Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

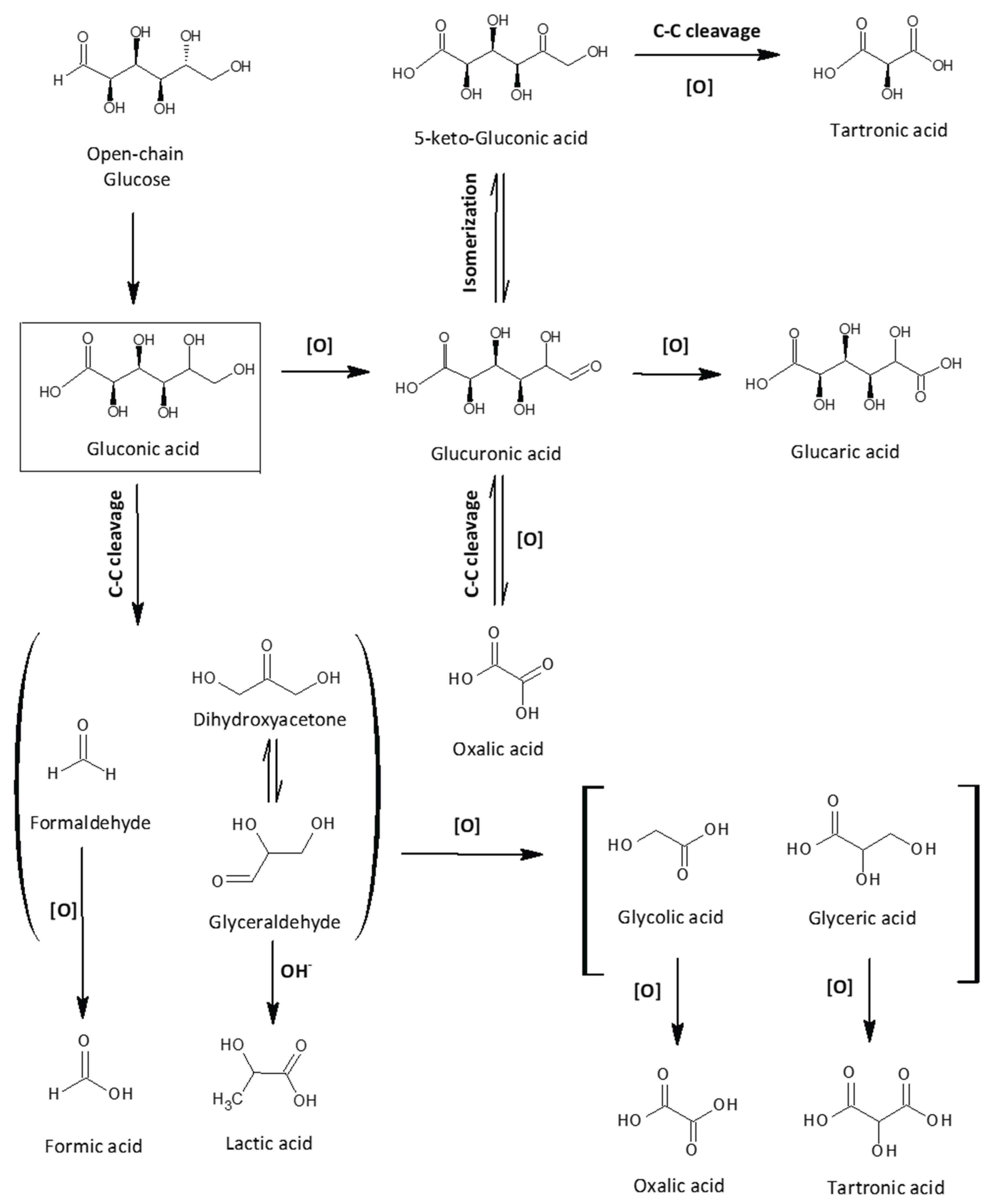

2. Results and Discussion

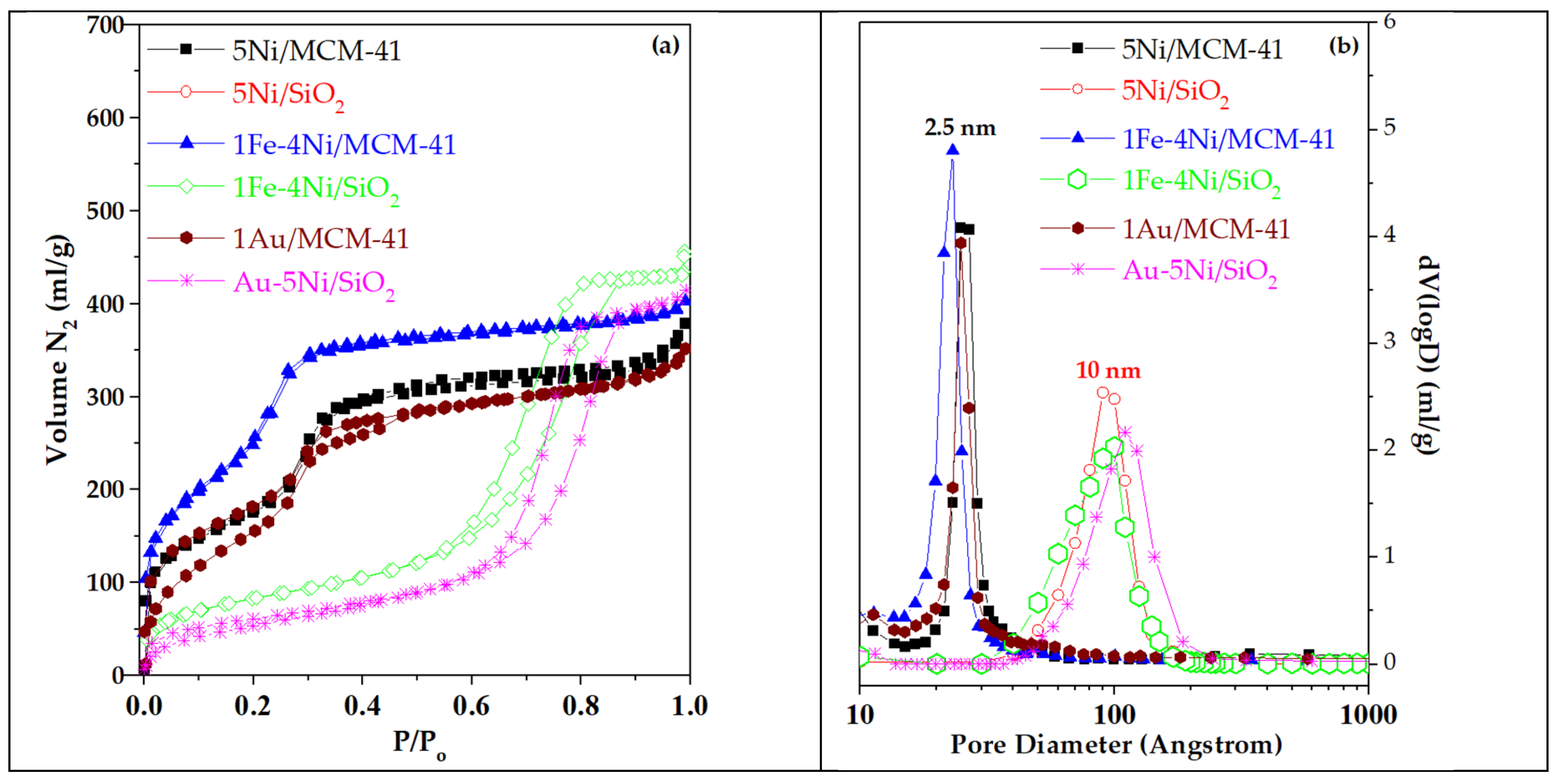

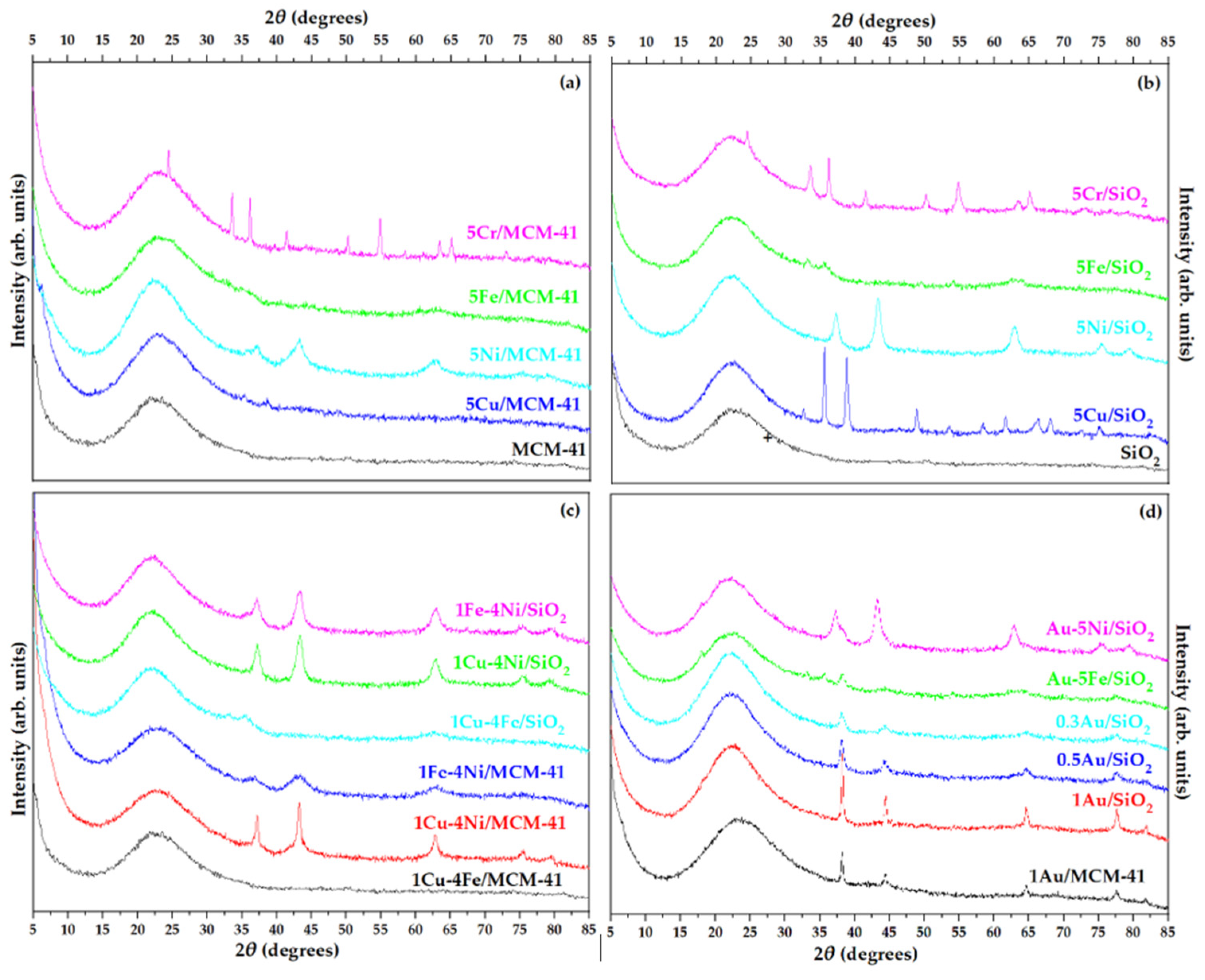

2.1. Textural and Structural Characterization

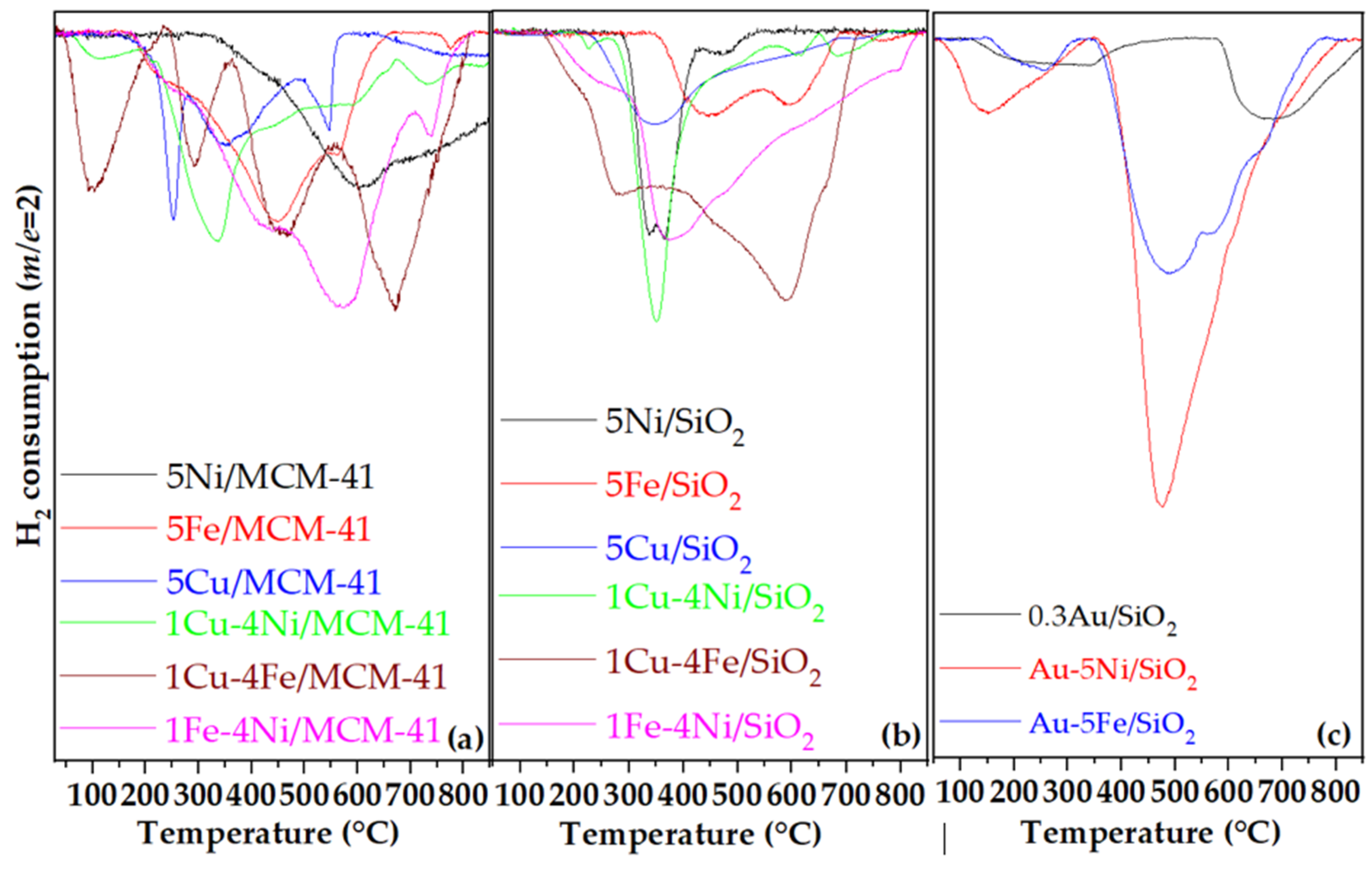

2.2. Reducibility of Supported Catalysts

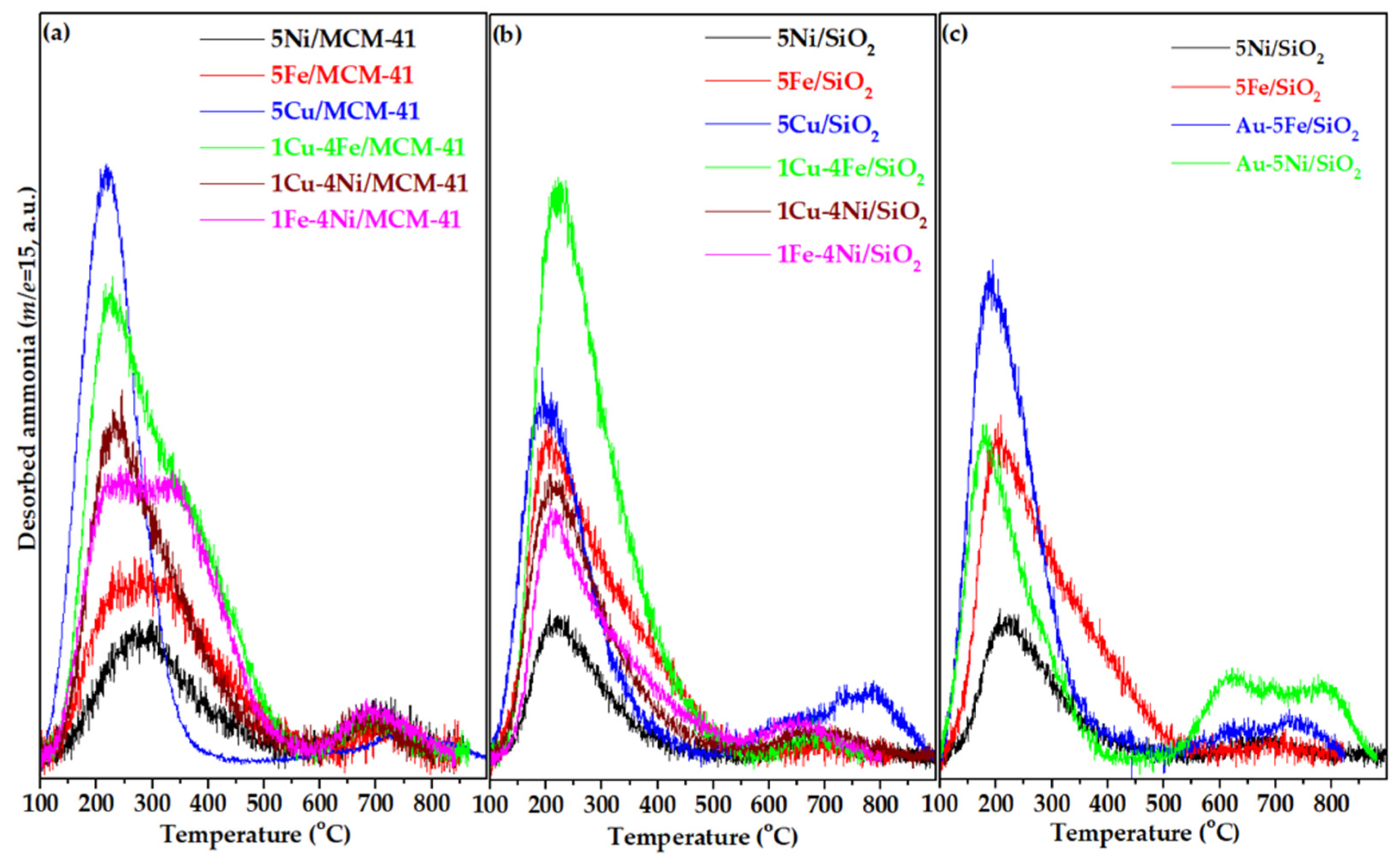

2.3. Acidity of Supported Catalysts

2.4. Evaluation of Catalytic Performance Under Standard Reaction Conditions

