1. Introduction

The quote for this paper comes from ancient times, namely from Horacio, who in De arte poetica said: Ut iam nunc dictat, iam nunc debentia dici; pleraque differat, ac praesence in tempus omittat. This means we must say now, what should be said; other information be later, we omit it for now.

This quote implies that our perspective is closer to a white paper document written as editorial perspective than a traditional article.

1.1. Paradigm Shifts in Contemporary Economics

Pundits bring to our attention several problems facing construction today (

Table 1).

Some of the most important changes take place in information technology: Artificial Intelligence is replacing traditional modelling, 3D printing, internet of things and new types of software that impact smart buildings. Smart buildings are the focus of young and educated people, while old people have increased demands for better indoor environment and comfort. New on the list are biological considerations such as risk of biowarfare or significant changes in ventilation. Instead of dilution, that could have been achieved by opening windows, SAR-coV2 pandemics showed that we must use air filtration, which in turn requires a difference in air pressure in the dwelling.

The last item may appear as a small change, yet because the difference between the vertical position of the analyzed space and the neutral plane of air pressure affects air pressure in the dwelling, each floor must be separated from other floors. No vertical shafts or staircases connected with different floors can affect air pressure on the given floor. In other words, each building is designed as several individual floors, each containing dwellings and communication space.

Furthermore, construction of small residential houses is under economic pressure as its efficiency has not increased, while efficiency in other manufacturing in last 50 years has increased 3-fold. Yet, the single most annoying aspect of construction today is probably the growing difference between efficiency predicted and achieved in practice.

1.2. A Gap Between Energy Efficiency Intended and Achieved in Practice

A rapid change in building construction was started in the1970s, when the word sustainability was introduced in the vocabulary. Traditionally, materials and components were improved [

1,

2], and builders put them together. This process was slow. As shown in

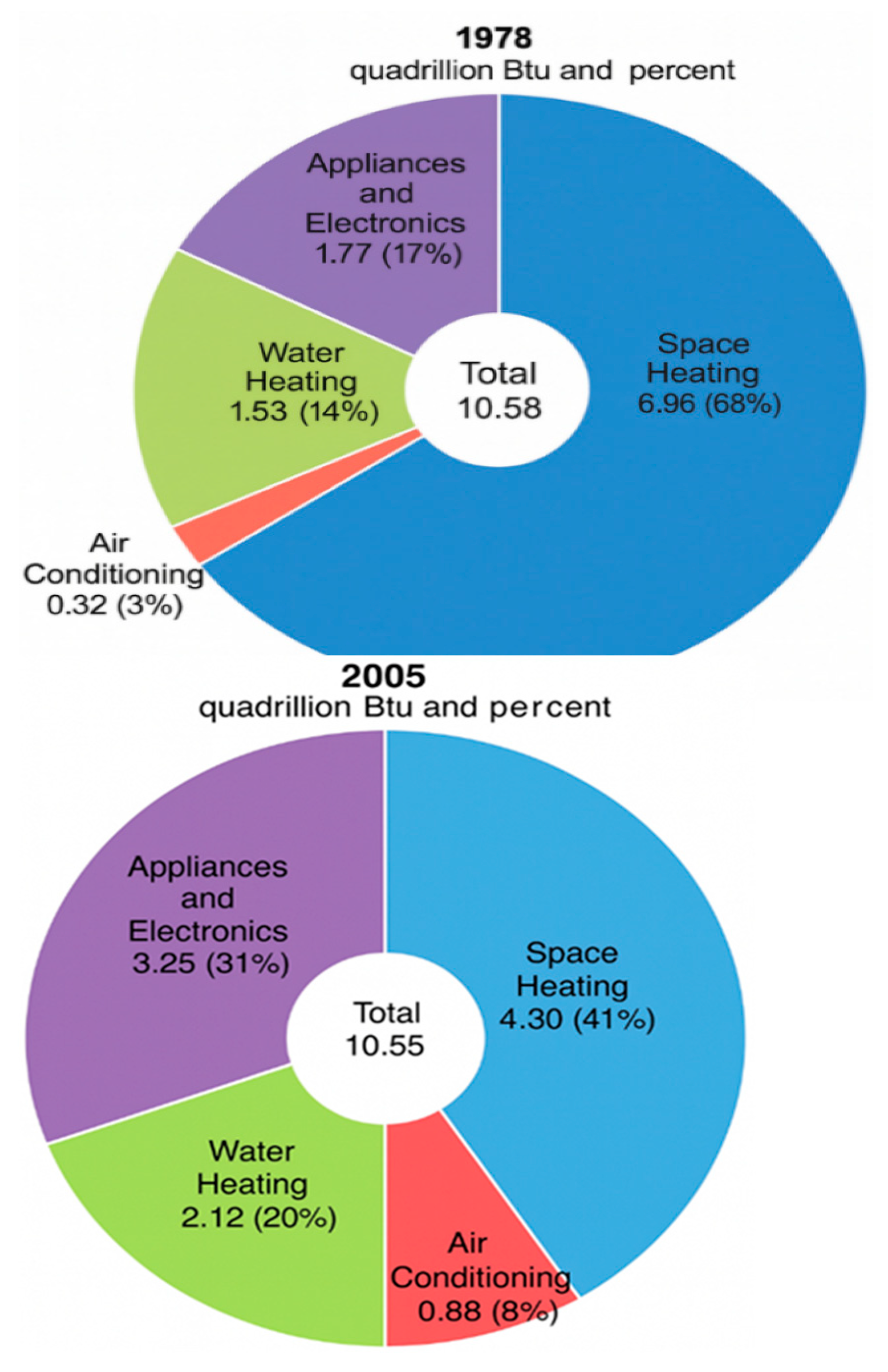

Figure 2, comparing US scenes in 1978 and 2005, when energy for space heating was reduced as an ecological measure, builders used the savings to improve occupants’ comfort, and the total energy consumption remained the same.

A report from the Building Enclosure Science and Technology (BEST) conference [

3] highlights the existence of a crossroads. While the American Institute of Architects wants a carbon-neutral future, practice shows that the savings on the space energy are used for occupants' comfort (

Figure 2), and the total energy used remains the same.

