1. Introduction

Optimizing postoperative analgesia is an important component of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols as it can improve patient outcomes1,2. In current clinical practice, epidural analgesia (EA) is still considered the gold standard for perioperative analgesia in pancreatic surgery. Despite its proven efficacy in pain control, epidural analgesia presents several limitations that may hinder recovery in some patients 3–5. Sympathetic blockade resulting in hypotension often requires vasopressor support, while urinary retention necessitates prolonged catheterization. Both factors can impede early postoperative mobilization 6,7. Furthermore, there is the risk of rare but serious neurological complications such as epidural hematoma or abscesses 8. Additionally, epidural placement is technically demanding, with failure rates up to 30% of cases, it can be time-consuming and the placement itself can be burdensome for patients 9. The evolving transition from open to minimal invasive pancreatic surgery has contributed to a decreasing use of epidural analgesia within ERAS pathways10 as minimally invasive procedures are associated with a decrease in postoperative pain, and alternative analgesic strategies were developed. However, studies of multimodal regimens have shown that pain control needs further optimization 11. Alternative multimodal strategies, including continuous wound infiltration catheters, have shown promise. However, pain control remains inferior to epidural analgesia, particularly during the first 24 hours postoperatively, and the use of multiple catheters may negatively affect mobilization and patient satisfaction12,13. Recently, methadone has gained attention in early recovery programs given its unique role of the agonistic effect on opioid receptors combined with non-competitive antagonism of the NMDA receptor14. Earlier studies demonstrate that the use of perioperative methadone in other types of surgery is safe and provides excellent prolonged pain control, resulting in lower postoperative opioid requirements15–17. However, in pancreatic surgery the perioperative use of methadone has not been previously reported.

This retrospective cohort study aims to compare postoperative outcomes between EA, multimodal analgesia without methadone (MA), and multimodal analgesia with methadone (MM) in patients undergoing pancreatic resections. We hypothesized that multimodal analgesia, particularly with methadone, would result in comparable pain control and enhanced functional recovery compared to EA, while minimizing opioid-related side effects and ICU burden.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This retrospective cohort study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee (METC) of the Catharina Hospital and Medical Ethics Committees United (MEC-U, W23.265) and is reported according to the STROBE criteria18. Surgical data were prospectively collected in the Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Audit (DPCA), coordinated by the Dutch Institute for Clinical Auditing (DICA). The DPCA collects and analyzes clinical data from patients undergoing elective surgical treatment for primary pancreatic cancer. These data were retrospectively complemented with perioperative and postoperative data from the medical records, including administered anesthetic and analgesic drugs, postoperative pain scores, opioid administration and functional recovery-related parameters.

2.2. Participants

All consecutive adult patients undergoing laparoscopic, robotic, or open pancreatic cancer surgery at Catharina Hospital Eindhoven between January 2020 and February 2024 were screened. Patients were included if they received either thoracic epidural analgesia or multimodal analgesia (with or without methadone), according to institutional protocols. Patients were excluded if surgery was aborted due to intraoperative detection of inoperable disease, if multiple major abdominal procedures were performed concurrently, or if postoperatively sedated up until postoperative day 2.

2.3. Analgesic Procedures

All patients received an analgesic regimen in accordance with the standardized institutional protocol of our hospital. General anesthesia was induced with sufentanil, propofol and rocuronium, and maintained using propofol. All patients received postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) prophylaxis with both dexamethasone 8 mg and granisetron 1mg iv, and all patients were postoperative consulted and monitored by the Acute Pain Service (APS). All study patients received paracetamol 1000mg TID and metamizole 1000mg TID, unless contraindicated, as part of the standard protocol.

2.3.1. Epidural Analgesia (EA)

A thoracic epidural catheter was inserted prior to anesthesia induction with placement confirmed via standard clinical testing. Intra- and postoperatively, EA patients received continuous infusion of bupivacaine 0,125% with additional sufentanil 1 µg/ml at an infusion rate of 4 to 8 ml/h.

