1. Introduction

Controlled Source Audio-Frequency Magnetotellurics (CSAMT) is a frequency-domain artificial field source electromagnetic detection technique derived from Audio-Frequency Magnetotellurics (AMT) and Magnetotellurics (MT) [

1,

2,

3]. In the 1950s, based on Cagniard 's published work, the magnetotelluric sounding method was developed. This technique calculates apparent resistivity by observing the orthogonal components of the natural earth's electric and magnetic fields [

4]. Within the audio frequency range (10⁻¹ to 10³ Hz), the natural magnetotelluric field is relatively weak and subject to significant anthropogenic interference. In the 1970s, Professor D.W. Strangway and his student M.A. Goldstein addressed these issues by proposing the observation of audio-frequency electromagnetic fields generated by artificial sources using AMT measurement techniques. As the frequency, field strength, and direction of the electromagnetic field can be artificially controlled, and the observation method is identical to AMT, this technique is termed Controlled-Source Audio-Frequency Magnetotelluric Sounding [

5,

6,

7].

CSAMT is primarily categorized into scalar, vector, and tensor types based on measurement methodology [

8,

9]. Equatorial dipole arrays are currently predominant for scalar measurements. However, during CSAMT operations, most existing transmission sources employ single electric dipole elements. In comparison, electric dipole sources function as omnidirectional antennas with low radiation efficiency and uncontrolled patterns. Coupled with energy dissipation along long-distance paths, only a fraction of the radiated energy within the far-field region is utilized during observation, rendering the majority of energy inaccessible. Consequently, during exploration in noisy or complex terrain, the signal-to-noise ratio of raw data often fails to meet exploration requirements. Furthermore, regardless of whether scalar, vector, or tensor measurements are employed, theoretical calculations and simulations reveal that within the 360° azimuth range, all components of the electromagnetic field exhibit certain weak zones in the radiation lobe patterns [

10,

11,

12]. Consequently, to ensure data quality, measurement areas are subject to strict limitations beyond which surveys become impracticable. Furthermore, constraints imposed by far-field conditions typically necessitate a transmit-receive distance of 10–15 km. Where geological complexity prevents meeting these conditions, surveys may be impossible to conduct; even if feasible, data accuracy cannot be guaranteed [

13,

14,

15].

An antenna system is a device that converts guided waves within a circuit transmission path into electromagnetic waves, or vice versa. For routine tasks, an antenna with basic functionality suffices, requiring neither high radiation concentration nor specialized beam shapes [

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, modern radio systems demand superior antenna performance to fulfil diverse requirements, such as employing low-side-lobe beams for interference mitigation [

20], utilizing specific beams to cover designated areas [

21], or deploying scanning beams to cover extensive airspace [

22]. These capabilities are challenging for a single antenna to achieve. Therefore, utilizing the principle of spatial interference of electromagnetic waves, multiple identical antenna elements are arranged in a regular array, with each component receiving an appropriate excitation distribution [

23,

24,

25,

26]. If the elements lie along a straight line or within a single plane, the array is termed a linear or planar array [

27]. The primary purpose of this approach is to enhance antenna directivity or achieve a desired radiation pattern shape [

28]. The development of array antenna theory commenced in the mid-20th century, subsequently finding application in fields such as radar, satellite communications, resource exploration, and environmental monitoring [

29,

30].

Artificial field source antennas function as spatial filters during exploration [

31], serving as the primary defense against interference for CSAMT [

32]. Antenna anti-interference technologies primarily encompass low and ultra-low side lobes, side lobe masking, adaptive side lobe cancellation, adaptive array systems, beam control, antenna coverage, and scan control [

33]. Traditional single-dipole artificial field source antennas and non-adaptive array artificial field source antennas feature fixed beam directions. They cannot automatically track the receiver location while suppressing interference, rendering them unsuitable for future electromagnetic operations in complex electromagnetic environments [

34].

Adaptive beamforming differs from non-adaptive beamforming (i.e., pattern synthesis). The former determines element weights based on received signals rather than predetermined target patterns. Adaptive beamforming patterns can evolve in response to variations in interference signals and noise, offering superior resolution and enhanced interference suppression capabilities [

35]. Adaptive array antenna technology represents an emerging concept that employs algorithms to adaptively control antenna beamforming [

36]. The primary objective of interference mitigation in adaptive array antennas is to adaptively align the main beam with the direction of the receiving unit while maintaining a low-side lobe main beam pattern. This enables the receiving unit to capture the electric field signal at maximum amplitude, thereby suppressing interference or reducing the intensity of interfering signals.

Based on the fixed nature of the weight vector in beamformers, they can be categorized into two types: adaptive and conventional beamformers [

37]. Conventional beamformers employ a fixed weight vector for processing transmit array signals, which not only simplifies computation but also facilitates implementation. However, the uncertainty inherent in the received signal significantly constrains the effectiveness of its estimation [

38]. Consequently, adaptive beamforming techniques have been developed. This approach involves adaptively adjusting the weight vector based on received data and specific design criteria, thereby enhancing interference suppression capabilities and improving resolution [

39]. Moreover, the selection of design criteria can be tailored to different prior information. Commonly employed criteria include the minimum mean square error criterion, minimum variance criterion, constant modulus criterion, and maximum signal-to-interference-plus-noise ratio criterion [

40]. This paper employs the principles of electromagnetic field interference superposition and the directional pattern multiplication theorem, replacing a single grounded horizontal dipole antenna field source with an array antenna artificial field source. The focus is on adaptive beamforming methods based on the maximum signal-to-interference-plus-noise ratio criterion. During CSAMT exploration, this approach reduces side lobe levels and minimizes multipath interference at the receiver point, achieving adaptive directional radiation for specific regions. Consequently, it enhances the signal-to-noise ratio in these areas, effectively improving exploration resolution and accuracy.

2. Theoretical Foundations of Finite-Length Dipole Antennas

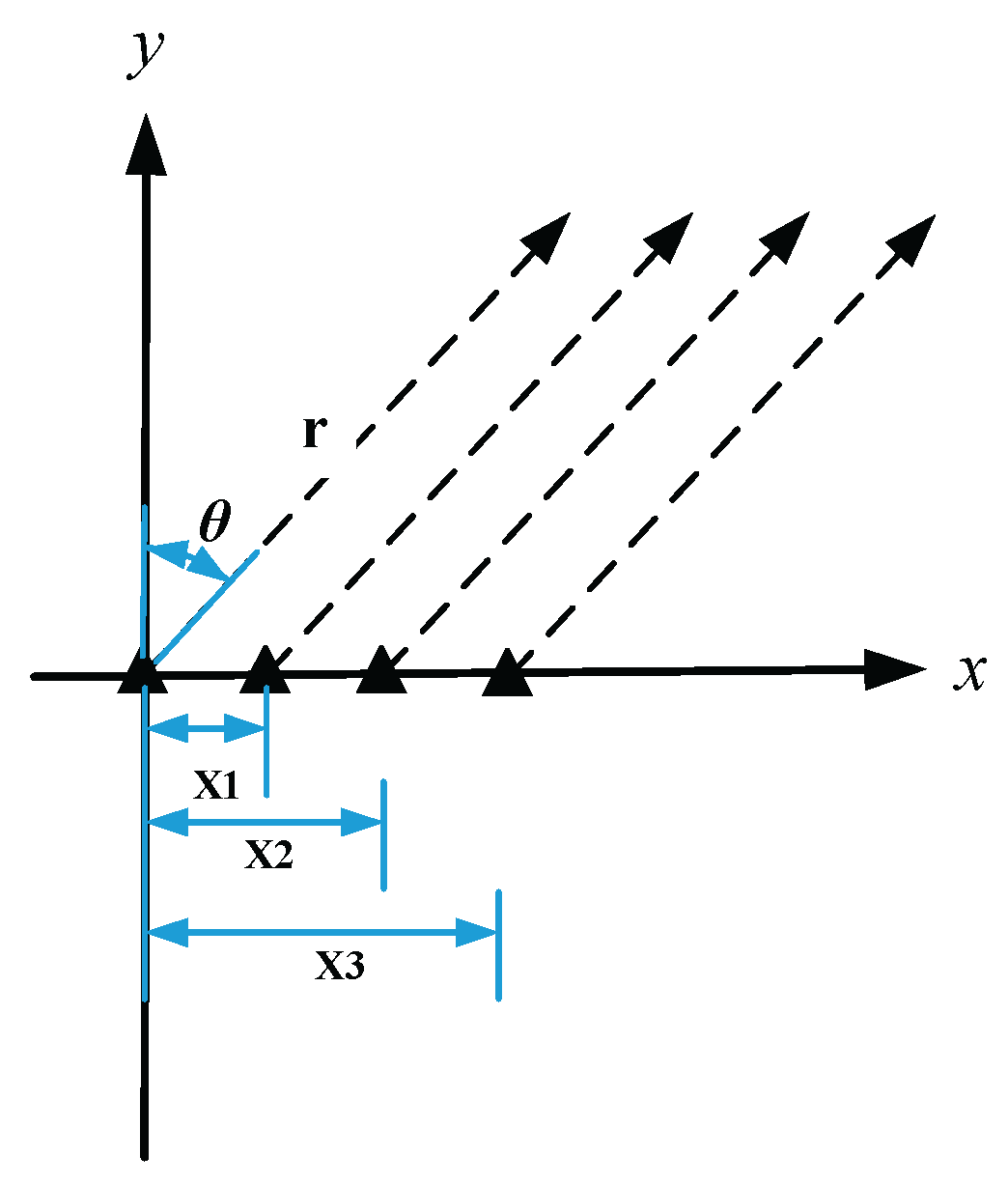

Suppose a finite electric dipole antenna of length is positioned along the y-axis in spherical coordinates, as depicted in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. If the current distribution along the conductor is sinusoidal, it may be expressed as:

Where (

) denotes the position of the current source, representing the distance from the current source to the observation point, and

represents the unit vector along the y-axis. Thus, a finite-length dipole antenna can be divided into multiple small dipole antennas of equal length

. The radiation from these small dipole antennas of length

in the far-field region can be expressed as follows:

where

denotes the distance between the current element and the observation point;

represents the radial component of the electric field;

denotes the component tangential to the longitude;

signifies the component perpendicular to the meridian plane;

denotes the radial component of the magnetic field;

signifies the component tangential to the longitude;

denotes the component perpendicular to the meridian plane.

Since we are concerned with the radiation characteristics of dipole antennas in the far-field region, we assume that

,

, as shown in

Figure 1. The electric field can be expressed as:

After integration, we obtain:

Through calculation, we can derive:

Therefore, the Poynting vector

can be written as:

The radiation intensity is:

The power density should be integrated along the radial direction. Therefore, the radiated power along the radial direction is:

The directional coefficient is:

4. Research on Adaptive Pattern Synthesis Method for Linear Array Field Sources

4.1. Optimal Weight Vector Design Criterion

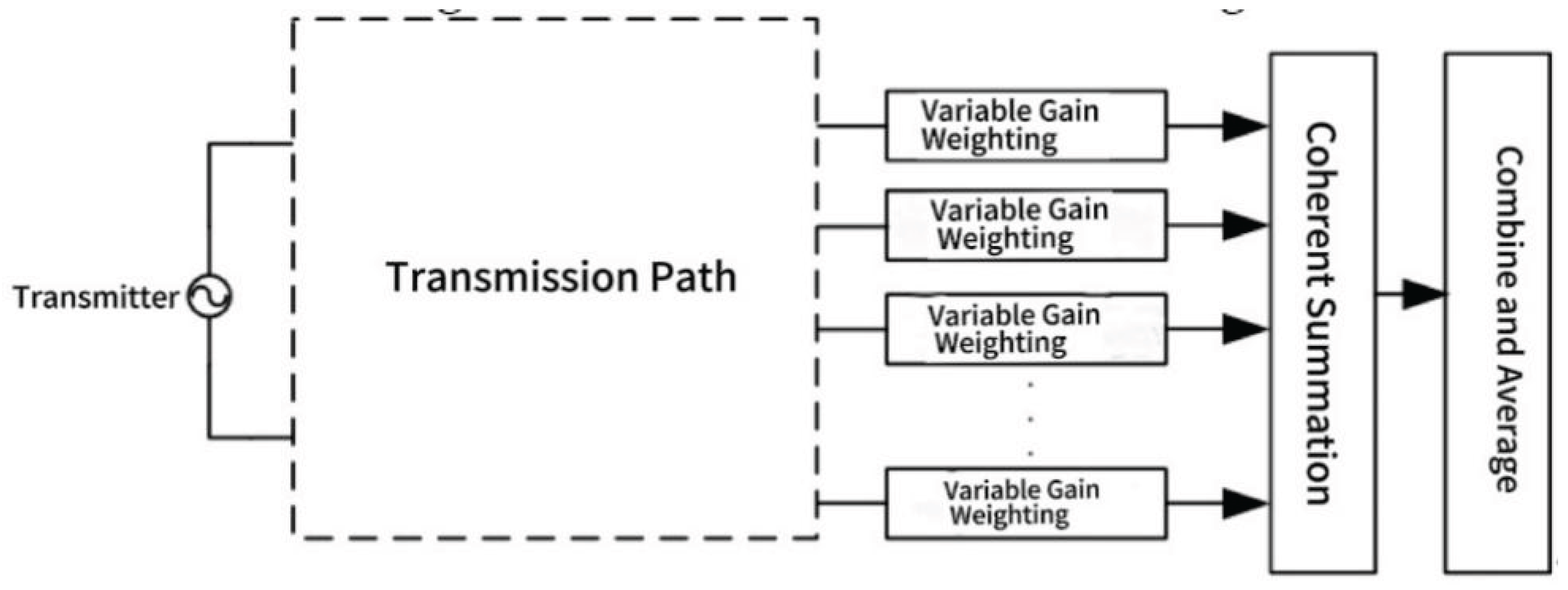

During the CSAMT process, the receiving end typically incorporates multiple reception channels. This serves two purposes: firstly, to enhance measurement efficiency by enabling simultaneous assessment of multiple pathways; secondly, to facilitate diversity reception at specific measurement points, thereby strengthening interference resistance. The receiving unit employs multiple unpolarized antennas to collect electric field signals. During the diversity reception within the receiving unit, signals are acquired from N independent signal branch paths. Maximum Ratio Combining (MRC) technology can then be applied to achieve diversity gain.

