1. Introduction

Mutations in homologous recombination repair (HRR) genes affect a substantial portion of prostate cancer (PC) cases. The frequency of HRR alterations reaches 20-25% in metastatic castration resistant PC (mCRPC), which is the most aggressive variant of this disease [

1,

2]. Identifying genetic HRR alterations is becoming increasingly important in clinical practice. Firstly, germline alterations are associated with hereditary predisposition to cancer, thus providing grounds for genetic testing of the patient’s relatives. Secondly, genetic defects in the HRR system can lead to homologous recombination repair deficiency (HRD), which makes tumor cells susceptible to DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic drugs and synthetic lethality-inducing agents, such as PARP inhibitors (PARPi). For the time being, all four available PARPi (olaparib, rucaparib, niraparib and talazoparib) have been approved for the use in PC patients, although the nuances of their indications vary between drugs [

3].

The selection of patients for the treatment with single-agent PARPi relies on the identification of deleterious hereditary or somatic HRR mutations. For instance, single-agent olaparib may be prescribed in cases with a mutation in any of the 15 HRR genes included in the initial clinical trial (

ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, BARD1, BRIP1, CDK12, CHEK1, CHEK2, FANCA, PALB2, RAD51, RAD51B, RAD51C, RAD51D, RAD54L) [

4]. The administration of talazoparib relies on another modification of the HRR test, which includes 12 genes (

ATM, ATR, BRCA1, BRCA2, CDK12, CHEK2, FANCA, MLH1, MRE11A, NBN, PALB2, RAD51C) [

5,

6]. Noteworthy, only 8 genes are shared between these 2 panels (

ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, CDK12, CHEK2, FANCA, PALB2, RAD51C). Furthermore, an increasing amount of clinical and experimental data suggests that distinct HRR genes contribute differently to HRD formation and treatment efficacy. For example, the olaparib study observed a clear positive effect in patients with

BRCA2 mutations, while the presence of

ATM or some other genetic defects was associated with minimal or no benefit [

4,

7]. Cell line experiments demonstrated that the loss of

BRCA1/2, RAD51, XRCC2 or

PALB2, but not

ATM or

CHEK2, results in HRD and, consequently, sensitivity to DNA double-strand breaks inducers (platinum drugs, PARP inhibitors, anthracyclines, and topoisomerase I and II inhibitors) [

8]. A recent pooled analysis concluded that PARP inhibitors are beneficial for patients with

BRCA1/2, PALB2 and

CDK12 mutations, but ineffective for PC with

ATM or

CHEK2 genetic defects [

9]. Tumor responses to PARPi or platinum drugs have been reported in patients with

FANCA, BRIP1, RAD51B and

RAD54L mutations, however, this experience remains limited to occasional observations and has not yet been confirmed by the analysis of relevant patient series [

4,

10,

11,

12]. According to NGS-based and functional studies, HRD occurs in breast and prostate cancers with mutations in

RAD51C [

13,

14],

BARD1 [

15] and

RAD51D genes [

16]. However, the available data are scarce and the impact of many other genes involved in HRR processes (

NBN, FANCM, FANCI, FANCC, BLM, MRE11,

ATR, RAD50, etc.) on HRD formation or treatment efficacy is still poorly understood.

Genomic HRD signatures appear to be a more robust predictors of tumor sensitivity to DNA-damaging therapy when compared to mutations in individual HRR genes. Comprehensive genomic studies of

BRCA1/2-associated malignancies have revealed chromosomal profiles and patterns of small mutations, which are highly specific for HRD [

13,

17,

18]. Whole-genome sequencing is probably the most reliable approach for identifying the consequences of homologous recombination deficiency, however, it is not yet compatible with routine clinical practice. An acceptable alternative is the analysis of chromosomal aberration profiles with the targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) SNP panels. In 2016, an HRD score that combines three measures of chromosomal instability, was introduced. It represents a sum of the numbers of genomic LOH regions larger than 15 Mb, large-scale state transitions (LST) (transitions between chromosomal fragments with different copy numbers longer than 10 Mb), and telomeric allelic imbalance (TAI) regions [

19]. This score has been shown to be a reliable predictor of tumor response to PARPi and platinum-based chemotherapy in ovarian and breast cancer [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The diagnostic and predictive role of the HRD score in PC is much less studied [

24,

25,

26]. There are some data suggesting that

BRCA1/2-mutated PCs have generally lower level of chromosomal instability when compared to

BRCA-associated breast or ovarian cancers [

24,

27].

The aim of this study was to characterize the spectrum of HRR mutations in Russian prostate cancer patients and to investigate homologous recombination deficiency by determining the HRD score. Additionally, we aimed to compare HRD scores in patients with mutations in various HRR genes.

