Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Oxytocin (OXT) has demonstrated potential therapeutic effects in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) through mechanisms such as reducing amyloid-β (Aβ) accumulation and tau deposition, as well as exerting antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. A recent study further revealed that OXT can decrease acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity in liver and kidney tissues, suggesting that its effects on Aβ and tau pathology may be mediated, at least in part, through AChE inhibition. Based on this rationale, a series of OXT derivatives were designed, synthesized, and evaluated using protein-protein interaction analysis, molecular docking, in vitro AChE inhibition assays, enzyme kinetics, and antioxidant assays. Docking and protein-protein interaction studies showed that OXT and its analogues fit well within the 20 Å gorge of the AChE active site, engaging both the catalytic active site (CAS) and the peripheral anionic site (PAS). In vitro AChE inhibition assays revealed promising activity, with OXT (Cmpd.16) and analogue 7 (Cmpd.7) exhibiting IC₅₀ values of 8.5 µM and 3.6 µM, respectively. Kinetic analysis determined inhibition constants (Kᵢ) of 45 µM for Cmpd.16 and 6 µM for Cmpd.7, with both compounds following a mixed-type inhibition mechanism. Furthermore, antioxidant evaluations indicated potential neuroprotective properties. In conclusion, OXT analogues act as dual-binding site AChE inhibitors, as supported by docking, protein-protein interaction, and kinetic analyses, and display greater inhibitory activity than OXT itself. These findings suggest that OXT analogues represent promising candidates for further development as AChE inhibitors for AD therapy.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

