Introduction

Undernutrition as a Global Emergency and the Production-Population Gap (1981)

All international organizations (FAO, UNESCO, WHO, etc.) agree that the current increase in population does not correspond to an adequate increase in food production.

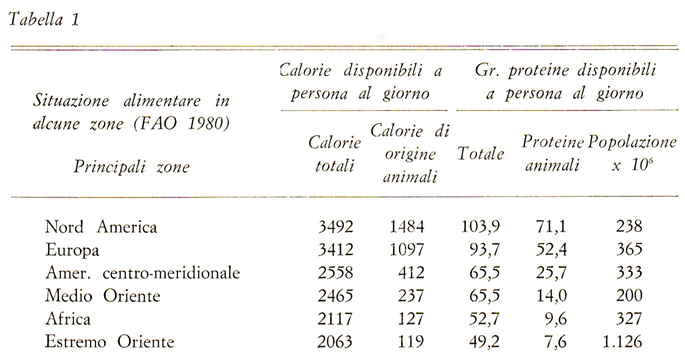

Today, approximately half of the world’s population is undernourished, both due to an insufficient specific protein intake, and particularly due to a lack of animal-source protein (Daylor, Gualtierotti, Cosci, FAO) (

Table 1).

The populations of tropical countries are particularly affected, as demonstrated by the high infant mortality rate, largely due to undernutrition, which, according to WHO data, averages 100–200 per thousand live births, even reaching, for example, a rate of 50% among children under five years of age in the areas of Upper Volta, Mauritania, Senegal, Mali, and Nigeria (Davy, Mattei, Salomon, FAO, Hecq, Binay, Ranjan, Sen).

FAO reports state that the diet, generally scarce, is primarily based on cereals and starchy products.

WHO reports add that this diet is qualitatively inadequate due to the low protein intake and the deficiency of certain vitamins.

Furthermore, FAO and WHO assert that unfavorable climatic conditions create significant hygiene and sanitary problems concerning food preservation and protection.

In this regard, Ruggiero and Nicastro highlighted the consequences resulting from a prolonged diet based on mycotoxin-contaminated food, as occurs in Somalia, Uganda, Kenya, etc.

Casadei, referring to Benin, states that a generally insufficient diet is accompanied by a deficiency in vitamins and trace elements.

The Current Landscape (2025): Progress and the Persistent Challenge of Malnutrition

Four and a half decades after the alarm sounded by international bodies, the global food security picture presents a narrative of dramatic quantitative progress juxtaposed with entrenched qualitative failures.

The most striking success is the significant reduction in the prevalence of chronic undernourishment (hunger), which has dropped from an estimated half of the world

’s population in the early 1980s to approximately 8.2% today, though nearly 2.3 billion people remain in a state of moderate or severe food insecurity [

2]. Furthermore, the immense decrease in under-five mortality is testament to successful health and nutrition interventions; while the 1981 rate averaged 100–200 per 1,000 live births in tropical nations, today the global rate is 37 per 1,000 (2023) [

3].

However, the burden remains disproportionately concentrated, with the rate in Sub-Saharan Africa - the region with the heaviest burden - standing at 68 per 1,000 and accounting for 58% of all under-five deaths worldwide. This progress is still insufficient to meet the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target [

4].

However, the fundamental challenge of a qualitatively inadequate diet (protein and vitamin deficiencies) has tragically persisted, shifting focus from raw calorie deficit to micronutrient malnutrition or ‘hidden hunger’. In 2022, approximately 23.2% of children globally suffered from stunting (low height-for-age), and 45 million children were wasted (too thin for height), direct indicators of chronic nutrient scarcity and protein-energy undernutrition. The concern regarding food quality has also been complicated by the emergence of the

‘double burden of malnutrition

’, where undernutrition coexists with overweight and obesity, particularly in low- and middle-income countries [

5].

Finally, the issue of food safety and preservation remains a major obstacle. While the threats of infectious diseases have been addressed in some regions, the problem of mycotoxin contamination, specifically highlighted in the 1981 article, continues to pose a severe health risk, often exacerbated by the volatile climatic conditions and lack of adequate infrastructure for storage and distribution [

6].

In summary, while the global fight against mass hunger has seen victories over 45 years, the challenge has evolved from sheer calorie deficits to a complex crisis of nutrient quality and unequal distribution, highlighting the persistent structural fragility of food systems in tropical regions.

Protein Deficiency and Nutritional-Sanitary Collapses (1981)

Indeed, 80% of dietary calories are generally composed of cereals such as maize and sorghum which, even if consumed in sufficient quantities to satisfy nitrogen requirements, provide imbalanced proteins because certain amino acids are deficient, such as lysine in sorghum and lysine and tryptophan in maize. Furthermore, it must be noted that the net protein utilization, which is 40% in diets containing animal proteins, is lower in diets containing lower-quality proteins (Scrimshaw).

Still regarding Benin, Panatta states that in children and adolescents, certain scalp disorders are frequently evident, generally considered expressions of disturbances in protein nutritional status.

40% of the individuals examined, both adults and children, showed riboflavin (Vit. B2) deficiency, seborrheic dermatitis, blepharitis, etc. Analogous situations are reported by Cosci for Burundi.

The food situation worsens in areas where the staple food, composed of cereals, is not alternated with other foods. In these areas, livestock is usually not slaughtered for food purposes due to reasons of social prestige, religion, etc.

This deficient nutritional situation is compounded by a health situation that is often extremely disheartening. Ferruzzi reports the following data in his report on Upper Volta: 3 hospitals, 267 dispensaries, 3 maternity clinics, 30 health centers, and half a doctor for every 92,000 inhabitants. Most common diseases: tropical diseases, malaria, parasitic diseases, poliomyelitis, and infestations of the throat and eyes, especially when the desert wind blows.

The Current Landscape (2025): Persistence of Qualitative Malnutrition and Health Challenges

Four and a half decades later, the 1981 analysis concerning the poor protein quality of the diet and deficient health infrastructure remains, sadly, relevant, although with significant changes.

The reliance on cereal-based diets, such as maize and sorghum, which still account for over 50% of caloric needs in some Sub-Saharan African countries, continues to cause a critical deficiency of essential amino acids, particularly lysine and tryptophan. Current research confirms that, even when accounting for the lower protein quality, lysine availability is insufficient for a significant proportion of the poorest households in nations like Malawi, exacerbating childhood stunting rates [

7]. Despite the existence of High-Quality Protein Maize (QPM) varieties, their adoption has not yet been sufficient to close the nutritional gap on a large scale.

The problem of micronutrient deficiencies, such as riboflavin (Vitamin B2), which was cited with a 40% prevalence, also persists. Recent estimates indicate that riboflavin deficiency remains highly prevalent across wide areas of Sub-Saharan Africa, with rates in some areas (such as Côte d’Ivoire) reaching 65% of school-age children, often coexisting with other deficiencies and parasitic infections [

8]. These deficiencies, which stem from the lack of dietary diversity and low consumption of meat and dairy products (often limited by socio-economic and cultural factors like the prestige associated with livestock), contribute to “hidden hunger” and the clinical manifestations once observed (dermatoses, blepharitis, etc.).

Finally, the gap in health infrastructure, exemplified by the shocking 1981 data for Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso) of half a doctor per 92,000 inhabitants, has seen a quantitative improvement but remains an enormous disparity. The physician-to-population ratio in Burkina Faso has improved significantly, rising from approximately 0.011/1000 in 1981 to about 0.07/1000 in 2022 [

9], but this figure is still well below the minimum threshold recommended by the World Health Organization for guaranteeing essential health services. This chronic deficit of healthcare personnel exacerbates the impact of endemic diseases, particularly malaria and parasitoses, which continue to hinder the physical and cognitive development of children and adults, creating a vicious cycle with malnutrition.

In essence, the decades have transformed the food crisis from one of basic calorie scarcity to a complex issue of nutrient quality and distribution, demonstrating that while quantitative healthcare access has marginally improved, the fundamental structural barriers - from dietary quality to critical physician deficits - cited in 1981 largely persist and still define health outcomes in tropical nations.

This persistent deficit is largely attributed not to a failure in food production capacity, but to the entrenched structural fragility of the food and health systems - including chronic underinvestment, reliance on monoculture, high economic inequality, and the destabilizing impact of climate change and internal conflicts - which prevents sustained and equitable access to safe and nutritious diets.

The Current Landscape (2025): Technology and Structural Losses

The 1981 analysis, which focused on increasing production and reducing losses as the primary solution to poverty, reflected the prevailing post-war development approach. Decades later, these strategies have been widely adopted, yet the impact has been uneven, revealing new and complex challenges.

The proposals to boost agricultural production (increasing yield, enhancing soil fertility, and raising energy inputs) have become a cornerstone of initiatives like Agritech and Agroforestry in Sub-Saharan Africa. While agricultural productivity in the region is projected to grow (by about 3.2% annually over the next five years, according to the World Bank), this growth has been significantly curtailed by climate change [

10]. The introduction of drought- and heat-tolerant crop varieties and the use of precision farming tools (which optimize the use of fertilizers and water, linked to energy inputs) have proven effective in boosting yields and resilience [

11].

