1. Introduction

Suicide represents one of the most significant public health challenges and remains a highly complex issue in psychiatric practice. According to the World Health Organization, more than 700.000 deaths by suicide occur worldwide each year, and approximately one in every 100 deaths is because of suicide, making it one of the leading causes of death [

1]. Young adults are the ones more at risk: suicide has been identified as the second leading cause of death amongst individuals between the ages of 15–29 [

1]. Notably, patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) represent a high-risk population, with a relative risk of suicide between 12 and 20 times higher than in the general population [

2]. In Europe, the current overall prevalence of MDD is 6.38% [

3], and about 31% of these patients have experienced lifetime suicidal ideation (SI) [

4]. MDD patients with active SI have a 21-fold higher risk of committing suicide [

5], and those with more severe SI (i.e., intent with a plan) are at greater risk of attempted or completed suicide [

6]. SI should always be investigated in the context of MDD, since patients with SI show more severe depressive symptoms [

7] and worse response to treatment [

8] compared to patients without SI. Lastly, it is important to notice that patients with active SI or previous lifetime suicide attempts are less likely to improve and obtain remission with conventional antidepressants [

9].

Considering this background, patients experiencing SI require prompt and comprehensive intervention to prevent self-harm [

10]. The standard of care involves treatment with antidepressants, and in the most severe cases, hospitalization may be required [

11]. Traditional antidepressants were known to have some degree of anti-suicidal effects, but the lack of rapid onset (about 4–6 weeks) limits their use for acute suicidal crises. Therefore, fast-acting antidepressants that specifically and rapidly reduce suicidal risk are needed for patients with severe MDD [

12].

In 2019, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved intranasal Esketamine as an adjunctive treatment to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) for adults with TRD who have failed to respond adequately to at least two oral antidepressants. This approval remains strictly as a combination therapy, so Esketamine in monotherapy is not authorized in Europe. In 2020, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Esketamine also for the treatment of depressive symptoms in adults with MDD with acute suicidal ideation or behavior in combination with an oral antidepressant.

The rapid effect of Esketamine on SI has been reported both in registration trials and “real-world” studies, where the acute effect in reducing suicidality has been assessed [

13]. Real-world data on the effectiveness of Esketamine were collected and analyzed by the REAL-ESK group: the Authors run a multicenter and retrospective study on a real-world cohort (n=116) of patients with TRD treated with intranasal Esketamine. Depressive symptom severity, measured using the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), declined significantly at 1 and 3 months; moreover, two-thirds of the patients achieved a clinical response, and about 40% reached remission at 3 months [

14]. ASPIRE I and ASPIRE II were registrative, multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 3 trials designed to assess the rapid antidepressant and antisuicidal effect of intranasal Esketamine (84 mg twice weekly for 4 weeks) in adults (18–64 years) with MDD and active SI with intent. Following a 24–48-hour screening period, patients were randomized 1:1 to Esketamine or placebo, each administered alongside standard-of-care (i.e., initial hospitalization≥ 5 days plus initiation or optimization of an oral antidepressant). The primary endpoint was the change in MADRS score 24 hours after the first dose; a key secondary endpoint was the change in suicidality as measured by the Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Suicidality-revised score (CGI-SS-r). These studies showed an improvement in MADRS total score in patients treated with Esketamine vs placebo at 24 hours from the first administration. The same positive effect was also noted at the 4-hour time point. By contrast, between-group differences on the CGI-SS-r were not statistically significant, although suicidality was reduced in both arms [

15,

16].

Moreover, a meta-analysis of 9 randomized controlled trials (number of patients = 197) confirmed the rapid effect of Esketamine on suicidality after only one administration, showing a significant reduction of SI at 2, 4, and 24 hours after the start of the treatment [

17]. Despite the acute effect of intranasal Esketamine of SI has been extensively reported, limited data are currently available regarding the maintenance of this effect [

18]. In a recent study that included 209 patients with TRD, the reduction in SI has been reported to persist for up to seven days following the last administration [

18], however, no study has yet investigated if this beneficial effect lasts after treatment discontinuation.

Since intranasal Esketamine was only recently approved, real-world data on its efficacy for SI remains scarce, and little is known about which patients are most likely to benefit. This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of intranasal Esketamine in reducing SI in a clinical sample of patients with TRD, treated according to the standard of care. A methodological strength of the present study is the use of the C-SSRS instead of a more subjective clinician-global measure, such as the CGI-SS-r, employed in the ASPIRE I and II studies. Using C-SSRS, we aimed to enhance sensitivity to short-interval change, reducing measurement bias, improving reproducibility, and modelling trajectory over time. Clinical response - both SI and depressive symptoms - will be examined in the short and long term, with assessments conducted immediately after the first week of administration and across subsequent follow-up times. Lastly, potential predictors of clinical response will be analyzed. We hypothesized that adjunctive intranasal Esketamine could rapidly reduce SI and guarantee a sustained anti-suicidal effect during maintenance and could alleviate core depressive symptoms in parallel.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients’ Recruitment and Assessment

Adult patients (aged ≥18 years) were recruited from February 2021 to March 2025 in two Italian outpatient clinics: the ASST Fatebenefratelli-Sacco in Milan and the IRCSS Policlinico San Matteo in Pavia. Patients were included if they were suitable for a trial with intranasal Esketamine, according to clinical judgment: patients had to manifest a current moderate to severe major depressive episode (according to DSM-5-TR criteria [

