1. Introduction

The Qur’an presents a unique and comprehensive vision of knowledge that transcends empirical boundaries and integrates revelation, reason, and moral purpose into a unified whole. Unlike secular epistemologies that separate fact from value, the Qur’an situates inquiry within divine guidance, where knowledge (ʿilm) becomes both a means of understanding creation and a path to spiritual elevation. Yet, despite the Qur’an’s numerous calls to observe (naẓar), reflect (tafakkur), and verify (burhān), a systematic research methodology derived exclusively from the Qur’an has seldom been articulated. This study seeks to reconstruct that methodology—a Qur’anic research framework—by identifying the stages of knowledge generation embedded in revelation and demonstrating how they form a holistic process that links observation, reflection, validation, wisdom, and action.

1.1. Background of the Study

The pursuit of knowledge (ʿilm) has been one of the most defining features of Islamic civilisation. Unlike any other revealed scripture, the Qur’an begins its revelation with a command directly related to the act of learning—Iqraʾ bi-smi rabbika alladhī khalaq (“Read in the name of your Lord who created,” Qur’an 96:1). This divine imperative establishes a foundational epistemological principle: knowledge is sacred, purposeful, and intimately connected to the Creator. Over the centuries, Muslim scholars, philosophers, and scientists have drawn inspiration from this command to cultivate diverse disciplines—ranging from theology and philosophy to astronomy, medicine, and the natural sciences. Yet, despite this rich intellectual heritage, there has been an increasing disconnection between contemporary Muslim research practices and the Qur’anic paradigm of knowledge generation.

Modern academia, influenced largely by Western epistemological frameworks, defines “research” through empirical verification, inductive reasoning, and hypothesis testing. While these methods have undeniable merits, they often rest on secular assumptions that disconnect knowledge from metaphysical truth and moral accountability. By contrast, the Qur’an introduces a holistic epistemology that harmonises reason, revelation, intuition, and ethics within a unified worldview grounded in Tawḥīd (Divine Unity). This study, therefore, seeks to reconstruct a Qur’anic research methodology by identifying the epistemic processes that the Qur’an itself prescribes—beginning from observation and reflection, progressing through validation and synthesis, and culminating in action.

The Qur’an not only commands the believer to seek knowledge but also delineates the method by which knowledge should be sought. It repeatedly invites human beings to “observe” (unẓurū; Qur’an: 29:20), to “reflect” (yatafakkarūn; Qur’an: 3:191), to “ponder” (yatadabbarūn; Qur’an: 4:82), and to “verify” (hātū burhānakum; Qur’an: 2:111). Each of these verbs indicates a specific intellectual activity that together forms the Qur’anic model of inquiry. In other words, the Qur’an itself contains within its linguistic and semantic structure a divinely guided research methodology that connects empirical observation with spiritual reflection and ethical application.

1.2. Research Problem

Despite the Qur’an’s repeated emphasis on intellectual engagement, a clear and systematic model of Qur’anic research methodology has rarely been articulated in modern scholarship. Islamic epistemology has been extensively discussed in the works of scholars such as Al-Faruqi (1982), Al-Attas (1995), and Chittick (2007), but their focus has largely been on philosophical and metaphysical foundations rather than methodological processes. Consequently, contemporary Muslim academics often adopt Western research paradigms that are epistemically disconnected from the Qur’anic worldview. The absence of a structured Qur’an-based methodology results in a dichotomy between revealed knowledge (ʿilm al-waḥy) and acquired knowledge (ʿilm al-kasbī), causing fragmentation in the Muslim intellectual enterprise.

Moreover, most attempts to Islamize modern sciences have been limited to reinterpreting content rather than redefining the process of knowledge itself. The Qur’an, however, demands that the process—from inquiry to verification—be conducted within the moral and ontological boundaries of divine guidance. Thus, the primary research problem of this study is the lack of an integrated Qur’anic framework that explains how knowledge should be systematically discovered, verified, and applied in light of revelation.

1.3. Research Objectives

This study aims to address the aforementioned gap by deriving a coherent and holistic Qur’anic Research Methodology that reflects the Qur’an’s epistemological structure. The specific objectives are:

To identify and analyse Qur’anic terms that correspond to stages of the research process, such as Naẓar (observation), Tafakkur and Tadabbur (reflection), Burhān (validation), Ḥikmah (synthesis), and ʿAmal (application).

To interpret these terms within their Qur’anic contexts and examine their interconnectedness as components of a divine model of inquiry.

To construct a conceptual model or framework that visualises the Qur’anic research process from empirical perception to applied wisdom.

To compare this Qur’anic methodology with the dominant Western scientific paradigm to highlight its epistemological distinctiveness and ethical orientation.

To propose implications for future Islamic research and education grounded in Qur’anic epistemology.

1.4. Significance of the Study

The significance of this study lies in its attempt to reconstruct knowledge production at its theological roots. In an age dominated by materialistic scientism and epistemic relativism, returning to the Qur’an as the source of epistemological guidance represents both a spiritual necessity and an intellectual revival. The Qur’an does not oppose empirical science; rather, it provides an ontological grounding that gives science meaning, purpose, and ethical restraint. By formulating a research methodology directly from the Qur’an, this study aspires to revitalise the integration of revelation and reason—a hallmark of the classical Islamic Golden Age.

Furthermore, a Qur’anic research methodology offers a paradigm that transcends disciplinary boundaries. It is equally applicable to the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities, as it provides universal principles for observation, reasoning, verification, and moral accountability. Such an approach would enable Muslim researchers to engage critically with modern knowledge systems without losing their metaphysical and ethical moorings. The result would be a transformative synthesis of faith and intellect, aligning human inquiry with divine wisdom (ḥikmah).

1.5. Research Questions

To guide the inquiry, this study seeks to answer the following key questions:

What are the principal epistemological concepts in the Qur’an that imply a systematic process of inquiry and knowledge generation?

How do Qur’anic terms such as Naẓar, Tafakkur, Tadabbur, Burhān, Ḥikmah, and ʿAmal correspond to stages of the modern research process?

In what ways does the Qur’an integrate empirical observation with spiritual reflection and ethical validation?

How can a Qur’an-based model of research contribute to the reconstruction of Islamic epistemology in contemporary academic discourse?

What are the implications of adopting a Qur’anic research methodology for the future of Islamic education, science, and intellectual culture?

