Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

14 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

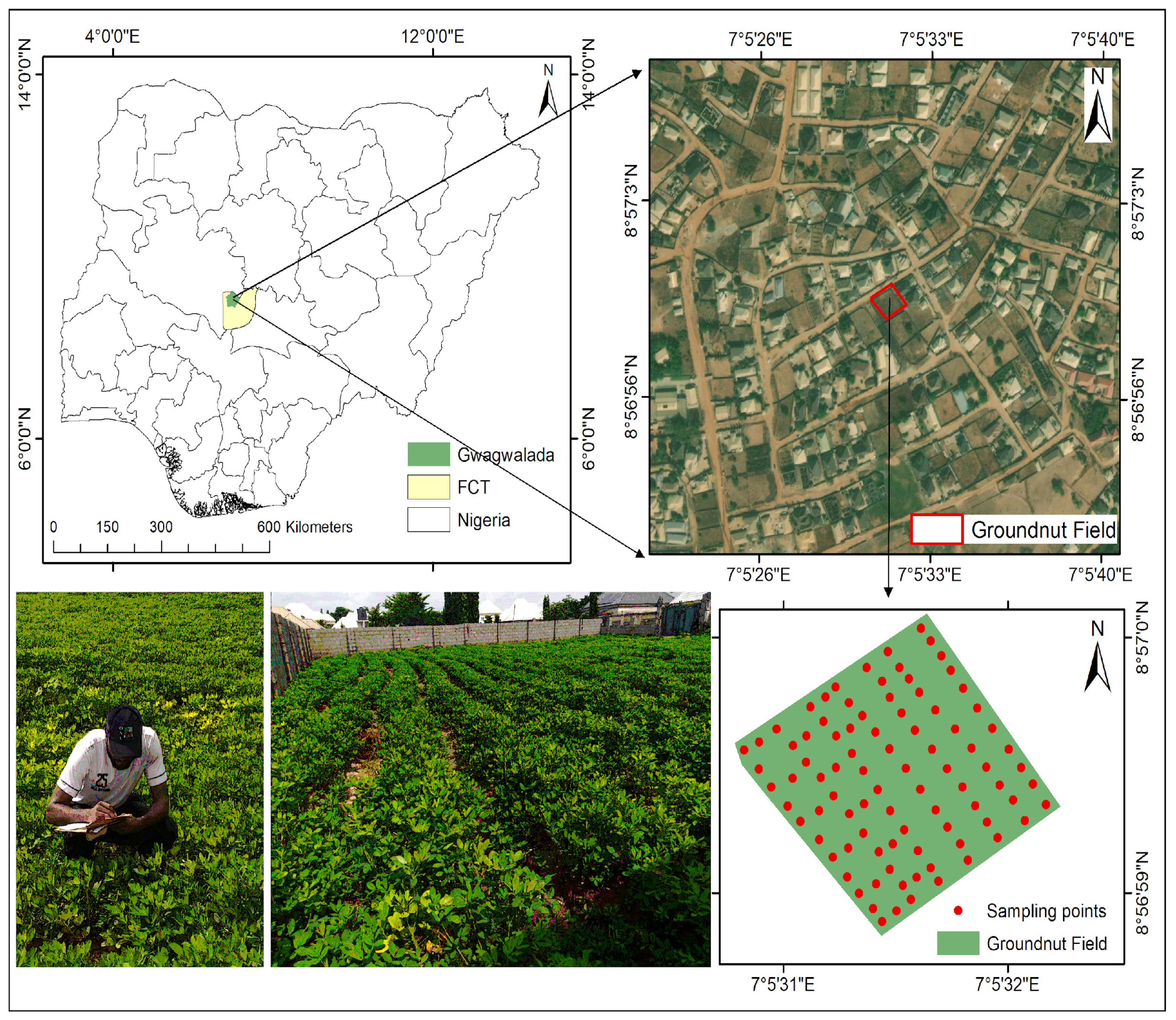

2.1. Study Area Description

2.2. Experimental Design and In Situ Data Measurement

2.3. Satellite Data

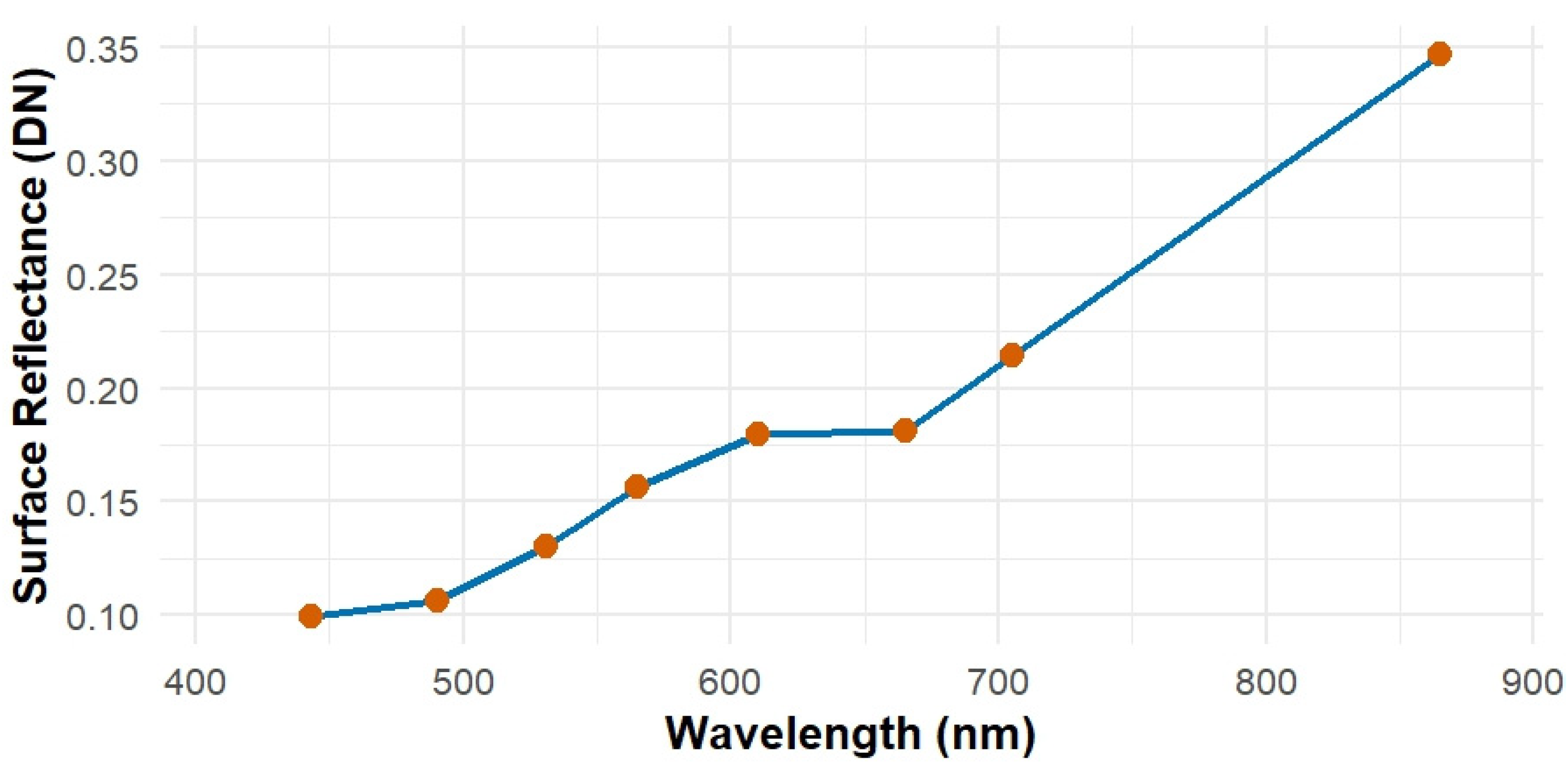

PlanetScope Imagery and Preprocessing

2.4. Remote Sensing Variables

2.5. Modeling Methods

2.6. Statistical Evaluation