19]) in the context of TRD (defined as an inadequate response to at least two antidepressants at adequate dosage, duration, and adherence). Prescription happened in line with the inclusion and exclusion criteria as per the summary of product characteristics. Clinical evaluations and psychometric assessments were conducted at different time points: baseline (T0), one week (T1), one month (T2), two months (T3), three months (T4), and six months (T5). The C-SSRS is a clinician-administered scale designed to quantify the full spectrum of SI severity and related behaviors [

20]. The first 5 items assess the severity of suicidality, ranging from a passive wish to be dead (1 point) to active suicidal ideation with a specific plan (5 points). These items are followed by additional items addressing preparatory behaviors and actual, interrupted, or aborted attempts. In the present study, SI severity was assessed using the C-SSRS, specifically using the sum of items 1 to 5. We decided to consider only items from 1 to 5 for the following reasons: 1) the primary outcome was the intensity of SI rather than lifetime manifestation of suicidal behavior; 2) these five items are the instrument’s core, standardized severity metric with validated points that support reliable between- and within-person comparisons [

21,

22]; 3) by limiting administration to the ideation subscale, we reduced participant burden and optimized assessment time within a broader battery of measures. Finally, the administration of C-SSRS to assess suicidality is supported by other reliable studies: the studies by Greist et al. and Lindh et al. are two well-characterized and large studies that used the C-SSRS to evaluate and predict suicidality in clinical populations [

21,

23]. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the MADRS scale. The MADRS is a reliable and widely used ten-item clinician-rated scale designed to measure the severity, on a scale from 0 to 60, of depressive episodes in patients with mood disorders [

24].

At baseline, socio-demographic data, clinical data, pharmacological data, and anamnesis were collected. At each time point, the C-SSRS and MADRS were administered by a resident psychiatrist to assess suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms. Psychometric scales were administered at each time point, not necessarily by the same operator, and to minimize inter-rater variability, all raters were experts in the diagnosis and treatment of depressive disorders and received standardized training in scale administration.

To evaluate the treatment’s effect on SI, a patient was considered a responder if they showed either a reduction of at least 50% in the C-SSRS score from baseline (T0) or a score of 0 at any follow-up time point. To assess the treatment’s effect on depressive symptoms, a patient was considered a responder if they showed a reduction of at least 50% in the MADRS. Moreover, a patient was classified as an early responder if they met the response criteria at the C-SSRS by T1. Time to response was defined as the first time point at which the response criteria were met.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Statistics (means, standard deviations, and frequencies) were run for initial data analysis. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 27). Correlations between C-SSRS and MADRS scores were evaluated using the Pearson correlation coefficient at each time point. Longitudinal changes in C-SSRS scores were analyzed using mixed-effects linear models. Fixed effects included time, baseline C-SSRS and MADRS scores, mean Esketamine dose, and gender. Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify predictors of early response, using baseline demographic and clinical variables as independent predictors. Statistical significance was set as p < .05.

3. Results

The study cohort (N=80) had a mean age of 49.1 ± 16.8 years; 55% were women and 45% were men. Concerning marital status, 58.8% of patients were partnered and 41.2% were single. 46.2% of patients were unemployed, 53.8% employed. Clinically, 84% of the sample were experiencing a MDE in the context of MDD, whereas 16% had a primary diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder. The mean age at the onset was 31.5 ± 15.5 years, and patients had experienced 4.8 ± 5.9 number of MDEs in their lifetime. The current episode had lasted a mean of 241 ± 194 days. The mean lifetime number of suicide attempts was 0.4 ± 0.8, and 70% of patients reported a positive family history of depression or suicidal behavior. Regarding psychopharmacological treatment, 60% of patients were receiving SSRIs, 40% SNRIs, and 43.8% other classes of antidepressants. In addition, 52.5% were treated with atypical antipsychotics (APs), 38.8% with mood stabilizers (MSs), and 56.2% with benzodiazepines (BDZs).

Table 1 shows sociodemographic and clinical variables of the sample.