Maximum Ratio Combining is an algorithm that selects weighting coefficients based on the principle of maximizing the combined signal-to-noise ratio. In this approach, the weighting coefficient is positively correlated with the amplitude of the electric field signal and negatively correlated with the noise power. Consequently, the algorithm assigns larger weighting coefficients to branches with better channel conditions and smaller coefficients to those with poorer conditions. Maximum ratio combining enhances the useful signal while attenuating noise and interference, thereby improving the quality of the received signal. Assuming the noise components are mutually independent, the sum of the signal-to-noise ratios across all combining branches constitutes the combined signal-to-noise ratio for maximum ratio combining.

During maximum ratio combining (MRC), there are N diversity branches at the receiver. Phase adjustment is performed, and in-phase addition is implemented according to the selected gain coefficient. The signals are then input to subsequent combining and averaged. The schematic diagram of Maximum Ratio Combining is shown in

Figure 4.

According to the Chebyshev inequality, the maximum combined signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) after diversity combining is achieved when the variable gain weighting coefficient is set as , where represents the signal amplitude of the i-th diversity branch, and denotes the noise power of each branch, with . When N non-polarized probes measure the same point or are in close proximity, the received noise power can be considered equal, ultimately reducing the process to maximum ratio combining of signal amplitudes.

The combined output is given by:, This expression indicates that a higher SNR leads to a greater contribution to the combined signal. The average output SNR after maximum ratio combining is , where represents the average SNR of each branch before combining, and denotes the average output SNR after maximum ratio combining.

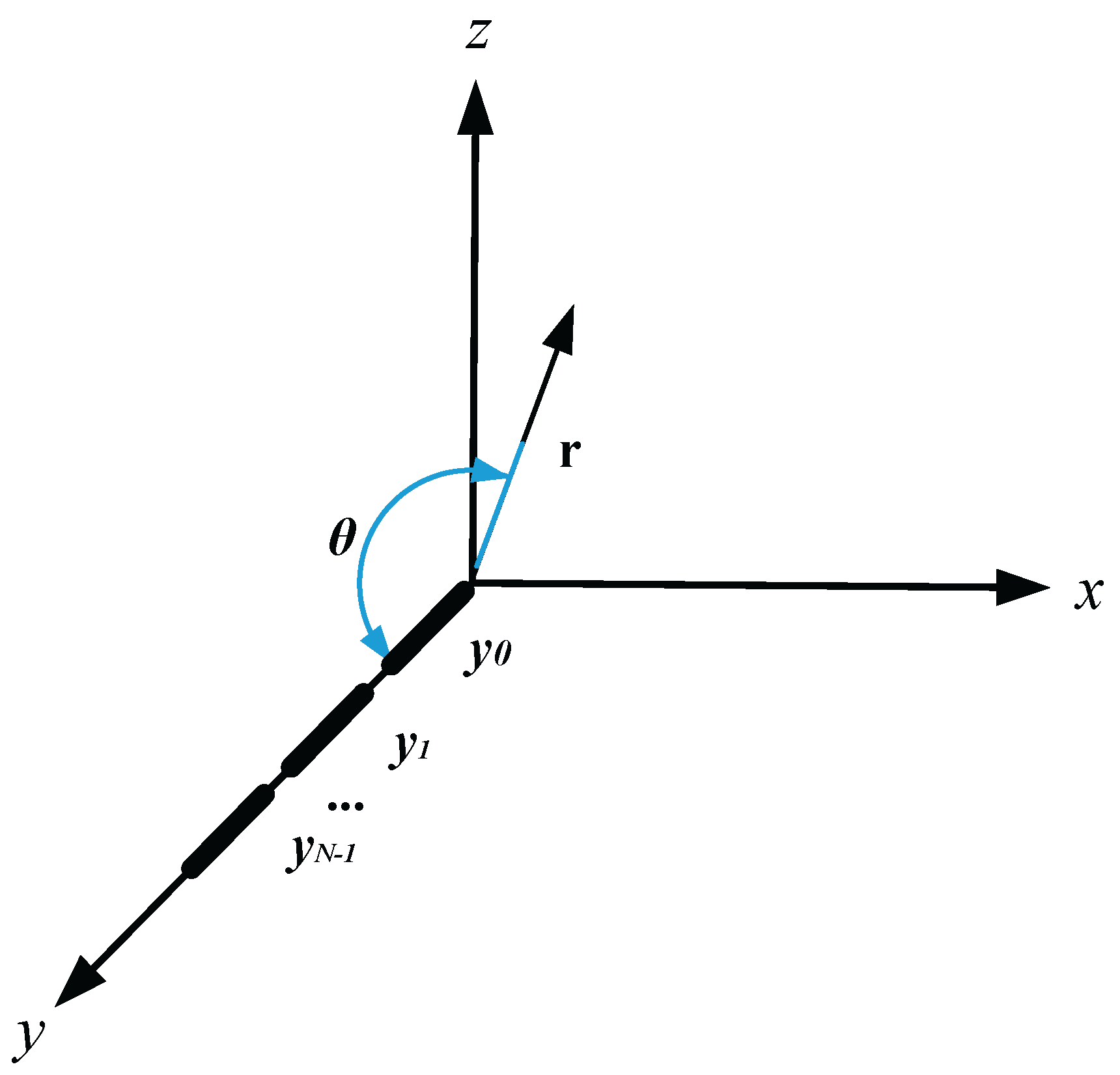

4.2. Model Development of a Parallel Oscillator Field Source

Assume there are N identical oscillator unit antennas in the array, each of length 2L, arranged in parallel along the y-axis at positions

,

,

,…,

, as shown in

Figure 5.

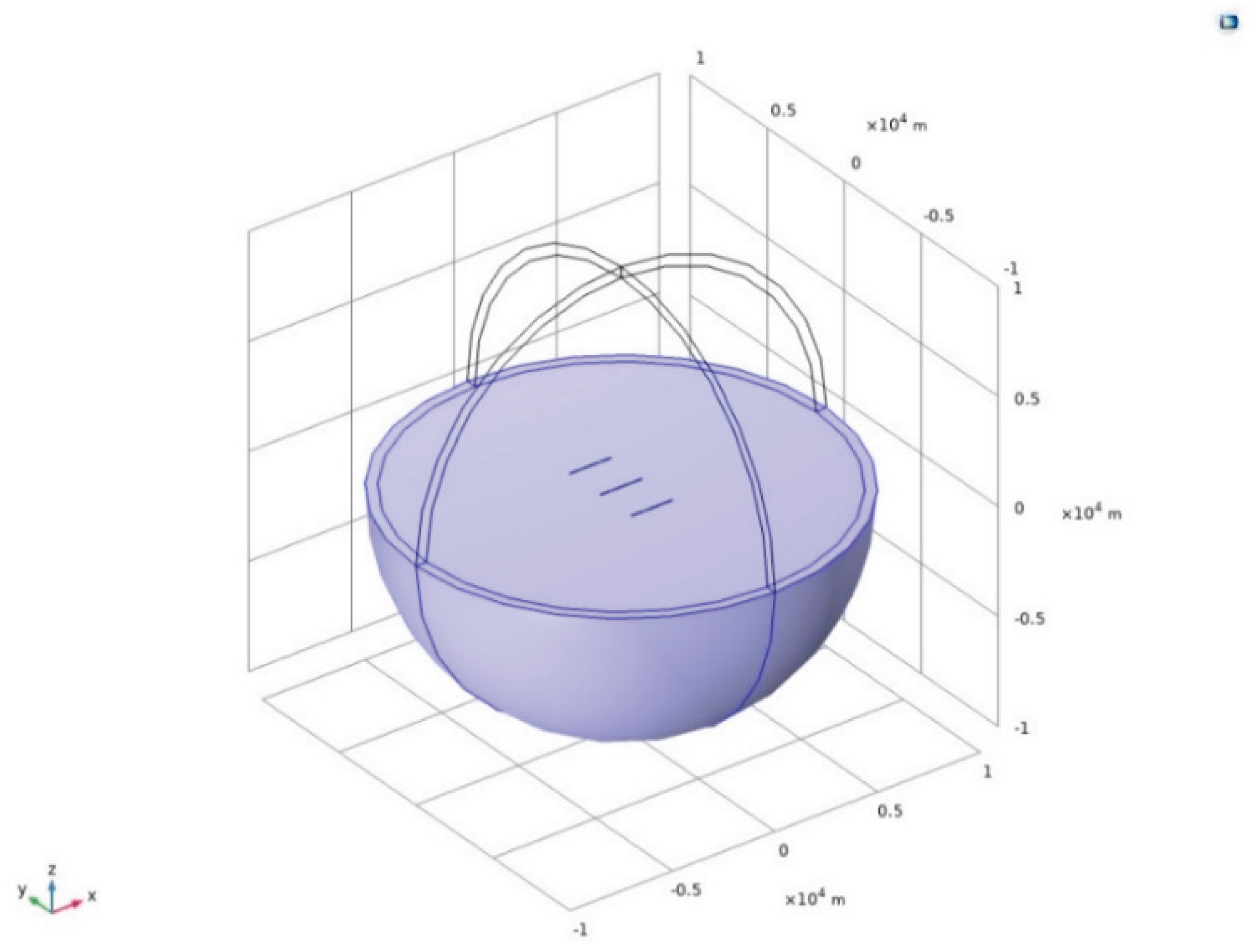

A numerical model of an artificial field source utilizing a linear array of parallel oscillators was developed within the COMSOL software environment. As illustrated in

Figure 6, the 3×1 parallel oscillator linear array CSAMT model consists of a sphere with a radius of 10 km. The upper half-space is air (

,

,

), while the lower half-space is soil (

,

,

). In the model, a 3×1 antenna array with an arm length of 1 km and a spacing of 2 km between elements is positioned along the y-axis on the ground surface, with an arm radius of 0.05 m.

4.3. Model Development of a Coaxial Oscillator Field Source

Similar to the structure of a linear horizontal oscillator array, a coaxial oscillator linear array is also arranged in a straight line. However, the elements are aligned coaxially with equal spacing. Assume the array consists of N identical oscillator unit antennas, each of length 2L, co-axially positioned along the y-axis at locations

,

,

,…,

, as illustrated in

Figure 7.

A numerical model of an artificial field source based on a linear array of coaxial oscillators was established in the COMSOL Multiphysics software environment. As shown in

Figure 8, the 3×1 coaxial oscillator linear array CSAMT model consists of a sphere with a radius of 10 km. The upper half-space is air (

,

,

), while the lower half-space is soil (

,

,

). In the model, a 3×1 antenna array with an arm length of 1 km and an inter-element spacing of 1 km is positioned along the y-axis on the ground surface, with an arm radius of 0.05 m.

During operation, the centers of the three array elements are excited with different amplitudes. If the number of array elements is increased, simulations based on the synthesis method discussed earlier indicate that the sidelobes can be further suppressed.

4.4. Adaptive Beam Control Simulation for a Parallel Oscillator Field Source

Based on the model illustrated in

Figure 6, a CSAMT model incorporating a uniform half-space and a 3×1 parallel dipole antenna array was established. The three element antennas, each with an arm length of 1 km, were excited with different phases and Taylor-synthesized amplitudes (502 V, 1055 V, and 502 V, respectively). The port phase of element antenna 1 was set to 0 rad, while that of element antenna 2 was varied from -1.5708 rad to 1.5708 rad in increments of 0.5236 rad. The port phase of element antenna 3 was set to twice the variation value of element antenna 2. The configuration of the 3×1 parallel dipole antenna array with lumped ports is depicted in

Figure 9.

The phase difference between each lumped port is governed by a specific rule known as the arithmetic phase value, which is utilized to control the main lobe direction. By performing a parameter sweep of the

ph variable as specified in

Table 1, the beam scanning capability of the 3×1 parallel dipole antenna array can be effectively achieved.

