1. Introduction

Operating effectively in dynamic and cluttered underwater environments requires vehicles capable of agile, three-dimensional maneuvering. Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUV

S) have made advances in range and endurance, but they lack the fine, high-speed maneuverability of biological swimmers, limiting their use in complex settings like nearshore currents and riverine habitats [

1,

2]. Current UUVs are functionally constrained by their propulsion methods. While multi-thruster vehicles offer precision control at low speeds, they often require bulky hulls and are limited by fixed-axis thrust lines. Conversely, streamlined, propeller-driven bodies are efficient for long-range travel but lack the ability to rapidly modulate or reorient thrust for complex turns or evasive maneuvers [

3]. Overcoming these limitations necessitates a propulsion system capable of generating and redirecting forces dynamically in three dimensions [

4].

Biological swimmers demonstrate that reorientable propulsors are key to generating the dynamic, three-dimensional forces needed for agile maneuvering. A wide range of taxa exploit this principle: fish employ undulatory fin motions [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]; rays and turtles use flapping appendages for lift-based propulsion [

10,

11,

12]; and cephalopods generate thrust through pulsed jet flows [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Among aquatic vertebrates, the California sea lion (

Zalophus californianus) provides a highly relevant model. Sea lions use foreflippers to execute a characteristic three-phase stroke that facilitates powerful propulsion and enables exceptional agility, demonstrated by minimum turning radii as small as 0.16 body lengths and turn rates exceeding 600 deg s⁻¹ [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. While the sea lion flipper morphology and stroke kinematics are well-described, the specific influence of systematic kinematic variations on the instantaneous, time-varying magnitude and direction of the propulsive forces remains poorly quantified [

Figure 1].

The objective of this work is to characterize the time-varying thrust and lift produced by a bio-robotic foreflipper executing the California sea lion's characteristic propulsive stroke, with the goal of identifying the mechanisms that enable agile force modulation. This study addresses a key knowledge gap by experimentally resolving the complete, time-varying force trajectories over an entire propulsive cycle using a bio-robotic model of the foreflipper. Variations in principal stroke kinematics, including flipper rotation about its long axis (twist), forward and backward motion (sweep), and the degree of overlap between stroke phases, are systematically quantified to determine how these parameters influence the instantaneous generation and reorientation of propulsive forces [

Figure 2,

Figure 3]. The results provide fundamental hydrodynamic data that are essential for the design and control of agile, bio-inspired underwater systems capable of complex three-dimensional maneuvers.

Prior investigations have established the feasibility of sea-lion-inspired propulsion, but have primarily relied on simulated, phase-averaged, or studies of the fluidics around the fore-flippers [

22]. Subsequent work began to probe the propulsive mechanisms, with many studies asserting that thrust production, especially during the power phase of the stroke is mainly a lift-based phenomenon, produced by vortex-mediated mechanisms and angle-of-attack effects [

23]. More recent studies have built upon this foundation, using robotic models or CFD simulations analyze phase-specific propulsion, often focusing on these hydrodynamic, lift-based interpretations [

24,

25]. These analyses identified vortex structures and pressure differentials consistent with lift-based effects, but they did not provide a time-resolved, systematic mapping of how specific kinematic parameters translate to measurable forces throughout a complete stroke. The present study extends this foundation by providing the first systematic, experimentally measured mapping between kinematic parameters and the resulting time-varying propulsive forces.

This paper first details the design of the bio-robotic foreflipper, the experimental environment, and the kinematic parameters used to model the propulsive stroke. It then presents an analysis of the baseline force trajectories for each stroke phase. The detailed results follow, illustrating how systematic variations in key kinematics (twist, sweep, and phase overlap) modulate the instantaneous forces. These results are discussed in the context of propulsive mechanisms and bio-inspired design, followed by a conclusion that summarizes the main contributions.

4. Discussion

This study characterized the time-varying thrust and lift produced by a bio-robotic sea lion foreflipper to identify the kinematic mechanisms that control force generation and reorientation. The results provide a systematic, time-resolved mapping between flipper kinematics and the instantaneous propulsive force vector. The findings show that within the tested inertial flow regime (Re≈104−105), the foreflipper operates as a hybrid propulsion system, producing powerful thrust and lift forces in a single stroke, and its forces can be effectively controlled by geometric and temporal kinematics. This study provides a foundational map for these control mechanisms.

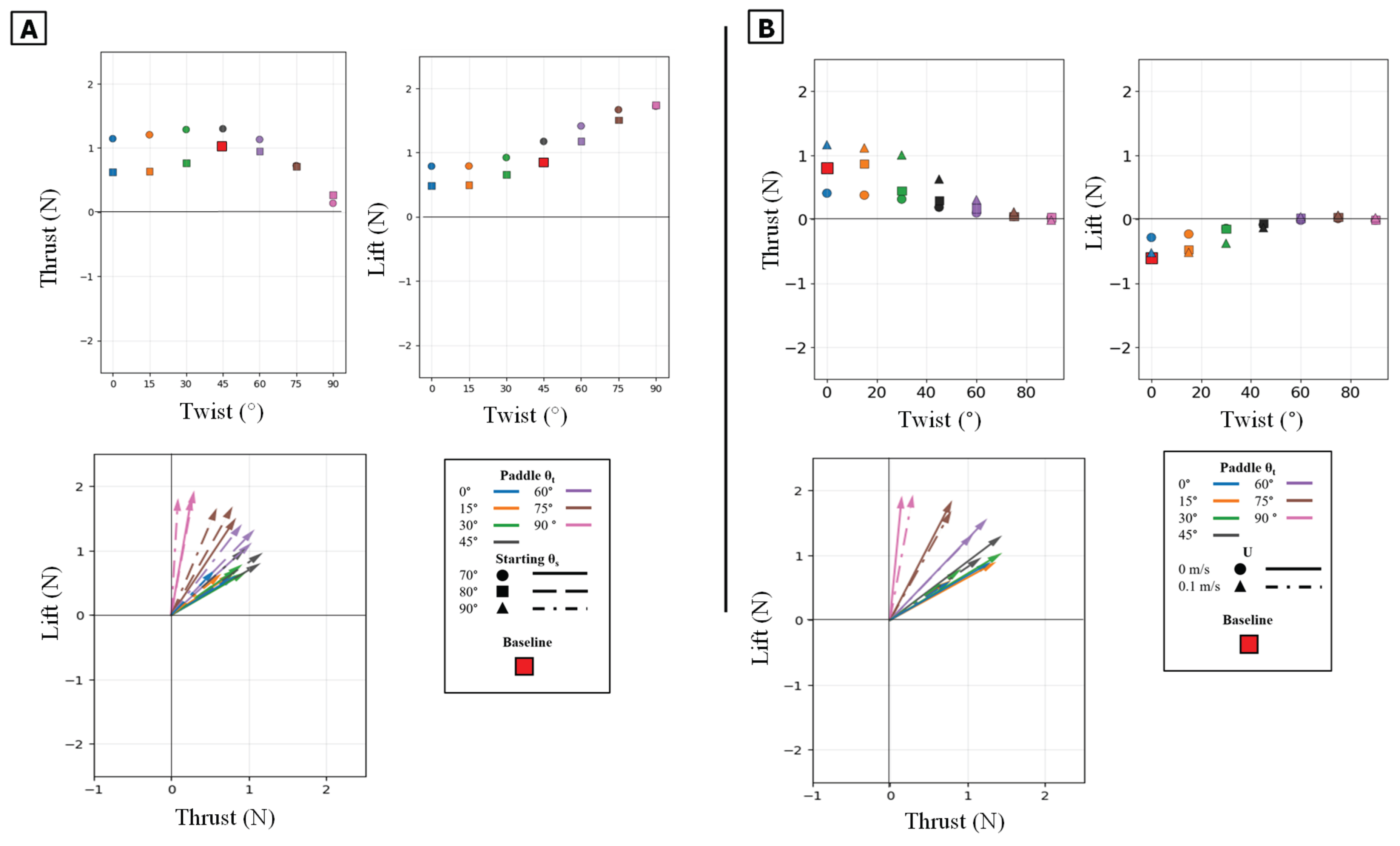

A central finding of this work is the robust, high-angle thrust optimum of the power phase. The results show mean thrust is maximized in a broad range between 0° and 45° (peaking at 45° in the isolated stroke, as shown in

Figure 11), and then drops off sharply at higher angles. This is a critical result because many propulsive-foil analyses are interpreted through a lift-based framework, which would predict an optimal thrust at a low, attached-flow angle of attack (e.g., AoA ≈ 10−15°) [

23,

25]. In contrast, a robust, high-angle optimal range is highly characteristic of a drag-based or post-stall system, where the goal is to orient a surface to maximize the propulsive component of a large pressure-drag force. While the experiments, which did not measure the flow field, cannot definitively rule out lift-based effects, the force data—particularly this high-angle, robust optimum and its insensitivity to oncoming flow—are highly consistent with a system dominated by geometric momentum redirection and impulse timing.

This emphasis on geometric mechanisms is also a direct consequence of the model's simplified design. The biological flipper possesses a high aspect ratio (4.1-7.9), spanwise flexibility, and chordwise taper, all of which are features that can enhance circulation-based lift. The model, by design, employed a low aspect ratio (2.7), rectangular planform, and a single compliant hinge. These design choices deliberately simplify the hydrodynamic system, resulting in a device that functions as a simplified "paddle," emphasizing pressure-driven thrust. This makes the model highly appropriate for isolating and studying the foundational geometric basis of propulsion, though not for replicating the full, flexible, high-aspect-ratio performance of the biological foreflipper. The findings should therefore be viewed as identifying the foundational geometric mechanism that likely acts in concert with lift-based effects in the real animal.

The experiments also demonstrate how geometric and temporal control of kinematics can generate a predictable range of thrust and lift vectors. The power phase twist angle governs the direction of the resultant force vector, the paddle phase twist sets thrust magnitude by adjusting the flipper’s presented area, and temporal phase overlap regulates the overall impulse by merging sequential force peaks. Together, these parameters form a controllable framework for agile propulsion. This map is not intended to replicate sea lion performance directly but to show how simple, geometry-based rules can produce reliable force reorientation in underwater robots operating at similar Reynolds numbers.

The dual-phase structure of the stroke highlights a hybrid strategy for combining versatility and robustness. The power phase acts as a steering stroke that reorients the propulsive vector, while the paddle phase provides strong, flow-insensitive thrust. This division of labor allows propulsion that is both adaptable and consistent, a useful design principle for robotic vehicles. This behavior establishes the baseline control logic for the geometric component of the stroke, upon which more complex, lift-augmented mechanisms may be layered in the biological system.

Several limitations define the scope of these findings. The simplified geometry and slower stroke frequency (T = 2.25 s), which lowers the flipper's self-induced velocities, are the primary constraints. The simplified model, while useful for isolating mechanisms, means these findings cannot be used to describe the full dynamics of the flexible, high-aspect-ratio biological flipper. The study provides a map of the geometric component; it does not quantify the lift-based component. Future work should explore how this geometric baseline couples with lift-based dynamics. Increasing stroke frequency, incorporating distributed flexibility, and testing with full planform geometry will help determine how biological flippers integrate these two propulsive mechanisms across scales.

In summary, the present results identify geometric momentum redirection and impulse timing as dominant propulsive mechanisms in this simplified, low-aspect-ratio robotic model. These mechanisms describe a fundamental geometric control of thrust and lift that likely provides the structural foundation upon which circulation-based lift develops at biological scale. The study thus complements, rather than contradicts, previous research that has focused on lift-based interpretations by revealing and systematically mapping the foundational geometric origins of the stroke.

5. Conclusions

This study experimentally quantified the time-varying thrust and lift generated by a bio-robotic sea lion foreflipper to identify how kinematic inputs—specifically twist, sweep, and phase overlap—govern instantaneous propulsive forces. The analysis revealed that the foreflipper stroke operates as a highly adaptable, hybrid propulsion system composed of two hydrodynamically distinct components. The power phase functions as a versatile force-vectoring stroke, where twist angle partitions the resultant force between thrust, which exhibits a broad, robust optimum peaking near 45°, and lift, which increases toward 90°. This high-angle, robust optimum remained consistent across flow conditions, indicating a geometric control mechanism rather than sensitivity to oncoming flow. The paddle phase acts as a robust, geometrically-driven thrust generator, where force is maximized at 0° twist, when the flippers face is broadest to the direction of motion and remains insensitive to external flow.

