1. Introduction

Apprehensions over quality education have been the area of focus for the longest time across the globe, with scholars lamenting the lack of this quality, thereof, in the South African rural context. In the quest of ensuring quality education globally, literacy remains central and the fundamental catalyst to achieving sustainable and lifelong learning as well as social fairness (McKay, 2018). Literature attests that literacy, as a versatile component in the education sphere, accelerates the achievement of various Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) including SDG4, which advocates for quality education that is focused on inclusivity and learning opportunities for all (Shafira, Ramadhani & Rachman, 2024; Syafitri, Sutiawati, & Rachman, 2024). As literacy equips learners with knowledge and skills that enhance their educational attainment and social well-being, it therefore, links directly with sustainable development, especially in rural areas (UNESCO, 2022; Ali, Solfema & Putri, 2025). According to Merga (2021), at the nexus of the goals are school libraries, with Seasholes, Kimery & Kaaland (2023) attributing that libraries have evolved from being just mere repositories of information into dynamic learning hubs that support quality education goals. Latterly, the school libraries, as axis that align and progress access that is equitable, have been placed as key elements towards sustainable integration of economic, social and environmental consciousness (Igbinovia, 2022).

Extant literature believes that libraries in general as well as school libraries are an educational investment that would yield effective teaching and learning. Merga (2020) calls for integration of school libraries into the whole school system to enhance inclusivity in teaching and learning. The scholar attests that school libraries strengthen emotional and cognitive well-being of learners (Merga, 2020). The instructional leadership framework of a school as Lewis (2021) puts it, becomes enhanced when school libraries and their librarians work hand in hand with teachers as such collaboration promotes professional learning. School libraries provide support to teaching and learning as they offer additional materials and therefore promoting independent and self-directed learning (Anggraeni, & Riady, 2024; Schultz-Jones, Farabough & Hoyt, 2021; Mahwasane, 2022). Focusing on STEAM education Wine, Pribesh, Kimmel, Dickinson & Church (2023) argue that school libraries improve learner reading culture and develop critical thinking skills which are significant to all subjects including STEAM education subjects. Otero (2024) adds the potential of school libraries in strengthening school leadership and management in school improvement plans by promoting integration of resources and literacy culture.

Globally, there are visible strides in various countries on investments made towards school libraries as literature validates the effectiveness integrating libraries with pedagogical practices. The effectiveness of integrating libraries with the instructional practices as established by Ernst, 2023, Pappu & Sawhney (2019), includes narrowing knowledge divides, predominantly in marginalised and resource-lacking contexts. Finland, Canada and South Korea are some of the countries in an international context that are making progress towards positioning libraries in the center of the pedagogical process across the education frameworks (Ylivuori & Ojaranta, 2023; Ontario School Library Association, 2023; Kim, 2024; Son, 2024). These countries present libraries as sustainable development tools, identifying that their influence extends beyond academic outcomes to include social cohesion, community empowerment, and future-oriented skills. Williams-Cockfield & Mehra, 2023). On the contrary, in Africa, while countries such as Kenya and Namibia are gaining ground with policies that are deliberate on library access, the stark inequalities persist between urban and rural (Ireri, & Ocholla, 2025; Yim, Fellows & Coward, 2020; Lizazi-Mbanga & Mapulanga, 2021). As such, the library landscape remains uneven as many schools in the marginalised rural contexts are faced with structural and systematic challenges compounded by various socio-economic barriers that hinder effective implementation of library programs. This lack of access undermines the sustainability of education systems by perpetuating cycles of poverty, inequality, and exclusion, particularly in rural regions.

South Africa presents a unique and complex case. Despite the progression on addressing historical inequalities in various actions, growth and feasibility of school libraries continues to be a challenge especially in rural areas across the provinces including the Eastern Cape (Mojapelo. 2018). Statistics from a 2021 and 2024 report from the Department of Basic Education’s Education Facility Management System (EFMS) indicate consecutively that 26% of South African schools have libraries with the Eastern Cape trailing behind at 7% (EFMS, 2021&2025). Additionally, the EFMS (2021) report specified that out of the few schools that have libraries, only 14% had fully stocked and functional libraries. These sources indicate the rugged terrain on access and quality education for all for the marginalised in South Africa, specifically the Eastern Cape Province. The uneven distribution of functional libraries further highlights the unsustainable nature of current educational infrastructure, as it risks entrenching inequities that hinder rural community development and long-term human capital growth (Spaull, 2023).

Therefore, addressing these challenges entrenched in the education domain require more than isolated approaches. It demands multi-sectoral interventions such as Ubuntu principles and Collaborative practices grounded on tenets of a transformative paradigm to build the outlook of the South African schools we want. This study, established, explored and provides a narrative of a library initiative in six rural schools in the Eastern Cape South Africa, examining the mission's modest beginnings and the multifaceted dynamics that shaped the process.

2. Conceptual Framework

The study was grounded on the sustainability and ubuntu-inspired collaboration. The sustainability concept emanates from the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG4), which advocates for quality education. SDG4 in correlation with other goals calls for access to education inclusively and equitably (Boeren, 2019). Quality education as SDG4 advocates, promotes sustainable lifelong learning opportunities for everyone (Elfert, 2023). As literature found, such opportunities create spaces for transformation and interest in continuing professional development in the education sphere (Grotlüschen, Belzer, Ertner et al., 2024). Achieving SDG4 amplifies chances of realising the broader social, economic and environmental outcomes leading to social justice in leadership and instructional practices in the society (Grotlüschen, Belzer, Ertner et al., 2024. The implications of enforcing environments where policies implicitly embed the implementation quality education as Marubini Christinah Sadiki (2024) concludes, promotes sustainable human rights triumph.

