1. Introduction

Aerobic exercise enhances higher-order cognitive functions, such as attention and inhibitory control, by optimizing neurovascular units, primarily in the prefrontal cortex [

1]. The hyperbaric ygen (HBO) environment, which artificially modifies the available oxygen during exercise, increases the partial pressure of arterial blood oxygen and tissue oxygenation level, thereby influencing peripheral and cerebral circulation dynamics [

2]. However, few studies have simultaneously examined the combined effects of HBO and exercise, along with the intake of the n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), which possesses anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects, on the inhibition of human interference (Stroop task).

The authors recently observed that during exercise in an HBO environment, while the red blood cell count and hematocrit decreased, the hemoglobin concentration was maintained, leading to the proposition of a working hypothesis that reduced blood viscosity and stable oxygen-carrying capacity can coexist, implying enhanced microcirculatory efficiency [

3]. Furthermore, EPA supports neurovascular coupling reactivity by alleviating vascular inflammation and improving rheological properties [

4,

5]. Given these findings, HBO with exercise with EPA is expected to enhance the “functional reserve” of networks involved in conflict resolution and response selection, thereby boosting both the speed and accuracy of interference suppression. However, performance on the Stroop task is susceptible to the “speed-accuracy tradeoff,” and relying solely on reaction time or accuracy rates risks underestimating or overestimating the intervention effect [

6]. Therefore, throughput (number of correct responses per unit time), which integrates speed and accuracy, serves as a composite index. Furthermore, combining this with speed-based measures of interference suppression (I1/I2) allows for a more decomposed examination of where the effects manifest within the processing pipeline (perception, conflict resolution, and response selection) [

7,

8].

Furthermore, this study envisions future applications in space medicine. Astronauts perform tasks in spacesuits (typically 0.3 atm, 100% oxygen), effectively executing cognitive tasks in an environment equivalent to approximately 30% of terrestrial oxygen levels [

9]. This study provides foundational data to verify the effects of oxygen availability on cognitive function.

This study aimed to simultaneously examine aerobic exercise in an HBO environment and EPA intake within a randomized crossover framework in humans, clarifying their effects on speed-accuracy integrated performance (throughput) and speed-based interference (I1/I2). The primary hypothesis predicted that throughput would improve before and after the intervention (main due to the effect of time), independent of the environment, owing to contributions from exercise adaptation and task learning. Furthermore, an exploratory hypothesis posited that HBO enhancement of oxygen availability could yield additional gains (environmental main effect or environment × time interaction). Regarding interference measures, we aimed to verify a directional decrease (improvement) while anticipating small changes in short-term interventions.

The novelty of this study lies in its randomized crossover design that simultaneously addresses three factors: HBO, exercise, and EPA; analytical framework that centered on the speed-accuracy integration metric (throughput) as the primary outcome, with the speed-based interference suppression index (I1/I2) as a secondary measure; and linking of the obtained cognitive performance to the physiological working hypothesis of the blood and circulation system (simultaneous reduction of blood viscosity and maintenance of oxygen transport). This enables the bridging of exercise cognitive science with environmental physiology and nutritional sciences.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

