1. Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a multifactorial disease characterized by articular cartilage degradation, formation of bone osteophytes, subchondral bone sclerosis, and, in advanced stages, the development of subchondral cysts [

1]. The most common clinical manifestation of knee OA is persistent or intermittent chronic pain > 3 months, which typically correlates with the extent of joint destruction [

2,

3].

Since usually drug treatment could be used, e.g., non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [

4] with or without topical compounds (e.g., corticosteroids or hyaluronic acid) [

5,

6,

7] their use could be related to the development of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) or drug-interactions [

8,

9].

Advances in molecular medicine suggest that targeting specific cellular pathways may alter the course of chronic diseases. In this context, compounds with antioxidants and anti-inflammatory properties hold potential as therapeutic agents in the management of various pathological conditions [

10,

11,

12].

International guidelines suggest that dietary supplements may represent a first-line treatment option for patients with mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis; however, their safety should be carefully evaluated, especially in patients receiving multiple medications [

13].

Several nutrients used in the management of knee OA exhibit anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Among these, chondroitin sulfate and alpha-lipoic acid have been reported to play a significant role in managing this chronic condition. Two systematic reviews have demonstrated the efficacy of glucosamine and chondroitin compared to active controls and placebo [

14,

15]. Additionally, alpha-lipoic acid has been proposed as a potential therapeutic agent due to its antioxidant activity [

16].

Thia pilot study serves as a proof of concept for a fixed combination of chondroitin sulfate, alpha-lipoic acid, astaxanthin, lycopene, escin, omega-3 fatty acids, including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), to evaluate its effects on symptoms of mild to moderate knee pain in patients with knee OA. Effective symptom reduction may significantly improve knee mobility and overall quality of life in these patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

In this observational, single-center, open-label study, patients of both sexes with a diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis and referred to the pain room of the Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacovigilance Unit of the “R Dulbecco” University Hospital of Catanzaro from January 2025 to September 2025, were enrolled. During this period, treatment with the fixed combination of a new nutraceutical (1 tablet daily for 3 months; Diaco Biofarmaceutici, Trieste, Italy) was added to their common therapy. At the beginning of the study, patients were asked not to change their usual dietary habits or any other medications used for their comorbidities.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

To ensure participant privacy, each subject was assigned a numerical identification code generated by a physician who was not involved in the study. All participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose and procedures and provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki, with full compliance with Italian privacy regulations. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee (Authorization No. 120/2018; Clinical trial registration: NCT05509075).

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients were enrolled according to the following inclusion criteria:

Age ≥ 18 years, of either sex.

Diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis (OA).

Ability to comply with the study protocol and provision of written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria included:

a) Age < 18 years.

b) Pregnancy or breastfeeding, or women of childbearing potential not using adequate contraception.

c) Known allergy or hypersensitivity to the study treatment or rescue medications.

d) Advanced-stage malignancies.

e) Moderate to severe renal impairment (glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min).

f) Severe hepatic or cardiac dysfunction.

g) Severe asthma.

h) History of drug or alcohol abuse.

i) Any condition or comorbidity that, in the investigator’s judgment, could pose a risk to the participant or interfere with the evaluation of efficacy and safety.

j) Participation in another clinical trial or receipt of an investigational drug within 30 days before screening.

2.4. Experimental Protocol

Clinical data were collected at two main time points: at enrollment (T0, prior to treatment initiation) and at the end of the study (T3, three months after T0). All patients presented with chronic pain and were receiving NSAIDs as needed; therefore, baseline data at T0 served as the control condition.

Questionnaires were administered by the study’s medical staff. Given the open-label design, patient confidentiality was maintained through the assignment of unique numerical codes by a physician not involved in the study. This ensured privacy while enabling accurate data analysis in compliance with ethical research standards.

At both T0 and T3, detailed medical history was collected, physical examinations were performed, and standardized questionnaires were completed. Pain intensity and functional status were assessed using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) and the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS). Throughout the study, any systemic or local adverse drug reactions (ADRs) were monitored and evaluated using the Naranjo scale to determine causality.

