Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

14 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. CLAD Development in Lung Transplantation

| Parameter | No-CLAD group Frequency (total valid cases) |

CLAD group Frequency (total valid cases) |

Chi-square (p-value) | Kaplan-Meier Log-rank test (p-value) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient | Recipient sex (% female) | 43.43 (297) | 31.88 (160) | 0.0208 | 0.0082 |

| Recipient age bin | 26.60 (297) | 21.88 (160) | 0.3173 | 0.4561 | |

| Recipient smoker (never) | 24.24 (297) | 21.02 (157) | 0.5107 | 0.0198 | |

| Tobacco consumption bin | 22.52 (222) | 21.01 (119) | 0.8535 | 0.9966 | |

| Hypertension (yes) | 21.55 (297) | 17.09 (158) | 0.3128 | 0.7294 | |

| Diabetes (yes) | 7.74 (297) | 11.39 (158) | 0.2619 | 0.9251 | |

| Dyslipidemia (yes) | 36.70 (297) | 24.36 (156) | 0.0105 | 0.7057 | |

| Size bin | 21.01 (276) | 25.00 (120) | 0.4561 | 0.2142 | |

| Weight bin | 24.19 (277) | 26.67 (120) | 0.6906 | 0.7257 | |

| BMI bin | 23.55 (276) | 27.50 (120) | 0.4776 | 0.5464 | |

| LAS score bin | 25.10 (255) | 25.00 (92) | 1.0000 | 0.9220 | |

| Donor | Donor sex (% female) | 50.51 (297) | 44.38 (160) | 0.2490 | 0.1152 |

| Hypertension (yes) | 33.68 (285) | 31.79 (151) | 0.7691 | 0.8568 | |

| Diabetes (yes) | 10.47 (277) | 3.62 (138) | 0.0274 | 0.1229 | |

| Donor smoker (yes) | 32.06 (287) | 39.47 (152) | 0.1474 | 0.4799 | |

| Donor age bin | 26.94 (297) | 17.50 (160) | 0.0316 | 0.2675 | |

| Donor size bin | 17.69 (294) | 19.62 (158) | 0.7049 | 0.2864 | |

| Donor weight bin | 24.91 (293) | 20.13 (159) | 0.3008 | 0.5310 | |

| Immunological | Anti-HLA class-I antibodies pre transplant (yes) | 9.02 (255) | 4.26 (94) | 0.2106 | 0.3894 |

| Anti-HLA class-II antibodies pre transplant (yes) | 5.10 (255) | 4.26 (94) | 0.9648 | 0.7539 | |

| Anti-MICA antibodies pre transplant (yes) | 1.01 (255) | 0.63 (94) | 1.0000 | 0.9468 | |

| Antibody verified eplet mismatch All bin | 20.20 (297) | 25.00 (160) | 0.2870 | 0.4267 | |

| Antibody verified eplet mismatch ABC bin | 20.20 (297) | 23.75 (160) | 0.4460 | 0.1478 | |

| Antibody verified eplet mismatch DQDR bin | 20.88 (297) | 27.50 (160) | 0.1377 | 0.7146 | |

| Antibody verified eplet mismatch DQA1DQB1 bin | 18.86 (297) | 23.13 (160) | 0.3372 | 0.8879 | |

| Antibody verified eplet mismatch DRB1345 bin | 20.88 (297) | 25.00 (160) | 0.3722 | 0.0864 | |

