynamic limit of temporal alignment. Related hydrodynamic derivations of gravitational dynamics appear in entropic and thermodynamic approaches [

49,

71].

In the high-coherence, long-wavelength regime, linear excitations of

satisfy a Hamilton–Jacobi relation whose eikonal expansion yields the Schrödinger equation, following the logic of quantum-from-ensemble and WKB emergent approaches [

20,

38,

66]. The resulting geometric action quantum

arises topologically from chronon vorticity.

Thus quantum theory and gravity appear not as incompatible frameworks but as distinct macroscopic approximations of a single microscopic principle.

8.2. Geometry as a Derived Quantity

The metric

arises from correlation properties of the chronon field rather than serving as a fundamental input. This view coheres with induced-gravity and analogue-gravity programs [

12,

79], which likewise interpret metric geometry as a collective descriptor.

Lorentzian signature and the invariant speed

emerge naturally from stability of the chronon medium, paralleling arguments in analogue systems where causal cones arise from dispersion relations [

12]. Because all fields, detectors, and excitations arise from the same substrate, a comoving-concealment mechanism enforces operational Lorentz symmetry, similar in spirit to the equivalence of co-moving frames in condensed-matter analogues.

8.3. The Need for a Causal Substrate

A substrate-based view resolves several conceptual puzzles that plague metric-first quantum gravity:

These features follow automatically from the TCP equation and need not be imposed.

8.4. Beyond Gravity and Quantum Mechanics

CFT extends the emergent perspective to gauge interactions and hydrodynamics.

Appendix A shows how:

and gauge fields arise from transverse holonomies of ,

Yang–Mills equations emerge from the antisymmetric sector of the TCP,

Navier–Stokes equations arise in the dissipative limit.

This reinforces the interpretation of CFT as a unified causal substrate from which diverse physical laws emerge as effective limits.

8.5. Conceptual Implications

CFT reframes the goal of unification. Rather than quantizing the metric or searching for a fundamental graviton, one identifies the underlying field whose coherence dynamics generate both GR and QM. The perceived incompatibility between the two theories then dissolves: they are distinct windows onto the same causal medium.

Unification in this picture occurs not through quantization of geometry but through emergence from a single coherence principle. “Gravity and quantum theory are complementary limits of one substrate” becomes a structural rather than philosophical statement.

