Submitted:

16 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Scope and Contribution

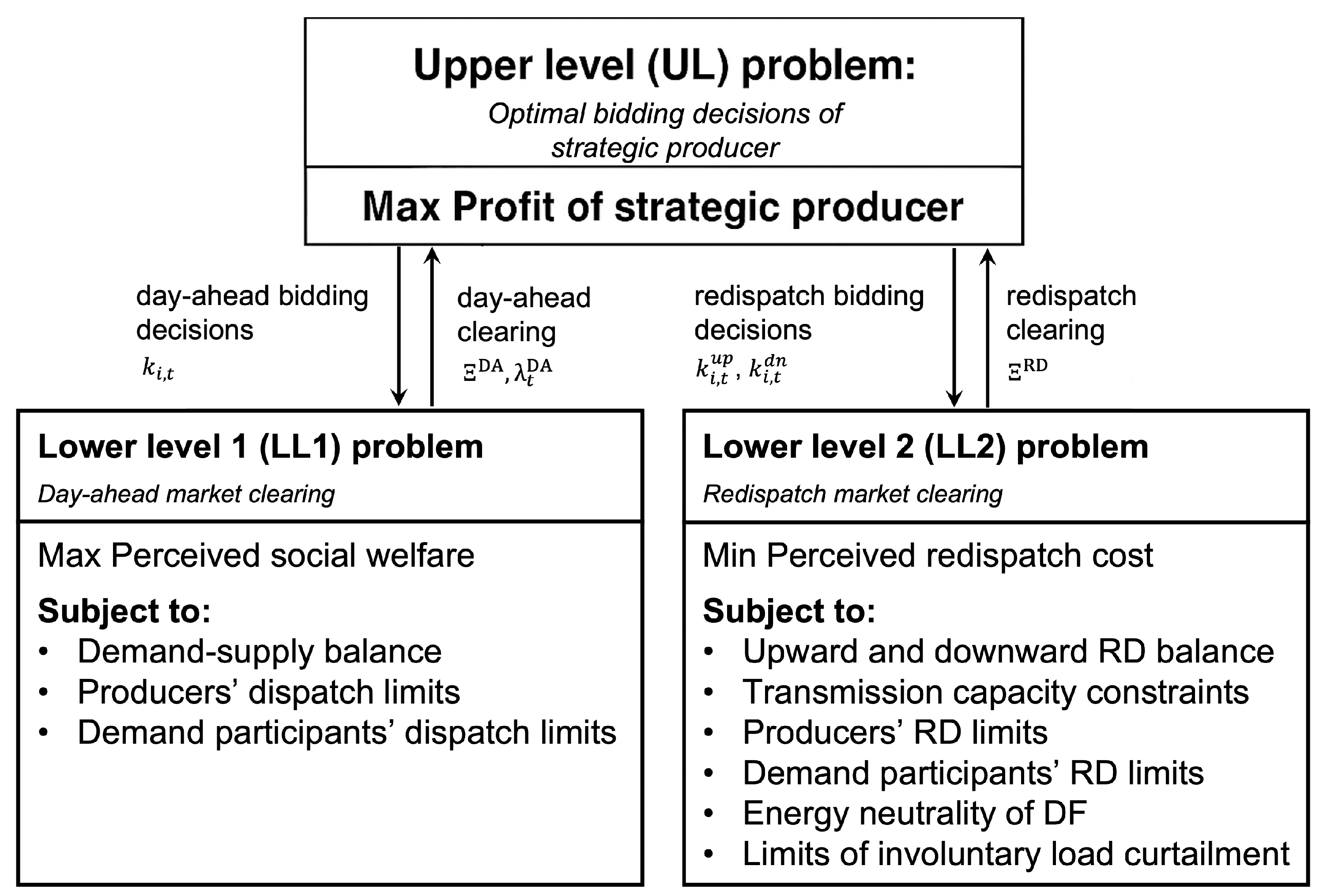

- A multi-period bi-level optimization model of a strategic producer participating in DA and RD markets is proposed, accounting for network constraints and the time-coupling operating characteristics of DF participating in the RD market. The upper level problem determines the optimal bidding decisions of the strategic producer in the DA and RD markets, while the two lower level problems represent the clearing process of the two markets. This bi-level problem is solved by converting it into a Mathematical Program with Equilibrium Constraints (MPEC) and subsequently to a MILP through strong duality and binary expansion techniques.

