1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

In right-handed individuals, language functions are predominantly localized in the left hemisphere [1]. Tumors in this region, particularly in the left frontal lobe, can disrupt language and executive functions. In this article, we describe damage to the frontal area following brain surgery using an awake technique, which resulted in the inability to describe static images compared to moving images. We coined the term “astatopsia” to better describe this syndrome. A similar effect was first described in 1917 by Riddoch in soldiers with occipital lesions, as damage to V1 (visual area 1) with conscious but incomplete perception of only movements in the blind field. This is a partially conscious phenomenon where the subject is aware of seeing movements, albeit abnormally. The mechanism of action activates extrastriate visual areas, particularly the movement areas (especially hMT/V5 - Middle temporal visual area MT or V5), through alternative pathways from the thalamus (LGN-Lateral geniculate nucleus or superior colliculus). Another case is that of human blindsight, where, however, the ability to respond to visual stimuli unconsciously is preserved after damage to V1. In this case, patients "see nothing" but are able to guess with high accuracy: the position of the object, its direction, and sometimes its color and shape. This is an unconscious phenomenon, but it demonstrates that information is still being processed. The mechanism is thought to be related to an alternative pathway: LGN to hMT+/V5 without passing through V1.We describe a right-handed female patient with left hemisphere language dominance who developed preoperative anomia and dysexecutive syndrome related to a left frontal low-grade glioma. After awake resection, she exhibited infinitive-only speech and selective visual agnosia for static images, with preserved dynamic visual recognition. This combination provides valuable insight into the localization and functional specialization of language and visual processing networks.

2. Case Presentation

A fifty-two-year-old right-handed female with left hemisphere dominance for language was diagnosed with a left frontal low-grade glioma involving the inferior and middle frontal gyri, adjacent to Broca’s area.

Preoperative Symptoms

Anomia: Difficulty naming objects, despite fluent grammatical speech

Dysexecutive syndrome: difficulty with goal-directed behaviors such as sending emails and paying for parking indicative of left dorsolateral prefrontal dysfunction

Motor, sensory, visual fields: Intact

She underwent an awake craniotomy with language and executive function monitoring; total awake procedure was performed with classical Penfield bipolar stimulation.

Postoperative Findings

Speech: Limited to infinitive verbs only (e.g., “to walk,” “to eat”), lacking syntactic and morphological complexity

Visual Recognition: unable to recognize static images of common objects such as family album pictures but preserved recognition of moving/dynamic images such as movies

Auditory and tactile naming: Preserved

Comprehension: Intact

Executive functions: Continued impairments in planning and self-directed tasks

Motor and sensory exam: No new deficits

Visual fields: Normal

Imaging

Preoperative MRI: Left inferior and middle frontal low-grade glioma

Postoperative MRI: Complete resection; subtle changes in left occipitotemporal cortex suggestive of retraction injury or small residue to be verified at long term follow-up.

All language tests, congnitive functions, attentional and menesic executive functions, praxic., visuo-spatial skills and gnosia were administered; according to the evaluation protocol used in our center. Manual hemispheric dominance was demonstrated by Edinburgh test; in the post-operative period it emerged:

-Foreign accent syndrome

- Dysprosody

-agrammatism with little use of functors (typical of broca aphasia) and prevalent communication based on the use of verbs

⁃ alessia immediately post-operatively

⁃ anomic latencies and anomalies

⁃ associative visual agnosia defined as “astatopsia”.

Our hypothesis is that the patient has difficulty finding semantic information through the visual channel and therefore uses extrastriatal pathways which become conscious at the level of successive associations probably in frontal areas.

