1. Introduction

Elementary DNA lesions produced in ionizing radiation (IR) exposures include single strand breaks (SSB), double strand breaks (DSB) and base-damages (BD). In addition, IR produces a plethora of clustered DNA lesions defined as two or more elemental lesions that are formed within one or two helical turns of DNA (~10 base-pairs (bp)) by a single radiation track, and complex clusters consisting of 3 or more elemental lesions [1,2,3]. IR is an efficient inducer of both DSB and non-DSB damage clusters, including complex DSB with BD or SSB adjacent to DSB. Experiments have shown that clustered non-DSBs occur with higher frequency than DSBs [4,5,6,7,8,9], however the extent to this difference is uncertain as discussed below. For low dose exposures (<0.2 Gy) cells will receive few or no prompt DSB, and it is suggested that non-DSB clustered damage plays a large role in slow DNA repair, delayed DSB formation and mutation [10,11,12,13,14,15]. These observations point to the importance of understanding non-DSB clustered damage for occupational exposures on Earth and in space and normal tissue effects in radiation cancer treatment.

Experimental methods to detect non-DSB structures have used enzymatic probes, such as endonuclease III (Nth) to detect oxidized pyrimidines, formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase (Fpg) to detect oxidized purines, and Nfo protein (endonuclease IV) to detect abasic sites [4,5,6,7,8]. In this method DNA is treated with an endonuclease that induces single strand cleavage at an oxidative or abasic site. Similar methods were recently combined with atomic force microscopy to provide additional observations of the multiplicities of non-DSB clustered damage [9]. However, such experiments only detect bi-stranded lesions leaving a gap in confirming the frequency of tandem clusters consisting of 2 or more elementary lesions.

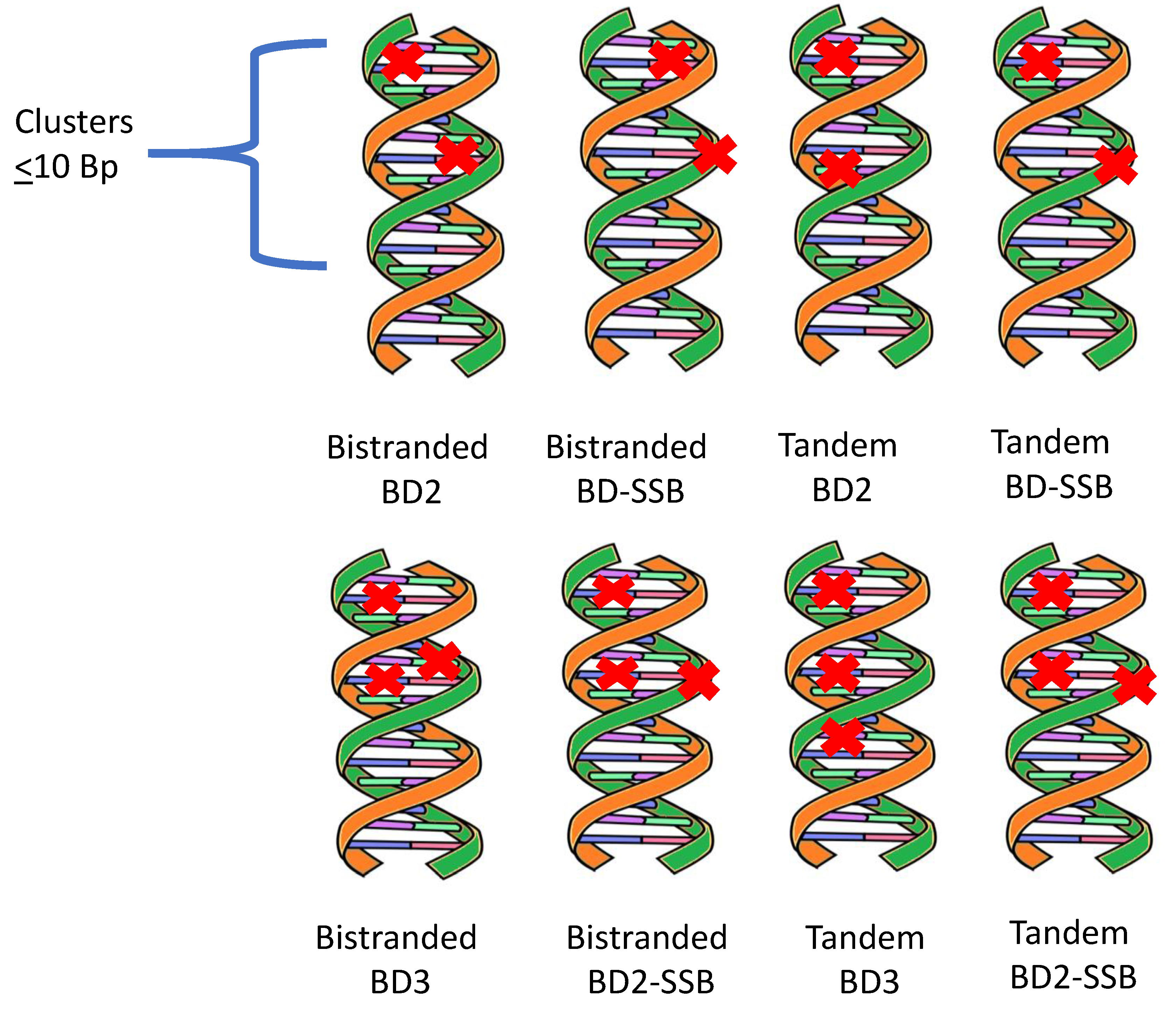

Figure 1 illustrates possible bistranded or tandem non-DSB clusters that are induced by radiation tracks. It is suggested that tandem and bi-stranded non-DSB clusters will occur with similar frequency [5], however theoretical descriptions in this area are needed. In addition to lack of data on tandem non-DSB clustered damages, Gulston et al. [6] note that not all base damages are detected by enzymatic probes used in the experiments noted, which could increase the frequency of non-DSB damage clusters beyond the contributions of tandem clusters.

Complex DSBs defined as a DSB with additional SSB or BD occurring within 10 bp has been a focus of many modeling studies [16,17,18,19,20,21,22], however computational models have provided sparse predictions on the yields of clustered non-DSB, which is the main focus of the present report. In this paper I develop a multinomial probability model that predicts the spectrum of DNA damage types, including yields of simple and complex DNA breaks and clustered non-DSBs that can be applied to various types of radiation modalities. The model uses the spectrum of energy imparted in a nanoscale volume containing DNA, which is folded with the probability of producing specific types of simple or clustered types of DNA damage to predict over 30 lesion types. Charlton et al. [16] found a 54 bp segment was sufficient to describe DNA damage clusters for electrons and high LET protons and alpha particles. However, to describe high LET radiation, including heavy ion damage, I use a larger DNA segment. For comparisons to experiment, I apply the frequency distribution of energy imparted for a 5x5 nm cylindrical volume containing ~73 bp. The model is based on probabilities for SSB, DSB, BD, and radical formation as a function of energy imparted and their combinations using multinomial probabilities and extends a recent work by the author [23] that focused on DSB predictions, while lacking descriptions of the spatial location of BD within a 73 bp segment.

2. Model Development

The present approach to predict the frequencies of various DNA lesion types combines models of the frequency spectra of energy imparted with probabilities to form specific lesion types, which are functions of energy imparted. The yield of a specific damage type

, j, per Gy is evaluated as [16,23]:

where

c is conversion constant for evaluating yields as per Gy per bp (or similarly for per Gy per Dalton or per Gy per cell), and

dF/dε is the differential distribution of energy imparted, ε per Gy. The function

is the probability of producing a specific damage type,

j for energy imparted, ε, as described below.