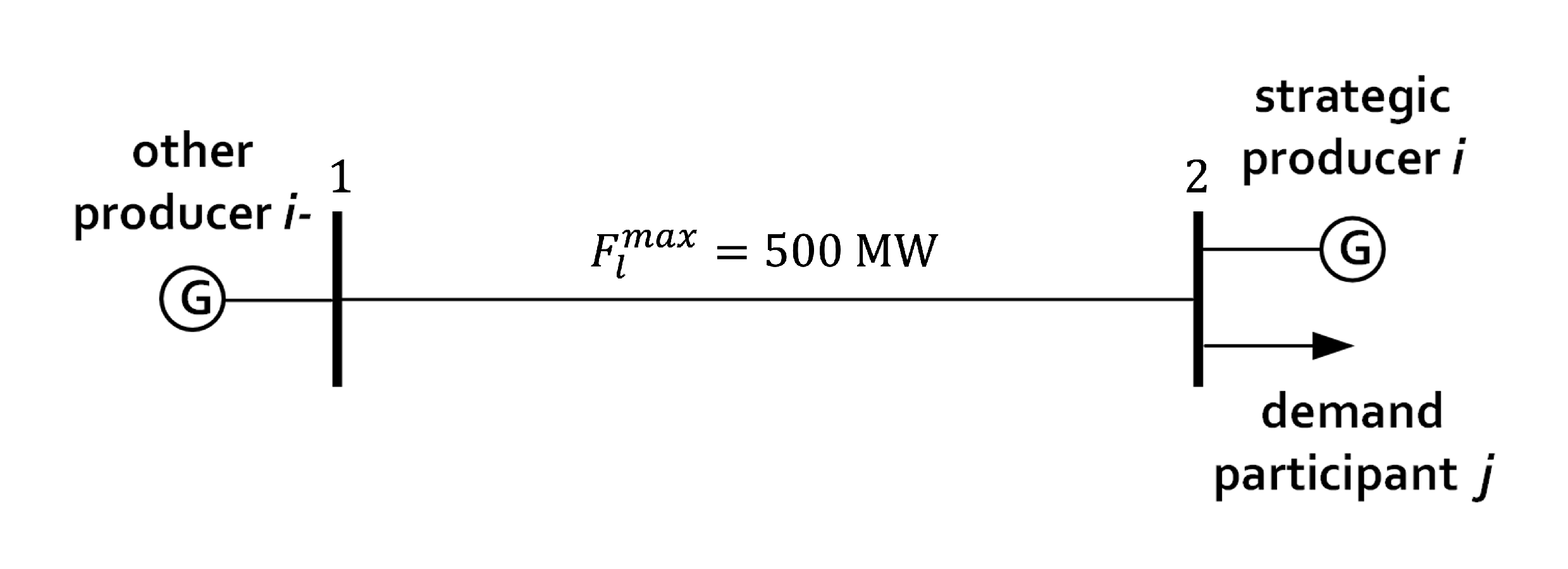

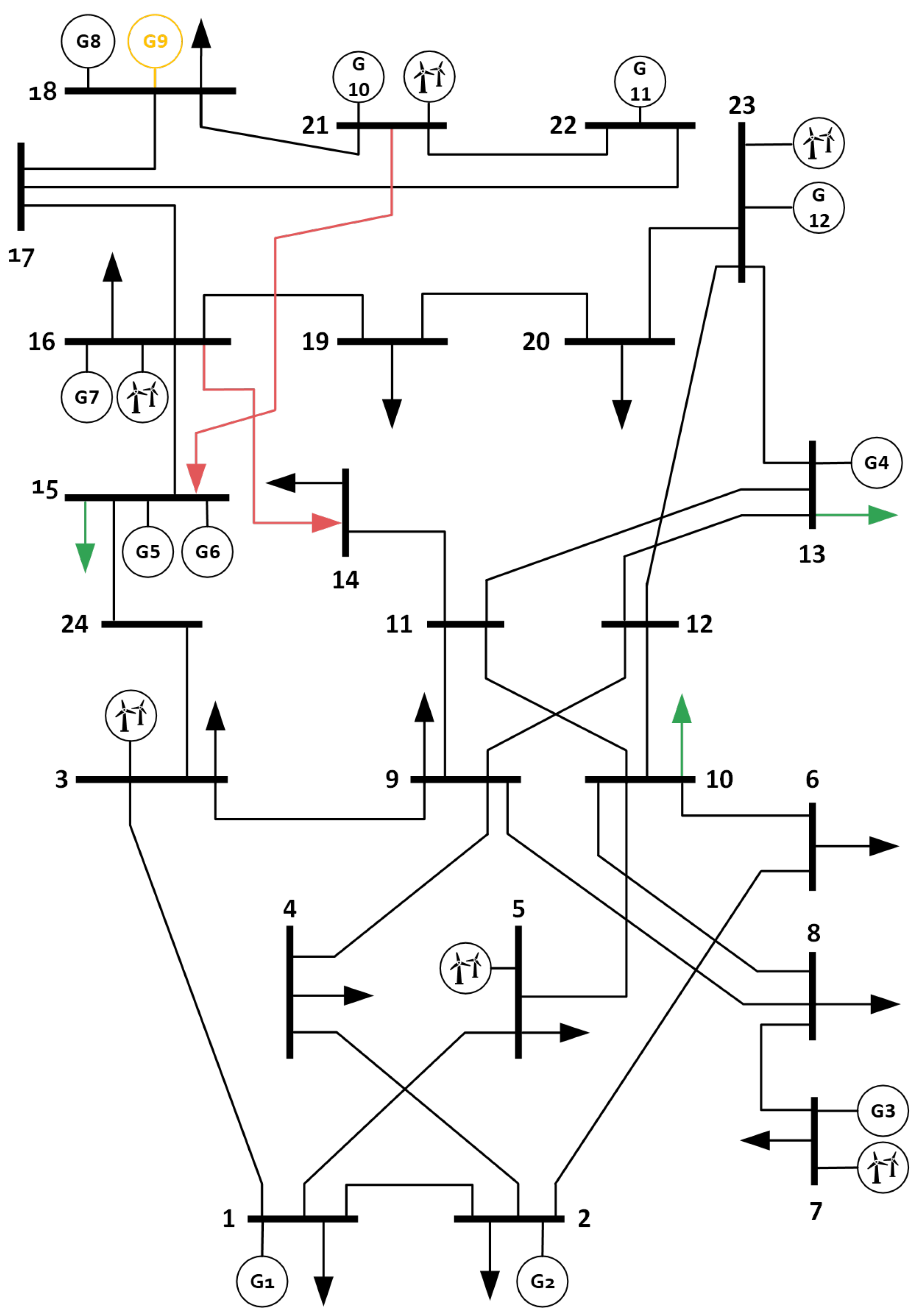

- The role of DF in addressing Inc–Dec gaming, as well as the generic applicability of the proposed model, are demonstrated through two case studies: a simple 2-node, 2-period example, and a large-scale case study based on a modified IEEE RTS 24-node system over a 24-hour horizon.

