1. Introduction

Cognitive impairments primarily arise due to vascular risk factors and various forms of cerebrovascular pathology. According to recent data, vascular cognitive disorders account for at least 20–40% of all cases of dementia [

1]. In 2018, the number of people with dementia in the world was estimated around 50 million, and it is expected to triple by 2050. The prevalence of vascular cognitive impairments varies by country income levels: in low- and middle-income countries, the figures are still lower, but it is these countries that show the fastest growth in incidence. Hypertension, atherosclerosis, and other vascular risk factors are extremely common among elderly people, which is confirmed by numerous research data [

2]. All together, this explains an increase in the number of strokes, dementia, and their combined forms: approximately one in three people over 65 experiences at least one of these conditions.

This term (cognitive impairment) refers to a broad spectrum of dysfunctions, from mild cognitive decline to severe dementia [

3]. These conditions may be caused by ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, chronic exposure to vascular factors, and their combination with neurodegenerative processes, including Alzheimer's disease (AD) [

4].

Vascular cognitive impairments are caused by a variety of pathological processes: small vessel disease, atherosclerosis of large arteries, cerebral hemorrhages, pulmonary embolism. Such changes lead to impaired cerebral blood flow, hypoxia, dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier, inflammatory reactions and, as a consequence, the development of vascular dementia (VD) [

5]. Dysfunction of this system is viewed as a key mechanism contributing to the progression of cognitive deficit. A chronic reduction of cerebral blood flow may cause atrophy, white matter damage, lacunar strokes, microbleeds, which in turn are associated with deterioration of memory, attention and executive functions [

6]. The accumulation of ischemic lesions, even in asymptomatic cases, significantly increases the risk of developing dementia.

A chronic, age-associated dysregulation of cerebral blood flow appears to be a key pathophysiological mechanism underlying most vascular disorders [

7]. Also important are inflammatory processes, endothelial dysfunctions, and cardiovascular pathologies. Certain risk factors typical for middle age, such as arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and smoking, increase the probability of developing dementia by 20–40% [

8]. The combined impact of several risk factors increases this figure even more. Control of vascular risk factors, including by means of complex multimodal approaches with mandatory lifestyle changes, is currently viewed as the most promising strategy for the prevention and treatment of cognitive disorders.

Neurodegenerative diseases remain one of the most significant medical and social problems, which is due to their high prevalence, progressive course and a lack of effective treatment methods. More and more scientific evidence confirms the leading role of cerebrovascular pathology not only as an independent cause of cognitive decline, but also as a factor aggravating the course of neurodegenerative diseases [

9]. AD (senile dementia of the Alzheimer's type) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the irreversible deterioration of cognitive and physical functions. AD is the most common form of dementia in the world: according to various data, this neurodegenerative disease currently affects 25 to 40 million elderly people worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the prevalence of AD will increase three to four times by 2050 [

10]. AD is characterized by progressive memory loss, severe dementia (mental disability) and may become, according to WHO experts, one of the most likely causes of death in the 21st century.

Lifetime diagnosis of AD is difficult, since various forms of senility are often found in other neurodegenerative diseases, which complicates the timely targeted optimal treatment [

11]. Diagnosing a specific form of dementia as a manifestation of AD can be definitively confirmed only by a pathologist during an autopsy and brain examination using certain histochemical and immunohistochemical methods. The development of reliable methods for the

in vivo identification of AD biomarkers in a laboratory will allow to timely choose an appropriate method for pathogenetically justified therapy aimed at improving the patients’ psychosomatic condition and social orientation, and will also create a foundation for developing effective methods for the prevention of severe neurodegenerative pathologies [

5,

6].

Given their high prevalence and serious socioeconomic consequences, cognitive impairments are becoming one of the most important problems in modern medicine. Nowadays, prevention—early detection and correction of vascular risk factors using multimodal interventions—is considered the most effective approach.

The American Heart Association has proposed unified criteria for describing vascular cognitive impairments, encompassing the entire spectrum – from mild cognitive dysfunction to dementia [

14]. The search for biomarkers of VD and AD is fundamentally important for modern neuroscience and medicine in general. These diseases develop gradually, and their clinical manifestations become noticeable only when the pathological process has already gone too far. Biomarkers can help us identify changes at the preclinical stage, which opens up opportunities for early diagnosis, timely prevention, and more effective treatment.

The role of biomarkers in dementia diagnosis: accuracy, early identification, and new opportunities