The ubuntu- inspired collaboration aligns with the transformative paradigm in which the study is grounded. Ubuntu is an African value founded on the principle of “I am because we are.” The value of ubuntu derives from the perspective of interconnectedness, co-existence and moral responsibility towards others (Ngubane & Makua, 2021). The concept itself promotes empathy, compassion and mutual respect amongst people in order to achieve desired goals (Vandeyar & Mohale, 2022). The ubuntu-inspired collaboration is, therefore, based on ethics of empathetic, collective and moral agency, advocating for a shared responsibility and as such augment sustainable and innovative educational goals (Ngubane and Makua, 2021; Vandeyar & Mohale, 2022; Padayachee, Maistry, Harris & Lortan, 2023). The shared responsibility within the ubuntu-inspired collaboration blurs the lines between the participant and the researcher roles and thereby enabling shared responsibilities, mutual ownership and shared agency (Ruppar, Bal, Gonzalez, Love & McCabe, 2018). The significance on intertwining Ubuntu, Collaboration and Transformative paradigm lies in the synergy they offer, such as, promoting social cohesion, breaking silos and bringing an agenda for change to disassemble systematic barriers (Padayachee, Maistry, Harris & Lortan, 2023; Ngubane & Makua, 2021). Anchored in sustainability, Ubuntu-inspired collaboration promotes shared stewardship of educational resources, enabling school libraries to serve not only as spaces of learning but also as drivers of socially and economically sustainable rural development (Vandeyar & Mohale 2022; Padayachee, Maistry, Harris & Lortan, 2023).

3. Materials & Methods

This section details the methodology and design adopted in this study.

3.1. Research Paradigm

The study adopted the transformative paradigm. The transformative paradigm establishes research as a critical component in alleviating issues of inequalities, marginalisation and injustices in society (Ulz, 2023). This is a paradigm, as Jewiss, (2018) further posits, that advocates for change and promotes partnering between researchers and participants, with participants playing a pivotal role, to enhance transformation and bring social change. The study was based on this paradigm as its objective was to establish school libraries in a rural education district through partnership that was aimed at bringing transformation to the marginalised rural schools. Researchers and librarians from a South African university partnered with a rural district in one of the nine provinces in the country. The partnership was with the education district and the six schools (School Management Team and Educators) in which the school libraries were established from scratch. The material used to establish the school libraries was sourced from donations by the university estates, from a book drive, books from South African National Library, Biblionef, Avbob Road to Literacy and books and posters provided by the Education District with infrastructure and other material such as surplus books provided by the schools.

3.2. Research Approach and Design

The study employed the collaborative research approach using both participatory and qualitative methods. Collaborative research approach encompasses a research practice that shadows the lines between researchers and those who conduct research through partnerships with stakeholders to unravel educational challenges (Ruppar et.al., 2018). In this study, the participatory and qualitative methods were used to engage the education stakeholders to work alongside academics from the university transversely all stages of the research process to gather in-depth descriptions in their natural settings (Duea, 2022; Creswell & Creswell, 2020).

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

The paper used photo voices and semi structured interviews. A narrative storytelling to interpret the voices from the photos was used. Photo voice, a data instrument used mostly in PAR studies, was instrumental in enabling a visual of establishment of the libraries as the team experienced it (VanderMolen, Jourdan, & Vervaeke, 2025). A narrative story telling was employed as a voice to narrate the story told by the photovoice providing a sense and a rich tale of how the process of the school library establishment unfolded (McLeod, 2024). Additionally, semi structured interviews with twelve teachers, two from each school were conducted. The semi structured interviews allowed for deeper insights into the influence of the established libraries on teaching and learning.

Data was analysed through thematic analysis. Thematic analysis provided a platform to code the data as well as identify and interpret themes to create meaning from the findings (Flick, 2022). Two broad themes with subthemes were identified as presented in the results section.

3.4. Sampling

The study purposively selected a sample of six schools, three primary and three secondary schools from one rural education district in the Eastern Cape South Africa (Cresswell &Cresswell, 2020). The six schools were part of the library establishment. Twelve teachers were also purposively selected for the semi structured interviews. The teachers sampled were teaching the subjects considered as critical subjects in South Africa (SA), which are Mathematics and Science subjects due to challenges in performance (Kusuma and Susantini, 2022; Kusuma et al., 2020), taught across Foundation (Grade R-3), Intermediate (Grade 4-6) and Senior and Further Education Training (Grade 7-17) phases. The teaching experience of the participants ranged from two to thirty-one years. Pseudonyms were used for the schools, School A – School E, and the participants were named P1-p12 to protect the identity. The languages, which are also regarded as critical subjects in SA, were however excluded from this study.

4. Results

The results were presented in two forms. The first theme, ‘Modest beginnings to sustainable impact-Collective aspirations, passion driven efforts and collaborative unity foster the development and establishment of school libraries’, was based on the photo voices, presented using a narrative storytelling to narrate the experiences through the journey of the school library establishment initiative. The second theme was phrased as Pedagogical effects of school libraries with sub-themes, a) improved lesson preparation, (b) increased learner engagement, (c) promotion of learner-centered environments, (d) curriculum differentiation, and (e) mitigating resource scarcity in rural schools were derived from the semi structured interviews that were conducted with the twelve school educators.

4.1. Modest Beginnings to Sustainable Impact-Collective Aspirations, Passion Driven Efforts and Collaborative Unity Foster the Development and Establishment of School Libraries