Prior to enrolling in this study, all patients had received systemic treatment with NSAIDs, without achieving any clinical improvement. Consequently, the pretreatment period (T0) was used as the control for comparison with follow-up assessments.

2.4.1. Questionnaires

Validated instruments were employed, consistent with previous studies:

36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): Assesses health-related quality of life across eight domains. Higher scores indicate better perceived health status, whereas lower scores reflect poorer quality of life.<sup>17,18</sup>

Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (Zung SAS): A 20-item questionnaire assessing anxiety, categorized as normal (0–44), moderate (45–59), or severe (60–80).<sup>19</sup>

Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (Zung SDS): A 20-item instrument measuring depressive symptoms, classified as normal (20–49), mild (50–59), moderate (60–69), or severe (70–80).<sup>20</sup>

Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale (Naranjo Scale): A 10-item tool used to standardize the assessment of ADR causality. Scores classify ADRs as doubtful (≤0), possible (1–4), probable (5–8), or definite (≥9).<sup>21,22</sup>

Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): Evaluates knee pain, symptoms (e.g., swelling, range of motion), activities of daily living, sport/recreation function, and knee-related quality of life. Scores range from 0 (extreme problems) to 100 (no problems).

2.4.2. Clinical Tests

Clinical assessments were performed according to established protocols:

Timed Up and Go (TUG) Test: Evaluates functional mobility and fall risk by timing how long it takes for a patient to rise from a chair, walk three meters, turn, return, and sit down. Shorter times indicate better mobility, whereas times ≥13.5 seconds indicate increased fall risk.

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS): Measures pain intensity on a 10-cm line, where 0 represents “no pain” and 10 represents “worst imaginable pain.” The onset of pain during the TUG test was also recorded.

2.5. Efficacy End Points

Primary endpoint:

Statistically significant improvement (p < 0.05) in KOOS scores at follow-up visits (T1–T3) compared with baseline (T0).

Secondary endpoints:

Statistically significant improvement (p < 0.05) in VAS scores at T1–T3 compared with T0.

Statistically significant improvement (p < 0.05) in overall SF-36 scores at T1–T3 compared with T0.

Statistically significant changes (p < 0.05) in mood disorder scores (Zung SAS and SDS) between T1–T3 and T0.

2.6. Safety End-Points

ADRs related to the nutraceutical treatment were recorded throughout the study using the Naranjo scale. ADRs leading to participant withdrawal were also documented.

2.7. Nutraceutical Formulation

Each tablet contained a fixed combination of chondroitin sulfate, α-lipoic acid, astaxanthin, lycopene, escin, omega-3 fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) (Diaco Biofarmaceutici, Trieste, Italy;

Table 1).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables with a Gaussian distribution were described as mean ± standard deviation (SD), whereas categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Comparisons of continuous variables were performed using the Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test.

Multivariate analyses were adjusted for potential confounders, including age, sex, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, educational level, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, and concomitant drug use. Correlations between continuous variables were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

For repeated measures, the nonparametric Friedman test was used, followed by post hoc pairwise comparisons with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Data are presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise specified. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Because no prior data were available for this novel compound, a formal power calculation could not be performed; therefore, this investigation was designed as a pilot study.

3. Results

3.1. Population

In this study, we enrolled 50 patients (20 men and 30 women) with a mean age of 63.6 ± 11.4 years (range: 26–88 years) and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 26.9 ± 3.7 kg/m

2 (

Table 2). All patients had a history of knee OA unresponsive to typical or atypical NSAIDs (Table3) and provided written informed consent. Among the study population, 11 patients (22%) reported a history of articular trauma, while the remaining 39 patients (78%) had knee OA attributed to chronic degeneration. No significant differences in age, sex, or BMI were found between these two groups (p > 0.05). Additionally, bilateral knee OA was documented in 28 patients (56%), with no significant differences in its prevalence by sex (women: n = 18, 45%; men: n = 10, 50%), age, or BMI.

All the enrolled patients completed the course of treatment.

Table 3.

Typical and atypical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs used before the enrollment. Data are expressed as number (percentage). Student’s t-test was used for statistical evaluation. **P<0.01.