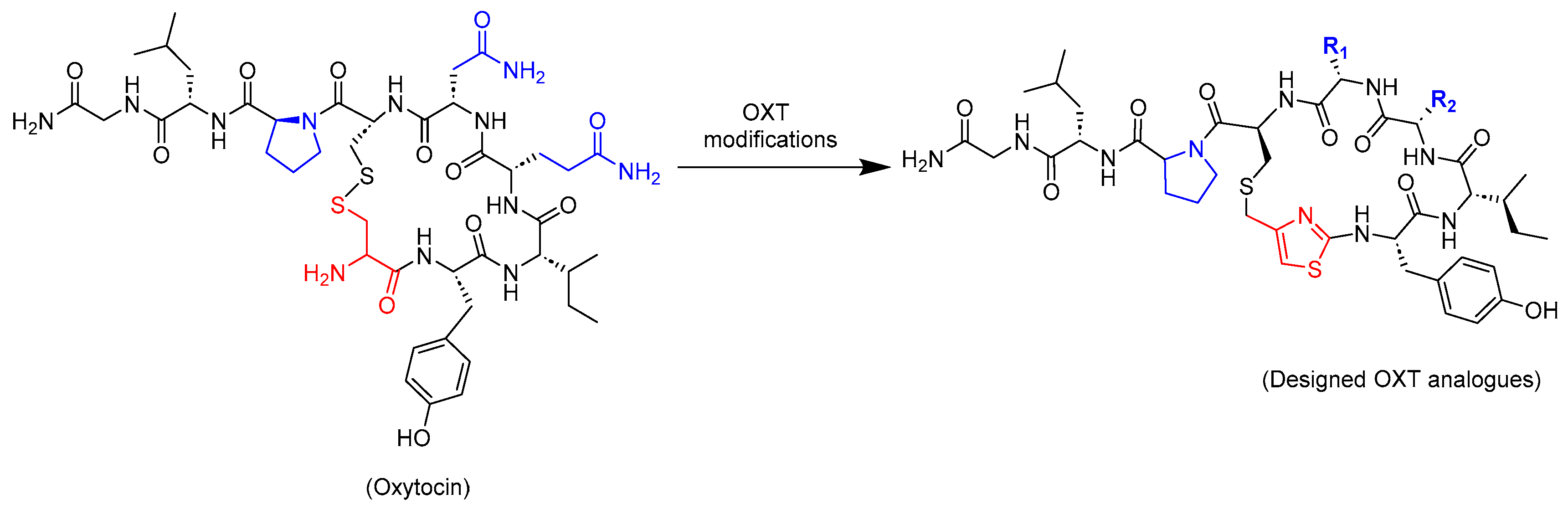

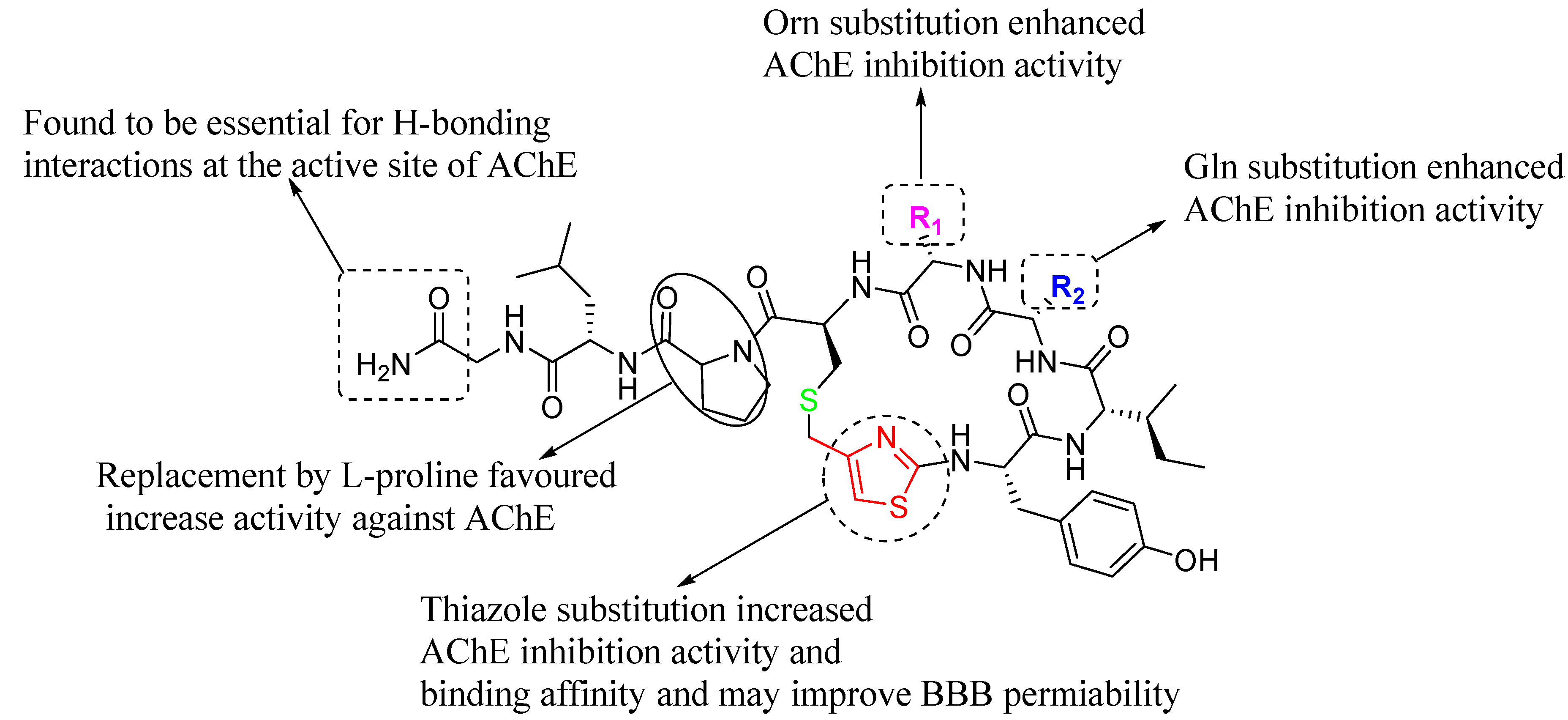

