Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

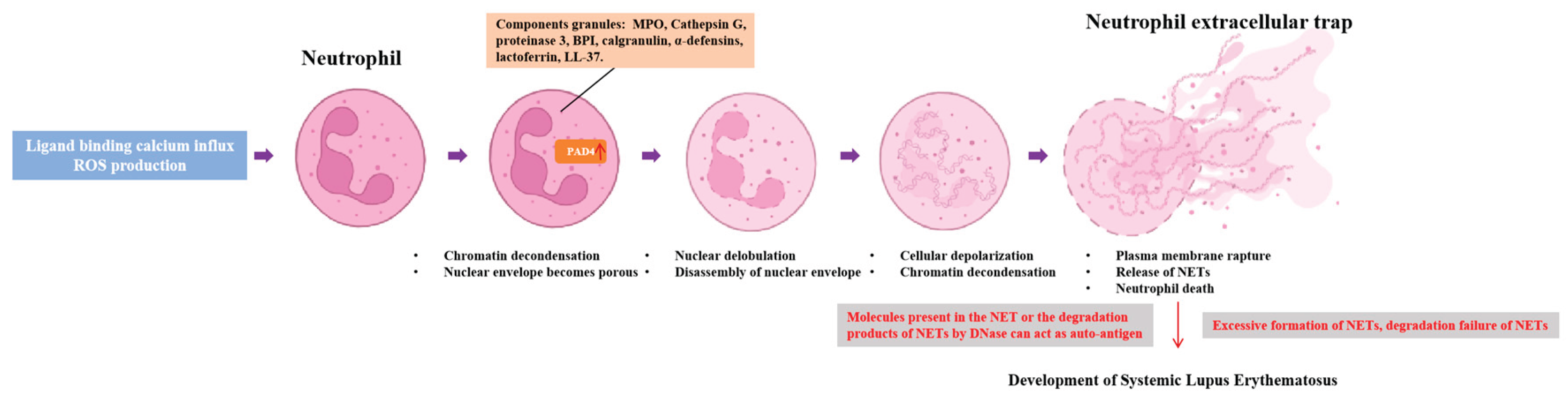

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex autoimmune disorder marked by autoantibody production and immune complex (IC) formation, leading to widespread inflammation and tissue damage. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) — web-like structures of DNA, histones, and antimicrobial proteins — support innate immunity but drive SLE pathogenesis when dysregulated. This review examines SLE-specific NET mechanisms, their crosstalk with oxidative stress, and their therapeutic potential as antioxidants. SLE patients exhibit excessive NET formation, driven by proinflammatory low-density granulocytes (LDG) and ICs, and impaired NET clearance (reduced DNase1/DNase1L3 activity or anti-nuclease autoantibodies), leading to circulating NET accumulation. These NETs act as autoantigen reservoirs, forming pathogenic NET–ICs that amplify autoimmunity. Oxidative stress (via NADPH oxidase) and various mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) promote NETosis; antioxidants (both enzymatic and non-enzymatic) can inhibit NET formation by scavenging ROS or blocking NADPH oxidase. Preclinical studies show that curcumin, resveratrol, and mitochondrial-targeted MitoQ reduce NETs and lupus nephritis; clinical trials confirm that curcumin and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) lower SLE activity and proteinuria, supporting their potential as safe adjuvant therapies. However, high-dose vitamin E may exacerbate autoimmunity. Future research should clarify NET mechanisms in SLE and optimize antioxidant therapies (e.g., bioavailability, safe dosage and long-term safety).

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Formation Mechanisms of NETs

2.1. Definition and Structure of NETs

2.2. Formation Process of NETs

2.2.1. ROS: Central Regulator of Chromatin Decondensation and NET Extrusion

2.2.2. NADPH Oxidase: Rate-Limiting Step in ROS Production and NETosis

2.2.3. MPO and Neutrophil Elastase: Synergistic Drivers of Chromatin Remodeling

2.3. Physiological Functions of NETs

3. Role of NETs in SLE

3.1. Immunopathological Mechanisms of SLE

3.2. Abnormalities of NETs in SLE: Overproduction, Impaired Clearance, and Autoantigen Function

3.2.1. Excessive NET Formation: LDG-Driven Pathogenesis

3.2.2. Impaired NET Clearance: DNase and Complement Defects

3.2.3. NETs as Autoantigen Reservoirs: NET–IC Formation

3.3. Pathological Roles of NETs in SLE

4. Role of Oxidative Stress in NET Formation and SLE

4.1. Definition and Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress

4.2. SLE-Specific Oxidative Stress Amplification

5. Potential Applications of Antioxidants in NETs and SLE

5.1. Classification and Mechanisms of Action of Antioxidants

5.2. Effects of Antioxidants on NET Formation

5.3. Potential Applications of Antioxidants in SLE Therapy

| Antioxidants | Category | Model | Dosage | Results | Reference |

| Curcumin | preclinical study | female MRL/lpr mice | 200 mg/kg/day | Curcumin effectively reduces proteinuria, renal inflammation, serum anti-dsDNA levels, and spleen size, and inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation both in vivo and in vitro. | Zhao et al. ,2019 [172] |

| preclinical study | MRL/lpr mice and R848-treated mice | 50 mg/kg/day | Curcumin effectively reduces renal inflammation in lupus mouse models by inhibiting neutrophil migration and the release of inflammatory factors via the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway. | Yang et al.,2024 [173] |

|

| Resveratrol | preclinical study | pristane-induced lupus mice | 50 mg/kg/day; 75 mg/kg/day |

Resveratrol significantly mitigates proteinuria, kidney immunoglobulin deposition, and glomerulonephritis in pristane-induced lupus mice, while also suppressing CD4+ T cell activation and proliferation, inducing CD4+ T cell apoptosis, and inhibiting B cell antibody production and proliferation in vitro. | Wang et al.,2014 [174] |

| preclinical study | MRL/lpr mice | 20 mg /kg/day | Resveratrol alleviates lupus symptoms in MRL/lpr mice by enhancing FcγRIIB expression in B cells via Sirt1 activation, reducing plasma cells and autoantibodies, and improving nephritis and survival. | Jhou et al.,2017 [175] |

|

| preclinical study | pristane-induced lupus mice | 25 mg/kg/day; 50 mg/kg/day |

In a pristane-induced SLE murine model, low-dose resveratrol combined with piperine and high-dose resveratrol reduced renal immunoglobulin deposition, hepatic lipogranuloma formation, and pulmonary inflammation, reduced oxidative stress, and improved lupus symptoms, but did not affect autoantibody formation or spleen/skin manifestations. | Pannu et al.,2020 [176] |

|

| preclinical study | pristane-induced lupus mice | 25 mg/kg/day | Resveratrol alone and in combination with piperine effectively mitigated oxidative stress and inflammation, improved renal function, and reduced histopathological manifestations in a pristane-induced lupus murine model. Still, neither treatment regulated autoantibody formation, and piperine did not enhance resveratrol's efficacy. | Pannu et al.,2020 [177] |

|

| Vitamins C | preclinical study | peripheral blood neutrophils isolated from patients with active SLE | 10 mM/day | Vitamin C inhibits NETosis in SLE neutrophils by targeting the REDD1/autophagy/NET axis, reducing thromboinflammation and fibrosis. | Frangou et al.,2018 [178] |

| preclinical study | Gulo-/- mice | 200 mg/kg/day | Vitamin C reduces NETosis in sepsis by attenuating ER stress, autophagy, histone citrullination, and NFκB activation. | Mohammed et al.,2013 [179] |

|

| Vitamins E | preclinical study | hydralazine-induced lupus mice | 25 mg/kg/day; 50 mg/kg/day |

