What is clear is that people could not begin intentionally domesticating animals until they had procured them through entirely unintentional means. (Lawson and Fuller 2014: 127)

… the term “management,” … can be defined as: the manipulation of the conditions of growth of an organism, or the environment that sustains it, in order to increase its relative abundance and predictability and to reduce the time and energy required to harvest it. (Zeder 2015: 3192)

1. Introduction

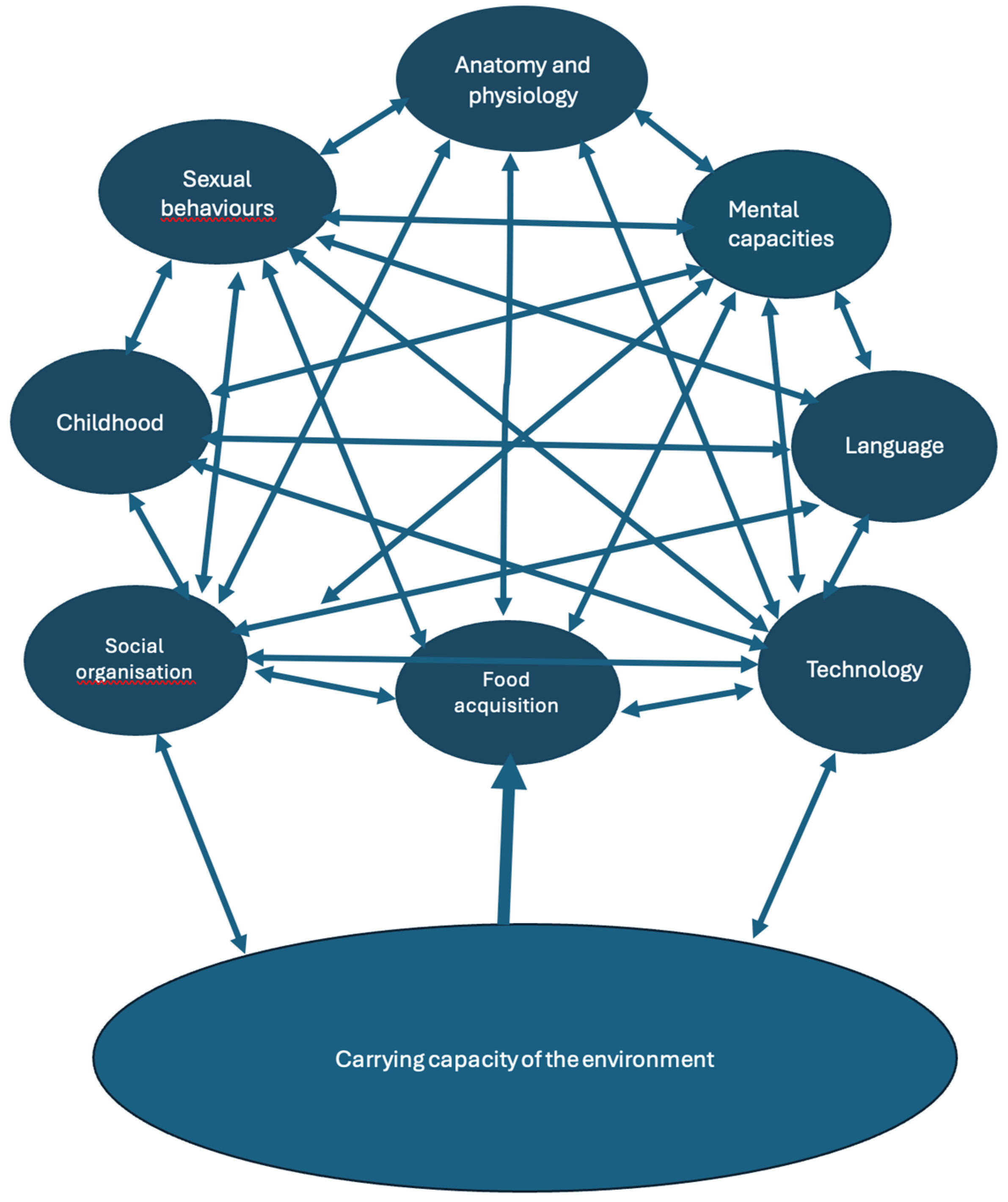

Hominins, from the outset of their existence in the Pliocene, exhibited behaviours aimed at managing their environments (Olney et al. 2015) more than other species did. Initially, these included the use of objects (stones, sticks, straws…) to procure food, to construct shelters by rearranging vegetation and rocks, and to satisfy emotional needs (e.g. early music in Lomekwi [Clark et al. 2024]). These behaviours did not differ much from great ape behaviours. Hominins, as early as the times of Ardipithecus ramidus, displayed adaptations to cooperative parenting and alloparenting (Clark and Henneberg 2017). With the advent of exploiting sources of animal protein and extrasomatic production of energy by fire in the Early Pleistocene (Beaumont 2011), such management probably started changing the effects of the basic ecological rule of survival, C * E > S, [C – carrying capacity of the environment, E- extractive efficiency of individuals or groups, S – sum of needs] (Henneberg and Ostoja-Zagorski 1984; Henneberg and Wolanski 2009) by expanding the extractive efficiency (E) through the use of improved technologies and complex multi-person organization of food acquisition, food transformation (cooking, smoking, drying, fermentation) and food sharing (Wrangham 2009). At the same time, the carrying capacity of the environment (C) was altered by the construction of shelters, the use of body coverings (“clothing”) and fire for warmth, limiting the passive radiation of energy from bodies. Thus, the energy balance changed. The quantity of energy hominins could use was increased by both their better extraction from the environment (E) and re-shaping of the environment (C). This surplus energy allowed an increase in population size and in the size of individual bodies. The increase in population size created demographic pressure for expansion into new environments, necessitating further modifications to environmental management methods. The system of autocatalytic feedback loops driving hominin evolution (Henneberg and Eckhardt 2021; Henneberg 2025), into which greater energy input was introduced, could have enabled evolutionary changes in human social organization, improved technology, extended childhood, reproductive behaviours, mental capacities and the structure and function of human bodies in response to changing energy balance.

Foraging human populations do not have decisive control over the carrying capacity of their environments. They extract food from the natural environment by using the extractive efficiency of their technologies and social organisation. Human control over the carrying capacity of their environment necessitates intervention in its structure and natural processes. It is difficult to point out exactly when such interventions started at a scale large enough to qualitatively alter the acquisition of energy to the extent that would alter the set of autocatalytic feedback loops influencing hominin evolution (

Figure 1). However, the improvement of many elements of the human system during the Palaeolithic indicates that humans must have started gradually improving the management of their environment very early in their history as a genus. It is obvious that food production, evidenced by archaeological finds of categorically new qualities of “agriculture” and “animal husbandry” dating to the early Holocene, significantly changed technology, social organisation and human anatomy (e.g. intensifying gracilization and reduction in cranial capacity initiated in the Late Pleistocene; Henneberg 1988). This change was so profound that it provided humans with surplus energy, time and means to produce abundant figurative art and, ultimately, written records and science.

The underlying force of these changes was human management of plants and animals through altering their reproductive cycles — the process of domestication. Generally, the domestication of animals, plants and fungi consists of the collective genetic alteration of their physiology, behaviour (where applicable), appearance or life cycle through selective breeding. However, its most effective expressions derive from the introduction of the domestication syndrome (Harlan et al. 1973; Hammer 1984; Brown et al. 2008; Bednarik 2008; Wilkins et al. 2014, 2021; cf. ‘domesticated phenotype’, Price 1984, 2002). This syndrome is activated when a pleiotropic reaction to a sustained selection of specific phenotypic traits consequently introduces changes to the domesticated that seem unrelated to the domesticator’s intent. For instance, selection for a reduction in flight response (‘tameness’ or docility) might cause incidental shortening of the face, floppy ears, relative brain-size reduction or change of coat colour, among other changes. Artificial intentional selection by domesticators tends to involve only a single character or a few characteristics, but may be expressed in more numerous pleiotropic consequences that seem unconnected to the selection criterion. This may be due to the linkage of genes or other mechanisms of pleiotropic action of genes (e.g. epistatic effects). Additionally, the neural crest hypothesis proposes that pleiotropic genes affecting neural crest cell development are responsible for the domestication syndrome (Wilkins et al. 2014, 2021; cf. Johnsson et al. 2021), at least in mammals.