2.7. Generation of LAI Prediction Maps

3. Results and Discussion

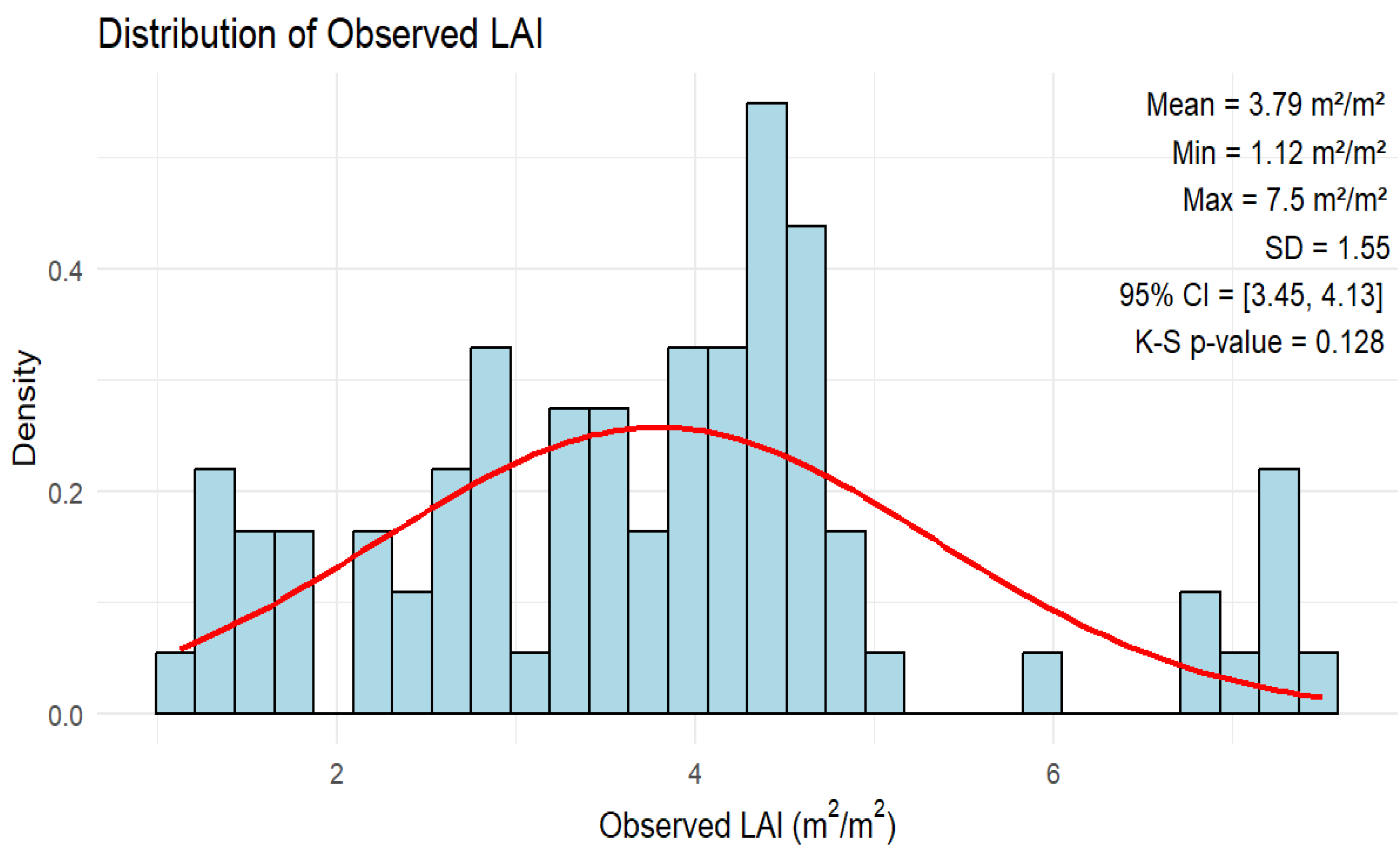

3.1. The Descriptive Statistics of Peanut LAI Measurements

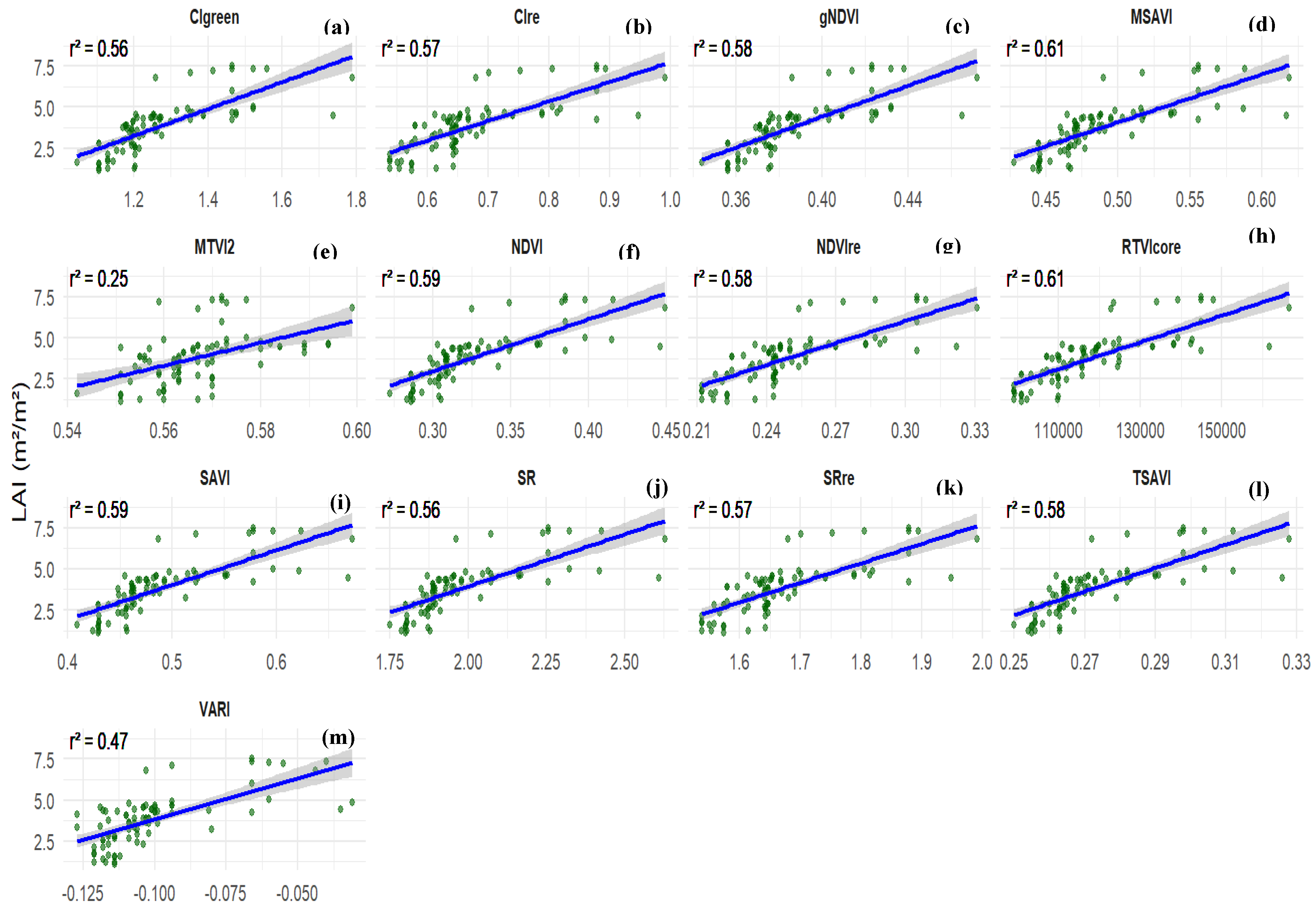

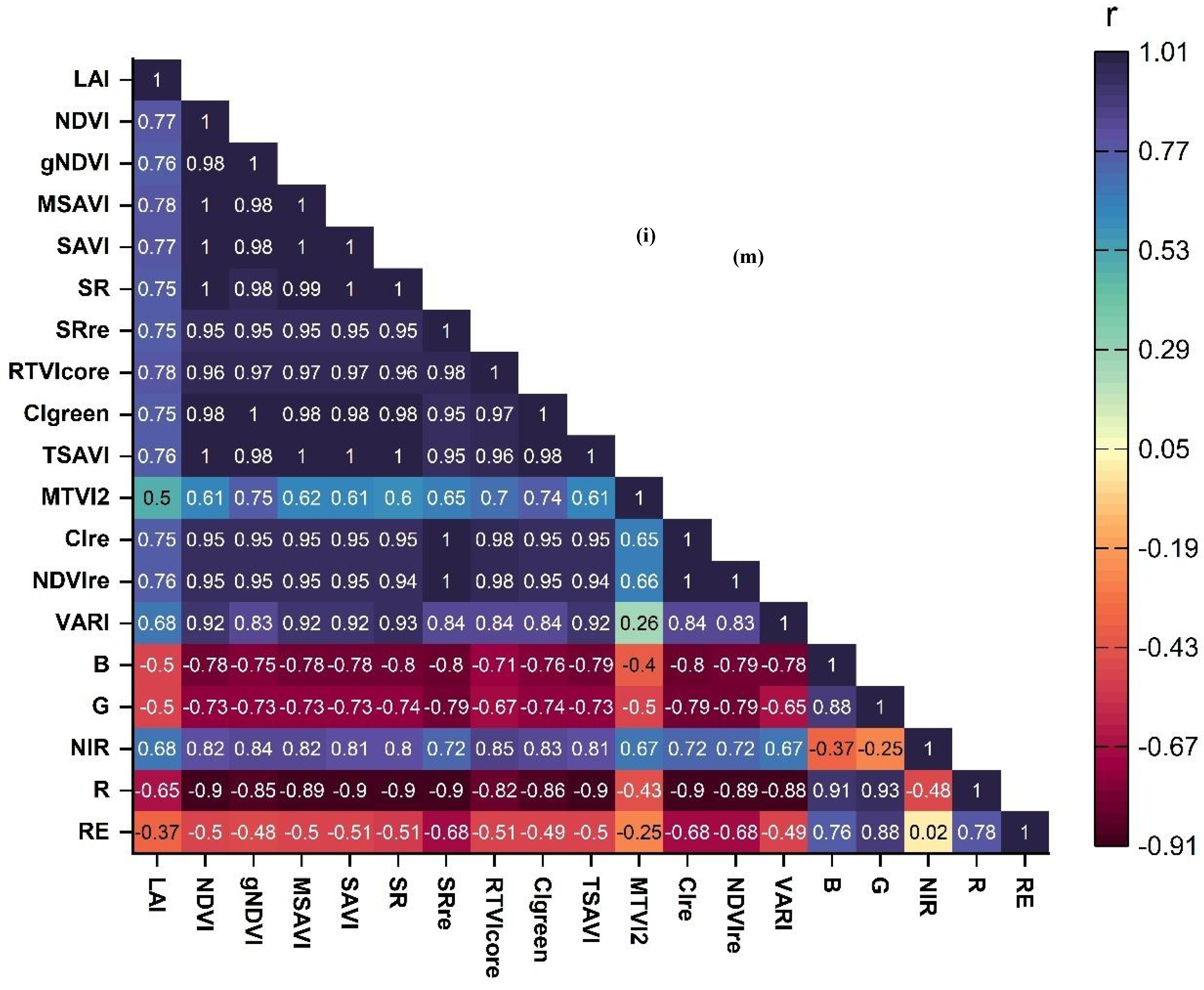

3.2. Assessment of Vegetation Indices for the Estimation of Peanut LAI

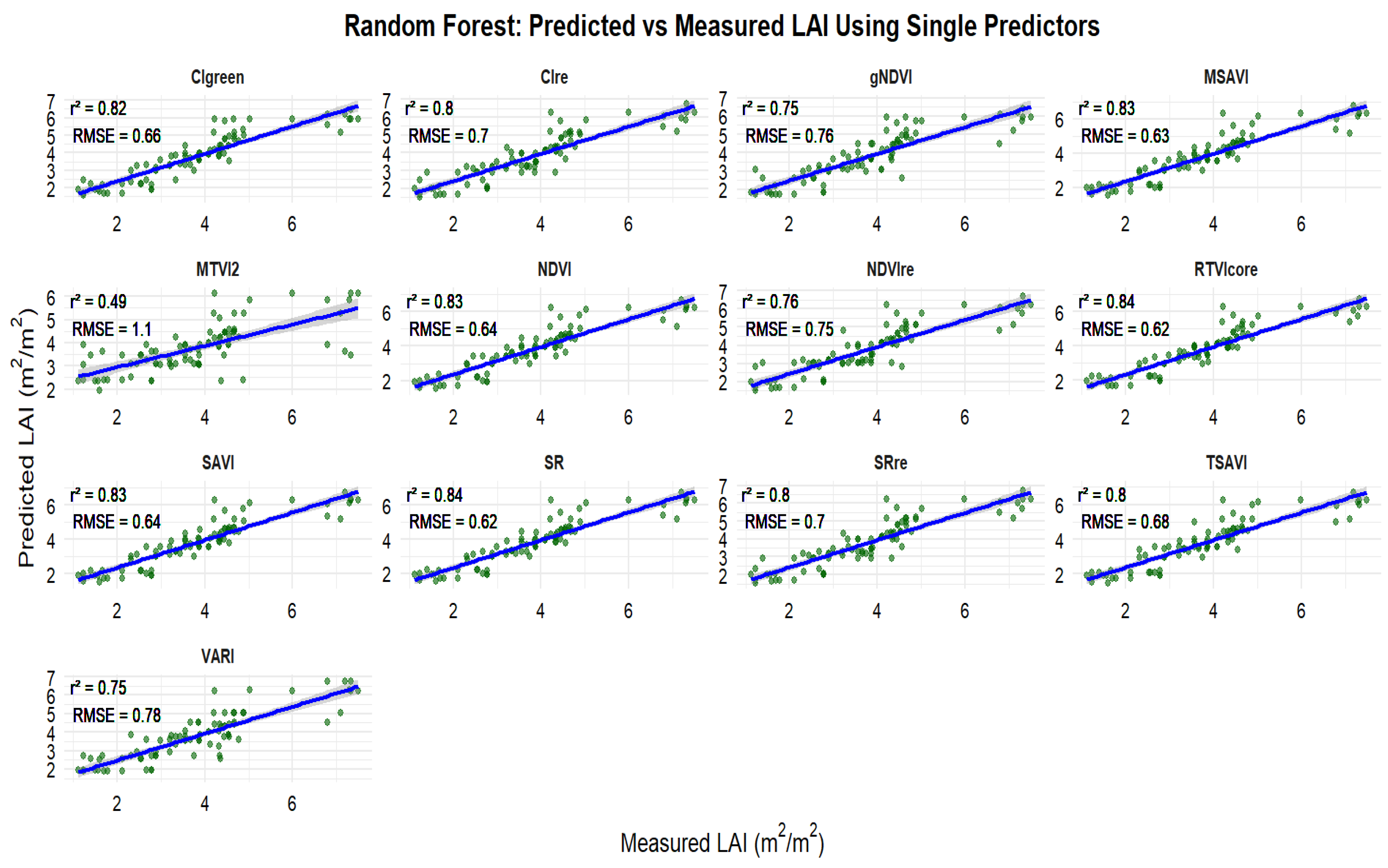

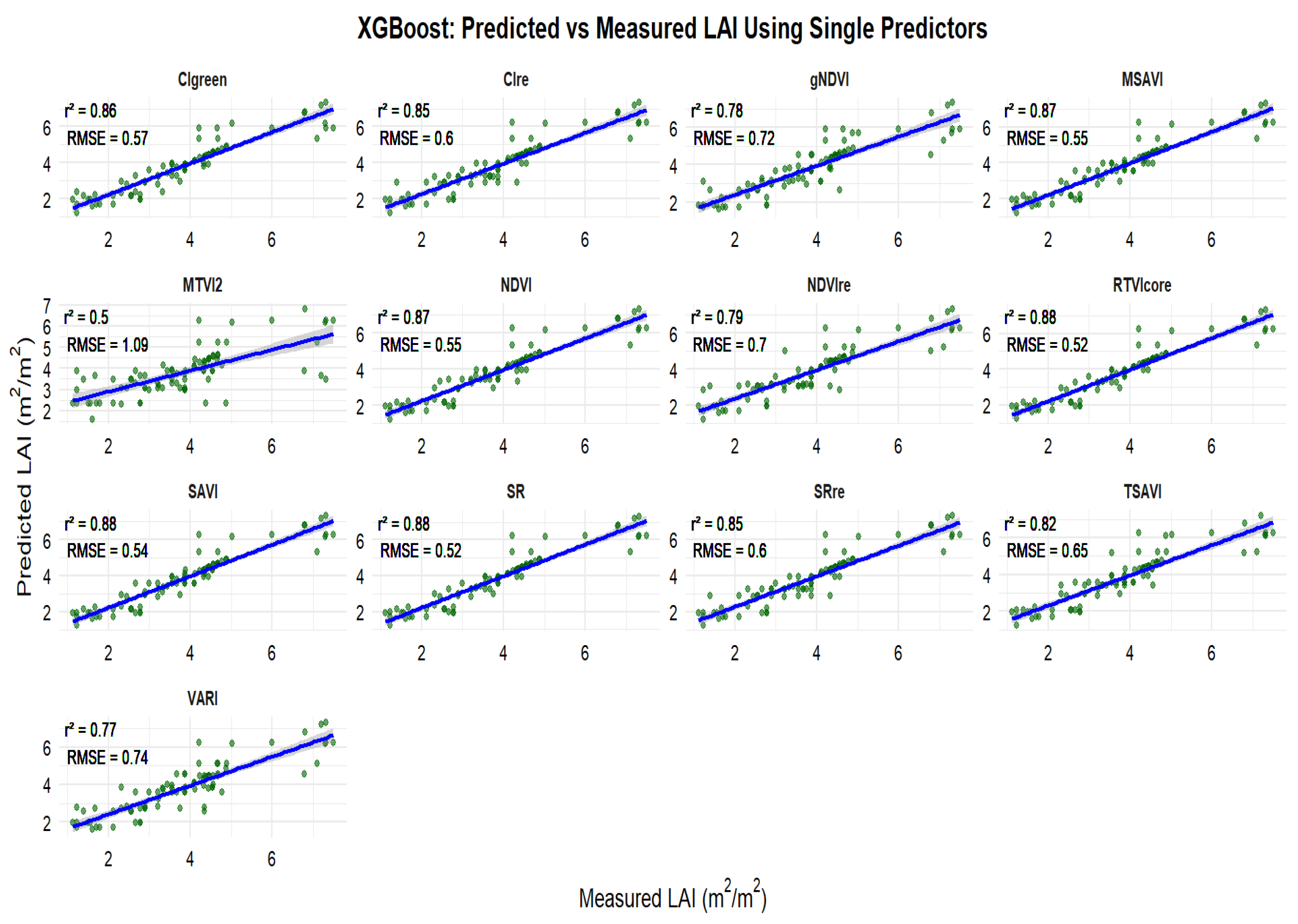