2.4.1. Monometallic Catalysts Supported on SiO₂ and MCM-41

2.4.2. Bimetallic Transition Metal Oxide Catalysts Supported on SiO₂ and MCM-41

2.5. Catalyst Stability

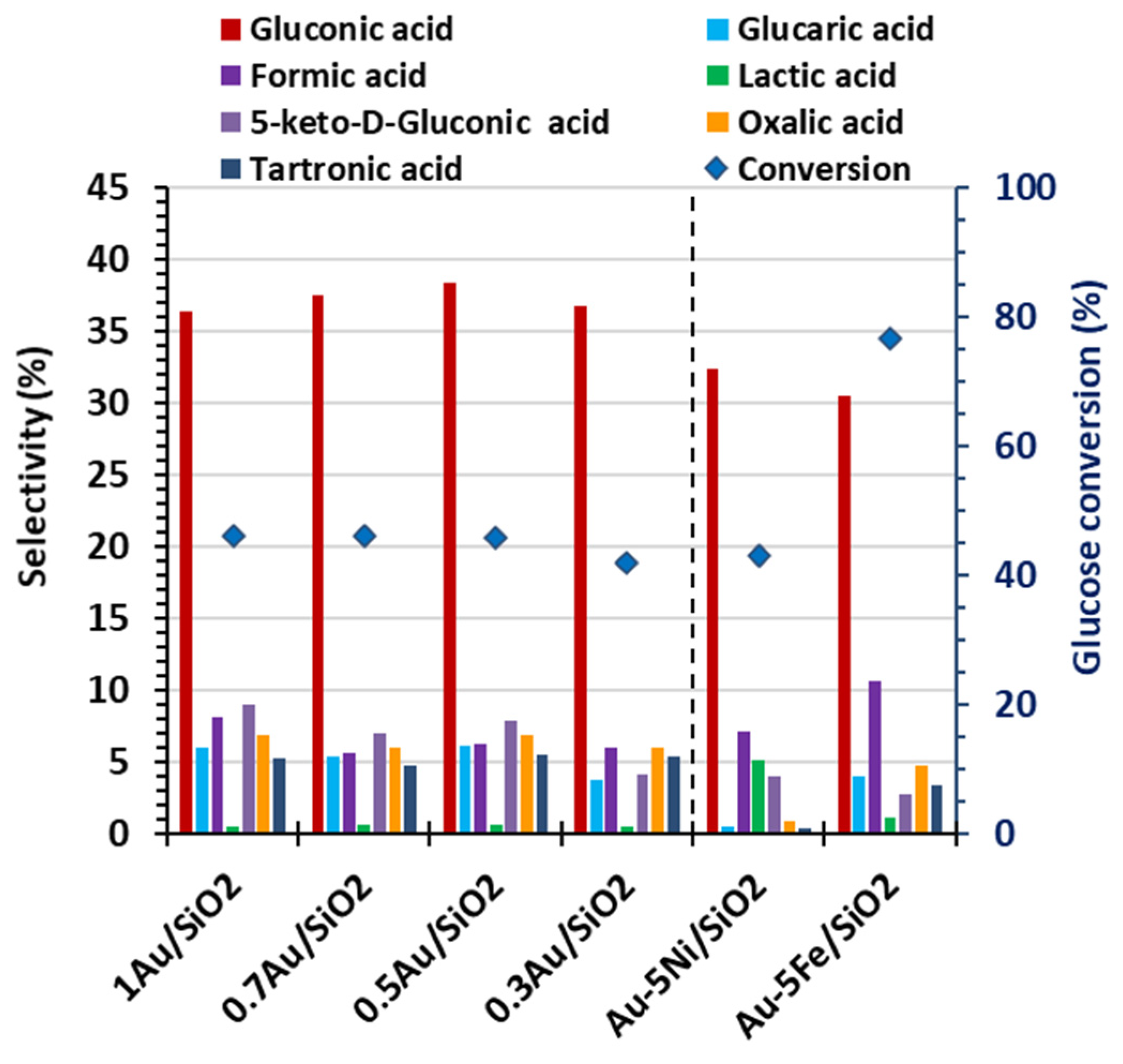

2.5. Evaluation of Au-Supported Catalysts with or Without Transition Metals on SiO₂

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Reagents

4.2. Preparation of Mesoporous MCM-41

4.3. Preparation of Supported Metal Catalysts

4.4. Catalysts Characterization

4.5. Catalyst Performance Evaluation and Product Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mehtiö, T.; Toivari, M.; Wiebe, M.G.; Harlin, A.; Penttilä, M.; Koivula, A. Production and Applications of Carbohydrate-Derived Sugar Acids as Generic Biobased Chemicals. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2016, 36, 904–916. [CrossRef]

- Werpy, T.; Petersen, G.; Aden, A.; Bozell, J.; Holladay, J.; White, J.; Manheim, A.; Eliot, D.; Lasure, L.; Jones, S. Top Value Added Chemicals from Biomass Volume I - Results of Screening for Potential Candidates from Sugars and Synthesis Gas. Us Nrel 2004, 76 pages. [CrossRef]

- Shcherbakova-Sandu, M.P.; Meshcheryakov, E.P.; Gulevich, S.A.; Kushwaha, A.K.; Kumar, R.; Sonwane, A.K.; Samal, S.; Kurzina, I.A. Use of Glucose Obtained from Biomass Waste for the Synthesis of Gluconic and Glucaric Acids: Their Production, Application, and Future Prospects. Molecules 2025, 30. [CrossRef]