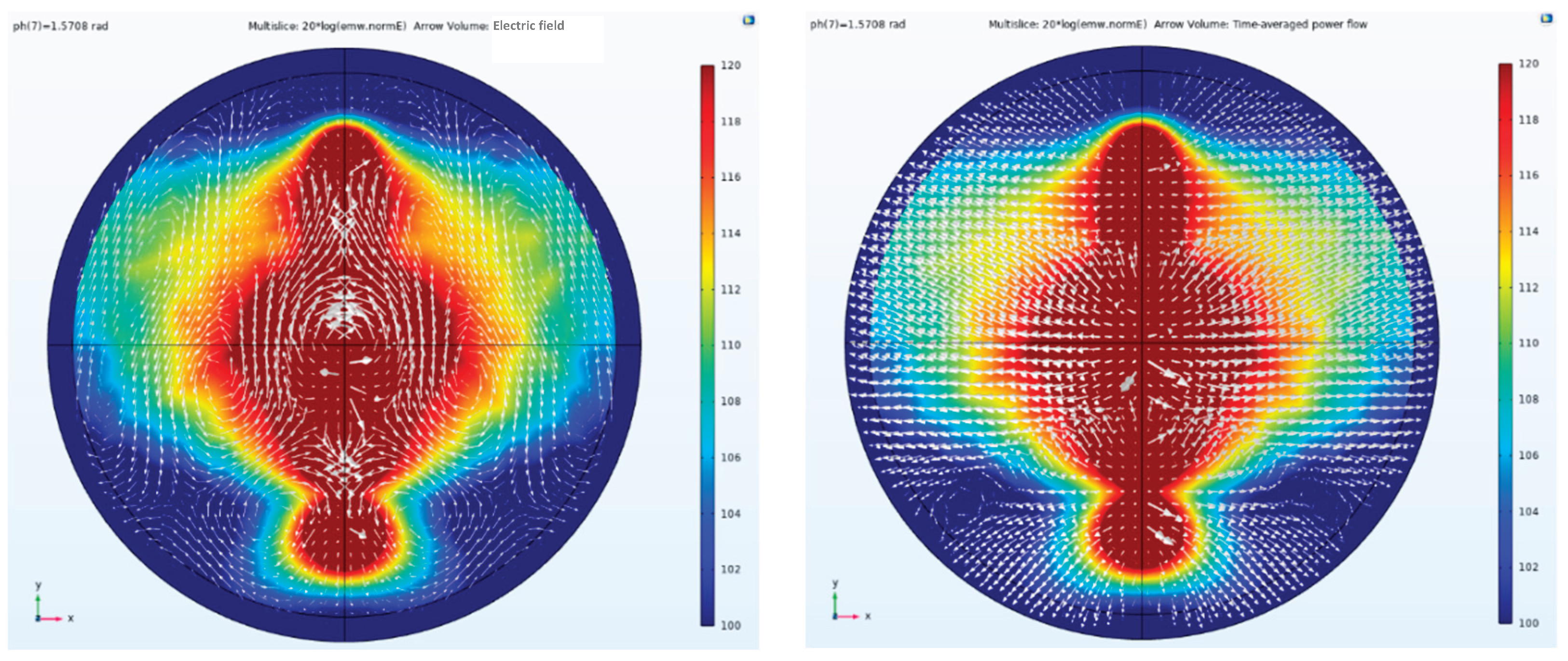

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 illustrate the scenario where the three antenna elements are excited with identical phases. Under this in-phase excitation, the beam is concentrated toward the center, with the maximum energy focused along the central axis of the parallel dipole linear array. Consequently, CSAMT surveys conducted along this central line achieve the highest SNR. This beamforming process is implemented based on Taylor synthesis.

Figure 11 shows the beam focused centrally without deflection. The direction of the Poynting vector indicates the flow of energy.

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 illustrate a 3×1 parallel dipole antenna array aligned along the y-axis, excited with different phases and Taylor syntheses (502 V, 1000 V, and 502 V). When the port phase of antenna element 1 is 0 rad, while the port phases of antenna elements 2 and 3 are -1.5708 rad and -3.1416 rad respectively, the beam deflects toward antenna element 3 because the phase of antenna element 3 lags sequentially behind those of antenna elements 2 and 1.

Conversely, when the port phase of antenna element 1 is 0 rad, while the port phases of antenna elements 2 and 3 are 1.5708 rad and 3.1416 rad respectively, the phase of antenna element 3 leads that of antenna elements 2 and 1 in sequence, and the beam deflects toward antenna element 1.

Figure 14 shows a side view of the electric field amplitude, direction, and Poynting vector arrows when a phase difference of -0.5236 rad is applied to a parallel-element linear array; Conversely,

Figure 15 shows the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction, and Poynting vector arrow for a parallel-element linear array with a phase difference of +0.5236 rad. It can be observed that after applying positive and negative phase differences to the parallel-element linear array, the beam points toward the positive and negative directions of the y-axis, respectively. Based on digital processing technology, the transmitter system can rapidly and flexibly adjust phase differences, with all adjustments completed instantaneously. Therefore, during CSAMT surveys, beam directional adjustments are also performed instantaneously. When employing distributed reception, this enables extensive maneuverable scanning and exploration of the survey area.

Figure 16.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the three antenna elements are excited by the Taylor synthesis and 1.0472 rad phase difference.

Figure 16.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the three antenna elements are excited by the Taylor synthesis and 1.0472 rad phase difference.

Figure 17.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the three antenna elements are excited by the Taylor synthesis and 1.5708 rad phase difference.

Figure 17.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the three antenna elements are excited by the Taylor synthesis and 1.5708 rad phase difference.

The front-to-back ratio (F/B) of a directional antenna represents the ratio of the power flux density in the maximum radiation direction (defined as 0°) to the maximum power flux density in the opposite direction (defined as 180° ± 20°), as shown in Equation (24). This metric reflects the antenna's effectiveness in suppressing the rear lobe; a higher F/B value indicates less radiation (or reception) toward the rear.

where

is the maximum power flux density in the radiation direction, and

is the maximum flux density in the backward direction.

Table 2 shows the electric field values and F/B ratios generated by a 3×1 parallel dipole antenna array with different phase differences at various receiving points. When the phase difference is 0 rad, electromagnetic waves radiate uniformly in both directions. When the excitation phases on the three antenna elements are inconsistent, the electromagnetic waves will be deflected. Based on the F/B data in

Table 2, the F/B increases almost proportionally as the phase difference increases.