1.3. Paper Structure

2. Modeling Approach

2.1. Modeling Assumptions

- The modeled DA market is a pool-based, energy-only, zonal market, cleared by the market clearing agent through the solution of a social welfare maximization problem which ignores within-zone network constraints and adopts pay-as-clear pricing.

- The modeled RD market is a pool-based, pay-as-bid (as commonly implemented in the EU) market, cleared by the TSO, who also acts as the sole buyer, in order to resolve within-zone network congestion with the minimum RD cost. The TSO employs a DC power flow model and Generation Shift Factors (GSFs) to represent network constraints. The RD market clearing follows the DA market clearing.

- Considering the focus of the paper, and for the sake of simplicity, the model considers a single bidding zone (the one where the strategic producer is located), and thus disregards market coupling.

- For clarity, and without loss of generality, the model assumes that each producer owns a single generation unit and submits a single price-quantity bid for this generation unit for each time period t and in each of the two considered markets. For the same reasons, the model assumes that each demand participant submits a single bid for each time period t, including in the RD market when the unit provides flexibility.

- Expanding the approach employed in [22], the strategic behavior of producer i is expressed through the decision variables , and . Specifically, expresses its behavior in the DA market with implying that it behaves competitively and reveals its actual marginal cost to the DA market, while and imply that it behaves strategically (overbids and underbids, respectively). In a similar fashion, and express its behavior in the RD market (upward and downward, respectively), with and implying that it behaves competitively.

- DF is incorporated in the RD market clearing problem through a generic, technology-agnostic, and inter-temporal model, which follows the approach of [23,24,25,26,27]. Specifically, the load of the demand participant j at time period t can be reduced or increased relative to its dispatch in the DA market, but a) this reduction/increase is subject to certain limits (prescribed by the relative parameter ), b) it entails a quantifiable marginal cost of discomfort [26] which also constitutes the price offered by j in the RD market (i.e., strategic behavior of flexible demand participants is neglected), and c) the total size of demand reductions is equal to the total size of demand increases within the considered daily market horizon, implying that demand shifting is energy neutral.

2.2. Bi-Level Optimization Model of Strategic Producer

2.3. MPEC Model of the Strategic Producer

2.4. MILP Model of the Strategic Producer

3. Small-Scale Case Study

- Benchmark: All producers behave competitively in both DA and RD markets, while the demand does not exhibit any DF. This scenario is implemented by forcing in the proposed model, as well as setting

- Strategic: The producer connected to node 2 behaves strategically in the DA and RD markets by employing the proposed model with , , being decision variables. The demand does not exhibit any DF ().

- Strategic + DF: The producer connected to node 2 behaves strategically in the DA and RD markets, and the demand exhibits DF characterized by .