| PIRCHE II score bin | 26.60 (297) | 21.25 (160) | 0.2498 | 0.1915 | |

| PIRCHE II HLA-A bin | 24.58 (297) | 22.50 (160) | 0.7021 | 0.9443 | |

| PIRCHE II HLA-B bin | 26.26 (297) | 21.25 (160) | 0.2827 | 0.1881 | |

| PIRCHE II HLA-C bin | 23.91 (297) | 26.25 (160) | 0.6596 | 0.5086 | |

| PIRCHE II HLA-DQA1 bin | 24.58 (297) | 25.63 (160) | 0.8941 | 0.4268 | |

| PIRCHE II HLA-DQB1 bin | 26.26 (297) | 22.50 (160) | 0.4393 | 0.2650 | |

| PIRCHE II HLA-DRB1 bin | 24.58 (297) | 24.38 (160) | 1.0000 | 0.6668 | |

| EMMA score HLA-All bin | 22.90 (297) | 26.88 (160) | 0.4055 | 0.3461 | |

| EMMA score HLA-ABC bin | 25.59 (297) | 23.75 (160) | 0.7489 | 0.9439 | |

| EMMA score HLA-A bin | 22.90 (297) | 24.38 (160) | 0.8100 | 0.2867 | |

| EMMA score HLA-B bin | 23.91 (297) | 21.25 (160) | 0.5981 | 0.5953 | |

| EMMA score HLA-C bin | 20.54 (297) | 20.00 (160) | 0.9883 | 0.7256 | |

| EMMA score HLA-DQABDR bin | 22.22 (297) | 26.88 (160) | 0.3182 | 0.4498 | |

| EMMA score HLA-DQA1 bin | 14.48 (297) | 21.88 (160) | 0.0609 | 0.0936 | |

| EMMA score HLA-DQB1 bin | 22.90 (297) | 21.88 (160) | 0.8952 | 0.6383 | |

| EMMA score HLA-DR bin | 20.20 (297) | 25.63 (160) | 0.2245 | 0.0391 | |

| Lung transplant | Donation (DBD) | 74.07 (297) | 81.25 (160) | 0.1069 | 0.7096 |

| Type of transplant (Unipulmonar) | 14.48 (297) | 31.25 (160) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Indication (Elective) | 98.32 (297) | 95.00 (160) | 0.0820 | 0.1855 | |

| CMV pairing (High risk) | 14.74 (285) | 10.00 (150) | 0.2142 | 0.4139 | |

| Donor pO2 (mmHg) | 23.84 (281) | 25.48 (157) | 0.7904 | 0.3530 | |

| ECMO during surgery (yes) | 11.49 (296) | 9.49 (158) | 0.6220 | 0.2436 | |

| Ischemic time first bin | 23.57 (297) | 27.22 (158) | 0.4574 | 0.1018 | |

| Ischemic time second bin | 22.92 (253) | 26.36 (110) | 0.5676 | 0.4334 | |

| Surgery time bin | 25.30 (253) | 24.73 (93) | 1 | 0.1341 | |

| Transfusion (yes) | 30.20 (255) | 37.23 (94) | 0.2626 | 0.9374 | |

| Number of packed RBC bin | 22.08 (77) | 17.14 (35) | 0.7286 | 0.3023 | |

| Surgical reintervention (yes) | 6.40 (297) | 9.43 (159) | 0.3225 | 0.0835 | |

| Clinical | Induction (yes) | 90.64 (267) | 71.70 (106) | <0.0001 | 0.0327 |

| Calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus) | 97.25 (255) | 91.49 (94) | 0.0395 | 0.0197 | |

| Antimetabolite (mycophenolate) | 99.61 (255) | 100.00 (94) | 1 | 0.5640 | |

| Tracheostomy (yes) | 4.31 (255) | 6.38 (94) | 0.6056 | 0.2502 | |

| Hospitalization bin | 20.27 (296) | 29.94 (157) | 0.0286 | 0.0245 | |

| Intubation bin | 18.15 (248) | 23.08 (91) | 0.3890 | 0.4635 | |

| Primary graft dysfunction (yes) | 27.95 (297) | 26.25 (160) | 0.7810 | 0.9693 | |

| Primary graft dysfunction grade 3 (yes) | 14.29 (126) | 14.29 (133) | 1 | 0.3167 | |

| Acute cellular rejection (yes) | 41.08 (297) | 66.88 (160) | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | |

| Antibody mediated rejection (yes) | 3.37 (297) | 17.50 (160) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