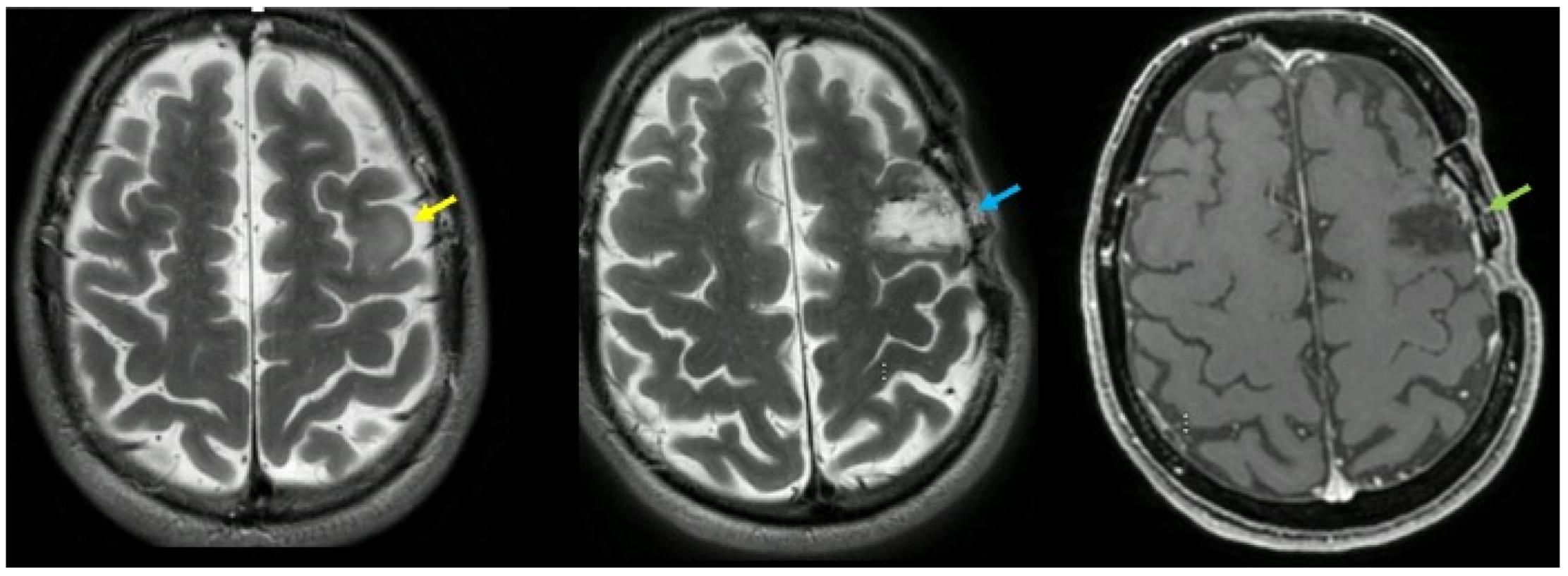

Figure 1.

Left image: Area of signal increase in T2/FLAIR affecting the middle frontal lobe at the left convexity, with a slightly swollen appearance, with blurred and irregular margins, with partial involvement of the cortex. This alteration shows no signs of diffusion restriction, does not appear hyperperfused, does not show signs of altered blood-brain barrier after IV administration of contrast agent. In the spectroscopic study conducted at this level a slight reduction in the NAA peak is observed (yellow arrow). Central image: post operative T2 image demonstrating gross total resection (blue arrow). Right image: post operative T1 image demonstrating gross total resection (green arrow).

Figure 1.

Left image: Area of signal increase in T2/FLAIR affecting the middle frontal lobe at the left convexity, with a slightly swollen appearance, with blurred and irregular margins, with partial involvement of the cortex. This alteration shows no signs of diffusion restriction, does not appear hyperperfused, does not show signs of altered blood-brain barrier after IV administration of contrast agent. In the spectroscopic study conducted at this level a slight reduction in the NAA peak is observed (yellow arrow). Central image: post operative T2 image demonstrating gross total resection (blue arrow). Right image: post operative T1 image demonstrating gross total resection (green arrow).

