Submitted:

14 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Global Change Effects on Plankton Community Respiration

3.1. Temperature Sensitivity and Effect of Warming and Marine Heatwaves

3.3. Nutrient Sensitivity and Effect of Eutrophication

3.4. Light and Ultraviolet Sensitivity

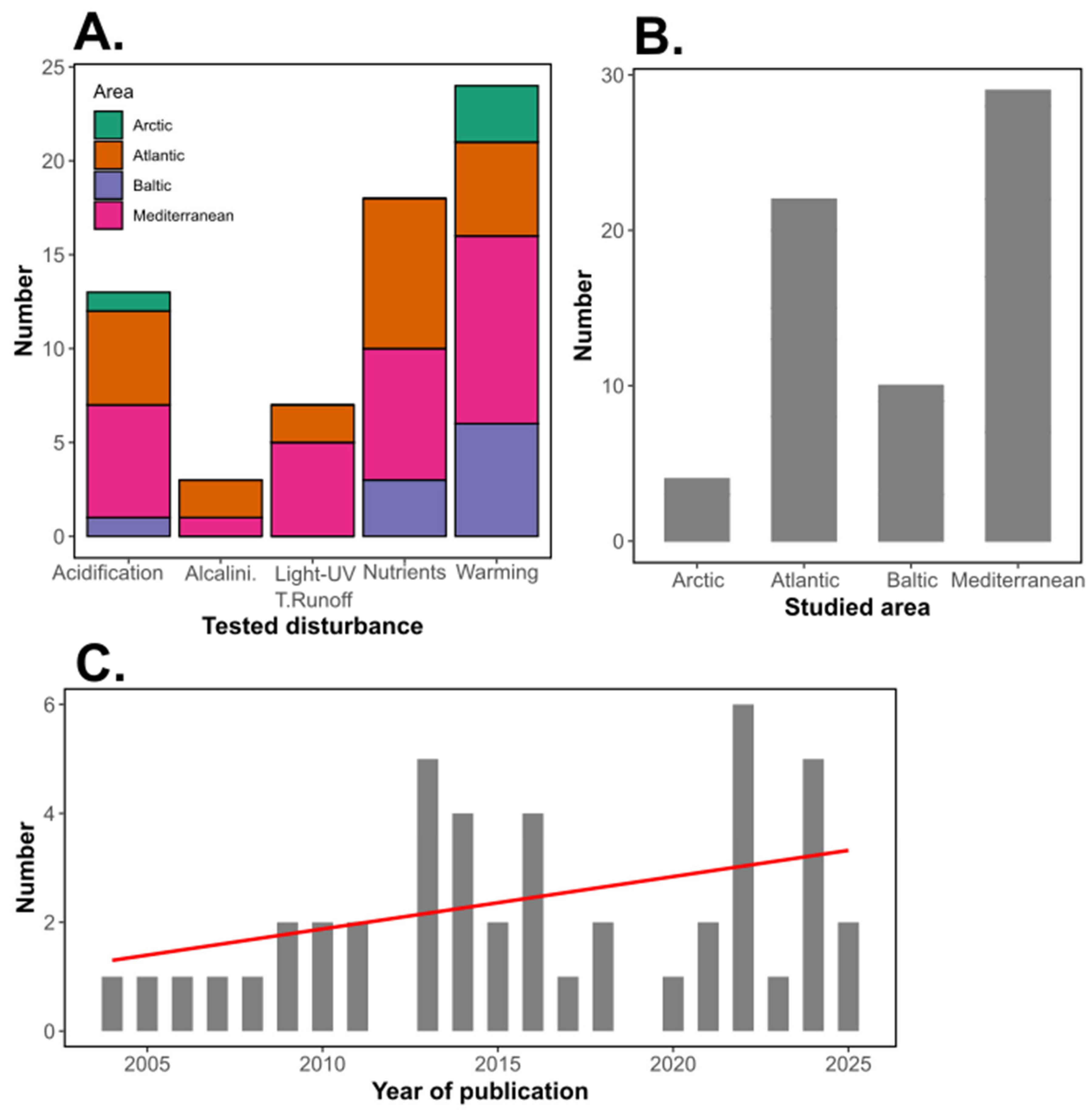

4. Knowledge Gaps in Studied Disturbances and Areas

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

References

- Agustí, S., A. Regaudie-de-Gioux, J. M. Arrieta, and C. M. Duarte. 2014. Consequences of UV-enhanced community respiration for plankton metabolic balance. Limnol. Oceanogr. 59(1):223-232. [CrossRef]

- Agustí, S., J. Martinez-Ayala, A. Regaudie-de-Gioux, and C. M. Duarte. 2017. Oligotrophication and metabolic slowing-down of a NW Mediterranean coastal ecosystem. Front. Mar. Sci. 4:432. [CrossRef]

- Agustí, S., L. Vigoya, and C. M. Duarte. 2018. Annual plankton community metabolism in estuarine and coastal waters in Perth (Western Australia). PeerJ 6:e5081. [CrossRef]

- Aigars, J., N. Suhareva, D. Cepite-Frisfelde, I. Kokorite, A. Iital, M. Skudra, and M. Viska. 2024. From green to brown: two decades of darkening coastal water in the Gulf of Riga, the Baltic Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 11:1369537. [CrossRef]

- Aranguren-Gassis, M., P. Serret, E. Fernández, J. L. Herrera, J. F. Domínguez, V. Pérez, and J. Escanez. 2013. Balanced plankton net community metabolism in the oligotrophic North Atlantic subtropical gyre from Lagrangian observations. Deep Sea Res. I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 68:116-122. [CrossRef]

- Ardyna, M., and K. R. Arrigo. 2020. Phytoplankton dynamics in a changing Arctic Ocean. Nat. Clim. Change 10:892-903. [CrossRef]

- Arístegui, J., and W. G. Harrison. 2002. Decoupling of primary production and community respiration in the ocean: implications for regional carbon studies. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 29:199-209. [CrossRef]

- Baños, I., J. Arístegui, M. Benavides, M. Gómez-Letona, M. F. Montero, J. Ortiz, K. G. Schulz, A. Ludwig, and U. Riebesell. 2022. Response of plankton community respiration under variable simulated upwelling events. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:1006010. [CrossRef]

- Bashiri, B., A. Barzandeh, A. Männik, and U. Raudsepp. 2024. Variability of marine heatwaves’ characteristics and assessment of their potential drivers in the Baltic Sea over the last 42 years. Sci. Rep. 14:22419. [CrossRef]

- Bas-Silvestre, M., M. Antón-Pardo, D. Boix, S. Gascón, J. Compte, J. Bou, B. Obrador, and X. D. Quintana. 2024. Phytoplankton composition in Mediterranean confined coastal lagoons: testing the use of ecosystem metabolism for the quantification of community-related variables. Aquat. Sci. 86:71. [CrossRef]