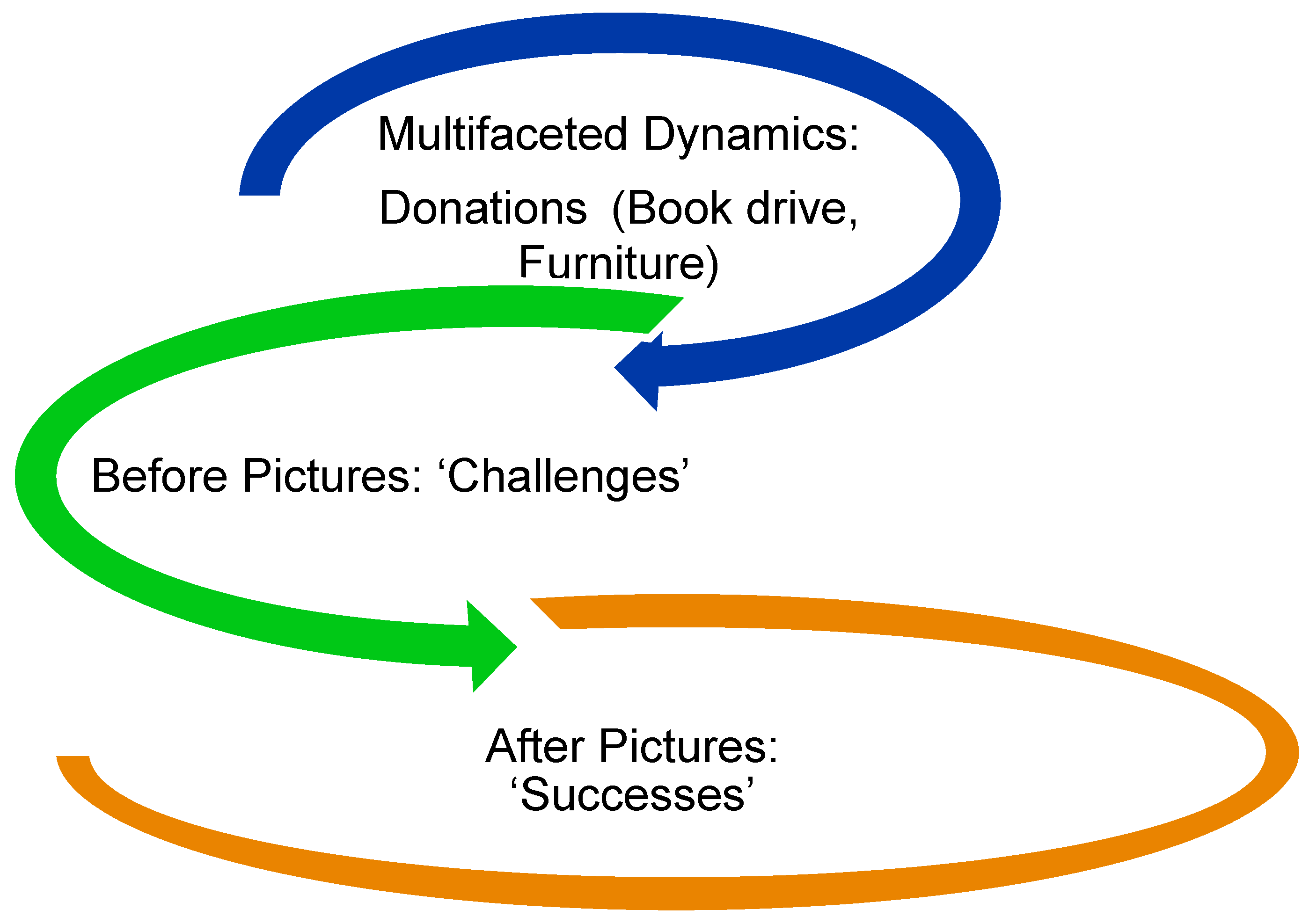

The figure below presents a summary of sub themes from which the narration of the photo-voices emanated.

The sub-themes presented in

Figure 1 present the multifaceted dynamics that shaped sourcing of material for the school library establishment such as the various donations for books, furniture and other materials as well as the photo voices indicating the experiences before the establishment together with after the establishment. The section below details each of the sub-themes.

The collaboration started with finding ways of obtaining material that would make it possible to start a school library. Donations through a book drive were requested and donations for books and furniture were received from the university community from which the academics were coming from, the education district community, the SA National Library, Biblionef and Avbob Road to Literacy.

Figure 2 below shows the poster of the book drive, the collaborating team sorting the books for allocation, the Avbob Road to Literacy and the furniture that was received to start the establishment of the school libraries.

After the book donations and furniture were received, the team divided the material for allocation to each school. The sorting of the material was not an easy job as the donations of books was huge and had to be sorted for fair distribution to all schools. The schools collected the material on the days specified for collection in preparation for the visit to each school for the establishment.

