1. Introduction

Scientific and philosophical accounts of consciousness increasingly converge on the insight that perception is not a passive registration of an independently structured world but an active, selective, and inferential process. Classical ontology presupposes a fully instantiated external reality whose structures and properties exist prior to and independently of observation. Yet developments in quantum theory (Bohr, 1935; Wheeler, 1983; Wheeler & Zurek, 1983), phenomenology (Merleau-Ponty, 1945), and predictive processing (Friston, 2010; Clark, 2013; Hohwy, 2013) challenge this assumption by demonstrating that the contents of experience arise from dynamic interactions between organism and environment, mediated by internal models and context-dependent constraints. This tension invites renewed ontological inquiry: if perception is a constructive process, what is the status of the “reality” that perception constructs?

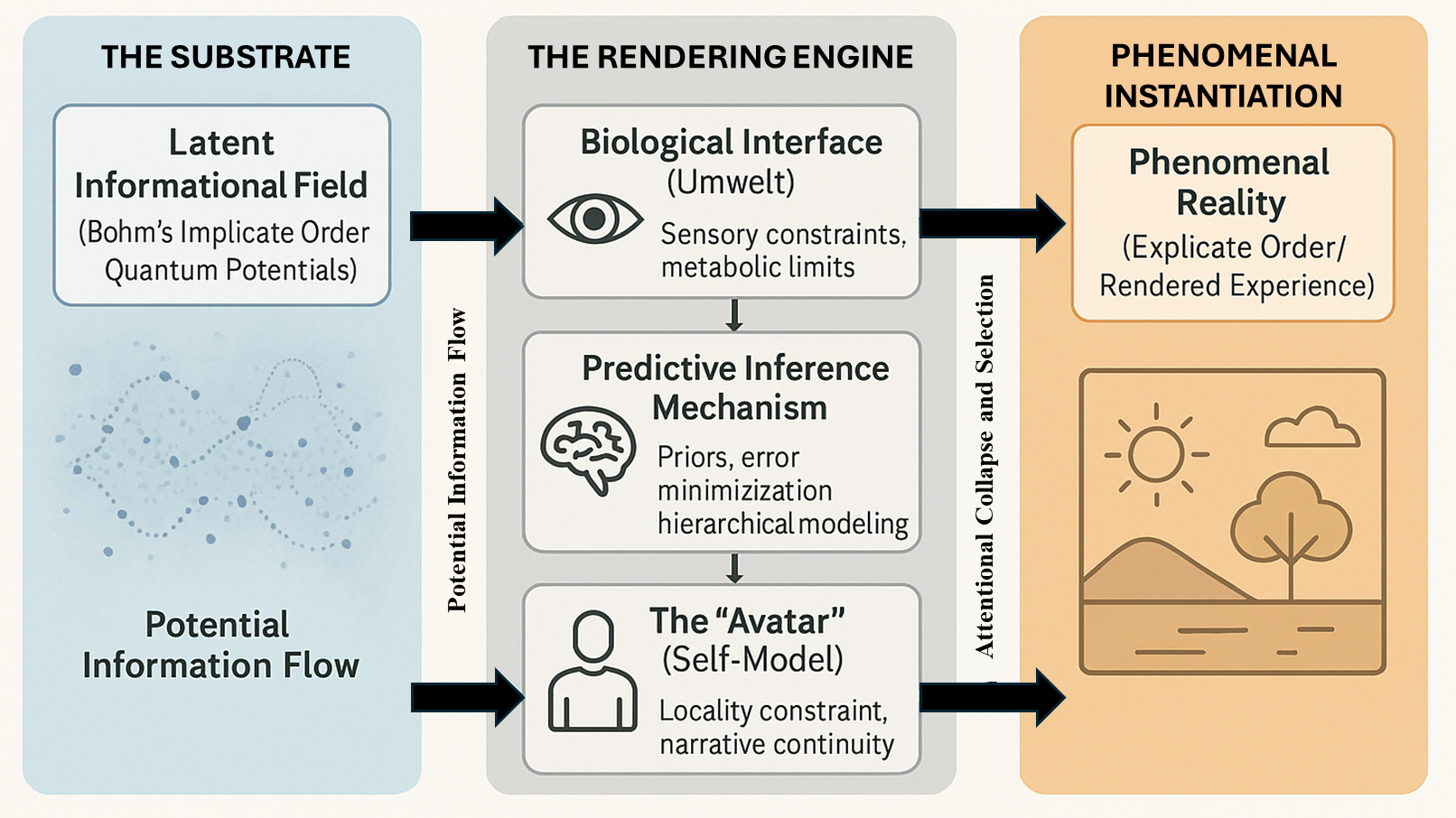

This article advances a post-Bohmian rendering ontology, a conceptual framework in which consciousness is understood as an active process that selects, resolves, and renders latent informational potentials into determinate phenomenological forms. The proposal builds on David Bohm’s implicate order (Bohm, 1980), which posits a deeper, non-local informational structure underpinning observable phenomena, but departs from Bohm by rejecting the assumption of a continuously enfolded and fully specified substrate. Instead, the rendering model holds that reality is not globally instantiated; rather, it becomes locally determinate through acts of attention, measurement, and inference.

Three considerations motivate this framework. First, quantum indeterminacy and the measurement problem suggest that physical systems do not possess definite properties until observation-specific interactions collapse superpositional states (von Neumann, 1932; Wheeler & Zurek, 1983; Leggett, 2002). Second, neuroscientific models of perception describe the brain as a prediction-driven inference engine that generates perceptual experience through continuous model updating rather than direct sensory copying (Rao & Ballard, 1999; Friston, 2010; Clark, 2013; Hohwy, 2013). Third, biological diversity in sensory Umwelten (von Uexküll, 1934; Barwich, 2020) reveals that organisms access only species-specific slices of environmental information, implying that the “world” of any observer is an interface constrained by evolutionary and computational limits.

The objective of this article is to unify these strands into a coherent ontological framework. I propose that consciousness operates as a rendering mechanism within a distributed informational field: it brings into phenomenological existence only the limited subset of environmental potentials relevant to the organism’s sensory, cognitive, and inferential capacities. Crucially, this mechanism is operationalized at the neural level by processes of global integration and constraint, providing a framework to quantify the quality of instantiation through metrics like Integrated Information (Φ) and linking the "collapse" function to observable phenomena like Global Neuronal Workspace ignition. This model clarifies the relationship between first-person phenomenology and third-person physical accounts, offering an alternative to substance-based metaphysics while retaining compatibility with empirical findings across quantum physics, neuroscience, and cognitive science.