When combined, temporal phase overlap merges the individual thrust peaks into a single, amplified impulse, while the power-phase twist angle governs the overall direction of the resultant force vector. These findings describe a coherent control framework in which twist governs direction, presented area governs magnitude, and overlap governs total impulse.

This entire control map, particularly the high-angle, robust optimum, is highly consistent with propulsion dominated by geometric momentum redirection and impulse timing, in contrast to the low-angle optimums typical of lift-based foils. These findings, enabled by a simplified, low-aspect-ratio model designed to isolate these effects, define the foundational geometric basis of the stroke. This study thus complements, rather than contradicts, research focused on lift-based interpretations by systematically mapping a mechanism that likely acts in concert with circulation-based effects in the biological animal. This framework provides a practical and scalable foundation for the design and control of agile, bio-inspired underwater vehicles.

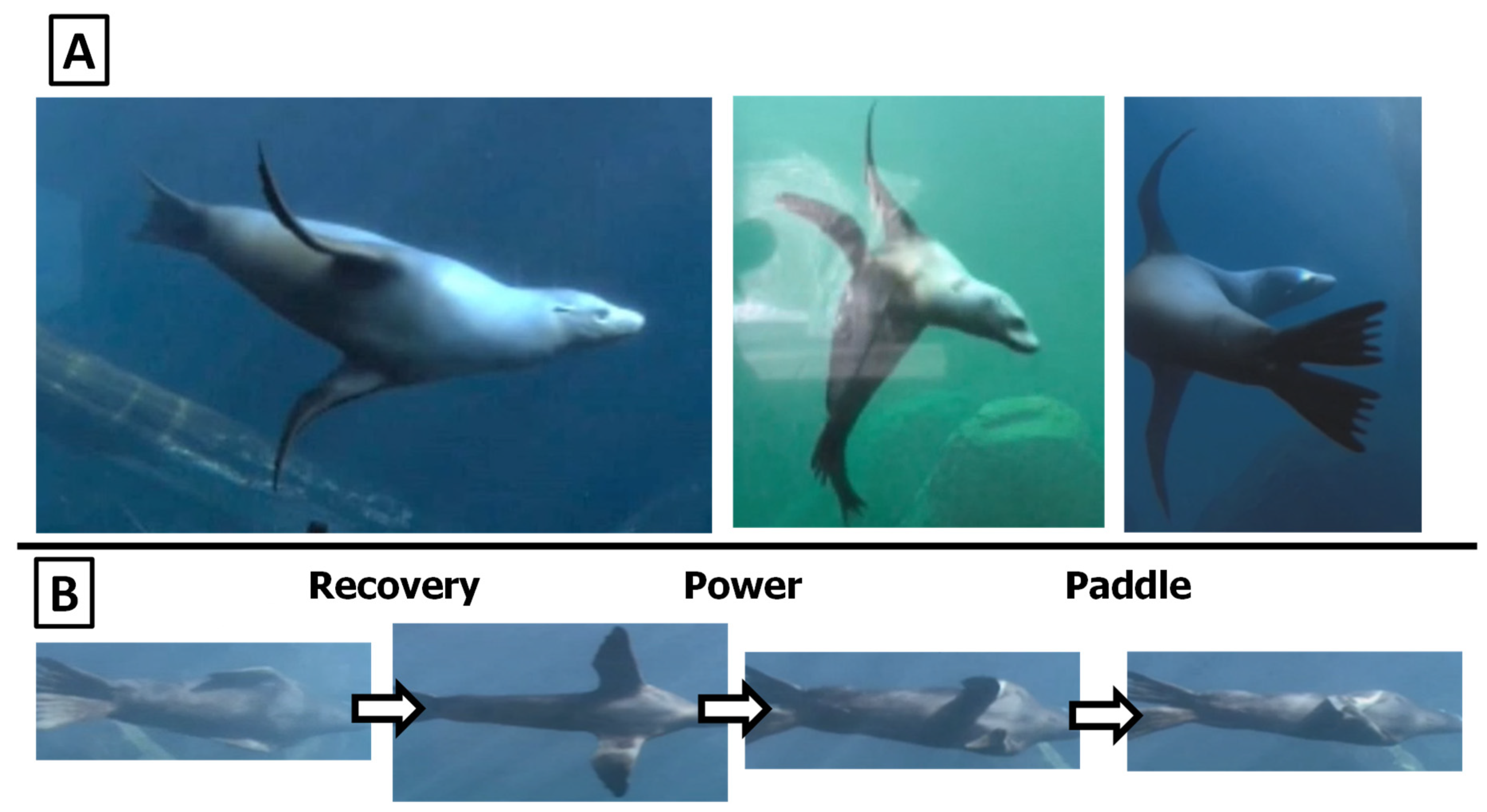

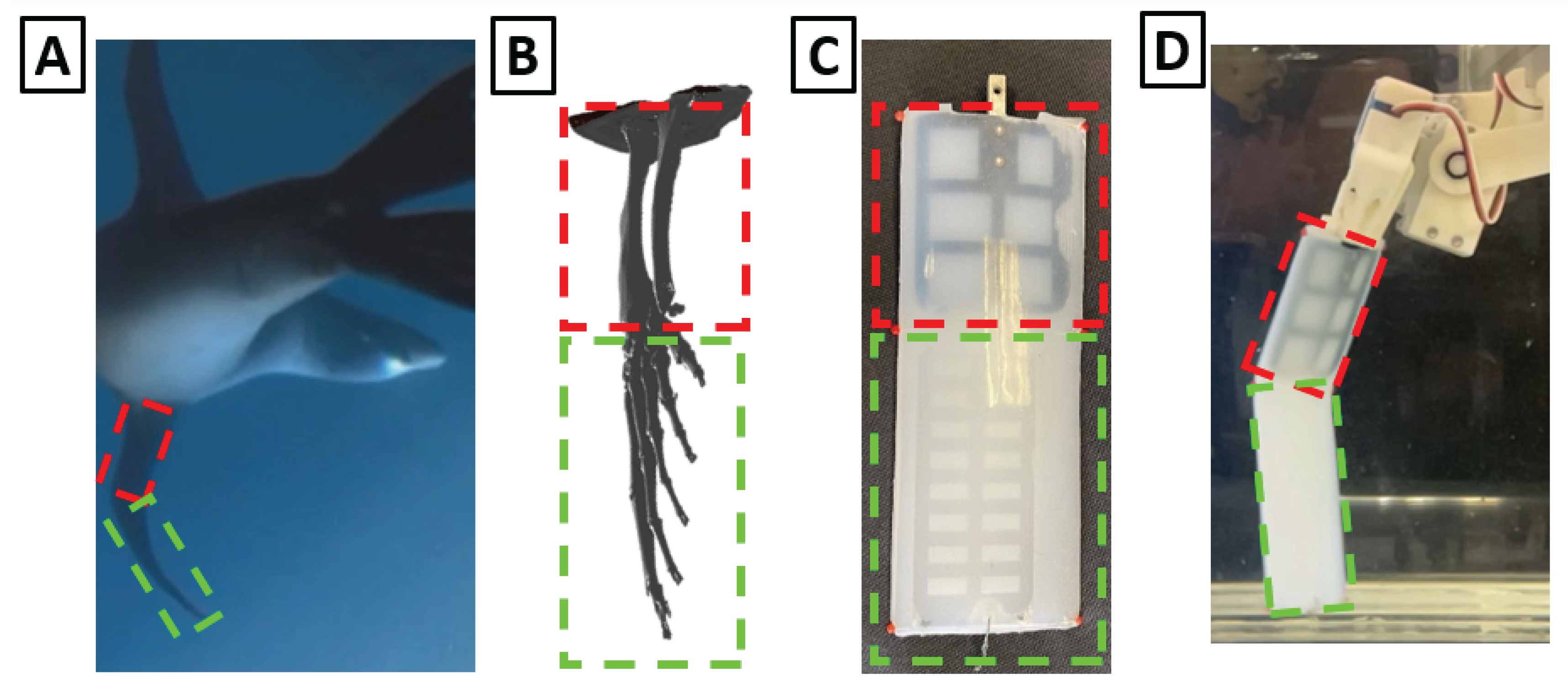

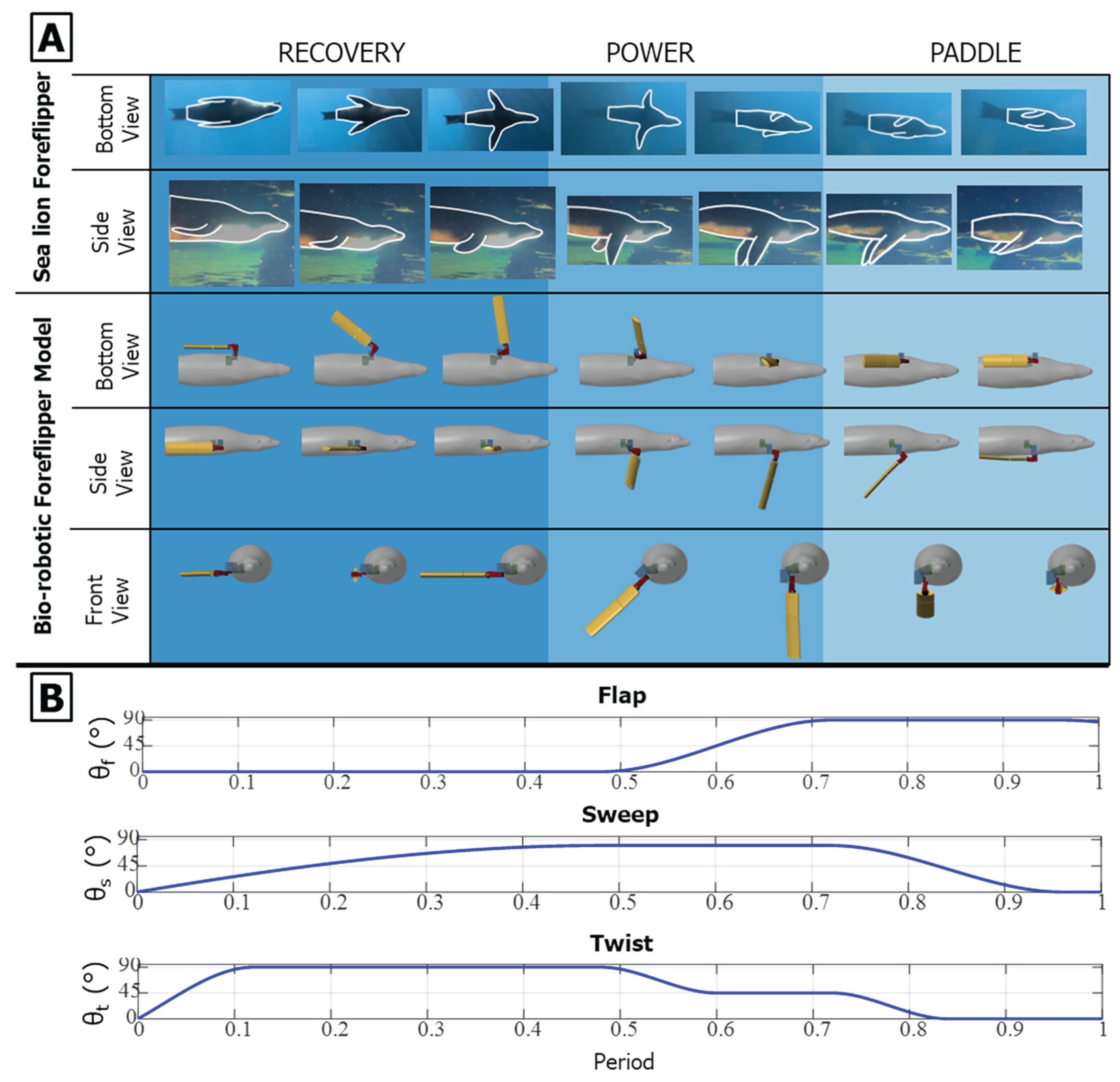

Figure 1.