Covey [

4] in his seminal book, “7 habits of most effective people” explain that one should start with the end in mind. Still, no scientific vision of the construction process exists, because building physics was started by observation of construction practice [

1]. Furthermore, there has been and still is a gap between building science and practice. The even that made is evident was a construction in 1978 a first passive house building in province of Saskatchewan, Canada ([

5] see

Figure 1.

Covey [

4] in his seminal book, “7 habits of most effective people” explain that one should start with the end in mind. Still, no scientific vision of the construction process exists, because building physics was started by observation of construction practice [

1]. Furthermore, there has been and still is a gap between building science and practice. The even that made is evident was a construction in 1978 a first passive house building in province of Saskatchewan, Canada ([

5] see

Figure 2.

The follow-up to novel Canadian technology was a disaster. Builders liked air tightness and superinsulation but to reduce the house price, they replace expensive heating system with electrical baseboard heating. As in those new houses chimney was eliminated, the ventilation pattern was dramatically changed and caused the “sick building syndrome” (insufficient natural ventilation [

6]) as well as water vapor condensation on upper floors.

The reaction of Canadian building science community and builder association was swift. Canadian Building Code introduced mandatory mechanical ventilation for all residential buildings and a new public- private consortium was created. This consortium initiated a program called R2000 [

7], formulating building as a system and a certain number of demonstration houses were built with input of public funding to change the paradigm of thinking to” whole building thinking”.

As soon as the concepts of R2000 were showing in practice, the US instituted “Building America” program [

8] were leading consulting teams we funded 50/50 by public and private sources and like R2000 had to deliver a specified set of technical requirements. In contrast to Canadian program that was restricted to several demonstration projects per province, the American program encouraged thousands of homes to be built. Effectively, these two programs changed construction of small, residential buildings from fragmented to holistic basis.

1.3. Streamlining the Design Process: IDP (Integrated Design Protocol)

In the 1990s, the uncertainty in design objectives was reduced by a compromise. As predicting energy consumption was beyond the capability of architects and structural engineers, an energy modeling expert was added to the IDP team [

9]. At the same time, the analysis of environment in buildings was moved to a conceptual stage. This process was called a design charette, as during the French Revolution

charette, was the carriage taking the condemned to the guillotine. The IDP concept spread worldwide. Why? Is it because IDP creates a common vision of the building for the design team? Perhaps, but the real reason was economics. By placing the environmental decisions upfront, IDP reduced the cost of design.

While problems with new construction appear now to be resolved, there is still lack of vision for retrofitting, that with time became a critical problem.

1.4. The Need for Retrofitting Vision

Reviewing residential retrofitting, we saw a few cases with excellent technologies, but they were not universal. While some differences relate to the climate, most appear to come from the local traditions. We may compare construction to automobiles, and we notice that the change of thinking paradigm caused the scientific revolution [

10]. Henry Ford observed that if the car comes to the worker the outcome is better than before. The concept of assembly became universal; mass production reduced the price of model T by factor of 5 in 10 years. The second scientific revolution, so called quality revolution was based on the Japanese observation that if we do not know why people make mistakes, we should help them avoiding making mistakes rather than studying how many mistakes were made, what the western world was doing since the 1950s.

We need a vision of retrofitting. Such was also a conclusion 2010 Nanjing conference of Building Physics because climate in this region of world is humid all year round. Unfortunately, building science in America and has been stagnant for years [

1] and building physics in Europe suffered from the “green simplification” when house ventilation was replaced by opening windows. Now lessons from pandemics brought air filtration to the front of indoor environment considerations. Water, with the capacity for heat storage being four times higher than air, and must remain as the carrier of thermal energy, but air movement being involved in most of environmental considerations is the second key component of design for energy and environment.

Thus, the retrofitting vision must include integration of these two sub-systems in the process of monitoring and modelling to evaluate and improve performance of new technology for retrofitted dwellings and buildings.

There is another reason for which the academic community must publish a vision for buildings renovation, rehabilitation, thermal upgrade, modernization and many of those words used by politicians without any deeper understanding -- because in most cases their green subsidies to the marketplace are slowing technology process instead making it faster and easier. As an example, the past administration in one EU country was supporting local manufacturers of heat pumps and their clients at the same time. What they achieved was an increase of the market price of heat pumps and proliferation of the worst technical solutions e.g., so called “heat pump operated hot water tank” had 19% energy from the heat pump and 81 % of the direct electrical heater. If there was a scientifically documented vision for retrofitting, the level of political ignorance would be reduced.

1.5. Other Lessons from the Past

With progress of globalization various national research centers were either closed or required to collaborate with the local industry, dropping future-oriented work.

Table 2 lists some examples of neglected areas in the field of building environment and energy:

Code: and standards often increase confusion by ascribing requirements to specific materials. An example is a water vapor barrier (retarder), that had been requested to have permeance of 57 ng/(m

2 s Pa) or less, (one perm in Imperial Units). This was a characteristic of 19-mm thick wood plank used in traditional rural construction, an excellent benchmark for a moderate climate. Yet as range of limiting values for country like Canada is 100-fold, this is too low for cold climates and too high for moderate climates. Identical problem is with requirements of air tightness.