1.6. Concluding Note to the Introduction

This introduction establishes the foundation for developing a Qur’an-based methodology that views research not as a secular enterprise but as a form of ʿibādah—a sacred intellectual act that leads humanity from perception to truth, from ʿilm (knowledge) to ḥikmah (wisdom). The following sections will explore the theoretical structure of Qur’anic epistemology and systematically derive the stages of the research process implied in revelation. In doing so, this paper seeks to restore the Qur’an to its rightful position—not only as the ultimate source of knowledge but also as the model for how knowledge itself should be pursued.

2. Theoretical Foundation—Qur’anic Epistemology

The epistemological foundation of the Qur’an presents a unique paradigm of knowledge that integrates revelation, reason, and reflection into a single coherent framework. Unlike Western epistemology, which often separates rational inquiry from divine revelation, the Qur’anic model views both as complementary dimensions of truth-seeking. The Qur’an introduces a rich lexicon of cognitive and spiritual terms—such as ʿilm (knowledge), ʿaql (reason), tafakkur (reflection), tadabbur (deep contemplation), ḥikmah (wisdom), and īmān (faith)—each representing distinct yet interrelated stages in the process of knowing. This theoretical foundation serves as the intellectual core of the Qur’anic research methodology proposed in this study, guiding the transition from observation of the natural and moral world to the synthesis of divine wisdom and human understanding.

2.1. The Qur’anic Concept of Knowledge (ʿIlm)

The Qur’an treats ʿilm (knowledge) as a sacred trust and as the foundation of human distinction. The very first revelation commands: “Read in the name of your Lord who created” (Qur’an 96:1). This establishes that knowledge in Islam is not a neutral activity but one rooted in servitude and consciousness of the Creator. In contrast to secular epistemologies that consider knowledge as a product of human reason alone, the Qur’an attributes knowledge to divine bestowal—“He taught man what he knew not” (Qur’an: 96:5).

In Qur’anic discourse, ʿilm is both ontological and teleological: it reveals the truth (ḥaqq) of existence and guides humanity toward righteous action. Knowledge is not limited to sensory experience; it includes moral, spiritual, and metaphysical dimensions. The Qur’an frequently contrasts those who “know” (yaʿlamūn) with those who “do not know” (lā yaʿlamūn) (Qur’an: 39:9), signifying that true knowledge requires both intellectual comprehension and moral awareness. Thus, Qur’anic epistemology integrates the cognitive, ethical, and spiritual aspects of human understanding.

From an epistemological perspective, ʿilm in the Qur’an is a divinely oriented awareness that emerges from reflection on the āyāt—the signs of God in both revelation and creation. As the Qur’an states: “We will show them Our signs in the horizons and within themselves until it becomes clear to them that this is the truth” (Qur’an: 41:53). Knowledge, therefore, arises from observing the signs (āyāt) and connecting them to divine truth through the intellect (ʿaql).

2.2. The Role of Reason (ʿAql) in Qur’anic Epistemology

The Qur’an repeatedly calls upon humans to “use their intellect” (afalā taʿqilūn; Qur’an: 2:44, 36:62). The term ʿaql (reason or intellect) appears not as a static noun but in dynamic verbal forms—emphasising an active process of reasoning and discernment. The Qur’an does not view reason as an independent authority separate from revelation; rather, it positions ʿaql as the faculty through which revelation is understood, interpreted, and verified.

In the Qur’anic worldview, ʿaql functions as both analytical and moral intelligence. It allows human beings to distinguish truth from falsehood, to derive lessons from historical experience, and to comprehend the moral implications of their actions. The Qur’an praises those who “listen to the word and follow the best of it” (Qur’an: 39:18), implying a rational evaluation process guided by moral discernment.

Moreover, ʿaql serves as the human faculty that connects empirical observation to spiritual realisation. When the Qur’an invites believers to observe nature—the alternation of night and day, the growth of plants, the order of the heavens—it simultaneously calls for rational reflection: “Indeed, in the creation of the heavens and the earth and the alternation of night and day are signs for those who possess intellect (ulū al-albāb)” (Qur’an: 3:190). Here, the intellectual process is inseparable from spiritual humility; reason becomes an instrument of recognising divine wisdom.

2.3. Reflection (Tafakkur) and Contemplation (Tadabbur)

The Qur’an distinguishes between tafakkur (reflective reasoning) and tadabbur (deep contemplation). Both are central components of the Qur’anic research process.

Tafakkur refers to analytical reflection upon phenomena—examining causes, patterns, and relationships. The Qur’an states: “Do they not reflect (yatafakkarūn) upon the creation of the heavens and the earth?” (Qur’an: 30:8). This term captures a cognitive process similar to what modern epistemology describes as observation and hypothesis formation. Yet in the Qur’anic sense, tafakkur is not merely intellectual curiosity; it is a form of worship (ʿibādah al-ʿaql), since it reveals divine order in creation.

Tadabbur, on the other hand, involves deep contemplation on revelation itself. The Qur’an asks rhetorically: “Do they not contemplate (yatadabbarūn) the Qur’an, or are there locks upon their hearts?” (Qur’an: 47:24). While tafakkur is directed toward the cosmic signs (natural and social phenomena), tadabbur focuses on the scriptural signs—the words of revelation. Together they represent the two complementary realms of reflection in the Qur’an: the Book of Nature and the Book of Revelation.

In the Qur’anic epistemic model, both tafakkur and tadabbur are essential stages of the research process. The first leads to empirical observation and causal reasoning; the second leads to metaphysical insight and moral orientation. Thus, reflection in the Qur’an is both scientific and spiritual, combining the intellect’s inquiry with the soul’s devotion.

2.4. Verification and Validation: The Qur’anic Principle of Burhān and Bayyinah

Knowledge in the Qur’an is not speculative but demonstrative. The Qur’an consistently demands evidence (burhān, bayyinah) as the criterion of truth. The challenge “Hātū burhānakum in kuntum ṣādiqīn” (“Bring your proof if you are truthful”) appears repeatedly (Qur’an: 2:111; 21:24; 27:64). This reflects the Qur’an’s insistence on verification, argumentation, and intellectual accountability.

Burhān in classical Arabic signifies a decisive proof derived from rational and empirical evidence, while bayyinah denotes clarity and manifest truth. Together, they constitute the Qur’anic validation mechanism—an epistemic stage where claims are tested and verified through reasoning consistent with divine revelation. This principle aligns with the modern concept of falsification and critical testing, but it transcends it by grounding the verification process in moral and metaphysical certainty.

The Qur’an thus establishes a balance between faith and reason: belief (īmān) must be substantiated by understanding, and understanding must be confirmed by evidence. This dialectical relationship between revelation and verification is a key feature of Qur’anic epistemology, ensuring that knowledge remains both rationally sound and spiritually authentic.

