1. Introduction

Currently, the incidence and mortality rates of lung cancer are increasing year by year. According to data from the American Cancer Society, approximately 14% of newly diagnosed malignant tumors are lung cancer. Among all malignant tumors, lung cancer ranks highest in incidence and mortality. As pulmonary nodules are closely related to lung cancer and may be an early feature of lung cancer, their detection and diagnosis are of great significance for early lung cancer diagnosis and can serve as an important reference [1,2].

Computed Tomography (CT) is commonly used to evaluate pulmonary nodules, requiring physicians to have specialized medical imaging knowledge and clinical experience. However, due to the differences among individual physicians, Computer-Aided Diagnosis (CAD) technology has been widely applied in recent years as an auxiliary medical tool, providing relatively objective evaluation metrics to assist doctors in making diagnoses [3].

Early research methods often relied on feature extraction techniques, which involved identifying Regions of Interest (ROI) in the images and analyzing the characteristics of the nodules based on shape, grayscale, texture, etc. Manually extracting features is time-consuming and labor-intensive [4]. With the rapid development of machine learning, deep learning algorithms represented by convolutional neural networks have been widely adopted. One approach is the two-stage detection algorithm based on candidate regions, such as RCNN; another is the one-stage detection algorithm, such as the YOLO series [5,6]. One method uses the YOLO detection framework to detect CT nodules and predicts multiple bounding boxes using a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), followed by evaluation on the LIDC-IDRI dataset (Lung Image Database Consortium), achieving a sensitivity of 89%. Currently, CNN, YOLO, FCN, R-CNN [7–9], and other networks are often used for training on different datasets to extract features from target datasets.

Transfer learning methods used at present can achieve relatively good results, but due to the large domain gap between the source and target datasets, there is still room for improvement in feature extraction. Therefore, this paper proposes an improved deep neural network model based on GoogLeNet Inception V3 to recognize pulmonary nodules.

The main work of this paper is to design a feature fusion layer and optimize related parameters to better extract features from the target dataset.

2. Related Work

Recent advancements in deep learning have significantly enhanced medical image analysis.Works that emphasize the integration of clinical and imaging data to enhance diagnostic performance. For instance, joint modeling of medical images and clinical text facilitates early detection of chronic conditions like diabetes [10]. Similarly, leveraging Transformer-CNN fusion for skin lesion segmentation [11] and temporal graph attention for EEG anomaly detection [12] shows the potential of deep neural architectures in specialized diagnostic contexts.

Research has also emphasized predictive modeling in clinical settings, particularly for chronic disease progression and health risk assessment. Structure-aware temporal models offer accurate progression prediction [13], while federated frameworks are enabling privacy-preserving risk analysis on electronic health records [14]. Furthermore, the integration of deep learning and natural language processing (NLP) for structuring electronic medical records enhances clinical workflow efficiency [15].

In the broader context of cloud-based AI applications, reinforcement learning plays a vital role in dynamic resource management and anomaly detection. Multi-agent reinforcement learning strategies [16] and temporal anomaly detection models [17] have demonstrated robust scalability. Personalized modeling for federated anomaly detection [18] and collaborative data mining across distributed systems [19] further contribute to intelligent cloud system design. Moreover, cross-domain transfer learning techniques [20] and privacy-aware model fine-tuning mechanisms [21] highlight efforts to bridge domain gaps and ensure model generalizability and security.

Concurrently, the integration of large language models (LLMs) with retrieval-augmented mechanisms and knowledge graphs has gained momentum. Innovations in question answering systems [22], adapter-based knowledge injection [23], and knowledge graph-infused reasoning models [24] exemplify this trend. Additionally, uncertainty-aware summarization techniques [25], prompt engineering for controllable abstraction [26], and contrastive learning for secure alignment [27] underscore the growing intersection of language modeling and deep learning robustness.

In terms of enterprise and infrastructure intelligence, anomaly detection in ETL workflows using autoencoders [28] and knowledge-driven threat identification frameworks in IoT environments [29] expand the applicability of deep learning techniques. Reinforcement learning has also been harnessed for optimizing microservice orchestration, including scheduling [30], adaptive HCI strategies [31], graph-based service routing [32], and rate limiting in distributed systems [33].

