Submitted:

15 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

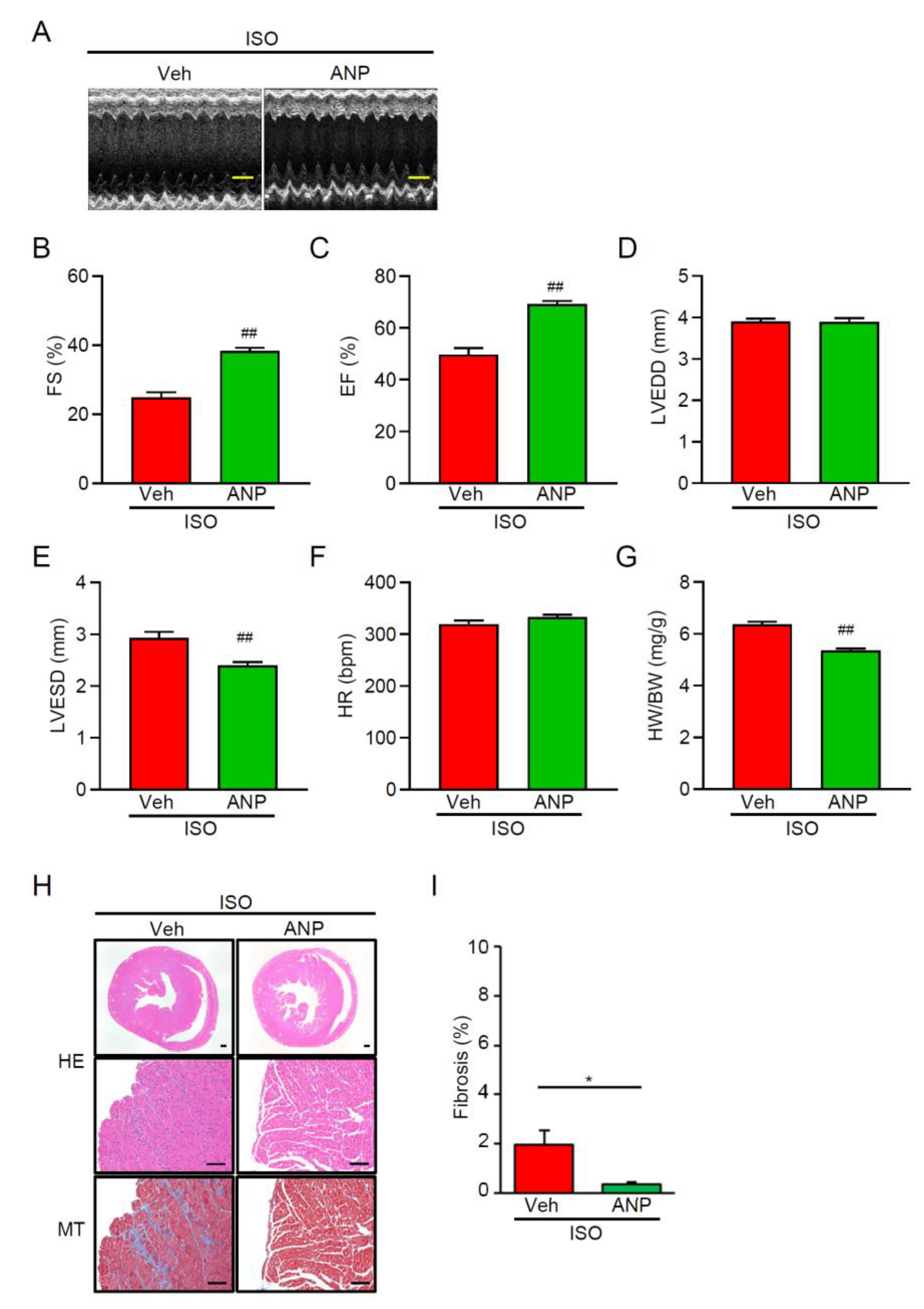

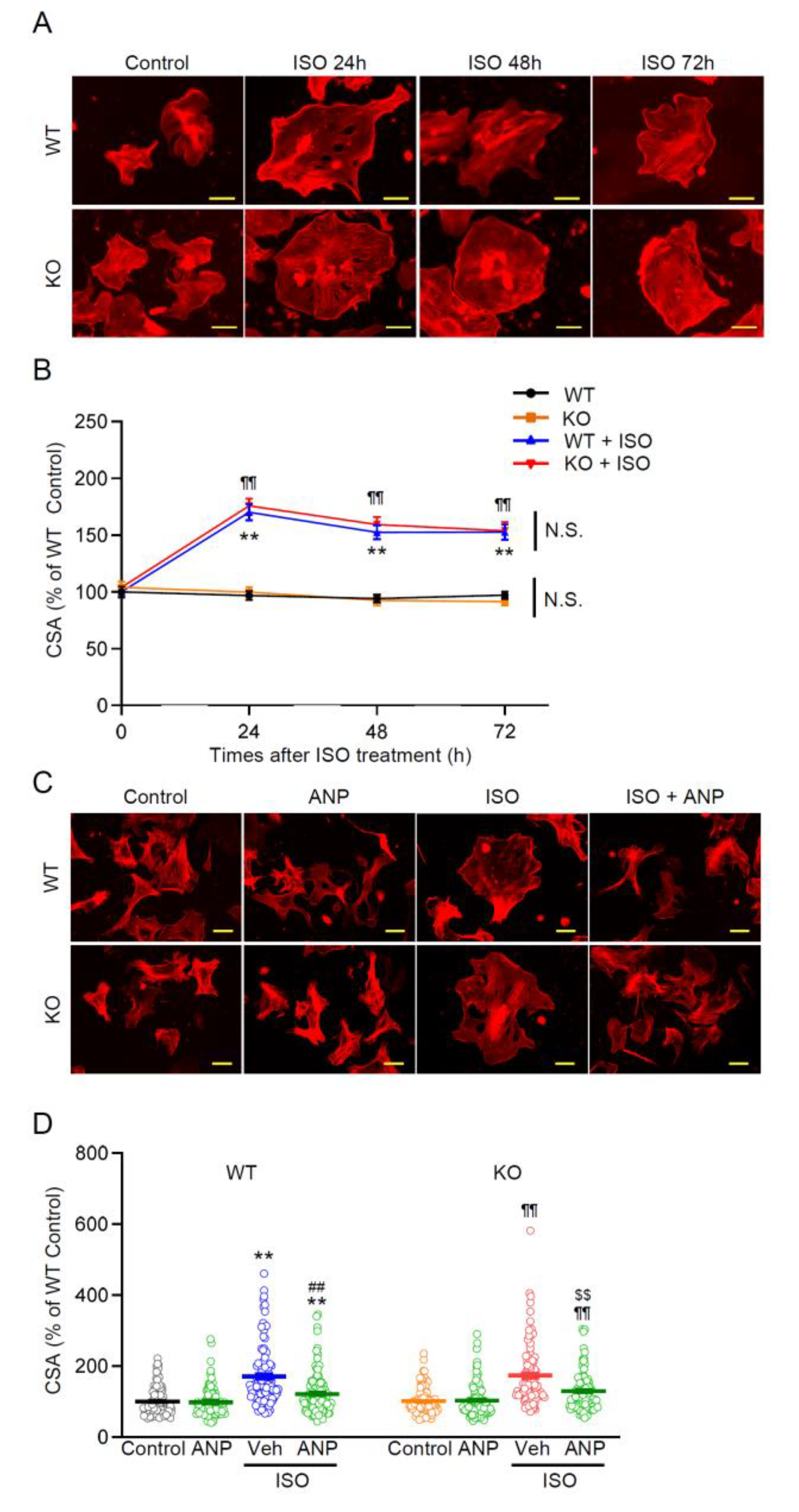

Transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) channel is a Ca2+-permeable, redox-activated cardiac ion channel protective in ischemia–reperfusion, but whether it regulates atrial endocrine output under stress is unclear. We compared how wild-type (WT) and TRPM2 knockout (TRPM2−/−) mice respond to β-adrenergic stress induced by isoproterenol (ISO) using echocardiography, histology, RT-PCR, electrophysiology, Ca2+ imaging, ELISA, and atrial RNA-seq. We detected abundant Trpm2 transcripts in the atria of WT mice, and measured ADP-ribose (ADPr)–evoked currents as well as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)–induced Ca2+ influx characteristic for TRPM2 of WT atrial myocytes; these were absent in TRPM2−/− cells. Under the ISO-induced hypertrophic model, TRPM2−/− mice developed greater cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and systolic dysfunction compared with WT mice. Atrial bulk RNA-seq showed significant induction of Nppa (ANP precursor gene) in WT + ISO, accompanied by higher circulating ANP; TRPM2−/− + ISO showed blunted Nppa and ANP responses. ISO-treated TRPM2−/− mice exhibited more blunt responses, in both Nppa transcripts and circulating ANP levels. Exogenous ANP attenuated ISO-induced dysfunction, hypertrophy, and fibrosis in TRPM2−/− mice, suggesting that TRPM2 is needed for the cardioprotective endocrine response via ANP to control stress-induced β-adrenergic remodeling.