Multimodal Analgesia Without Methadone (MA)

Patients received intraoperative sufentanil boluses (5 µg/mL), continuous esketamine (0.125 mg/kg/h), and lidocaine (1.5 mg/kg/h). Postoperatively, these patients received oxycodone PRN. In cases where oxycodone provided insufficient pain relief, patient controlled intravenous analgesia (PCIA) with morphine or piritramide 1 mg/ml and droperidol 0.04 mg/ml with optional esketamine 0.4 mg/ml was offered. Continuous wound infiltration was administered using an elastomeric pump that delivered bupivacaine 0.125% at a standard infusion rate of 6.25 mg/h (5 ml/h), with a maximum rate of 10 mg/h (8 ml/h).

2.3.2. Multimodal Analgesia With Methadone (MM)

Patients received the same multimodal regimen, but now including methadone (0.2 mg/kg) at induction, with minimized use of additional opioids intra- and postoperatively. Postoperatively, oxycodone and PCIA were provided similarly to the MA group.

2.4. Outcome Measures

The primary outcome of this study was postoperative pain using the daily maximum pain scores (Numeric Rating Scale; NRS; range: 0-10) on postoperative day (POD) 0, 1 and 2. Secondary outcome measures were postoperative opioid consumption (in oral morphine equivalents), vasopressor requirements, length of ICU and hospital stay, time until mobilization, complications according to Clavien-Dindo, PONV, time to mobilization, time to first passage of stool and duration of urinary bladder catheterization.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared between patients who received EA and patients who received multimodal analgesia with and without methadone using a χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test, independent t test or Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate. Continuous variables were checked for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

First, we built an univariable linear mixed-effects model with maximum NRS score on day 0, 1 and 2 as the dependent variable, using day of measurement as a random effect nested within patient. Akaike’s Information Criterion was used to determine the best fit for a model with a random intercept, a random slope or both [

19]. Next, univariable poisson or gamma regression models were built where applicable, based on distribution of the outcome variables and when applicable, models were compared using Akaike’s Information Criterion for the best fit

20–22. Dependent variables were respectively first day of stool, number of days of vasopressor requirement, first day of mobilization, number of days with PONV, number of days with CAD and total amount of opioids in morphine equivalents used within the first three postoperative days. An univariable logistic regression was built using complications (Clavien Dindo ≥3a) as the dependent variable. Finally, length of stay was analyzed after inspection of the data. For further analysis, length-of stay was right-censored in case of in-hospital mortality, at 30 days. Additionally, length of ICU stay was truncated at 30 days as this has been shown to enhance model performance and was considered clinically reasonable as well

20. A negative binomial regression model, a poisson regression model and gamma regression model were tested for the best fit for ICU length of stay and hospital length of stay