These diverse yet interconnected works collectively inform the development of robust pulmonary image recognition systems. Methodologies such as transfer learning, federated modeling, multimodal fusion, and reinforcement optimization are especially relevant for enhancing feature extraction and generalization across heterogeneous datasets like LUNA16, as adopted in our proposed RGIV3 model.

3. Dataset

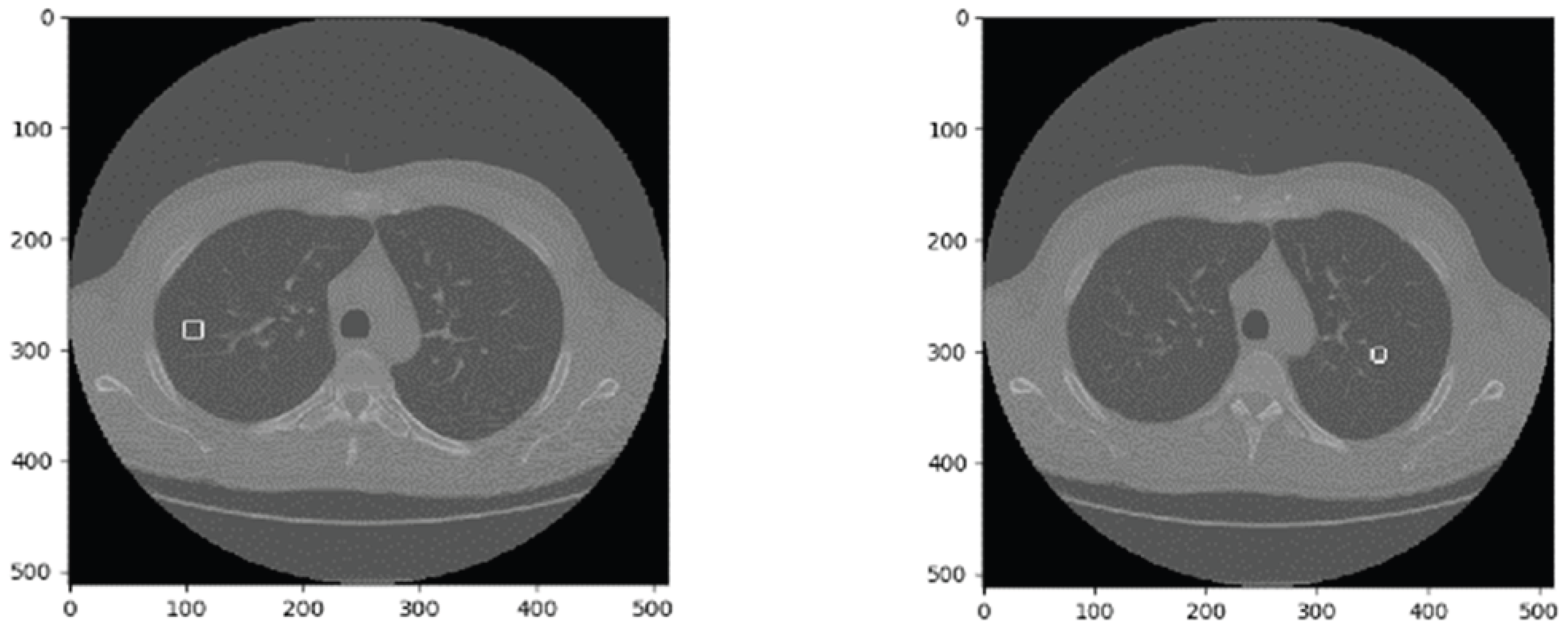

This paper uses the LUNA16 dataset. As a publicly available lung nodule dataset and a subset of LIDC-IDRI [34], LUNA16 includes CT images from 888 patients, divided into 10 subsets for storage. Each image set consists of mhd and raw files, where the mhd file provides basic image information, and the raw file stores pixel data. An example CT image is shown in

Figure 1.