Bearing in mind that domestication processes are almost innumerable in nature, it is not surprising that they involve many complexities. Thousands exist in the natural world, laying to rest the view that humans are the only domesticators, shared even by Darwin. Another complicating factor is that symbiotic relationships often accompany domestication: wheat would not have become one of the world's most common plant species had it not been domesticated. Dogs and humans exchanged mutual benefits of protection, feeding, hunting assistance and companionship. Also, the domestication process comprises two phases: an initial state of increased habituation followed by a much longer ‘breed formation’ stage (Wilkins et al. 2021). Humanly initiated domestications began at different times, and for different purposes, starting with the Final Pleistocene and up to recent times, which means that each of them must be at a unique stage of development at present. To add further to the diversity, these stages can be assumed to unfold at different rates in each species. Is the domestication of the reindeer, with its relatively minimal human control over the animal, a practice introduced relatively recently? Or is the rate of development a function of species- or environment-specific conditions? In each domestication history's progress, these and other factors need to be fully engaged to determine the significance of the current state. The only factor that effectively links domestication events is the domestication syndrome, first considered in plants (Hammer 1984) and best explored in vertebrates, particularly mammals. Somatic changes include those in cranial and facial morphology (such as shortening of the snout), reductions of tooth size (notably the canines), reductions in brain volume and in specific brain regions, shortening of the spine, shape changes to body parts (e.g. ear and tail forms) and depigmentation (coat colour changes). Non-somatic effects of the domestication syndrome include more frequent and non-seasonal oestrus cycles that can range to their complete elimination, changed concentrations of several neurotransmitters, alterations in adrenocorticotropic hormone levels, increased docility, prolongation of juvenile behaviour and various other neotenous effects.

In humanly initiated domestication, consistent long-term selection probably only occurred for one of these features: increased docility. This implies that the uniformity of the remaining characteristics derives from the pleiotropy inherent in the domestication syndrome. These other traits are not advantageous to domestication, so they would not have been selected deliberately. They are a random collection, rendered even more diffuse by the idiosyncratic trajectory of each domestication process and by its present-day status. Yet the traits affected are consistent across the domestication of numerous species. It does, however, raise a big question. Just as the change in one characteristic in domestication causes the alteration of several unrelated others by the agency of pleiotropy, general evolution also selects in favour of specific traits. Have such pleiotropic consequences been detected in evolution? This observation raises the possibility that evolution is a considerably more complex process than thought.

Domestication by humans resulted in a reduction in brain size in nearly all domesticated mammalian species. The progenitor species with the largest brain volume experienced the maximal degree of folding (Kruska 1988; Plogmann and Kruska 1990; Trut 1999; Zeder 2012). The reduction has been determined to range from 6% to 40% in mammals. However, each conversion process has been operational for a different duration and mutation rate and would have been subjected to unique circumstances. Where the selection was for greater meat production, it involved considerable body augmentation (Henriksen et al. 2016), affecting the brain/body size ratio (encephalisation). Domestication-derived brain atrophy seems not limited to mammals; it has also been reported in birds and the rainbow trout (Marchetti and Nevitt 2003). The domestication traits seem irreversible because when domesticates revert to a wild state (becoming feral), they retain their smaller brains and other modified traits (Birks and Kitchener 1999; Zeder 2012). For instance, when the Australian dog, the dingo, was imported by human mariners in mid-Holocene times, it must have been in domestic form. Since then, it became feral without relinquishing its domestication characteristics (Schultz 1969; Boitani and Ciucci 1995; Smith et al. 2018).

There is scattered evidence of pre-Holocene human intervention in nature. Aboriginal Australians use of fire to restructure vegetation and fauna is but one example that may extend back into the Pleistocene. The development of human commensal relations with canids is another one. Human symbiotic relations with wolves started in the Pleistocene; whether it was at just 15 ka or at 100 ka is still debatable (Germonpré et al. 2009; Napierala and Uerpmann 2010), but it clearly preceded the visible Holocene domestication of plants and other animals.

Archaeological evidence of plant domestication is persuasive because agricultural production requires tilling the soil with specialised tools, harvesting useful plant parts, storing harvested products in pits or containers, and processing plant matter into edible forms (grinding, pounding, baking, boiling, fermenting). All these activities require the use of specific implements or constructions that, in large part, are durable enough to persist for millennia. Agricultural production of food quantities required to support local populations of high density is relatively easy, removing the need for nomadism and allowing people to invest energy in the construction of permanent settlements (villages, towns, cities) from durable materials.

Food production through animal husbandry is efficient, but its archaeological evidence is less abundant due to the nature of this type of production. When and where animal husbandry was linked to agricultural production, such as in domesticating pigs or fowl, it is visible archaeologically as a part of permanent constructions to hold animals and implements used to process animal produce: corrals, barns, dairy, meat, wool, hides and horns. However, for populations of pastoralists and herders, the long-lasting material evidence is harder to find archaeologically. Herders follow the herds, so they have no permanent settlements. Their dwellings and other constructions are either transportable (e.g. yurts, tents) or temporary and made of perishable materials (pit houses, lean-tos, shacks, kraals for cattle). Specific implements related to herding are either perishable (whips, clubs, ropes, sticks) or of non-specific application (knives, spears, axes). Processing and storage of products of butchery can be carried out without containers; meat is either roasted or smoked or dried, or even fermented, while fresh animal fat is solid in temperate climate temperatures not requiring special containers. Dairy processing requires the use of containers, which can, however, be made of animal hides or plant gourds that are perishable. Therefore, archaeological evidence of pastoralism and animal husbandry is less abundant.

The evidence of animal domestication can be found in non-perishable animal remains. Shapes and sizes of bones and teeth of domesticates may have differed from those of their wild counterparts — we have mentioned already smaller brains and the whole suite of characters changed by the domestication syndrome. Selective breeding clearly produces genetic differences now detectable by ancient DNA and proteomics analyses (Hendy 2021; Warinner et al. 2022). Recovery of energy invested into care for domesticated animals makes people who exploit them use practically all parts of their bodies, rather than just butcher the most valuable parts of the carcass. Careful study of faunal remains, especially those related to human settlements, may indicate early stages of management leading to domestication (Larson and Fuller 2014).

Animal husbandry can develop gradually as people initially follow wild herds of animals and harvest them occasionally, slowly increasing their coexistence with herds and intervening in their biological dynamics (Zeder 2015). Coexistence of humans with herds or flocks of animals is beneficial for human food acquisition compared to occasional hunting, as animals become used to human presence while humans learn how to influence herd composition and what prey to kill, to better suit their needs. An example is animal tolerance of human presence (tameness, lack of flight response). They are then easier to exploit than when an unfamiliar hunter approaches an animal. Furthermore, herders can protect animals from predator attacks, thus preventing a reduction of herd sizes. All these activities are archaeologically invisible because they leave no durable objects of material culture. However, by increasing the useful human carrying capacity of the environment, they contribute to all elements of the set of feedback loops running human evolution (

Figure 1). Thus, with herding or pastoral care of animals, human anatomy and physiology, technologies (kinds of artefacts, their shapes and sizes, decorations, materials used), social organization, population densities, mental capacities, language and even sexual behaviours, can all change.