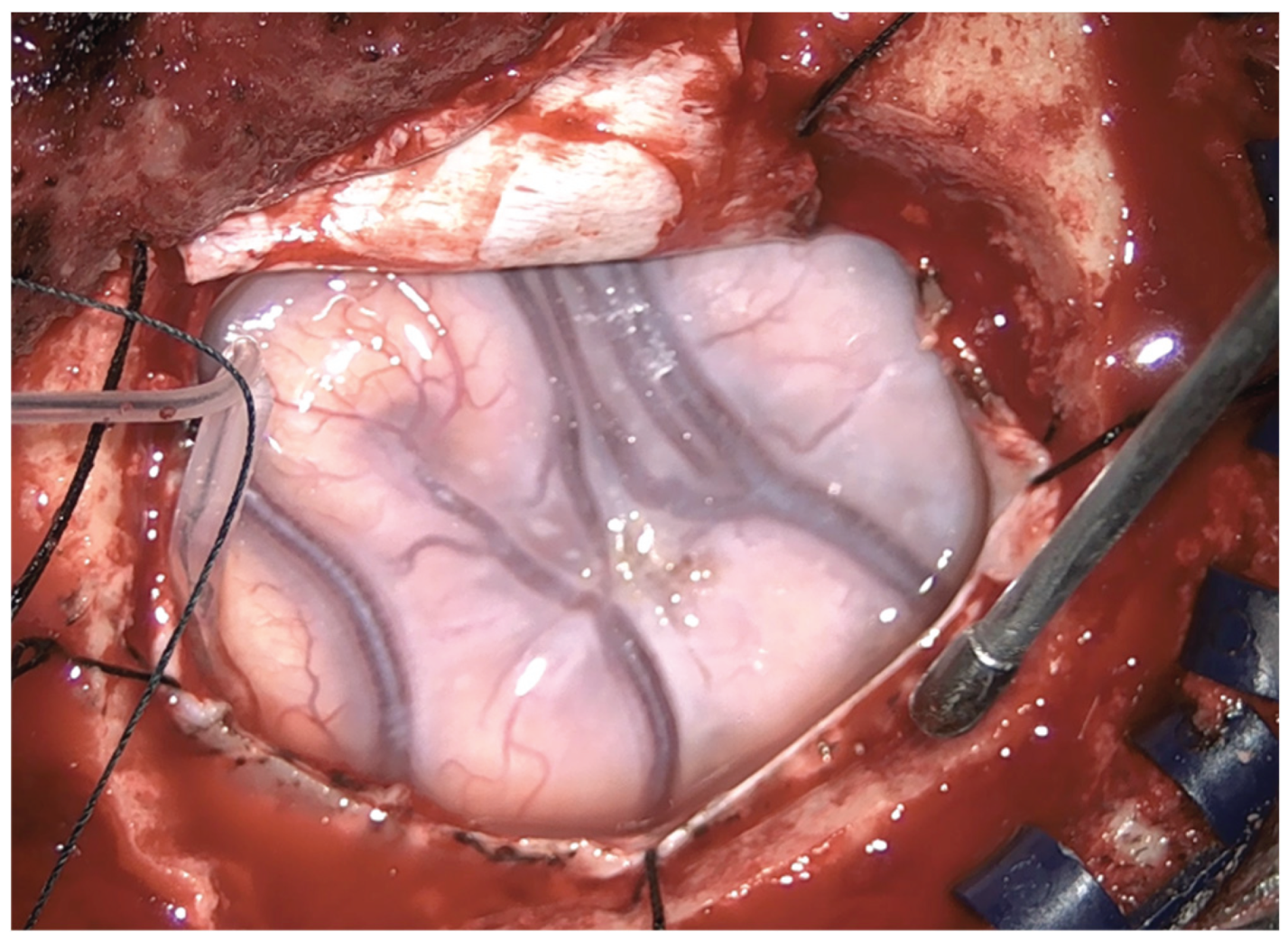

Figure 2.