4. Improved Pulmonary Nodule Recognition Model

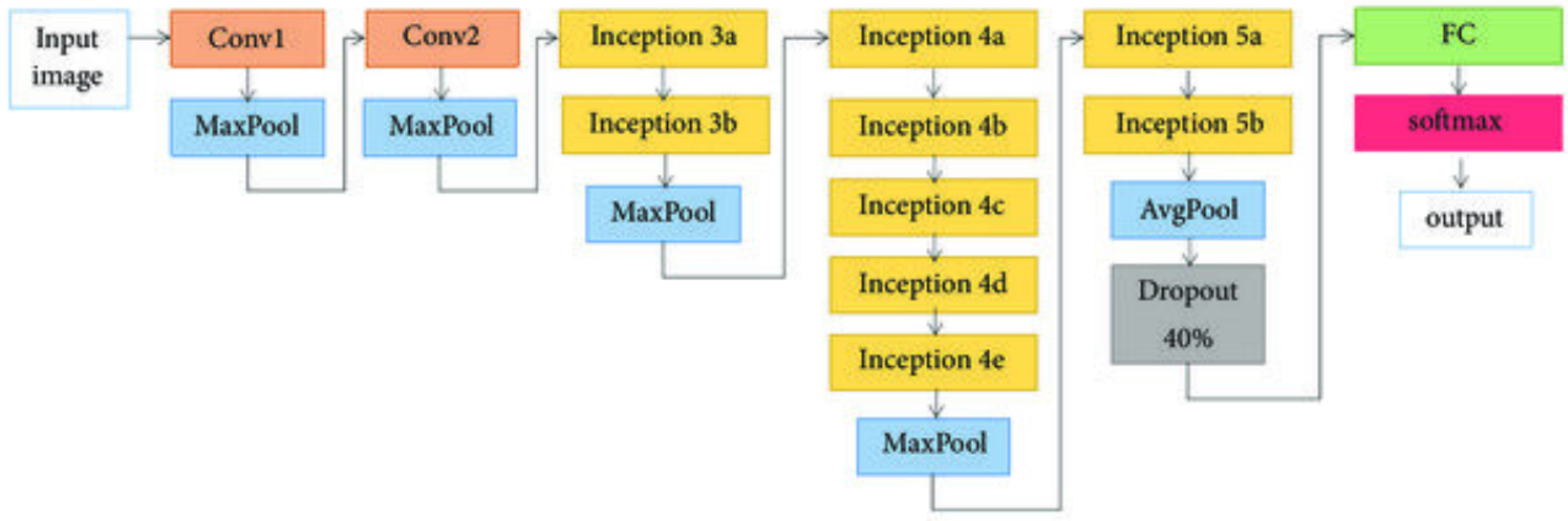

4.1. GooLeNet Network Algorithm

In 2012, the GooLeNet network was proposed [35]. Compared with networks such as AlexNet and VGG, GooLeNet features a deeper network structure and fewer parameters (see

Table 1). By adjusting the network structure (see

Figure 2) and designing Inception layers, GooLeNet significantly reduces the number of parameters, thereby improving training efficiency.

