Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

14 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

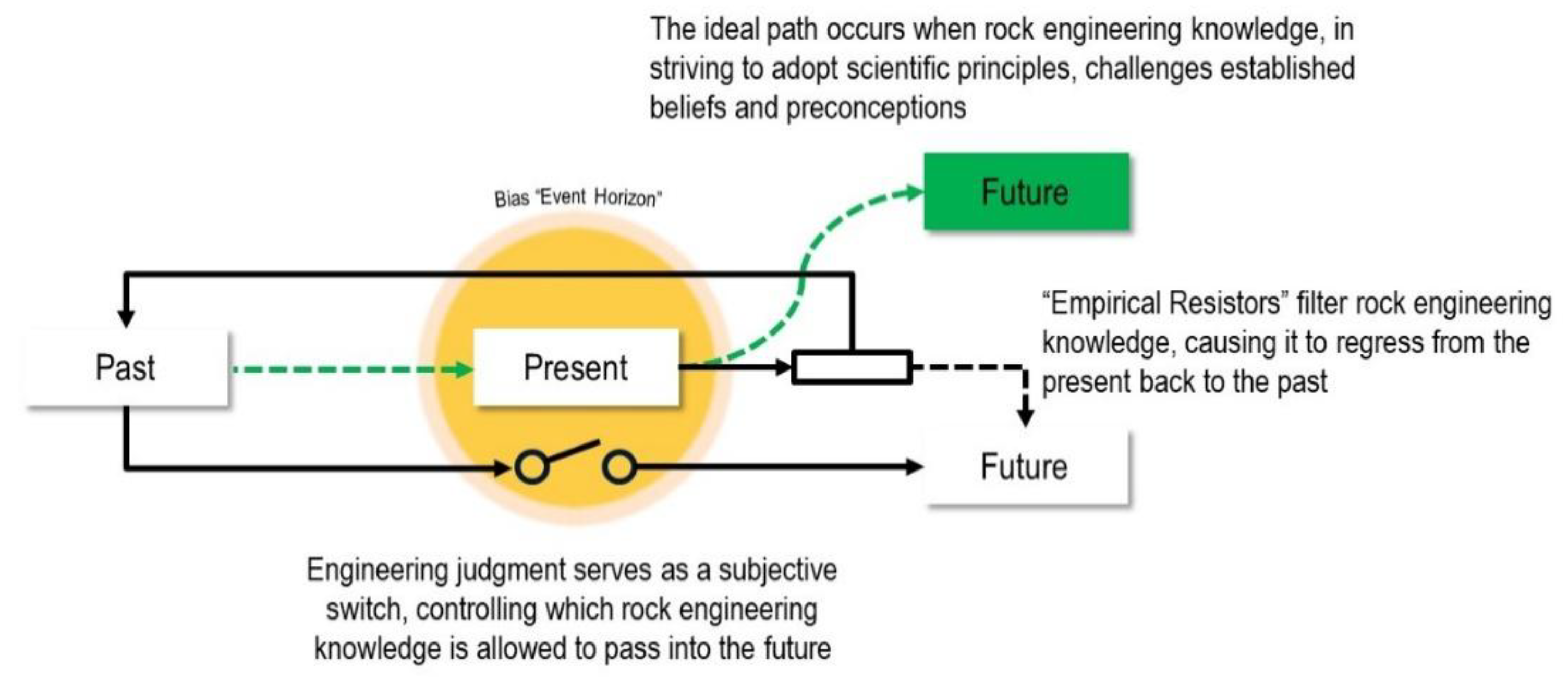

1. Introduction

- What constitutes appropriate validation for rock engineering theories and models when direct experimental verification is impossible?

- How can rock engineering practice develop frameworks for decision-making under radical uncertainty that preserve safety while acknowledging the inherent limitations of our predictive capabilities?

- How do the epistemological limitations of rock engineering knowledge affect the validity and reliability of design tools assisted by AI systems, and what safeguards are necessary to prevent the amplification of cognitive biases in automated decision-making?

2. The Empirical Structure of Rock Engineering Knowledge

3. Calibration and Validation Challenges in Rock Engineering Practice

3.1. Empirical Parameters and the Search for Universal Validation

1 is the maximum principal stress at failure

1 is the maximum principal stress at failure 3 is the minor principal stress applied to the specimen

3 is the minor principal stress applied to the specimen c is the uniaxial compressive strength of the intact rock material in the specimen.

c is the uniaxial compressive strength of the intact rock material in the specimen.3.2. From Limited Data to Established Practice

3.3. The Representative Elementary Volume: Conceptual Limitations and Validation Challenges

4. The Scientific Limitations of Empirical Methods

5. Rock Engineering and the Challenge of Operational Definitions

- Deliberately inducing failures in prototype slopes (ethically and practically unacceptable)

- Waiting for natural failures to occur (temporally impractical for design purposes)

- Relying on historical failures (which introduces temporal and contextual uncertainties)

5.1. Pragmatic Operationalism and Risk Assessment

- If they represent uncertainty (whether epistemic or aleatoric), this means that these conditions are unforeseen due to inadequate data collection and characterization. From a legal perspective, this amounts to admitting we failed to recognize that we did not collect sufficient information.

- If they represent radical uncertainty, this means no one could claim they would have acted differently, since the conditions would not have been known to them either.

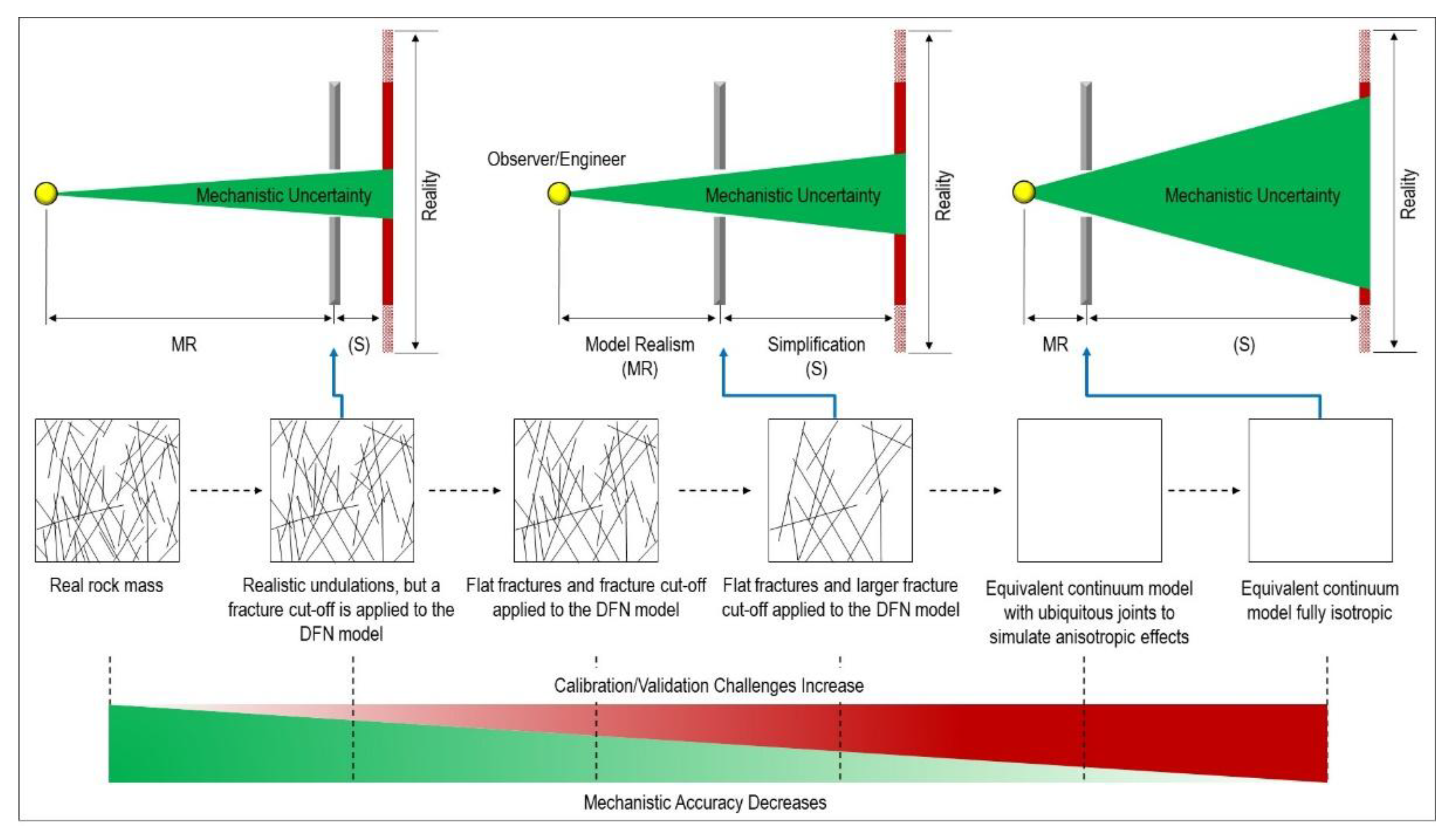

6. The Epistemological Limits of Modelling

6.1. The Mechanism Selection Paradox

- Scenario A: Modellers are asked to conduct stability analysis because the governing failure mechanism is unknown.

