Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

14 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

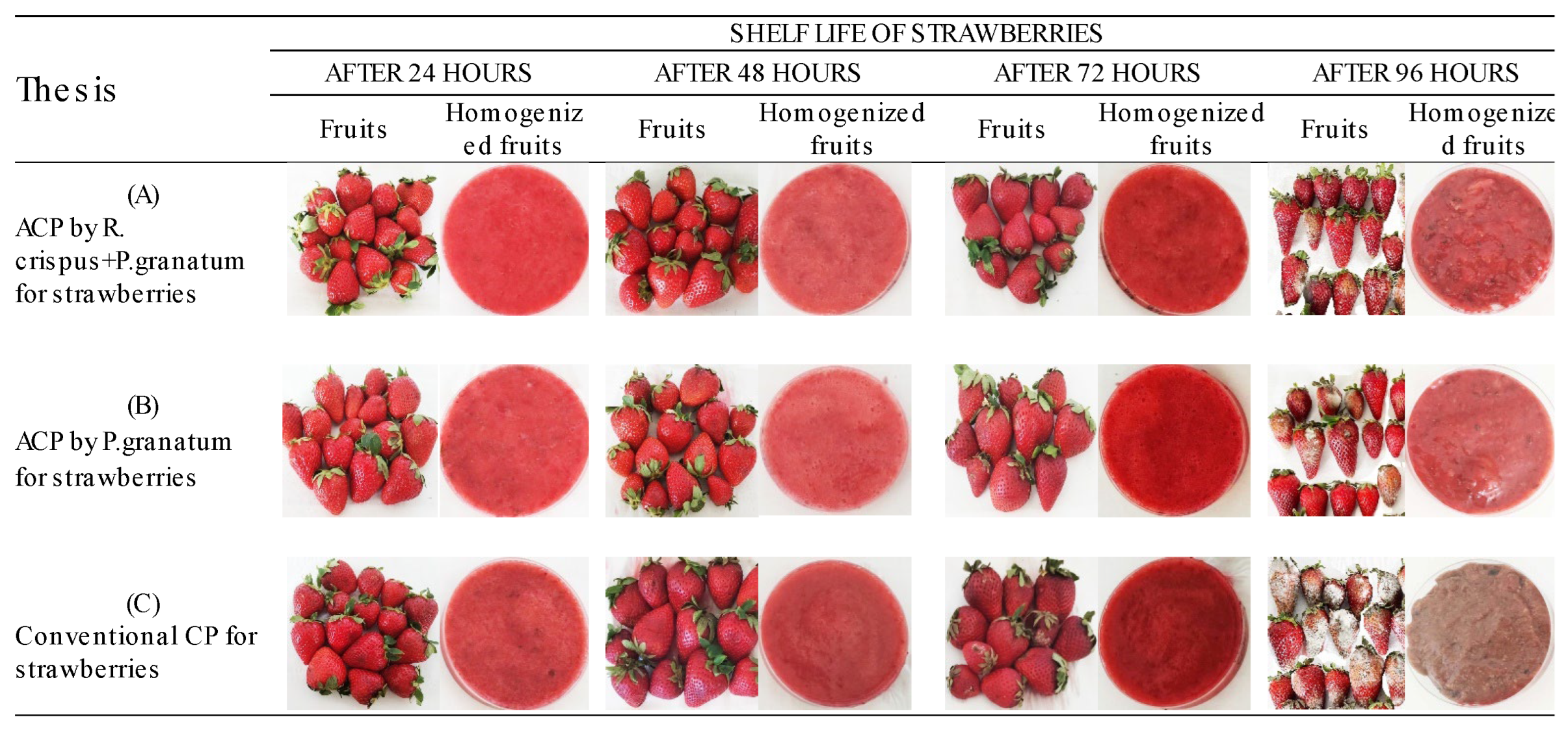

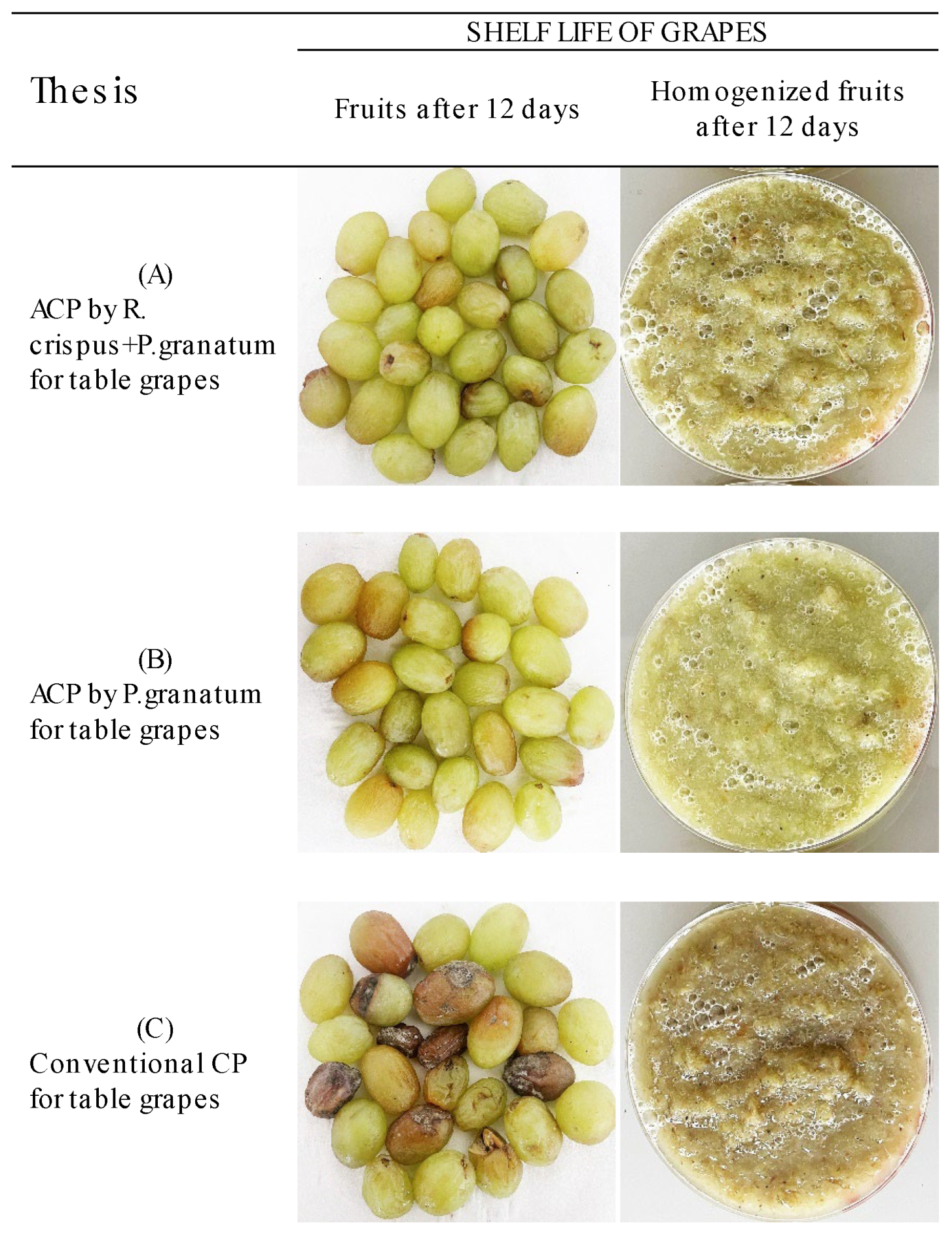

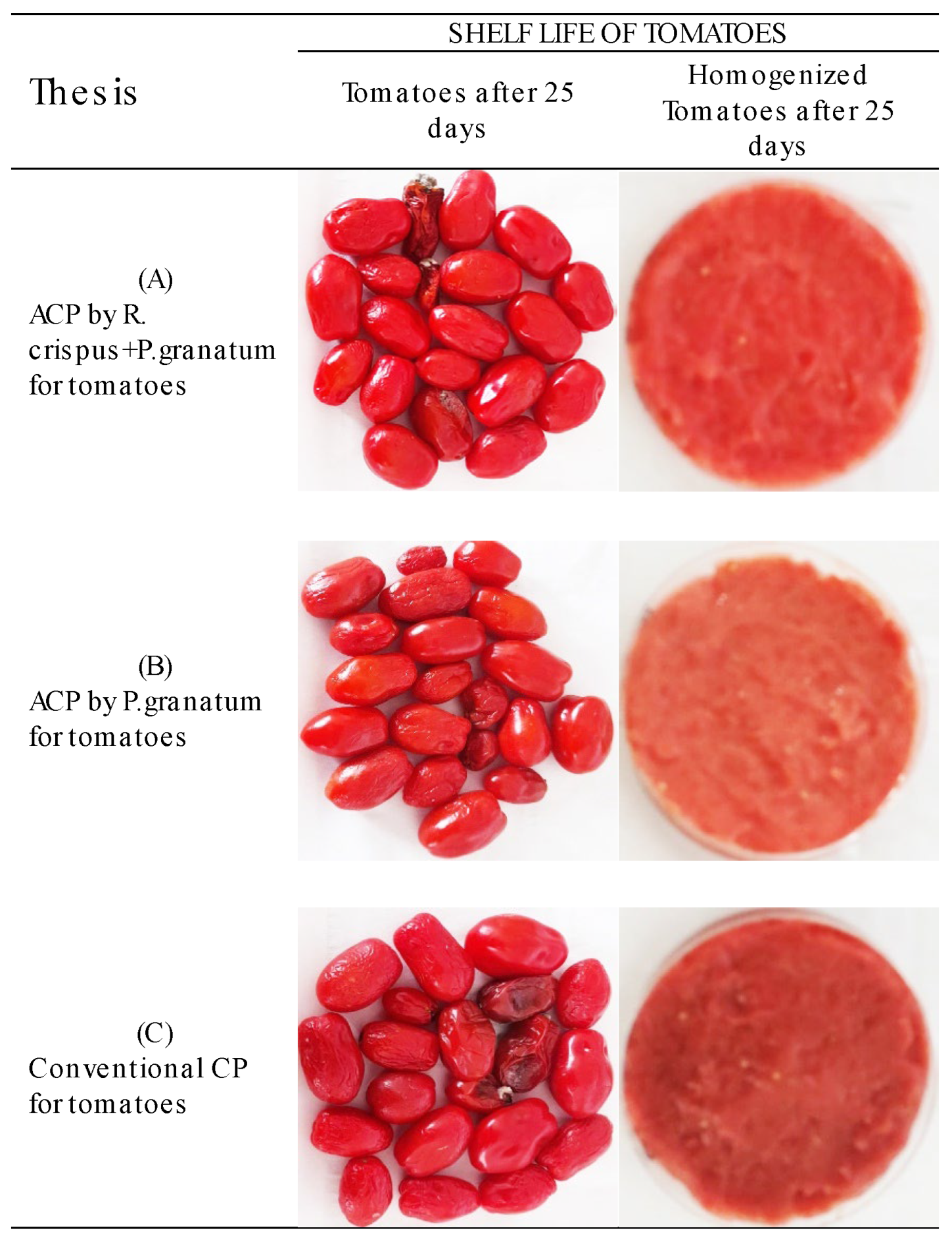

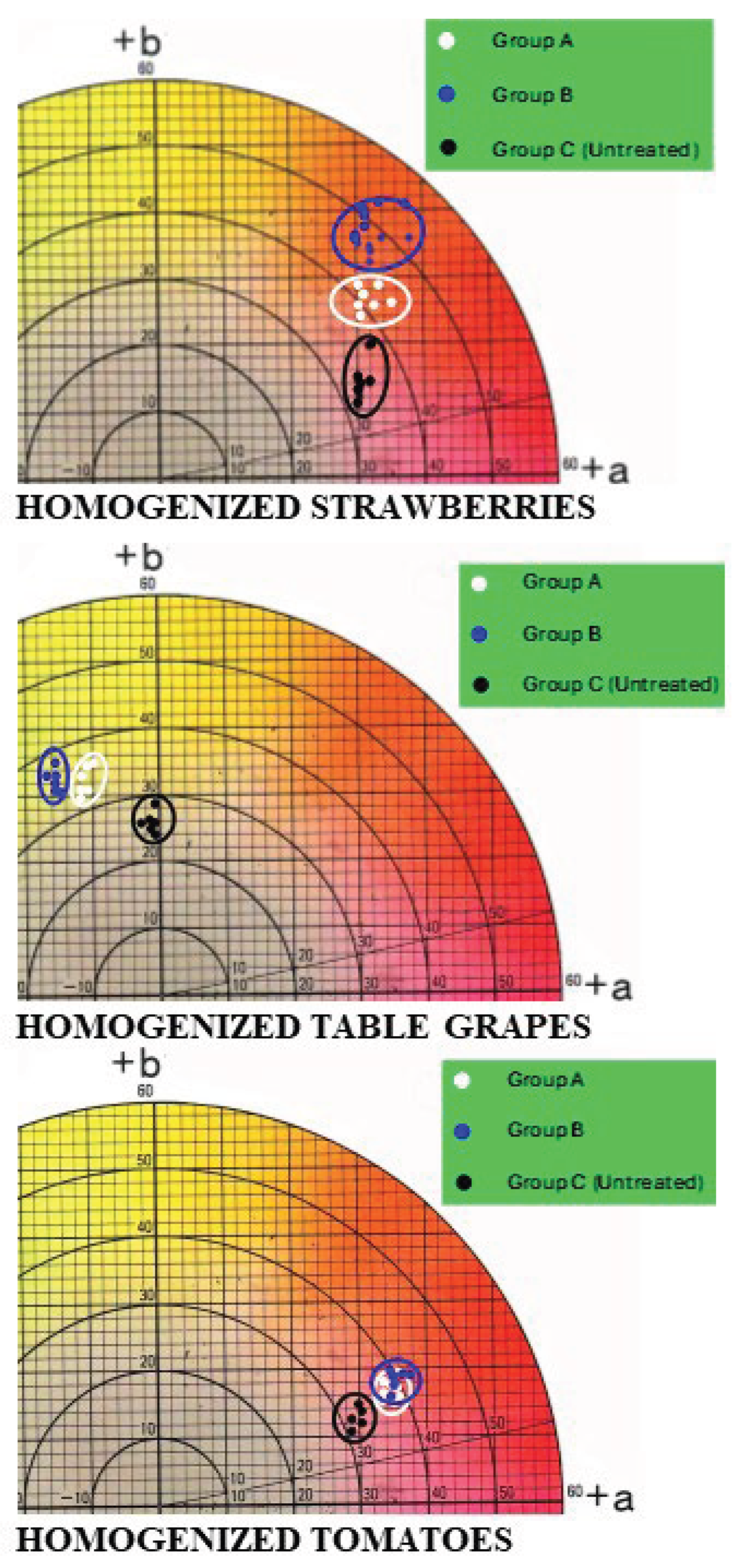

Packaging plays a crucial role in extending the shelf life of fresh fruits and vegetables, thereby preserving their quality characteristics throughout the supply chain. Packaging systems treated with natural compounds can replace synthetic packaging systems. This study aimed to evaluate the potential application of Active Cardboard Packaging (ACP) in preserving fruit quality and extending its shelf life. We observed the effect of cardboard packaging containing Punica granatum peel extract (PPGE) and Rumex crispus root extract (RRCE) on the shelf life of strawberries, tomatoes, and table grapes. In vitro and in vivo tests demonstrated the ability of these extracts to inhibit fungal growth. It can be hypothesized that RRCE+PPGE and PPGE, once incorporated into the packaging, create a system capable of inhibiting microbial growth, thus prolonging the freshness and marketability of the fruit. Quality was also assessed by measuring the surface color of homogenized strawberries, tomatoes, and grapes using a spectrophotometer. This study offers a novel approach to extending the shelf life of fruits and vegetables.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Extracts Used