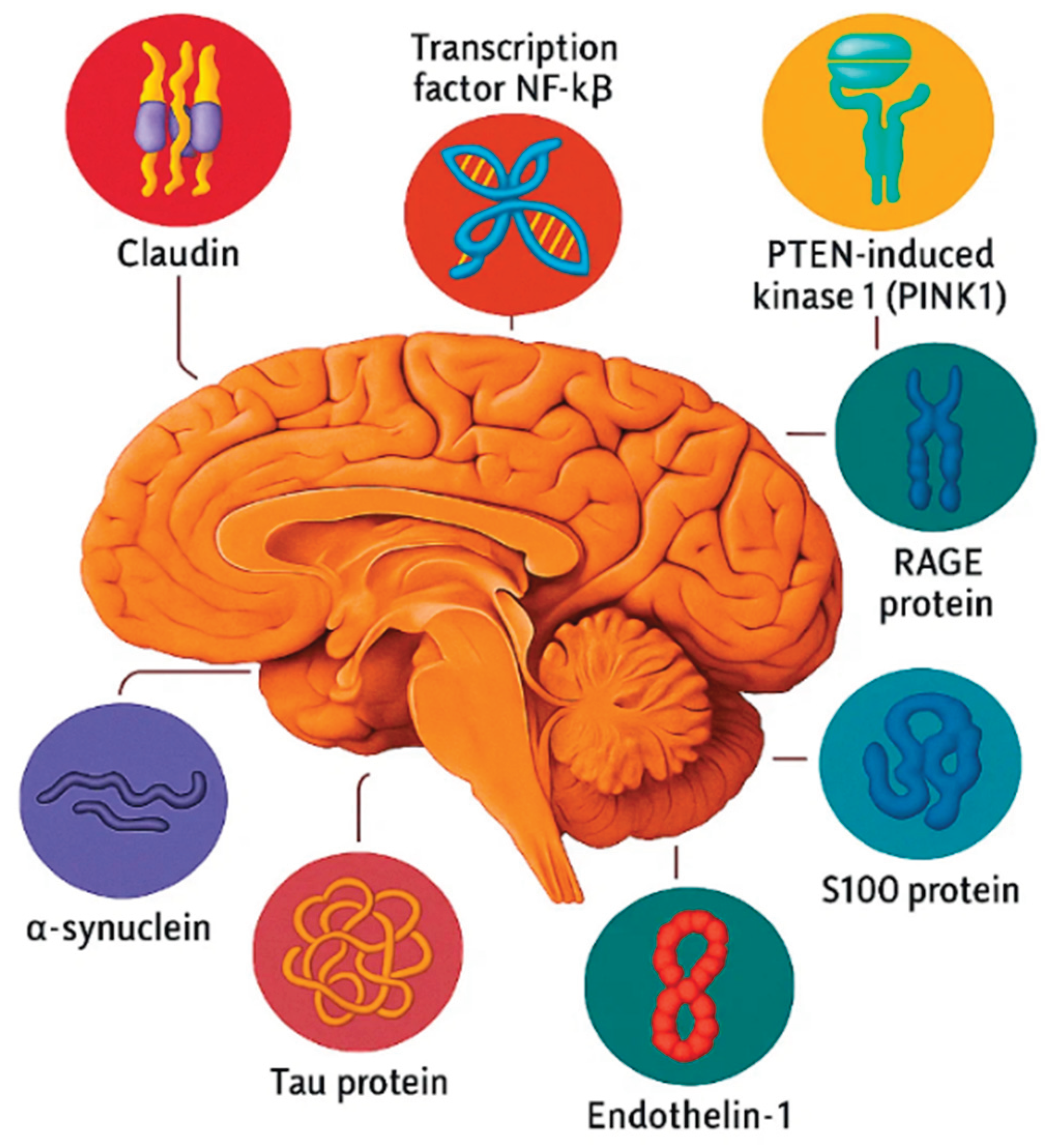

The particular value of biomarkers lies in their ability to differentiate between VD and AD, as the clinical symptoms of these diseases often overlap: impairments in memory, attention, and executive functions are observed in both conditions [

Figure 1]. However, these impairments differ in their nature: vascular dementia is characterized by ischemic lesions, white matter damage, microinfarctions, micro- and macrohemorrhages, and blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Currently, four molecules are considered to play a key role in the mechanism of AD onset and development: beta-amyloid, tau protein, ubiquitin, and acetylcholine. In its recommendations, the Alzheimer's Disease Consortium, established by the National Institute on Aging and the Reagan Institute (both in the United States), points out that abnormal metabolism of these molecules is a key component of the Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis [

15].

The use of biomarkers not only helps differentiate these pathologies but also predict the rate of cognitive decline progression. In AD, important markers include levels of β-amyloid, total and phosphorylated tau protein, and neurofilament light protein, which reflects neuronal damage. Key indicators of vascular dementia include white matter hyperintensities on MRI, the presence of microinfarctions, micro- and macrohemorrhages, structural vascular changes, and vascular stiffness markers [

1,

16]. It is also important to note that a significant part of patients experience mixed dementia, where vascular and neurodegenerative mechanisms overlap, and in such cases the combined use of biomarkers from both groups helps most accurately assess the nature of the pathology.

An equally important area is the use of biomarkers for monitoring the treatment effectiveness. In AD clinical trials, they are used to track the dynamics of amyloid and tau protein deposition under the influence of new anti-amyloid medications [

17]. In the case of vascular dementia, monitoring biomarkers allows to assess the impact of antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapy, as well as non-pharmacological interventions, including lifestyle changes, on cerebral circulation and cognitive function.

Finally, the integration of biomarker data with genetic risk factors, such as APOE4 allele status, and with evaluating the patient's vascular health can provide the basis for personalized medicine. This approach offers individualized preventive measures and therapeutic strategies, which is particularly important in view of the high prevalence of cognitive impairments in old age. The search for and validation of biomarkers for VD and AD is a prerequisite for progress in early diagnosis, disease differentiation, prognosis, and the development of effective and personalized treatment and prevention strategies.

In the context of AD, a major cause of dementia, searching for biomarkers is focused on key pathological processes: the accumulation of beta-amyloid (Aβ) and hyperphosphorylated tau protein. The amyloid hypothesis postulates that impaired Aβ catabolism, especially an elevated Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, leads to the formation of neurotoxic oligomers and fibrils that form senile plaques, which triggers a pathological cascade of events [

18].

β-amyloid

The 40-amino acid extracellular protein is the most common form of β-amyloid (Aβ), accounting for up to 90% in the brain of healthy individuals and up to 40% in the brain of individuals with AD. However, mutations in the

APP (amyloid precursor protein) gene promote the accumulation of Aβ with 42 amino acid residues (Aβ42), which is the most aggregation-prone form. The Aβ42 accumulation leads to the formation of amyloid oligomers, which, in turn, also aggregate and participate in the formation of senile plaques [

19].

It has been found that Aβ42, which is considered the most toxic amyloid, predominates in brain tissues in patients with AD. Initially, aggregating Aβ was believed to form senile plaques in the brain, causing disruption of synaptic transmission, neuronal death, and, consequently, the development of dementia. Yet, the amyloid hypothesis could not explain the fact that the number and size of senile plaques in the brain of AD patients does not correlate with the degree of cognitive impairment. Moreover, some individuals without AD symptoms have extensive Aβ deposits, while some patients with inherited AD (IAD) have no senile plaques at all [

7].

