Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

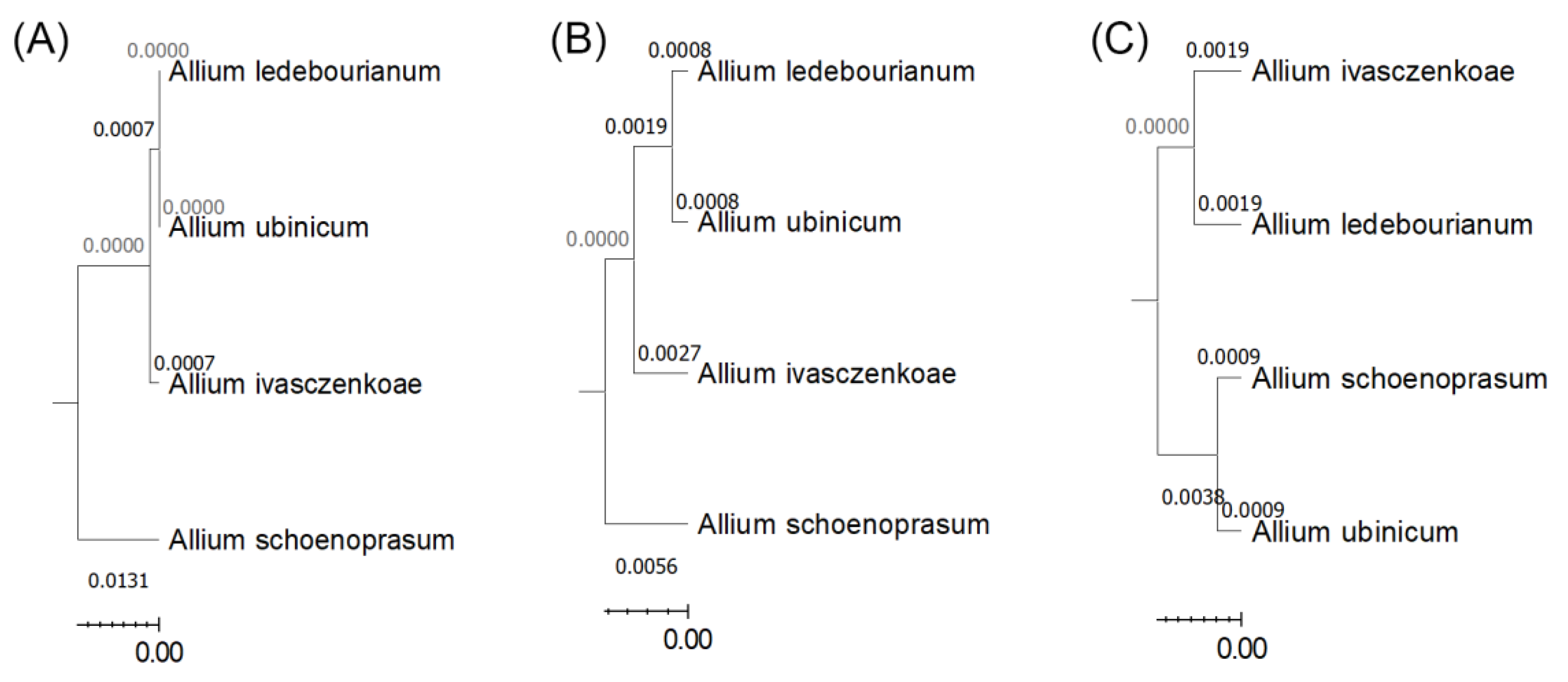

The genus Allium L. (Amaryllidaceae) comprises ecologically flexible species widespread across mountain ecosystems, yet the relationships among morphology, environment, and genetics within section Schoenoprasum in Central Asia remain poorly understood. This study investigated four taxa – A. ledebourianum, A. ivasczenkoae, A. ubinicum, and A. schoenoprasum – from the Kazakhstan Altai to assess their morphological variation, ecological preferences, phytochemical activity, and genetic relationships. Populations occurred on gentle chernozem slopes under humid, nutrient-rich conditions and showed stable regeneration dominated by young individuals. Morphometric analyses revealed pronounced interspecific differentiation: A. ledebourianum attained the greatest height and umbel size, whereas A. ubinicum was smallest but possessed proportionally larger floral organs. Principal component analysis explained 94% of total variance, distinguishing A. ubinicum and A. schoenoprasum from the remaining taxa. Floral traits correlated significantly with temperature, moisture, and soil reaction, indicating strong environmental influence on phenotype. Extract assays showed variable bioactivity, with A. ubinicum displaying the highest antioxidant potential (IC₅₀ = 88 µL) and highest cytotoxicity (LC50 of 5.9 μg/mL), while A. ledebourianum shows no antioxidant activity and the lowest toxicity (LC₅₀ of 10.9 μg/mL). Phylogenetic reconstruction using matK, rbcL, and psbA–trnH chloroplast markers confirmed close affinity between A. ledebourianum and A. ivasczenkoae, while A. ubinicum formed a distinct lineage. Together, morphological, ecological, and molecular data highlight the Kazakhstan Altai as a center of diversification for section Schoenoprasum. These results emphasize the adaptive plasticity of endemic Allium species and their potential as sources of valuable bioactive compounds, underscoring the importance of conserving genetically and morphologically diverse populations in mountain ecosystems.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Expeditions

2.2. Morphometric Analysis

2.3. Analyses of Cytotoxicity and Antioxidant Activity

2.4. Genetic Analysis

2.5. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Populational and Ecological Features

3.2. Morphometric Characteristics of Plants and Flowers

3.3. Cytotoxic and Antioxidant Activity of Ethanolic Extracts