However, the increase in energy inputs (particularly the use of chemical fertilizers) has remained much lower in Sub-Saharan Africa (which historically used about 3% of the commercial energy for chemical fertilizer production in the developing world) compared to other regions, limiting the potential for yield increases [

12].

The issue of reducing post-harvest losses (PHL), cited as essential in 1981, is now a crucial policy target. The African Union, for example, set the goal of halving post-harvest losses by 2025 (as part of the Malabo Declaration) [

13]. These losses, primarily attributed to pests and storage in 1981, are now addressed through the large-scale introduction of hermetic storage technologies (like metal silos and hermetic bags) and via training and strengthening of the cold chain for perishable goods [

14]. Despite political focus and new technologies, losses remain structurally high due to inadequate rural infrastructure (roads and energy grids), which compounds losses during transportation and processing.

Finally, the objective of “narrowing the gap” between surplus and deficit countries remains a significant challenge, with projections indicating that Africa’s spending on food imports could reach US

$110 billion by 2025 [

15], highlighting that domestic production still fails to meet the needs of a rapidly growing population.

The analysis reveals a bifurcated outcome: while technological progress has been made in increasing yields (e.g., climate-resilient crops) and reducing post-harvest losses (e.g., hermetic storage), these advances are severely undercut by structural stagnation—particularly in chronic underinvestment in energy inputs and rural infrastructure—which preserves the food import dependency and unequal distribution that the 1981 authors sought to remedy.

One hypothesis for the sustained failure to eradicate these deficiencies is that the focus on technical efficiency (yields and storage) has consistently overshadowed the necessary, but politically difficult, systemic reforms required to address deeply entrenched economic inequality, governance deficits, and political instability, which are the true root causes of access and nutritional poverty.

Materials and Methods

1981

The data utilized were collected:

In climatic chambers or in the field (details on the various techniques adopted will be provided during the course of the work) and retrieved from the FAO, UNESCO, the Istituto Agronomico per l’Oltremare in Florence, and the WHO.

The methodologies followed are explained in the course of the work; for more detailed information, reference can be made to the mathematical model, employed for the resolution of agrometeorological problems, adopted by the Institute of Agronomy of the Faculty of Agriculture of Pisa (Nicastro 1974-1977; Ruggiero-Nicastro).

2025

The methodological framework of 1981, while rigorous for its time (based on field/climatic chamber data, international agencies like FAO and WHO, and local mathematical models from the University of Pisa), has radically changed. The collection, analysis, and modeling of agrometeorological data have shifted from a sampling-based approach to one based on Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (AI).

The major agencies cited in 1981 are now the pillars of global data science:

FAO and WHO: These agencies continue to be the primary sources, but their data collection methodology has evolved significantly. The FAO’s current assessment cycle (e.g., the FRA 2025 Remote Sensing Survey) integrates satellite technologies and remote sensing to collect high-resolution data on crops, land use, and forests, often in collaboration with platforms like Google Earth and NASA [

16], moving far beyond the limitations of field or climatic chamber data alone. The FAO’s Hand-in-Hand Geospatial Platform now combines over two million layers of geospatial data and agricultural statistics, making information much more accessible and granular [

17].

National and International Bodies: The Istituto Agronomico per l

’Oltremare (IAO) in Florence, which served as a national cooperation hub in 1981, maintains its role today by providing technical-scientific consultancy and support to Italian Cooperation in tropical agriculture and sustainability, but it operates within a vast global network of institutional partners and development agencies [

18].

The “mathematical modeling” for agrometeorological problems (like the Pisa model cited in 1981) has been revolutionized by the advent of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML). Traditional mathematical models (based on physics) are now supplemented and often surpassed by hybrid AI models. Algorithms such as Random Forests and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) are used to predict with greater accuracy temperature, precipitation, and drought susceptibility, significantly reducing prediction errors compared to conventional methods [

19].

For example, the large language model (LLM) based on AI used in the present work (e.g., Gemini) is capable of rapidly analyzing and synthesizing a volume of scientific data (including the results of these advanced models) that would have been unimaginable in 1981. Its role served as an analysis and comparison tool, capable of retrieving the 1981 text, researching the scientific evolution in real-time (such as the use of satellites and ML models), and structuring the comparison, transforming complex contemporary scientific production into actionable insights for this analysis.

In summary, the knowledge base supporting the research has transitioned from laboratory measurements and localized models to an ecosystem of global, satellite-derived, and AI-driven predictive data, fundamentally transforming the capacity to understand and address agrometeorological problems.

Results and Discussion

The Causes of Deficient Food Production in Tropical Countries (1981)

The food production deficiency in tropical countries, both quantitative and qualitative, finds its causes in the following four factors:

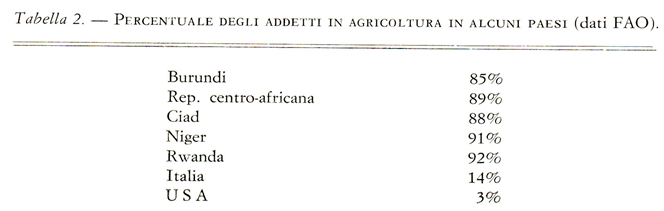

1. Excessive Labor Force: In tropical countries, 40–50% and sometimes up to 90% of the active population is dedicated to agriculture, compared to 3% of the population in the United States (

Table 2).

2. Land Exploitation: One of the most widespread techniques for cultivating land is “slash-and-burn,” particularly in Africa, Latin America, and Asia. The fire destroys weeds and their seeds, and ashes containing notable doses of Ca, P, and K are deposited on the soil (Bidwell, Calcaterra, FAO).

The soil thus obtained is only potentially fertile because the fire destroys humus, leading to a consequent decrease in fertility. After the initial years, production rapidly declines, especially in the absence of adequate (and too expensive) fertilization, and the land is abandoned. A sparse, savanna-like vegetation then grows on these abandoned lands (Schultz, Staley). This opens the way to desertification (Nistri-Hecq), a phenomenon of considerable extent, as highlighted by the UN at the Nairobi Conference in 1977.

According to FAO data, one-tenth of South America, one-fifth of Asia and Africa, and one-quarter of Australia are condemned to desertification if urgent and definitive measures are not taken.

3. Disappearance of Local Varieties and Uniformity of Cultivated Plants: Following the logic of greater profit, local varieties have been replaced by highly productive ones (Duthil, Lowry, Bidwell), such as maize, wheat, and cotton, which in North America have, in some cases, doubled harvests.

Between 1970 and ‘71, thousands of tons of “super seeds” were sent to Afghanistan to avert the threat of famine due to a two-year drought. However, these new wheat seeds led to the disappearance of the ancient varieties that had fed Afghanistan for hundreds of years.

It should be remembered that when a species disappears, a genetic heritage is lost that can be enormously useful in certain environmental situations. Today, what worries doctors and agronomists most, because of the repercussions that may arise in the near future, is the concomitance, as is currently occurring, between a decrease in spontaneous species and a uniformity of crops. In fact, most human nutrition is currently based on only four cereals: wheat, rice, maize, and sorghum. If, for any reason, one of these crops were to fail, or if a new plant disease appeared that we could not eradicate, we would inevitably face a disaster of vast proportions, as happened in the Sahel in 1970. Due to drought, thousands of hectares of a new high-yield millet variety withered. More than 100,000 people died of starvation. Those who survived were able to rely on some more resistant local millet varieties that managed to grow on the arid land.

4. Technological Situation: Practically non-existent, in the sense that the use of machinery and modern technical innovations is not implemented, as it is too costly for these countries.

The Causes of Deficient Food Production in Tropical Countries: A 45-Year Review

The four causal factors identified in the 1981 analysis that drove quantitative and qualitative food deficiency in tropical countries - labor imbalance, land exploitation, genetic uniformity, and technological deficit - present a complex, yet disheartening, picture four decades later. While some challenges have been technologically mitigated, their underlying structural nature persists, often in a new form.

1. Excessive Labor Force and Low Productivity

The 1981 concern over the excessive labor force dedicated to agriculture (40–90% of the active population) remains a core issue, though the dynamics have shifted. While rapid urbanization is underway (Sub-Saharan Africa is projected to become predominantly urban by 2043), the agricultural sector is still the primary employer, engaging over 60% of the total workforce in Sub-Saharan Africa [

20]. This phenomenon has transitioned from one of mere over-supply to one of deep rural underemployment and low productivity. The slow pace of structural transformation means the agriculture sector fails to create sufficient value-added employment or release labor to other sectors, maintaining a reliance on inefficient, subsistence-level farming.