3.1. Increase-Decrease (Inc-Dec) Gaming

3.2. Role of DF in Addressing Inc-Dec Gaming

4. Large-Scale Case Study

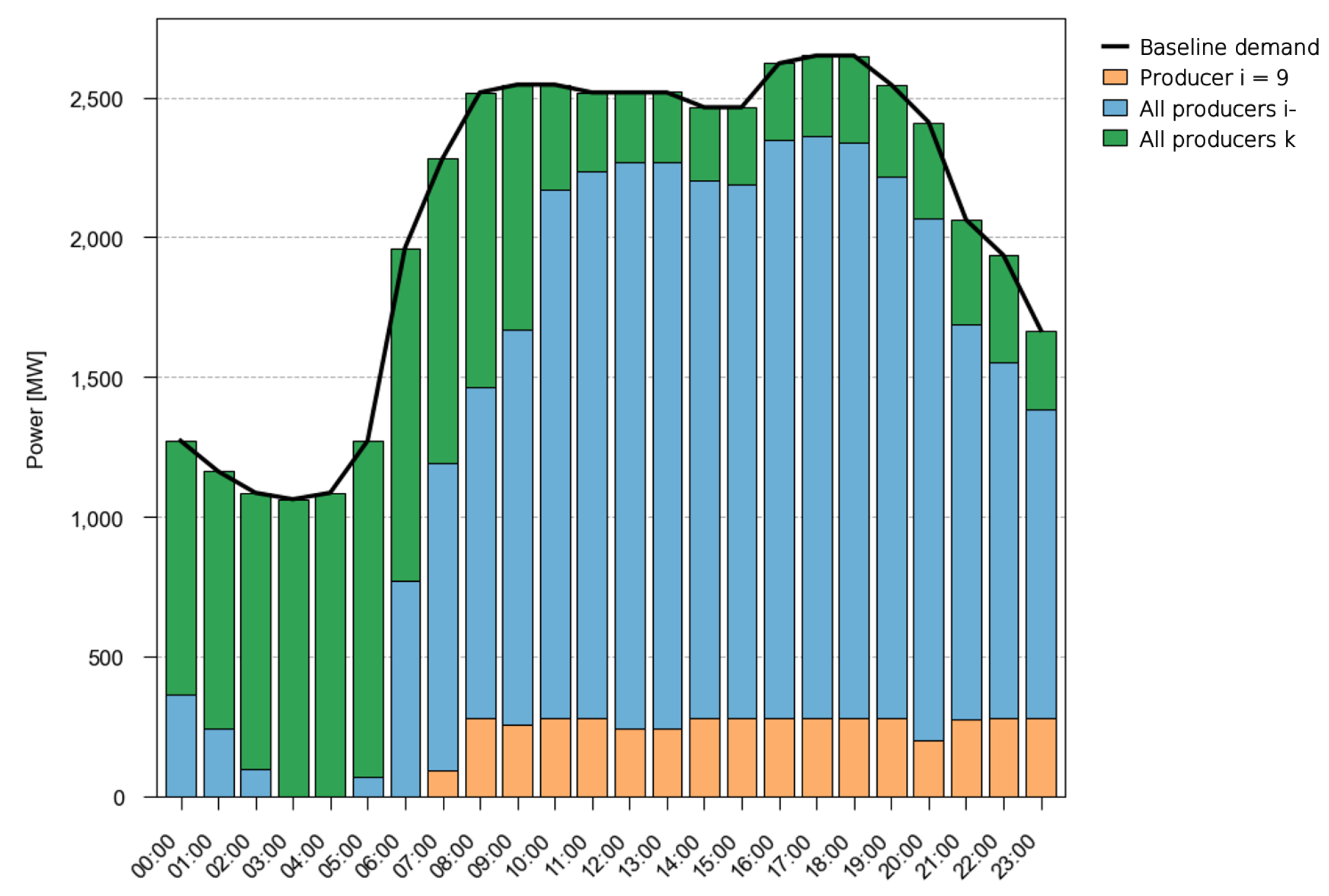

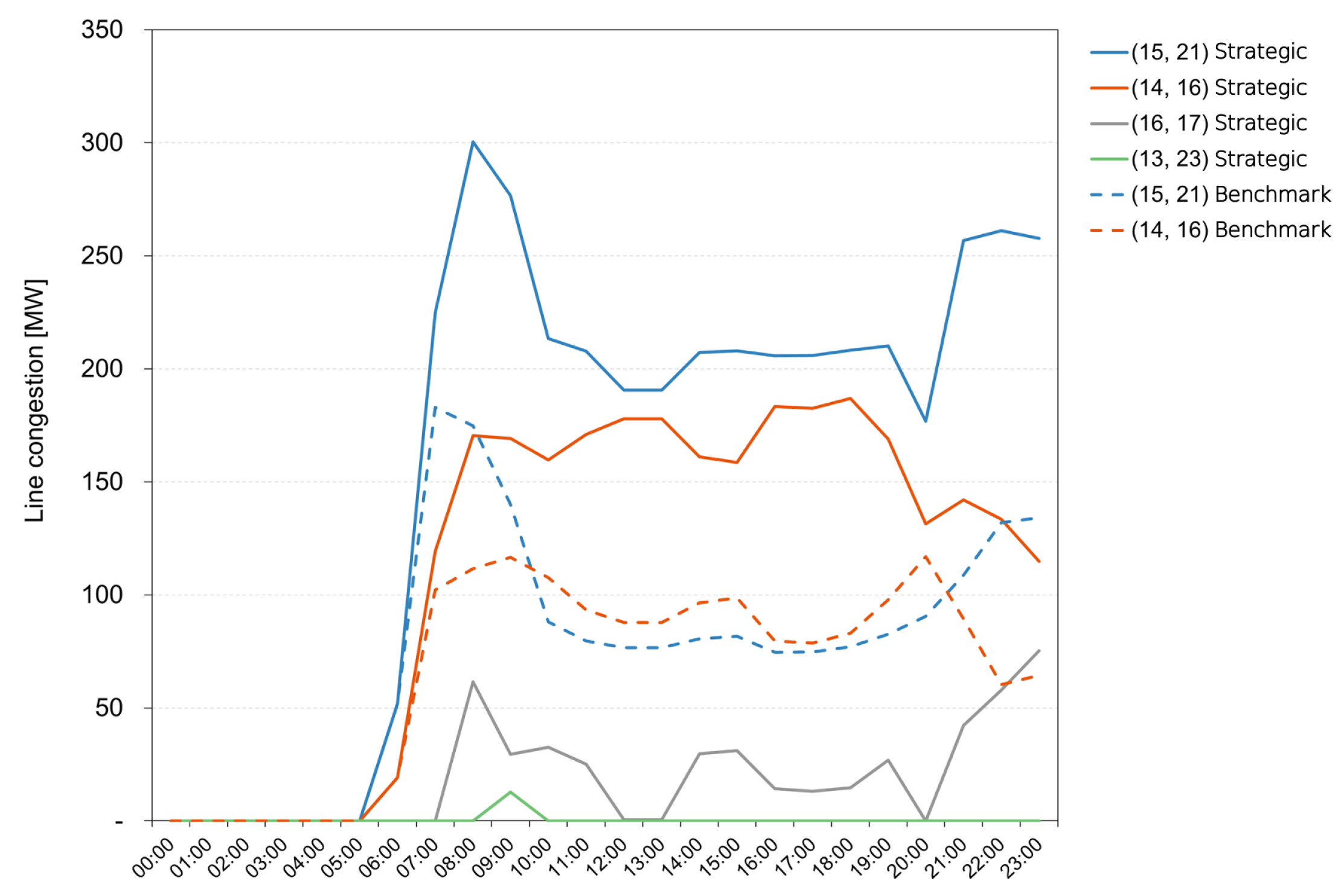

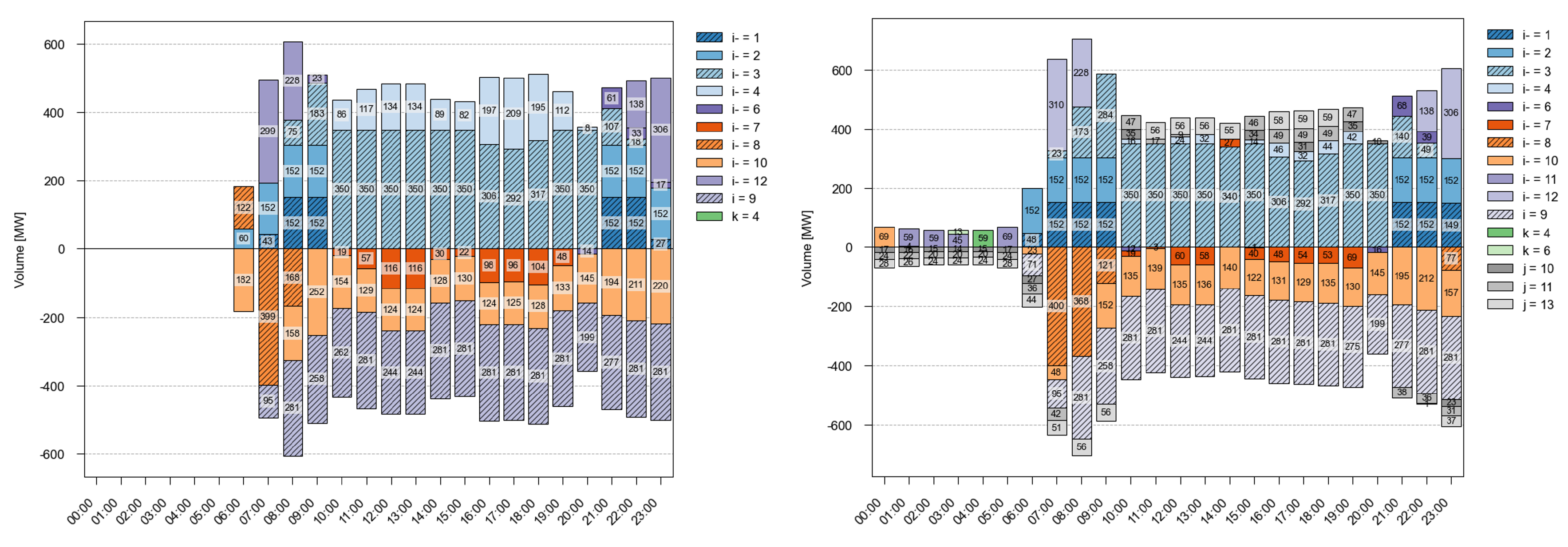

4.1. Increase-Decrease (Inc-Dec) Gaming

4.2. Role of DF in Addressing Inc-Dec Gaming

5. Conclusion and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Indices and Sets | |

| Index and set of time periods | |

| i | Index of strategic conventional producer |

| Index and set of conventional producers other than i | |

| Index and set of renewable producers | |

| Index and set of demands | |

| Index and set of network nodes | |

| Index and set of network lines | |

| Subset of conventional producers i connected to n | |

| Subset of conventional producers other than i connected to n | |

| Subset of renewable producers k connected to n | |

| Subset of demands j connected to n | |

| Parameters | |

| Marginal benefit of demand j [£/MWh] | |

| Discomfort cost of demand j for shifting demand away from t [£/MWh] | |

| Discomfort cost of demand j for shifting demand towards t [£/MWh] | |

| VoLL | Value of lost load [£/MWh] |

| Maximum power of conventional producer i [MW] | |

| Maximum power of renewable producer k at t [MW] | |

| Maximum baseline power of demand j at t [MW] | |

| Generation Shift Factor between node n and line l | |

| Transmission capacity of network line l [MW] | |

| Load shifting limit of demand j [%] | |

| Variables | |

| Day-ahead market dispatch of producer i at t [MW] | |

| Day-ahead market dispatch of demand j at t [MW] | |

| Day-ahead market clearing price at t [£/MWh] | |