For ions it is useful to describe damage frequencies expressed as an action cross section in units of number of damages per Gbp per particle (i.e., unit fluence) given by,

where

dF/dε is normalized to unity,

nBP=73, and

is the frequency mean specific energy. The main problem is then to develop a model for the probability functions,

, which is described next.

Multinomial Probability Formalism

Four types of events resulting from energy imparted to the volume containing DNA are considered in the model: A) direct ionization of sugar-phosphate moieties with probability PA leading to a SSB, B) direct damage to DNA bases with probability PB, C) ionization of water leading to OH- radicals with probability, PC, and D) energy imparted to histone proteins and other co-located molecules in the volume not leading to SSB or BD, PD. Evaluating the distributions in lesion numbers related to the A, B, C, and D probabilities, which are dependent on values of energy imparted, to high-order combined with a model for their relative location, allows for predictions of clustered damages of increasing complexity.

Computational models can assume an absolute threshold energy for an event to occur or a response function that describes the efficiency for producing an event above the threshold [20,23]. Here I will use a simple energy imparted threshold with a value estimated near an absolute threshold. In previous work, I assumed the energy threshold for each event was identical to simplify the formalism. However, because the energy threshold for radical formation in must lower (~5 eV) compared to the other events, the present work modifies the approach. The induction of base damages is dominated by indirect effects; however, the model assumes that energy imparted above a threshold energy is also causative of base damage lesions in direct damage.

Monte-Carlo based simulation models most often use 17.5 eV as a threshold for SSBs [16,17,18,19,20,21] based on fitting experimental data for SSB and DSB yields. Threshold energies for BD ionization are similar [24]. In the model the energy thresholds for ionization corresponding to

A,

B and

D events,

εTH1, are taken as identical using the estimate of 17.5 eV with the probabilities for damage estimated simply by the fraction of the volume taken up by each component as described below. In the multinomial form the A, B, and D probabilities are constrained to unit normalization,

PA+PB+PD=1, while the C probability is constrained by in a binomial function described next. The threshold energy for radical formation (

C probability),

εTH2, is lower compared DNA components. The corresponding probability is assumed to follow a binomial distribution with the total number of events

JTC(ε) determined by multiples of a threshold energy,

In this approach as the energy imparted, ε, increases the number of possible events increases, however the imparted energy available for

A,

B, and

D damages is reduced by the energy imparted leading OH- radicals formed and vice-versa.

The overall probability distribution for various combinations of

A,

B,

C, and

D events is thus the folding of the binomial distribution for radical formation with the multinomial distribution for

A,

B, and

D events,

The probabilities for number of OH- radicals, SSBs and BDs are enumerated and marginal distributions formed to evaluate various types and combinations of DNA damage lesions. Note the definitions PA=pA nSSB and PB=pB nBD, which are used in the following developments.

Specification of Clustered Lesion Types

As the energy imparted increases complex clustered damages occur, including multiple SSB, DSB, and BD within Nclus bp (e.g., 10 bp). Multiple simple types of SSB, DSB or BD that are isolated from other lesions with a >Nclus bp criteria are considered with some number of these possible as function of energy imparted. Partial-probabilities, which are to be folded with the multinomial coefficients, for elementary populations of SSB, BD, and DSB are denoted as nI(#DSB,#SSB,#BD) and nC(#DSB,#SSB,#BD) for a number of isolated or clustered lesions, respectively. The index in parenthesis indicates the number of such lesions that are >Nclus bp for an isolated lesion or <Nclus for a clustered lesion. The definition of a simple DSB is written as a cluster, nC(1,0,0). The cluster definitions are modified when clusters of two or three BD or BD with SSB on opposite or tandem strands occur with no DSB. These possibilities are denoted as nCO(0,#BD,#SSB) and nCT(0,#BD,#SSB), respectively. For four or more BD or BD with SSB, the probability of a bistranded (opposite) type cluster is found to be much larger than tandem cluster and these types are therefore grouped into a single population.

Two additional probabilities are needed to evaluate SSB, DSB, and BD and their combination probabilities. The first is to account for the spatial location of multiple SSB or BD in accordance of the two or more lesions within

Nclus bp criteria for a complex lesion. I assume this possibility is equally probable on either DNA strand with mathematical operators that adds SSB or BD on opposite or identical strands denoted as,

and

with their magnitude constrained by,

It follows that is the mathematical operator for the introduction of an additional SSB or BD that is farther than Nclus bp apart from a previous one. The possibility that the q0 and q1 values are distinct for SSBs and BD is not considered in the present work, however could be easily adapted in the formalism. The values of q0 and q1 are dependent on the number of SSB or BD induced because as the number increases they are more likely to fall within a Nclus bp. A model for their values is described below.

Additional probabilities are needed to estimate if an SSB or a BD is formed by radical attack, with probabilities denoted as r1 and r2, respectively. Scholes et al. [25] made an estimate of interactions by OH- radicals of 80% with bases and 20% with sugar-phosphate moieties. This estimate is combined with the 65% probability of conversion to SSB in used in Monte-Carlo DNA damage simulation codes [17,18,19,20] based on fitting experimental data, which leads to an overall 13% probability for an SSB from OH- radical damage. The same criterium is used here to estimate a probability for BD formation by radical attack, which is 0.8x65%=52% This leads to the parameter estimate of r1~0.13 for conversion to SSB and r2~0.52 for conversion to BD, while r3=1-r1-r2 represents the probability that no SSB or BD is formed by an OH- radical.

Strand-Break Clustering Operator

To evaluate terms with multiplicative probabilities such as

PAPA, I treat the probabilities using a mathematical operator, e.g.

with a numerical value, denoted by lower-case,

p, which is set by a multinomial coefficient. The operator combines multiple damages in the volume considering the

<Nclus bp criteria to determine which type of damage occurs. The operator that describes the lesion location and their possible complexity as SSB’s are added into a volume representing a small DNA segment is defined,

where the operand appears in square brackets. In addition, to simplify notation the magnitude of product terms to order

JA is written,

. In the following, the

pj constant factors are not shown to simplify the notation, while their values for various permutations using multinomial coefficients of Eq. (6) or binomial coefficient for

C–events are easily identified.

The 2

nd-order term

PAPA is found to contain 3 branching probabilities that are weighted with the identical multinomial probabilities defined in Eq. (6),

The 3

rd-order term leads to 5 branches,

Equation (9) predicts that bistranded and tandem clustered lesions consisting of a DSB and 2 SSBs, respectively occur with equal probability. Equation (10) predicts that the probability of a complex DSB comprised of 3 SSBs exceeds that of a complex SSB cluster with 3 tandem SSB’s, probability by 3-fold in their first occurrence at the 3rd order. However as shown below indirect effects will modify this prediction.

In considering the 4

th and higher order terms in order to simplify notation the various probability branches are written using addition signs, however each term in the following represents a distinct possibility. The 4

th order term in the

A-probability is found as,

with

The A44 term of equation (11) predicts a 7:1 ratio for bistranded to tandem lesions made-up of 4 SSBs from direct effects.

Base Damage Clustering Operator

For modeling base damage, I do not make a distinction between abasic sites and oxidative sites, and only the total amount of base damage is estimated. The base damage clustering operator follows a similar mathematical form as the

A-operator with,

defined,

The 2

nd-order term

PBPB is found to contain 3 branching probabilities that are weighted with the identical multinomial probabilities defined in Eq. (6),

The 3

rd-order term leads to the following 5 branches,

The 4

th order term in the

B-probability is found as,

Similar to the prediction for clustered lesions with multiple SSBs, the model predicts ratios of bistranded to tandem lesions of 1:1, 3:1, and 7:1 for clusters of 2, 3 or 4 BD, respectively when formed from direct effects.