3.4. Genetic Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographic Structure, Ecological Niche and Morphometric Differentiation of the Allium Section Schoenoprasum in Kazakhstan Altai

4.2. Bioactivity in Four Allium Species from the Kazakhstan Altai

4.3. Phylogenetic Implications and Evolutionary Insights of Chloroplast Markers

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AL | Anther length |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AW | Anther width |

| L | Light |

| M | Moisture |

| N | Nutrient availability |

| OL | Ovary length |

| OW | Ovary width |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PCL | Pistil column length |

| PL | Petal length |

| PW | Petal width |

| R | Soil reaction (ph) |

| S | Salinity |

| SL | Stamen length |

| T | Temperature |

References

- Chase, M.W.; Christenhusz, M.J.M.; Fay, M.F.; Byng, J.W.; Judd, W.S.; Soltis, D.E.; Mabberley, D.J.; Sennikov, A.N.; Soltis, P.S.; Stevens, P.F. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016, 181, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, G.; Dhatt, A.S.; Malik, A.A. A review of genetic understanding and amelioration of edible Allium species. Food Rev. Int. 2021, 37, 415–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastaki, S.M.; Ojha, S.; Kalasz, H.; Adeghate, E. Chemical constituents and medicinal properties of Allium species. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 476, 4301–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitpayeva, G.T.; Kudabayeva, G.M.; Dimeyeva, L.A.; Gemejiyeva, N.G.; Vesselova, P.V. Crop wild relatives of Kazakhstani Tien Shan: Flora, vegetation, resources. Plant Divers. 2020, 42, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochar, K.; Kim, S.H. Conservation and global distribution of onion (Allium cepa L.) germplasm for agricultural sustainability. Plants 2023, 12, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubentayev, S.A.; Alibekov, D.T.; Perezhogin, Y.V.; Lazkov, G.A.; Kupriyanov, A.N.; Ebel, A.L.; Kubentayeva, B.B. Revised checklist of endemic vascular plants of Kazakhstan. PhytoKeys 2024, 238, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumbembayev, A.A.; Kotukhov, Y.A.; Danilova, A.N.; Aitzhan, M. Endemic and endangered vascular flora of Kazakhstan’s Altai Mountains: A baseline for sustainable biodiversity conservation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, N.V.; Polyakov, P.P. Allium L. In Flora Kazakhstana; Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan, 1958; Vol. 2, pp. 134–193.

