Introduction

Hemoglobin (Hb) is the protein contained in red blood cells that is responsible for delivery of oxygen to the tissues, and when the hemoglobin level is low, the patient has anemia1. Anemia is a condition in which the red blood cell count is decreased, impairing the body’s ability to meet the oxygen needs of tissues becoming a public health problem2 where women are some of the most affected; in 2019, the World Health Organization reported around 30% of women 15-49 years of age worldwide had anemia3. The WHO-defined hemoglobin (Hb) cut-offs, specific to age, sex, and pregnancy status, are most widely used to diagnose anemia, with the threshold being <120 g/L for non-pregnant and <110 g/L for pregnant women of 15–49 years of age4. Anemia also has a high association within low-income countries, notably in Africa, where, in 2019, an estimated 106 million women were affected by anemia5.

Among pregnant women, maternal anemia can cause symptoms such as headaches and fatigue along with more severe cases, hemoglobin levels <6g/dL, causing a possibility of more dangerous effects secondary to decreased tissue oxygenation6. Pregnant and lactating women are especially susceptible to decline in hemoglobin7, thus, it is important to analyze all risk factors that may have an impact on this. Beyond this, low maternal hemoglobin levels during pregnancy can also cause lasting effects such as fetal deaths6,8 and an increased risk of limited cognitive development for infants after birth9. There are many risk factors that have been associated with the prevalence of maternal anemia and maternal hemoglobin decline such as education10, income11, and diet12, however, research on the association between maternal hemoglobin and environmental factors is in its infancy.

Only a handful of studies have shown the relationship between environmental pollutants and maternal hemoglobin or anemia. One study showed that exposure levels to PM10, SO2, and CO for one and two years were significantly associated with decreased hemoglobin concentrations (all p < 0.05)13. In this study, exposure levels to PM10, for instance, had an OR of 1.039 [95% CI : 1.001–1.079], highlighting the link between air pollutants and decreased hemoglobin13. Additionally, carbon monoxide (CO) exposure during a two-year period was closely related to anemia OR = 1.046 [95% CI: 1.004–1.091]13. On the other hand, a study involving particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) found no association with anemia prevalence during the one year exposure period13, yet other studies have found a negative association with hemoglobin levels which may contribute to maternal hemoglobin decline14,15. Fine toxic pollutants such as PM2.5, primarily from vehicle emissions and industrial activities, are more likely to travel into and deposit on the surface of the deeper parts of the lung, which can induce tissue damage16. Furthermore, a previous study found that PM2.5 particles can lead to a biological response due to motor emissions that can penetrate deep into the lungs, enter the bloodstream, and induce systemic inflammation17,18. Addressing these environmental factors and their impact on hemoglobin is crucial for improving maternal health outcomes and developing effective public health interventions.

This study aims to assess regional differences in the association between PM2.5 and maternal hemoglobin levels across Africa.