2.5. Wisdom (Ḥikmah): The Integration of Knowledge and Action

Beyond knowledge and reasoning, the Qur’an introduces ḥikmah (wisdom) as the synthesis of intellectual understanding and ethical application. The term ḥikmah appears frequently alongside ʿilm and kitāb, as in “He teaches them the Book and the Wisdom” (Qur’an: 62:2). In Qur’anic ontology, ḥikmah signifies the mature, integrated form of knowledge that manifests as just and purposeful action.

Whereas ʿilm represents understanding of facts, and ʿaql governs rational analysis, ḥikmah transforms both into moral and practical outcomes. The Prophet (peace be upon him) was described as having been given both the Book and the Wisdom (Qur’an: 2:129), illustrating that divine knowledge reaches completion only when it results in ethical insight and righteous conduct. Thus, in the Qur’anic epistemological hierarchy, ḥikmah stands as the culmination of the research process—the stage at which knowledge becomes transformative.

2.6. Faith and Action (Īmān and ʿAmal) as Epistemic Fulfilment

In the Qur’anic framework, the journey of knowledge does not end with cognition but with faith (īmān) and action (ʿamal). Repeatedly, the Qur’an unites these terms—“those who believe and do righteous deeds”—indicating that belief without praxis, or knowledge without transformation, is incomplete.

From an epistemological standpoint, īmān is not blind acceptance but a conviction born of knowledge and reflection. The Qur’an describes three ascending degrees of certainty: ʿilm al-yaqīn (knowledge of certainty), ʿayn al-yaqīn (vision of certainty), and ḥaqq al-yaqīn (truth of certainty) (Qur’an: 102:5–7; 56:95). These stages represent the deepening of epistemic awareness—from knowing a truth conceptually, to perceiving it directly, and finally to embodying it experientially.

In the context of research methodology, īmān and ʿamal complete the process by transforming validated knowledge into lived wisdom. Research in the Qur’anic sense is not complete until it leads to ethical action and societal betterment. Hence, the Qur’an establishes an inseparable link between epistemology and praxis, making knowledge both a moral responsibility and a means of worship.

2.7. Synthesis: Toward a Qur’anic Model of Knowledge

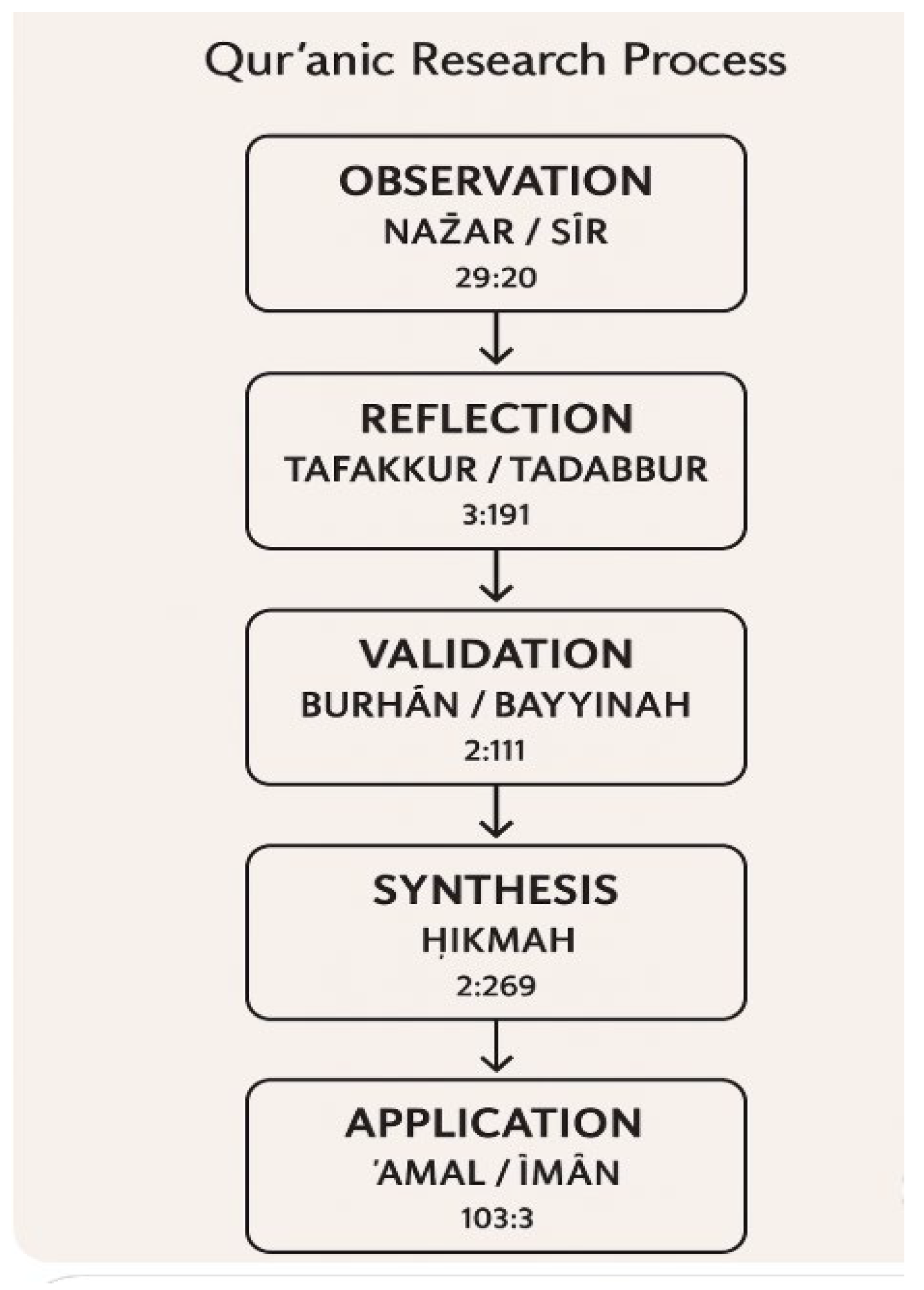

When the Qur’anic epistemological elements are arranged sequentially, they form a coherent process of inquiry:

Table 1.

The Qur’anic epistemological elements.

Table 1.