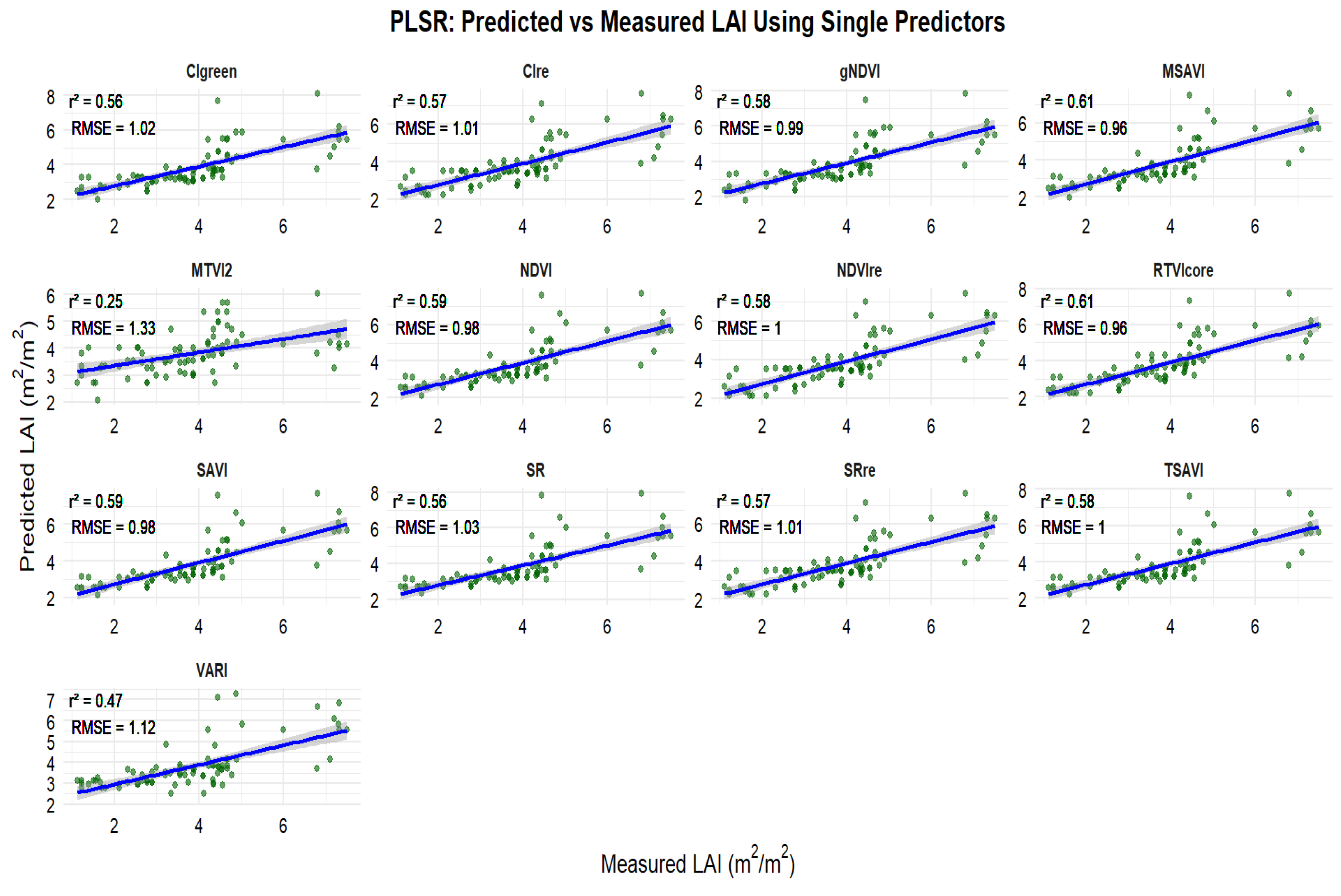

3.3. Relationships Between Observed and Predicted Peanut LAI

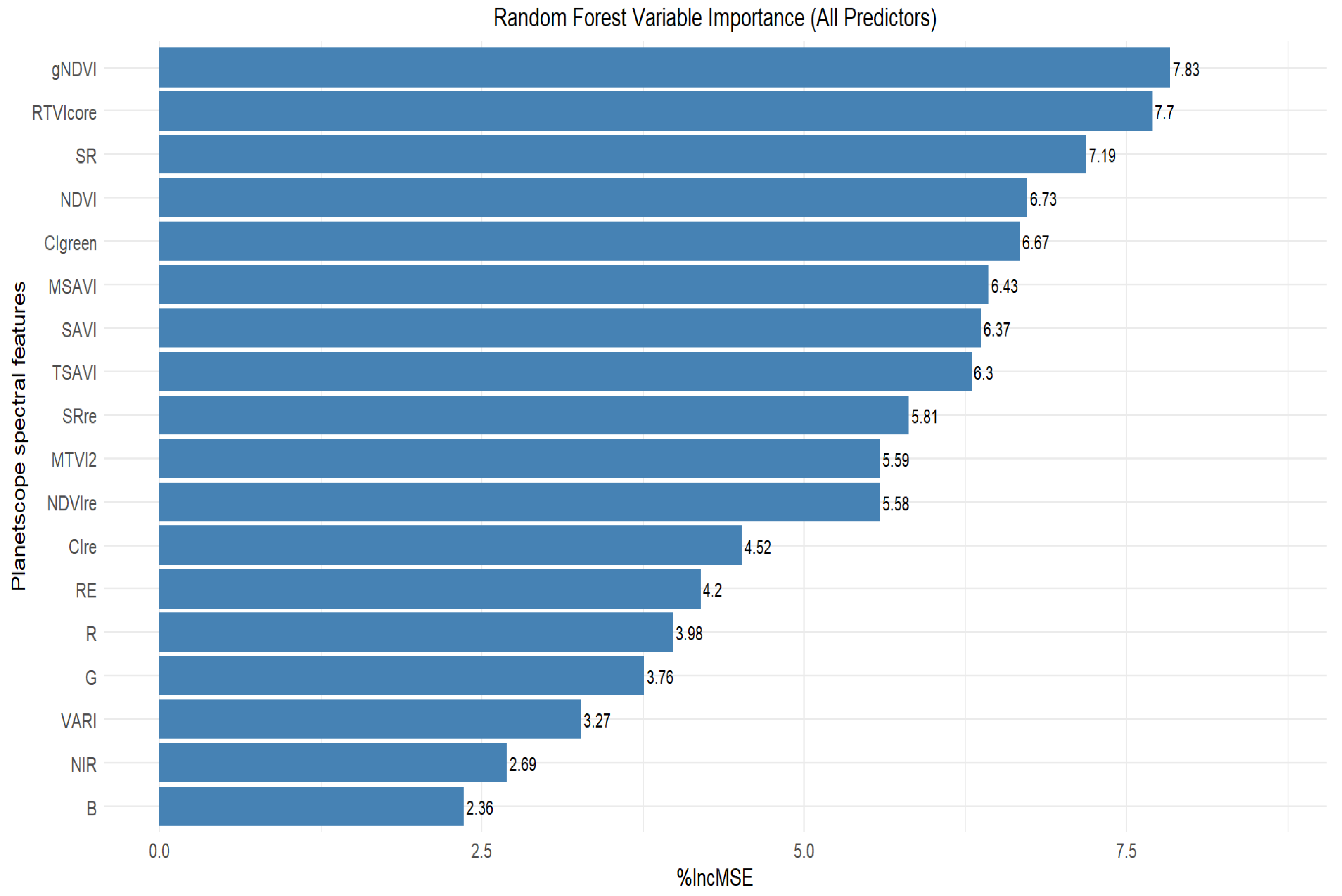

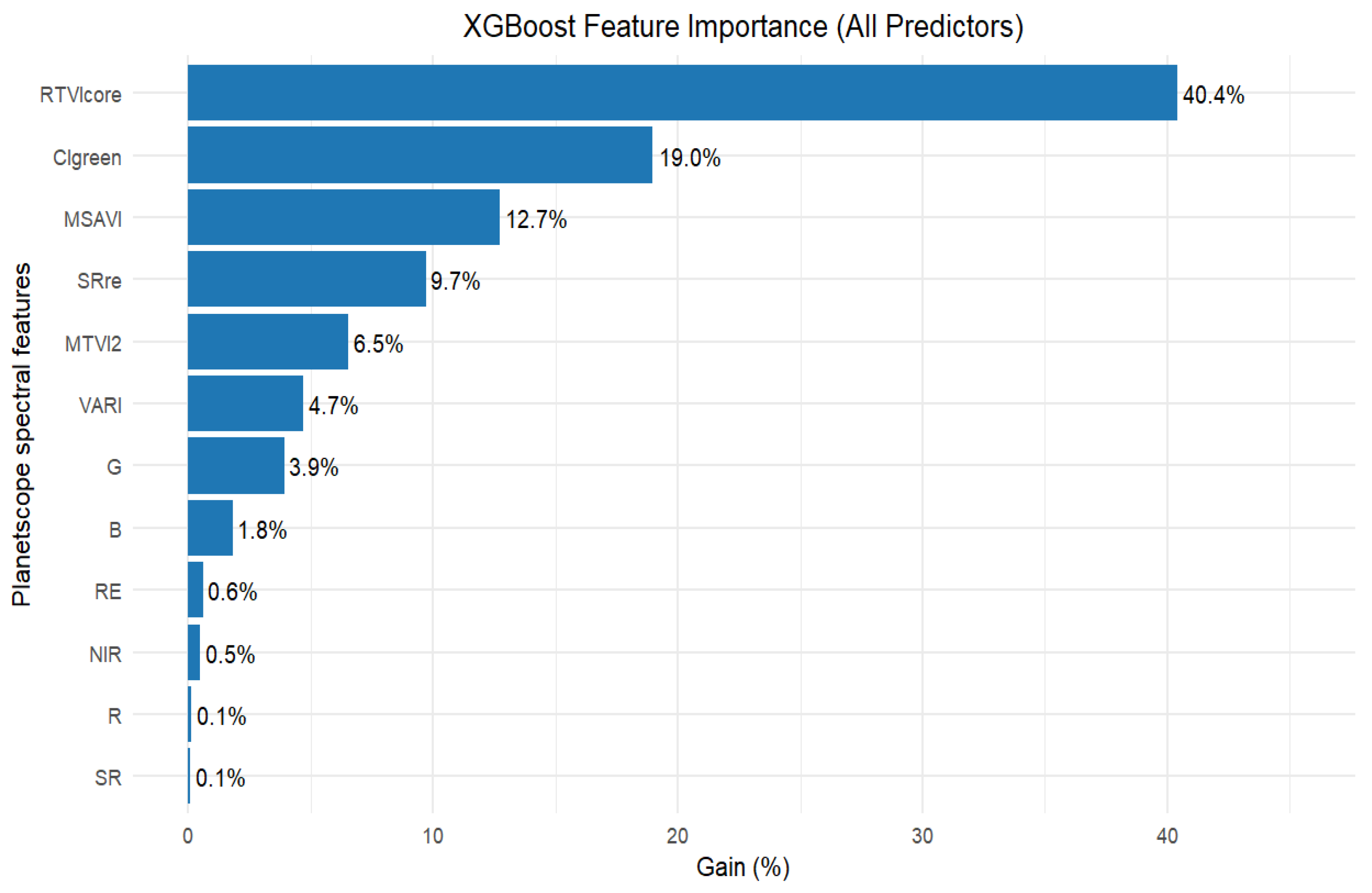

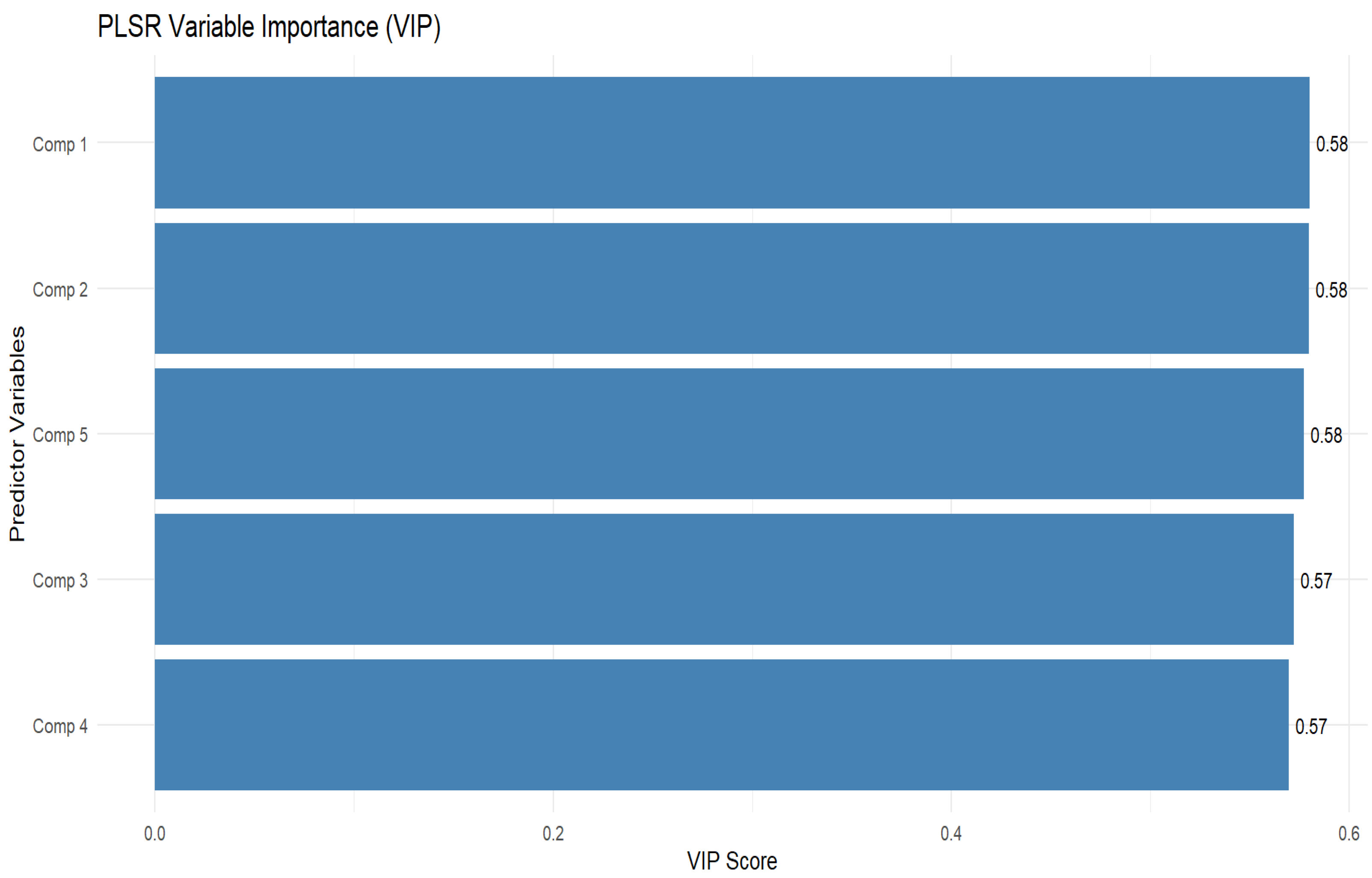

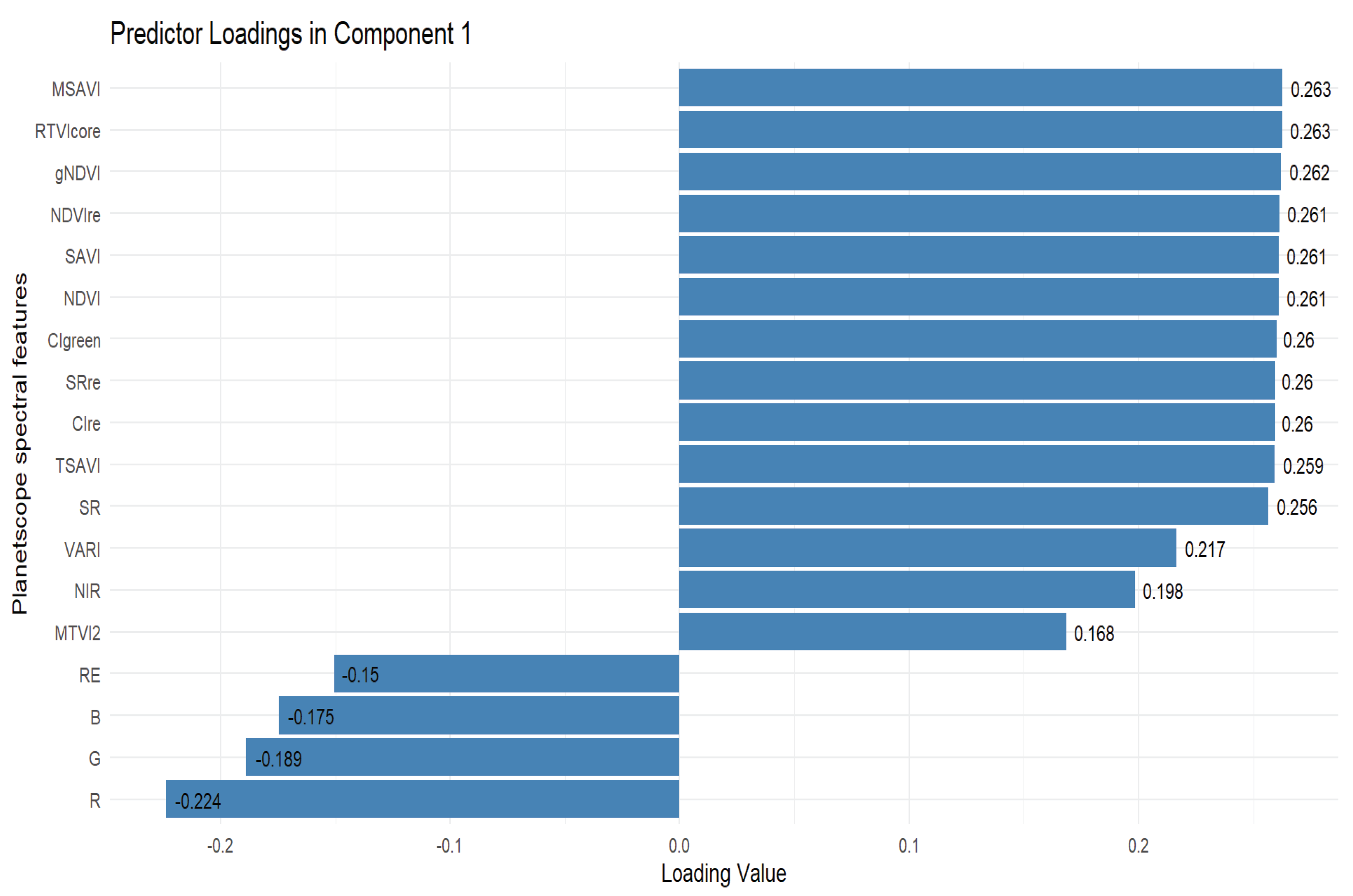

3.4. Selection of Important Variables for Peanut LAI Estimation

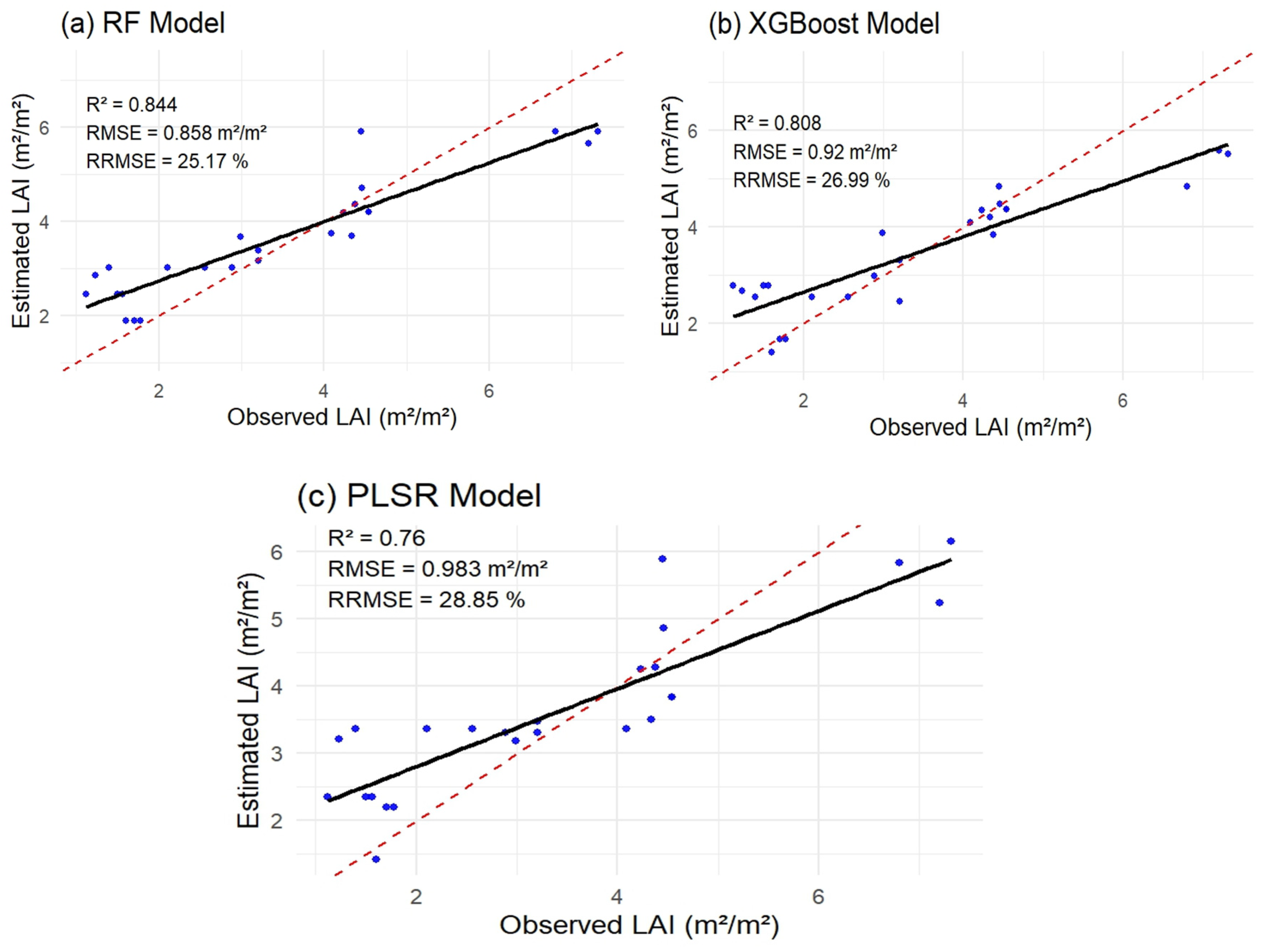

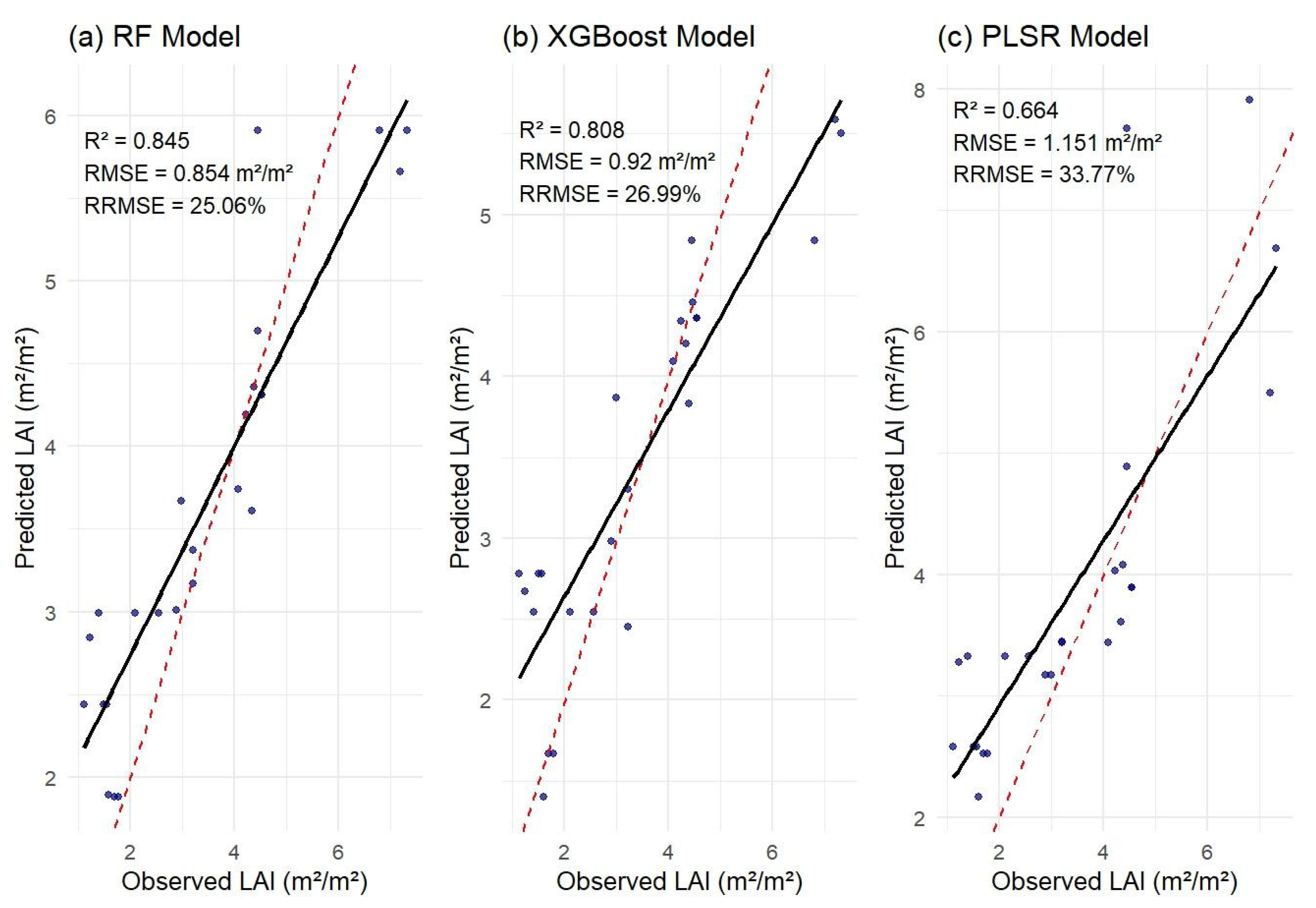