- Scenario B: Modellers are asked to conduct stability analysis to help identify the governing failure mechanism.

7. Uncertainty and Professional Responsibility in Rock Engineering Practice

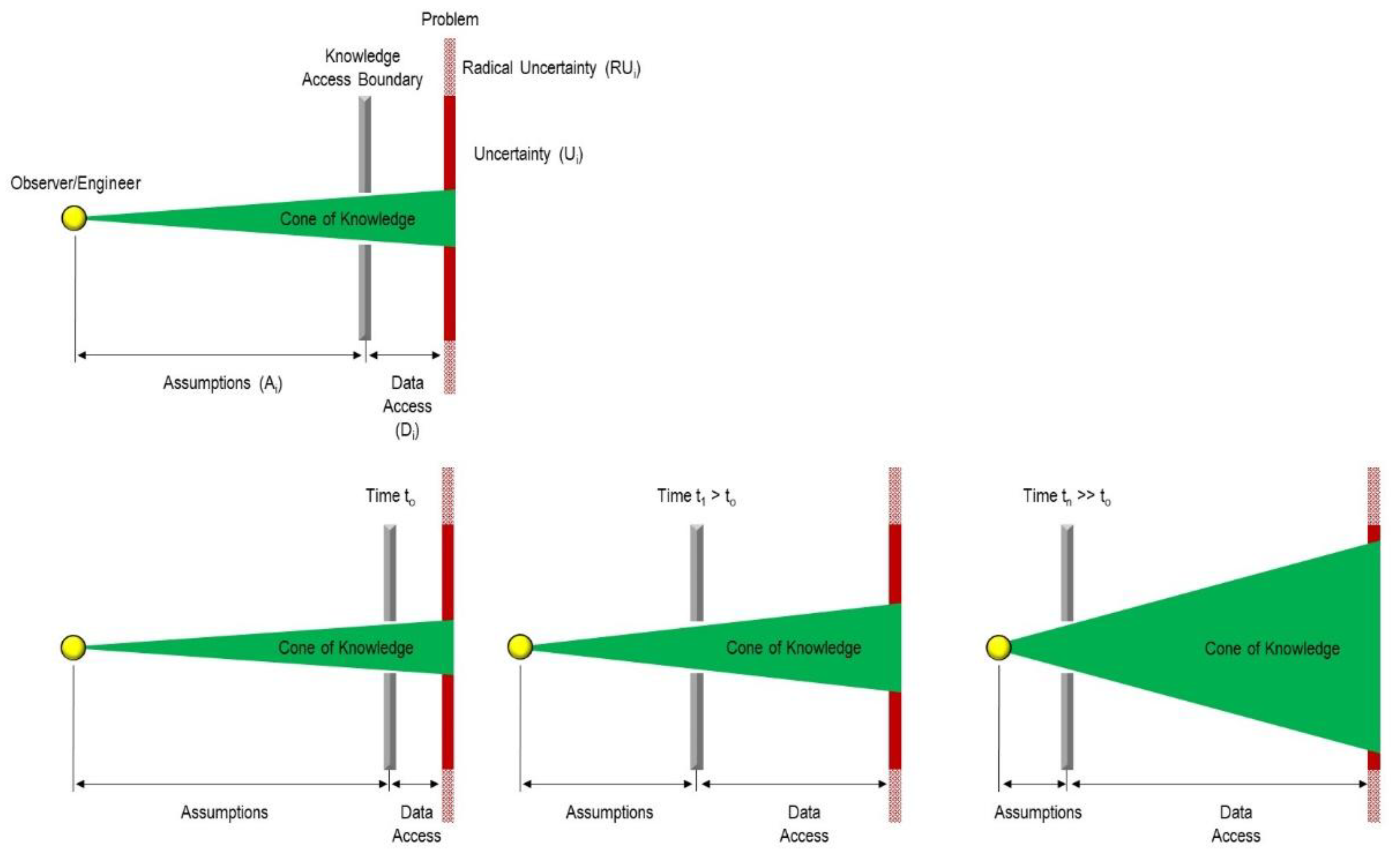

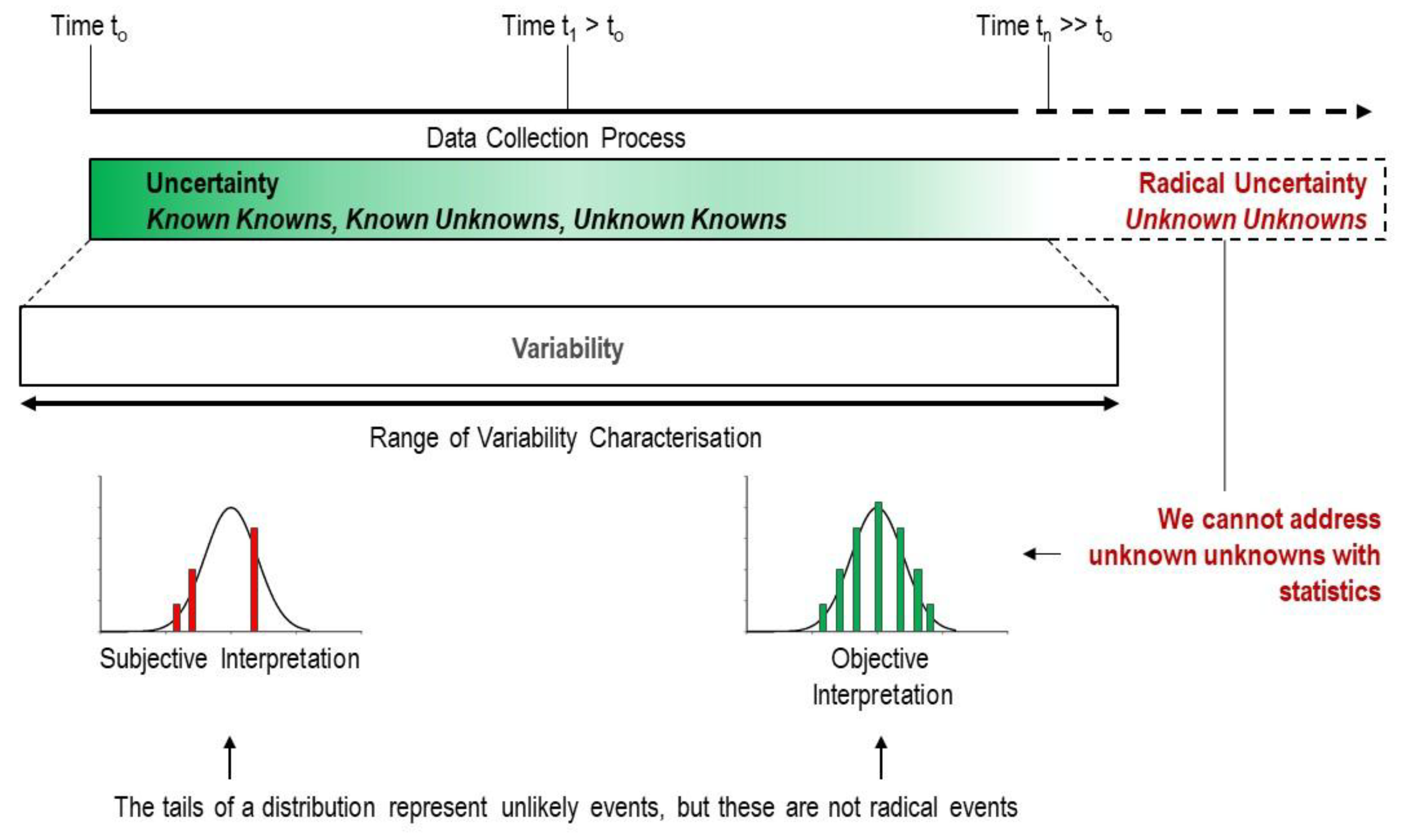

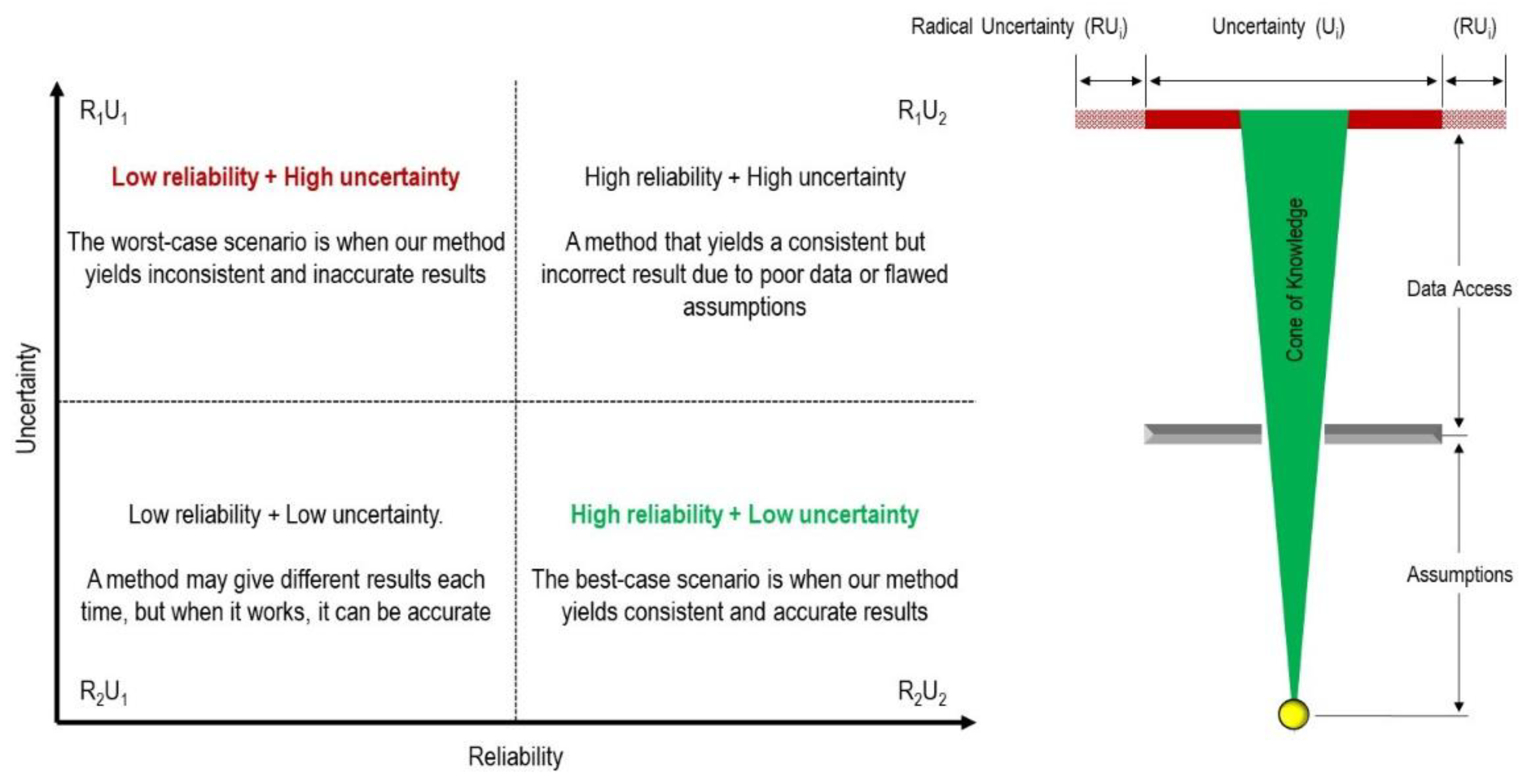

7.1. The Challenge of Dual Uncertainty

- First, we remain uncertain about our inputs. What are the actual rock mass properties at depth? How do joint properties vary spatially? What is the true in-situ stress state? These input uncertainties reflect not only measurement limitations but also fundamental constraints on observing three-dimensional geological structures through one-dimensional sampling.

- Second, even if we could magically eliminate all input uncertainty and know exact geological conditions, we would still face output uncertainty: What will actually happen when we excavate? Which failure mechanism will dominate? How will the rock mass respond to changing stress conditions over time? Will progressive failure occur, and if so, at what rate? This output uncertainty exists because geological systems exhibit emergent behaviour, scale-dependent mechanisms, and time-dependent processes that cannot be fully predicted even with perfect knowledge of the initial conditions.