There is abundant evidence of changed technologies (lithic “cultures” or industries, sewing needles, jewellery, artistic expressions) in the Upper Palaeolithic. Human anatomy shifts from a robust to a more gracile appearance, with a clear reduction in the size of the masticatory apparatus and other robust features. These latter changes can be attributed to human self-domestication (Bednarik 2008, 2011, 2020). There is also fossil and genetic evidence of commensal domestication of canids, predators who feed, among others, on large herbivores, reaching back well in time. Why could human and canine domestications occur without this phenomenon already spreading to many herding or flocking animals?

It is, however, the process of artificial selection of breeding animals that introduces the domestication syndrome (Hammer 1984; Price 2002; Wilkins et al. 2014). It is not clear at what stage of human-animal coexistence the management of breeding takes place. With human ability to provide alloparenting, the ability to see some mammal or a bird as an individual deserving care is thinkable. One of many possible interpretations of representations of individual herbivorous animals in cave art is that they were actual or desired ‘pets’ of artists who painted them, individuals having a special meaning for the human-animal relationship. Some of the depictions of carnivores, e.g. lions, show them not as attacking predators, but as quiet individuals, either potential competitors or perhaps commensals. Heads and faces of some animals in both rock and mobile art are given more attention than their entire bodies. Perhaps a sign of an impersonation rather than just an objective depiction? True enough, more recent rock art contains apparent scenes of people with ‘weapons’ approaching animals. Those using bows and arrows were most likely hunting, but users of spears or knives could be slaughtering tame individuals. Moreover, some scenes do not show people intent on killing animals depicted next to them.

A large portion of the evidence of Upper Palaeolithic human activities comes from the temperate zone of Eurasia. In the Earth’s temperate terrestrial zones, the carrying capacity of the environment usable for pre-industrial humans consists of forests and grasslands. These do not contain enough wild food sources extractable by foragers throughout all seasons of the year, if large mammals are excluded. The almost countless mass extinctions of large mammals and birds marking the Final Pleistocene seem to reflect either the impoverishment of the carrying capacity of the human environment by natural forces, or the environmental stress introduced by growing human populations overexploiting available resources. Managed to some extent flocks/herds of large mammals may have allowed the growth of Upper Palaeolithic human populations that enabled the whole set of feedback loops acting in human evolution to reach the level of greater technological and social complexity. With the Terminal Pleistocene climate change, management of herds became insufficient to sustain their existence resulting in depopulation. The oldest evidence of animal husbandry recognized by students of human history comes from the terminal Upper Palaeolithic, just before the early Holocene, more than 12 ka before present, likely before the dates of the solid evidence of agricultural activities (Zeder 2015). Most of the early archaeological evidence of animal husbandry, however, is linked to that of agriculture. This is probably the result of the earlier-mentioned lack of non-perishable objects related to early animal husbandry, which may date back to the mid-Upper-Pleistocene, if not even earlier, to the origin of anatomical evidence for the “modern” humans.

In the caves of Bacho Kiro, Les Cottes and La Ferrassie, spanning the transition from the Middle to the Upper Palaeolithic, faunal assemblages undergo a transition from being partly accumulated by carnivores in the MP to being exploited almost exclusively by humans in UP, who changed their selection of fauna towards reindeer and equids (Sinet-Mathiot et al. 2023). There is no direct evidence that such selection was some initial form of herding, but changes in the most often consumed animal carcasses may indicate deliberate choice. It so happens that reindeer are amenable to interactions with humans, while horses seem to be similarly disposed.

2. The Case of the Reindeer

Here, we will consider the complexities and potential pitfalls of contrasting the domestication histories and effects on some different species by comparing what we know about significantly different scenarios and their outcomes. We illustrate this with the impact of endeavours to control populations of reindeer, a species that has experienced only partial domestication, which led to a seemingly stable symbiosis with humans (Beach and Stammler 2006). This will then be contrasted with much more intensively domesticated species and with the self-domestication of hominins, effectively in the absence of a domesticator. We intend to avoid anthropocentric perspectives as much as possible.

The reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) ranges widely in the circumpolar region of both Eurasia and North America and has been extensively ‘semi-domesticated’ from northern Scandinavia to eastern Siberia. It is the only species of its genus but has been divided into eight subspecies (Harding 2022). About one-half of the five million reindeer now living are domestic herds, but they continue to interbreed with wild herds. Studies of reindeer mtDNA suggest that domestication occurred in at least two widely separated regions, perhaps 2–3 ka ago in eastern Siberia and then in Fennoscandia, possibly in Medieval times (Røed et al. 2018). Further independent establishment of the practice elsewhere is possible. The most likely trigger of domestication is that human groups followed wild herds for prolonged periods, culling animals as needed while protecting herds against wolf attacks. However, some reindeer still fear humans today, and the habituation process is incomplete, relative to the principal mammalian domesticates.

Stépanoff (2012), who studied the small herding system of the Tozhu people of eastern Tuva, Siberia, provides much insight into the domestication practices. The herders depend significantly on their animals to support them, providing them with milk and labour in the form of transport of people and goods, and occasionally with meat , skins and antlers. When an animal is to be killed, an ill, wounded, old or rebellious individual is chosen. The latter trait contributes to artificial selection, changing the genome towards docility. The practice of castrating most of the males, keeping just one carefully chosen buck per thirty females, increases docility, too. Castrated males are destined to become pack animals. Similarly, female leaders in the herd that prompt others to flee from humans are preferentially slaughtered. The reindeer are free to wander into the taiga, even join a wild herd, and one factor bringing them back to the camp is the promise of salt or human urine to lick. For the latter, the Tozhu construct wooden urinals at a convenient height. Young fawns receive salt, even sugar, while they are tied up without their mothers. Importantly, it is the reindeer's prerogative to choose the timing and route of the annual migration (cf. Dwyer and Istomin 2008). The herders also respect the reindeer’s aversion to human infrastructures such as fences and buildings (Skarin and Åhman 2014). As Stépanoff (2012) poignantly observes, paradoxically, humans can domesticate reindeer only if they keep them relatively wild. Unlike most other human domesticates, reindeer are domesticated by (partly) nomadic people rather than by settled agriculturists.

The reindeer is one of the most recently domesticated mammal species, considering that the popular meme of the domestication of the rabbit by French monks in Medieval times (as a result of a Papal decree that rabbits are fish, permitting their consumption during Lent) is a falsity (Irving-Pease et al. 2018). This may explain the ‘incomplete’ state of domestication of reindeer, although peculiarities specific to it may also be implicated. These could include the logistical difficulties of migrating herds in forest and mountain regions, the impracticalities of corralling them in holding pens and the reindeer's reluctance to abandon flight responses entirely. The resulting symbiosis with humans remains underdeveloped, with some populations (the Fennoscandian breed) having been subjected to domestication only for several centuries. Therefore, the case of the reindeer provides an example of a domestication process that still has to run much of its course.

3. The Case of the Horse

Homo heidelbergensis and H. sapiens neanderthalensis have been hunting horses for several hundred millennia (e.g. at Boxgrove, Schöningen and Bilzingsleben), apparently by driving them over cliffs or spearing them at water sources. During the Upper Palaeolithic, Equus ferus ferus and Equus ferus przewalski were so widely hunted by humans that horses became extinct in much of Europe towards the end of that period, i.e. ~12 ka ago. The rich record of equid fossils from Eurasia and the Americas exemplifies evolutionary processes better than for most other clades (Weinstock et al. 2005). However, difficulties in distinguishing wild from domesticated horses hamper reliable interpretation (Benecke and Von den Dreisch 2003). Subtle differences occur in tooth morphology, cranial shape and overall bone size. Nevertheless, no single feature is definitive. The intricate folds of tooth enamel provide some differentiation (Heck et al. 2018), and wild animals tend to have larger, broader skulls with rounder braincases and less developed occipital condyles. The differences between wild and domestic specimens are more pronounced than in reindeer, but they are significantly less developed than in dogs, for example.