The remainder of the article develops this framework systematically.

Section 2 examines the theoretical tensions motivating a revised ontology (classical vs. quantum and predictive processing).

Section 3 introduces the core rendering model and situates it relative to Bohm’s implicate order.

Section 4 analyzes the role of consciousness, attention, and collapse in resolving informational potentials, and

Section 5 articulates a multi-level ontology of the self as interface (the Avatar Model). The framework is then expanded to different scales:

Section 6 examines multi-scale rendering across biological and collective dynamics, and

Section 7 bridges the model with quantum coherence and non-locality, reconceiving the implicate order as a rendering substrate.

Section 8 further consolidates the multiscale dynamics (biological, cognitive, collective).

Section 9 details the significant implications for consciousness science and the hard problem, and

Section 10 addresses the model's limitations and empirical prospects.

Section 11 concludes with a summary of the unified post-Bohmian rendering ontology.

2. Background: Consciousness, Information, and Ontological Tensions

The relationship between consciousness and physical reality has long been shaped by the tension between classical assumptions of a fully instantiated world and empirical findings that challenge this view. Classical physical ontology presumes that objects possess intrinsic, observer-independent properties; perception is assumed to reveal, rather than construct, these properties. Yet empirical developments across disciplines undermine this assumption and motivate the need for a revised ontological framework.

2.1. Classical vs. Quantum Ontologies

Classical mechanics treats the world as a set of determinate states evolving through continuous trajectories governed by local interactions (Newton, 1687/1999). In this view, the universe is exhaustively defined at all times, and observation merely reveals preexisting features.

Quantum mechanics presents a radically different picture. The formalism assigns physical systems wave functions describing superpositions of potential states, which become determinate only in contexts of measurement (Dirac, 1930; Heisenberg, 1958). The measurement problem—why and how observation determines actual outcomes—exposes a fundamental gap in classical ontology (Maudlin, 1995). Empirically verified phenomena such as interference, non-local correlations, and contextuality suggest that reality may not be fully specified until interacted with (Aspect et al., 1982; Zeilinger, 1999). These results destabilize the assumption of a globally instantiated world and motivate considerations of observer-dependent instantiation.

2.2. Predictive Processing and the Construction of Experience

In parallel, cognitive neuroscience increasingly describes perception as an inferential process. According to predictive processing, the brain continuously generates top-down models that anticipate sensory inputs, updating these models via prediction error minimization (Friston, 2010; Clark, 2013; Hohwy, 2013). Perception is thus the brain’s best hypothesis about the causes of sensory stimulation, not a direct mapping of the world (Seth, 2015).

This model positions perception closer to controlled hallucination than to passive registration. The world experienced by an organism depends on its internal priors, sensorimotor capacities, and cognitive architecture. When applied ontologically, this raises important questions: if perception is model-based, what is the structure of the world those models interact with? How much of “reality” is rendered, and how much remains latent?

2.3. Bohm’s Implicate Order and Its Limitations

David Bohm proposed a non-local, dynamically enfolded order of reality “the implicate order” from which observable structures unfold (Bohm, 1980). In this view, the manifest world represents an explicate projection of deeper informational patterns, continuously unfolding and refolding in relation to the whole.

Bohm’s framework has several strengths:

it accommodates quantum non-locality without abandoning realism,

it reconceptualizes the relationship between parts and wholes,

it provides an ontological substrate for coherence phenomena.

However, the implicate order has limitations for contemporary consciousness studies:

1. Continuous specification: Bohm assumes the implicate order is fully defined at all times, whereas empirical and computational considerations suggest the world may not be globally instantiated.

2. Lack of perceptual mechanism: Bohm does not specify how conscious experience selectively brings aspects of the implicate order into determinate form.

3. No computational economy: The theory does not address the informational or energetic efficiency implied by biological and physical systems.

The rendering ontology proposed in this article builds on Bohm’s insights while addressing these limitations. It reframes the implicate order not as a continuously specified whole, but as a field of informational potentials actualized only through conscious access and inference.

3. A Post-Bohmian Rendering Ontology

This section introduces the core proposal: a rendering ontology in which consciousness brings informational potentials into determinate form through selective access, attention, and inferential updating. The framework develops Bohm’s insights while addressing limitations in his metaphysics and integrating findings from quantum theory, cognitive neuroscience, and computational models of perception.

3.1. Defining Ontological Rendering

The rendering model posits that reality is not fully instantiated “all at once” but exists as a field of informational potentials that become determinate only where and when conscious systems interact with them. In this view, consciousness does not observe a pre-existing world; it renders the subset of latent possibilities compatible with its biological, cognitive, and inferential constraints.

This rendering parallels several well-established phenomena:

In quantum measurement, systems remain in superposition until contextual interactions determine specific outcomes (Wheeler & Zurek, 1983; Leggett, 2002).

In predictive processing, perception emerges from active inference rather than passive registration (Friston, 2010; Hohwy, 2013).

In computational graphics, virtual environments exist as code and are rendered only where needed to conserve processing resources (Chalmers & McCollum, 2021).

The analogy is not metaphorical but structural: both quantum systems and perceptual systems exhibit efficiency constraints that support a model of selective instantiation rather than global computation. Rendering therefore describes the ontological process by which latent informational potentials are resolved into phenomenological forms.

3.2. Divergence from Bohm: Potentials, Not a Fully Enfolded Substrate

While Bohm’s implicate order provides a powerful conceptual foundation for non-locality and coherence, it assumes that the deeper order is continuously enfolded and fully specified at all times (Bohm, 1980). In contrast, the rendering ontology makes three departures:

1.Non-global specification

2. Mechanism of manifestation

Bohm distinguishes between implicate and explicate orders but does not provide a detailed mechanism for how experience selectively arises. The rendering model identifies such mechanism in attention, inference, and collapse.

3. Computational economy

Biological evolution and cognitive architecture show clear constraints on information processing. A globally instantiated reality would waste energy and complexity; rendering aligns with efficiency principles observed across physics and biology (Barrow & Tipler, 1986; Laughlin & Sejnowski, 2003).

Thus, while retaining Bohm’s insights regarding wholeness and non-locality, the rendering ontology reframes the deeper order as informational, latent, and instantiated through interaction.

3.3. Formal Principles of the Rendering Model

The rendering ontology can be articulated through three formal principles:

Principle 1: Latent Informational Fields

Reality at its most fundamental level consists of informational potentials, not determinate objects or states. These potentials correspond to probability amplitudes in quantum theory (Dirac, 1930), predictive priors in perceptual models (Clark, 2013), and latent structure in dynamical systems (Smolin, 2013).