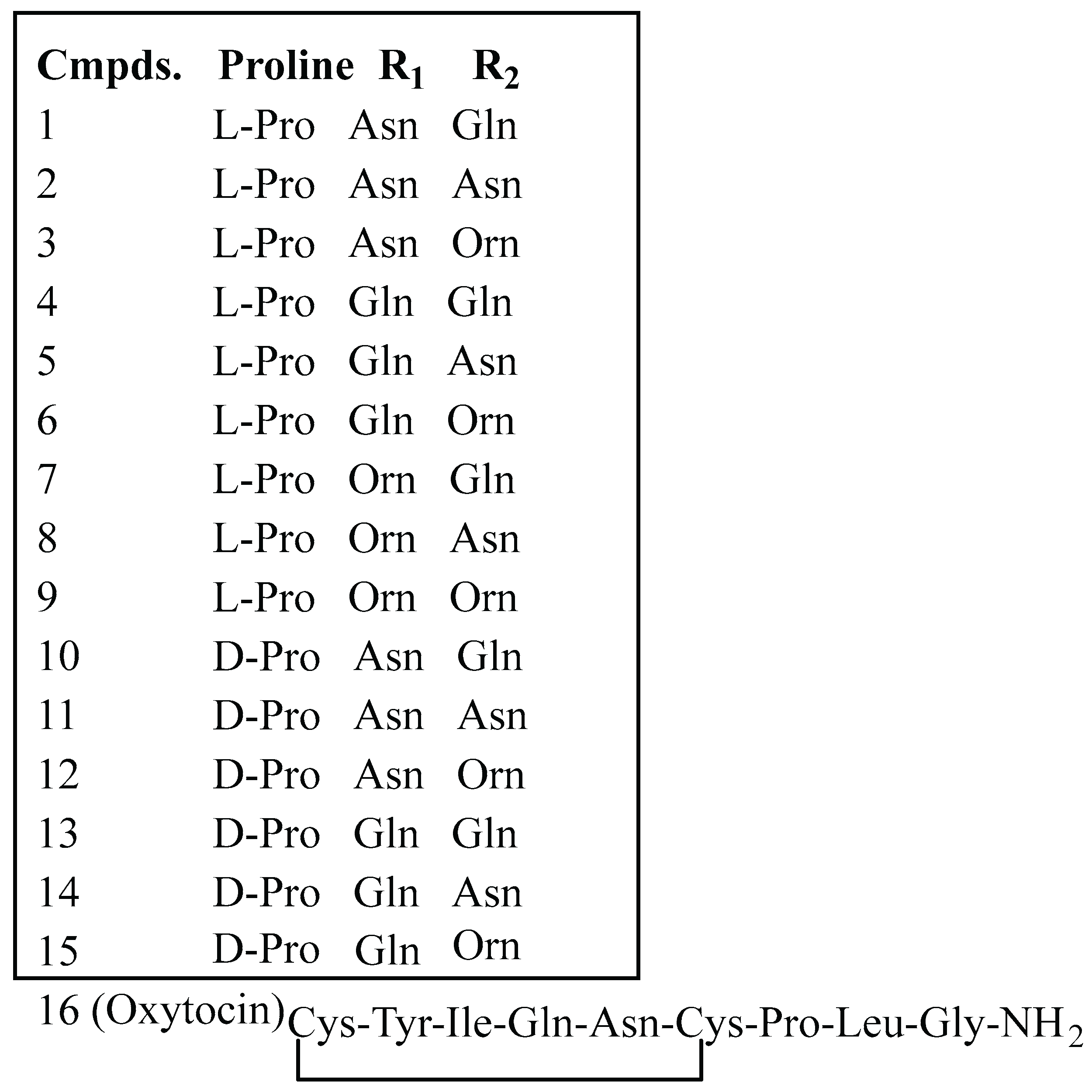

2.1. Design Strategy of Oxytocin Analogues

2.2. Protein-Protein Interaction Studies