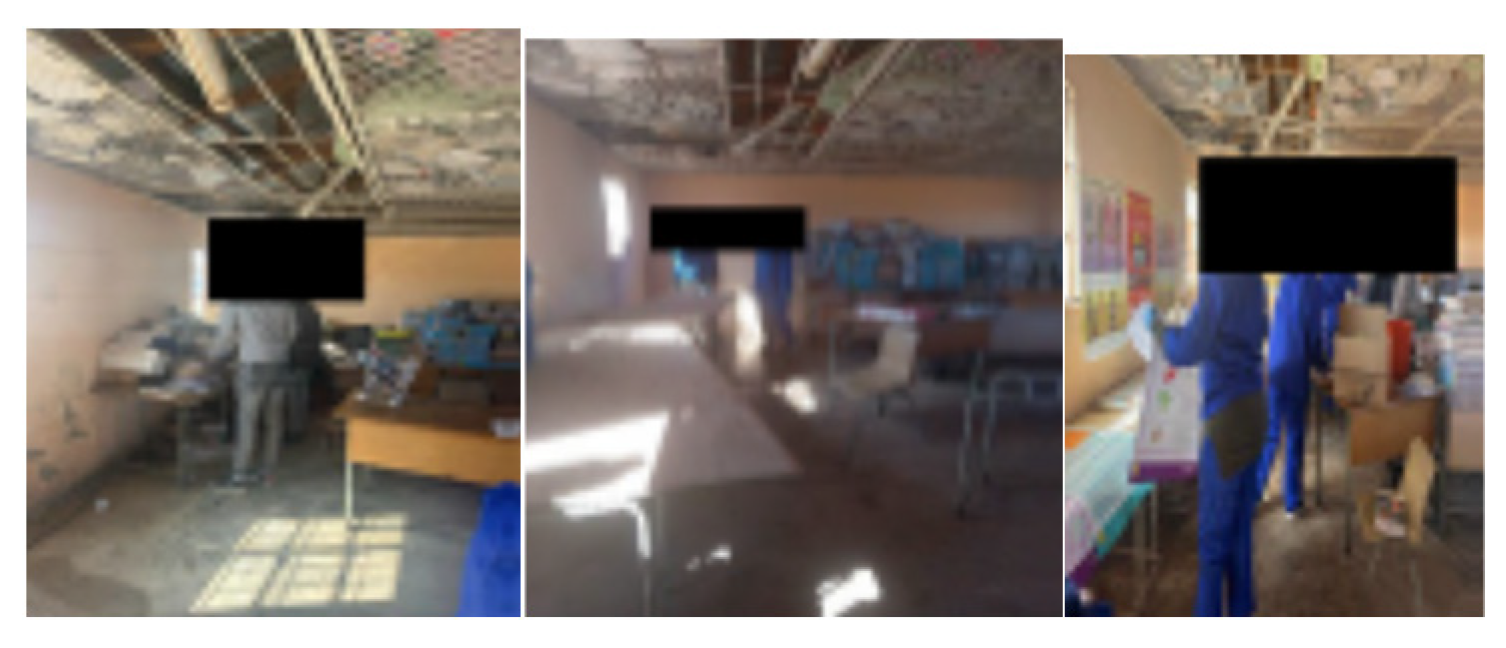

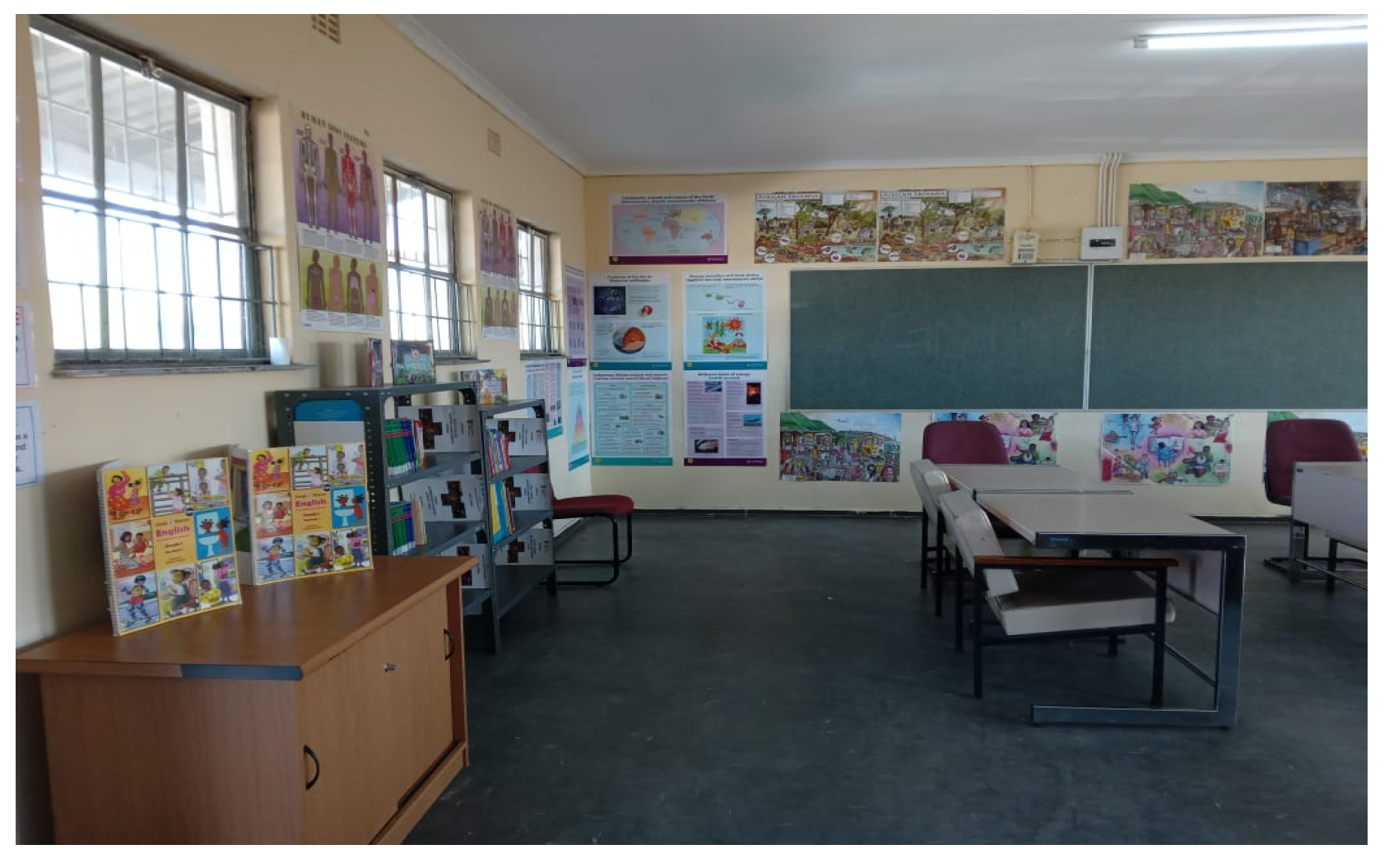

Before Pictures: Challenges

Figure 3 below presents photo voices that illustrate the experiences of the status of the classroom space provided by each school as infrastructure designated for the library establishment.

Figure 4.

School B-Secondary.

Figure 4.

School B-Secondary.

Figure 5.

School C-Secondary.

Figure 5.

School C-Secondary.

Figure 6.

School D-Primary.

Figure 6.

School D-Primary.

Figure 7.

School E-Primary.

Figure 7.

School E-Primary.

Figure 8.

School F-Primary.

Figure 8.

School F-Primary.

The experiences during the initial visits to the schools for the establishment of the libraries varied from each school. In the secondary schools, School A, a school far away from town and deep in the rural outskirts with a gravel road that was not in a good condition, there were emotions of disappointment and distress. The school provided an infrastructure space in an abandoned classroom the school used as a storage space to keep books that were a surplus or no longer used by the educators. The clutter inside the classroom was beyond imagination as the books were scattered everywhere, damaged, with some books put inside the ceiling with clutter such as pipes. The team had to clear the space first, clean it and thereafter establish the library. In School B, the same feeling of disappointment and distress was experienced. The space provided was a classroom space that was also used as a storage space with a lot of various material ranging from books to various unused equipment. The team cleaned out the classroom and used some of the material stored in the classroom for the establishment of the library. The experience by the team in School C was somehow different as the classroom space the school offered was cleaned and needed to be arranged to fit a library environment. However, the books were still in boxes awaiting the arrival of the team to sort out.

In the primary schools, School D and E gave access to the team in classroom spaces designated for the library establishment that were encouraging. School D had a clean classroom space that has long been set aside for a library though it was not established yet until the team arrived to assist with the establishment. School E already had a running library, however, with limited resources, and a teacher librarian employed by the School Governing Body (SGB) to monitor the library activities. However, School F brought back the grief the team experienced in school A. The classroom assigned for the establishment had walls and floor that were not conducive at all to a learning environment. The team had to scrub it first and find ways of assembling it to a conducive library environment.