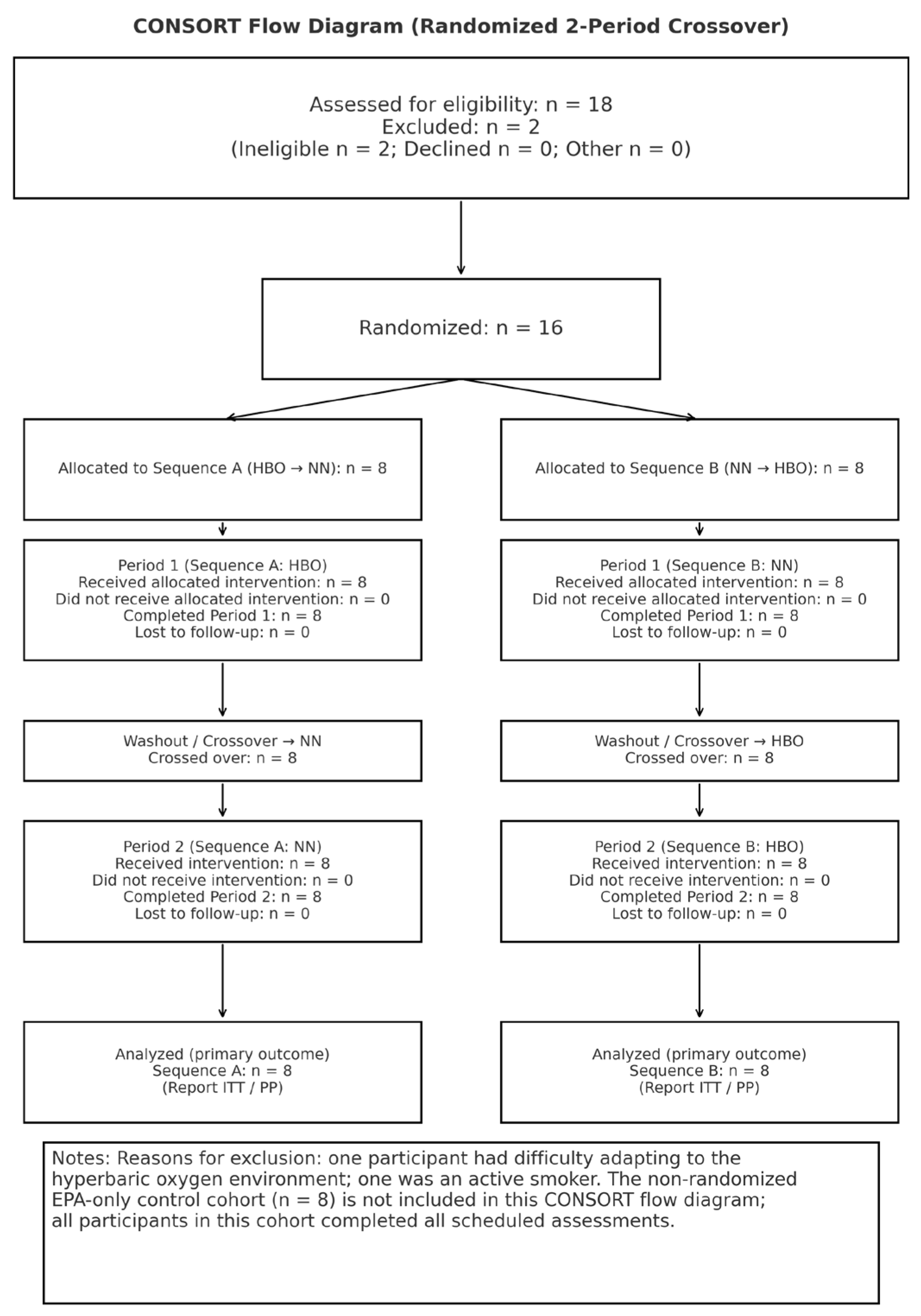

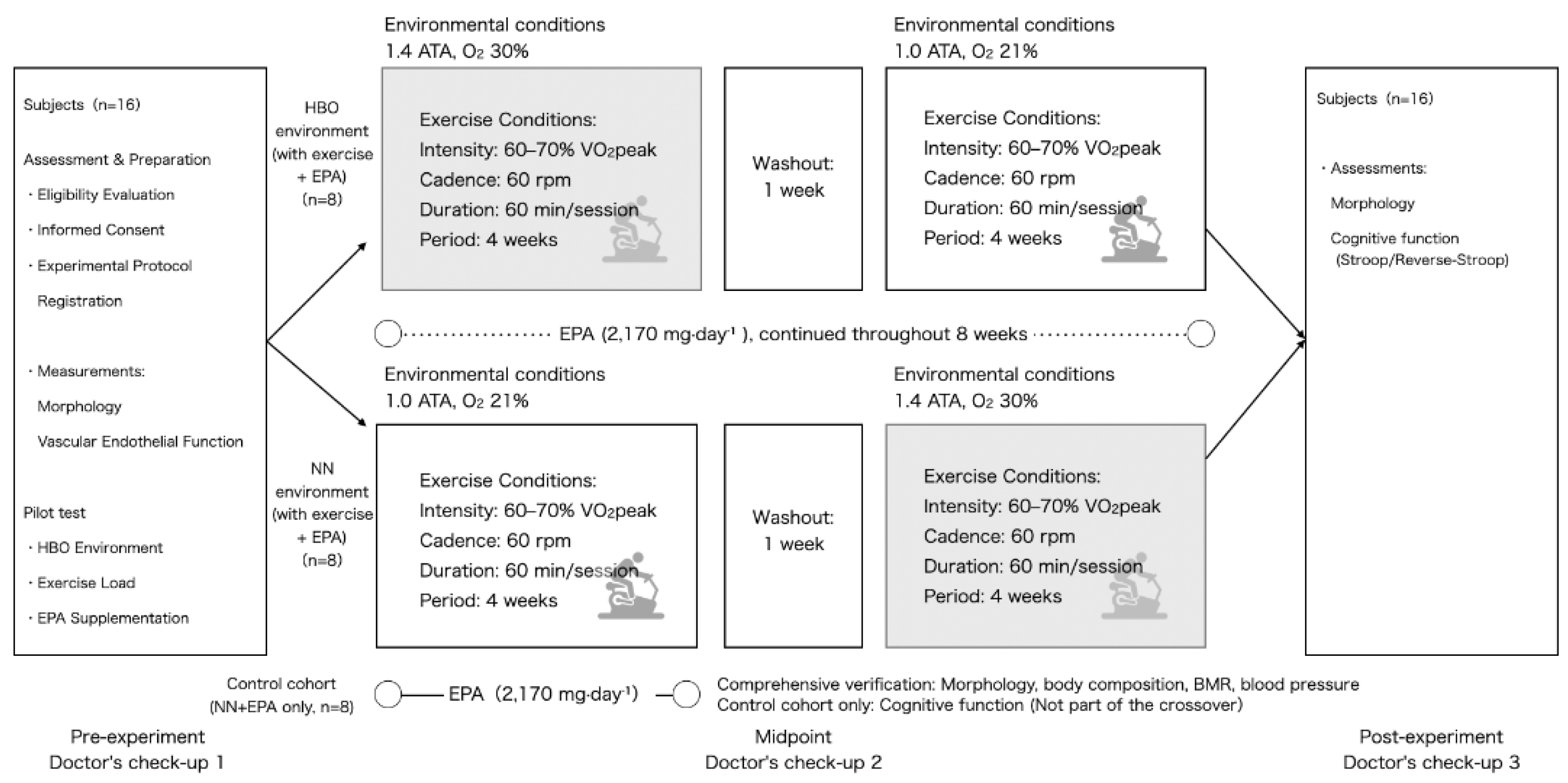

This was a randomized crossover trial (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) with a mixed design, combining a 2×2 within-subject crossover of HBO and normobaric normoxia (NN) with a parallel control group that received only EPA (no exercise). Participants were divided into three groups. Two groups performed supervised cycling training under either HBO or NN conditions while simultaneously taking EPA daily: the HBO+exercise+EPA and the NN+exercise+EPA. Subsequently, the crossover groups switched environments and repeated an identical protocol. The third group consumed only EPA without exercise and served as the EPA control group under the NN conditions. Each trial lasted for 4 weeks, with a 1-week washout period based on prior research on plasma EPA half-life [

10]. Health examinations and measurements were conducted before, during, and after the experiments. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The primary analysis focused on the crossover group (environment×time), whereas the EPA control group was included in the secondary analysis. This study was conducted as an experimental study on exercise and environmental physiology and not for medical purposes.