The Qur’anic epistemological elements.

| Stage |

Arabic Term |

Qur’anic Function |

| 1. Observation |

Naẓar / Sayr

|

Empirical and experiential engagement with the signs of creation (Qur’an: 29:20; 3:137). |

| 2. Reflection |

Tafakkur / Tadabbur |

Analytical and contemplative reasoning upon creation and revelation (Qur’an: 3:191; 47:24). |

| 3. Validation |

Burhān / Bayyinah |

Verification through rational evidence and clarity (Qur’an: 2:111; 21:24). |

| 4. Synthesis |

Ḥikmah |

Integration of knowledge into moral and practical wisdom (Qur’an: 2:269; 62:2). |

| 5. Application |

ʿAmal /Īmān

|

Transformation of knowledge into ethical and spiritual action (Qur’an: 103:3; 49:14). |

This five-stage framework represents the Qur’anic epistemological cycle—where knowledge begins with observation and culminates in transformative action, guided at every step by divine revelation. It reflects a balance between empirical inquiry and metaphysical orientation, between intellectual rigour and moral purpose.

The Qur’anic epistemology thus envisions knowledge as a living process—a journey from perception to certainty, from intellect to faith, from information to wisdom. It unites the domains of science, philosophy, and spirituality under the principle of Tawḥīd, where all truths ultimately converge toward the recognition of the Divine. In this light, the Qur’an is not merely a source of doctrine but the methodological foundation for all genuine research. Understanding and applying this framework allows Muslim scholarship to rediscover the harmony between revelation and reason and to build a future where knowledge serves both truth and humanity.

3. Methodology: Deriving the Qur’anic Research Process

The Qur’an articulates a dynamic and cyclical process of inquiry that constitutes a comprehensive

research methodology—beginning with observation and culminating in the synthesis and application of wisdom (

ḥikmah). Each stage is explicitly supported by Qur’anic concepts and verses that define the epistemic journey from perception to understanding, from contemplation to action. This structure does not merely serve theological ends but provides a universal model of systematic inquiry grounded in divine epistemology.

Figure 1.

Five-step Qur’anic research process.

Figure 1.

Five-step Qur’anic research process.

3.1. Observation (نَظَر / سَيْر)

The first step in Qur’anic research begins with naẓar (نَظَر) — the act of observing, perceiving, and examining signs in both the natural and social world. The Qur’an repeatedly calls upon humankind to see and travel (sīr) through the earth to draw lessons from history and creation:

“Say, ‘Travel through the land and observe how He began creation.’” (Qur’an: 29:20)“Have they not looked at the camels—how they are created?” (Qur’an: 88:17)

This observational command represents the empirical foundation of Qur’anic inquiry. Observation, in the Qur’anic context, extends beyond sensory perception to include moral and historical awareness—urging believers to study phenomena as āyāt (signs) of divine order. The Qur’an thus establishes observation as the starting point of all intellectual and spiritual discovery, emphasising that perception without reflection remains incomplete (Qur’an: 7:185).

3.2. Reflection (تَفَكُّر / تَدَبُّر)

Following observation, the Qur’an demands tafakkur (deep reflection) and tadabbur (contemplation upon outcomes and meanings). These stages move the seeker from empirical data toward intellectual and metaphysical understanding.

“Do they not reflect (يتفكرون) upon the creation of the heavens and the earth?” (Qur’an: 3:191)“Do they not contemplate (يتدبرون) the Qur’an?” (Qur’an: 47:24)

Tafakkur implies reasoning through analogies and causal relations, while tadabbur invites systematic contemplation that penetrates beyond surface appearances to discern underlying truths. The Qur’an positions reflective thought as an act of worship and epistemic responsibility, where intellect (ʿaql) and revelation (waḥy) converge. In this way, reflection becomes the analytical phase of Qur’anic research, where the mind decodes divine patterns from observed realities.

3.3. Validation (بُرْهَان / بَيِّنَة)

Once reflection leads to a hypothesis or understanding, the Qur’an emphasises burhān (clear proof) and bayyinah (evident sign) as the principles of validation.

“Say, ‘Bring your proof (burhānakum) if you are truthful.’” (Qur’an: 2:111)“Indeed, clear proofs (bayyināt) have come to you from your Lord.” (Qur’an: 6:157)

Validation in the Qur’anic sense is both rational and moral—it requires evidence that aligns with divine truth and universal justice. It discourages conjecture (ẓann) and blind imitation, urging scholars to verify claims through intellectual rigour and ethical discernment (Qur’an: 17:36). This epistemic integrity mirrors the modern scientific principle of falsifiability, but in the Qur’an, proof must harmonise with both ʿaql and īmān—reason and faith.

3.4. Synthesis (حِكْمَة)

The culmination of observation, reflection, and validation is ḥikmah—a state of synthesised wisdom. The Qur’an defines ḥikmah as the ability to integrate knowledge into moral and practical insight:

“He gives wisdom (ḥikmah) to whom He wills, and whoever is given wisdom has indeed been given abundant good.” (Qur’an: 2:269)

Synthesis represents the transition from analytical knowledge to comprehensive understanding. It unites empirical insight, rational judgment, and divine guidance into a balanced worldview. In the Qur’anic epistemology, ḥikmah is not merely intellectual achievement—it is the alignment of knowledge with ethical and spiritual purpose. This synthesis ensures that knowledge leads to human and cosmic harmony, fulfilling the Qur’an’s role as a guide (hudā) for those who think (Qur’an: 2:185).

3.5. Application (عَمَل /إِيمَان)

The final stage of the Qur’anic research process is ʿamal (action) and īmān (faith in practice). The Qur’an repeatedly links knowledge and wisdom with righteous deeds:

“Those who believe and do righteous deeds (آمنوا وعملوا الصالحات)” (Qur’an 103:3)“And say, ‘Work, for Allah will see your deeds, and [so will] His Messenger and the believers.’” (Qur’an: 9:105)

Knowledge, when not applied, is rendered inert in the Qur’anic worldview. Application is both the ethical testing of knowledge and its social implementation. The combination of īmān and ʿamal transforms abstract understanding into living reality, producing not just informed individuals but morally responsible communities.

3.6. Integration of the Process

The Qur’anic model of research thus forms an integrated epistemic cycle: Observation → Reflection → Validation → Synthesis → Application. Each stage refines the previous, ensuring that empirical discovery, intellectual reasoning, and moral action are not separate domains but sequential and interdependent aspects of divine inquiry.

This Qur’anic epistemological process demonstrates that true knowledge is not only about knowing what is, but also discerning what ought to be—where every step toward understanding culminates in righteous action and spiritual elevation. Hence, the Qur’an does not merely inform human reason; it transforms it into a moral instrument guided by divine wisdom.