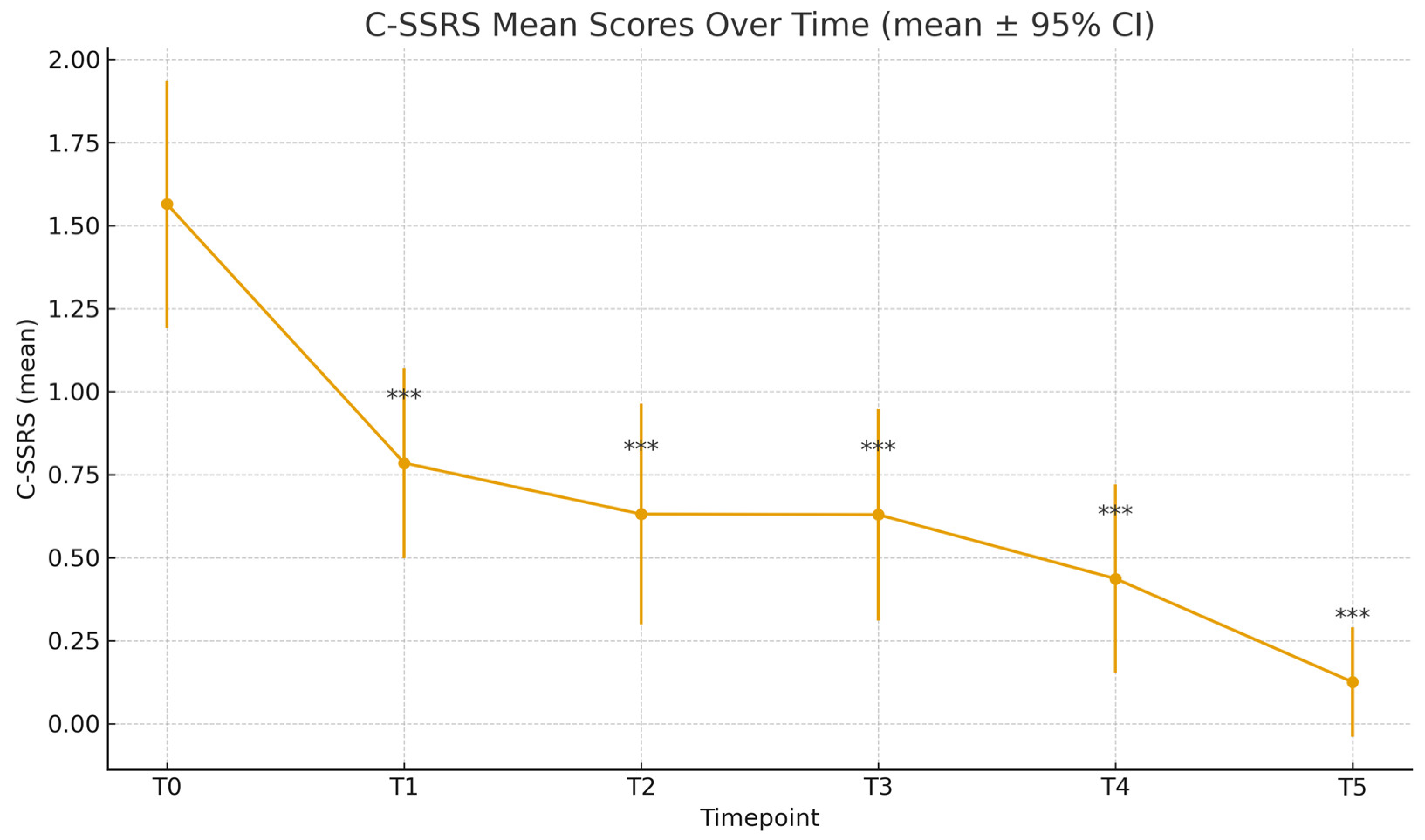

At baseline, the mean C-SSRS score was 1.56 (±1.65), while the mean MADRS score was 31.87 (±7.94). Time progression analysis of C-SSRS scores showed a statistically significant reduction at each time point, compared to T0 (