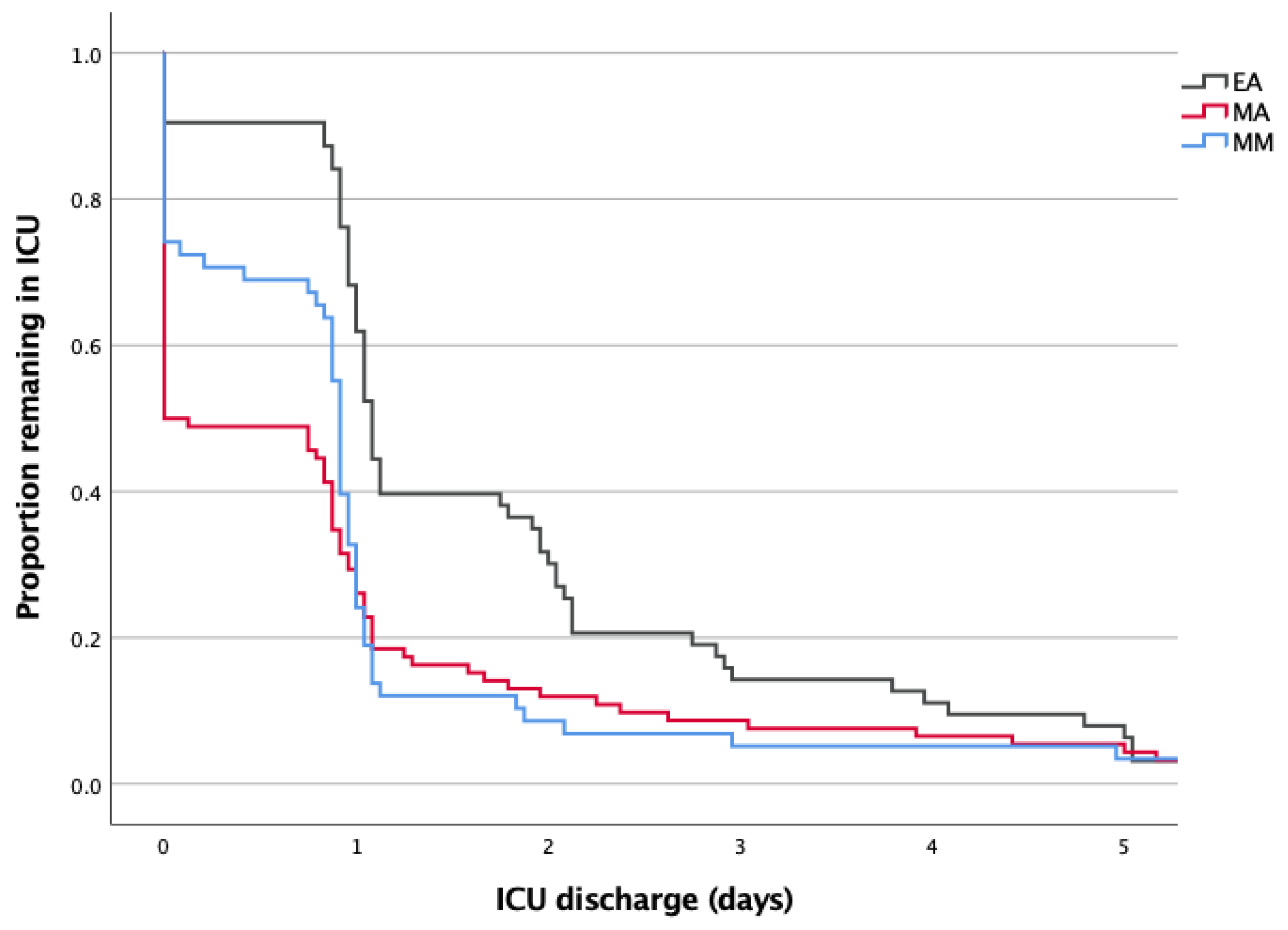

20. A Kaplan Meier curve was made to visualize difference in length of stay for the different types of analgesia.

Afterwards, we built multivariable models for all previously mentioned models. Variables under consideration for inclusion in our multivariable model, were checked for collinearity using a correlation matrix. Those variables deemed to be collinear (defined as a correlation of ≥ 0.70) were either combined into a single variable or removed. All non-collinear variables were entered into the models. The included variables were selected based on clinical relevance and included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), duration of the procedure, ASA physical status and procedure type (laparoscopic or robotic vs open). For the models using NRS and first day of stool, we also added preoperative opioid use. For the model using days of vasopressor requirement, we added preoperative use of antihypertensive drugs to the included variables.

A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were two-tailed. The statistical analyses were performed with R (Version 2024.09.1+394 – © 2024-11-04, R, Inc., for Macintosh) 23.

2.5.1. Missing Data

Missing data were tracked and filled by patient status review were possible. As complete case analyses are known to lead to biased effect estimates, we planned to impute missing values in case of >2% missingness in our outcome measures or confounders 24.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

Based on our sampling criteria a total of 231 patients were scheduled for pancreatic cancer surgery between 1 January 2020 and 31 January 2024. A total of 213 patients were included in the analyses: 63 (30%) in the EA group, 92 (43%) in the MA group and 58 (27%) in the MM group (

Figure 1). 2.6% of data was missing (

Supplementary Table S1).