3.5. Estimation of Peanut LAI Based on Machine Learning and Statistical Algorithms Using Important Predictor Variables

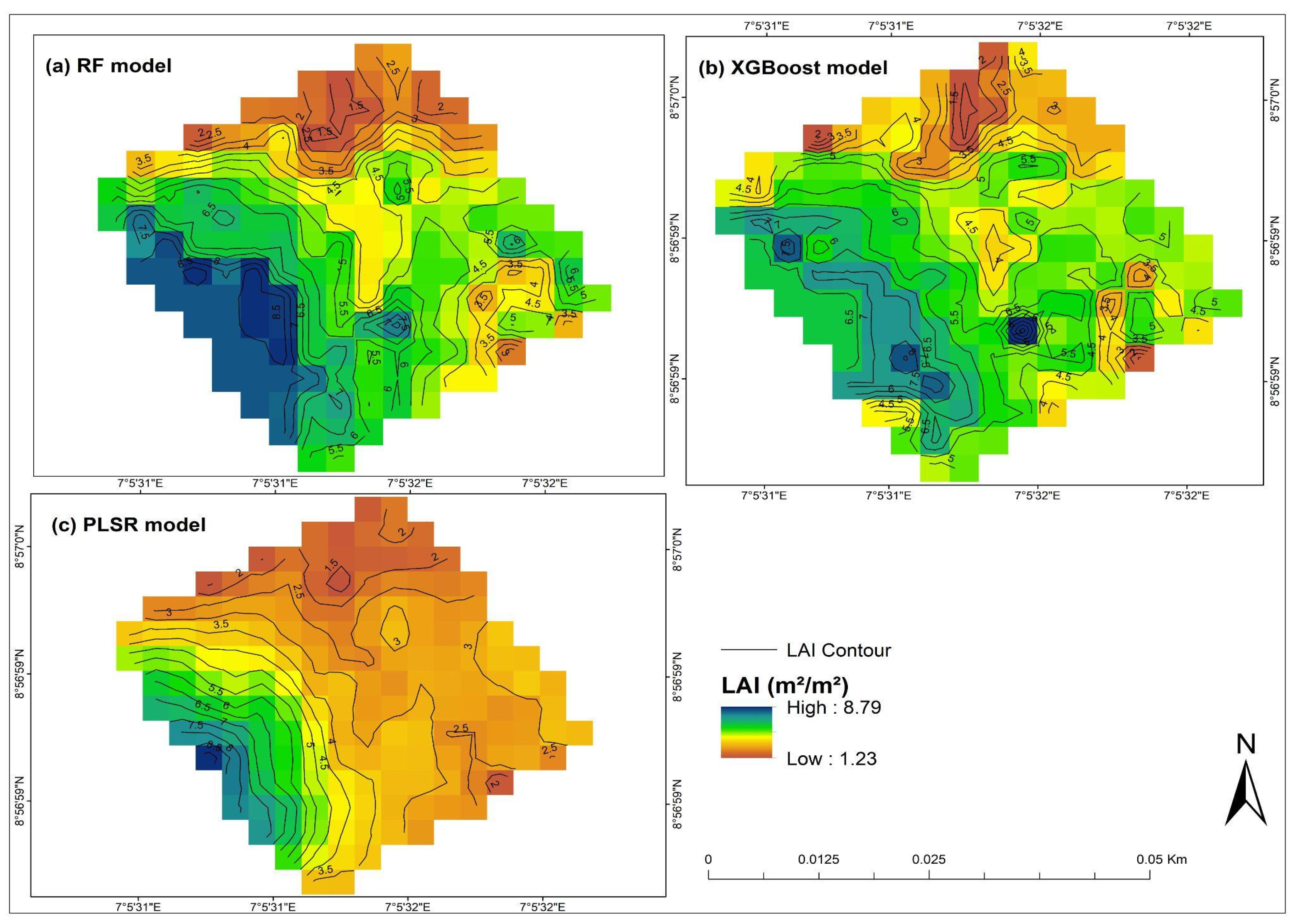

3.6. Generation of Peanut LAI Prediction Maps Based Different Models

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Ethical statement

Declaration of competing interest

References

- Abd El-Ghany, N. M., Abd El-Aziz, S. E., & Marei, S. S. (2020). A review: Application of remote sensing as a promising strategy for insect pests and diseases management. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(27), 33503–33515. [CrossRef]

- Ajeigbe H.A., Waliyar F., Echekwu C.A, Ayuba K., Motagi B.N., Eniayeju D. and Inuwa A. (2015). A Farmer’s Guide to Groundnut Production in Nigeria. Patancheru 502 324, Telangana, India: International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics. 36 pp.