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and In Vivo Treatment Protocol

2.2. Echocardiography

2.3. Histology and Morphometry

2.4. Isolation of Atrial and Ventricular Cardiomyocytes

2.5. Whole-Cell Patch-Clamp Electrophysiology

2.8. Calcium Imaging

2.9. Primary Culture of Neonatal Mouse Ventricular Myocytes (NMVMs) and Hypertrophy Assay

2.10. RNA-seq

2.11. RT-PCR and Quantitative PCR

2.12. ELISA for ANP

2.13. Data Presentation and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. TRPM2 Is Enriched and Functionally Active in Atrial myocytes

3.2. TRPM2 Deficiency Aggravates ISO-Induced Systolic Dysfunction, Hypertrophy, and Fibrosis

3.3. β-Adrenergic Stress Evokes an ANP Program in WT Atria That Is Blunted in TRPM2−/−

3.4. Exogenous ANP Mitigates ISO-Induced Dysfunction and Remodeling in TRPM2−/− Mice

3.5. Ventricular Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy Is Induced by ISO and Attenuated by ANP Irrespective of TRPM2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADPr | ADP-ribose |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| ANP | Atrial natriuretic peptide |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| cADPr | Cyclic ADP-ribose |

| CSA | Cross-sectional area |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| EF | Ejection fraction |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FS | Fractional shortening |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| GPCR | G-protein-coupled receptor |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| HEPES | 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid |

| HR | Heart rate |

| HW/BW | Heart weight-to-body weight ratio |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| I/R | Ischemia–reperfusion |

| I–V | Current–voltage |

| ISO | Isoproterenol |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| KO | Knockout |

| LVEDD | Left-ventricular end-diastolic diameter |

| LVESD | Left-ventricular end-systolic diameter |

| MT | Masson’s trichrome |

| NES | Normalized enrichment score |

| NMVMs | Neonatal mouse ventricular myocytes |

| NPR-A/-B/-C | Natriuretic peptide receptor A/B/C (Npr1/Npr2/Npr3) |

| Nppa/Nppb | Genes encoding ANP/BNP precursors |

| NUDT9-H | NUDT9-homology domain |

| PARP/PARG | Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase / glycohydrolase |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| Pyk2 | Proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RT-PCR | Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| SNARE | Soluble NSF Attachment Protein Receptor |