7.2. Professional Practice vs. Uncertainty and Radical Uncertainty

7.3. Professional Practice vs. Linguistic

7.4. The Algorithmic Amplification of Uncertainty

8. Conclusions

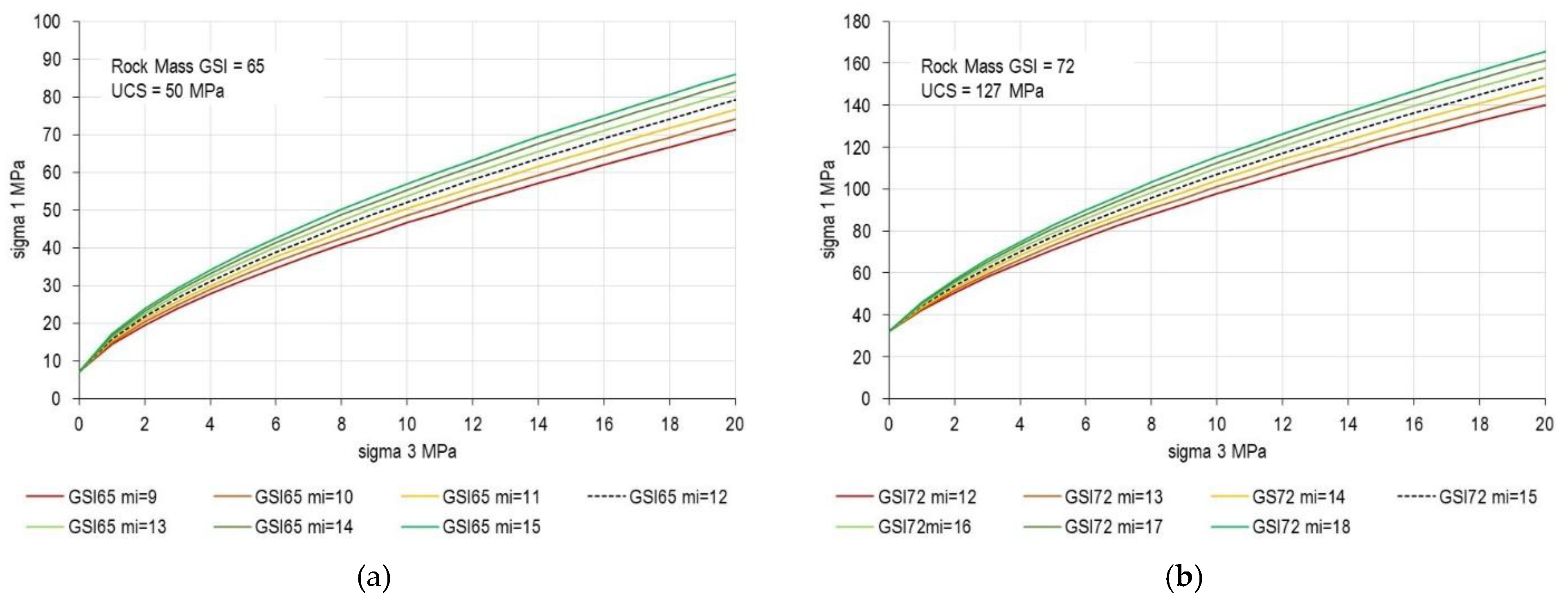

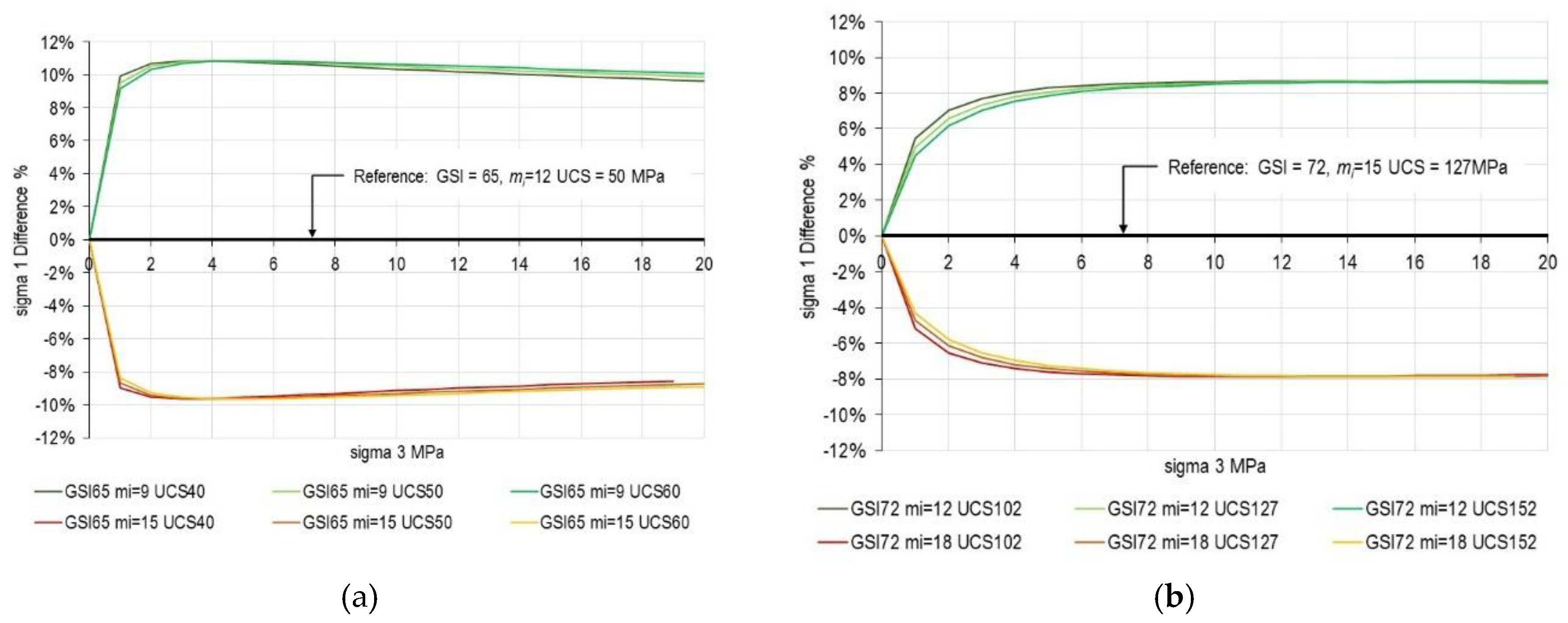

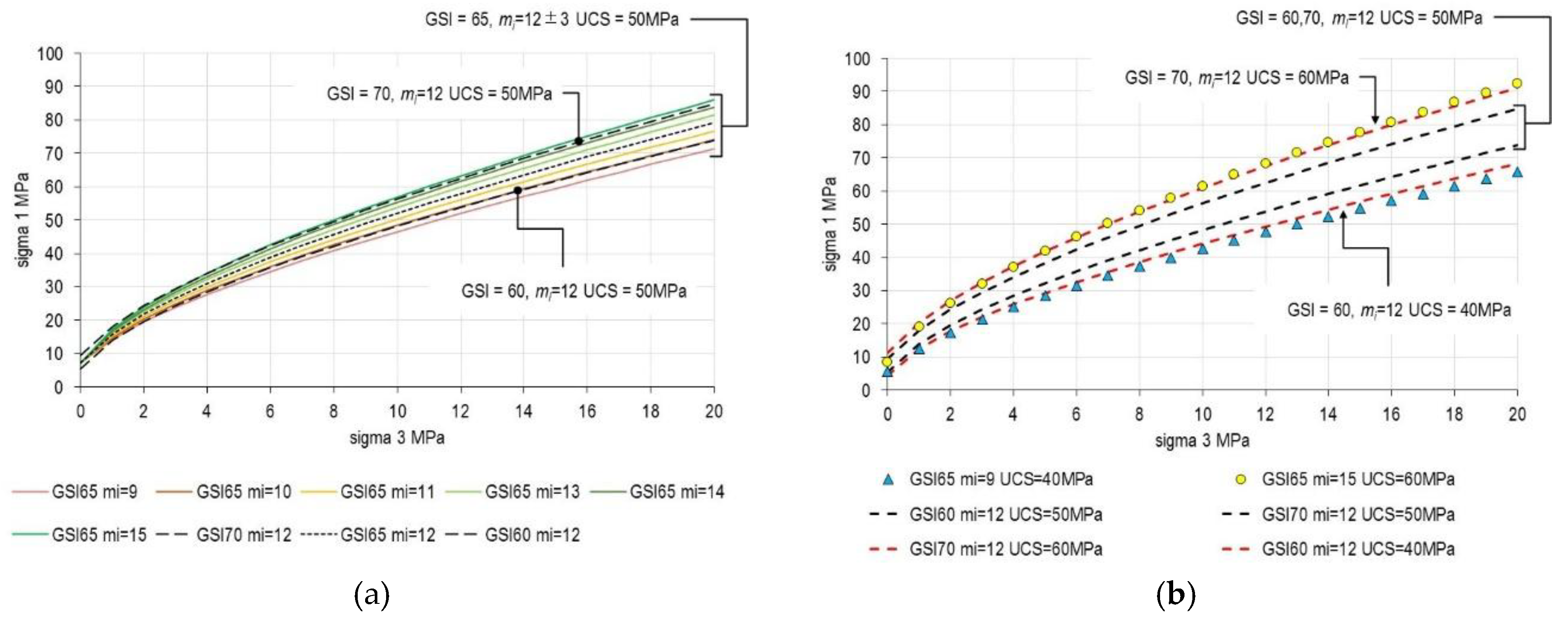

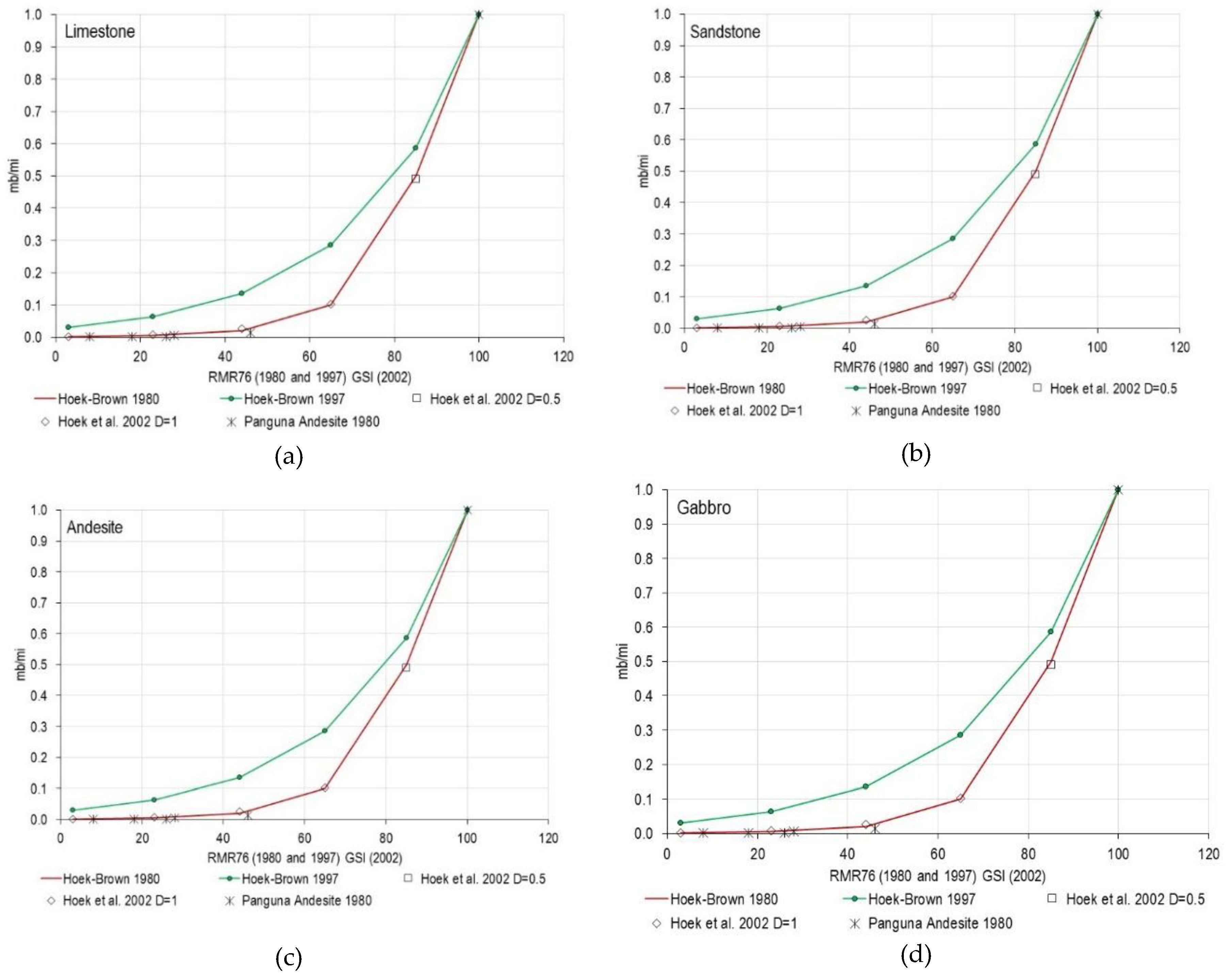

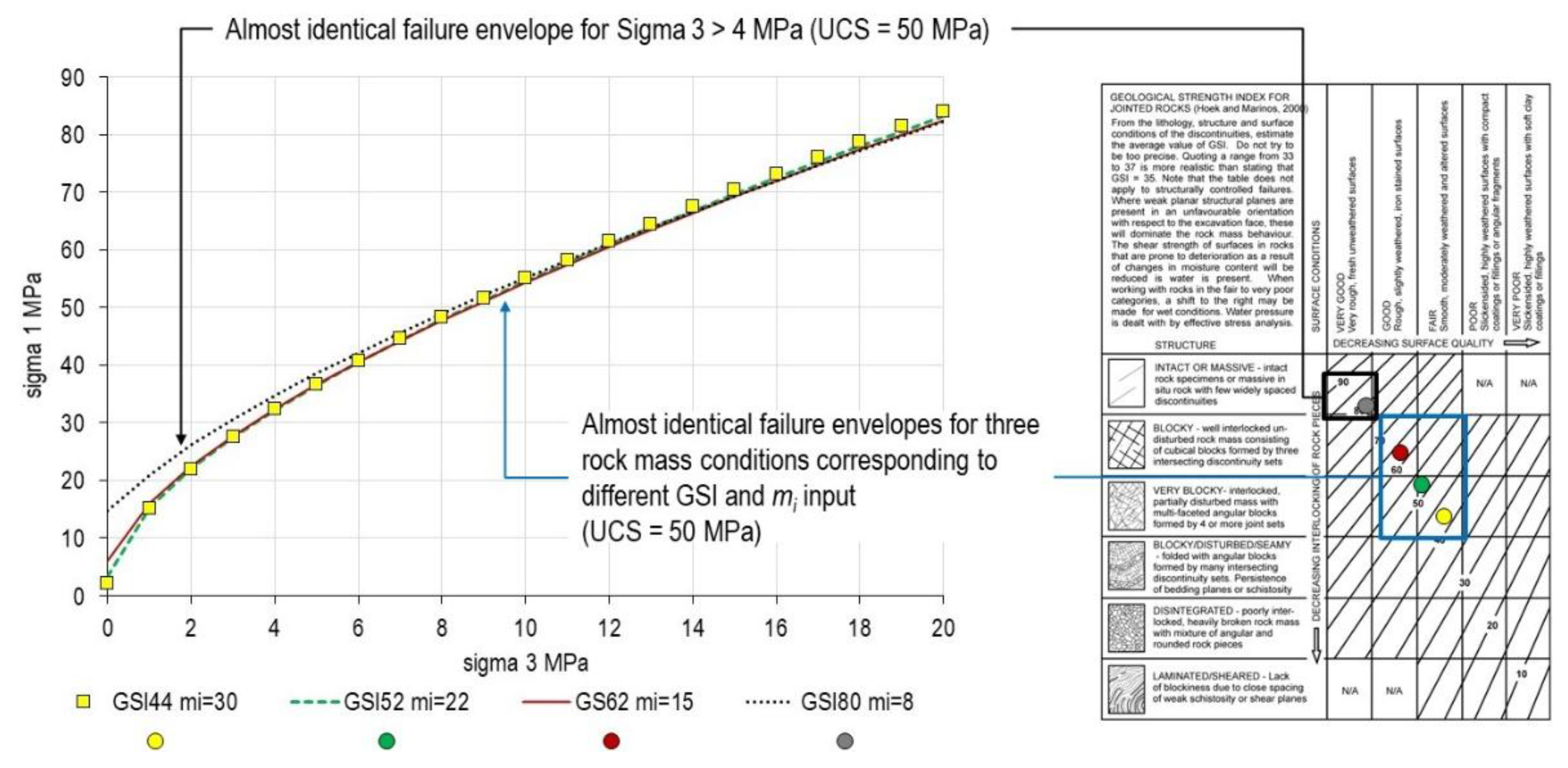

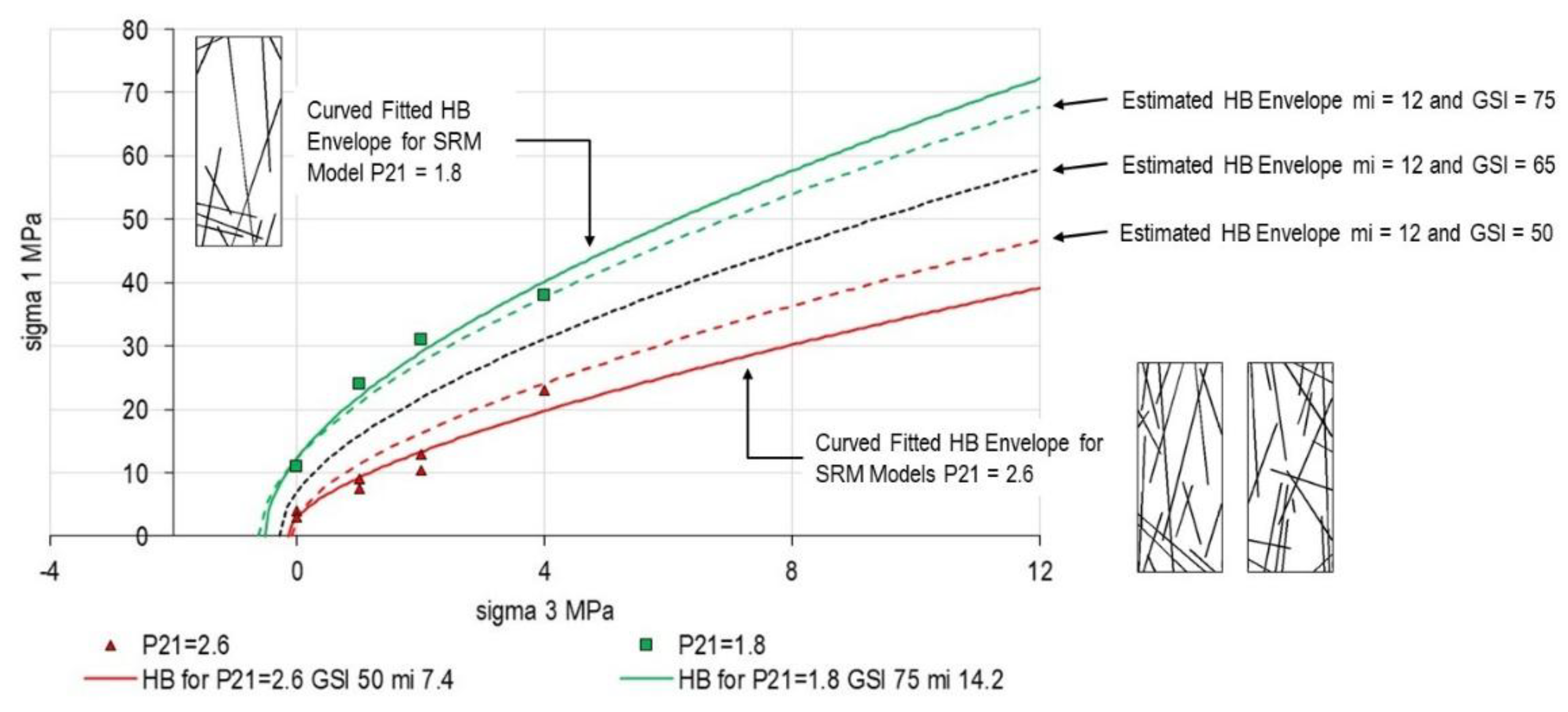

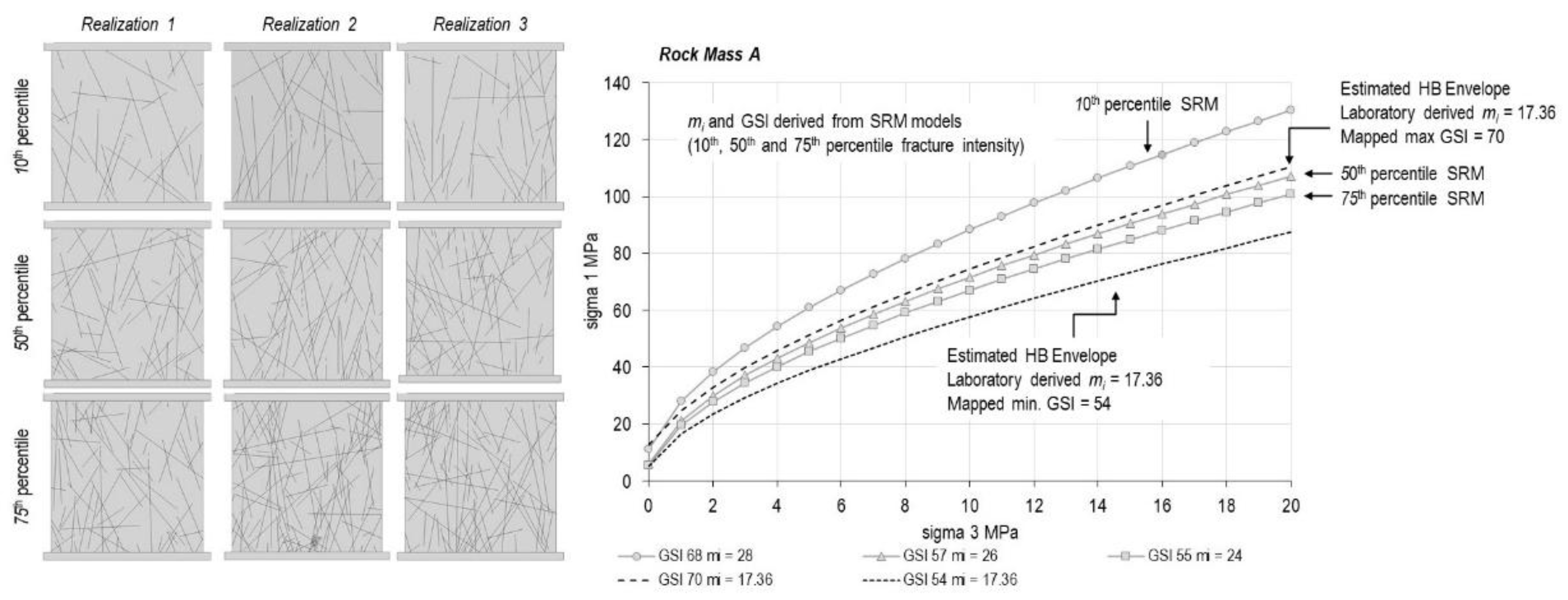

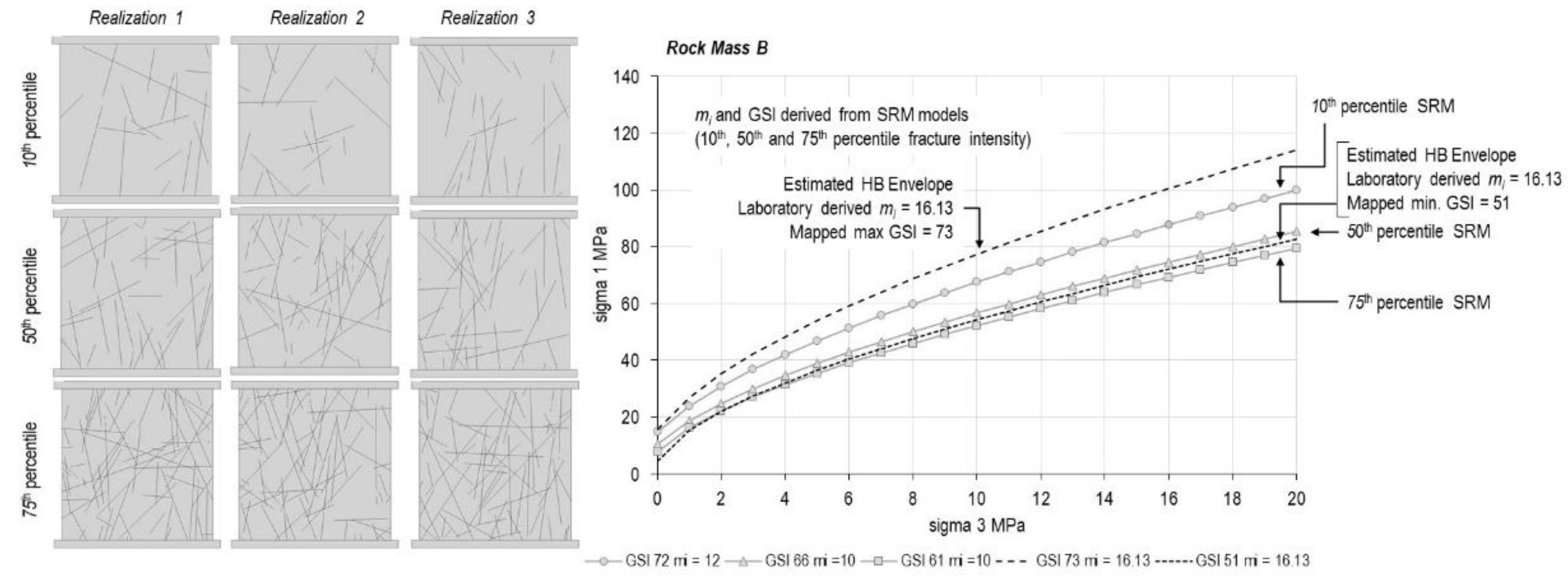

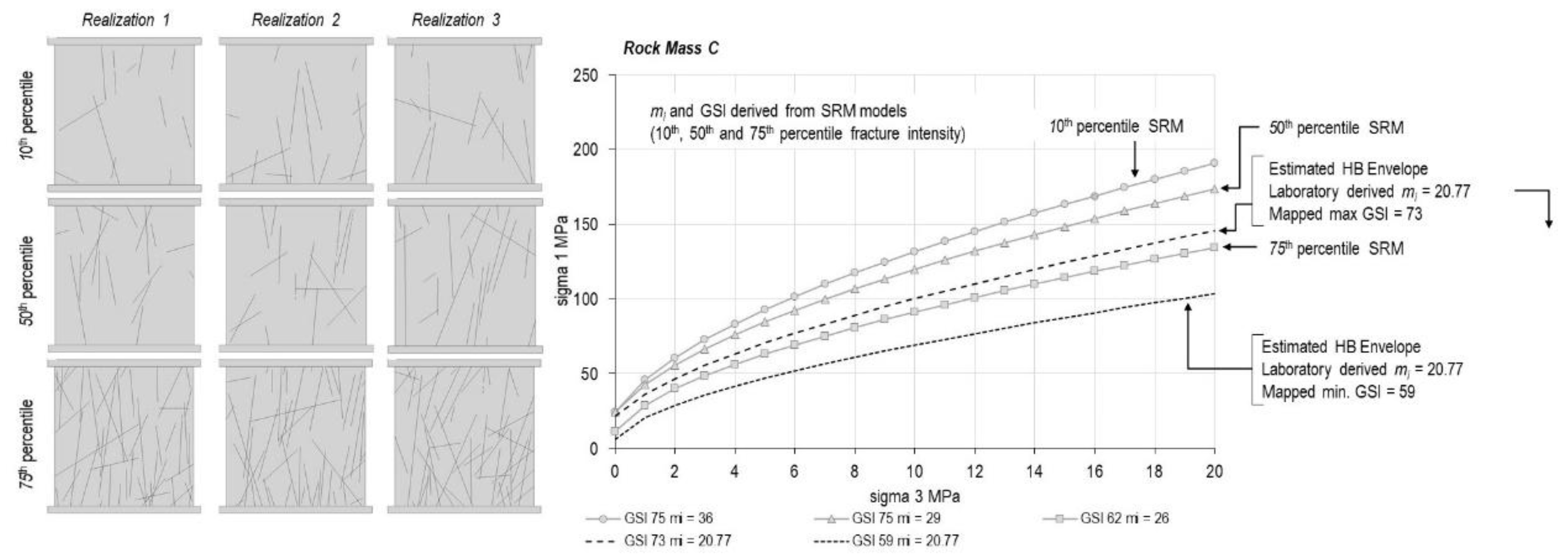

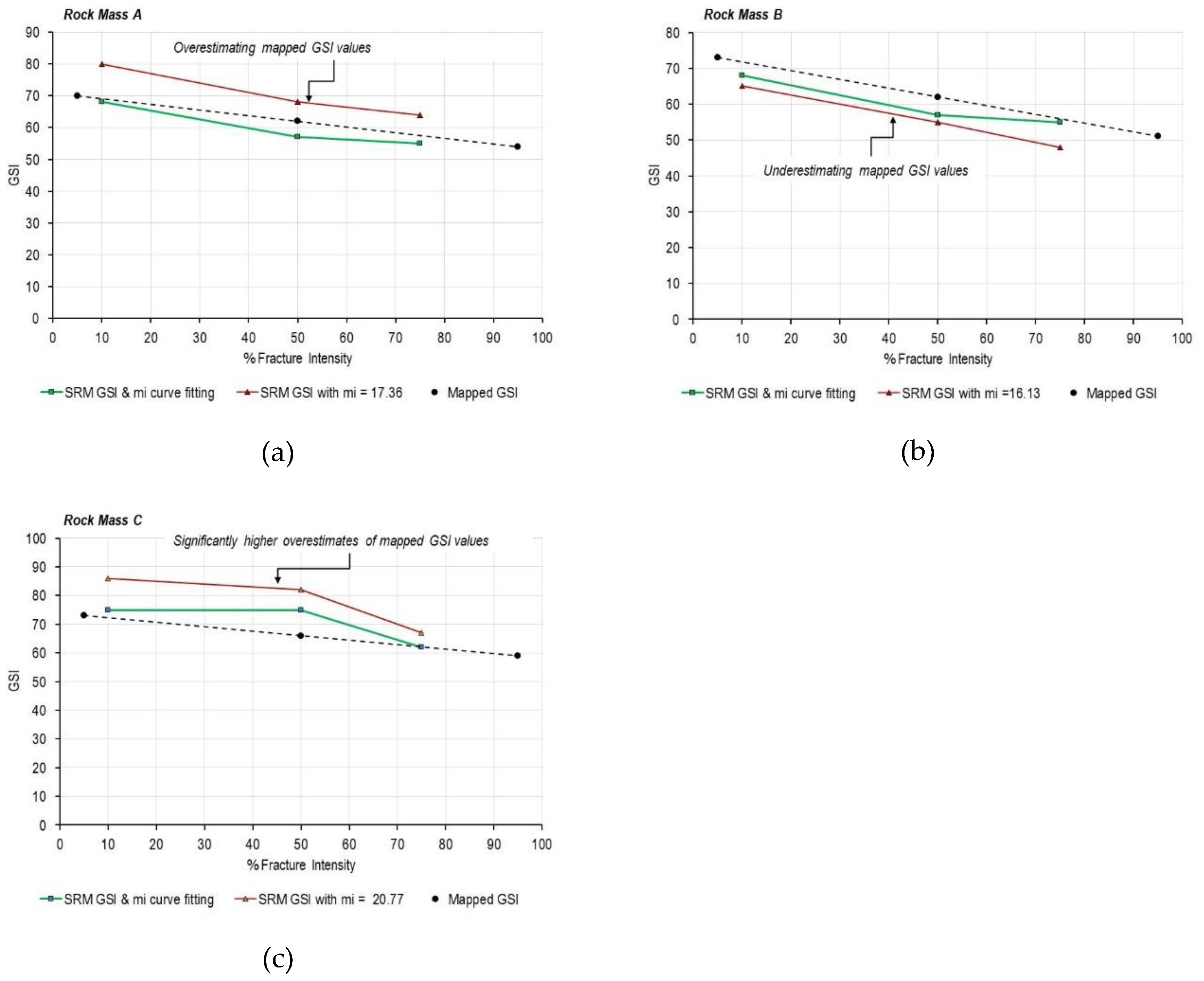

- Equation (1) does not require GSI, and the parameters m and s emerge from fitting the results of a series of triaxial tests (or biaxial SRM models, as in our paper).

- Equation (2) requires GSI, from which mb and s are calculated as functions of the assumed GSI value.