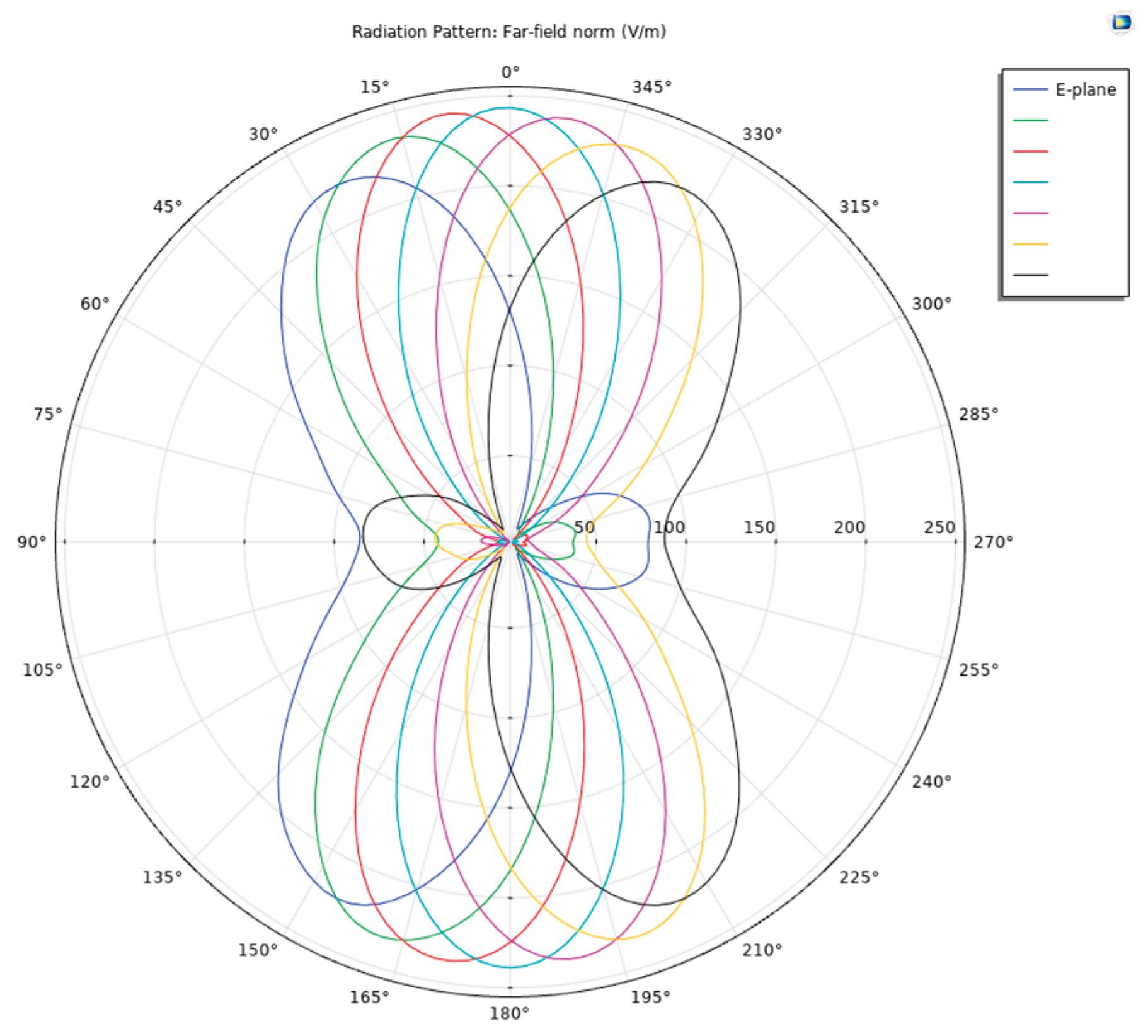

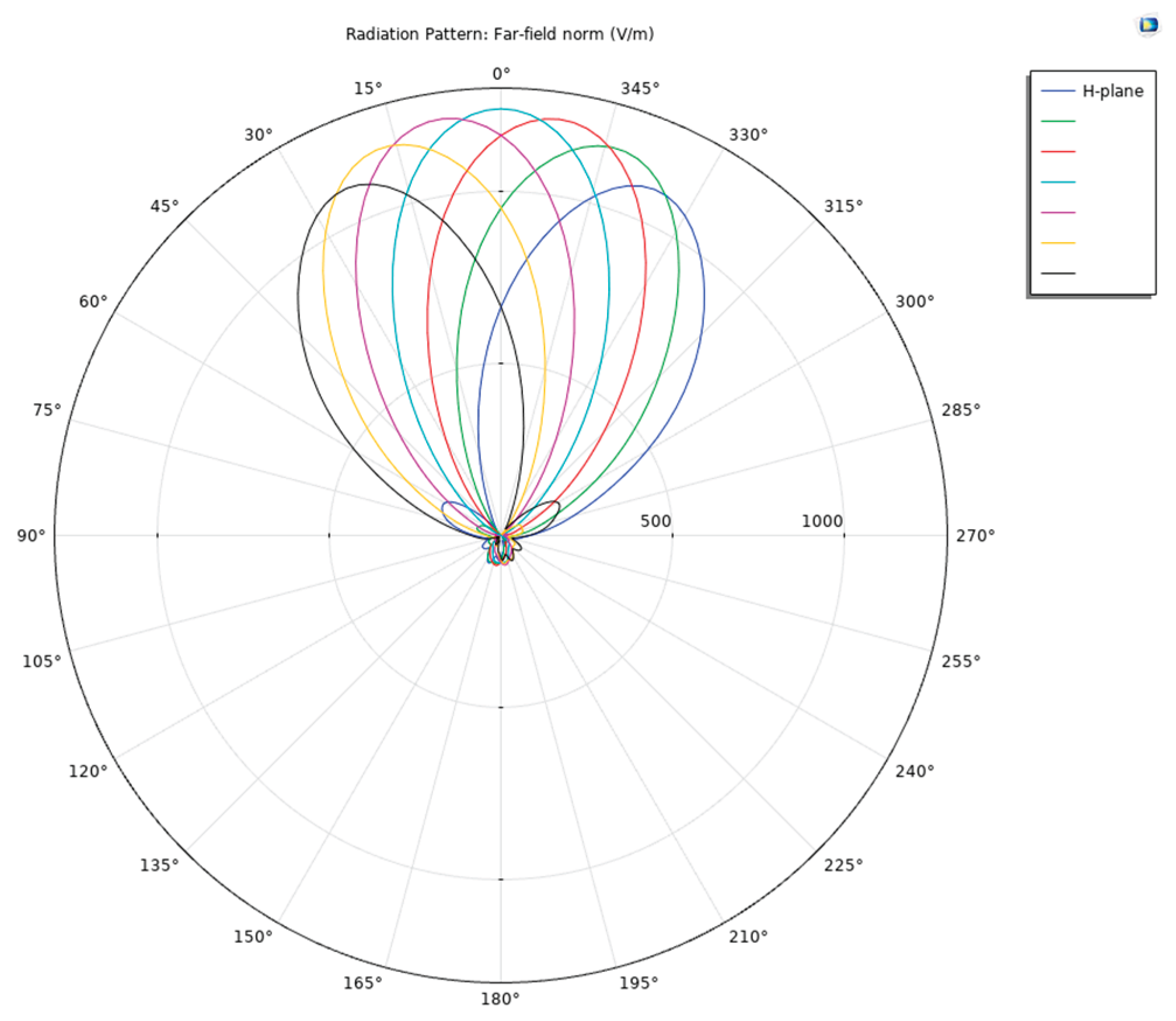

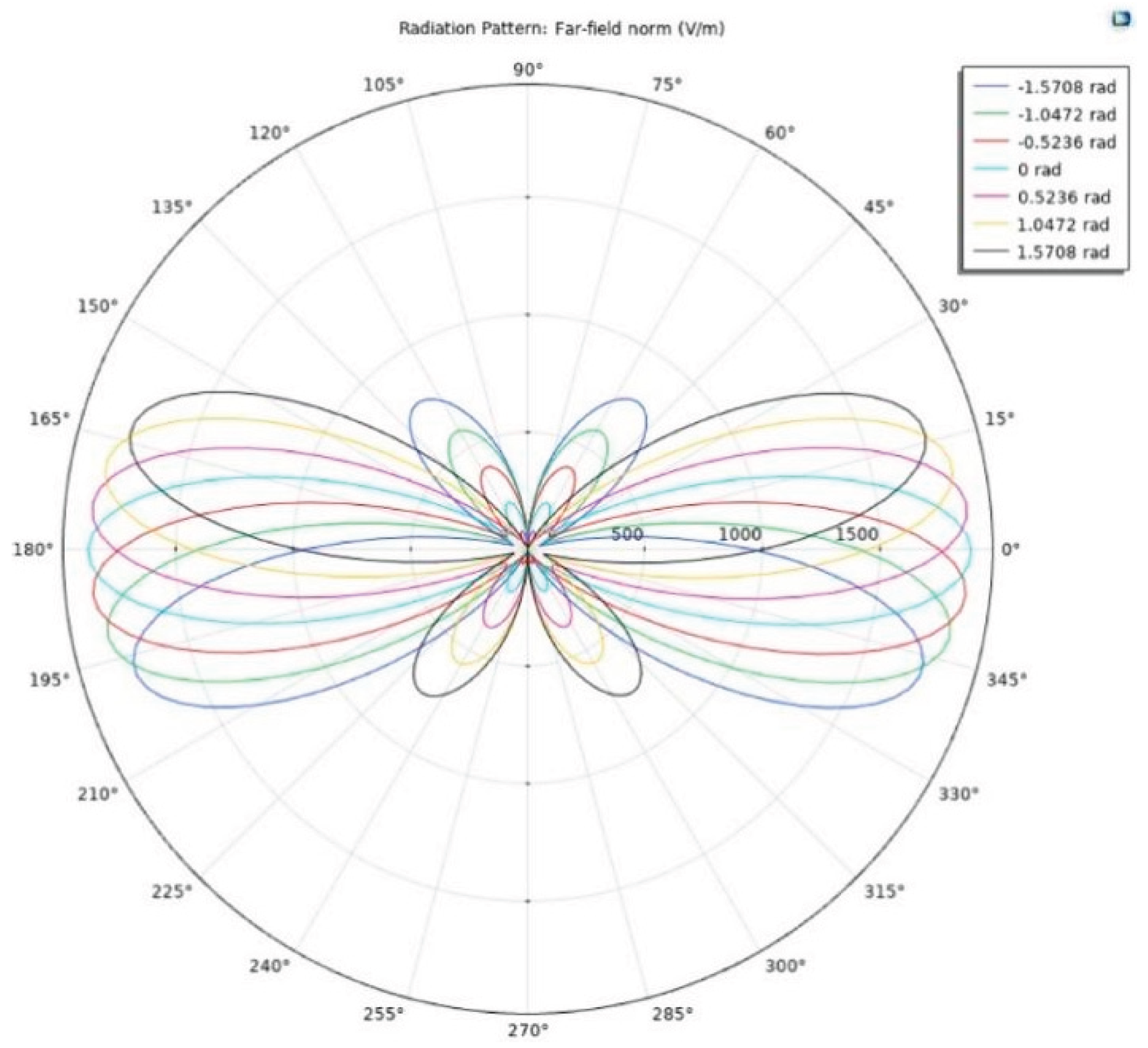

As shown in

Figure 18 and

Figure 19, the E/H plane beam pattern exhibits different deflections at multiple phase differences. The greater the phase difference, the larger the deflection angle within a certain range. By adjusting the phase difference, the main beam direction can be aligned to point toward the region of interest. When phase excitation is applied via lumped ports using Taylor synthesis, the main lobe is symmetrically distributed along the antenna axis (light blue), and beam steering can be achieved by advancing the arithmetic phase (other colors).

The E-plane pattern reveals that the main beam completes the scanning process under excitation with varying phase differences. This process holds significant physical importance during CSAMT operations, enabling extensive scanning across the exploration area. Compared to traditional fixed-position exploration methods, it concentrates energy while achieving broad coverage. By moving only the receiver unit while keeping the transmitter stationary, large-area exploration with a high signal-to-noise ratio is accomplished—suitable for both general surveys and detailed exploration.

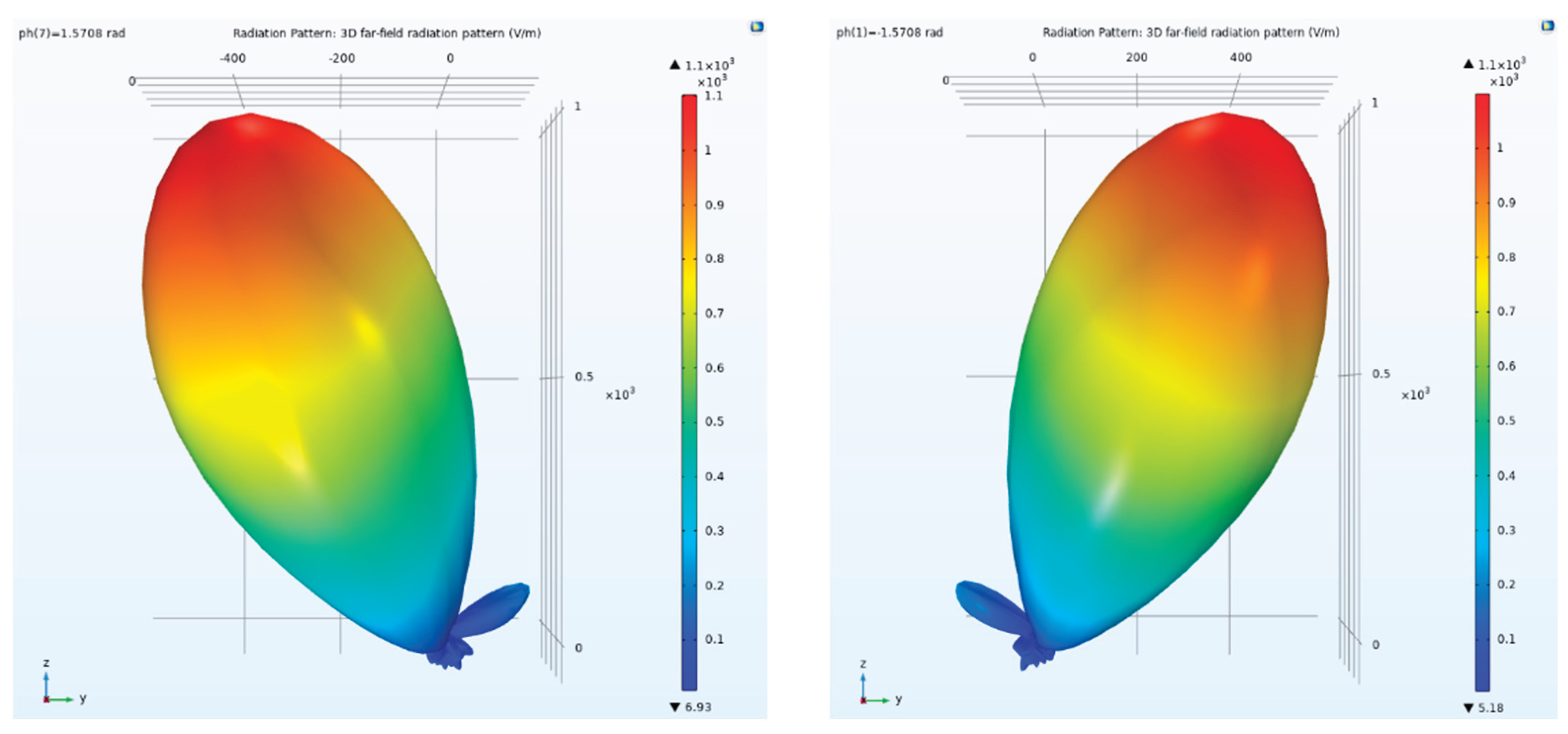

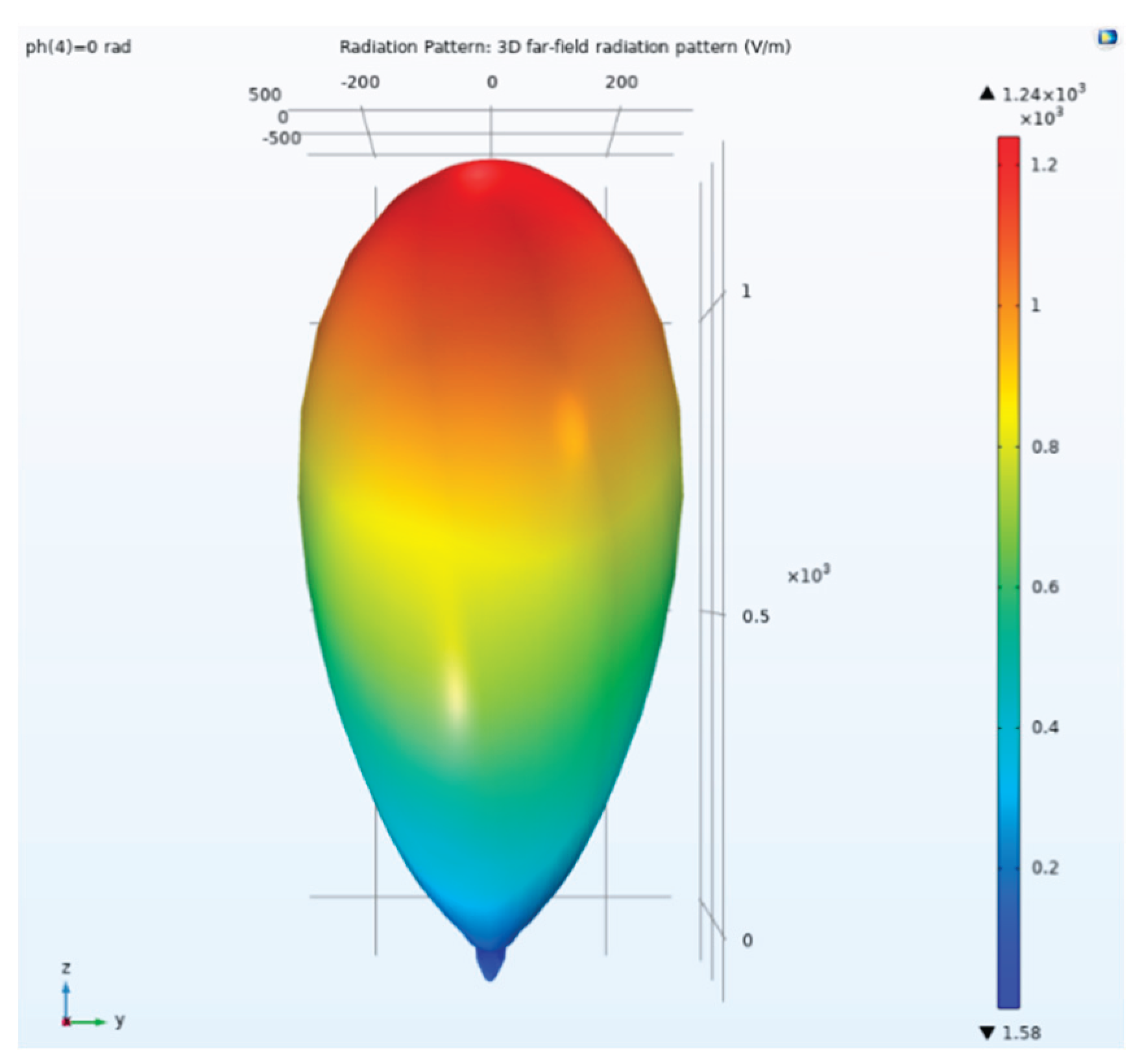

A well-designed antenna array should exhibit low side lobe levels, which are not readily apparent when plotted linearly. The V/m scale displayed in the 3D far-field patterns makes the main lobe and side lobes more visible, as shown in

Figure 20 and

Figure 21.

All of this demonstrates the feasibility of phase-difference weighted beamforming. During CSAMT surveys using parallel-element linear arrays, differential phase excitation enables the main radiation lobe to be directed toward regions of interest. Compared to the omnidirectional radiation of individual elements, this approach effectively enhances both the received field strength amplitude and SNR at receivers within the target area.