Methods

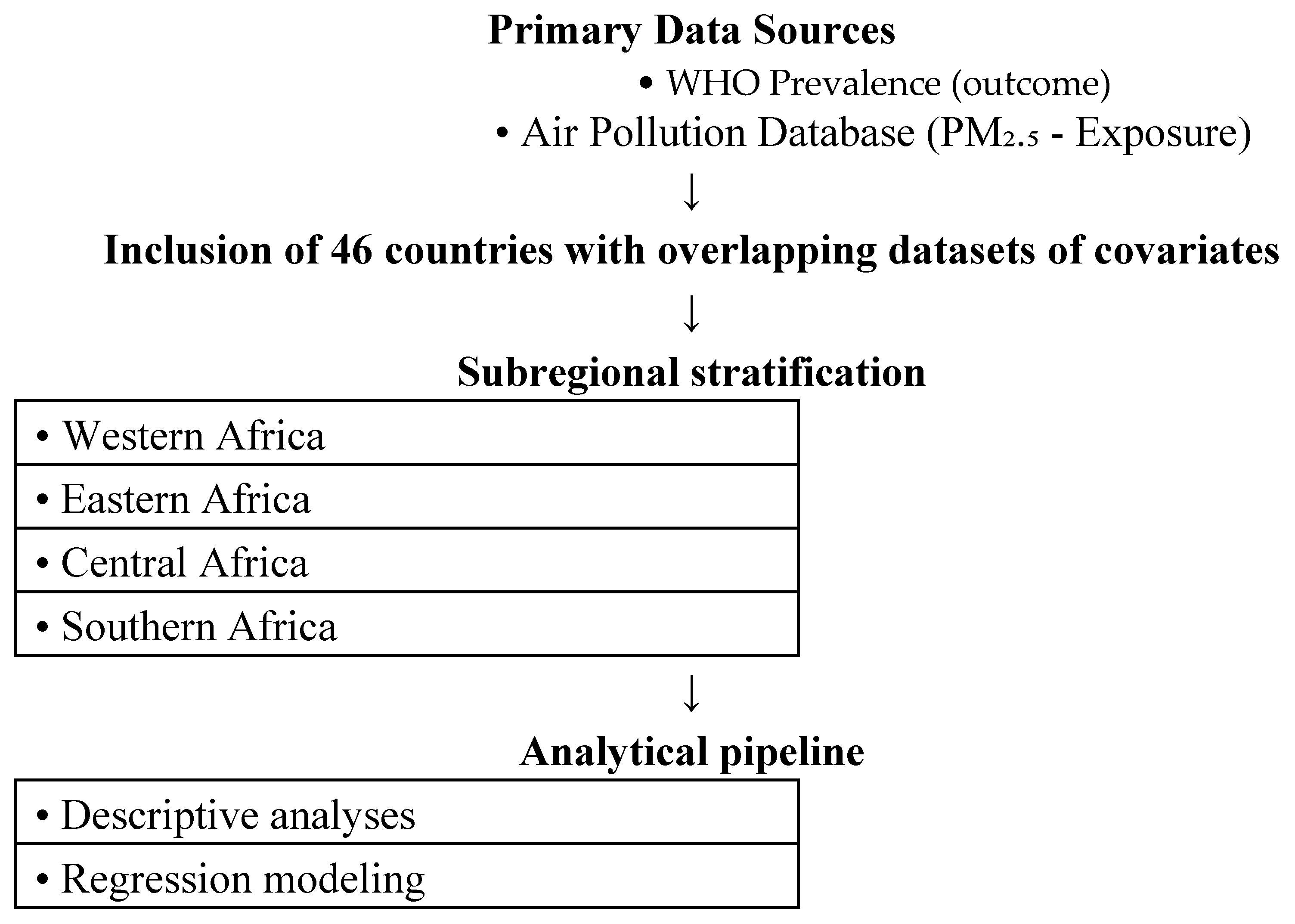

This is a population-based study for Africa from 2000-2019. Data for the annual mean prevalence hemoglobin (in grams per litre) of reproductive women between the ages of 15-49 years for 43 African nations is the outcome and was obtained from the World Health Organization (WHO). Data flow is shown in

Figure 1. North Africa was excluded because WHO-reported hemoglobin data for women of reproductive age were incomplete for most North African countries between 2000 to 2019. This was noted in the revised Methods section. Aside from our primary outcome, exposure data for country-specific annual mean particulate matter 2.5 (PM

2.5) from 2000-2019 was obtained from World Bank:

https://www.stateofglobalair.org/data/#/air/plot.

We included covariate data on country-specific annual mean air pollution (specifically household air pollutants as percentage), cereal yield (in tonnes per hectare), gross domestic product (GDP), prevalence of reproductive women with anemia (moderate levels), low body-mass index (<18.5 kg/m2) of whole population, and annual trend.

We modelled the region-specific associations between the annual prevalence of reproductive women hemoglobin levels and annual PM2.5 using generalized linear model, specifically negative binomial regression using autocorrelation order 1 (i.e. AR1). This is because the outcome’s variance was much greater than its mean, leading to overdispersion of data. Model coefficients were exponentiated to be interpreted as rate ratios (RR) for each 10 μg/m3 rise in pollution levels. 95% confidence intervals were evaluated at P<0.05 using Student’s two-sided t-tests. Microsoft Excel (V.2021) and RStudio (V.4.1.1) were used for computation, analyses and figure composition.