| Day-ahead strategic bidding variable of producer i at t | |

| Upward redispatch strategic bidding variable of producer i at t | |

| Downward redispatch strategic bidding variable of producer i at t | |

| Upward redispatch provided by producer i at t [MW] | |

| Downward redispatch provided by producer i at t [MW] | |

| Power of demand j shifted away from t [MW] | |

| Power of demand j shifted towards t [MW] | |

| Unserved power of demand j at t [MW] |

Abbreviations

| ACER | EU Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators |

| DA | Day-ahead |

| DF | Demand flexibility |

| EPEC | Equilibrium Problem with Equilibrium Constraints |

| GSF | Generation Shift Factor |

| KKT | Karush–Kuhn–Tucker |

| LL | Lower Level |

| MILP | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming |

| MPEC | Mathematical Program with Equilibrium Constraints |

| TSO | Transmission System Operator |

| RD | Redispatch |

| UL | Upper Level |

Appendix A. Strong Duality Applied to Day-Ahead Revenues

Appendix B. Data Input IEEE 24-Nodes Case Study

| Node | % of Wind Capacity |

|---|---|

| 3 | 16.7 |

| 5 | 16.7 |

| 7 | 16.7 |

| 16 | 16.7 |

| 21 | 16.7 |

| 23 | 16.7 |

| Hour | Wind (MW) | Hour | Wind (MW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 907 | 13 | 250 |

| 2 | 925 | 14 | 250 |

| 3 | 986 | 15 | 263 |

| 4 | 1,010 | 16 | 275 |

| 5 | 1,037 | 17 | 275 |

| 6 | 1,200 | 18 | 288 |

| 7 | 1,190 | 19 | 313 |

| 8 | 1,084 | 20 | 326 |

| 9 | 1,055 | 21 | 344 |

| 10 | 876 | 22 | 376 |

| 11 | 376 | 23 | 382 |

| 12 | 282 | 24 | 284 |

| From node | To node | Reactance (p.u.) | Capacity (MW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 0.0146 | 175 |