California sea lion swimming and characteristic propulsive stroke. (A) Sea lion maneuvering underwater using its foreflippers, hind flippers, and body for agile control. (B) Sequential frames from underwater video showing the three phases of the characteristic foreflipper stroke: Recovery, during which the flippers extend laterally and anteriorly away from the body; Power, where the flippers move downward and medially to generate thrust; and Paddle, as the flippers are pulled posteriorly toward the body to complete the stroke cycle and reset for the next recovery phase.

Figure 1.

California sea lion swimming and characteristic propulsive stroke. (A) Sea lion maneuvering underwater using its foreflippers, hind flippers, and body for agile control. (B) Sequential frames from underwater video showing the three phases of the characteristic foreflipper stroke: Recovery, during which the flippers extend laterally and anteriorly away from the body; Power, where the flippers move downward and medially to generate thrust; and Paddle, as the flippers are pulled posteriorly toward the body to complete the stroke cycle and reset for the next recovery phase.

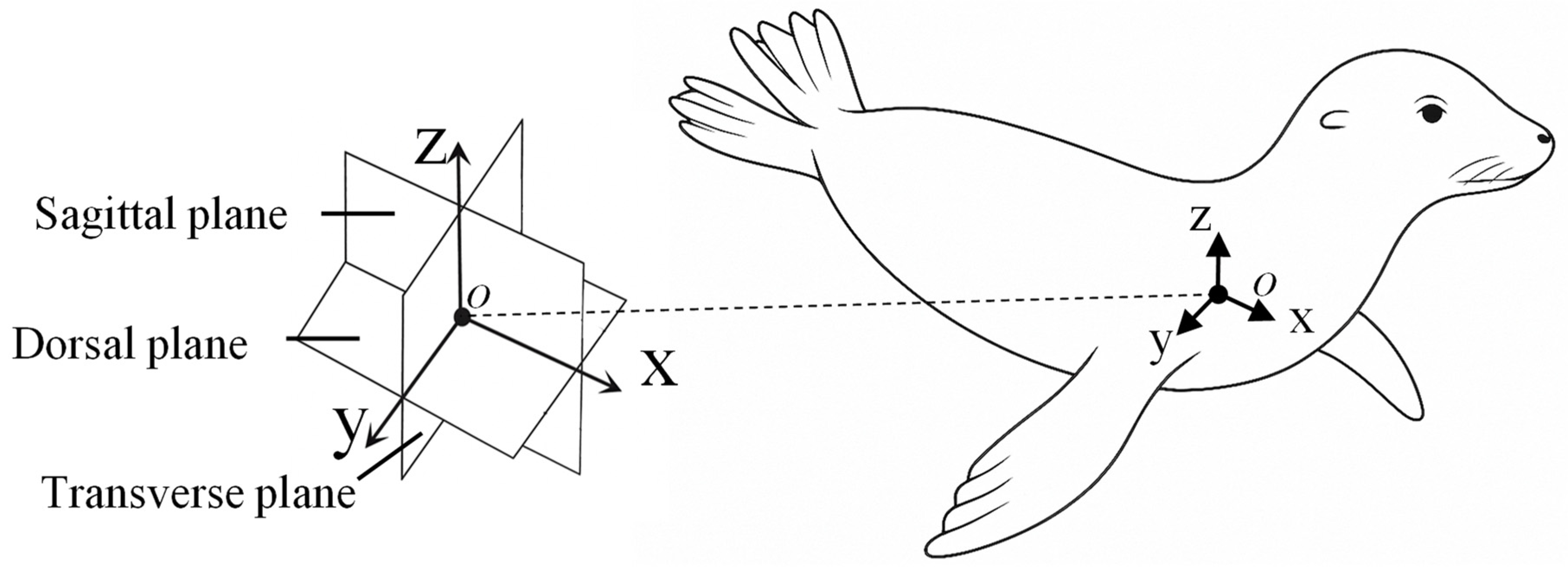

Figure 2.

Anatomical coordinate system of the California sea lion. Body-fixed coordinate frame and associated anatomical planes used to describe foreflipper motion. The x-axis is oriented anteroposteriorly along the body midline toward the head, the y-axis extends laterally, and the z-axis extends dorsoventrally. These axes define the Sagittal (x−z), Transverse (y−z), and Dorsal (x−y) planes, which respectively separate the left and right sides, dorsal and ventral regions, and anterior and posterior portions of the body.

Figure 2.

Anatomical coordinate system of the California sea lion. Body-fixed coordinate frame and associated anatomical planes used to describe foreflipper motion. The x-axis is oriented anteroposteriorly along the body midline toward the head, the y-axis extends laterally, and the z-axis extends dorsoventrally. These axes define the Sagittal (x−z), Transverse (y−z), and Dorsal (x−y) planes, which respectively separate the left and right sides, dorsal and ventral regions, and anterior and posterior portions of the body.

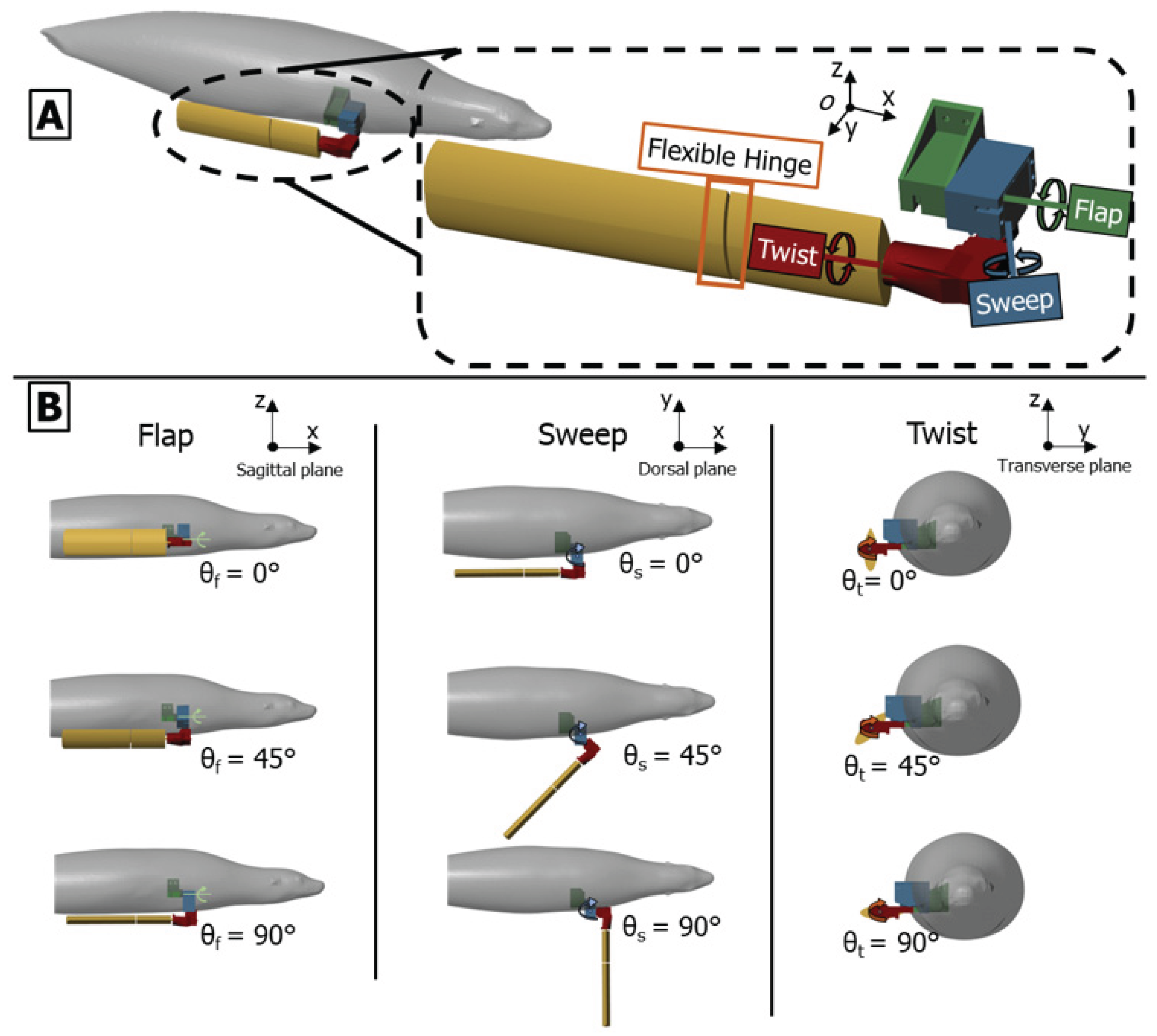

Figure 3.

Bio-robotic foreflipper coordinate system and actuation scheme. (A) The bio-robotic foreflipper replicates sea lion forelimb motion through three serially arranged actuators (flap, sweep, and twist). A flexible hinge at the wrist introduces passive bending representative of the biological joint (B) Representative actuator motions showing the range of rotation for each axis: flap angle (θf), sweep angle (θs), and twist angle (θt). The zero position aligns the flipper parallel to the body flank with the leading edge downward. Increasing actuator angles illustrate the independent and combined rotations that generate the full spatial envelope of sea lion foreflipper movement.

Figure 3.

Bio-robotic foreflipper coordinate system and actuation scheme. (A) The bio-robotic foreflipper replicates sea lion forelimb motion through three serially arranged actuators (flap, sweep, and twist). A flexible hinge at the wrist introduces passive bending representative of the biological joint (B) Representative actuator motions showing the range of rotation for each axis: flap angle (θf), sweep angle (θs), and twist angle (θt). The zero position aligns the flipper parallel to the body flank with the leading edge downward. Increasing actuator angles illustrate the independent and combined rotations that generate the full spatial envelope of sea lion foreflipper movement.

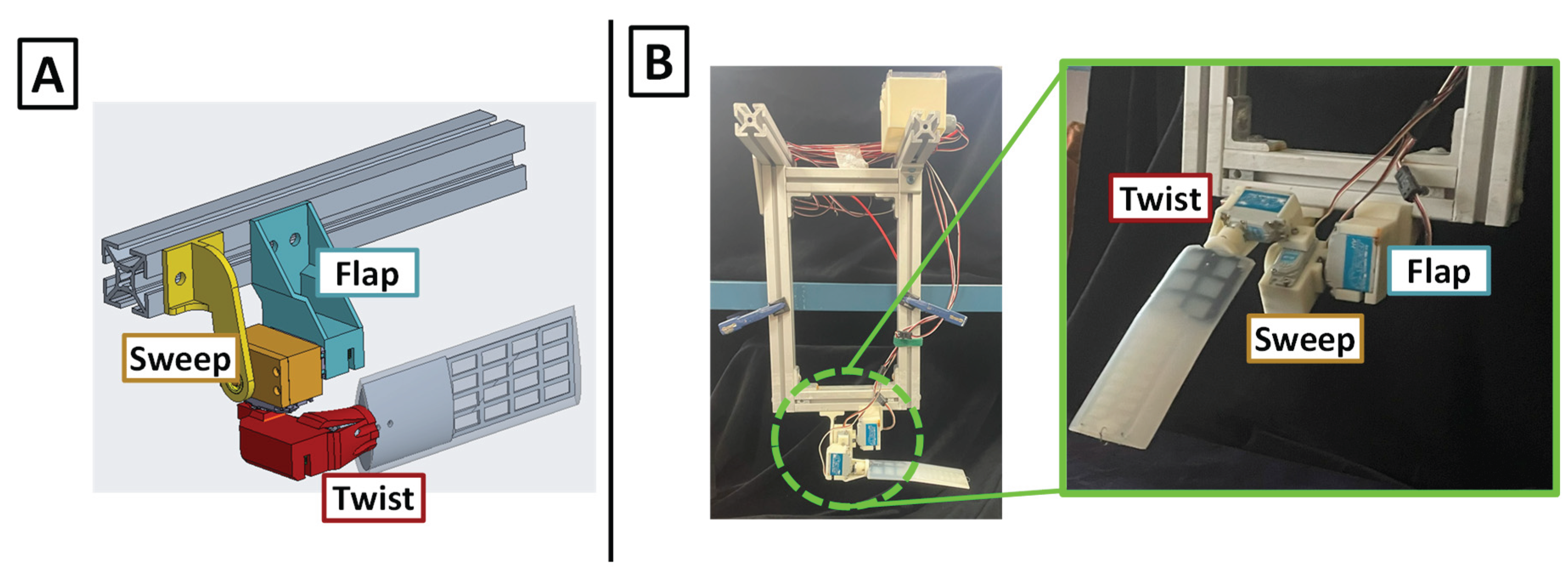

Figure 4.