Results

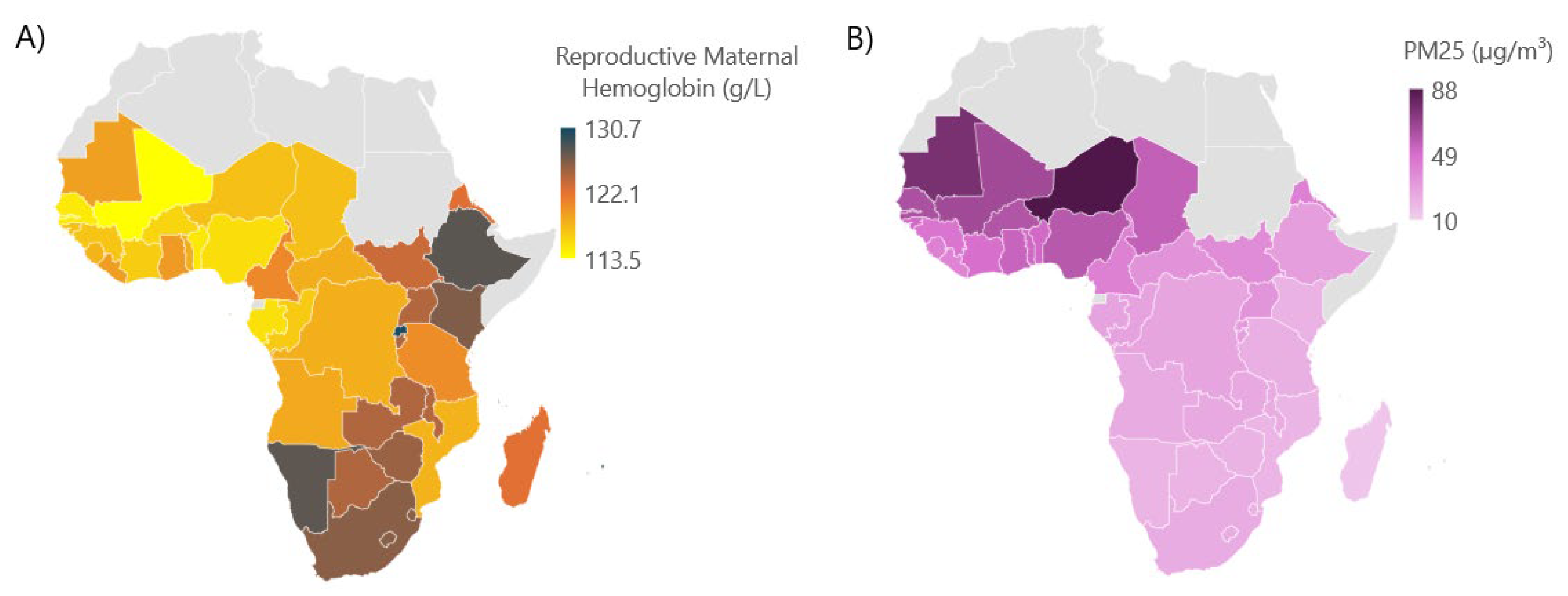

Over the twenty-year study period from 2000 to 2019, across 43 countries within four regions of Africa, the overall average prevalence of hemoglobin among reproductive-age women was 120.8 g/L. Geographically, this prevalence was lowest over Western Africa and highest over Southern Africa (

Figure 2A). Annual mean PM

2.5 levels followed a similar geographic pattern, peaking in Western Africa throughout the study period (

Figure 2B). The association between average annual reproductive maternal hemoglobin (modeled on the log scale) and the set of explanatory variables was analyzed separately for each region: West, East, Central, and South. Similarly, annual mean PM

2.5 concentrations were highest in West Africa, followed by Central Africa, with Eastern and Southern Africa showing lower levels throughout 2000-2019, showcasing a possible inverse correlation between the hemoglobin levels among reproductive women in Sub-Saharan Africa and annual mean PM

2.5 concentrations (

Figure 2B). Additionally, the actual mean maternal hemoglobin concentration was 116.7 g/L in Western Africa, 124.3 g/L in Eastern Africa, 117.9 g/L in Central Africa, and 125.9 g/L in Southern Africa.