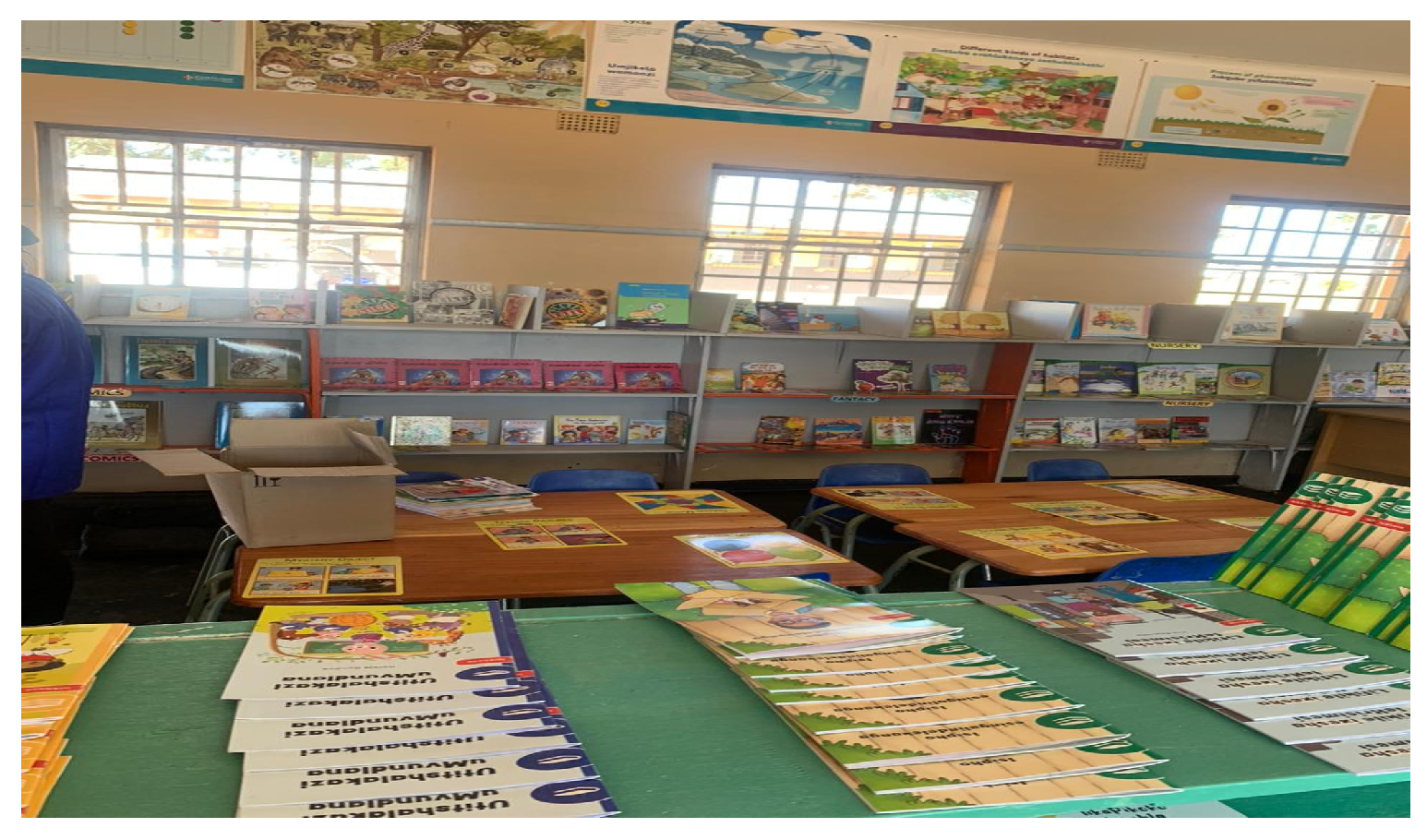

After pictures: Successes

The photo voices in

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 above indicated the successes after the school libraries were established in the schools. The photos reiterate experiences the team acknowledged after the establishment of the school libraries and the portrayed emotions of resilience and triumph. Narration of the tales express the remarkable journey, change and achievement. that emerged after the establishment of the libraries. The photos do not capture only the physical transformation of the library structures but also the profound essence of collaboration and determination to succeed. The visual narratives portray moments of joy, ownership, reclaimed agency that came to life through collaborative and collective accomplishment. The expressions of gratitude shared by the school stakeholders including learners, expressed people who discovered their voices, appreciating the collective effort that created unbelievable wonders from humble beginnings.

Figure 13.

School E-Secondary.

Figure 13.

School E-Secondary.

Figure 14.

School F-Secondary.

Figure 14.

School F-Secondary.

4.2. Pedagogical Effects of School Libraries

Data was further gathered through interviews with two (2) teachers from each school out of the six (6) schools that were involved in the project. The total number of interviewed teachers was twelve (12). The study sought to explore how teachers experienced the use of the libraries in their teaching and learning activities. The data gathered is presented in five (5) sub-themes, namely: (i) improved lesson preparation, (ii) increased learner engagement, (iii) promotion of learner-centered environments, (iv) curriculum differentiation, and (v) mitigating resource scarcity in rural schools.

4.2.1. Improved Lesson Preparation

The data revealed the role of school libraries as additional pedagogical hubs that augmented their lesson presentations and the providing a ladder to content knowledge grasp.

P3 shared that:

“On my side libraries contribute a lot. It makes my teaching easier than going around to find information. Compared to previous years when we did not have a library, it has helped a lot, as we go to the library as teachers to gain more knowledge on what we teach. We no longer use the old teaching styles, as we also use e-learning now. The collaboration with other teachers due to library access has enabled us to connect and it is easy to get information.”

P4 supplemented:

“We need to be equipped with resources as teachers. We need different books to prepare for a lesson, and the library, therefore, helps us in that way, though it still needs more resources for Mathematics and other subjects.”

According to P5:

“First of all, we do not have enough textbooks. So, the visuals that are available in the library help us to show the learners, for example, some of the geometric figures they do not know and cannot see. So, it provides support with visuals where our learners can see what you are talking about, instead of drawing on the chalkboard. When I sit there and plan to prepare a lesson, I see that I can use this part for the introductory part of a lesson. As learners are different . . . now we have visuals, but we still need audio-visual support as well.”

P7 also remarked that:

“The library gives more information, especially in these subjects that are not easy to understand, like mathematics and the sciences.”

In the above extracts, all the participants quoted specified how the newly established school libraries provided them with accessibility to a variety of visual materials, extra resources, and additional textbooks that enhanced their lesson preparation as well as presentations. The data mirrored the dynamic role of the school libraries on classroom

4.2.2. Increased Learner Engagement

The data depicted how the school libraries played a role in motivating learner engagement in class. The learner engagement increased as the findings indicated due to learners being able to visit the school libraries and consolidating their knowledge gained during classroom practice.

P1 praised the innovative library hub:

“We are fortunate as a school as many schools have no libraries. It creates a lot of impact for learners because they are always in the library. The posters make it easier for them to understand than using their books. The environment of the library is very unique and clean. So, the learning environment becomes fruitful. I would say, it changes the learning environment, especially for learners who are doing grade 12; they are very happy.”