2.2. Immunological Variables Associated with CLAD-Free Survival

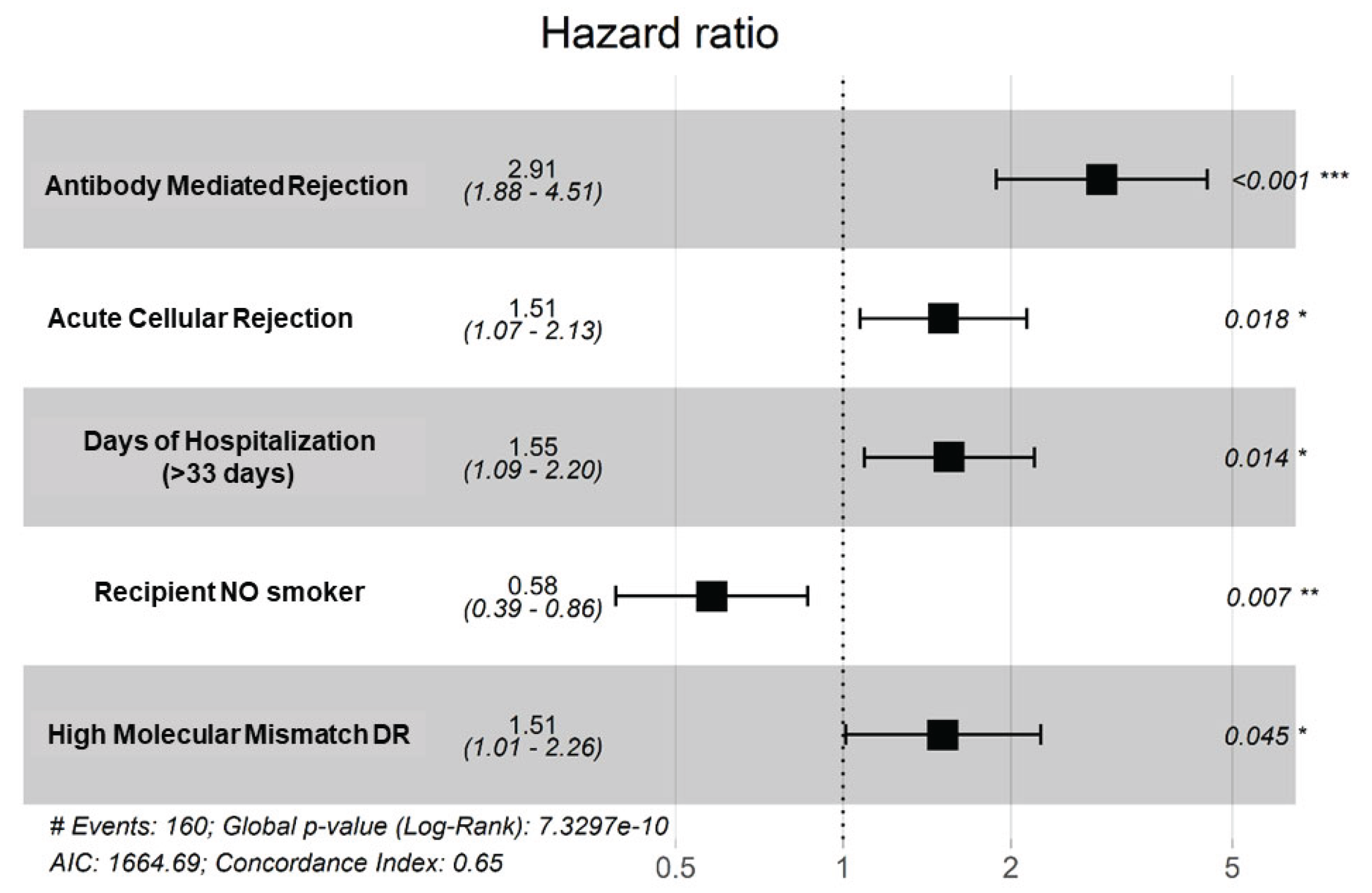

2.3. Prediction Model for CLAD

| Parameter | Variable | Univariate | Multivariate (Lasso+AIC) (n=215) |

Multivariate Final Model (n=457) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95CI | p-value | HR | 95CI | p-value | HR | 95CI | p-value | ||||||||||||||||||

| Recipient | Recipient sex (male) | 1.56 | 1.12-2.18 | 0.0087 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recipient smoker (never) | 0.63 | 0.43-0.93 | 0.0209 | 0.59 | 0.37-0.93 | 0.0225 | 0.58 | 0.39-0.86 | 0.0072 | |||||||||||||||||

| Donor | Donor sex (male) | 1.28 | 0.94-1.76 | 0.1163 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Donor age_bin | 0.79 | 0.53-120 | 0.2690 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Donor smoker | 1.13 | 0.81-1.56 | 0.4798 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Immunological | EMMA score HLA-DR_bin | 1.45 | 1.02-2.07 | 0.0403 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| MM-DR2 | 1.74 | 1.17-2.57 | 0.0061 | 1.62 | 1.02-2.58 | 0.0426 | 1.50 | 1.01-2.26 | 0.0452 | |||||||||||||||||

| Lung transplant | Donation (DBD) | 1.08 | 0.72-1.62 | 0.7091 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| CMV pairing (High risk) | 0.80 | 0.47-1.37 | 0.4147 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Donor pO2_bin | 1.19 | 0.83-1.70 | 0.3532 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ischemic time first_bin | 1.34 | 0.94-1.90 | 0.1027 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Clinical | Hospitalization days_bin | 1.48 | 1.05-2.08 | 0.0254 | 1.42 | 0.94-2.15 | 0.0983 | 1.55 | 1.09-2.20 | 0.0141 | ||||||||||||||||

| PGD 3 (yes) | 1.28 | 0.79-2.09 | 0.3186 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ACR | 1.86 | 1.34-2.58 | <0.0001 | 1.69 | 1.10-2.60 | 0.0173 | 1.51 | 1.07-2.13 | 0.0180 | |||||||||||||||||