Our models suggest that for each annual 10 μg/m3 rise in PM2.5 the RR for reproductive maternal hemoglobin found was no association for Western, Eastern, and Southern Africa, yet only Central Africa had the significant results [RR 0.999 (P=0.035)].

The model for the West region indicated that PM2.5 was not a statistically significant predictor of maternal hemoglobin (RR=1.000, P=0.70). In the East region, PM2.5 also lacked a significant association (RR=1.000, P=0.91). This region, however, identified several significant predictors, including a positive association with agricultural cereal yield per hectare (RR=1.001, P=0.0002) and the GDP (constant with 2015 US dollar) was also found to be significant predictor (P=0.015).

Finally, the South region model did not show a significant association for PM2.5, yet we did find a significant positive predictor for indoor house air pollution (P=0.02) and a rising trend in anemia prevalence annually (P=0.017).

The main findings (noted from

Table 1) suggests that countries of Central African regions had a negative association between prevalence of maternal reproductive women and PM

2.5 from 2000-2019.

Discussion

The results of our study found that only Central Africa is statistically significant in the effect of PM2.5 on maternal hemoglobin levels, whereas other regions were insignificant, hence suggesting regional differences in Africa. In a past study that analyzed the pregnancy conditions of Chinese women [20-45 years, n=7932] delivering between 2015-2018, it was found that an increase in PM2.5 concentration for all pregnant women (mean: 69.56 μg/m3, standard deviation: 15.24 μg/m3) by one interquartile range increase (19.37 μg/m3) was associated with a decrease in hemoglobin levels in multiparous women (mean age: 32.77±3.75 years, n=2609), but not for primiparous women (mean age: 28.78±3.25 years, n=5323)14. Exposure to PM2.5 was associated with decreased hemoglobin in the third trimester of multiparous women, but not detrimental to the degree of being associated with anemia14.

The link between PM2.5 exposure and decreased maternal hemoglobin levels is believed to be driven by inflammation as a biological response14. PM2.5 particles can deeply penetrate the lungs through motor emissions, enter the bloodstream, and trigger systemic inflammation, leading to oxidative stress and vascular dysfunction17,18. Pregnant and lactating women are especially vulnerable to hemoglobin decline, which has severe consequences for maternal health, and infant development, including impacts on cognitive function7. Additionally, a previous study also shows that decreased hemoglobin levels are linked to cardiovascular disease in pregnant women, which further worsens the effect of PM2.519,20. These factors underscore the importance of addressing PM2.5 in strategies aimed at improving hemoglobin levels, particularly among maternal women in regions with poor air quality, such as Africa.

Several epidemiologic studies have confirmed that PM2.5 harms pregnant women and leads to more severe impacts on hemoglobin levels13. It is confirmed based on availability of data that a mother with low hemoglobin was at risk of delivering a newborn with stunted growth21. Additionally, in Africa, a lack of dietary and malnutrition variety during pregnancy doubles the odds of developing maternal anemia, which in turn leads to low child birth weight and therefore low hemoglobin levels22.

The association between PM2.5 and maternal hemoglobin levels observed in this study is limited by confounding factors, such as exposure to other air pollutants like PM1, PM10, and NO2, which have also been linked to decreased hemoglobin levels12. Since these pollutants are formed from emissions such as those from motor vehicles, it is difficult to isolate PM2.5 from other pollutants that may also affect hemoglobin levels16. Moreover, socioeconomic status is another confounding factor that can influence both exposure to air pollution and access to healthcare, which further affects the relationship between PM2.5 and hemoglobin levels23. The lack of nutrition education and iron rich food has been associated with decreased hemoglobin levels, which we were not able to control for24. This study does not fully reflect the true prevalence or severity of low maternal hemoglobin, and interventions may be less effective due to African areas with limited healthcare access25.