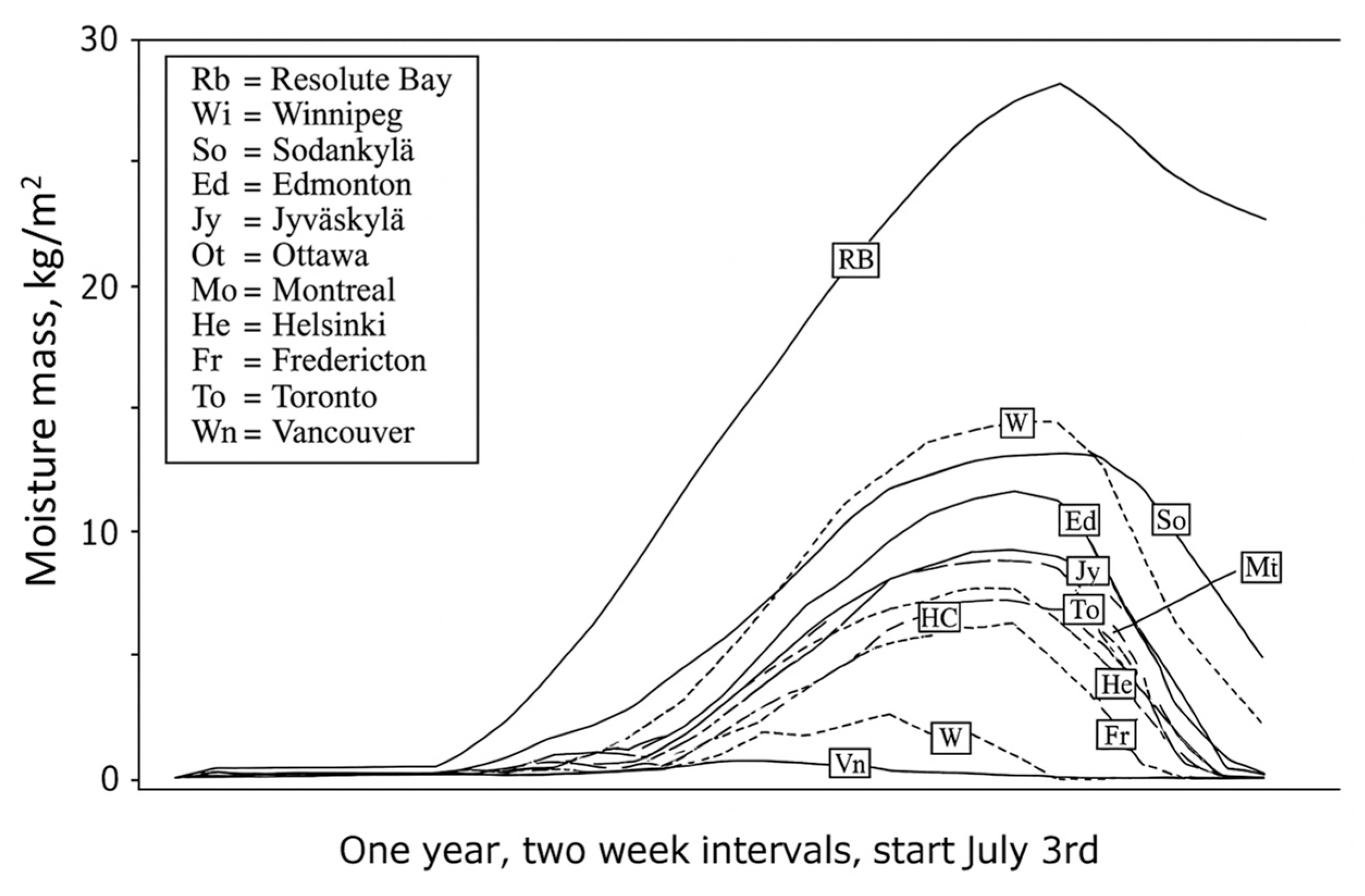

Figure 3 shows computer calculated moisture content [

11] in glass fiber insulation in wood frame houses located in different climates of Canada and Finland when indoor air with temperature 21

oC and 35 %RH enters the wall at the rate 0.9 l/(m

2s)

These two examples indicate that mandatory evaluation is needed but specification should be a benchmark and criterion referred as varying with prevailing climate instead of pass or failure criterion.

In further discussion of passive house technology, we therefore, discard all local or national criteria and use the total energy per square meter and year as the only comparable criterion.

1.6. Closure of This Review

Sustainability requires simultaneous satisfaction in three areas: ecology, economy and social relations.[

12] To ensure interaction of the first two, we propose new ecologic definition for low energy buildings, namely it is a building with surrounding ground or two buildings with ground between them. By doing so, we highlight the need for thermal storage associated with each building. We propose two types of thermal storage: (1) short term, for a minimum14 hours, obtained through a thermal mass of the building with or without water tank contribution, and a long-term, for a minimum of 168 hours (a week), obtained either through a thermally insolated volume of ground or through the usage of a water tank.

Some people or countries do not observe the need for simultaneous action on all components of sustainability. Yet, addressing ecology through sponsored actions without addressing the economic and social balance leads to unbalanced solutions and in long-term slows technological developments instead of speeding it up. Furthermore, unbalanced approaches hinder the spread of technology and thereby reduce its affordability, because automotive development showed that affordability depends on technology spread.

The boom after WWII was possible because we used traditional technology. Still, as tradition became slowly replaced by new ecological demands, no vision was created because of two factors: market fragmentation and absence of national research centers. To create vision, we need to create a socio-economic wave around a

new thinking paradigm: namely that the next generation of environmental technology will slow climate change. This is a scientific revolution [

10] that will have three beneficial aspects: ecology by slowing climate change, economy by creating many local jobs, and building occupants by creating affordable comfort.

2. Universal Technology for New Construction Has Already Been Developed in 2020

A confidential report of National Research Council of Canada (report 1639 from December 1947) provided field measurements on two one story huts. Metal pipes were placed under the whole ground floor (on a partly insulated concrete foundation), to provide hydronic heating to the building. Each hut had a 1.2 m high crawl space above the heated slab and a living space about 20 m2 square. The report presented amount of heat supplied to the building as the function of the exterior temperature and applied level of ventilation in the range between 1.5 and 4 ACH.

While this “thermo-active” system was used to establish the magnitude of heat losses in relation to climate and ventilation needs it still was an unpublished template for future developments. About 60 years later, a Hungarian inventor [

13,

14], used a hydronic heat exchanger in the additional concrete slab located some distance under the building. The geothermal hydronic heat exchanger in Hungary, did not provide enough energy and a heat pump was added to the ventilation system. At the same time a PhD student in Syracuse University [

15], built a heat exchanger circulating air in walls, using a split-level heat pump operating on a geothermal water tank located underground.

About the same time, a team of motivated people in the city of Montreal, Canada, realizing that success requires addressing many design details, developed integration though a stepwise construction [

5]. During the span of 10 years they reduced the 90 percent energy use, as postulated by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL, see [

3]).

The need for universal technology that was made clear during a Westen-Chinese building science conference 2010 in Nanjing. At this time, thermal mass in wood frame home was studied by Mattock [

16], a demonstration home was built and operated in Hungary (Kisilewicz et al. [

13,

14]), test building operated in Syracuse (Lingo and Roy [

15]), and the multi-stage residential district was built in Montreal. All these are steps towards technological revolution.