- Abdulina, S.A. Checklist of Vascular Plants of Kazakhstan; Institute of Botany and Plant Introduction: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 1999; pp. 1–187. [Google Scholar]

- Kotukhov, Y.A.; Danilova, A.N.; Anufrieva, O.A. Synopsis of Alliums (Allium L.) of the Kazakh Altai, Saur-Manrak and Zaisan Basin; Yubileynaya Editorial Board: Kazakhstan, 2011; p. 171. [Google Scholar]

- Vesselova, P.V.; Kudabayeva, G.M.; Abdildanov, D.S.; Osmonali, B.B.; Ussen, S.; Skaptsov, M.V.; Friesen, N. Integral assessment of species of the genus Allium L. (Amaryllidaceae) in the western part of the Kyrgyz Alatau. Plants 2025, 14, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagimanova, D.; Raiser, O.; Danilova, A.; Turzhanova, A.; Khapilina, O. Micropropagation of rare endemic species Allium microdictyon Prokh. threatened in Kazakhstani Altai. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra i Laliga, L.; Shomurodov, H. New locations for Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan flora (Central Asia). [Unpublished work] 2025, submitted.

- Lim, S.R.; Lee, J.A. Antioxidant activity and anti-inflammatory effects of ethanol extract from Allium schoenoprasum. J. Conv. Inf. Technol. 2020, 10, 232–239. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.; Chauhan, G.; Krishan, P.; Shri, R. Allium schoenoprasum L.: A review of phytochemistry, pharmacology and future directions. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 2202–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Jia, C.; Lu, J.; Yu, Z. Metabolism of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity in different tissue parts of post-harvest chive (Allium schoenoprasum L.). Antioxidants 2024, 13, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubentayev, S.A.; Khasenova, A.E.; Imanbayeva, A.A.; Alibekov, D.T. Morphology of seeds of rare and endemic plants of Kazakhstan. Fundam. Exp. Biol. 2022, 107, 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sumbembayev, A.; Lagus, O.; Danilova, A.; Aimenova, Z.; Seilkhan, A.; Takiyeva, Z.; Rewicz, A.; Nowak, S. Seed morphology of Allium L. endemic species from section Schoenoprasum (Amaryllidaceae) in eastern Kazakhstan. Biology 2025, 14, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesen, N.; Smirnov, S.V.; Leweke, M.; Seregin, A.P.; Fritsch, R.M. Taxonomy and phylogenetics of Allium section Decipientia (Amaryllidaceae): morphological characters do not reflect the evolutionary history revealed by molecular markers. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2021, 197, 190–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, N. Introduction to edible alliums: evolution, classification and domestication. In Edible Alliums: Botany, Production and Uses; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2022; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Friesen, N.; Lazkov, G.; Levichev, I.G.; Leweke, M.; Abdildanov, D.; Turdumatova, N.; Fritsch, R.M. Taxonomy and dated molecular phylogeny of Allium oreophilum sensu lato (A. subg. Porphyroprason) uncover a surprising number of cryptic taxa. Taxon 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abugalieva, S.; Volkova, L.; Genievskaya, Y.; Ivaschenko, A.; Kotukhov, Y.; Sakauova, G.; Turuspekov, Y. Taxonomic assessment of Allium species from Kazakhstan based on ITS and matK markers. BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scobeyeva, V.A.; Artyushin, I.V.; Krinitsina, A.A.; Nikitin, P.A.; Antipin, M.I.; Kuptsov, S.V.; Speranskaya, A.S. Gene loss, pseudogenization in plastomes of genus Allium (Amaryllidaceae), and putative selection for adaptation to environmental conditions. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 674783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdildanov, D.S.; Vesselova, P.V.; Kudabayeva, G.M.; Osmonali, B.B.; Skaptsov, M.V.; Friesen, N. Endemic of Kazakhstan Allium lehmannianum Merckl. ex Bunge and its position within the genus Allium. Plants 2025, 14, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khapilina, O.; Raiser, O.; Danilova, A.; Shevtsov, V.; Turzhanova, A.; Kalendar, R. DNA profiling and assessment of genetic diversity of relict species Allium altaicum Pall. on the territory of Altai. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khapilina, O.; Turzhanova, A.; Danilova, A.; Tumenbayeva, A.; Shevtsov, V.; Kotukhov, Y.; Kalendar, R. Primer binding site (PBS) profiling of genetic diversity of natural populations of endemic species Allium ledebourianum Schult. BioTech 2021, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najeebullah, S.; Shinwari, Z.K.; Jan, S.A.; Khan, I.; Ali, M. Ethnomedicinal and phytochemical properties of genus Allium: A review of recent advances. Pak. J. Bot. 2021, 53, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnia, D.; Ajiati, D.; Heliawati, L.; Sumiarsa, D. Antioxidant properties and structure–antioxidant activity relationship of Allium species leaves. Molecules 2021, 26, 7175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwar, K.; Ochar, K.; Seo, Y.A.; Ha, B.K.; Kim, S.H. Alliums as potential antioxidants and anticancer agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadyrbayeva, G.; Zagórska, J.; Grzegorczyk, A.; Gaweł-Bęben, K.; Strzępek-Gomółka, M.; Ludwiczuk, A.; Kukula-Koch, W. The phenolic compounds profile and cosmeceutical significance of two Kazakh species of onions: Allium galanthum and A. turkestanicum. Molecules 2021, 26, 5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, H.; Aziz, S.; Nasar, S.; Waheed, M.; Manzoor, M.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Bussmann, R.W. Distribution patterns of alpine flora for long-term monitoring of global change along a wide elevational gradient in the Western Himalayas. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 48, e02702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saribaeva, H.S.; Abduraimov, O.; Allamuratov, A. Assessment of the population status of Allium oschaninii O. Fedtsch. in the mountains of Uzbekistan. Ekológia 2022, 41, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennikov, A.N.; Lazkov, G.A. Allium formosum Sennikov & Lazkov (Amaryllidaceae), a new species from Kyrgyzstan. PhytoKeys 2013, 21, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khar, A.; Hirata, S.; Abdelrahman, M.; Shigyo, M.; Singh, H. Breeding and genomic approaches for climate-resilient garlic. In Genomic Designing of Climate-Smart Vegetable Crops; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 359–383. [Google Scholar]