2.2. Participants

The participants for this study were recruited between April 25 and June 18, 2024. Twenty-four healthy adult males (mean ± standard deviation: age, 20.9 ± 1.4 years; height, 171.4 ± 5.6 cm; weight, 64.1 ± 11.6 kg; and body mass index (BMI), 21.8±3.6 kg/m²) were recruited openly and randomly assigned to the HBO + exercise + EPA, NN + exercise + EPA, or EPA control groups (n=8 per group). The inclusion criteria were as follows: no history of cardiovascular or metabolic disease, no history of smoking, ability to perform moderate-intensity exercise and take EPA-containing supplements during the study period, and ability to adapt to hyperbaric environments. The exclusion criteria were as follows: age < 20 years, excessive exercise habits, and requiring specific foods and/or supplements. Participants were instructed to avoid significant changes in their diet or lifestyle during the study period. The sample size estimation was assumed to be f=0.25, based on a 2-group × 2-time point parallel comparison. It should be noted that this was a conservative setting for the crossover design that included within-subject comparisons.

2.3. Experimental Environment

2.3.1. Environment

In the HBO environment, absolute pressure of 1.41±0.01 ATA, oxygen concentration of 29–31%, temperature of 21.7±0.7°C, and humidity of 73.5±4.6% were maintained. The NN environment maintained an absolute pressure of 1.00±0.01 ATA, an oxygen concentration of 20.9%, a temperature of 22.1±1.1°C, and a humidity of 70.5±6.5%. The HBO environment was constructed in an artificial environmental control chamber (Japan Pressure Bulk Industries Co., Ltd., Shizuoka, Japan) at a pressurization/depressurization rate of 0.07 ATA/min. A bicycle ergometer (STB-3400; Nihon Kohden Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was installed inside the chamber. The NN environment is established in a standard laboratory equipped with a similar facility. The hyperbaric chamber used complied with domestic operational safety standards (mild HBO Type II, ≤1.41 ATA) and was distinguished from medical treatment devices.

2.3.2. Eligibility Assessment, Pre-Experimental Measurements, and Medical Examination

Before enrolling for the experiment, the participants underwent a preliminary interview, supervised cycling training (peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak) measurement), and an assessment of their ability to adapt to the HBO environment. Medical examinations were performed by a physician. Baseline data, including anthropometric measurements and body composition, were collected at three time points: beginning, middle, and end of the experiment.

2.3.3. Anthropometric Measurements

Height was measured using a standard height gauge (A&D Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Weight and body composition parameters (fat-free mass [FFM], fat mass [FM], and fat mass percentage [% FM]) were assessed using a dedicated bioelectrical impedance analyzer (InBody 770; InBody Japan Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Based on these measurements, the BMI were calculated using the following formulas: BMI = weight (kg) / height² (m²). Systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure were measured using an automatic upper arm blood pressure monitor (HBP-1300; Omron Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) via an oscillometric method.

2.3.4. Exercise Load

The exercise intensity for the bicycle ergometer test was set at 60–70% of the VO2peak. The pedaling speed was 60 rpm, and each session lasted 60 min. The test was conducted twice a week for 4 weeks. Before the intervention, VO2peak was estimated using the breath-by-breath method with a respiratory metabolic monitoring system (AE-310S; Minato Medical Science Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Exercise in the HBO environment was performed for 60 min after reaching the predetermined absolute pressure. The time required for pressurization and decompression was approximately 20 min. Participants in the HBO group exercised in the HBO environment during the first phase and in the ambient-pressure environment during the second phase, while those in the ambient-pressure group exercised in the reverse order. The effects of the sequence and timing were examined using sensitivity analyses in the statistical analysis.

2.3.5. EPA Intake

During the study period, participants were instructed to take a high-concentration EPA supplement (Bizen Chemical Co., Ltd., Akaiwa, Japan) at 2,170 mg daily in capsule form. The EPA intake period overlapped with the exercise period in both environments. Intake was discontinued before study initiation and during the washout period. To ensure compliance and monitor gastrointestinal health, the participants were required to report their intake status, gastrointestinal symptoms, and stool characteristics online daily throughout the study period. The EPA dosage was food-grade and within the recommended range for dietary reference intake in Japan.

2.3.6. Cognitive Function Assessment: Throughput, T1–T4, and I1–I2

The New Stroop Test II (Toyophysical Co., Ltd., Fukuoka, Japan) was used to administer four tasks: T1 Reverse Stroop Control (semantic selection with no interference), T2 Reverse Stroop Interference (semantic selection with color ink interference), T3 Stroop Control (color name selection with no interference), and T4 Stroop Interference (color name selection with semantic interference). Each block was a 60-s self-paced response task with a randomized stimulus presentation and counterbalanced block order. Primary outcomes were throughput (correct responses per minute; correct·min⁻¹), integrating speed and accuracy; secondary outcomes included interference indices (I1/I2); and reference outcomes include accuracy (correct response rate). Throughput (T1-T4) was defined as processing efficiency = correct responses/60 s (unit: correct·min⁻¹). Interference indices were defined as I1 = (T3 − T4)/T3 and I2 = (T1 − T2)/T1. Accuracy was defined as a correct/incorrect response. Interpretation was based on both the p-value (Holm-corrected) and effect size [Hedges' gav·95% CI]. Positive values indicate improved throughput (increase), whereas decreases in I1/I2 indicate reduced interference. Each measurement was conducted in an NN environment immediately before and after the intervention.

2.3.7. Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver.27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The primary (throughput) and secondary outcomes (I1/I2) were analyzed using linear mixed models (LMM). Fixed effects included environment (HBO/NN), time (Post/Pre), and their interaction. Random effects included the participant ID intercept. The repeated-measures covariance structure was first-order autoregressive (AR(1)), and the estimation was based on the restricted maximum likelihood (REML). Fixed effect tests used Type-III Wald χ² (df=1), and estimates were reported as coefficient ± standard error (SE) and 95% confidence interval (CI). The effect size for within-group change was determined using Hedges’ gav (95% CI). The reference outcome (accuracy) was analyzed using generalized estimating equations (GEE; binomial logit, exchangeable, and robust SE). Effect measures are reported as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CI. Multiplicity was corrected using Holm’s method. The significance level was set at α=.05 (two-tailed), with a power of 0.80.