To understand the pattern of technological revolution (presented by Kuhn [

10] as scientific revolution) we review history of automobiles. Henry Ford observed that if the car comes to the worker, the outcome is better than for if worker is going to the car. The concept of assembly resulted in mass production and reduced the price of model T by factor of 5. The second event in car manufacturing, so called quality revolution, involved a change of thinking paradigm, also. Japanese observed that if one cannot establish why people make mistakes, one needs to help workers avoiding making mistakes. We call it quality assurance, and it replaced the quality control that manufacturers have been doing before.

A team of motivated people in Montreal, Canada also started a technological revolution in construction industry. The old paradigm was the need to fund the whole process of construction from building foundation until giving keys to occupants. The new thinking paradigm was the building must satisfy the code requirement, and this is a stage one of construction. All improvements can be considered as renovation (retrofitting), and all additional work is what one calls in economics “value added”, and this process that can be funded (mortgaged) based on its current value. Using this change of paradigm, they obtained funding for 10 years of multi-stage construction. In this process they reduced 90 % energy use. Atelier Rosemount in Montreal, Canada had some luxury apartments with south and north exposures to enable cross ventilation, and neighbors living in social dwellings with the cost of a fraction of the luxurious dwelling but the same comfort of live. This project broke barriers between new buildings and retrofitting and barrier of affordability. The financing concept introduced by the paradigm change was a few short term-loans, each for a new stage of construction.

Figure 4.

An affordable, low-rise, energy-efficient multi-unit residential building “Atelier Rosemount” in Montreal, rain retention basin in the bottom right (credit Nikkol Rot [5]).

Figure 4.

An affordable, low-rise, energy-efficient multi-unit residential building “Atelier Rosemount” in Montreal, rain retention basin in the bottom right (credit Nikkol Rot [5]).

The retrofitting included the following steps:

High performance enclosure; common water loop; solar panels resulting in 36% reduction.

Gray water, the passive measures of energy reduction give 42%.

Heat pump heating—all passive measures give a 60% reduction.

Domestic hot water with evacuated solar panels, a further 14%.

Photovoltaic panels reduce the total energy to a total of 92% reduction.

While investors may want to stop at the requirements of codes and standards, society needs a higher level of investment, at least near zero carbon emission. Either a builder or house owner who applies for a mortgage faces two critical issues: (a) the value of the existing property versus surrounding properties, and (b) an estimated cost of repairs. Having a cost estimate from stage 1 is invaluable when proceeding to the next stage. Therefore, we propose a two-stage construction process that alleviates conflict between investors and society.

The final step to complete the technological revolution came in ASHRE (American Society for Heating and Refrigeration Engineers) 2020 competition for sustainable technology as the 1

st place award. It was a building in Tokyo, Japan, with integrated hydronic, heat pump based radiant heating/ cooling and ventilation called thermo-active system [

17].

Thus, our team, aggregating the first series of network publications [

18,

19,

20] and second series called EQM parts 1 to 4 [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Atelier Rosemont, Montreal, Canada [

5], Hungarian inventor work [

13,

14]; Tokyo design [

17], older work in Vancouver [

16], Syracuse University [

15], NY, USA, and the American LNBL [

3] that quantified requirements for sustainable construction and retrofitting, was justified to state:

A foundation for universal technology of sustainable buildings with near zero energy and near zero carbon-emission has already been established in 2020.

Despite this statement, neither multi-stage nor thermo-active (TA) technology became widely used. It became evident that current linkage between academic work on energy and indoor environment and construction practice is too weak to impact the marketplace in any developed country.

3. Creating Passive and Thermo-Active (PTAC) Universal, Retrofitting Technology

At BEST 1 conference (2008), we created a small, virtual team of engineers to address the challenge of integrating heat, air and water transfers with

monitoring and (field) performance evaluation (MAPE). Realizing that passive house methodology reached the economic stage of maturity, we added

an energy supply method [

15,

16] to the passive house [

25,

26], and named this technology

Passive and Thermo-Active Cluster (PTAC). PTAC permits achieving between 50 and 70% reductions for retrofitting of existing buildings, and 90 percent reduction for new construction, i.e., satisfying 2008 requirements of LBNL [

3]. This technology can be a first step in technological revolution linking construction with slowing climate change. For more details look to Retrofit: building energy and environment engineering, a book by Bomberg, Saber and Yarbrough” expected in November 2025 [

27]. The first step to slowing climate change is to reduce the cost of decarbonization.

3.1. Reducing the Cost of Decarbonization

Torrie and Bak [

28] writing about Canada, highlighted that despite ten million single-family homes and five million apartments with a floor area of 2.1 billion square meters and 65 million tons of carbon emissions per year, where about two-thirds use natural gas, Canada has no pathway to a low-carbon future. Today most small houses are built piece by piece, like Ford in 1910 with a price in today dollars about US

$ 25,000 and the company sold 19,000 cars in that year. Ten years later, with online manufacturing experience, the cost of Model T went down to US

$ 5,000 and Ford sold 941,000 vehicles.

In 2019 Canadians spent more than $60 billion yearly renovating their homes and $30 billion on space heating. A typical deep retrofit with heat pump conversion for a single-family house is at least $40,000. Calculating a 10-year transition to a low energy level with a yearly average of $36.7 billion per year, i.e., a carbon emission cost of $141 per ton (about US$ 100,00). If one assumes that a new technology reduces the price by 30% with 30 % increase in carbon efficiency increases and the volume of retrofitting grows 3 folded the cost of one ton of emissions goes down below $10 per ton of emissions.

In effect we need to increase the efficiency of PTAK technology by 1/3 while keeping the same cost and increase the volume of retrofitting to reduce the cost of 1 ton CO2 by factor of 10. This objective addresses the objective of slowing rate of climate change by retrofitting old buildings.

Thus, a scientific revolution in construction will provide a win-win solution for society, economy, and the building’s occupants. Society wins with slowing climate change, the economy with plenty of local jobs, and occupants with affordable, excellent indoor environments. As builders do only what society wants them to do, the society must demand buildings to have zero carbon emissions and occupants to have a higher comfort of living.