4. Findings: Qur’anic Logic and Process of Discovery

The Qur’an provides a coherent and profound epistemological framework that harmonises revelation, rationality, and empirical inquiry. Its approach to knowledge (ʿilm) is neither dogmatic nor speculative; rather, it seeks to guide humanity through observation, contemplation, and verification within the bounds of divine revelation. The Qur’anic discourse repeatedly emphasises that intellectual inquiry is an act of faith when directed toward understanding the signs (āyāt) of Allah in both the natural world and the self (Qur’an: 41:53). Thus, knowledge is not merely the accumulation of information but a process of spiritual realisation that connects observation with moral and existential truth.

4.1. The Qur’an’s Encouragement of Critical Inquiry and Empirical Observation

The Qur’an consistently calls upon humanity to observe, reflect, and analyse the surrounding universe. It commands:

“Indeed, in the creation of the heavens and the earth and the alternation of the night and day are signs for those of understanding” (Qur’an: 3:190).

Here, the invitation is not passive contemplation but an active engagement of the intellect—employing reason (ʿaql) to extract meaning from the observable cosmos. The repeated interrogative form “Afalā taʿqilūn?” (“Will you not reason?”) occurs more than a dozen times across the Qur’an (e.g., Qur’an: 2:44; Qur’an: 6:32), underscoring that faith without reflection is incomplete. This command integrates a naturalistic epistemology grounded in empirical awareness—one that affirms divine creation through systematic engagement with the environment.

Moreover, verses such as “Do they not look at the camels—how they are created?” (Qur’an: 88:17) show that Qur’anic inquiry extends to zoology, astronomy, and geology, implying a holistic scientific curiosity. Observation (naẓar) thus becomes the first gateway of knowledge, forming a divine imperative for research, discovery, and technological advancement. It rejects blind imitation (taqlīd) and advocates for methodological reasoning that aligns empirical data with spiritual wisdom.

4.2. Balancing Revelation and Reasoning

The Qur’an constructs a delicate equilibrium between revelation (waḥy) and reason (ʿaql). It does not set them in opposition but in mutual reinforcement. Revelation provides the ontological foundation and moral compass, while reason functions as the interpretive mechanism that contextualises divine truth in the material world.

For instance, Allah commands:

“Do not pursue that of which you do not know. Indeed, the hearing, the sight, and the heart—about all those [one] will be questioned” (Qur’an: 17:36).

This verse establishes a principle of epistemic responsibility: belief or claim must be supported by verified evidence. The Qur’an thus becomes the prototype of a rational and ethical epistemology—an equilibrium where reasoning is guided by divine revelation and revelation is rationally understood through inquiry. It is through this synthesis that knowledge becomes transformative, moral, and action-oriented rather than speculative or dogmatic.

The Qur’anic emphasis on tafakkur (reflection) and tadabbur (contemplation) indicates that divine verses are meant to be thought about, not merely recited. Hence, revelation is not an obstacle to human intellect but its necessary illumination. The intellect, in turn, validates and applies revelation in dynamic worldly contexts, showing that Islamic epistemology is inherently dialogical between the unseen (ghayb) and the seen (shahāda).

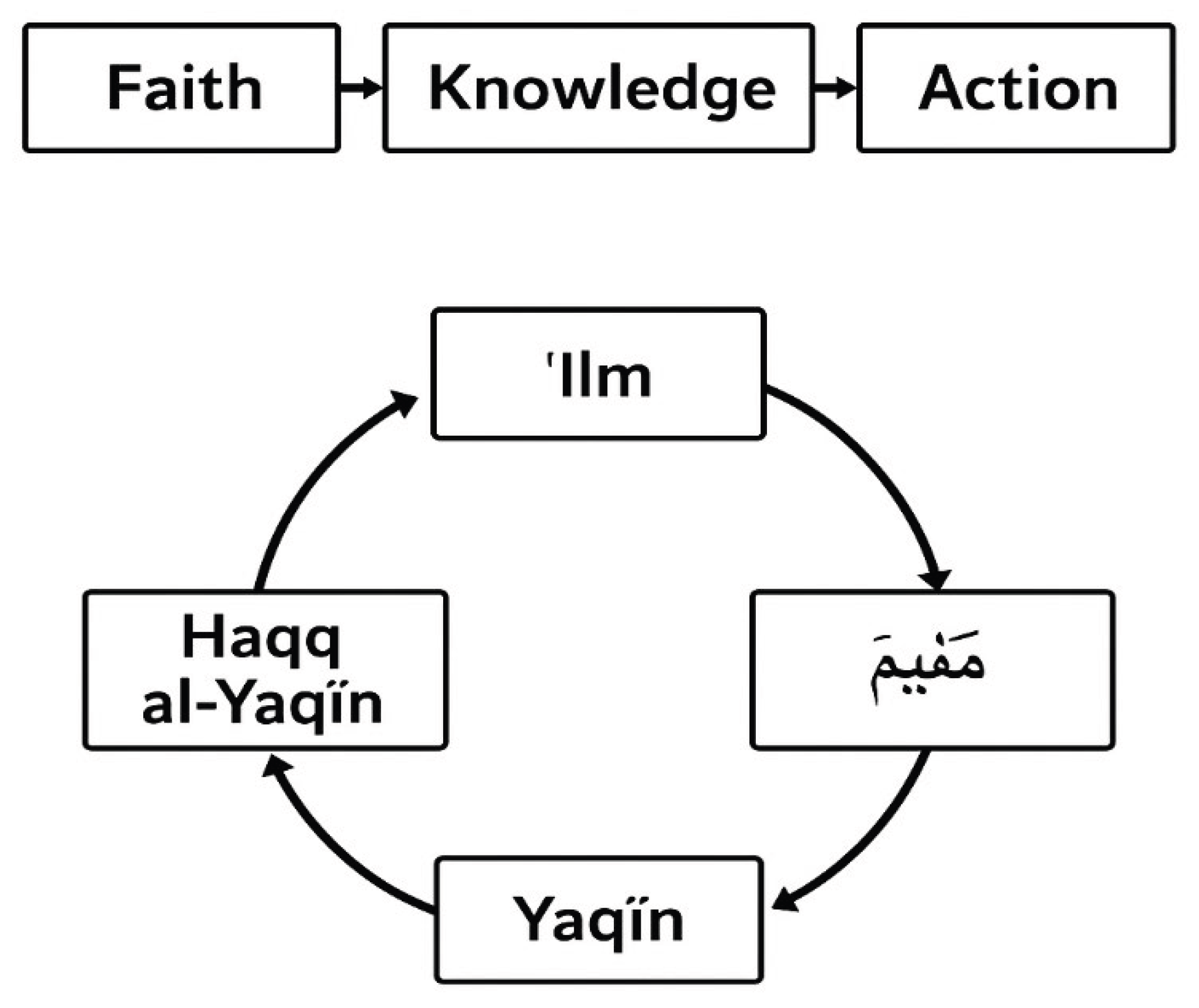

4.3. The Dynamic Relationship between Faith → Knowledge → Action

Faith (īmān), knowledge (ʿilm), and action (ʿamal) form an inseparable triad within Qur’anic thought. Faith gives purpose and orientation to knowledge, knowledge deepens faith, and both culminate in ethical action. The Qur’an states:

“Those who believe and do righteous deeds—Allah will increase them in guidance and grant them their reward” (Qur’an: 47:17).