- Ali, A. M., Abouelghar, M., Belal, A. A., Saleh, N., Yones, M., Selim, A. I., Amin, M. E. S., Elwesemy, A., Kucher, D. E., Maginan, S., & Savin, I. (2022). Crop Yield Prediction Using Multi Sensors Remote Sensing (Review Article). The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science, 25(3), 711–716. [CrossRef]

- Amankulova, K., Farmonov, N., Akramova, P., Tursunov, I., & Mucsi, L. (2023). Comparison of PlanetScope, Sentinel-2, and landsat 8 data in soybean yield estimation within-field variability with random forest regression. Heliyon, 9(6), e17432. [CrossRef]

- Anees, S. A., Mehmood, K., Khan, W. R., Sajjad, M., Alahmadi, T. A., Alharbi, S. A., & Luo, M. (2024). Integration of machine learning and remote sensing for above ground biomass estimation through Landsat-9 and field data in temperate forests of the Himalayan region. Ecological Informatics, 82, 102732. [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, H., Homayouni, S., McNairn, H., Hosseini, M., & Mahdianpari, M. (2022). Regional Crop Characterization Using Multi-Temporal Optical and Synthetic Aperture Radar Earth Observations Data. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing, 48(2), 258–277. [CrossRef]

- Barboza, T. O. C., Souza, J. B. C., Ferraz, M. A. J., De Almeida, S. L. H., Pilon, C., Vellidis, G., Da Silva, R. P., & Dos Santos, A. F. (2025). Application of artificial intelligence for identification of peanut maturity using climatic variables and vegetation indices. Precision Agriculture, 26(3), 43. [CrossRef]

- Baret, F., Guyot, G., & Major, D. J. (1989). TSAVI: A Vegetation Index Which Minimizes Soil Brightness Effects On LAI And APAR Estimation. 12th Canadian Symposium on Remote Sensing Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 3, 1355–1358. [CrossRef]

- Beckschäfer, P., Fehrmann, L., Harrison, R., Xu, J., & Kleinn, C. (2014). Mapping Leaf Area Index in subtropical upland ecosystems using RapidEye imagery and the randomForest algorithm. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, 7(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Behera, S. K., Srivastava, P., Pathre, U. V., & Tuli, R. (2010). An indirect method of estimating leaf area index in Jatropha curcas L. using LAI-2000 Plant Canopy Analyzer. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 150(2), 307–311. [CrossRef]

- Belaqziz, S., Khabba, S., Kharrou, M. H., Bouras, E. H., Er-Raki, S., & Chehbouni, A. (2021). Optimizing the Sowing Date to Improve Water Management and Wheat Yield in a Large Irrigation Scheme, through a Remote Sensing and an Evolution Strategy-Based Approach. Remote Sensing, 13(18), 3789. [CrossRef]

- Belgiu, M., & Drăguţ, L. (2016). Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 114, 24–31. [CrossRef]

- Ben Asher, J., Bar Yosef, B., & Volinsky, R. (2013). Ground-based remote sensing system for irrigation scheduling. Biosystems Engineering, 114(4), 444–453. [CrossRef]

- Beven, K. J., & Kirkby, M. J. (1979). A physically based, variable contributing area model of basin hydrology / Un modèle à base physique de zone d’appel variable de l’hydrologie du bassin versant. Hydrological Sciences Bulletin, 24(1), 43–69. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. (2001). Random forests. Machine Learning, 45(1), 5–32. [CrossRef]

- Caballero, G., Pezzola, A., Winschel, C., Casella, A., Sanchez Angonova, P., Orden, L., Berger, K., Verrelst, J., & Delegido, J. (2022). Quantifying Irrigated Winter Wheat LAI in Argentina Using Multiple Sentinel-1 Incidence Angles. Remote Sensing, 14(22), 5867. [CrossRef]

- Caicedo, J. P. R., Verrelst, J., Munoz-Mari, J., Moreno, J., & Camps-Valls, G. (2014). Toward a Semiautomatic Machine Learning Retrieval of Biophysical Parameters. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 7(4), 1249–1259. [CrossRef]

- Campos-Taberner, M., García-Haro, F., Confalonieri, R., Martínez, B., Moreno, Á., Sánchez-Ruiz, S., Gilabert, M., Camacho, F., Boschetti, M., & Busetto, L. (2016). Multitemporal Monitoring of Plant Area Index in the Valencia Rice District with PocketLAI. Remote Sensing, 8(3), 202. [CrossRef]

- Casa, R., Varella, H., Buis, S., Guérif, M., De Solan, B., & Baret, F. (2012). Forcing a wheat crop model with LAI data to access agronomic variables: Evaluation of the impact of model and LAI uncertainties and comparison with an empirical approach. European Journal of Agronomy, 37(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S., Baath, G. S., Sapkota, B. R., Flynn, K. C., & Smith, D. R. (2025). Enhancing LAI estimation using multispectral imagery and machine learning: A comparison between reflectance-based and vegetation indices-based approaches. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 230, 109790. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. M., & Black, T. A. (1992). Defining leaf area index for non--flat leaves. Plant, Cell & Environment, 15(4), 421–429. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., & Guestrin, C. (2016). XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 785–794. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P., Tremblay, N., Wang, J., Vigneaulta, P., (2010). New index for crop canopy fresh biomass estimation. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 30, 512–517 (in Chinese).

- Confalonieri, R., Foi, M., Casa, R., Aquaro, S., Tona, E., Peterle, M., Boldini, A., De Carli, G., Ferrari, A., Finotto, G., Guarneri, T., Manzoni, V., Movedi, E., Nisoli, A., Paleari, L., Radici, I., Suardi, M., Veronesi, D., Bregaglio, S., … Acutis, M. (2013). Development of an app for estimating leaf area index using a smartphone. Trueness and precision determination and comparison with other indirect methods. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 96, 67–74. [CrossRef]

- De Bei, R., Fuentes, S., Gilliham, M., Tyerman, S., Edwards, E., Bianchini, N., Smith, J., & Collins, C. (2016). VitiCanopy: A Free Computer App to Estimate Canopy Vigor and Porosity for Grapevine. Sensors, 16(4), 585. [CrossRef]

- De Magalhães, L. P., & Rossi, F. (2024). Use of Indices in RGB and Random Forest Regression to Measure the Leaf Area Index in Maize. Agronomy, 14(4), 750. [CrossRef]

- Din, M., Zheng, W., Rashid, M., Wang, S., & Shi, Z. (2017). Evaluating Hyperspectral Vegetation Indices for Leaf Area Index Estimation of Oryza sativa L. at Diverse Phenological Stages. Frontiers in Plant Science, 8, 820. [CrossRef]

- Du, L., Yang, H., Song, X., Wei, N., Yu, C., Wang, W., & Zhao, Y. (2022). Estimating leaf area index of maize using UAV-based digital imagery and machine learning methods. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 15937. [CrossRef]

- Dube, T., Mutanga, O., Sibanda, M., Shoko, C., & Chemura, A. (2017). Evaluating the influence of the Red Edge band from RapidEye sensor in quantifying leaf area index for hydrological applications specifically focussing on plant canopy interception. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 100, 73–80. [CrossRef]

- Ekwe, M. C., Adeluyi, O., Verrelst, J., Kross, A., & Odiji, C. A. (2024). Estimating rainfed groundnut’s leaf area index using Sentinel-2 based on Machine Learning Regression Algorithms and Empirical Models. Precision Agriculture. [CrossRef]

- Ennouri, K., Triki, M. A., & Kallel, A. (2020). Applications of Remote Sensing in Pest Monitoring and Crop Management. In C. Keswani (Ed.), Bioeconomy for Sustainable Development (pp. 65–77). Springer Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Fang, H., Baret, F., Plummer, S., & Schaepman--Strub, G. (2019). An Overview of Global Leaf Area Index (LAI): Methods, Products, Validation, and Applications. Reviews of Geophysics, 57(3), 739–799. [CrossRef]

- Farmonov, N., Amankulova, K., Szatmári, J., Urinov, J., Narmanov, Z., Nosirov, J., & Mucsi, L. (2023). Combining PlanetScope and Sentinel-2 images with environmental data for improved wheat yield estimation. International Journal of Digital Earth, 16(1), 847–867. [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S., Hussain, A., Amir, S. B., Ahmed, S. H., & Aslam, S. M. H. (2023). XGBoost and Random Forest Algorithms: An in Depth Analysis. Pakistan Journal of Scientific Research, 3(1), 26–31. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y., Yang, G., Feng, H., Song, X., Xu, X., & Wang, J. (2013). Comparative analysis of three regression methods for the winter wheat biomass estimation using hyperspectral measurements. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computer Science and Electronics Engineering (ICCSEE 2013), China. [CrossRef]

- Francone, C., Pagani, V., Foi, M., Cappelli, G., & Confalonieri, R. (2014). Comparison of leaf area index estimates by ceptometer and PocketLAI smart app in canopies with different structures. Field Crops Research, 155, 38–41. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y., Yang, G., Song, X., Li, Z., Xu, X., Feng, H., & Zhao, C. (2021). Improved Estimation of Winter Wheat Aboveground Biomass Using Multiscale Textures Extracted from UAV-Based Digital Images and Hyperspectral Feature Analysis. Remote Sensing, 13(4), 581. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X., Yao, Y., Chen, S., Li, Q., Zhang, X., Liu, Z., Zeng, Y., Ma, Y., Zhao, Y., & Li, S. (2024). Improved maize leaf area index inversion combining plant height corrected resampling size and random forest model using UAV images at fine scale. European Journal of Agronomy, 161, 127360. [CrossRef]

- Garg, A., & Tai, K. (2013). Comparison of statistical and machine learning methods in modelling of data with multicollinearity. International Journal of Modelling, Identification and Control, 18(4), 295. [CrossRef]

- Geladi, P., & Kowalski, B. R. (1986). Partial least-squares regression: A tutorial. Analytica Chimica Acta, 185, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Geng, L., Che, T., Ma, M., Tan, J., & Wang, H. (2021). Corn Biomass Estimation by Integrating Remote Sensing and Long-Term Observation Data Based on Machine Learning Techniques. Remote Sensing, 13(12), 2352. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. S., Dey, S., Bhogapurapu, N., Homayouni, S., Bhattacharya, A., & McNairn, H. (2022). Gaussian Process Regression Model for Crop Biophysical Parameter Retrieval from Multi-Polarized C-Band SAR Data. Remote Sensing, 14(4), 934. [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A. A., Kaufman, Y. J., & Merzlyak, M. N. (1996). Use of a green channel in remote sensing of global vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sensing of Environment, 58(3), 289–298. [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A., & Merzlyak, M. N. (1994). Spectral Reflectance Changes Associated with Autumn Senescence of Aesculus hippocastanum L. and Acer platanoides L. Leaves. Spectral Features and Relation to Chlorophyll Estimation. Journal of Plant Physiology, 143(3), 286–292. [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A. A., Kaufman, Y. J., Stark, R., & Rundquist, D. (2002). Novel algorithms for remote estimation of vegetation fraction. Remote Sensing of Environment, 80(1), 76–87. [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A. A., Gritz †, Y., & Merzlyak, M. N. (2003). Relationships between leaf chlorophyll content and spectral reflectance and algorithms for non-destructive chlorophyll assessment in higher plant leaves. Journal of Plant Physiology, 160(3), 271–282. [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A. A., Viña, A., Ciganda, V., Rundquist, D. C., & Arkebauer, T. J. (2005). Remote estimation of canopy chlorophyll content in crops. Geophysical Research Letters, 32(8), 2005GL022688. [CrossRef]

- Gleason, C. J., & Im, J. (2012). Forest biomass estimation from airborne LiDAR data using machine learning approaches. Remote Sensing of Environment, 125, 80–91. [CrossRef]

- Haboudane, D. (2004). Hyperspectral vegetation indices and novel algorithms for predicting green LAI of crop canopies: Modeling and validation in the context of precision agriculture. Remote Sensing of Environment, 90(3), 337–352. [CrossRef]

- Haboudane, D., Miller, J., Pattey, E., Zarco-Tejada, P., & Strachan, I. (2004). Hyperspectral vegetation indices and novel algorithms for predicting green LAI of crop canopies: Modeling and validation in the context of precision agriculture. REMOTE SENSING OF ENVIRONMENT, 90(3), 337–352. [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. (2005). The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference and Prediction. Math. Intell., 27, 83–85.