2. Results

2.1. Frequency and Spectrum of Mutations in HRR Genes

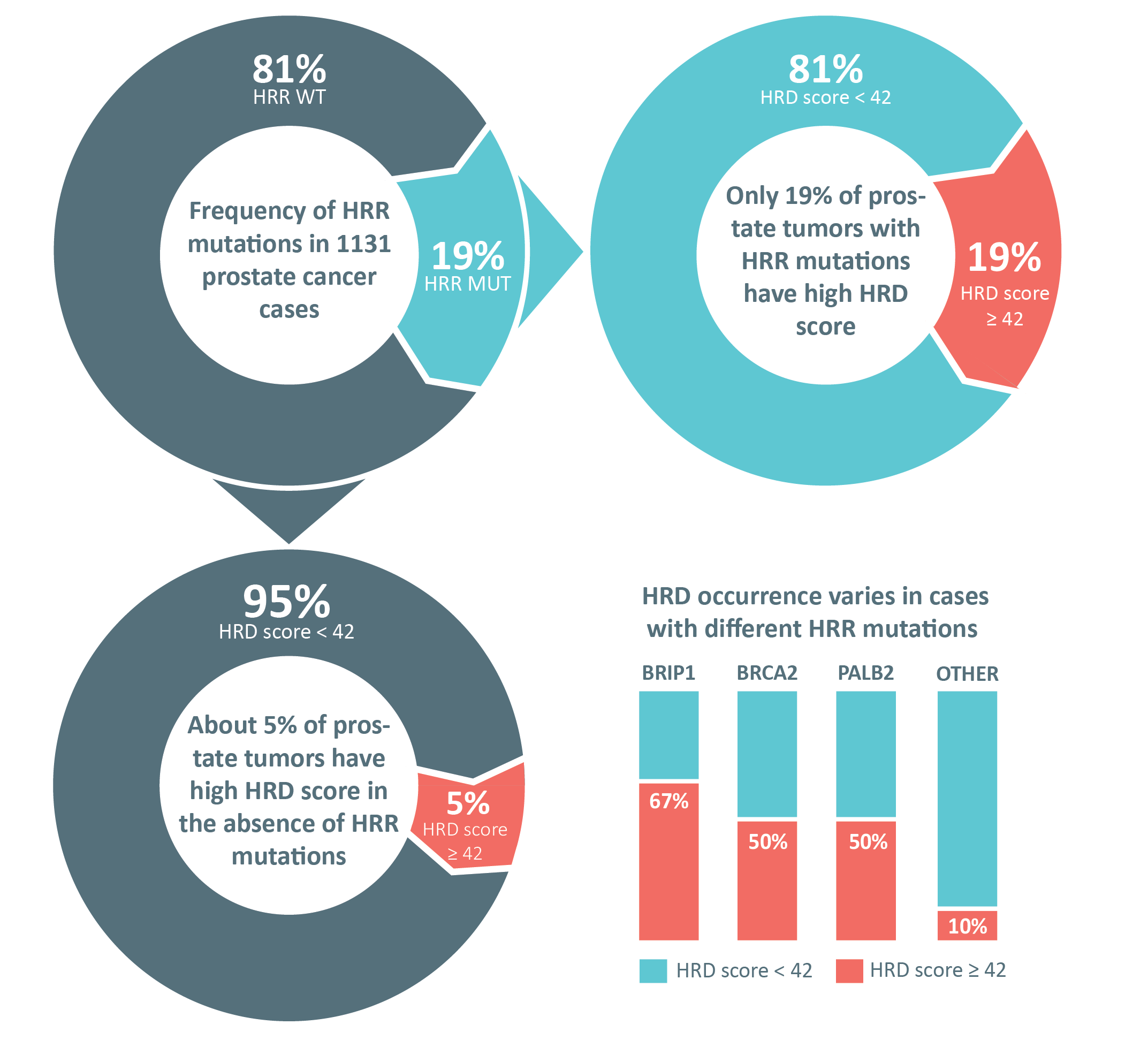

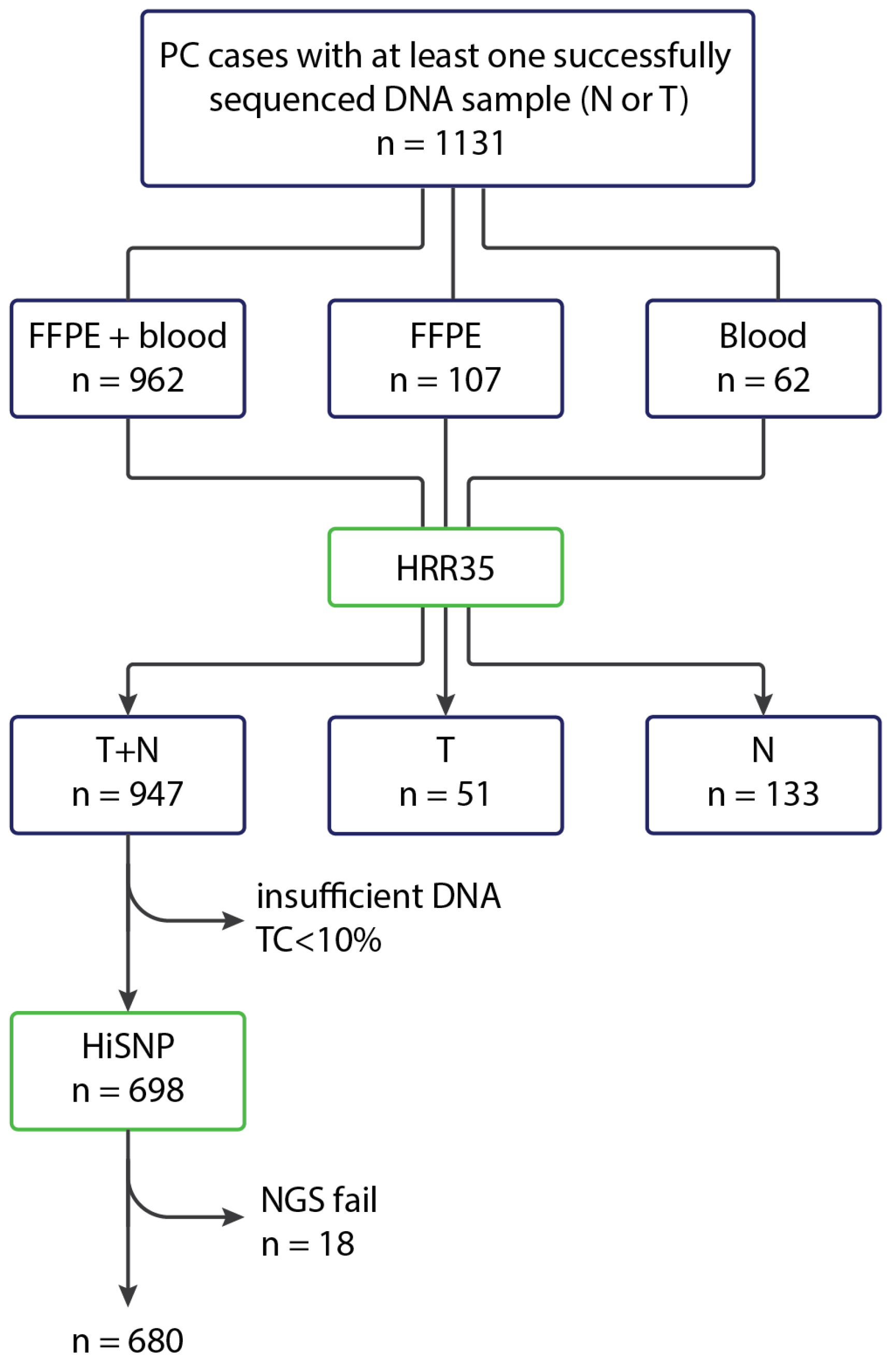

The coding sequences of the HRR genes were analyzed in 1131 prostate cancer cases. The analysis was performed on paired tumor and normal DNA samples in 947 cases. In 51 patients, sequencing data were obtained exclusively from tumor DNA; in another 133 cases, only blood-derived normal DNA was examined. The clinical and morphological characteristics of the samples are presented in

Table 1. Either primary metastatic PC or disease progression after initially localized tumor were diagnosed in 525 patients (46.4% of the total sample or 58.9% of the cases with available clinical information).

Pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline or somatic variants in HRR genes were detected in 216 cases (19.1%), 42 of which had two or three mutations simultaneously. One patient was found to carry a pathogenic germline TP53 alteration, which is an indicator of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. A total of 262 HRR mutations (excluding the case with TP53 variant) were identified in 216 patients, comprising 150 germline and 105 somatic alterations. At least one germline alteration was observed in 142 out of 216 patients (65.8%). Sixty-seven cases (31.0%) presented with only somatic mutations. The origin of the mutations, which were identified in tumor tissues, could not be clarified in seven cases (3.2%) due to the absence of corresponding normal DNA.