Bio-robotic Single Flipper Robot. (A) CAD model of the single flipper robot with the actuatable axes labeled (B) Full bio-robotic single flipper robot with (Left) support structure, control box, and actuators and (Right) a closer view of the flipper and actuator set-up.

Figure 4.

Bio-robotic Single Flipper Robot. (A) CAD model of the single flipper robot with the actuatable axes labeled (B) Full bio-robotic single flipper robot with (Left) support structure, control box, and actuators and (Right) a closer view of the flipper and actuator set-up.

Figure 5.

Design Of Engineered Sea Lion Flipper. (A) Foreflipper bending during sea lion swimming (B) 3D model of sea lion foreflipper showing bone structure (C) Final design of foreflipper model, highlighting the two rigid sections cast in flexible silicon (D) Foreflipper model bending during actuation.

Figure 5.

Design Of Engineered Sea Lion Flipper. (A) Foreflipper bending during sea lion swimming (B) 3D model of sea lion foreflipper showing bone structure (C) Final design of foreflipper model, highlighting the two rigid sections cast in flexible silicon (D) Foreflipper model bending during actuation.

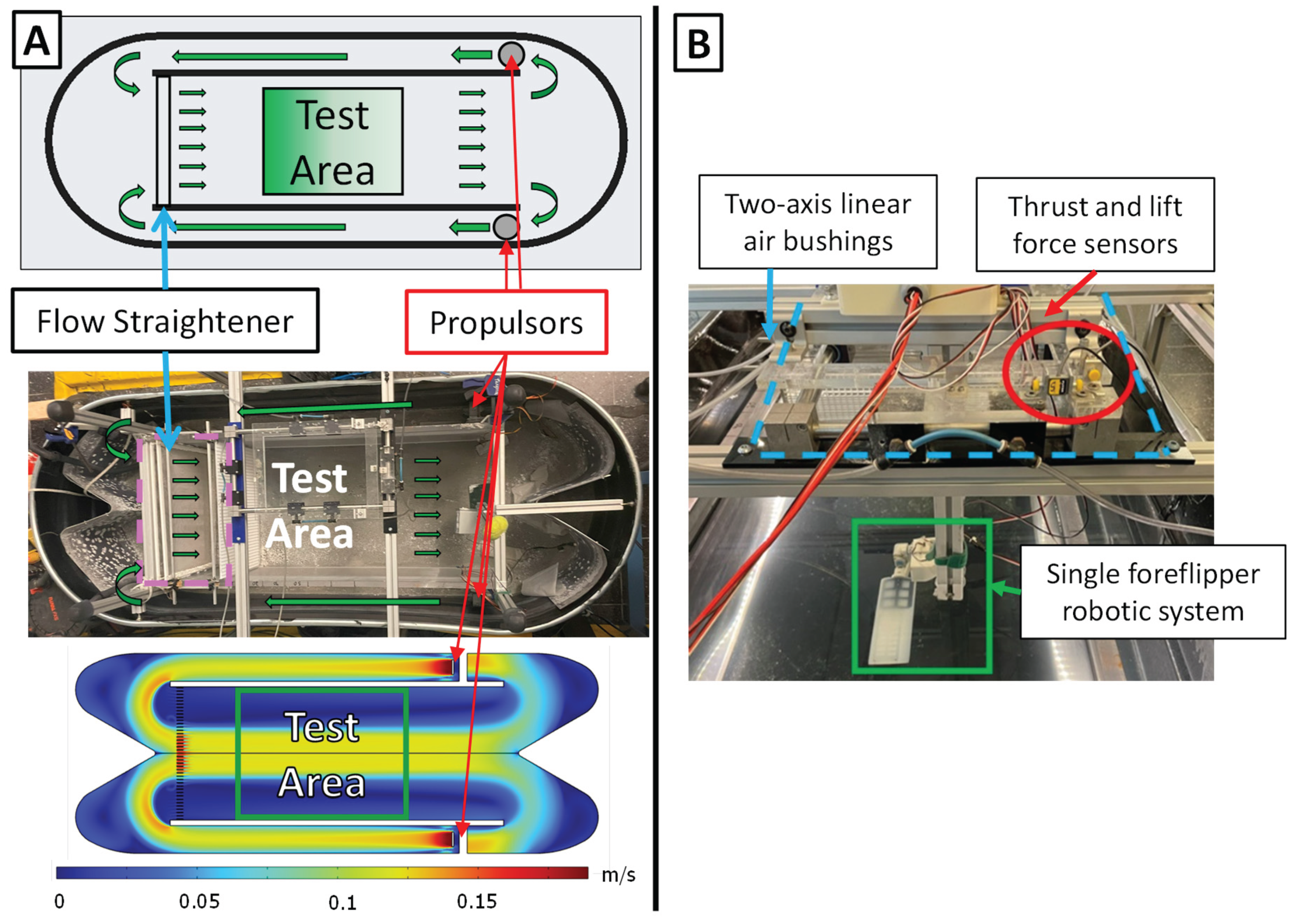

Figure 6.

Experimental test environment. (A) Schematic, photograph, and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation of the circulating flow tank used for experiments. Water is driven by dual propulsors and passes through three flow straighteners before entering the central test area. The CFD velocity map confirms uniform flow distribution and stable velocity profiles within the test region. (B) Experimental apparatus showing the suspended measurement system, including two-axis linear air bushings for low-friction translation, thrust and lift force sensors for load measurement, and the single bio-robotic foreflipper mounted within the test area.

Figure 6.

Experimental test environment. (A) Schematic, photograph, and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation of the circulating flow tank used for experiments. Water is driven by dual propulsors and passes through three flow straighteners before entering the central test area. The CFD velocity map confirms uniform flow distribution and stable velocity profiles within the test region. (B) Experimental apparatus showing the suspended measurement system, including two-axis linear air bushings for low-friction translation, thrust and lift force sensors for load measurement, and the single bio-robotic foreflipper mounted within the test area.

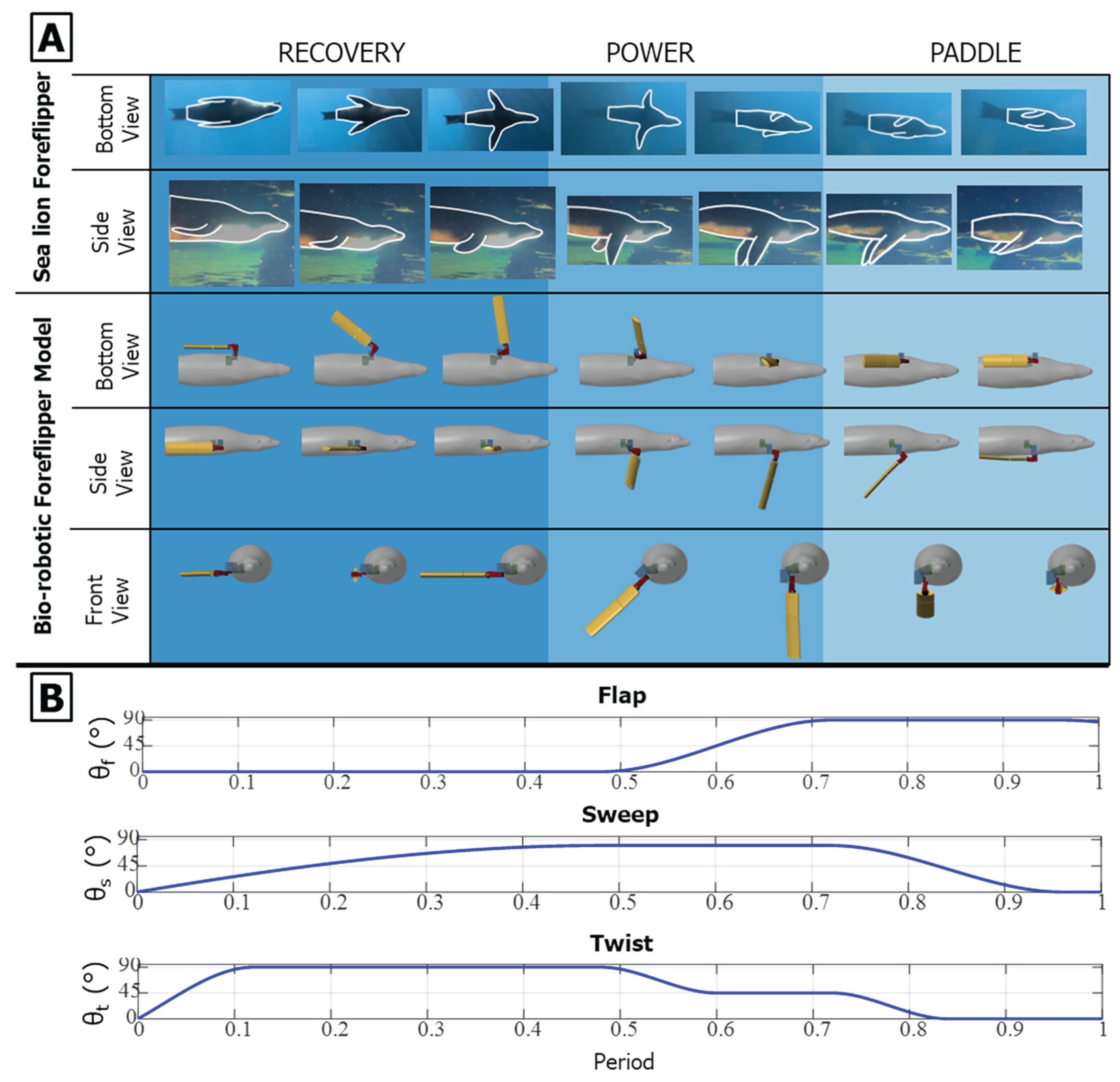

Figure 7.

Characteristic foreflipper stroke of the California sea lion and corresponding robotic implementation. (A) Sequential views of the biological and bio-robotic foreflipper illustrating the three primary phases of the characteristic propulsive stroke: Recovery, where the flipper moves upward and outward to a laterally extended position minimizing drag; Power, characterized by a strong downward and rearward motion that generates thrust; and Paddle, where the flipper moves ventrally toward the body while maintaining lift before returning to the streamlined position. The bio-robotic foreflipper reproduces these coordinated motions through flap (θf), sweep (θs), and twist (θt) (B) Parameterized joint trajectories for flap, sweep, and twist angles across one full stroke cycle, modeled using a piecewise cubic Hermite interpolating polynomial (PCHIP) fit to biological kinematic data. Together, these actuator profiles recreate the continuous, nonplanar motion and characteristic feathering of the sea lion’s foreflipper during propulsion.

Figure 7.

Characteristic foreflipper stroke of the California sea lion and corresponding robotic implementation. (A) Sequential views of the biological and bio-robotic foreflipper illustrating the three primary phases of the characteristic propulsive stroke: Recovery, where the flipper moves upward and outward to a laterally extended position minimizing drag; Power, characterized by a strong downward and rearward motion that generates thrust; and Paddle, where the flipper moves ventrally toward the body while maintaining lift before returning to the streamlined position. The bio-robotic foreflipper reproduces these coordinated motions through flap (θf), sweep (θs), and twist (θt) (B) Parameterized joint trajectories for flap, sweep, and twist angles across one full stroke cycle, modeled using a piecewise cubic Hermite interpolating polynomial (PCHIP) fit to biological kinematic data. Together, these actuator profiles recreate the continuous, nonplanar motion and characteristic feathering of the sea lion’s foreflipper during propulsion.