3. Results

3.1. Summary

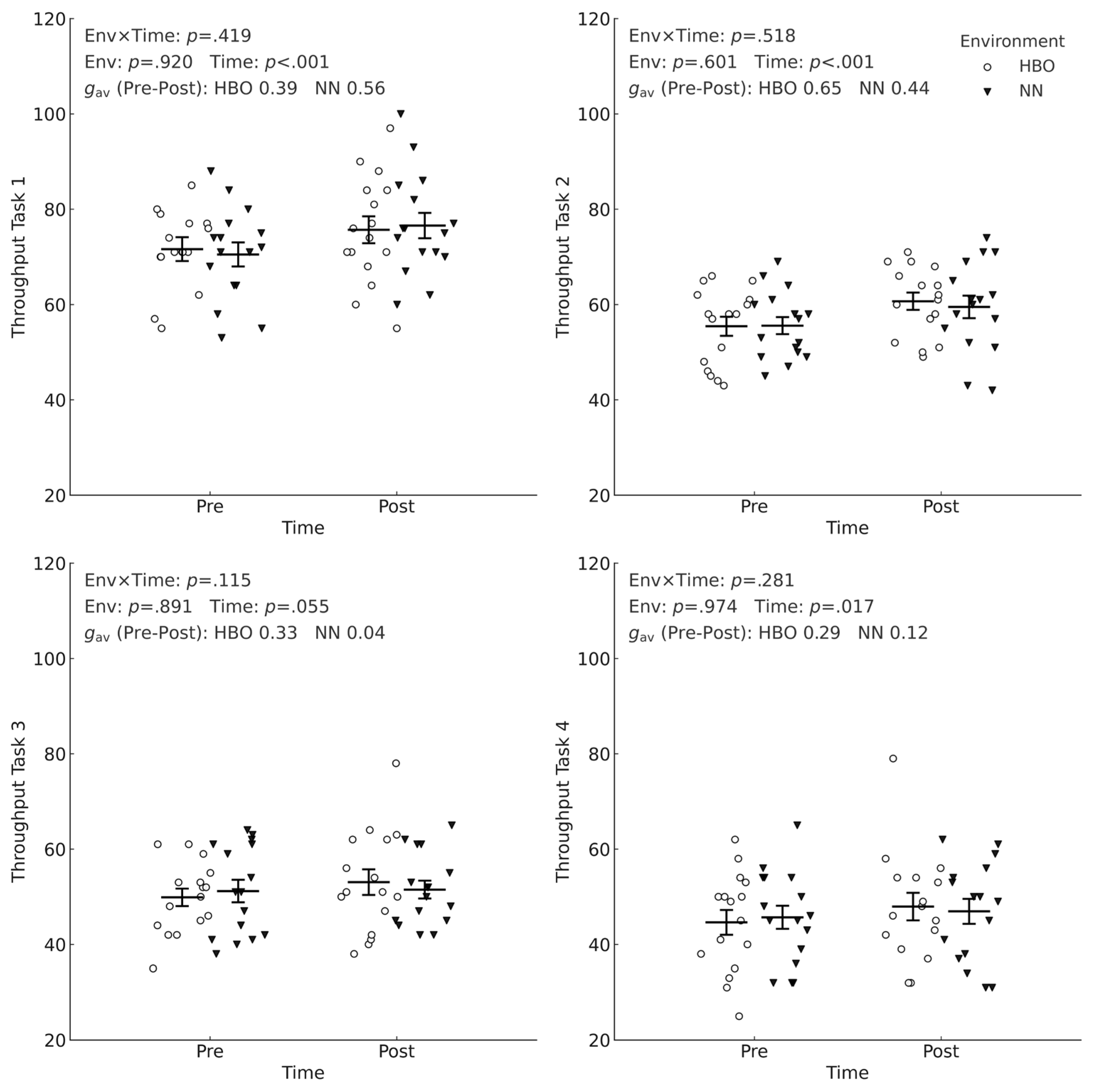

The environment × time interaction and the main effect of the environment were not significant. However, the main effect of time was significant at T1, T2 (

p<.001), T4 (

p=.017), and showed a trend at T3 (

p=.055) (

Figure 3).

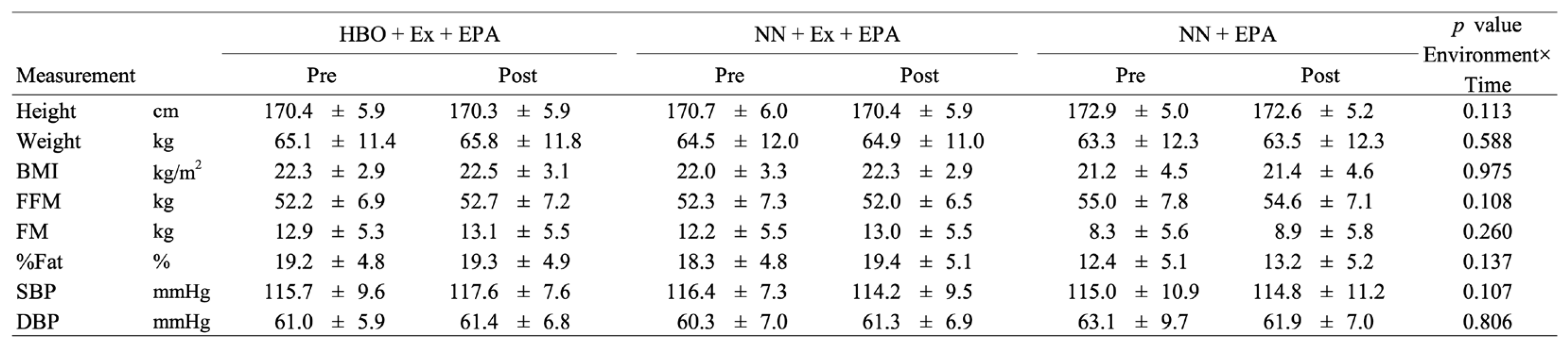

3.2. Physical Characteristics

The interaction effect of the environmental conditions and time was not significant for any of the following variables: height, weight, BMI, body composition parameters, or blood pressure. No significant changes in the physical characteristics were observed in the EPA control group (all p>.050).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics before and after the intervention in the HBO + exercise + EPA group, the NN + exercise + EPA group, and the NN + EPA group.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics before and after the intervention in the HBO + exercise + EPA group, the NN + exercise + EPA group, and the NN + EPA group.