- Kornecki, J.F.; Carballares, D.; Tardioli, P.W.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Alcántara, A.R.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Enzyme Production of D-Gluconic Acid and Glucose Oxidase: Successful Tales of Cascade Reactions. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 5740–5771. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huber, G.W. Catalytic Oxidation of Carbohydrates into Organic Acids and Furan Chemicals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 1351–1390. [CrossRef]

- Arias, P.L.; Cecilia, J.A.; Gandarias, I.; Iglesias, J.; López Granados, M.; Mariscal, R.; Morales, G.; Moreno-Tost, R.; Maireles-Torres, P. Oxidation of Lignocellulosic Platform Molecules to Value-Added Chemicals Using Heterogeneous Catalytic Technologies. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 2721–2757. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Fang, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, G. Efficient Base-Free Direct Oxidation of Glucose to Gluconic Acid over TiO 2 -Supported Gold Clusters. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 1326–1334. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Liu, X.; Iqbal, S.; Miedziak, P.J.; Edwards, J.K.; Armstrong, R.D.; Morgan, D.J.; Wang, J.; Hutchings, G.J. Base-Free Oxidation of Glucose to Gluconic Acid Using Supported Gold Catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 107–117. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Van De Vyver, S.; Sharma, K.K.; Román-Leshkov, Y. Insights into the Stability of Gold Nanoparticles Supported on Metal Oxides for the Base-Free Oxidation of Glucose to Gluconic Acid. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 719–726. [CrossRef]

- Delidovich, I. V.; Moroz, B.L.; Taran, O.P.; Gromov, N. V.; Pyrjaev, P.A.; Prosvirin, I.P.; Bukhtiyarov, V.I.; Parmon, V.N. Aerobic Selective Oxidation of Glucose to Gluconate Catalyzed by Au/Al2O3 and Au/C: Impact of the Mass-Transfer Processes on the Overall Kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 223, 921–931. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Saha, B.; Vlachos, D.G. Pt Catalysts for Efficient Aerobic Oxidation of Glucose to Glucaric Acid in Water. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 3815–3822. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wan, Z.; Yu, I.K.M.; Tsang, D.C.W. Sustainable Production of High-Value Gluconic Acid and Glucaric Acid through Oxidation of Biomass-Derived Glucose: A Critical Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 312, 127745. [CrossRef]

- Amaniampong, P.N.; Trinh, Q.T.; Wang, B.; Borgna, A.; Yang, Y.; Mushrif, S.H. Biomass Oxidation: Formyl C-H Bond Activation by the Surface Lattice Oxygen of Regenerative CuO Nanoleaves. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 8928–8933. [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhao, M.; Shen, J.; Yan, W.; He, L.; Thapa, P.S.; Ren, S.; Subramaniam, B.; Chaudhari, R. V. Exceptional Performance of Bimetallic Pt1Cu3/TiO2 Nanocatalysts for Oxidation of Gluconic Acid and Glucose with O2 to Glucaric Acid. J. Catal. 2015, 330, 323–329. [CrossRef]

- Amaniampong, P.N.; Jia, X.; Wang, B.; Mushrif, S.H.; Borgna, A.; Yang, Y. Catalytic Oxidation of Cellobiose over TiO2 Supported Gold-Based Bimetallic Nanoparticles. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 2393–2405. [CrossRef]

- Karakoulia, S.A.; Triantafyllidis, K.S.; Tsilomelekis, G.; Boghosian, S.; Lemonidou, A.A. Propane Oxidative Dehydrogenation over Vanadia Catalysts Supported on Mesoporous Silicas with Varying Pore Structure and Size. Catal. Today 2009, 141, 245–253. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.G.; Yu, X.Q.; Huang, J.S.; Li, S.G.; Li, L.S.; Che, C.M. Asymmetric Epoxidation of Alkenes Catalysed by Chromium Binaphthyl Schiff Base Complex Supported on MCM-41. Chem. Commun. 1999, 41, 1789–1790. [CrossRef]

- Wisniewska, J.; Sobczak, I.; Ziolek, M. Gold Based on SBA-15 Supports – Promising Catalysts in Base-Free Glucose Oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 413. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, V.P.; Vishwanathan, V.; Chary, K.V.R. Influence of Preparation Methods of Nano Au/MCM-41 Catalysts for Vapor Phase Oxidation of Benzyl Alcohol. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 9944–9953. [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.C.; Alderete, J.B.; Pecchi, G.; Campos, C.H.; Reyes, P.; Pawelec, B.; Vaschetto, E.G.; Eimer, G.A. Heterogeneous Hydrogenation of Nitroaromatic Compounds on Gold Catalysts: Influence of Titanium Substitution in MCM-41 Mesoporous Supports. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2016, 517, 110–119. [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.S.; Vartuli, J.C.; Roth, W.J.; Leonowicz, M.E.; Kresge, C.T.; Schmitt, K.D.; Chu, C.T.W.; Olson, D.H.; Sheppard, E.W.; McCullen, S.B.; et al. A New Family of Mesoporous Molecular Sieves Prepared with Liquid Crystal Templates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 10834–10843. [CrossRef]

- Szegedi, Á.; Popova, M.; Mavrodinova, V.; Urbán, M.; Kiricsi, I.; Minchev, C. Synthesis and Characterization of Ni-MCM-41 Materials with Spherical Morphology and Their Catalytic Activity in Toluene Hydrogenation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2007, 99, 149–158. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Velandia, J.E.; Villa, A.L. Isomerization of A- and Β- Pinene Epoxides over Fe or Cu Supported MCM-41 and SBA-15 Materials. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2019, 580, 17–27. [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.S.; Kim, B.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.H.; Park, S.J. Reduction Behaviors of Nitric Oxides on Copper-Decorated Mesoporous Molecular Sieves. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2010, 31, 100–103. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.T.; Weng, W.T. Ethylene Polymerization over Cr/MCM-41 and Cr/MCM-48 Catalysts Prepared by Chemical Vapor Deposition. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2009, 40, 48–54. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Park, C.; Dai, S. Influences of Synthesis Conditions and Mesoporous Structures on the Gold Nanoparticles Supported on Mesoporous Silica Hosts. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2009, 122, 160–167. [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.A.; Ullah, S.; Nasim, F.; Choucair, M.; Nadeem, M.A.; Iqbal, A.; Badshah, A.; Nadeem, M.A. Cr2O3-Carbon Composite as a New Support Material for Efficient Methanol Electrooxidation. Mater. Res. Bull. 2016, 77, 221–227. [CrossRef]