| 1 | 3 | 0.2253 | 175 |

| 1 | 5 | 0.0907 | 350 |

| 2 | 4 | 0.1356 | 175 |

| 2 | 6 | 0.2050 | 175 |

| 3 | 9 | 0.1271 | 175 |

| 3 | 24 | 0.0840 | 400 |

| 4 | 9 | 0.1110 | 175 |

| 5 | 10 | 0.0940 | 350 |

| 6 | 10 | 0.0642 | 175 |

| 7 | 8 | 0.0652 | 350 |

| 8 | 9 | 0.1762 | 175 |

| 8 | 10 | 0.1762 | 175 |

| 9 | 11 | 0.0840 | 400 |

| 9 | 12 | 0.0840 | 400 |

| 10 | 11 | 0.0840 | 400 |

| 10 | 12 | 0.0840 | 400 |

| 11 | 13 | 0.0488 | 500 |

| 11 | 14 | 0.0426 | 500 |

| 12 | 13 | 0.0488 | 500 |

| 12 | 23 | 0.0985 | 500 |

| 13 | 23 | 0.0884 | 500 |

| 14 | 16 | 0.0594 | 500 |

| 15 | 16 | 0.0172 | 500 |

| 15 | 21 | 0.0249 | 1,000 |

| 15 | 24 | 0.0529 | 500 |

| 16 | 17 | 0.0263 | 500 |

| 16 | 19 | 0.0234 | 500 |

| 17 | 18 | 0.0143 | 500 |

| 17 | 22 | 0.1069 | 500 |

| 18 | 21 | 0.0132 | 1,000 |

| 19 | 20 | 0.0203 | 1,000 |

| 20 | 23 | 0.0112 | 1,000 |

| 21 | 22 | 0.0692 | 500 |

| Producer i | Node | Marginal Cost (£/MWh) | Maximum Output (MW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 13.32 | 152 |

| 2 | 2 | 11.32 | 152 |

| 3 | 7 | 20.70 | 350 |

| 4 | 13 | 20.93 | 591 |

| 5 | 15 | 26.11 | 60 |

| 6 | 15 | 12.52 | 155 |

| 7 | 16 | 18.52 | 155 |

| 8 | 18 | 6.02 | 400 |

| 9 | 18 | 26.50 | 281 |

| 10 | 21 | 5.47 | 400 |

| 11 | 22 | 0.50 | 300 |

| 12 | 23 | 10.52 | 300 |

| Demand j | Node | % of System Demand |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 3.8 |

| 2 | 2 | 3.4 |

| 3 | 3 | 6.3 |

| 4 | 4 | 2.6 |

| 5 | 5 | 2.5 |

| 6 | 6 | 4.8 |

| 7 | 7 | 4.4 |

| 8 | 8 | 6.0 |

| 9 | 9 | 6.1 |

| 10 | 10 | 6.8 |

| 11 | 13 | 9.3 |

| 12 | 14 | 6.8 |

| 13 | 15 | 11.1 |

| 14 | 16 | 3.5 |

| 15 | 18 | 11.7 |

| 16 | 19 | 6.4 |

| 17 | 20 | 4.5 |

| Hour | Demand (MW) | Hour | Demand (MW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,272 | 13 | 2,518 |

| 2 | 1,166 | 14 | 2,465 |

| 3 | 1,087 | 15 | 2,465 |

| 4 | 1,069 | 16 | 2,518 |

| 5 | 1,087 | 17 | 2,624 |

| 6 | 1,272 | 18 | 2,651 |

| 7 | 1,961 | 19 | 2,651 |

| 8 | 2,279 | 20 | 2,544 |

| 9 | 2,518 | 21 | 2,412 |

| 10 | 2,651 | 22 | 2,067 |

| 11 | 2,624 | 23 | 1,723 |

| 12 | 2,597 | 24 | 1,193 |

References

- Kirschen, D.; Strbac, G. Fundamentals of Power System Economics, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: United Kingdom, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EU) 2024/1747 of the European Parliament and of the Council. OJ L, 2024/1747, 26.6.2024.

- ACER. Transmission capacities for cross-zonal trade of electricity and congestion management in the EU: 2024 Market Monitoring Report. Market Monitoring Report 2024, Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2024.

- Thomassen, G.; Fuhrmanek, A.; Cadenovic, R.; Pozo Camara, D.; Vitiello, S. “Redispatch and Congestion Management. Future-Proofing the European Power Market”. Tech. Rep. EUR 31924 EN, European Commission, JRC, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the EU, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Joskow, P.L.; Tirole, J. Transmission Rights and Market Power on Electric Power Networks. RAND Journal of Economics 2000, 31, 450–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggar, D.R.; Hesamzadeh, M.R. The Economics of Electricity Markets; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg, P. The Inc–Dec Game and How to Mitigate It. Report 2024:1035, Energiforsk / The Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IFN), Stockholm, Sweden, 2024.

- Alaywan, Z.; Wu, T.; Papalexopoulos, A. “Transitioning the California market from a zonal to a nodal framework: an operational perspective”. In Proceedings of the IEEE PES Power Syst. Conf. and Exp., 2004., 2004, pp. 862–867 vol.2. [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, C.; Strbac, G. “Empirics of Intraday and Real-time Markets in Europe: Great Britain”. EconStor Research Reports 111266, ZBW - Leibniz Inf. Centre for Econ., 2015.