2. Land Exploitation and Desertification

The problem of land exploitation and subsequent desertification, flagged by the destructive “slash-and-burn” technique, has escalated into a recognized global crisis. Today, up to 40% of the world

’s land is degraded, with an estimated 65% of productive land in Africa now affected [

21]. The underlying drivers of degradation - such as the abandonment of land fallowing (soil resting) due to demographic pressure, declining from 20% to just 2% of agricultural land in some areas - continue unabated [

22]. Although solutions like agroforestry and conservation agriculture are well-known, their large-scale adoption remains stymied by socio-economic and institutional barriers, proving that the theoretical understanding of soil health vastly outpaces the practical, on-the-ground political will to reverse desertification.

3. Disappearance of Local Varieties and Crop Uniformity

The alarm raised in 1981 regarding the replacement of local crop varieties by highly productive, genetically uniform “super seeds” (driven by the profit motive) is now a central concern for global food system resilience. This phenomenon, known as agrobiodiversity loss or genetic erosion, continues at an alarming rate. The dependence on just four major cereals (wheat, rice, maize, sorghum) persists, amplifying the systemic risk: a single new plant disease or climate shock could trigger a disaster of Sahel-like proportions (1970) on a far greater scale [

23]. While there is now significant institutional progress in genebank conservation (ex situ) and a strong policy push for crop diversification, market forces and large-scale development programs still favor monoculture, ensuring the risk of widespread systemic failure remains high.

4. Technological Situation

The 1981 assessment of a “practically non-existent” technological situation in terms of machinery has been dramatically inverted. Today, revolutionary AgriTech (Precision Farming, IoT, AI, and remote sensing) is readily available globally. However, the core challenge has simply shifted from the cost of machinery to the cost and lack of infrastructure needed to implement modern technology. The pervasive “Digital Divide” - characterized by unreliable electricity, limited rural internet connectivity, and low digital literacy - now acts as the primary constraint on technology adoption by smallholder farmers. This effectively replicates the barrier of “too costly for these countries” in a new, infrastructural form, preventing technological gains from translating into widespread productivity increases [

24].

In retrospect, the analysis of 1981 proved highly prescient, pinpointing the dangers of genetic uniformity and the systemic path toward desertification—issues then marginalized, but now recognized as critical global emergencies—suggesting that a more immediate and focused response to these early warnings could have significantly altered the trajectory of food security and environmental stability in tropical regions today.

Indeed, far from being mitigated, the core systemic risks identified in 1981 - specifically the erosion of agrobiodiversity and accelerating land degradation - have arguably worsened, transforming from local vulnerabilities into interconnected global stability threats.

This persistent regression is largely hypothesized to stem from a foundational misalignment: the prioritization of short-term economic output and market-driven monoculture, which exacerbates structural inequalities, over the necessary long-term investments in ecosystem health and equitable access that ensure true food security.

The Paradox of Spending: Why Has Progress Stalled Since 1981?

Addressing the massive scale of funding dedicated to global development since 1981 provides a powerful contrast to the persistent - or worsening - outcomes observed in tropical agriculture and nutrition.

While calculating the total sum is impossible due to diverse sources and shifting priorities, the expenditure can be framed around key funding streams. Official Development Assistance (ODA) has disbursed trillions of dollars since 1981. Focusing specifically on the agricultural sector, the OECD estimates that ODA to agriculture and food security averaged around US

$6-8 billion annually in the last decade, with major spikes following crises. Over the course of four decades, this contribution alone easily runs into the hundreds of billions of dollars (FAO, IFPRI) [

25]. Private philanthropic investment, particularly since the early 2000s (spearheaded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation), has injected tens of billions of dollars directly into agricultural transformation, health, and nutrition in developing countries. This spending is highly targeted, often focusing on technology, breeding (

e.g., biofortification), and health delivery. National Spending and Private Investment constitute the largest, though least tracked, portion, involving national budgets of tropical countries and vast private sector investment in the global food supply chain, running into trillions of dollars over the period. The total sum spent - when accounting for ODA, philanthropy, and the related national and private sector spending over 40 years - is unquestionably in the trillions of dollars realm.

The “Failure” Hypothesis: Why Things Didn’t Improve

The paradox of massive spending yielding structural stagnation is often attributed to several critical issues, which align with the prescience of our 1981 paper by highlighting factors beyond simple production deficits.

Firstly, there has been a mismatched investment focus [

26]. Much of the aid followed the “Green Revolution” paradigm, emphasizing quantitative yield increases (e.g., through high-input seed and fertilizer packages) while neglecting qualitative factors like local genetic diversity, soil health, and specific nutritional needs (amino acid balance, micronutrients).

Our paper rightly highlighted the danger of genetic uniformity and soil exploitation in 1981; aid was slow to pivot away from the high-input model that exacerbated these issues.

Secondly, structural leakage and corruption dilute the impact [

27]. Funding, particularly ODA, is frequently diluted or diverted due to weak governance, corruption, and administrative inefficiency in recipient countries, preventing capital from reaching the smallholder farmers and infrastructure projects most in need.

Thirdly, there is a chronic lack of infrastructural investment. As noted in the previous section, money spent on AgriTech (technology) or improved seeds cannot yield maximum ROI without foundational rural infrastructure (roads, reliable electricity, water control, and cold chains). The absence of these enablers means the technology remains expensive and inaccessible- the “too costly” problem of 1981 reappears as the “digital divide” of 2025.

Finally, the impact of huge spending is constantly undermined by external shocks and persistence of conflict. Climate change (which our paper correctly warned would exacerbate desertification) and the surge in geopolitical conflicts and fragility since the early 2000s disproportionately affect tropical regions and instantly wipe out decades of agricultural gains (WFP, 2024).

In conclusion, the failure isn’t necessarily one of insufficient money, but one of misaligned investment and weak implementation against a backdrop of increasing climate instability and conflict, validating the argument that structural and systemic solutions were, and remain, necessary over simple resource injection.

Transition to Speculative Scenarios

If the failure to achieve widespread, equitable food security is, as argued, rooted in the misalignment of substantial global funding - prioritizing simple resource injection over systemic solutions - it compels a crucial, albeit counterfactual, question: What would the agricultural landscape look like today had that multi-trillion-dollar flow of aid and philanthropic capital been entirely withheld since 1981? The following scenarios explore two opposing outcomes, examining whether the sheer necessity of survival would have catalyzed stronger local solutions or simply resulted in a collapse due to lack of basic resources.

Scenario 1: The Self-Reliance Scenario

The absence of external funding post-1981, particularly the large-scale Official Development Assistance (ODA) that often subsidized unsustainable practices and distorted local markets, could have fostered a radical shift towards self-reliance in tropical nations. Faced with existential threats of famine and resource depletion, African governments might have been forced to prioritize internal governance, reduce corruption, and settle conflicts to focus exclusively on survival. This necessity would have catalyzed genuine, locally-adapted agricultural innovation, prioritized the preservation of resilient local crop biodiversity, and led to equitable land management, thus establishing robust, sustainable food systems that are independent of geopolitical and philanthropic influence, resulting in a fundamentally stronger socio-economic foundation today.

Scenario 2: The Collapse Scenario

Conversely, the cessation of all international funding and aid post-1981 would have resulted in an unmitigated humanitarian disaster. Without essential emergency food aid, health interventions (like vaccination programs), and technical assistance from multilateral agencies (FAO, WHO), mortality rates, particularly infant mortality, would have soared far beyond the already high levels of the 1980s. The vacuum of governance and capital would have intensified resource wars, state collapse, and massive population displacement, leading to unchecked famine and epidemic spread. Furthermore, the complete lack of investment in scientific research and critical infrastructure (however inefficiently managed) would have left nations defenseless against the looming threats of climate change and new plant diseases, guaranteeing a widespread systemic collapse and a humanitarian crisis of unimaginable scale today.

Factors Affecting Production (1981)

Plants, like all living beings, need energy to grow and develop. This energy reaches them from the external environment in various forms: in the form of electromagnetic energy (solar radiation); in the form of mechanical energy (ploughing); in the form of chemical energy (fertilization), and so on (Govindjee, Levit, Beevers, Gibbs, Gaastra). For this energy reaching the plant to have an effect, it must comply with the criteria regarding quantity, quality, and time.

For example, abundant water is necessary during vegetative growth (quantitative aspect); the photosynthetic process requires specific light wavelengths (qualitative aspect); low temperatures during wheat flowering are harmful, while they are welcome in the period following sowing (temporal aspect) (Tombesi, VanWiijy, Coste, Calcaterra).