| ABMR | 3.84 | 2.54-5.80 | <0.0001 | 2.70 | 1.48-4.93 | 0.0013 | 2.91 | 1.88-4.51 | <0.0001 | |||||||||||||||||

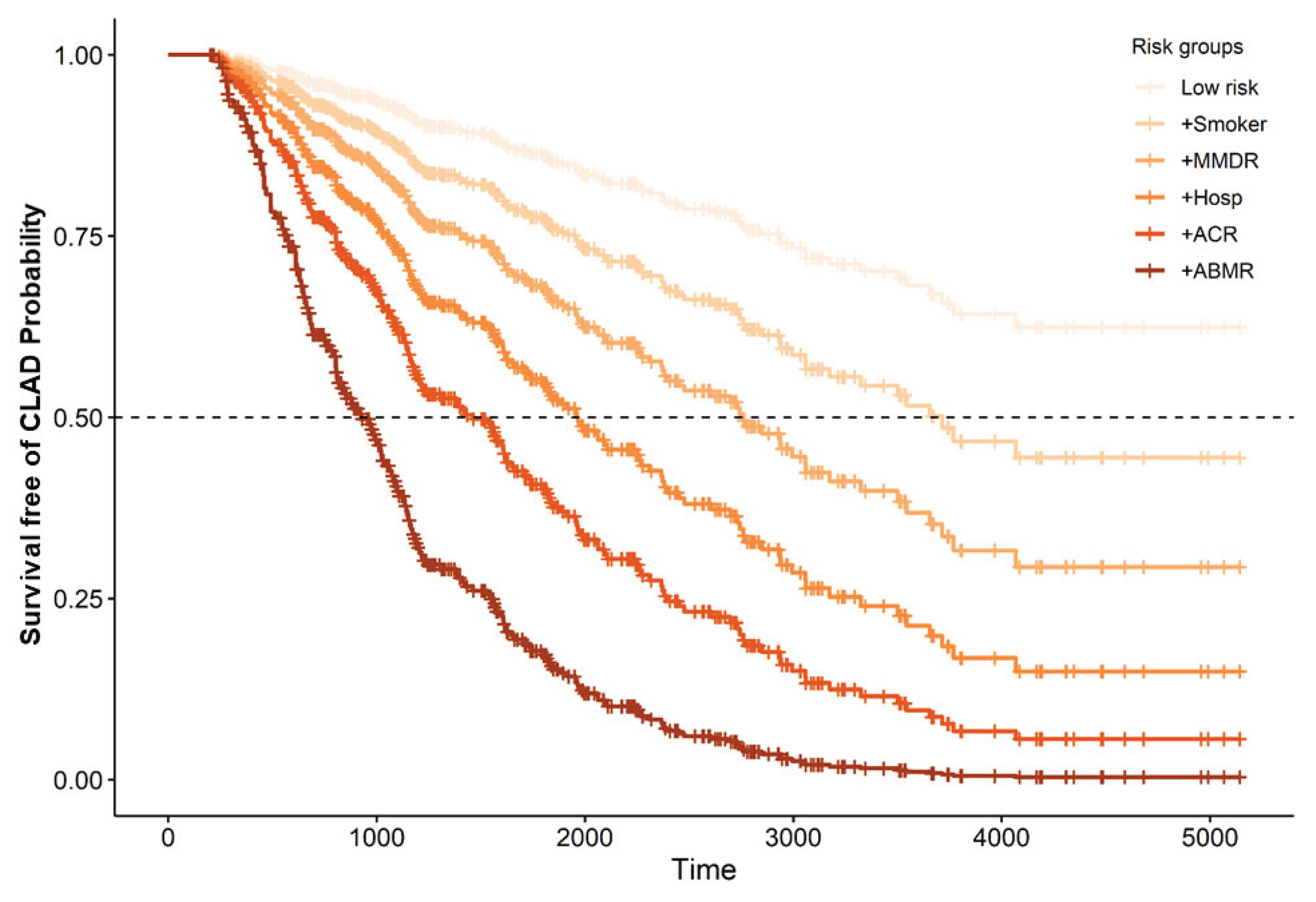

2.4. Dynamic Model for CLAD Prediction

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

4.2. Clinical Data

4.3. HLA Typing

4.4. Molecular Mismatch Algorithms

4.4.1. Eplet Mismatch

4.4.2. HLA-EMMA Mismatch

4.4.3. PIRCHE-II Scores

4.5. Statistical Analysis

4.5.1. List of Variables and Description, and Calculation

4.5.2. Calculation of New Immunological Parameters

4.5.3. Survival Analysis

4.5.4. Cox Regression Approach

4.5.5. Packages Used

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Copeland, C.A.F.; Snyder, L.D.; Zaas, D.W.; Jackson Turbyfill, W.; Davis, W.A.; Palmer, S.M. Survival after Bronchiolitis Obliterans Syndrome among Bilateral Lung Transplant Recipients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010, 182, 784–789. [CrossRef]