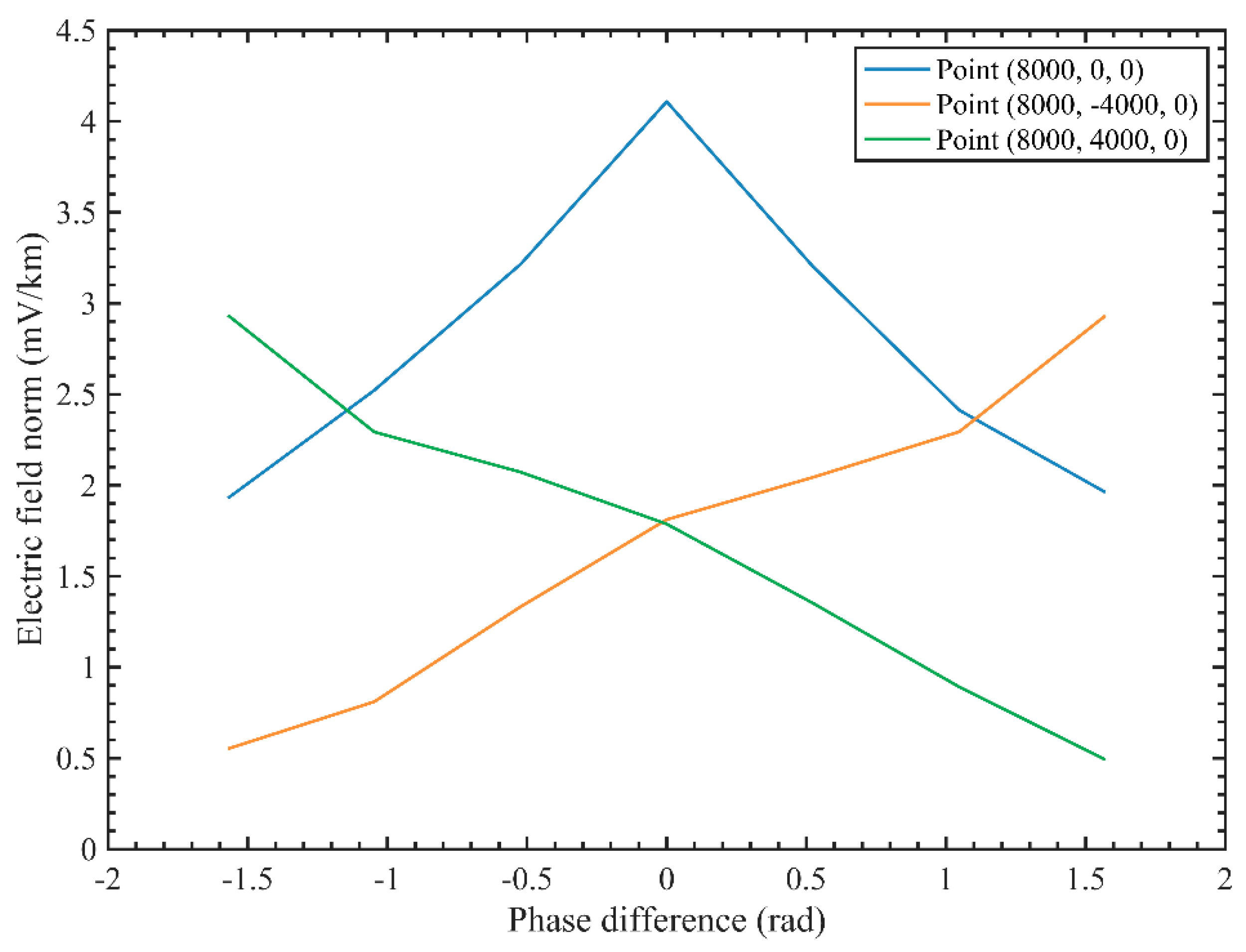

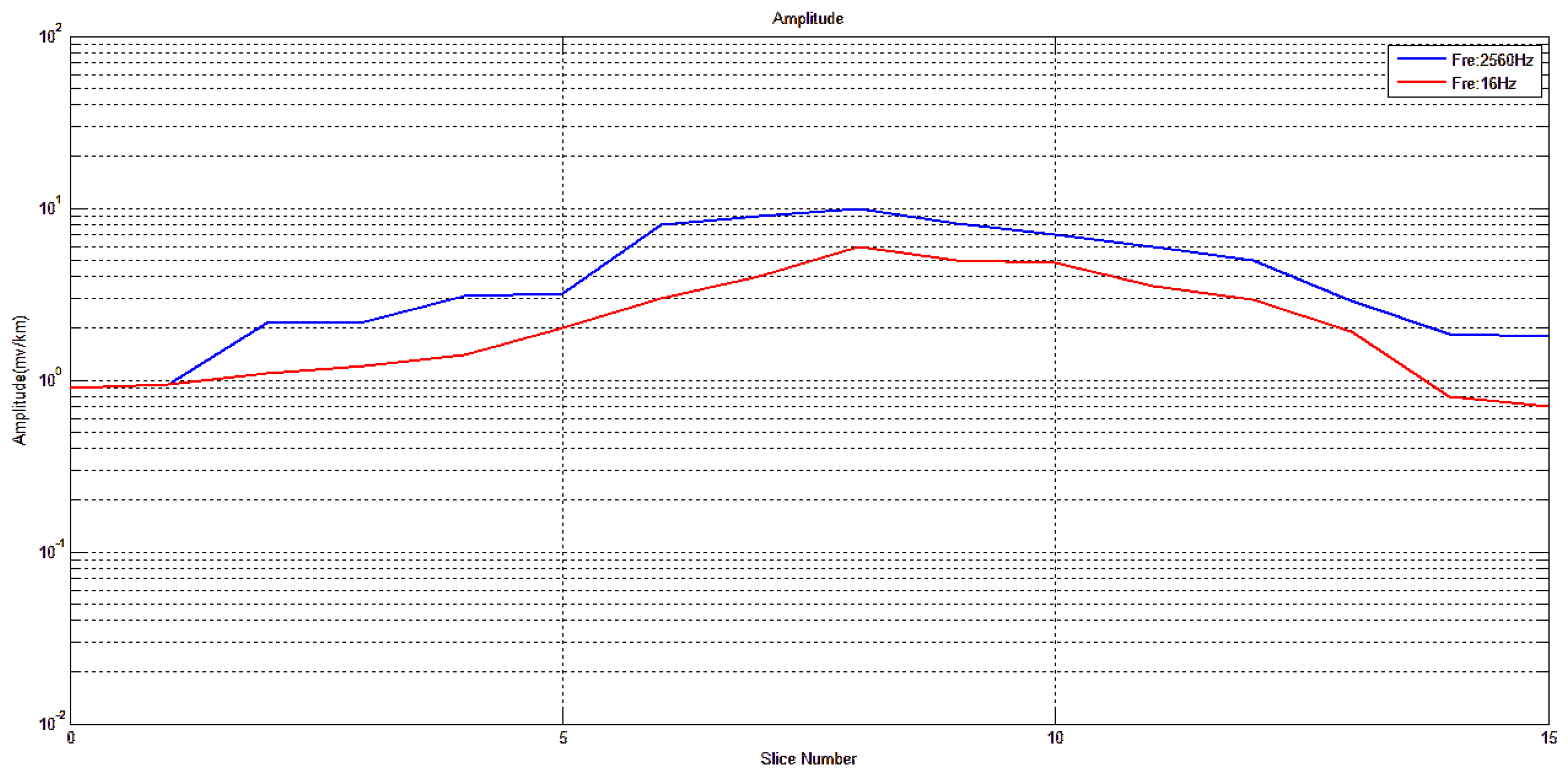

Table 3 presents numerical simulations of CSAMT adaptive beamforming based on an artificial field source using a parallel-element linear array under different phase differences. It can be observed that at the point (8000, 0, 0), as the phase difference changes from -1.5708 rad to 1.5708 rad in increments of 0.5236 rad, the numerical values exhibit a peak at the center and gradually decrease toward both sides. This fully demonstrates the beam scanning process: the electric field amplitude is highest when the main beam passes through the point (8000, 0, 0), and weakens at this point as the beam scans to either side. The points (8000, 4000, 0) and (8000, -4000, 0) also validate the beam scanning physics. At a phase difference of -1.5708 rad, the point (8000, 4000, 0) is highest, while the amplitude at point (8000, -4000, 0) is lowest. Conversely, when the phase difference is 1.5708 rad, the electric field amplitude at point (8000, -4000, 0) is highest, while the amplitude at point (8000, 4000, 0) is lowest.

Consistent with

Table 3,

Figure 22 also presents numerical simulations of CSAMT adaptive beamforming based on a parallel-element linear array artificial field source under varying phase differences. As the phase difference transitions from -1.5708 rad to 1.5708 rad, the main beam progressively scans from point (8000, 0, 0) through point (8000, 0, 0) to point (8000, -4000, 0). (8000, 4000, 0), through point (8000, 0, 0), and gradually scans to point (8000, -4000, 0).

4.5. Adaptive Beam Control Simulation for a Coaxial Dipole Field Source

Based on the model shown in

Figure 8, a uniform half-space and 3×1 coaxial antenna array CSAMT model was established. Different phase and Taylor synthesis (502 V, 1055 V, and 502 V) excitations were applied to the three array elements with a 1 km arm length. Element 1's port phase was set to 0 rad. Element 2's port phase varied from -1.5708 rad to 1.5708 rad, changing every 0.5236 rad. Element 3's port phase variation was twice that of Element 2.

Figure 23 depicts the 3×1 coaxial dipole antenna array with lumped ports. The phase difference between each lumped port is governed by a specific rule known as the arithmetic phase value, which controls the direction of the main lobe.

By performing the pH parameter scan shown in

Table 4, the beam scanning capability of the 3×1 coaxial dipole antenna array can be obtained.

Figure 24 illustrates the case where three array elements are excited with identical phase. It can be seen that with identical phase excitation, the beam converges toward the center, with maximum energy concentrated along the centerline of the coaxial linear array. Conducting CSAMT surveys at this centerline position yields the highest signal-to-noise ratio.

Figure 25 shows a side view of the electric field amplitude, direction, and Poynting vector arrows. The array antenna is excited with a Taylor synthesis and a phase difference of -1.5708 rad. It can be observed that after applying the maximum phase difference excitation, the beam direction undergoes the greatest angular deviation. That is, the beam is effectively deflected according to the set parameters. The arrow direction indicates the direction of the Poynting vector, representing the propagation direction of energy. It is undeniable that after phase control through the array elements, the propagation direction of the electromagnetic wave has been altered.

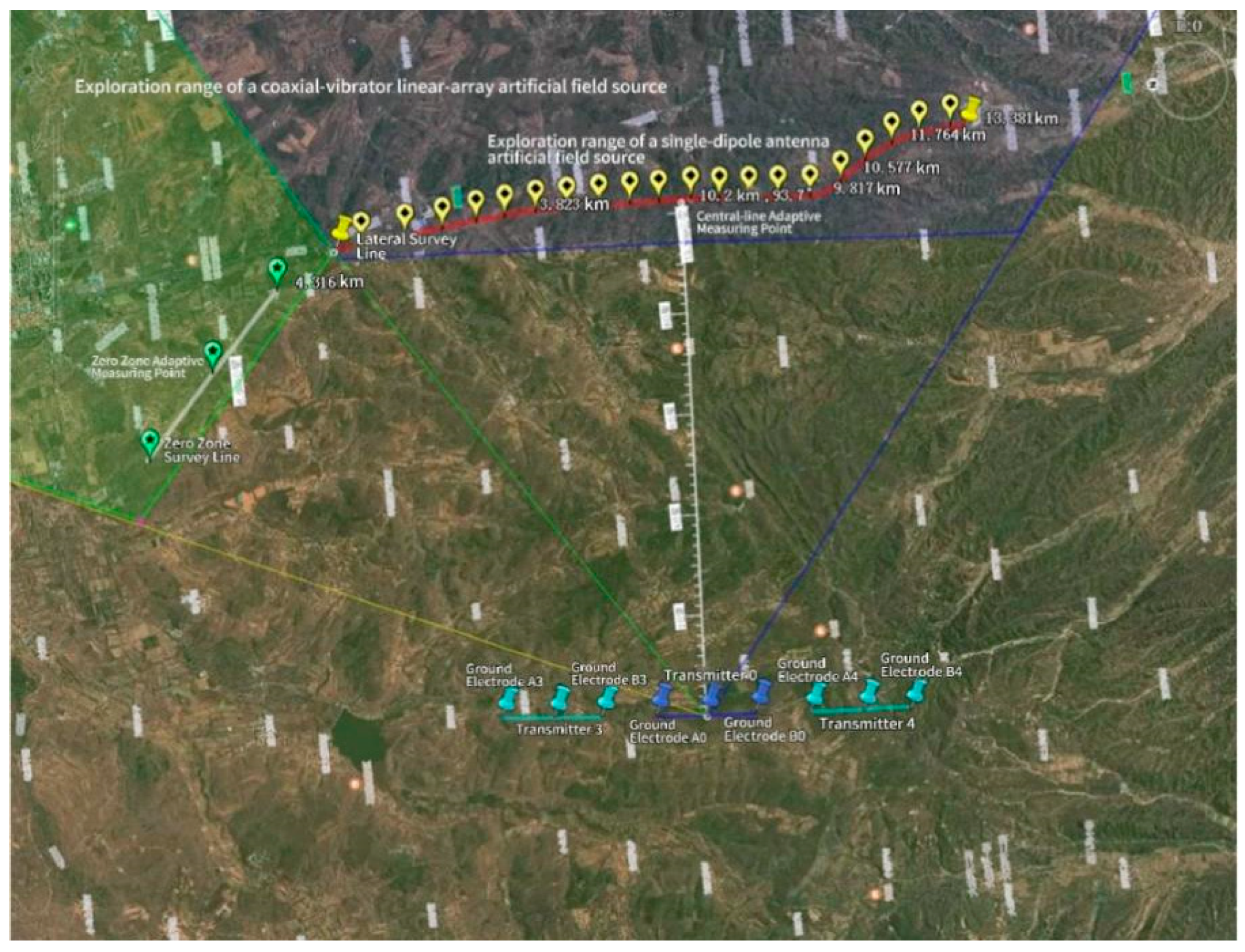

Therefore, in actual exploration, even with a fixed artificial field source, the beam coverage can be significantly expanded. This breaks through the traditional 60° exploration range limitation of single-element dipole artificial field sources, extending the range to approximately 90°.

Figure 26,

Figure 27,

Figure 28,

Figure 29 and

Figure 30 illustrate beam angle deflections under other phase differences.

As shown in

Figure 31, the E-plane pattern exhibits different deflections at multiple phase differences. The greater the phase difference, the larger the deflection angle within a given range. By adjusting the phase difference, the main beam direction can be steered toward specific regions. When phase excitation is applied via lumped ports using Taylor synthesis, the main lobe exhibits symmetrical distribution along the antenna axis (light blue), and beam steering can be achieved by advancing the arithmetic phase (other colors).