| SRA | Sequence Read Archive |

| SYT | Synaptotagmin |

| TPM | Transcripts per million |

| TRPM2 | Transient receptor potential melastatin-2 |

| VAMP | Vesicle-associated membrane protein |

| Veh | Vehicle |

| WT | Wild type |

| bpm | Beats per minute |

| bp | Base pairs |

| i.p. | Intraperitoneal |

| s.c. | Subcutaneous |

| N.S. | Not significant |

References

- de Lucia, C.; Eguchi, A.; Koch, W.J. New Insights in Cardiac β-Adrenergic Signaling During Heart Failure and Aging. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenkranz, S.; Flesch, M.; Amann, K.; Haeuseler, C.; Kilter, H.; Seeland, U.; Schlüter, K.D.; Böhm, M. Alterations of beta-adrenergic signaling and cardiac hypertrophy in transgenic mice overexpressing TGF-beta(1). Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2002, 283, H1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caturano, A.; Vetrano, E.; Galiero, R.; Salvatore, T.; Docimo, G.; Epifani, R.; Alfano, M.; Sardu, C.; Marfella, R.; Rinaldi, L.; et al. Cardiac Hypertrophy: From Pathophysiological Mechanisms to Heart Failure Development. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2022, 23, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Du, T.; Long, T.; Liao, X.; Dong, Y.; Huang, Z.P. Signaling cascades in the failing heart and emerging therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehat, I.; Molkentin, J.D. Molecular Pathways Underlying Cardiac Remodeling During Pathophysiological Stimulation. Circulation 2010, 122, 2727–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takimoto, E.; Kass, D.A. Role of Oxidative Stress in Cardiac Hypertrophy and Remodeling. Hypertension 2007, 49, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.I.; Griendling, K.K. Regulation of signal transduction by reactive oxygen species in the cardiovascular system. Circ Res 2015, 116, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoyne, J.R.; Mongue-Din, H.; Eaton, P.; Shah, A.M. Redox signaling in cardiac physiology and pathology. Circ Res 2012, 111, 1091–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.F.; Chen, T.; Johnson, S.C.; Szeto, H.; Rabinovitch, P.S. Cardiac aging: from molecular mechanisms to significance in human health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2012, 16, 1492–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui, H.; Kinugawa, S.; Matsushima, S. Oxidative stress and heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011, 301, H2181–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, M.; Madonna, M.; Schiavon, S.; Valenti, V.; Versaci, F.; Zoccai, G.B.; Frati, G.; Sciarretta, S. Cardiovascular Pleiotropic Effects of Natriuretic Peptides. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetze, J.P.; Bruneau, B.G.; Ramos, H.R.; Ogawa, T.; de Bold, M.K.; de Bold, A.J. Cardiac natriuretic peptides. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020, 17, 698–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarzani, R.; Allevi, M.; Di Pentima, C.; Schiavi, P.; Spannella, F.; Giulietti, F. Role of Cardiac Natriuretic Peptides in Heart Structure and Function. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonfria, E.; Marshall, I.C.; Benham, C.D.; Boyfield, I.; Brown, J.D.; Hill, K.; Hughes, J.P.; Skaper, S.D.; McNulty, S. TRPM2 channel opening in response to oxidative stress is dependent on activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Br J Pharmacol 2004, 143, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perraud, A.L.; Takanishi, C.L.; Shen, B.; Kang, S.; Smith, M.K.; Schmitz, C.; Knowles, H.M.; Ferraris, D.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.; et al. Accumulation of free ADP-ribose from mitochondria mediates oxidative stress-induced gating of TRPM2 cation channels. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 6138–6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecquet, C.M.; Malik, A.B. Role of H(2)O(2)-activated TRPM2 calcium channel in oxidant-induced endothelial injury. Thromb Haemost 2009, 101, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numata, T.; Sato, K.; Christmann, J.; Marx, R.; Mori, Y.; Okada, Y.; Wehner, F. The ΔC splice-variant of TRPM2 is the hypertonicity-induced cation channel in HeLa cells, and the ecto-enzyme CD38 mediates its activation. J Physiol 2012, 590, 1121–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.A.; Wang, J.; Hirschler-Laszkiewicz, I.; Gao, E.; Song, J.; Zhang, X.Q.; Koch, W.J.; Madesh, M.; Mallilankaraman, K.; Gu, T.; et al. The second member of transient receptor potential-melastatin channel family protects hearts from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2013, 304, H1010–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.; Qu, C.; Rao, Z.; Wu, D.; Zhao, J. Bidirectional regulation mechanism of TRPM2 channel: role in oxidative stress, inflammation and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1391355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, W.; Zabrzyński, J.; Gagat, M.; Grzanka, A. The Role of TRPM2 in Endothelial Function and Dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Wakamori, M.; Ishii, M.; Maeno, E.; Nishida, M.; Yoshida, T.; Yamada, H.; Shimizu, S.; Mori, E.; Kudoh, J.; et al. LTRPC2 Ca2+-permeable channel activated by changes in redox status confers susceptibility to cell death. Mol Cell 2002, 9, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perraud, A.L.; Fleig, A.; Dunn, C.A.; Bagley, L.A.; Launay, P.; Schmitz, C.; Stokes, A.J.; Zhu, Q.; Bessman, M.J.; Penner, R.; et al. ADP-ribose gating of the calcium-permeable LTRPC2 channel revealed by Nudix motif homology. Nature 2001, 411, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, N.E.; Miller, B.A.; Wang, J.; Elrod, J.W.; Rajan, S.; Gao, E.; Song, J.; Zhang, X.Q.; Hirschler-Laszkiewicz, I.; Shanmughapriya, S.; et al. Ca2+ entry via Trpm2 is essential for cardiac myocyte bioenergetics maintenance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2015, 308, H637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.A.; Hoffman, N.E.; Merali, S.; Zhang, X.Q.; Wang, J.; Rajan, S.; Shanmughapriya, S.; Gao, E.; Barrero, C.A.; Mallilankaraman, K.; et al. TRPM2 channels protect against cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury: role of mitochondria. J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 7615–7629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, B.A.; Wang, J.; Song, J.; Zhang, X.Q.; Hirschler-Laszkiewicz, I.; Shanmughapriya, S.; Tomar, D.; Rajan, S.; Feldman, A.M.; Madesh, M.; et al. Trpm2 enhances physiological bioenergetics and protects against pathological oxidative cardiac injury: Role of Pyk2 phosphorylation. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 15048–15060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Wang, P.; Wei, H.; Yan, J.; Zhang, D.; Qian, Y.; Guo, B. Interleukin(IL)-37 attenuates isoproterenol (ISO)-induced cardiac hypertrophy by suppressing JAK2/STAT3-signaling associated inflammation and oxidative stress. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 142, 113134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroi, T.; Wajima, T.; Negoro, T.; Ishii, M.; Nakano, Y.; Kiuchi, Y.; Mori, Y.; Shimizu, S. Neutrophil TRPM2 channels are implicated in the exacerbation of myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovascular Research 2012, 97, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlito, M.; Fulton, W.B.; Zauher, M.A.; Marbán, E.; Steenbergen, C.; Lowenstein, C.J. VAMP-1, VAMP-2, and syntaxin-4 regulate ANP release from cardiac myocytes. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2010, 49, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, C.G.; Miller, D.F.; Giovannucci, D.R. Identification, localization and interaction of SNARE proteins in atrial cardiac myocytes. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2006, 40, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essandoh, K.; Eramo, G.A.; Subramani, A.; Brody, M.J. Rab3gap1 palmitoylation cycling modulates cardiomyocyte exocytosis and atrial natriuretic peptide release. Biophys J 2025, 124, 1843–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essandoh, K.; Subramani, A.; Koripella, S.; Brody, M.J. The Rab3 GTPase cycle modulates cardiomyocyte exocytosis and atrial natriuretic peptide release. Biophys J 2025, 124, 1856–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Chen, S.C.; Cheng, T.; Humphreys, M.H.; Gardner, D.G. Ligand-dependent regulation of NPR-A gene expression in inner medullary collecting duct cells. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 1998, 275, F119–F125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Togashi, K.; Hara, Y.; Tominaga, T.; Higashi, T.; Konishi, Y.; Mori, Y.; Tominaga, M. TRPM2 activation by cyclic ADP-ribose at body temperature is involved in insulin secretion. Embo j 2006, 25, 1804–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajan, S.; Shalygin, A.; Gudermann, T.; Chubanov, V.; Dietrich, A. TRPM2 channels are essential for regulation of cytokine production in lung interstitial macrophages. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2024, 239, e31322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, Y.; Nakao, K.; Nishimura, K.; Sugawara, A.; Okumura, K.; Obata, K.; Sonoda, R.; Ban, T.; Yasue, H.; Imura, H. Clinical application of atrial natriuretic polypeptide in patients with congestive heart failure: beneficial effects on left ventricular function. Circulation 1987, 76, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwa, M.; Seino, Y.; Nomachi, Y.; Matsuki, S.; Funahashi, K. Multicenter prospective investigation on efficacy and safety of carperitide for acute heart failure in the ‘real world’ of therapy. Circ J 2005, 69, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Bai, S.; Zhen, Y.; Li, D.; Yang, P.; Chen, Y.; Hong, L.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of 1-Hour Infusion of Recombinant Human Atrial Natriuretic Peptide in Patients With Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: A Phase III, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Trial. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016, 95, e2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Rath, S.; Waqas, S.A.; Alam, U.; Ali, M.A.; Khadim, S.; Akbar, U.A.; Laghari, M.A.; Collins, P.; Ahmed, R. Effect of carperitide on mortality and ANP levels in acute heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Heart Journal Plus: Cardiology Research and Practice 2025, 59, 100624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsue, Y.; Kagiyama, N.; Yoshida, K.; Kume, T.; Okura, H.; Suzuki, M.; Matsumura, A.; Yoshida, K.; Hashimoto, Y. Carperitide Is Associated With Increased In-Hospital Mortality in Acute Heart Failure: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. J Card Fail 2015, 21, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, T.; Iwakami, N.; Nakai, M.; Nishimura, K.; Sumita, Y.; Mizuno, A.; Tsutsui, H.; Ogawa, H.; Anzai, T. Effect of intravenous carperitide versus nitrates as first-line vasodilators on in-hospital outcomes in hospitalized patients with acute heart failure: Insight from a nationwide claim-based database. Int J Cardiol 2019, 280, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerico, A.; Giannoni, A.; Vittorini, S.; Passino, C. Thirty years of the heart as an endocrine organ: physiological role and clinical utility of cardiac natriuretic hormones. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011, 301, H12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpe, M.; Gallo, G.; Rubattu, S. Endocrine functions of the heart: from bench to bedside. Eur Heart J 2023, 44, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malko, P.; Jiang, L.H. TRPM2 channel-mediated cell death: An important mechanism linking oxidative stress-inducing pathological factors to associated pathological conditions. Redox Biol 2020, 37, 101755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, K.Y.; Yu, P.L.; Liu, C.H.; Luo, J.H.; Yang, W. Detrimental or beneficial: the role of TRPM2 in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2016, 37, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, X.; Fan, Y.; Hua, N.; Li, D.; Jin, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, P.; et al. TRPM2 Mediates Hepatic Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury via Ca(2+)-Induced Mitochondrial Lipid Peroxidation through Increasing ALOX12 Expression. Research (Wash D C) 2023, 6, 0159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).