Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

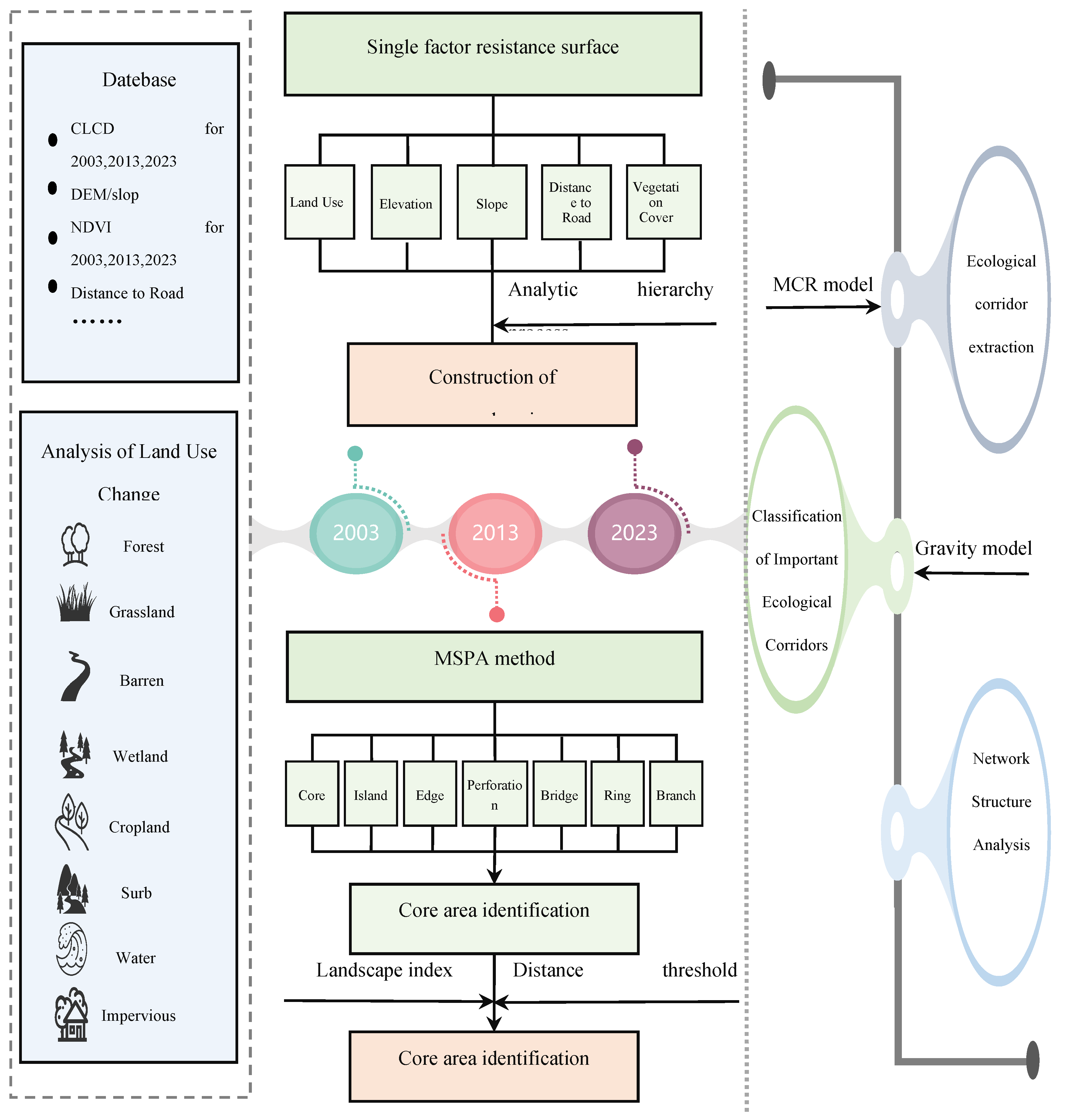

2. Materials and Methods

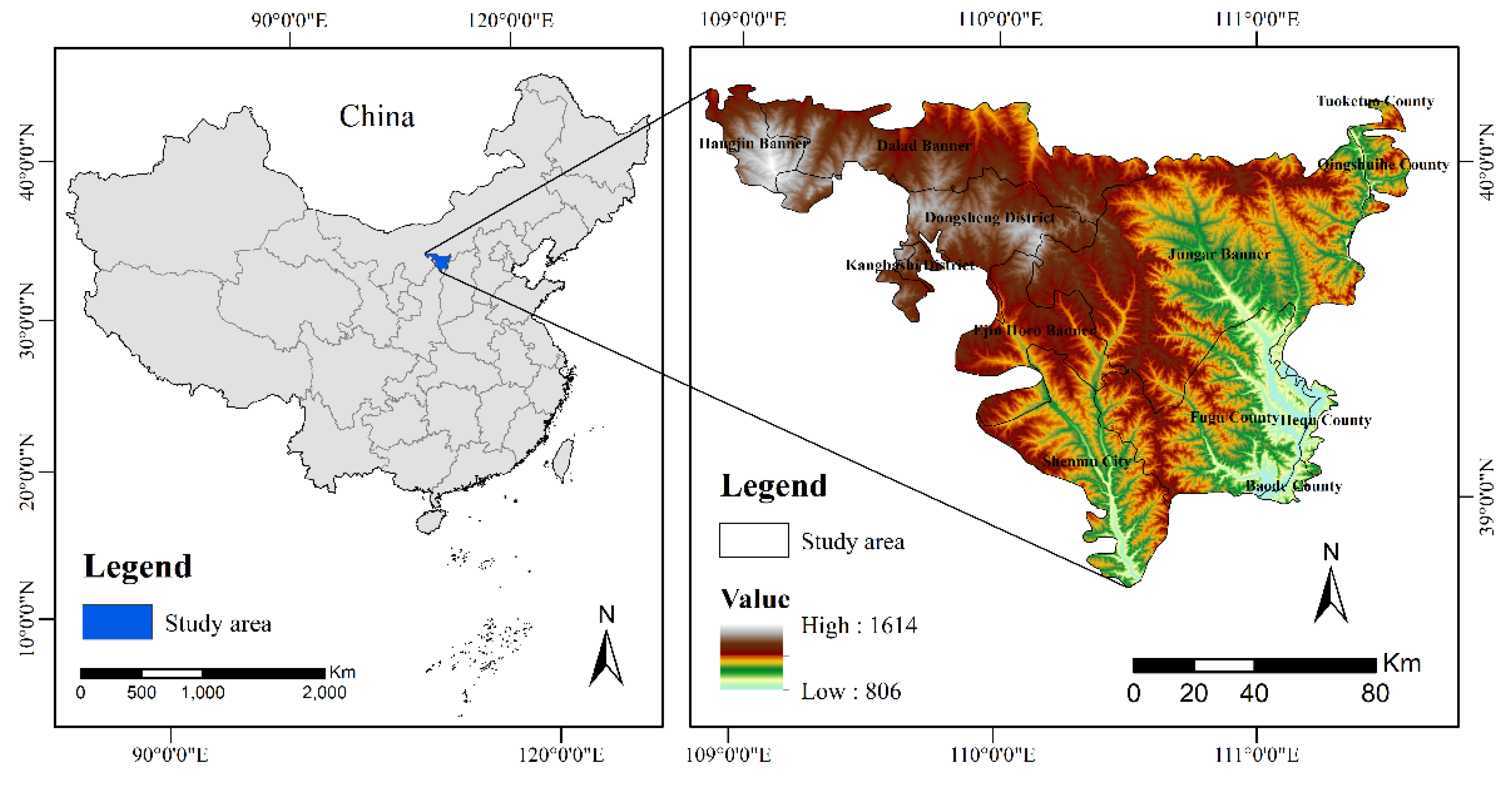

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Land Use Change Analysis Methods