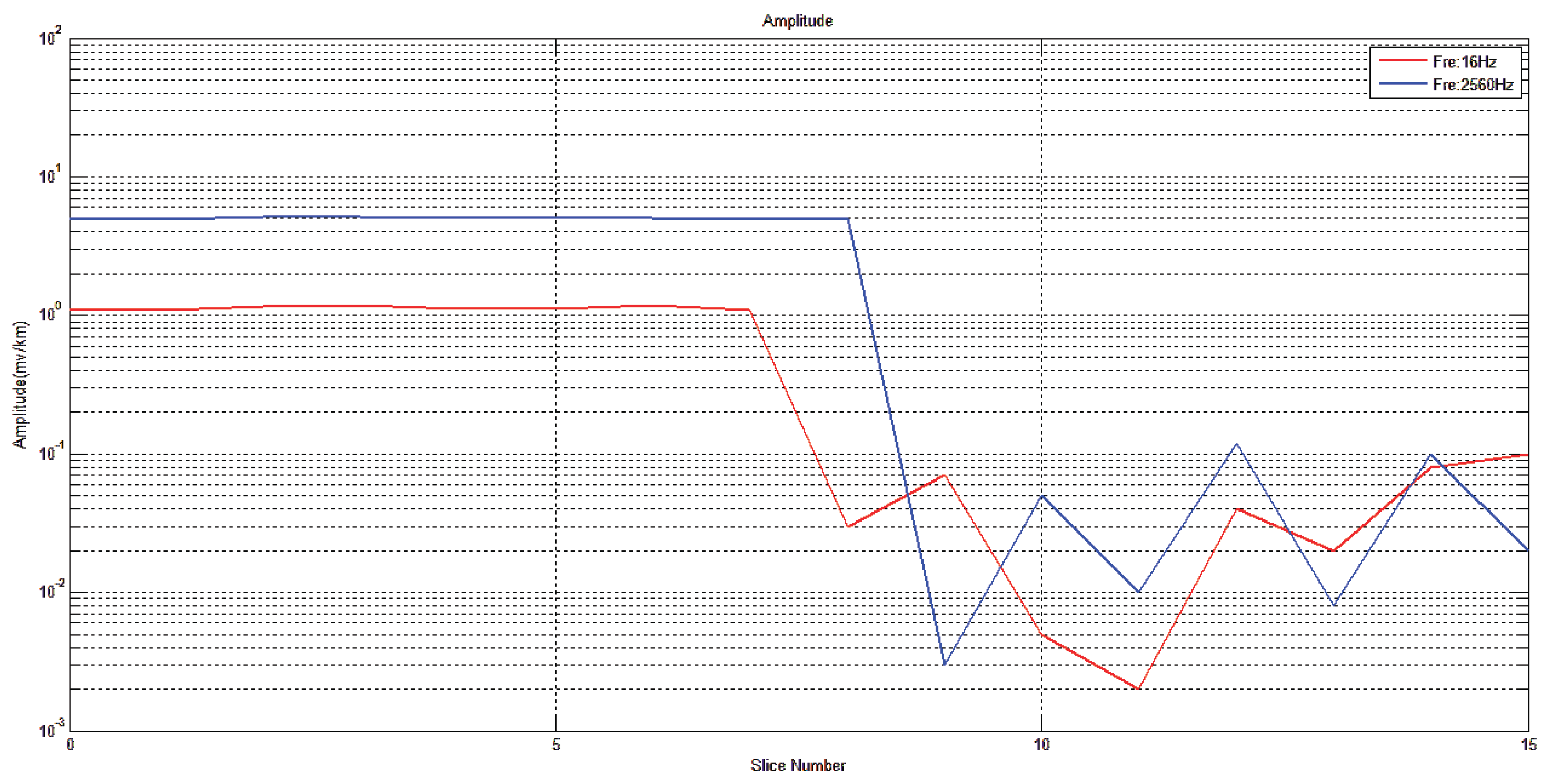

Table 5 presents numerical simulations of CSAMT adaptive beamforming based on a coaxial linear array artificial field source at different phase differences. Similar to the parallel-element artificial field source, at the point (8000, 0, 0), as the phase difference varies from -1.5708 rad to 1.5708 rad in 0.5236 rad increments, the values exhibit a peak at the center and gradually decrease toward the edges. The electric field amplitude reaches its maximum when the main beam passes through the point (8000, 0, 0), and weakens at this point as the beam sweeps to either side. The behavior at points (8000, 4000, 0) and (8000, -4000, 0) also aligns with parallel dipoles. When the phase difference is -1.5708 rad, the electric field amplitude peaks at point (8000, 4000, 0) and reaches its minimum at point (8000, -4000, 0). Conversely, when the phase difference is 1.5708 rad, the electric field amplitude peaks at point (8000, -4000, 0) and reaches its minimum at point (8 0) is highest, while the amplitude at point (8000, -4000, 0) is lowest. Conversely, when the phase difference is 1.5708, the electric field amplitude at point (8000, -4000, 0) is highest, while the amplitude at point (8000, 4000, 0) is lowest.

Consistent with the parallel dipole artificial source,

Figure 32 also presents numerical simulations of CSAMT adaptive beamforming based on a coaxial dipole linear array artificial source under varying phase differences. As the phase difference transitions from -1.5708 rad to 1.5708 rad, the main beam progressively scans from point (8000, 0, 0) through point (8000, 0, 0) to point (8000, -4000, 0). (8000, 4000, 0), through point (8000, 0, 0), and gradually scans to point (8000, -4000, 0).

Figure 1.

Finite length dipole antenna, where .

Figure 1.

Finite length dipole antenna, where .

Figure 2.

Finite length dipole antenna, where .

Figure 2.

Finite length dipole antenna, where .

Figure 3.

Uniform linear array.

Figure 3.

Uniform linear array.

Figure 4.

Maximum ratio combination principle.

Figure 4.

Maximum ratio combination principle.

Figure 5.

Parallel vibrator linear array.

Figure 5.

Parallel vibrator linear array.

Figure 6.

CSAMT model of 3×1 parallel vibrator linear array.

Figure 6.

CSAMT model of 3×1 parallel vibrator linear array.

Figure 7.

Coaxial vibrator linear array.

Figure 7.

Coaxial vibrator linear array.

Figure 8.

3×1 CSAMT model of coaxial vibrator linear array.

Figure 8.

3×1 CSAMT model of coaxial vibrator linear array.

Figure 9.

Parallel dipole 3×1antenna array lumped port.

Figure 9.

Parallel dipole 3×1antenna array lumped port.

Figure 10.

In the side view of electric field amplitude, direction, three array element antennas are excited by the same phase (0 rad).

Figure 10.

In the side view of electric field amplitude, direction, three array element antennas are excited by the same phase (0 rad).

Figure 11.

In the side view of Poynting vector arrow, three array element antennas are excited by the same phase (0 rad).

Figure 11.

In the side view of Poynting vector arrow, three array element antennas are excited by the same phase (0 rad).

Figure 12.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the three antenna elements are excited by the Taylor synthesis and -1.5708 rad phase difference.

Figure 12.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the three antenna elements are excited by the Taylor synthesis and -1.5708 rad phase difference.

Figure 13.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the three antenna elements are excited by the Taylor synthesis and -1.0472 rad phase difference.

Figure 13.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the three antenna elements are excited by the Taylor synthesis and -1.0472 rad phase difference.

Figure 14.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the three antenna elements are excited by the Taylor synthesis and -0.5236 rad phase difference.

Figure 14.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the three antenna elements are excited by the Taylor synthesis and -0.5236 rad phase difference.

Figure 15.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the three antenna elements are excited by the Taylor synthesis and 0.5236 rad phase difference.

Figure 15.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the three antenna elements are excited by the Taylor synthesis and 0.5236 rad phase difference.

Figure 18.

Pattern of E planes, the three array element antennas are given amplitude Taylor synthesis and different phase excitation. The port phase of array element 1 is 0 rad, and the port phase of array element 2 is changed from -1.5708 to 1.5708 rad every 0.5236 rad. The change of the port phase of array element 3 is twice the change of array element 2.

Figure 18.

Pattern of E planes, the three array element antennas are given amplitude Taylor synthesis and different phase excitation. The port phase of array element 1 is 0 rad, and the port phase of array element 2 is changed from -1.5708 to 1.5708 rad every 0.5236 rad. The change of the port phase of array element 3 is twice the change of array element 2.

Figure 19.

Pattern of H planes, the three array element antennas are given amplitude Taylor synthesis and different phase excitation. The port phase of array element 1 is 0 rad, and the port phase of array element 2 is changed from -1.5708 to 1.5708 rad every 0.5236 rad. The change of the port phase of array element 3 is twice the change of array element 2.

Figure 19.

Pattern of H planes, the three array element antennas are given amplitude Taylor synthesis and different phase excitation. The port phase of array element 1 is 0 rad, and the port phase of array element 2 is changed from -1.5708 to 1.5708 rad every 0.5236 rad. The change of the port phase of array element 3 is twice the change of array element 2.

Figure 20.

3D far-field pattern. the left picture shows the situation when ph=-1.5708 rad, the right picture shows the situation when ph=1.5708 rad.

Figure 20.

3D far-field pattern. the left picture shows the situation when ph=-1.5708 rad, the right picture shows the situation when ph=1.5708 rad.

Figure 21.

3D far-field pattern. the picture shows the situation when ph=0 rad.

Figure 21.

3D far-field pattern. the picture shows the situation when ph=0 rad.

Figure 22.

Numerical simulation of CSAMT adaptive beamforming based on a parallel dipole linear array artificial field source with different ph.

Figure 22.

Numerical simulation of CSAMT adaptive beamforming based on a parallel dipole linear array artificial field source with different ph.

Figure 23.

Coaxial dipole 3×1 antenna array lumped port.

Figure 23.

Coaxial dipole 3×1 antenna array lumped port.

Figure 24.

Side view of electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, array antennas are excited by the same phase (0 rad).

Figure 24.

Side view of electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, array antennas are excited by the same phase (0 rad).

Figure 25.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the array antennas are excited by the Taylor synthesis and -1.5708 rad phase difference.

Figure 25.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the array antennas are excited by the Taylor synthesis and -1.5708 rad phase difference.

Figure 26.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the array antennas are excited by the Taylor synthesis and -1.0472 rad phase difference.

Figure 26.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the array antennas are excited by the Taylor synthesis and -1.0472 rad phase difference.

Figure 27.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the array antennas are excited by the Taylor synthesis and -0.5236 rad phase difference.

Figure 27.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the array antennas are excited by the Taylor synthesis and -0.5236 rad phase difference.

Figure 28.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the array antennas are excited by the Taylor synthesis and 0.5236 rad phase difference.

Figure 28.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the array antennas are excited by the Taylor synthesis and 0.5236 rad phase difference.

Figure 29.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the array antennas are excited by the Taylor synthesis and 1.0472 rad phase difference.

Figure 29.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the array antennas are excited by the Taylor synthesis and 1.0472 rad phase difference.

Figure 30.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the array antennas are excited by the Taylor synthesis and 1.5708 rad phase difference.

Figure 30.

In the side view of the electric field amplitude, direction and Poynting vector arrow, the array antennas are excited by the Taylor synthesis and 1.5708 rad phase difference.

Figure 31.

Pattern of E planes, the three array antennas are given amplitude Taylor synthesis and different phase excitation. The port phase of array antenna 1 is 0 rad, and the port phase of array antenna 2 is changed from -1.5708 to 1.5708 rad every 0.5236 rad. The change of the port phase of array antenna 3 is twice the change of array antenna 2.

Figure 31.

Pattern of E planes, the three array antennas are given amplitude Taylor synthesis and different phase excitation. The port phase of array antenna 1 is 0 rad, and the port phase of array antenna 2 is changed from -1.5708 to 1.5708 rad every 0.5236 rad. The change of the port phase of array antenna 3 is twice the change of array antenna 2.

Figure 32.

Numerical simulation of CSAMT adaptive beamforming based on coaxial dipole linear array artificial field source with different ph.

Figure 32.

Numerical simulation of CSAMT adaptive beamforming based on coaxial dipole linear array artificial field source with different ph.