Table 3.

Typical and atypical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs used before the enrollment. Data are expressed as number (percentage). Student’s t-test was used for statistical evaluation. **P<0.01.

| |

Women (n = 30) |

Men (n = 20) |

| Ibuprofen |

8 (26.6) |

6 (30) |

| Ketoprofen |

2 (6.7) |

2 (10) ** |

| Diclofenac |

7 (23.3) |

5 (25) |

| Celecoxib |

5 (16.7)** |

2 (10) |

| Etoricoxib |

3 (10) |

2 (10) |

| Acetaminophen |

5 (16.7) |

3 (15) |

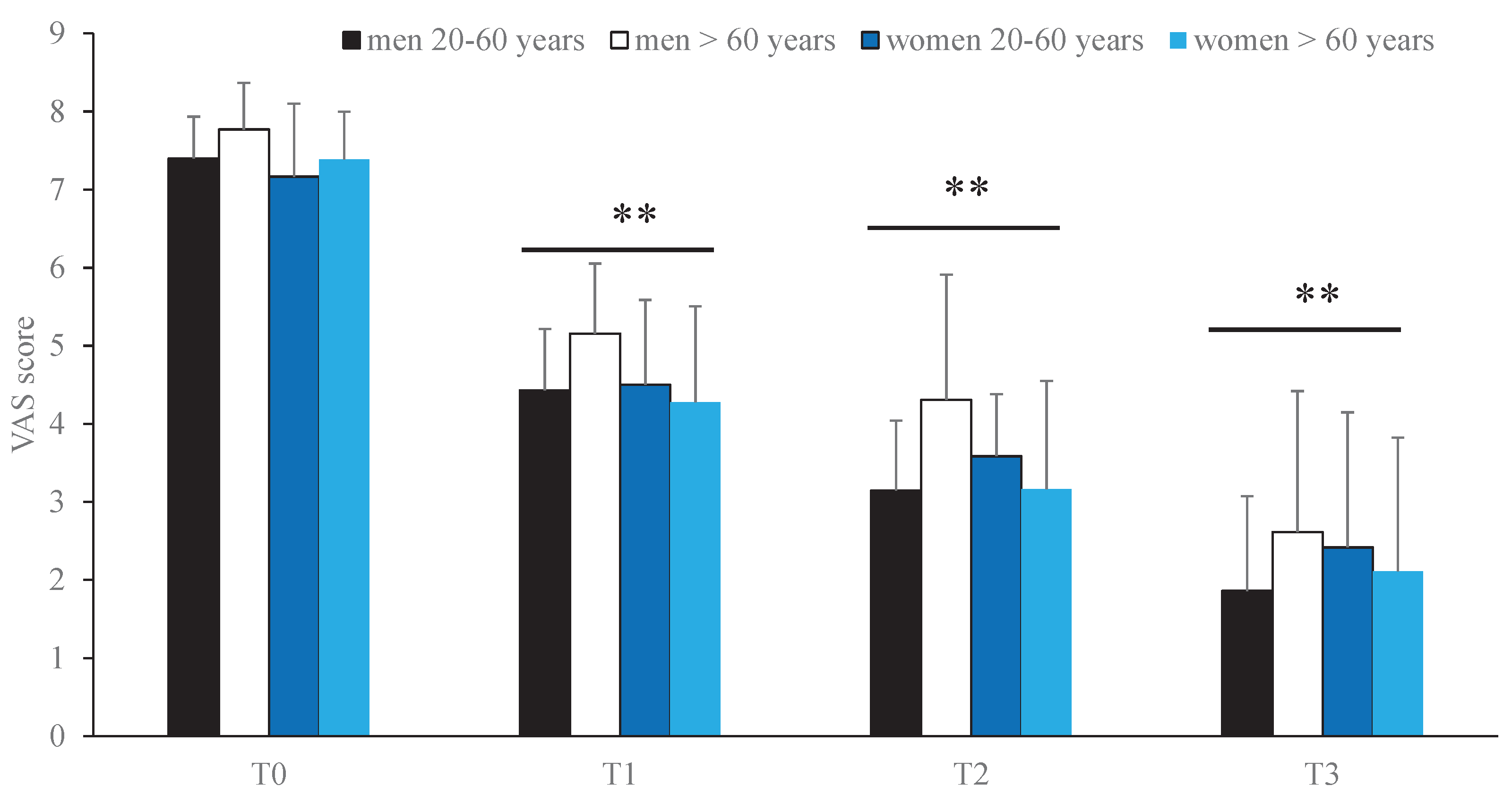

3.2. Effects on Pain

At baseline (T0), the mean Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score was 7.5 ± 0.6 (men: 7.7 ± 0.6; women: 7.3 ± 0.8), the mean Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) was 43.8 ± 12.65, and the mean Timed Up and Go (TUG) test time was 4.8 ± 2.2 seconds. All patients exhibited a positive walking test after 3 minutes (

Table 4). At T0, Pearson correlation analysis revealed no significant associations between pain intensity and sex, age, or body mass index (BMI) (

Table 5).

During the follow-up period (T1–T3), a significant, time-dependent improvement in clinical symptoms was observed (p < 0.001;

Table 6). Specifically, when patients were stratified by age group (20–60 years and > 60 years), oral treatment with the nutraceutical combination resulted in a statistically significant reduction in VAS scores over time (p < 0.01) (

Figure 1).

3.3. Effects on Quality of Life

At T3 (3 months after the beginning of the nutrients). SF-36 questionnaire score revealed a time-related significant improvement in the quality of life (P < 0.01) (

Table 7), without difference respect to age, sex and BMI.

3.4. Effect on Mood Symptoms

Using both Zung SDS (depression) and Zung SAS (anxiety) scales, at the end of the study (T3, 3 months after the admission) we observed a statistically significant improvement of mood disorders (P < 0.01) (

Table 8).

3.5. Safety

No ADRs were documented during the study, and all enrolled patients reported high adherence to the treatment. As of August 2025, approximately three months after the final follow-up, no ADRs or drug interactions have been recorded in the study participants.

4. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the safety and efficacy of a fixed nutraceutical combination in patients with knee OA. OA is a common, chronic, degenerative joint disease for which pharmacological treatment primarily aims to reduce pain and improve quality of life. Conventional pharmacotherapy typically includes NSAIDs, analgesics (such as acetaminophen or opioids), and symptomatic slow-acting drugs for osteoarthritis (SYSADOAs) [