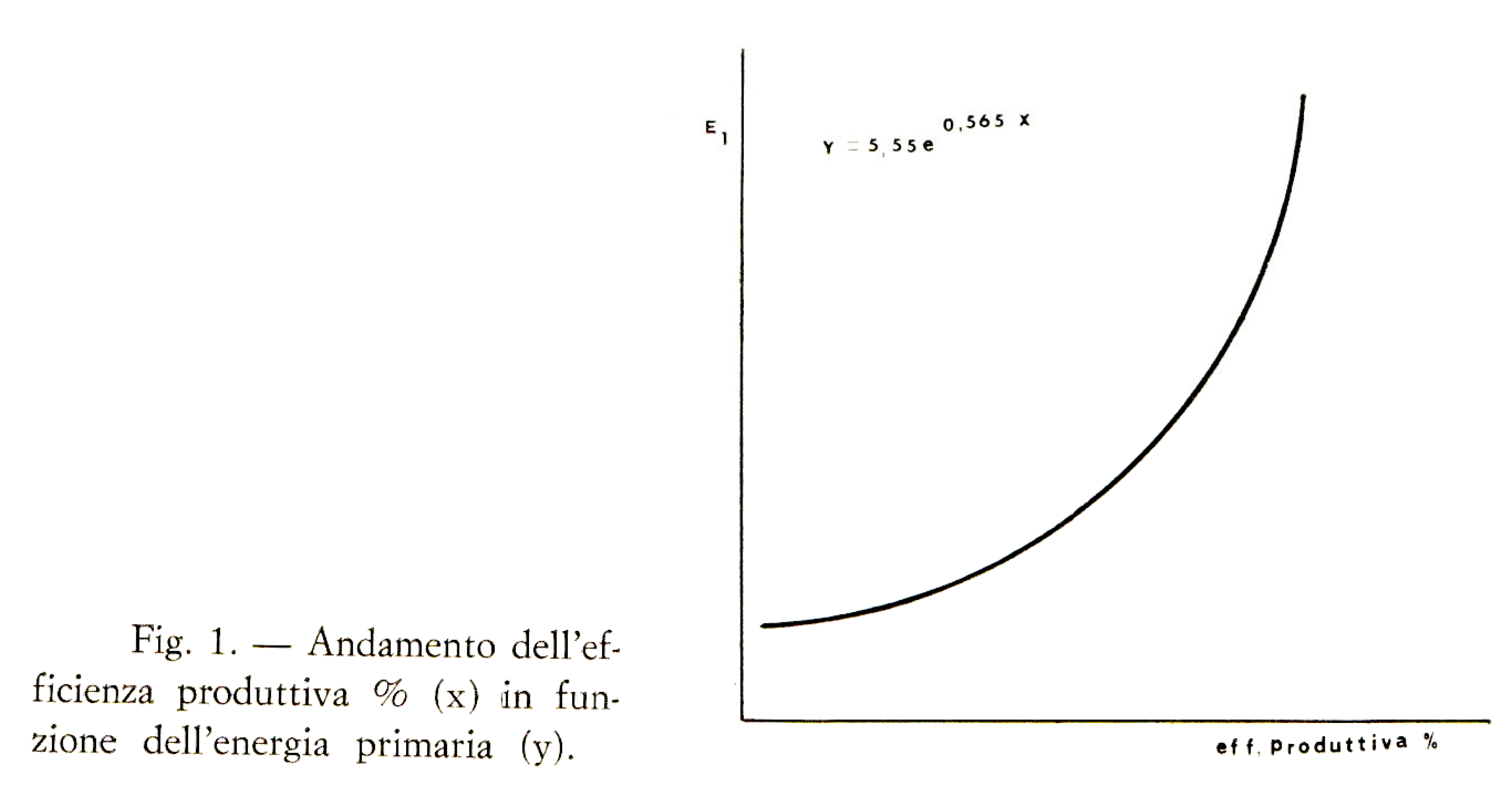

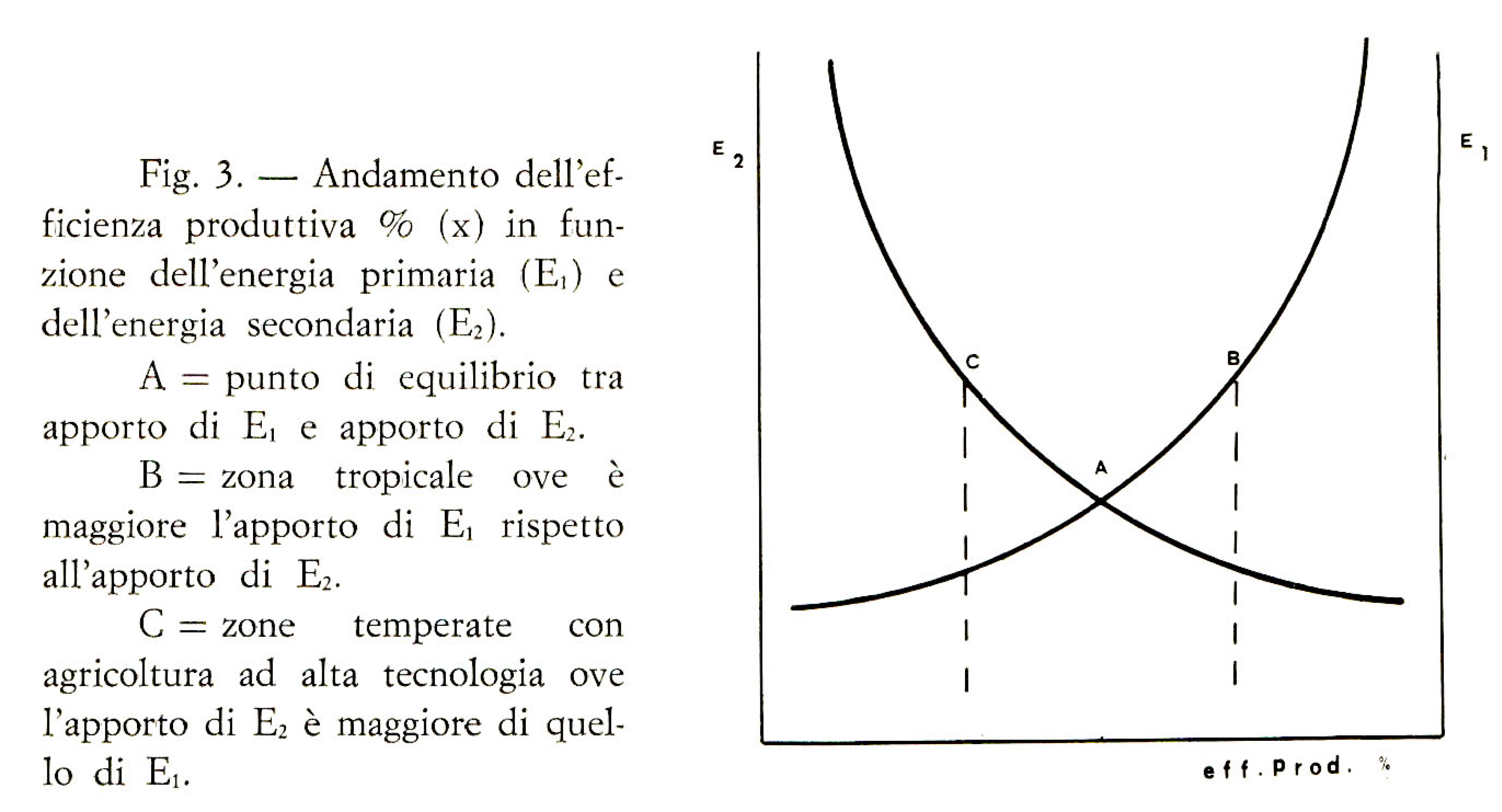

The energy reaching the plant consists of primary energy (E1) and secondary energy (E2), the sum of which constitutes the Environmental Energy Pool (EEP) (Nicastro-Tachella).

Primary energy (E1) consists of all those factors that, due to their very nature, have an energy content that can be directly utilized by the organism; for example, solar radiation acts directly on the photosynthetic process; temperature acts on thermal exchanges and respiration processes; wind acts on vapor pressure and thus evapotranspiration, etc.

Secondary energy (E2) consists of all those factors that contain energy in a potential form. This energy, depending on the action exerted upon it by the primary energy, can fully or partially express its potential. For example, the distribution of 100 mm of water over one hectare, which is equivalent to an energy input of 16 x 105 Kcal., will result in different yields depending on whether climatic conditions allow the plant a greater or lesser utilization of the water administered.

Secondary energy therefore includes both the means to increase and enhance plant yield, such as irrigation, fertilizers, herbicides, etc., and those capable of substituting for human energy input, such as machinery.

The ratio between the quantity of energy effectively accumulated by the plants (i.e., the organic matter produced) and the quantity of primary or secondary energy employed is expressed by the term “productive efficiency” of a plant.

The Current Landscape (2025): Productive Efficiency in the Era of AI and Climate

The 1981 model, which conceptually splits total energy (PEA) into Primary Energy (E1) (direct climatic factors) and Secondary Energy (E2) (potential inputs like water, fertilizers, and machinery), provides a conceptual foundation that is now more critical than ever. The comparison highlights a severe destabilization in the management of E1 and a radical innovation in the control of E2.

1. Primary Energy (E1): The Climate Threat

In 1981, E1 was viewed as an environmental variable to be respected (quantity, quality, time). Today, E1 has become a profoundly destabilized variable.

Increased Risk and Damage: Climate change has degraded the quality and predictability of E1 in the tropics, particularly temperature and water availability. Research indicates that rising global temperatures will reduce global crop yields by approximately 8% by 2050 [

28]. The greatest impact is concentrated in low-income and tropical regions, where climate risks (extreme heat, drought, floods) threaten to push agricultural production outside its safe climatic operating zone [

29].