Figure 1,

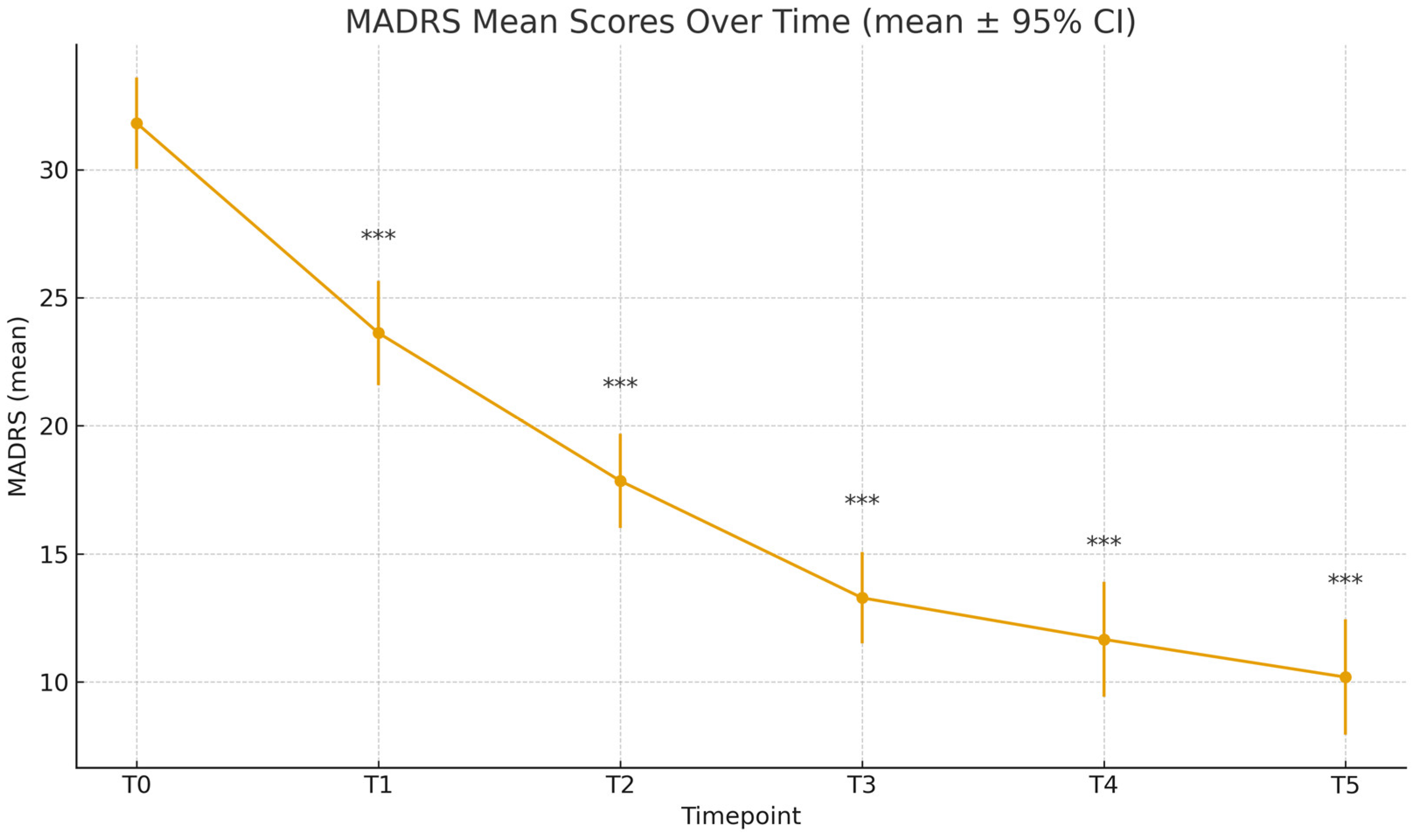

Table 2); the mean C-SSRS score decreased to 0.78 ± 1.28 (T1), 0.63 ± 1.34 (T2), 0.63 ± 1.26 (T3), 0.44 ± 1.05 (T4), and 0.12 ± 0.52 (T5). Paired-sample t-tests confirmed significance compared to baseline for all time points (T1-T5: p<.001). Similarly, MADRS scores decreased significantly throughout the different time points: 23.62 ± 9.08 (T1), 17.85 ± 7.83 (T2), 13.28 ± 7.13 (T3), 11.66 ± 8.37 (T4), 10.19 ± 7.33 (T5), all with p<.001 compared to T0 (

Table 2,

Figure 2).

Figure 1.

C-SSRS Scores Over Time. *** p <.001.

Figure 1.

C-SSRS Scores Over Time. *** p <.001.

Figure 2.

MADRS Scores Over Time.

Figure 2.

MADRS Scores Over Time.