Here, knowledge is not static but progressive—linked to moral responsibility and divine guidance. The Qur’an repeatedly uses verbs of action (e.g., yaʿmalūn, yafʿalūn) alongside those of belief (yuʾminūn), suggesting that epistemology in Islam is performative. Knowing leads to doing, and doing reinforces knowing.

This dynamic process also counters the dichotomy between theoretical and practical knowledge prevalent in Western epistemology. In Qur’anic terms, ʿilm is validated through ʿamal—knowledge without action is incomplete, and action without knowledge is misguided. The Qur’an exemplifies this when warning the Children of Israel:

“Why do you say what you do not do? Most hateful it is in the sight of Allah that you say what you do not do” (Qur’an: 61:2–3).

Hence, the epistemic cycle is not only intellectual but ethical and existential. True knowledge transforms the knower and radiates in just, compassionate action in society.

4.4. Evidence of Cyclical Validation (ʿIlm → Yaqīn → Ḥaqq al-Yaqīn)

The Qur’anic hierarchy of certainty—ʿilm al-yaqīn (knowledge of certainty), ʿayn al-yaqīn (vision of certainty), and ḥaqq al-yaqīn (truth of certainty)—outlines a cyclical validation process in Islamic epistemology. It moves from intellectual comprehension to empirical verification and finally to experiential realisation.

Allah says:

“Nay! If you only knew with certainty of knowledge (ʿilm al-yaqīn), you would surely see the Hellfire (ʿayn al-yaqīn). Then you shall surely see it with the eye of certainty (ḥaqq al-yaqīn)” (Qur’an: 102:5–7).

This threefold structure suggests that Qur’anic knowledge is not linear but progressive and recursive. The journey begins with rational understanding, advances through direct observation, and culminates in spiritual truth. The highest form, ḥaqq al-yaqīn, unites intellect and revelation into a singular perception of truth.

In modern epistemological terms, this mirrors the empirical-scientific process followed by moral realisation: hypothesis (ʿilm), verification (ʿayn), and ethical application (ḥaqq). The Qur’an’s layered concept of certainty thus integrates cognitive, empirical, and moral validation in one continuum of discovery.

4.5. Qur’anic Principles of Intellectual Honesty and Verification

One of the cornerstones of Qur’anic epistemology is intellectual honesty—rejecting speculation, hearsay, and unfounded assumptions. Qur’an: 17:36 articulates this moral law:

“Do not follow that of which you do not know (lā taqfu mā laysa laka bihi ʿilm).”

This command discourages unverified belief and aligns closely with the modern scientific principle of evidence-based reasoning. The verse also emphasises three faculties—hearing, sight, and heart—as tools of cognition, implying a holistic epistemology encompassing sensory, rational, and spiritual perception.

Similarly, the Qur’an condemns conjecture (ẓann), false reporting, and intellectual arrogance:

“And do not pursue what you do not know of” (Qur’an: 17:36);“Most of them follow nothing but assumption. Indeed, assumption avails nothing against the truth” (Qur’an: 10:36).

The epistemic ethos of the Qur’an is thus anchored in verification (taḥqīq) and integrity (ṣidq). Knowledge claims must be accountable to both rational inquiry and divine guidance. In this sense, Qur’anic epistemology anticipates modern principles of critical thinking and peer validation but transcends them through its spiritual orientation toward truth (ḥaqq).

Figure 2.

Summarising this “Faith–Knowledge–Action” cycle and the ʿIlm → Yaqīn → Ḥaqq al-Yaqīn progression.

Figure 2.

Summarising this “Faith–Knowledge–Action” cycle and the ʿIlm → Yaqīn → Ḥaqq al-Yaqīn progression.

In conclusion, the Qur’anic logic of discovery is a multi-layered process uniting faith, intellect, and ethics. It begins with empirical observation, develops through reflective reasoning, and culminates in spiritual certainty. Unlike secular epistemologies that separate science from morality, the Qur’an integrates them into a holistic model of knowing—where every act of inquiry becomes an act of worship, and every discovery a reaffirmation of divine order. This model positions Islam not as anti-intellectual but as a faith that sacralizes the pursuit of truth in all its forms—rational, empirical, and transcendental.

5. Discussion

The discussion section situates the proposed Qur’anic research methodology within the broader landscape of Islamic intellectual history and modern epistemological discourse. By engaging with classical scholars such as Al-Ghazālī, Ibn Rushd, and Al-Fārābī, this section demonstrates how the Qur’an’s vision of knowledge unites reason (ʿaql) and revelation (waḥy) into a single, coherent framework. It further contrasts the Qur’anic model with the modern scientific method, revealing the former’s emphasis on ethical accountability, spiritual insight, and ontological unity under Tawḥīd. Through this comparative lens, the discussion highlights how the Qur’an’s integrative process—linking īmān (faith), ʿilm (knowledge), and ʿamal (action)—avoids the pitfalls of materialistic reductionism and provides a timeless paradigm for intellectual honesty, moral research, and the pursuit of truth as a sacred responsibility.

5.1. Revisiting Classical Foundations: Integrating Reason and Revelation

The Qur’anic epistemological structure, when analysed as a process of observation, reflection, validation, synthesis, and application, resonates profoundly with the intellectual legacy of classical Islamic scholars such as Al-Ghazālī, Ibn Rushd, and Al-Fārābī. Each of these thinkers approached knowledge (ʿilm) as both a spiritual and rational pursuit grounded in the Qur’an’s view of the human intellect (ʿaql) as a divine trust.

Al-Ghazālī (1058–1111) in Iḥyāʾ ʿUlūm al-Dīn and al-Munqidh min al-ḍalāl framed knowledge as a process beginning in sensory perception (ḥiss), maturing through reason (ʿaql), and culminating in divine illumination (nūr). His synthesis between revelation (waḥy) and reason reflects the Qur’anic imperative to reflect (tafakkur) and verify (tabayyun), while ensuring that reason operates within the ethical and spiritual boundaries set by revelation.