Baseline characteristics of the patients in all study groups are presented in

Table 1. Groups were comparable for sex distribution, age, height, weight, ASA classification, the prevalence of hypertension and pre-admission opioid use. The MA group had a modestly higher median BMI (p = 0.049). Surgical modality differed significantly (p < 0.001), with open surgery predominating in the EA group (98%). In the MM group 62% of procedures were open, while in the MA group minimally invasive surgery accounted for 88% of procedures. Duration of surgery and general anesthesia did not differ significantly among the groups.

3.2. Postoperative Pain

The daily medians of maximum pain scores are presented in table 2. In the multivariate linear mixed-effect model, the MM group demonstrated higher pain scores compared to the EA group (NRS 2.22, 95% CI [1.22, 3.90], p = 0.01). The MA group also displayed higher pain scores relative to EA; however, this difference was not statistically significant (NRS 2.06, 95% CI [0.99, 4.30], p = 0.06).

3.3. Opioid Consumption

Postoperative opioid consumption was quantified in terms of oral morphine equivalents. Across POD 0–2, the MM group showed opioid consumption comparable to EA (OR 0.99, 95% CI [0.98, 1.00], p = 0.20). In contrast, the MA group required significantly fewer opioids compared to EA (OR 0.97, 95% CI [0.96, 0.98], p < 0.001).

3.4. Length of Stay

The median [IQR] hospital length of stay in the EA group was 10.0 days [7.9, 18.8] vs. 8.0 days [5.2, 15.4] in the MA group and 8.8 days [6.2, 17.8] in the MM group. Multivariable analysis revealed no significant differences between groups. ICU length of stay was similarly nonsignificant, with median [IQR] stays of 1.1 days [1.0, 2.1] in the EA group, 0.0 days [0.0, 1.0] in the MA group and 0.9 days [0.0, 1.0] in the MM group.

Despite similar median durations, the distribution of ICU stay varied markedly (

Figure 2 and

Table 3). In the EA group, 42.9% of patients required ≥2 days in ICU and only 3.2% had no ICU admission. In contrast, 29.3% of MM patients avoided ICU entirely, with just 5.2% requiring >1 day. Over half of patients in the MA group had no ICU stay.

The hospital readmission rates within 30 days after surgery were comparable across all study groups (

Table 2). ICU readmission rates were higher in the MA group but the difference was not statistically significant.

3.5. Vasopressor Requirements

Compared to EA, both the MA and MM group demonstrated a reduction in median days of norepinephrine usage (

Table 2), which was confirmed in multivariate analysis (MA: OR 0.28, 95% CI [0.12, 0.65], p < 0.001; OR 0.02,95% CI [0.00, 0.13], p < 0.001).

3.6. Functional Recovery and Related Side Effects

The median time to mobilization was shorter in both the MA and MM group (

Table 2). Multivariate regression analysis showed that the MA group mobilized significantly earlier than the EA group (OR 0.52, 95% CI [0.28, 0.95], p = 0.03). The MM group, while demonstrating faster mobilization than EA, did not reach statistical significance (OR 0.77, 95% CI [0.49, 1.22], p = 0.27).

Recovery of bowel function, assessed by time to first stool, differed slightly among the groups. Multivariate analysis revealed no significant difference for the MM group compared to EA (OR 0.87, 95% CI [0.72, 1.04], p = 0.13). In contrast, the MA group demonstrated a significantly shorter time to bowel recovery compared to EA (OR 0.76, 95% CI [0.60, 0.96], p = 0.02).

The duration of urinary bladder catheterization was significantly reduced in the MM and MA groups compared to EA. The median duration was longest by 4.0 days (IQR [3.2, 4.3]) in the EA group, followed by 1.9 days (IQR [1.1, 3.0]) in the MM group and 1.2 days (IQR [1.0, 2.7]) in the MA group. Regression analysis confirmed significantly shorter catheterization times in the MM group (OR 0.70, 95% CI [0.51, 0.95], p = 0.03) and the MA (OR 0.54, 95% CI [0.36, 0.82], p = 0.003).

PONV occurred infrequently across all groups, without statistically significant differences in days with PONV between the groups.