The degree of cognitive impairment in AD has been found to correlate with the biochemically verified amount of Aβ, but not with the histologically determined amount of Aβ. Soluble forms of Aβ remain invisible during immunohistochemical analysis. Probably, it is oligomers, rather than senile plaques, that are most toxic to neurons and cause pathological changes in AD patients.

Research findings in this area have led to a revision of the “amyloid hypothesis,” which has come to be called the “toxic oligomer hypothesis.” This new version of the amyloid hypothesis asserts that the accumulation of toxic Aβ42, aggregated in oligomeric assemblies, triggers a complex set of processes at the molecular and cellular levels, which ultimately leads to neuronal dysfunction and apoptosis.

Amyloid oligomers have been shown to impair the effect of long-term potentiation (LTP). LTP is a specific function of the nervous system enhancing the synaptic transmission between neurons and persisting for a long time after the synapse is affected. LTP underlies synaptic plasticity, an ability of the nervous system to adapt to changing environment conditions. It is widely believed that LTP plays a leading role in memory and learning processes.

Synaptic dysfunction, reduced LTP effects, and subsequent memory loss in early AD may be partially induced by amyloid oligomers, which disrupt synaptic remodeling and short-term memory formation.

Amyloid oligomers have been shown to cause oxidative stress and pathological changes in the endoplasmic reticulum, increasing the sensitivity of neurons to excitotoxicity—a pathological condition resulting in the suppression and death of neurons due to hyperactivation of glutamate receptors. Excitotoxicity is considered a cause of neuronal death in neurodegenerative diseases. Although this data supports the amyloid cascade hypothesis, their prevalence rate is around 1%. Is should be noted, however, that the data supporting the amyloid cascade hypothesis was obtained in animal models of AD [

20].

Tau protein

Tau protein (τ protein) is a protein associated with microtubules which are essential for axon growth. Normally, τ protein interacts with tubulin, facilitating its assembly into microtubules and stabilizing their structure. Tau protein knockout mice have been found to develop progressive motor dysfunction with age [

17].

Neurofibrillary pathologies associated with τ protein are found in the development of more than 20 neurodegenerative diseases. Hyperphosphorylated τ protein can spontaneously aggregate into paired helical filaments to form neurofibrillary tangles. In AD, hyperphosphorylated τ protein accumulates, which results in its dissociation from microtubules, destabilizing them, and leading to disruption of neuronal transport.

The number of neurofibrillary tangles correlates with the degree of disease progression but does not correspond to the degree of neuronal loss, as, according to experimental data, memory loss and neuronal death precede the formation of neurofibrillary tangles [

20].

Some authors believe that it is τ-protein oligomers, rather than senile plaques, that exert a cytotoxic effect on neurons and are the predominant cause of AD development. Impairment in learning and memory processes has been observed to increase with increasing τ-oligomer levels in AD. Synapse loss and microglial activation precede the formation of neurofibrillary tangles, reflecting disruptions in axonal transport which occur as a result of τ-protein hyperphosphorylation [

21].

It is argued that in the case of familial Alzheimer disease (FAD), τ-associated pathology should not be considered a downstream link in the amyloid cascade, and that the development of AD, according to the amyloid cascade hypothesis and in the case of tau-associated pathology, follows two independent pathways. Tau-protein hyperphosphorylation first occurs in the brainstem (in the locus coeruleus region), then spreads to the medial temporal lobe, limbic structures, and association and primary cortex. The amyloid formation begins in the association cortex and then develops in the lower regions of the cortex, the brainstem, and the cerebellum [

22].

Ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small, highly conservative peptide contained in all eukaryotic cells, which is conjugated to proteins that are to be targeted at the proteasome. This process occurs in three steps. First, an ubiquitin monomer is activated in an ATP-dependent reaction by the ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1). Next, ubiquitin is transported to the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2). And finally, ubiquitin is transported to the target protein by ubiquitin ligase (E3).

The E3 ligase binds the target protein and the E2-ubiquitin complex, facilitating the formation of a covalent bond between the ubiquitin monomer from the E2 enzyme and the target protein. Activated ubiquitin molecules are successively attached to the first ubiquitin proteins, forming a polyubiquitin chain. Proteins tagged with chains of four or more ubiquitins are recognized by the 26S proteasome for degradation. It is the E3 ligase that imparts specificity to the process, selectively binding to the target protein. Ubiquitin monomers are released after proteasomal degradation or actively removed by ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolases.

Growing evidence confirm that changes in the UPS function may be involved in the AD pathogen process [

23]. This standpoint is supported by data confirming that ubiquitin accumulates in both plaques and tangles in AD. Moreover, these structures have been shown to contain a mutant ubiquitin-B protein (UBB+1), mutant ubiquitin carrying a 19-amino acid C-terminal extension formed by a transcriptional dinucleotide deletion.

Remarkably, UBB+1 has been found to inhibit ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis in neuronal cells, inducing the formation of mitochondrial neuritic beads in association with neuronal differentiation, and it is suggested to be a mediator of Aβ-induced neurotoxicity [

23].

Alpha-synuclein

Alpha-synuclein is a small neuronal protein located mostly in presynaptic terminals. It is detected in various parts of the brain, primarily in the neocortex, hippocampus, and substantia nigra. It is also present in other brain cells—astrocytes and oligodendrogliocytes.

Alpha-synuclein accounts for approximately 1% of the total soluble protein pool in the brain. Alpha-synuclein is also found in other cell types, such as blood cells.

The gene encoding the alpha-synuclein protein (SNCA) is located on chromosome 4 (locus 4q21) and consists of six exons, five of which are transcribed. Alternative splicing produces three protein isoforms (140 amino acids, 126 amino acids, and 112 amino acids), of which the 140 isoform is the major one [

24].