- Basterretxea, G., J. S. Font-Muñoz, M. Kane, A. Regaudie-de-Gioux, C. T. Satta, and I. Tuval. 2024. Pulsed wind-driven control of phytoplankton biomass at a groundwater-enriched nearshore environment. Sci. Tot. Env. 955:177123. [CrossRef]

- Belzile, C., S. Demers, G. A. Ferreyra, I. Schloss, C. Nozais, K. Lacoste, and others. 2006. UV effects on marine planktonic food webs: A synthesis of results from mesocosm experiments. Photochem. Photobiol. 82:850-856. [CrossRef]

- Beman, J. M., K. R. Arrigo, and P. A. Matson. 2005. Agricultural runoff fuels large phytoplankton blooms in vulnerable areas of the ocean. Nature 434:211-214. [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, J. R., U. Riebesell, A. Larsen, and M. Winder. 2016. Ocean acidification reduces transfer of essential biomolecules in a natural plankton community. Sci. Rep. 6:27749. [CrossRef]

- Breitburg, D., L. A. Levin, A. Oschlies, M. Grégoire, F. P. Chavez, D. J. Conley, and others. 2018. Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters. Science 359:eaam7240. [CrossRef]

- Breithaupt, P. 2009. The impact of climate change on phytoplankton-bacterioplankton interactions. PhD Thesis. Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, 210p.

- Boscolo-Galazzo, F., K. A. Crichton, S. Barker, and P. N. Pearson. 2018. Temperature dependency of metabolic rates in the upper ocean: A positive feedback to global climate change? Global Planet. Change 170:201-212. [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. H., J. F. Gillooly, A. P. Allen, V. M. Savage, and G. B. West. 2004. Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology 85(7):1771-1789. [CrossRef]

- Cabrerizo, M. J., J. M. Medina-Sánchez, J. M. González-Olalla, M. Vila-Argaiz, and P. Carrillo. 2016. Saharan dust inputs and high UVR levels jointly alter the metabolic balance of marine oligotrophic ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 6:35892. [CrossRef]

- Cabrerizo, M. J., E. Marañón, C. Fernández-González, A. Alonso-Núñez, H. Larsson, and M. Aranguren-Gassis. 2021. Temperature fluctuation attenuates the effects of warming in estuarine microbial plankton communities. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:656282. [CrossRef]

- Cabrerizo, M. J., J. M. Medina-Sánchez, J. M. González-Olalla, D. Sánchez-Gómez, and P. Carrillo. 2022. Microbial plankton responses to multiple environmental drivers in marine ecosystems with different phosphorus limitation degrees. Sci. Tot. Env. 816:151491. [CrossRef]

- Caffrey, J. M., J. E. Cloern, and C. Grenz. 1998. Changes in production and respiration during a spring phytoplankton bloom in San Francisco Bay, California, USA: implications for net ecosystem metabolism. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 172:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Caron, D. A., E. L. Lim, R. W. Sanders, M. R. Dennett, and U.-G. Berninger. 2000. Responses of bacterioplankton and phytoplankton to organic carbon and inorganic nutrient additions in contrasting oceanic ecosystems. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 22:175-184. [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, J., R. Klais, and J. E. Cloern. 2015. Phytoplankton blooms in estuarine and coastal waters: Seasonal patterns and key species. Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 162:98-109. [CrossRef]

- Cavan, E. L., and P. W. Boyd. 2018. Effect of anthropogenic warming on microbial respiration and particulate organic carbon export rates in the Sub-Antarctic Southern Ocean. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 82:11-127. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. 2015. Patterns of thermal limits of phytoplankton. J. Plankt. Res. 37(2):285-292. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L., K. von Schuckmann, J. P. Abraham, K. E. Trenberth, M. E. Mann, L. Zanna, and others. 2022. Past and future ocean warming. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3:776-794. [CrossRef]

- Chou, W. R., L. S. Fang, W. H. Wang, and K. S. Tew. 2012. Environmental influence on coastal phytoplankton and zooplankton diversity: a multivariate statistical model analysis. Environ. Monit. Assess. 184:5679-5688. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A. L., K. Weckström, D. J. Conley, N. J. Anderson, F. Adser, E. Andrén, and others. 2006. Long-term trends in eutrophication and nutrients in the coastal zone. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51(1):385-397. [CrossRef]

- Cloern, J. E., S. Q. Foster, and A. E. Kleckner. 2014. Phytoplankton primary production in the world’s estuarine-coastal ecosystems. Biogeosciences 11: 2477-2501. [CrossRef]

- Coggins, A., A. J. Watson, U. Schuster, N. Mackay, B. King, E. McDonagh, and A. J. Poulton. 2023. Surface ocean carbon budget in the 2017 South Georgia diatom bloom: Observations and validation of profiling biogeochemical Argo floats. Deep Sea Res. II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 209:105275. [CrossRef]

- Courboulès, J., F. Vidussi, T. Soulié, E. Nikiforakis, M. Heydon, S. Mas, F. Joux, and B. Mostajir. 2023. Effects of an experimental terrestrial runoff on the components of the plankton food web in a Mediterranean coastal lagoon. Front. Mar. Sci. 10:1200757. [CrossRef]

- Cripps, G., K. J. Flynn, and P. K. Lindeque. 2016. Ocean acidification affects the phyto-zoo plankton trophic transfer efficiency. PLoS ONE 11(4):e0151739. [CrossRef]

- Darmaraki, S., D. Denaxa, I. Theodorou, E. Livanou, D. Rigatou, D. E. Raitsos, and others. 2024. Marine heatwaves in the Mediterranean Sea: A literature review. Medit. Mar. Sci. 25(3):586-620. [CrossRef]

- Das, S., and N. Mangwani. 2015. Ocean acidification and marine microorganisms: responses and consequences. Oceanologia 57(4):349-361. [CrossRef]

- Davis, C. V., E. B. Rivest, T. M. Hill, B. Gaylord, A. D. Russell, and E. Sandford. 2017. Ocean acidification compromises a planktic calcifier with implications for global carbon cycling. Sci. Rep. 7:2225. [CrossRef]

- del Giorgio, P. A., and P. J. le B. Williams. 2005. The global significance of respiration in aquatic ecosystems: from single cells to the biosphere. In: P. A. del Giorgio, P. J. le B. Williams, and B. LE. (Eds) Respiration in aquatic ecosystems. Oxford University Press, 267-303.