Table 2.

Postoperative outcomes.

Table 2.

Postoperative outcomes.

| Outcome |

|

|

|

|

Univariate analysis |

|

|

Multivariate analysis |

|

| Postoperative pain |

Median NRS max [IQR] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

POD 0 |

POD 1 |

POD 2 |

|

NRS max |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

|

NRS max |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

| EA |

0.0 [0.0, 2.0] |

3.0 [1.0, 4.5] |

3.0 [2.0, 5.0] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MA |

4.0 [2.0, 6.0] |

4.0 [2.0, 5.0] |

3.0 [2.0, 5.0] |

|

2.45 |

(1.47–4.08) |

< 0.001 |

|

2.06 |

(0.99–4.30) |

0.06 |

| MM |

4.0 [2.0, 5.8] |

3.0 [2.0, 4.0] |

3.0 [2.0, 4.0] |

|

2.21 |

(1.25–3.90) |

0.01 |

|

2.22 |

(1.22–4.01) |

0.01 |

| Opioid consumption |

Median total MorfEq per day [IQR] |

|

|

MorfEq per 10 mg |

|

|

MorfEq per 10 mg |

|

| |

POD 0 |

POD 1 |

POD 2 |

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

| EA |

105.0 [60.0, 150.0] |

0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

0.0 [0.0, 3.8] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MA |

196.5 [150.0, 261.0] |

0.0 [0.0, 13.0] |

0.0 [0.0, 13.5] |

|

0.97 |

(0.96–0.98) |

< 0.001 |

|

0.97 |

(0.96–0.98) |

< 0.001 |

| MM |

134.3 [96.4, 171.4] |

0.0 [0.0, 7.5] |

0.0 [0.0, 7.5] |

|

0.99 |

(0.98–1.00) |

0.23 |

|

0.99 |

(0.98–1.00) |

0.20 |

| Length of Hospital Stay |

Median days [IQR] |

Re-admission rate n (%) |

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

| EA |

10.0 [7.9, 18.9] |

14 (22.2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MA |

8.0 [5.2, 15.4] |

19 (20.7) |

|

|

1.02 |

(1.00–1.03) |

0.07 |

|

1.01 |

(0.99–1.02) |

0.54 |

| MM |

8.8 [6.2, 17.8] |

11 (19.0) |

|

|

1.01 |

(0.99–1.02) |

0.50 |

|

1.00 |

(0.99–1.02) |

0.76 |

| Length of ICU stay |

Median days [IQR] |

Re-admission rate n (%) |

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

| EA |

1.1 [1.0, 2.1] |

0 (0.0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MA |

0.0 [0.0, 1.0] |

8 (8.7) |

|

|

1.72 |

(1.01–2.92) |

0.05 |

|

0.84 |

(0.56–1.28) |

0.42 |

| MM |

0.9 [0.0, 1.0] |

1 (1.7) |

|

|

1.11 |

(0.72–1.73) |

0.63 |

|

0.97 |

(0.75–1.26) |

0.84 |

| Time to first stool |

Median days [IQR] |

|

|

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

| EA |

5.0 [4.0, 6.0] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MA |

4.0 [3.0, 5.0] |

|

|

|

0.80 |

(0.69–0.93) |

< 0.001 |

|

0.76 |

(0.60–0.96) |

0.02 |

| MM |

4.0 [3.0, 5.0] |

|

|

|

0.90 |

(0.76–1.06) |

0.19 |

|

0.87 |

(0.72–1.04) |

0.13 |

| Time until mobilisation |

Median days [IQR] |

|

|

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

| EA |

1.0 [0.5, 1.0] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MA |

0.0 [0.0, 1.0] |

|

|

|

0.49 |

(0.32–0.73) |

< 0.001 |

|

0.52 |

(0.28–0.95) |

0.03 |

| MM |

0.0 [0.0, 1.0] |

|

|

|

0.68 |

(0.45–1.03) |

0.07 |

|

0.77 |

(0.49–1.22) |

0.27 |

| Norepinephrine support |

Median days [IQR] |

|

|

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

| EA |

2.0 [0.0, 3.0] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MA |

0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

|

|

|

0.13 |

(0.08–0.21) |

< 0.001 |

|

0.28 |

(0.12–0.65) |

< 0.001 |

| MM |

0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

|

|

|

0.01 |

(0.00–0.08) |

< 0.001 |

|

0.02 |

(0.00–0.13) |

< 0.001 |

| Urinary catheterization |

Median days [IQR] |

|

|