- Gurushidze, M.; Mashayekhi, S.; Blattner, F.R.; Friesen, N.; Fritsch, R.M. Phylogenetic relationships of wild and cultivated species of Allium section Cepa inferred by nuclear rDNA ITS sequence analysis. Plant Syst. Evol. 2007, 269, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusupov, Z.; Deng, T.; Volis, S.; Khassanov, F.; Makhmudjanov, D.; Tojibaev, K.; Sun, H. Phylogenomics of Allium section Cepa (Amaryllidaceae) provides new insights on domestication of onion. Plant Divers. 2021, 43, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattorusso, E.; Lanzotti, V.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O.; Cicala, C. The flavonoids of leek, Allium porrum. Phytochemistry 2001, 57, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radovanović, B.; Mladenović, J.; Radovanović, A.; Pavlović, R.; Nikolić, V. Phenolic composition, antioxidant, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of Allium porrum L. (Serbia) extracts. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2015, 3, 564–569. [Google Scholar]

- Peet, R.K.; Wentworth, T.R.; White, P.S. A flexible, multipurpose method for recording vegetation composition and structure. Castanea 1998, 63, 262–274. [Google Scholar]

- Danilova, A.N.; Sumbembayev, A.A. The status of the Dactylorhiza incarnata populations in the Kalba Altai, Kazakhstan. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2021, 22, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tichý, L.; Axmanová, I.; Dengler, J.; Guarino, R.; Jansen, F.; Midolo, G.; Chytrý, M. Ellenberg-type indicator values for European vascular plant species. J. Veg. Sci. 2023, 34, e13168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.G. An essay on juvenility, phase change, and heteroblasty in seed plants. Int. J. Plant Sci. 1999, 160, S105–S111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vdovina, T.A.; Isakova, E.A.; Lagus, O.A.; Sumbembayev, A.A. Selection assessment of promising forms of natural Hippophae rhamnoides (Elaeagnaceae) populations and their offspring in the Kazakhstan Altai Mountains. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2024, 25, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.N.; Ferrigni, N.R.; Putnam, J.E.; Jacobsen, L.B.; Nichols, D.E.J.; McLaughlin, J.L. Brine shrimp: a convenient general bioassay for active plant constituents. Planta Med. 1982, 45, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aimenova, Z.E.; Matchanov, A.D.; Esanov, R.S.; Sumbembayev, A.A.; Duissebayev, S.E.; Dzhumanov, S.D.; Smailov, B.M. Phytochemical profile of Eranthis longistipitata Regel from three study sites in the Kazakhstan part of the Western Tien Shan. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2023, 24, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C.L.W.T. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.L.; Yu, S.; Yu, J.; Yu, L.; Zhou, S.L. A modified CTAB protocol for plant DNA extraction. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2013, 48, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, N.C.; Drost, D.T.; Varga, W.A.; Shultz, L.M. Demography, reproduction, and dormancy along altitudinal gradients in three intermountain Allium species with contrasting abundance and distribution. Flora 2011, 206, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.O.; Roy, D.B.; Mountford, J.O.; Bunce, R.G. Extending Ellenberg’s indicator values to a new area: an algorithmic approach. J. Appl. Ecol. 2000, 37, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, D.; Guisan, A. Ecological indicator values reveal missing predictors of species distributions. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.E.; Baasanmunkh, S.; Nyamgerel, N.; Oh, S.Y.; Song, J.H.; Yusupov, Z.; Choi, H.J. Flower morphology of Allium (Amaryllidaceae) and its systematic significance. Plant Divers. 2023, 46, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltis, P.S.; Soltis, D.E. Plant genomes: markers of evolutionary history and drivers of evolutionary change. Plants People Planet 2021, 3, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.S.; Tang, Z.J.; Chen, K.; Ma, X.J.; Zhou, S.D.; He, X.J.; Xie, D.F. Investigating the variation in leaf traits within the Allium prattii C.H. Wright population and its environmental adaptations. Plants 2025, 14, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assadpour, S.; Nabavi, S.M.; Nabavi, S.F.; Dehpour, A.A.; Ebrahimzadeh, M.A. In vitro antioxidant and antihemolytic effects of the essential oil and methanolic extract of Allium rotundum L. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Friesen, N.; Fritsch, R.; Blattner, F. Phylogeny and new intrageneric classification of Allium (Alliaceae) based on nuclear ribosomal DNA ITS sequences. Aliso 2006, 22, 372–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.J.; Liu, J.Q.; Guo, X.L.; Xiao, Q.Y.; He, X.J. Taxonomic revision of Allium cyathophorum (Amaryllidaceae). Phytotaxa 2019, 415, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipek, M.; Ipek, A.; Simon, P.W. Testing the utility of matK and ITS DNA regions for discrimination of Allium species. Turk. J. Bot. 2014, 38, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvarkhah, S.; Khajeh-Hosseini, M.; Rashed-Mohassel, M.H.; Panah, A.D.E.; Hashemi, H. Identification of three species of genus Allium using DNA barcoding. Int. J. Agric. Crop Sci. 2013, 5, 1195. [Google Scholar]