A protein called alpha-synuclein was initially detected in stingray electroreceptors in screening for synaptic proteins. Human alpha-synuclein was first isolated from amyloid deposits in the frontal cortex of individuals with typical clinical and neuropathological manifestations of Alzheimer's disease. Alpha-synuclein was later found to be a major component of Lewy bodies in Parkinson's disease (PD).

The major isoform of alpha-synuclein (140 amino acids, 19 kDa) consists of an amino-terminal region containing several repeats of amino acid sequences (KTKEGV), the hydrophobic central region known as the non-amyloid component (NAC), and the negatively charged acidic C-terminal region. The C-terminal region contains several phosphorylation sites (Tyr-125, -133, -136, and Ser-129), as well as a domain responsible for alpha-synuclein chaperon activity (bases 125–140).

The N-terminal region is very similar to the lipid-binding domain of apolipoproteins, which suggests that alpha-synuclein can interact with the lipid membrane raft. It has been shown to interact with the vesicular membrane containing phospholipids. It is believed that the nucleus accumbens (NAc) is responsible for its fibrillization, while the C-terminal region (bases 96-140) has an inhibitory effect on fibril formation.

Alpha-synuclein is thought to exists in two equilibrium states in the cell: native and membrane-bound. In its native form, it is a soluble, unfolded protein with a weakly ordered or completely disordered structure, lacking a definite spatial organization.

Alpha-synuclein binding to membranes is followed by conformational transition to an alpha helix. Alpha-synuclein is a protein capable of aggregation. An increased concentration of alpha-synuclein in solution leads to the formation of fibrils and discrete spherical structures similar to those present in Lewy bodies.

Some hypothetical functions of alpha-synuclein have been described so far, but the exact physiological significance of this protein remains unknown. The protein's localization in presynaptic terminals and its ability to interact with membranes suggest that it is involved in the regulation of neuronal vesicular transport.

Vesicle pool depletion in hippocampal synapses observed in SNCA knockout mice allowed to suggests alpha-synuclein involvement in maintaining the presynaptic vesicle pool.

It has also been shown that alpha-synuclein can affect intracellular dopamine amount through direct interaction with proteins that regulate its synthesis and reuptake. By regulating the amount of dopamine transporter in the plasma membrane, alpha-synuclein may act as a regulator of dopamine toxicity by controlling dopamine entry into and exit from the cell.

Alpha-synuclein has been found to affect dopamine synthesis by inhibiting the rate-limiting enzyme in synthesis of dopamine tyrosine hydroxylase. Interestingly, SNCA knockout mice do not exhibit significant CNS dysfunction and show no signs of neurodegeneration. Only a triple knockout of alpha-, beta-, and gamma-synuclein genes is accompanied by changes in the synaptic structure, impaired neurotransmission, and age-related neurodegeneration. This observation suggests that the neurodegeneration mechanism in PD may not be related to the loss of alpha-synuclein activity. Overexpression of alpha-synuclein in transgenic mice results in reduced dopamine release and synaptic dysfunction.

As noted above, the amplification of the normal SNCA gene sequence, resulting in increased intracellular alpha-synuclein levels, is sufficient for the development of PD. The disease onset age and severity correlate with the number of gene copies. Alpha-synuclein filaments appear to be the main ultrastructural component not only of Lewy bodies in PD associated with SNCA amplification, but also in sporadic PD and other synucleopathies.

In particular, these protein aggregates were identified in Lewy bodies, which are found in neurons of patients with Lewy body dementia and in glial cytoplasmic inclusions that form in oligodendrocytes in patients with multiple system atrophy.

Allelic variants in the promoter region of the SNCA gene, associated with increased gene expression, increase the risk of developing PD. Furthermore, three independent genome-wide scanning studies have found an association of the SNCA gene locus with an increased PD risk. Alpha-synuclein neurotoxicity has been convincingly confirmed by the creation of transgenic animals (Drosophila, mice) based on overexpression of the human SNCA gene, which exhibit neuronal alpha-synuclein-positive inclusions and the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the brain. The neurotoxicity of alpha-synuclein aggregates has also been repeatedly demonstrated

in vitro [

13].

The ability of alpha-synuclein to form fibrils in vitro, similar to those observed in Lewy bodies, and the fact that the A53T mutation accelerates fibril formation, suggest that alpha-synuclein polymerization may be directly associated with the pathogenesis of PD.

Despite a lot of data pointing to the pathogenic role of fibrillar alpha-synuclein in cells, the mechanisms of fibril toxicity remain unknown.

For the time being, the prevailing hypothesis is that it is not alpha-synuclein fibrils themselves that are toxic, but rather certain intermediates (called protofibrils) which appear in the process of their formation. Protofibrils are small oligomers that have a p-pleated structure. Two types of protofibrils have been observed in vitro: spherical or ring-shaped protofibrils and tubular protofibrils.

Interestingly, post-translational modifications of alpha-synuclein (oxidation, phosphorylation, nitrosylation) enhance its ability to form aggregates. It has been shown that alpha-synuclein found in Lewy bodies is predominantly phosphorylated at Ser129. The mechanisms of neurotoxicity of alpha-synuclein protofibrils are unclear. It has been suggested that protofibrils can form pores capable of building into the membrane, altering its permeability and, consequently, cellular homeostasis. Recent findings point to prion-like properties of alpha-synuclein.

The ability of alpha-synuclein and its aggregates to be secreted and subsequently taken up by neighboring cells has been demonstrated. It is hypothesized that exogenous fibrillar alpha-synuclein may further act as a site for aggregation of soluble monomeric protein. The above discussed data supports the hypothesis of the neurotoxicity of fibrillar forms of alpha-synuclein and their role in the pathogenesis of PD, but a precise mechanism of neurodegeneration remains unknown.