- Delille, B., J. Harlay, I. Zondervan, S. Jacquet, L. Chou, R. Wollast, and others. 2005. Response of primary production and calcification to changes of pCO2 during experimental blooms of the coccolithophorid Emiliania huxleyi. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 19(2). [CrossRef]

- Derolez, V., D. Soudant, N. Malet, C. Chiantella, M. Richard, E. Abadie, C. Aliaume, and B. Bec. 2020. Two decades of oligotrophication: Evidence for a phytoplankton community shift in the coastal lagoon of Thau (Mediterranean Sea, France). Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 241:106810. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C. M., S. Agustí, and D. Vaqué. 2004. Controls on planktonic metabolism in the Bay of Blanes, northwestern Mediterranean littoral. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49(6):2162-2170. [CrossRef]

- Egge, J. K., T. F. Thingstad, A. Larsen, A. Engel, J. Wohlers, R. G. J. Bellerby, and U. Riebesell. 2009. Primary production during nutrient-induced blooms at elevated CO2 concentrations. Biogeosciences 6:877-885. [CrossRef]

- Falkowski, P. G. 1994. The role of phytoplankton photosynthesis in global biogeochemical cycles. Photosynth. Res. 39: 235-258. [CrossRef]

- Field, C. B., M. J. Behrenfeld, J. T. Randerson, and P. Falkowski. 1998. Primary production of the biosphere: Integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science 281: 237-240. [CrossRef]

- Filella, A., I. Baños, M. F. Montero, N. Hernández-Hernández, A. Rodríguez-Santos, A. Ludwig, U. Riebesell, and J. Aristegui. 2018. Plankton community respiration and ETS activity under variable CO2 and nutrient fertilization during a mesocosm study in the subtropical North Atlantic. Front. Mar. Sci. 5:310. [CrossRef]

- Forsblom, L., J. Engström-Öst, S. Lehtinen, I. Lips, and A. Lindén. 2019. Environmental variables driving species and genus level changes in annual plankton biomass. J. Plankt. Res. 41(6):925-938. [CrossRef]

- Fredston-Hermann, A., C. J. Brown, S. Albert, C. J. Klein, S. Mangubhai, J. L. Nelson, and others. 2016. Where does river runoff matter for coastal marine conservation? Front. Mar. Sci. 3:273. [CrossRef]

- Frigstad, H., G. S. Andersen, H. C. Trannum, M. McGovern, L.-J. Naustvoll, Ø. Kaste, A. Deininger, and D. Ø. Hjermann. 2023. Three decades of change in the Skagerrak coastal ecosystem, shaped by eutrophication and coastal darkening. Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 283:108193. [CrossRef]

- Frölicher, T. L., E. M. Fischer, and N. Gruber. 2018. Marine heatwaves under global warming. Nature 560:360-364. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Corral, L. S., J. M. Holding, P. Carrillo-de-Albornoz, A. Steckbauer, M. Pérez-Lorenzo, P. Serret, and others. 2017. Temperature dependance of plankton community metabolism in the subtropical and tropical oceans. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 31:1141-1154. [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, E. E., P. Serret, and M. Pérez-Lorenzo. 2011. Testing potential bias in marine plankton respiration rates by dark bottle incubations in the NW Iberian shelf: incubation time and bottle volume. Cont. Shelf Res. 31(5):496-506. [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, E. E., C. J. Daniels, K. Davidson, C. E. Davis, C. Mahaffey, K. M. J. Mayers, and others. 2019a. Seasonal changes in plankton respiration and bacterial metabolism in a temperate shelf sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 177:101884. [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, E. E., C. J. Daniels, K. Davidson, J. Lozano, K. M. J. Mayers, S. McNeill, and others. 2019b. Plankton community respiration and bacterial metabolism in a North Atlantic shelf sea during spring bloom development (April 2015). Prog. Oceanogr. 177:101873. [CrossRef]

- Garnier, A., Ö. Östman, J. Ask, O. Bell, M. Berggren, M. P. D. Rulli, H. Younes, and M. Huss. 2023. Coastal darkening exacerbates eutrophication symptoms through bottom-up and top-down control modification. Limnol. Oceanogr. 68:678-691. [CrossRef]

- Garrabou, J., D. Gómez-Gras, A. Medrano, C. Cerrano, M. Ponti, R. Schlegel, and others. 2022. Marine heatwaves drive recurrent mass mortalities in the Mediterranean Sea. Glob. Change Biol. 28(19):5708-5725. [CrossRef]

- Gazeau, F., F. Van Wambeke, E. Marañón, M. Pérez-Lorenzo, S. Alliouane, C. Stolpe, and others. 2021. Impact of dust addition on the metabolism of Mediterranean plankton communities and carbon export under present and future conditions of pH and temperature. Biogeosciences 18:5423-5446. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Castillo, A. P., A. Panton, and D. A. Purdie. 2023. Temporal variability of phytoplankton biomass and net community production in a macrotidal temperate estuary. Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 280:108182. [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, M., A. Oschlies, D. Canfield, C. Castro, I. Ciglenečki, P. Croot, K. Salin, B. Schneider, P. Serret, C.P. Slomp, T. Tesi, and M. Yücel. 2023. Ocean Oxygen: the role of the Ocean in the oxygen we breathe and the threat of deoxygenation. In: Rodriguez Perez, A., Kellett, P., Alexander, B., Muñiz Piniella, Á., Van Elslander, J., Heymans, J. J., [Eds.] Future Science Brief No. 10 of the European Marine Board, Ostend, Belgium. ISSN: 2593-5232. ISBN: 9789464206180. [CrossRef]

- Guinotte, J. M., and V. J. Fabry. 2008. Ocean acidification and its potential effects on marine ecosystems. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1134:320-342. [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. A. M., and A. M. Lewandowska. 2022. Zooplankton dominance shift in response to climate-driven salinity change: A mesocosm study. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:861297. [CrossRef]

- Harley, C. D. G., A. R. Hughes, K. M. Hultgren, B. G. Milner, C. J. B. Sorte, C. S. Thornber, and others. 2006. The impacts of climate change in coastal marine systems. Ecol. Lett. 9(2):228-241. [CrossRef]

- Hays, G. C., A. J. Richardson, and C. Robinson. 2005. Climate change and marine plankton. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20(6): 337-344. [CrossRef]

- Henson, S., C. A. Baker, P. Halloran, A. McQuatters-Gollop, S. Painter, A. Planchat, and A. Tagliablue. 2024. Knowledge gaps in quantifying the climate change response of biological storage of carbon in the ocean. Earth’s future 12:e2023EF004375.