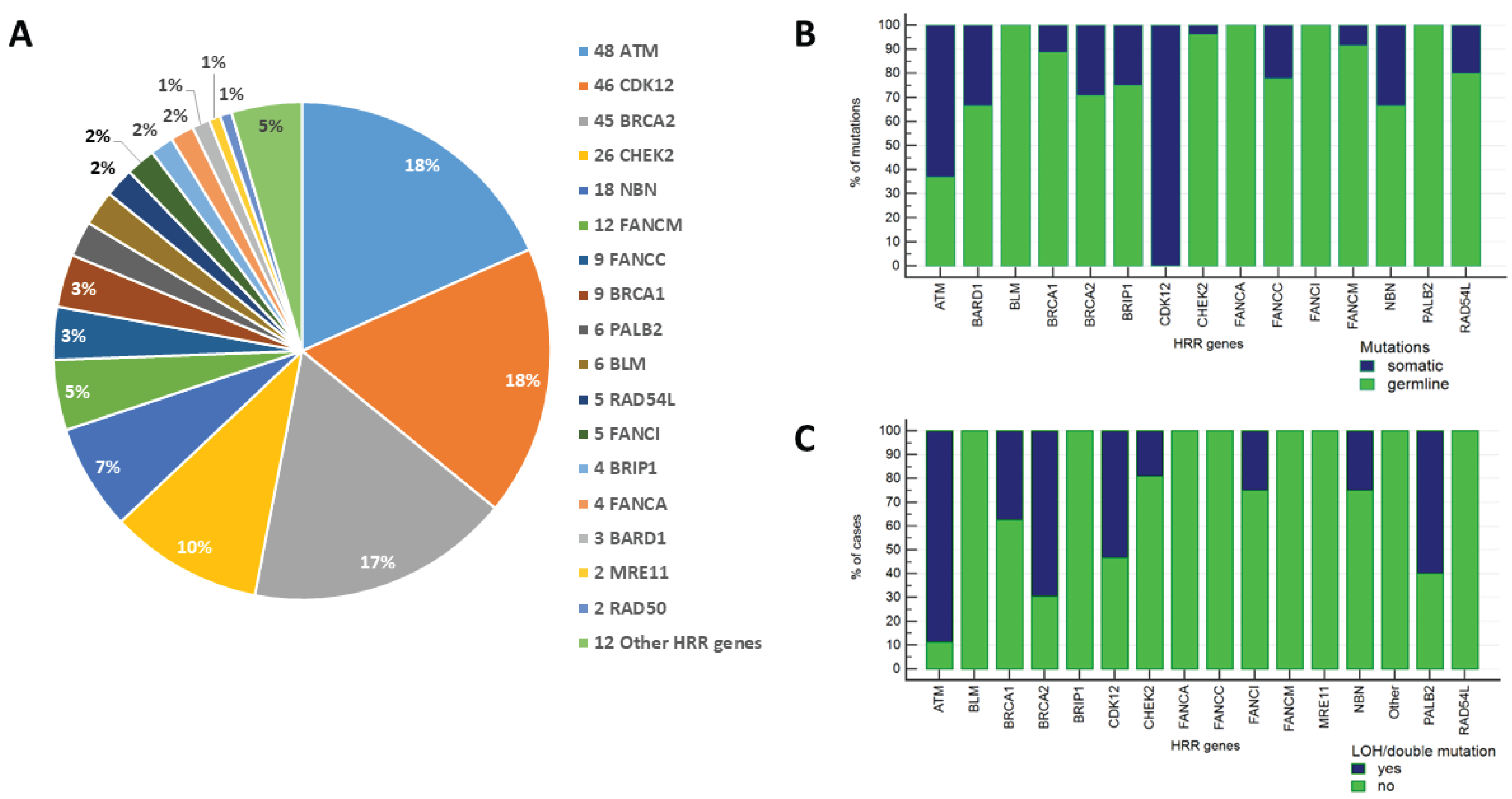

Mutations were most frequently detected in

BRCA2 (42 out of 216 patients with HRR alterations, 19.4%),

ATM (42/216, 19.4%),

CDK12 (30/216, 13.9%),

CHEK2 (26/216, 12.0%),

NBN (15/216, 6.9%), and

FANCM (12/216, 5.6%) genes. Other common alterations were observed for

FANCC (9/216, 4.2%),

BRCA1 (8/216, 3.7%),

PALB2 (6/216, 2.8%),

BLM (6/216, 2.8%),

RAD54L (5/216, 2.3%),

FANCI (5/216, 2.3%),

BRIP1 (4/216, 1.9%),

FANCA (4/216, 1.9%),

BARD1 (3/216, 1.4%),

MRE11 (2/216, 0.9%), and RAD50 (2/216, 0.9%) genes (

Figure 1,

Supplementary Tables S1 and S2,

Supplementary Figure S1). The majority of

BRCA2 defects were of germline origin (29/41, 70.7%), and three patients harbored concurrent germline and somatic

BRCA2 alterations. Overall, either intratumoral loss of the wild-type allele (LOH) in patients with germline

BRCA2 defects or double

BRCA2 mutations, which presumably result in the complete inactivation of the

BRCA2 gene, were observed in 16 out of 23 (69.6%) informative cases. Germline

ATM mutations were identified in 17 out of 40 (42.5%)

ATM-altered cases, while LOH or a combination of somatic and germline

ATM variants occurred in 16 out of 18 (88.9%) informative cases. The third most frequently affected HRR gene was

CDK12, which is known to harbor exclusively somatic alterations in PCs. Approximately a half of PCs with

CDK12 variants (16/30, 53.3%) bore double inactivating somatic mutations. The vast majority of mutations in the other HRR genes were of germline origin; LOH of the remaining allele of the involved gene was observed infrequently in these tumors, except for

PALB2 (

Supplementary Table S2).

The spectrum of

BRCA2 and

ATM germline variants was highly heterogeneous and contained only few recurrent mutations. In contrast, almost all

CHEK2, NBN and

BRCA1 defects were represented by founder or recurrent variants: 22/26 (84.6%)

CHEK2 alterations belonged to one of the three founder alleles (

CHEK2 c.1100delC, c.444+1G>A and del5395); Slavic founder deletion

NBN c.657del5 constituted 12/15 (80%) of

NBN mutations; 6 (66.7%) out of 9

BRCA1 mutations were recurrent c.3700_3704delGTAAA [3819del5], c.4034delA [4153delA], c.5266dup [5382insC], or c.181T>G [p.C61G] variants. Other founder pathogenic alleles were represented by

FANCM c.1972C>T (p.Arg658Ter) (n = 4),

FANCI c.3853C>T (p.Arg1285Ter) (n = 4),

BLM c.1642C>T (p.Gln548Ter) (n = 4),

FANCC c.996+1G>T (n = 2), and

BARD1 c.1690C>T (p.Gln564Ter) (n = 2) mutations (

Supplementary Table S1).