- Beeckmans, H.; Kerckhof, P.; Acet Öztürk, N.; Zajacova, A.; Van Slambrouck, J.; Bos, S.; Vermant, M.; Van Dieren, L.O.; Goeminne, T.; Vandervelde, C.; et al. Clinical Predictors for Restrictive Allograft Syndrome: A Nested Case-Control Study. American Journal of Transplantation 2025, 25, 1319–1338. [CrossRef]

- Roux, A.; Levine, D.J.; Zeevi, A.; Hachem, R.; Halloran, K.; Halloran, P.F.; Gibault, L.; Taupin, J.L.; Neil, D.A.H.; Loupy, A.; et al. Banff Lung Report: Current Knowledge and Future Research Perspectives for Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Antibody-Mediated Rejection (AMR). American Journal of Transplantation 2019, 19, 21–31. [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, E.; Vosoughi, D.; Wang, J.; Al-Refaee, J.; Berra, G.; Daigneault, T.; Duong, A.; Joe, B.; Moshkelgosha, S.; Keshavjee, S.; et al. Local Intragraft Humoral Immune Responses in Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2025, 44, 105–117. [CrossRef]

- Opelz, G. Strength of HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DR Mismatches in Relation to Short- and Long-Term Kidney Graft Survival. Collaborative Transplant Study. Transpl Int 1992, 5 Suppl 1, 621–624. [CrossRef]

- Afzal Nikaein, L.B.L.J.M.F.L.R.G.T.G.M.J.S.G.K. HLA Compatibility and Liver Transplant Outcome: Improved Patient Survival by HLA and Cross-Matching. Transplantation 1994, 58, 786–792.

- Opelz, G.; Wujciak, T. The Influence of HLA Compatibility on Graft Survival after Heart Transplantation. The Collaborative Transplant Study. N Engl J Med 1994, 330, 816–819. [CrossRef]

- Opelz, G.; Süsal, C.; Ruhenstroth, A.; Döhler, B. Impact of HLA Compatibility on Lung Transplant Survival and Evidence for an HLA Restriction Phenomenon: A Collaborative Transplant Study Report. Transplantation 2010, 90, 912–917. [CrossRef]

- Duquesnoy, R.J.; Askar, M. HLAMatchmaker: A Molecularly Based Algorithm for Histocompatibility Determination. V. Eplet Matching for HLA-DR, HLA-DQ, and HLA-DP. Hum Immunol 2007, 68, 12–25. [CrossRef]

- Lachmann, N.; Niemann, M.; Reinke, P.; Budde, K.; Schmidt, D.; Halleck, F.; Pruß, A.; Schönemann, C.; Spierings, E.; Staeck, O. Donor–Recipient Matching Based on Predicted Indirectly Recognizable HLA Epitopes Independently Predicts the Incidence of De Novo Donor-Specific HLA Antibodies Following Renal Transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation 2017, 17, 3076–3086. [CrossRef]

- Ono, K.; Ide, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Ohira, M.; Tahara, H.; Tanimine, N.; Yamane, H.; Ohdan, H. Molecular Mismatch Predicts T Cell-Mediated Rejection and De Novo Donor-Specific Antibody Formation After Living Donor Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl 2021, 27, 1592–1602. [CrossRef]

- Kleid, L.; Walter, J.; Vorstandlechner, M.; Schneider, C.P.; Michel, S.; Kneidinger, N.; Irlbeck, M.; Wichmann, C.; Möhnle, P.; Humpe, A.; et al. Predictive Value of Molecular Matching Tools for the Development of Donor Specific HLA-Antibodies in Patients Undergoing Lung Transplantation. HLA 2023, 102, 331–342. [CrossRef]

- Ellison, M.; Mangiola, M.; Marrari, M.; Bentlejewski, C.; Sadowski, J.; Zern, D.; Kramer, C.S.M.; Heidt, S.; Niemann, M.; Xu, Q.; et al. Immunologic Risk Stratification of Pediatric Heart Transplant Patients by Combining HLA-EMMA and PIRCHE-II. Front Immunol 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Lánczky, A.; Győrffy, B. Web-Based Survival Analysis Tool Tailored for Medical Research (KMplot): Development and Implementation. J Med Internet Res 2021, 23. [CrossRef]

- Flöthmann, K.; Davide de Manna, N.; Aburahma, K.; Kruszona, S.; Wand, P.; Bobylev, D.; Müller, C.; Carlens, J.; Schwerk, N.; Avsar, M.; et al. Impact of Donor Organ Quality on Recipient Outcomes in Lung Transplantation: 14-Year Single-Center Experience Using the Eurotransplant Lung Donor Score. JHLT Open 2024, 6, 100166. [CrossRef]