4.2. Improved RGIV3 Network Structure Design

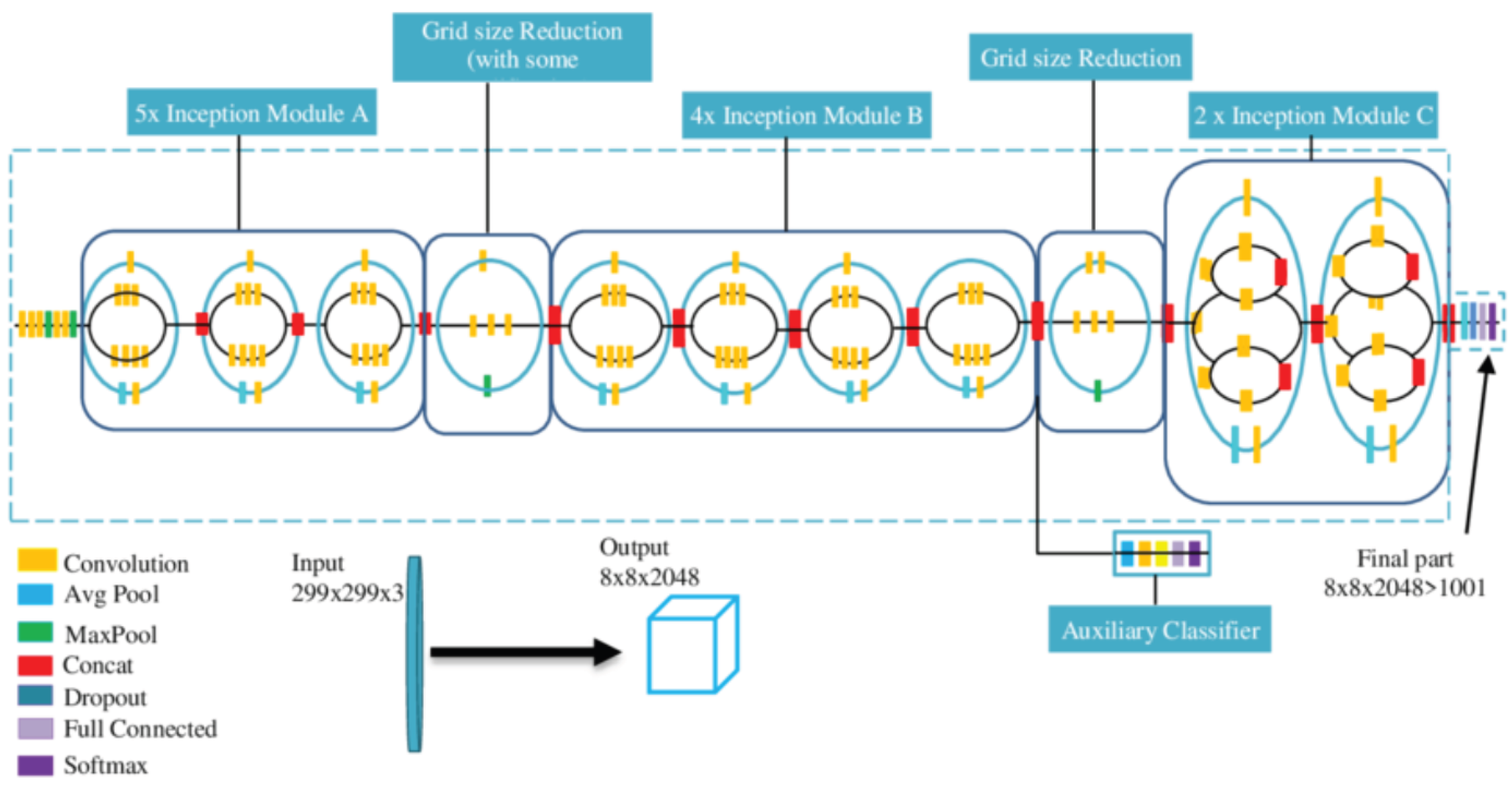

GooLeNet Inception V3 [36,37] is a model trained on the ImageNet dataset. However, due to the large domain gap between ImageNet and the LUNA16 dataset used in this paper, directly applying it yields poor results. Therefore, a fusion layer is designed to reduce the negative impact of the domain gap between the two datasets. This fusion layer combines feature information learned by the network in a non-linear way, improving the learning of image features.

The fusion layer is composed of three fully connected layers and one dropout layer, as shown in

Figure 3. This layer is then combined with the GooLeNet Inception V3 network, where the original GooLeNet Inception V3 is referred to as GIV3, and the combined network is named RGIV3.

According to experience, the number of neurons is chosen from 1024, 512, 256, and 128, and the dropout rate is selected from 0.4, 0.5, and 0.6. To determine the optimal configuration, this paper conducts experiments on different combinations of neuron numbers and dropout rates—a total of 30 combinations—using accuracy as the selection criterion. The experimental results are shown in

Table 2. Based on the results, the selected configuration is 1024 and 512 neurons with a dropout rate of 0.5.

Due to the limited number of samples in the target dataset, newly trained models are prone to overfitting. In the experiment, pretrained weights from large-scale datasets such as ImageNet were used as initialization parameters, and fine-tuning was conducted with a relatively low learning rate.

4.3. Network Weight Update Method

The Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) method is used to update the weights by minimizing the loss function along the direction of the negative gradient of the learning rate [38]. The update formula is as follows:

In this formula,

represents the weight after the

-th iteration;

is the weight after the

i-th iteration;

is the accumulated gradient. The formula is:

Here, denotes the accumulated gradient after the -th iteration; is the accumulated gradient after the i-th iteration; is the momentum coefficient; L represents the current learning rate; is the gradient of the loss function.