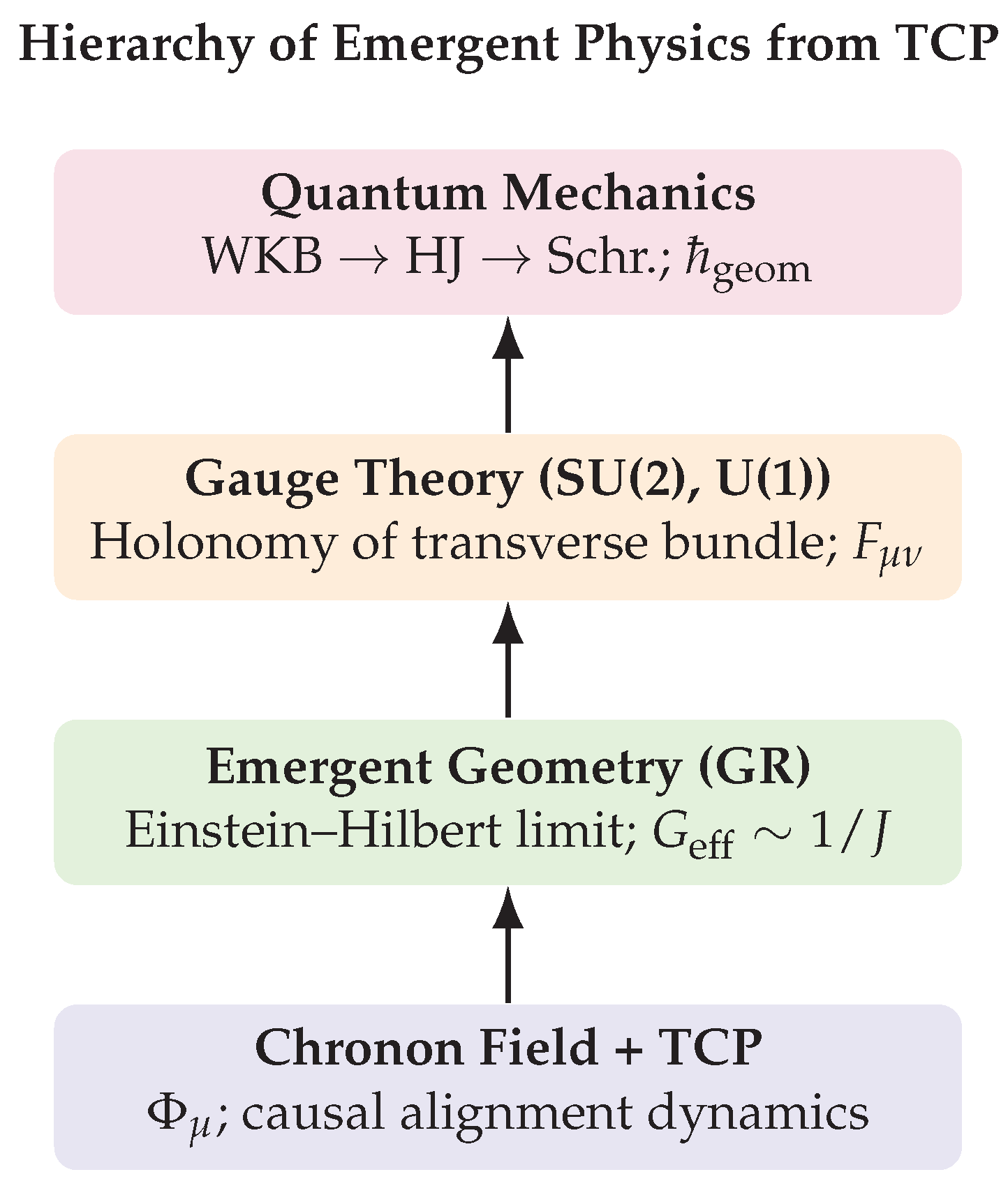

Figure 2.

Compact schematic of the emergent hierarchy in Chronon Field Theory. The chronon field and the TCP action form the microscopic substrate. General relativity, gauge theory, and quantum mechanics appear as successive large-scale limits: geometric alignment (GR), holonomy of transverse polarization (SU(2), U(1)), and paraxial/topological phase structure (quantum mechanics).

Figure 2.

Compact schematic of the emergent hierarchy in Chronon Field Theory. The chronon field and the TCP action form the microscopic substrate. General relativity, gauge theory, and quantum mechanics appear as successive large-scale limits: geometric alignment (GR), holonomy of transverse polarization (SU(2), U(1)), and paraxial/topological phase structure (quantum mechanics).

9. Conclusion

The historical pursuit of quantum gravity has rested on the assumption that the spacetime metric must be quantized to reconcile GR with QM. This paper has argued that this assumption is unnecessary. In Chronon Field Theory, the metric is not fundamental but an emergent descriptor of the coherent regime of a causal medium. General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics arise as different limits of the same underlying TCP dynamics, eliminating the need for metric quantization altogether.

CFT therefore achieves the conceptual goal long sought by quantum gravity programs: a unified origin for gravitational, quantum, gauge-theoretic, and hydrodynamic laws. Instead of quantizing spacetime, one recognizes geometry itself as an emergent manifestation of temporal alignment in the chronon field.

This perspective not only resolves long-standing conceptual tensions but opens new directions for theory and phenomenology. If geometry is emergent, the true task is to understand the causal substrate from which it arises. CFT provides a concrete proposal for this substrate and a coherent path toward a unified description of the fundamental interactions.

A. Gauge and Hydrodynamic Limits of the TCP Equation

This appendix provides a unified derivation of gauge fields and fluid dynamics as distinct long-wavelength limits of the Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP). No additional assumptions beyond those stated in

Section 3 and

Section 4 are required. Throughout, indices are raised and lowered with the emergent metric

induced by the coherent phase of

.

We take

to be a smooth, unit, future-directed covector,

governed by the TCP Lagrangian

consistent with nonlinear sigma-model and frame-bundle constructions [

29,

40,

65].

A.1. Gauge Structure from Transverse Holonomy

A.1.1. Transverse Bundle and Induced Connection

Define the spatial projector

Choose an orthonormal triad

(

) satisfying

Parallel transport along

induces an

spin connection [

29,

65]:

Its curvature,

is precisely the

gauge field strength [

90,

99].

Abelian subbundle.

Any orthonormal 2–frame

defines an

subbundle, reproducing the tetrad-based construction of electromagnetism [

12,

40]. Parallel transport yields

with abelian curvature

A.1.2. Curvature as Projected Chronon Vorticity

Projection of

into a transverse polarization plane yields [

12]

The nonabelian case is

A.1.3. Yang–Mills Equations from the Antisymmetric TCP Sector

The antisymmetric part of the TCP Euler–Lagrange equation gives

reproducing the Yang–Mills system [

95,

99]

Restriction to a single polarization plane recovers Maxwell theory [

48].