Mixtures of A and B Probabilities

Terms with mixtures of

A and

B probabilities to the 2

nd and 3

rd orders are found as,

Mixtures of

A and

B terms at the 4

th-order are listed in

Appendix A and an approximation for 5

th and higher-order terms described below.

Indirect Damage Clustering Operator

The clustering operator in formation of SSB and BD by radical attack is defined,

At first order the r3 probability does not produce any effect, and in general, the r3 component of the C1 operator on any operand, [O] is simply r3O for 2nd and higher-order terms.

At 2

nd order,

C2 is found in terms of

A and

B probabilities as,

The last branch involving

C1 is applied with the binomial coefficient for the

C2 probability. The 3

rd order

C-term is found as,

The mixture of

A, B and

C terms at 3

rd order is found as:

In

Appendix A the other 2

nd, 3

rd and 4

th order terms involving mixtures are listed.

The

and

operators acting on products of

A-terms and

B-terms of arbitrary order are found to be reduced to

A and

B probability terms with the following expressions,

5th and Higher-Order Terms

The 5th and higher-order terms, including mixture terms, will have many components. In formulating mixtures of heterogeneous terms, the order of the probabilities is invariant. At all orders the D probabilities appear as simple products with A, B, C or combinations of A, B, and C of various orders. It is also noted that the frequency distribution of energy imparted is decreasing rapidly, especially for low LET radiation, in the region where 5th and higher order A and B terms contribute (ε>100 eV).

Two approximations are used to evaluate 5

th and higher-order terms. The first approximation applies for considering the indirect effect probabilities. Here because

for

p>2, an accurate approximation for higher-order terms is,

The second approximation is based on noting that at high order 2

q1>

q0 and

q0 approaches zero at very high order. This observation leads to an approximation method to evaluate 5

th and higher order terms. First, I note that terms to order

JA,

JB, or

JAxJB, etc. must follow an inherent binomial probability rule for the factor

. Therefore, the expansion in terms of increasing powers of

q0(2q1) should be the basis for evaluating higher terms. This expansion is described using binomial coefficients:

The form of the binomial expansion is apparent for the 2

nd and 3

rd order described above and 4

th order terms described in

Appendix A. The 5

th and higher-order terms are dominated by clusters of increasing complexity, and limit to highly complex clustered damage for

J>>1. It follows that for

JA>4 (similarly for

B or product terms) an accurate approximation is to evaluate contributions up to

q13 and tally

q14 and higher-power terms in the binomial expansion into a super-cluster (

nSC) category made-up of 5 or more elementary lesions, with strength determined by the binomial expansion coefficients of Eq. (26). Therefore, for

JA>>1 the summation of the series limits to an effective super-cluster population while maintaining exact terms up to

q13 in an expansion. Defining

JM=JA-1, the approximation for higher order terms (

JA>4) is,

where

nSC1 is made-up of DSBs and SSBs, and

nE1,

nE2, and

nE3 are populations of similar

q1-rank described above, however modified by additional products of isolated SSB lesions, and the coefficient,

LJA is,

This approach is also used for JB >4 terms with nSC2 made-up lesions containing 4 or more base damages and absent of SSB or DSB.

In a similar manner for product terms when

JA+JB>4, I define

JN=

JA+JB-1 and introduce the approximation,

with a third-category of super-clusters defined by,

For mixtures of A, B, and C probabilities at 5th or higher-order I use the reduction formula for C-probabilities described above.

Estimating q0 and q1 Probabilities

In nanoscale volumes single electron or ion tracks and local secondary electrons produced through ionization are causative of DNA lesions. Secondary electron kinetic energies are typically <100 eV for primary electrons of a few keV and increase slowly with primary energy. For secondary electrons of kinetic energy~100 eV, mean-free paths (MPF) are ~1.5 nm [26], with MFP increasing with electron energy reaching values >10 nm for high energy electrons. In a previous work [23] the q0 parameter as a function of number of lesions was estimated by randomly placing 2 or more lesions amongst the 73 bp in the volume. This approach led to higher numbers of DSB complex clusters relative to predictions of Monte-Carlo simulation models [17,18,19] and is modified here. In future work Monte-Carlo track simulations with realistic DNA representations will be used to estimate the q0 and q1 probabilities. Here to estimate possible clustering related to the q-probabilities, I considered binomial and Poisson distribution models. The binomial distribution describes the probability that a 2nd elementary lesion is more than 10 bp apart from a another one. A binomial distribution model with q0~ 0.92 is found to provide similar results for DSB clusters as Monte-Carlo predictions for electrons [17,18,19]. A Poisson distribution model for the cluster size formed within 10 bp when 2 or more elementary lesions occur can also be considered with the mean of the Poisson distribution assumed as the ratio of the maximum dimension of the cluster region to the MFP of secondaries produced or primary electrons, however the Poisson model would require a modified version of the multinomial probabilities described above and will be reported elsewhere. For a 73 bp segment there is some possibility of 2 or more clusters that are separated by >10 bp, however this is not considered in the present paper and will be evaluated in the future. Experimentally more than one clustered damage located close to each other is not likely detected [5,6].

3. Results

Parameter values were largely the same as in a previous publication [23]. To estimate the pj probabilities the molecular weight of each component is considered. The average molecular weight of each of the 8 histone proteins is 14 kDa, and of DNA 0.65 kDa per bp. The number of water molecules varies under specific conditions with estimates of ~3000 per nucleosome [27]. Bases on these estimates, calculations were made with values of pA=0.3, pB=0.3, and pD=0.4 representing estimates of the fraction of energy imparted within a 5x5 nm target volume by each component. For radicals formed from water molecules described by a binomial distribution, I use pA=0.333, with results changing modestly for values from 0.25 to 0.4.

Calculations were performed for 100 keV electrons, which are often used as a representation of ortho-voltage X-rays (100 to 500 kVp) because of the weak dependence of electron energy imparted spectra above ~20 keV. Calculations were also performed for protons,

4He and

12C for 30 kinetic energy values from 0.1 MeV/u to 10,000 MeV/u, and for

56Fe ions at 20 energies between 50 and 10,000 MeV/u. Frequency distributions for electrons [28,29] and ions [30] in 5x5 nm cylinders are evaluated as described in previous publications [23,30]