2.3.2. Identification of Ecological Sources Based on MSPA

2.3.3. Spatiotemporal Analysis of GI Landscape Patterns Using Landscape Pattern Index Methods

2.3.4. Potential Corridor Simulation Based on the MCR Model

2.3.5. Identification and Evaluation of Key Corridors Based on Gravity Models

3. Results

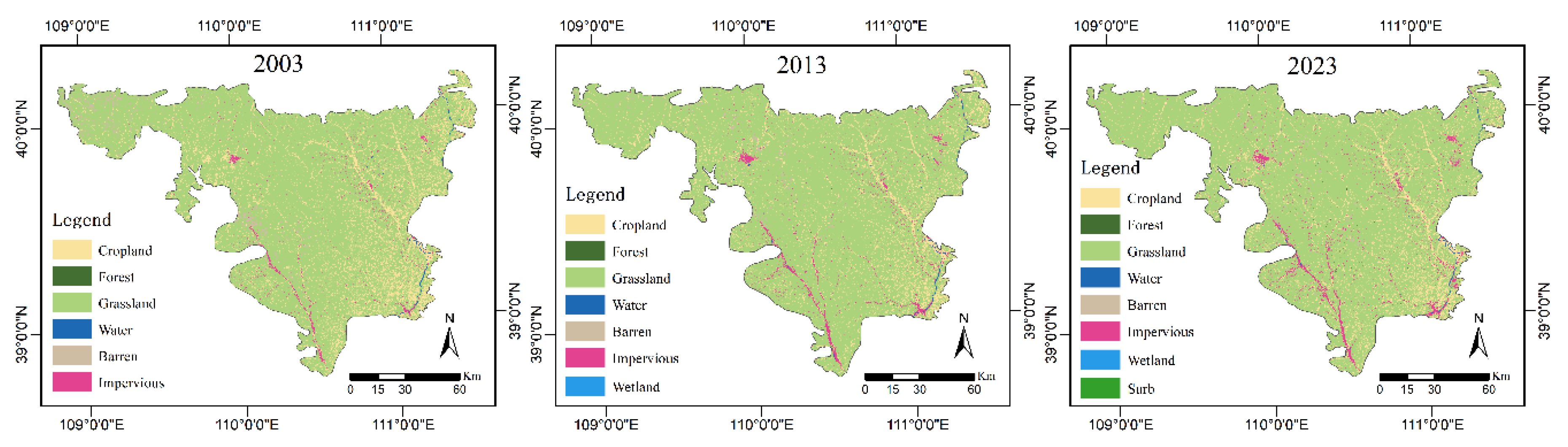

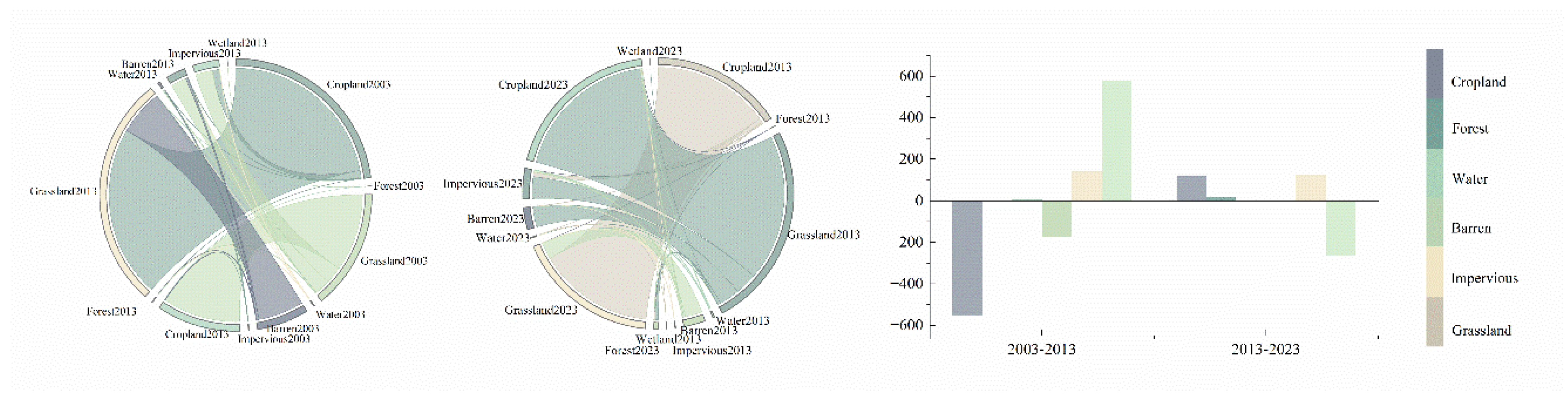

3.1. Analysis of Land Use Structure and Transfer Changes

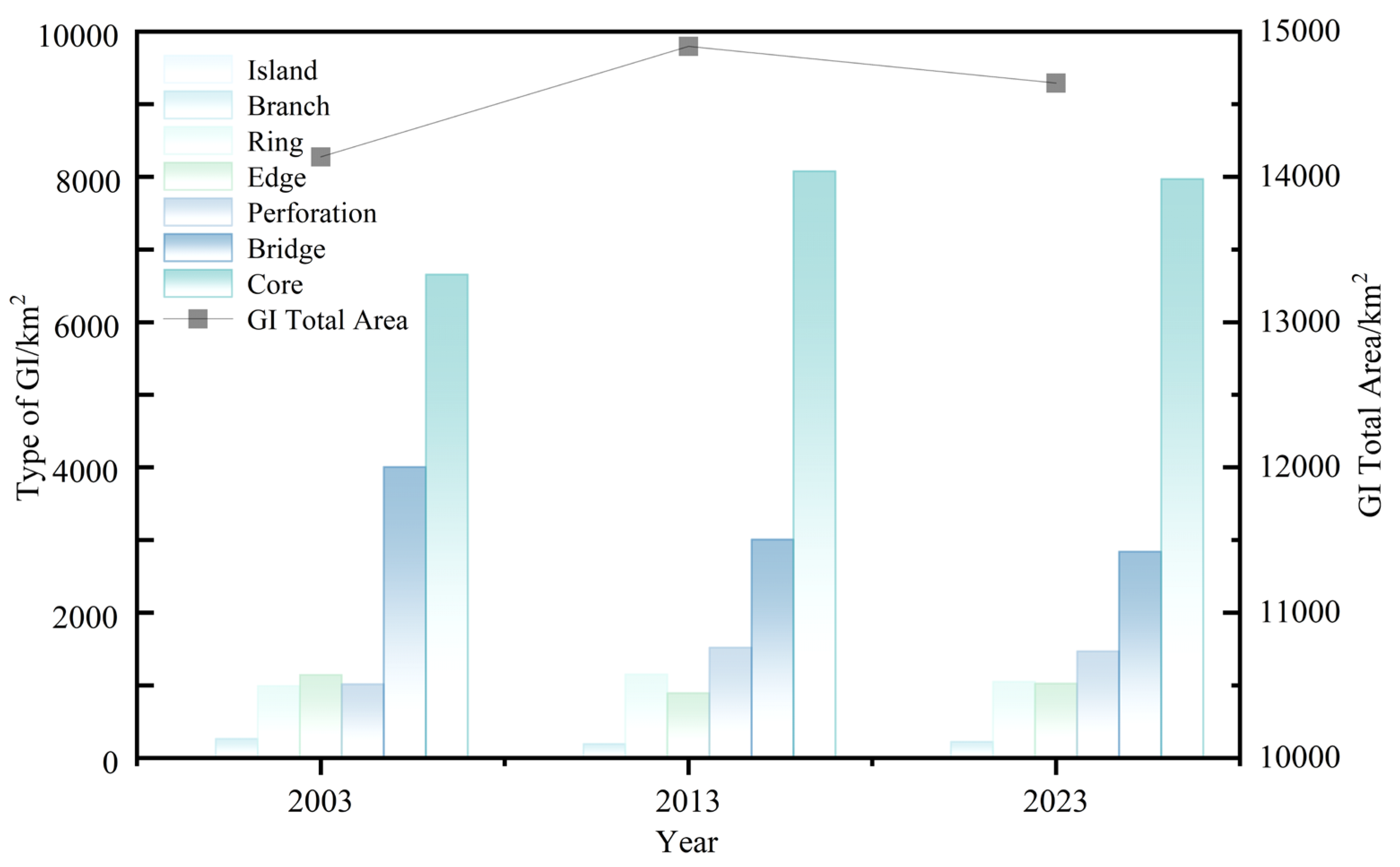

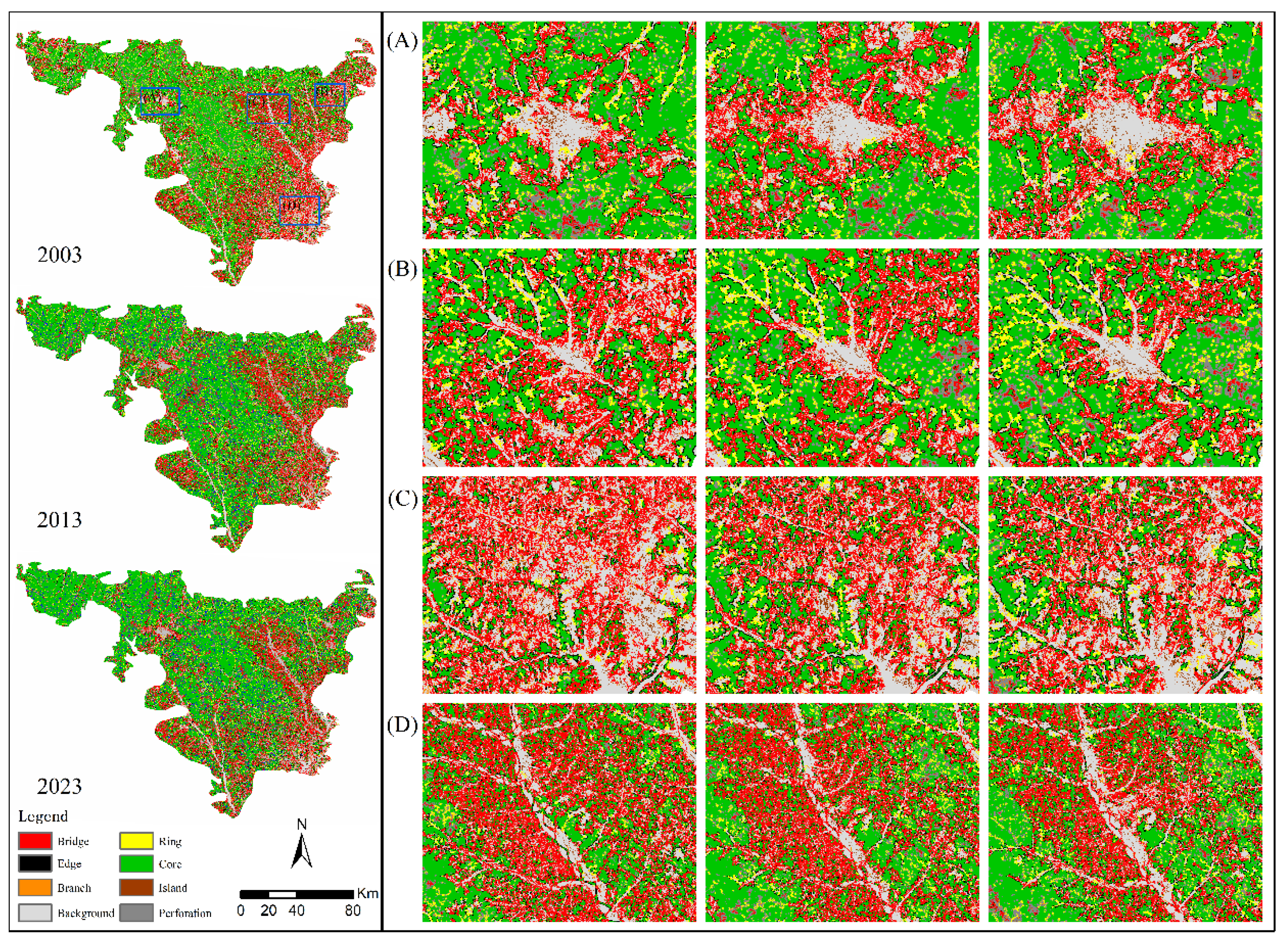

3.2. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of GI Based on MSPA

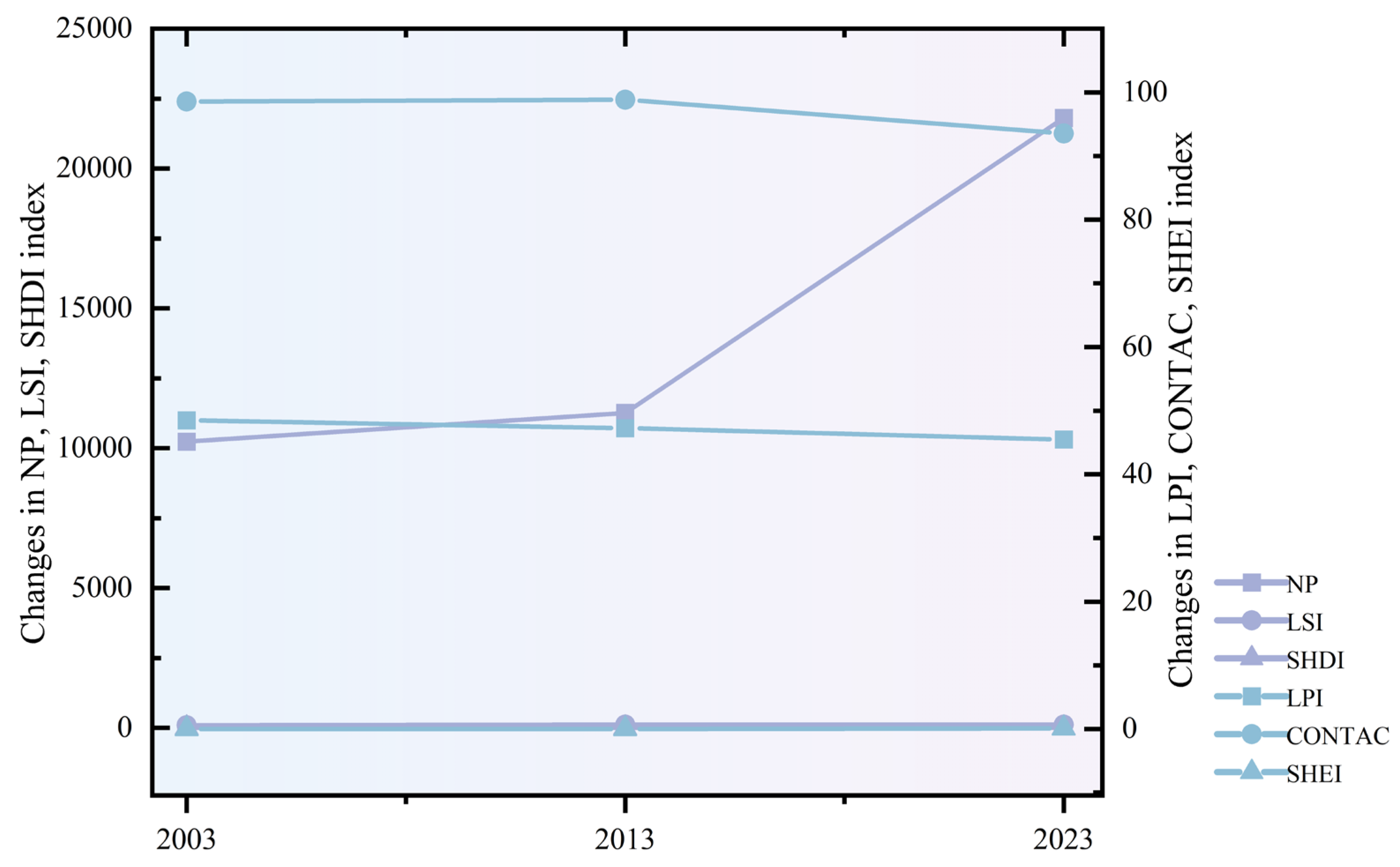

3.3. GI Landscape Pattern Analysis Based on Landscape Indices

3.4. GI Network Construction

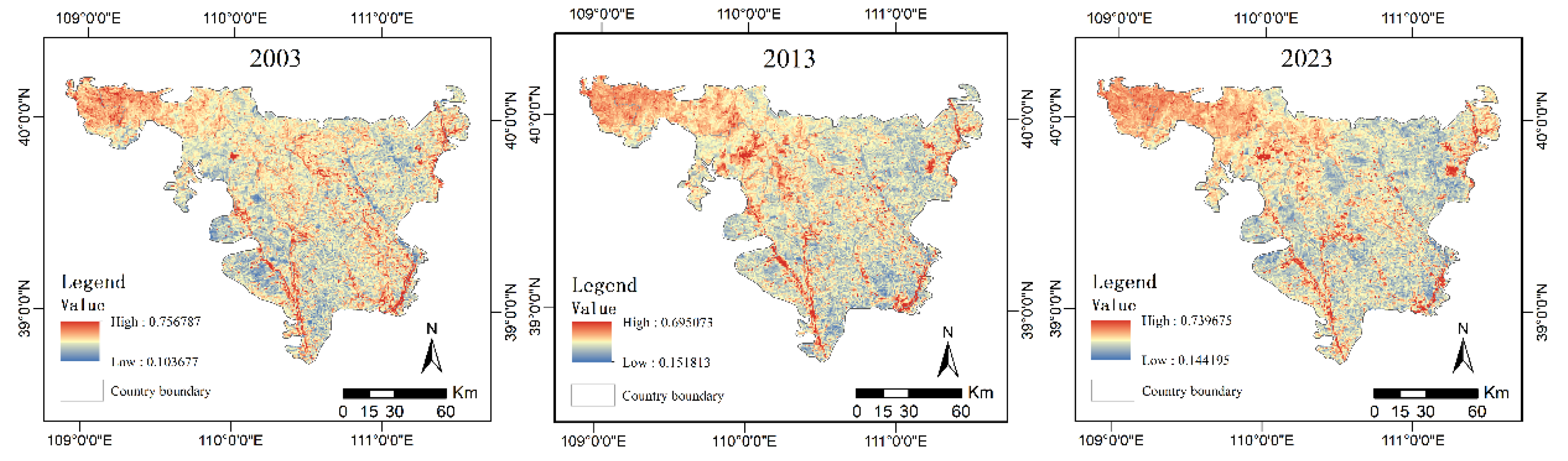

3.4.1. Ecological Resistance Surface Analysis

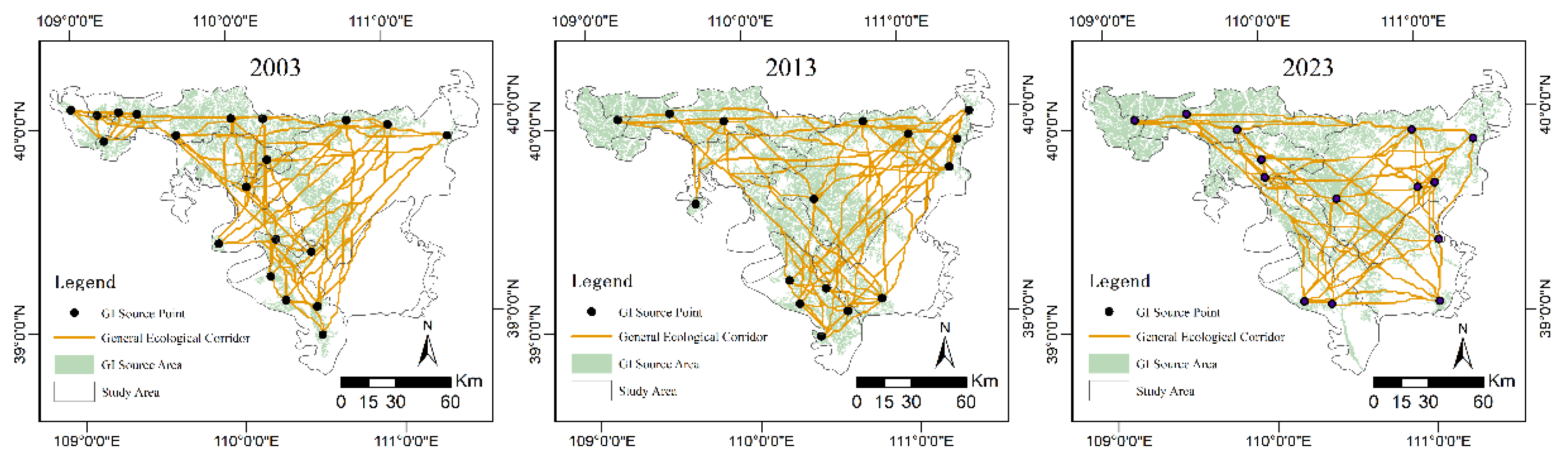

3.4.2. Simulation of Potential GI Corridors

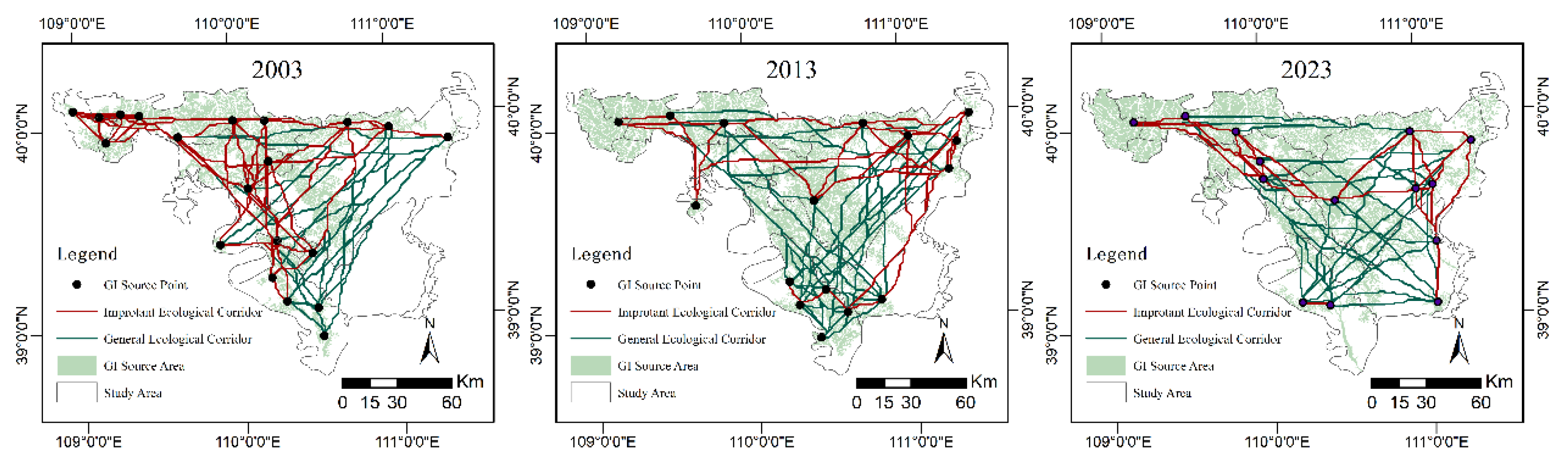

3.4.3. Construction of GI Networks Based on Gravity Model Analysis

3.4.4. Evaluation of GI Network Structure

4. Discussion

4.1. Necessity of GI Identification and Analysis in the Middle Reaches of the Yellow River

4.2. Driving Mechanism and Ecological Significance of GI Spatiotemporal Evolution in the Pisha Sandstone Area

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- From 2003 to 2023, grassland remained the dominant land use type in the study area, accounting for 82.70% to 84.57% of the total land area. Impervious surface increased by 270.48 km2, while farmland and bare land decreased by 433.35 km2 and 174.11 km2, respectively. Forest land and water bodies expanded by 22 km2 