5. Experiments and Results Analysis

5.1. Dataset Preprocessing

The original LUNA16 data consists of image data (.raw) and annotation data (.mhd). Since neural networks cannot directly read this image format, the mhd-format images are converted into the commonly used BMP format. Through this conversion, each CT slice corresponds to a BMP image with the same slice count as RGB images, and each image displays the full CT scan content. From the annotation files, the position and properties of the nodules can be obtained. With the position and slice depth, the exact coordinates and slices can be quickly located [38]. When patients undergo CT scans, different body postures may cause image flipping, so the images need to be adjusted based on annotation data to align properly, and the coordinate annotations also need to be corrected.

Due to the small dataset size, this study expands the dataset through data augmentation. Supervised data augmentation techniques are used to enhance the BMP-format images, and a low learning rate is adopted to prevent overfitting.

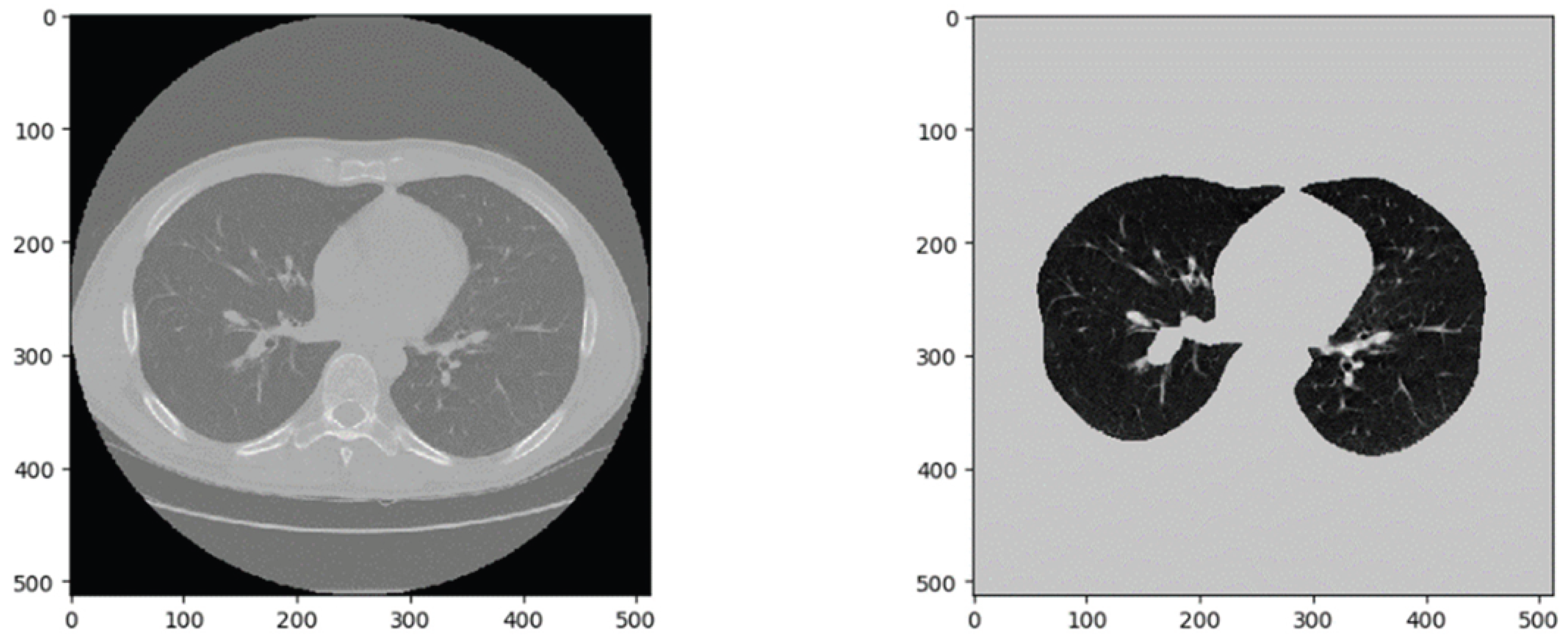

Pulmonary nodules typically appear at the ends of bronchial and vascular branches. In CT images, these are the black circular regions representing air in the lungs. This study aims to identify pulmonary nodules, so it is necessary to segment the actual lung region and exclude the outer lung fields, which may introduce noise into the network [39].

Figure 4 shows a slice from the LUNA16 dataset. After binarization, corrosion, and dilation operations, the lung parenchyma and outer lung field can be separated for further processing [40].