DRP1

The involvement of DRP1 in mitochondria and its role in maintaining their shape, size, and distribution appear to be crucial for normal cellular functioning. Electron and confocal microscopy, gene expression analysis, and biochemical methods have helped to demonstrate that neurons from samples treated with Aβ alone exhibit increased expression of DRP1 and Fis1 (fission genes) and decreased expression of Mfn1, Mfn2, and Opa1 (fusion genes), which suggests abnormal mitochondrial dynamics in brain neurons in AD patients [

20].

Several research groups have reported that impaired mitochondrial dynamics is associated with abnormal DRP1 expression in postmortem brains of AD patients, AD mouse models, and APP cell lines. Mitochondrial abnormalities in AD have been studied by Hiraiet et al. [

26] using

in situ hybridization with mtDNA, immunocytochemistry, and of electron micrograph morphometry of biopsy specimens from AD patients. They found that the same neurons exhibiting increased oxidative damage in AD had a striking and significant increase in mtDNA and cytochrome oxidase.

Remarkably, the mtDNA and cytochrome oxidase were predominantly found in the neuronal cytoplasm and in lipofuscin-associated vacuoles, which points to the existence of mitochondrial abnormalities and autophagosomes in neurons from AD patients.

There is evidence of abnormal mitochondrial dynamics in primary neurons from AβPP transgenic mice, in brain tissue of transgenic mice (Tg2576 mice) and in brain tissue from AD patients (autopsy), as well as in neuroblastoma cells treated with Aβ peptide.

Markers of vascular dementia: endothelin-1 and CD34 protein

Endothelin is a biologically active bicyclic polypeptide with a broad spectrum of activity. Today, endothelin is considered one of the most significant regulators of the functional state of vascular endothelium. Information about endothelin as a vasomotor activity factor first appeared in 1985, when a group of researchers led by Hickey studied cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells. They succeeded in purifying this factor and determining the amino acid sequence of the peptide, which consisted of 21 amino acid residues with four cysteine bridges in the form of disulfide bonds and with a molecular weight of 2492 Da.

The extracted factor was named endothelin, and in 1988 an article was published on a peptide that is produced by endothelial cells and has a powerful vasoconstrictor effect. This important discovery was followed by numerous experimental studies using endothelin [

27].

However, when the first research results began to appear, it became clear that the mechanism of this peptide action was not as simple as it was initially thought.

A year later, intensive research led to the discovery of three endothelin isoforms: endothelin-1, endothelin-2, and endothelin-3. It was found out that all these isoforms consist of 21 amino acid residues, and their synthesis is encoded by three different genes present only in vertebrates, which enables scientists to trace the evolution of endothelins. Moreover, endothelin-2 has a homology very similar to that of endothelin-1 and structurally differs by only two amino acid residues [

27].

The polypeptide is known to be produced by endothelial cells as a precursor (preproendothelin), which is then converted into big-endothelin through cleavage of oligopeptide fragments. Big-endothelin consists of 39 amino acid residues. Endothelin-1 is formed with involving an endothelin-converting enzyme, which is localized inside and on the surface of the endothelium. In this process, the vasomotor activity of endothelin-1 increases by 140 times, and its half-life is shortened. The half-life of endothelin-1 lasts from 40 seconds to 4–7 minutes, and a larger part of endothelin (80%) is inactivated while passing through the pulmonary vessels.

Endothelin-1 is the most common member of the endothelin family and the most potent vasoconstrictor, 10 times more powerful than angiotensin II, and its effect is 100 times higher than that of noradrenaline [

28].

Amino acid sequencing revealed that this protein has a strong similarity to a toxic component of the venom of spiders and some snakes. In particular, a peptide (sarafotoxin) derived from the venom of the Atractaspis engaddensis snake has structural and functional similarities to endothelins. When sarafotoxin is released into victim's bloodstream, it causes coronary spasm, which may result in cardiac arrest.

However, there are minor differences in the chemical structure of the venom and endothelin, which are significant for understanding the binding of ligands to endothelin receptors.

Endothelin-1 is predominantly produced in endothelial cells and, unlike other endothelins, can be synthesized in underlying vascular smooth muscle cells, neurons, astrocytes, endometrium, hepatocytes, mesangiocytes, Sertoli cells, mammary endothelial cells, and tissue basophils.

Endothelin-2 is found in the kidneys, intestine, myocardium, placenta, and uterus. Endothelin-3 is localized in the brain, intestine, kidneys, and lungs. Endothelin-1 does not accumulate in endothelial cells, but is rapidly formed under the impact of adrenaline, angiotensin II, vasopressin, thrombin, cytokines, and mechanical action.

In a few minutes, mRNA transcription is activated and endothelin precursors are synthesized, followed by their conversion to endothelin-1 and subsequent secretion. At the same time, catecholamines, angiotensin II, high-density lipoproteins, growth factors, thrombin, thromboxane A2, Ca2+ ionophore, and phorbol ester activate intracellular mechanisms of endothelin-1 synthesis, bypassing cell membrane receptors by influencing protein kinase C and releasing Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Hypoxia in some tumors also leads to endothelin production, which, in turn, results in disease progression.

The concentration of endothelin-1 in human blood plasma is normally 0.1–1 fmol/ml or undetectable. It is the concentration level that determines what effect (relaxation or contraction) will be produced. At low concentrations, endothelin acts on endothelial cells in an autocrine/paracrine manner, releasing relaxation factors, while an increased concentration activates receptors on smooth muscle cells in a paracrine manner, leading to vascular spasm. One of the most significant regulators of endothelin production in endothelial cells is the transforming growth factor (TGF-β), which increases the production of preproendothelin [

28].

As far as we now know, the vasoconstrictor effect, increased heart rate and contractility (chronotropic and inotropic effects) of endothelin-1, as well as potentiating tissue growth and differentiation, are realized through the activation of two types of receptors: ETA and ETB. ETA has a high affinity for endothelin-1 and endothelin-2. ETB does not act preferentially, but it does have two subtypes: ETB1 and ETB2. About ten years ago, another type of endothelin receptor, ETC, was identified. Its structure and role are not yet fully understood. However, endothelin-3 is believed to act through ETC receptors.