Concerning horse domestication, Bogaard et al. (2021) observed that “[t]he more extended in time a process unfolds, the greater the likelihood that the causal elements were diffuse and complex”. We suggest that this applies to all domestications. The complexities are well illustrated by the intricate difficulties relating to determining where horse domestication began, and the controversial status of the tarpan. It remains unclear whether this free-ranging horse (

E. ferus ferus), which became extinct in 1909, was a wild horse, feral domesticated horse or a hybrid of Przewalski's and domestic horses (Librado et al. 2021). It has been assumed that the only surviving wild horse is

E. ferus przewalskii, once occurring widely across Eurasia, but now limited to five protected herds in China and Mongolia (

Figure 2). This view has been challenged by Chalcolithic finds of the Botai, a horse-reliant culture of northern Kazakhstan (5500–5000 years BP; Outram et al. 2009). The gracility of the metacarpals of the Botai horses and other factors suggest that they experienced domestication, but they are thought to be of Przewalski's horse. After this was confirmed by DNA analysis, it was challenged by rejecting the idea that this subspecies was ever domesticated (Taylor and Barrón-Ortiz 2021).

Since the skeletal evidence of distinguishing domestic from wild horses remained so ambiguous, archaeological indicators have also been consulted (Ludwig et al. 2009). They include fat residues from the insides of ceramic vessels believed to be from horse milk and found among remains of the Botai culture, and dental evidence of bit wear from the same context (Brown and Anthony 1998). The Khvalynsk culture on the Middle Volga, west of the Ural Mountains, has been suggested to be even earlier (up to 6800 years BP) and is credited with having domestic horses (Levine 1999; Olsen 2003; Anthony and Brown 2000). The evidence for this includes post-moulds of presumed animal pens containing horse dung, and the skeletal remains of 16 horses, believed to be sacrificial, from the Eneolithic cemetery of the type site. The Samara tradition, which predates the Khvalynsk culture, dates to the early fifth millennium BCE and has produced horse bones from human graves. However, it is unclear if these horses were domesticated or simply part of grave goods. The most reliable evidence for equine domestication has been provided by the Sintashta culture, a Middle Bronze Age archaeological tradition of the southern Urals, dated to the period 4200–3900 years BP. It has provided chariots that were buried with horses. Chariots appear in the southern Trans-Urals region in the middle and late phases of the culture, c. 4050–3750 years BP (Anthony 2007; Lindner 2020).

The credible proposals for the beginning of horse domestication are thus from the steppes of southern Russia and Kazakhstan. Accordingly, it occurred between 7000 and 4000 years ago in that general region. However, the find of a buried horse in the Eneolithic site of Le Cerquete-Fianello near Rome narrows this estimate further (Bednarik 1996). The Chalcolithic ends about 4200 years BP in Italy, so it is reasonable to suggest that the domestication of the horse occurred between 7000 and 4200 years ago, based on the present evidence. Proposals for alternative independent domestication of E. caballus, such as in the Arabian Peninsula, lack supporting evidence and conflict with available genetic evidence (Bednarik 2012).

The outlined archaeological chronology has been partially confirmed by genetics. Liu et al. (2025) detected positive selection of ZFPM1 in samples about 5000 years old, leading to intensive selection of GSDMC (encoding the protein Gasdermin C) about 250 years later. The first gene is implicated in behavioural changes (e.g. towards docility), the second is associated with spinal stenosis, among other factors. This second change is attributed to the introduction of horse riding and the consequent strengthening of the spinal column. One of the concerns with riding on reindeer is that the rider must be careful not to damage the animal’s spinal column. For instance, they use the support of a tree stump to mount “without harming the animal’s back” (Stépanoff 2012). This confirms not only that the horse has been domesticated significantly earlier than the reindeer, but it also provides a rough timescale for specific developments.

4. The Case of Bovids

Sheep, goats and cattle were most likely domesticated following the “prey” route (Zeder 2015), meaning that people who hunted them gradually developed ways to manage herds or flocks in which they tended to harvest specific age/sex groups (e.g. young males while protecting breeding females) and eventually limited herd mobility and controlled their reproduction. There is evidence of both human management strategies and morphological modifications of ungulates leading to the “domestication syndrome” from the Euphrates Basin at around 10.5 ka ago (Peters et al. 2005; Helmer et al. 2005).

Goats were domesticated in the area of southwestern Asia (Turkey-Pakistan) from mountain goats (Capra aegagrus) as evidenced by zooarchaeological and genetic studies (Naderi et al. 2008; Amills et al. 2017). However, nuclear DNA studies indicate numerous admixtures from other wild goat populations (Daly et al. 2018), both at the time of domestication and later when domesticates were spread to all habitable continents.

Sheep followed a similar path to domestication. Their progenitor in SW Asia was likely the mouflon (Ovis orientalis), though other Ovis species of the same area are possible alternatives (Bruford and Townsend 2006). Recent genetic studies (Kaptan et al. 2024; Daly et al. 2025) confirmed this statement but also indicated a possible mosaic of domestic sheep ancestors. Due to the number of ways sheep were exploited — milk, wool, meat and even horns — morphologies of domesticates are varied depending on which aspect of economic utility was specifically desired by local domesticators. Initially, sheep were reared for meat; only later, their other products became of interest to domesticators (Chessa et al. 2009). Wool production attracted most attention, leading to the creation of a number of breeds differing in the quality and colour of coats.

Cattle were domesticated from more than one wild ancestor. One of them was aurochs (Bos primigenius), an Eurasian wild cattle; another an African aurochs (Bos taurus) and yet another one from Asia (Bos indicus) known as zebu (Decker et al. 2014; Teasdale and Bradley 2012). Whether the domestication of each of these wild ancestors was an independent event or initially domesticated Eurasian cattle mixed with other wild aurochs, acquiring their genetic signatures, is still unclear. The independent African ancestry is unlikely (Pitt et al. 2019). In terms of the antiquity of cattle’s domestication, it is interesting that cattle, together with other domesticates, were transferred to Cyprus at least 10 ka ago (Vigne 2011). Such transport necessitated covering a distance of tens of kilometres on the open sea with heavy animals, their fodder and water on board a large vessel. Sustained presence of domesticated bovids on the island proves that the maritime transport of large animals was not a single random event, but a planned, organized activity, since at the very least several animals of both sexes had to be successfully transported to initiate a viable herd. The presence of cows in Cyprus proves not only the ability of their owners to build and operate large navigable vessels, but also their advanced skills of caring for domestic animals at least 10 ka ago. Such skills must have been developed and refined substantially earlier. Considered in the light of the taphonomic logic (see below), it indicates that significant management of cattle must have started some millennia before their first sea voyage.

5. The Case of the Wolf/Dog

Canis lupus developed a commensal relationship with humans early on when the waste of human consumption of animals’ bodies became abundant enough in camp areas to attract scavengers. Since wolves are animals living in social groups, they were likely to consider humans as members of their social relationships. Even today, domesticated dogs consider their human owners as pack leaders. This commensal relationship between canids and humans strengthened over time when canids expanded their symbiotic activities with humans beyond just consuming the refuse of human hunting and joined hunters as part of their hunting packs. There were suggestions, based on analyses of canid skeletal remains, that early domestication occurred as early as 36–31 ka ago (Germonpré et al. 2009, 2012; Ovodov et al. 2011). These findings were challenged (Perri 2016). Therefore, it is difficult to establish when early changes leading to the formation of domestic dog lineages started to happen. The commonly accepted date of post hoc domestication has been suggested as about 15 ka based on both archeozoological and genetic studies (Skoglund et al. 2015; Freedman et al. 2016; Frantz et al. 2016, 2020; Thalmann and Perri 2018). Around 12 ka, were present at numerous archaeological sites across Eurasia (Larson et al. 2012).

6. Hominin Domestication

If it were possible to show that domestication of mammals began at least at the beginning of the Late Pleistocene, it would be easier to understand how humans could use principles of domestication in the organization of the life of human societies — provided we assumed that auto-domestication was deliberate. Human self-domestication would not stand alone as an exceptional process but rather be a natural consequence of changing relations between humans and nature. However, hominin self-domestication was completely unintentional. Conversely, self-domestication has also been attributed to other species (dog, bonobo, possibly elephant; Groves 1999).