3.2. Benefits of PTAC Technology

PTAC technology [

24,

29] extends the passive house methodology with the use of:

Ecological definition for low-energy building cluster in new or retrofit construction is as follows: for a low-rise (1 to 3 stories incl.) is 70 kWh/(m2 a) and for a mid-rise (4 to 11 stories incl.) is 100 kWh/(m2 a)

The two-stage (or multi-stage) construction process is used to modify the pattern of financing.

A short-term thermal storage (14 -16 hours) to reduce daily variation of the loads in the electric grid, and a long-term (168 hours) thermal storage to reduce seasonal climatic extremes of hot week in summer or freezing cold week in winter

Building automatics to control contribution of thermal mass and additional water thermal storage linked water-sourced heat pumps and for new construction also with solar panels [

30].

Adaptable indoor climate achieved with HVAC integrated with the building structure [

31]

A monitoring and performance evaluation (MAPE) system to optimize energy and indoor environment during operation of the building.

Climatic District Network (CDN) to connect the Passive and Thermo-Active Cluster (PTAC) building to the next building or to apply in series of buildings in a city district.

The word cluster in the above definition means a cluster of passive and thermo-active methods and a cluster of buildings (in the extreme case it is one building with the surrounding ground). Steven Covey in “7 Habits of the Most Efficient People” [

4] highlighted that any project should start with the definition of the required outcome. To achieve a balance between often contradictory requirements of energy efficiency, occupant comfort, high quality of the indoor environment and cost of the project one uses Integrated Design Protocol” (IDP [

9]). IDP created a common vision for design based on the whole-building approach, reduced the cost of the design itself and shifted the design paradigm to building as a system. The design of the whole building, with primary requirements for components and assemblies, implied material selection at a later stage has empowered polymeric industry to create new multi-functional materials. [

21]

Montreal project [

5] showed how much energy can be reduced by different actions. In the first step, high level of thermal insulation and air tightness, reduced energy consumption by about 40%. An air-sourced heat pump was added to the passive measures in New York State, and energy reduction reached 55% (see construction process [

32], and quality assurance [

33]). A Ph.D. that reviewed co-simulation as an improvement for energy modeling) [

34,

35], showed the limit of passive measures with an effective heat pump application at 60%. To reach more than 60% one needs to use additional measures, e.g., geo-solar engineering [

2,

24] or a modification of the energy supply system. The latter is postulated in the PTAC technology for retrofitting.

Experience from California supports ventilation with variable rate and consideration of microbiological pollution requires air filtration. The ventilation system in PTAC technology uses air gaps created between existing walls and a new heating/cooling system. As we said in the introduction in this paper we propose only a template for different options. It is for a designer to select the water tank capacity, power of the WSHP that operate in the night only, or extend hours of WSHP operation, use one- or two-step water buffer system, and means to ensure the minimum temperature of the low HP terminal. If the supply system is too expensive, designer may increase the level of thermal insulation or introduce phase change / reflective surfaces in the heating /cooling panels. One may also increase the area of retrofitting by using all interior partitions.

3.3. Providing Energy to the Lower Terminal of WSHP

In retrofitting one may consider controlling the temperature of the lower terminal of WSHP to increase the coefficient of performance (COP) for water-sourced heat pump (WSHP). Furthermore, about 1/3 of thermal energy in shower water can easily be recovered if we include the gray water into the system. Thus, in PTAC technology we use water-water heat pump with two water tanks and independent water pump to separate water heating/ cooling from the space air conditioning.

Heat pumps are the preferred choice because of the energy multiplication effect. Yet, there are different types of heat pumps and efficient use of the new technology requires using a water-sourced heat pump, together with two water tanks to provide a thermal storage (heat capacity). A heating coil is inserted in the water tank delivering hot water to floor and wall heat exchangers. The water tanks are called: (1) Domestic Hot Water (DHW) tank, and (2) cold water tank (CWT), The latter tank functions as a lower terminal of the heat pump.

Water-source heat pumps (WSHP) typically have performance coefficient higher than air-sourced heat pumps. Yet switching to a water-sourced system brings a new consideration about the lower temperature limit. For instance, when temperature in cold water tank falls below a specified limit, e.g., 10 C, an electric heater starts adding energy to the water. Yet, electric heating has an apparent coefficient of performance (COP) of one, while WSHP has typically COP higher than 4. It makes sense to use hot water instead of electrical heating to add thermal energy to the cold-water tank. Other benefits of WSHP are: increase of heating or cooling efficiency, presence of hot and cold water though whole year, easy integration of hybrid solar panels or gray water, and district climatic network

3.4. An Invention of a District Climatic System to Replace the District Heating

This PTAC technology introduces an innovation in

the climatic district network (CDN) that may also be applied to historic buildings by pairing them with an adjacent standard building. In this manner, the pair of buildings are included in a local district heating/ cooling system. District heating, cooling, and ventilation systems eliminate the difference between a single building or district of the city. As PTAC technology includes thermal storage and water tanks may be located underground [

22,

36], the district climatic system may either be a part of the building or the energy distributing system. The summary of the research on air-earth heat exchangers [

22] implies 1 m depth in Central Europe. If a low-density, (about 10 kg/m

3), polyurethane foam fills this line, the foam will be a dry insulation in winter and wet in summer, heat conductor in summer (gradient inwards) and as such it will dissipate heat better than dry.

4. Discussion: Public-Private Demonstration Projects Are the Key to Success

In summary, sending return water, together with preconditioned air, to the next building may reduce operational costs by increasing COP over that of the heat pump alone. Furthermore, as construction of settlements is less expensive than that of separate buildings, adding a climatic district system increases the investment efficiency, and would diminish the difference between separate buildings and city districts. This paper explains the need for scientific revolution in retrofitting technology and poses the critical question: can we build consortia capable of initiating the social wave for retrofitting with a view to slowing climate change?