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

| EA |

4.0 [3.2, 4.3] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MA |

1.2 [1.0, 2.7] |

|

|

|

0.48 |

(0.36–0.65) |

< 0.001 |

|

0.54 |

(0.36–0.82) |

< 0.001 |

| MM |

1.9 [1.1, 3.0] |

|

|

|

0.67 |

(0.50–0.91) |

0.01 |

|

0.70 |

(0.51–0.95) |

0.03 |

| PONV |

Median days [IQR] |

|

|

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

| EA |

0.0 [0.0, 1.5] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MA |

0.0 [0.0, 1.0] |

|

|

|

0.78 |

(0.53–1.15) |

0.21 |

|

0.65 |

(0.36–1.17) |

0.15 |

| MM |

0.0 [0.0, 1.0] |

|

|

|

0.86 |

(0.57–1.32) |

0.50 |

|

0.80 |

(0.49–1.29) |

0.36 |

| Complications |

Overall complications n (%) |

30 day mortality n (%) |

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

|

OR |

95% CI |

Pvalue

|

| EA |

33 (52.4) |

1 (1.6) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MA |

49 (53.3) |

4 (4.3) |

|

|

0.82 |

(0.43–1.57) |

0.55 |

|

0.62 |

(0.22–1.70) |

0.35 |

| MM |

32 (55.2) |

3 (5.2) |

|

|

1.01 |

(0.49–2.08) |

0.98 |

|

0.86 |

(0.38–1.95) |

0.72 |

Table 3.

Days of ICU stay for each study group.

Table 3.

Days of ICU stay for each study group.

| Study Group |

Length of ICU stay |

| |

0 days |

1 day |

≥ 2 days |

| EA |

2 (3.2) |

34 (54.0) |

27 (42.9) |

| MA |

47 (51.1) |

32 (34.8) |

13 (14.1) |

| MM |

17 (29.3) |

38 (65.5) |

3 (5.2) |

3.7. Complications

Complication rates were comparable across groups. Overall complications occurred in 33 patients (52.4%) in the EA group, 32 patients (55.2%) in the MM group, and 49 patients (53.3%) in the MA group. Multivariate regression analysis showed no significant differences in major complication rates (Clavien Dindo ≥ IIIa).

4. Discussion

This study shows that a multimodal analgesic strategy with and without methadone is associated with slightly higher postoperative pain scores compared to epidural analgesia within the first 3 postoperative days after pancreatic surgery. However, median NRS were still within an acceptable range of 3-4, and pain control was achieved with, comparable or reduced amounts of opioids. Functional outcomes further support the use of multimodal analgesia. Time to mobilization and bowel recovery were significantly faster in the MA group, and both MM and MA groups exhibited shorter urinary catheterization durations and a reduced need for vasopressors. There was no difference in complication rate, PONV and length-of-stay. Although median ICU length of stay was statistically similar between groups, ICU stay distribution suggests a clinically relevant advantage for multimodal regimens. Over 40% of EA patients required ≥2 ICU days, compared to <6% in the MM group and 14% in the MA group, with the majority of multimodal patients discharged from ICU within one day.Our findings align with two meta-analyses that demonstrated comparable pain control outcomes between EA and wound catheters in patients undergoing pancreatic resection 25,26. Other RCT’s have confirmed these findings, reporting only marginally improved pain scores with EA but with increased hemodynamic instability in the immediate postoperative period 27,28. However, pain control using multimodal analgesia alone may be suboptimal in open procedures. Methadone’s extended half-life and NMDA-antagonism may provide additional and prolonged pain relief with opioid-sparing effects. Recent evidence supports methadone’s role in major abdominal procedures, demonstrating improved pain scores and reduced opioid use postoperatively 15.