- Ghaidan, H.; Fakhro, M.; Lindstedt, S. Impact of Allograft Ischemic Time on Long-Term Survival in Lung Transplantation: A Swedish Monocentric Study. Scand Cardiovasc J 2020, 54, 322–329. [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, S.; Hell, G.; Levine, D.J.; Coiffard, B.; Severac, F.; Picard, C.; Bunel, V.; Le Pavec, J.; Essaidy, A.; Reynaud-Gaubert, M.; et al. Diagnostic Significance of Intragraft Donor–Specific Anti-HLA Antibodies in Pulmonary Antibody–Mediated Rejection. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2025. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Elrefaei, M.; Taupin, J.L.; Hitchman, K.M.K.; Hiho, S.; Gareau, A.J.; Iasella, C.J.; Marrari, M.; Belousova, N.; Bettinotti, M.; et al. Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction Is Associated with an Increased Number of Non-HLA Antibodies. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2024, 43, 663–672. [CrossRef]

- Comins-Boo, A.; Mora-Fernández, V.M.; Padrón-Aunceame, P.; Toriello-Suárez, M.; González-López, E.; Roa-Bautista, A.; Castro-Hernández, C.; Iturbe-Fernández, D.; Cifrián José, M.; López-Hoyos, M.; et al. Non-HLA Antibodies and the Risk of Antibody-Mediated Rejection without Donor-Specific Anti-HLA Antibodies After Lung Transplantation. Transplant Proc 2025, 57, 73–76. [CrossRef]

- Opelz, G.; Wujciak, T.; Döhler, B.; Scherer, S.; Mytilineos, J. HLA Compatibility and Organ Transplant Survival. Collaborative Transplant Study. Rev Immunogenet 1999.

- Yacoub, R.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Cravedi, P.; He, J.C.; Delaney, V.B.; Kent, R.; Chauhan, K.N.; Coca, S.G.; Florman, S.S.; Heeger, P.S.; et al. Analysis of OPTN/UNOS Registry Suggests the Number of HLA Matches and Not Mismatches Is a Stronger Independent Predictor of Kidney Transplant Survival. Kidney Int 2018, 93, 482–490. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Langner, T.; Inci, I.; Benden, C.; Schuurmans, M.; Weder, W.; Jungraithmayr, W. Impact of Human Leukocyte Antigen Mismatch on Lung Transplant Outcome. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2018, 26, 859–864. [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, C.; Rush, D.N.; Nevins, T.E.; Birk, P.E.; Blydt-Hansen, T.; Gibson, I.W.; Goldberg, A.; Ho, J.; Karpinski, M.; Pochinco, D.; et al. Class II Eplet Mismatch Modulates Tacrolimus Trough Levels Required to Prevent Donor-Specific Antibody Development. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017, 28, 3353–3362. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Min, J.W.; Kang, H.; Lee, H.; Eum, S.H.; Park, Y.; Yang, C.W.; Chung, B.H.; Oh, E.J. Combined Analysis of HLA Class II Eplet Mismatch and Tacrolimus Levels for the Prediction of De Novo Donor Specific Antibody Development in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 7357. [CrossRef]

- Kleid, L.; Walter, J.; Vorstandlechner, M.; Schneider, C.P.; Michel, S.; Kneidinger, N.; Irlbeck, M.; Wichmann, C.; Möhnle, P.; Humpe, A.; et al. Predictive Value of Molecular Matching Tools for the Development of Donor Specific HLA-Antibodies in Patients Undergoing Lung Transplantation. HLA 2023, 102, 331–342. [CrossRef]

- McCaughan, J.A.; Battle, R.K.; Singh, S.K.S.; Tikkanen, J.M.; Moayedi, Y.; Ross, H.J.; Singer, L.G.; Keshavjee, S.; Tinckam, K.J. Identification of Risk Epitope Mismatches Associated with de Novo Donor-Specific HLA Antibody Development in Cardiothoracic Transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation 2018, 18, 2924–2933. [CrossRef]

- Demir, Z.; Raynaud, M.; Divard, G.; Louis, K.; Truchot, A.; Niemann, M.; Ponsirenas, R.; Aubert, O.; Del Bello, A.; Hertig, A.; et al. Impact of HLA Evolutionary Divergence and Donor-Recipient Molecular Mismatches on Antibody-Mediated Rejection of Kidney Allografts. Nat Commun 2025, 16. [CrossRef]