Principle 2: Conscious Access as Rendering

Conscious systems resolve latent potentials into actualized states through selective attention, measurement-like interaction, and inferential updating. This process mirrors collapse in quantum measurement and model selection in predictive coding.

Principle 3: Local Instantiation and Distributed Stability

Reality becomes determinate only at the interface where organisms interact with potentials. Coherence across observers arises from shared constraints of the informational field—not from a pre-rendered world.

Together, these principles yield a unified ontology that integrates non-local physical potentials, inferential neural processing, and phenomenological experience.

4. Consciousness, Collapse, and Information

This section develops the central mechanism of the rendering ontology: the idea that consciousness functions as an active process that resolves latent informational potentials into determinate experiential states. The framework integrates insights from quantum measurement, predictive coding, and phenomenology to articulate how conscious access transforms undetermined potentials into perceptual instantiations.

4.1. Consciousness as an Active Process

Rather than being a passive observer of an already-instantiated world, consciousness actively shapes the structure of experience. Two major theoretical traditions support this view.

First, phenomenology has long emphasized that consciousness is intrinsically intentional and constructive (Husserl, 1913/1982; Merleau-Ponty, 1945). Perception arises not from sensory copying but from interpretive acts that bring meaning and structure to otherwise indeterminate data.

Second, cognitive neuroscience describes perception as an inferential process. Under the predictive processing framework, the brain continuously generates hypotheses about environmental causes and updates them through prediction error minimization (Rao & Ballard, 1999; Friston, 2010). Conscious perception corresponds to the winning model in this inferential competition (Hohwy, 2013).

In both traditions, consciousness is the process through which informational ambiguity is resolved.

4.2. Collapse of Potentials Under Attention

Quantum theory provides a parallel structure: physical systems exist in superpositions of possibilities until measurement interactions produce collapse into determinate states (von Neumann, 1932; Wheeler & Zurek, 1983). While the rendering ontology does not equate perceptual experience with quantum measurement, it highlights a shared principle: potentials become determinate only within specific interactional contexts.

Attention plays a role analogous to measurement. Empirical work in cognitive neuroscience shows that attention increases neural gain, enhances signal precision, and determines which perceptual hypotheses dominate (Feldman & Friston, 2010). Through attention, the organism selects which subset of informational potentials will be instantiated as phenomenological content.

Thus, conscious access functions as a collapse-like operation: it selects one outcome from a space of possibilities.

4.3. Qualia as “Query Acts”

Qualia (the subjective qualities of experience) pose a distinctive challenge for physicalist ontology. In the rendering framework, qualia are not intrinsic properties of objects or brain states but the outcome of a specific informational query performed by consciousness.

This model builds on works suggesting that qualia correspond to the system’s internal inference about the structure of sensory causes (Seth, 2014; Lau & Rosenthal, 2011). When consciousness “queries” the informational field, it retrieves a determinate experiential instantiation shaped by:

Qualia, therefore, represent the local instantiation of informational potentials through the act of conscious access. The redness of red, for example, is not a property in the external world but the output of an inferential mapping applied to specific wavelengths; an instantiation that arises only through the system’s internal query.

This conception aligns with both neurocomputational models and phenomenological descriptions of experience. It clarifies why qualia are both private and lawful: they depend on species-specific, organism-specific, and context-dependent transformations of underlying informational potentials.

5. The Avatar and the Interface: A Multi-Level Ontology of the Self

The rendering ontology distinguishes sharply between consciousness as the non-local capacity for informational access and the self as a localized construct implemented within the organism. This section develops a multi-level model of the self as an interface—an “avatar”—that enables action, memory, and narrative coherence within a dynamic environment. The purpose of distinguishing these levels is not metaphysical dualism but explanatory clarity: different layers of organization support different functional roles.

5.1. The Minimal Self and the Narrative Self

Philosophical and cognitive scientific accounts converge in recognizing that the self is not a unitary entity but a layered construct. Two levels are especially relevant:

The minimal self (Gallagher, 2000): the immediate sense of embodied first-person presence, grounded in sensorimotor contingencies, bodily ownership, and proprioception.

The narrative self (Dennett, 1991; Schechtman, 1996): a temporally extended, autobiographical model assembled from memory, social interaction, and linguistic structures.

The minimal self provides the anchor for agency and embodied interaction; the narrative self provides long-term continuity and social intelligibility. Both levels are constructed within the organism’s cognitive architecture and depend on neurocomputational processes such as predictive modeling and hierarchical inference (Metzinger, 2003; Hohwy, 2016).

5.2. The Self as Interface (Avatar Model)

In the rendering framework, the self is conceptualized as an interface system that mediates between consciousness and the informational environment. This view aligns with enactive and embodied approaches that understand cognition as adaptive regulation rather than passive representation (Thompson, 2007; Varela et al., 1991).

The avatar model proposes that:

1. Consciousness does not reside inside the avatar; rather, the avatar provides the constraints, sensory boundaries, and behavioral affordances through which consciousness interacts with the rendered world.

2. The self-model operates analogously to a graphical user interface: it presents a simplified, actionable version of the organism’s internal states and external environment.

3. The stability of the self is an adaptive requirement: without a persistent self-model, predictive processing would become computationally intractable, as the system would lack a stable prior for agency, memory, and action selection.

This aligns with computational theories of self-modeling, such as the “phenomenal self-model” proposed by Metzinger (2003), which argues that the self is a transparent representational construct enabling control and integration of bodily and cognitive processes.

5.3. Predictive Processing and the Construction of the Self

Within predictive processing, the self emerges as the hierarchical organization of priors that minimize prediction error across bodily states and external interactions (Hohwy, 2016; Clark, 2015). The self-model is a generative construct maintained because it produces efficient, coherent predictions.

This explains several key phenomena:

Bodily ownership illusions (Botvinick & Cohen, 1998) arise when prediction priors can be temporarily renegotiated.

Dissociation reflects a breakdown in the integration of hierarchical priors, where parts of the self-model lose synchrony with global inference.

Ego dissolution in meditation or psychedelic states (Millière, 2017) occurs when high-level priors governing the narrative and minimal self lose precision, allowing consciousness to access unfiltered states without the avatar constraints.

The rendering framework accommodates these phenomena by interpreting the self not as a metaphysical entity but as a computationally necessary organizational layer.

5.4. The Self as Locality Constraint

The model offers a broader claim: the self is the localization operator that allows a non-local consciousness to participate within a local, spatiotemporal environment.