3.3. Cognitive Processing Efficiency (Throughput)

Figure 3 shows the pre- and post-intervention throughputs of the HBO + exercise + EPA group and the NN + exercise + EPA group. No interactions were observed across any of the four tasks (T1:

p=.419, T2:

p=.518, T3:

p=.115, T4:

p=.281), and the main effect of the environment was also nonsignificant (T1,

p=.920, T2,

p=.601, T3,

p=.891, T4,

p=.974). In contrast, the main effect of time was significant at T1 and T2 (both

p<.001), significant at T4 (

p=.017), and showed a trend at T3 (

p=.055), indicating that the throughput improved after the intervention regardless of the environment. The magnitude of the pre- and post-intervention difference (Hedges'

gav) varied by task: T1-HBO, 0.39; NN, 0.56; T2-HBO, 0.65; NN, 0.44; T3-HBO, 0.33; NN, 0.04; T4-HBO, 0.29; and NN, 0.12.

Figure 3 shows individual data points and estimated marginal means ± SE, with units expressed as correct·min⁻¹.

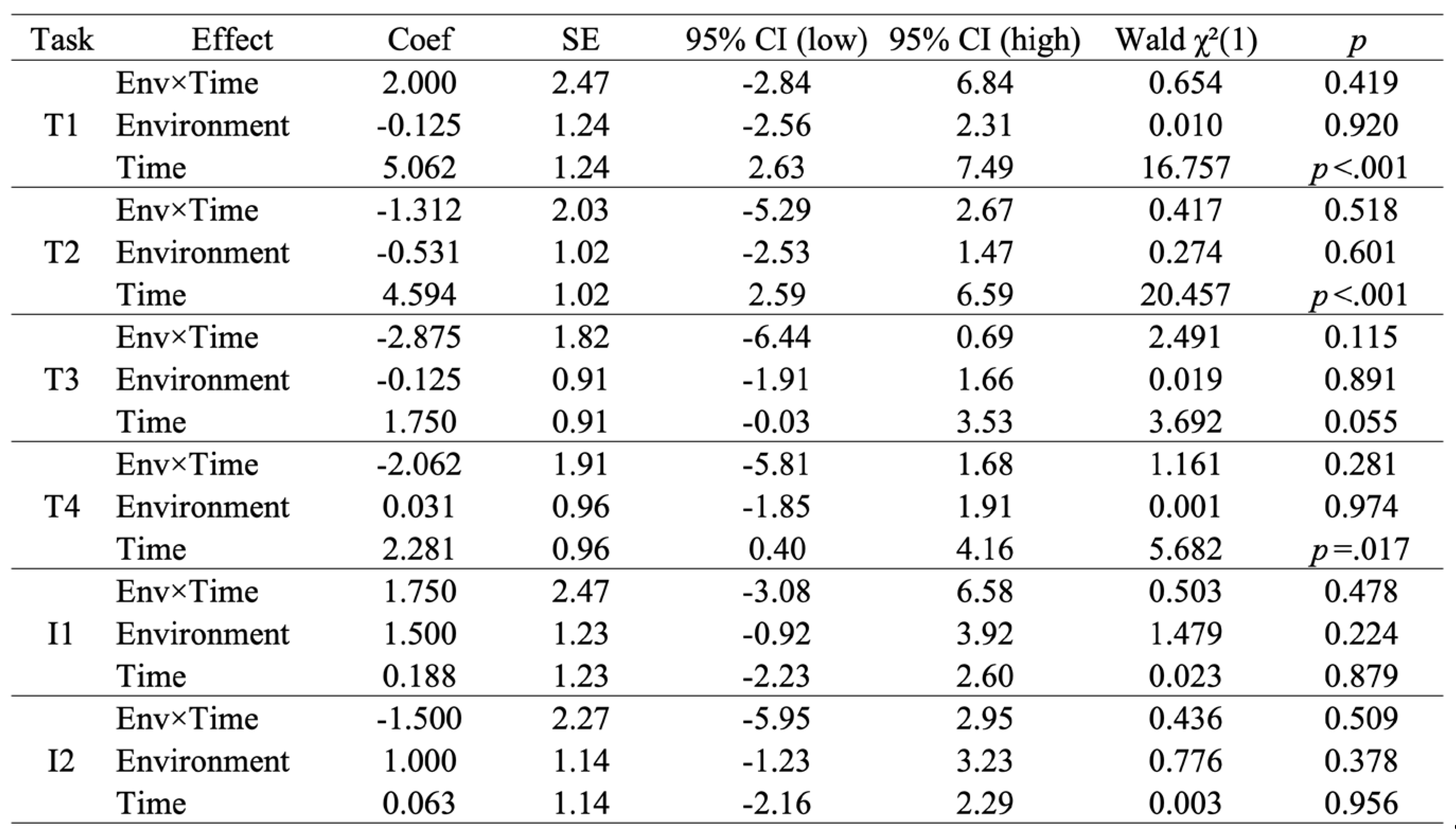

3.3.1. T1–T4 and I1–I2: LMM Test Table

In the LMM for T1–T4, no environment×time interaction was detected (T1: χ²=0.654, p=.419; T2: χ²=0.417, p=.518; T3: χ²=2.491, p=.115; T4: χ²=1.161, p=.281). No main effect of the environment was observed either (T1: χ²=0.010, p=.920; T2: χ²=0.274, p=.601; T3: χ²=0.019, p=.891; T4: χ²=0.001, p=.974). On the other hand, the main effect of Time was significant at T1 (coefficient=5.062, 95% CI [2.63–7.49], χ²=16.757, p<.001), T2 (coefficient=4.594, 95% CI [2.59–6.59], χ²=20.457, p<.001), and T4 (coefficient=2.281, 95% CI [0.40–4.16], χ²=5.682, p=.017), while T3 showed a trend (Coefficient=1.750, 95% CI [−0.03–3.53], χ²=3.692, p=.055).