This study has several strengths. First, the amount of missing data was limited as many outcome parameters were prospectively collected. Second, we studied an extensive set of recovery related postoperative outcomes. Nevertheless, this study has some obvious limitations. First, although we adjusted for potentially important confounders, residual confounding might influence the results due to the retrospective nature of this study. Particularly the strong association between analgesia type and surgical approach might have influenced the results. Second, oral morphine equivalents were not calculated for the epidural sufentanil as perfusor pump speeds and boluses were not adequately documented in the electronic patient database. Therefore, OME’s are likely underestimated in the epidural group, and postoperative opioid consumption in the multimodal and methadone groups could potentially be lower compared to EA. The amount of pain scores per patient per day varied and we chose to use a maximum rather than a mean pain score. This may also influence the evaluation of postoperative analgesia, and limit comparability with other studies. Finally, the sample size is too limited to fully explore the impact of the analgesic regimen on the secondary outcome measures.

This study implicates that multimodal analgesia with continuous wound infiltration is a valid alternative to EA in minimally invasive pancreatic surgery. In open procedures, the addition of methadone to this multimodal regimen appears to enhance functional recovery and reduce ICU burden. While statistical significance was not achieved for all outcomes, the consistent trends in both opioid consumption and functional recovery parameters warrant further study of methadone in pancreatic surgery. Prospective randomized trials focusing on opioid requirements, ICU utilization, and functional recovery are needed to define methadone’s exact role within ERAS protocols.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that multimodal analgesia regimens, combining wound catheters and methadone, are effective and well-tolerated alternative for EA in pancreatic surgery. Despite slightly higher pain scores than EA, these regimens demonstrate multiple clinical advantages, including reduced vasopressor use, shorter urinary catheterization, and earlier mobilization. Considering trends in minimally invasive surgery and ERAS pathways, epidural analgesia may no longer be the optimal analgesic option. Multimodal strategies, with methadone particular for open surgery, seem promising options for postoperative pain management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S., T.P, I.H., M.L.; methodology ,H.S. and A.A.; formal analysis, A.A...; investigation, H.S. T.P.; resources, I.H and M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.P.; writing—review and editing, H.S, A.A., I.H. and M.L Supervision H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This retrospective cohort study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee (METC) of the Catharina Hospital and Medical Ethics Committees United (MEC-U, W23.265)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived since this study evaluated standard of care, in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the corresponding author with specification of the purpose of the request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EA |

Epidural Analgesia |

| ERAS |

Enhanded Recovery After Surgery |

| MM |

Multimodal analgesia including Methadone |

| MA |

Multimodal analgesia without Methadone |

| PCIA |

Patient Controlled Intravenous Analgesia |

| PONV |

postoperative nausea and vomiting |

| MA |

Multimodal analgesia without Methadone |

References

- Pecorelli N, Nobile S, Partelli S, et al.: Enhanced recovery pathways in pancreatic surgery: State of the art. World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22, 6456–68. [CrossRef]

- Mărgărit S, Bartoș A, Laza L, et al.: Analgesic Modalities in Patients Undergoing Open Pancreatoduodenectomy—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis 2023, 12.

- Akter N, Ratnayake B, Joh DB, Chan SJ, Bonner E, Pandanaboyana S: Postoperative Pain Relief after Pancreatic Resection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Analgesic Modalities 2021, 45, 3165–73.

- Kim SS, Niu X, Elliott IA, et al.: Epidural Analgesia Improves Postoperative Pain Control but Impedes Early Discharge in Patients Undergoing Pancreatic Surgery. Pancreas 2019, 48, 719–25. [CrossRef]

- Klotz R, Larmann J, Klose C, et al.: Gastrointestinal Complications after Pancreatoduodenectomy with Epidural vs Patient-Controlled Intravenous Analgesia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg 2020, 155.