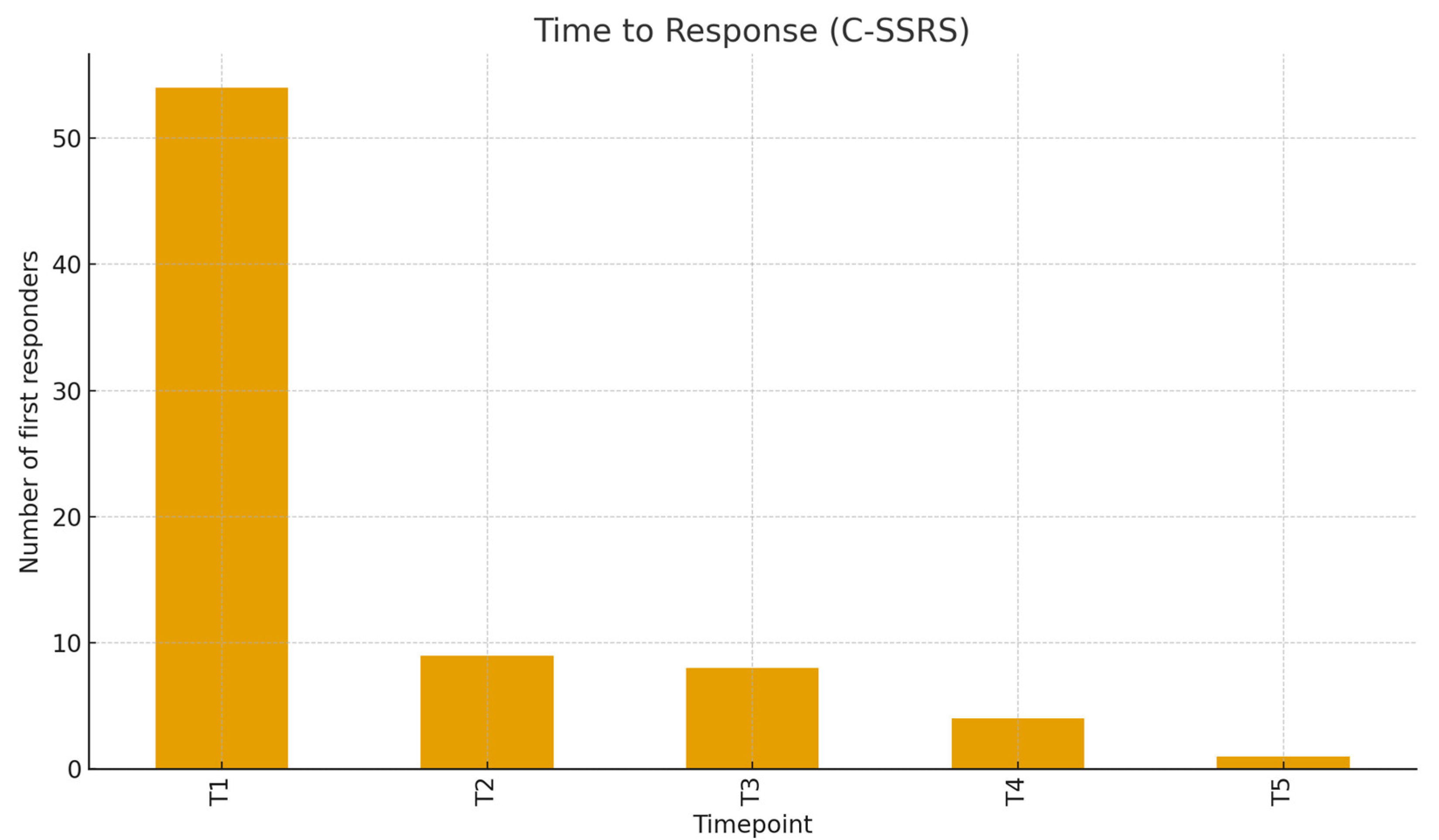

Figure 3.

Distribution of Clinical Response Over Time (C-SSRS).

Figure 3.

Distribution of Clinical Response Over Time (C-SSRS).

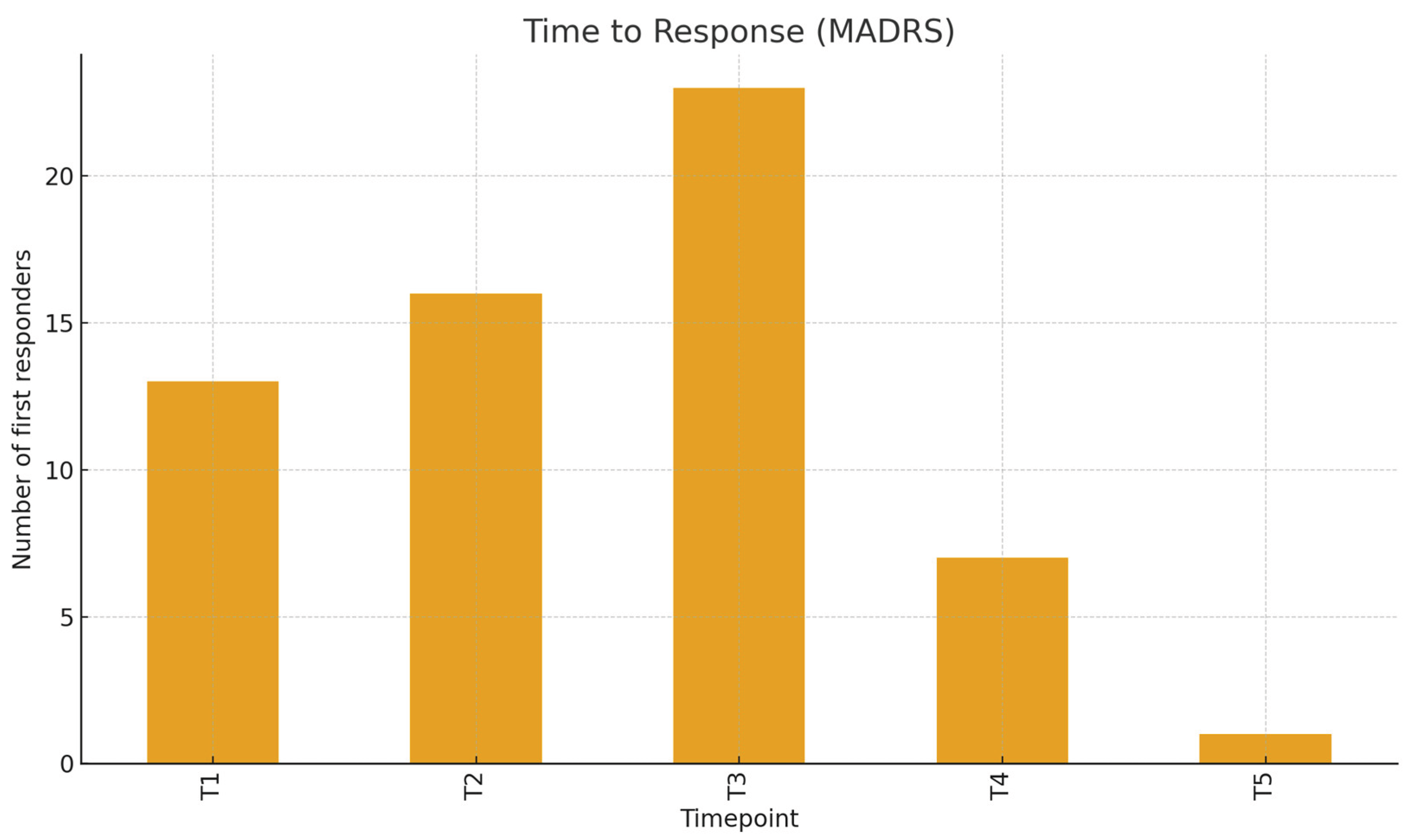

Figure 4.