Table 2.

The Type-III Wald χ² (df=1) test results for fixed effects in the LMM.

Table 2.

The Type-III Wald χ² (df=1) test results for fixed effects in the LMM.

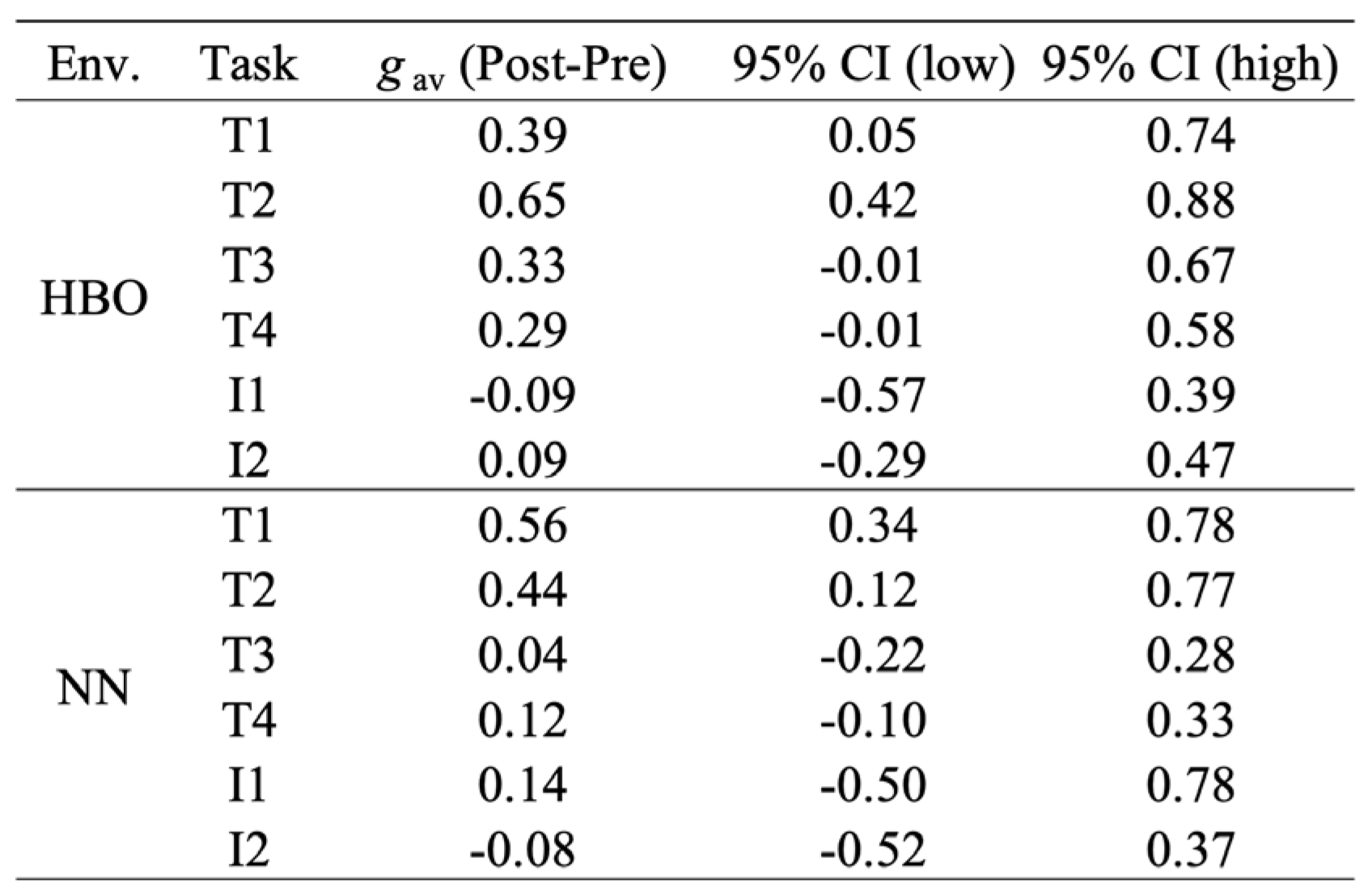

3.3.2. T1–T4 and I1–I2: Effect Sizes Within the Same Environment

For changes within each environment (gav), throughput had the largest effect at T2, with a clear improvement at T1, whereas T3 and T4 showed small and uncertain effects. For HBO: T1=0.39 (95% CI 0.05–0.74), T2=0.65 (0.42–0.88), T3=0.33 (−0.01–0.67), T4=0.29 (−0.01–0.58). For NN: T1=0.56 (0.34–0.78), T2=0.44 (0.12–0.77), T3=0.04 (−0.22–0.28), T4=0.12 (−0.10–0.33). Thus, T1–T2 showed a small to moderate improvement (particularly moderate too large for T2 in HBO and moderate for T1 in NN), while T3–T4 showed small effects, with 95% CIs frequently crossing zero.

The effect sizes of the interference indices (I1/I2) were both near zero with wide intervals, showing no substantial changes (HBO: I1 = −0.09 [−0.57–0.39], I2 = 0.09 [−0.29–0.47]; NN: I1=0.14 [−0.50–0.78], I2=−0.08 [−0.52–0.37]).

Table 3.

The effect sizes (Hedges’ gav) before and after exposure to the same environment.

Table 3.

The effect sizes (Hedges’ gav) before and after exposure to the same environment.