This parallels work in:

Neuroscience of embodiment, which shows that self-location is constructed through multisensory integration (Blanke, 2012).

Philosophy of enaction, which views selfhood as the organism’s operational closure (Thompson, 2007).

Computational models of agency, where the sense of control arises from the match between predicted and actual sensory consequences (Friston, 2011).

In this view, the self is not an illusion but a functional constraint: it enables consciousness to inhabit a specific perspective, maintain continuity across time, and interact with a shared world. Thus, the avatar is neither the origin of consciousness nor its endpoint; it is the interface through which consciousness enters the rendering loop.

6. Multi-Scale Rendering: From Sensory Filters to Collective Coherence

The rendering framework posits that perception, cognition, and world-constitution occur across multiple scales, from the microscopic neural level to the macroscopic socio-phenomenological domain. This section articulates the mechanisms through which sensory systems, organismic constraints, and collective interaction generate a stable, shared reality. The goal is to situate “rendering” within a biologically grounded yet ontologically extended model of consciousness.

6.1. Sensory Filtering as Computational Efficiency

Biological organisms do not receive the world “as it is,” but instead process a narrow subset of environmental information determined by evolutionary constraints. Sensory systems act as filters that extract only the information relevant for the organism’s survival and action. This selective filtering is well-established in sensory neuroscience (Barlow, 1961; Laughlin, 1981) and aligns with the efficient coding hypothesis: organisms compress environmental information to minimize metabolic cost and maximize predictive accuracy.

Within the rendering framework:

1. The sensory system acts as the front-end renderer, determining which wavelengths, frequencies, and stimuli become available for further processing.

2. Perceptual experience is not a copy of external reality but a transformation, optimized for computational tractability.

3. Unperceived information is not “ignored” but remains unrendered, existing only as potential structure in the informational substrate.

This interpretation is congruent with views in perceptual psychology suggesting that conscious experience is a constructed model rather than a faithful depiction (Noë, 2004; Hoffman, 2019).

6.2. Neural Rendering: From Raw Inputs to Phenomenal Structure

Following sensory filtering, neural systems transform incoming signals through multilayer architectures resembling deep generative models. Hierarchical cortical processing (Felleman & Van Essen, 1991) and predictive coding (Friston, 2005) suggest that the brain renders experience by:

generating predictions across multiple timescales,

comparing sensory input with expected patterns, and

updating internal models to minimize prediction error.

In the rendering model:

Neural circuitry constitutes the mid-level renderer, transforming environmental potentialities into coherent, actionable percepts.

Phenomenological categories (color, sound, texture) arise from internally generated qualia models that map efficiently onto the sensory manifold.

Experience is thus the interface output of a multi-scale computational stack: informational substrate → sensory filter → neural generator → phenomenal field.

This stands in line with classical phenomenological accounts that emphasize the constructive, dimensional nature of perception (Merleau-Ponty, 1945) as well as computational neuroscience frameworks where the brain actively “models” reality.

6.3. Collective Rendering and the Phenomenology of Consensus

Individual rendering processes occur within a larger ecological and social context. Humans and other social organisms synchronize perceptions through communication, imitation, and shared affordances. The stability of the world depends not only on individual sensory-neural processes but on collective processes that align internal models.

Three mechanisms support collective coherence:

1. Shared constraints of embodiment

2. Cultural scaffolding

Language, norms, and shared practices generate collective priors that constrain individual interpretation (Clark, 1997; Gallagher, 2020).

3. Interactive alignment

Joint attention, coordination, and interpersonal coupling align perceptual fields across individuals (De Jaegher & Di Paolo, 2007).

In the rendering ontology, collective coherence arises because:

The informational substrate provides a consistent structure (Bohm’s implicit order).

Organisms render local instantiations of this structure through shared biological and cultural constraints.

Interaction dynamically updates internal models to maintain cross-person alignment.

The “world” as we experience it is therefore not merely the output of a single rendering engine (the brain) but emerges from interacting renders that stabilize each other through continuous negotiation.

6.4. Decoherence, Stability, and the Limits of the Render

Rendering is not perfect or absolute. Its limitations generate characteristic phenomena:

Ambiguous stimuli, where sensory input supports multiple interpretations (e.g., the Necker cube), reveal the competitive dynamics of predictive inference.

Hallucinations and dream states demonstrate the autonomy of internal generative models when sensory anchors weaken.

Collective delusions or socially reinforced beliefs show how rendering can be biased by top-down cultural priors.

At a metaphysical level, rendering stability parallels decoherence in quantum theory: what becomes classical (stable, public, shared) is the subset of informational patterns that can persist through environmental entanglement (Zurek, 2003). Similarly, what becomes phenomenally stable is the subset of interpretations that can persist across organisms with compatible priors. Thus, rendering is a multi-scale process: sensory, neural, interpersonal, and ecological layers jointly determine what “appears”.

7. Quantum Coherence, Non-Locality, and the Rendering Substrate

A post-Bohmian rendering framework must articulate how informational structures at the quantum scale relate to organism-level experience and collective phenomenology. This section proposes that the informational substrate described by Bohm as the implicate order can be reconceived as a rendering substrate, a non-local field of potential patterns that becomes instantiated through biological and cognitive processes of “localization.” Quantum coherence and non-locality are not metaphysical anomalies but natural consequences of this substrate.

7.1. Bohm’s Implicate Order as a Substrate of Potential Rendering

David Bohm (1980) proposed that the physical universe arises from a deeper layer of information “the implicate order” from which the explicate world unfolds. In the rendering interpretation:

The implicate order corresponds to an informational potential field, analogous to an uncollapsed state space.

The explicate order corresponds to rendered states, stabilized through interaction with observers (biological or instrumental).

Unfolding and enfolding become the rendering and unrendering cycles, modulated by attention, measurement, or environmental entanglement.

This reinterpretation preserves Bohm’s core insight, that the underlying reality is fundamentally relational and structured, while integrating it into a computational ontology.

7.2. Coherence as a Precondition for Rendering

Quantum coherence denotes the maintenance of stable phase relationships among system components. In standard quantum mechanics, coherence enables superposition, interference, and entanglement. In the proposed rendering framework, coherence is the pre-render state, where informational patterns remain:

Rendering requires a transition from this coherent potential into a localized, classical, actionable world-model. This mirrors the transition from probabilistic quantum amplitudes to definite outcomes through decoherence (Joos et al., 2003; Schlosshauer, 2007).

Thus, consciousness, or any measurement apparatus, acts as a localizing mechanism that selects one branch of potentiality for experiential instantiation.