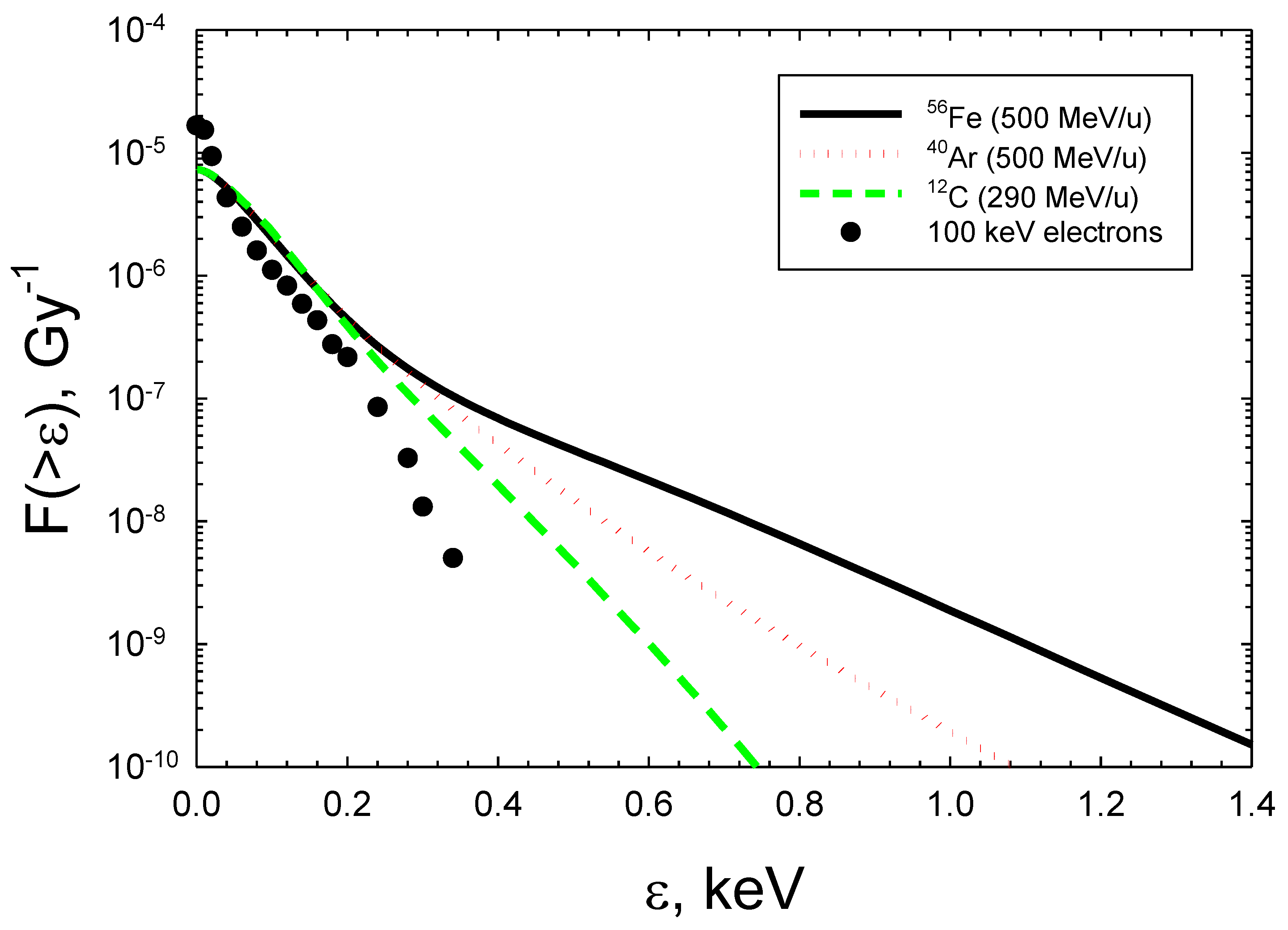

. Figure 2 shows frequency distributions per Gy for 100 keV electrons from Monte-Carlo track structure simulations with the MOCA8B computer code [28,29], and results from an analytical model for heavy ions [30]. The analytical model considers a core term where the ion passes through a target, and a penumbra term from δ-ray electrons when the ion passes outside the target [30]. For the penumbra contribution Monte-Carlo results for electrons [28,29] are folded with estimates of the electron spectra produced by ions [30,31] as a function of radial distance from the ion to the target center. The spectra in

Figure 2 predict that the frequency of energy imparted below ~200 eV to the target volume are very similar for most radiation modalities, while much larger energy imparted (>200 eV) values occur for heavy ions or other high LET radiation.

In the model over 30 damage types including over 20 clustered damage types are predicted.

Table 1 shows results for several types of clustered non-DSB and DSB lesions for 100 keV electrons,

4He (1 MeV/u with LET= 104 keV/μm)),

12C (290 MeV/u, LET=13 keV/μm) and

56Fe (1000 MeV/u, LET=148 keV/μm). In the comparisons the total tandem or bistranded lesions include 2, 3, or more base-damages or BD with SSBs, while tandem SSB’s are shown separately as SSB2 (

nC(0,2,0)) for 2 tandem SSB and SSB>2 (

nC(0,>2,0)) for 3 or more tandem SSB. If 4 or more BD occur they are grouped into the bistranded category based on the mathematical analysis in Eq. (15), which shows the bistranded type greatly exceed tandem for >4 BD in a cluster. The total non-DSB entries are for all types of non-DSB clusters including tandem SSBs. The

4He ions with low energy and high LET are predicted to have lower non-DSB cluster yields compared to electrons, which is due to its narrow highly ionizing radiation track. In contrast the relativistic

12C and

56Fe ions with track structures dominated by a penumbra of δ-ray electrons are predicted to have modestly lower yields of non-DSB clustered damages compared 100 keV electrons.

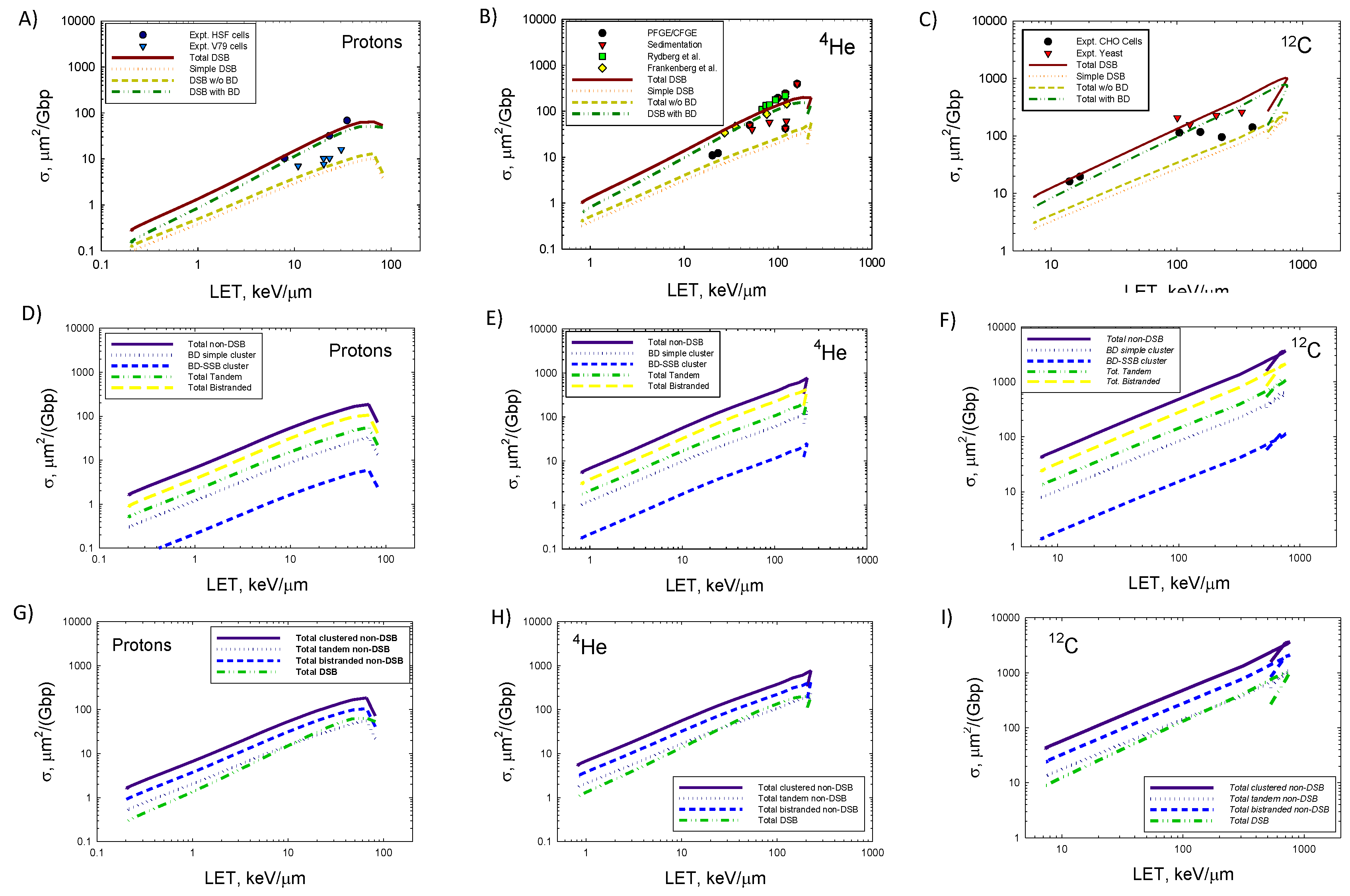

In

Figure 3 we show actions cross sections for protons,

4He, and

12C ions versus LET for non-DSB and DSB clustered damage. Panels A, B, and C are for protons,