The hypothesis that the introduction of human modernity is the result of the domestication of robust Homo sapiens populations occurring during the last third of the Late Pleistocene was a response to the replacement hypothesis, also labelled African Eve theory. Unable to attribute that relatively sudden appearance of “modern” humans in Europe to evolution, that meme had ascribed the change from robust to gracile hominins to a speciation event in sub-Saharan Africa, leading to a cognitively superior species that replaced all human populations of the world by outcompeting or eradicating them. Initially based on a hoax by a German biological anthropology professor in the 1970s (Bednarik 2013), the replacement hypothesis has been contradicted by genetic evidence in recent years: Neanderthals, Denisovans and extant humans are one species. The inability of scholars to explain how the teleological ‘anatomically modern human’ could have evolved in a geological instant (a few tens of millennia) prompted them to propose the mass migration of a new species. However, there is no substantive evidence in favour of this notion, be it anthropological, archaeological, demographic or genetic. Moreover, the replacement theory provides no plausible explanation for any aspects of human modernity, be they somatic changes, susceptibility to countless detrimental conditions and maladaptations, brain atrophy, loss of oestrus, genetic impairments or general neotenization. The domestication hypothesis, by contrast, explains all these factors exhaustively as the outcomes of a process capable of transforming an entire species within very few millennia: the pleiotropic effects of domestication (Bednarik 2008, 2011, 2020).

Better acquisition of energy from animal sources at the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic could have produced larger local human populations. Whether the total number of humans in the world or on some continent has increased is irrelevant here. It is the size of a local population of humans who interact with each other in economic and cultural activities and, inevitably, in sexual ones, that is important. Egalitarian local populations of foragers consist of a few hundred individuals (Birdsell et al. 1973). Increasing extractive efficiency by some form of management of large mammals could increase this size several times. Population size increase could lead to social stratification, which is suggested by the increasing use in the Upper Palaeolithic of body decoration, in some instances, grossly exaggerated (e.g. Sungir’ burials; Bader 1978). Prompted by closer observation of animals, revealing the role of sexual intercourse in reproduction, humans could have decided to control the sexual activities of their children, via marital rules, to achieve desired particular characteristics of their offspring and perpetuate emerging social structures.

7. Taphonomic Logic to the Fore

Are these realistic speculations? How secure can archaeology’s interpretation of the evidence for domestications be regarded?

In the interpretation of all empirical evidence of the past, the concept of taphonomic logic is paramount. It derives from the principles of taphonomy, the discipline introduced by Efremov (1940) when he tried to counter actuopalaeontology, the explanation of the palaeontological record as a literal reflection of the living system (see Solomon 1990 for a superb discussion). It took archaeologists, forensic scientists, rock art researchers and others more than forty years to realise that the generic issues of taphonomy have significant applications in their fields as well. Bednarik (1994) formulated these underlying principles and proposed that the ‘ratio’ between the ‘quantified’ event or living system and the surviving evidence of it can be expressed as an integral fraction. Whilst the original concept of taphonomy addressed the decay, disarticulation, dispersal, accumulation, fossilization and mechanical alteration of palaeontological evidence, taphonomic logic focused on the progressive loss with time of evidence deriving from events or phenomena of the past that need to inform their interpretation in the present. They might include the methods of recovery of evidence, its reporting and selective dissemination, its statistical treatment, or even the individual researcher's own biases and limitations. These tendencies are likely to be systematic, and there should be no doubt that there is a very considerable gap between the reality of what happened in the distant past and the abstraction of it as perceived by the individual archaeologist interpreting a specific, subjectively selected and non-random sample of evidence truncated in various ways.

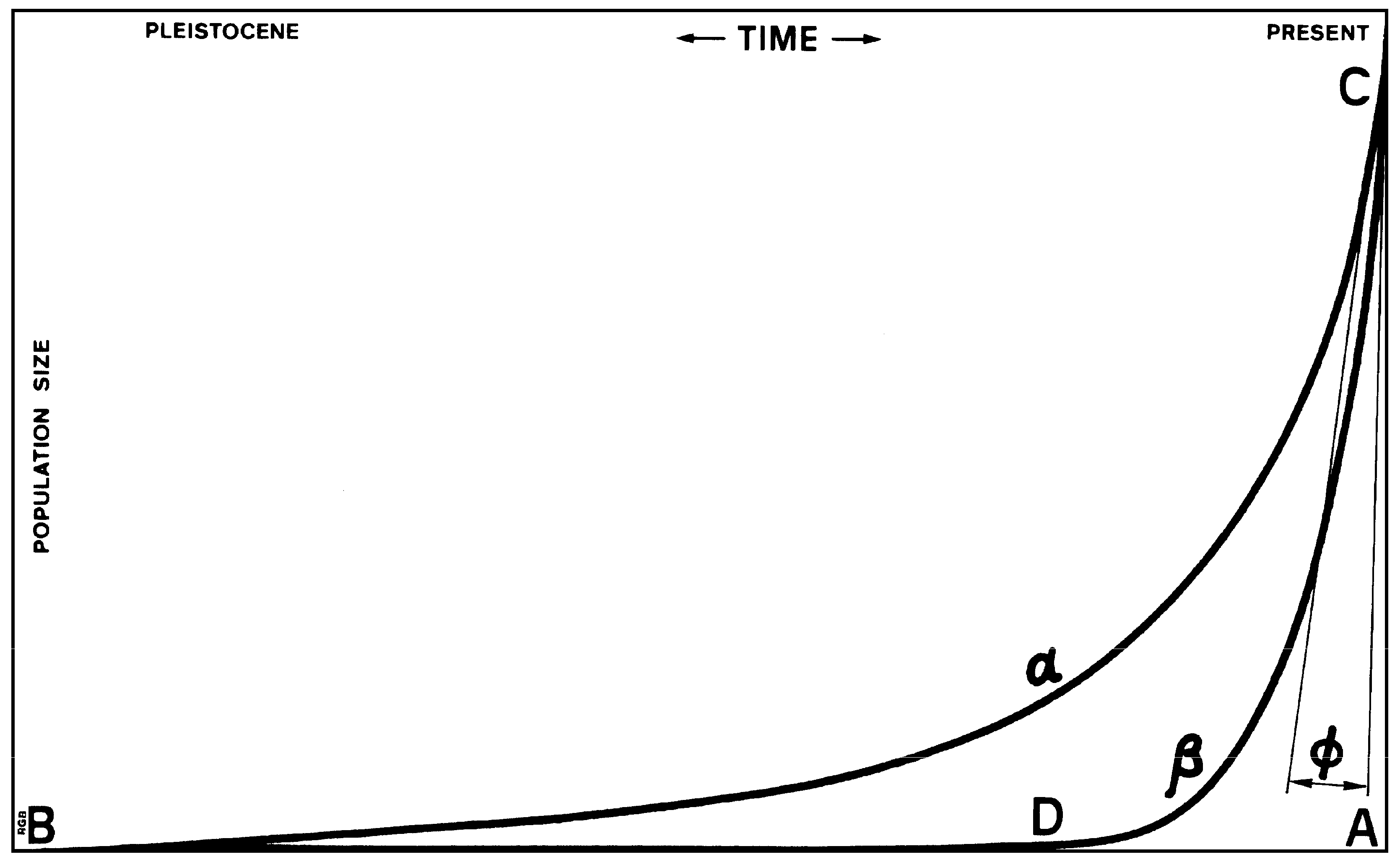

The most significant principle of taphonomic logic is the relationship between the surviving evidence of a phenomenon and its actual occurrence in the living system (

Figure 3). In this graph, the alpha curve represents all examples of a specific phenomenon ever created, say, every bead made. Most of these may not have survived, so the beta curve represents those collected, correctly interpreted and disseminated. Assuming we experience a loss of 10% of beads in one time-unit (which may be a century or a millennium or whatever), the loss in two time-units should be in the order of twice that, and so on. After ten or so time-units, the bead population has largely vanished. However, a zero-probability of survival of any archaeological phenomenon is not possible. Therefore, while the ‘preservation bias’ forces the beta curve away from the alpha curve as we proceed back in time, the ‘equilibrium bias’ prevents it from touching the zero-population abscissa. So, as it approaches the abscissa, the beta curve forms a parabola at point D, the ‘taphonomic threshold’. From there on back in time, it hovers close to the abscissa, touching it only before point B, when beads were first made. The number of surviving specimens is so low that archaeology would be either incapable of detecting them, or if it did, it might reject them as stray occurrences, as intrusive, or as “running ahead of time” (Vishnyatsky 1994). The latter rationalisation is particularly detrimental to archaeology because it systematically dismisses the most relevant available evidence of hominin cognition or technical ability, when scientific access to the human past is contingent on the coherent identification of that part of the extant characteristics of the evidence that is

not the result of taphonomic processes.