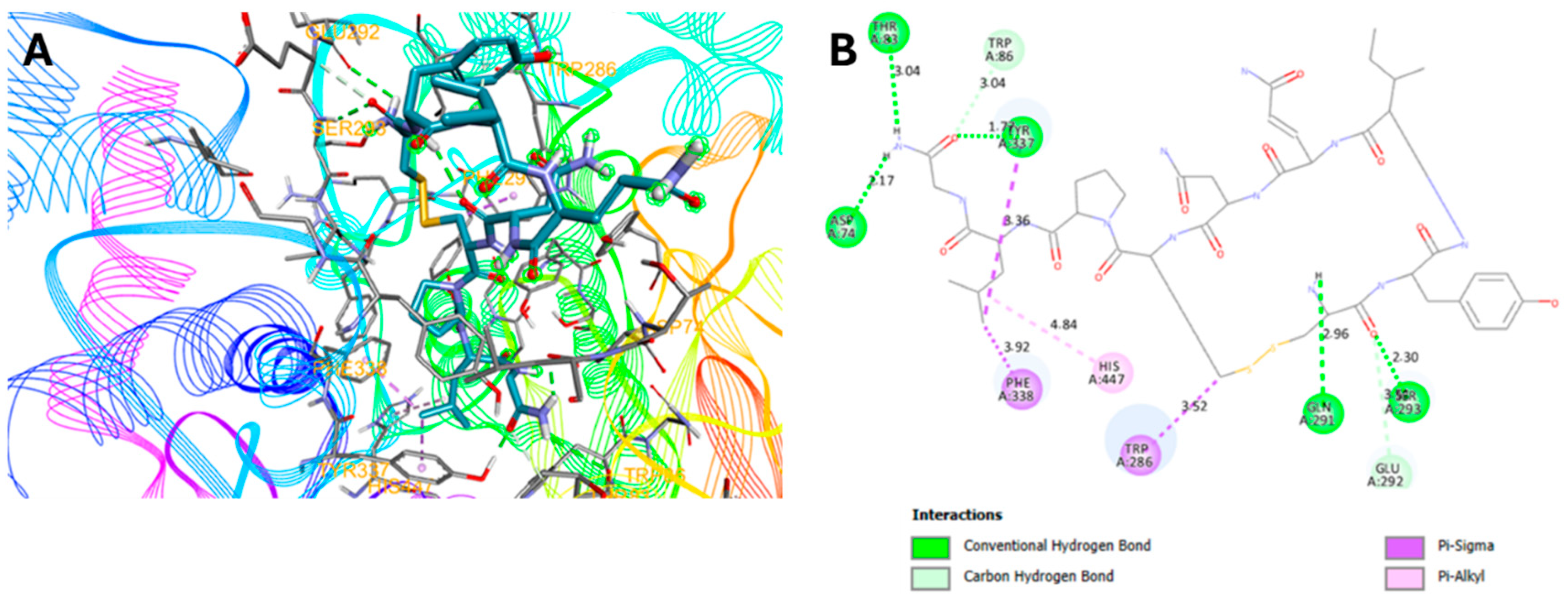

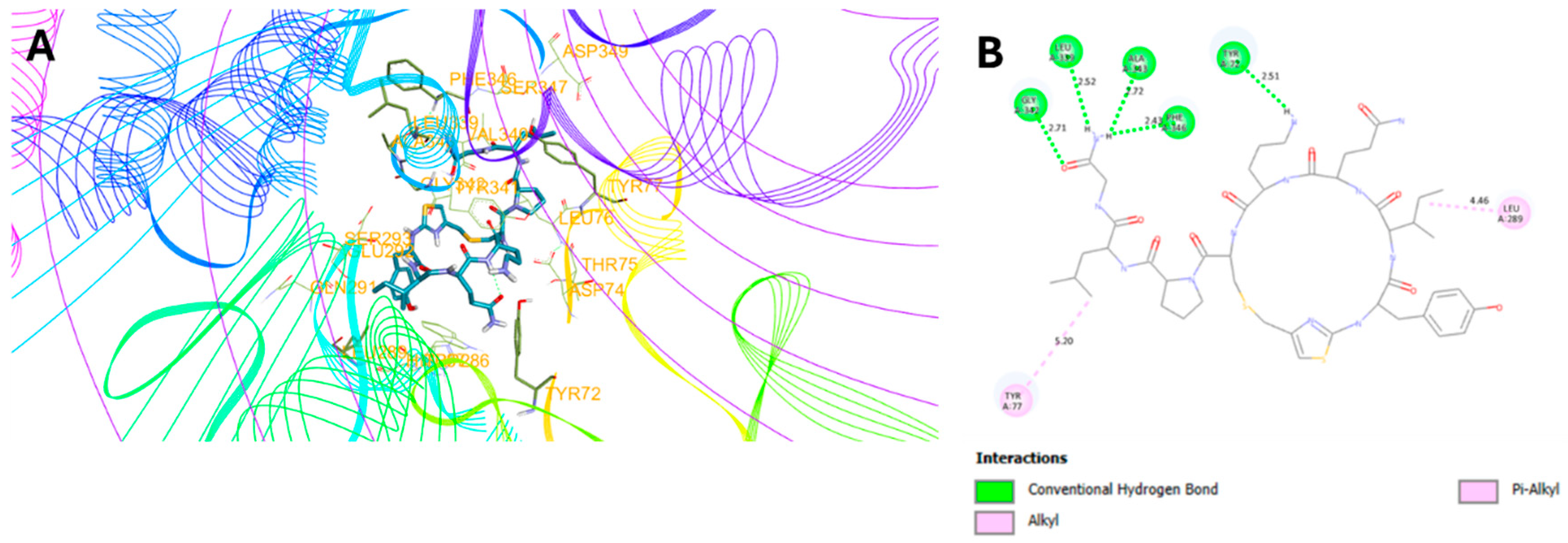