Vitamin E, particularly at a higher dose (50 mg/kg), shows potential in reducing lymphocyte hydrogen peroxide radicals in a hydralazine-induced lupus mouse model. | Githaiga et al.,2023 [180] |

| preclinical study | MRL/lymphoproliferative lpr female mice | 50 mg/kg/day; 250 mg/kg/day; 375 mg/kg/day; 500 mg/kg/day | Low-dose vitamin E extends lifespan in MRL/lpr mice, whereas high-dose vitamin E increases Th2 cytokines and autoantibodies, potentially worsening Th2-driven autoimmune diseases like SLE. | Hsieh et al.,2005 181] | |

| Coenzyme Q10 | preclinical study | MRL/lpr mice | 1 mg/kg; 1.5 mg/kg | Coenzyme Q10 significantly reduces mortality, attenuates disease features, and improves mitochondrial function, renal function, and inflammation in lupus mouse models, supporting its potential therapeutic role in SLE. | Blanco et al.,2020 [182] |

| preclinical study | MRL/lpr mice | MitoQ (200 µM) in drinking water/day | MitoQ reduces neutrophil ROS and NET formation, MAVS oligomerisation, and serum IFN-I in lupus-prone MRL-lpr mice, highlighting the potential of targeting mROS as an adjunct therapy for lupus. | Fortner et al.,2020 [183] | |

| Curcumin | clinical trial | 24 patients with relapsing or refractory biopsy-proven lupus nephritis | 1,500 mg/day | Short-term curcumin supplementation significantly reduced proteinuria, hematuria, and systolic blood pressure in patients with relapsing or refractory lupus nephritis. | Khajehdehi et al.,2012 [185] |

| clinical trial | 70 SLE patients | 1,000 mg/day | Curcumin supplementation significantly reduced anti-dsDNA and IL-6 levels in SLE patients, with no significant changes in other variables. | Sedighi et al.,2024 [186] | |

| clinical trial | SLE active (SLEDAI > 3) with levels of 25(OH)D3 ≤ 30 ng/ml SLE patients | 1,200 IU/day | Curcumin combined with vitamin D3 showed no significant effects on SLEDAI and serum levels of IL-6 and TGF-β1 in SLE patients with low vitamin D levels. However, decreased IL-6 levels correlated positively with reductions in SLEDAI. | Singgih et al.,2017 [187] | |

| N-acetylcysteine | clinical trial | 80 SLE patients | 1,800 mg/day | NAC (1800 mg/day) significantly reduced SLE disease activity and complications, as evidenced by lower BILAG and SLEDAI scores and improved CH50 levels after 3 months, with no adverse events reported. | Abbasifard et al.,2023 [188] |

| clinical trial | female SLE patients | 1,200 mg/day | NAC treatment in early-stage lupus nephritis led to increased glutathione levels, decreased lipid peroxidation biomarker levels, and significant improvements in routine blood counts, 24-h urine protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and SLE disease activity index. | Li et al.,2015 [189] | |

| clinical trial | 36 SLE patients | 1.2 mg/day; 2.4 mg/day; 4.8 mg/day | NAC at 2.4 and 4.8 mg/day significantly reduced SLE activity scores and fatigue levels, while improving mitochondrial function, reducing mTOR activity, enhancing apoptosis, and decreasing anti-dsDNA antibody production in SLE patients. | Lai et al.,2012 [190] | |

| clinical trial | 49 SLE patients and 46 healthy control subjects | 2.4 mg/day; 4.8 mg/day | NAC treatment at dosages of 2.4 and 4.8 mg/day significantly reduced ADHD symptoms in SLE patients, as indicated by lower ASRS total and part A scores, demonstrating its efficacy in improving cognitive and inattentive aspects of ADHD in this patient group. | Garcia et al.,2013 [192] | |

| clinical trial | 69 SLE patients and 37 healthy donors | 3 mg/day | NAC treatment effectively reduced oxygen consumption via mitochondrial ETC complex I and hydrogen peroxide levels in peripheral blood lymphocytes from SLE patients, indicating its potential therapeutic efficacy in reducing oxidative stress. | Doherty et al.,2014 [196] | |

| Vitamins E | clinical trial | 12 SLE patients | 150-300 mg/day | Vitamin E can suppress autoantibody production in SLE patients, as indicated by lower anti-dsDNA antibody titers, independent of its antioxidant activity. | Maeshima et al.,2007 [195] |

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| •O2− | superoxide anion radicals |

| •OH | hydroxyl radicals |

| 4-HNE | 4-hydroxynonenal |

| 8-OHdG | 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine |

| ABCs | age-associated B cells |

| ADHD | attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| ANA | antinuclear antibodies |

| anti-dsDNA | anti-double-stranded DNA |

| anti-Sm | anti-Smith |

| anti-β2-GPI | anti-β2-glycoprotein I |

| ASRS | ADHD Self-Report Scale |

| BCRs | B-cell receptors |

| BILAG | British Isles Lupus Assessment Group |

| C1q | complement component 1q |

| Ca²⁺ | calcium |

| cDCs | conventional dendritic cells |

| CitH3 | citrullinated histone H3 |

| DAH | diffuse alveolar hemorrhage |

| DAMP | damage-associated molecular pattern |

| DCs | dendritic cells |

| DNase1L3 | Deoxyribonuclease 1-like 3 |

| DPI | diphenylene iodonium |

| EndMT | endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| FcγRs | Fcγ receptors |

| GPx | glutathione peroxidase |

| GSDMD | gasdermin D |

| GSH | glutathione |

| Gsr | glutathione reductase |

| H2 | hydrogen gas |

| H2O2 | hydrogen peroxide |

| HDNs | normal-density neutrophils |

| HIF-1α | hypoxia-inducible factor-1α |

| HMGB1 | high-mobility group box 1 |

| HOCl | hypochlorous acid |

| ICs | immune complexes |

| IFNs | interferons |

| IL-17 | interleukin-17 |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1β |

| IL-21 | interleukin-21 |

| IL-33 | interleukin-33 |

| LDGs | low-density granulocytes |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| MitoQ | mitochondrial-targeted coenzyme Q10 |