In Vitro Tests

In Vivo Tests

Color of the Homogenized Fruits

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. In Vitro Tests

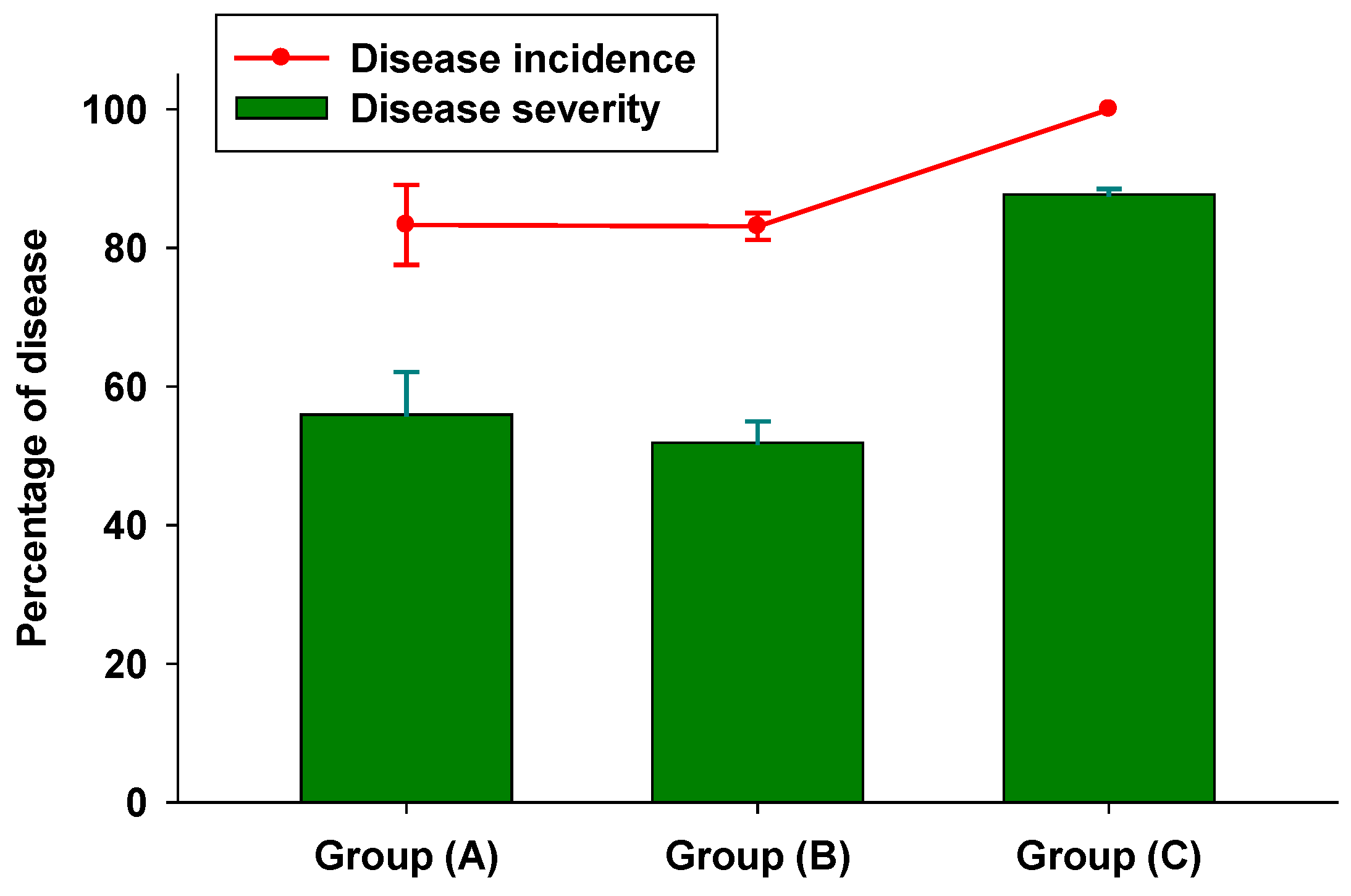

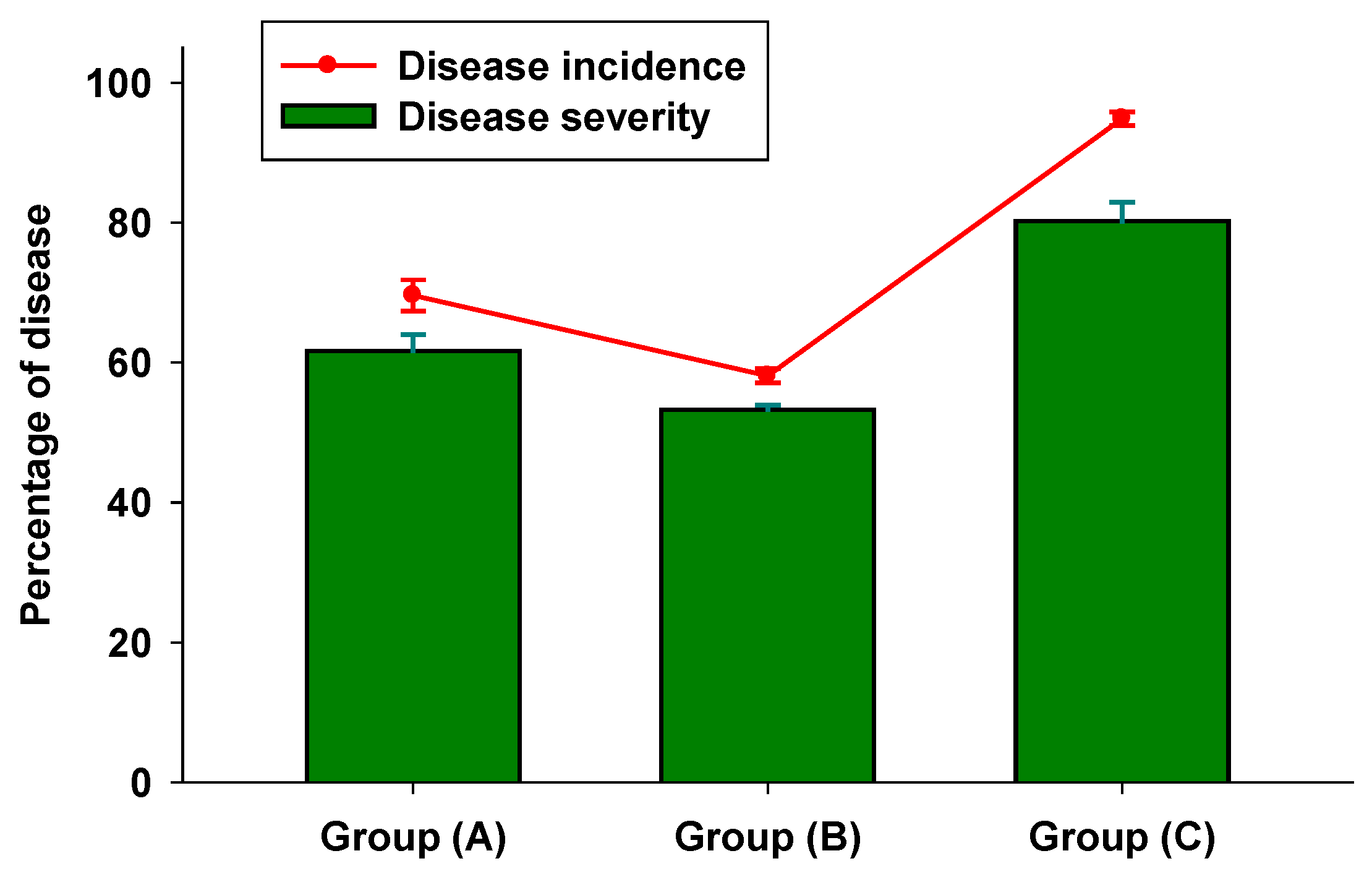

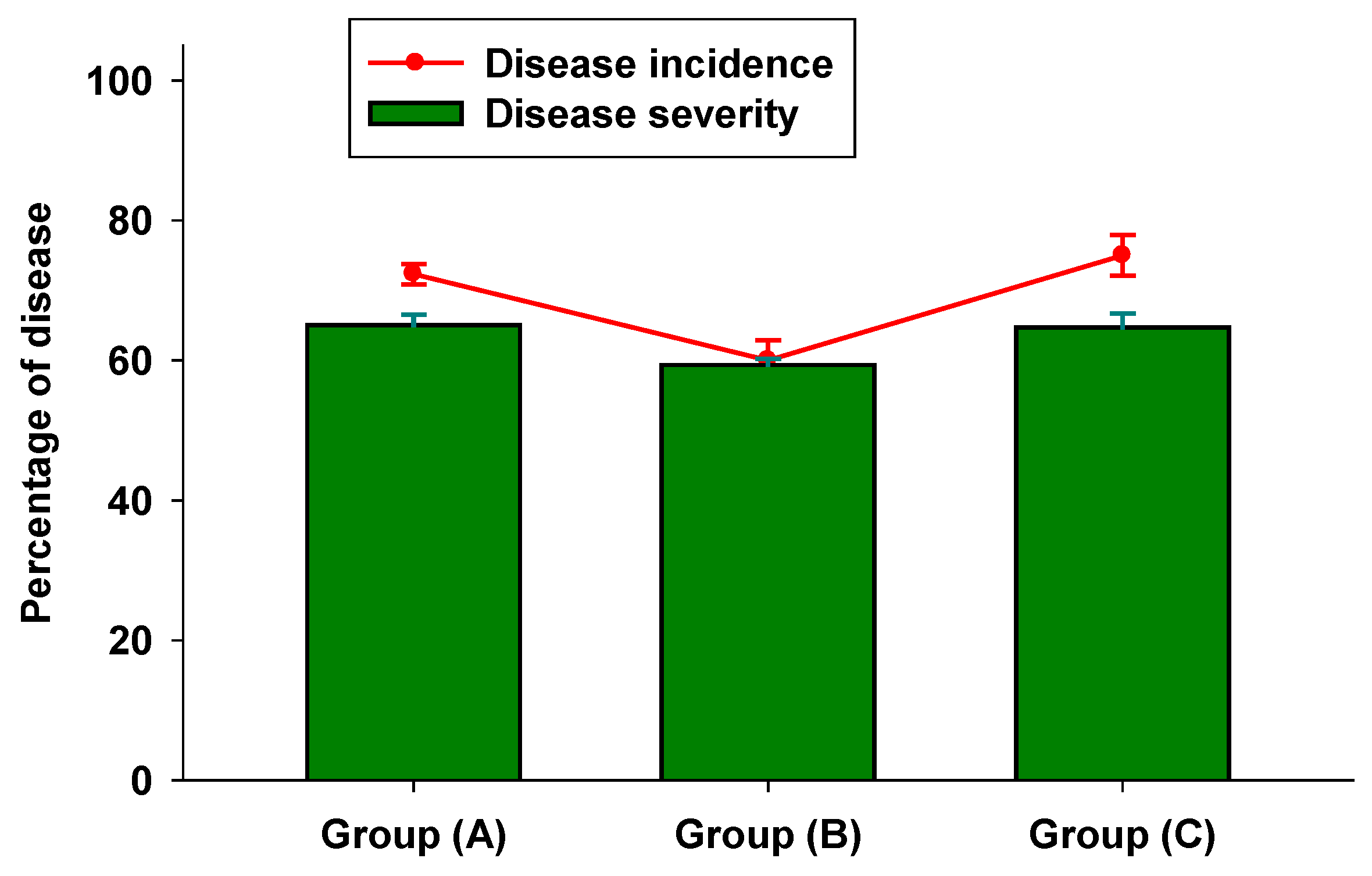

3.2. In Vivo Tests

3.3. Colorimetric Parameters

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kader, A.A. Postharvest biology and technology. In: Kader AA, editor. Postharvest Technology of Horticultural Crops. Davis, CA: University of California, Agriculture and natural resources 2002, 39-48.

- Merino, D.; Quilez-Molina A. I.; Perotto, G.; Bassani, A.; Spigno G and Athanassiou A. A second life for fruit and vegetable