- Huang, Y., Reddy, K. N., Fletcher, R. S., & Pennington, D. (2018). UAV Low-Altitude Remote Sensing for Precision Weed Management. Weed Technology, 32(1), 2–6. [CrossRef]

- Huete, A. R. (1988). A soil-adjusted vegetation index (SAVI). Remote Sensing of Environment, 25(3), 295–309. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S., Teshome, F. T., Tulu, B. B., Awoke, G. W., Hailegnaw, N. S., & Bayabil, H. K. (2025). Leaf area index (LAI) prediction using machine learning and UAV based vegetation indices. European Journal of Agronomy, 168, 127557. [CrossRef]

- Ilniyaz, O., Kurban, A., & Du, Q. (2022). Leaf Area Index Estimation of Pergola-Trained Vineyards in Arid Regions Based on UAV RGB and Multispectral Data Using Machine Learning Methods. Remote Sensing, 14(2), 415. [CrossRef]

- Intarat, K., Netsawang, P., Narawatthana, S., Promaoh, C., & Chuenkamol, S. (2025). Integrating spectral and texture indices with machine learning for rice leaf area index (lai) estimation in Suphan Buri, Thailand. Geographia Technica, 20(1/2025), 207–227. [CrossRef]

- Jonckheere, I., Fleck, S., Nackaerts, K., Muys, B., Coppin, P., Weiss, M., & Baret, F. (2004). Review of methods for in situ leaf area index determination. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 121(1–2), 19–35. [CrossRef]

- Jonckheere, I., Muys, B., & Coppin, P. (2005). Allometry and evaluation of in situ optical LAI determination in Scots pine: A case study in Belgium. Tree Physiology, 25(6), 723–732. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C. F. (1969). Derivation of Leaf-Area Index from Quality of Light on the Forest Floor. Ecology, 50(4), 663–666. [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M., Phinn, S., & Johansen, K. (2016). Assessment of multi-resolution image data for mangrove leaf area index mapping. Remote Sensing of Environment, 176, 242–254. [CrossRef]

- Kaveh, N., Ebrahimi, A., & Asadi, E. (2023). Comparative analysis of random forest, exploratory regression, and structural equation modeling for screening key environmental variables in evaluating rangeland above-ground biomass. Ecological Informatics, 77, 102251. [CrossRef]

- Kganyago, M., Mhangara, P., & Adjorlolo, C. (2021). Estimating Crop Biophysical Parameters Using Machine Learning Algorithms and Sentinel-2 Imagery. Remote Sensing, 13(21), 4314. [CrossRef]

- Kiala, Z., Odindi, J., Mutanga, O., & Peerbhay, K. (2016). Comparison of partial least squares and support vector regressions for predicting leaf area index on a tropical grassland using hyperspectral data. Journal of Applied Remote Sensing, 10(3), 036015. [CrossRef]

- Kpienbaareh, D., Mohammed, K., Luginaah, I., Wang, J., Bezner Kerr, R., Lupafya, E., & Dakishoni, L. (2022). Estimating Groundnut Yield in Smallholder Agriculture Systems Using PlanetScope Data. Land, 11(10), 1752. [CrossRef]

- Kross, A., McNairn, H., Lapen, D., Sunohara, M., & Champagne, C. (2015). Assessment of RapidEye vegetation indices for estimation of leaf area index and biomass in corn and soybean crops. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 34, 235–248. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Zhang, Y., Bao, Y., Luo, J., Jin, X., Xu, X., Song, X., & Yang, G. (2014). Exploring the Best Hyperspectral Features for LAI Estimation Using Partial Least Squares Regression. Remote Sensing, 6(7), 6221–6241. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Xin, X., Tang, H., Yang, F., Chen, B., & Zhang, B. (2017). Estimating grassland LAI using the Random Forests approach and Landsat imagery in the meadow steppe of Hulunber, China. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 16(2), 286–297. [CrossRef]

- Li, F., Miao, Y., Chen, X., Sun, Z., Stueve, K., & Yuan, F. (2022). In-Season Prediction of Corn Grain Yield through PlanetScope and Sentinel-2 Images. Agronomy, 12(12), 3176. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Zeng, H., Zhang, M., Wu, B., Zhao, Y., Yao, X., Cheng, T., Qin, X., & Wu, F. (2023). A county-level soybean yield prediction framework coupled with XGBoost and multidimensional feature engineering. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 118, 103269. [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Yuan, F., Ata-UI-Karim, S. T., Zheng, H., Cheng, T., Liu, X., Tian, Y., Zhu, Y., Cao, W., & Cao, Q. (2019). Combining Color Indices and Textures of UAV-Based Digital Imagery for Rice LAI Estimation. Remote Sensing, 11(15), 1763. [CrossRef]

- Liang, L., Di, L., Zhang, L., Deng, M., Qin, Z., Zhao, S., & Lin, H. (2015). Estimation of crop LAI using hyperspectral vegetation indices and a hybrid inversion method. Remote Sensing of Environment, 165, 123–134. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Zeng, W., Wu, L., Lei, G., Chen, H., Gaiser, T., & Srivastava, A. K. (2021). Simulating the Leaf Area Index of Rice from Multispectral Images. Remote Sensing, 13(18), 3663. [CrossRef]

- Ma, M., Zhao, G., He, B., Li, Q., Dong, H., Wang, S., & Wang, Z. (2021). XGBoost-based method for flash flood risk assessment. Journal of Hydrology, 598, 126382. [CrossRef]

- Maimaitijiang, M., Sagan, V., Sidike, P., Daloye, A. M., Erkbol, H., & Fritschi, F. B. (2020). Crop Monitoring Using Satellite/UAV Data Fusion and Machine Learning. Remote Sensing, 12(9), 1357. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, M., & Thenkabail, P. (2015). Advantage of hyperspectral EO-1 Hyperion over multispectral IKONOS, GeoEye-1, WorldView-2, Landsat ETM+, and MODIS vegetation indices in crop biomass estimation. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 108, 205–218. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Muñoz, G., & Suárez, A. (2010). Out-of-bag estimation of the optimal sample size in bagging. Pattern Recognition, 43(1), 143–152. [CrossRef]

- Myneni, R. B., Hoffman, S., Knyazikhin, Y., Privette, J. L., Glassy, J., Tian, Y., Wang, Y., Song, X., Zhang, Y., Smith, G. R., Lotsch, A., Friedl, M., Morisette, J. T., Votava, P., Nemani, R. R., & Running, S. W. (2002). Global products of vegetation leaf area and fraction absorbed PAR from year one of MODIS data. Remote Sensing of Environment, 83(1–2), 214–231. [CrossRef]

- Nguy-Robertson, A., Gitelson, A., Peng, Y., Viña, A., Arkebauer, T., & Rundquist, D. (2012). Green Leaf Area Index Estimation in Maize and Soybean: Combining Vegetation Indices to Achieve Maximal Sensitivity. Agronomy Journal, 104(5), 1336–1347. [CrossRef]

- Haboudane, D. (2004). Hyperspectral vegetation indices and novel algorithms for predicting green LAI of crop canopies: Modeling and validation in the context of precision agriculture. Remote Sensing of Environment, 90(3), 337–352. [CrossRef]

- Orlando, F., Movedi, E., Coduto, D., Parisi, S., Brancadoro, L., Pagani, V., Guarneri, T., & Confalonieri, R. (2016). Estimating Leaf Area Index (LAI) in Vineyards Using the PocketLAI Smart-App. Sensors, 16(12), 2004. [CrossRef]

- Orlando, F., Movedi, E., Coduto, D., Parisi, S., Brancadoro, L., Pagani, V., Guarneri, T., & Confalonieri, R. (2016). Estimating Leaf Area Index (LAI) in Vineyards Using the PocketLAI Smart-App. Sensors, 16(12), 2004. [CrossRef]

- Orisakwe, I. C., Nwofor, O. K., Njoku, C. C., & Ezedigboh, U. O. (2017). On the analysis of the changes in the temperatures over Abuja, Nigeria. Journal of Physical Sciences and Environmental Studies, 3(1), 8–17.

- Pagliai, A., Ammoniaci, M., Sarri, D., Lisci, R., Perria, R., Vieri, M., D’Arcangelo, M. E. M., Storchi, P., & Kartsiotis, S.-P. (2022). Comparison of Aerial and Ground 3D Point Clouds for Canopy Size Assessment in Precision Viticulture. Remote Sensing, 14(5), 1145. [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, N., & Das, B. S. (2021). Evaluation of regression algorithms for estimating leaf area index and canopy water content from water stressed rice canopy reflectance. Information Processing in Agriculture, 8(2), 284–298. [CrossRef]

- Pichon, L., Taylor, J., & Tisseyre, B. (2020). Using smartphone leaf area index data acquired in a collaborative context within vineyards in southern France. OENO One, 54(1), 123–130. [CrossRef]

- Planet Team (2025). “Planet Surface Reflectance Product v2.” Planet Labs, Inc, Accessed 18.04.2025. https://assets.planet.com/marketing/PDF/Planet_Surface_Reflectance_Technical_White_Paper.pdf.

- Qi, J., Chehbouni, A., Huete, A. R., Kerr, Y. H., & Sorooshian, S. (1994). A modified soil adjusted vegetation index. Remote Sensing of Environment, 48(2), 119–126. [CrossRef]

- Radočaj, D., Jurišić, M., & Gašparović, M. (2022). The Role of Remote Sensing Data and Methods in a Modern Approach to Fertilization in Precision Agriculture. Remote Sensing, 14(3), 778. [CrossRef]

- Reisi Gahrouei, O., McNairn, H., Hosseini, M., & Homayouni, S. (2020). Estimation of Crop Biomass and Leaf Area Index from Multitemporal and Multispectral Imagery Using Machine Learning Approaches. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing, 46(1), 84–99. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Caicedo, J. P., Verrelst, J., Muñoz-Marí, J., Camps-Valls, G., & Moreno, J. (2017). Hyperspectral dimensionality reduction for biophysical variable statistical retrieval. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 132, 88–101. [CrossRef]

- Roslim, M. H. M., Juraimi, A. S., Che’Ya, N. N., Sulaiman, N., Manaf, M. N. H. A., Ramli, Z., & Motmainna, Mst. (2021). Using Remote Sensing and an Unmanned Aerial System for Weed Management in Agricultural Crops: A Review. Agronomy, 11(9), 1809. [CrossRef]

- Rouault, P., Courault, D., Pouget, G., Flamain, F., Diop, P.-K., Desfonds, V., Doussan, C., Chanzy, A., Debolini, M., McCabe, M., & Lopez-Lozano, R. (2024). Phenological and Biophysical Mediterranean Orchard Assessment Using Ground-Based Methods and Sentinel 2 Data. Remote Sensing, 16(18), 3393. [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J. W., Haas, R. H., Schell, J. A., & Deering, D. W. (1973). Monitoring vegetation systems in the great plains with ERTS.