Taphonomic logic demands that particular attention be paid to the taphonomic lag-time preceding the common occurrence of each archaeological phenomenon category. In many of these categories, the lag-time is likely to be in excess of 99% of the phenomenon’s currency. Examples of very long lags have been documented, for instance, in the beginnings of presumed use of symbolism (including language), maritime colonisation (particularly affected by the taphonomy attributable to sea-level changes) or the use of perishable materials (wood, adhesives, string, clothing, etc.). All phenomenon categories strongly affected by taphonomic processes can only provide very conservative maximum ages, and it is expected that their historical duration extends much further back in time than commonly assumed in archaeology.

8. Discussion

Here, we are concerned with the extension of this generic principle to the question of when humans began to domesticate other animals. Most certainly, it was earlier than the times from which we have sound evidence of the origins of such practices. This evidence would show that the taxa in question had been subjected to the domestication syndrome, physiologically or behaviourally. However, domestication is a lengthy process rather than a definable moment, involving various stages, and it is, in most if not all cases, continuing. The case of the reindeer illustrates. Although reindeer herders can distinguish between wild and domesticated individuals, there appear to be no skeletal differences between the two. Pleiotropic effects seem to be undetectable, and the animal’s migrations continue to be determined by the herds rather than the herders. The current state can be defined as “incipient” domestication.

The appearance of cattle in Cyprus 10,000 years ago provides sound evidence that they were transported in adequate numbers on sea-going vessels. We can safely assume that would have only been possible with domesticated animals. Therefore, at present, it appears that the complex domestication of cattle followed the domestication of the wolf, the timing of which remains unresolved. It was accompanied by the domestication of the ovicaprids ~12,000 – 10,000 years ago. Of particular interest is the gradual spreading of these bovids from the Fertile Crescent across northern Africa from east to west (Muzzolini 1990).

Evidence of human “anatomical modernity” began appearing in Europe about 40 ka ago and has been attributed to unintentional self-domestication of robust hominins. Does Palaeolithic resource management leading to domestication via taming or herding explain human “modernity”?

Most certainly, taphonomic logic decrees that animal husbandry of bovids and other taxa must have begun earlier than the time of the first clear archaeological evidence of such practices. Such empirical evidence cannot be expected from the “lag-time” of the phenomenon category, which remains of unknown duration. An additional encumbrance is that it seems very hard to secure proof of taming or herding. Nevertheless, as the pleiotropic effects of the hominin auto-domestication begin appearing around 30 ka before those of ungulates, it is most unlikely that the question in this paper’s title can be answered in the affirmative. In the case of the hominins, the pleiotropic consequences of domestication are amply manifest. For the domesticated animals, a realistic taphonomic lag-time needs to be ascertained.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H. and R.B. Methodology, M.H. and R.B. Writing – Original Draft Preparation, M.H. and R.B. Writing – Review & Editing, M.H. and R.B.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data used for this paper have been already published and are available in the literature.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amills, M., Capote, J. and Tosser-Klopp, G., 2017. Goat domestication and breeding: a jigsaw of historical, biological and molecular data with missing pieces. Animal genetics, 48(6), pp.631-644.

- Anthony, D. W. 2007. The horse, the wheel, and language: how Bronze Age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- Anthony, D. W. and D. Brown 2000. Eneolithic horse exploitation in the Eurasian steppes: diet, ritual and riding. Antiquity 74: 75–86.

- Bader, O. N. 1978. Sungir’: verkhnepaleoliticheskaya stoyanka. Izdatel’stvo “Nauka”, Moscow.

- Beach, H. and F. Stammler 2006. Human–animal relations in pastoralism. Nomadic Peoples 10(2): 6–29.

- Beaumont, P. B. 2011. The edge: more on fire-making by about 1.7 million years ago at Wonderwerk Cave in South Africa. Current Anthropology 52: 585–595.

- Bednarik, R. G. 1994. A taphonomy of palaeoart. Antiquity 68: 68−74.

- Bednarik, R. G. 1996. Eneolithic horse burial in Italy. The Artefact 19: 102–103.

- Bednarik, R. G. 2008. The domestication of humans. Anthropologie 46(1): 1–17.

- Bednarik, R. G. 2011. The human condition. Springer, New York.

- Bednarik, R. G. 2012. The Arabian horse in the context of world rock art. In M. Khan (ed.), The Arabian horse: origin, development and history, pp. 397–425. Layan Cultural Foundation, Riyadh.

- Bednarik, R. G. 2013. African Eve: hoax or hypothesis? Advances in Anthropology 3(4): 216–228; http://www.scirp.org/journal/PaperInformation.aspx?PaperID=39900#.U5JvUnYUqqY.

- Bednarik, R. G. 2020. The domestication of humans. Routledge, London/New York.

- Benecke, N. and A. Von den Dreisch 2003. Horse exploitation in the Kazakh steppes during the Eneolithic and Bronze Age. In M. Levine, C. Renfrew and K. Boyle (eds), Prehistoric Steppe adaptation and the horse, pp. 69–82. McDonald Institute, Cambridge.

- Birdsell, J.B., Bennett, J.W., Bicchieri, M.G., Claessen, H.J.M., Gropper, R.C., Hart, C.W.M., Kileff, C., Posinsky, S.H. and Thompson, L., 1973. A basic demographic unit [and comments and reply]. Current Anthropology, 14(4): 337-356.

- Birks, J. D. S. and A. C. Kitchener 1999. The distribution and status of the polecat Mustela putorius in Britain in the 1990s. Vincent Wildlife Trust, London.

- Bogaard, A., R. Allaby, B. S. Arbuckle, R. Bendrey, S. Crowley, T. Cucchi, T. Denham, L. Frantz, D. Fuller, T. Gilbert, E. Karlsson, A. Manin, F. Marshall, N. Mueller, J. Peters, C. Stépanoff, A. Weide and G. Larson 2021. Reconsidering domestication from a process archaeology perspective. World Archaeology 53(1): 56–77;. [CrossRef]

- Boitani, L. and P. Ciucci, P. 1995. Comparative social ecology of feral dogs and wolves. Ethology, Ecology & Evolution 7(1): 49–72.

- Brown, D. and D. Anthony 1998. Bit wear, horseback riding and the Botai site in Kazakhstan. Journal of Archaeological Science 25(4): 331–347.

- Brown, T. A., M. K. Jones, W. Powell and R. G. Allaby 2008. The complex origins of domesticated crops in the Fertile Crescent. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 24: 103–109.

- Bruford, M.W. and Townsend, S.J., 2006. Mitochondrial DNA diversity in modern sheep. Documenting domestication: New genetic and archaeological paradigms, pp.306-316.

- Chessa, B., Pereira, F., Arnaud, F., Amorim, A., Goyache, F., Mainland, I., Kao, R.R., Pemberton, J.M., Beraldi, D., Stear, M.J. and Alberti, A., 2009. Revealing the history of sheep domestication using retrovirus integrations. Science, 324(5926): 532-536.