7.3. Non-Locality as the Native Architecture of the Field

Quantum non-locality (Bell, 1964; Aspect et al., 1982) reveals that correlations can arise instantaneously across spatial distance, violating classical constraints on information transfer. From a rendering perspective, non-locality is not a paradox but a feature of the substrate:

Spatial separation is a property of the rendered world, not of the substrate itself.

The substrate (analogous to Bohm’s holomovement) is non-local by definition.

Rendered distance is a local constraint applied after instantiation, not before.

In other words, the rendering substrate behaves like a server hosting global information, where “distance” between rendered nodes is a property of the interface, not of the underlying architecture.

This aligns with Bohm’s holonomic model and finds resonance with contemporary quantum information frameworks that treat space-time as emergent from entanglement structure (Van Raamsdonk, 2010; Maldacena & Susskind, 2013).

7.4. The Brain as a Coherence-Sensitive System

The rendering model does not propose that the brain operates through macroscopic quantum coherence (a controversial position), but instead that:

1. The brain is sensitive to coherence patterns at macroscopic scales via synchronization, resonance, and phase alignment.

2. Neural coherence (e.g., gamma-band synchrony) serves as an analogue of quantum coherence at the experiential level:it integrates distributed activity into unified perceptual episodes (Varela et al., 2001).

3. This macro-coherence allows the brain to interface with the substrate, not by manipulating microscopic quantum states, but by providing a coherent classical “landing zone” where potential patterns can collapse into perceptual content.

In this regard, this framework aligns with Bohm & Hiley’s (1993) account of active information and with recent non-reductive proposals linking consciousness to large-scale coherence patterns (Engel, 2010; Seth & Bayne, 2022).

7.5. Rendering as Decoherence Guided by Consciousness

Within quantum theory, decoherence selects classical states by suppressing interference through environmental entanglement. In the rendering model:

Consciousness functions as a structured decoherence operator, selecting a coherent, meaningful pattern from the substrate.

The collapse is not arbitrary but context-dependent, guided by:

○

attention,

○

intentionality,

○

sensorimotor demands,

○

and shared cultural priors.

Thus, experience becomes the phenomenological projection of decoherence patterns shaped by biological and cognitive constraints.

The rendering substrate offers the latent space; consciousness selects the path through it.

7.6. From Quantum Potential to Phenomenal Instantiation

The rendering model proposes a mapping from quantum-level potentiality to phenomenological content:

1. Quantum potentials contain the full range of informational possibilities.

2. Organisms sample this space through sensorimotor channels.

3. Neural coherence structures stabilize a subset of patterns.

4. Consciousness instantiates these patterns as experience.

In this sense, qualia (the direct felt qualities of experience) are the interface layer of the rendering cycle. This framework does not violate physical laws; it simply interprets quantum structure as a prephenomenal substrate from which experiential features emerge through active rendering.

8. Rendering Across Scales: Biological, Cognitive, and Collective Dynamics

A post-Bohmian framework must account not only for the dependence of phenomenological instantiation on conscious attention, but also for how rendering behaviors emerge across multiple hierarchical scales of organization. From molecular and cellular processes to cognitive systems and collective agents, each layer implements specific informational constraints that shape what becomes manifest at the next. This section articulates a unified, scale-sensitive account grounded in contemporary neuroscience, quantum biology, predictive processing, and distributed cognition.

8.1. Biological Substrates as Local Render Engines

At the biological level, organisms act as local render engines that transform environmental information into usable, species-specific perceptual constructs. This principle aligns with von Uexküll’s notion of Umwelt, which shows that perceptual realities are not universal but niche-dependent informational slices (von Uexküll, 1909/2010). Bees render ultraviolet patterns; snakes render infrared gradients; bats render sonar-based spatial maps.

These perceptual modes do not merely filter reality—they constitute the organism’s specific manifestation of the world. Within the post-Bohmian framework, this implies that:

rendering is biologically parameterized

the quantum informational potential (Bohmian implicate order) becomes instantiated through the sensory architecture of each organism

perceptual diversity reflects heterogeneous “render pipelines” rather than competing ontologies

Recent work in quantum biology strengthens this view. Studies of avian magnetoreception (Cai et al., 2010) and photosynthetic coherence (Engel et al., 2007) demonstrate that biological systems maintain quantum-level informational access under specific constraints. Thus, the biological substrate acts simultaneously as classical interface and quantum-sensitive filter; precisely the hybrid architecture required in a rendering model.

8.2. Cognitive Rendering as Predictive Inference

At the cognitive scale, rendering corresponds to predictive processing dynamics. Brains do not passively receive sensory data but actively generate predictions, updating them through error minimization (Friston, 2010; Clark, 2013). Rendering, in this sense, is not a display but a computation:

This post-Bohmian proposal extends this by arguing that:

the predictive brain does not render into a pre-given physical world

rather, it selects and stabilizes one out of many quantum-informational potentials

attention acts as a “collapse operator” for actionable reality

qualia are not intrinsic properties but resolution modes of the render pipeline

This view complements ongoing attempts to integrate quantum state reduction with predictive coding (Atmanspacher, 2020; Gong, 2024), but differs in attributing a central generative role to consciousness itself, not merely to neural computation.

8.3. Collective Rendering and Shared Realities

Collective phenomena (languages, social norms, scientific models, cultural institutions) are emergent stabilization fields that coordinate individual render pipelines. As Hutchins (1995) and Gallagher (2013) argue, cognition extends across agents and artifacts. In a post-Bohmian reinterpretation:

each individual consciousness collapses a local portion of potential

coherence across systems arises through consensus-driven rendering

shared attention (e.g., joint attention) amplifies rendering stability

scientific paradigms and cultural schemas operate as “collective filters”

This aligns with Tononi and Koch’s integrated information framework (Tononi, 2008; Koch, 2017) and with the enactive tradition (Varela et al., 1991; Thompson, 2007), yet reframes them: collectives co-render a stable phenomenological world by synchronizing their instantiations across Bohmian implicate potentials.

Importantly, this is not solipsism or idealism. Nature itself imposes constraints (physical, biological, energetic) that narrow the solution space of possible renders. Collective stability emerges when multiple agents converge on overlapping ranges of instantiation.

8.4. Multiscale Rendering as a Unified Principle

Across biological, cognitive, and social scales, the same core dynamics appear:

1. A quantum-informational potential (Bohmian implicate order)

2. A scale-specific interface (sensory systems, neural networks, social structures)

3. A rendering operation (biological perception, predictive inference, collective synchronization)

4. A phenomenological instantiation (the explicit world)

This cross-scale homology supports the central claim:

Rendering is the universal mechanism that transforms non-local informational potentials into actionable realities.