4He, and

12C ions, respectively for simple and complex DSB versus experimental data [32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. DSBs with BD greatly exceed DSBs without BD, which was predicted by Monte-Carlo track structure models [17,18,19]. Agreement of the model to the measurements is satisfactory, especially when the variation in data reported for different cell types and methods such as pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) or sedimentation are considered [32,33,34,35,36,37]. In past studies there are reported differences in yields between human and rodent fibroblasts or yeast with results for human fibroblast cells tending to be larger than V79 Chinese hamster cells [5]. Such differences are not considered in the present model, however because of the rapid computation times of the present approach fitting of the model parameters to different experimental conditions could be considered. At the highest LET values of ions experimental methods are expected to under-estimate DSB counts because more than one DSB in an extended region of DNA (<10 kbp) may be identified as a single DSB.

Panels D, E and F of

Figure 3 show the LET dependence of several types of clustered non-DSB, and Panels G, H, and I show comparisons of several non-DSB categories to total DSB action cross sections. In

Figure 3 the slope of the curves with LET is similar for each clustered damage type with some distinction for DSB at the highest LET values corresponding to low energy ions (<5 MeV/u). These results are consistent with previous observations of frequency distributions that reveal that large differences between high and low LET radiation occur at values of energy imparted, ε>200 eV for small volumes [1], however frequencies are similar at lower values. The production of clustered lesions made-up of 2 or 3 elementary lesions will already occur for energy imparted, ε<100 eV. Thus, larger differences for high LET radiation compared to low LET radiation will occur for more complex lesions made-up of 4 or more elementary lesions and will be considered in a future report. The action cross sections increase in an approximately linear dependence on a log-log graph with slopes that change slowly with increasing ion charge number. The slopes are modestly less steep for

12C compared to protons or

4He.

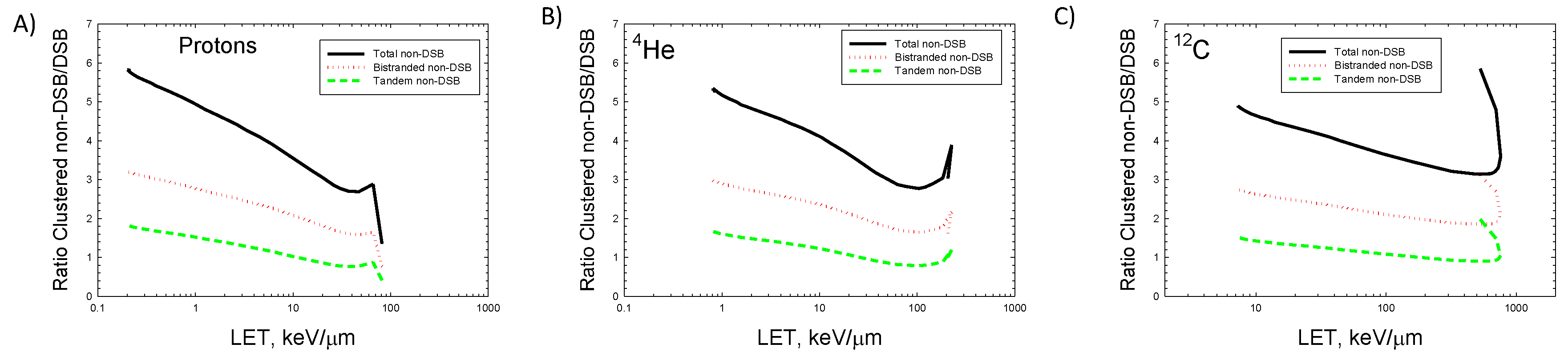

In

Figure 4 the ratio of tandem, bistranded, and total non-DSB clusters to the total number of DSB are shown. Predictions of the model show ratios of 4-to-6 for exposures to for e.g., normal tissue by so-called plateau ions in protons,

12C or other heavy ions in cancer therapy or space radiation exposures that are dominated by relativistic ions. For

4He and

12C a rapid increase occurs in the ratios at the highest LET values is predicted which corresponds to values beyond the Bragg peak for these ions. The effects of energy straggling on calculations were not considered and would be needed to make comparisons to experiments at low energy such as the near the Bragg peak. Radical recombination may reduce indirect effects in the core region of high charge number ions such as

56Fe especially at all energies, and at low energy (<5 MeV/u) (high LET) for p,

4He, and

12C ions [41,42]. This effect has not been considered in the model, however because the model predicts the number of radicals produced and includes a coarse description of their location an empirical approach to account for recombination impacts on indirect damage could be considered in future work.