5.2. Experimental Procedure

The experiments were conducted under Windows 10 system using an Intel Core i5-6200U @ 2.30GHz CPU. TensorFlow framework and the slim module were adopted, with Python version 3.6.

In the experimental process, 750 patients’ CT data were used for training, and 150 patients’ data were used for testing. A total of 2000 pulmonary nodule images and 2000 healthy tissue images were extracted. After data augmentation, the dataset expanded to 5000 nodule images and 5000 healthy images. All images were resized to 330 × 330. The data were split as follows: 80% training, 20% testing; 70% training, 30% testing; and 60% training, 40% testing. Each group was trained with the same loss function for fair comparison. Among them, the 80% group was trained using the slim model for 2776 steps, reducing the loss to 0.38 and achieving an accuracy of 88.8%. Other group results are shown in Table 4.

In the experiment, the designed RGIV3 network was trained on the training set and validated on the test set. To avoid falling into local minima, a gradually decreasing learning rate was used, reducing the rate every 200 iterations.

5.3. Experimental Results and Analysis

According to the experimental results, True Positive (TP), True Negative (TN), False Positive (FP), and False Negative (FN) were used to evaluate model performance [14-16]. Three evaluation metrics were selected: Accuracy (Acc), Sensitivity (Sen), and Specificity (Spe), calculated as follows:

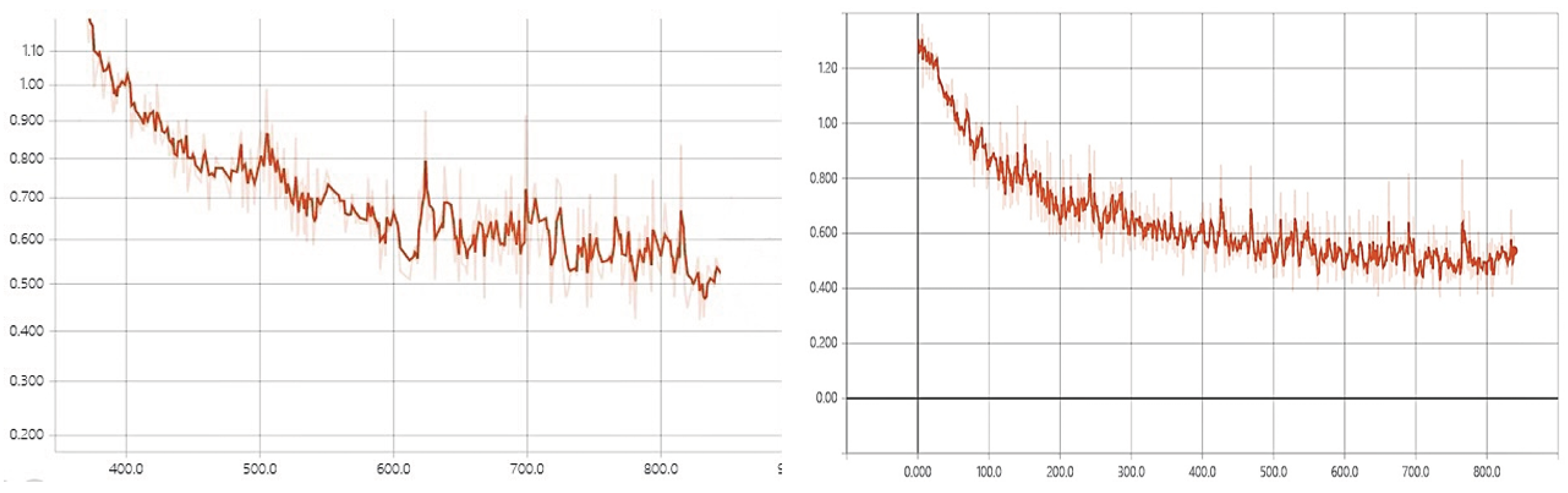

Accuracy reflects the consistency between predictions and ground truth. Sensitivity reflects the model’s ability to detect nodules, while specificity indicates the model’s ability to distinguish non-nodule images. The training processes of GIV3 and RGIV3 are shown in

Figure 5. According to

Figure 5, RGIV3 has a faster convergence speed and more stable performance. Combined with the accuracy metric, the improved RGIV3 model achieves better results on the dataset.

When using 80% of the data as the training set and 20% as the test set, the performance comparison of different models is shown in

Table 3.