Receptor subtypes are differently localized in the vascular system: ETA is found in vascular smooth muscle cells, cardiomyocytes, brain tissue, and the gastrointestinal tract. ETB is found in smooth muscle cells, coronary vessels, cardiomyocytes, juxtaglomerular cells, and the ileum.

Gender also plays a significant role. It has been proved that ETA activation is increased in males, while ETB activation has been observed in females. The vascular lumen diameter is significant too. ETA is expressed in small-diameter vessels, while ETB is predominately expressed in coronary arteries and pulmonary vessels. The different localization of the receptors allows us to explain a large amount of effects associated with endothelin function under normal and pathological conditions.

5. S100 Protein

The S100 protein was first described in 1965 as a fraction of neuroglial proteins produced primarily by astrocytes in the brain. The cerebral S100 protein is a combination of two closely related proteins of the family: S100A1 (S100α) and S100B (S100β).

By 2004, 20 members of the S100 family (intracellular calcium-sensor and calcium-binding proteins with molecular weights of 10–12 kilodaltons) had been discovered.

Of the 20 genes that encode the synthesis of S100 proteins in humans, 16 are located in the q21 region of chromosome 1. These genes are designated S100A (1, 2, ..., 16). The S100B gene is located in the q22 region of chromosome 21.

S100 family proteins exist as dimers inside the cell. So, S100A1 and S100B in the brain form homodimers S100A12 and S100B2, as well as heterodimers S100A1/S100B [

32].

Due to their ability to regulate the activity of a wide range of proteins, S100A1 and S100B are involved in the transduction of signals that control the activity of energy metabolism enzymes in brain cells, calcium homeostasis, the cell cycle, cytoskeletal functions, transcription, cell proliferation and differentiation, cell motility, secretory processes, and the structural organization of biomembranes.

However, the most unusual characteristic of some members of the S100 family is their ability to be secreted extracellularly. S100 proteins in the extracellular sector manifest cytokine properties and interact with RAGE receptors, which are expressed in the nervous system by neurons, microglia, astrocytes, and vascular wall cells [

15].

Research findings over the past decade have demonstrated that glial cells not only provide structural support and nutrition for neurons but also interact intensively with them. Due to the presence of ion channels, as well as receptors for neurotransmitters and other signaling molecules in their distal parts, astrocytes are able to detect changes in neuronal activity and respond to them by increasing cytosolic calcium concentrations and generating calcium waves.

The calcium signal is then realized (possibly with the direct involvement of the S100 protein) into gene expression modulation, changes in astrocyte morphology, and the secretion of some neuroactive molecules, such as glutamate, D-serine, ATP, taurine, neurotrophins, and cytokines.

Astrocytes perform a wide range of adaptive functions, including neurotransmitter reuptake, contributing to damage repair, and regulating synaptic density. These findings provide evidence that glia-neuronal reciprocal signaling, functional and structural plasticity play a major role in the functioning of neuronal networks and information transmission/processing processes in the nervous system during its formation, functioning, and reparation. One of mediators in neuron-glial and glia-glial interactions is S100B, which is secreted by glial cells [

32].

As in many biologically active molecules, the effects of extracellular S100B are dose-dependent. At nanomolar concentrations, S100B exerts an autocrine effect on astrocytes, stimulating their proliferation in vitro, while the S100B2 dimer modulates long-term synaptic plasticity and exerts a trophic effect on both developing and regenerating neurons.

At micromolar concentrations, extracellular S100B (in its homo- and heterodimeric forms) can exert neurotoxic effects on neurons and glia, inducing both cell apoptosis and cell necrosis. The latter effect is based on the ability of S100B to independently induce proinflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress enzymes, particularly iNOS, and to enhance other signals directed at neurons and glial cells.

Thus, the S100B protein can enhance the expression of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in microglia and neurons, which may result in pathological changes in neuronal properties, particularly hyperphosphorylation of tau protein, decreased levels of certain synaptic proteins, and increased synthesis and activity of acetylcholinesterase. S100B also increases the expression of the β-amyloid precursor peptide (APP) and its mRNA in neuronal cultures and enhances β-amyloid peptide-induced activation of astrocytes. In turn, both IL-1 and β-amyloid induce S100B expression, thus perpetuating a vicious cycle of potentiating the neurotoxic effects of S100B.

S100B-induced enhanced APP expression and iNOS activation may contribute to the spreading of inflammatory activation and neurodegeneration, as the β-amyloid peptide can be secreted and nitric oxide (NO) can diffuse. NO, in turn, can trigger the synthesis and release of other neurotoxic molecules from astrocytes, such as IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α).

Many studies have tried to find a link between chronic glial activation (astrocytes and microglia) and subsequent progressive cycles of neuroinflammation, autoimmune reactions, neuronal dysfunction, and neurodegeneration in AD.

There are numerous stimuli that are responsible for chronic inflammatory glial activation, including cytokines (IL-1, TNF-α), lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and β-amyloid-42. The resulting neurotoxic glial products can enhance glial activation and thereby contribute to the progression of chronic neurodegenerative diseases.

One of such potentially neurotoxic compounds is the glial cell product — S100B. S100B synthesis in AD can increase severalfold, with protein levels reaching micromolar concentrations, in comparison with healthy age-matched controls. Moreover, S100B levels increase precisely in those brain regions that are associated with AD pathogenesis.

In the case of AD, S100B levels in the brain are higher due to activated astrocytes, cellular components of amyloid plaques, which contain an increased amount of S100B [

32]. S100B is known to stimulate axonal growth and neuroprotection, and its increased levels in the brains of AD patients may initially be a part of compensatory response. Overexpression of this protein, however, may also exert adverse effects.