By contrast, Ibn Rushd (Averroes, 1126–1198) emphasized rational inquiry as a legitimate form of worship, arguing that the Qur’an itself commands intellectual investigation into creation (e.g., “Do they not contemplate within themselves?” – Qur’an: 30:8). Ibn Rushd viewed the harmony between philosophy and revelation as evidence of the Tawḥīd (unity) of truth — the idea that both revelation and rational inquiry lead to the same ultimate knowledge of God’s creation.

Meanwhile, Al-Fārābī (872–950), in al-Madīnah al-Fāḍilah, conceptualised knowledge as an emanation of divine intellect received through human reasoning and social learning. He saw the prophetic intellect as the highest manifestation of knowledge — a view directly aligned with the Qur’anic model where revelation (waḥy) represents the highest epistemic certainty (ḥaqq al-yaqīn).

In combining these views, we see a continuum: from Al-Fārābī’s rational metaphysics, to Ibn Rushd’s intellectual realism, to Al-Ghazālī’s spiritual verification. All are reflections of the Qur’anic research process that integrates observation, contemplation, verification, and synthesis into an ethically grounded system of knowing.

5.2. Qur’anic Epistemology vs. Modern Scientific Method

Modern scientific methodology, emerging from the Enlightenment era, is primarily based on empirical verification and causal determinism. Knowledge is confined to observable phenomena, often divorced from metaphysical or moral dimensions. In contrast, Qur’anic epistemology adopts a holistic epistemic model—combining empirical investigation (naẓar), rational interpretation (ʿaql), and moral guidance (ḥikmah).

While both systems value observation and reasoning, their ontological foundations differ sharply. Modern science often assumes a materialist ontology, treating existence as purely physical and measurable. The Qur’an, however, asserts a theocentric ontology, where the seen (shahādah) and unseen (ghayb) coexist as parts of one reality (Qur’an: 2:3, “Those who believe in the unseen…”). Knowledge in Islam, thus, cannot be reduced to mere material processes; it must also encompass moral consciousness, divine purpose, and spiritual accountability.

For example, when the Qur’an invites humanity to “travel through the earth and see how creation began” (Qur’an: 29:20), it is not merely urging empirical observation, but a moral-intellectual journey linking the physical evidence of creation to the awareness of divine wisdom. This contrasts with the secular scientific quest, which isolates facts from their transcendent meaning.

Furthermore, Qur’anic methodology employs a recursive validation process — ʿIlm → Yaqīn → Ḥaqq al-Yaqīn — that emphasises increasing levels of certainty. Modern science, by contrast, remains falsification-based, valuing provisional knowledge subject to change. While this fosters adaptability, it lacks the teleological coherence that the Qur’an provides through the principle of Tawḥīd — the unity of knowledge under divine truth.

5.3. Avoiding Materialistic Reductionism: Ethical and Metaphysical Balance

The Qur’an’s epistemology resists materialistic reductionism by refusing to separate knowledge from ethics. The verse “Do not pursue that of which you do not know” (lā taqfu mā laysa laka bihi ʿilm – Qur’an: 17:36) sets an epistemic boundary that modern science rarely acknowledges: knowledge without ethical verification can become destructive. This principle embodies intellectual accountability, reminding researchers that truth-seeking must serve justice, compassion, and human welfare — not domination or exploitation.

This ethical balance is further demonstrated in the Qur’an’s repeated calls to tafakkur (reflection) and tadabbur (deep contemplation). Both imply an inward discipline of thought—an epistemic humility acknowledging that human knowledge is always partial and dependent on divine truth. The Qur’an states: “Of knowledge, you have been given but little” (Qur’an: 17:85), positioning revelation not as a limitation on science but as its moral compass.

By linking knowledge (ʿilm) to wisdom (ḥikmah) and faith (īmān), the Qur’an prevents reductionism at both ends: it guards against blind empiricism and against speculative mysticism devoid of evidence. Hence, true Qur’anic inquiry is integrative, where empirical, rational, and spiritual insights interact within a framework of divine purpose.

5.4. Implications for Islamic Education, Scientific Research, and Social Sciences

The Qur’anic research model has profound implications for Islamic education and contemporary research paradigms. In education, it calls for a curriculum that unites revelation (naql) and reason (ʿaql) — integrating natural sciences with ethical and spiritual instruction. This is a revival of the classical ʿIlm al-Tawḥīdī approach, seen in early Muslim universities such as Al-Qarawiyyīn and Al-Azhar, where theology, philosophy, medicine, and astronomy coexisted harmoniously.

In modern scientific research, adopting a Qur’anic epistemology means reintroducing purpose and morality into the scientific method. Observation (naẓar) must be linked with reflection (tafakkur), and verification (burhān) with ethical synthesis (ḥikmah). Such a model would redefine research as a form of ʿibādah (worship), where discovering natural laws becomes an act of recognising divine order. This aligns with Qur’anic calls to “reflect on the creation of the heavens and the earth” (Qur’an: 3:190–191).

For the social sciences, this methodology encourages contextual and value-based interpretation rather than positivist abstraction. Knowledge of human behaviour, societies, or economies should be studied through both empirical observation and moral discernment, acknowledging that human beings are moral agents, not merely data points. Thus, Qur’anic epistemology restores the unity of the moral and material within social research.

5.5. Tawḥīd: The Unity of Truth as an Epistemic Paradigm

At the heart of the Qur’anic epistemology lies the principle of Tawḥīd—the unity of all knowledge under the sovereignty of Allah. Tawḥīd dissolves the artificial dualism between the sacred and the secular, positioning every act of knowing as an act of worship (ʿibādah). The Qur’an declares, “He taught Adam the names of all things” (Qur’an: 2:31), signifying that human cognition itself originates from divine instruction.

This unity of truth ensures that no branch of knowledge is inherently “un-Islamic”; what matters is the intention (niyyah) and orientation (qiblah) of inquiry. When the researcher’s aim aligns with divine purpose — seeking truth, justice, and benefit for creation — their knowledge becomes part of a unified field of divine wisdom. Conversely, when inquiry divorces itself from moral accountability, it becomes fragmented and spiritually sterile.

In practical terms, Tawḥīd as an epistemic paradigm demands integration between revelation and empiricism, ethics and logic, theory and practice. The Qur’anic model of ʿIlm → Yaqīn → Ḥaqq al-Yaqīn exemplifies this integration: it begins with intellectual understanding, advances to experiential certainty, and culminates in realised truth — a journey that mirrors the movement from faith (īmān) to knowledge (ʿilm) to action (ʿamal).