As shown in Table 3, the improved model achieves an accuracy of 88.80% and a sensitivity of 87.15%, which are 2.72% and 2.19% higher than those of the traditional GIV model, respectively. This indicates a relatively better recognition performance.

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the improved RGIV3 model, experiments were conducted under different ratios of training and testing sets. The results are shown in

Table 4.

According to Table 4 and the training process analysis, the improved RGIV3 model outperforms the original GIV model in terms of recognition performance. Under the 80%, 70%, and 60% data ratios, RGIV3 consistently achieves better recognition results than GIV3, with faster convergence and more stable performance.

6. Conclusion

This paper adopts an improved neural network model to detect pulmonary nodules in part of the LUNA16 dataset. By combining the GIV3 network with the designed feature fusion layer, the network’s feature extraction capability is enhanced, which to some extent alleviates the poor transfer learning performance caused by large domain differences between source and target datasets.

In comparative experiments, the proposed model demonstrates better recognition performance compared to other existing models. Due to the relatively small scale of the dataset and the existence of overfitting, data augmentation and fine-tuning using low learning rates were employed, which effectively mitigated the problem.

In future research, computational features can be associated with semantic features to provide quantitative evaluation for pulmonary nodules and offer diagnostic references for clinicians.

References

- S. H. Liang, M. Hu, Y. Ma, L. Yang, J. Chen, L. Lou, C. Chen and Y. Xiao, “Performance of deep-learning solutions on lung nodule malignancy classification: a systematic review,” Life, vol. 13, no. 9, article 1911, 2023. [CrossRef]

- I. Marinakis, K. Karampidis and G. Papadourakis, “Pulmonary nodule detection, segmentation and classification using deep learning: a comprehensive literature review,” BioMedInformatics, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 2043–2106, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Mahajan, U. Agarwal, R. Agrawal, A. Venkatesh, S. Shukla, K. S. S. Bharadwaj, M. L. V. Apparao, V. Pawar and V. Poonia, “Deep learning-based pulmonary nodule screening: a narrative review,” [Journal Name], online ahead of print, 2024. [CrossRef]

- “3D deep learning for detecting pulmonary nodules in CT scans,” PMC, vol. ..., 2018.

- “Deep learning in pulmonary nodule detection and segmentation,” [Journal], 2023.

- “Deep learning for the detection of benign and malignant pulmonary nodules,” Nature Communications, 2023.

- G. Francis and J. P. Ko, “Pulmonary nodules: detection, assessment, and CAD,” American Journal of Roentgenology, vol. 191, no. 4, pp. 1057–1069, 2008.

- D. Liu, S. Zhu, B. Liu, et al., “Improvement of CT target scanning quality for pulmonary nodules by PDCA management method,” Mathematical Problems in Engineering, vol. 2021, no. 6, pp. 1–9, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Litjens, T. Kooi, B. Ehteshami Bejnordi, A. A. Setio, F. Ciompi, M. Ghafoorian, J. A. W. M. van der Laak, B. van Ginneken and C. I. Sánchez, “A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis,” arXiv:1702.05747, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zi and X. Deng, “Joint modeling of medical images and clinical text for early diabetes risk detection,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 4, no. 7, 2025.

- X. Wang, X. Zhang and X. Wang, “Deep skin lesion segmentation with Transformer-CNN fusion: toward intelligent skin cancer analysis,” arXiv:2508.14509, 2025.

- X. Zhang and Q. Wang, “EEG anomaly detection using temporal graph attention for clinical applications,” Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 4, no. 7, 2025.

- J. Hu, B. Zhang, T. Xu, H. Yang and M. Gao, “Structure-aware temporal modeling for chronic disease progression prediction,” arXiv:2508.14942, 2025.

- R. Hao, W. C. Chang, J. Hu and M. Gao, “Federated learning-driven health risk prediction on electronic health records under privacy constraints,” 2025.

- N. Qi, “Deep learning and NLP methods for unified summarization and structuring of electronic medical records,” Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 4, no. 3, 2024.

- B. Fang and D. Gao, “Collaborative multi-agent reinforcement learning approach for elastic cloud resource scaling,” arXiv:2507.00550, 2025.

- L. Lian, Y. Li, S. Han, R. Meng, S. Wang and M. Wang, “Artificial intelligence-based multiscale temporal modeling for anomaly detection in cloud services,” arXiv:2508.14503, 2025.