P9 accentuated the triumphs of the learning hubs on learner engagement:

“The library use for learner engagement is very successful. You, as the university, delivered a lot of resources that are useful. We go with the learners to the library to show them what we are talking about when teaching. We start by presenting a lesson in class and then go and engage learners in the library. Before we had the library, learners were unable to be engaged in what is presented in class, and now the library is here and there is someone who assists them there, with visuals and they get so happy.”

Similarly, P10 parroted the same opinions, commenting that:

“Learners go to the library and do research, improving their reading and writing. They have a variety of resources, and they learn by doing instead of listening. Now that we have a library, it has become interesting to teach Mathematics.”

These excerpts from the teachers who are the spade workers in the ground revealed a sense of appreciation of how the school library resource sustained teaching and learning. From accessibility to knowledge to independently engaging with knowledge gained from the school library resource, the data indicated the perquisites school libraries brought to the classroom. School libraries, therefore, support the important drive for innovative pedagogy that is in sync with the rapidly changing 21st century ensuring effective teaching and learner agency.

4.2.3. Promoting Learner-Centered Environments

The findings further revealed how the school libraries supported learner-centered environments. The participants reported that the learner’s inquisitiveness and self-directed learning to finding additional information on what was learned in class increased. As such, the engagement promoted critical thinking skills.

P12 justified that:

“Having a library in the school helps learners with the resources that are available to label, for example, body systems. It helps in the classroom as I and the learners are part of using the library resources. Learners have gotten used to using books. It forms part of the teaching and learning process as there are visuals that assist in demonstrating to learners what you mean. Our library is new, but I can already see that there is going to be an improvement in teaching and learning as learners can go to the library without my presence which is not there in many schools. We need more charts though.”

P2 expanded:

“The school library is a very powerful tool in teaching and learning, as our learners need to collect more information beyond the classroom. So, one of the ways, as this is a village without access to the internet, the library provides them with such information. It stimulates learner thinking as they have access to different materials such as textbooks, which improves their understanding of the concepts. Sometimes in class, we have challenges of time constraints, and the library empowers them with a deeper understanding of concepts. As teachers, especially in Maths and Sciences, we bring different methods to solve problems in these critical subjects, but with the assistance of the library, the learners can find more easier methods to solve the problems that we may have not discussed in class.”

P4 elaborated as follows:

“In teaching, we talk a lot, but when problem-solving is needed, you must explain. When you are talking about these things theoretically, the library most of the time shows them concrete material and they start thinking deeply which makes them inquisitive, especially planets and earth, but they need to see them. . ., the library provides that which makes it easy to understand.”

P8 echoed similar sentiments:

“Kids are by nature curious, they always ask questions, how, when, what, how did it come to this, and why are we saying the buildings outside are standing still because of the air pressure that is less outside than inside? The libraries create enthusiasm for them to learn more about any content you have delivered as a teacher. It stimulates their thinking skills. The library wins them to know more independently as an individual and think beyond while they are in primary, and in that way, it creates a springboard for them when they progress to higher classes. Take the ear section, for example, who knows if any of the kids will want to be ear doctors in the future? Extra resources such as the library assist in taking learners further in critical thinking and thinking beyond.”

The data from the extracts above established how the school libraries created a rapport with the learners in the absence of a teacher. The newly established libraries set a space for learners to continuously learn outside of the classroom. The school libraries as an additional resource formed a ladder towards learner’s development through curiosity and intrigue.

4.2.4. Curriculum Differentiation

The data revealed that the newly established school libraries enhanced curriculum differentiation. As the data specified, the school library The library granted learners an opportunity to integrate knowledge across subjects leading to cross-cutting concepts across subject disciplines.

P2 shared that:

“We can do curriculum differentiation. Some learners learn better from the charts and others by reading different textbooks available in the library. Availability of different books and different charts enable us to integrate Mathematics with other subjects”

P6 stated that:

“Libraries assist in . . .. what do we call this thing, I just forgot the word we normally use..., subject integration. In Maths, we have a chapter that teaches about time zones, and that time zone, for you to be able to teach mathematically to them, you must go a little bit into Geography on the movement of the earth, how it rotates, lines of longitude and the differentiation of hours. Having a library helps integrate the knowledge of these two subjects and gives a more meaningful understanding to the learners.”

The citations brought forth how school libraries enhanced crosspollination of knowledge across subjects. The availability of such growth and understanding of the integration between concepts in the various subjects promoted meaningful learning according to each learner’s preferred learning style.

4.2.5. Mitigating Resource Scarcity in Rural Schools

The data indicated the disparity of lack of resources in rural schools. The data therefore revealed that school libraries supplemented the lack thereof. The teachers pointed out that the multi coloured charts enhanced learner’s visual learning styles and expanded the knowledge provided in the traditional textbooks.

P2 recounted that:

“First of all, we do not have enough textbooks, for example in Mathematics. The visuals that are provided in the library are very useful in showing the learners some of the geometric figures. For example, which we cannot show them in class.”

P4 also shared that:

“The library has textbooks; there are books they can read for enjoyment, dictionaries for further understanding, and there are resources available in the libraries that are not available in the classroom. Learners can use the library in their leisure time, maybe in the afternoon. It is flexible enough to be used according to the learner’s individual needs.”

P9 supplemented:

“It helps us sequence our teaching. For example, there is Analytical geometry, etc. The description given by the teacher in the lesson is not enough; learners need to identify with the beautiful colorful charts, not the black and white illustrations found in the textbooks. So, the library helps a lot in supplementing the teaching-learning resources available to the teacher. Some of us are not artistic you know.”

The data presented accentuated the essential function the school libraries portrayed in addressing resource gaps in teaching and learning. This underlines the implications of school libraries as adaptable means that extend outside of what the classroom world could provide. The school libraries, therefore, as the data indicated, not only assisted with sequencing lessons but also in mitigating the challenges experienced by teachers, such as a deficiency in artistic skills.