- Clark, G. and M. Henneberg 2017. Ardipithecus ramidus and the evolution of language and singing: an early origin for hominin vocal capability. JCHB Homo 68(2): 101-121.

- Clark, G., Saniotis, A., Bednarik, R., Lindahl, M., & Henneberg, M. (2024). Hominin musical sound production: palaeoecological contexts and self-domestication. Anthropological Review, 87(2): 17–61. [CrossRef]

- Daly, K.G., Maisano Delser, P., Mullin, V.E., Scheu, A., Mattiangeli, V., Teasdale, M.D., Hare, A.J., Burger, J., Verdugo, M.P., Collins, M.J. and Kehati, R., 2018. Ancient goat genomes reveal mosaic domestication in the Fertile Crescent. Science, 361(6397): 85-88.

- Daly, K.G., Mullin, V.E., Hare, A.J., Halpin, Á., Mattiangeli, V., Teasdale, M.D., Rossi, C., Geiger, S., Krebs, S., Medugorac, I. and Sandoval-Castellanos, E., 2025. Ancient genomics and the origin, dispersal, and development of domestic sheep. Science, 387(6733): 492-497.

- Decker, J.E., McKay, S.D., Rolf, M.M., Kim, J., Molina Alcalá, A., Sonstegard, T.S., Hanotte, O., Götherström, A., Seabury, C.M., Praharani, L. and Babar, M.E., 2014. Worldwide patterns of ancestry, divergence, and admixture in domesticated cattle. PLoS genetics, 10(3), p.e1004254.

- Dwyer, M. J. and K. V. Istomin 2008. Theories of nomadic movement: a new theoretical approach for understanding the movement decisions of Nenets and Komi reindeer herders. Human Ecology 36(4): 521–533.

- Efremov, J. A. 1940. Taphonomy: a new branch of paleontology. Pan American Geologist 74(2): 81−93.

- Frantz, L.A., Mullin, V.E., Pionnier-Capitan, M., Lebrasseur, O., Ollivier, M., Perri, A., Linderholm, A., Mattiangeli, V., Teasdale, M.D., Dimopoulos, E.A. and Tresset, A., 2016. Genomic and archaeological evidence suggest a dual origin of domestic dogs. Science, 352(6290): 1228-1231.

- Frantz, L. A. F.; Bradley, D. G.; Larson, G.; Orlando, L. 2020. Animal domestication in the era of ancient genomics. Nature Reviews Genetics 21 (8): 449–460.

- Freedman, A. H.; Schweizer, R. M.; Ortega-Del Vecchyo, D.; Han, E.; Davis, B. W.; Gronau, I.; Silva, Pedro M.; Galaverni, M.; Fan, Z.; Marx, P.; Lorente-Galdos, B.; Ramirez, O.; Hormozdiari, F.; Alkan, C.; Vilà, C.; Squire, K.; Geffen, E.; Kusak, J.; Boyko, A. R.; Parker, H. G.; Lee, C.; Tadigotla, V.; Siepel, A. Bustamante, C. D.; Harkins, T. T.; Nelson, S. F.; Marques-Bonet, T.; Ostrander, E. A.; Wayne, R. K.; Novembre, J. 2016. Demographically-based evaluation of genomic regions under selection in domestic dogs. PLOS Genetics 12(3): e1005851;. [CrossRef]

- Germonpré, M., M. V. Sablin, R. E. Stevens, R. E. M. Hedges, M. Hofreiter, M. Stiller and V. R. Després 2009. Fossil dogs and wolves from Palaeolithic sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: osteometry, ancient DNA and stable isotopes. Journal of Archaeological Science 36(2): 473–490.

- Germonpré, M., Laznickov, Galetov, M., Sablin, M.V., 2012. Palaeolithic dog skulls at the Gravettian Předmostí site, the Czech Republic. J. Archaeol. Sci. 39 (1),184e202.

- Groves, C. P. 1999. The advantages and disadvantages of being domesticated. Perspectives in Human Biology 4: 1–12.

- Hammer, K. 1984. Das Domestikationssyndrom. Kulturpflanze 32: 11–34.

- Harding, L. E. 2022. Available names for Rangifer (Mammalia, Artiodactyla, Cervidae) species and subspecies. ZooKeys 1119: 117–151;. [CrossRef]

- Harlan, J. R., J. M. J. De Wet and E. G. Price. 1973. Comparative evolution of cereals. Evolution 27(2): 311–325;. [CrossRef]

- Heck, L., L. A. B. Wilson, A. Evin, M. Stange and M. R. Sánchez-Villagra 2018. Shape variation and modularity of skull and teeth in domesticated horses and wild equids. Frontiers in Zoology 15: 14;. [CrossRef]

- Helmer, D., L. Gourichon, H. Monchot, J. Peters, M. San˜a Segui 2005. Identifying early domestic cattle from Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites on the Middle Euphrates using sexual dimorphism, in: J.D. Vigne, J. Peters, D. Helmer (Eds.), First Steps of Animal Domestication. New Archaeozoological Approaches, Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp. 86–95.

- Hendy, J., 2021. Ancient protein analysis in archaeology. Science Advances, 7(3), p.eabb9314.

- 42. Henneberg M, 1988. Decrease of human skull size in the Holocene, Human Biology 60: 395–405.

- Henneberg M. 2025. Our one human family. A story of continuing evolution. NOVA Publishers, New York.

- Henneberg, M. and Eckhardt, R. B., 2022. Evolution of modern humans is a result of self-amplifying feedbacks beginning in the Miocene and continuing without interruption until now. Anthropological Review, 85(1): 77–83.

- 45. Henneberg M, Ostoja-Zagorski J, 1984, Use of a general ecological model for the reconstruction of prehistoric economy: The Hallstatt Period culture of northwestern Poland. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 3:41-78.

- Henneberg M., Wolanski N., 2009. Human ecology, economy and the global system. In: Anthropology Now, P.J.M. Nas and A. Jijiao (eds), Intellectual Property Rights Publishing House, China. 356-369.

- Henriksen, R., M. Johnsson, L. Andersson, P. Jensen and D. Wright 2016. The domesticated brain: genetics of brain mass and brain structure in an avian species. Scientific Reports 6: 34031.

- Irving-Pease, E. K., L. A. F. Frantz, N. Sykes, C. Callou and G. Larson 2018. Rabbits and the specious origins of domestication. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 33(3): 149–152.

- Johnsson, M., R. Henriksen and D. Wright 2021. The neural crest cell hypothesis: no unified explanation for domestication. Genetics 219(1): iyab097;. [CrossRef]

- Kaptan, D., Atağ, G., Vural, K.B., Morell Miranda, P., Akbaba, A., Yüncü, E., Buluktaev, A., Abazari, M.F., Yorulmaz, S., Kazancı, D.D. and Küçükakdağ Doğu, A., 2024. The population history of domestic sheep revealed by paleogenomes. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 41(10), p.msae158.

- Kruska, D. 1988. Mammalian domestication and its effect on brain structure and behaviour. In H. J. Jerison and I. Jerison (eds), Intelligence and evolutionary biology, pp. 211–250. Springer, New York.

- Larson, G., Karlsson, E.K., Perri, A., Webster, M.T., Ho, S.Y., Peters, J., Stahl, P.W., Piper, P.J., Lingaas, F., Fredholm, M. and Comstock, K.E., 2012. Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archeology, and biogeography. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(23): 8878-8883.

- Larson G. and Fuller, D.Q., 2014. The evolution of animal domestication. Annual review of ecology, evolution, and systematics, 45(1),: 115-136.

- Levine, M. A. 1999. Botai and the origins of horse domestication. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 18(1): 29–78.