and 2.65 km2, respectively. Before 2013, farmland was the primary outflow land use type, with bare land decreasing and forest land, water bodies, impervious surface, and grassland increasing,driven by the “Grain for Green” policy. After 2013, grassland became the primary outflow land use type, with water bodies decreasing and farmland, forest land, impervious surface, and bare land increasing,characterized by significant impervious surface expansion influenced by urbanization and economic development.

- (2)

- From 2003 to 2023, the total area of GI in the study area showed a trend of initial increase followed by decrease, maintaining a proportion between 84.66% and 87.70%. Spatially, it exhibited a pattern of concentration in the northwest and sparseness in the southeast. As the primary component of GI, core areas showed an annual increase in area, accounting for 47.07% to 54.42% of the total GI area, with a spatial distribution concentrated in the northwest of the study area. Other GI types, such as bridges, edges, and loops, accounted for smaller proportions and were scattered between core areas. Despite certain achievements in ecological restoration, the GI landscape has become increasingly fragmented and heterogeneous due to inherent low erosion resistance, development activities, and energy extraction.

- (3)

- From 2003 to 2023, the study area exhibited a spatial distribution pattern of higher resistance values in the northwest and lower values in the southeast, with high-resistance areas continuously expanding. The number of ecological source sites decreased from 20 to 14, the number of general ecological corridors reduced from 152 to 75, and the number of important ecological corridors declined from 38 to 16. This reduction in the number of corridors is directly related to soil erosion fragmentation and source area fragmentation.