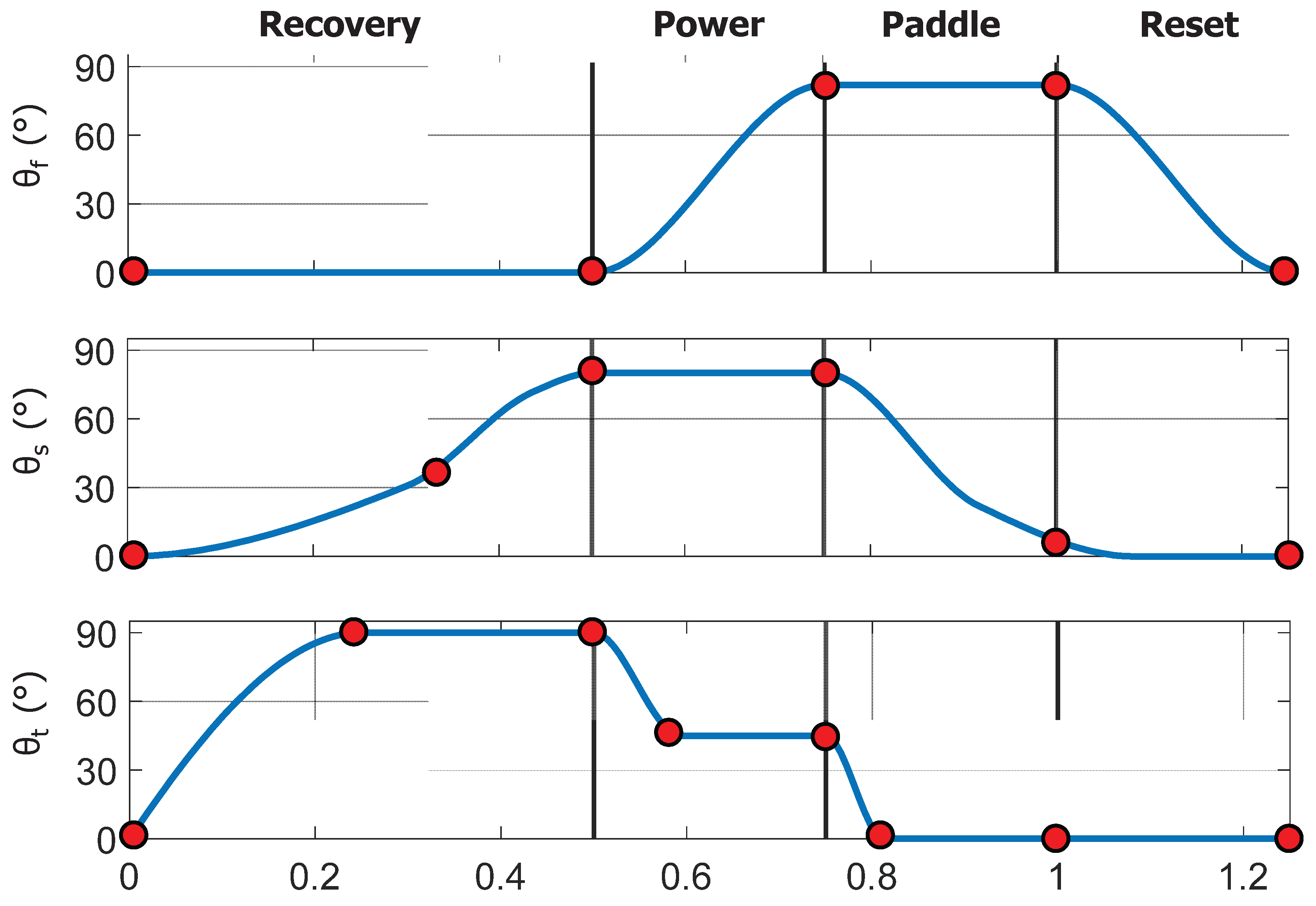

Figure 8.

PCHIP spline representation of foreflipper kinematics. Parameterized flap (θf), sweep (θs), and twist (θt) angles over one complete stroke cycle, divided into the Recovery, Power, Paddle, and Reset phases. Red circles indicate control points defining the piecewise cubic Hermite interpolating polynomial (PCHIP) splines used to generate smooth, shape-preserving joint trajectories without overshoot. These control points can be adjusted to modify amplitude, timing, and phase relationships between the three motions, enabling controlled variation of stroke kinematics in experiments while faithfully reproducing the characteristic sea lion stroke observed in the animal.

Figure 8.

PCHIP spline representation of foreflipper kinematics. Parameterized flap (θf), sweep (θs), and twist (θt) angles over one complete stroke cycle, divided into the Recovery, Power, Paddle, and Reset phases. Red circles indicate control points defining the piecewise cubic Hermite interpolating polynomial (PCHIP) splines used to generate smooth, shape-preserving joint trajectories without overshoot. These control points can be adjusted to modify amplitude, timing, and phase relationships between the three motions, enabling controlled variation of stroke kinematics in experiments while faithfully reproducing the characteristic sea lion stroke observed in the animal.

Figure 9.

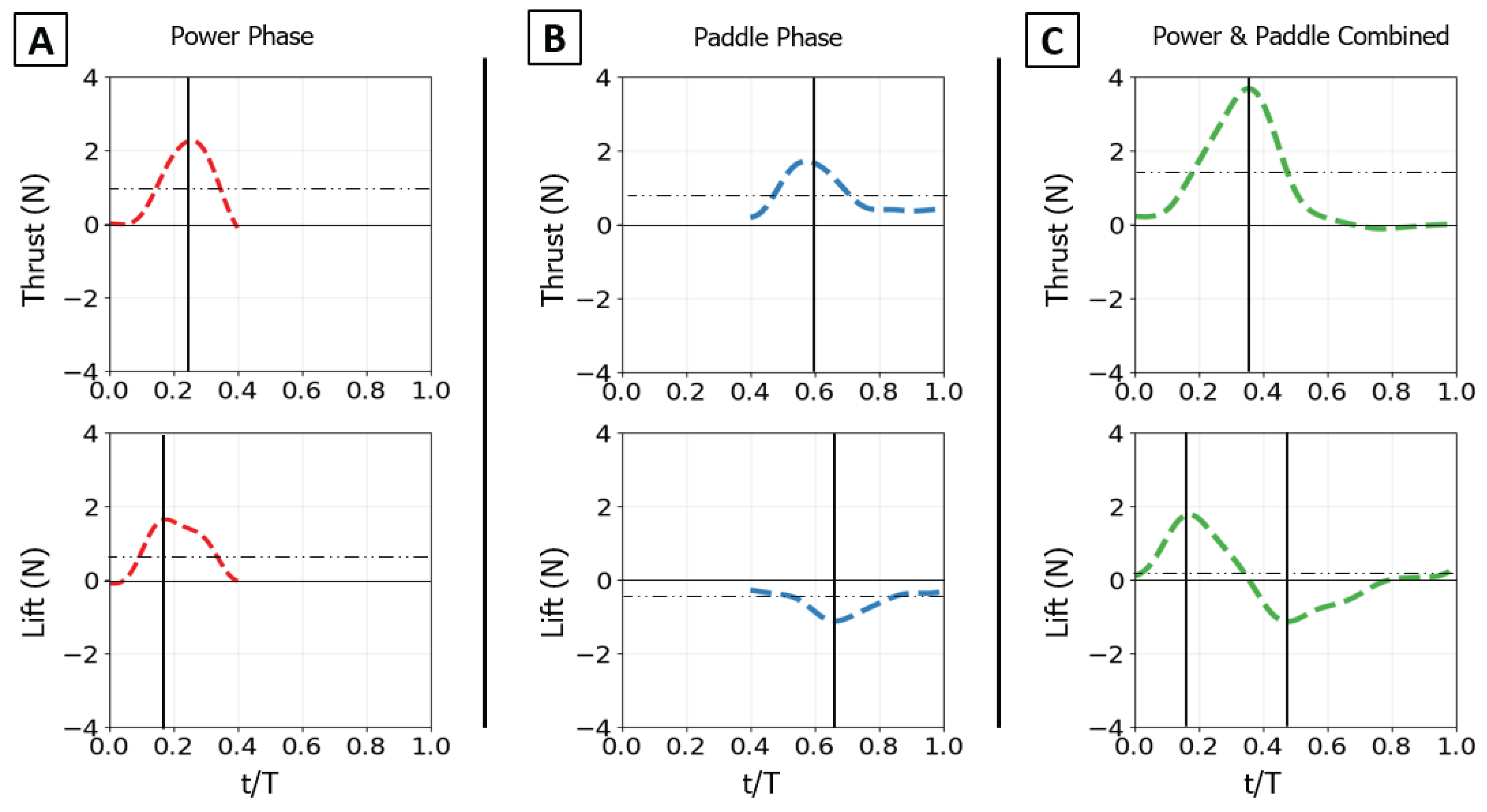

Time-varying thrust and lift traces for the baseline propulsive strokes. Thrust (top row) and lift (bottom row) are shown for: (A) the isolated power phase, (B) the isolated paddle phase, and (C) the combined power-paddle stroke. The horizontal axis is nondimensional time (t/T), and the vertical axis is force (N). For each trace, the horizontal dotted line indicates the mean force over the phase, and the vertical solid line marks the timing of the peak force.

Figure 9.

Time-varying thrust and lift traces for the baseline propulsive strokes. Thrust (top row) and lift (bottom row) are shown for: (A) the isolated power phase, (B) the isolated paddle phase, and (C) the combined power-paddle stroke. The horizontal axis is nondimensional time (t/T), and the vertical axis is force (N). For each trace, the horizontal dotted line indicates the mean force over the phase, and the vertical solid line marks the timing of the peak force.

Figure 10.