- Librado, P., N. Khan, A. Fages, M. A. Kusliy, T. Suchan, L. Tonasso-Calvière, S. Schiavinato, D. Alioglu, A. Fromentier, A. Perdereau, J.-M. Aury, C. Gaunitz, L. Chauvey, A. Seguin-Orlando and C. Der Sarkissian 2021. The origins and spread of domestic horses from the Western Eurasian steppes. Nature 598(7882): 634–640;. [CrossRef]

- Lindner, S. 2020. Chariots in the Eurasian steppe: a Bayesian approach to the emergence of horse-drawn transport in the early second millennium BC. Antiquity 94(374): 361-380.

- Liu X., Jia Y., Pan J., Zhang Y., Gong Y., Wang X., Ma Y., N. Alvarez, Jiang L. and L. Orlando 2025. Selection at the GSDMC locus in horses and its implications for human mobility. Science 389(6763): 925–930;. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, A., M. Pruvost, M. Reissmann, N. Benecke, G. A. Brockmann, P. Castaños, M. Cieslak, S. Lippold, L. Llorente, A.-S. Malapinas, M. Slatkin and M. Hofreiter 2009. Coat color variation at the beginning of horse domestication. Science 324: 485;. [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, M. P. and G. A. Nevitt 2003. Effects of hatchery rearing on brain structures of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Environmental Biology of Fishes 66(1): 9–14.

- Muzzolini, A. 1990. The sheep in Saharan rock art. Rock Art Research 7(2): 93–109.

- Naderi, S., Rezaei, H.R., Pompanon, F., Blum, M.G., Negrini, R., Naghash, H.R., Balkız, Ö., Mashkour, M., Gaggiotti, O.E., Ajmone-Marsan, P. and Kence, A., 2008. The goat domestication process inferred from large-scale mitochondrial DNA analysis of wild and domestic individuals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(46): 17659-17664.

- Napierala, H. and H.-P. Uerpmann, 2010. A ‘new’ Palaeolithic dog from central Europe. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology;. [CrossRef]

- Olney, D., A. Saniotis and M. Henneberg 2015. Resource management and the development of Homo. Anthropos 110. 563–572.

- Olsen, S. L. 2003. The exploitation of horses at Botai, Kazakhstan. In M. Levine, C. Renfrew and K. Boyle (eds), Prehistoric steppe adaptation and the horse, pp. 83–104. McDonald Institute, Cambridge.

- Outram, A. K., N. A. Stear, R. Bendrey, S. Olsen, A. Kasparov et al. 2009. The earliest horse harnessing and milking. Science 323(5919): 1332–1335;. [CrossRef]

- Ovodov ND, Crockford SJ, Kuzmin YV, Higham TFG, Hodgins GWL, van der Plicht J (2011) A 33,000-Year-Old Incipient Dog from the Altai Mountains of Siberia: Evidence of the Earliest Domestication Disrupted by the Last Glacial Maximum. PLoS ONE 6(7): e22821. [CrossRef]

- Perri, A., 2016. A wolf in dog's clothing: Initial dog domestication and Pleistocene wolf variation. Journal of Archaeological Science, 68: 1-4.

- Peters, J., A. von den Driesch, D. Helmer 2005. The upper Euphrates-Tigris basin: Cradle of agropastoralism? in: J.D. Vigne, J. Peters, D. Helmer (Eds.), First steps of animal domestication. New archaeozoological approaches, Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp. 96–124.

- Pitt, D., Sevane, N., Nicolazzi, E.L., MacHugh, D.E., Park, S.D., Colli, L., Martinez, R., Bruford, M.W. and Orozco-terWengel, P., 2019. Domestication of cattle: Two or three events?. Evolutionary applications, 12(1): 123-13.

- Plogmann, D. and D. Kruska 1990. Volumetric comparison of auditory structures in the brains of European wild boars (Sus scrofa) and domestic pigs (Sus scrofa f. dom.). Brain, Behavior and Evolution 35: 146–155.

- Price, E. O. 1984. Behavioral aspects of animal domestication. Quarterly Review of Biology 59: 1–32.

- Price, E. O. 2002. Animal domestication and behavior. CABI Publishing, New York.

- Røed, K. H., I. Bjørklund and B. J. Olsen 2018. From wild to domestic reindeer. Genetic evidence of a non-native origin of reindeer pastoralism in northern Fennoscandia. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 19: 279–286.

- Schultz, W. 1969. Zur Kenntnis des Hallstromhundes (Canis hallstromi, Troughton 1957). Zoologischer Anzeiger 183: 42–72.

- Sinet-Mathiot, V., Rendu, W., Steele, T.E., Spasov, R., Madelaine, S., Renou, S., Soulier, M.C., Martisius, N.L., Aldeias, V., Endarova, E. and Goldberg, P., 2023. Identifying the unidentified fauna enhances insights into hominin subsistence strategies during the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 15(9), p.139.

- Skarin, A. and B. Åhman 2014. Do human activity and infrastructure disturb domesticated reindeer? The need for the reindeer’s perspective. Polar Biology 37(7): 1041–1054.

- Skoglund, P., Ersmark, E., Palkopoulou, E. and Dalén, L., 2015. Ancient wolf genome reveals an early divergence of domestic dog ancestors and admixture into high-latitude breeds. Current Biology, 25(11): 1515-1519..

- Smith, B.P., Lucas, T.A., Norris, R.M. and Henneberg, M., 2018. Brain size/body weight in the dingo (Canis dingo): comparisons with domestic and wild canids. Australian Journal of Zoology, 65(5): 292-301.

- Solomon, S. 1990. What is this thing called taphonomy? In S. Solomon, I. Davidson and D. Watson (eds), Problem solving in taphonomy: archaeological and palaeontological studies from Europe, Africa and Oceania, pp. 25–33. Tempus, Archaeology and Material Culture Studies in Anthropology, Vol. 2, University of Queensland, St. Lucia.

- Stépanoff, C. 2012. Human-animal ‘joint commitment’ in a reindeer herding system. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 2(2): 287–312.

- Taylor, W. T. T. and C. I. Barrón-Ortiz 2021. Rethinking the evidence for early horse domestication at Botai. Scientific Reports 11(1): 7440;. [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, M.D. and Bradley, D.G., 2012. The origins of cattle. Bovine genomics, pp.1-10.

- Thalmann, O. and Perri, A.R., 2018. Paleogenomic inferences of dog domestication. In Paleogenomics: genome-scale analysis of ancient DNA (pp. 273-306). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Trut, L. N. 1999. Early canid domestication: the farm-fox experiment. American Scientist 87: 160–169.

- Vigne, J.D., 2011. The origins of animal domestication and husbandry: a major change in the history of humanity and the biosphere. Comptes rendus biologies, 334(3: 171-181.

- Vishnyatsky, L. B. 1994. Running ahead of time’ in the development of Palaeolithic industries. Antiquity 68: 134−140.

- Warinner, C., Korzow Richter, K. and Collins, M.J., 2022. Paleoproteomics. Chemical reviews, 122(16): 13401-13446.

- Weinstock, J., E. Willerslev, A. Sher, W. Tong, S. Y. W. Ho, D. Rubenstein, J. Storer, J. Burns, L. Martin, C. Bravi, A. Prieto, D. Froese, E. Scott, L. Xulong and A. Cooper 2005. Evolution, systematics, and phylogeography of Pleistocene horses in the New World: a molecular perspective. PLOS Biology 3(8): e241;. [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, A. S., R. W. Wrangham and W. T. Fitch 2014. The ‘domestication syndrome’ in mammals: a unified explanation based on neural crest cell behavior and genetics. Genetics 197(3): 795–808.

- Wilkins, A. S., R. Wrangham and W. T. Fitch 2021. The neural crest/domestication syndrome hypothesis explained: reply to Johnsson, Henriksen, and Wright. Genetics 219(1): iyab098;. [CrossRef]

- Wrangham, R. W. 2009. Catching fire: how cooking made us human. Basic Books, New York.

- Zeder, M. A. 2012. The domestication of animals. Journal of Anthropological Research 68(2): 161–190.

- Zeder, M. A. 2015. Core questions in domestication research. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(11: 3191-3198.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).