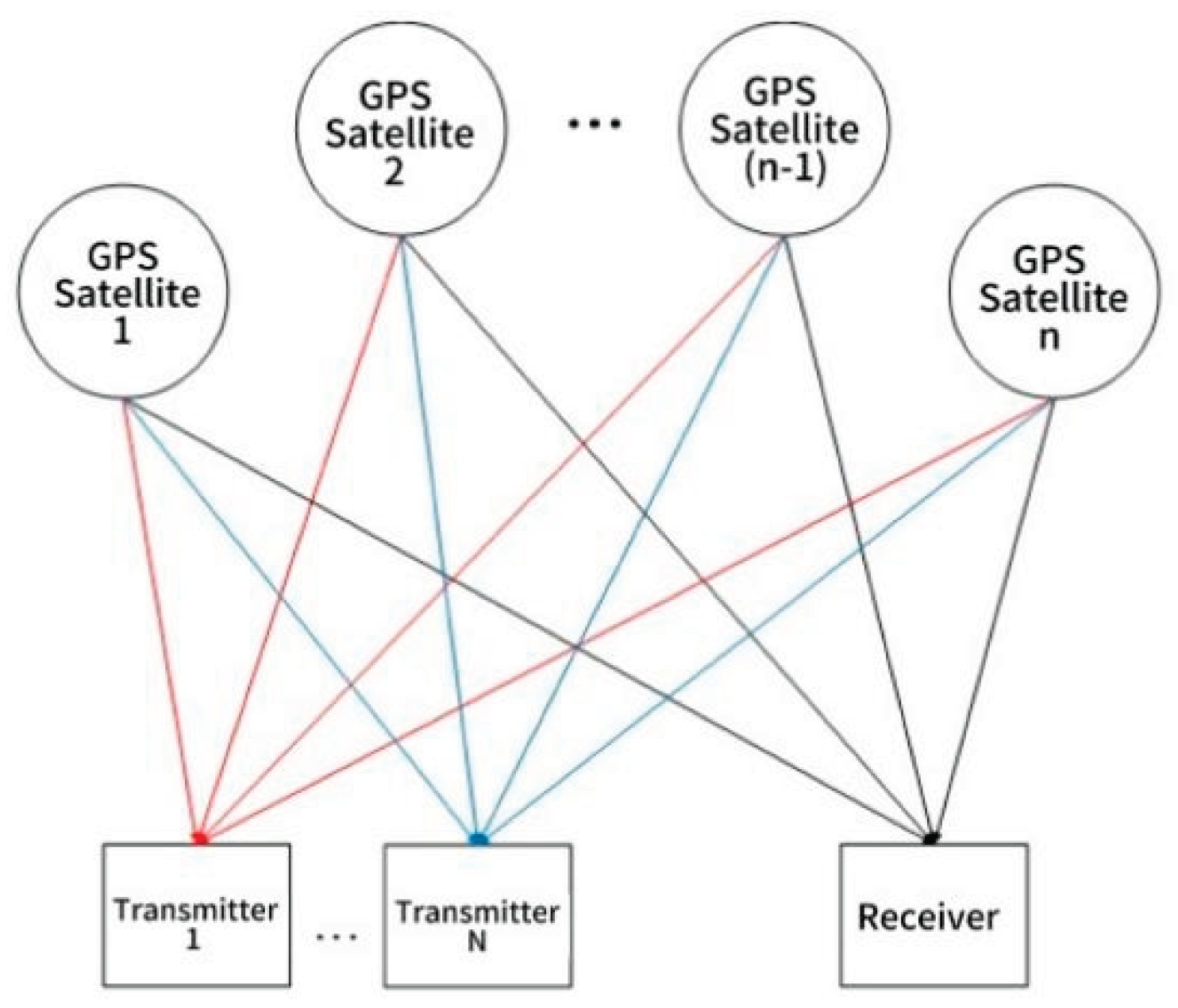

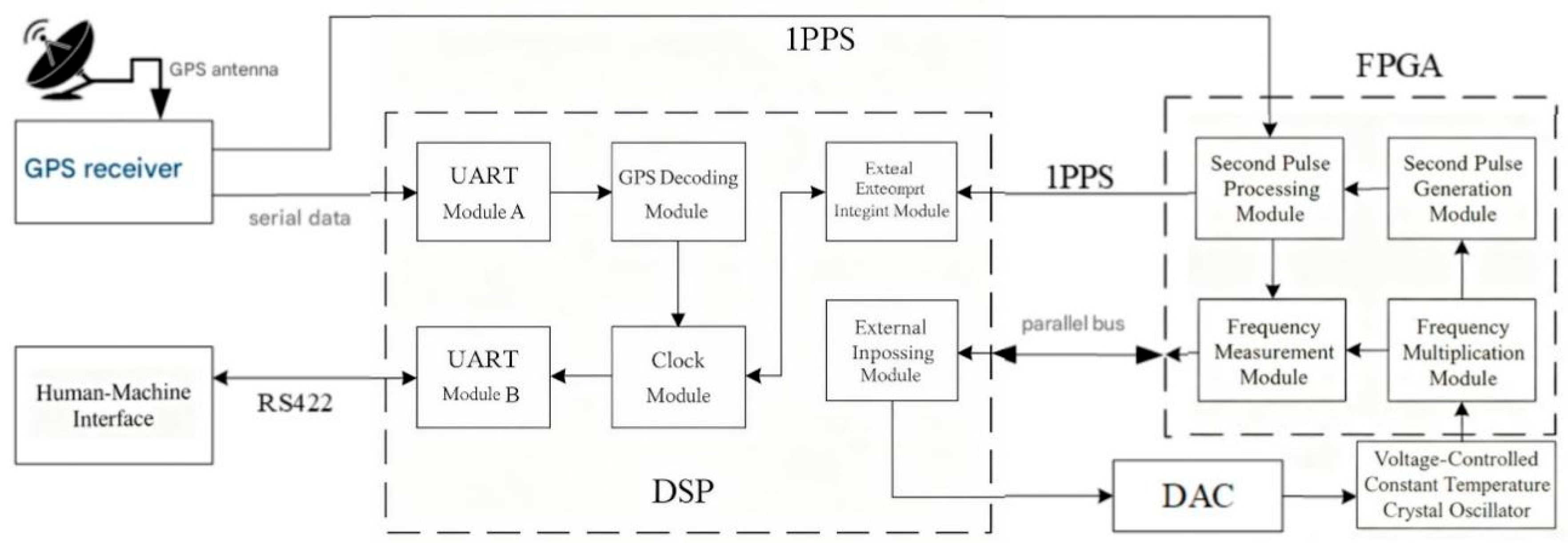

Figure 33.

GPS time synchronization diagram.

Figure 33.

GPS time synchronization diagram.

Figure 34.

The block diagram of GPS time synchronization.

Figure 34.

The block diagram of GPS time synchronization.

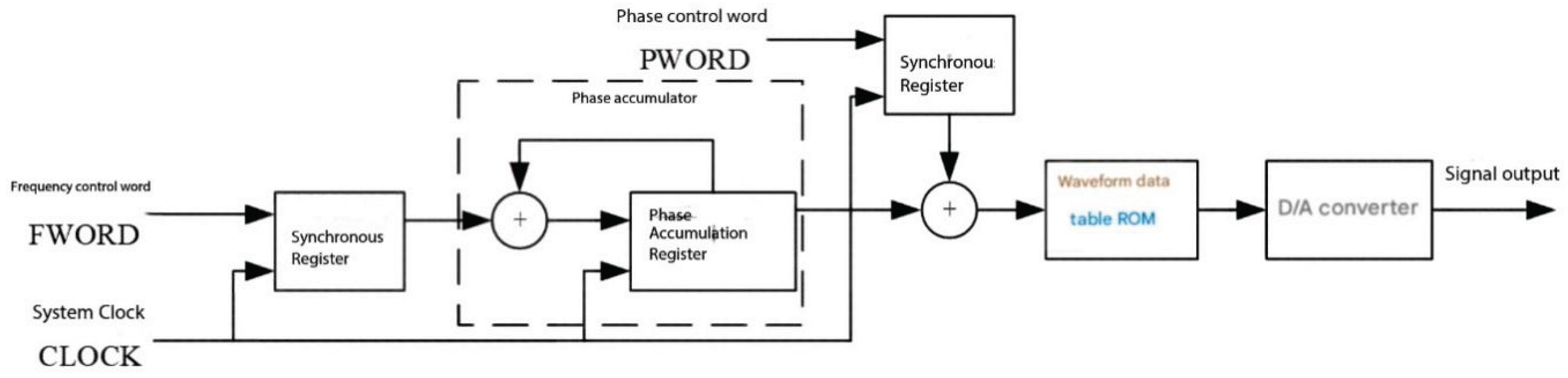

Figure 35.

Principles of DDS table lookup method.

Figure 35.

Principles of DDS table lookup method.

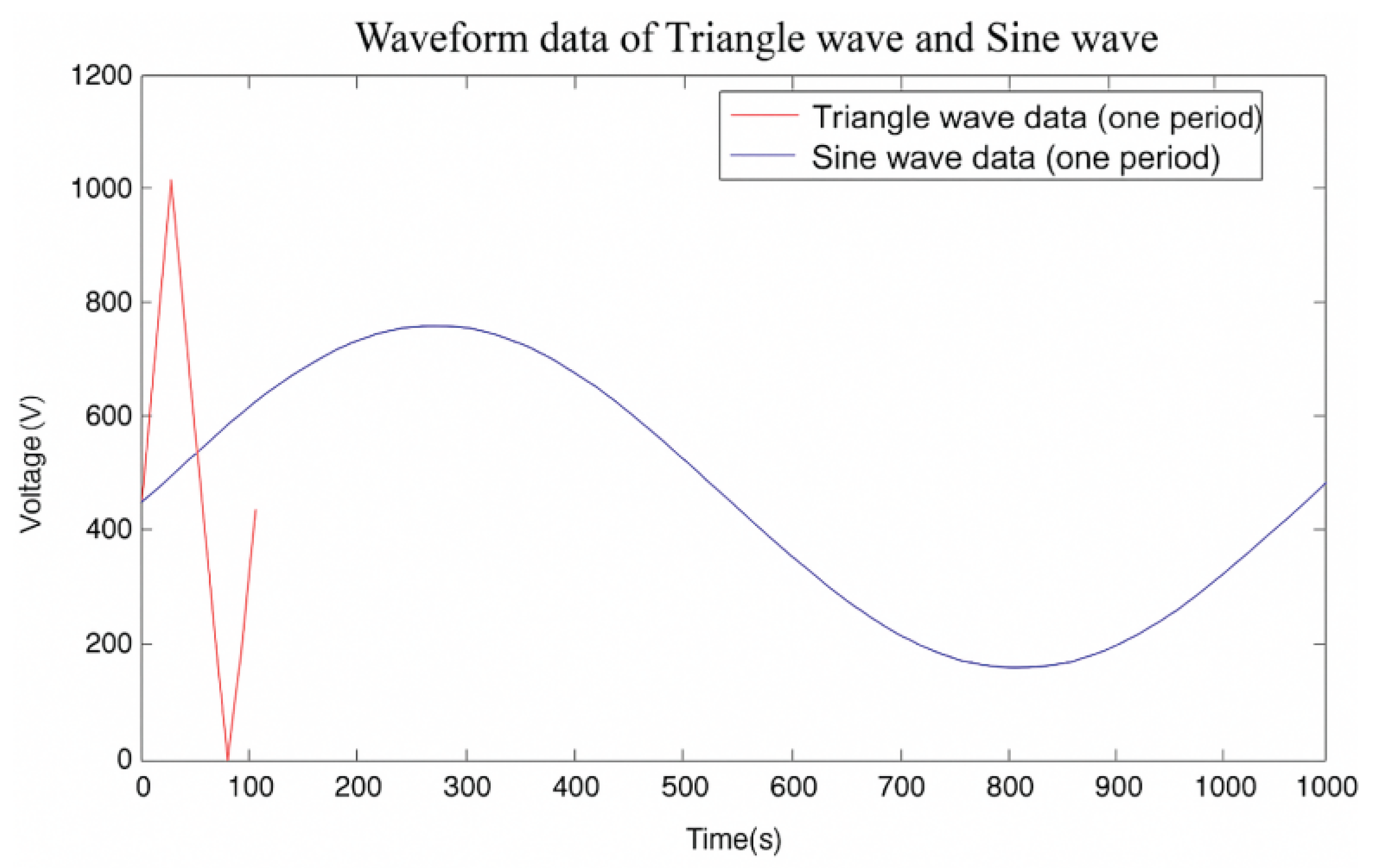

Figure 36.

Comparison of triangle carrier and sine wave.

Figure 36.

Comparison of triangle carrier and sine wave.

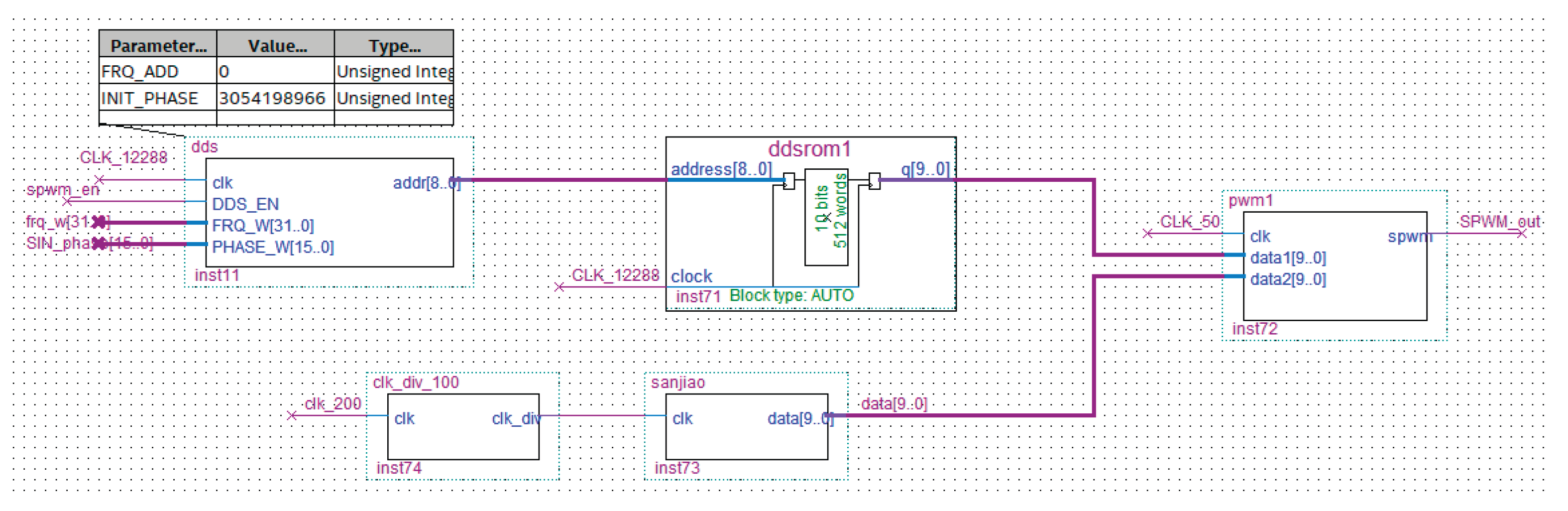

Figure 37.