waste: a review on bioplastic films and coatings for potential food protection applications. Green Chemistry 2022, 24 (12): 4703-4727.

- Priyadarshi, R.; Ghosh, T.; Purohit, S.D.; Prasannavenkadesan, V.; and Rhim, J-W. Lignin as a sustainable and functional material for active food packaging applications: A review. Journal of Cleaner Pro-duction 2024, 469. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y H.; Tsou C.H.; De Guzman, M.R.; Huang, D.; Yu YQ.; Gao C, Zhang, X M.; Du, J.; Zheng, Y T.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Z H. Antibacterial nanocomposite films of poly (vinyl alcohol) modified with zinc oxide-doped multiwalled carbon nanotubes as food packaging. Polymer Bulletin 2022, 79(1), 3847-3866. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xia, M.; Wei, X.; Xu, C.; Luo Z.; Mao, L. Consolidated cold and modified atmosphere package system for fresh strawberry supply chains. LWT 2019, 109(2), 207-215. [CrossRef]

- Emamifar, A.; Ghaderi, Z.; Ghaderi, N. Effect of salep-based edible coating enriched with grape seed extract on postharvest shelf life of fresh strawberries. Journal of Food Safety 2019, 39 (6), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Dudley, E.; G. Antimicrobial-coated films as food packaging: a review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2021, 20 (4), 3404-3437. [CrossRef]