- The search for “accurate” and “precise” parameter determination (Section 2) proves misguided when different parameter combinations produce equivalent outcomes. For instance, the combined Hoek-Brown and GSI approach should be considered in the context of homogenizing and simplifying a jointed rock mass into an equivalent continuum medium.

- GSI quantification methods (Section 3) cannot resolve this ambiguity, as no quantification scheme can eliminate the non-uniqueness inherent in the GSI framework itself.

- Additional testing and characterization may reduce uncertainty about which parameterization to use, but cannot eliminate radical uncertainty.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| GSI | Geological Strength Index |

| RMR | Rock Mass Rating |

| DFN | Discrete Fracture Network |

| SRM | Synthetic Rock Mass |

| REV | Representative Elementary Volume |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

References

- Stevens, S.S. On the theory of scales of measurement. Science 1946, 103, 677–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgenroth, J.; Unterlaß, P.J.; Sapronova, A.; Khan, U.T.; Perras, M.A.; Erharter, G.H.; Marcher, T. Practical recommendations for machine learning in underground rock engineering—On algorithm development, data balancing, and input variable selection. Geomech. Tunn. 2022, 15, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Editorial on Papers Using Numerical Methods, Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 1619. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B. Examining the reliability of integrating machine learning with rock mass characterization and classification data, Doctoral thesis, 2024, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

- Elmo, D. The risk of confusing model calibration and model validation with model acceptance. in PM Dight (ed.), SSIM 2023: Third International Slope Stability in Mining Conference, Australian Centre for Geomechanics, Perth, pp. 333-342.

- Flexner, A. The usefulness of useless knowledge., Essay, Harpers, Issue 179, June/November 1939.

- Hoek, E.; Brown, E.T. Underground excavations in rock. London: Instn Min. Metall., 1980.

- Elmo, D.; Stead, D. The Role of Behavioural Factors and Cognitive Biases in Rock Engineering. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2021, 54, 2109–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, K. The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Routledge, 1959, pp. 545.

- Dougherty, E.R. The evolution of scientific knowledge: From certainty to uncertainty. Bellingham, Washington: SPIE Press, 2016.