| MMPs | matrix metalloproteinases |

| MPO | myeloperoxidase |

| mtDNA | mitochondrial DNA |

| mTOR | mammalian target of rapamycin |

| mtROS | mitochondrial reactive oxygen species |

| NAC | N-acetylcysteine |

| NADPH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NETs | neutrophil extracellular traps |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor-kappa B |

| NLRP3 | NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| ONOO− | peroxynitrite |

| PAD4 | peptidylarginine deiminase 4 |

| PAR4 | protease-activated receptor 4 |

| pDCs | plasmacytoid dendritic cells |

| PKC | protein kinase C |

| PMA | phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate |

| PRKCD | protein kinase C delta |

| PRRs | pattern recognition receptors |

| REDD1 | regulated in development and DNA damage response 1 |

| RNS | reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SCN- | thiocyanate |

| SeCN- | selenocyanate |

| SLE | systemic lupus erythematosus |

| SLEDAI | SLE Disease Activity Index |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| Tfh | T follicular helper cells |

| TFPI | tissue factor pathway inhibitor |

| TGF-β1 | transforming growth factor-β1 |

| TLR7 | toll-like receptor 7 |

| TLR9 | toll-like receptor 9 |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| Tph | T peripheral helper cells |

References

- Shiozawa, S. Pathogenesis of Autoimmunity/Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE). Cells 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekvig, O.P. SLE classification criteria: Science-based icons or algorithmic distractions - an intellectually demanding dilemma. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1011591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Zhang, X. Genetic susceptibility to SLE: recent progress from GWAS. J Autoimmun 2013, 41, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robl, R.; Eudy, A.; Bachali, P.S.; Rogers, J.L.; Clowse, M.; Pisetsky, D.; Lipsky, P. Molecular endotypes of type 1 and type 2 SLE. Lupus Sci Med 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaniv, G.; Twig, G.; Shor, D.B.; Furer, A.; Sherer, Y.; Mozes, O.; Komisar, O.; Slonimsky, E.; Klang, E.; Lotan, E.; et al. A volcanic explosion of autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus: a diversity of 180 different antibodies found in SLE patients. Autoimmun Rev 2015, 14, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, P.E.; Santoro, S.A. Antiphospholipid antibodies: anticardiolipin and the lupus anticoagulant in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and in non-SLE disorders. Prevalence and clinical significance. Ann Intern Med 1990, 112, 682–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Hao, Y.J.; Zhang, Z.L. Systemic lupus erythematosus: year in review 2019. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020, 133, 2189–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew, P.X.; Kubes, P. The Neutrophil's Role During Health and Disease. Physiol Rev 2019, 99, 1223–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, S.; Xue, K.; Wang, G. Neutrophils in neutrophilic dermatoses: Emerging roles and promising targeted therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022, 149, 1203–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, V.; Reichard, U.; Goosmann, C.; Fauler, B.; Uhlemann, Y.; Weiss, D.S.; Weinrauch, Y.; Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 2004, 303, 1532–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Shen, J.; Ouyang, J.; Dong, P.; Hong, Y.; Liang, L.; Liu, J. Bibliometric and visual analysis of neutrophil extracellular traps from 2004 to 2022. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1025861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papayannopoulos, V. Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2018, 18, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Wang, X.; Yang, C.; Chen, F.; Shi, L.; Xu, W.; Wang, K.; Liu, B.; Wang, C.; Sun, D.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps drive intestinal microvascular endothelial ferroptosis by impairing Fundc1-dependent mitophagy. Redox Biol 2023, 67, 102906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Kronbichler, A.; Park, D.D.; Park, Y.; Moon, H.; Kim, H.; Choi, J.H.; Choi, Y.; Shim, S.; Lyu, I.S.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in autoimmune diseases: A comprehensive review. Autoimmun Rev 2017, 16, 1160–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, A.; Kim, D.W. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Airway Diseases: Pathological Roles and Therapeutic Implications. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fousert, E.; Toes, R.; Desai, J. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) Take the Central Stage in Driving Autoimmune Responses. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Takeyama, N. Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Health and Disease Pathophysiology: Recent Insights and Advances. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsokos, G.C.; Lo, M.S.; Costa Reis, P.; Sullivan, K.E. New insights into the immunopathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2016, 12, 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Qu, M.; Wang, Y.; Guo, K.; Shen, R.; Sun, Z.; Cata, J.P.; Yang, S.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps mediate m(6)A modification and regulates sepsis-associated acute lung injury by activating ferroptosis in alveolar epithelial cells. Int J Biol Sci 2022, 18, 3337–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herre, M.; Cedervall, J.; Mackman, N.; Olsson, A.K. Neutrophil extracellular traps in the pathology of cancer and other inflammatory diseases. Physiol Rev 2023, 103, 277–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, J.; Cui, M.; Zhang, Y. Neutrophil extracellular traps and neutrophilic asthma. Respir Med 2025, 245, 108150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Liu, J. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps: A New Player in Cancer Metastasis and Therapeutic Target. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2021, 40, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, A.; Libby, P.; Soehnlein, O.; Aramburu, I.V.; Papayannopoulos, V.; Silvestre-Roig, C. Neutrophil extracellular traps: from physiology to pathology. Cardiovasc Res 2022, 118, 2737–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Du, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L. Composition and Function of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhou, S.; Li, S.; Gong, S.; Zhang, Q. Neutrophil extracellular traps in wound healing. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2024, 45, 1033–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xiao, S.; Filipczak, N.; Yalamarty, S.S.K.; Shang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Q. Role and Therapeutic Targeting Strategies of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Inflammation. Int J Nanomedicine 2023, 18, 5265–5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutua, V.; Gershwin, L.J. A Review of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) in Disease: Potential Anti-NETs Therapeutics. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2021, 61, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.; Yu, H.; Yang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Bai, X.; Wang, R.; Cao, Y.; Xu, H.; Luo, H.; Lu, L.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps released by neutrophils impair revascularization and vascular remodeling after stroke. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Gao, R.; Chen, H.; Hu, J.; Zhang, P.; Wei, X.; Shi, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; et al. Myocardial reperfusion injury exacerbation due to ALDH2 deficiency is mediated by neutrophil extracellular traps and prevented by leukotriene C4 inhibition. Eur Heart J 2024, 45, 1662–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, D.; Mao, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y. The emerging role of neutrophil extracellular traps in ulcerative colitis. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1425251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzouz, D.; Palaniyar, N. How Do ROS Induce NETosis? Oxidative DNA Damage, DNA Repair, and Chromatin Decondensation. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan Dunn, J.; Alvarez, L.A.; Zhang, X.; Soldati, T. Reactive oxygen species and mitochondria: A nexus of cellular homeostasis. Redox Biol 2015, 6, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Song, C.; Ding, S.; Zuo, Y.; Yi, K.; Li, N.; Wang, B.; Geng, Q. Crosstalk between neutrophil extracellular traps and immune regulation: insights into pathobiology and therapeutic implications of transfusion-related acute lung injury. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1324021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönrich, G.; Raftery, M.J.; Samstag, Y. Devilishly radical NETwork in COVID-19: Oxidative stress, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), and T cell suppression. Adv Biol Regul 2020, 77, 100741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, L.; Yan, X.; Zhang, H. Mitochondrial DNA-activated cGAS-STING pathway in cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2025, 1880, 189249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Hong, W.; Wan, M.; Zheng, L. Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic target of NETosis in diseases. MedComm (2020) 2022, 3, e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobjeva, N.V.; Chernyak, B.V. NETosis: Molecular Mechanisms, Role in Physiology and Pathology. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2020, 85, 1178–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, X.M.; Reichner, J.S. Neutrophil Integrins and Matrix Ligands and NET Release. Front Immunol 2016, 7, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralda, I.; Uriarte, S.M.; McLeish, K.R. Multiple Phenotypic Changes Define Neutrophil Priming. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017, 7, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.Y.; Miralda, I.; Armstrong, C.L.; Uriarte, S.M.; Bagaitkar, J. The roles of NADPH oxidase in modulating neutrophil effector responses. Mol Oral Microbiol 2019, 34, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G.T.; Green, E.R.; Mecsas, J. Neutrophils to the ROScue: Mechanisms of NADPH Oxidase Activation and Bacterial Resistance. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017, 7, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, S.; Nakazawa, D.; Shida, H.; Miyoshi, A.; Kusunoki, Y.; Tomaru, U.; Ishizu, A. NETosis markers: Quest for specific, objective, and quantitative markers. Clin Chim Acta 2016, 459, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demkow, U. Molecular Mechanisms of Neutrophil Extracellular Trap (NETs) Degradation. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaño, M.; Tomás-Pérez, S.; González-Cantó, E.; Aghababyan, C.; Mascarós-Martínez, A.; Santonja, N.; Herreros-Pomares, A.; Oto, J.; Medina, P.; Götte, M.; et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Cancer: Trapping Our Attention with Their Involvement in Ovarian Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Kim, S.J.; Lei, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Huang, H.; Zhang, H.; Tsung, A. Neutrophil extracellular traps in homeostasis and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, Y.; Soehnlein, O.; Weber, C. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Atherosclerosis and Atherothrombosis. Circ Res 2017, 120, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frade-Sosa, B.; Sanmartí, R. Neutrophils, neutrophil extracellular traps, and rheumatoid arthritis: An updated review for clinicians. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed) 2023, 19, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Stehr, A.M.; Naschberger, E.; Knopf, J.; Herrmann, M.; Stürzl, M. No NETs no TIME: Crosstalk between neutrophil extracellular traps and the tumor immune microenvironment. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1075260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuchi, M.; Miyabe, Y.; Furutani, C.; Saga, T.; Moritoki, Y.; Yamada, T.; Weller, P.F.; Ueki, S. How to detect eosinophil ETosis (EETosis) and extracellular traps. Allergol Int 2021, 70, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Rizo, V.; Martínez-Guzmán, M.A.; Iñiguez-Gutierrez, L.; García-Orozco, A.; Alvarado-Navarro, A.; Fafutis-Morris, M. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Its Implications in Inflammation: An Overview. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borregaard, N. Neutrophils, from marrow to microbes. Immunity 2010, 33, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, M.; Kubes, P. Neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps in the liver and gastrointestinal system. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 15, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, D.; Masuda, S.; Nishibata, Y.; Watanabe-Kusunoki, K.; Tomaru, U.; Ishizu, A. Neutrophils and NETs in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2025, 21, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manda, A.; Pruchniak, M.P.; Araźna, M.; Demkow, U.A. Neutrophil extracellular traps in physiology and pathology. Cent Eur J Immunol 2014, 39, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, V.; Peyneau, M.; Chollet-Martin, S.; de Chaisemartin, L. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Autoimmunity and Allergy: Immune Complexes at Work. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poto, R.; Shamji, M.; Marone, G.; Durham, S.R.; Scadding, G.W.; Varricchi, G. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Asthma: Friends or Foes? Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaoka, I.; Tamura, H.; Reich, J. Therapeutic Potential of Cathelicidin Peptide LL-37, an Antimicrobial Agent, in a Murine Sepsis Model. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, J.; Knopf, J.; Maueröder, C.; Kienhöfer, D.; Leppkes, M.; Herrmann, M. Neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps orchestrate initiation and resolution of inflammation. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016, 34, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Palomino-Segura, M.; Sicilia, J.; Ballesteros, I.; Hidalgo, A. Strategies of neutrophil diversification. Nat Immunol 2023, 24, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiriakidou, M.; Ching, C.L. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ann Intern Med 2020, 172, Itc81–itc96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Nagafuchi, Y.; Fujio, K. Clinical and Immunological Biomarkers for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchi, D.; Elefante, E.; Schilirò, D.; Signorini, V.; Trentin, F.; Bortoluzzi, A.; Tani, C. One year in review 2022: systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2022, 40, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piga, M.; Tselios, K.; Viveiros, L.; Chessa, E.; Neves, A.; Urowitz, M.B.; Isenberg, D. Clinical patterns of disease: From early systemic lupus erythematosus to late-onset disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2023, 37, 101938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillatreau, S.; Manfroi, B.; Dörner, T. Toll-like receptor signalling in B cells during systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2021, 17, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.; Zhang, B.; Wu, X.; Liu, R.; Fan, H.; Han, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, X.; Chu, C.Q.; Shi, X. Toll-like receptors 7 and 9 regulate the proliferation and differentiation of B cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1093208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durcan, L.; O'Dwyer, T.; Petri, M. Management strategies and future directions for systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. Lancet 2019, 393, 2332–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, X. Systemic lupus erythematosus: updated insights on the pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2025, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gergianaki, I.; Bortoluzzi, A.; Bertsias, G. Update on the epidemiology, risk factors, and disease outcomes of systemic lupus erythematosus. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2018, 32, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accapezzato, D.; Caccavale, R.; Paroli, M.P.; Gioia, C.; Nguyen, B.L.; Spadea, L.; Paroli, M. Advances in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Lu, M.P.; Wang, J.H.; Xu, M.; Yang, S.R. Immunological pathogenesis and treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. World J Pediatr 2020, 16, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusseau, M.; Khaldi-Plassart, S.; Cognard, J.; Viel, S.; Khoryati, L.; Benezech, S.; Mathieu, A.L.; Rieux-Laucat, F.; Bader-Meunier, B.; Belot, A. Mendelian Causes of Autoimmunity: the Lupus Phenotype. J Clin Immunol 2024, 44, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, A.; Wenzel, J.; Bijl, M. Lupus erythematosus revisited. Semin Immunopathol 2016, 38, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherlinger, M.; Guillotin, V.; Truchetet, M.E.; Contin-Bordes, C.; Sisirak, V.; Duffau, P.; Lazaro, E.; Richez, C.; Blanco, P. Systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis: All roads lead to platelets. Autoimmun Rev 2018, 17, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilland, B.; Scherlinger, M.; Khoryati, L.; Goret, J.; Duffau, P.; Lazaro, E.; Charrier, M.; Guillotin, V.; Richez, C.; Blanco, P. Platelets and IgE: Shaping the Innate Immune Response in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2020, 58, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttaris, V.C.; Juang, Y.T.; Tsokos, G.C. Immune cells and cytokines in systemic lupus erythematosus: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2005, 17, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, P.; Kaplan, M.J. Cell death in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Clin Immunol 2017, 185, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marian, V.; Anolik, J.H. Treatment targets in systemic lupus erythematosus: biology and clinical perspective. Arthritis Res Ther 2012, 14 Suppl 4, S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aringer, M. Inflammatory markers in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun 2020, 110, 102374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gensous, N.; Schmitt, N.; Richez, C.; Ueno, H.; Blanco, P. T follicular helper cells, interleukin-21 and systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017, 56, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, H.S.; Leung, B.P.L. Anti-Cytokine Autoantibodies in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Cells 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, J.O.; Euler, H.H. Recognition and management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Drugs 1997, 54, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Bañuelos, E.; Fava, A.; Andrade, F. An update on autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2023, 35, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresneda Alarcon, M.; McLaren, Z.; Wright, H.L. Neutrophils in the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Same Foe Different M.O. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 649693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, A.; Buskiewicz-Koenig, I.A. Redox Activation of Mitochondrial DAMPs and the Metabolic Consequences for Development of Autoimmunity. Antioxid Redox Signal 2022, 36, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Shen, J.; Ran, Z. Emerging views of mitophagy in immunity and autoimmune diseases. Autophagy 2020, 16, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.H.; Wu, D.W.; Huang, C.Y.; Hung, L.F.; Wu, C.H.; Ka, S.M.; Chen, A.; Huang, J.L.; Ho, L.J. Induction of LY6E regulates interleukin-1β production, potentially contributing to the immunopathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Cell Commun Signal 2025, 23, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.; Tian, Y.; Bai, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, J.; Jin, M.; Zhu, J.; Li, X. Increased oxidative stress contributes to impaired peripheral CD56(dim)CD57(+) NK cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 2022, 24, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malamud, M.; Whitehead, L.; McIntosh, A.; Colella, F.; Roelofs, A.J.; Kusakabe, T.; Dambuza, I.M.; Phillips-Brookes, A.; Salazar, F.; Perez, F.; et al. Recognition and control of neutrophil extracellular trap formation by MICL. Nature 2024, 633, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, J.; Hennen, E.M.; Ao, M.; Kirabo, A.; Ahmad, T.; de la Visitación, N.; Patrick, D.M. NETosis Drives Blood Pressure Elevation and Vascular Dysfunction in Hypertension. Circ Res 2024, 134, 1483–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katarzyna, P.B.; Wiktor, S.; Ewa, D.; Piotr, L. Current treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: a clinician's perspective. Rheumatol Int 2023, 43, 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabach, P.R.; Sims, D.; Gomez-Bañuelos, E.; Zehentmeier, S.; Dammen-Brower, K.; Bernhisel, A.; Kujawski, S.; Lopez, S.G.; Petri, M.; Goldman, D.W.; et al. A dual-acting DNASE1/DNASE1L3 biologic prevents autoimmunity and death in genetic and induced lupus models. JCI Insight 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruschi, M.; Bonanni, A.; Petretto, A.; Vaglio, A.; Pratesi, F.; Santucci, L.; Migliorini, P.; Bertelli, R.; Galetti, M.; Belletti, S.; et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Profiles in Patients with Incident Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Lupus Nephritis. J Rheumatol 2020, 47, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korn, M.A.; Steffensen, M.; Brandl, C.; Royzman, D.; Daniel, C.; Winkler, T.H.; Nitschke, L. Epistatic effects of Siglec-G and DNase1 or DNase1l3 deficiencies in the development of systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1095830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.C.; Chan, R.W.Y.; Peng, W.; Huang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, X.; Volpi, S.; Hiraki, L.T.; Vaglio, A.; Fenaroli, P.; et al. Jagged Ends on Multinucleosomal Cell-Free DNA Serve as a Biomarker for Nuclease Activity and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Clin Chem 2022, 68, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engavale, M.; Hernandez, C.J.; Infante, A.; LeRoith, T.; Radovan, E.; Evans, L.; Villarreal, J.; Reilly, C.M.; Sutton, R.B.; Keyel, P.A. Deficiency of macrophage-derived Dnase1L3 causes lupus-like phenotypes in mice. J Leukoc Biol 2023, 114, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Ma, M.L.; Chan, R.W.Y.; Lam, W.K.J.; Peng, W.; Gai, W.; Hu, X.; Ding, S.C.; Ji, L.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Fragmentation landscape of cell-free DNA revealed by deconvolutional analysis of end motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2220982120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasdemir, S.; Yildiz, M.; Celebi, D.; Sahin, S.; Aliyeva, N.; Haslak, F.; Gunalp, A.; Adrovic, A.; Barut, K.; Artim Esen, B.; et al. Genetic screening of early-onset patients with systemic lupus erythematosus by a targeted next-generation sequencing gene panel. Lupus 2022, 31, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Angarita, A.; Aragón, C.C.; Tobón, G.J. Cathelicidin LL-37: A new important molecule in the pathophysiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Transl Autoimmun 2020, 3, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, K.; Thacker, H.; Chaubey, M.; Rai, M.; Singh, S.; Rawat, S.; Giri, K.; Mohanty, S.; Rai, G. Dexamethasone and IFN-γ primed mesenchymal stem cells conditioned media immunomodulates aberrant NETosis in SLE via PGE2 and IDO. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1461841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameer, M.A.; Chaudhry, H.; Mushtaq, J.; Khan, O.S.; Babar, M.; Hashim, T.; Zeb, S.; Tariq, M.A.; Patlolla, S.R.; Ali, J.; et al. An Overview of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) Pathogenesis, Classification, and Management. Cureus 2022, 14, e30330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Xie, Y.; Dang, R.N.; Yu, J.; Tian, X.X.; Li, L.J.; Zhou, Q.M.; An, X.M.; Chen, P.L.; Luo, Y.Q.; et al. Activation of IRF2 signaling networks facilitates podocyte pyroptosis in lupus nephritis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2025, 1871, 167990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinico, R.A.; Bollini, B.; Sabadini, E.; Di Toma, L.; Radice, A. The use of laboratory tests in diagnosis and monitoring of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Nephrol 2002, 15 Suppl 6, S20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J.S.; Subramanian, V.; O'Dell, A.A.; Yalavarthi, S.; Zhao, W.; Smith, C.K.; Hodgin, J.B.; Thompson, P.R.; Kaplan, M.J. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition disrupts NET formation and protects against kidney, skin and vascular disease in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice. Ann Rheum Dis 2015, 74, 2199–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dömer, D.; Walther, T.; Möller, S.; Behnen, M.; Laskay, T. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Activate Proinflammatory Functions of Human Neutrophils. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 636954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Dehnavi, S.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Johnston, T.P.; Sahebkar, A. Neutrophil extracellular trap: A key player in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. Int Immunopharmacol 2023, 116, 109843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melbouci, D.; Haidar Ahmad, A.; Decker, P. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NET): not only antimicrobial but also modulators of innate and adaptive immunities in inflammatory autoimmune diseases. RMD Open 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, P.; Kral-Pointner, J.B.; Mayer, J.; Richter, M.; Kaun, C.; Brostjan, C.; Eilenberg, W.; Fischer, M.B.; Speidl, W.S.; Hengstenberg, C.; et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Degradation by Differently Polarized Macrophage Subsets. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2020, 40, 2265–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabi, T.Z.; Fawzy, N.A.; Abdul Rab, S.; Alabdul Razzak, G.; Sabbah, B.N.; Alkattan, K.; Tleyjeh, I.; Yaqinuddin, A. NETs, infections, and antimicrobials: a complex interplay. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2023, 27, 9559–9568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, P.; Nakabo, S.; O'Neil, L.; Goel, R.R.; Jiang, K.; Carmona-Rivera, C.; Gupta, S.; Chan, D.W.; Carlucci, P.M.; Wang, X.; et al. Transcriptomic, epigenetic, and functional analyses implicate neutrophil diversity in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 25222–25228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, X.; Chatterjee, V.; Meegan, J.E.; Beard, R.S., Jr.; Yuan, S.Y. Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Vesicles in Regulating Vascular Endothelial Permeability. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meegan, J.E.; Yang, X.; Coleman, D.C.; Jannaway, M.; Yuan, S.Y. Neutrophil-mediated vascular barrier injury: Role of neutrophil extracellular traps. Microcirculation 2017, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Yalavarthi, S.; Tambralli, A.; Zeng, L.; Rysenga, C.E.; Alizadeh, N.; Hudgins, L.; Liang, W.; NaveenKumar, S.K.; Shi, H.; et al. Inhibition of neutrophil extracellular trap formation alleviates vascular dysfunction in type 1 diabetic mice. Sci Adv 2023, 9, eadj1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; de Leeuw, K.; van Goor, H.; Doornbos-van der Meer, B.; Arends, S.; Westra, J. Neutrophil extracellular traps and oxidative stress in systemic lupus erythematosus patients with and without renal involvement. Arthritis Res Ther 2024, 26, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juha, M.; Molnár, A.; Jakus, Z.; Ledó, N. NETosis: an emerging therapeutic target in renal diseases. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1253667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrot, P.A.; Tellier, E.; Plantureux, L.; Crescence, L.; Robert, S.; Chareyre, C.; Daniel, L.; Secq, V.; Garcia, S.; Dignat-George, F.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps are associated with the pathogenesis of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in murine lupus. J Autoimmun 2019, 100, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, A.N.; Kazzaz, N.M.; Knight, J.S. Do neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to the heightened risk of thrombosis in inflammatory diseases? World J Cardiol 2015, 7, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucoloto, A.Z.; Jenne, C.N. Platelet-Neutrophil Interplay: Insights Into Neutrophil Extracellular Trap (NET)-Driven Coagulation in Infection. Front Cardiovasc Med 2019, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, W.; Tong, X.; Xia, R.; Fan, J.; Du, J.; Zhang, C.; Shi, X. Platelet-derived exosomes promote neutrophil extracellular trap formation during septic shock. Crit Care 2020, 24, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Oxidative stress: a concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol 2015, 4, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filomeni, G.; De Zio, D.; Cecconi, F. Oxidative stress and autophagy: the clash between damage and metabolic needs. Cell Death Differ 2015, 22, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.P. Radical-free biology of oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2008, 295, C849–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hybertson, B.M.; Gao, B.; Bose, S.K.; McCord, J.M. Oxidative stress in health and disease: the therapeutic potential of Nrf2 activation. Mol Aspects Med 2011, 32, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrini, C.; Harris, I.S.; Mak, T.W. Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2013, 12, 931–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Zglinicki, T. Oxidative stress and cell senescence as drivers of ageing: Chicken and egg. Ageing Res Rev 2024, 102, 102558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Cao, T.; Chen, E.; Li, Y.; Lei, W.; Hu, Y.; He, B.; Liu, S. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Oxidative Stress in Inflammatory Diseases. DNA Cell Biol 2022, 41, 924–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, N.; Thakur, M.; Pareek, V.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, S.; Datusalia, A.K. Oxidative Stress: Major Threat in Traumatic Brain Injury. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2018, 17, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello-Verrugio, C.; Simon, F.; Trollet, C.; Santibañez, J.F. Oxidative Stress in Disease and Aging: Mechanisms and Therapies 2016. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017, 4310469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.L.; Norhaizan, M.E.; Liew, W.P. Nutrients and Oxidative Stress: Friend or Foe? Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018, 2018, 9719584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Hu, H.; Liu, H.; Zhong, C.; Wu, B.; Lv, C.; Tian, Y. Lipotoxicity, lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis: a dilemma in cancer therapy. Cell Biol Toxicol 2025, 41, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramana, K.V.; Srivastava, S.; Singhal, S.S. Lipid peroxidation products in human health and disease 2014. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2014, 2014, 162414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadtman, E.R.; Berlett, B.S. Reactive oxygen-mediated protein oxidation in aging and disease. Drug Metab Rev 1998, 30, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, M.S.; Evans, M.D.; Dizdaroglu, M.; Lunec, J. Oxidative DNA damage: mechanisms, mutation, and disease. Faseb j 2003, 17, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, S.; Frenis, K.; Oelze, M.; Kalinovic, S.; Kuntic, M.; Bayo Jimenez, M.T.; Vujacic-Mirski, K.; Helmstädter, J.; Kröller-Schön, S.; Münzel, T.; et al. Vascular Inflammation and Oxidative Stress: Major Triggers for Cardiovascular Disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019, 2019, 7092151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupu, A.; Stoleriu, G.; Nedelcu, A.H.; Perju, S.N.; Gavrilovici, C.; Baciu, G.; Mihai, C.M.; Chisnoiu, T.; Morariu, I.D.; Grigore, E.; et al. Overview of Oxidative Stress in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Antioxidants (Basel) 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Chen, Q.; Xia, Y. Oxidative Stress Contributes to Inflammatory and Cellular Damage in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Cellular Markers and Molecular Mechanism. J Inflamm Res 2023, 16, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Meng, X.; Wancket, L.M.; Lintner, K.; Nelin, L.D.; Chen, B.; Francis, K.P.; Smith, C.V.; Rogers, L.K.; Liu, Y. Glutathione reductase facilitates host defense by sustaining phagocytic oxidative burst and promoting the development of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Immunol 2012, 188, 2316–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazdani, H.O.; Roy, E.; Comerci, A.J.; van der Windt, D.J.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H.; Loughran, P.; Shiva, S.; Geller, D.A.; Bartlett, D.L.; et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Drive Mitochondrial Homeostasis in Tumors to Augment Growth. Cancer Res 2019, 79, 5626–5639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermert, D.; Urban, C.F.; Laube, B.; Goosmann, C.; Zychlinsky, A.; Brinkmann, V. Mouse neutrophil extracellular traps in microbial infections. J Innate Immun 2009, 1, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkim, A.; Fuchs, T.A.; Martinez, N.E.; Hess, S.; Prinz, H.; Zychlinsky, A.; Waldmann, H. Activation of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway is required for neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Nat Chem Biol 2011, 7, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Gupta, R.; Blanco, L.P.; Yang, S.; Shteinfer-Kuzmine, A.; Wang, K.; Zhu, J.; Yoon, H.E.; Wang, X.; Kerkhofs, M.; et al. VDAC oligomers form mitochondrial pores to release mtDNA fragments and promote lupus-like disease. Science 2019, 366, 1531–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T.A.; Abed, U.; Goosmann, C.; Hurwitz, R.; Schulze, I.; Wahn, V.; Weinrauch, Y.; Brinkmann, V.; Zychlinsky, A. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol 2007, 176, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campillo-Navarro, M.; Leyva-Paredes, K.; Donis-Maturano, L.; Rodríguez-López, G.M.; Soria-Castro, R.; García-Pérez, B.E.; Puebla-Osorio, N.; Ullrich, S.E.; Luna-Herrera, J.; Flores-Romo, L.; et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Catalase Inhibits the Formation of Mast Cell Extracellular Traps. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douda, D.N.; Khan, M.A.; Grasemann, H.; Palaniyar, N. SK3 channel and mitochondrial ROS mediate NADPH oxidase-independent NETosis induced by calcium influx. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 2817–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzouz, D.; Palaniyar, N. ROS and DNA repair in spontaneous versus agonist-induced NETosis: Context matters. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1033815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, J.; Lee, M.G. Oxidative stress and antioxidant strategies in dermatology. Redox Rep 2016, 21, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Prior, R.L. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. J Agric Food Chem 2005, 53, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokhina, O.; Virolainen, E.; Fagerstedt, K.V. Antioxidants, oxidative damage and oxygen deprivation stress: a review. Ann Bot 2003, 91 Spec No, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; He, T.; Farrar, S.; Ji, L.; Liu, T.; Ma, X. Antioxidants Maintain Cellular Redox Homeostasis by Elimination of Reactive Oxygen Species. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017, 44, 532–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, M.; Gambino, S.; Romanelli, M.G.; Donadelli, M.; Scupoli, M.T. Browsing the oldest antioxidant enzyme: catalase and its multiple regulation in cancer. Free Radic Biol Med 2021, 172, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Pop, A. The role of antioxidants in the chemistry of oxidative stress: A review. Eur J Med Chem 2015, 97, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogacka, A.; Sobczak-Czynsz, A.; Balejko, E.; Heberlej, A.; Ciechanowski, K. Effect of Diet and Supplementation on Serum Vitamin C Concentration and Antioxidant Activity in Dialysis Patients. Nutrients 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coskun, M.; Kayis, T.; Gulsu, E.; Alp, E. Effects of Selenium and Vitamin E on Enzymatic, Biochemical, and Immunological Biomarkers in Galleria mellonella L. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 9953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Averill-Bates, D.A. The antioxidant glutathione. Vitam Horm 2023, 121, 109–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Yang, D.; Lai, K.; Tu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Ding, W.; Yang, S. Antioxidant Effects of Resveratrol in Intervertebral Disk. J Invest Surg 2022, 35, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, V.P.; Sudheer, A.R. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin. Adv Exp Med Biol 2007, 595, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.D.; Elias, R.J. The antioxidant and pro-oxidant activities of green tea polyphenols: a role in cancer prevention. Arch Biochem Biophys 2010, 501, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tan, H.Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Z.J.; Lao, L.; Wong, C.W.; Feng, Y. The Role of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Liver Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2015, 16, 26087–26124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.A.; Ahmed, H.S.; Hassan, D.F. Free radicals and oxidative stress: Mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Hum Antibodies 2024, 32, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiter, T.; Fragasso, A.; Hartl, D.; Nieß, A.M. Neutrophil extracellular traps: a walk on the wild side of exercise immunology. Sports Med 2015, 45, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, F.; Zychlinsky, A.; Kenny, E.F. The role of neutrophil extracellular traps in rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2018, 14, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abonia, R.; Insuasty, D.; Castillo, J.C.; Laali, K.K. Recent Advances in the Synthesis of Organic Thiocyano (SCN) and Selenocyano (SeCN) Compounds, Their Chemical Transformations and Bioactivity. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulfig, A.; Leichert, L.I. The effects of neutrophil-generated hypochlorous acid and other hypohalous acids on host and pathogens. Cell Mol Life Sci 2021, 78, 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singel, K.L.; Segal, B.H. NOX2-dependent regulation of inflammation. Clin Sci (Lond) 2016, 130, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, Z.A.; Khosrojerdi, A.; Aslani, S.; Hemmatzadeh, M.; Babaie, F.; Bairami, A.; Shomali, N.; Hosseinzadeh, R.; Safari, R.; Mohammadi, H. Multi-facets of neutrophil extracellular trap in infectious diseases: Moving beyond immunity. Microb Pathog 2021, 158, 105066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branzk, N.; Lubojemska, A.; Hardison, S.E.; Wang, Q.; Gutierrez, M.G.; Brown, G.D.; Papayannopoulos, V. Neutrophils sense microbe size and selectively release neutrophil extracellular traps in response to large pathogens. Nat Immunol 2014, 15, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, M.D.; Bottle, S.E.; Fairfull-Smith, K.E.; Malle, E.; Whitelock, J.M.; Davies, M.J. Inhibition of myeloperoxidase-mediated hypochlorous acid production by nitroxides. Biochem J 2009, 421, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Li, S. Roles of selenoprotein S in reactive oxygen species-dependent neutrophil extracellular trap formation induced by selenium-deficient arteritis. Redox Biol 2021, 44, 102003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharkova, O.; Celhar, T.; Cravens, P.D.; Satterthwaite, A.B.; Fairhurst, A.M.; Davis, L.S. Pathways leading to an immunological disease: systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017, 56, i55–i66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poznyak, A.V.; Orekhov, N.A.; Churov, A.V.; Starodubtseva, I.A.; Beloyartsev, D.F.; Kovyanova, T.I.; Sukhorukov, V.N.; Orekhov, A.N. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Insights and Therapeutic Potential. Diseases 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Euler, M.; Hoffmann, M.H. The double-edged role of neutrophil extracellular traps in inflammation. Biochem Soc Trans 2019, 47, 1921–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Yang, T.; Yang, K.; Yu, G.; Li, J.; Xiang, W.; Chen, H. Curcumin and Curcuma longa Extract in the Treatment of 10 Types of Autoimmune Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 31 Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 896476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, M.; Li, M.; Li, M.; Tan, H. Curcumin attenuates murine lupus via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome. Int Immunopharmacol 2019, 69, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, H.; Tian, L.; Guo, P.; Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Sun, L. Curcumin attenuates lupus nephritis by inhibiting neutrophil migration via PI3K/AKT/NF-κB signalling pathway. Lupus Sci Med 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Luo, X.F.; Li, M.T.; Xu, D.; Zhou, S.; Chen, H.Z.; Gao, N.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.L.; Zeng, X.F. Resveratrol possesses protective effects in a pristane-induced lupus mouse model. PLoS One 2014, 9, e114792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhou, J.P.; Chen, S.J.; Huang, H.Y.; Lin, W.W.; Huang, D.Y.; Tzeng, S.J. Upregulation of FcγRIIB by resveratrol via NF-κB activation reduces B-cell numbers and ameliorates lupus. Exp Mol Med 2017, 49, e381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannu, N.; Bhatnagar, A. Combinatorial therapeutic effect of resveratrol and piperine on murine model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Inflammopharmacology 2020, 28, 401–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannu, N.; Bhatnagar, A. Prophylactic effect of resveratrol and piperine on pristane-induced murine model of lupus-like disease. Inflammopharmacology 2020, 28, 719–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangou, E.; Chrysanthopoulou, A.; Mitsios, A.; Kambas, K.; Arelaki, S.; Angelidou, I.; Arampatzioglou, A.; Gakiopoulou, H.; Bertsias, G.K.; Verginis, P.; et al. REDD1/autophagy pathway promotes thromboinflammation and fibrosis in human systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) through NETs decorated with tissue factor (TF) and interleukin-17A (IL-17A). Ann Rheum Dis 2019, 78, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, B.M.; Fisher, B.J.; Kraskauskas, D.; Farkas, D.; Brophy, D.F.; Fowler, A.A., 3rd; Natarajan, R. Vitamin C: a novel regulator of neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3131–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Githaiga, F.M.; Omwenga, G.I.; Ngugi, M.P. In vivo ameliorative effects of vitamin E against hydralazine-induced lupus. Lupus Sci Med 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.C.; Lin, B.F. Opposite effects of low and high dose supplementation of vitamin E on survival of MRL/lpr mice. Nutrition 2005, 21, 940–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, L.P.; Pedersen, H.L.; Wang, X.; Lightfoot, Y.L.; Seto, N.; Carmona-Rivera, C.; Yu, Z.X.; Hoffmann, V.; Yuen, P.S.T.; Kaplan, M.J. Improved Mitochondrial Metabolism and Reduced Inflammation Following Attenuation of Murine Lupus With Coenzyme Q10 Analog Idebenone. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020, 72, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortner, K.A.; Blanco, L.P.; Buskiewicz, I.; Huang, N.; Gibson, P.C.; Cook, D.L.; Pedersen, H.L.; Yuen, P.S.T.; Murphy, M.P.; Perl, A.; et al. Targeting mitochondrial oxidative stress with MitoQ reduces NET formation and kidney disease in lupus-prone MRL-lpr mice. Lupus Sci Med 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainglers, W.; Khamwong, M.; Chareonsudjai, S. N-acetylcysteine inhibits NETs, exhibits antibacterial and antibiofilm properties and enhances neutrophil function against Burkholderia pseudomallei. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 29943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajehdehi, P.; Zanjaninejad, B.; Aflaki, E.; Nazarinia, M.; Azad, F.; Malekmakan, L.; Dehghanzadeh, G.R. Oral supplementation of turmeric decreases proteinuria, hematuria, and systolic blood pressure in patients suffering from relapsing or refractory lupus nephritis: a randomized and placebo-controlled study. J Ren Nutr 2012, 22, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedighi, S.; Faramarzipalangar, Z.; Mohammadi, E.; Aghamohammadi, V.; Bahnemiri, M.G.; Mohammadi, K. The effects of curcumin supplementation on inflammatory markers in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Nutr 2024, 64, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singgih Wahono, C.; Diah Setyorini, C.; Kalim, H.; Nurdiana, N.; Handono, K. Effect of Curcuma xanthorrhiza Supplementation on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients with Hypovitamin D Which Were Given Vitamin D(3) towards Disease Activity (SLEDAI), IL-6, and TGF-β1 Serum. Int J Rheumatol 2017, 2017, 7687053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasifard, M.; Khorramdelazad, H.; Rostamian, A.; Rezaian, M.; Askari, P.S.; Sharifi, G.T.K.; Parizi, M.K.; Sharifi, M.T.K.; Najafizadeh, S.R. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity and its associated complications: a randomized double-blind clinical trial study. Trials 2023, 24, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Gao, W.; Ma, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, X. Early-stage lupus nephritis treated with N-acetylcysteine: A report of two cases. Exp Ther Med 2015, 10, 689–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.W.; Hanczko, R.; Bonilla, E.; Caza, T.N.; Clair, B.; Bartos, A.; Miklossy, G.; Jimah, J.; Doherty, E.; Tily, H.; et al. N-acetylcysteine reduces disease activity by blocking mammalian target of rapamycin in T cells from systemic lupus erythematosus patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2012, 64, 2937–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perl, A.; Hanczko, R.; Lai, Z.W.; Oaks, Z.; Kelly, R.; Borsuk, R.; Asara, J.M.; Phillips, P.E. Comprehensive metabolome analyses reveal N-acetylcysteine-responsive accumulation of kynurenine in systemic lupus erythematosus: implications for activation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin. Metabolomics 2015, 11, 1157–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.J.; Francis, L.; Dawood, M.; Lai, Z.W.; Faraone, S.V.; Perl, A. Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder scores are elevated and respond to N-acetylcysteine treatment in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2013, 65, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comstock, G.W.; Burke, A.E.; Hoffman, S.C.; Helzlsouer, K.J.; Bendich, A.; Masi, A.T.; Norkus, E.P.; Malamet, R.L.; Gershwin, M.E. Serum concentrations of alpha tocopherol, beta carotene, and retinol preceding the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 1997, 56, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, S.C.; Kim, S.J.; Sung, M.K. Impaired antioxidant status and decreased dietary intake of antioxidants in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int 2002, 22, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeshima, E.; Liang, X.M.; Goda, M.; Otani, H.; Mune, M. The efficacy of vitamin E against oxidative damage and autoantibody production in systemic lupus erythematosus: a preliminary study. Clin Rheumatol 2007, 26, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, E.; Oaks, Z.; Perl, A. Increased mitochondrial electron transport chain activity at complex I is regulated by N-acetylcysteine in lymphocytes of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014, 21, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).