It is not limited to human consciousness but is a generic property of complex systems interacting with the implicate order.

9. Implications for Consciousness Science: A Unified Ontological Model

The rendering framework carries significant implications for ongoing debates in consciousness research. Its central contribution is to unify three traditionally separate explanatory domains, quantum ontology, cognitive neuroscience, and phenomenology, within a single mechanistic model of how conscious experience arises and why reality appears as it does to biological observers.

9.1. Toward a Unified Ontology of Mind and World

Contemporary theoretical approaches to consciousness can be grouped broadly into several overlapping dimensions:

1. Physicalist or biological approaches, which attempt to reduce consciousness to neural, information-processing or field states (e.g., Dehaene, 2014; Hameroff & Penrose, 2014; Seth & Bayne, 2022).

2. Predictive and inferential processing approaches, which model perception and awareness as hierarchical inferential processes driven by prediction error and free-energy minimization (Friston, 2010; Hohwy, 2013; Ramstead et al., 2023).

3. Phenomenological and enactive approaches, which emphasize lived experience, embodiment and world-disclosure as irreducible dimensions of consciousness (Varela et al., 1991; Velmans, 2017).

Each of these approaches emphasizes a distinct axis of consciousness: substrate, mechanism and experience. Yet, they remain largely siloed in theory and method. Despite their insights, these frameworks remain epistemically disjointed.

The rendering model provides a shared ontological layer, an informational field of potentials resolved through conscious access, that connects them:

Quantum ontology describes the structure of potentials.

Predictive processing describes the mechanism of resolution.

Phenomenology describes the resulting experiential manifestation.

The framework therefore treats consciousness not as a byproduct of neural computation, but as a fundamental mode of operation that determines how information becomes reality for an observer.

9.2. Rethinking the “Hard Problem”

The hard problem of consciousness (Chalmers, 1995) arises under the assumption that subjective experience must be explained solely through physical mechanisms. The rendering framework reframes the issue:

This eliminates the need to reduce qualia to neural firing patterns while preserving the explanatory power of neuroscience. Biological implementation becomes the modulator, not the origin, of subjective experience.

By relocating qualitative experience to the interface between organism and informational field, the hard problem becomes a tractable question about how different interfaces instantiate different experiential resolutions of shared potentials.

9.3. Consciousness as a Constraint, Not an Emergent Epiphenomenon

Most scientific models treat consciousness as:

The rendering model reverses this hierarchy. Consciousness acts as an operational constraint that governs how physical states acquire determinate form. This aligns with Bohr’s and Wheeler’s views that observation participates in the creation of outcome ( Bohr, 1935; Wheeler, 1983), and with Bohm’s notion that consciousness and matter are different aspects of a deeper process (Bohm, 1980).

Here, consciousness determines:

which potentials become instantiated;

how perceptual hypotheses collapse;

how stable reality emerges across coordinated observers.

This elevation of consciousness from epiphenomenon to operative principle offers a new synthesis that traditional emergentist models cannot provide.

9.4. Relevance to Ongoing Empirical Debates

The rendering framework interfaces directly with several active areas in empirical consciousness research:

Neural Correlates of Consciousness (NCCs): In this ontology, NCCs are not generators of consciousness but necessary enabling conditions for perceptual instantiation. This parallels Network-Based Theories (Mashour et al., 2020) but shifts the ontological burden away from neural sufficiency.

Predictive Processing and Inference: Predictive coding describes the mechanism by which the system tests hypotheses against incoming signals. Rendering theory positions consciousness as the decisional layer that resolves inferential ambiguity.

Altered States and Clinical Disruptions: Because consciousness selects which potentials are instantiated, disruptions in neural precision or coherence (e.g., in schizophrenia, dissociation, or psychedelics) can be seen as alterations in the resolution process, not in consciousness itself. This yields testable predictions for clinical neuroscience.

Quantum Biology: If the informational field is non-local and coherence-sensitive, then quantum biological effects (Hameroff & Penrose, 2014; Lambert et al., 2013) become relevant not as explanations for consciousness, but as conditions that modulate the quality of the render.

Collective Perception and Social Ontology: Shared reality emerges from overlapping query structures across multiple observers. This provides a mechanistic explanation for intersubjective agreement without requiring absolute objectivity.

10. Discussion: Limitations and Empirical Prospects

The rendering framework provides a unified ontological model connecting quantum potentials, biological interfaces, and conscious instantiation. However, several limitations must be acknowledged to situate the proposal within ongoing scientific and philosophical discourse.

10.1. Conceptual Limitations

10.1.1. Ontological Neutrality of the Informational Field

While the model draws from Bohm’s implicate order and contemporary informational physics, the nature of the underlying informational field remains conceptually underdetermined. The framework treats the field as ontologically primitive, but additional theoretical work is needed to clarify whether it should be understood as:

a physical substrate in the quantum sense,

a computational medium,

a relational structure (e.g., Rovelli’s relational quantum mechanics; Rovelli, 1996), or

a phenomenological field akin to Husserlian “hyletic data” (Williford, 2013).

Clarifying this status is essential for integrating the model with existing metaphysical frameworks.

10.1.2. Consciousness as Operational Constraint

The model positions consciousness as an active operator resolving potentials, but must specify the precise mechanisms by which consciousness exerts its constraining role on informational states. To address this, the rendering framework can be operationalized by aligning the "collapse operation" with established neurocognitive architectures.

Specifically, the resolution of latent potentials into a determinate perceptual state (Principle 2) finds a direct mechanistic analogue in the Global Workspace Theory (GWT). According to GWT, conscious access is achieved through global neuronal ignition—a non-linear, large-scale activation that broadcasts a single, winning hypothesis across the cortex (Dehaene, 2014; Baars, 1988). In the rendering ontology, this ignition functions as the neural correlate of the collapse operator, selecting and stabilizing the most precise potential from the implicit informational field for global instantiation.

Furthermore, the Integrated Information Theory (IIT) offers a measure for the capacity of the rendering interface. The Φ metric, which quantifies a system's ability to integrate information beyond its parts (Tononi, 2008), can be interpreted as the resolving power of the conscious render engine. A high Φ would correspond to a system with a strong capacity to constrain and unify a vast state space of potentials into a highly detailed, coherent, and determinate phenomenal experience (Koch, 2017). This integration transforms the metaphysical analogy of "collapse" into a quantifiable function of neural computation, linking the act of resolving ambiguity to measurable brain dynamics.