- (4)

- From 2003 to 2023, the network closure index (α index) decreased from 0.54 to 0.13, the line-point ratio (β index) dropped from 1.90 to 1.14, and the network connectivity index (γ index) fell from 0.70 to 0.44. This indicates that the overall spatial structure of the regional GI network is relatively underdeveloped, presenting a fragmented pattern characterized by local concentration and overall sparseness. Changes in the number and area of GI source areas are the primary drivers of network pattern evolution.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yi, W.; Hua, Y. Research and application of mechanical properties of red arsenic sandstone cement mixed soil. Building Science 2024, 40, 189.

- Zhao, J.; Yang, Z.; Guo, J.; Lü, Z.; Duan, P.; Zhou, X. Research Progress on Soil Erosion Patterns and the Applicability of Erosion Models in the Pisha Sandstone Area. Inner Mongolia Forestry Survey and Design 2025, 48, 92–97.

- Sheng, Y.; Qin, F.; Liu, L.; An, L.; Li, J. Evolution and Driving Mechanisms of Soil Conservation Function in Pisha Sandstone Area of the Yellow River Basin Based on the InVEST Mode. Journal of Northwest Forestry University 2024, 39, 144–152.

- Liang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Yao, W.; Noori, M.; Yang, C.; Xiao, P.; Leng, Y.; Deng, L. Pisha sandstone: Causes, processes and erosion options for its control and Prospects. International Soil and Water Conservation Research 2019, 7, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, G.; Yan, X. Influence of bedding structure on shear characteristics of pisha sandstone. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2025, 40, 1–11.