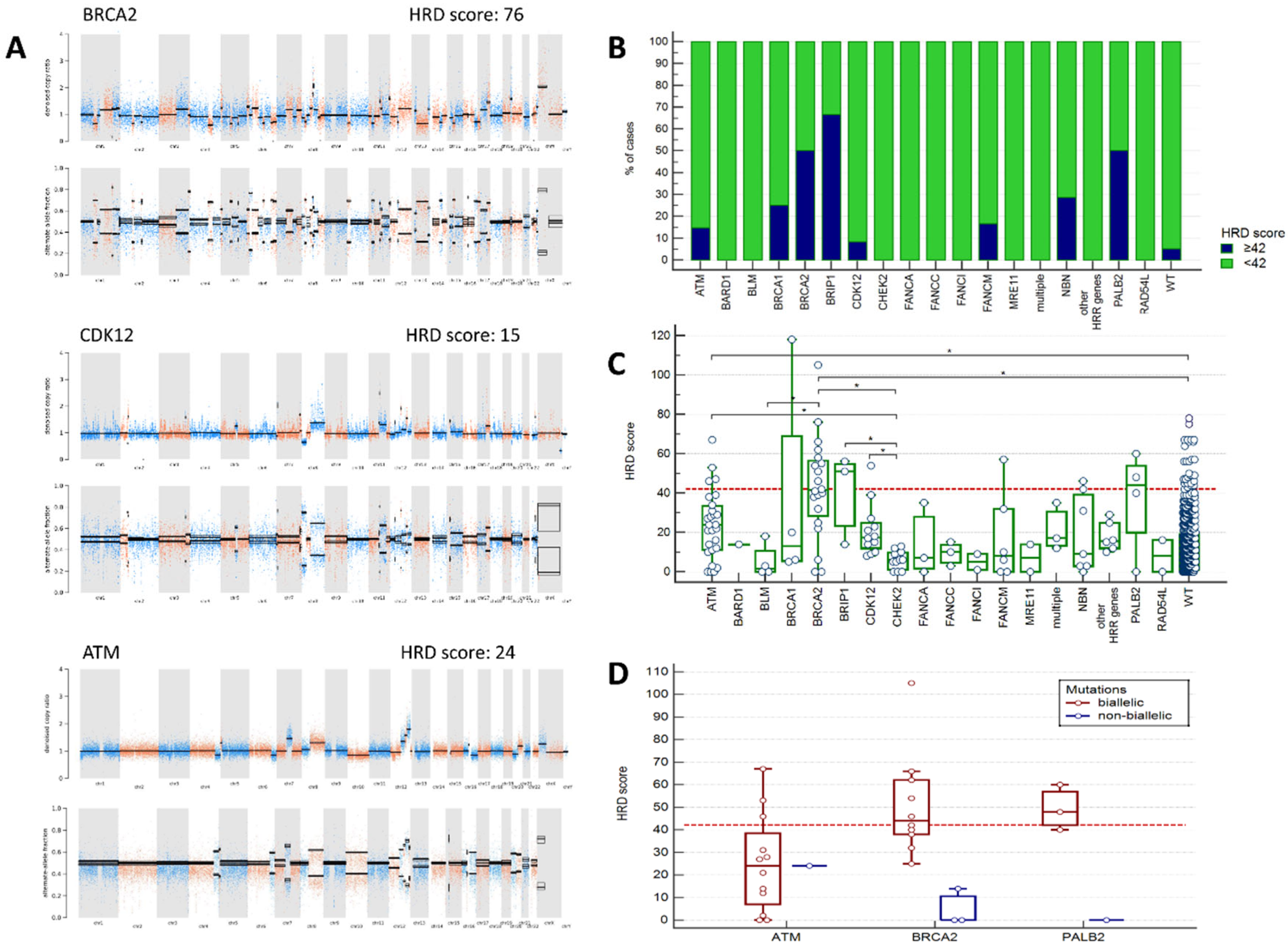

2.2. Analysis of HRD Scores

HRD scores were obtained in 680 PC cases, including 120 cases with genetic alterations in HRR genes. HRD score equal or higher than 42 was observed in 23/120 (19.2%) PCs with altered HRR genes and in 29/560 (5.2%) tumors from patients without any identified HRR mutations (p < 0.0001). The proportion of cases with HRD score ≥ 42 was the highest in tumors with

BRCA2, PALB2 and

BRIP1 mutations (50%, 50%, and 67%, respectively,

Figure 2B,

Supplementary Table S3). While only half of

BRCA2-associated PC had the score above the chosen threshold, the majority of them (14/20, 70%) demonstrated the score very close (≥ 38) to the predefined point cut-off (≥ 42). Interestingly, two cases with germline

BRCA2 variants not having

BRCA2 LOH in the tumor showed no signs of chromosomal instability (score = 0). Among 4 analyzed

PALB2-associated PCs, all three cases with germline alterations accompanied by somatic LOH of the wild-type allele had HRD score higher or very close to the chosen threshold (40, 48, 60), and the case with germline mutation without LOH had stable tumor (score = 0) (

Figure 2D). High HRD scores were occasionally observed in PCs with

ATM, NBN, FANCM, BRCA1 and

CDK12 mutations, but not in cases with

CHEK2 mutations. Of notice, only 3/12 (25%) PCs with putative

ATM biallelic inactivation showed high HRD scores (

Supplementary Figure S1).

When analyzed as continuous variable, HRD score in cancers with

BRCA2 and

ATM alterations was significantly higher than in those without identified HRR mutations.

CHEK2-associated tumors showed the lowest HRD values and differed in this respect from

ATM-, BRCA2-, BRIP1-, or

CDK12-mutation positive cases (

Figure 2C,

Supplementary Table S3).

The majority of tumors with

CDK12 somatic alterations (11/13, 84.6%) had clearly distinguishable CNV profiles with genome-wide narrow spikes suggestive of a tandem duplicator phenotype [

28,

29] (

Figure 2A). Interestingly, one of the samples categorized as HRR WT showed a

CDK12-specific CNV profile. Re-analysis of NGS data in the genome browser led to identification of a gross

CDK12 deletion, which was further confirmed by PCR (

Supplementary Figure S2).

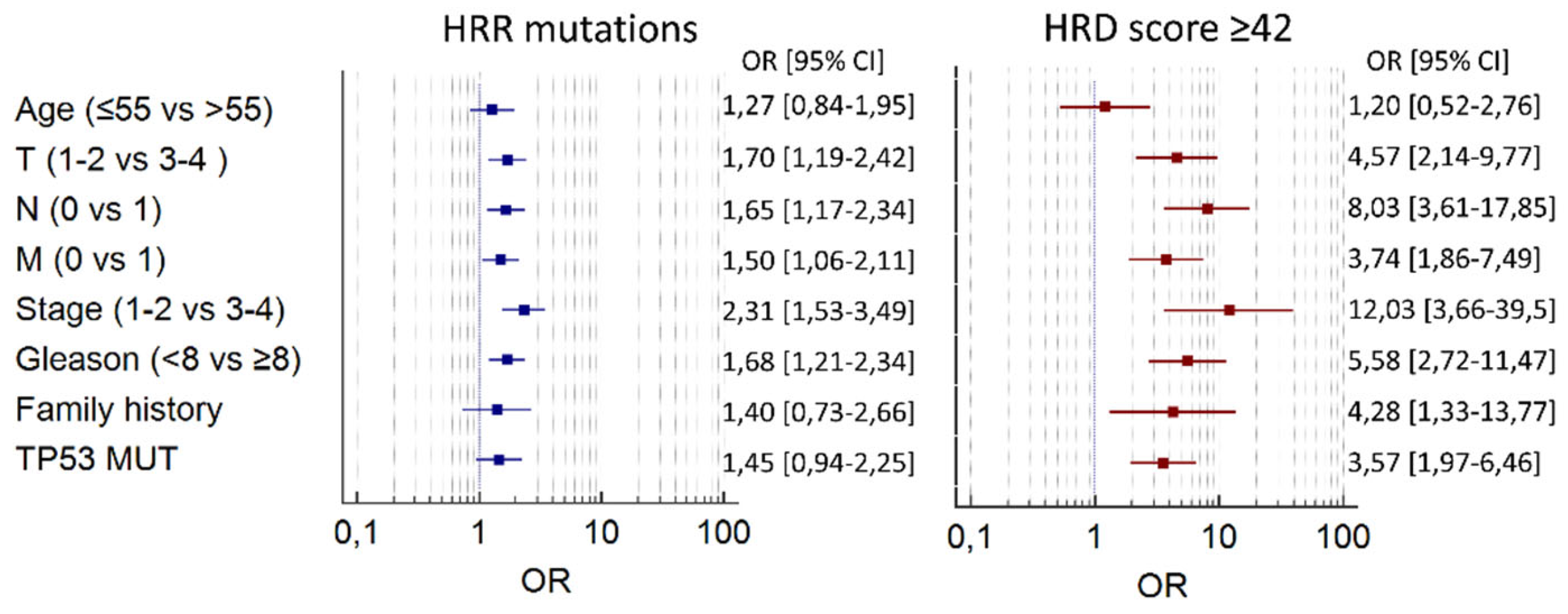

2.3. Clinicopathological Associations

Neither mutations in HRR genes nor HRD were associated with the age at PC diagnosis. Both HRR alterations and high HRD scores were enriched in PCs with aggressive clinical features, such as high tumor stage and grade (

Table 2,

Figure 3). These associations were more pronounced for HRD than for HRR status. For example, HRD score ≥ 42 was almost never observed in stage I PC (0.7%) compared to stage IV tumors (16%, p<0.0001). High HRD was also strongly associated with the presence of somatic TP53 alterations (

Table 2,

Figure 3).

3. Discussion

This study characterized the spectrum of mutations in an expanded list of HRR genes in prostate cancer. The incidence of pathogenic/likely pathogenic HRR alterations in our cohort (19%) generally corresponds to published data on the prevalence of HRR mutations in mCRPC, reflecting the fact that our cohort was enriched with aggressive PC subtypes [

1,

20,

30]. Hereditary variants were identified in the majority (142/216; 66%) of cases with HRR alterations. Of these, 103 patients (8.6% of the total sample) carried germline pathogenic variants in genes that have been definitively linked to an increased risk of PC or other types of cancers (

BRCA2, ATM, CHEK2, NBN, BRCA1, PALB2, BRIP1 and

BARD1) [

31,

32,

33]. The share of germline variants in the above-mentioned genes reached 9.6% in PC with high Gleason grade and 10.9% in stage III-IV tumors. Approximately one third of the identified germline variants were found in genes with an unclear or yet unstudied relationship to PC predisposition, including

FANCA, FANCC, FANCI, FANCM, RAD54L, MRE11, RAD50, etc. [

34,

35]. It is important to acknowledge that the actual frequency of somatic HRR alterations may be somewhat higher than we observed. This is attributable to the fact only normal DNA was subjected to sequencing in 133/1131 (11.8%) patients included in this investigation.