- Y. Wang, H. Liu, N. Long and G. Yao, “Federated anomaly detection for multi-tenant cloud platforms with personalized modeling,” arXiv:2508.10255, 2025.

- M. Wang, T. Kang, L. Dai, H. Yang, J. Du and C. Liu, “Scalable multi-party collaborative data mining based on federated learning,” 2025.

- Y. Zhou, “Self-supervised transfer learning with shared encoders for cross-domain cloud optimization,” 2025.

- Y. Li, “Task-aware differential privacy and modular structural perturbation for secure fine-tuning of large language models,” Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 4, no. 7, 2024.

- Y. Sun, R. Zhang, R. Meng, L. Lian, H. Wang and X. Quan, “Fusion-based retrieval-augmented generation for complex question answering with LLMs,” in Proc. CISAT, pp. 116–120, July 2025.

- H. Zheng, L. Zhu, W. Cui, R. Pan, X. Yan and Y. Xing, “Selective knowledge injection via adapter modules in large-scale language models,” 2025.

- W. Zhang, Y. Tian, X. Meng, M. Wang and J. Du, “Knowledge graph-infused fine-tuning for structured reasoning in large language models,” arXiv:2508.14427, 2025.

- S. Pan and D. Wu, “Trustworthy summarization via uncertainty quantification and risk awareness in large language models,” 2025.

- X. Song, Y. Liu, Y. Luan, J. Guo and X. Guo, “Controllable abstraction in summary generation for large language models via prompt engineering,” arXiv:2510.15436, 2025.

- J. Zheng, H. Zhang, X. Yan, R. Hao and C. Peng, “Contrastive knowledge transfer and robust optimization for secure alignment of large language models,” arXiv:2510.27077, 2025.

- X. Chen, S. U. Gadgil, K. Gao, Y. Hu and C. Nie, “Deep learning approach to anomaly detection in enterprise ETL processes with autoencoders,” arXiv:2511.00462, 2025.

- L. Yan, Q. Wang and C. Liu, “Semantic knowledge graph framework for intelligent threat identification in IoT,” 2025.

- R. Zhang, “AI-driven multi-agent scheduling and service quality optimization in microservice systems,” Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 5, no. 8, 2025.

- R. Liu, Y. Zhuang and R. Zhang, “Adaptive human-computer interaction strategies through reinforcement learning in complex environments,” arXiv:2510.27058, 2025.

- C. Hu, Z. Cheng, D. Wu, Y. Wang, F. Liu and Z. Qiu, “Structural generalization for microservice routing using graph neural networks,” arXiv:2510.15210, 2025.

- N. Lyu, Y. Wang, Z. Cheng, Q. Zhang and F. Chen, “Multi-objective adaptive rate limiting in microservices using deep reinforcement learning,” arXiv:2511.03279, 2025.

- R. Siddiqi, “Deep Learning for Pneumonia Detection in Chest X-ray Images,” Images, vol. 10, no. 8, p. 176, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Szegedy, W. Liu, Y. Jia, et al., “Going deeper with convolutions,” in IEEE Computer Society, pp. 1–9, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ohno, M. Nishio, H. Koyama, et al., “Dynamic contrast–enhanced CT and MRI for pulmonary nodule assessment,” American Journal of Roentgenology, vol. 202, no. 3, pp. 515–529, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Souto, P. G. Tahoces, J. J. Suarez Cuenca, et al., “Automatic detection of pulmonary nodules on computed tomography: a preliminary study,” Radiologia, vol. 50, no. 5, pp. 387–392, 2008.

- C. Zhang, J. Li, J. Huang, et al., “Computed tomography image under convolutional neural network deep learning algorithm in pulmonary nodule detection and lung function examination,” Journal of Healthcare Engineering, Article ID: 3417285, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. H. Lee and J. S. Jwo, “Automatic segmentation for pulmonary nodules in CT images based on multifractal analysis,” IET Image Processing, vol. 14, no. 7, pp. 1347–1353, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Itouji, M. Kono, S. Adachi, et al., “The role of CT and MR imaging in the diagnosis of lung cancer,” Gan to Kagaku Ryoho Cancer & Chemotherapy, vol. 24, suppl. 3, pp. 353–358, 1997.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).