Intraoperative finding: swollen appearance of the frontal lobe and bluish aspect of the glioma.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative finding: swollen appearance of the frontal lobe and bluish aspect of the glioma.

3. Discussion

This case demonstrates a rare postoperative dissociation in a left hemisphere dominant patient:

Infinitive-only speech points to disruption of left inferior frontal gyrus function, affecting morphosyntactic language production [1].

Selective static image agnosia with preserved motion perception indicates ventral stream impairment with spared dorsal stream function, consistent with the dual visual stream model [3,4]; the type of “lesion” illustrated in this case clinical is only partially described by the model.

Preoperative dysexecutive syndrome confirms involvement of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in executive control [2].

Limitations that can be set are the absence of left dominance of the patient radiologically demonstrated or by more invasive tests. We used manual lateralization tests (Oldfield, 1971 [8]) and non-invasive linguistic lateralization tests, (Kimura 1961 [9]).

The pre-operative and post-operative use of MRI with diffusion tensor study.

We also did not consider it necessary, given the absence of prosopagnosia, the absence of visuo-spatial attentional deficits and therefore the strong suspicion of left hemispheric dominance, to use neuropsychological tests to explore these functions during preoperative evaluation [10].

The converging evidence from recent neurophysiological, neuroimaging, and neuroanatomical studies [11,12,13] underscores a growing appreciation of the distributed and interactive nature of cortical and subcortical systems involved in visual perception, motor control, and higher cognitive functions. Collectively, these findings challenge classical hierarchical models that confine perception and motor planning to isolated cortical loci, instead supporting a view of the brain as a dynamic network in which frontal and extrastriate regions, as well as specialized white matter pathways, cooperate to generate conscious experience and purposeful behavior.

Within the domain of visual processing, research on the frontal eye field (FEF) and blindsight provides compelling evidence that perception emerges from reciprocal interactions between frontal and occipital structures. Activity in the FEF has been shown to correlate with perceptual awareness at remarkably short latencies, suggesting that the frontal cortex contributes directly to the formation of visual experience rather than merely reading out information from visual cortices. Complementing this, studies of patients with V1 damage reveal that residual visual abilities—commonly termed blindsight—depend critically on the structural integrity of alternative visual pathways, particularly the geniculo-hMT+ tract linking the lateral geniculate nucleus with motion-sensitive extrastriate cortex. These results indicate that visual awareness and visually guided behavior can be sustained through multiple, partially redundant neural routes, in which both frontal and subcortical-extrastriate connections play complementary roles.

Parallel advances in the study of the frontal aslant tract (FAT) extend this network-based understanding to the domain of language and executive control. The FAT, connecting the supplementary motor complex and superior frontal gyrus with the inferior frontal gyrus, has emerged as a crucial white matter scaffold supporting speech initiation, verbal fluency, inhibitory control, and other higher-order cognitive functions. Microstructural alterations in this tract are associated with a wide range of neurological and psychiatric disorders, underscoring its relevance to both clinical symptomatology and recovery potential. From a translational perspective, the identification of the FAT as an eloquent pathway has profound implications for neurosurgical planning, where its preservation is essential to minimize postoperative deficits in speech and executive function.

Taken together, these lines of research converge on a central principle: conscious perception, cognitive control, and language production are not localized to discrete cortical regions but instead emerge from the coordinated activity of distributed networks linked by critical white matter pathways. Frontal regions, long regarded as purely executive or modulatory, appear to play an intrinsic role in shaping perceptual and cognitive contents. Similarly, the preservation or restoration of structural connectivity—whether through the geniculo-hMT+ tract in blindsight or the FAT in frontal lobe functions—proves fundamental for maintaining and recovering complex behaviors following brain injury.

In sum, the integration of electrophysiological, neuroimaging, and tractographic evidence supports a unified framework in which perception, action, and cognition are mediated by dynamic interactions across cortical and subcortical systems. Future research employing causal and longitudinal methodologies will be crucial to delineate the directionality of these interactions and to translate this network-based understanding into clinical interventions that harness the brain’s intrinsic connectivity for rehabilitation and functional restoration.