Thus, the Qur’anic methodology represents not merely an alternative research framework but a reorientation of epistemology itself — from fragmented human reasoning toward a unified, morally accountable, divinely guided pursuit of truth.

6. Conclusion and Recommendations

The present study has sought to derive a coherent and holistic Qur’anic research methodology grounded entirely in the epistemic principles of the Qur’an itself. By examining the interrelation of ʿilm (knowledge), ʿaql (reason), tafakkur (reflection), tadabbur (deep contemplation), ḥikmah (wisdom), and īmān (faith), this research has shown that the Qur’an provides not only theological doctrines but also an embedded scientific and intellectual method for the discovery of truth. The Qur’anic model views knowledge as a sacred trust—both rational and revelatory—and considers inquiry a divine obligation. It integrates observation (naẓar), reflection (tafakkur), validation (burhān), synthesis (ḥikmah), and application (ʿamal) into a cyclical process that refines understanding and transforms it into moral action.

A central finding of this study is that the Qur’an does not separate empirical inquiry from spiritual reflection. Instead, it commands humankind to observe the heavens, the earth, and the self as interconnected signs (āyāt). This divine imperative establishes the Qur’an as a living epistemic framework, where truth is revealed through the interaction between revelation and reasoning. The faith–knowledge–action cycle thus becomes the foundation of human progress, ensuring that intellectual pursuits remain grounded in ethical awareness and divine accountability. In contrast to modern positivist science—which isolates knowledge from metaphysical meaning—the Qur’anic paradigm situates discovery within the moral and ontological unity of Tawḥīd. This prevents reductionism and aligns inquiry with the higher purpose of human existence: to seek truth (ḥaqq) and act upon it with justice (ʿadl).

The discussion also underscores that classical Muslim thinkers, such as Al-Ghazālī and Ibn Rushd, already anticipated elements of this Qur’anic method in their works. Al-Ghazālī emphasised the purification of intention and the unity of reason and faith, while Ibn Rushd promoted logical analysis and empirical validation within the bounds of revelation. However, the current study demonstrates that the Qur’an itself serves as the primary epistemological source from which these philosophical frameworks emerged. By returning to the Qur’an’s own structure of reasoning—its appeals to evidence, its encouragement of observation, and its insistence on ethical verification—Muslim scholarship can reconstruct a comprehensive research paradigm capable of guiding both religious and scientific disciplines.

The implications of this Qur’anic methodology extend far beyond theology. In education, it encourages a reintegration of faith and reason, advocating for curricula that cultivate tafakkur and tadabbur alongside technical skills. In the natural and social sciences, it calls for methodologies that harmonise empirical data with moral reflection, recognising that truth cannot be divorced from values. In governance and policy-making, it provides a moral compass grounded in divine accountability and intellectual transparency. Such applications reaffirm that knowledge, in the Qur’anic sense, is not an end in itself but a means toward ethical transformation and societal balance (mīzān).

Future research should therefore focus on operationalising this Qur’anic epistemology into practical methodologies. This could involve:

Developing curricular frameworks that teach Qur’anic methods of observation and reasoning as foundational research skills.

Establishing Qur’anic research centres that apply these principles to contemporary scientific, ethical, and social challenges.

Conducting comparative studies between Qur’anic and modern epistemological systems to identify complementary approaches and areas of integration.

Formulating ethical guidelines for research based on Qur’anic principles such as ṣidq (truthfulness), amānah (trust), and ʿadl (justice).

Ultimately, the Qur’an envisions human inquiry as an act of worship—an intellectual journey toward recognising divine unity in all aspects of creation. By recovering this vision, Muslim scholars can move beyond imitation of external epistemologies and instead rebuild a dynamic, authentic, and spiritually integrated model of knowledge rooted in revelation. The Qur’anic research methodology proposed in this study thus stands not merely as an academic model but as a living framework for ethical discovery, ensuring that every pursuit of knowledge contributes to the realisation of truth (ḥaqq al-yaqīn) and the perfection of faith (īmān).

References

- Al-Fārābī. The Political Regime (Al-Siyāsah al-Madaniyyah); Najjar, F. M., Ed.; Cornell University Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghazālī. The Incoherence of the Philosophers (Tahāfut al-Falāsifah); Marmura, M. E., Translator; Brigham Young University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghazālī. The Revival of the Religious Sciences (Iḥyāʾ ʿUlūm al-Dīn); Dar al-Fikr, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rāzī, Fakhr al-Dīn. Al-Tafsīr al-Kabīr (Mafātīḥ al-Ghayb); Dār al-Fikr, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ṭabarī. Jāmiʿ al-Bayān ʿan Taʾwīl Āy al-Qurʾān (30 vols.); Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qurʾān. n.d.; The Holy Qur’an: English Translation of the Meanings and Commentary; King Fahd Complex for the Printing of the Holy Qur’an: Madinah.

- Al-Qurtubī. Al-Jāmiʿ li-Aḥkām al-Qurʾān (20 vols.); Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣriyyah: Cairo, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rāghib al-Iṣfahānī. Mufradāt Alfāẓ al-Qurʾān. In Dār al-Maʿrifah; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rumi, F. Manhaj al-Qurʾān fī Iqāmat al-Ḥujjah; Maktabat al-Rushd: Riyadh, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tahanawi, M. A. Kashshāf Iṣṭilāḥāt al-Funūn wa’l-ʿUlūm; Dār Ṣādir: Beirut, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Attas, S. M. N. Prolegomena to the Metaphysics of Islam: An Exposition of the Fundamental Elements of the World-view of Islam; International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilisation (ISTAC): Kuala Lumpur, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Chittick, W. C. The Self-Disclosure of God: Principles of Ibn al-ʿArabī’s Cosmology; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Rushd (Averroes). The Incoherence of the Incoherence (Tahāfut al-Tahāfut); Van den Bergh, S., Translator; E. J. W. Gibb Memorial Trust, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Sīnā, Avicenna. The Book of Healing (Kitāb al-Shifāʾ); Islamic Texts Society, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M. The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam; Oxford University Press, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, S. H. The Need for a Sacred Science; State University of New York Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, F. Islam and Modernity: Transformation of an Intellectual Tradition; University of Chicago Press, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Sardar, Z. Exploring Islam: Essays on Islamic Thought and Culture; Grey Seal, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, M. N. Qur’anic Epistemology and Scientific Thinking; Islamic Research Institute: Islamabad, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Toshihiko, I. The Concept of Belief in Islamic Theology: A Semantic Analysis of Īmān and Islām; Keio Institute: Tokyo, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Ziauddin, S. Reading the Qur’an: The Contemporary Relevance of the Sacred Text of Islam; Oxford University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).