The neurotrophic activity of S100B also contributes to aberrant axonal hypertrophy and the formation of large dystrophic neurites in and around amyloid plaques, and chronically elevated S100B levels in the brain result in enhanced expression of APP, which may cause further accumulation of amyloid peptide.

S100B can also stimulate glial activation, leading to neuroinflammation and neuronal dysfunction. The degree of astrocytosis is known to vary among AD patients. Diffuse amyloid plaques are associated with mild astrocytosis, while axonal plaques are associated with a large amount of activated astrocytes.

S100B concentrations may reflect the ratio of these two plaque types in AD, as the number of S100B-overexpressing astrocytes and elevated S100B levels in tissue correlate with the density of neuritic plaques and the density of APP-overexpressing dystrophic neurites inside individual plaques. Thus, S100B overexpression occurs in association with neurodegeneration and may induce a damaging effect [

33].

These findings suggest that S100B directly induces degenerative changes in axons and promotes the growth of degenerative axons overexpressing APP in diffuse amyloid deposits, as well as transforming benign diffuse deposits into diagnostic axonal plaques responsible for cortical atrophy in AD.

Increased S100B content in the brain of AD patients is also directly associated with tau-positive neuritic pathology. S100B overexpression, with its subsequent trophic and toxic effects on neurons, may be an important pathogenetic mechanism in the development of neuritic and neurofibrillary pathological changes in AD.

In patients with AD and vascular dementia, parallel overexpression of S100B and the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1 has been observed, which plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of neuropathological changes. An association has been noted between glial cells overexpressing IL-1 and S100B and increased neurofibrillary tangles of tau protein [

34].

6. Claudin

Tight junction proteins of the blood-brain barrier are vitally important for maintaining the integrity of endothelial cells lining blood vessels of the brain. These protein complexes are located in the space between endothelial cells where they create a dynamic, restrictive, and highly regulated microenvironment that is vital for neuronal homeostasis [

6].

By restricting paracellular diffusion of material between the blood and brain, tight junction proteins form a kind of protective barrier preventing the passage of unwanted and potentially harmful material [

6].

At the same time, this protective barrier hinders the therapeutic efficiency of drugs acting on the central nervous system, as more than 95% of small molecule therapeutics are unable to cross the blood-brain barrier [

15].

Claudin-5 is the most enriched tight junction protein in the blood-brain barrier and its dysfunction is associated with neurodegenerative disorders such as AB, multiple sclerosis and some psychiatric disorders.

Tight junctions are a vital component of the brain endothelium, regulating blood-brain exchange and protecting delicate neural tissue from blood-borne insults such as pathogens and immune cells [

16].

Various upstream signaling components can regulate claudin-5 levels, and targeting these pathways to modulate claudin-5 expression in response to certain pathologies is a promising therapeutic strategy.

Furthermore, RNAi-mediated suppression of claudin-5 is a well-studied strategy for transiently modulating BBB permeability, enabling small-molecule therapeutics in preclinical disease models which may be useful for the treatment of various CNS diseases [

20].

Other signaling molecules

Various studies have identified a number of classical and putative neuropeptides associated with the development and progression of neurodegenerative diseases. Arginine vasopressin, synthesized in the hypothalamus and regulating fluid balance and stress response, has shown dysregulation in the Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, a subtype of VD, which correlates with cognitive decline and hippocampal damage. Elevated arginine vasopressin levels in the right parahippocampal gyrus have also been observed in AD patients, but using it as a specific biomarker is restricted by its nonspecificity and the impact of comorbidities [

5]. Gastrin-releasing peptide, which functions through bombesin receptors, plays a dual role: on the one hand, it promotes arterial damage and intimal hyperplasia by enhancing vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, and on the other hand, it mitigates cognitive impairment in VD patients by modulating neuronal activity in the hippocampus and influencing neurogenesis. Glucagon-like peptides (GLP-1 and GLP-2), proglucagon derivatives, exhibit neuroprotective properties.

Adrenomedullin (AM), a multifunctional neuropeptide with vasodilatory, antiapoptotic, and anti-inflammatory effects, is strongly expressed in endothelial cells. Its expression increases after vascular insults, potentially promoting the restoration of vascular function through the activation of growth factors. AM deficiency is associated with VD exacerbation, and its conjugates are considered potential therapeutic agents.

Serum somatostatin and neuron-specific enolase (NSE) have also been proposed as biochemical markers of early VD: decreased somatostatin levels and increased NSE correlate with cognitive deficits. Among the putative neuropeptides, leptin and adiponectin, adipokines produced by adipose tissue, demonstrate a significant association with cognitive functions. Low leptin levels are associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment and dementia, while adiponectin impacts cerebral vascular function and improves cognitive function in patients with visceral hypertension [

35].

A stepwise diagnostic algorithm is used in the clinic: clinical neuropsychological assessment and MRI; if in doubt, biomarker screening is performed in patients with mild cognitive decline or dementia; and if the results are positive or inconsistent, a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis or PET scan is performed. This approach is consistent with the updated concept of biological diagnosis of AD, where the diagnosis is not only based on symptoms (memory, thinking, behavior), but also on objective biomarkers reflecting pathology in the brain—even when clinical manifestations are minimal or absent [

10].