A.1.4. Flux Quantization and the Geometric Action Scale

Holonomy quantization over any closed surface

follows the sigma-model and monopole quantization condition [

75,

85]:

Matching minimal projected vorticity gives

A.2. Hydrodynamic Limit and Navier–Stokes Structure

A.2.1. Coarse-Graining and Effective 4–Velocity

On scales

, fluctuations coarse-grain to the effective fluid 4–velocity

consistent with relativistic hydrodynamic reduction [

41,

56]. Define macroscopic vorticity

Averaging TCP dynamics yields the effective evolution equation

consistent with effective fluid theories [

30,

83].

A.2.2. Nonrelativistic, Slow-Time Reduction

Assume

Then (

31) reduces to the incompressible Navier–Stokes equation [

56]:

A.2.3. Dissipation and the Second Law

The TCP energy functional satisfies a gradient-flow-type descent relation [

19,

69]:

Coarse-graining yields the standard relativistic entropy-production law [

56]:

A.2.4. Relaxation Scales

Competition between quadratic and quartic gradients sets

similar to relaxation in nonlinear sigma-model fluids [

67].

A.3. Summary

and gauge fields arise as holonomies of the transverse polarization bundle of .

Their field strengths are frame-projected components of the chronon vorticity .

The antisymmetric TCP dynamics reproduce Maxwell and Yang–Mills equations to leading order.

Flux quantization yields the geometric action scale .

Coarse-grained TCP dynamics reduce to Navier–Stokes flow with viscosity .

The TCP energy functional obeys a strict energy-descent law, implying irreversible entropy production.

Gauge theory and hydrodynamics thus emerge as complementary limits of the same temporal-alignment dynamics.

References

- Abbott, B.P. et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration) Tests of Lorentz Invariance and Quantum Spacetime with Gravitational Waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 221101. [Google Scholar]

- Arnowitt, R.; Deser, S.; Misner, C.W. Dynamical Structure and Definition of Energy in General Relativity. Phys. Rev. 1959, 116, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, G.S.; Nappi, C.R.; Witten, E. Static properties of nucleons in the Skyrme model. Nucl. Phys. B 1983, 228, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambjørn, J.; Jurkiewicz, J.; Loll, R. Reconstructing the Universe. Phys. Rev. D 2005, 72, 064014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelino-Camelia, G.; et al. Tests of Quantum Gravity from Observations of γ-Ray Bursts. Nature 1998, 393, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelino-Camelia, G. Quantum-spacetime phenomenology. Living Rev. Relativ. 2013, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, N.; Comer, G. Relativistic fluid dynamics: Physics for many different scales. Living Rev. Relativity 2007, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.; Galloway, G. dS/CFT and the Stability of Lorentzian Signature. Ann. Henri Poincaré 2005, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Arnowitt, R.; Deser, S.; Misner, C. The Dynamics of General Relativity. in Gravitation: an Introduction to Current Research, Wiley (1962).

- Ashtekar, A.; Lewandowski, J. Background Independent Quantum Gravity: A Status Report. Class. Quant. Grav. 2004, 21, R53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, H.; et al. Atom Interferometry Tests of Lorentz Invariance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 031101. [Google Scholar]

- Barceló, C.; Liberati, S.; Visser, M. Analogue Gravity. Living Rev. Relativity 2011, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barceló, C.; Liberati, S.; Visser, M. No-go theorem for linear Lorentz violation. Phys. Rev. D 2003, 68, 061302. [Google Scholar]

- Bombelli, L.; Lee, J.; Meyer, D.; Sorkin, R. Space–time as a Causal Set. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987, 59, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohm, D. A suggested interpretation of the quantum theory in terms of hidden variables. Phys. Rev. 1952, 85, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillouin, L. La mécanique ondulatoire de Schrödinger. Comptes Rendus 1926, 183, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, C.P. Quantum Gravity in Everyday Life: General Relativity as an Effective Field Theory. Living Rev. Relativ. 2004, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, J.; Isham, C.J. On the Emergence of Time in Quantum Gravity. in The Arguments of Time, Oxford University Press (1999).

- Campisi, M.; Hänggi, P.; Talkner, P. Quantum fluctuation relations. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2011, 83, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caticha, A. Entropic Dynamics, Time and Quantum Theory. J. Phys. A 2011, 44, 225303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choquet-Bruhat, Y. General Relativity and the Einstein Equations, Oxford Univ. Press (2009).