5. Discussion

The findings from the data indicated the multifaceted dynamics that emerged during the pre- and post-establishment phases of the school libraries through collaborative efforts between various stakeholders on a quest for sustainable teaching and learning. The book drive, the furniture donations, the sorting of material and the process of the establishment of the school libraries echoed what various scholars attest to that Africa and specifically in South Africa, rural ecosystems are marginalized, and as such, sustainability of education systems is undermined (Ireri, & Ocholla, 2025; Yim, Fellows & Coward, 2020; Lizazi-Mbanga & Mapulanga, 2021). The uneven distribution of resources concurs with the statistics established by Mojapelo (2018) and EFMS (2021&2025) on the rugged terrain teaching and learning is traverses on and hindering the rural community development and long-term human capital growth (Spaull, 2023). However, the successes established within the challenges experienced corresponded what literature claims on the power of collaboration in breaking silos and disassembling the systematic barriers, which leads to change (Padayachee, Maistry, Harris & Lortan, 2023; Ngubane & Makua, 2021).

The findings also established a shift from the conventional way libraries are known for towards an ideology that position them as innovative teaching resources that improve pedagogical practices. As accentuated by Merga (2021), the connection between the SDG goal of quality education and school libraries creates a shift from libraries being just repositories of information to reformed educational spaces at the (Seasholes, Kimery & Kaaland, 2023). As such, the data ratified the reformed idea towards school libraries as catalysts that bring accessible, equitable and sustainable integration of economic, social and environmental consciousness (Igbinovia, 2022).

The experiences shared by the participants mirrored the support the school libraries provided to the learners. The school libraries were found to increase learner engagement and promoted learner-centered environments. Merga (2020) attests to what the data revealed by specifying how school libraries encompass inclusivity when integrated into teaching and learning and builds learner well-being in the process. Such integration, as the findings harmonised, is agreeable to Wine, Pribesh, Kimmel, Dickinson & Church (2023), who found that even with the critical subjects that fall under STEAM education, the reading culture enhanced by school libraries advances critical thinking and therefore augments better and improved performance in these subjects. As the data concurred, when learners engage independently with the school library, the integration in turn yields effective outcomes on learner achievement and autonomy (Anggraeni, & Riady, 2024; Schultz-Jones, Farabough & Hoyt, 2021; Mahwasane, 2022).

In the instructional ecosystem, school libraries were found to support teachers with improved lesson preparation and curriculum differentiation. This support, as the data revealed, offered the teachers a space to build on their pedagogical expertise while sharpening learner engagement during and after class sessions. Lewis (2021) emphasises what the data established by emphasising the significance of school libraries on pedagogical practices by providing professional growth and development. As such, Otero (2024) highlighted how the school improvement plans communicate a language that progresses beyond the field of pedagogy by tapping into leadership and management growth and development. The integration of school libraries, thereof, into the instructional framework narrows the gap between traditional and innovative pedagogical practices.

Lastly, the data depicted the grim picture of under resourcing in rural schools. Various scholars confirm that in the African continent, resource disparities are the norm with rural education spheres remain marginalised as compared to their urban counterparts (Mojapelo, 2018; EFMS, 2021&2024; Ireri, & Ocholla, 2025; Yim, Fellows & Coward, 2020; Lizazi-Mbanga & Mapulanga, 202). The influence, therefore, of school libraries on mitigating resource scarcity in rural schools was established in the results. Ernst, 2023, Pappu & Sawhney (2019), correspond the findings on the effectiveness of integrating libraries with the instructional practices. The scholars elaborate how such inclusion narrows knowledge divides, primarily in marginalised and resource-lacking ecosystems (Ernst, 2023, Pappu & Sawhney, 2019). Furthermore, SDG 4, which advocates for quality education, is advanced when resources such as school libraries are accessible to the teaching and learning environment to promote inclusivity and equity for all (Shafira, Ramadhani & Rachman, 2024; Syafitri, Sutiawati, & Rachman, 2024). As stated in the conceptual framework, the alignment of Ubuntu, Collaboration and Transformative paradigm brought forth the synergy of promoting social cohesion, breaking silos and bringing an agenda for change that disassembled the systematic barriers of under resourcing in marginalised contexts such as the rural schools in the Eastern Cape Province (Padayachee, Maistry, Harris & Lortan, 2023; Ngubane & Makua, 2021). Anchored in sustainability, Ubuntu-inspired collaboration promoted shared stewardship of educational resources, enabling school libraries to serve not only as spaces of learning but also as drivers of socially and economically sustainable rural development (Vandeyar & Mohale 2022; Padayachee, Maistry, Harris & Lortan, 2023).

In conclusion, as the study aimed at exploring sustainable pathways for teaching and learning through school libraries in the rural Eastern Cape province, the data established the influence such resources have on the instructional practices. The study, therefore, concludes that the collaborative, transformative and Ubuntu driven efforts positioned school libraries to emerge as sustainable resources that are not just passive depots but enablers that support instruction as well as teacher and learner autonomy especially in rural education settings. Therefore, a shared vision, commitment, and collaboration can overcome obstacles, emphasizing the importance of multi-sectoral approaches to address educational challenges. The study recommends that multi-sectoral approaches should be considered as they can harness diverse expertise and resources to address complex challenges in education. Furthermore, investing in school library access should be prioritized to assist the education sector in attaining SD4 which advocates accessibility for all to quality education.

Author Contributions

Each author contributed equally to the development of the study and were all part of the bigger project and data collection processes. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by the National Research Fund (NRF, and the contribution the fund provided is acknowledged.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Conflicts of Interest and other Ethics Statements

There authors declare no conflict of interest, and all ethical processes were followed.

References

- A Guide to the Selection and Deselection of School Library Resources. Ontario School Library Association A Division of the Ontario Library Association (2023). https://accessola.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/FINAL-2023-09-OSLA-A-Guide-to-the-Selection-and-Deselection-of-School-Library-Resources_EN.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Ali, H., Solfema, S., and Putri, L. D. (2025). Pemberdayaan Pendidikan Berkelanjutan untuk Meningkatkan Kemandirian Pembelajaran dengan Literasi Digital di Desa. Dinamika Pembelajaran: Jurnal Pendidikan dan bahasa, 2(1), 121-128. [CrossRef]

- Anggraeni, N. L. P., and Riady, Y. (2024). The role of the school library in supporting the teaching and learning process and student literacy at SDN Sawojajar 1. Journal of Language and Education Development (LA DU), 6(1), 111–122. [CrossRef]

- Boeren, E. (2019). Understanding Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 on “quality education” from micro, meso and macro perspectives. Int Rev Educ 65, 277–294. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2020). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (5th ed.). SAGE.

- Duea, S. R., Zimmerman, E. B., Vaughn, L. M., Dias, S. and Harris, J. (2022). A guide to selecting participatory research methods based on project and partnership goals. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 3(1), 10-35844.