Reduced Efficiency: The unpredictable variation in temperature and rainfall regimes destroys the temporal synchronization (E1 - temporal aspect) between available energy and the plant’s life cycle (as the 1981 model anticipated), thus reducing productive efficiency. Furthermore, unfavorable E1 (heat) fuels pests, diseases, and weed infestations, which consume the organic matter produced by the plant.

2. Secondary Energy (E2): The Impact of Artificial Intelligence

The management of E2 (irrigation, fertilizers, machinery) has transitioned from experience-based optimization to “Algorithmic Precision” thanks to AgriTech:

Maximized Efficiency: Artificial Intelligence (AI) and IoT (Internet of Things) systems, powered by drones and remote sensing, have revolutionized the use of inputs. These systems enable Variable Rate Fertilization and Smart Irrigation, optimizing the application of fertilizers and water (the E2 factors) for specific sections of a field [

30]. AI analyzes real-time data to ensure that E2 adheres to the criteria of quantity and time (as required by the 1981 model) with unprecedented accuracy.

Energy Efficiency: AI not only increases the effectiveness of inputs but also reduces their overall quantity, leading to a marked improvement in productive efficiency (the ratio between accumulated energy and the employed E1 + E2). This precision cuts fertilizer and pesticide waste, potentially reducing operational costs by up to 25% and mitigating environmental impact, yet adoption remains limited among small tropical farms due to pervasive infrastructural issues [

31].

While in 1981, productive efficiency was primarily constrained by the scarcity of E2 (costly machinery and lack of fertilizer), today it is limited by the volatility of E1 (unpredictable climate) and the lack of access to the AI and capital needed to precisely manage E2. The contemporary challenge is to translate the new technological capabilities in E2 management into accessible and resilient tools that can effectively mitigate the growing instability of E1.

Concluding Reflection on Productive Efficiency

In summary, the transition from 1981 to 2025 reveals a paradox of regression: despite revolutionary technological advancements in controlling Secondary Energy (E2), the mounting instability of Primary Energy (E1) due to climate change has not only nullified these gains but arguably accelerated the decline in overall productive efficiency in tropical agriculture.

This outcome underscores the prescience of the original 1981 framework - the systematic breakdown of energy into E1 and E2 provided a clear and early roadmap, suggesting that a timely focus on stabilizing E1 (climate and land health) and ensuring equitable access to E2 resources could have pre-emptively safeguarded the region against the interconnected crises now faced.

Empirical Findings: Low Productive Efficiency Driven by E1 and Climatic Limits (1981)

From tests carried out with various plants in a climatic chamber, in lysimetric tanks, and in the field, of which only some results are reported due to the homogeneity of the trends, it emerges that:

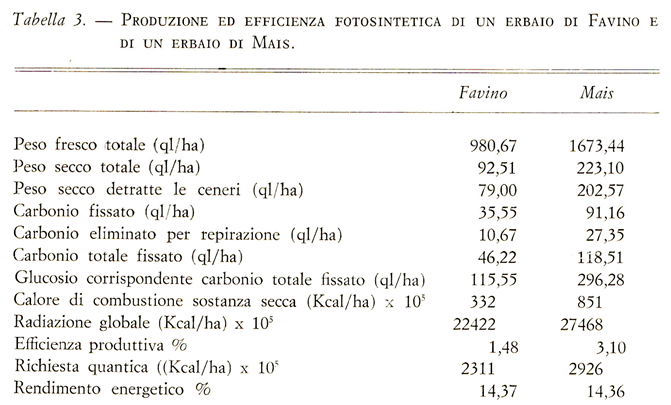

In a controlled environment and under optimal conditions regarding fertilization and water availability, the productive efficiency due to primary energy (E1) exhibits values ranging between 1.48% and 3.10% (

Table 3).

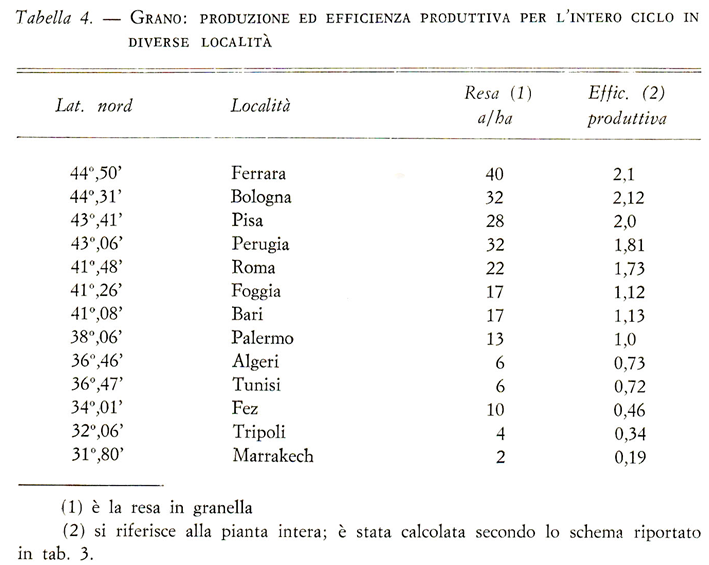

In the field, the productive efficiency due to primary energy (E1) exhibits values oscillating between the 0.19% of Marrakech - where environmental conditions are adverse, especially due to precarious water conditions - and the 2.1% of Ferrara (

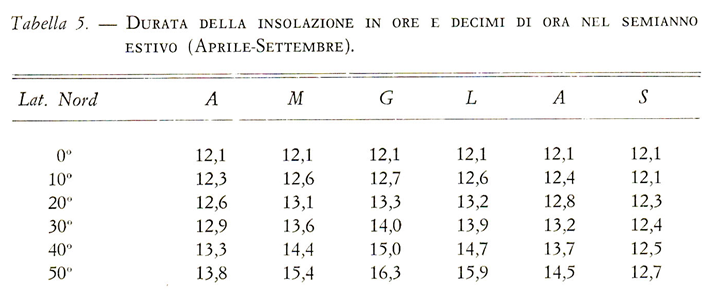

Table 4). In this regard, it should be noted that the increase in solar radiation is a function of latitude during the summer half-year. To avoid misunderstandings, it should be remembered that during the summer half-year (April - September), the period in which vegetation in temperate zones is in full vegetative vigor, the hours of daylight are greater than those recorded at the equator (

Table 5).

Consequently, vegetation in temperate zones, although utilizing lower radiation intensity due to the angle of the sun’s rays, receives a greater total quantity of energy than plants cultivated in the tropics during the summer half-year.

Furthermore, in temperate zones, the presence of milder temperatures ensures that the photosynthesis-to-respiration ratio is high, and consequently, production is also high; in tropical zones, conversely, high temperatures lower this ratio, resulting in low production (

Table 5).

From what has been exposed so far, it can be stated that the plant’s productive efficiency due to primary energy (E1) is rather low.

As primary energy (E1) increases, the plant’s productive efficiency increases up to a certain point, beyond which it halts (

Figure 1). This halt is due to the fact that the other production factors are unable, beyond a certain point, to satisfy the plant’s needs, which increase as the energy flow increases.