- Gramigni E, Bracco D, Carli F: Epidural analgesia and postoperative orthostatic haemodynamic changes. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2013, 30, 398–404. [CrossRef]

- Grass F, Slieker J, Frauche P, et al.: Postoperative urinary retention in colorectal surgery within an enhanced recovery pathway. Journal of Surgical Research 2017, 207, 70–6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos EME, Haumann J, Quelerij M de, et al.: Haematoma and abscess after neuraxial anaesthesia: a review of 647 cases. Br J Anaesth 2018, 120, 693–704. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermanides J, Hollmann MW, Stevens MF, Lirk P: Failed epidural: Causes and management 2012, 109, 144–54.

- Nappo G, Perinel J, Bechwaty M El, Adham M: Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Resection: Is It Really the Future? Dig Surg 2016, 33, 284–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melloul E, Lassen K, Roulin D, et al.: Guidelines for Perioperative Care for Pancreatoduodenectomy: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Recommendations 2019. World J Surg 2020, 44, 2056–84. [CrossRef]

- Groen J V., Slotboom DEF, Vuyk J, et al.: Epidural and Non-epidural Analgesia in Patients Undergoing Open Pancreatectomy: a Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2019, 23, 2439–48. [CrossRef]

- Pirie K, Traer E, Finniss D, Myles PS, Riedel B: Current approaches to acute postoperative pain management after major abdominal surgery: a narrative review and future directions. Br J Anaesth 2022, 129, 378–93. [CrossRef]

- Kharasch ED: Intraoperative methadone: Rediscovery, reappraisal, and reinvigoration? Anesth Analg 2011, 112, 13–6. [CrossRef]

- Murphy GS, Szokol JW: Intraoperative Methadone in Surgical Patients: A Review of Clinical Investigations. Anesthesiology 2019, 131, 678–92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado FC, Vieira JE, Orange FA De, Ashmawi HA: Intraoperative Methadone Reduces Pain and Opioid Consumption in Acute Postoperative Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Anesth Analg 2019, 129, 1723–32. [CrossRef]

- Mercadante S, David F, Villari P, Spedale VM, Casuccio A: Methadone versus morphine for postoperative pain in patients undergoing surgery for gynecological cancer: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Anesth 2020, 61, 109627. [CrossRef]

- Elm E von, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP: The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008, 61, 344–9. [CrossRef]

- Harre FE, Lee KL, Pollock BG: Regression Models in Clinical Studies: Determining Relationships Between Predictors and Response. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute 1988, 80, 1198–202. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verburg IWM, Keizer NF De, Jonge E De, Peek N: Comparison of regression methods for modeling intensive care length of stay. PLoS One 2014, 9.

- Moran JL, Solomon PJ: A review of statistical estimators for risk-adjusted length of stay: analysis of the Australian and new Zealand intensive care adult patient data-base. 2008 at http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/12/68.

- Akram M, Cerin E, Lamb KE, White SR: Modelling count, bounded and skewed continuous outcomes in physical activity research: beyond linear regression models. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2023, 20.

- R Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2016 at https://www.gnu.org/copyleft/gpl.html.

- Donders ART, Heijden GJMG van der, Stijnen T, Moons KGM: Review: A gentle introduction to imputation of missing values. J Clin Epidemiol 2006, 59, 1087–91. [CrossRef]

- Groen J V., Khawar AAJ, Bauer PA, et al.: Meta-analysis of epidural analgesia in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy. BJS Open 2019, 3, 559–71. [CrossRef]

- Akter N, Ratnayake B, Joh DB, Chan SJ, Bonner E, Pandanaboyana S: Postoperative Pain Relief after Pancreatic Resection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Analgesic Modalities. 2021, 45, 3165–73.

- Mungroop TH, Bond MJ, Lirk P, et al.: Preperitoneal or Subcutaneous Wound Catheters as Alternative for Epidural Analgesia in Abdominal Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2019, 269, 252–60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotz R, Larmann J, Klose C, et al.: Gastrointestinal Complications after Pancreatoduodenectomy with Epidural vs Patient-Controlled Intravenous Analgesia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg 2020, 155.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).