- Parulekar, A.D.; Kao, C.C. Detection, Classification, and Management of Rejection after Lung Transplantation. J Thorac Dis 2019, 11, S1732–S1739. [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, M.; Ma, J.; Huszti, E.; Levy, L.; Berra, G.; Renaud-Picard, B.; Takahagi, A.; Ghany, R.; Sato, M.; Keshavjee, S.; et al. Association between Cytomegalovirus Viremia and Long-Term Outcomes in Lung Transplant Recipients. American Journal of Transplantation 2024, 24, 1057–1069. [CrossRef]

- Franz, M.; Aburahma, K.; Avsar, M.; Boethig, D.; Greer, M.; Alhadidi, H.; Sommer, W.; Tudorache, I.; Warnecke, G.; Haverich, A.; et al. Does Donor-Recipient Age Mismatch Have an Influence on Outcome after Lung Transplantation? A Single-Centre Experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2023, 63. [CrossRef]

- Pasupneti, S.; Nicolls, M.R. Airway Hypoxia in Lung Transplantation. Curr Opin Physiol 2019, 7, 21–26. [CrossRef]

- Banga, N.; Kanade, R.; Kappalayil, A.; Timofte, I.; Lawrence, A.; Bollineni, S.; Kaza, V.; Torres, F. Long-Term Outcomes Among Lung Transplant Recipients With High-Risk Cytomegalovirus Mismatch Managed With a Multimodality Regimen. Clin Transplant 2025, 39. [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp-Parent, C.; Jomphe, V.; Morisset, J.; Poirier, C.; Lands, L.C.; Nasir, B.S.; Ferraro, P.; Mailhot, G. Impact of Transplant Body Mass Index and Post-Transplant Weight Changes on the Development of Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction Phenotypes. Transplant Proc 2024, 56, 1420–1428. [CrossRef]

- Valentini, C.G.; Farina, F.; Pagano, L.; Teofili, L. Granulocyte Transfusions: A Critical Reappraisal. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2017, 23, 2034–2041. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.; Fishbein, M.C.; Snell, G.I.; Berry, G.J.; Boehler, A.; Burke, M.M.; Glanville, A.; Gould, F.K.; Magro, C.; Marboe, C.C.; et al. Revision of the 1996 Working Formulation for the Standardization of Nomenclature in the Diagnosis of Lung Rejection. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2007, 26, 1229–1242. [CrossRef]

- Verleden, G.M.; Glanville, A.R.; Lease, E.D.; Fisher, A.J.; Calabrese, F.; Corris, P.A.; Ensor, C.R.; Gottlieb, J.; Hachem, R.R.; Lama, V.; et al. Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction: Definition, Diagnostic Criteria, and Approaches to Treatment―A Consensus Report from the Pulmonary Council of the ISHLT. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2019, 38, 493–503. [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.J.; Glanville, A.R.; Aboyoun, C.; Belperio, J.; Benden, C.; Berry, G.J.; Hachem, R.; Hayes, D.; Neil, D.; Reinsmoen, N.L.; et al. Antibody-Mediated Rejection of the Lung: A Consensus Report of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2016, 35, 397–406. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, C.S.M.; Koster, J.; Haasnoot, G.W.; Roelen, D.L.; Claas, F.H.J.; Heidt, S. HLA-EMMA: A User-Friendly Tool to Analyse HLA Class I and Class II Compatibility on the Amino Acid Level. HLA 2020, 96, 43–51. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Total | Frequency (%) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient | Recipient sex (% female) | 457 | 180 (39.39) | ||

| Recipient age (years) | 457 | 56.8 (9.9) | 60.0 (53.9-63.5) | ||

| Recipient smoker (never) | 454 | 105 (23.13) | |||

| Tobacco consumption (cigarettes/day) |

341 | 37.2 (22.1) | 35 (20-50) | ||

| Hypertension (yes) | 455 | 91 (20.00) | |||

| Diabetes (yes) | 455 | 41 (9.01) | |||

| Dyslipidemia (yes) | 453 | 147 (32.45) | |||

| Size (meters) | 396 | 1.65 (0.09) | 1.66 (1.59-1.72) | ||

| Weight (kilograms) | 397 | 68.0 (12.7) | 68 (59-77) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 396 | 24.76 (3.55) | 25.0 (22.2-27.7) | ||

| LAS score | 347 | 34.4 (3.56) | 33.3 (32.1-35.5) | ||

| Donor | Donor sex (% female) | 457 | 236 (51.64) | ||

| Donor age (years) | 457 | 52.3 (14.2) | 55 (44-63) | ||

| Donor smoker (yes) | 439 | 152 (34.62) | |||

| Hypertension (yes) | 436 | 144 (33.03) | |||

| Diabetes (yes) | 415 | 34 (8.19) | |||

| Donor size (meters) | 452 | 1.67 (1.16) | 1.69 (1.62-1.75) | ||

| Donor weight (kilograms) | 452 | 73.26 (13.33) | 75 (65-80) | ||

| Immunological | Anti-HLA class-I antibodies pre transplant (yes) | 349 | 27 (7.74) | ||