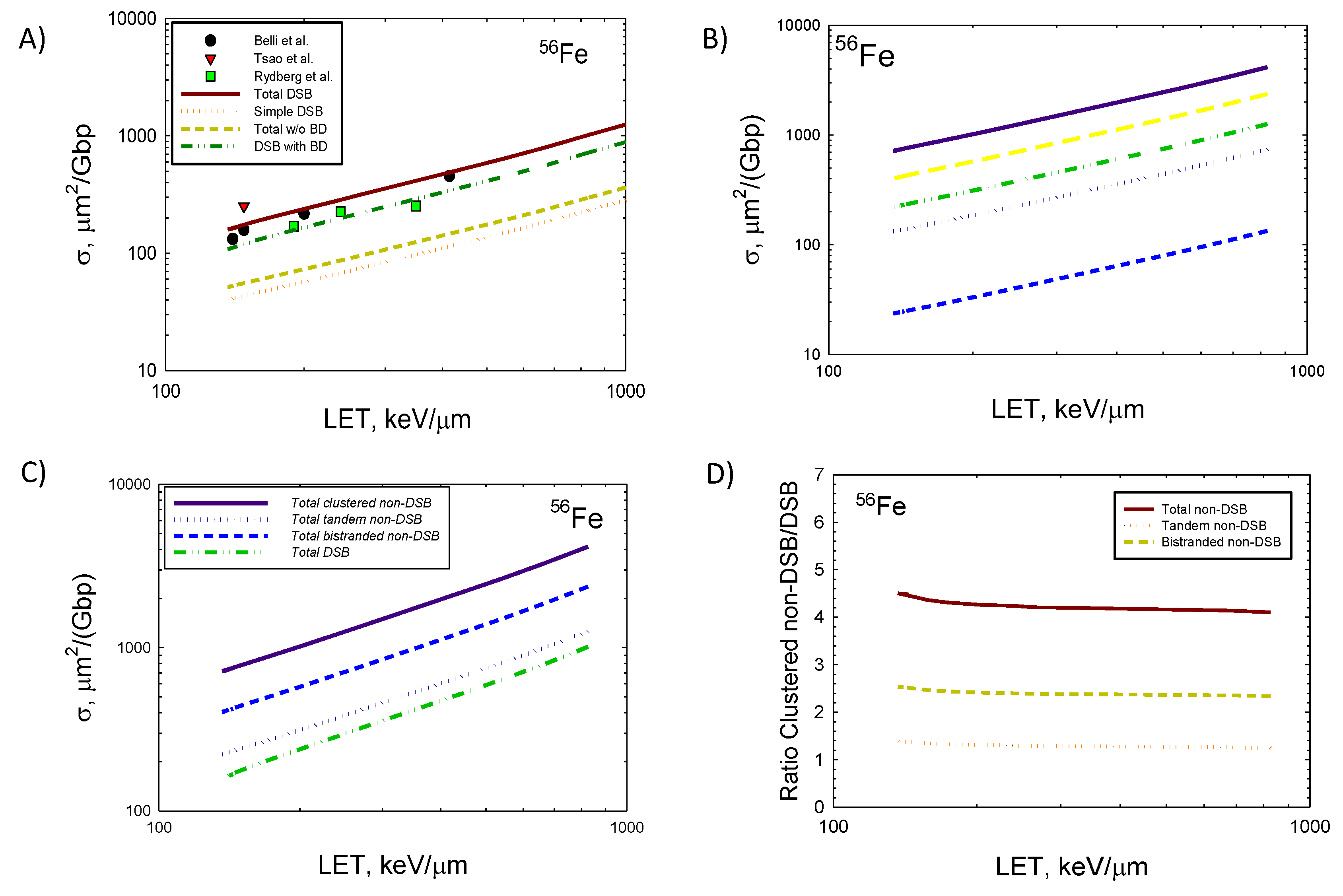

In

Figure 5 similar comparisons are made for

56Fe ions as made in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 for lighter ions. Calculations are shown here for kinetic energies of 50 to 10,000 MeV/u. Panel A shows comparison to experimental data using PFGE for human skin fibroblasts (HSF) [39,40], and human monocytes [7]. For

56Fe ions the very high ionization densities of particle tracks, especially at lower energies (<200 MeV/u) suggest that a 73 bp volume used herein is insufficient to describe all damage clusters. The ratio of non-DSB damage clusters to DSB is predicted to reach values >4 at relativistic energies and are reduced compared to the lighter ions described in

Figure 3 where ratios >5 were found.

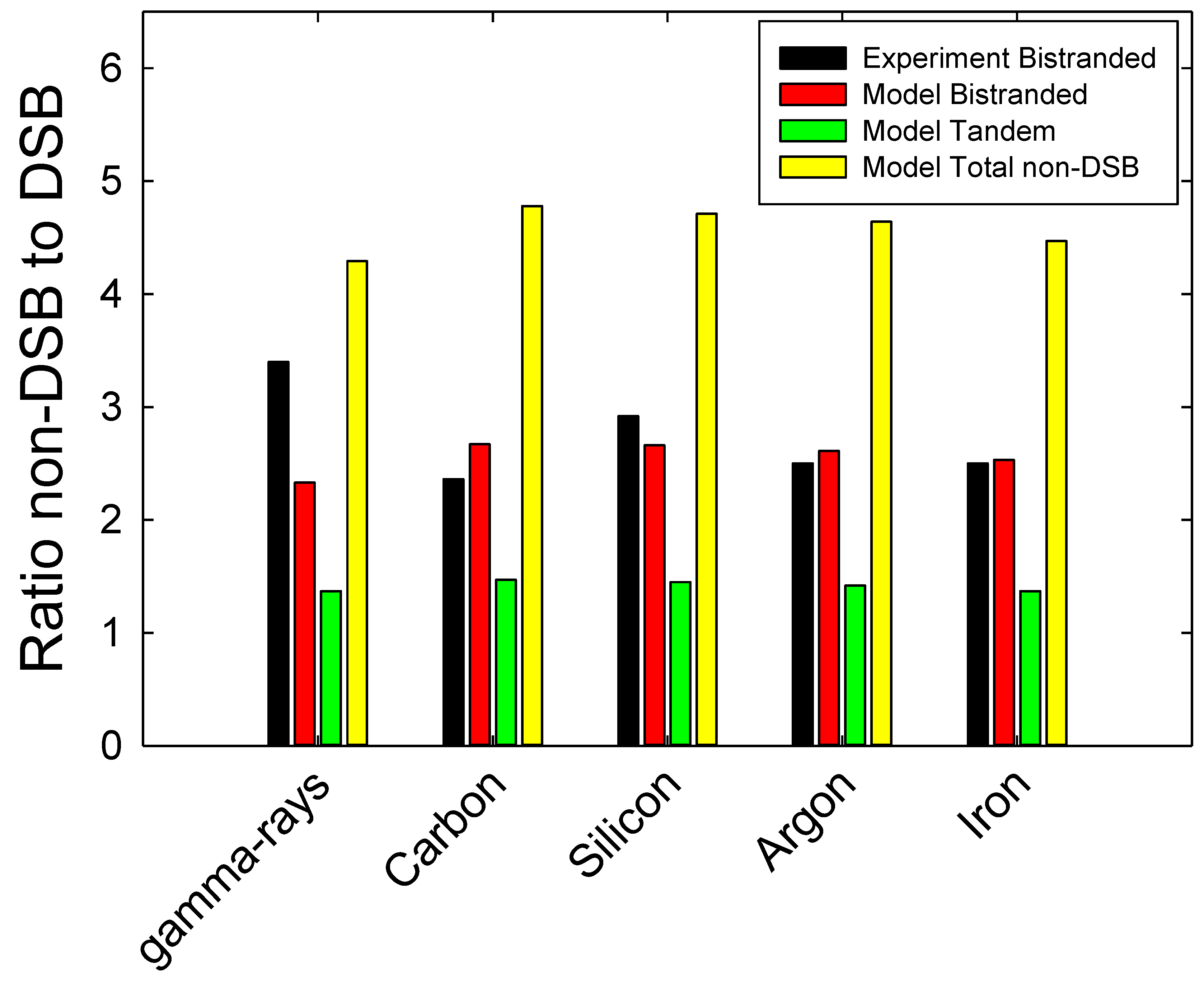

Direct comparison of the model to experimental data for non-DSB clusters is difficult because the model only scores the total bistranded or tandem clustered damage and not individual types such as oxidized and abasic sites. An assumption made here is that ionization energies or radical attack probabilities for different BD types would have similar probabilities. This is supported by experimental results [4,5,6,7], which find yields for different types are similar. It is expected that the detection of specific clustered non-DSB damages using Endo-III and Fpg enzyme sensitive sites have only a small overlap such that addition of yields of individual types is a valid approximation. In addition, Gulston et al. [6] and Sutherland et al. [5,43] note other limitations (besides lack of observation of tandem clustered damage) in the classes of non-DSB clustered damage scored by the use of enzymatic probes. Tokuyama et al. [8] reported relative contributions of DSBs, clustered EndoIII and Fpg sites in CHO-AA8 cells exposed to gamma-rays and several heavy ions species. I combined their EndoIII and Fpg data to estimate the ratio of bistranded non-DSB clustered damage to DSB as shown in

Figure 6 with comparison to the model results. The comparison for

12C,

28Si,

40Ar and

56Fe ions shows good agreement with the experiments for the ratios for bistranded non-DSB damage clusters to DSB, while the addition of tandem clusters predicts a large increase in the ratio. The comparison of model results for 100 keV electrons to experimental results for

137Cs gamma-rays is less satisfactory with the model estimated ratio for bistranded clustered damages to DSB about 40% lower than the experiment. This could point to needing improved representations of the electron distribution produced by gamma-rays at this energy.