- Graf, C.; Quaglia, F.; Wolak, F.A. “Simplified Electricity Market Models with Significant Intermittent Renewable Capacity: Evidence from Italy”. Work. Paper 2 7262, Nat. Bur. of Econ. Res. (NBER), 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnaars, P.; Perino, G. Arbitrage in Cost-Based Redispatch: Evidence from Germany. Technical report, SSRN Electronic Journal, 2021. Available online; accessed on 26 October 2025. [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, P.; Lazarczyk, E. “Comparison of congestion management techniques: nodal, zonal and discriminatory pricing”. The Energy J. 2015, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirth, L.; Ingmar, S. “Market-Based Redispatch in Zonal Electricity Markets: The Preconditions for and Consequence of Inc-Dec Gaming”. ZBW – Leibniz Inf. Centre for Econ., 2020.

- et al., K.E. “Congestion Management Games in Electricity Markets”. Disc. Paper 22-060, ZEW - Centre for Eur. Econ. Res., 2022.

- Sarfati, M.; Hesamzadeh, M.; Holmberg, P. “Increase-Decrease Game under Imperfect Competition in Two-stage Zonal Power Markets – Part I: Concept Analysis”. Work. Paper EPRG 1837, Energy Pol. Res. Group, Cambridge Judge Business Sc., Univ. of Cambridge, 2018.

- Sarfati, M.; Holmberg, P. “Simulation and Evaluation of Zonal Electricity Market Designs. Elect. Power Syst. Res. 2020, 185, 116500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckstedde, E.; Meeus, L.; Delarue, E. “A Bilevel Model to Study Inc-Dec Games at the TSO-DSO Interface. IEEE Trans. on Energy Markets, Policy and Reg. 2023, 1, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al., G.S. “Cost-effective decarbonization in a decentralized market: the benefits of using flexible technologies and resources”. IEEE Power and Energy Magazine 2019, 17, 25–36. [CrossRef]

- ACER. “Demand response and other distributed energy resources: what barriers are holding them back?”. Market Monitoring Report, 2023.

- GOPACS. GOPACS – Platform for Congestion Management. https://www.gopacs.eu/en/, 2025. Accessed: 29 June 2025.

- NODES. NODES Platform - NODES market. https://nodesmarket.com, 2025. Accessed: 29 June 2025.

- Ye, Y.; Papadaskalopoulos, D.; Kazempour, J.; Strbac, G. “Incorporating Non-Convex Operating Characteristics Into Bi-Level Optimization Electricity Market Models”. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 35, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Papadaskalopoulos, D.; Strbac, G. “Investigating the Ability of Demand Shifting to Mitigate Electricity Producers’ Market Power”. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 3800–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatouros, P.; Konstantelos, I.; Papadaskalopoulos, D.; Strbac, G. “Stochastic Dual Dynamic Programming for Operation of DER Aggregators Under Multi-Dimensional Uncertainty”. IEEE Trans. Sust. Energy 2019, 10, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oderinwale, T.; Papadaskalopoulos, D.; Ye, Y.; Strbac, G. “Investigating the impact of flexible demand on market-based generation investment planning”. Int. J. of Elect. Power & Energy Syst. 2020, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, D.; Papadaskalopoulos, D.; Ye, Y.; Strbac, G. “Investigating the effects of demand flexibility on electricity retailers’ business through a tri-level optimisation model”. IET Gen., Trans. & Dist. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pediaditis, P.; Papadaskalopoulos, D.; Papavasiliou, A.; Hatziargyriou, N. “Bilevel Optimization Model for the Design of Distribution Use-of-System Tariffs. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 132928–132939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Van den Bergh and E. Delarue and W. D’haeseleer. “DC power flow in unit commitment models”. TME Work. Paper - Energy and Environment, KU Leuven Energy Institute.

- Pozzi, L. Supplementary document to the paper “The Role of Demand Flexibility in Addressing Inc-Dec Gaming in Redispatch Markets”. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16641474, 2024. Accessed on 26 October 2025, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16641474.

- Pereira, M.; Granville, S.; Fampa, M.; Dix, R.; Barroso, L. “Strategic bidding under uncertainty: a binary expansion approach”. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2005, 20, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuny-Amat, J.; McCarl, B. “A Representation and Economic Interpretation of a Two-Level Programming Problem”. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1981, 32, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al., C.G. “The IEEE Reliability Test System-1996. A report prepared by the Reliability Test System Task Force of the Application of Probability Methods Subcommittee”. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 1999, 14, 1010–1020. [CrossRef]

- Ordoudis, C.; Pinson, P.; González, J.M.M.; Zugno, M. “An Updated Version of the IEEE RTS 24-Bus System for Electricity Market and Power System Operation Studies”. Technical University of Denmark, 2016.

- Zugno, M.; Conejo, A. “A robust optimization approach to energy and reserve dispatch in electricity markets”. European J. Oper. Res. 2015, 247, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurobi Python Interface [online]. https://www.gurobi.com/events/modeling-with-the-gurobi-python-interface/. Accessed: 2023-04-03.