13,

23,

24,

25].

Wilson et al. [

26], previously reported that glucosamine and chondroitin are safe therapeutic options for patients with OA; however, it remains essential to thoroughly evaluate both their efficacy and the overall effectiveness of symptomatic SYSADOAs. Many naturally derived substances are readily available and are often taken without medical supervision, sometimes leading to uncertain benefits or even adverse effects and drug interactions. In our study, a three-month treatment with a fixed combination of several nutrients, including chondroitin sulfate, resulted in significant improvement in clinical symptoms. This nutraceutical combination was selected based on the established analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties of its components, which are thought to act synergistically [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

Each compound included in the formulation has demonstrated activity relevant to OA management. For example, in an experimental mouse model of OA, Zhan et al. [

33], showed that daily intragastric administration of lycopene (5 mg/kg) for 8 weeks attenuated IL-1β-induced chondrocyte inflammation by inhibiting the Nuclear Factor-κB pathway. Additionally, Martinez-Garcia et al. [

34], in a recent literature review, highlighted that omega-3 fatty acid consumption is associated with decreased pain and improved joint function and quality of life in OA patients. The omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) exert beneficial effects by modulating inflammatory responses, enhancing cartilage repair, and regulating bone metabolism [

35].

Furthermore, we previously reported that escin exhibits glucocorticoid-like anti-inflammatory activity [

36] as well as antioxidant properties [

37], supporting its potential role in the management of OA. Astaxanthin, another component, has demonstrated both anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects; it has been shown to reduce the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-13) in chondrocytes [

38] suggesting a possible therapeutic benefit in OA. In addition, astaxanthin possesses hepatoprotective properties, which are particularly relevant in patients undergoing polypharmacy.