- Elías, V.; Sabre, E.; Sapag, K.; Casuscelli, S.; Eimer, G. Influence of the Cr Loading in Cr/MCM-41 and TiO 2/Cr/MCM-41 Molecular Sieves for the Photodegradation of Acid Orange 7. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2012, 413–414, 280–291. [CrossRef]

- Vora, B. V. Development of Catalytic Processes for the Production of Olefins. Trans. Indian Natl. Acad. Eng. 2023, 8, 201–219. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-H.; Wang, Y.-L.; An-Nan Ko Liquid Phase Hydrogenation of t, t, c-1, 5, 9-Cyclododecatriene over Ni/MCM-41 and Ni/SiO2 Catalysts. J. Chinese Chem. Soc. 2009, 56, 908–915.

- Bouazizi, N.; Bargougui, R.; Oueslati, A.; Benslama, R. Effect of Synthesis Time on Structural, Optical and Electrical Properties of CuO Nanoparticles Synthesized by Reflux Condensation Method. Adv. Mater. Lett. 2015, 6, 158–164. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Long, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, W.; Liu, P.; Li, Z.; Wu, L.; Fu, X. Catalytic Role of Cu Sites of Cu/MCM-41 in Phenol Hydroxylation. Langmuir 2010, 26, 1362–1371. [CrossRef]

- Supattarasakda, K.; Petcharoen, K.; Permpool, T.; Sirivat, A.; Lerdwijitjarud, W. Control of Hematite Nanoparticle Size and Shape by the Chemical Precipitation Method. Powder Technol. 2013, 249, 353–359. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Lee, B.; Dai, S.; Overbury, S.H. Coassembly Synthesis of Ordered Mesoporous Silica Materials Containing Au Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2003, 19, 3974–3980. [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Ma, Z.; Zhu, H.; Chi, M.; Dai, S. Evidence for and Mitigation of the Encapsulation of Gold Nanoparticles within Silica Supports upon High-Temperature Treatment of Au/SiO2 Catalysts: Implication to Catalyst Deactivation. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2010, 386, 147–156. [CrossRef]

- Dow, W.P.; Wang, Y.P.; Huang, T.J. TPR and XRD Studies of Yttria-Doped Ceria/γ-Alumina-Supported Copper Oxide Catalyst. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2000, 190, 25–34. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Corma, A. Metal Catalysts for Heterogeneous Catalysis: From Single Atoms to Nanoclusters and Nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 4981–5079. [CrossRef]

- Mokhonoana, M.P.; Coville, N.J. Highly Loaded Fe-MCM-41 Materials: Synthesis and Reducibility Studies. Materials (Basel). 2009, 2, 2337–2359. [CrossRef]

- Ashik, U.P.M.; Wan Daud, W.M.A. Nanonickel Catalyst Reinforced with Silicate for Methane Decomposition to Produce Hydrogen and Nanocarbon: Synthesis by Co-Precipitation Cum Modified Stöber Method. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 46735–46748. [CrossRef]

- Son, I.H.; Lee, S.J.; Soon, A.; Roh, H.S.; Lee, H. Steam Treatment on Ni/γ-Al2O3 for Enhanced Carbon Resistance in Combined Steam and Carbon Dioxide Reforming of Methane. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2013, 134–135, 103–109. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, P.; Soria, M.A.; Carabineiro, S.A.C.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J.; Mendes, A.; Madeira, L.M. Application of Au/TiO2 Catalysts in the Low-Temperature Water-Gas Shift Reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 4670–4681. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.R.; Ren, L.H.; Lu, A.H.; Li, W.C. Influence of Pretreatment Atmospheres on the Activity of Au/CeO2 Catalyst for Low-Temperature CO Oxidation. Catal. Commun. 2011, 13, 18–21. [CrossRef]

- Alencar, C.S.L.; Paiva, A.R.N.; Da Silva, J.C.M.; Vaz, J.M.; Spinace, E.V. One-Step Synthesis of AuCu/TiO2catalysts for CO Preferential Oxidation. Mater. Res. 2020, 23, 2–7. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Louis, C.; Delannoy, L.; Keane, M.A. Silica- and Titania-Supported Ni-Au: Application in Catalytic Hydrodechlorination. J. Catal. 2007, 247, 256–268. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.W.; Hu, C.W.; Yang, Y.; Tong, D.M.; Zhu, L.F.; Zhang, R.N.; Zhao, B.H. Study on the Effect of Metal Types in (Me)-Al-MCM-41 on the Mesoporous Structure and Catalytic Behavior during the Vapor-Catalyzed Co-Pyrolysis of Pubescens and LDPE. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2013, 129, 202–213. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Liu, S.; Cardoso, A.; Han, Y.; Bikane, K.; Sun, L. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Rubbers and Vulcanized Rubbers Using Modified Zeolites and Mesoporous Catalysts with Zn and Cu. Energy 2019, 188, 116117. [CrossRef]

- Rosenholm, J.B.; Rahiala, H.; Puputti, J.; Stathopoulos, V.; Pomonis, P.; Beurroies, I.; Backfolk, K. Characterization of Al- and Ti-Modified MCM-41 Using Adsorption Techniques. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2004, 250, 289–306. [CrossRef]

- Abbadi, A.; Van Bekkum, H. JOURNAL OF MOLECULAR CATALYSIS Effect of PH in the Pt-Catalyzed Oxidation of D-Glucose to D-Gluconic Acid. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 1995, 97, 11–18.

- Moreno, T.; Kouzaki, G.; Sasaki, M.; Goto, M.; Cocero, M.J. Uncatalysed Wet Oxidation of D-Glucose with Hydrogen Peroxide and Its Combination with Hydrothermal Electrolysis. Carbohydr. Res. 2012, 349, 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, N.; Aadil Yatoo, M.; Saravanamurugan, S. Glucose Oxidation to Carboxylic Products with Chemocatalysts; Elsevier B.V., 2019; ISBN 9780444643070.