- Elfert, M. (2023). Lifelong learning in Sustainable Development Goal 4: What does it mean for UNESCO’s rights-based approach to adult learning and education? Int Rev Educ 65, 537–556 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Ernst, M. I. (2023). The Crucial Role of School Libraries in Influencing Children’s Literacy and Learning. Journal of Childhood Literacy and Societal Issues, 2(1), 32-39.

- Flick, U. (2022). The Sage handbook of qualitative research design. Sage Publications.

- Grotlüschen, A., Belzer, A., Ertner, M. and Yasukawa, K. (2024). The role of adult learning and education in the Sustainable Development Goals. Int Rev Educ 70, 205–221. [CrossRef]

- Igbinovia, M. O. (2022). Public libraries as enablers of sustainable development. In Handbook of Research on Emerging Trends and Technologies in Librarianship (pp. 341-351). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Ireri, J. and Ocholla, D. (2025). Status of information literacy skills offered by secondary school libraries to students in urban and rural environments in Kenya. South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science, 91(1), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Jewiss, J. (2018). Transformative paradigm. In The SAGE encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation (Vol. 4, pp. 1711-1711). SAGE Publications, Inc., . [CrossRef]

- Kim H. (2024). Education for sustainable library infrastructure in the digital age: Analysis of library and information science curricula in South Korea. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development. 8(14): 9233. [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, A. E. and Susantini, E. (2022). The effect of rode learning model on enhancing students’ communication skills. Stud. Learn. Teach. 3, 132–140. doi: 10.46627/silet. v3i3.170.

- Kusuma, A. E., Wasis, S. E., Susantini, E. and Rusmansyah, N. (2020). Physics innovative learning: RODE learning model to train student communication skills. J. Phys. 1422:12016. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1422/1/012016.

- Lizazi-Mbanga, B. and Mapulanga, P. (2021). Factors that influence attitudes to and perceptions of public libraries in Namibia: user experiences and non-user attitudes. South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science, 87(2), 30-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.7553/87-2-1968.

- Mahwasane, N. (2022). Prevailing status of school libraries in South Africa: challenges and suggestions. J. Sociol. Soc. Anthropol. 13, 87–97. [CrossRef]

- Merga, K.M. (2021). Libraries as Wellbeing Supportive Spaces in Contemporary Schools, Journal of Library Administration, 61:6, 659-675. [CrossRef]

- Marubini C. S. (2024). Promoting Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education Through Human Rights to Achieve Sustainable Development Goal 4. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 30(11), 654–662. [CrossRef]

- McKay, V. (2018). Literacy, lifelong learning and sustainable development. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 58(3), 390-425.

- McLeod, S. (2024). Narrative Analysis in Qualitative Research. 10.13140/RG.2.2.30491.07200. [CrossRef]

- Mojapelo, S. M. (2018). Challenges in establishing and maintaining functional school libraries: Lessons from Limpopo Province, South Africa. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 50(4), 410-426. [CrossRef]

- Ngubane, N. I. and Makua, M. (2021). Intersection of Ubuntu pedagogy and social justice: Transforming South African higher education. Transformation in Higher Education, 6, 113. [CrossRef]

- Otero, M. T. (2024). The role of the school library in education: An essential learning resource in schools. Education and Information Technologies, 29(4), 5123–5142. [CrossRef]

- Padayachee, K., Maistry, S., Harris, G. T. and Lortan, D. (2023). Integral education and Ubuntu: A participatory action research project in South Africa. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 13(1), 1298. [CrossRef]

- Pappu, R. and Sawhney, S. (2019). Building effective school libraries: Lessons from the study of a Library Program in India. International Information & Library Review, 51(3), 217-230.

- Ruppar, A. L., Bal, A., Gonzalez, T., Love, L. and McCabe, K. (2018). Collaborative Research: A New Paradigm for Systemic Change in Inclusive Education for Students with Disabilities. International Journal of Special Education, 33(3), 778-795.

- Santos, A. I. and Serpa, S. (2020). Literacy: Promoting sustainability in a digital society. J. Educ. Teach. Soc. Stud, 2(1), p1. [CrossRef]

- Schultz-Jones, B., Farabough, M. and Hoyt, R. (2021). “Towards consensus on the school library learning environment: a systematic search and review,” in IASL Annual Conference Proceedings. doi:10.29173/iasl7471.

- Seasholes, C., Kimery, L. and Kaaland, C. (2023). School library research: Guest editors’ introduction. Peabody Journal of Education, 98(1), 83-84.

- Shafira, V. S., Ramadhani, G. and Rachman, I. F. (2024). How digital literacy can drive inclusive progress towards the 2030 SDGs. Advances in Economics & Financial Studies, 2(2), 102-112.

- Son, S. (2024). Libraries’ roles in media and information literacy education: Obtaining the opinions of South Korean volunteer librarians through the Delphi method. IFLA journal, 50(3), 525-546. [CrossRef]

- Syafitri, D. A., Sutiawati, S. and Rachman, I. F. (2024). Menghadapi tantangan digital: Peran literasi digital dalam mewujudkan tujuan pembangunan berkelanjutan. WISSEN: Jurnal Ilmu Sosial Dan Humaniora, 2(2), 145-156.

- Ulz, J. (2023). What is a research paradigm? Types of research paradigms with examples. Researcher. Life.

- VanderMolen, J., Jourdan, K. and Vervaeke, M. (2025). Using Photovoice to Address Qualitative Research Methodology Competencies of Public Health Students: A Pilot Study. Pedagogy in Health Promotion, 23733799251347249. [CrossRef]

- Williams-Cockfield, K. C. and Mehra, B. (Eds.). (2023). How public libraries build sustainable communities in the 21st century. Emerald Publishing Limited. [CrossRef]

- Wine, L. D., Pribesh, S., Kimmel, S. C., Dickinson, G., & Church, A. P. (2023). Impact of school librarians on elementary student achievement in reading and mathematics: A propensity score analysis. Library & Information Science Research, 45(3), 101252. [CrossRef]

- Yim, M., Fellows, M. and Coward, C. (2020). Mixed-methods library evaluation integrating the patron, library, and external perspectives: The case of Namibia regional libraries. Evaluation and program planning, 79, 101782. [CrossRef]

- Ylivuori, S. and Ojaranta, A. (2023). Librarians’ and teachers’ conceptions of multiliteracies in the context of Finnish curriculum reform.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).