- Holding, J. M., C. M. Duarte, J. M. Arrieta, R. Vaquer-Sunyer, A. Coello-Camba, P. Wassmann, and S. Agustí. 2013. Experimentally determined temperature thresholds for Arctic plankton community metabolism. Biogeosciences 10:357-370. [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, H.-G., P. Breithaupt, K. Walther, R. Koppe, S. Bleck, U. Sommer, and K. Jürgens. 2008. Climate warming in winter affects the coupling between phytoplankton and bacteria during the spring bloom: a mesocosm study. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 51:105-115. [CrossRef]

- Huete-Stauffer, T. M., N. Arandia-Gorostidi, N. González-Benítez, L. Díaz-Pérez, A. Calvo-Díaz, and X. A. G. Morán. 2018. Large plankton enhance heterotrophy under experimental warming in a temperate coastal ecosystem. Ecosystems 21:1139-1154. [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, D. A., and D. G. Capone. 2022. The marine nitrogen cycle: new developments and global change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20:401-414. [CrossRef]

- IPCC, 2019. IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 755 pp. [CrossRef]

- James, A. K., U. Passow, M. A. Brzezinski, R. J. Parsons, J. N. Trapani, and C. A. Carlson. 2017. Elevated pCO2 enhances bacterioplankton removal of organic carbon. PLoS ONE 12:e0173145. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L. M., K. Sand-Jensen, S. Marcher, and M. Hansen. 1990. Plankton community respiration along a nutrient gradient in a shallow Danish estuary. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 61:75-85. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, N., and F. Azam. 2011. Microbial carbon pump and its significance for carbon sequestration in the ocean. In: Jiao N., Azam F., Sanders S. (Eds.) Microbial carbon pump in the Ocean 10:43-45, Science/AAAS, Washington DC.

- Jones, K., A. Liess, and J. Sjöstedt. 2024. Microbial carbon utilization in a boreal lake under the combined pressures of brownification and eutrophication: insights from a field experiment. Hydrobiologia. [CrossRef]

- Ktistaki, G., I. Magiopoulos, G. Corno, J. Courboulès, E. M. Eckert, J. González, and others. 2024. Brownification in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea: effect of simulated terrestrial input on the planktonic microbial food web in an oligotrophic sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 11:1343415. [CrossRef]

- Lagaria, A., S. Psarra, D. Lefèvre, F. Van Wambeke, C. Courties, M. Pujo-Pay, L. Oriol, T. Tanaka, and U. Christaki. 2011. The effects of nutrient additions on particulate and dissolved primary production and metabolic state in surface waters of three Mediterranean eddies. Biogeosciences 8:2595-2607. [CrossRef]

- Latorre, M. P., C. M. Iachetti, I. R. Schloss, J. Antoni, A. Malits, F. de la Rosa, and others. 2023. Summer heatwaves affect coastal Antarctic plankton metabolism and community structure. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 567:151926. [CrossRef]

- Laufkötter, C., M. Vogt, N. Gruber, M. Aita-Noguchi, O. Aumont, L. Bopp, and others. 2015.. Drivers and uncertainties of future global marine primary production in marine ecosystem models. Biogeosciences 12:6955-6984. [CrossRef]

- Lefèvre, D., T. L. Bentley, C. Robinson, S. P. Blight, and P. J. le B. Williams. 1994. The temperature response of gross and net community production and respiration in time-varying assemblages of temperate marine micro-plankton. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 184(2):201-215. [CrossRef]

- Legendre, L., and F. Rassoulzadegan. 1995. Plankton and nutrient dynamics in marine waters. Ophelia 41(1):153-172. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, A., K. Myrberg, P. Post, I. Chubarenko, I. Dailidiene, H.-H. Hinrichsen, and others. 2022. Salinity dynamics of the Baltic Sea. Earth Syst. Dynam. 13:373-392. [CrossRef]

- Lekunberri, I., T. Lefort, E. Romero, E. Vázquez-Domínguez, C. Romera-Castillo, C. Marrasé, F. Peters, M. Weinbauer, and J. M. Gasol. 2010. Effects of a dust deposition event on coastal marine microbial abundance and activity, bacterial community structure and ecosystem function. J. Plankt. Res. 32(4):381-396. [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A. M., D. G. Boyce, M. Hofmann, B. Matthiessen, U. Sommer, and B. Worm. 2014. Effects of sea surface warming on marine plankton. Ecol. Lett. 17(5):614-623. [CrossRef]

- Li, G., L. Cheng, J. Zhu, K. E; Trenberth, M. E. Mann, and J. P. Abraham. 2020. Increasing ocean stratification over the past half-century. Nat. Clim. Change 10:1116-1123. [CrossRef]

- Liess, A., O. Rowe, S. N. Francoeur, J. Guo, K. Lange, A. Schröder, and others. 2016. Terrestrial runoff boosts phytoplankton in a Mediterranean coastal lagoon, but these effects do not propagate to higher trophic levels. Hydrobiologia 766:275-291. [CrossRef]

- Litchman, E., K. F. Edwards, C. A. Klausmeier, and M. K. Thomas. 2012. Phytoplankton niches, traits and eco-evolutionary responses to global environmental change. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 470: 235-248. [CrossRef]

- Lizon, F. Y. Lagadeuc, C. Brunet, D. Aelbrecht, and D. Bentley. 1995. Primary production and photoadaptation of phytoplankton in relation with tidal mixing in coastal waters. J. Plankt. Res. 17(5):1039-1055. [CrossRef]

- López-Sandoval, D. C., C. Fernández-González, C. González-García, and E. Marañón. 2025. Warming accelerates phytoplankton bloom dynamics and differentially affects the fluxes of carbon, nitrogen and oxygen through a coastal microbial community. Microb. Ecol. 88:117. [CrossRef]

- López-Urrutia, A., E. San Martin, R. P. Harris, and X. Irigoien. 2006. Scaling the metabolic balance of the oceans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103: 8739-8744. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, J., M. Aranguren-Gassis, E. E. García-Martín, J. González, J. L. Herrera, B. Hidalgo-Robatto, D. Mártinez-Castrillón, M. Pérez-Lorenzo, R. A. Varela, and P. Serret. 2021. Seasonality of phytoplankton cell size and the relation between photosynthesis and respiration in the Ría de Vigo (NW Spain). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 664:43-58. [CrossRef]

- Mantikci, M., M. Bentzon-Tilia, S. J. Traving, H. Knudsen-Leerbeck, L. Riemann, and others. 2024. Plankton community metabolism variations in two temperate coastal waters of contrasting nutrient richness. JGR Biogeosci. 129(6):e2023JG007919. [CrossRef]

- Marañón, E., M. P. Lorenzo, P. Cermeño, and B. Mouriño-Carballido. 2018. Nutrient limitation suppresses the temperature dependence of phytoplankton metabolic rates. ISME J. 12(7):1836-1845. [CrossRef]