FPGA implementation of DDS table lookup method.

Figure 37.

FPGA implementation of DDS table lookup method.

Figure 38.

Phase control system.

Figure 38.

Phase control system.

Figure 39.

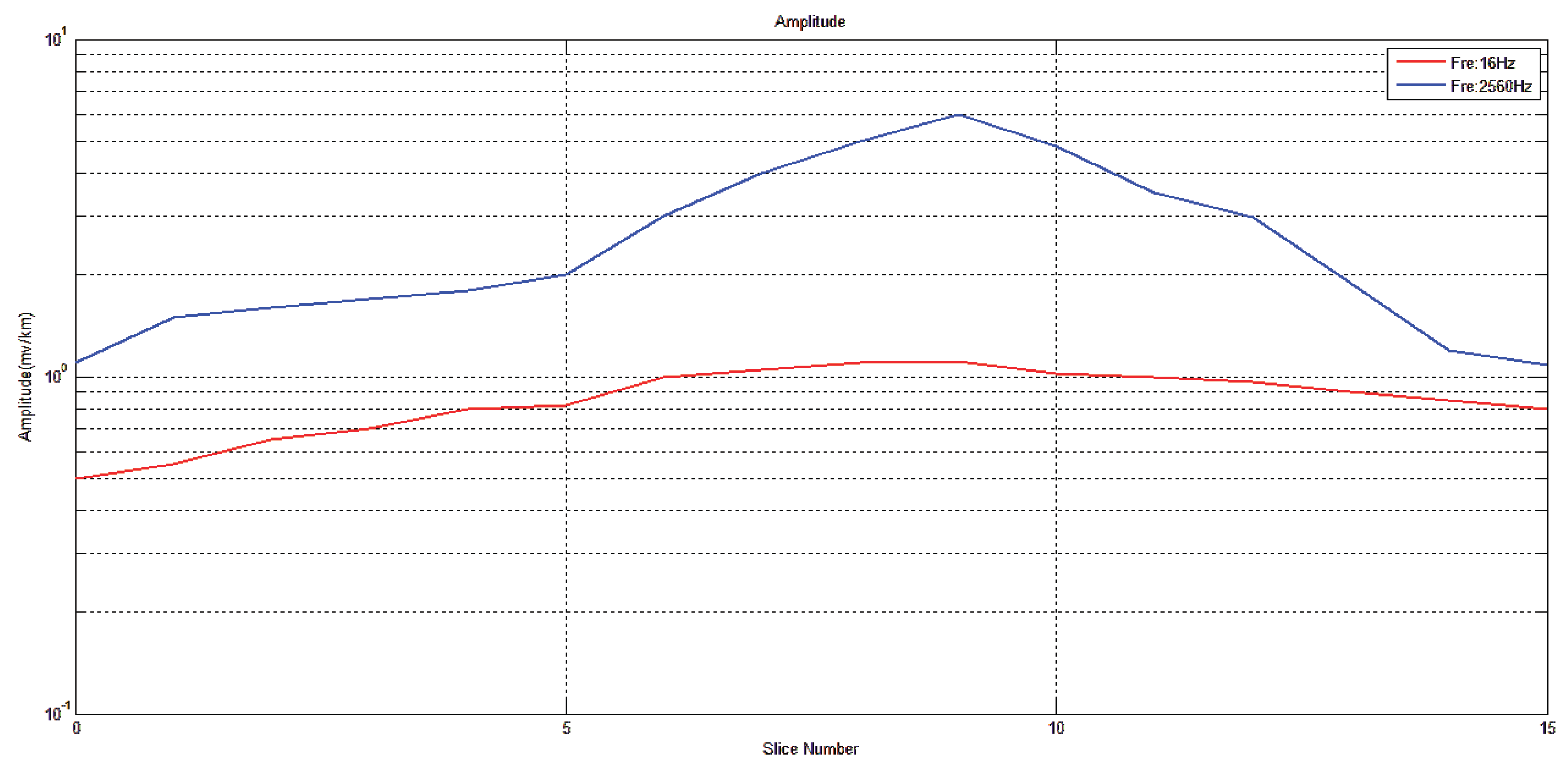

Adaptive beamforming measurement of parallel vibrator linear array artificial field source.

Figure 39.

Adaptive beamforming measurement of parallel vibrator linear array artificial field source.

Figure 40.

Coaxial adaptive beamforming measurement of parallel vibrator linear array artificial field source (at the coaxial adaptive measuring point).

Figure 40.

Coaxial adaptive beamforming measurement of parallel vibrator linear array artificial field source (at the coaxial adaptive measuring point).

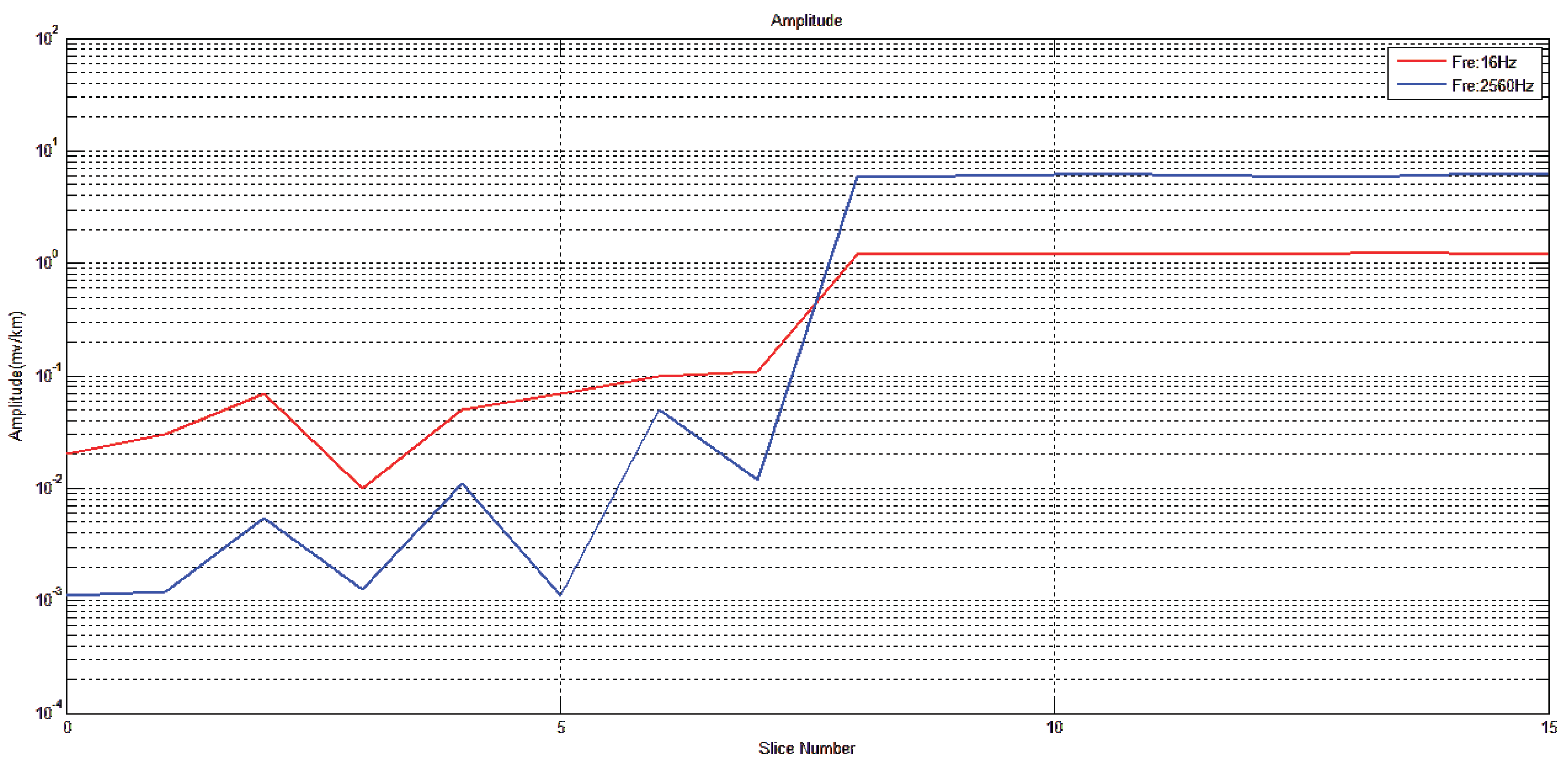

Figure 41.

Zero-zone adaptive beamforming measurement of parallel vibrator linear array artificial field source (at the zero-zone adaptive measuring point ).

Figure 41.

Zero-zone adaptive beamforming measurement of parallel vibrator linear array artificial field source (at the zero-zone adaptive measuring point ).

Figure 42.

Adaptive beamforming measurement of coaxial vibrator linear array artificial source.

Figure 42.

Adaptive beamforming measurement of coaxial vibrator linear array artificial source.

Figure 43.

Side beamforming measurement of coaxial vibrator linear array artificial field source (at the central measuring point).

Figure 43.

Side beamforming measurement of coaxial vibrator linear array artificial field source (at the central measuring point).

Figure 44.

Zero-zone beamforming measurement of coaxial vibrator linear array artificial field source (at the zero-zone measuring point).

Figure 44.

Zero-zone beamforming measurement of coaxial vibrator linear array artificial field source (at the zero-zone measuring point).

Table 1.

Arithmetic Pd for the different lumped ports, identified by their lumped port name.

Table 1.

Arithmetic Pd for the different lumped ports, identified by their lumped port name.

| Arithmetic Phase Difference |

Lumped Ports of a Parallel Dipole Linear Array |

| 0 [rad] |

Port1 |

| ph range(-1.5708, 0.5236, 1.5708 [rad]) |

Port2 |

| 2*ph [rad] |

Port3 |

Table 2.

Electric field values and F/B with different ph.

Table 2.

Electric field values and F/B with different ph.

| ph (rad) |

Electric field value (mV/km), at Point

(0, 8000, 0) |

Electric field value (mV/km), at Point

(0, -8000, 0) |

F/B (dB) |

| -1.5708 |

18.67×10-4 |

8.2892×10-4 |

3.52 (Forward) |

| -1.0472 |

16.366×10-4 |

8.6533×10-4 |

2.76 (Forward) |

| -0.5236 |

14.658×10-4 |

9.3276×10-4 |

1.96 (Forward) |

| 0 |

10.276×10-4 |

10.69×10-4 |

0.17 (Forward) |

| 0.5236 |

9.0404×10-4 |

14.156×10-4 |

1.94 (Backward) |

| 1.0472 |

8.4362×10-4 |

16.886×10-4 |

3.01 (Backward) |

| 1.5708 |

8.1602×10-4 |

18.189×10-4 |

3.48 (Backward) |

Table 3.

Numerical simulation of CSAMT adaptive beamforming based on parallel dipole linear array artificial field source with different ph.

Table 3.

Numerical simulation of CSAMT adaptive beamforming based on parallel dipole linear array artificial field source with different ph.

| ph (rad) |

Electric field value (mV/km), at Point

(8000, 0, 0) |

Electric field value (mV/km), at Point

(8000, -4000, 0) |

Electric field value (mV/km), at Point (8000, 4000, 0) |

| -1.5708 |

2.1298 |

0.6312 |

3.3316 |

| -1.0472 |

3.1206 |

0.9508 |

3.2979 |

| -0.5236 |

3.6039 |

1.5398 |

2.8721 |

| 0 |

4.8484 |

2.3173 |

2.1860 |

| 0.5236 |

3.6021 |

3.0439 |

1.4511 |

| 1.0472 |

3.1479 |

3.4953 |

0.8949 |

| 1.5708 |

2.2635 |

3.5314 |

0.5979 |

Table 4.

Arithmetic Pd for the different lumped ports, identified by their lumped port name.

Table 4.

Arithmetic Pd for the different lumped ports, identified by their lumped port name.

| Arithmetic Phase Difference |

Lumped Ports of a Coaxial Dipole Linear Array |

| 0 [rad] |

Port1 |

| ph range(-1.5708, 0.5236, 1.5708 [rad]) |

Port2 |

| 2*ph [rad] |

Port3 |

Table 5.

Numerical simulation of CSAMT adaptive beamforming based on coaxial dipole linear array artificial field source with different ph.

Table 5.

Numerical simulation of CSAMT adaptive beamforming based on coaxial dipole linear array artificial field source with different ph.

| ph (rad) |

Electric field value (mV/km), at Point (8000, 0, 0) |

Electric field value (mV/km), at Point (8000, -4000, 0) |

Electric field value (mV/km), at Point (8000, 4000, 0) |

| -1.5708 |

1.9291 |

0.5517 |

2.9344 |

| -1.0472 |

2.5216 |

0.8101 |

2.2929 |

| -0.5236 |

3.2138 |

1.3318 |

2.0724 |

| 0 |

4.1083 |

1.8112 |

1.7869 |

| 0.5236 |

3.2022 |

2.0434 |

1.3519 |

| 1.0472 |

2.4129 |

2.2937 |

0.8918 |

| 1.5708 |

1.9614 |

2.9317 |

0.4918 |