- Massad-Ivanir, N.; Sand, A.; Nitzan, N.; Valderama, E.; Kurczewski, M.; Remde, H.; Wegenberger, A.; Shlosman, K.; Shemesh, R.; Störmer, A.; Segal, E. Scalable production of antimicrobial food packaging films containing essential oil-loaded halloysite nanotubes. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2023, 37, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Ratna, Aprilia, S.; Arahman, N.; Bilad, M R.; Suhaimi, H.; Munawar, A A.; Nasution, I.S. Bio-Nanocomposite based on edible gelatin film as active packaging from clarias gariepinus fish skin with the addition of cellulose nanocrystalline and nanopropolis. Polymers 2022, 14(18), 3738. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Almagro, N.; Herrero-Herranz, M.; Guri, S.; Corzo, N.; Montilla, A.; Villamiel, M. Application of sunflower pectin gels with low glycemic index in the coating of fresh strawberries stored in modi-fied atmospheres. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2021, 101(14), 5775-5783. [CrossRef]

- Iriani, E S.; Permana, AW.; Yuliani, S.; Kailaku, S.I.; Sulaiman, A A. The effect of agricultural waste nanocellulose on the properties of bioplastic for fresh fruit packaging. IOP Conference Series Earth and Environmental Science 2019, 309(1), 012035. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M A.; Barbosa, C H.; Cerqueira, M A.; Azevedo A G.; Barros C, Machado A.V.; Coelho, A.; Furtado, R.; Correia, C B.; Saraiva, M.; Vilarinho, F.; Silva A.S.; Ramos, F. PLA films loaded with green tea and rosemary polyphenolic extracts as an active packaging for almond and beef. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2023, 36,10. [CrossRef]

- Crisosto, C. H.; Michell, F.G. Postharvest handling systems: small fruits. In Kader AA., editor. Postharvest Technology of Horticultural Crops. Davis, CA: Center, UC Postharvest Technology 2020, 357-363.

- López- Gómez, A.; Ros-Chumillas, M.; Buendía-Moreno, L.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. Active cardboard packaging with encapsulated essential oils for enhancing the shelf life of fruit and vegetables. Frontiers in Nutrition 2020, 7. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhou, D., Wang, Z.; Tu, S.; Shao, X.; Peng, J.; Pan, L.; Tu, K. Hot air treatment reduces postharvest decay and delays softening of cherry tomato by regulating gene expression and activities of cell wall- degrading enzymes. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2018, 98 (6), 2105-2112. [CrossRef]

- López-Camelo, A F.; Gómez, P A. Comparison of color indexes for tomato ripening. Horticultura Brasileira 2004, 22 (3), 534-537. [CrossRef]

- Champa, H. Pre and post-harvest practices for quality improvement of table grapes (Vitis vinifera L.). Journal of the National Science Foundation of Sri Lanka 2015, 43(1), 3-9. [CrossRef]

- Elad, Y.; Vivier, M.; Fillinger, S. Botrytis, the good, the bad and the ugly. In Botrytis –The Fungus, the Pathogen and its Management in Agricultural Systems; Fillingers, S., Elad, Y., Vivier, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany 2015, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, M T.; de Aguiar, A.C.; Rodrigues, N.; Leles, N R.; Ribeiro, L.T.M.; Bosso, B.E.C.; Yamashita, F.; Youssef, K.; Ruffo, R.S. Active Packaging Systems to Extend the Shelf Life of ‘Italia’ Table Grapes. Horticulturae 2024, 10(3), 214; https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae10030214.

- Priyadarshi, R.; Jayakumar, A.; Krebs de Souza, C.; Rhim, J.W.; Kim, J.T. Advances in strawberry postharvest preservation and packaging: A Comprehensive review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2024, 23(4). [CrossRef]

- Ratna; R.; Aprilia, S.; Arahman, N.; Munawar, A.A. Effect of edible film gelatin nano-biocomposite packaging and storage temperature on the store quality of strawberries (Fragaria x ananassa var. duchesne). Future Foods 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Rongai, D.; Pulcini, P.; Pesce, B.; Milano, F. Antifungal activity of pomegranate peel extract against fusarium wilt of tomato. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2016, 147(1), 229–238. [CrossRef]

- Soleimanzadeh, A.; Mizani, S.; Mirzaei, G.; Bavarsad, E T.; Farhoodi, M.; Esfanadiari, Z., Rastami; M. Recent advances in characterizing the physical and functional properties of active packaging films containing pomegranate peel. Food Chemistry 2024, 22. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, U A.; Carle, R.; Kammerer, D.R. Identification and quantification of phenolic compounds from pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel, mesocarp, aril and differently produced juices by HPLC-DAD–ESI/MSn. Food Chemistry 2011, 127, 807–821. [CrossRef]

- Bodbodak, S.; Shahabi, N.; Mohammadi, M.; Ghorbani, M.; Pezeshki, A. Development of a novel an-timicrobial electrospun nanofiber based on polylactic acid/hydroxypropyl methylcellulose con-taining pomegranate peel extract for active food packaging. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2021, 14(5), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N., Daniloski, D., Pratibha, Neeraj, D’Cunha, N.M.; Naumovski, N.; Trajkovska, Petkoska, A. Pomegranate peel extract – A natural bioactive addition to novel active edible packaging. Food Research International 2022, 156. [CrossRef]

- Mandefro, S.B.; Jabasingh, A.S.; Tefera, Z.T., Abebe, A A. Rumex crispus L: profiling and evaluation of the phytochemical properties, antioxidant potential, and antimicrobial activities of the root ex-tracts. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2024, 15(5), 7005-7020. [CrossRef]