An important objective of this study was to compare intratumoral HR status (as determined by HRD score) with the mutational status of various HRR genes, in order to ascertain the association of these genes with HRD-type chromosomal instability. Our results suggest that only a minority (19%) of HRR-mutated PCs have a pronounced homologous recombination deficiency (HRD score ≥ 42), and that the inactivation of different genes is associated with varying degrees of chromosomal instability. Notably, the highest HRD scores were observed in PCs with

BRCA2 (median 41.5),

PALB2 (44) and

BRIP1 (51.0) alterations. An HRD score of at least 42 was found in only a half of

BRCA2-positive carcinomas. This threshold is clinically significant in ovarian and breast cancer, allowing the detection of 95% of

BRCA-positive tumors of these types [

19]. Our data, along with the results of several similar studies, suggest that HRD scores tend to be lower in PCs, including

BRCA2-associated tumors [

24,

26,

27]. Consequently, the clinically relevant cut-off for the HRD score in PC may be somewhat lower than 42. This assumption awaits further evaluation in clinical trials. Interestingly, we observed two cases with germline

BRCA2 variants and retention of the wild-type

BRCA2 allele in tumors with no signs of chromosomal instability (score = 0), suggesting that the development of these malignancies was not related to

BRCA2-associated syndrome.

Previous studies have shown that

PALB2 inactivation results in genomic features of HRD [

13,

14,

15,

36,

37,

38]. The results of the PARPi trials also favor the efficacy of PARPi in PC with

PALB2 mutations [

4,

10,

39]. Our data are consistent with these observations, as all three tumors with biallelic

PALB2 lesions had HRD scores above or very close to the threshold. Similar to

BRCA2, a case with germline

PALB2 mutation and the absence of somatic LOH had a chromosomally stable tumor (

Figure 2D). It can be concluded that for hereditary

BRCA2 and

PALB2 mutations, the intratumoral loss of the wild-type allele is the main mechanism of somatic second hit, resulting in elevated chromosomal instability.

BRIP1 mutations increase the risk of ovarian cancer, and it has been demonstrated that

BRIP1-deficient cells are sensitive to combined treatment with platinum drugs and PARPi [

40]. The number of observations was small, however, we identified HR deficiency in two out of three cases with

BRIP1 alterations.

This study included four cases with

BRCA1 mutations; only one of those, involving a germline variant accompanied by somatic LOH, had a high HRD score. These results are consistent with data showing that in PC, biallelic alterations in

BRCA1 gene are less common than the genetic inactivation of the

BRCA2, and accordingly,

BRCA1-associated tumors are less likely to show signs of HRD [

27].

PCs with ATM alterations were heterogeneous in terms of HRD-specific chromosomal instability. The median HRD score was higher in

ATM-positive tumors (score = 24) than in cases without HRR alterations (score = 10) (p = 0.0005), but lower than in

BRCA2-related cases (score = 41.5) (p = 0.005). Only three out of twelve (25%) PCs with putative biallelic

ATM inactivation demonstrated HRD scores of at least 42; all these tumors had a combination of a germline pathogenic variant coupled with a second-hit somatic genetic event. These observations are in good agreement with the multiple data, which argue for low sensitivity of

ATM-related PCs to PARPi [

7,

9].

CHEK2 and NBN are important cancer-predisposing loci in Slavic and North European populations. Mutations in these genes accounted for 12% and 7% of all HRR-altered cases, respectively, and were predominantly represented by a few founder variants. PCs with CHEK2 alterations were characterized by the lowest HRD scores (all below 20). Two out of eight (25%) NBN-related tumors had HRD; one of these cases had a combination of hereditary and somatic truncating variants.

High HRD scores were not detected in cases with

BLM, FANCA, FANCC, FANCI, RAD54L or

MRE11 pathogenic variants. They were, however, observed in single patients with

FANCM and

CDK12 inactivating alleles. Tumors with biallelic

CDK12 mutations constitute a distinct PC subtype. These tumors are known to be prevalent in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, have a poor prognosis and exhibit a characteristic pattern of genome-wide tandem duplications [

28,

29]. In our cohort, 85% of cases with

CDK12 mutations exhibited the tandem duplication phenotype, including cases with single and double

CDK12 variants. Contrary to initial expectations, prostate cancer cases with

CDK12 mutations were found not to have typical HRD features; furthermore, there are several lines of evidences suggesting that

CDK12-associated PCs demonstrate comparatively low sensitivity to PARP inhibitors [

10,

41,

42,

43]. It has been suggested that prostate cancer with

CDK12 mutations could be sensitive to immune checkpoint inhibitors due to the increased number of fusions; however, this hypothesis has not been confirmed by clinical data [

44]. Nevertheless, recent animal study showed sensitivity of double

CDK12/TP53 knockout PC to immune checkpoint inhibitors [

45]. Furthermore, CDK12 deficiency has been found to exhibit synthetic lethality when its paralog CDK13 is pharmacologically targeted, suggesting that this could be a promising novel treatment approach for this type of prostate cancer [

45,

46].

A substantial portion of PC cases without identified HRR mutations (5%) had a high HRD score. Large genomic studies have shown that up to one-third of all cases of HRD in metastatic PC are associated with gross biallelic deletions of the

BRCA2 gene, which are not detectable by conventional targeted NGS [

14,

47,

48]. HRD may be also caused by epigenetic inactivation of HRR genes, functional mutations in non-coding regions, or alterations in genes not included in the 34 loci analyzed in this study [

14]. Our results suggest that the analysis chromosomal instability has a potential to expand the range of patients eligible for treatment with PARPi or platinum drugs.

This study confirmed the association between increased chromosomal instability and somatic

TP53 mutations, which has been described in PC and other tumor types [

24,

26,

49].

4. Materials and Methods

The study group comprised 1131 prostate cancer patients referred to the N.N. Petrov National Medical Research Centre of Oncology between October 2022 and March 2025. Mutations in HRR genes were identified using the HRR35 targeted NGS panel (Nanodigmbio, China). CNV profiles were analyzed with the HiSNP Ultra Panel v1.0 (Nanodigmbio, China). The HRR35 panel includes all loci that are associated with administration of PARPi as well as several other HRR genes (BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, PALB2, BARD1, RAD51, RAD51B, RAD51C, RAD51D, RAD54L, CDK12, BRIP1, CHEK2, FANCA, NBN, ATR, BLM, CHEK1, FANCC, FANCD2, FANCE, FANCF, FANCG, FANCI, FANCL, FANCM, MRE11, PPP2R2A, RAD50, RAD52, RBBP8, RPA1, SLX4, XRCC2) and the TP53 gene. The HiSNP panel enables the analysis of over 52000 common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with a resolution of around 50 Kb, making it suitable for determining the HRD score.

Participating physicians were encouraged to submit to the study both tumor and blood samples. Of the 1131 PCs, the material forwarded for targeted sequencing comprised paired blood and archival tumor samples in 962 cases, only archival histological material in 107 cases, and only blood samples in 62 cases (

Figure 4). In instances where blood samples were not available, both tumor and normal tissues were manually microdissected from the archival histological material wherever possible. FFPE samples containing less than 10% tumor cells were excluded from the analysis of somatic HRR mutations and were not sequenced using the HiSNP Ultra Panel v1.0.