- Fu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, P.; Yao, W. Research on the contribution of compound erosion dynamics of arsenic sandstone slope in different seasons. Transactions of the CSAE 2020, 36, 66–73.

- Luo, Q.; Yang, Z.; Lü, Z.; Duan, P.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Q. Research Progress on Spatial Distribution and Optimal Allocation of Forest-Grass Vegetation in Pisha Sandstone Areas. Inner Mongolia Forestry Investigation and Design 2025, 48, 87–91.

- Liu, H.; Shi, P.; Wang, Y. The impact of open-pit mining on soil erosion in the mining area of ordos plateau in China. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2025, 39.

- Li, H.; Zhang, M.; Feng, L.; Zheng, S.; Du, Z. Research Status and Prospect of Soil and Water Loss Mechanism and Prevention Measures in Pisha Sandstone Area. Northwest Geology 2023, 56, 109-120.

- Li, C.; Fu, Y.; Di, L.; Jin, Y.; Qu, F.; Jia, D.; Tian, X. Progress in the physicochemical properties and harness and utilization of Pisha sandstone in the middle reaches of the Yellow River. Journal of North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power (Natural Science Edition) 2023, 44, 41-50.

- Zhang, P.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, Z.; Song, X.; Wang, L. Effect of Vegetation Patch Pattern on Soil Erosion Intensity on Pisha Sandstone Slope. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2022, 36, 58-65.