- Jin, X.; Zhao, M.; Vora, M.; Shen, J.; Zeng, C.; Yan, W.; Thapa, P.S.; Subramaniam, B.; Chaudhari, R. V. Synergistic Effects of Bimetallic PtPd/TiO2 Nanocatalysts in Oxidation of Glucose to Glucaric Acid: Structure Dependent Activity and Selectivity. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 2932–2945. [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.E.; Walvoord, R.R.; Padilla-salinas, R.; Kozlowski, M.C. Aerobic Copper-Catalyzed Organic Reactions. 2013.

- Dry, M.E.; Stone, F.S. Oxidation Reactions Catalyzed by Doped Nickel Oxide. Discuss. Faraday Soc. 1959, 28, 192–200. [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Kinoshita, N.; Okatsu, H.; Akita, T.; Takei, T.; Haruta, M. Influence of the Support and the Size of Gold Clusters on Catalytic Activity for Glucose Oxidation. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 9265–9268. [CrossRef]

- Walkowiak, A.; Wolska, J.; Wojtaszek-Gurdak, A.; Sobczak, I.; Ziolek, M.; Wolski, L. Modification of Gold Zeolitic Supports for Catalytic Oxidation of Glucose to Gluconic Acid. Materials (Basel). 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Catalano, F.; Pompa, P.P.; Barrabino, A.; He, Y.; Li, J.J.; Long, M.; Liang, S.; Xu, H.; Isa, E.D.M.; Ahmad, H.; et al. Novel Pathways for the Preparation of Mesoporous MCM-41 Materials: Control of Porosity and Morphology. Alg. Dagbl. 2017, 457, 47237–47246.

- Ribeiro Carrott, M.M.L.; Conceição, F.L.; Lopes, J.M.; Carrott, P.J.M.; Bernardes, C.; Rocha, J.; Ramôa Ribeiro, F. Comparative Study of Al-MCM Materials Prepared at Room Temperature with Different Aluminium Sources and by Some Hydrothermal Methods. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2006, 92, 270–285. [CrossRef]

- Onda, A.; Ochi, T.; Kajiyoshi, K.; Yanagisawa, K. A New Chemical Process for Catalytic Conversion of D-Glucose into Lactic Acid and Gluconic Acid. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2008, 343, 49–54. [CrossRef]

- Witońska, I.; Frajtak, M.; Karski, S. Selective Oxidation of Glucose to Gluconic Acid over Pd-Te Supported Catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2011, 401, 73–82. [CrossRef]

- Solmi, S.; Morreale, C.; Ospitali, F.; Agnoli, S.; Cavani, F. Oxidation of D-Glucose to Glucaric Acid Using Au/C Catalysts. ChemCatChem 2017, 9, 2797–2806. [CrossRef]

| Catalysts | ICP-AES | XRD | BET | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal composition (wt.%) (a) | Crystal size (nm) (Reflection angle, degrees) (b) | Total surface area (m2/g) (c) | Total Pore volume (ml/g) (d) | Meso-macro-pore volume (ml/g) | Textural Volume (ml/g) (e) | |

| SiO2 | - | - | 329 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.01 |

| 0.3Au/SiO2 | 0.31 | 6.4 (44.4°) | 299 (328) | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.02 |

| 0.5Au/SiO2 | 0.53 | 9.6 (44.3°) | 318 (327) | 0.77 | 0.74 | 0.03 |

| 0.7Au/SiO2 | 0.64 | 10.5 (44.3°) | 304 (327) | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.03 |

| 1Au/SiO2 | 1.24 | 15.3 (44.2°) | 311 (325) | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.02 |

| 5Cr/SiO2 | 4.78 | 25.9 (36.2°) | 290 (306) | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.01 |

| 5Cu/SiO2 | 4.90 | 37.4 (35.6°) | 298 (309) | 0.92 | 0.68 | 0.24 |

| 5Fe/SiO2 | 4.78 | 8.6 (33.0°) | 308 (308) | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.01 |

| 5Ni/SiO2 | 5.00 | 12.5 (43.3°) | 287 (308) | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.10 |

| Au-5Fe/SiO2 | 0.38 - 5.02 | 15.9 (44.3°)(f) | 263 (304) | 0.66 | 0.60 | 0.06 |

| Au-5Ni/SiO2 | 0.32 - 5.68 | n.d. | 279 (304) | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.02 |

| 1Cu-4Fe/SiO2 | 1.09 - 4.84 | traces | 304 (302) | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.06 |

| 1Cu-4Ni/SiO2 | 1.25 - 4.48 | 10.1 (43.3°)(g) | 298 (305) | 2.17 | 0.67 | 1.50 |

| 1Fe-4Ni/SiO2 | 1.14 - 4.96 | 10.2 (43.3°)(g) | 303 (303) | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.05 |

| MCM-41 | - | - | 964 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.08 |

| 0.3Au/MCM-41 | 0.06 | n.d. | 705 (963) | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.05 |

| 1Au/MCM-41 | 0.62 | 13.3 (44.2°) | 651 (958) | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.03 |

| 5Cr/MCM-41 | 4.68 | 21.2 (36.2°) | 738 (898) | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.10 |

| 5Cu/MCM-41 | 3.60 | traces | 652 (921) | 0.56 | 0.49 | 0.08 |

| 5Fe/MCM-41 | 4.83 | traces | 743 (897) | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.09 |

| 5Ni/MCM-41 | 5.30 | 6.5 (43.2°) | 639 (899) | 0.59 | 0.51 | 0.08 |

| 1Cu-4Fe/MCM-41 | 0.93 - 4.15 | traces | 821 (896) | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.03 |

| 1Cu-4Ni/MCM-41 | 1.07 - 4.03 | 8.3 (43.5°)(g) | 866 (902) | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.03 |

| 1Fe-4Ni/MCM-41 | 1.02 - 3.97 | 9.7 (43.2°)(g) | 867 (901) | 0.62 | 0.59 | 0.03 |

| Catalysts | Acid sites | H2(d) cons. | Reduci-bility(e) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Weak(a) | Medium(b) | Strong(c) | |||