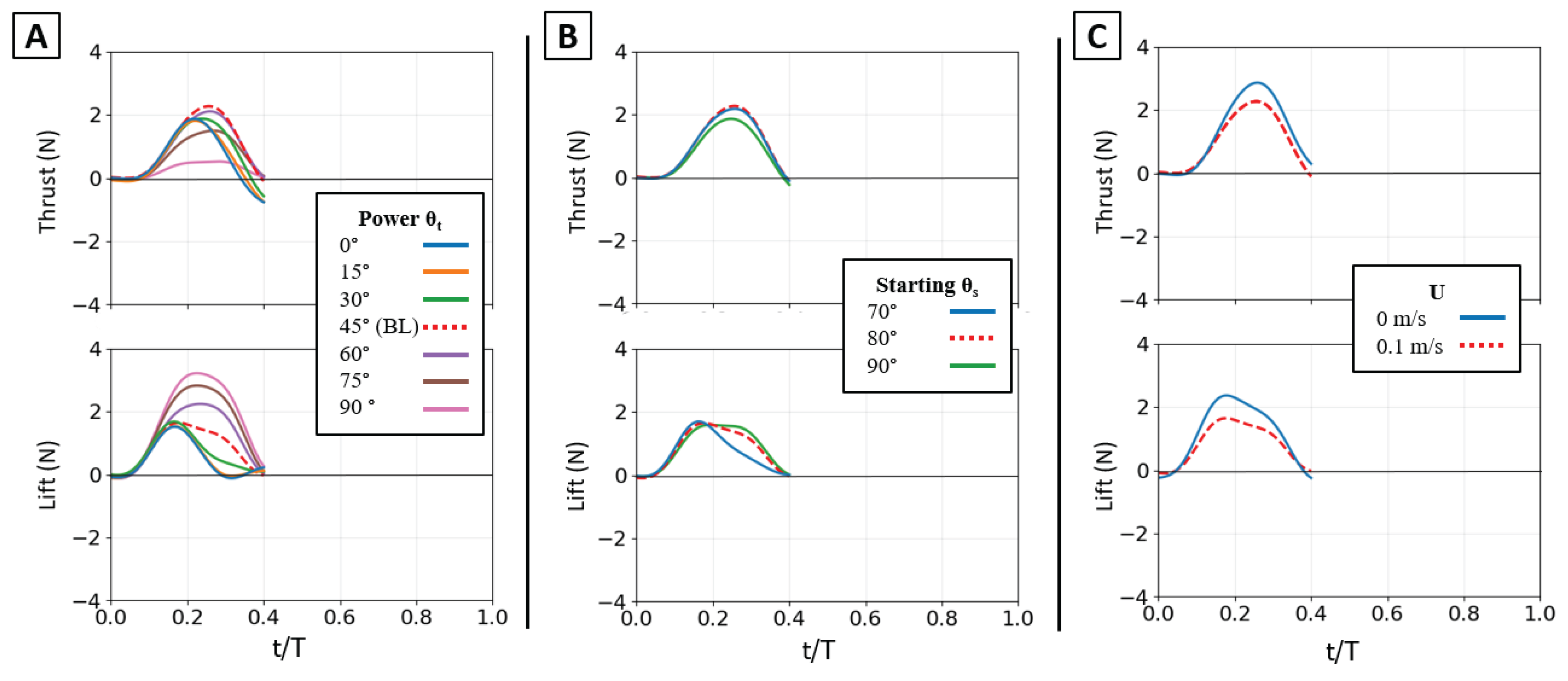

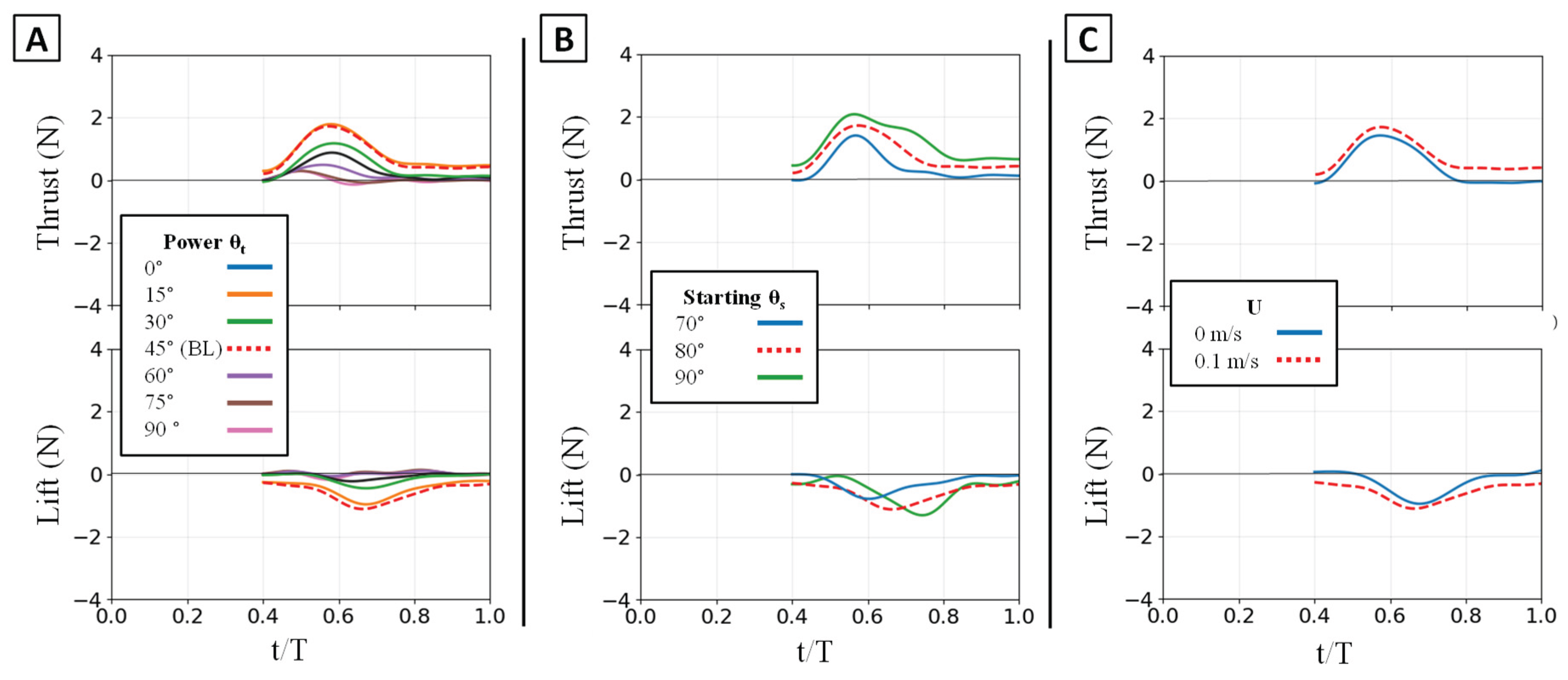

Effect of kinematic variations on isolated power phase forces. Time-varying thrust (top row) and lift (bottom row) traces are shown for manipulations of the baseline stroke. (A) Effect of varying the flipper twist angle (θt) from 0° to 90°. (B) Effect of varying the starting sweep angle (θs) from 70° to 90°. (C) Effect of the presence of oncoming flow (U). The horizontal axis is nondimensional time (t/T), and the vertical axis is force (N). The baseline (BL) condition is highlighted in each panel for reference.

Figure 10.

Effect of kinematic variations on isolated power phase forces. Time-varying thrust (top row) and lift (bottom row) traces are shown for manipulations of the baseline stroke. (A) Effect of varying the flipper twist angle (θt) from 0° to 90°. (B) Effect of varying the starting sweep angle (θs) from 70° to 90°. (C) Effect of the presence of oncoming flow (U). The horizontal axis is nondimensional time (t/T), and the vertical axis is force (N). The baseline (BL) condition is highlighted in each panel for reference.

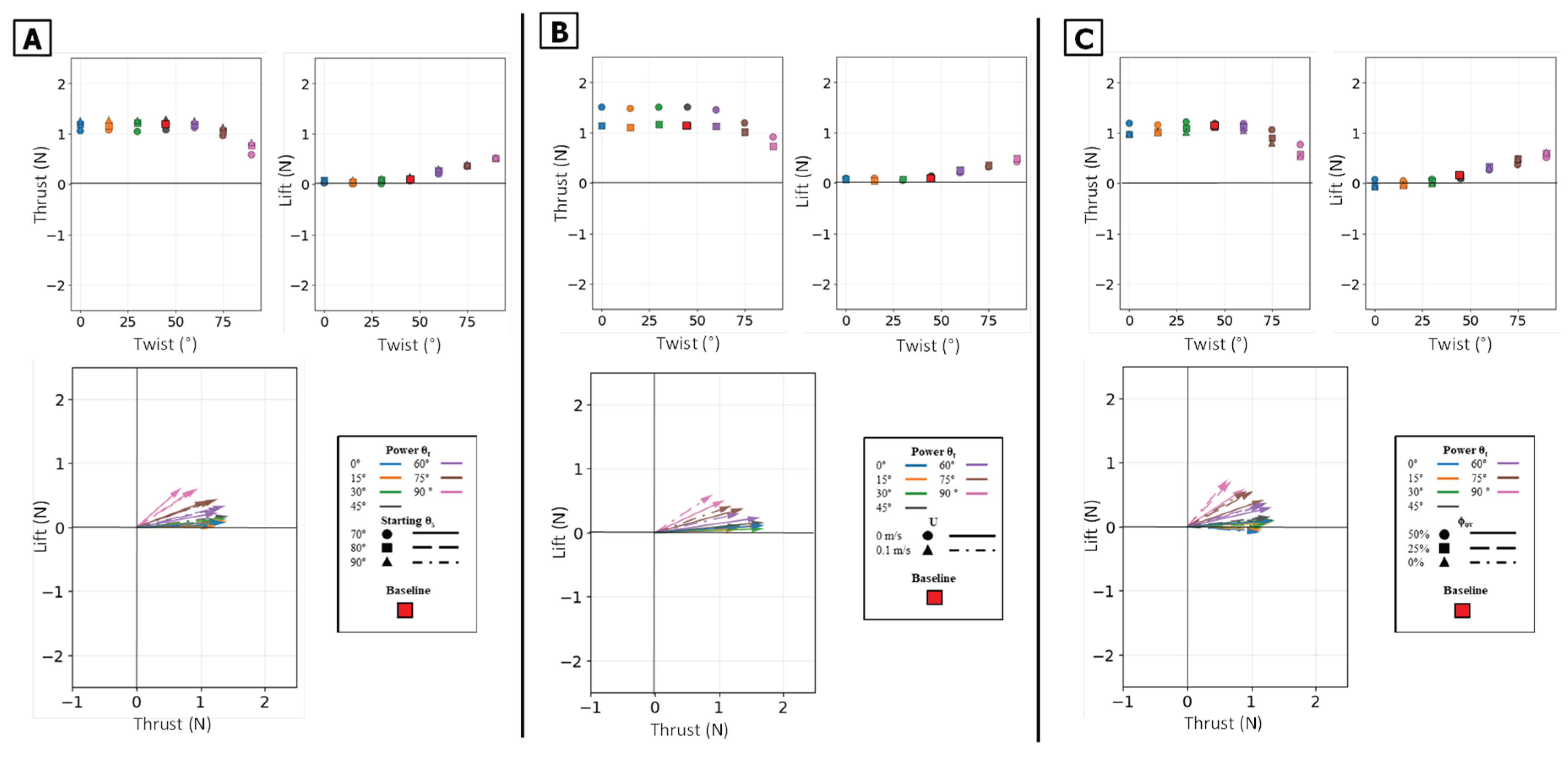

Figure 11.

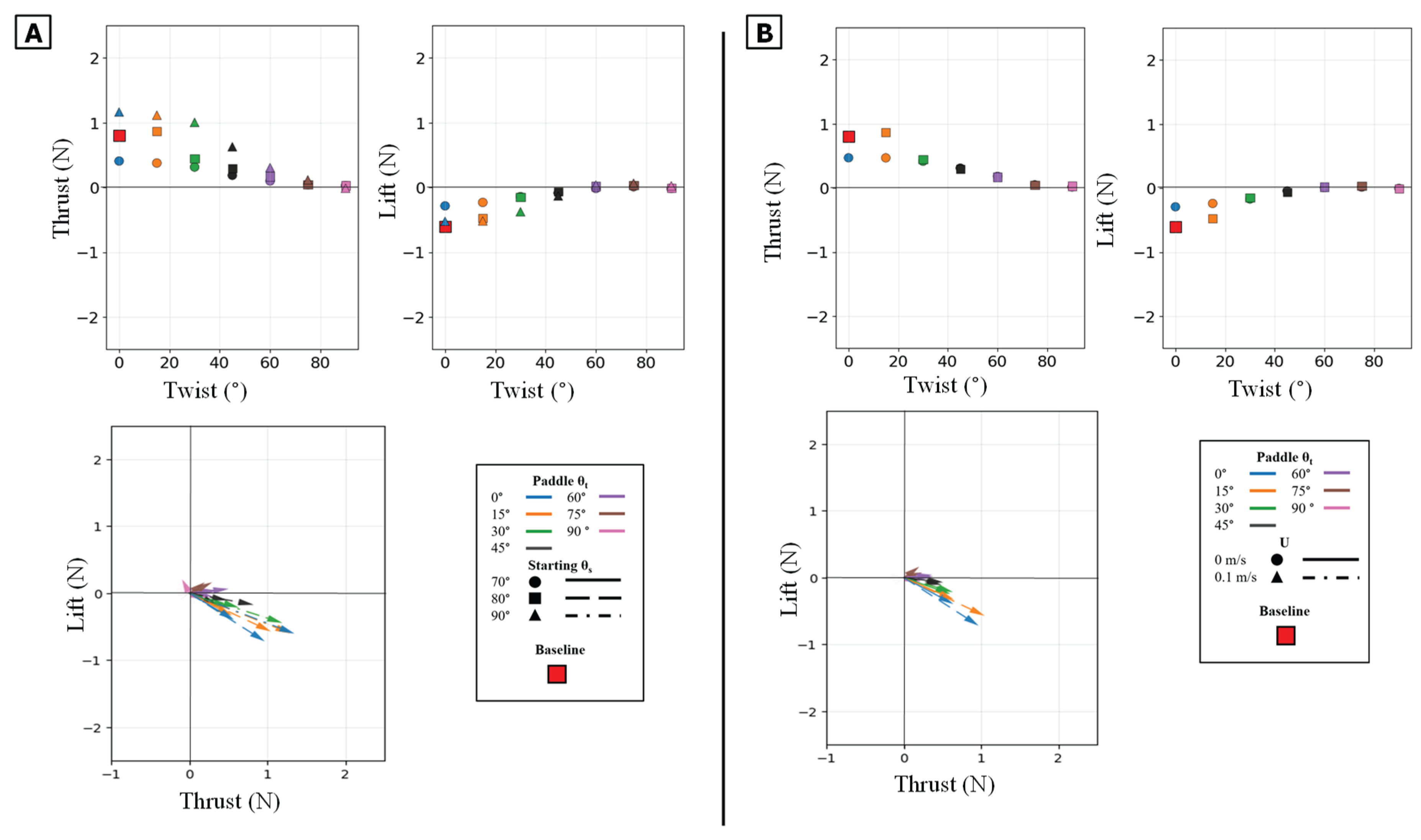

Summary of mean propulsive forces generated during the isolated power phase. Panel (A) illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Sweep Angle (θs) on mean Thrust (left) and mean Lift (middle) and Lift vs Thrust vector (Bottom) Panel (B) illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Flow Speed (U) on mean Thrust (left) and mean Lift (middle) and Lift vs Thrust.