- Ruiz, C.; Conejo, A.J. Pool Strategy of a Producer With Endogenous Formation of Locational Marginal Prices. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2009, 24, 1855–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Paper | Model | Examined Network | RD Participants | Time Frame | Time-Coupling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [12] | Analytical | No specific network | Producers | Single-period | No |

| [13,14] | Analytical | 2-node | Producers | Single-period | No |

| [15] | EPEC | No specific network | Producers | Single-period | No |

| [16] | EPEC | 24-node | Producers | Single-period | No |

| [17] | MPEC | 3-node | Producers | Single-period | No |

| This paper | MPEC | 24-node | Prod. and Demand-Side | Multi-period | Yes |

| Producer i | Producer | |

|---|---|---|

| Marginal cost [£/MWh] | 10 | 15 |

| Maximum power [MW] | 1,200 | 1,200 |

| t = 1 | t = 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Marginal benefit [£/MWh] | 10,000 | |

| Upward discomfort cost [£/MWh] | 0.5 | 1 |

| Downward discomfort cost [£/MWh] | 1 | 0.5 |

| Maximum baseline power [MW] | 1,000 | 400 |

| VoLL [£/MWh] | 16,050 | |

| Scenario | Benchmark | Strategic | Strategic + DF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | ||||||

| [MW] | 1,000 | 400 | 0 | 400 | 0 | 400 |

| [MW] | 0 | 0 | 500 | 0 | 420 | 80 |

| [MW] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| [MW] | 0 | 0 | 1,000 | 0 | 1,000 | 0 |

| [MW] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| [MW] | 0 | 0 | 500 | 0 | 500 | 0 |

| [MW] | 1,000 | 400 | 1,000 | 400 | 1,000 | 400 |

| [MW] | – | – | – | – | 80 | 0 |

| [MW] | – | – | – | – | 0 | 80 |

| [£/MW] | 10 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| System costs [£] | ||||||

| DA | 10,000 | 4,000 | 15,000 | 6,000 | 15,000 | 6,000 |

| RD | 0 | 0 | 5,000 | 0 | 3,040 | 1,240 |

| Total | 10,000 | 4,000 | 20,000 | 6,000 | 18,040 | 7,240 |

| Daily total | 14,000 | 26,000 | 25,280 | |||

| Scenario | Benchmark | Strategic | Strategic + DF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | ||||||

| 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 | |

| – | – | 2.50 | – | 2.50 | 1.50 | |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Revenues and costs [£] | ||||||

| Revenue DA | 10,000 | 4,000 | 0 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 |

| Cost DA | 10,000 | 4,000 | 0 | 4,000 | 0 | 4,000 |

| Revenue RD | 0 | 0 | 12,500 | 0 | 10,500 | 1,200 |

| Cost RD | 0 | 0 | 5,000 | 0 | 4,200 | 800 |

| Profit | 0 | 0 | 7,500 | 2,000 | 6,300 | 2,400 |

| Daily profit | 0 | 9,500 | 8,700 | |||

| t | [MW] | [£] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [MW] | [£/MW] | [£] | S | S+DF | S | S+DF | S | S+DF | ||

| 00:00 | – | 0 | 5.47 | 0 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 01:00 | – | 0 | 0.50 | 0 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 02:00 | – | 0 | 0.50 | 0 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 03:00 | – | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 04:00 | – | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 05:00 | – | 0 | 0.50 | 0 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 06:00 | – | 0 | 6.02 | 0 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 07:00 | 0.40 | 95 | 10.52 | -1,518 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 95 | 95 | 1,940 | 2,001 |

| 08:00 | 0.40 | 281 | 10.52 | -4,490 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 281 | 281 | 5,738 | 5,738 |

| 09:00 | 0.43 | 258 | 11.32 | -3,916 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 258 | 258 | 5,134 | 5,268 |

| 10:00 | 0.70 | 281 | 18.52 | -2,242 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 262 | 281 | 5,214 | 5,592 |

| 11:00 | 0.70 | 281 | 18.52 | -2,242 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 281 | 281 | 5,047 | 5,047 |

| 12:00 | 0.78 | 244 | 20.70 | -1,415 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 244 | 244 | 4,382 | 4,382 |

| 13:00 | 0.78 | 244 | 20.70 | -1,415 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 244 | 244 | 4,382 | 4,382 |

| 14:00 | 0.70 | 281 | 18.52 | -2,242 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 281 | 281 | 5,047 | 5,047 |

| 15:00 | 0.70 | 281 | 18.52 | -2,242 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 281 | 281 | 5,047 | 5,592 |

| 16:00 | 0.78 | 281 | 20.70 | -1,630 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 281 | 281 | 5,047 | 5,047 |

| 17:00 | 0.78 | 281 | 20.70 | -1,630 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 281 | 281 | 5,047 | 5,047 |

| 18:00 | 0.78 | 281 | 20.70 | -1,630 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 281 | 281 | 5,047 | 5,047 |

| 19:00 | 0.70 | 281 | 18.52 | -2,242 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 281 | 275 | 5,047 | 5,473 |

| 20:00 | 0.70 | 199 | 18.52 | -1,588 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 199 | 199 | 3,960 | 3,960 |

| 21:00 | 0.43 | 277 | 11.32 | -4,205 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 277 | 277 | 5,513 | 5,513 |

| 22:00 | 0.40 | 281 | 10.52 | -4,490 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 281 | 281 | 5,592 | 5,592 |

| 23:00 | 0.40 | 281 | 10.52 | -4,490 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 281 | 281 | 5,556 | 5,738 |

| Scenario | Benchmark | Strategic | Strategic + DF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Producer 9 results | |||

| DA Profit [£] | 0 | -43,630 | -43,630 |

| RD Profit [£] | 0 | 82,738 | 84,465 |

| Total Profit [£] | 0 | 39,108 | 40,834 |

| System results | |||

| Congestion [MW] | 3,399 | 7,049 | 7,049 |

| DA cost [£] | 748,058 | 706,372 | 706,372 |

| RD cost [£] | 39,284 | 81,228 | 74,981 |

| Total cost [£] | 787,342 | 787,599 | 781,353 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).