- Gao, L.; Gao, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, B.; Feng, J.; Li, W.; Ren, H. Research on the construction of a natural ecological restoration system based on zoning erosion control in the Ten Tributaries. Journal of Basic Science and Engineering 2025, 1-15.

- Duan, J. Discussion on Vegetation Construction Model in Pisha Sandstone Area of Middle Yellow River. Heilongjiang Hydraulic Science and Technology 2025, 53, 43-45+57.

- Fan, D.; Yang, Z.; Qin, F.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. Influence of Afforestation Density on Plant Diversity and Soil Physicochemical Properties of Pinus tabulaeformis in Pisha Sandstone Area. Bulletin of Soil and Water Conservation 2024, 44, 68-76.

- Shi, X.; Qin, M. Research on the Optimization of Regional Green Infrastructure Network. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4649. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xu, H.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, W. Green Infrastructure Network Identification at a Regional Scale: The Case of Nanjing Metropolitan Area, China. Forests 2022, 13, 735. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Guo, J.; Qin, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Liu, X. Spatiotemporal Variability of Soil Erosion in the Pisha Sandstone Region: Influences of Precipitation and Vegetation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9313. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, P.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, Y. Dynamic simulation study of soil erosion intensity on slopes with different vegetation patterns in pisha sandstone area. Ecological Modelling 2024, 491, 110665. [CrossRef]

- Matsler, M.; Grabowski, Z.; Elder, A. The Multifaceted Geographies of Green Infrastructure Policy and Planning: Socio-Environmental Dreams, Nightmares, and Amnesia. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 2021, 23, 559–564. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zheng, M.; Zheng, X.; Guo, W.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Zhu, B. Prediction and Spatiotemporal Evolution Analysis of Green Infrastructure Based on CA-Markov and MSPA: A Case Study of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2023, 43, 6785–6797. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Towards Integrated and Symbiotic Green Infrastructure Development. Landscape Architecture Academic Journal 2025, 42, 2–3.

- Huang, Y.; Feng, P.; Ma, Z.; Xiao, L. The Rise, Development and Thinking of China’s Green Infrastructure System Construction. Chinese Garden 2023, 39, 40–46.

- Zhang, J. Study on Green Infrastructure Functional Assessment and Its Network Planning in Zhengzhou City. Henan University 2023.

- Yang, B. Research on the Bottleneck and Strategy of Building Regional Ecological Network System in the Yangtze River Delta Integrated Demonstration Area. In Proceedings of the 2019 Annual Meeting of the Chinese Society of Landscape Architecture (Volume I) Shanghai Academy of Landscape Architecture and Planning. 2019,775-780.

- Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wu, B. Spatial and Temporal Changes and Development Predictions of Urban Green Spaces in Jinan City, Shandong, China. Ecological Indicators 2023, 152, 110373. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Sho, K.; Zhao, H.; Song, Y.; Uchiyama, Y.; Kim, J.; Sakai, T. Construction, Assessment, and Protection of Green Infrastructure Networks from a Dynamic Perspective: A Case Study of Dalian City, Liaoning Province, China. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2024, 101, 128545. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhai, J. Development of a Cross-Scale Landscape Infrastructure Network Guided by the New Jiangnan Watertown Urbanism: A Case Study of the Ecological Green Integration Demonstration Zone in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Ecological Indicators 2022, 143, 109317. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, F.; Dong, Y.; Wu, G.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Tran, L.; Li, W. Multi-objective Ecological Restoration Priority in China: Cost-Benefit Optimization in Different Ecological Performance Regimes Based on Planetary Boundaries. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 356, 120701. [CrossRef]

- Jato-Espino, D.; Capra-Ribeiro, F.; Moscardó, V.; Bartolomé del Pino, L.; Mayor-Vitoria, F.; Gallardo, L.; Carracedo, P.; Dietrich, K. A Systematic Review on the Ecosystem Services Provided by Green Infrastructure. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2023, 86, 127998. [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Gao, Z.; Sun, B.; Li, Y. Identification of Key Areas of Ecological Protection and Restoration Based on the Pattern of Ecological Security: A Case of Songyuan City, Jilin Province. China Environmental Science 2022, 42, 2779–2787.

- Li, H.; Wu, M.; Li, H.; Zhan, F.; Liu, Z. Evolution Characteristics and Optimization of Urban Ecological Network in Chaoyang District, Beijing. Landscape Architecture 2023, 30, 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhu, C.; Fan, X.; Li, M.; Xu, N.; Yuan, Y.; Guan, Y.; Lyu, C.; Bai, Z. Analysis of Ecological Network Evolution in an Ecological Restoration Area with the MSPA-MCR Model: A Case Study from Ningwu County, China. Ecological Indicators 2025, 170, 113067. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; He, M.; Li, X. Research Progress on Ecological Network Construction Based on Source-Corridor Method. Chinese Urban For 2023, 21, 145–151.

- Wang, Y.; Liu, L. Telecoupling: Spatial Ecological Wisdom for Performance Evaluation of Green Infrastructure. Chinese Landscape Architecture 2023, 39, 51–55.

- Liu, S.; Wang, Q.; Miao, C.; Dong Y.; Sun, Y.; Yu, L. Ecological Security Patterns of Water Conservation in the Upper Reaches of the Yellow River Basin (Sichuan Section) with Ecological Network Approach. Journal of Beijing Normal University(Natural Science) 2024, 60, 418–426.

- Wang, K.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; Jia, M.; Wu, L. Built-up Land Expansion and Its Impacts on Optimizing Green Infrastructure Networks in a Resource-Dependent City. Sustainable Cities and Society 2020, 55, 102026. [CrossRef]

- Staccione, A.; Candiago, S.; Mysiak, J. Mapping a Green Infrastructure Network: A Framework for Spatial Connectivity Applied in Northern Italy. Environmental Science & Policy 2022, 131, 57–67. [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Zhong, C.; Cui, D.; Han, Q.; Tang, J.; Chen, Y. Constructing Ecological Security Patterns through Regional Cooperation in the Yellow River Basin. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2024, 44, 4624–4636.

- Fu, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Ma, J.; Ma, R.; Li, J. Construction of GI Network in Gulf Village Area Based on MSPA and Circuit Theory: A Case Study of the Xieqian Harbor Area in Xiangshan. Journal of Ningbo University (Natural Science & Engineering Edition) 2024, 1-9.

- Gu, K.; Cui, Y.; Zhao, X. Research on Ecological Network Construction and Optimization Based on Spatial Classification System: Taking Chaohu Basin as an Example. Journal of Shenyang Jianzhu University (Social Science) 2024, 26, 384-392.

- Ana, M.; Cláudia, F.; João, F.; Paulo, F. A diagnostic framework for assessing land-use change impacts on landscape pattern and character – A case-study from the Douro region, Portugal. Landscape and Urban Planning 2022, 228, 104580.

- Jiening, W.; Wenchao, W.; Shasha, Z.; Yuanyuan, W.; Zehong, S.; Binglu, W. Spatial and temporal changes and development predictions of urban green spaces in Jinan City, Shandong, China. Ecological Indicators 2023, 152, 110373. [CrossRef]

- Pengting, D.; Peng, D.; Ziyun, R. Spatio-temporal pattern evolution of green development efficiency in Northeastern China and its driving factors. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32119. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, B.; Chai, M.; Liu, H.; Feng, Y. Scale Effect of the Spatial Pattern and Connectivity Analysis for the Green Infrastructure in Duliujian River Basin. Research of Environmental Sciences 2019, 32, 1464–1474.