10.2. Empirical Limitations

10.2.1. Indirect Observability

Because the informational field is defined as pre-phenomenal, its properties cannot be measured directly. Scientific validation depends on examining:

behavioral signatures of prediction error minimization,

neurophysiological markers of attentional collapse,

and coherence/disruption patterns under altered states of consciousness.

Such indirect methods constrain the granularity of empirical testing.

10.2.2. Quantum–Cognitive Bridging Problem

Although quantum principles provide a strong conceptual analogy for the collapse of potentials, establishing empirical bridges between quantum processes and macroscopic neural dynamics remains challenging. While some evidence for quantum biological coherence exists (Lambert et al., 2013; Marletto & Vedral, 2017), the magnitude and relevance of these effects at organismal scales are still under debate.

10.3. Empirical Prospects

Despite these limitations, the rendering framework generates several testable or semi-testable predictions:

10.3.1. Precision Modulation Hypothesis

If consciousness collapses inferential ambiguity, then conditions that alter neural precision (e.g., psychedelics, schizophrenia, sensory deprivation) should directly modify the granularity and stability of the perceptual render. This aligns with recent findings in computational psychiatry (Adams et al., 2022).

10.3.2. Cross-Species Rendering Differences

Given the Umwelt principle, different organisms should instantiate systematically different renders of the same latent information. Comparative neurophenomenology could quantify differences in perceptual instantiation across species.

10.3.3. Collective Rendering and Intersubjective Stabilization

The model predicts that shared attention stabilizes perceptual outcomes across observers. This hypothesis could be explored via hyperscanning EEG/MEG studies of coordinated attention.

10.3.4. Altered States as Relaxed Rendering Regimes

The rendering ontology predicts that psychedelics and meditation should reduce hierarchical constraints on the percept, increasing access to latent potentials. This prediction aligns with recent neuroimaging work (Carhart-Harris & Friston, 2019).

In this sense, the rendering ontology moves beyond both classical physicalism and purely phenomenological accounts, offering instead a post-Bohmian synthesis in which consciousness participates actively in the unfolding of reality. The world is not merely observed, nor merely imagined, it is rendered.

11. Conclusion: Toward a Unified Rendering Ontology

This work has proposed a unified ontological framework, the rendering ontology, that integrates quantum potentials, biological interfaces, and conscious instantiation into a single coherent model. The central claim is that consciousness is not a passive byproduct of neural activity but an active operator that resolves informational potentials into determinate experiential states. Reality, under this view, is neither fully predetermined nor entirely constructed; it is rendered through the dynamic interplay between an informational field of latent possibilities and the organismic interfaces that transform those possibilities into perceptual forms.

The framework synthesizes insights from three major domains that have historically remained conceptually isolated:

Quantum Ontology: Suggests physical systems exist as probabilistic potentials prior to measurement (Bohm’s Implicate Order).

Predictive Cognitive Neuroscience: Models perception as hierarchical inference constrained by attention, precision, and expectation.

Phenomenology: Emphasizes the constitutive role of consciousness in disclosing the world as meaningful presence.

Crucially, the rendering ontology addresses the operational gap by providing a mechanistic analogue for the collapse function. The resolution of informational potentials into determinate reality is realized at the cognitive scale through the mechanism of global neuronal ignition (Dehaene, 2014; Baars, 1988). This ignition, characteristic of conscious access, acts as the neural collapse operator, selecting the winning perceptual hypothesis and stabilizing it across the cortical network. Furthermore, the Integrated Information Theory (IIT) (Tononi, 2008) provides a quantitative measure (Φ) for the resolving power of the interface, suggesting that the capacity for detailed, coherent qualia directly correlates with the system’s complexity in integrating informational constraints.

By integrating these domains, the rendering ontology provides a structure in which latent potentials, biological constraints, and lived experience are not competing explanations but complementary levels of a single process. This synthesis yields three key implications:

1. Reframing the Hard Problem: The model redefines qualia as instantiations—the determinate outputs of conscious querying—rather than intrinsic properties of matter, making the question of experience tractable.

2. Consciousness as Operator: It bridges subpersonal neural dynamics with the phenomenological structure of experience, positioning consciousness as the operational constraint that collapses inferential ambiguity and guides the unfolding of reality.

3. Testable Psychopathology: It offers a natural account of altered states and psychopathology, viewing them as shifts in rendering parameters (e.g., precision modulation, aligning with computational psychiatry) rather than as metaphysical breaks.

In conclusion, the world is not merely observed, nor merely imagined; it is rendered through a constrained, active, multi-scale process, transforming informational potentiality into lived reality.

Author Contributions

Tonatiu Campos-García: author of this manuscript and is responsible for all aspects of the research. This includes the conceptualization and original development of the Post-Bohmian Rendering Ontology, the synthesis of theoretical frameworks (Quantum Theory, Predictive Processing, and Phenomenology), the drafting of the manuscript, and the final intellectual revision and approval of the submitted version.

Funding

The author, Tonatiu Campos-García, was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship funded by the Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (Secihti), which covered the time dedicated to the research and conceptual development of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