Figure 11.

Summary of mean propulsive forces generated during the isolated power phase. Panel (A) illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Sweep Angle (θs) on mean Thrust (left) and mean Lift (middle) and Lift vs Thrust vector (Bottom) Panel (B) illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Flow Speed (U) on mean Thrust (left) and mean Lift (middle) and Lift vs Thrust.

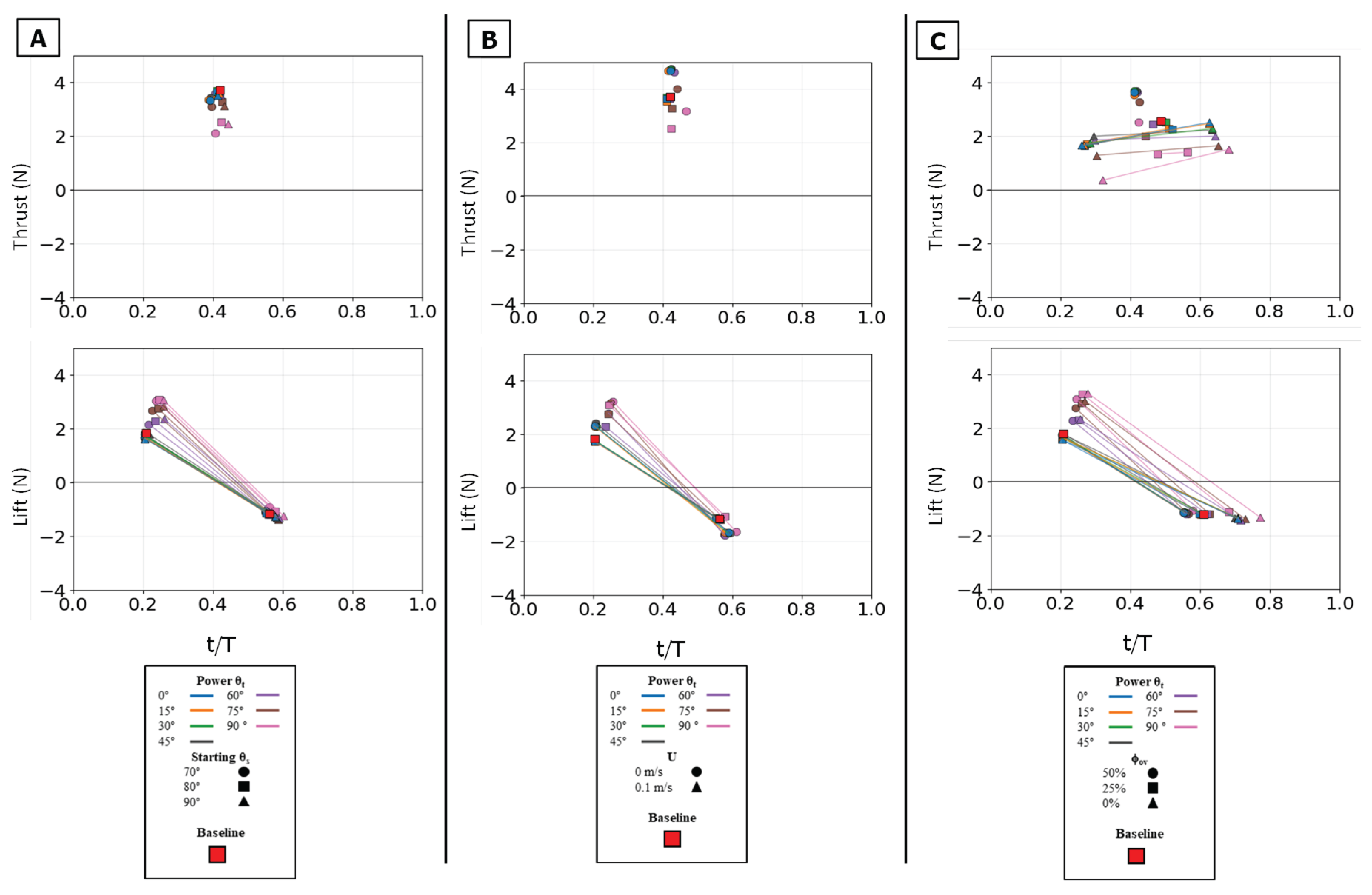

Figure 12.

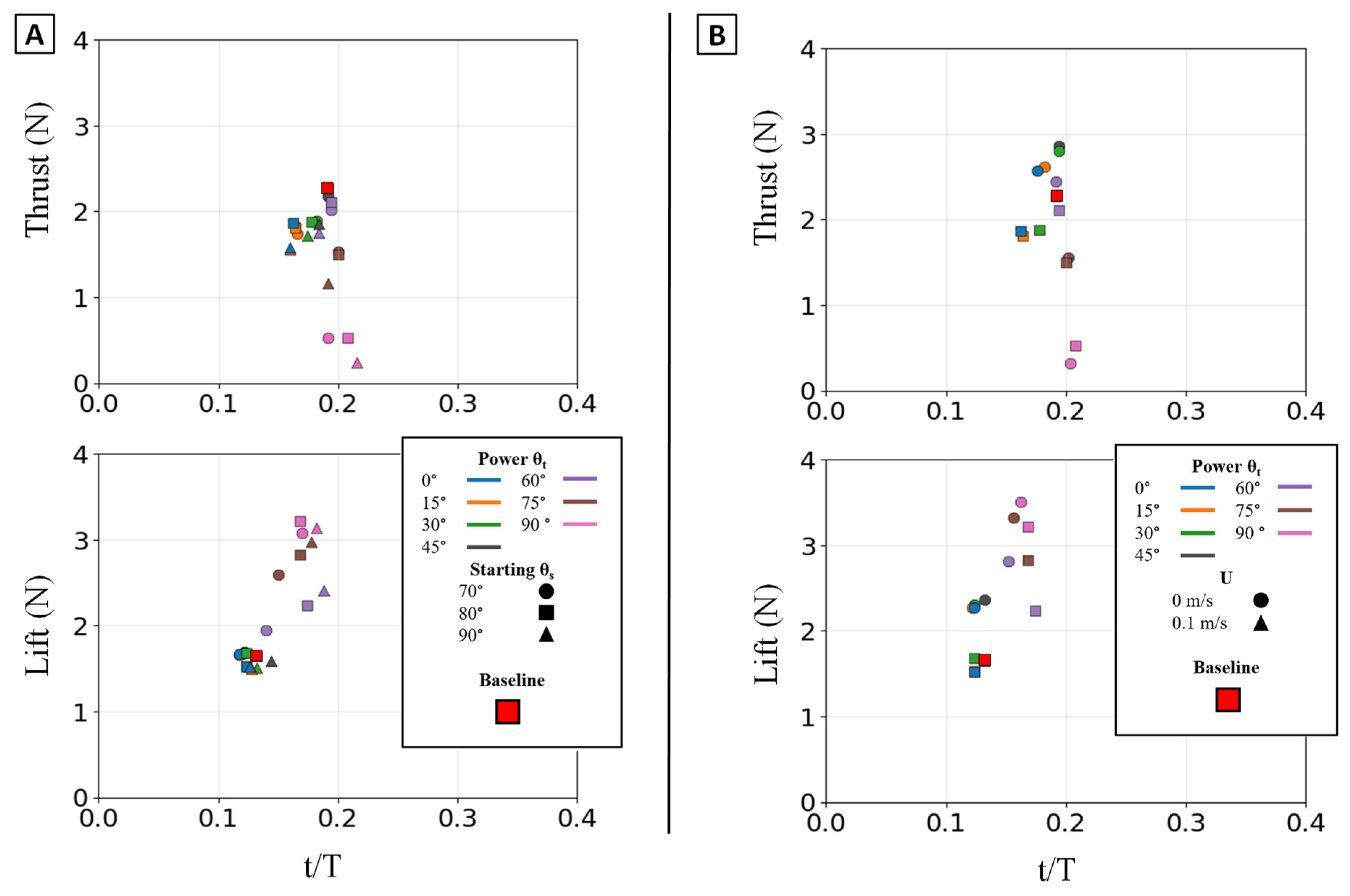

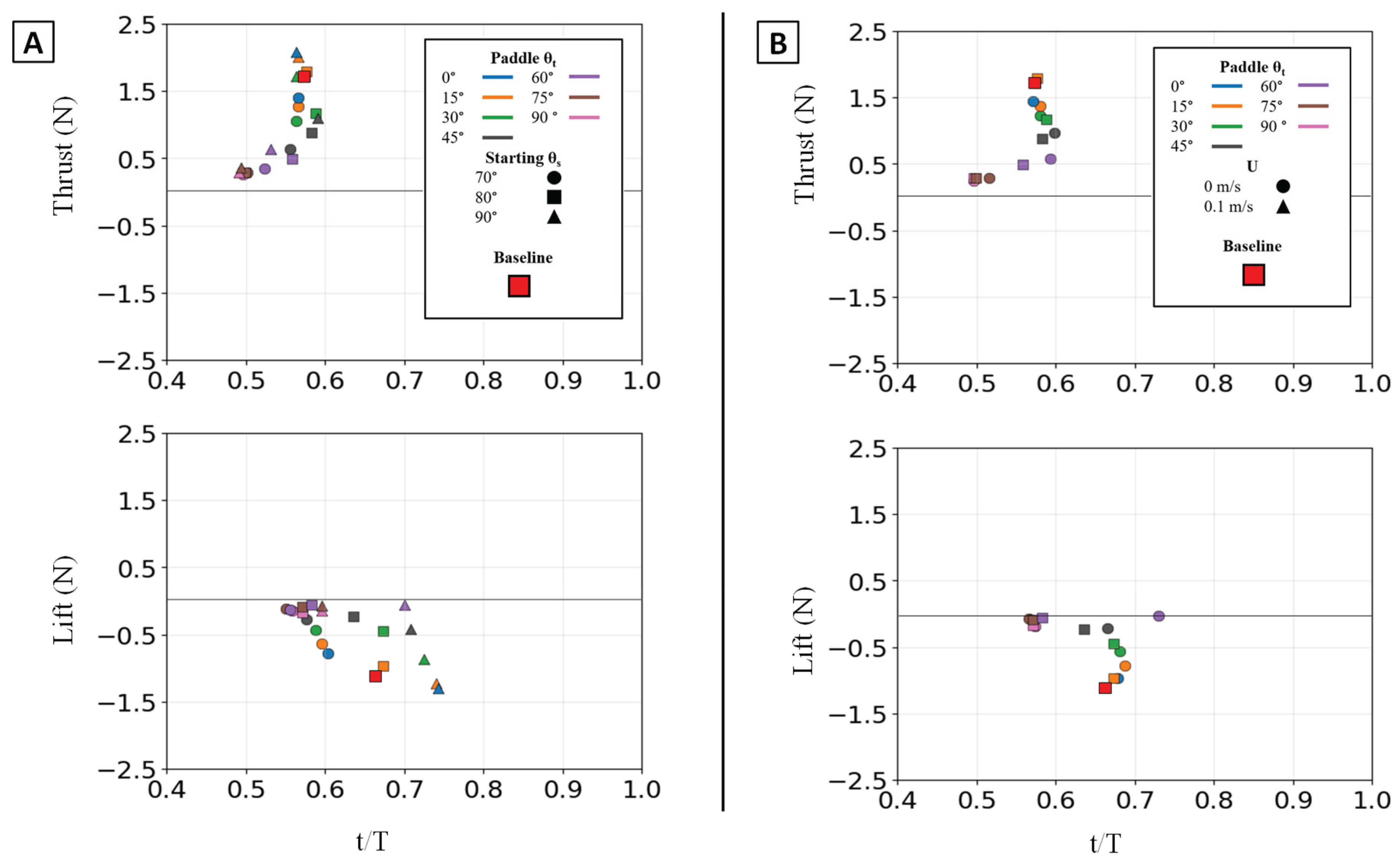

Peak magnitude and peak timing for the isolated power phase. Peak force magnitude (N, y-axis) is plotted against nondimensional peak timing (t/T, x-axis) for both peak thrust (top row) and peak lift (bottom row). (A) Illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Sweep Angle (θs). (B) Illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt)) and Flow Speed (U,). The baseline condition is identified by the red square.