The backbone of the PTAC technology is the Modeling and Performance Evaluation (MAPE) [

23,

24] where field modelling provides calibration for numeric or neuron network models that in turn can be used for building automatics control systems. A review of different Artificial Neural Network (ANN) applications was performed in a separate work environment [

37,

38,

39] and complemented with examination of globalized application of Artificial Intelligence [

40] to establish if Ai can be used for multi-variant, gray system analysis. These works indicate that AI combined with monitoring air tightness and solar contributions may be combined with electricity bills as means of field performance control. Given adequate scope of hourly monitoring, AI may complement or replace use of numerical modeling.

…Productivity and well-being of the occupants are the main criteria while energy is not easy to observe. If we stress only one aspect out of many, we give the impression of unbalanced technology. Medows [

41] said that grants, tax reductions, and sponsorships do not have impact on sustainable built environments while the highest social value like climate change has large impact. Why are we not using it?

The answer is simple; the global market is nobody’s market. We have managed to break society’s values in quest for money and today we must create different ways of rebuilding local socio-economic values. Observe that in a Building Physics group of Montreal University no one knew about the Rosemount project. Without the involvement of the academic group the society did not know either and no one championed the benefits of the project. One could talk about the poor qualifications of these people who want to introduce ecological construction but have no idea how to create a “market pull”. It is no money giveaway but serious work to educate builders by workshops, presentations and professional organizations. Years ago, we had all these tools but because of progressive elimination of systematic technology transfer and because of funding academic projects without the follow up to marketplace, in many countries we have lost the relation of academic to industrial world.

The epidemics deleted the old order, sponsoring products on the market does not create market forces. Tools alone, even as sophisticated as AI, are only tools, used like hammer to drive nails. Unless the use of technology is synchronized with the social awareness of ways to slow climate change, the latter will never be achieved in practice. In closure, we repeat any technology is one leg only, to walk one needs two and the second leg is a public education. This is needed for public change of thinking paradigm and public-private national demonstration projects are the best way to educate public. An immediate solution should be to use the sponsoring money to build the missing link to allow society to use the next generation technology.

missing link to allow society to use the next generation technology.

5. Elements of Future Research and Demonstration Projects

This paper provides the vision of the next generation technology and states that in the fragmented field of construction, research alone will not suffice to create technological revolution. As much as we need it, and despite of documentation for each of the proposed technology elements given the lack of national research centers, one sided and unbalanced actions of ecological sponsorships by many countries the only way to rectify the situation is to create a public-private consortium to initiate a public education in the next generation of buildings and demonstrate the potential of retrofitting to slow climate change.

5.1. Some Critical Issues in the Next Generation of Technology

Below we propose a scope of future activities

The starting point for designing buildings is to have a well-established reference cost for the low energy reference buildings. We that reference buildings in a low-rise (1 to 3 stories incl) have no more than 70 kWh/(m2a) and for a mid-rise 4-11 stories the level is 100 kWh/(m2a).

The second most important area of consideration is monitoring components of MAPE, and specially separation between energy carried by air flow and by conduction through the building enclosure. The latter also addresses the contribution of solar energy, or it lack. Initial work must therefore include (a) temperature difference on west and north sides of the building, (b) air pressure difference between indoor and outdoor environment on two opposite sides of the building, and (c) air pressure difference between the monitored dwelling and dwelling at the neutral pressure plane [

37].

The role of air pressure differences will be better understood in context of broad research on control of air flows (energy, durability, IAQ).

PTAC technology is for interior applications, yet. if the building does not have sufficient thermal insulation and the exterior layer cannot be added, one may add a layer of thermal insulation on the interior, but such an action increases the effect of thermal bridges in the assembly, and this issue must be resolved

The second item in MAPE is modelling and one needs to switch to hourly data collection for the sake of precision in dynamic weather changes, still, there are three critical issues in modeling:

5.1. Developing calibrated either numeric or artificial neural network (ANN)models to predict hourly changes of energy considering three components: (a) conductive heat losses/gains. (b) energy needs to modify outdoor air temperature, (c) solar gains (if any)

5.2. Developing building characterization to introduce to calibrated ANN models to predict hourly changes of energy and compare their precision with numerical models [

42,

43]

5.3. Linking the hourly level of energy use with the external weather data and model calculation of energy use.

1. The third element in MAPE is improving effectiveness of heating and cooling for a given building on the basis one year monitoring data collection. To this end one must design the system with capability occupant to tailor own indoor climate and for fine-tuning by experts, develop models describing measured data and introduce needed actions. After the improvement one must verify agreement with predictions as defined in section 5.

7. The provision of automatic heating the cold water in lower WSHP terminal requires careful examination and design of the whole independent system.

8. The intake of ventilation air from an exterior wall should be designed in such a way that air is protected from ingress of insects and preheated when passing along the exterior wall before entering the stratified ventilation system with a 2.5-micron filter and periodic action to create hybrid ventilation.

9.The exhaust of ventilation can be from the bathroom, because kitchen may have an independent exhaust above the stove.

10. The ventilation system may or may not be used to dry old masonry walls. If so, before entering the dwelling there should also be an air dehumidifier.

11. Drying of walls will be better understood in context of broad research on humidity and moisture management (durability, IAQ) in retrofitting technology [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49].

12.The complexity of PTAC functions would be better understood if one separates the whole system into a few sub-systems, namely:

12.1 Heating and cooling sub system that includes water sourced heat pump (WSHP), cold water tank (CWT) and a device periodically (on demand) transferring domestic hot water to the CWT

12.2 DHT (domestic hot water tank) with supply of tap water and automatic set-up of heating and cooling.

12.3. Heat exchangers located in walls, floors or ceiling either made continuously in-situ or mounted in panels with snap-on connections [

50]

12.4 Automatic distribution system with water pumps online to HDH and heat exchangers

12.5 Software operating the energy and ventilation distribution systems

13. Establishing holistic and balanced approach [

51] to retrofitting for teaching building physics

14. Establishing a few typical system schematic drawings for teaching building physics

5.2. Modeling of Energy and Environmental Issues

Despite large amount of money spent on numerical modeling to eliminate the predictability gap, the gap in energy prediction is substantial. Particularly large is for the high-rise, because a prediction of interstitial airflows caused by air buoyancy is not available, neither the local effects of solar radiation. As rapid development of air flow and local solar radiation characterization is not probable the future of predictable energy modeling moves towards gray models of artificial neural networks (ANN), including AI.