- Bigtas, A.I.B.; Moreno, P.G.G.; Heralde III, F. Preliminary evaluation of rbcL, matK, and SRAP markers for the molecular characterization of five Philippine Allium sativum varieties. Philipp. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 1, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sinitsyna, T.; Friesen, N. Taxonomic review of Allium senescens subsp. glaucum (Amaryllidaceae). Feddes Repert. 2018, 129, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschegger, P.; Jakše, J.; Trontelj, P.; Bohanec, B. Origins of Allium ampeloprasum horticultural groups and a molecular phylogeny of the section Allium (Allium: Alliaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2010, 54, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, E.J.; Mashayekhi, S.; McNeal, D.W.; Columbus, J.T.; Pires, J.C. Molecular systematics of Allium subgenus Amerallium (Amaryllidaceae) in North America. Am. J. Bot. 2013, 100, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Family | Plant communities with the participation of the Schoenoprasum section in the Kazakhstan Altai | Plants of Koktau Mountains | Plants of West Altai Reserve | Plants of Kazakhstan Altai (general) | ||||

| Number of species/ Percentage of the Total number of species, % | Number of genera/ Percentage of the Total number of genera, % | Number of species/ Percentage of the Total number of species, % | Number of genera/ Percentage of the Total number of genera, % | Number of species/ Percentage of the Total number of species, % | Number of genera/ Percentage of the Total number of genera, % | Number of species/ Percentage of the Total number of species, % | Number of genera/ Percentage of the Total number of genera, % | |

| Poaceae | 18/14.5 | 11/14.4 | 64/7.7 | 28/8.1 | 101/12.7 | 32/9.4 | 308/12.6 | 62/8.9 |

| Asteraceae | 12/9.6 | 10/13.1 | 129/15.5 | 44/12.7 | 100/12.6 | 45/13.3 | 324/13.3 | 82/11.9 |

| Cyperaceae | 11/8.8 | 2/2.6 | 32/3.8 | 4/1.1 | 34/4.3 | 5/1.4 | 96/3.9 | 9/1.3 |

| Ranunculaceae | 9/7.2 | 6/7.9 | 38/4.5 | 14/4.0 | 34/4.3 | 15/4.4 | 103/4.2 | 26/3.7 |

| Salicaceae | 9/7.2 | 2/2.6 | 16/1.9 | 2/0.6 | 27/3.4 | 2/0.5 | 56/2.3 | 2/0.3 |

| Rosaceae | 9/7.2 | 8/10.5 | 48/5.8 | 20/5.8 | 45/5.7 | 18/5.3 | 109/4.5 | 28/4.0 |

| Fabaceae | 7/5.6 | 3/3.9 | 47/5.6 | 15/4.3 | 37/4.5 | 11/3.2 | 183/7.5 | 24/3.5 |

| Apiaceae | 6/4.8 | 5/6.5 | 23/2.7 | 15/4.3 | 22/2.8 | 16/4.7 | 71/2.9 | 40/5.8 |

| Amaryllidaceae | 5/4.0 | 1/1.3 | 15/1.8 | 1/0.3 | 14/1.8 | 1/0.3 | 45/1.8 | 1/0.15 |

| Geraniaceae | 3/2.4 | 1/1.3 | 8/0.9 | 2/0.6 | 5/0.6 | 2/0.5 | 12/0.4 | 2/0.3 |

| Total | 89/71.7 | 49/64.4 | 420/50.7 | 145/41.8 | 419/52.4 | 147/43.5 | 1307/53.6 | 276/40.1 |