- Bektašević, M.; Oraščanin, M.; Šertović, E. Biological activity and food potential of plants Rumex crispus L. and Rumex obtusifolius L.- a review. Technological Acta 2022, 15(1), 61-67. [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Singh, J P.; Kaur, A.; Singh, N. Phenolic compounds as beneficial phytochemicals in pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel: a review. Food Chemistry 2018, 261, 75-86. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, S.; Kaur, K.; Sharma, M. Extraction methods and bioactive compounds from pomegranate peels: A comprehensive review for sustainable packaging applications. Food Biomacro-molecules 2025, 2(1), 42-68. [CrossRef]

- Dey, D.; Debnath, S.; Hazra, S.; Ghosh, S.; Ray, R.; Hazra, B. Pomegranate Pericarp Extract Enhances the Antibacterial Activity of Ciprofloxacin Against Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL) and Metallo-β-Lactamase (MBL) Producing Gram-Negative Bacilli. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2020, 50(12), 4302–4309. [CrossRef]

- Lacivita, V.; Lordi, A.; Posati, T., Zamboni, R.; Del Nobile, M.A.; Conte, A. Pomegranate Peel Powder: In Vitro Efficacy and Application to Contaminated Liquid Foods. Foods 2023,12(6),1173. [CrossRef]

- Rongai, D.; Sabatini, N.; Pulcini; P.; Di Marco, C.; Storchi, L.; Marrone A. Effect of pomegranate peel extract on shelf life of strawberries: computational chemistry approaches to assess antifungal mechanisms involved. Journal of Food Science and Technology 2018, 55(7), 2702-2711. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Abrar, M.; Sultan, M.T.; Din, A.; Niaz, B. Post-harvest physicochemical changes in full ripe strawberries during cold storage. The Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences 2011,21(1),38-41.

- Ali, M Q.; Ahmad, N.; Azhar, M.A.; Abdul Munaim, M.S.; Hussain, A.; Ali, Mahdi A. An overview: exploring the potential of fruit and vegetable waste and by-products in food biodegradable packaging. Discover Food 2024, 4:130. [CrossRef]

- Utami, R.; Kawiji, K.; Atmaka, W.; Nurmaya, L.; Khasanah, L.U.; Manuhara, G.J. The effect of active paper packaging enriched with oleoresin from solid waste of pressed Curcuma xanthorrhiza Roxb. Placement methods on quality of refrigerated strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa). Caraka Tani Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 2021, 36(1), 155-164. [CrossRef]

- Nadim, Z.; Ahmadi, E.; Sarikhani, H.; Amiri Chayjan, R. Effect of methylcellulose-based edible coating on strawberry fruit’s quality maintenance during storage. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2014, 39(1),80-90. [CrossRef]

- Geransayeh, M.; Sepahvand, S.; Abdossi, V.; Nezhad, R.A. Effect of thymol treatment on decay, postharvest life and quality of strawberry (Fragaria ananassa) fruit cv. “Gaviota”. International. Journal of Agronomy & Agriculural Research 2015, 6(4), 151-162.

- Rusková, M.; Opálkova Šiškova, A.; Mosnáčkova, K.; Gago C., Guerreiro, A., Bučkova, M.; Puškárová, A.; Pangallo, D.; Dulce Antunes, M. Biodegradable active packaging enriched with essential oils for enhancing the shelf life of strawberries. Antioxidants 2023,12 (3),755. [CrossRef]

- Darwish, O.S.; Ali M R.; Khojah, E.; Samra, B.N.; Ramadan, K.M.A; El-Mogy, M M. Pre-Harvest appli-cation of salicylic acid, abscisic acid, and methyl jasmonate conserve bioactive compounds of strawberry fruits during refrigerated storage 2021, 7(12), 568; https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7120568.

- Bahmani, R.; Razavi, F.; Mortazavi, S.N., Gohari, G.; Juárez-Maldonado, A. Evaluation of pro-line-coated chitosan nanoparticles on decay control and quality preservation of strawberry fruit (cv. Camarosa) during cold storage. Horticulturae 2022, 8(7), 648; https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8070648.

- Taechutrakul, S.; Netpradit., S.; Tanprasert, K. Development of recycled paper-based ethylene scavenging packages for tomatoes. Acta Horticulturae 2009, 837,365-370.

- García- García, I.; Toboada-Rodríguez, A.; López-Gomez, A.; Marín, F. Active packaging of cardboard to extend the shelf life of tomatoes. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2013, 6, 754-761. [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Doses | Mycelia growth | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F. oxysporum | B. cinerea | ||||

| % | mm | mm | |||

| Untreated control | 50.0 | a | 50.0 | a | |

| RRCE+PPGE | 1 | 17.0 | b | 17.9 | b |

| PPGE | 1 | 10.4 | c | 14.0 | c |

| Fungicide | 0.15 | 16.1 | b | 16.6 | b |

| F=10.298 P<0.005 |

F=60.415 P<0.001 |

||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).