4. Discussion

This study used a randomized crossover design to examine the effects of supervised cycling training under HBO/NN environment with concurrent EPA supplementation on processing efficiency (throughput) and interference indices (I1/I2) in Stroop-type cognitive tasks. First, while throughput consistently improved mainly with time, the main effect of the environment and the environment × time interaction were not significant, and no short-term additive effect of EPA was observed. Furthermore, I1/I2 showed no significant changes, and the accuracy suggested a ceiling effect in one task (

Figure 3;

Table 2). Therefore, the observed enhancement in processing efficiency can be interpreted as primarily resulting from the progressive integration and optimization of speed and accuracy (semi-automation of response selection and efficient allocation of attentional resources) through regular aerobic exercise and task learning (repetition) [

11,

12,

13]. This supports the notion that exercise produces a generalizable facilitation across the processing pipeline and improves the efficiency of the entire Stroop task processing pipeline (perception, to conflict resolution, to response selection). Specifically, both behavioral measures (RT reduction and accuracy maintenance) and event-related potentials indicate that after aerobic exercise, resource allocation increases in the perception/stimulus evaluation stage (P2/P3), responsiveness to control demands in the conflict/inhibition stage (N2) improves, and consequently, response selection stabilizes and accelerates [

14,

15,

16].

However, these findings do not imply that HBO lacks efficacy. Possible reasons for failing to detect additional benefits of HBO include: participants being young healthy adults with high baseline abilities and limited room for improvement; HBO settings prioritizing mild HBO (≤1.41 ATA) and exercise intensity/frequency, along with EPA dosage/duration, potentially failing to reach physiological effect thresholds; the current task being relatively dominated by visual search and response selection, potentially making it difficult for the effects of oxygen availability differences to manifest [

17,

18,

19]. The primary implication of this study is that improvements in processing efficiency can be achieved through exercise training and task repetition, independent of the environment. It is reasonable to interpret that the additive effect of HBO/EPA was not absent but rather did not manifest under the dosage, duration, and task conditions used in this study. Furthermore, this trial has methodological significance in establishing and validating a protocol and measurement system (HBO settings, pressurization rate, exercise modality, and throughput as primary outcomes) that can be safely implemented in humans.

Furthermore, the lack of significant change in I1/I2 may be due to: task learning first boosting processing speed, potentially delaying its impact on interference suppression (conflict resolution); evaluation window issues (block length or measurement timing) making it difficult to detect subtle changes; or variance reduction in metric composition (ceiling/floor effects) [

20,

21,

22]. This interpretation is not a post hoc rationalization of non-significant results, but rather a positionable working hypothesis that can be pre-tested. Future work requires optimizing the interference intensity (incongruity ratio, stimulus probability, and conflict parameters) and task difficulty, along with refining the measurement design (block length and retest timing). In summary, the findings of this study can be coherently explained using a biphasic model. While motor adaptation (enhancement of efficiency in neurovascular units centered on the prefrontal cortex) and task learning (optimization of stimulus-response mapping) drive throughput increases, HBO/EPA likely has minimal effects or remains within the range of measurement sensitivity under the current conditions and participants. The proposed mechanisms include: enhanced responsiveness of cerebral blood flow and neurovascular coupling (NVC) [

11,

12,

13], stabilization of substrate supply during short-duration tasks via lactate signaling/mobilization of alternative fuels (medium-chain triglycerides; MCT system) [

23,

24,

25], and reduced reaction time variability associated with autonomic nervous system regulation (heart rate variability; HRV) [

26,

27,

28]. However, because this study did not simultaneously measure physiological indicators, these remain as the proposed mechanisms.

Future directions include: optimizing dose, duration, and frequency (HBO settings [partial pressure of oxygen, exposure time, and session frequency], exercise frequency, intensity, time, and type, EPA dose, and intervention duration); amplifying task difficulty and avoiding ceiling effects (manipulating mismatch ratio, stimulus presentation probability, and competition intensity); subdivision of assessment timing (separating acute responses, delayed effects, and longitudinal changes), direct verification of NVC-metabolic coupling through simultaneous measurement of physiological indicators like functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), electroencephalography (EEG), HRV, and expansion of study population (elderly, at-risk groups, and women). This should be systematically advanced [

1,

29,

30]. These approaches allowed for a rigorous examination of the boundary conditions for additive effects (which doses, durations, and loads elicit them) and the validity of the proposed mechanisms, thereby enhancing the external validity of the protocol established in this study.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Takehira Nakao: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Toru Hirata: Writing – review & editing. Takahiro Adachi: Methodology, Investigation, Resources. Jun Fukuda: Methodology, Investigation, Resources. Tadanori Fukada: Methodology, Investigation, Resources. Kaori Iino-Ohori: Writing – review & editing. Miki Igarashi: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization. Keisuke Yoshikawa: review & editing, Methodology, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Supervision. Kensuke Iwasa: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Atsushi Saito: Writing –review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Funding

This research was funded by MEXT KAKENHI (Grant Number 23K01975, 21K06807, 23K05122, 24K09866, and 25K18721).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyushu Sangyo University (protocol code 2023-0006 and 18 December 2023 of approval).” for studies involving humans, and registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network (ID: UMIN000057211).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.:

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ATA |

atmosphere absolute |

| BMI |

body mass index |

| DBP |

diastolic blood pressure |

| EPA |

eicosapentaenoic acid |

| FFM |

fat-free mass |

| FM |

fat mass |

| HBO |

hyperbaric oxygen |

| NN |

normobaric normoxia |

| O₂ |

oxygen |

| VO2peak |

peak oxygen uptake |

| %FM |

percent fat mass |

| I1 |

stroop interference 1 |

| I2 |

stroop interference 2 |

| SBP |

systolic blood pressure |

References

- Li, R.; Yang, D.; Fang, F.; Hong, K.S.; Reiss, A.L.; Zhang, Y. Concurrent fNIRS and EEG for Brain Function Investigation: A Systematic, Methodology-Focused Review. Sensors (Basel) 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulte, D.P.; Chiarelli, P.A.; Wise, R.G.; Jezzard, P. Cerebral perfusion response to hyperoxia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2007, 27, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, T.; Saito, A.; Adachi, T.; Fukuda, J.; Fukada, T.; Iino-Ohori, K.; Iwasa, K.; Igarashi, M.; Yoshikawa, K. Hemoglobin concentration maintained despite reduced erythrocyte count and hematocrit during exercise under hyperbaric oxygen conditions in healthy adult males: A randomized crossover trial. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, W.; Wei, W.; Li, X. Effect of fish oil supplementation on fasting vascular endothelial function in humans: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 2012, 7, e46028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodcock, B.E.; Smith, E.; Lambert, W.H.; Jones, W.M.; Galloway, J.H.; Greaves, M.; Preston, F.E. Beneficial effect of fish oil on blood viscosity in peripheral vascular disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984, 288, 592–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heitz, R.P. The speed-accuracy tradeoff: history, physiology, methodology, and behavior. Front Neurosci 2014, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liesefeld, H.R.; Janczyk, M. Combining speed and accuracy to control for speed-accuracy trade-offs(?). Behav Res Methods 2019, 51, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandierendonck, A. Further Tests of the Utility of Integrated Speed-Accuracy Measures in Task Switching. J Cogn 2018, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, O.H.a.M., Technical Bulletin OCHMO-TB-003. Ocular Health and Molecular Organization, 2023.

- Schmieta, H.M.; Greupner, T.; Schneider, I.; Wrobel, S.; Christa, V.; Kutzner, L.; Hahn, A.; Harris, W.S.; Schebb, N.H.; Schuchardt, J.P. Plasma levels of EPA and DHA after ingestion of a single dose of EPA and DHA ethyl esters. Lipids 2025, 60, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagni, V.; Drogos, L.L.; Tyndall, A.V.; Davenport, M.H.; Anderson, T.J.; Eskes, G.A.; Longman, R.S.; Hill, M.D.; Hogan, D.B.; Poulin, M.J. Aerobic exercise improves cognition and cerebrovascular regulation in older adults. Neurology 2020, 94, e2245–e2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivey, F.M.; Ryan, A.S.; Hafer-Macko, C.E.; Macko, R.F. Improved cerebral vasomotor reactivity after exercise training in hemiparetic stroke survivors. Stroke 2011, 42, 1994–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomoto, T.; Verma, A.; Kostroske, K.; Tarumi, T.; Patel, N.R.; Pasha, E.P.; Riley, J.; Tinajero, C.D.; Hynan, L.S.; Rodrigue, K.M.; et al. One-year aerobic exercise increases cerebral blood flow in cognitively normal older adults. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2023, 43, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, C.H.; Pontifex, M.B.; Raine, L.B.; Castelli, D.M.; Hall, E.E.; Kramer, A.F. The effect of acute treadmill walking on cognitive control and academic achievement in preadolescent children. Neuroscience 2009, 159, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Qin, C. Acute Moderate-Intensity Exercise Generally Enhances Attentional Resources Related to Perceptual Processing. Front Psychol 2019, 10, 2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davranche, K.; Audiffren, M.; Denjean, A. A distributional analysis of the effect of physical exercise on a choice reaction time task. J Sports Sci 2006, 24, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonehouse, W.; Conlon, C.A.; Podd, J.; Hill, S.R.; Minihane, A.M.; Haskell, C.; Kennedy, D. DHA supplementation improved both memory and reaction time in healthy young adults: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2013, 97, 1134–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, M.C.; Scholey, A.B.; Wesnes, K. Oxygen administration selectively enhances cognitive performance in healthy young adults: a placebo-controlled double-blind crossover study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998, 138, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholey, A.B.; Moss, M.C.; Neave, N.; Wesnes, K. Cognitive performance, hyperoxia, and heart rate following oxygen administration in healthy young adults. Physiol Behav 1999, 67, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najenson, J.; Zaks-Ohayon, R.; Tzelgov, J.; Fresco, N. Practice makes better? The influence of increased practice on task conflict in the Stroop task. Mem Cognit 2025, 53, 1696–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallaway, N.; Lucas, S.J.E.; Ring, C. Effects of Stroop task duration on subsequent cognitive and physical performance. Psychol Sport Exerc 2023, 68, 102459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedge, C.; Powell, G.; Sumner, P. The reliability paradox: Why robust cognitive tasks do not produce reliable individual differences. Behav Res Methods 2018, 50, 1166–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddock, R.J.; Casazza, G.A.; Buonocore, M.H.; Tanase, C. Vigorous exercise increases brain lactate and Glx (glutamate+glutamine): a dynamic 1H-MRS study. Neuroimage 2011, 57, 1324–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, T.; Tsukamoto, H.; Takenaka, S.; Olesen, N.D.; Petersen, L.G.; Sørensen, H.; Nielsen, H.B.; Secher, N.H.; Ogoh, S. Maintained exercise-enhanced brain executive function related to cerebral lactate metabolism in men. Faseb j 2018, 32, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takimoto, M.; Hamada, T. Acute exercise increases brain region-specific expression of MCT1, MCT2, MCT4, GLUT1, and COX IV proteins. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2014, 116, 1238–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, R.P.; Shapiro, P.A.; DeMeersman, R.E.; Bagiella, E.; Brondolo, E.N.; McKinley, P.S.; Slavov, I.; Fang, Y.; Myers, M.M. The effect of aerobic training and cardiac autonomic regulation in young adults. Am J Public Health 2009, 99, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggenberger, P.; Annaheim, S.; Kündig, K.A.; Rossi, R.M.; Münzer, T.; de Bruin, E.D. Heart Rate Variability Mainly Relates to Cognitive Executive Functions and Improves Through Exergame Training in Older Adults: A Secondary Analysis of a 6-Month Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Aging Neurosci 2020, 12, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.P.; Thayer, J.F.; Koenig, J. Resting cardiac vagal tone predicts intraindividual reaction time variability during an attention task in a sample of young and healthy adults. Psychophysiology 2016, 53, 1843–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothermund, K.; Gollnick, N.; Giesen, C.G. Accounting for Proportion Congruency Effects in the Stroop Task in a Confounded Setup: Retrieval of Stimulus-Response Episodes Explains it All. J Cogn 2022, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Jia, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Effects of exercise interventions on cognitive functions in healthy populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2023, 92, 102116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).