| Anti-HLA class-II antibodies pre transplant (yes) | 349 | 17 (4.87) | |||

| Anti-MICA antibodies pre transplant (yes) | 457 | 4 (0.88) | |||

| Antibody verified eplet mismatch All | 457 | 16.91 (6.33) | 16 (13-21) | ||

| Antibody verified eplet mismatch ABC | 457 | 8.70 (3.65) | 8 (6-11) | ||

| Antibody verified eplet mismatch DQDR | 457 | 8.21 (4.74) | 8 (5-11) | ||

| Antibody verified eplet mismatch DQA1DQB1 | 457 | 6.08 (3.98) | 5 (3-9) | ||

| Antibody verified eplet mismatch DRB1345 | 457 | 2.13 (1.86) | 2 (1-3) | ||

| PIRCHE II score | 457 | 274.2 (111.9) | 270 (195-343) | ||

| PIRCHE II HLA-A | 457 | 54.9 (38.9) | 49 (27-76) | ||

| PIRCHE II HLA-B | 457 | 46.8 (28.0) | 43 (26-64) | ||

| PIRCHE II HLA-C | 457 | 47.6 (33.8) | 41 (23-67) | ||

| PIRCHE II HLA-DQA1 | 457 | 47.3 (40.2) | 45 (0-74) | ||

| PIRCHE II HLA-DQB1 | 457 | 48.9 (32.9) | 46 (25-68) | ||

| PIRCHE II HLA-DRB1 | 457 | 33.1 (19.8) | 31 (19-44) | ||

| EMMA score HLA-All | 457 | 57.4 (22.1) | 55 (41-73) | ||

| EMMA score HLA-ABC | 457 | 27.9 (10.5) | 27 (21-34) | ||

| EMMA score HLA-A | 457 | 12.8 (7.2) | 12 (8-17) | ||

| EMMA score HLA-B | 457 | 8.27 (4.64) | 8 (5-11) | ||

| EMMA score HLA-C | 457 | 6.88 (4.14) | 7 (4-10) | ||

| EMMA score HLA-DQABDR | 457 | 29.4 (19.0) | 26 (14-43) | ||

| EMMA score HLA-DQA1 | 457 | 9.81 (8.58) | 8 (0-18) | ||

| EMMA score HLA-DQB1 | 457 | 11.2 (8.52) | 9 (4-18) | ||

| EMMA score HLA-DR | 457 | 8.43 (5.58) | 8 (4-12) | ||

| Lung transplant | Donation (DBD) | 457 | 350 (76.6) | ||

| Type of transplant (Unipulmonar) | 457 | 93 (20.4) | |||

| Indication (Elective) | 457 | 444 (97.2) | |||

| CMV pairing (High risk) | 435 | 57 (13.1) | |||

| Donor pO2 (mmHg) | 438 | 382.8 (153.1) | 422 (350-484) | ||

| ECMO during surgery (yes) | 454 | 49 (10.8) | |||

| Ischemic time first (minutes) | 455 | 298.9 (130.6) | 275 (235-323) | ||

| Ischemic time second (minutes) | 363 | 419 (155.3) | 388 (335-450) | ||

| Surgery time (minutes) | 346 | 291.6 (76.1) | 290 (240-330.8) | ||

| Transfusion (yes) | 349 | 112 (32.1) | |||

| Number of packet RBC (units) | 112 | 2.72 (2.44) | 2 (1-4) | ||

| Surgical reintervention (yes) | 456 | 34 (7.46) | |||

| Clinical | Induction (yes) | 373 | 318 (76.6) | ||

| Calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus) | 349 | 334 (95.7) | |||

| Antimetabolite (mycophenolate) | 349 | 348 (99.7) | |||

| Tracheostomy (yes) | 349 | 17 (4.87) | |||

| Hospitalization (days) | 453 | 31.2 (20.0) | 25 (21-33) | ||

| Intubation (days) | 339 | 2.28 (3.1) | 1 (1-2) | ||

| Primary graft dysfunction (yes) | 457 | 125 (27.4) | |||

| Primary graft dysfunction grade 3 (yes) | 259 | 37 (14.3) | |||

| Acute cellular rejection (yes) | 457 | 229 (50.1) | |||

| Antibody mediated rejection (yes) | 457 | 38 (8.32) | |||

| Chronic allograft dysfunction (yes) | 457 | 160 (35.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).