- DeWitt, B.S. Quantum Theory of Gravity. I. The Canonical Theory. Phys. Rev. 1967, 160, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, J.F. General Relativity as an Effective Field Theory. Phys. Rev. D 1994, 50, 3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, F. Is a Graviton Detectable? Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 2013, 28, 1330041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Mavromatos, N.E.; Nanopoulos, D. Quantum-Gravity Analysis of High-Energy Cosmic-Ray Flight Times. Phys. Lett. B 2003, 564, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, J.; Harries, N.; Meregaglia, A.; Rubbia, A.; Sakharov, A. Probes of Lorentz violation in neutrino propagation. Phys. Rev. D 2008, arXiv:0805.025378, 033013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endlich, S.; Nicolis, A.; Rattazzi, R.; Wang, J. The Effective Theory of Fluids. JHEP 2011, 04, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Feynman, R.P. Application of Quantum Mechanics to Liquid Helium. Prog. Low Temp. Phys. 1955, 1, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, T. The Geometry of Physics, 3rd ed. Cambridge Univ. Press (2011).

- Endlich, S.; Nicolis, A.; Rattazzi, R.; Wang, J. The quantum mechanics of perfect fluids. JHEP 2011, arXiv:1011.639604, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Gell-Mann, M.; Levy, M. The axial vector current in beta decay. Nuovo Cimento 1960, 16, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, G.W.; Hawking, S.W. Action integrals and partition functions in quantum gravity. Phys. Rev. D 1977, 15, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, H. Classical Mechanics, 2nd ed. Addison-Wesley (1980).

- Goroff, M.; Sagnotti, A. Quantum Gravity at Two Loops. Phys. Lett. B 1985, 160, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourgoulhon, E. 3+1 Formalism in General Relativity, Springer (2012).

- Green, M.; Schwarz, J.; Witten, E. Superstring Theory, Vols. 1–2, Cambridge University Press (1987).

- Abbott, B.P.; et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration), GW170817: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Neutron Star Inspiral. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 161101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M.J.W.; Reginatto, M. Schrödinger Equation from Exact Uncertainty Principle. J. Phys. A 2002, 35, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.; Ellis, G.F.R. The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time, Cambridge Univ. Press (1973).

- Hehl, F.W.; Obukhov, Y.N. Foundations of Classical Electrodynamics, Birkhäuser (2003).

- Hiscock, W.A.; Lindblom, L. Stability and causality in dissipative relativistic fluids. Ann. Phys. 1983, 151, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, C.J. Interferometers as Probes of Planckian Quantum Geometry. Phys. Rev. D 2012, 85, 064007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hořava, P. Quantum Gravity at a Lifshitz Point. Phys. Rev. D 2009, 79, 084008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.L. Can Spacetime be a Condensate? Int. J. Theor. Phys. 2005, 44, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.L.; Verdaguer, E. Stochastic Gravity, Cambridge Univ. Press (2008).

- Aartsen, M.G.; et al. (IceCube Collaboration), Neutrino emission from the direction of the blazar TXS 0506+056 prior to the IceCube-170922A alert. Science 2018, 361, 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Isham, C.J. Canonical Quantum Gravity and the Problem of Time. in Integrable Systems, Quantum Groups, and Quantum Field Theories, Kluwer (1993).

- Jackson, J.D. Classical Electrodynamics, 3rd ed. Wiley (1999). [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Nomizu, K. Foundations of Differential Geometry, Vol. 1, Wiley (1963).

- Kostelecký, V.A.; Russell, N. Data Tables for Lorentz and CPT Violation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2011, 83, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Kostelecký, V.A.; Mewes, M. Astrophysical Tests of Lorentz and CPT Violation with Photons. Astrophys. J. 2008, arXiv:0809.2846689, L1–L4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostelecký, V.A.; Mewes, M. Electrodynamics with Lorentz-Violating Operators of Arbitrary Dimension. Phys. Rev. D 2009, 80, 015020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramers, H.A. Wellenmechanik und halbzahlige Quantisierung. Z. Phys. 1926, 39, 828. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchař, K. Time and Interpretations of Quantum Gravity. In Proceedings of the 4th Canadian Conference on General Relativity, World Scientific (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Fluid Mechanics, 2nd ed. Butterworth–Heinemann (1987).

- Liberati, S. Tests of Lorentz invariance: a 2013 update. Class. Quantum Grav. 2013, 30, 133001. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B. Emergent Gravity and Gauge Interactions from a Dynamical Temporal Field. Reports in Advances of Physical Sciences 2025, 9, 2550017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B. Emergence and Exclusivity of Lorentzian Signature and Unit-Norm Time from Random Chronon Dynamics. Reports in Advances of Physical Sciences 2025, 10, 2550022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manton, N.; Sutcliffe, P. Topological Solitons, Cambridge University Press (2004).