Figure 12.

Peak magnitude and peak timing for the isolated power phase. Peak force magnitude (N, y-axis) is plotted against nondimensional peak timing (t/T, x-axis) for both peak thrust (top row) and peak lift (bottom row). (A) Illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Sweep Angle (θs). (B) Illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt)) and Flow Speed (U,). The baseline condition is identified by the red square.

Figure 13.

Effect of kinematic variations on isolated paddle phase forces. Time-varying thrust (top row) and lift (bottom row) traces are shown for manipulations of the baseline stroke. (A) Effect of varying the flipper twist angle (θt) from 0° to 90°. (B) Effect of varying the starting sweep angle (θs) from 70° to 90°. (C) Effect of the presence of oncoming flow (U). The horizontal axis is nondimensional time (t/T), and the vertical axis is force (N). The baseline (BL) condition is highlighted in each panel for reference.

Figure 13.

Effect of kinematic variations on isolated paddle phase forces. Time-varying thrust (top row) and lift (bottom row) traces are shown for manipulations of the baseline stroke. (A) Effect of varying the flipper twist angle (θt) from 0° to 90°. (B) Effect of varying the starting sweep angle (θs) from 70° to 90°. (C) Effect of the presence of oncoming flow (U). The horizontal axis is nondimensional time (t/T), and the vertical axis is force (N). The baseline (BL) condition is highlighted in each panel for reference.

Figure 14.

Summary of mean propulsive forces generated during the isolated paddle phase. Panel (A) illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Sweep Angle (θs) on mean Thrust (left) and mean Lift (middle) and Lift vs Thrust vector (Bottom) Panel (B) illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Flow Speed (U) on mean Thrust (left) and mean Lift (middle) and Lift vs Thrust.

Figure 14.

Summary of mean propulsive forces generated during the isolated paddle phase. Panel (A) illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Sweep Angle (θs) on mean Thrust (left) and mean Lift (middle) and Lift vs Thrust vector (Bottom) Panel (B) illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Flow Speed (U) on mean Thrust (left) and mean Lift (middle) and Lift vs Thrust.

Figure 15.

Peak magnitude and peak timing for the isolated paddle phase. Peak force magnitude (N, y-axis) is plotted against nondimensional peak timing (t/T, x-axis) for both peak thrust (top row) and peak lift (bottom row). (A) Illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Sweep Angle (θs). (B) Illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt)) and Flow Speed (U,). The baseline condition is identified by the red square.

Figure 15.

Peak magnitude and peak timing for the isolated paddle phase. Peak force magnitude (N, y-axis) is plotted against nondimensional peak timing (t/T, x-axis) for both peak thrust (top row) and peak lift (bottom row). (A) Illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Sweep Angle (θs). (B) Illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt)) and Flow Speed (U,). The baseline condition is identified by the red square.

Figure 16.

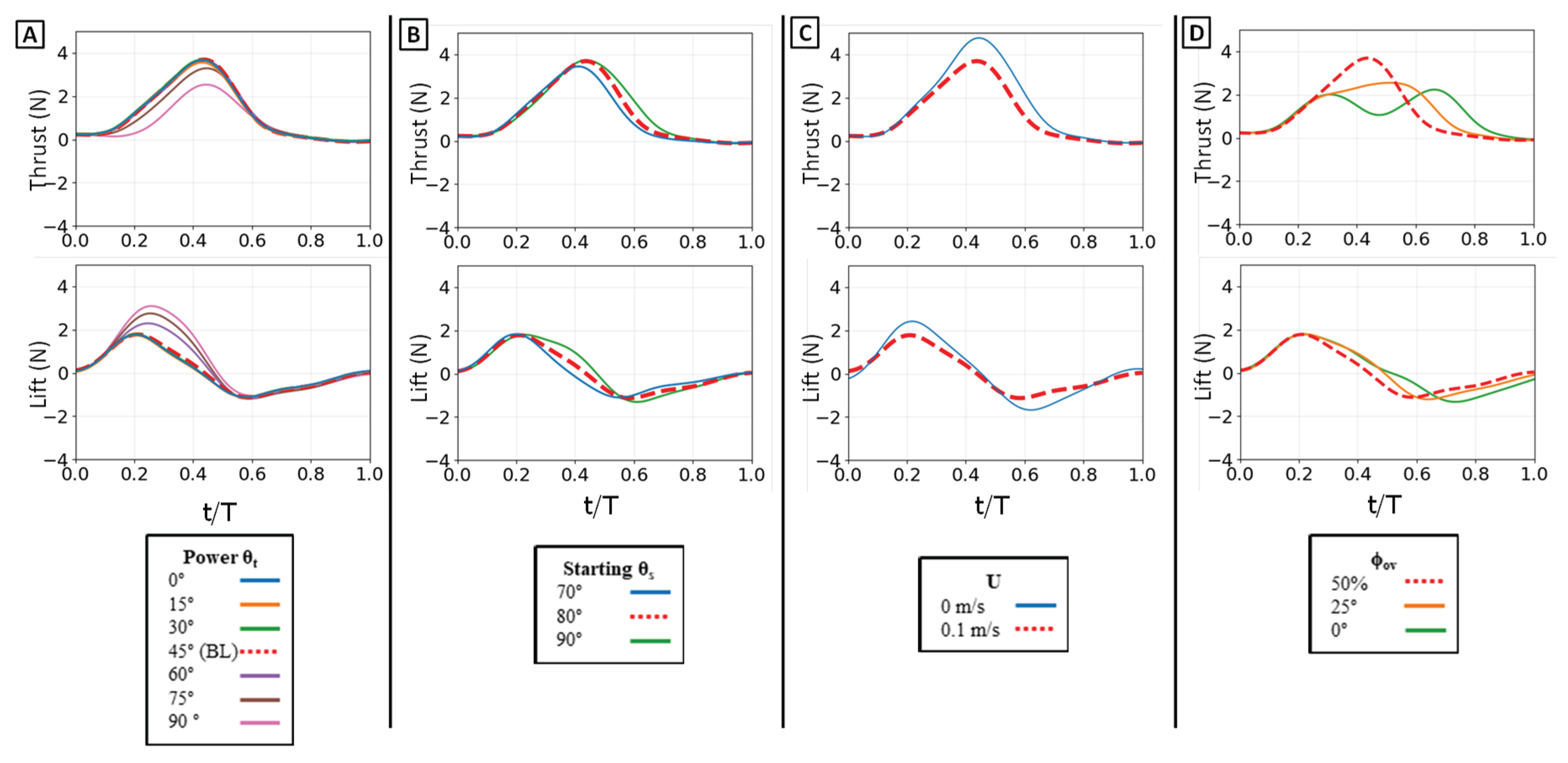

Effect of kinematic variations on full-stroke forces. Time-varying thrust (top row) and lift (bottom row) traces are shown. (A) Effect of varying the flipper twist angle (θt). (B) Effect of varying the starting sweep angle (θs). (C) Effect of the presence of oncoming flow (U). (D) Effect of varying the phase overlap (ϕov). The horizontal axis is nondimensional time (t/T), and the vertical axis is force (N). The baseline (BL) condition is highlighted for reference.

Figure 16.

Effect of kinematic variations on full-stroke forces. Time-varying thrust (top row) and lift (bottom row) traces are shown. (A) Effect of varying the flipper twist angle (θt). (B) Effect of varying the starting sweep angle (θs). (C) Effect of the presence of oncoming flow (U). (D) Effect of varying the phase overlap (ϕov). The horizontal axis is nondimensional time (t/T), and the vertical axis is force (N). The baseline (BL) condition is highlighted for reference.

Figure 17.

Summary of mean propulsive forces generated during the full stroke. Panel (A) illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Sweep Angle (θs) on mean Thrust (top left) and mean Lift (top right). Panel (B) illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Flow Speed (U). Panel (C) illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt, colors) and Phase Overlap (ϕov). The plots in the bottom row show the corresponding force vectors (Lift vs. Thrust) for each set of conditions. The baseline condition is identified by the red square.

Figure 17.

Summary of mean propulsive forces generated during the full stroke. Panel (A) illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Sweep Angle (θs) on mean Thrust (top left) and mean Lift (top right). Panel (B) illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Flow Speed (U). Panel (C) illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt, colors) and Phase Overlap (ϕov). The plots in the bottom row show the corresponding force vectors (Lift vs. Thrust) for each set of conditions. The baseline condition is identified by the red square.

Figure 18.

Peak magnitude and peak timing for the full stroke. Peak force magnitude (N, y-axis) is plotted against nondimensional peak timing (t/T, x-axis) for both peak thrust (top row) and peak lift (bottom row). (A) Illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Sweep Angle (θs). (B) Illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Flow Speed (U). (C) Illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Phase Overlap (ϕov). For each condition (color), thin lines connect the multiple force peaks (e.g., positive power-phase lift and negative paddle-phase lift) that occur within that single stroke cycle. The baseline condition is identified by the red square.

Figure 18.

Peak magnitude and peak timing for the full stroke. Peak force magnitude (N, y-axis) is plotted against nondimensional peak timing (t/T, x-axis) for both peak thrust (top row) and peak lift (bottom row). (A) Illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Sweep Angle (θs). (B) Illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Flow Speed (U). (C) Illustrates the effect of varying the Twist Angle (θt) and Phase Overlap (ϕov). For each condition (color), thin lines connect the multiple force peaks (e.g., positive power-phase lift and negative paddle-phase lift) that occur within that single stroke cycle. The baseline condition is identified by the red square.

Table 1.

Independent Variables for Each Phase of the Experimentation.

Table 1.

Independent Variables for Each Phase of the Experimentation.

| Experimental Parameters |

Power Stroke |

Paddle Stroke |

Combined Power and Paddle Stroke |

| Power θt (°) |

0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90 |

— |

0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90 |

| Paddle θt (°) |

— |

0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90 |

0 |

| Starting θs (°) |

70, 80, 90 |

70, 80, 90 |

70, 80, 90 |

| Period (s) |

2.25 |

2.25 |

2.25 |

| U (m/s) |

0, 0.1 |

0, 0.1 |

0, 0.1 |

| ϕov (%) |

— |

— |

0, 25, 50 |

| Total Experimental Conditions: |

42 |

42 |

126 |

Table 2.

Baseline Stroke Settings by Phase.

Table 2.

Baseline Stroke Settings by Phase.

| Baseline Stroke Settings |

Power θt (◦) |

Paddle θt (◦) |

Starting θs (◦) |

ϕov (%) |

U (m/s) |

Period (s) |

| Power Phase |

45 |

— |

80 |

— |

0.1 |

2.25 |

| Paddle Phase |

— |

0 |

80 |

— |

0.1 |

2.25 |

| Combined Power and Paddle |

45 |

0 |

80 |

50 |

0.1 |

2.25 |