- Dewa, D.; Buchori, I.; Sejati, A.; Liu, Y. Integrating Google Earth Engine and regional ecological corridor modeling for remote sensing-based urban heat island mitigation in Java, Indonesia. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 2025, 38, 101573. [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Bai, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zou, J. Spatial identification and optimization of ecological network in desert-oasis area of Yellow River Basin, China. Ecological Indicators 2023, 147, 109999. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Song, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Gao, W. Ecological network construction and land degradation risk identification in the Yellow River source area. iScience 2025, 112775. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, M. Construction and evaluation of the Panjin wetland ecological network based on the minimum cumulative resistance model. Ecological Modelling 2025, 505, 111118. [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Pearson, D.; Palmer, A.; Lowry, J.; Gray, D.; Dominati, E. Quantifying spatial non-stationarity in the relationship between landscape structure and the provision of ecosystem services: An example in the New Zealand hill country. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 808, 152126. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.; Devisscher, T. Strong relationships between urbanization, landscape structure, and ecosystem service multifunctionality in urban forest fragments. Landscape and Urban Planning 2022, 228, 104548. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Fu, D.; Huang, H.; Jiang, J.; Liu, Q.;Zhu, L.;Ding, G. Spatio-Temporal evolution and scenario-based optimization of urban ecosystem services supply and Demand: A block-scale study in Xiamen, China. Ecological Indicators 2025, 172, 113289. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Gong, J.; Hu, C.; Lei, J. An integrated approach to assess spatial and temporal changes in the contribution of the ecosystem to sustainable development goals over 20 years in China. Science of the Total Environment.2023 ,903,166237. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Ji, G.; Wang, F.; Ji, X. Analysis of spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of ecological networks based on complex network–spatial syntax. Journal of Xinyang Normal University (Natural Science Edition) 2025, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Deng, X.; Qi, Y.; Wang, P. Construction of Ecological Security Pattern in Henan Province Based on MSPA, Circuit Theory, and Space Syntax. Environmental Science 2025, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yang, M.; Fang, K. The Construction of Ecological Corridors in Wuqing District Based on Ecosystem Service Value and Ecological Sensitivity. Urban Architecture 2025, 22, 111–114.

- Liao, Y.; Xu, W.; Lin, X.; Shao, R. Ecological security pattern construction of Fuzhou based on source-resistance-corridor. Natural Science of Hainan University 2025, 43, 342–354. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, G.; Xing, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, W.; Cao, J. Spatiotemporal evolution of the ecological security pattern in Longnan City based on the MSPA-InVEST model. Arid Zone Research 2025, 42, 1103–1113. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Sun, H.; Zhang, P. Research on the Ecologic Spatial Pattern and Eco-Network Planning of Xi’an Metropolitan Area. Landscape Architecture Academic Journal 2025, 42, 23–32.

- Xinlei, X.; Siyuan, W.; Wenzhuo, R. Construction of ecological network in Suzhou based on the PLUS and MSPA models. Ecological Indicators 2023, 154, 110740. [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Wu, J. Shaping the general resilience of Green Infrastructure through integrating structures, functions, and connections. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 369, 122294. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Li, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, F.; Huang, F.; Xu, S.; Xiao, S.; Wang, Q. Effects of urbanization intensity on forest vegetation characteristics and landscape pattern indices in Nanchang. Chinese Journal of Ecology 2024, 43, 2285–2294.

- Jin, Z.; Yu, X.; Li, Z.; Tan, L.; Li, J. Scientific Investigation on the Entire Yellow River Basin: Understanding and Reflections. China Water Resources 2024, (23), 7-11+6.

- Wu, H.; Wei, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, S.; Di, W. Identification and Strategy of Key Areas of Land and Space Ecological Restoration Based on the Ecological Safety Pattern: Take Henan Province as an Example. Environmental Science 2024, 1-17.

- Wu, W.; Li, X.; Yang, P.; Xue, J.; Dou, X.; Xu, J.; Wu, G. Spatio-temporal Changes and Driving Forces of Land Use in Jinghe River Basin from 1992 to 2022. Journal of University of Jinan(Science and Technology) 2025, 1-10.

- Zou, C.; Li, W.; Li, B.; Chen, J. Construction and Optimization of Ecological Security Patterns in the Nyang River Basin based on Source-Corridor-Pinch Point . Science of Soil and Water Conservation. 2025,1-12.

- Huo, H.; Hou, Z.; Peng, K.; Wang, Q. Evaluation and optimization of ecological resilience of resource-based cities under the perspective of landscape pattern. Coal Engineering 2025, 57, 203–211.

- Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z. Identification, construction and optimization of Ma’anshan city urban green space ecological network. Journal of Anhui Agricultural University 2025,1-12.

- Guo, J.; Li, C.; Zhao, J.; Luo, C.; Mei, Z. Identification of Key Areas for Territorial Ecological Restoration Based on Ecological Security Patterns: A Case Study of the Huaihe River Basin. China Environmental Science, 2025,1-17.

- Chen, Y.; Chen, C.; Bi, Y. Research on Construction and Optimization of Green Infrastructure Network Based on MSPA: Taking the Central Urban Area of Lu’an City, Anhui Province as an Example. Landscape Architecture Academic Journal 2025, 42, 4–13+61.

- Gou, R.; Su, W. Construction of Ecological Security Pattern in Guizhou Province based on Multi Scenario Ecosystem Services Trade-offs. Environmental Science 2025, 1-19.

- Qi, C.; Yan, F.; Xi, L.; Cao, X.; Zou, J.; Feng, Y. A Study on the Potential for Vegetation Restoration in the Soft Rock Area of the Ordos Plateau. Arid Zone Research 2024, 41, 1583–1592. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Liu, L.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; An, L. Effects of Climate Change and Human Activities on Vegetation Coverage in Pisha Sandstone Area of Yellow River Basin. Bulletin of Soil and Water Conservation 2023, 43, 412–420. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhang, D.; Han, Y.; Fu, H.; Liu, Q. Analysis of Pisha Sandstone Erosion Characteristics in the Fragile Geological Area of Ordos. China Soil and Water Conservation 2024, (10), 67-70.

- Da, L.; Yu, Q.; Cai, B. Concepts and Key Techniques for Construction of Ecological Corridors in Urban Area. Journal of Chinese Urban Forestry 2010, 8, 11–14.

- Han, M.; Zhang, S.; Xu, Q.; Dai, J.; Huang, G. Construction of Cross-basin Ecological Security Patterns Based on Carbon Sinks and Landscape Connectivity. Environmental Science 2024, 45, 5844–5852. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Feng, Z.; Lin, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Wu, K. Research progress on the width of ecological corridors in ecological security pattern. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology 2025, 36, 918–926. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y. Research on the construction of ecological security pattern in Xiaochang County. Central China Normal University. 2023.

- Meng, Q. Study on Urban Ecological Corridor Based on Biodiversity Conservation. Beijing Forestry University. 2016.

- Tang, J.; Wang, G.; Xu, S. Spatiotemporal Changes and Protection Countermeasures of the Ecological Corridor of the Tarim River. Water Conservancy Planning and Design 2020, (08), 49-53.