To ensure that ANN modeling may replace different types of numerical models, we examined a globalized ANN application for 507 buildings with different climates on 3 continents (to be published in the coming special issue of MDPI’s Journal of Energies). The precision of the globalized network was low, but in those applications where similar buildings are used precision is high. As ANN models work with partial characterization by means of air pressure or temperature differences, we postulate the following:

One should use one-hour steps for monitoring all performance data including air pressure difference across the building enclosure and between the analyzed dwelling and the reference point and temperature difference between solar exposed and non-exposed parts

One should establish a correlation of predicted and measured data to assess probability of using ANN and AI instead of numerical models

Author Contributions

All authors have equal contributions except for Mark Bomberg, who wrote the text and Anna Romanska-Zapala, who led all work on Automatics and ANN/AI applications.

Funding

There was no funding for this research.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this study, we used existing published data (see text).

Acknowledgments

This paper on science and practice of residential building technology was started about 20 years ago with sponsorship of two US government levels, to show potential for energy reduction before applying renewable energy. The result was 50% reduction. NY state, however, would only support renewables and we continued as a virtual network, changing contributors over time. Three of us were there for the whole period of 20 years. In addition to guest editors of this Special Issues of Energies Prof. David Yarbrough was the third contributor though the whole time. We want to acknowledge contributions from Cracow Technical University on neural networks and pre-conditioning of ventilation air, as well as collaboration with the US passive house institute [21,22], Tech. University of Quebec [23,24] and Southeast University in China [25].

Conflicts of Interest

There were no conflicting interests.

References

- Bomberg M, Romanska-Zapala A., and Yarbrough, D W, 2020, History of American Building Science: steps leading to scientific revolution, J of Energies, 13, 5, p.1027.

- Bomberg, Mark, Anna Romanska-Zapala, and David Yarbrough Towards a new paradigm for building science (bldg physics), World 2021, 2(2), 194-215. [CrossRef]

- Bomberg, M.; Onysko, D. (Eds.) Energy Efficiency and Durability of Buildings at the Crossroads, 2008. http://thebestconference.org/BEST1 (accessed on 25 February 2020).

- Covey S.R., The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, Simon, and Shuster,1989, pp. 95-182.

- Rosemount Atelier in Montreal. Information Notes; Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation: Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 2016.

- US Environmental Protection Agency, Indoor Air Facts, number 4, Sick Building Syndrome, February 1991, accessed Sept 20, 2025.

- R2000 standard for energy efficiency. https://: natural rsources.ca/edu.ca/energy efficiency/home energy effuicencyr2000-standrds-buildings, accessed Sept 20, 2025.

- Building America Program. https://: www.energy.gov/eere/buildings/building america, accessed Sept 20, 2025.

- IDP, An Integrated Approach to Design of Protocol Specifications Using Protocol Validation and Synthesis, IEEE Transactions on Computers, Apr. 1991, pp. 459-467, 40. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolution; The Chicago U. Press: IL, USA, 1970, see also The Fourth Industrial Revolution | Essay by Klaus Schwab | Britannica, accessed dec17,2023.

- Kumaran MK and Tuomo Ojnannen, 1996, Effect of exfiltration on the hygrothermal behaviour of a residential wall assembly, J. of Building Physics, p.215-227.

- Mark Bomberg, Mark, Tomasz Kisilewicz, Christopher Mattock, 2015, Methods of Building Physics, ISBN: 978-83-7242-886-8, 2015, Published Cracow Polytechnics, in English, p. 1- 368 see text on the web.

- Kisilewicz, T.; Fedorczak-Cisak, M.; Barkanyi, T. Active thermal insulation as an element limiting heat loss through external walls. Energy Build. 2019, 205.

- 2023; 14. Kisilewicz Tomasz, Małgorzata Fedorczak-Cisak, Beata Sadowska, Irena Ickiewicz, Tamas Barkanyi, Mark Bomberg, Ewa Gobcewicz, On the results of long-term winter testing of active thermal insulation Energy & Buildings, 296, Oct 2023, 113412.

- Lingo L. Jr.; Roy, U. Novel Use of Geo solar Exergy and Storage Technology in Existing Housing Applications: Conceptual Study. J. Energy Eng. 2016, 143, 0401602.

- Mattock, C. Harmony house Equilibrium project. In Proceedings of the Canada Green Building Council, Annual Conference Vancouver, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–10 June 2010.

- Kosuke Sato, Eri Kataoka; Susumu Horikawa, Thermo-Active Building System Creates Comfort, Energy Efficiency, J, ASHRAE, March 2020,62(3), p42-50, ASHRAE.org.

- Bomberg M, Gibson M, and Zhang J, 2015, A concept of integrated environmental approach for building upgrades and new construction: Pt 1—setting the stage, J. of Building Physics, 2015, Vol. 38(4) 360–385.

- Bomberg, M.; Wojcik, R.; Piotrowski, Z, 2016a, A concept of integrated environmental approach, part 2: Integrated approach to rehabilitation. J. Build. Phys, 39, 482–502.

- Thorsell, T.; Bomberg, M. Integrated methodology for evaluation of energy performance of the building enclosures. P3: Uncertainty in thermal measurements, J. Build. Phys. 2011, 35, 83–96.

- Bomberg, M.; Yarbrough, D.; Furtak, M. Buildings with environmental quality management (EQM), part 1: Designing multi-functional construction mat.. J. Build. Phys. 2017, 41, 193–208.

- Romanska-Zapala, A.; Bomberg, M.; Fedorczak-Cisak, M.; Furtak, M.; Yarbrough, D.; Dechnik, M. Buildings with Environmental Quality Management (EQM), part 2: Integration of hydronic heating/cooling with thermal mass. J. Build. Phys. 2018, 41, 397–417.

- Yarbrough W, M. Bomberg, A. Romanska-Zapala, Buildings with Environmental Quality Management (EQM), part 3: From log houses to zero-energy buildings, J. Build. Phys. 2018, 43.

- Romanska-Zapala, A., Bomberg M., Yarbrough D., 2018, Buildings with Environmental Quality Management (EQM), part 4: A path to the future NZEB. J. Build. Phys., 43, 3–21.