DNA extraction from FFPE samples was performed using the ExtractDNA FFPE reagent kit (Eurogen, Russia). DNA library preparation for sequencing was carried out using the NadPrep EZ DNA Library Preparation Kit (Nanodigmbio, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The concentration of DNA libraries was assessed using a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and the fragmentation quality and average size were determined with a Fragment Analyzer 5200 (Agilent Technologies, USA). All 1131 studied cases were subjected to NGS using the HRR35 panel. For this purpose, DNA libraries with sufficient concentration (at least 500 ng) were pooled in sets of 12 for enrichment with HRR35 probes. In 680 cases where paired tumor and normal material was available, and where the concentrations of both libraries in each pair were sufficient for a second enrichment, hybridization was subsequently performed using the HiSNP Ultra Panel v1.0 probes. Enrichment with target probes was performed using the NadPrep Hybrid Capture Reagents kit (Nanodigmbio, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After enrichment, the DNA libraries were circularized using the NadPrep Universal Circularization Kit (Nanodigmbio, China). DNA libraries were then sequenced in paired-end mode for 150 cycles in each direction using the DNBSEQ-50 instrument (MGItech, China).

Primary bioinformatic processing of the sequencing data involved the following standard steps: generation of FASTQ files; quality assessment; and alignment of the obtained sequences to the hg19 human reference genome using the BWA tool. The HaplotypeCaller software (GATK4) was then used to search for single nucleotide variants and small insertions/deletions. Somatic mutations in HRR genes were detected using the MuTect2 tool. DNA sequences were annotated using the SnpEff software tool. Only somatic mutations with a depth of coverage greater than 10, detected in both the forward and reverse reads, were considered. Samples with a mean coverage of less than 100x, or with less than 80% of the target sequences covered at a depth of at least 30x, were excluded from the analysis. Detected HRR variants were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic if they had been already described in medical literature or ClinVar database, or if they represented previously undescribed or rare (<0.5% frequency in gnomAD population database) truncating germline variants. Somatic truncating variants were also considered pathogenic.

For germline variants, loss of heterozygosity (LOH) was assessed in the corresponding tumor, where available. LOH was confirmed if the tumor sample showed a variant allele frequency of more than 65% of the total reads.

Following sequencing with the HiSNP panel, somatic copy number variation (CNV) plots were constructed using the ACNV tool integrated into the GATK package [

50]. The HRD score was calculated as the sum of the LOH, TAI and LST scores, defined as described in 51]. The threshold level for the presence of HRD was set at an HRD score of at least 42.

The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the age of patients with and without HRR mutations, as well as those with high and low HRD scores. Associations for categorical data were assessed using Pearson’s chi-squared test, Fisher’s exact test or the Cochran–Armitage test for trend (for tumor size and stage). The odds ratios with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated to determine the strength of associations between the presence of HRR mutations or high HRD scores and clinical parameters. The Kruskal–Wallis test with Conover post-hoc test was used to compare HRD score values in different categories of PC. A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

Approximately 10% of patients with aggressive PC carry germline pathogenic variants in genes with established roles in cancer predisposition (BRCA2, ATM, CHEK2, NBN, BRCA1, PALB2, BRIP1, BARD1). A significant proportion of PC with BRCA2 mutations, including those with confirmed biallelic lesions, exhibit an HRD score below the commonly accepted threshold. Mutations in BRCA2, PALB2 and BRIP1 genes are associated with the highest level of chromosomal instability, whereas alterations in the other HRR loci (CHEK2, NBN, BLM, FANCA, FANCC, FANCI, RAD54L, MRE11, CDK12) are unlikely to result in HRD. PC with ATM mutations, including those with biallelic variants, exhibit high variability in HRD score values. The analysis of HRD score enables the identification of a significant number of PC cases, which are negative by HRR mutation testing but potentially sensitive to PARPi or platinum drugs.

Compared to targeted HRR genes analysis, HRD testing requires more powerful NGS equipment. Although it is routinely used in the treatment planning of ovarian cancer, HRD has not yet been incorporated into the management of breast and prostate carcinomas, probably because the availability of tumor tissue for these tumor entities is often limited to tiny biopsied material. Our study strongly suggests that attitudes towards selection of PC patients for PARPi treatment require significant revision. In fact, current versions of HRR tests often urge for the use of PARPi in those PC patients, who are unlikely to respond to this treatment, while they also miss a substantial portion of men, who show convincing features of potential tumor sensitivity to PARPi or some cytotoxic agents. Our data suggest that HRR gene panels require some modifications, e.g., the exclusion of CHEK2 and, perhaps, several other genes. At the same time, wherever possible, HRR tests should be supplemented by HRD assays, or, at least, by biallelic analysis of the genes affected by mutations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Schematic representation of HRR mutations identified in 216 PC cases; Figure S2: Detection of a CDK12 deletion; Table S1: The list of all identified mutations in HRR genes; Table S2: Characteristics of mutations in various HRR genes; Table S3: Frequency of HRD score ≥ 42 in cases with and without HRR mutations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.I., S.N.A. and E.N.I.; methodology, S.N.A., A.P.S., E.A.O., and K.A.K.; investigation, S.V.P., P.V.V., A.S.P., T.M.T., O.M.G., R.V.O., O.N.S., A.V.B., A.D.S., A.V.L., D.O.M., D.V.G., A.V.D., I.Yu.P., A.V.A., V.F.K., M.M.G., A.N.O., S.I.L., M.N.N., E.N.V., I.K.A., N.V.K., L.I.Z., A.B.G., V.N.K., O.I.S., N.V.P., N.A.B., and A.M.B.; data curation, A.P.S., A.S.N., M.V.S., E.Sh.K., N.S.M., and T.Yu.L.; software, M.V.S. and N.S.M.; visualization, A.G.I. and E.Sh.K.; project administration S.N.A., A.M.B., and E.N.I.; resources, S.N.A. and A.M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.I. and S.N.A.; writing—review and editing, A.G.I. and E.N.I.; supervision—A.G.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation, grant number 23-15-00262.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of NMRC of Oncology named after N.N. Petrov (protocol № 20/25 dated 23.01.2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| HRD |

Homologous recombination deficiency |

| HRR |

Homologous recombination repair |

| LOH |

Loss of heterozygosity |

| mCRPC |

Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| PARPi |

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors |

| PC |

Prostate cancer |

References

- Robinson, D.; Van Allen, E.M.; Wu, Y.M.; Schultz, N.; Lonigro, R.J.; Mosquera, J.M; Montgomery, B.; Taplin, M.E.; Pritchard, C.C.; Attard, G; et al. Integrative Clinical Genomics of Advanced Prostate Cancer. Cell 2015, 162, 454. [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, C.C.; Mateo, J.; Walsh, M.F.; De Sarkar, N.; Abida, W.; Beltran, H.; Garofalo, A.; Gulati, R.; Carreira, S.; Eeles, R.; et al. Inherited DNA-Repair Gene Mutations in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 443-453. [CrossRef]

- Fenor de la Maza, M.D.; Pérez Gracia, J.L.; Miñana, B.; Castro, E. PARP inhibitors alone or in combination for prostate cancer. Ther Adv Urol 2024, 16, 17562872241272929. [CrossRef]

- de Bono, J.; Mateo, J.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Shore, N.; Sandhu, S.; Chi, K.N.; Sartor, O.; Agarwal, N.; Olmos, D.; et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 2091-2102. [CrossRef]

- de Bono, J.S.; Mehra, N.; Scagliotti, G.V.; Castro, E.; Dorff, T.; Stirling, A.; Stenzl, A.; Fleming, M.T.; Higano, C.S.; Saad, F.; et al. Talazoparib monotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with DNA repair alterations (TALAPRO-1): an open-label; phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2021, 9, 1250-1264. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Azad, A.A.; Carles, J.; Fay, A.P.; Matsubara, N.; Szczylik, C.; De Giorgi, U.; Young Joung, J.; Fong, P.C.C.; Voog, E.; et al. Talazoparib plus enzalutamide in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: final overall survival results from the randomised; placebo-controlled; phase 3 TALAPRO-2 trial. Lancet 2025, 406, 447-460. [CrossRef]

- Stopsack, K.H. Efficacy of PARP inhibition in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer is very different with non-BRCA DNA repair alterations: reconstructing prespecified endpoints for cohort B from the phase 3 PROfound trial of olaparib. Eur Urol 2021, 79, 442-445. [CrossRef]