- Marín-Samper, L., J. Arístegui, N. Hernández-Hernández, J. Ortiz, S. D. Archer, A. Ludwig, and U. Riebesell. 2024. Assessing the impact of CO2-equilibrated ocean alkalinity enhancement on microbial metabolic rates in an oligotrophic system. Biogeosciences 21:2859-2876. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, S., E. Fernández, A. Calvo-Díaz, P. Cermeño, E. Marañón, X. A. G. Morán, and E. Teira. 2013. Differential response of microbial plankton to nutrient inputs in oligotrophic versus mesotrophic waters of the North Atlantic. Mar. Biol. Res. 9(4):358-370. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, S., B. Arbones, E. E. García-Martín, I. G. Teixeira, P. Serret, E. Fernández, F. G. Figueiras, E. Teira, and X. A. Álvarez-Salgado. 2014. Impact of atmospheric deposition on the metabolism of coastal microbial communities. Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 153:18-28. [CrossRef]

- Matear, R. J., and A. Lenton. Quantifying the impact of ocean acidification on our future climate. Biogeosciences 11(14):3965-3983. [CrossRef]

- Maugendre, L., J.-P. Gattuso, J. Louis, A. de Kluijver, S. Marro, K. Soetaert, and F. Gazeau. 2015. Effect of ocean warming and acidification on a plankton community in the NW Mediterranean Sea. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 72(6):1744-1755. [CrossRef]

- Maugendre, L., J.-P. Gattuso, A. J. Poulton, W. Dellisanti, M. Gaubert, C. Guieu, and F. Gazeau. 2017. No detectable effect of ocean acidification on plankton metabolism in the NW oligotrophic Mediterranean Sea: Results from two mesocosm studies. Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 186(A):89-99. [CrossRef]

- Mena, C., P. Reglero, M. Hidalgo, E. Sintes, R. Santiago, M. Martín, G. Moyà, and R. Balbín. 2019. Phytoplankton community structure is driven by stratification in the oligotrophic Mediterranean Sea. Front. Microbiol. 10:1698. [CrossRef]

- Mercado, J. M., C. Sobrino, P. J. Neale, M. Segovia, A. Reul, A. L. Amorim, and others. 2014. Effect of CO2, nutrients and light on coastal plankton. II. Metabolic rates. Aquat. Biol. 22:43-57. [CrossRef]

- Mesa, E., A. Delgado-Huertas, P. Carillo-de-Albornoz, L. S. García-Corral, M. Sanz-Martín, P. Wassmann, and others. 2017. Continuous daylight in the high-Arctic summer supports high plankton respiration rates compared to those supported in the dark. Sci. Rep. 7:1247. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, H. D., M. Köring, J. Di Pane, N. Tremblay, K. H. Wiltshire, M. Boersma, and C. L. Meunier. 2022. An integrated multiple driver mesocosm experiment reveals the effect of global change on planktonic food web structure. Commun. Biol. 5:179. [CrossRef]

- Motegi, C., T. Tanaka, J. Piontek, C. P. D. Brussaard, J.-P. Gattuso, and M. G. Weinbauer. 2013. Effect of CO2 enrichment on bacterial metabolism in an Arctic fjord. Biogeosciences 10:3285-3296. [CrossRef]

- Mozetič, P., C. Solidoro, G. Cossarini, G. Socal, R. Precali, J. Francé, and others. 2010. Recent trends towards oligotrophication of the Northern Adriatic: Evidence from chlorophyll a time series. Est. Coasts 33:362-375. [CrossRef]

- Murray, C. J., B. Müller-Karulis, J. Carstensen, D. J. Conley, B. G. Gustafsson, and J. H. Andersen. 2019. Past, present and future eutrophication status of the Baltic Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:2. [CrossRef]

- Murrell, M. C., R. S. Stanley, J. C; Lehrter, and J. D. Hagy III. 2013. Plankton community respiration, net ecosystem metabolism, and oxygen dynamics on the Louisiana continental shelf: Implications for hypoxia. Cont. Shelf. Res. 52:27-38. [CrossRef]

- Olesen, M., C. Lundsgaard, and A. Andrushaitis. 1999. Influence of nutrients and mixing on the primary production and community respiration in the Gulf of Riga. J. Mar. Sys. 23:127-143. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, Y., S. Agustí, T. Andersen, C. M. Duarte, J. M. Gasol, I. Gismervik, and others. 2006. A comparative study of responses in planktonic food web structure and function in contrasting European coastal waters exposed to nutrient addition. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51(1):488-503. [CrossRef]

- Opdal, A. F., T. Andersen, D. O. Hessen, C. Lindemann, and D. L. Aksnes. 2023. Tracking freshwater browning and coastal water darkening from boreal forests to the Arctic Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 8(4):611-619. [CrossRef]

- Opdal, A. F., C. Lindemann, T. Andersen, D. O. Hessen, Ø. Fiksen, D. L. Aksnes. 2024. Land use change and coastal water darkening drive synchronous dynamics in phytoplankton and fish phenology on centennial timescales. Glob. Change Biol. 30(5):e17308. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, J., J. Arístegui, J. Taucher, and U. Riebesell. 2022. Artificial upwelling in singular and recurring mode: Consequences for net community production and metabolic balance. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:743105. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, J., J. Arístegui, S. U. Goldenberg, M. Fernández-Méndez, J. Taucher, S. D. Archer, M. Baumann, and U. Riebesell. 2024. Phytoplankton physiology and functional traits under artificial upwelling with varying Si:N. Front. Mar. Sci. 10:1319875. [CrossRef]

- Oschlies, A., P. Brandt, L. Stramma, and S. Schmidtko. 2018. Drivers and mechanisms of ocean deoxygenation. Nat. Geosci. 11:467-473. [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, S., A. Nydahl, P. Anton, and J. Wikner. 2013. Strong seasonal effect of moderate experimental warming on plankton respiration in a temperate estuarine plankton community. Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 135:269-279. [CrossRef]

- Pastor, F., and S. Khodayar. 2023. Marine heat waves: Characterizing a major climate impact in the Mediterranean. Sci. Tot. Env. 861:160621. [CrossRef]

- Pilkaitytë, R., A. Schoor, and H. Schubert. 2004. Response of phytoplankton communities to salinity changes – a mesocosm approach. Hydrobiologia 513:27-38. [CrossRef]

- Prichett, D., J. M. Bonilla Pagan, C. L. S. Hodgkins, and J. M. Testa. 2024. Controls on water-column respiration rates in a coastal plan estuary: Insights from long-term time-series measurements. Est. Coasts 47:2542-2551. [CrossRef]

- Pringault, O., S. Tesson, and E. Rochelle-Newall. 2009. Respiration in the light and bacterio-phytoplankton coupling in a coastal environment. Microb. Ecol. 57:321-334. [CrossRef]

- Pulina, S., S. Suikkanen, B. M. Padedda, A. Brutemark, L. M. Grubisic, C. T. Satta, T. Caddeo, P. Farina, and A. Lugliè. 2020. Responses of a Mediterranean coastal lagoon plankton community to experimental warming. Mar. Biol. 167:22. [CrossRef]