- Klingenberg, Katrin Mike Kernagis, and Mary James, Homes for a Changing Climate: Passive Houses in the U.S. Paperback – January 1, 2009, order through the internet.

- Wright, G.; Klingenberg, K. 2015, Climate-Specific Passive Building Standards; U.S. Department of Energy, Building America, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Report,.

- Bomberg M, A. Romanska-Zaoala, H. Saber, Passive and Thermo-Active Cluster Technology for residential buildings to slow climate change, submitted to Energies, MDPI.

- Torrie Ralph and Céline Bak, 2022, Building Back Better with a green renovation wave, (Planning for a green recovery), internet newsletter, April 22, 2022 (own archives).

- Fedorczak-Cisak, M.; Bomberg, M.; Yarbrough, D.W.; Lingo, L.E.; Romanska-Zapala, A. Position Paper Introducing a Sustainable, Universal Approach to Retrofitting Res. Bldgs. Buildings 2022, 12(6), 46;

- Dudek, P.; Górny M, Czarniecka L, Romanska-Zapała, A. IT system for supporting the decision-making process in integrated control systems for energy efficient buildings. In Proceedings of the 5th Anniversary of World Multidisciplinary Civil Engineering-Architecture-Urban Planning Symposium—WMCAUS 2020, Prague, Czech Republic, 31 August 2020.

- De Deer, R.; Zhang, F. Dynamic environnent, adaptive comfort, and cognitive performance. In Proceedings of the 7th International Building Physics Conference, IBPC2018, Syracuse, NY, USA, 23–26 September 2018; pp. 1–6.

- Brennan, T.; Henderson, H.; Stack, K.; Bomberg, M. Quality Assurance and Commissioning Process in High Environmental Performance (HEP) Demonstration House in NY State. 2008. online: www.thebestconference.org/best1 (accessed on 12 October 2019).

- Walburger, A.; Brennan, T.; Bomberg, M.; Henderson, H. Energy Prediction and Monitoring in a High-Performance Syracuse House. 2010. Available online: http://thebestconference.org/BEST2 (accessed on 2 October 2019).

- Heibati, RS, W Maref, HH Saber, Assessing the Energy and Indoor Air Quality Performance for a Three-Story Building Using an Integrated Model, Part 1: The Need for Integration, Energies 12 (24), 4775, 2019,.

- Heibati, Reza S, Wahid Maref, Hamed H. Saber, Assessing Energy, Indoor Air Quality, and Moisture Performance for a Three-Story Building Using an Integrated Model, Part Three: Development of Integrated Model and Applications, Energies, 2021, 14(18), p. 5648,.

- Romańska-Zapała, A., M. Furtak, M. Fedorczak-Cisak, M. Dechnik, The Need for Automatic Bypass Control to Improve the Energy Efficiency of a Building Through the Cooperation of a Horizontal Ground Heat Exchanger with a Ventilation Unit During Transitional Seasons: A Case Study”, WMCAUS 2018, Prague IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Eng., vol. 246.

- Bomberg, M.; Kisilewicz, T.; Nowak, K., 2016, Is there an optimum range of airtightness for a building? J. Build. Phys., 39, 395–420.

- Dudzik, M.; Romanska-Zapala, A.; Bomberg, M. A neural network for monitoring and characterization of buildings with Environmental Quality Management, Part 1: Verification under steady state conditions. Energies 2020, 13, 3469.

- Dudzik, M. Toward characterization of indoor environment in smart buildings; Part 1: Using the Predicted Mean Vote criterion. Sustainability 220, 12, 6749.

- 40. Romanska-Zapala next paper.

- Meadows Donella, the limits of growth, The Donella Meadows project, Academy of System Change, on the internet; see also “Meadows on social paradigms Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens III, W.W. The Limits to Growth; Universe Books: NY, NY, USA, 1972.

- Buratti, C, M. Vergoni, D. Palladino, Thermal comfort evaluation within non-residential environments: development of Artificial Neural Network by using the adaptive approach data, 6th Int. Building Physics Conf., IBPC 2015, Energy Procedia, 2015, 78, p. 2875 –2880.

- Ferreira, Pedro & Silva, Sergio & Ruano, Antonio & Negrier, Aldric & Conceição, Eusébio, 2012, Neura Network PMV Estimation for Model-Based Predictive Control of HVAC Systems, WCCI 2012 IEEE World Congress on Comp. Intelligence, June 10-15, 2012, Brisbane, Australia 15-22,.

- Bomberg, M. A concept of capillary active, dynamic integrated with heating, cooling and ventilation, air conditioning system. Front. Archit. Civ. Eng. China 2010, 4, 431–437.

- Bomberg M and Pazera M, 2010, Methods to check reliability of material characteristics for use of models in real time hygrothermal analysis. In: Res. in Building Physics—Proc.1st Central Eur. Symp. Building Physics (eds Gawin and Kisielewicz), Cracow–Lodz, Poland, 13–15 September 2010, pp. 89–107.

- Häupl means of a capillary active interior insulation. In Proceedings of the Building Physics in the Nordic Countries, Gothenburg, Sweden, 24–26 August 1999; pp. 225–232, P.; Grunewald, J.; Fechner, H. Moisture behavior of a “Gründerzeit” -house by.

- Simonson, C.J.; Salonvaara, M.; Ojanen, T, 2004, Heat and mass transfer between indoor air and a permeable and hygroscopic building envelope: P. II, Verification, and numerical studies. J. Bldg. Phys. 2004, 28, 161–185.

- Vereecken E, Roels S. 2015. Capillary active interior insulation: do the advantages really offset potential disadvantages? Materials and Structures, 2015,48(9): 3009-3021.

- Fort J, Kocí J, Pokorný, Podolka L, Kraus M and Cerný R, Characterization of Responsive Plasters for Passive Moisture and Temperature Control Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 9116. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Shi, X.; Bomberg, M. Radiant heating/cooling on interior walls for thermal upgrade of existing residential buildings in China. In Proceedings of the In-Build Conference, Cracow TU, Cracow, Poland, 17 July 2013, p314.

- Fadiejev, J.; Simonson, R.; Kurnitski, J.; Bomberg, M. Thermal mass, and energy recovery utilization for peak load reduction. Energy Procedia, 2017, 132, 38.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).