Distribution of Clinical Response Over Time (MADRS).

Figure 4.

Distribution of Clinical Response Over Time (MADRS).

Correlation Pearson analysis conducted between C-SSRS and MADRS showed moderate and statistically significant correlations in the first five timepoints: T0 (r=292, p=0.009), T1 (r=313, p=0.005), T2 (r=0.36, p=0.003), T3 (r=0.295, p=0.02), T4 (r=0.317, p=0.018). At T5, the correlation was weaker (r=0.189) and not significant (p=0.244).

C-SSRS clinical definition for response (≥50% reduction or final score 0) was reached by 97.5% of patients evaluated at T5. The time-to-response (considering the C-SSRS) peaked at T1 (54 patients, 68.35%), with fewer first responses at T2–T5, respectively 9, 8, 4, and 1. Considering the MADRS, response rates increased from 16.7% at T1 to 37.5% at T2, 69.8% at T3, 76.8% at T4, and 76.7% at T5, with an overall MADRS response rate of 62.5.

Logistic regression showed that male gender was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of early response on the C-SSRS (OR=0.212, p=0.031). The lifetime number of SAs showed a negative - but non-significant - association with early C-SSRS response at T1 (OR = 0.54, p = 0.143). No other variables, such as age, diagnosis, or medications at t0, showed statistical significance.

4. Discussion

Data from this longitudinal study confirmed and reinforced the efficacy of intranasal Esketamine in rapidly reducing SI in patients with TRD. Seventy-four percent of responders achieved the response criteria on the C-SSRS within the first week, and this improvement was maintained at six-month follow-up. The results emerged in this paper confirm those of the ASPIRE I and II trials, which demonstrated a clinically and statistically significant reduction within 24 hours after the administration of intranasal Esketamine, compared to placebo. Previous studies, including ASPIRE I and II, used the specific item on suicide in the MADRS as a variable to measure suicidality, relying on indirect measures of SI. This study incorporated the C-SSRS, offering a more robust and specific evaluation of SI. A key strength of the present study is the use of the C-SSRS as the primary endpoint to quantify SI with a validated instrument. Many previous trials on Esketamine prioritized depressive symptom change, using the MADRS or the HAM-D, and tracked suicidality using the C-SSRS only as a secondary or safety outcome [

25,

26,

27]. By elevating the C-SSRS as a primary outcome, our design directly addresses anti-suicidal effects rather than inferring them from depression measures.

Furthermore, the observed correlation between the MADRS and C-SSRS scores in the early phases of treatment and their progressive reduction over time may suggest a partial distinction between improvements in depressive symptoms and SI. This interesting finding supports the hypothesis that Esketamine may exert anti-suicidal effects via mechanisms that could be, at least partially, different from its antidepressant action [

28]. Exploratory analyses have identified the baseline severity of SI and depressive symptoms as potential predictors of a more rapid and stronger treatment response. These findings are similar to previous data published in the literature: patients characterized by greater baseline severity of illness typically exhibit a greater magnitude of response [

29]. From a clinical perspective, this suggests that more severely ill patients may benefit from early intervention with Esketamine. The rapid reduction in SI observed within the first week of Esketamine treatment underscores the crucial need for prompt therapeutic interventions in patients with TRD presenting with active SI. In this population, the temporal dimension of treatment efficacy is not merely a matter of response, but of survival. These findings reinforce the unique role of Esketamine as an emergency intervention in affective crises, distinct from traditional antidepressants both in mechanism and latency of effect.

Interestingly, male gender was found to be a possible negative predictor of early response measured on the C-SSRS. Prior studies have explored gender differences in response to antidepressants in general [

30]. Biological factors, such as sex hormones influencing glutamatergic transmission, differences in brain structure, or pharmacokinetic variability, may partially account for this finding [

30]. Sociocultural factors, including differential help-seeking behaviors and stigma, may also play a role. Sociocultural factors rooted in male traditional culture, such as self-reliance, emotional stoicism, and fear of being perceived as weak, can lead men to delay help-seeking for depressive symptoms. Moreover, elevated levels of self-stigma and negative attitudes toward psychological care reduce honest reporting of SI at baseline and delay engagement in pharmacological and/or psychological treatment. Consequently, a large part of the male population starts evidence-based treatment only at crisis points, shortening the time for detecting rapid improvements and early response [

31,

32]. Future studies should prioritize sex-stratified analyses to better understand these dynamics and move toward more personalized treatment approaches. If confirmed, these findings could inform sex-sensitive treatment planning and contribute to more personalized approaches in psychiatric care.

Although the number of previous suicide attempts was not a statistically significant predictor of final response, the observed trend was clinically interesting. As reported in the literature, individuals with a history of suicidal behavior may exhibit diminished responsiveness to antidepressants in general [

33]. Larger studies are needed to determine if a positive history of suicide attempts is a reliable predictor of Esketamine efficacy. If this trend is confirmed, it would strengthen the rationale for early intervention with Esketamine before recurrent suicidal crises further complicate clinical outcomes.