- Póti, Á.; Gyergyák, H.; Németh, E.; Rusz, O.; Tóth, S.; Kovácsházi, C.; Chen, D.; Szikriszt, B.; Spisák, S.; Takeda, S.; et al. Correlation of homologous recombination deficiency induced mutational signatures with sensitivity to PARP inhibitors and cytotoxic agents. Genome Biol 2019, 20, 240. [CrossRef]

- Fallah, J.; Xu, J.; Weinstock, C.; Gao, X.; Heiss, B.L.; Maguire, W.F.; Chang, E.; Agrawal, S.; Tang, S.; Amiri-Kordestani, L.; et al. Efficacy of Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase Inhibitors by Individual Genes in Homologous Recombination Repair Gene-Mutated Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: A US Food and Drug Administration Pooled Analysis. J Clin Oncol 2024, 42, 1687-1698. [CrossRef]

- Abida, W.; Campbell, D.; Patnaik, A.; Bryce, A.H.; Shapiro, J.; Bambury, R.M.; Zhang, J.; Burke, J.M.; Castellano, D.; Font, A.; et al. Rucaparib for the Treatment of Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer Associated with a DNA Damage Repair Gene Alteration: Final Results from the Phase 2 TRITON2 Study. Eur Urol 2023, 84, 21-330. [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R.; Scher, H.I.; Sandhu, S.; Efstathiou, E.; Lara, P.N. Jr.; Yu, E.Y.; George, D.J.; Chi, K.N.; Saad, F.; Ståhl, O.; et al. Niraparib in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer and DNA repair gene defects (GALAHAD): a multicentre; open-label; phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2022, 23, 362-373. [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, D.C.; Sailer, V.; Xue, H.; Cheng, H.; Collins, C.C.; Gleave, M.; Wang, Y.; Demichelis, F.; Beltran, H.; Rubin, M.A.; Rickman, D.S. A germline FANCA alteration that is associated with increased sensitivity to DNA damaging agents. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud 2017, 3, a001487. [CrossRef]

- Polak, P.; Kim, J.; Braunstein, L.Z.; Karlic, R.; Haradhavala, N.J.; Tiao, G.; Rosebrock, D.; Livitz, D.; Kübler, K.; Mouw, K.W.; et al. A mutational signature reveals alterations underlying deficient homologous recombination repair in breast cancer. Nat Genet 2017, 49, 1476-1486. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.; W M Martens, J.; Van Hoeck, A.; Cuppen, E. Pan-cancer landscape of homologous recombination deficiency. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 5584. [CrossRef]

- Dillon, K.M.; Bekele, R.T.; Sztupinszki, Z.; Hanlon, T.; Rafiei, S.; Szallasi, Z.; Choudhury, A.D.; Mouw, K.W. PALB2 or BARD1 loss confers homologous recombination deficiency and PARP inhibitor sensitivity in prostate cancer. NPJ Precis Oncol 2022, 6, 49. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Esquius, S.; Llop-Guevara, A.; Gutiérrez-Enríquez, S.; Romey, M.; Teulé, À.; Llort, G.; Herrero, A.; Sánchez-Henarejos, P.; Vallmajó, A.; González-Santiago, S.; et al. Prevalence of Homologous Recombination Deficiency Among Patients With Germline RAD51C/D Breast or Ovarian Cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e247811. [CrossRef]

- Davies, H.; Glodzik, D.; Morganella, S.; Yates, L.R.; Staaf, J.; Zou, X.; Ramakrishna, M.; Martin, S.; Boyault, S.; Sieuwerts, A.M.; et al. HRDetect is a predictor of BRCA1 and BRCA2 deficiency based on mutational signatures. Nat Med 2017, 23, 517-525. [CrossRef]

- Quigley, D.A.; Dang, H.X.; Zhao, S.G.; Lloyd, P.; Aggarwal, R.; Alumkal, J.J.; Foye, A.; Kothari, V.; Perry, M.D.; Bailey, A.M.; et al. Genomic Hallmarks and Structural Variation in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Cell 2018, 174, 758-769. [CrossRef]

- Telli, M.L.; Timms, K.M.; Reid, J.; Hennessy, B.; Mills, G.B.; Jensen, K.C.; Szallasi, Z.; Barry, W.T.; Winer, E.P.; Tung, N.M.; et al. Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) Score Predicts Response to Platinum-Containing Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2016, 22, 3764-3773. [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.R.; Monk, B.J.; Herrstedt, J.; Oza, A.M.; Mahner, S.; Redondo, A.; Fabbro, M.; Ledermann, J.A.; Lorusso, D.; Vergote, I.; et al. Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive; Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 2154-2164. [CrossRef]

- Swisher, E.M.; Lin, K.K.; Oza, A.M.; Scott, C.L.; Giordano, H.; Sun, J.; Konecny, G.E.; Coleman, R.L.; Tinker, A.V.; O’Malley, D.M.; et al. Rucaparib in relapsed; platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma (ARIEL2 Part 1): an international; multicentre; open-label; phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017, 18, 75-87. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.L.; Oza, A.M.; Lorusso, D.; Aghajanian, C.; Oaknin, A.; Dean, A.; Colombo, N.; Weberpals, J.I.; Clamp, A.; Scambia, G.; et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised; double-blind; placebo-controlled; phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 1949-1961. [CrossRef]

- Sokolenko, A.P.; Gorodnova, T.V.; Bizin, I.V.; Kuligina, E.S.; Kotiv, K.B.; Romanko, A.A.; Ermachenkova, T.I.; Ivantsov, A.O.; Preobrazhenskaya, E.V.; Sokolova, T.N.; et al. Molecular predictors of the outcome of paclitaxel plus carboplatin neoadjuvant therapy in high-grade serous ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2021, 88, 439-450. [CrossRef]

- Lotan, T.L; Kaur, H.B; Salles, D.C; Murali, S.; Schaeffer, E.M.; Lanchbury, J.S.; Isaacs, W.B.; Brown, R.; Richardson, A.L.; Cussenot, O.; et al. Homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) score in germline BRCA2- versus ATM-altered prostate cancer. Mod Pathol 2021, 34, 1185-1193. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, A.; Li, Y.; Cai, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhou, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. Establishing the homologous recombination score threshold in metastatic prostate cancer patients to predict the efficacy of PARP inhibitors. J Natl Cancer Cent 2024, 4, 280-287. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhao, J.; Nie, L.; Yin, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Dai, J.; et al. Homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) score in aggressive prostatic adenocarcinoma with or without intraductal carcinoma of the prostate (IDC-P). BMC Med 2022, 20, 237. [CrossRef]

- Sokol, E.S.; Pavlick, D.; Khiabanian, H.; Frampton, G.M.; Ross, J.S.; Gregg, J.P.; Lara, P.N.; Oesterreich, S.; Agarwal, N.; Necchi, A.; et al. Pan-Cancer Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Genomic Alterations and Their Association With Genomic Instability as Measured by Genome-Wide Loss of Heterozygosity. JCO Precis Oncol 2020, 4, 442-465. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.; Mota, J.M.; Nandakumar, S.; Stopsack, K.H.; Weg, E.; Rathkopf, D.; Morris, M.J.; Scher, H.I.; Kantoff, P.W.; Gopalan, A.; et al. Pan-cancer Analysis of CDK12 Alterations Identifies a Subset of Prostate Cancers with Distinct Genomic and Clinical Characteristics. Eur Urol 2020, 78, 671-679. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.M.; Cieślik, M.; Lonigro, R.J.; Vats, P.; Reimers, M.A.; Cao, X.; Ning, Y.; Wang, L.; Kunju, L.P.; de Sarkar, N.; et al. Inactivation of CDK12 Delineates a Distinct Immunogenic Class of Advanced Prostate Cancer. Cell 2018, 173, 1770-1782. [CrossRef]