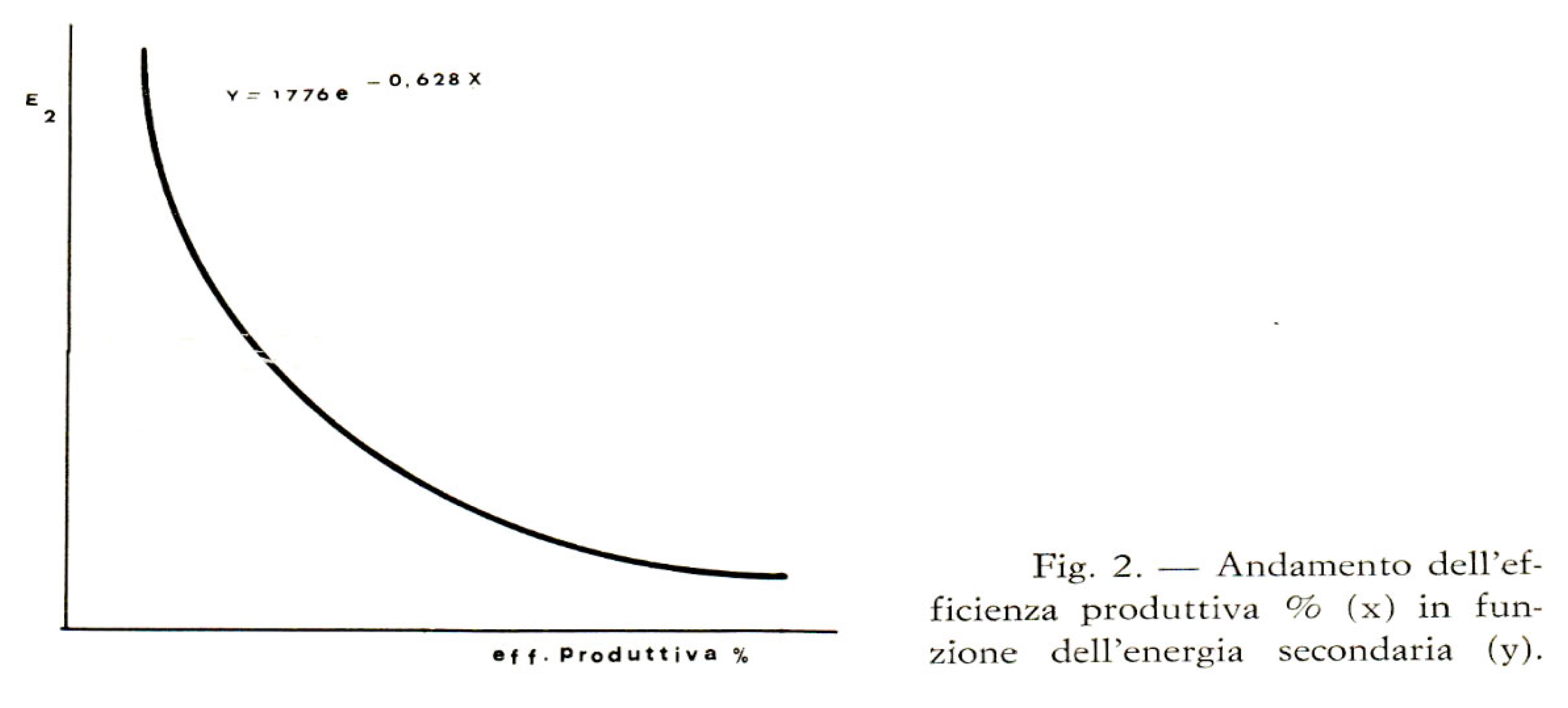

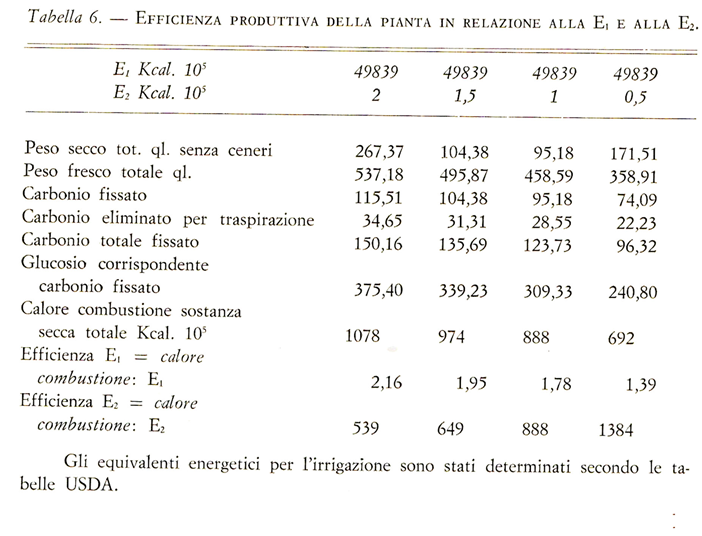

Moving now to analyze productive efficiency as a function of secondary energy (E2), we observe:

1) Productive efficiency is far superior to that obtained when only primary energy is supplied (

Table 6).

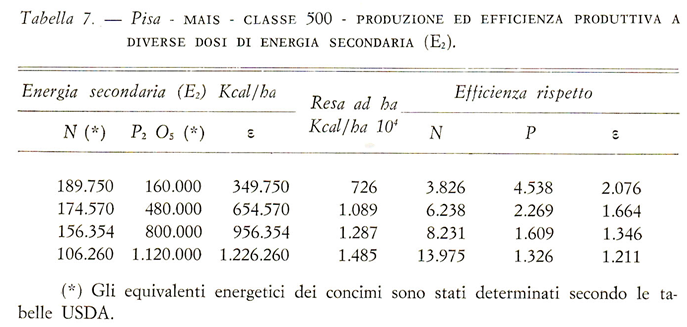

2) The supply of secondary energy leads to sharp increases in production (

Table 7).

3) Productive efficiency decreases as the doses of secondary energy increase (

Table 6 and

Table 7).

That is, there is an inverse relationship between the supply of secondary energy and the plant’s productive efficiency, which can be summarized, in the case of maize, by the graph illustrated in

Figure 2.

2025. Comparative Analysis: Validating E1 Limitations and Maximizing E2 (The Algorithmic Approach)

The empirical observations presented in the 1981 paper regarding the low efficiency of Primary Energy (E1) and the diminishing returns of Secondary Energy (E2) remain fundamentally valid. However, the climate crisis and the advent of AgriTech have drastically changed the scale of these factors and the methods used to counteract them.

1. The E1 Constraint (Climate): A Vicious Cycle Confirmed

The 1981 finding that high tropical temperatures lower the photosynthesis-to-respiration ratio, thereby reducing yields, is now a central challenge in global food security.

Validation through Physiology: Modern research confirms that under moderate heat stress, the plant’s maintenance respiration significantly increases, consuming carbon energy that should be allocated to growth and yield production [

32,

33]. The problem identified in 1981 - the low efficiency of E1 in the tropics - is therefore rooted in a fundamental thermodynamic constraint on crop physiology.

Worsening Conditions: The 2025 climate reality has intensified this E1 problem. With rising global average temperatures and more frequent extreme heat events, the yield-damaging effects of the unfavorable photosynthesis-respiration ratio are no longer marginal; they are predicted to cause substantial yield losses (

e.g., 40% loss projected for rice over the next century) [

34]. The low E1 efficiency observed in Marrakesh in 1981 is now the expected norm for vast tropical areas.

2. Overcoming E1 Limits: The Genetic Response

The modern scientific focus is on mitigating the E1constraint not merely through irrigation (E2), but by genetically modifying the plant itself to improve its thermal tolerance.

Genetic Resilience: Gene editing technologies, such as CRISPR/Cas9, are being used to enhance crop resilience against heat and drought. By precisely manipulating stress-response genes (like HSP or DREB), scientists aim to stabilize the thermal sensitivity of enzymes crucial for photosynthesis, effectively raising the temperature threshold at which the detrimental rise in respiration occurs [

35,

36]. This approach is an attempt to create a “built-in” E2 factor by improving the plant’s capacity to utilize E1 efficiently, even under sub-optimal conditions.

3. The E2 Constraint: Mitigating Diminishing Returns

The 1981 paper noted an inverse proportionality between the increasing supply of Secondary Energy (E2) and productive efficiency—the classic law of diminishing returns.

The AI Solution: In 2025, Precision Agriculture driven by AI and data analytics serves as the primary tool to overcome, or at least significantly postpone, this point of diminishing returns. By using sensors and predictive models, AI systems now enable Variable Rate Application (VRA), applying fertilizers, water, and pesticides only where and when they are needed, with up to 30% reduction in input use [

37,

38].

Maximizing Efficiency: This technological precision ensures that every unit of E2 input is utilized at the point of maximum yield response. In economic terms, AI maximizes the financial return before the marginal benefit of an input falls below its marginal cost, effectively making the application of E2 inputs far more efficient than the “blanket” applications that resulted in the inverse proportionality observed in 1981.

The empirical constraints of Primary Energy (E1) identified in 1981 - specifically the detrimental effect of high temperatures on the photosynthesis-respiration ratio - have been dramatically amplified by climate change; consequently, the primary goal of modern AgriTech is now to utilize the algorithmic precision of Secondary Energy (E2) inputs, not merely for maximizing yield, but for genetically and precisely mitigating the thermodynamic limits imposed by a hostile and increasingly volatile E1.

While acknowledging the ongoing, critical debate regarding the principal drivers of contemporary global warming, this analysis intentionally focuses on the severe empirical consequences of observed temperature increases, regardless of their origin. History is replete with examples of massive, naturally-driven climatic shifts - such as the rapid aridification of the Sahara around 4,000 BCE due to orbital changes - which prove that significant and destructive changes to Primary Energy (E1) are not exclusively anthropogenic. Our central argument therefore remains that the agricultural system’s fundamental lack of resilience, identified in 1981, is the core failure, exacerbated by, rather than solely dependent on, the source of current warming.

Interpretation of the Results Obtained (1981)

Let us compare, by superimposing the graphs, the trend of productive efficiency as a function of primary energy and secondary energy (

Figure 3).

The two curves intersect at a point A, which we call the “point of equilibrium,” as the plant’s productive efficiency is the result of a correct balance or proportion between the inputs of primary and secondary energy. In practical terms, unfortunately, the situation differs from what has been stated; in fact, in tropical zones, there is a tendency to shift to the right of point A, for example, to B. That is, prevalence is given to primary energy over secondary energy because the latter is the most costly.

This therefore results in scarce production; the only possibility of increasing production in tropical countries is thus to intervene with the supply of secondary energy. This, in the first place, must be represented by irrigation, both because it is the main deficient factor and because it is the one that regulates the biological functions of the plants, and simultaneously by fertilization, productive seeds of local origin, mechanization, etc.