| (μmol/g) | (%) | |||||

| 0.3Au/SiO2 | - | - | - | - | 277 | - |

| 5Cu/SiO2 | 53.8 | 33.1 (196) | 8.9 (376) | 11.8(f) | 527 | 68.4 |

| 5Ni/SiO2 | 19.0 | 10.1 (223) | 5.5 (334) | 3.4 (682) | 459 | 55.6 |

| 5Fe/SiO2 | 46.0 | 24.8 (200) | 18.2 (357) | 3.0 (698) | 1050 | 81.8 |

| Au-5Fe/SiO2 | 56.8 | 44.1 (184) | 8.4 (347) | 4.3(g) | 2700 | 200.3 |

| Au-5Ni/SiO2 | 49.4 | 34.2 (180) | 0 | 15.2(h) | 4281 | 442.3 |

| 1Cu-4Fe/SiO2 | 69.9 | 40.5 (215) | 25.1 (339) | 4.3 (677) | 2366 | 160.7 |

| 1Cu-4Ni/SiO2 | 37.3 | 21.4 (212) | 10.7 (354) | 5.2 (691) | 1169 | 121.9 |

| 1Fe-4Ni/SiO2 | 35.6 | 18.7 (209) | 11.6 (393) | 5.3 (653) | 1771 | 153.9 |

| 5Cu/MCM-41 | 61.8 | 58.0 (217) | 0 | 3.8 (756) | 644 | 85.5 |

| 5Fe/MCM-41 | 36.8 | 15.7 (248) | 15.3 (356) | 5.8 (723) | 1239 | 95.5 |

| 5Ni/MCM-41 | 22.6 | 8.3 (268) | 10.0 (382) | 4.3 (708) | 1781 | 197.2 |

| 1Cu-4Fe/MCM-41 | 64.9 | 35.4 (237) | 25.0 (347) | 4.5 (7.2) | 2382 | 188.8 |

| 1Cu-4Ni/MCM-41 | 45.8 | 27.8 (239) | 14.4 (338) | 3.6 (680) | 2033 | 237.3 |

| 1Fe-4Ni/MCM-41 | 51.8 | 24.3 (221) | 20.2 (339) | 7.3 (698) | 2436 | 255.9 |

| Catalyst | Glucose conversion (%) | Selectivity (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gluconic acid | Glucaric acid | Formic acid | Lactic acid | Oxalic acid | 5-keto-D-Gluconic acid | Tartronic acid | ||

| 1Au/SiO2 | 46.1 | 36.4 | 6.0 | 8.1 | 0.5 | 6.8 | 9.0 | 5.3 |

| 5Cr/SiO2 | 65.5 | 25.9 | 1.5 | 14.0 | 9.0 | 0.8 | - | - |

| 5Cu/SiO2 | 100.0 | - | - | 13.3 | 2.7 | 1.3 | - | - |

| 5Fe/SiO2 | 79.5 | 22.5 | 1.7 | 15.1 | 10.3 | 1.5 | - | - |

| 5Ni/SiO2 | 41.1 | 32.2 | 0.5 | 7.7 | 7.1 | - | - | - |

| 1Cu-4Fe/SiO2 | 99.9 | - | - | 7.5 | 2.5 | 9.3 | - | - |

| 1Cu-4Ni/SiO2 | 99.7 | - | - | 16.2 | 3.9 | 1.4 | - | - |

| 1Fe-4Ni/SiO2 | 98.9 | 6.5 | 1.8 | 19.5 | 5.5 | 2.4 | - | - |

| 1Au/MCM41 | 40.3 | 41.0 | 5.4 | 8.2 | 1.2 | 5.9 | 7.1 | 4.9 |

| 5Cr/MCM-41 | 57.5 | 28.8 | 1.8 | 15.3 | 7.8 | 0.9 | - | - |

| 5Cu/MCM-41 | 100.0 | - | - | 19.5 | 5.2 | 0.5 | - | - |

| 5Fe/MCM-41 | 75.5 | 22.2 | 1.4 | 14.1 | 9.2 | 1.6 | - | - |

| 5Ni/MCM-41 | 44.1 | 32.6 | 1.1 | 10.8 | 7.9 | 0.8 | - | - |

| 1Cu-4Fe/MCM-41 | 99.8 | - | - | 13.1 | 3.7 | 6.8 | - | - |

| 1Cu-4Ni/MCM-41 | 99.8 | - | - | 9.2 | 1.1 | 1.7 | - | - |

| 1Fe-4Ni/MCM-41 | 92.7 | 12.0 | 2.9 | 20.3 | 4.2 | 3.4 | - | - |

| Catalyst | Leaching (%) * (ICP-AES (ppm)) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au | Cu | Cr | Fe | Ni | |

| 1Au/SiO2 | 0 (n.d.) | - | - | - | - |

| 5Cr/SiO2 | - | - | 20.3 (14.7) | - | - |

| 5Cu/SiO2 | - | 24.4 (20.0) | - | - | - |

| 5Fe/SiO2 | - | - | - | 9.1 (6.5) | - |

| 5Ni/SiO2 | - | - | - | - | 3.3 (2.7) |

| 1Cu-4Fe/SiO2 | - | 41.3 (6.9) | - | 16.1(11.9) | - |

| 1Cu-4Ni/SiO2 | - | 63.6 (53.5) | - | 41.7 (126.0) | |

| 1Fe-4Ni/SiO2 | - | - | - | 27.2 (4.0) | 5.3 (3.4) |

| 1Au/MCM41 | 0 (n.d.) | - | - | - | - |

| 5Cr/MCM-41 | - | - | 50.6 (37.0) | - | - |

| 5Cu/MCM-41 | - | 26.0 (22.5) | - | - | - |

| 5Fe/MCM-41 | - | - | - | 20.0 (16.1) | - |

| 5Ni/MCM-41 | - | - | - | 7.0 (5.8) | |

| 1Cu-4Fe/MCM-41 | - | 43.7 (7.3) | - | 16.5 (12.2) | - |

| 1Cu-4Ni/MCM-41 | - | 53.8 (55.0) | - | - | 44.8 (173.0) |

| 1Fe-4Ni/MCM-41 | - | - | - | 39.3 (6.7) | 6.1 (4.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).