For a correct interpretation of the present findings, the present limitations must be acknowledged. First, the limited sample size and exploratory nature of the analyses limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, the observational design and the lack of a placebo preclude causal inference, and unmeasured confounding factors may have influenced outcomes. Third, although the C-SSRS provides a more nuanced evaluation of suicidality, other aspects, such as impulsivity, were not systematically assessed and could modulate treatment response.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, intranasal Esketamine represented a promising option for the treatment of suicidality and depressive symptoms in patients with TRD. Future research should focus on predictor stratification, such as robust identification of clinical, demographic, and biological predictors of treatment response to guide personalized interventions. Integration of predictive modelling techniques, including machine learning algorithms applied to multimodal data (e.g., clinical, genetic, imaging, and electrophysiological markers), could pave the way for the development of validated, clinically actionable predictive algorithms. Trials designed specifically to assess sex differences and interventions tailored to patients with a history of suicide attempts represent additional priorities for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L., M.O., and M.V.; methodology, M.V., and M.O.; validation, B.B., M.O., and M.V.; data analysis, M.L.; data collection and curation, A.F, A.V., G.V., M.A., M.B., M.C., and N.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A. F. and M.L.; writing—review and editing, M.O. and M.V.; supervision, B.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All the procedures were conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Pavia Ethics Committee during the session of August 27, 2021 (Opinion No. 84157/21), with an amendment issued under No. 0102231/21.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

B.D. received grant/research support from LivaNova Inc., Angelini, and Lundbeck, and Lecture Honoraria from Angelini, Janssen, Otsuka, Viatris, Boehringer, Bromatech, and Lundbeck. M.O. received Lecture Honoraria from Janssen in the last two years. M.V. received Lecture Honoraria from Janssen, Lundbeck, and Neuraxpharm over the last two years. All other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD |

Antidepressant |

| AP |

Antipsychotic |

| ASST |

Azienda Socio-Sanitaria Territoriale |

| BD |

Bipolar Disorder |

| BDZ |

Benzodiazepine |

| C-SSRS |

Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale |

| CGI-SS-r |

Clinical Global Impression – Severity of Suicidality, revised |

| DSM-5-TR |

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5ª ed., Text Revision |

| EMA |

European Medicines Agency |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration. |