Conversely, in temperate zones, the use of secondary energy predominates, even if it is costly. This results in high production, even though, ultimately, the plant’s productive efficiency turns out to be low. On the other hand, it should not be forgotten that developed countries have an advantage over developing countries because they themselves are producers of secondary energy (fertilizers, machinery, etc.).

2025. Comparative Analysis: The Erosion of the “Equilibrium Point” (A) by Geopolitics

The 1981 paper correctly identified that tropical countries were forced to operate away from the optimal “Point of Equilibrium” (A) - where E1 (Primary Energy/Climate) and E2 (Secondary Energy/Inputs) are balanced - due to the cost of E2 inputs (fertilizers, machinery, irrigation).

Forty years later, this fundamental economic constraint has not been resolved; instead, it has been amplified and made critically volatile by global instability, supply chain fragility, and the entrenched dependency on developed nations for E2.

1. Amplification of the E2 Cost Constraint

While new AgriTech (AI, precision farming) theoretically promises to make every unit of E2 more efficient (ideally shifting Point A higher), the global economic reality has made essential E2 factors (like fertilizers) more costly and geopolitically risky, forcing many tropical farmers to remain at Point B or even regress.

Geopolitical Volatility: Unlike in 1981, when cost was primarily defined by internal economic factors, today’s E2 costs are dictated by geopolitics. Nitrogen-based fertilizers (urea, DAP) depend heavily on natural gas for production and on exports from a few key countries (Russia, China, Morocco). Crises like the Russia-Ukraine conflict have triggered unprecedented price spikes for fertilizers and logistics, often making them unreachable for farmers in low- and middle-income countries [

39,

40].

Worsening Affordability: In 2025, fertilizer accessibility has significantly worsened: while the cost of E2 factors increases (the price of phosphates rose by 36% in less than eight months in 2025), the prices of many basic food crops have declined [

41]. This disparity means the farmer’s return on investment for E2 is often negative, reaffirming the decision to operate at the inefficient Point B (relying on cheap E1 but risking low production).

2. The Persistence of Production Dependency

The 1981 insight that developed nations benefit from being E2 producers remains critically true, but the nature of dependency has evolved from machinery to advanced, patented genetics and complex supply chains.

From Machinery to Data: If developed nations once held a monopoly on tractors and chemical factories, today they control the intellectual property of high-yield seeds, sophisticated AI/IoT systems, and specialized farm inputs. This means that while some E2 (such as irrigation systems) can be decentralized, access to the most effective solutions for dealing with E1 stress (like heat-tolerant seeds) often remains a luxury controlled by developed countries [

35].

Structural Disadvantage: Dependency is no longer just a matter of price, but of systemic vulnerability. Port delays, trade barriers, and environmental regulations imposed by developed countries (

e.g., the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism) add burdens and compliance costs that disadvantage emerging market supply chains, making the procurement of E2 slower and less reliable [

42].

The “Punto di Equilibrio” (A) is now less a static theoretical maximum and more a moving target that is constantly destabilized by two opposing forces: the technological advancement (AI) that pulls it toward greater efficiency, and geopolitical volatility that pushes the cost of inputs (E2) further out of reach, thus magnifying the original socioeconomic barrier identified in 1981.

Ultimately, despite monumental global spending and technological leaps, the fundamental economic barrier - the high and now highly volatile cost of E2 inputs - has been severely aggravated by geopolitical fragility and infrastructure deficits, leading to the conclusion that, in this critical aspect, the agricultural situation in the tropics is functionally worse than in 1981, highlighting the broad failure of implementation mechanisms over the past four decades.

The resulting synthesis reveals a structurally discouraging paradox. The 1981 framework offered a profoundly prescient diagnosis, identifying agricultural efficiency as fundamentally limited by a precarious equilibrium between uncontrollable Primary Energy (E1) and the cost/accessibility of Secondary Energy (E2).

Today, the paradox is exacerbated: while revolutionary technological tools (AI, genetics, precision irrigation) exist to address the E2 challenge with unprecedented precision, the core socioeconomic and political barriers have not only persisted but have intensified.

Decades of development aid and investment have been systematically nullified, as geopolitical volatility and environmental instability have made critical E2 inputs more expensive and less reliable. This suggests that the failure is not technical but systemic, rooted in political, economic, and implementation deficits.

However, this rigorous and critical assessment serves as a crucial diagnosis, dictating that future policy and investment agendas must shift their focus from merely increasing production to the algorithmic construction of resilience and the definitive uncoupling from geopolitical dependency.

Conclusions

E2 as a Driver of Prosperity: Production, Animal Proteins and Demographics (1981)

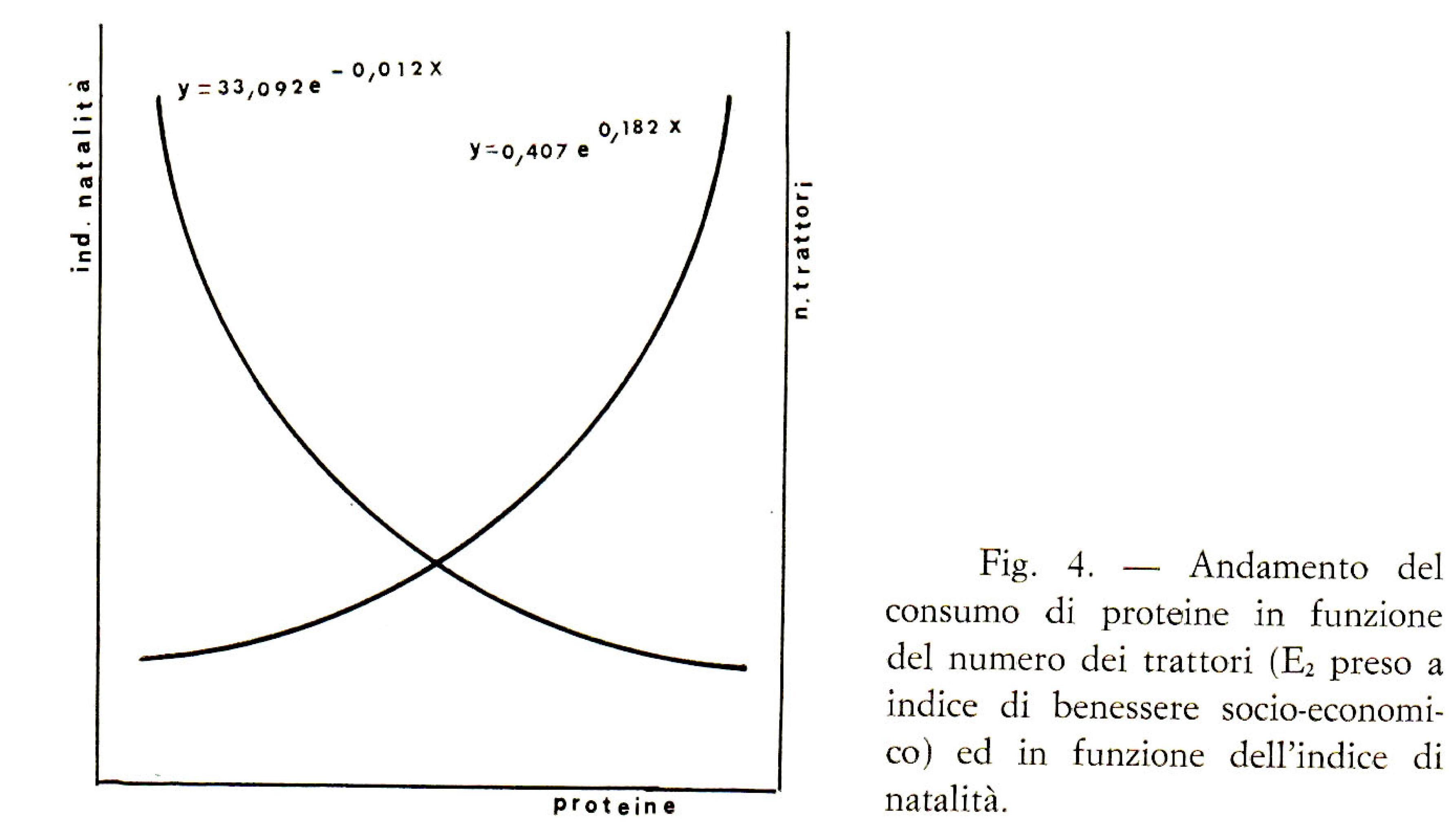

We have stated that the use of secondary energy leads to an increase in production, as occurs in industrialized countries. In these countries, the surplus agricultural products are then utilized for animal feed, which allows for livestock assets that enable a richer and thus more balanced diet.

In tropical countries, however, where agricultural production is still linked almost exclusively to the use of primary energy, there is a production deficit that only allows for a diet composed almost exclusively of cereals and very poor in animal protein.