- Qu, L., D. A. Campbell, and K. Gao. 2021. Ocean acidification interacts with growth light to suppress CO2 acquisition efficiency and enhance mitochondrial respiration in a coastal diatom. Mar. Poll. Bull. 163:112008. [CrossRef]

- Rabalais, N. N., R. E. Turner, R. J. Díaz, and D. Justić. 2009. Global change and eutrophication of coastal waters. 2009. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 66(7):1528-1537. [CrossRef]

- Regaudie-de-Gioux, A., and C. M. Duarte. 2012. Temperature dependance of planktonic metabolism in the ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 26(1). [CrossRef]

- Regaudie-de-Gioux, A., and C. M. Duarte. 2013. Global patterns in oceanic planktonic metabolism. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58(3):977-986. [CrossRef]

- Regaudie-de-Gioux, A., S. Agustí, and C. M. Duarte. 2014. UV sensitivity of planktonic net community production in ocean surface waters. JGR Biogeosciences 119(5):929-936. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C., and P. J. Le B. Williams. 2005. Respiration and its measurement in surface marine waters. In: P. A. del Giorgio, P. J. le B. Williams, and B. LE. (Eds) Respiration in aquatic ecosystems. Oxford University Press, 147-180.

- Robinson, C. 2019. Microbial respiration: the engine of ocean deoxygenation. Front. Mar. Sci. 5:533. [CrossRef]

- Serret, P., C. Robinson, M. Aranguren-Gassis, and others. 2015. Both respiration and photosynthesis determine the scaling of plankton metabolism in the oligotrophic ocean. Nat. Commun. 6: 6961. [CrossRef]

- Serret, P., D. Basso, P. Pitta, I. Magiopoulos, P. Alcaraz, A. Penin, and others. 2024. The impact of ocean liming on phytoplankton size-structure and the balance of photosynthesis and respiration in two contrasting environments. EGU General Assembly 2024, Vienna, Austria. EGU24-13093. [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. E., M. T. Burrows, A. J. Hobday, N. G. King, P. J. Moore, A. Sen Gupta, and others. 2023. Biological impacts of marine heatwaves. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 15:119-145. [CrossRef]

- Solås, M. R., A. G. V. Salvanes, and D. L. Aksnes. 2024. Association between water darkening and hypoxia in a Norwegian fjord. Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 310:108988. [CrossRef]

- Soulié, T., S. Mas, D. Parin, F. Vidussi, and B. Mostajir. 2021. A new method to estimate planktonic oxygen metabolism using high-frequency sensor measurements in mesocosm experiments and considering daytime and nighttime respirations. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 19(5):303-316. [CrossRef]

- Soulié, T., F. Vidussi, J. Courboulès, S. Mas, and B. Mostajir. 2022a. Metabolic responses of plankton to warming during different productive seasons in coastal Mediterranean waters revealed by in situ mesocosm experiments. Sci. Rep. 12:9001. [CrossRef]

- Soulié, T., F. Vidussi, S. Mas, and B. Mostajir. 2022b. Functional stability of a coastal Mediterranean plankton community during an experimental marine heatwave. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:831496. [CrossRef]

- Soulié, T., H. Stibor, S. Mas, B. Braun, J. Knechtel, J. C. Nejstgaard, and others. 2022c. Brownification reduces oxygen gross primary production and community respiration and changes the phytoplankton community composition: An in situ mesocosm experiment with high-frequency sensor measurements in a North Atlantic bay. Limnol. Oceanogr. 67(4):874-887. [CrossRef]

- Soulié, T., J. Engström-Öst, and O. Glippa. 2022d. Copepod oxygen consumption along a salinity gradient. Mar. Fresh. Behav. Physiol. 55(5-6):107-119. [CrossRef]

- Soulié, T., F. Vidussi, S. Mas, and B. Mostajir. 2023. Functional and structural responses of plankton communities toward consecutive experimental heatwaves in Mediterranean coastal waters. Sci. Rep. 13:8050. [CrossRef]

- Soulié, T., F. Vidussi, J. Courboulès, M. Heydon, S. Mas, F. Voron, C. Cantoni, F. Joux, and B. Mostajir. 2024. Simulated terrestrial runoff shifts the metabolic balance of a coastal Mediterranean plankton community towards heterotrophy. Biogeosciences 21:1887-1902. [CrossRef]

- Soulié, T., J. Gonzalez, P. Serret, I. G. Teixeira, C. G. Castro, S. Mas, D. Parin, F. Vidussi, and B. Mostajir. 2025. Warming enhances primary production and respiration and changes plankton community structure in an estuarine upwelling system. Limnol. Oceanogr. [CrossRef]

- Spatharis, S., G. Tsirtsis, D. B. Danielidis, T. Do Chi, and D. Mouillot. 2007. Effects of pulsed nutrient inputs on phytoplankton assemblage structure and blooms in an enclosed coastal area. Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 73(3-4):807-815. [CrossRef]

- Spilling, K., A. J. Paul, N. Virkkala, T. Hastings, S. Lischka, A. Stuhr, and others. 2016. Ocean acidification decreases plankton respiration: evidence from a mesocosm experiment. Biogeosciences 13:4707-4719. [CrossRef]

- Staehr, P. A., and K. Sand-Jensen. 2006. Seasonal changes in temperature and nutrient control of photosynthesis, respiration and growth of natural phytoplankton communities. Fresh. Biol. 51:249-262. [CrossRef]

- Staehr, P. A., D. Bade, M. C. Van de Bogert, G. R. Koch, C. Williamson, P. Hanson, J. J. Cole, and T. Kratz. 2010. Lake metabolism and the diel oxygen technique: State of the science. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 8(11):628-644. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R. I. A., M. Dossena, D. A. Bohan, E. Jeppesen, R. L. Kordas, M. E. Ledger, and others. 2013. Chapter Two -Mesocosm experiments as a tool for ecological climate-change research. Adv. Ecol. Res. 48:71-181. [CrossRef]

- Striebel, M., L. Kallajoki, C. Kunze, J. Wollschläger, A. Deininger, and H. Hillebrand. 2023. Marine primary producers in a darker future: a meta-analysis of light effects on pelagic and benthic autotrophs. Oikos 2023:e09501. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T., S. Alliouane, R. G. B. Bellerby, J. Czerny, A. de Kluijver, U. Riebesell, K. G. Schulz, A. Silyakova, and J.-P. Gattuso. 2013. Effect of increased pCO2 on the planktonic metabolic balance during a mesocosm experiment in an Arctic fjord. Biogeosciences 10:315-325. [CrossRef]