| Traits | Species | ||||

| A. ledebourianum | A. ivasczenkoae | A. ubinicum | A. schoenoprasum | ||

| Plant height (cm) | min-max M±SD CV, % |

86 – 110 94.18±5.55 8.89 |

54 – 61.5 58.45±1.72 4.18 |

30 – 50 39.85±3.96 14.09 |

49 – 71 57.8±4.58 11.23 |

| Number of stems per clump (count) | min-max M±SD CV, % |

2 – 8 4.56±0.92 38.35 |

1 – 4 2.7±0.74 39.23 |

1 – 6 3.31±0.62 39.05 |

2 – 7 4.06±0.68 31.73 |

| Number of leaves per clump (count) | min-max M±SD CV, % |

68 – 150 96.5±17.04 24.17 |

18 – 42 31±5.69 26.03 |

7 – 15 11.5±2.02 25.01 |

6 – 10 7.6±1.29 24.18 |

| Stem length (cm) | min-max M±SD CV, % |

83 – 95 88.5±2.58 4.13 |

49 – 61 56.3±2.7 6.8 |

32 – 44 37.35±2.83 10.74 |

41 – 63 53.25±5.41 14.41 |

| Stem diameter at base (mm) | min-max M±SD CV, % |

5 – 8 6.4±0.59 13.17 |

3 – 4 3.6±0.36 14.34 |

2 – 4 3.1±0.4 18.31 |

3 – 5 3.6±0.49 19.42 |

| Flower stalk length (mm) | min-max M±SD CV, % |

44 – 86 65.7±8.10 17.48 |

35 – 58 42.85±4.72 15.62 |

19 – 33.5 28.7±3.04 15.03 |

30 – 41.5 33.8±2.86 12 |

| Leaf length (cm) | min-max M±SD CV, % |

86 – 104 93.6±3.72 5.63 |

36 – 70 54.45±7.86 20.47 |

38 – 54 43.15±4.61 15.13 |

20 – 57 40.1±7.46 26.4 |

| Leaf width (mm) | min-max M±SD CV, % |

7 – 12 9±1.12 18.88 |

2 – 5 3.8±0.65 24.18 |

3 – 5 3.7±0.47 18.24 |

2 – 3 2.5±0.37 21.08 |

| M – the mean value of the trait, SD – standard deviation, min-max – minimal and maximal values, CV – coefficient of variation. | |||||

| Trait | Species | ||||

| A. ledebourianum | A.ivasczenkoae | A. ubinicum | A.schoenoprasum | ||

| Inflorescence length (mm) | min-max M±SD CV, % |

25.5 – 38 31.25±3.22 14.61 |

16 – 23.5 20.15±1.49 10.53 |

20 – 25 23.2±1.36 8.33 |

21 – 30 23.6±2.35 14.15 |

| Inflorescence diameter (mm) | min-max M±SD CV, % |

40.5 – 56 49.2±3.39 9.78 |

20.5 – 33.5 27±3.1 16.3 |

22 – 36 28.6±3.39 16.82 |

26 – 41 34.3±3.71 15.37 |

| Number of flowers per inflorescence (count) | min-max M±SD CV, % |

61 – 93 74.16±11.87 16 |

18 – 22 20.5±1.37 6.72 |

16 – 30 19.37±3.50 22.14 |

24 – 44 35.17±7.19 20.45 |

| M – the mean value of the trait, SD – standard deviation, min-max – minimal and maximal values, CV – coefficient of variation. | |||||

| Value | Petal | Stamen length (mm) | Pistil column length (mm) | Ovary | Anther | |||

| Length (mm) | Width (mm) | Length (mm) | Width (mm) | Length (mm) | Width (mm) | |||