- Yang, B.; Mitelman, A.; Elmo, D.; Stead, D. Why the future of rock mass classification systems requires revisiting its empirical past. Q. J. Rock Eng. Hydrogeol. 2021, 55, qjegh2021-039.

- Elmo, D; Zoorabadi, M. Examining the case for accuracy and precision when determining the Hoek-Brown parameters. Submitted to Rock Mech. Rock Eng, 2025. Under Review.

- Hoek, E.; Brown, E. Practical estimates of rock mass strength. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. 1997, 34, 1165–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, E. Strength of rock and rock masses. ISRM News J. 1994, 2, 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Marinos, V.; Carter, T. Integrating GSI and mi for Reliable Rockmass Strength Estimation: Integrating GSI and mi. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 11217–11260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M. 2010. Practical Estimates of Tensile Strength and Hoek–Brown Strength Parameter mi of Brittle Rocks. Rock Mech. Rock Eng., 2010, 43. 167-184. [CrossRef]

- Elmo, D. Evaluation of a Hybrid FEM/DEM Approach for Determination of Rock Mass Strength Using a Combination of Discontinuity Mapping and Fracture Mechanics Modelling, with Particular Emphasis on Modelling of Jointed Pillars. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Elmo, D.; Yang, B.; Stead, D.; Rogers, S. A discrete fracture network approach to rock mass classification. In Challenges and Innovations in Geomechanics, Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of IACMAG-Volume 1, Turin, Italy, 5–8 May 2021; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 854–861. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, N. Reflections on Unrealistic Continuum Modelling; NB&A: Oslo, Norway, 2025; 30p. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, R.; Harrison, J.P. Rock mass properties for engineering design. Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology and Hydrogeology. 2003, 36. 5-16. 10.1144/1470-923601-031.

- Yang, B.; Elmo, D. Why engineers should not attempt to quantify GSI. Geosciences 2022, 12, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, T.; Elmo, D.; Rogers, S. Influence of data analysis when exploiting DFN model representation in the application of rock mass classification systems. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering 2018, 10, Issue 6, 1046–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniawski, Z.T. Rock mass classification in rock engineering. In Exploration for Rock Engineering; Bieniawski, Z.T., Ed.; Balkema: Cape Town, South Africa, 1976; pp. 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, N.; Lien, R.; Lunde, J. Engineering classification of rock masses for the design of tunnel support. Rock Mech. 1974, 6, 189–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjigeorgiou, J.; Harrison, J.P. Uncertainty and sources of error in rock engineering. Harmonising Rock Engineering and the Environment - Proceedings of the 12th ISRM International Congress on Rock Mechanics. 2012, 2063-2067. [CrossRef]

- Elmo, D. The Bologna Interpretation of Rock Bridges. Geosciences 2023, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewick, R.P.; Elmo, D. Size effect and rock mass strength. Can. Geotech. J. 2025, 62, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaieli, K.; Hadjigeorgiou, J.; Grenon, M. Estimating geometrical and mechanical REV, based on synthetic rock mass models at Brunswick Mine. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 2010, 47: 915–926. [CrossRef]

- Elmo, D. 2012. FDEM & DFN modelling and applications to rock engineering problems. Faculty of Engineering, Turin University, Italy (MIR 2012 - XIV Ciclo di Conferenze di Meccanica e Ingegneria delle Rocce——Nuovi metodi di indagine, monitoraggio e modellazione degli ammassi rocciosi). November 21st - 22nd, 2012.

- Stavrou, A.; Vazaios, I.; Murphy, W.; Vlachopoulos, N. Refined approaches for estimating the strength of rock blocks. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering, 2019, 37: 5409–5439(2019). [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, K.; Han, K. Scale dependency and anisotropy of mechanical properties of jointed rock masses: Insights from a numerical study. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 2023, 82: 114. [CrossRef]

- Yiouta-Mitra, P.; Dimitriadis, G.; Nomikos, P. Size effect on triaxial strength of randomly fractured rockmass with discrete fracture network. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 2023, 82:8. [CrossRef]

- Bear, J. Dynamics of Fluids in Porous Media; Courier Corporation: North Chelmsford, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto da Cunha, A. Scale Effects in Rock Masses. London CRC Press, 1993, pp366.

- Bewick, R.P.; Elmo, D. Does size effect matter? In Proceedings of the RockEng 2025 Conference, August 2025, Montreal, Canada.

- Elmo, D.; Stead, D. An integrated numerical modelling–discrete fracture network approach applied to the characterisation of rock mass strength of naturally fractured pillars. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2010, 43, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erharter, G.; Elmo, D. 2025. Is Complexity the Answer to the Continuum vs. Discontinuum Question in Rock Engineering? Rock Mech. Rock Eng, 1–19.

- Kay, J.; King, M. Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making Beyond the Numbers. WW Norton, 2020, pp 384.

- Einstein, A. Autobiographical notes, in Albert Einstein: Philosopher Scientist. 1959, Schilpp, P. A. (ed.) NY, Harper and Row.

- Taleb, N. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. Random House, 2010; p. 400. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgman, P.W. The Logic of Modern Physics. 1927, New York: Macmillan.

- Deere, D.U.; Hendron, A.J.; Patton, F.D.; Cording, E.J. Design of surface and near-surface construction in rock. In Proceedings of the Failure and Breakage of Rock-Eighth Symposium on Rock Mechanics, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 15–17 September 1967; pp. 237–302. [Google Scholar]

- Pells, P.J.; Bieniawski, Z.T.; Hencher, S.R.; Pells, S.E. Rock quality designation (RQD): Time to rest in peace. Can. Geotech. J. 2017, 54, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.P. Rock engineering design and the evolution of Eurocode 7. In Proceedings of the EG50 2017—Engineering Geology 50 Conference, Portsmouth, UK, 5–7 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ambah, E.; Elmo, D.; Znag, Y. Fracture Undulation Modelling in Discontinuum Analysis: Implications for Rock-Mass Strength Assessment. Geotechnics 2025, 5(3), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, J.; Stacey, P. 2009. Guidelines for Open Pit Slope Design. 2009, CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne.

- Tolstoy, L. War and Peace. Wordsworth Editions, 1993.

- Legasov, V. Personal audio files. Transcribed by HBO, Chernobyl, 1988.

| Discipline | Calibration | Validation | Additional Layer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement & Instrumentation |

Adjusting an instrument against known standards (e.g., calibrating a scale with certified weights) | Confirming the instrument performs correctly across its operating range. The focus is more on equipment accuracy than predictive models | n/a |

| Computational Modelling |

Adjusting parameters to match known behaviour | Comparing predictions to independent experimental/field data | Verification. It addresses whether equations are solved correctly |

| Machine Learning & Data Science |

Fitting model parameters to training data (Training, analogous to calibration). | Testing on a validation set during model development to tune hyperparameters | Testing. Final evaluation on completely independent test data (closest to validation in other fields) |

| Property | Rock Mass A | Rock Mass B | Rock Mass C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density (ton/m3) | 2.70 | 2.66 | 2.61 |

| Uniaxial Compressive strength, UCS (MPa) | 67.20 | 69.9 | 96.50 |

| Indirect Tension, σt (MPa) | 2.38 | 3.07 | 3.84 |

| Hoek & Brown mi (laboratory data) | 17.36 | 16.13 | 20.77 |

| Young’s Modulus, E (GPa) | 20.06 | 29.48 | 37.12 |

| Poisson ratio | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| Cohesion (MPa)* | 9.48 | 10.16 | 12.46 |

| Friction angle* | 57 | 57 | 60 |

| Fracture Energy Gf (J/m2) | 5.97 | 6.75 | 8.39 |

| * Calculated in RSData, envelope range for 200 m depth | |||

| Pre-Existing Fractures (DFN Traces) | Rock Mass A | Rock Mass B | Rock Mass C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohesion (MPa) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Friction coefficient (tangent) | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| Normal Stiffness (GPa/m) | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| Shear Stiffness (GPa/m) | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| New fractures properties | Rock Mass A | Rock Mass B | Rock Mass C |

| Cohesion (MPa) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Friction coefficient (tangent) | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Normal Stiffness (GPa/m) | 35 | 25 | 50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).