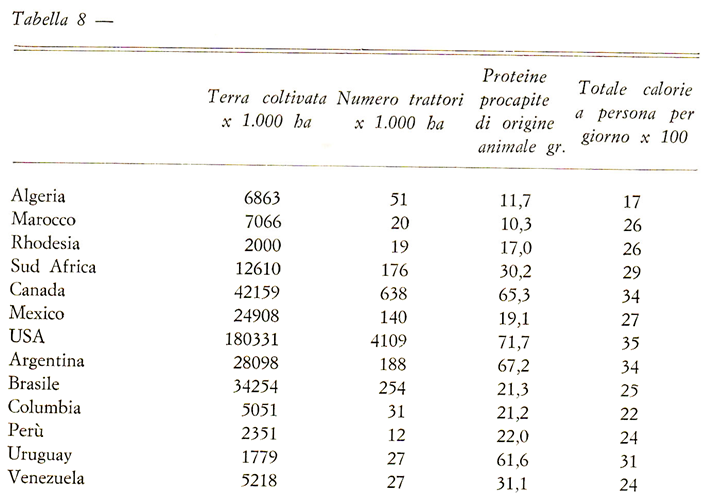

For a better illustration of the above, we compare data relating to the use of secondary energy - expressed in this case as tractors, an index of socioeconomic prosperity - with the consumption of animal-source protein (

Table 8).

As can be seen from

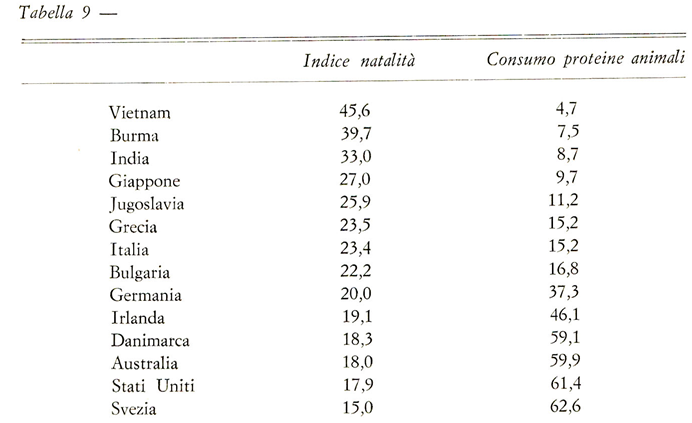

Figure 4, in areas where secondary energy is employed, the consumption of animal-source protein increases, and, interestingly,

Figure 4 and

Table 9 also reveal that an increase in the consumption of animal protein corresponds to a decrease in the birth rate. (The latter finding would require more in-depth study).

Figure 5.

Title page of the original 1981 paper.

Figure 5.

Title page of the original 1981 paper.

The input of secondary energy, represented by possibilities for irrigation, fertilization, and the use of machinery that substitutes agricultural machinery for human labor, thus represents a condition of social well-being that leads to better living and health conditions.

The continuous and increasing gap in tropical countries between the rapid increase in population and the slow increase in food production is the primary cause of all the problems afflicting these countries.

To solve them, there is no option but to implement medium- and long-term plans that inevitably require large capital investments, for which the total commitment of the international community is necessary. Indeed, the price to pay to solve world hunger must fall on everyone (Resolution of the World Food Conference – Rome – 1974).

The most important plan to be implemented, however, is to use the secondary energy discussed in the best possible way to increase the food production efficiency of these countries.

2025. Comparative Analysis: E2, Protein, and the Collapse of the Development Mission

The 1981 paragraph established a clear chain of causality: E2 (Tractors) - Agricultural Surplus - Animal Protein - Social Well-being - Reduced Birth Rate. This framework forms the basis of the Demographic Transition Theory, which, by 2025, has been largely validated, but the primary driver (E2) has undergone a profound transformation.

1. The New Measure of E2: From Tractors to Data

The “tractor” in 1981 served as a tangible indicator of E2 availability and socioeconomic prosperity [

43]. In 2025, this metric is functionally obsolete.

Tractor vs. Connectivity: Tropical agricultural prosperity is no longer solely measured by physical mechanization but by connectivity and access to data. The new E2 measure is the adoption of Climate-Smart Agricultural Technologies (CSATs), such as IoT sensors for precision irrigation, adaptive genetics, and digital extension services [

44]. These new E2 factors are key to increasing climatic resilience and targeted productivity, but adoption in Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) is hindered by critical infrastructural limits: lack of electricity, mobile connectivity, and digital literacy [

45].

Demographic Confirmation: The correlation hypothesized in 1981 between the adoption of agricultural technology (particularly mechanization) and the reduction in the fertility rate has been confirmed by subsequent studies [

46]. The use of machinery replaces intensive manual labor (reducing the need for family labor), and income gains derived from E2 are often reinvested in education and health, thereby accelerating the demographic transition toward lower birth rates [

47].

2. The Population-Food Gap and Protein Deficiency

The gap between population growth and the slow increase in food production, identified as the “primary cause of all problems” in 1981, has narrowed slightly, but the nutritional crisis (protein deficiency) has worsened.

Uneven Progress: Global hunger has slightly declined globally since 2022, but this masks critical worsening trends in the majority of sub-regions of Africa and Western Asia [

48]. Progress has been insufficient, leaving the Zero Hunger Goal (SDG 2) out of reach for 2030, with over 600 million people projected to still be facing hunger by that year [

49].

The Protein and Livestock Crisis: While the 1981 model pointed to a cereal surplus used for livestock as the path to an animal protein-rich diet, this model is now environmentally unsustainable on a large scale. Malnutrition in 2025 is not just a caloric deficit but a more complex nutritional deficiency, with rising adult obesity rates (due to poor, unbalanced diets) coexisting with childhood stunting [

50]. Access to quality nutrition remains the core issue.

3. The Total International Commitment (1974–2025)

The 1981 work concluded with an appeal for the “total commitment of the international community,” echoing the Resolution of the 1974 World Food Conference in Rome.

Commitment Upheld? The 2025 analysis reveals that this commitment has been substantially broken. Despite the creation of ambitious goals (the Sustainable Development Goals - SDGs), progress has stalled significantly since 2016 [

51].

Inversion of Priorities: The most severe element is the inversion of funding priorities. Budgets for humanitarian and development assistance (crucial for E2 implementation in developing countries) have drastically decreased, while global military spending has increased. This inversion of the “price to pay to solve world hunger” highlights a profound political disconnect between the verbal commitments and the concrete actions of international donors, directly undermining the long-term plan proposed in 1981 [

51].

Final Analytical Reflection

The 45-Year Balance Sheet: Progress, Regression, and Stagnation

The comparative analysis reveals a bifurcated legacy over the past 45 years. Progress is evident primarily in quantitative metrics: there has been a dramatic reduction in global chronic hunger (though not food insecurity), immense decreases in infant mortality rates, and revolutionary advances in agricultural technology (AgriTech, AI-driven E2 management, and gene editing).

However, these gains mask significant regression and stagnation. The situation is functionally worse in core structural areas: the cost and geopolitical volatility of E2 inputs (fertilizers, energy) are higher; land degradation and genetic uniformity have intensified, transforming local vulnerabilities into global threats; and the detrimental impact of E2 instability (climate change) has nullified technological yields. The structural lack of reliable rural infrastructure and equitable market access remains largely stagnant, transferring the “too costly” barrier of 1981 into the “digital divide” of 2025.

The Reasons for Systemic Failure

The failure to translate massive spending and technical innovation into sustained, equitable food security is hypothesized to stem from a foundational misalignment of priorities. As noted by the 1981 framework, the problem was never primarily technical, but political and economic. The systemic regression is driven by the consistent prioritization of short-term economic output and market-driven monoculture over essential long-term investments in ecosystem health and governance reform.

Global aid and development policies have frequently reinforced the high-input paradigm that exacerbates the very problems identified in the original paper - soil exploitation and dependency. The final and most critical failure is the substantially broken commitment of the international community (the 1974 mandate), evidenced by the massive spending inversion away from development and towards military expenditure, undermining the necessary systemic support required to build resilience against external shocks.

A Proposal for Structural and Algorithmic Solutions: Lessons Unlearned?

To reverse this trajectory, the focus must shift from merely increasing agricultural production capacity to the algorithmic construction of resilience. Future policies must adopt a dual strategy: first, addressing structural impediments by mandating coordinated international investment in rural energy grids, connectivity, and local cold chains to effectively democratize access to E2 technologies. Second, promoting a Resilience-First Agronomy that leverages the precision of AI and gene editing to solve the thermodynamic limits imposed by hostile E1. This requires shifting investment toward local genetic preservation, biofortification, and the development of decentralized, low-input E2 solutions.

Ultimately, the only way to successfully implement the long-term plan proposed in 1981 is by recognizing that solving world hunger is not a production problem but a governance and equitable access problem, requiring a renewed, binding international commitment.

The authors of the 1981 paper were not heeded then; the critical question now remains whether, given the compounded crises of 2025, this new diagnosis will finally compel the necessary systemic change, even if past experience offers little basis for optimism.