Clinical screening includes the patient’s complaints, objective assessment of cognitive deficits (MMSE, MoCA, CDR-SB scales), assessment of daily functioning, and exclusion of reversible causes of dementia. Neuropsychological assessment remains the first line and determines the feasibility of further biomarker-based diagnosis specification and differential diagnosis [

1]. In the case of mild cognitive impairment, neuroimaging and/or fluid-based biomarkers may increase diagnostic confidence and stratify the risk of disease progression [

4]. AD diagnostic criteria have been revised to include biomarkers divided into two categories: markers of amyloid pathology (decreased Aβ42 levels in the cerebrospinal fluid, positive PET imaging with amyloid ligands) and markers of neuronal damage/tau pathology (increased tau and phospho-tau in the cerebrospinal fluid, decreased glucose metabolism on FDG-PET, medial temporal lobe atrophy on MRI). The combination of these biomarkers helps to diagnose AD in the preclinical and prodromal stages, long before the manifestation of overt dementia. Genetic risk factors for AD, such as mutations in the APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 genes (which enhance Aβ42 production) and the ApoEε4 allele (which impairs Aβ clearance), are directly linked to these processes. Biomarkers are recommended as a preliminary screening for amyloid status, followed by cerebrospinal fluid analysis or PET, if necessary [

25].

MRI is a mandatory step to exclude alternative pathologies and to assess neurodegeneration (medial temporal lobe/hippocampal atrophy, parieto-temporal changes). Metabolic patterns on PET imaging (bilateral parieto-temporal hypometabolism, posterior cingulate cortex) confirm the diagnosis of AD and help differentiate it. This method is recommended for the early diagnosis of MCI with suspected neurodegeneration [

1]. Amyloid and tau PET provide direct confirmation of amyloid and/or tau pathology and are used in clinically complex cases or to confirm the diagnosis when other methods give conflicting results.

Table 1 presents summarized data on the functional role of major biomarkers in neurodegenerative processes of the central nervous system.

Comprehensive molecular biomarkerpanels

The relevance of research into biomarkers for neurodegenerative diseases is driven by an urgent need for their early, preclinical diagnostics, enabling intervention before irreversible brain damage develops [

25]. Promising areas of research include methods for less invasive biomarker testing than cerebrospinal fluid analysis. The focus should be on integrating data on various classes of signaling molecules—neuropeptides, pathology proteins (Aβ, tau), markers of neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, synaptic dysfunction, and genetic risk factors—into comprehensive diagnostic panels [

4]. This will not only improve the accuracy of differential diagnosis between different types of dementia (e.g., VC and AD, which often coexist), but also ensure patient stratification for personalized therapy and the objective assessment of the effectiveness of new pharmacological agents in clinical trials.

Given that the development of standardized, highly sensitive, and specific biomarker detection methods remains an important task for their widespread implementation in clinical practice, we have developed comprehensive molecular biomarker panels for screening AD and differentiating it from other forms of dementia. An immunocytochemical (ICC) study was conducted to identify signaling molecules (molecular markers) involved in the neurodegeneration process in buccal epithelial cells and peripheral blood lymphocytes in patients with vascular dementia due to AD, as well as in age-matched volunteers without this pathology.

The study was carried out on a cohort of 203 participants, divided into three groups: a group of patients with clinically diagnosed AD (57 persons, 21% male and 79% female); a group of patients with clinically diagnosed VD (100 persons, 26% male and 74% female); and volunteers without clinical manifestations of neuropsychiatric disorders (46 persons, 32.6% male and 67.4% female). The average age of the examined patients in all the groups was 84.6±7.6 (with AD – 77±12.2 years, with vascular dementia – 79.7±9.8 years, and volunteers – 61.7±7.6).

This comprehensive study allowed to identify and confirm the expression of key signaling molecules in peripheral biological tissues (blood lymphocytes and buccal epithelial cells), which are directly associated with the development of dementia of different origins.

Table 2 presents data from the comparative analysis of l1 biomarkers in the buccal epithelium and peripheral blood lymphocytes in patients with AD, vascular dementia, and healthy controls. This study not only identified but also validated specific molecular biomarkers that can be used both for the initial detection of cognitive impairments and for differential diagnosis of various types of dementia, taking into account the mechanisms of their development.

The study results convincingly demonstrate that peripheral blood lymphocytes and buccal epithelial cells are highly informative biological material for life-time personalized molecular diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases. The buccal epithelium deserves special attention, as it offers significant advantages thanks to easy and safe noninvasive sampling and a broader spectrum of molecular markers detectable in it as compared to blood lymphocytes.

The main specific results of the study have showed the following:

The DRP1 protein expression levels in blood lymphocytes were statistically significantly increased, while the expression levels of β-amyloid, NF-κB and tau protein in the buccal epithelium were statistically significantly decreased both in AD patients and in patients with vascular dementia as compared to healthy controls.

Expression of α-synuclein, RAGE and PINK1 proteins in the buccal epithelium showed a statistically significant decrease in AD patients as compared with both VD patients and the control group.

The claudin expression levels in the buccal epithelium were statistically significantly decreased in patients with vascular dementia as compared to healthy controls.

Opposite changes in S100 protein expression were observed: its level in blood lymphocytes was significantly elevated, while in the buccal epithelium, it was significantly decreased in AD patients as compared to the control group.

The analysis revealed statistically significant differences in the expression of certain specific biomarkers, which allowed for the development and scientific validation of two diagnostic panels: one for the molecular verification of dementia as a pathological syndrome, and the other for the differential diagnosis of various types of dementia depending on their pathogenesis.

Based on the overall results of the study, two diagnostic molecular biomarker panels have been developed:

(a) “Panel for identifying risk groups in screening for cognitive impairment”, which includes analysis of expression of DRP1 and S100 proteins in blood lymphocytes, and β-amyloid, NF-κB, tau protein, claudin, and S100 protein in the buccal epithelium (

Table 3). This panel allows for confirmation of suspected dementia development, regardless of its origin.

(b) “Panel for life-time diagnostics of AD”, which is oriented at differential diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia by analyzing the expression of α-synuclein, RAGE, PINK1 and phosphorylated tau protein in the buccal epithelium (

Table 4).

To improve the intra-vitam diagnosis and monitoring of AD, it appears promising to further elaborate a personalized predictive algorithm that will account for the personal significance of each molecular biomarker based on additional mathematical analysis. This approach will not only improve diagnosis, but also enable us to predict the dynamics of disease development in specific patients.