- Serrano Reyes, J., Jiménez, J. U., Quirós-McIntire, E. I., Sanchez-Galan, J. E., & Fábrega, J. R. (2023). Comparing Two Methods of Leaf Area Index Estimation for Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Using In-Field Spectroradiometric Measurements and Multispectral Satellite Images. AgriEngineering, 5(2), 965–981. [CrossRef]

- Shao, G., Han, W., Zhang, H., Liu, S., Wang, Y., Zhang, L., & Cui, X. (2021). Mapping maize crop coefficient Kc using random forest algorithm based on leaf area index and UAV-based multispectral vegetation indices. Agricultural Water Management, 252, 106906. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S., Cazenave, A.B., Oakes, J., McCall, D., Thomason, W., Abbott, L., & Balota, M. (2021). Aerial high-throughput phenotyping of peanut leaf area index and lateral growth. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 21661. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y., Yan, Z., Yang, Y., Tang, W., Sun, J., & Zhang, Y. (2024). Application of UAV-Borne Visible-Infared Pushbroom Imaging Hyperspectral for Rice Yield Estimation Using Feature Selection Regression Methods. Sustainability, 16(2), 632. [CrossRef]

- Souza, J. B. C., De Almeida, S. L. H., Freire De Oliveira, M., Santos, A. F. D., Filho, A. L. D. B., Meneses, M. D., & Silva, R. P. D. (2022). Integrating Satellite and UAV Data to Predict Peanut Maturity upon Artificial Neural Networks. Agronomy, 12(7), 1512. [CrossRef]

- Srinet, R., Nandy, S., & Patel, N. R. (2019). Estimating leaf area index and light extinction coefficient using Random Forest regression algorithm in a tropical moist deciduous forest, India. Ecological Informatics, 52, 94–102. [CrossRef]

- Stroppiana, D., Boschetti, M., Confalonieri, R., Bocchi, S., & Brivio, P. A. (2006). Evaluation of LAI-2000 for leaf area index monitoring in paddy rice. Field Crops Research, 99(2–3), 167–170. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q., Jiao, Q., Qian, X., Liu, L., Liu, X., & Dai, H. (2021). Improving the Retrieval of Crop Canopy Chlorophyll Content Using Vegetation Index Combinations. Remote Sensing, 13(3), 470. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Qin, Q., Ren, H., Zhang, T., & Chen, S. (2020). Red-Edge Band Vegetation Indices for Leaf Area Index Estimation From Sentinel-2/MSI Imagery. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 58(2), 826–840. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z., Guo, J., Xiang, Y., Lu, X., Wang, Q., Wang, H., Cheng, M., Wang, H., Wang, X., An, J., Abdelghany, A., Li, Z., & Zhang, F. (2022). Estimation of Leaf Area Index and Above-Ground Biomass of Winter Wheat Based on Optimal Spectral Index. Agronomy, 12(7), 1729. [CrossRef]

- Tao, H., Feng, H., Xu, L., Miao, M., Long, H., Yue, J., Li, Z., Yang, G., Yang, X., & Fan, L. (2020). Estimation of Crop Growth Parameters Using UAV-Based Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Data. Sensors, 20(5), 1296. [CrossRef]

- Torlay, L., Perrone-Bertolotti, M., Thomas, E., & Baciu, M. (2017). Machine learning–XGBoost analysis of language networks to classify patients with epilepsy. Brain Informatics, 4(3), 159–169. [CrossRef]

- Tunca, E., Köksal, E. S., Öztürk, E., Akay, H., & Taner, S. Ç. (2024). Accurate leaf area index estimation in sorghum using high-resolution UAV data and machine learning models. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 133, 103537. [CrossRef]

- Varela, S., Pederson, T., Bernacchi, C. J., & Leakey, A. D. B. (2021). Understanding Growth Dynamics and Yield Prediction of Sorghum Using High Temporal Resolution UAV Imagery Time Series and Machine Learning. Remote Sensing, 13(9), 1763. [CrossRef]

- Verrelst, J., Camps-Valls, G., Muñoz-Marí, J., Rivera, J. P., Veroustraete, F., Clevers, J. G. P. W., & Moreno, J. (2015). Optical remote sensing and the retrieval of terrestrial vegetation biogeophysical properties – A review. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 108, 273–290. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A. X., Tran, C., Desai, N., Lobell, D., & Ermon, S. (2018a). Deep Transfer Learning for Crop Yield Prediction with Remote Sensing Data. Proceedings of the 1st ACM SIGCAS Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Chang, Q., Yang, J., Zhang, X., & Li, F. (2018b). Estimation of paddy rice leaf area index using machine learning methods based on hyperspectral data from multi-year experiments. PLOS ONE, 13(12), e0207624. [CrossRef]

- Wold, S., Sjöström, M., & Eriksson, L. (2001). PLS-regression: A basic tool of chemometrics. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 58(2), 109–130. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z., Liang, S., Wang, J., Jiang, B., & Li, X. (2011). Real-time retrieval of Leaf Area Index from MODIS time series data. Remote Sensing of Environment, 115(1), 97–106. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q., Huang, W., Liang, D., Chen, P., Wu, C., Yang, G., Zhang, J., Huang, L., & Zhang, D. (2014). Leaf Area Index Estimation Using Vegetation Indices Derived From Airborne Hyperspectral Images in Winter Wheat. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 7(8), 3586–3594. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M., Xu, X., Li, Z., Meng, Y., Yang, X., Song, X., Yang, G., Xu, S., Zhu, Q., & Xue, H. (2022). Remote Sensing Prescription for Rice Nitrogen Fertilizer Recommendation Based on Improved NFOA Model. Agronomy, 12(8), 1804. [CrossRef]

- Yu, T., Zhou, J., Fan, J., Wang, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2023). Potato Leaf Area Index Estimation Using Multi-Sensor Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Imagery and Machine Learning. Remote Sensing, 15(16), 4108. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W., Cheng, Q., Duan, F., Huang, X., & Chen, Z. (2025). Remote sensing-based analysis of yield and water-fertilizer use efficiency in winter wheat management. Agricultural Water Management, 311, 109390. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Huang, Y., Pu, R., Gonzalez-Moreno, P., Yuan, L., Wu, K., & Huang, W. (2019). Monitoring plant diseases and pests through remote sensing technology: A review. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 165, 104943. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Cheng, T., Guo, W., Xu, X., Qiao, H., Xie, Y., & Ma, X. (2021). Leaf area index estimation model for UAV image hyperspectral data based on wavelength variable selection and machine learning methods. Plant Methods, 17(1), 49. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Yang, Y., Zhang, Q., Duan, R., Liu, J., Qin, Y., & Wang, X. (2022). Toward Multi-Stage Phenotyping of Soybean with Multimodal UAV Sensor Data: A Comparison of Machine Learning Approaches for Leaf Area Index Estimation. Remote Sensing, 15(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Li, Z., Pu, Y., Zhang, Y., Tang, Z., Fu, J., Xu, W., Xiang, Y., & Zhang, F. (2023). Estimation of the Leaf Area Index of Winter Rapeseed Based on Hyperspectral and Machine Learning. Sustainability, 15(17), 12930. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Liu, K., Liu, L., Myint, S., Wang, S., Liu, H., & He, Z. (2017). Exploring the Potential of WorldView-2 Red-Edge Band-Based Vegetation Indices for Estimation of Mangrove Leaf Area Index with Machine Learning Algorithms. Remote Sensing, 9(10), 1060. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T. (2020). Analysis on the Applicability of the Random Forest. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1607(1), 012123. [CrossRef]

| Data | Predictor variables | Description | Equation | References |

| PlanetScope multispectral surface reflectance | B | Blue (465 – 515 nm) | / | |

| G | Green (547 – 583 nm) | / | ||

| R | Red (650 – 680 nm) | / | ||

| RE | RedEdge (697 – 713 nm) | / | ||

| NIR | Near-infrared (845 – 885 nm) | / | ||

| PlanetScope vegetation indices | NDVI | Normalized difference vegetation index | Rouse et al. (1974) | |

| gNDVI | Green normalized difference vegetation index | Gitelson et al., (1996) | ||

| MSAVI | Modified Soil-adjusted vegetation index | (2 * RNIR + 1 – sqrt ((2 * RNIR + 1)2 –8 * (RNIR – RRED))) / 2 | Qi et al., (1994) | |

| SAVI | Soil-adjusted vegetation index | (RNIR – RRed)(1 + L)/(RNIR + RRed + L), where L = 0.5 represents soil adjustment factor. | Huete (1988) | |

| SR | Simple ratio | Jordan (1969) | ||

| SRRedEdge | Red edge simple ratio | Gitelson & Merzlyak (1994) | ||

| RTVIcore | Red edge triangular vegetation index (core only) | Chen et al., (2010) | ||

| CIGreen | Chlorophyll index-green | Gitelson et al., (2003) | ||

| TSAVI | Transformed soil-adjusted vegetation index | a(RNIR – aRRED – b)/(RRED+aRNIR – a*b), where a = 0.33 and b = 0.5 are slope and intercept of a solid line, respectively, with an adjustment factor of 1.5 | Baret et al., (1989) |

|

| MTVI2 | Modified triangular vegetation index | Haboudane et al., (2004) | ||

| CIRedEdge | Red edge chlorophyll index | Gitelson et al., (2005) | ||

| NDVIRedEdge | Red edge normalized difference vegetation index | Gitelson & Merzlyak (1994) | ||

| VARI | Visible atmospherically resistant index |

|

Gitelson et al., (2002) |

| Algorithm | Advantages | Limitations | References |

| Random Forest (RF) | Can provide interpretability and findings by analyzing both the main and alternative features within the decision trees. | It can be computationally demanding and slower in terms of processing speed, and offers lower interpretability compared to simpler regression models | Caicedo et al. (2014); Belgiu & Drăguţ (2016); (Zhu, 2020). |

| Suitable for processing high-dimensional data and data with missing variables. | |||

| Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) | Unaffected by highly correlated features, reduces the feature multicollinearity issues, and mitigates overfitting problems. | When data samples are large enough, the greedy method adopted by XGBoost can be time-consuming, and multi-threaded optimization is not required in all cases. | Chen & Guestrin, (2016); Torlay et al. (2017); Ma et al. (2021); Li et al. (2023); Fatima et al. (2023) |

| Capability to handle sparse data, and nonlinearity integrating decision trees with boosting approaches. | |||

| Can overcome the limitations of computational speed and accuracy, requiring less training and prediction time. | |||

| Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) | Efficiency in reducing dimensionality and ability to handle correlated features | Limited interpretability of model coefficients | Geladi & Kowalski (1986) |

| Input Variables | Algorithm | Number of Predictors | R2 | RRMSE (%) | RMSE (m2/m2) |

| RF | 3 | 0.706 | 34.42 | 1.173 | |

| Top 3 spectral bands based on feature importance | XGBoost | 3 | 0.733 | 28.40 | 0.968 |

| PLSR | 3 | 0.657 | 33.71 | 1.149 | |

| RF | 5 | 0.793 | 30.27 | 1.032 | |

| All spectral bands | XGBoost | 5 | 0.771 | 27.59 | 0.941 |

| PLSR | 5 | 0.664 | 33.43 | 1.139 | |

| RF | 6 | 0.844 | 25.17 | 0.858 | |

| Top 6 VIs based on feature importance | XGBoost | 6 | 0.808 | 26.99 | 0.92 |

| PLSR | 6 | 0.76 | 28.85 | 0.983 | |

| RF | 13 | 0.791 | 27.22 | 0.928 | |

| All Spectral Features (Bands + VIs) | XGBoost | 13 | 0.786 | 27.14 | 0.925 |

| PLSR | 13 | 0.686 | 32.36 | 1.103 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).