- Liu, Y.; He, Z.; Chen, J.; Xie, C.; Xie, T.; Mu, C. Ecological network construction method based on MSPA and MCR model: taking Nanchong as example. Southwest Agricultural Journal 2021, 34, 354–363.

- Yan, M.; Liu, M.; Yao, X.; Guo, L.; Tang, Y.;Tian, G. Landscape connectivity based on the forest birds daily activities range in Jinshui district of Zhengzhou. Journal of Southwest Forestry University (Natural Sciences) 2020, 40, 107–117.

- Chen, G.; Wu, M.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, X.; Xue, M.; Liu, L.; Tang, Y. Construction of Ecological Security Pattern Based on MSPA and Circuit Theory: A Case Study of Fushan District, Yantai City. Journal of Ludong University(Natural Science Edition) 2025, 41, 145–155.

- Han, S.; Mei, Y.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, K.; Yin, X. Construction of Ecological Security Pattern in Yanping District of Nanping City, Fujian Province Based on Minimum Cumulative Resistance Model. Bulletin of Soil and Water Conservation 2019, 39, 192–198+205.

- Wu, H.; Wei, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, S.; Di, W. Identification and Strategy of Key Areas of Land and Space Ecological Restoration Based on the Ecological Safety Pattern: Take Henan Province as an Example. Environmental Science 2024, 1-17.

- Fu, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Ma, J.; Ma, R.; Li, J. Construction of GI Network in Gulf Village Area Based on MSPA and Circuit Theory: A Case Study of the Xieqian Harbor Area in Xiangshan. Journal of Ningbo University (Natural Science & Engineering Edition) 2024, 1-9.

- Gu, K.; Cui, Y.; Zhao, X. Research on Ecological Network Construction and Optimization Based on Spatial Classification System: Taking Chaohu Basin as an Example. Journal of Shenyang Jianzhu University (Social Science) 2024, 26, 384–392.

- Ana, M.; Cláudia, F.; João, F.; Paulo, F. A diagnostic framework for assessing land-use change impacts on landscape pattern and character – A case-study from the Douro region, Portugal. Landscape and Urban Planning 2022, 228, 104580. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, Q.; Xu, C.; Lin, S.; Qiu, R.; Hu, X. Construction of ecological network in Fujian Province based on Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2023, 43, 603–614. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Mei, Y.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, K.; Yin, X. Construction of Ecological Security Pattern in Yanping District of Nanping City, Fujian Province Based on Minimum Cumulative Resistance Model. Bulletin of Soil and Water Conservation 2019, 39, 192–198+205.

- Zhu, J. Research on the Construction of Green Infrastructure Network in Xinning County Based on MSPA and InVEST Model. Master’s Thesis, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, China, 2024.

- Tian, Y. The Study on Green Infrastructure Network in Chongqing Central based on MSPA and MCR model. Master’s Thesis, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, 2022.

- Yao, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, J.; Jiang,D. Construction of ecological security pattern based on ‘Pressure-state-response model’ in Linquan county of Anhui Province. Journal of Anhui Agricultural University 2020, 47, 538–546.

- Liu, L.; Sheng, Y.; Qin, F.; Li, L.; Li, Y. Evolution of Ecological Environmental Quality in Feldspathic Sandstone Area Based on RSEI Model. Bulletin of Soil and Water Conservation 2022, 42, 233–239+334.

- Yao, J.; Qin, F. Comprehensive Assessment on Eco-environmental Quality of the Sandstone Area Based on RS and GIS. Research of Soil and Water Conservation 2014, 21, 193–197+345.

| MSPA Elements | Ecological Significance |

|---|---|

| Core | Large natural patches, wildlife habitats, and forest reserves that provide large habitats for species. |

| Island | fragmented small patches with low connectivity between patches and limited potential for internal material and energy exchange. |

| Edge | The transition zone between core areas and developed land, exhibiting edge effects. |

| Perforation | Non-ecological areas within core areas that typically lack ecological benefits. |

| Bridge | Corridors within ecological networks that facilitate species migration, energy flow, and network formation within a region. |

| Ring | Ecological corridors connecting the same core area, serving as shortcuts for species migration within the core area. Branches |

| Branch | Connecting core areas and surrounding landscapes, acting as channels for species dispersal and energy exchange between core area patches and their surrounding landscapes. |

| Resistance Factor | secondary category | resistance value | Standardization Direction | Standardized Data Range |

Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land Use | Forest Land | 1 | Positive Direction | [0,1] | 0.1960 |

| Farmland Grassland |

2 | ||||

| Unused Land | 3 | ||||

| Water Areas | 4 | ||||

| Impervious Surface | 5 | ||||

| Elevation | / | / | Positive Direction | [0,1] | 0.0770 |

| Slope | / | / | Positive Direction | [0-1] | 0.3877 |

| Distance to Road | / | / | Negative Direction | [0-1] | 0.0386 |

| Vegetation Cover | / | / | Negative Direction | [0-1] | 0.3008 |

| Land Use | 2003 | 2013 | 2023 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (km2) | Proportion (%) | Area (km2) | Proportion (%) | Area (km2) | Proportion (%) | |

| Farmland | 2315.2572 | 13.8030 | 1762.8786 | 10.5098 | 1881.9036 | 11.2194 |

| Forest | 0.3087 | 0.0018 | 3.7260 | 0.0222 | 22.3101 | 0.1330 |

| Wetland | 37.5228 | 0.2237 | 43.9092 | 0.2618 | 40.1760 | 0.2395 |

| Unused Land | 311.1633 | 1.8551 | 134.2710 | 0.8005 | 137.0574 | 0.8171 |

| Impervious Surface | 236.6325 | 1.4107 | 379.7271 | 2.2638 | 507.1122 | 3.0233 |

| Grassland | 13872.7341 | 82.7057 | 14449.1040 | 86.1418 | 14185.0584 | 84.5677 |

| Land Use | 2003-2013 | 2013-2023 | 2003-2023 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in Area (km2) | Annual Growth Rate (%) | Change in Area (km2) | Annual Growth Rate (%) | Change in Area (km2) | Annual Growth Rate (%) | |

| Farmland | -552.3786 | -0.0239 | 119.025 | 0.0068 | -433.3536 | -0.0094 |

| Forest | 3.4173 | 1.107 | 18.5841 | 0.4988 | 22.0014 | 3.5636 |

| Wetland | 6.3864 | 0.017 | -3.7332 | -0.0085 | 2.6532 | 0.0035 |

| Unused Land | -176.8923 | -0.0568 | 2.7864 | 0.0021 | -174.1059 | -0.028 |

| Impervious Surface | 143.0946 | 0.0605 | 127.3851 | 0.0335 | 270.4797 | 0.0572 |

| Grassland | 576.3699 | 0.0042 | -264.0456 | -0.0018 | 312.3243 | 0.0011 |

| Year | GI Corridor | GI Source Point | Corridor Intersection |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 190 | 20 | 334 |

| 2013 | 120 | 16 | 394 |

| 2023 | 91 | 14 | 263 |

| Year | Source Point | Number of Connections | α | β | γ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 20 | 73 | 0.54 | 1.90 | 0.70 |

| 2013 | 16 | 33 | 0.22 | 1.31 | 0.50 |

| 2023 | 14 | 29 | 0.13 | 1.14 | 0.44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).