Discussion

A novel approach to describing clustered DNA damage using multinomial probabilities was developed in a previous report [23] and extended in this paper to consider clustering probabilities for non-DSB bistranded and tandem clustered damage, and to improve the model description of indirect effects. In this approach the initial energy imparted spectrum is used to determine the initial number of elementary lesions and then folded with probabilities for direct and indirect effects leading to damage clustering. This approach uses multinomial probabilities to enumerate the spectra of clustered damage types that occur for increasing energy imparted to a small segment of DNA. The multinomial model favors mixture terms as the multinomial coefficients for a single lesion type tend to be smaller compared to mixture term coefficients, especially as the number of elementary lesions increases with increasing energy imparted. I used values of r1 and r2 parameters related to indirect effects from radical production on water molecules based on MC estimates [17] and the estimate from Scholes et al. [25]. The other key parameters are the values of q0 and q1 as a function of number of elementary lesions. These parameters are intuitively simple as being related to the spatial distribution of lesions produced by radiation tracks within an extended DNA segment. A simple binomial model is used in the present work to represent these coefficients as the number of elementary lesions is increased, while efforts to estimate these parameters from Monte-Carlo track simulations are being undertaken.

Clustered DNA damage includes both DSB and non-DSB damage sites, with non-DSB clustered damage shown in experiments [5,6,7,8,9] to be induced by ionizing radiation with a higher frequency than DSB, however only bistranded non-DSB clustered damages were measured in experiments. Base excision repair (BER) includes both short patch and long patch BER repair pathways [44] with long patch BER of clustered non-DSB damage often leading to delayed formation of DSB or mutations [10,11,12,13,45]. Delayed DSB resulting from non-DSB clustered damage has been observed in mammalian cells and also studied in plasmid DNA [46,47,48]. In addition, base damage is predicted to be contained in most DSB sites and it is possible that this additional damage could interfere with DSB damage processing [12,13,14,15]. This interference likely depends on the number of BD’s as well as their relative location within or nearby a DSB.

A main finding of the present report is the prediction that tandem non-DSB clustered damage occurs with a frequency of about 50% of that of bistranded damages and with frequencies that modestly decrease with increasing LET. This decrease is predicted to be larger for low energy ions where core ionizations dominate over penumbra effects from δ-rays. Predictions suggest the total burden of non-DSB clustered damages exceeds DSB by 4-to-6 fold with a dependence on LET. This suggest a larger focus on the health consequences from non-DSB damage clusters is needed in many areas, including low dose radiation protection and normal tissue effects in radiation cancer treatment.

The developed model provides a fast-computational method for electrons and ions using energy imparted spectra for a 5x5 nm cylindrical volume and a probabilistic framework for various clustered damage lesions. A main difference of the model to the more computational expensive application of stochastic MC-based radiation track simulations to model DNA damage [17,18,19,20,21] is the order of averaging in the approaches and the inclusion of detailed radiation chemistry models in MC simulations. Full MC track structure simulations average results over many MC histories using either volume models of DNA or scoring ionizations in atomistic DNA model structures, and then model radical production and decay related to indirect effects. The MC approach averages over the orientation of the track relative to the DNA structures, while simulations take many hours of cpu time on typical computer work stations and have largely not considered the role of BD. The present approach has CPU times <3 sec on standard computers to predict over 30 damage types for any radiation modality where frequency spectra are known. Because of the analytic methods developed statistical errors that occur in Monte-Carlo sampling do not occur. In addition, the present model uses a small number of parameters to include the contribution from indirect effects, and could serve as the basis for a semi-empirical approach to translate experimental results to describe complex radiation fields. This approach would have important applications in models used to cancer therapy with proton or heavy ion beams or space radiation studies where a large energy range and secondary radiation types arise due to nuclear interactions [49,50].

Acknowledgments

Funding support was thru the U.S. Department of Energy Award DE-SC0025298 and the University of Nevada Las Vegas.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Summary of 4th Order Terms in Mixtures of A, B and C Probabilities

Mixtures of

A and

B terms at 4

th order are found as the following:

Mixtures of

C with

A and

B terms at the 2

nd and 3

rd order found as the following:

Mixture terms of

A,

B and

C probabilities of the 4

th order are found as the following:

References

- Goodhead, D. Initial Events in the Cellular Effects of Ionizing Radiations: Clustered Damage in DNA. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1994, 65, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodhead, D.T.; Nikjoo, H. Track Structure Analysis of Ultrasoft X-rays Compared to High- and Low-LET Radiations. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1989, 55, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, J.F. DNA damage produced by ionizing radiation in mammalian cells: Identities, mechanisms of formation, and reparability. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1988, 35, 95–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, B.M.; Bennett, P.V.; Sidorkina, O.; Laval, J. Clustered DNA damages induced in isolated DNA and in human cells by low doses of ionizing radiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000, 97, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulston, M.; Fulford, J.; Jenner, T.; De Lara, C.; O'Neill, P. Clustered DNA damage induced by gamma radiation in human fibroblasts (HF19), hamster (V79-4) cells and plasmid DNA is revealed as Fpg and Nth sensitive sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 3464–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakilas, A.G.; Bennett, P.V.; Sutherland, B.M. High efficiency detection of bi-stranded abasic clusters in gamma-irradiated DNA by putrescine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 2800–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, D.; Kalogerinis, P.; Tabrizi, I.; Dingfelder, M.; Stewart, R.D.; Georgakilas, A.G. Induction and Processing of Oxidative Clustered DNA Lesions in56Fe-Ion-Irradiated Human Monocytes. Radiat. Res. 2007, 168, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuyuma, Y.; Furusawa, Y.; Ide, H.; Yasui, A.; Terato, H. Role of isolated and clustered DNA damage repair process in the effects of heavy ion irradiation. J. Radiat. Res. 2015, 56, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, T.; Akamatsu, K.; Tsuda, M.; Tujimoto, A.; Hirayama, R.; Hiromoto, T.; Tamada, T.; Ide, H.; Shikazono, N. Formation of clustered DNA damage in vivo upon irradiation with ionizing radiation: Visualization and analysis with atomic force microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulston, M.; de Lara, C.; Jenner, T.; Davis, E.; O’Neill, P. Processing of clustered DNA damage generates additional double-strand breaks in mammalian cells post-irradiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1602–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunniffe, S.; Walker, A.; Stabler, R.; O’neill, P.; Lomax, M.E. Increased mutability and decreased repairability of a three-lesion clustered DNA-damaged site comprised of an AP site and bi-stranded 8-oxoG lesions. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2014, 90, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobbs, T.A.; Palmer, P.; Maniou, Z.; Lomax, M.E.; O’nEill, P. Interplay of two major repair pathways in the processing of complex double-strand DNA breaks. DNA Repair 2008, 7, 1372–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, K.; Purkayastha, S.; Neumann, R.D.; Pastwa, E.; Winters, T.A. Base Damage Immediately Upstream from Double-Strand Break Ends is a More Severe Impediment to Nonhomologous End Joining than Blocked 3′-Termini. Radiat. Res. 2011, 175, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomax, M.E.; Folkes, L.K.; O’Neill, P. Biological consequences of radiation-induced DNA damage: Relevance to radiotherapy. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 25, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipler, A.; Illiakis, G. DNA double-strand–break complexity levels and their possible contributions to the probability for error-prone processing and repair pathway choice. Nucl. Acids Res. 2013, 41, 7589–7605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, D.; Nikjoo, H.; Humm, J. Calculation of Initial Yields of Single- and Double-strand Breaks in Cell Nuclei from Electrons, Protons and Alpha Particles. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1989, 56, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikjoo, H.; O'Neill, P.; Terrissol, M.; Goodhead, D. Modelling of Radiation-induced DNA Damage: The Early Physical and Chemical Event. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1994, 66, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikjoo, H.; O'Neill, P.; Goodhead, D.T.; Terrissol, M. Computational modelling of low-energy electron-induced DNA damage by early physical and chemical events. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1997, 71, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, R.; Rahmanian, S.; Nikjoo, H. Spectrum of Radiation-Induced Clustered Non-DSB Damage – A Monte Carlo Track Structure Modeling and Calculations. Radiat. Res. 2015, 183, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland, W.; Dingfelder, M.; Kundrát, P.; Jacob, P. Track structures, DNA targets and radiation effects in the biophysical Monte Carlo simulation code PARTRAC. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2011, 711, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzipapas, K.P.; Papadimitroulas, P.; Obeidat, M.; et al. Quantification of DNA double-strand breaks using Geant4-DNA. Med. Phys. 2019, 46(1), 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuemann, J.; McNamara, A.L.; Warmenhoven, J.W.; Henthorn, N.T.; Kirkby, K.J.; Merchant, M.J.; Ingram, S.; Paganetti, H.; Held, K.D.; Ramos-Mendez, J.; et al. A New Standard DNA Damage (SDD) Data Format. Radiat. Res. 2018, 191, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, F.A. Modeling Clustered DNA Damage by Ionizing Radiation Using Multinomial Damage Probabilities and Energy Imparted Spectra. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.A.; Krishnakumar, E. Communication: Electron ionization of DNA bases. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 144, 161102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholes, G.; Ward, J.; Weiss, J. Mechanism of the radiation-induced degradation of nucleic acids. J. Mol. Biol. 1960, 2, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paretzke, H.G.; Turner, J.E.; Hamm, R.N.; Ritchie, R.H.; Wright, H.A. Spatial Distributions of Inelastic Events Produced by Electrons in Gaseous and Liquid Water. Radiat. Res. 1991, 127, 121–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, C.A.; Sargent, D.F.; Luger, K.; Maeder, A.W.; Richmond, T.J. Solvent Mediated Interactions in the Structure of the Nucleosome Core Particle at 1.9Å Resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 319, 1097–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikjoo, H.; Goodhead, D.T.; Charlton, D.E.; Paretzke, H.G. Energy deposition by small cylindrical volumes by monoelectric electrons. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1991, 60, 739–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikjoo, H.; Goodhead, D.T.; Charlton, D.E.; Paretzke, H.G. Energy deposition by monoenergetic electrons in cylindrical volumes. MRC Radiobiology Unit Monograph 94/1, Chilton U.K, 1994.