- Turley, C., and H. S. Findlay. 2016. Chapter 18 – Ocean acidification. In: T. M. Letcher (Ed) Climate Change (Second Edition). Elsvier, 271-293. [CrossRef]

- van Pelt, W., V. Pohjola, R. Pettersson, S. Marchenko, J. Kohler, B. Luks, and others. 2019. A long-term dataset of climatic mass balance, snow conditions, and runoff in Svalbard (1957-2018). The Cryosphere 13:2259-2280. [CrossRef]

- Vanharanta, M., M. Santoro, C. Villena-Alemany, J. Piiparinen, K. Piwosz, H.-P. Grossart, M. Labrenz, and K. Spilling. 2024. Microbial remineralization processes during postspring-bloom with excess phosphate available in the northern Baltic Sea. FEMS Microb. Ecol. 100:fiae103. [CrossRef]

- Vaquer-Sunyer, R., C. M. Duarte, R. Santiago, P. Wassmann, and M. Reigstad. 2010. Experimental evaluation of planktonic respiration response to warming in the European Arctic sector. Polar Biol. 33:1661-1671. [CrossRef]

- Vaquer-Sunyer, R., and C. M. Duarte. 2013. Experimental evaluation of the response of coastal Mediterranean planktonic and benthic metabolism to warming. Est. Coasts 36:697-707. [CrossRef]

- Vaquer-Sunyer, R., C. M. Duarte, A. regaudie-de-Gioux, J. Holding, L. S. Garcia-Corral, M. Reigstad, and P. Wassmann. 2013. Seasonal patterns in Arctic planktonic metabolism (Fram Strait - Svalbard region). Biogeosciences 10:1451-1469. [CrossRef]

- Vaquer-Sunyer, R., D. J. Conley, S. Muthusamy, M. V. Lindh, J. Pinhassi, and E. S. Kritzberg. 2015. Dissolved organic nitrogen inputs from wastewater treatment plant effluents increase responses of planktonic metabolic rates to warming. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49:11411-11420. [CrossRef]

- Vaquer-Sunyer, R., H. E. Reader, S. Muthusamy, M. V. Lindh, J. Pinhassi, D. J. Conley, and E. S. Kritzberg. 2016. Effects of wastewater treatment plant effluent inputs on planktonic metabolic rates and microbial community composition in the Baltic Sea. Biogeosciences 13:4751-4765. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Domínguez, E., D. Vaqué, and J. M. Gasol. 2007. Ocean warming enhances respiration and carbon demand of coastal microbial plankton. Glob. Change Biol. 13(7):1327-1334. [CrossRef]

- Vidussi, F., B. Mostajir, E. Fouilland, E. Le Floc’h, J. Nouguier, C. Roques, P. Got, D. Thibault-Botha, T. Bouvier, and M. Troussellier. 2011. Effects of experimental warming and increased ultraviolet B radiation on the Mediterranean plankton food web. Limnol. Oceanogr. 56(1):206-218. [CrossRef]

- Weber, T. S., and C. Deutsch. 2010. Ocean nutrient ratios governed by plankton biogeography. Nature 467:550-554. [CrossRef]

- Wernberg, T., D. A. Smale, and M. S. Thomsen. 2012. A decade of climate change experiments on marine organisms: procedures, patterns and problems. Glob. Change Biol. 18(5):1491-1498. [CrossRef]

- Wikner, J., K. Vikström, and A. Verma. 2023. Regulation of marine plankton respiration: A test of models. Front. Mar. Sci. 10:1134699. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J. M., S. S. Abboud, and J. M. Beman. 2024. Effects of experimental nutrient enrichment and eutrophication on microbial community structure and function in “marine lakes”. Elem. Sci. Anth. 12:1. [CrossRef]

- Wohlers, J., A. Engel, A. Zöllner, P. Breithaupt, K. Jürgens, H.-G. Hoppe, and others. 2009. Changes in biogenic carbon flow in response to sea surface warming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106:7067-7072. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, K. K. E., C. J. M. Hoppe, L. Rehder, E. Schaum, U. John, and B. Rost. 2024. Heatwave responses of Arctic phytoplankton communities are driven by combined impacts of warming and cooling. Sci. Adv. 10:eadl5904. [CrossRef]

- Yvon-Durocher, G., J. M. Caffrey, A. Cescatti, M. Dossena, P. del Giorgio, J. M. Gasol, and others. 2012. Reconciling the temperature dependence of respiration across timescales and ecosystem types. Nature 487:472-476. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.-Y., J. Hu, G.-D. Song, Y. Wu, J. Zhang, and S.-M. Liu. 2016. Phytoplankton-driven dark plankton respiration in the hypoxic zone off the Changjiang Estuary, revealed by in vitro incubations. J. Mar. Sys. 154(A):50-56. [CrossRef]