Nevertheless, this study adds value to the literature that focuses on a specific region (i.e. Africa) - discussing the association between PM2.5 and maternal hemoglobin11. This study highlights the regional variance and indicates that PM2.5 is negatively associated with hemoglobin levels in maternal women. The study further helps to confirm our hypothesis that PM2.5 increases the likelihood of maternal anemia. This is a concern since rising levels of PM2.5 are exacerbated with further climate changes leading to clinical implications or reduced hemoglobin levels26.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that PM2.5 exposure poses a region-specific risk factor for maternal hemoglobin decline and highlighted regional effects of PM2.5 on maternal hemoglobin. This advances the current understanding of the relationship between environmental pollutants, particularly PM 2.5, to maternal hemoglobin levels, with a focus on regional dynamics throughout Sub-Saharan Africa. Our results underscore the need for a targeted, regionally informed strategy to mitigate the impact of PM2.5 pollution on maternal health, broadened the scope to other low-income regions to determine whether this hypothesis holds true globally and addressing PM2.5 exposure should be prioritized as a key element of maternal health strategies, particularly in regions burdened by environmental degradation and limited health infrastructure. If left unaddressed, the burden of reduced hemoglobin levels in women of reproductive age will likely persist and potentially worsen, exacerbating maternal mortality rates and perpetuating cycles of poor health in vulnerable communities. Without timely and region-specific interventions, these disparities may pose significant challenges to future public health efforts and policy implementation.

Additionally, the study can be used to collaborate with specific African regions’ governments to create considerable and lasting regulations. These regulations may decrease the prevalence of anemia among maternal women, reducing the chances of maternal health complications that arise in response to exposure from PM2.5.

Author Contributions

Dr. Muhammad A. Saeed: Original Idea, Paper Review, Administration, Data Review, Writing of draft, Final Review Harris Khokhar: Data Collection; Writing of draft, Data Review, Administration, Final review Mohammad R. Saeed: Data Collection, Writing of draft, Data Review, Administration, Final review. Adeena Zaidi: Data Collection; Writing of draft, Data Review, Administration, Final review Dr. Binish Arif Sultan: Final review Sarim Karimi: Writing of draft, Ammar Muhammad: Writing of draft, Final review Dr. Haris Majeed: Original Idea, Paper Review, Data Collection, Data Review, Writing of draft, , Final Review Bhargavi Rao: Writing of draft, Final review.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were Not applicable for this study due to due to the use of publicly available, anonymized data that does not involve direct interaction with human participants.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data are available from the World Health Organization (WHO) and can be accessed at

https://www.who.int/data. Access to specific datasets may require registration or approval from the WHO.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Billett HH. Hemoglobin and Hematocrit. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, eds. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd ed. Boston: Butterworths; 1990.

- Owais A, Merritt C, Lee C, Bhutta ZA. Anemia among Women of Reproductive Age: An Overview of Global Burden, Trends, Determinants, and Drivers of Progress in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Nutrients. 2021 Aug 10;13(8):2745. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Anaemia [Internet]. www.who.int. World Health Organisation; 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/anaemia#tab=tab_1.

- WHO. Haemoglobin Concentrations for the Diagnosis of Anaemia and Assessment of Severity. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2011.

- World Health Organization. Anaemia [Internet]. www.who.int. 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/anaemia.