| Allium ubinicum Kotukhov | ||||||||

| M±SD CV, % P% |

11.982±0.438 9.554 1.744 |

3.258±0.154 12.356 2.256 |

5.129±0.221 11.270 2.058 |

3.439±0.179 13.399 2.488 |

3.687±0.352 25.002 4.564 |

2.701±0.245 23.802 4.346 |

1.211±0.045 9.646 1.761 |

0.649±0.028 11.281 2.060 |

| Allium schoenoprasum L. | ||||||||

| M±SD CV, % P% |

10.657±0.226 5.560 1.015 |

3.163±0.137 11.391 2.079 |

4.232±0.287 17.749 3.240 |

3.089±0.231 19.580 3.574 |

2.513±0.164 17.142 3.129 |

2.003±0.120 15.668 2.860 |

1.124±0.034 7.894 1.441 |

0.641±0.036 14.808 2.703 |

| Allium ledebourianum Schult. & Schult.f. | ||||||||

| M±SD CV, % P% |

6.923±0.196 7.429 1.356 |

2.391±0.086 9.438 1.723 |

6.756±0.326 12.657 2.311 |

6.808±0.618 13.723 4.339 |

2.194±0.070 8.398 1.533 |

2.044±0.086 10.990 2.006 |

1.263±0.039 8.006 1.462 |

0.679±0.031 11.909 2.174 |

| Allium ivasczenkoae Kotukhov | ||||||||

| M±SD CV, % P% |

11.459±0.344 7.840 1.431 |

3.519±0.077 5.716 1.044 |

4.861±0.387 20.858 3.808 |

4.069±0.318 11.808 3.734 |

2.438±0.039 4.222 0.771 |

2.119±0.065 7.992 1.459 |

1.399±0.044 8.243 1.505 |

0.853±0.030 9.222 1.684 |

| M±SD – mean values ± standard deviation, CV – coefficient of variation, P% – the relative error of the sample mean | ||||||||

| Species | Concentration (μg/mL) | Dead/alive | Mean Mortality ± SD (%) | LC₅₀ (μg/mL) (95% CI) | ||

| Rep 1 | Rep 2 | Rep 3 | ||||

| Control (0.5% EtOH) |

— | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | — |

| A. schoenoprasum | 1 | 1/20 | 2/20 | 1/20 | 6.7 ± 2.3 | 9.6 (7.8–11.5) |

| 5 | 6/20 | 5/20 | 7/20 | 30.0 ± 4.4 | ||

| 10 | 11/20 | 12/20 | 10/20 | 55.0 ± 4.3 | ||

| A. ivasczenkoae | 1 | 2/20 | 1/20 | 2/20 | 8.3 ± 2.3 | 7.8 (6.4–9.7) |

| 5 | 7/20 | 6/20 | 8/20 | 35.0 ± 5.0 | ||

| 10 | 13/20 | 12/20 | 12/20 | 62.0 ± 3.6 | ||

| A. ledebourianum | 1 | 0/20 | 1/20 | 1/20 | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 10.9 (8.9–11.9) |

| 5 | 3/20 | 4/20 | 3/20 | 16.7 ± 2.9 | ||

| 10 | 6/20 | 7/20 | 6/20 | 31.7 ± 2.3 | ||

| A. ubinicum | 1 | 3/20 | 2/20 | 3/20 | 13.3 ± 2.3 | 5.9 (4.7–7.3) |

| 5 | 9/20 | 8/20 | 9/20 | 42.0 ± 3.5 | ||

| 10 | 15/20 | 14/20 | 13/20 | 70.0 ± 3.5 | ||

| # | Species | IC50, μL |

| 1 | A. schoenoprasum | 245 ± 4.2 |

| 2 | A. ivasczenkoae | 319 ± 7.6 |

| 3 | A. ledebourianum | - |

| 4 | A. ubinicum | 88 ± 1.4 |

| Base pairs | A. ivasczenkoae, % | A. ledebourianum, % | A. schoenoprasum, % | A. ubinicum, % | Mean, % |

| MatK | |||||

| T(U) | 32.0 | 32.2 | 31.9 | 32.2 | 32.1 |

| C | 14.0 | 14.0 | 14.3 | 14.0 | 14.1 |

| A | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.2 | 39.5 | 39.4 |

| G | 14.5 | 14.3 | 14.6 | 14.3 | 14.4 |

| Total | 684 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| PsbA-TrnH | |||||

| T(U) | 34.1 | 34.1 | 34.3 | 34.1 | 34.1 |

| C | 17.4 | 17.1 | 17.3 | 17.3 | 17.3 |

| A | 29.5 | 29.8 | 29.5 | 29.6 | 29.6 |

| G | 19.0 | 19.0 | 19.0 | 19.0 | 19.0 |

| Total | 648 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| RbcL | |||||

| T(U) | 28.3 | 28.4 | 28.7 | 28.9 | 28.6 |

| C | 21.7 | 21.6 | 21.3 | 21.3 | 21.5 |

| A | 28.3 | 28.1 | 27.9 | 27.7 | 28.0 |

| G | 21.7 | 21.9 | 22.1 | 22.1 | 22.0 |

| Total | 538 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).