All patients in our study presented with comorbidities and were receiving multiple medications; nevertheless, no ADRs or drug interactions were observed. This favorable safety profile may be related to the dosages of the active compounds used in the fixed nutraceutical combination. The improvement in quality of life and mood observed among our patients was likely attributable to the significant reduction in pain. Our study has some limitations, including a small sample size, which is typical of a pilot study. Larger, randomized controlled trials are warranted to confirm these preliminary findings.

5. Conclusion

Treatment with this new fixed combination of nutraceuticals improved clinical outcomes and quality of life in patients with knee OA without the development of adverse drug reactions, suggesting its potential as a safe and effective add-on therapy in this population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, CV, CP, GDM and LG; Data curation, CV, VR, GM, D.M. and LM; Formal analysis, GM; Investigation, CV, VR, GM, and LM MA-G; Methodology, EC, MCC and LG; Software, GM; Supervision, LG, EC; Writing – original draft, CV, GM; Writing – review & editing, MCC, DM, EC and LG. All authors will be informed about each step of manuscript processing including submission, revision, revision reminder, etc. via emails from our system or assigned Assistant Editor.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the local Ethics Committee Calabria Centro, protocol number 120/2018.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author. Data is available if requested.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Roemer, F. W.; Guermazi, A.; Demehri, S.; Wirth, W.; Kijowski, R. Imaging in Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2022, 30, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramoff, B.; Caldera, F.E. Osteoarthritis: Pathology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options. Med Clin North Am 2020, 104, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L. Osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 2021, 384, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallelli, L.; Galasso, O.; Falcone, D.; Southworth, S.; Greco, M.; Ventura, V.; Romualdi, P.; Corigliano, A.; Terracciano, R.; Savino, R.; Gulletta, E.; Gasparini, G.; De Sarro, G. The Effects of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs on Clinical Outcomes, Synovial Fluid Cytokine Concentration and Signal Transduction Pathways in Knee Osteoarthritis. A Randomized Open Label Trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013, 21, 1400–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rania, V.; Vocca, C.; Marcianò, G.; Caroleo, M. C.; Muraca, L.; Toraldo, E.; Greco, F.; Palleria, C.; Emerenziani, G. Pietro; Gallelli, L. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Two Different Formulations of Linear Hyaluronic Acid in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rania, V.; Marcianò, G.; Vocca, C.; Palleria, C.; Bianco, L.; Caroleo, M. C.; Gallelli, L. Efficacy and Safety of Intra-Articular Therapy with Cross-Linked Hyaluronic Acid in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucharz, E. J.; Szántó, S.; Ivanova Goycheva, M.; Petronijević, M.; Šimnovec, K.; Domżalski, M.; Gallelli, L.; Kamenov, Z.; Konstantynowicz, J.; Radunović, G.; Šteňo, B.; Stoilov, R.; Stok, R.; Vrana, R.; Bruyère, O.; Cooper, C.; Reginster, J. Y. Endorsement by Central European Experts of the Revised ESCEO Algorithm for the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int 2019, 39, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vocca, C.; Siniscalchi, A.; Rania, V.; Galati, C.; Marcianò, G.; Palleria, C.; Catarisano, L.; Gareri, I.; Leuzzi, M.; Muraca, L.; Citraro, R.; Nanci, G.; Scuteri, A.; Bianco, R. C.; Fera, I.; Greco, A.; Leuzzi, G.; Sarro, G. De; Agostino, B. D.; Gallelli, L. The Risk of Drug Interactions in Older Primary Care Patients after Hospital Discharge : The Role of Drug Reconciliation. Geriatrics (Switzerland) 2023, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcianò, G.; Vocca, C.; Evangelista, M.; Palleria, C.; Muraca, L.; Galati, C.; Monea, F.; Sportiello, L.; De Sarro, G.; Capuano, A.; Gallelli, L. The Pharmacological Treatment of Chronic Pain: From Guidelines to Daily Clinical Practice. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (10) Oo, W. M.; Little, C.; Duong, V.; Hunter, D. J. The Development of Disease-Modifying Therapies for Osteoarthritis (DMOADs): The Evidence to Date. Drug design, development and therapy 2021, 15, 2921–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (11) Esposito, R.; Mirra, D.; Spaziano, G.; Panico, F.; Gallelli, L. , D’Agostino, B. The Role of MMPs in the Era of CFTR Modulators: An Additional Target for Cystic Fibrosis Patients? Biomolecules 2023, 13, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (12) Kim, E. H.; Jeon, S.; Park, J.; Ryu, J. H.; Mobasheri, A.; Matta, C.; Jin, E. J. Progressing future osteoarthritis treatment toward precision medicine: integrating regenerative medicine, gene therapy and circadian biology. Experimental & molecular medicine 2025, 57, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, R. H.; Fillingham, Y. A. AAOS Clinical Practice Guideline Summary: Management of Osteoarthritis of the Knee (Nonarthroplasty), Third Edition. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2022, 30, e721–e729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Eyles, J.; McLachlan, A. J.; Mobasheri, A. Which Supplements Can I Recommend to My Osteoarthritis Patients? Rheumatology 2018, 57 (suppl_4), iv75–iv87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Machado, G. C.; Eyles, J. P.; Ravi, V.; Hunter, D. J. Dietary Supplements for Treating Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br J Sports Med 2018, 52, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Berkay Yılmaz, Y.; Antika, G.; Boyunegmez Tumer, T.; Fawzi Mahomoodally, M.; Lobine, D.; Akram, M.; Riaz, M.; Capanoglu, E.; Sharopov, F.; Martins, N.; Cho, W. C.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Insights on the Use of α-Lipoic Acid for Therapeutic Purposes. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apolone, G.; Mosconi, P. The Italian SF-36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol 1998, 51, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laucis, N. C.; Hays, R. D.; Bhattacharyya, T. Scoring the SF-36 in Orthopaedics : A Brief Guide. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015, 97, 1628–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunstan, D. A.; Scott, N. Norms for Zung’s Self-Rating Anxiety Scale. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunstan, D. A.; Scott, N. Clarification of the Cut-off Score for Zung ’ s Self-Rating Depression Scale. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, B. P. S.; Jagannatha, A.; Liu, F.; Yu, H. Inferring ADR Causality by Predicting the Naranjo Score from Clinical Notes. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2020, 2020, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo, C. A.; Busto, U.; Sellers, E. M.; Sandor, P.; Ruiz, I.; Roberts, E. A.; Janecek, E.; Domecq, C.; Greenblatt, D. J. A Method for Estimating the Probability of Adverse Drug Reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981, 30, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannuru, R. R.; Osani, M. C.; Vaysbrot, E. E.; Arden, N. K.; Bennell, K.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S. M. A.; Kraus, V. B.; Lohmander, L. S.; Abbott, J. H.; Bhandari, M.; Blanco, F. J.; Espinosa, R.; Haugen, I. K.; Lin, J.; Mandl, L. A.; Moilanen, E.; Nakamura, N.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Trojian, T.; Underwood, M.; McAlindon, T. E. OARSI Guidelines for the Non-Surgical Management of Knee, Hip, and Polyarticular Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019, 27, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolasinski, S. L.; Neogi, T.; Hochberg, M. C.; Oatis, C.; Guyatt, G.; Block, J.; Callahan, L.; Copenhaver, C.; Dodge, C.; Felson, D.; Gellar, K.; Harvey, W. F.; Hawker, G.; Herzig, E.; Kwoh, C. K.; Nelson, A. E.; Samuels, J.; Scanzello, C.; White, D.; Wise, B.; Altman, R. D.; DiRenzo, D.; Fontanarosa, J.; Giradi, G.; Ishimori, M.; Misra, D.; Shah, A. A.; Shmagel, A. K.; Thoma, L. M.; Turgunbaev, M.; Turner, A. S.; Reston, J. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020, 72, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyère, O.; Honvo, G.; Veronese, N.; Arden, N. K.; Branco, J.; Curtis, E. M.; Al-Daghri, N. M.; Herrero-Beaumont, G.; Martel-Pelletier, J.; Pelletier, J.-P.; Rannou, F.; Rizzoli, R.; Roth, R.; Uebelhart, D.; Cooper, C.; Reginster, J.-Y. An Updated Algorithm Recommendation for the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum 2019, 49, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.; Sanchez-Riera, L.; Morros, R.; Diez-Perez, A.; Javaid, M. K.; Cooper, C.; Arden, N. K.; Prieto-Alhambra, D. Drug Utilization in Patients with OA: A Population-Based Study. Rheumatology 2015, 54, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, F.; Alterio, C. D.; Vocca, C.; Gallelli, L.; Palumbo, F.; Cai, T.; Palmieri, A. Effectiveness of Silymarin, Sulforaphane, Lycopene, Green Tea, Tryptophan, Glutathione, and Escin on Human Health : A Narrative Review. Uro 2023, 3, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S. H.; Park, M.; Suh, J. H.; Choi, H. S. Protective Effects of an Extract of Young Radish (Raphanus Sativus L) Cultivated with Sulfur (Sulfur-Radish Extract) and of Sulforaphane on Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Hepatotoxicity. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2008, 72, 1176–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Jia, Z.; Strobl, J. S.; Ehrich, M.; Misra, H. P.; Li, Y. Potent Induction of Total Cellular and Mitochondrial Antioxidants and Phase 2 Enzymes by Cruciferous Sulforaphane in Rat Aortic Smooth Muscle Cells: Cytoprotection against Oxidative and Electrophilic Stress. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2008, 8, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshal, M.; Hazem, S. H. Escin Suppresses Immune Cell Infiltration and Selectively Modulates Nrf2/HO-1, TNF-α/JNK, and IL-22/STAT3 Signaling Pathways in Concanavalin A-Induced Autoimmune Hepatitis in Mice. Inflammopharmacology 2022, 30, 2317–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Xin, W.; Wang, T.; Zhang, L.; Fan, H.; Du, Y.; Li, C.; Fu, F. Protective Effect of Aescin from the Seeds of Aesculus Hippocastanum on Liver Injury Induced by Endotoxin in Mice. Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 1276–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. C.; Hsiang, C. Y.; Wu, S. L.; Ho, T. Y. Identification of Novel Mechanisms of Silymarin on the Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Mice by Nuclear Factor-ΚB Bioluminescent Imaging-Guided Transcriptomic Analysis. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2012, 50, 1568–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Yan, Z.; Kong, X.; Liu, J.; Lin, Z.; Qi, W.; Wu, Y.; Lin, J.; Pan, X.; Xue, X. Lycopene Inhibits IL-1β-induced Inflammation in Mouse Chondrocytes and Mediates Murine Osteoarthritis. J Cell Mol Med 2021, 25, 3573–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-García, R. M.; Ruiz Martínez, P.; Jiménez-Ortega, A. I.; Lozano-Estevan, M. del C. Nutritional Guidelines for the Improvement of Patients with Osteoarthritis. Nutr Hosp 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Lu, G.; Zheng, L.; Zhuang, M.; Liang, L.; Zhou, S.; Li, J.; Sun, X.; Liu, Y.; Ma, M.; Hu, J.; Yu, J.; Zhu, L. The Research Progress and Potential Applications of Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Orthopedics: A Narrative Review. British Journal of Nutrition 2025, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallelli, L.; Cione, E.; Wang, T.; Zhang, L. Glucocorticoid-Like Activity of Escin : A New Mechanism for an Old Drug. Drug Des Devel Ther 2021, 15, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcianò, G.; Vocca, C.; Dıraçoglu, D.; Özda, R.; Gallelli, L. Escin’ s Action on Bradykinin Pathway : Advantageous Clinical Properties for an Unknown Mechanism ? Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-P.; Xiong, Y.; Shi, Y.-X.; Hu, P.-F.; Bao, J.-P.; Wu, L.-D. Astaxanthin Reduces Matrix Metalloproteinase Expression in Human Chondrocytes. Int Immunopharmacol 2014, 19, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).