- Sifakis S, Pharmakide G. Anemia in Pregnancy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006 Jan 25;900(1):125–36. [CrossRef]

- Basrowi RW, Zulfiqqar A, Sitorus NL. Anemia in Breastfeeding Women and Its Impact on Offspring's Health in Indonesia: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2024;16(9):1285. Published 2024 Apr 25. [CrossRef]

- Young MF, Oaks BM, Tandon S, Martorell R, Dewey KG, Wendt AS. Maternal hemoglobin concentrations across pregnancy and maternal and child health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2019 Apr 17;1450(1):47-68. [CrossRef]

- Mireku MO, Davidson LL, Koura GK, et al. Prenatal Hemoglobin Levels and Early Cognitive and Motor Functions of One-Year-Old Children. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):e76-e83. [CrossRef]

- Stephen G, Mgongo M, Hussein Hashim T, Katanga J, Stray-Pedersen B, Msuya SE. Anaemia in Pregnancy: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Adverse Perinatal Outcomes in Northern Tanzania. Anemia. 2018;2018:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Abd Rahman R, Idris IB, Isa ZM, Rahman RA, Mahdy ZA. The Prevalence and Risk Factors of Iron Deficiency Anemia Among Pregnant Women in Malaysia: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2022 Apr 15;9.

- Gibore NS, Ngowi AF, Munyogwa MJ, Ali MM. Dietary Habits Associated with Anemia in Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care Services. Current Developments in Nutrition. 2020 Dec 11;5(1). [CrossRef]

- Hwang J, Kim HJ. Association of ambient air pollution with hemoglobin levels and anemia in the general population of Korean adults. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):988. Published 2024 Apr 9. [CrossRef]

- Xie G, Yue J, Yang W, et al. Effects of PM2.5 and its constituents on hemoglobin during the third trimester in pregnant women. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022;29(23):35193-35203. [CrossRef]

- He C, Xie L, Gu L, Yan H, Feng S, Zeng C, et al. Anemia is associated with long-term exposure to PM2.5 and its components: a large population-based study in Southwest China. Therapeutic Advances in Hematology. 2023 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Sep 8];14.

- Inhalable Particulate Matter and Health (PM2.5 and PM10) | California Air Resources Board [Internet]. ww2.arb.ca.gov. Available from: https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/resources/inhalable-particulate-matter-and-health#:~:text=5%3F-.

- Miller MR. Oxidative stress and the cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;151:69-87. [CrossRef]

- Thangavel P, Park D, Lee YC. Recent Insights into Particulate Matter (PM2.5)-Mediated Toxicity in Humans: An Overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(12):7511. Published 2022 Jun 19. [CrossRef]

- Lanser L, Fuchs D, Scharnagl H, et al. Anemia of Chronic Disease in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:666638. Published 2021 Aug 12. [CrossRef]

- Basith S, Manavalan B, Shin TH, et al. The Impact of Fine Particulate Matter 2.5 on the Cardiovascular System: A Review of the Invisible Killer. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2022;12(15):2656. Published 2022 Aug 2. [CrossRef]

- Nadhiroh SR, Micheala F, Tung SEH, Kustiawan TC. Association between maternal anemia and stunting in infants and children aged 0–60 months: A systematic literature review. Nutrition [Internet]. 2023 Nov 1;115:112094. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0899900723001235#:~:.

- Seid A, Desta Dugassa Fufa, Misrak Weldeyohannes, Tadesse Z, Selamawit Lake Fenta, Zebenay Workneh Bitew, et al. Inadequate dietary diversity during pregnancy increases the risk of maternal anemia and low birth weight in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Science and Nutrition. 2023 May 6;11(7):3706–17. [CrossRef]

- Alaba OA, Chiwire P, Siya A, et al. Socio-Economic Inequalities in the Double Burden of Malnutrition among under-Five Children: Evidence from 10 Selected Sub-Saharan African Countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(8):5489. Published 2023 Apr 12. [CrossRef]

- Sunuwar DR, Sangroula RK, Shakya NS, Yadav R, Chaudhary NK, Pradhan PMS. Effect of nutrition education on hemoglobin level in pregnant women: A quasi-experimental study. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213982. Published 2019 Mar 21. [CrossRef]

- Musa SM, Haruna UA, Manirambona E, et al. Paucity of Health Data in Africa: An Obstacle to Digital Health Implementation and Evidence-Based Practice. Public Health Rev. 2023;44:1605821. Published 2023 Aug 29. [CrossRef]

- Shi L, Liu P, Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. Climate Penalty. Environmental Epidemiology. 2019 Oct;3:365.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).