- Lukashchuk, N.; Barnicle, A.; Adelman, C.A.; Armenia, J.; Kang, J.; Barrett, J.C.; Harrington, E.A. Impact of DNA damage repair alterations on prostate cancer progression and metastasis. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1162644. [CrossRef]

- Ni Raghallaigh, H.; Eeles, R. Genetic predisposition to prostate cancer: an update. Fam Cancer 2022, 21, 101-114. [CrossRef]

- Kote-Jarai, Z.; Jugurnauth, S.; Mulholland, S.; Leongamornlert, D.A.; Guy, M.; Edwards, S.; Tymrakiewitcz, M.; O’Brien, L.; Hall, A.; Wilkinson, R.; et al. A recurrent truncating germline mutation in the BRIP1/FANCJ gene and susceptibility to prostate cancer. Br J Cancer 2009, 100, 426-30. [CrossRef]

- Stempa, K.; Wokołorczyk, D.; Kluźniak, W.; Rogoża-Janiszewska, E.; Malińska, K.; Rudnicka, H.; Huzarski, T.; Gronwald, J.; Gliniewicz, K.; Dębniak, T.; et al. Do BARD1 Mutations Confer an Elevated Risk of Prostate Cancer? Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 5464. [CrossRef]

- Ledet, E.M.; Antonarakis, E.S.; Isaacs, W.B.; Lotan, T.L.; Pritchard, C.; Sartor, A.O. Germline BLM mutations and metastatic prostate cancer. Prostate 2020, 80, 235-237. [CrossRef]

- Otahalova, B.; Volkova, Z.; Soukupova, J.; Kleiblova, P.; Janatova, M.; Vocka, M.; Macurek, L.; Kleibl, Z. Importance of Germline and Somatic Alterations in Human MRE11; RAD50; and NBN Genes Coding for MRN Complex. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 5612. [CrossRef]

- De Sarkar, N.; Dasgupta, S.; Chatterjee, P.; Coleman, I.; Ha, G.; Ang, L.S.; Kohlbrenner, E.A.; Frank, S.B.; Nunez, T.A.; Salipante, S.J.; et al. Genomic attributes of homology-directed DNA repair deficiency in metastatic prostate cancer. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e152789. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Geyer, F.C.; Blecua, P.; Lee, J.Y.; Selenica, P.; Brown, D.N.; Pareja, F.; Lee, S.S.K.; Kumar, R.; Rivera, B.; et al. Homologous recombination DNA repair defects in PALB2-associated breast cancers. NPJ Breast Cancer 2019, 5, 23. [CrossRef]

- Preobrazhenskaya, E.V.; Shleykina, A.U.; Gorustovich, O.A.; Martianov, A.S.; Bizin, I.V.; Anisimova, E.I.; Sokolova, T.N.; Chuinyshena, S.A.; Kuligina, E.S.; Togo, A.V.; et al. Frequency and molecular characteristics of PALB2-associated cancers in Russian patients. Int J Cancer 2021, 148, 203-210. [CrossRef]

- Horak, P.; Weischenfeldt, J.; von Amsberg, G.; Beyer, B.; Schütte, A.; Uhrig, S.; Gieldon, L.; Klink, B.; Feuerbach, L.; Hübschmann, D.; et al. Response to olaparib in a PALB2 germline mutated prostate cancer and genetic events associated with resistance. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud 2019, 5, a003657. [CrossRef]

- Ciccone, M.A.; Adams, C.L.; Bowen, C.; Thakur, T.; Ricker, C.; Culver, J.O.; Maoz, A.; Melas, M.; Idos, G.E.; Jeyasekharan, A.D.; et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase induces synthetic lethality in BRIP1 deficient ovarian epithelial cells. Gynecol Oncol 2020, 159, 869-876. [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, E.S.; Isaacsson Velho, P.; Fu, W.; Wang, H.; Agarwal, N.; Sacristan Santos, V.; Maughan, B.L.; Pili, R.; Adra, N.; Sternberg, C.N.; et al. CDK12-Altered Prostate Cancer: Clinical Features and Therapeutic Outcomes to Standard Systemic Therapies; Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase Inhibitors; and PD-1 Inhibitors. JCO Precis Oncol 2020, 4, 370-381. [CrossRef]

- Mateo, J.; Porta, N.; Bianchini, D.; McGovern, U.; Elliott, T.; Jones, R.; Syndikus, I.; Ralph, C.; Jain, S.; Varughese, M.; et al. Olaparib in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with DNA repair gene aberrations (TOPARP-B): a multicentre; open-label; randomised; phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020, 21, 162-174. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Azad, A.A.; Carles, J.; Fay, A.P.; Matsubara, N.; Heinrich, D.; Szczylik, C.; De Giorgi, U.; Young Joung, J.; Fong, P.C.C.; et al. Talazoparib plus enzalutamide in men with first-line metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TALAPRO-2): a randomised; placebo-controlled; phase 3 trial. Lancet 2023, 402, 291-303. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.B.; Reimers, M.A.; Perera, C.; Abida, W.; Chou, J.; Feng, F.Y.; Antonarakis, E.S.; McKay, R.R.; Pachynski, R.K.; Zhang, J.; et al. Evaluating Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancers with Deleterious CDK12 Alterations in the Phase 2 IMPACT Trial. Clin Cancer Res 2024, 30, 3200-3210. [CrossRef]

- Tien, J.C.; Luo, J.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Mannan, R.; Mahapatra, S.; Shah, P.; et al. CDK12 loss drives prostate cancer progression; transcription-replication conflicts; and synthetic lethality with paralog CDK13. Cell Rep Med 2024, 5, 101758. [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.; Persse, T.; Coleman, I.; Bankhead, A. 3rd; Li, D.; De-Sarkar, N.; Wilson, D.; Rudoy, D.; Vashisth, M.; Galipeau, P.; et al. Molecular consequences of acute versus chronic CDK12 loss in prostate carcinoma nominates distinct therapeutic strategies. bioRxiv [Preprint] 2025, May 19:2024.07.16.603734. [CrossRef]

- Decker, B.; Karyadi, D.M.; Davis, B.W.; Karlins, E.; Tillmans, L.S.; Stanford, J.L.; Thibodeau, S.N.; Ostrander, E.A. Biallelic BRCA2 Mutations Shape the Somatic Mutational Landscape of Aggressive Prostate Tumors. Am J Hum Genet 2016, 98, 818-829. [CrossRef]

- Barnett, E.S.; Schultz, N.; Stopsack, K.H.; Lam, E.T.; Arfe, A.; Lee, J.; Zhao, J.L.; Schonhoft, J.D.; Carbone, E.A.; Keegan, N.M.; et al. Analysis of BRCA2 Copy Number Loss and Genomic Instability in Circulating Tumor Cells from Patients with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol 2023, 83, 112-120. [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu, S.; Brown, J.B.; Yamaguchi, K.; Hamanishi, J.; Yamanoi, K.; Takaya, H.; Kaneyasu, T.; Mori, S.; Mandai, M.; Matsumura, N. Utility of Homologous Recombination Deficiency Biomarkers Across Cancer Types. JCO Precis Oncol 2022, 6, e2200085. [CrossRef]

- Van der Auwera, G.A.; Carneiro, M.O.; Hartl, C.; Poplin, R.; Del Angel, G.; Levy-Moonshine, A.; Jordan, T.; Shakir, K.; Roazen, D.; Thibault, J.; et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 2013, 43, 11.10.1-11.10.33. [CrossRef]

- Timms, K.M.; Abkevich, V.; Hughes, E.; Neff, C.; Reid, J.; Morris, B.; Kalva, S.; Potter, J.; Tran, T.V.; Chen, J.; et al. Association of BRCA1/2 defects with genomic scores predictive of DNA damage repair deficiency among breast cancer subtypes. Breast Cancer Res 2014, 16, 475. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).