The authors propose the name "astatopsia" for this peculiar syndrome described in the paper, which is not described in the literature, to the best of our knowledge.

4. Conclusions

In a right-handed patient with left hemisphere dominance, awake resection of a left frontal glioma led to infinitive-only speech and selective static image agnosia, highlighting the complex interplay between frontal language networks and ventral visual processing pathways. Preservation of motion perception supports the dual-stream model of visual cognition and emphasizes the need for careful intraoperative monitoring of both language and visual functions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.V. and A.I.; methodology, M.L., S.V. and R.T.; formal analysis, A.D.A., A.I., and S.V.; data curation, M.L., A.I., R.T. and S.V.; writing—original draft preparation, S.V. and A.I.; writing—review and editing, A.I., A.D.A. and S.V.; visualization, S.V., M.L. and R.T.; supervision, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived as the procedure was part of routine care.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank: Massimo Vissani, Nicola Giacchetta, Alessandra Marini, Roberta Benigni, from the Department of Neurosurgery in addition to Stefano Bruni, Department of Neuroradiology, and Edoardo Barboni, Department of Neurointensive care.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NAA |

N-acetylaspartate |

| V1 |

Visual area 1 |

| V5 or hMT |

Middle temporal visual area (hMT or V5) |

| LGN |

Lateral geniculate nucleus |

| FEF |

frontal eye field |

| FAT |

frontal aslant tract |

References

- Knecht S, Dräger B, Deppe M, et al. Handedness and hemispheric language dominance in healthy humans. Brain. 2000;123(12):2512–2518.

- Stuss DT, Levine B. Adult clinical neuropsychology: Lessons from studies of the frontal lobes. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:401–433.

- Goodale MA, Milner AD. Separate visual pathways for perception and action. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15(1):20–25.

- Ungerleider LG, Mishkin M. Two cortical visual systems. In: Ingle DJ, Goodale MA, Mansfield RJW, eds. Analysis of Visual Behavior. MIT Press; 1982:549–586.

- Riddoch MJ, Humphreys GW. A case of integrative visual agnosia. Brain. 1987;110(6):1431–1462.

- Gilaie-Dotan S. Visual motion serves but is not under the purview of the dorsal pathway. Neuropsychologia. 2016;89:378–392.

- Vaina LM, Lemay M, Bienfang DC, Choi AY, Nakayama K. Intact biological motion and structure from motion perception in a patient with impaired motion mechanisms. Vision Res. 1990;30(9):1281–1289.

- R.C. Oldfield, The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory, Neuropsychologia, Volume 9, Issue 1, 1971,Pages 97-113, ISSN 0028-3932. [CrossRef]

- Kimura D. Speech Lateralization In Young Children As Determined By An Auditory Test. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1963 Oct;56:899-902. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woytowicz EJ, Westlake KP, Whitall J, Sainburg RL. Handedness results from complementary hemispheric dominance, not global hemispheric dominance: evidence from mechanically coupled bilateral movements. J Neurophysiol. 2018 Aug 1;120(2):729-740. Epub 2018 May 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- La Corte E, Eldahaby D, Greco E, Aquino D, Bertolini G, Levi V, Ottenhausen M, Demichelis G, Romito LM, Acerbi F, Broggi M, Schiariti MP, Ferroli P, Bruzzone MG, Serrao G. The Frontal Aslant Tract: A Systematic Review for Neurosurgical Applications. Front Neurol. 2021 Feb 24;12:641586. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ajina S, Pestilli F, Rokem A, Kennard C, Bridge H. Human blindsight is mediated by an intact geniculo-extrastriate pathway. Elife. 2015 Oct 20;4:e08935. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Libedinsky C, Livingstone M. Role of prefrontal cortex in conscious visual perception. J Neurosci. 2011 Jan 5;31(1):64-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).