- Cucinotta, F.A.; Nikjoo, H.; Goodhead, D.T. Model of the radial distribution of energy imparted in nanometer volumes from HZE particles. Radiat. Res. 2000, 153, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, F.A.; Katz, R.; Wilson, J.W. Radial distribution of electron spectra from high-energy ions. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 1998, 37, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, T.; Delara, C.; O'Neill, P.; Stevens, D. Induction and Rejoining of DNA Double-strand Breaks in V79-4 Mammalian Cells Following γ- and α-irradiation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1993, 64, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Belli, M.; Cherubini, R.; Dalla Vecchia, M.; Dini, V.; Moschini, G.; Signoretti, C.; Simone, G.; Tabocchini, M.A.; Tiveron. P. DNA DSB induction and rejoining in V79 cells irradiated with light ions: a constant field gel electrophoresis study. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2000, 76, 1095–1104.

- Frankenberg, D.; Brede, H.J.; Schrewe, U.J.; Steinmetz, C.; Frankenberg-Schwager, M.; Kasten, G.; Pralle, E. Induction of DNA Double-Strand Breaks by 1 H and 4 He Ions in Primary Human Skin Fibroblasts in the LET Range of 8 to 124 keV/mm. Radiat. Res. 1999, 151, 540–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rydberg, B.; Heilbronn, L.; Holley, W.R.; Löbrich, M.; Zeitlin, C.; Chatterjee, A.; Cooper, P.K. Spatial Distribution and Yield of DNA Double-Strand Breaks Induced by 3–7 MeV Helium Ions in Human Fibroblasts. Radiat. Res. 2002, 158, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prise, K.M.; Ahnström, G.; Belli, M.; Carlsson, J.; Frankenberg, D.; Kiefer, J.; Loöbrich, M.; Michael, B.D.; Nygren, J.; Simone, G.; et al. A review of dsb induction data for varying quality radiations. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1998, 74, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikpeme, S.; Löbrich, M.; Akpa, T.; Schneider, E.; Kiefer, J. Heavy ion-induced DNA double-strand breaks with yeast as a model system. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 1995, 34, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, J.; Taucher-Scholz, G.; Kraft, G. Induction of DNA Double-strand Breaks in CHO-K1 Cells by Carbon Ions. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1995, 68, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydberg, B. Clusters of DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation: Formation of short DNA fragments II. Experimental detection. Radiat. Res. 1996, 145, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belli, M.; Campa, A.; Dini, V.; Esposito, G.; Furusawa, Y.; Simone, G.; Sorrentino, E.; Tabocchini, M.A. DNA Fragmentation Induced in Human Fibroblasts by Accelerated56Fe Ions of Differing Energies. Radiat. Res. 2006, 165, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roots, R.; Chatterjee, A.; Chang, P.; Lommel, L.; Blakely, E. Characterization of Hydroxyl Radical-induced Damage after Sparsely and Densely Ionizing Irradiation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1985, 47, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taucher-Scholz, G.; Kraft, G. Influence of Radiation Quality on the Yield of DNA Strand Breaks in SV40 DNA Irradiated in Solution. Radiat. Res. 1999, 151, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, B.M.; Bennett, P.V.; Sidorkina, O.; Laval, J. Clustered Damages and Total Lesions Induced in DNA by Ionizing Radiation: Oxidized Bases and Strand Breaks. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 8026–8031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, S. DNA Damages Processed by Base Excision Repair: Biological Consequences. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1994, 66, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, T.; Akamatsu, K.; Kohzaki, M.; Tsuda, M.; Hirayama, R.; Sassa, A.; Yasui, M.; I Shoulkamy, M.; Hiromoto, T.; Tamada, T.; et al. Deciphering repair pathways of clustered DNA damage in human TK6 cells: insights from atomic force microscopy direct visualization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoya, A.; Cunniffe, S.M.T.; Watanabe, R.; Kobayashi, K.; O'Neill, P. Induction of DNA Strand Breaks, Base Lesions and Clustered Damage Sites in Hydrated Plasmid DNA Films by Ultrasoft X Rays around the Phosphorus K Edge. Radiat. Res. 2009, 172, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushigome, T.; Shikazono, N.; Fujii, K.; Watanabe, R.; Suzuki, M.; Tsuruoka, C.; Tauchi, H.; Yokoya, A. Yield of Single- and Double-Strand Breaks and Nucleobase Lesions in Fully Hydrated Plasmid DNA Films Irradiated with High-LET Charged Particles. Radiat. Res. 2012, 177, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahbani, S.K.; Girouard, S.; Cloutier, P.; Sanche, L.; Hunting, D.J. The Relative Contributions of DNA Strand Breaks, Base Damage and Clustered Lesions to the Loss of DNA Functionality Induced by Ionizing Radiation. Radiat. Res. 2014, 181, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, F.A.; Plante, I.; Ponomarev, A.L.; Kim, M.-H.Y. Nuclear interactions in heavy ion transport and event-based risk models. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2011, 143, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, F.A.; Cacao, E. Non-Targeted Effects Models Predict Significantly Higher Mars Mission Cancer Risk than Targeted Effects Models. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).