- Maslov, V.P.; Fedoriuk, M.V. Semi-Classical Approximation in Quantum Mechanics, Reidel (1981).

- Madelung, E. Quantum theory in hydrodynamic form. Z. Phys. 1926, 40, 322. [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly, D. Modern Tests of Lorentz Invariance. Living Rev. Relativity 2005, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misner, C.W.; Thorne, K.S.; Wheeler, J.A. Gravitation, Freeman (1973).

- Nakahara, M. Geometry, Topology and Physics, Taylor & Francis (2003).

- Nelson, E. Derivation of the Schrödinger Equation from Newtonian Mechanics. Phys. Rev. 1966, 150, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.R. Order, frustration, and defects in liquids and solids. Phys. Rev. B 1983, 28, 5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, H.B.; Olesen, P. Vortex-line models for dual strings. Nucl. Phys. B 1973, 61, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsager, L. Reciprocal Relations in Irreversible Processes. I. Phys. Rev. 1931, 37, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsager, L. Statistical hydrodynamics. Nuovo Cimento 1949, 6, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Thermodynamical Aspects of Gravity: New Insights. Rept. Prog. Phys. 2010, 73, 046901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A. The Spin Foam Approach to Quantum Gravity. Living Rev. Relativity 2013, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petroff, E.; Hessels, J.; Lorimer, D. Fast Radio Bursts. Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 2022, 30, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polchinski, J. String Theory, Vols. 1–2, Cambridge University Press (1998).

- Polyakov, A.M. Particle spectrum in quantum field theory. JETP Lett. 1974, 20, 194. [Google Scholar]

- Polyakov, A.M. Interaction of Goldstone particles in two dimensions. Phys. Lett. B 1975, 59, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Quantum Gravity, Cambridge University Press (2004).

- Rovelli, C.; Vidotto, F. Covariant Loop Quantum Gravity, Cambridge University Press (2014).

- Sakharov, A.D. Vacuum Quantum Fluctuations in Curved Space and the Theory of Gravitation. Sov. Phys. Dokl. 1968, 12, 1040. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, L.; Ma, B.-Q. Lorentz Violation in Photon Propagation. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 2010, 25, 3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skyrme, T.H.R. A nonlinear field theory. Proc. Roy. Soc. A 1961, 260, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Son, D.T.; Surowka, P. Hydrodynamics with Triangle Anomalies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 191601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, D.T. Hydrodynamics of relativistic systems with broken continuous symmetries. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 2001, arXiv:hep-ph/001124616S1C, 1281–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkin, R. Spacetime and Causal Sets. in Relativity and Gravitation: Classical and Quantum, World Scientific (1991).

- ’t Hooft, G. Magnetic monopoles in unified gauge theories. Nucl. Phys. B 1974, 79, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiemann, T. Modern Canonical Quantum General Relativity, Cambridge University Press (2007).

- Tinkham, M. Introduction to Superconductivity, McGraw–Hill (1996).

- Unruh, W. Experimental Black-Hole Evaporation? Phys. Rev. Lett. 1981, 46, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, W.; Wald, R. Time and the Interpretation of Canonical Quantum Gravity. Phys. Rev. D 1989, 40, 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utiyama, R. Invariant theoretical interpretation of interaction. Phys. Rev. 1956, 101, 1597. [Google Scholar]

- Verlinde, E. On the Origin of Gravity and the Laws of Newton. JHEP 2011, 04, 029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volovik, G.E. The Universe in a Helium Droplet, Oxford University Press (2003).

- Wald, R.M. General Relativity, University of Chicago Press (1984).

- Wentzel, G. Eine Verallgemeinerung der Quantenbedingungen. Z. Phys. 1926, 38, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. The Quantum Theory of Fields, Vol. 2, Cambridge Univ. Press (1996).

- Weinberg, S. Effective Field Theory, Past and Future. in Proc. Int. Conf. on High Energy Physics (2009).

- Wheeler, J.A. Geometrodynamics and the Issue of the Final State. in Relativity, Groups and Fields, Gordon and Breach (1964).

- Woodard, R. Avoiding Dark Energy with 1/R Modifications of Gravity. Lect. Notes Phys. 2007, 720, 403. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.N.; Mills, R.L. Conservation of isotopic spin and isotopic gauge invariance. Phys. Rev. 1954, 96, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J.W. Kinematics and Dynamics of General Relativity. in Sources of Gravitational Radiation, ed. L. Smarr, Cambridge Univ. Press (1979).

- Zhang, B. The physical mechanisms of fast radio bursts. Nature 2020, 587, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurek, W.H. Cosmological experiments in superfluid helium? Nature 1985, 317, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).