| GCP |

Good Clinical Practice |

| HAM-D |

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| IRCCS |

Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico |

| MADRS |

Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale |

| MDD |

Major Depressive Disorder |

| MDE |

Major Depressive Episode |

| MS |

Mood Stabilizer |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| SA |

Suicide Attempt |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| SNRI |

Serotonin–Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor |

| SSRI |

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor |

| SI |

Suicidal Ideation |

| TRD |

Treatment-Resistant Depression |

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide Worldwide in 2019 Global Health Estimates; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.L.; Qian, Y.; Jin, X.H.; et al. Suicide rates among people with serious mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-de la Torre, J.; Vilagut, G.; Ronaldson, A.; et al. Prevalence and variability of current depressive disorder in 27 European countries: a population-based study. Lancet Public. Health 2021, 6, e729–e738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelker, J.; Kuvadia, H.; Cai, Q.; et al. United States national trends in prevalence of major depressive episode and co-occurring suicidal ideation and treatment resistance among adults. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 5, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holma, K.M.; Melartin, T.K.; Haukka, J.; Holma, I.A.K.; Sokero, T.P.; Isometsä, E.T. Incidence and Predictors of Suicide Attempts in DSM–IV Major Depressive Disorder: A Five-Year Prospective Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2010, 167, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokero, T.P.; Melartin, T.K.; Rytsälä, H.J.; Leskelä, U.S.; Lestelä-Mielonen, P.S.; Isometsä, E.T. Suicidal Ideation and Attempts Among Psychiatric Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003, 64, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Ballegooijen, W.; Eikelenboom, M.; Fokkema, M.; et al. Comparing factor structures of depressed patients with and without suicidal ideation, a measurement invariance analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 245, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dold, M.; Bartova, L.; Fugger, G.; et al. Major Depression and the Degree of Suicidality: Results of the European Group for the Study of Resistant Depression (GSRD). Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018, 21, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Castroman, J.; Jaussent, I.; Gorwood, P.; Courtet, P. SUICIDAL DEPRESSED PATIENTS RESPOND LESS WELL TO ANTIDEPRESSANTS IN THE SHORT TERM. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 33, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, D.; Rihmer, Z.; Rujescu, D.; et al. The European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on suicide treatment and prevention. Eur. Psychiatry 2012, 27, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.N.; Michail, M.; Thompson, A.; Fiedorowicz, J.G. Psychiatric Emergencies. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 101, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G.S.; Bassett, D.; Boyce, P.; et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 2015, 49, 1087–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floriano, I.; Silvinato, A.; Bernardo, W.M. The use of esketamine in the treatment of patients with severe depression and suicidal ideation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2023, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinotti, G.; Vita, A.; Fagiolini, A.; et al. Real-world experience of esketamine use to manage treatment-resistant depression: A multicentric study on safety and effectiveness (REAL-ESK study). J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 319, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, D.J.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, L.; et al. Esketamine versus placebo on time to remission in major depressive disorder with acute suicidality. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, D.F.; Fu, D.J.; Qiu, X.; et al. Esketamine Nasal Spray for Rapid Reduction of Depressive Symptoms in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder Who Have Active Suicide Ideation With Intent: Results of a Phase 3, Double-Blind, Randomized Study (ASPIRE II). Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021, 24, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Chen-Li, D.; et al. The acute antisuicidal effects of single-dose intravenous ketamine and intranasal esketamine in individuals with major depression and bipolar disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 134, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Nemeroff, C.B.; et al. Synthesizing the Evidence for Ketamine and Esketamine in Treatment-Resistant Depression: An International Expert Opinion on the Available Evidence and Implementation. Am. J. Psychiatry 2021, 178, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, K.; Brown, G.K.; Stanley, B.; et al. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial Validity and Internal Consistency Findings From Three Multisite Studies With Adolescents and Adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindh, Å.U.; Waern, M.; Beckman, K.; Renberg, E.S.; Dahlin, M.; Runeson, B. Short term risk of non-fatal and fatal suicidal behaviours: the predictive validity of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale in a Swedish adult psychiatric population with a recent episode of self-harm. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, K.; Brown, G.K.; Stanley, B.; et al. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial Validity and Internal Consistency Findings From Three Multisite Studies With Adolescents and Adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greist, J.H.; Mundt, J.C.; Gwaltney, C.J.; Jefferson, J.W.; Posner, K. Predictive Value of Baseline Electronic Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (eC-SSRS) Assessments for Identifying Risk of Prospective Reports of Suicidal Behavior During Research Participation. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 11, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, S.A.; Åsberg, M. A New Depression Scale Designed to be Sensitive to Change. Br. J. Psychiatry 1979, 134, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, N.; Yamada, A.; Shiraishi, A.; Shimizu, H.; Goto, R.; Tominaga, Y. Efficacy and safety of fixed doses of intranasal Esketamine as an add-on therapy to Oral antidepressants in Japanese patients with treatment-resistant depression: a phase 2b randomized clinical study. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.J.; Ju, P.C.; Sulaiman, A.H.; et al. Long-term Safety and Efficacy of Esketamine Nasal Spray Plus an Oral Antidepressant in Patients with Treatment-resistant Depression– an Asian Sub-group Analysis from the SUSTAIN-2 Study. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2022, 20, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, N.; Chen, L.; Lane, R.; et al. Long-term safety and maintenance of response with esketamine nasal spray in participants with treatment-resistant depression: interim results of the SUSTAIN-3 study. Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 48, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawczak, P.; Feszak, I.; Bączek, T. Ketamine, Esketamine, and Arketamine: Their Mechanisms of Action and Applications in the Treatment of Depression and Alleviation of Depressive Symptoms. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier, J.C.; DeRubeis, R.J.; Hollon, S.D.; et al. Antidepressant Drug Effects and Depression Severity. JAMA 2010, 303, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moderie, C.; Nuñez, N.; Fielding, A.; Comai, S.; Gobbi, G. Sex Differences in Responses to Antidepressant Augmentations in Treatment-Resistant Depression. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 25, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Üzümçeker, E. Traditional Masculinity and Men’s Psychological Help-Seeking: A Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Psychology 2025, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bye, H.H.; Måseidvåg, F.L.; Harris, S.M. Men’s Help-Seeking Willingness and Disclosure of Depression: Experimental Evidence for the Role of Pluralistic Ignorance. Sex. Roles 2025, 91, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtet, P.; Jaussent, I.; Lopez-Castroman, J.; Gorwood, P. Poor response to antidepressants predicts new suicidal ideas and behavior in depressed outpatients. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014, 24, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and clinical variables of the sample.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and clinical variables of the sample.

| Variables |

|

| Mean age (± SD) |

49.1 ± 16.8 years |

| Gender |

55% female

45% male |

| Relationship status |

58.8% partnered

41.2% single |

| Employment status |

46.2% unemployed

53.8% employed |

| Diagnosis |

84% MDE in MDD

16% MDE in BD |

| Age at first MDE (mean ± SD) |

31.5 ± 15.5 years |

| Lifetime number of MDE |

4.8 ± 5.9 |

| Current MDE duration (mean in days ± SD) |

241 ± 194 days |

| Lifetime number of SAs (mean ± SD) |

0.4 ± 0.8 |

| Family history for depression or SAs (%) |

Yes 70 %

No 30 % |

| Psychopharmacotherapy at baseline |

|

| SSRIs |

60% |

| SNRIs |

40% |

| Other ADs |

43.8% |

| Atipical APs |

52.5% |

| MSs |

38.8% |

| BDZs |

56.2% |

Table 2.

C-SSRS and MADRS scores at different time points.

Table 2.

C-SSRS and MADRS scores at different time points.

| Timepoint |

C-SSRS ± SD |

p vs T0 |

MADRS ± SD |

p vs T0 |

| T0 |

1.56 ± 1.65 |

— |

31.81 ± 7.94 |

— |

| T1 |

0.78 ± 1.28 |

<.001 |

23.62 ± 9.08 |

<.001 |

| T2 |

0.63 ± 1.34 |

<.001 |

17.85 ± 7.83 |

<.001 |

| T3 |

0.63 ± 1.26 |

<.001 |

13.28 ± 7.13 |

<.001 |

| T4 |

0.44 ± 1.05 |

<.001 |

11.66 ± 8.37 |

<.001 |

| T5 |

10.19 ± 7.33 |

<.001 |

10.19 ± 7.33 |

<.001 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).