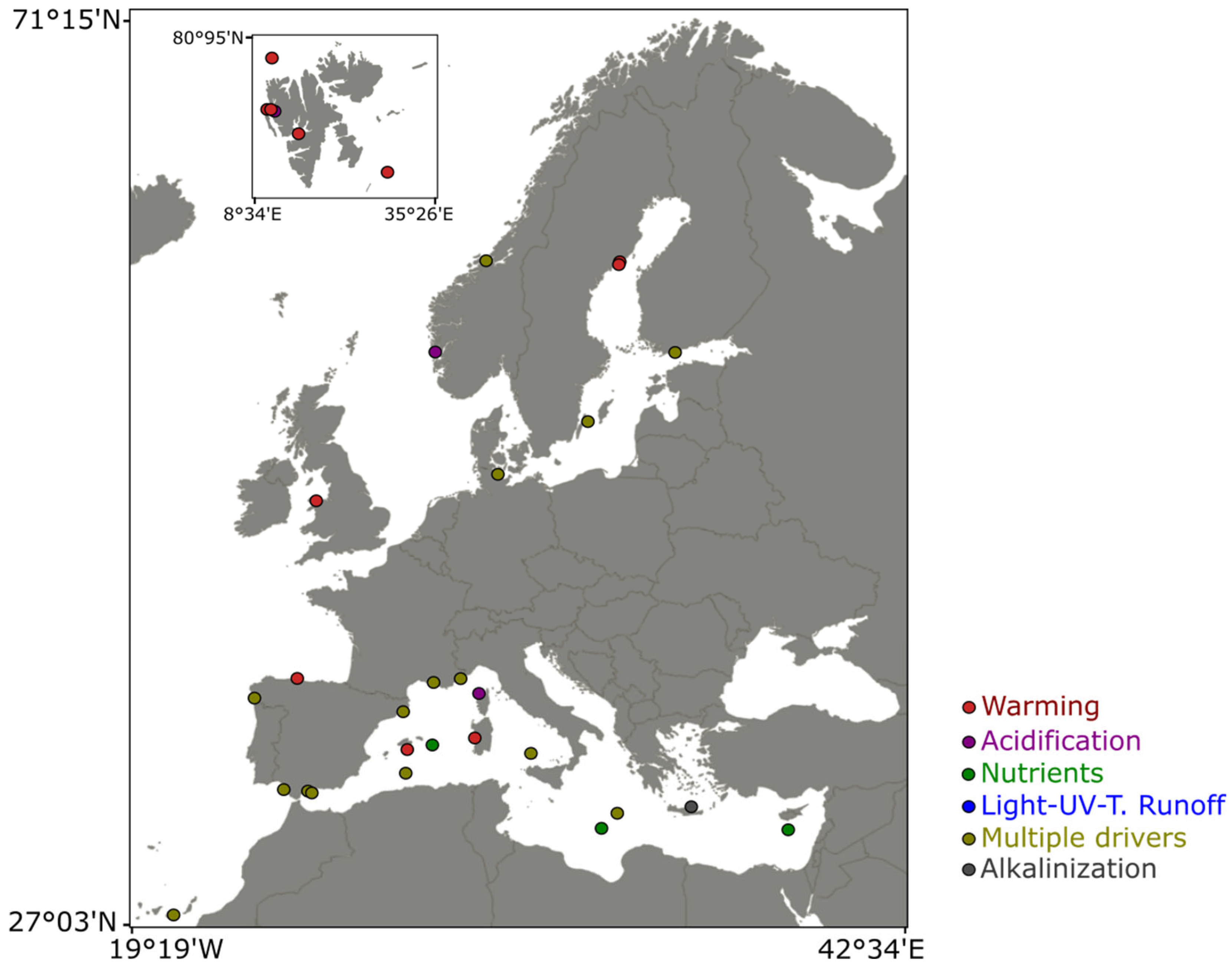

| Study | Disturbance | Study site | Area | |

| 1 | Vaquer-Sunyer et al., (2010) | Warming | Svalbard | Arctic |

| 2 | Holding et al., (2013) | Warming | Svalbard | Arctic |

| 3 | Wolf et al., (2024) | Warming | Svalbard | Arctic |

| 4 | Hoppe et al., (2008) | Warming | Kiel fjord | Baltic |

| 5 | Cabrerizo et al., (2021) | Warming | Gulf of Bothnia | Baltic |

| 6 | Panigrahi et al., (2013) | Warming | Bothnian Sea | Baltic |

| 7 | Lewandowska et al., (2014) | Warming | Baltic Sea | Baltic |

| 8 | Wohlers et al., (2009) | Warming | Western Baltic Sea | Baltic |

| 9 | Soulié et al., (2022a) | Warming | Thau Lagoon | Mediterranean |

| 10 | Vázquez-Domínguez et al., (2007) | Warming | Bay of Blanes | Mediterranean |

| 11 | Vaquer-Sunyer & Duarte (2013) | Warming | Majorca | Mediterranean |

| 12 | Soulié et al., (2022b) | Warming | Thau Lagoon | Mediterranean |

| 13 | Soulié et al., (2023) | Warming | Thau Lagoon | Mediterranean |

| 14 | Pulina et al., (2020) | Warming | Cabras lagoon | Mediterranean |

| 15 | Maugendre et al., (2015) | Warming; Acidification | Bay of Villefranche | Mediterranean |

| 16 | Huete-Stauffer et al., (2018) | Warming | Bay of Biscay | Atlantic |

| 17 | Soulié et al., (2025) | Warming | Ría de Vigo | Atlantic |

| 18 | López-Sandoval et al., (2025) | Warming; Nutrients | Ría de Vigo | Atlantic |

| 19 | Vaquer-Sunyer et al, (2015) | Warming; Nutrients | Baltic Proper | Baltic |

| 20 | Tanaka et al., (2013) | Acidification | Svalbard | Arctic |

| 21 | Spilling et al., (2016) | Acidification | Storfjärden, Finland | Baltic |

| 22 | Maugendre et al., (2017) | Acidification | Bay of Villefranche; Bay of Calvi | Mediterranean |

| 23 | Delille et al., (2005) | Acidification | Raunefjporden, Norway | Atlantic |

| 24 | Egge et al., (2009) | Acidification | Raunefjporden, Norway | Atlantic |

| 25 | Filella et al., (2018) | Acidification; Nutrients | Taliarte, Gran Canaria | Atlantic |

| 26 | Martínez-García et al., (2013) | Nutrients | Ría de Vigo | Atlantic |

| 27 | Vaquer-Sunyer et al., (2016) | Nutrients | Baltic Sea | Baltic |

| 28 | Olsen et al., (2006) | Nutrients | Tvarminne, Blanes Bay, Hopavågen Bay | Baltic, Mediterranean, Atlantic |

| 29 | Lagaria et al., (2011) | Nutrients | Mediterranean | Mediterranean |

| 30 | Duarte et al., (2004) | Nutrients | Bay of Blanes | Mediterranean |

| 31 | Cabrerizo et al., (2022) | Warming; Nutrients | Coastal waters of the Mediterranean and the Atlantic | Mediterranean, Atlantic |

| 32 | Martínez-García et al., (2014) | Nutrients | Ría de Vigo | Atlantic |

| 33 | Baños et al., (2022) | Nutrients | Gando Bay, Canary | Atlantic |

| 34 | Ortiz et al., (2022) | Nutrients | Gando Bay, Canary | Atlantic |

| 35 | Cabrerizo et al., (2016) | UV; Nutrients | SW Mediterreanean Sea | Mediterranean |

| 36 | Lekunberri et al., (2010) | Nutrients | Bay of Blanes | Mediterranean |

| 37 | Ortiz et al., (2024) | Nutrients | Gando Bay, Canary | Atlantic |

| 38 | Soulié et al., (2024) | Terrestrial runoff | Thau Lagoon | Mediterranean |

| 39 | Liess et al., (2016) | Terrestrial runoff | Thau Lagoon | Mediterranean |

| 40 | Soulié et al., (2022c) | Terrestrial runoff | Hopavågen Bay | Atlantic |

| 41 | Agustí et al., (2014) | Light, UV | Majorca | Mediterranean |

| 42 | Marín-Samper et al., (2024) | Alkalinity | Taliarte, Gran Canria | Atlantic |

| 43 | Serret et al., (2024) | Alkalinity | Ría de Vigo, Cretan Sea | Atlantic; Mediterranean |

| 44 | Mercado et al., (2014) | Acidification; Nutrients; Light | Fuengirola, southern Spain | Mediterranean |

| 45 | Gazeau et al., (2021) | Warming, Acidification, Nutrients | Mediterranean | Mediterranean |

| 46 | Vidussi et al., (2011) | Warming; UV | Thau Lagoon | Mediterranean |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).