My gratitude goes out to the editor and the reviewers. I appreciate their stimulating questions and valuable guidance, which were instrumental in the improvement of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Bohr, N. Can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete? Physical Review 1935, 48, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J.A. Law without law. In Quantum Theory and Measurement; Wheeler, J.A., Zurek, W.H., Eds.; Princeton University Press, 1983; pp. 182–213. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, J.A.; Zurek, W.H. Quantum Theory and Measurement; Princeton University Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phénoménologie de la perception (1945). Libraqire Gallimard, Paris 1976, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K. The free-energy principle: A unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2010, 11, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A. Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2013, 36, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohwy, J. The Predictive Mind; Oxford University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bohm, D. Wholeness and the implicate order; Routledge, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Von Neumann, J. Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics; Princeton University Press, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Leggett, A.J. Testing the limits of quantum mechanics: Motivation, state of play, prospects. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2002, 14, R415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.P.; Ballard, D.H. Predictive coding in the visual cortex: A functional interpretation of some extra-classical receptive-field effects. Nature neuroscience 1999, 2, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Uexküll, J. Streifzüge durch die Umwelten von Tieren und Menschen; Springer, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Barwich, A.S. Smellosophy: What the Nose Tells the Mind; Harvard University Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, I.; Cohen, I.B.; Whitman, A. The Principia: Mathematical principles of natural philosophy; (Original work published 1687); Univ of California Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dirac, P.A.M. The Principles of Quantum Mechanics; Oxford University Press, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg, W. Physics and philosophy: The revolution in modern science; Vladimir Djambov, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Maudlin, T. Three measurement problems. Topoi 1995, 14, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspect, A.; Dalibard, J.; Roger, G. Experimental test of Bell’s inequalities using time-varying analyzers. Physical Review Letters 1982, 49, 1804–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeilinger, A. Experiment and the foundations of quantum physics. Reviews of Modern Physics 1999, 71, S288–S297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, D.J. Reality+: Virtual worlds and the problems of philosophy; Penguin UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow, J.D.; Tipler, F.J. The Anthropic Cosmological Principle; Oxford University Press, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin, S.B.; Sejnowski, T.J. Communication in neuronal networks. Science 2003, 301, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husserl, E. Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy; (Original work published 1913); Kersten, F., Translator; Springer, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, H.; Friston, K. Attention, uncertainty, and free-energy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2010, 4, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, A.K. A predictive processing theory of sensorimotor contingencies: Explaining the puzzle of perceptual presence and its absence in synesthesia. Cognitive Neuroscience 2014, 5, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, H.; Rosenthal, D. Empirical support for higher-order theories of conscious awareness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2011, 15, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S. Philosophical conceptions of the self: Implications for cognitive science. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2000, 4, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennett, D.C. Consciousness Explained; Little, Brown, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Schechtman, M. The Constitution of Selves; Cornell University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Metzinger, T. Being No One; MIT Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hohwy, J. The self in predictive processing. In Open MIND.; Metzinger, T., Windt, J.M., Eds.; MIND Group, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E. Mind in Life: Biology, Phenomenology, and the Sciences of Mind; Harvard University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, F.J.; Thompson, E.; Rosch, E. The Embodied Mind; MIT Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A. Surfing Uncertainty: Prediction, Action, and the Embodied Mind; Oxford University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick, M.; Cohen, J. Rubber hands ‘feel’ touch that eyes see. Nature 1998, 391, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millière, R. Looking for the self: Phenomenology, neurophysiology and philosophical significance of drug-induced ego dissolution. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2017, 11, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanke, O. Multisensory brain mechanisms of bodily self-consciousness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2012, 13, 556–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. What is optimal about motor control? Neuron 2011, 72, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, H.B. Possible principles underlying the transformation of sensory messages. Sensory communication 1961, 1, 217–233. [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin, S. A simple coding procedure enhances a neuron’s information capacity. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 1981, 36, 910–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noë, A. Action in Perception; MIT Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, D. The case against reality: Why evolution hid the truth from our eyes; WW Norton & Company, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Felleman, D.; Van Essen, D. Distributed hierarchical processing in primate cerebral cortex. Cerebral Cortex 1991, 1, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friston, K. A theory of cortical responses. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2005, 360, 815–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A. Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again; MIT Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, S. Action and Interaction; Oxford University Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Jaegher, H.; Di Paolo, E. Participatory sense-making: An enactive approach to social cognition. Phenomenology and the cognitive sciences 2007, 6, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, W.H. Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Reviews of Modern Physics 2003, 75, 715–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joos, E.; Zeh, H.D.; Kiefer, C.; Giulini, D.; Kupsch, J.; Stamatescu, I.O. Decoherence and the Appearance of a Classical World in Quantum Theory; Springer, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosshauer, M. Decoherence and the Quantum-to-Classical Transition; Springer, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J.S. On the einstein podolsky rosen paradox. Physics Physique Fizika 1964, 1, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Raamsdonk, M. Building up space–time with quantum entanglement. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2010, 19, 2429–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J.; Susskind, L. Cool horizons for entangled black holes. Fortschritte der Physik 2013, 61, 781–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, F.; Lachaux, J.P.; Rodriguez, E.; Martinerie, J. The brainweb: Phase synchronization and large-scale integration. Nature reviews neuroscience 2001, 2, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohm, D.; Hiley, B. The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory; Routledge, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, A.K. Gamma oscillations, coherence, and consciousness. In The Neurology of Consciousness; Academic Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Seth, A.K.; Bayne, T. Theories of consciousness. Nature reviews neuroscience 2022, 23, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Guerreschi, G.G.; Briegel, H.J. Quantum control and entanglement in a chemical compass. Physical review letters 2010, 104, 220502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.S.; Calhoun, T.R.; Read, E.L.; Ahn, T.K.; Mančal, T.; Cheng, Y.C.; Fleming, G.R. Evidence for wavelike energy transfer through quantum coherence in photosynthetic systems. Nature 2007, 446, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z. Computational Explanation of Consciousness: A Predictive Processing-based Understanding of Consciousness; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Atmanspacher, H. Quantum approaches to consciousness; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins, E. Cognition in the Wild; MIT press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, S. A pattern theory of self. Frontiers in human neuroscience 2013, 7, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tononi, G. Consciousness as integrated information: A provisional manifesto. The Biological Bulletin 2008, 215, 216–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, C. Consciousness: Confessions of a romantic reductionist; MIT press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene, S. Consciousness and the brain: Deciphering how the brain codes our thoughts; Penguin, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hameroff, S.; Penrose, R. Consciousness in the universe: A review of the ‘Orch OR’ theory. Physics of Life Reviews 2014, 11, 39–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramstead, M.J.D.; Albarracín, M.; Kiefer, A.; Klein, B.; Fields, C.; Friston, K.; Safron, A. The inner-screen model of consciousness: Applying the free energy principle directly to the study of conscious experience. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.02205. [Google Scholar]

- Velmans, M. Dualism, reductionism, and reflexive monism. The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness 2017, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, D. Facing up to the problem of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies 1995, 2, 200–219. [Google Scholar]

- Mashour, G.A.; Roelfsema, P.; Changeux, J.P.; Dehaene, S. Conscious processing and the global neuronal workspace hypothesis. Neuron 2020, 105, 776–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, N.; Chen, Y.N.; Cheng, Y.C.; Li, C.M.; Chen, G.Y.; Nori, F. Quantum biology. Nature Physics 2013, 9, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, B.J. A cognitive theory of consciousness; Cambridge University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rovelli, C. Relational quantum mechanics. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 1996, 35, 1637–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Friston, K. REBUS and the anarchic brain: Toward a unified model of the brain action of psychedelics. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2019, 108, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.A.; Stephan, K.E.; Brown, H.R.; Frith, C.D.; Friston, K.J. The computational psychosis theory: A Bayesian account of delusions and hallucinations. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2022, 23, 620–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).