2.3. Molecular Docking Studies

2.4. In Vitro AChE Inhibition Activities

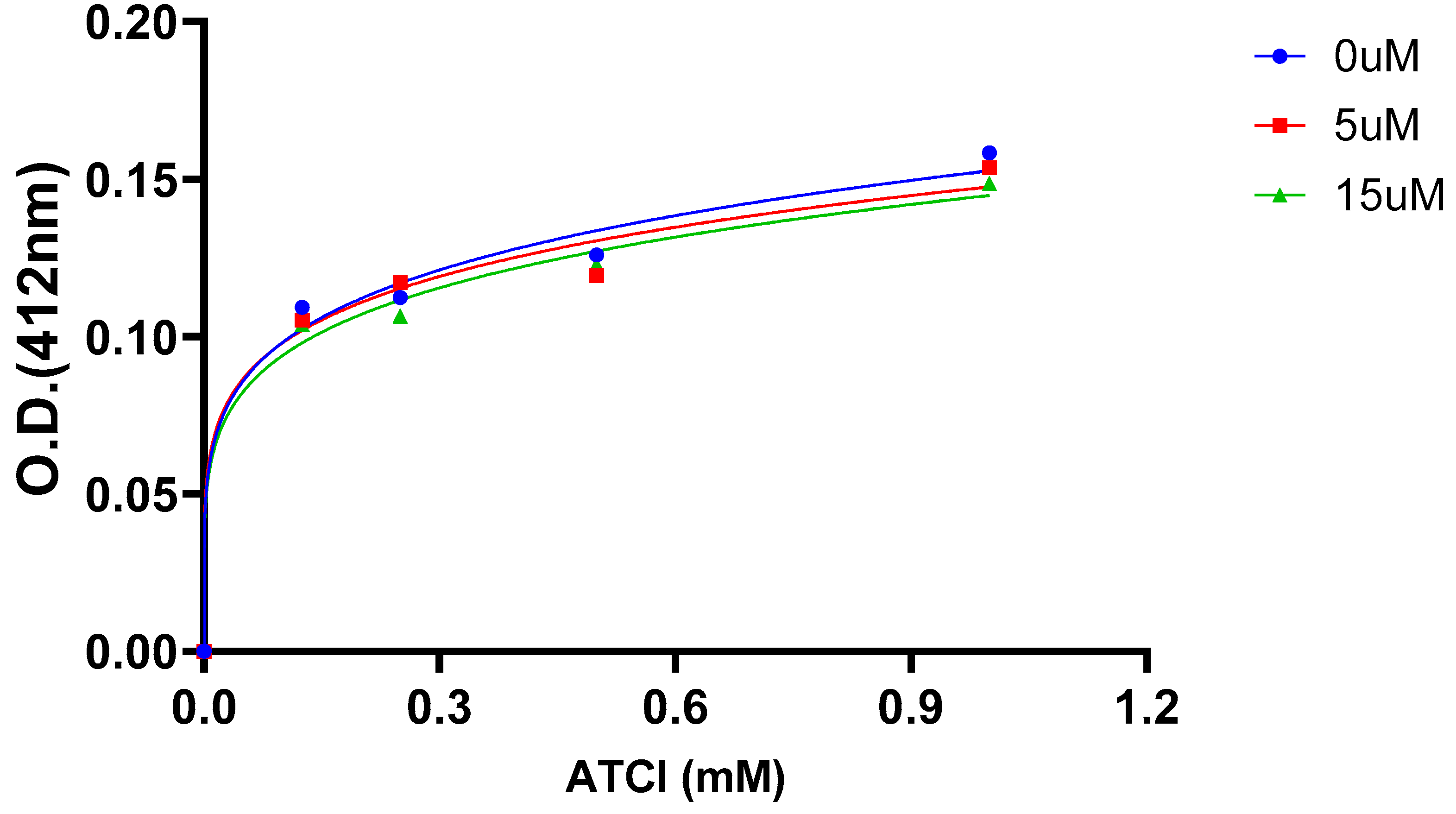

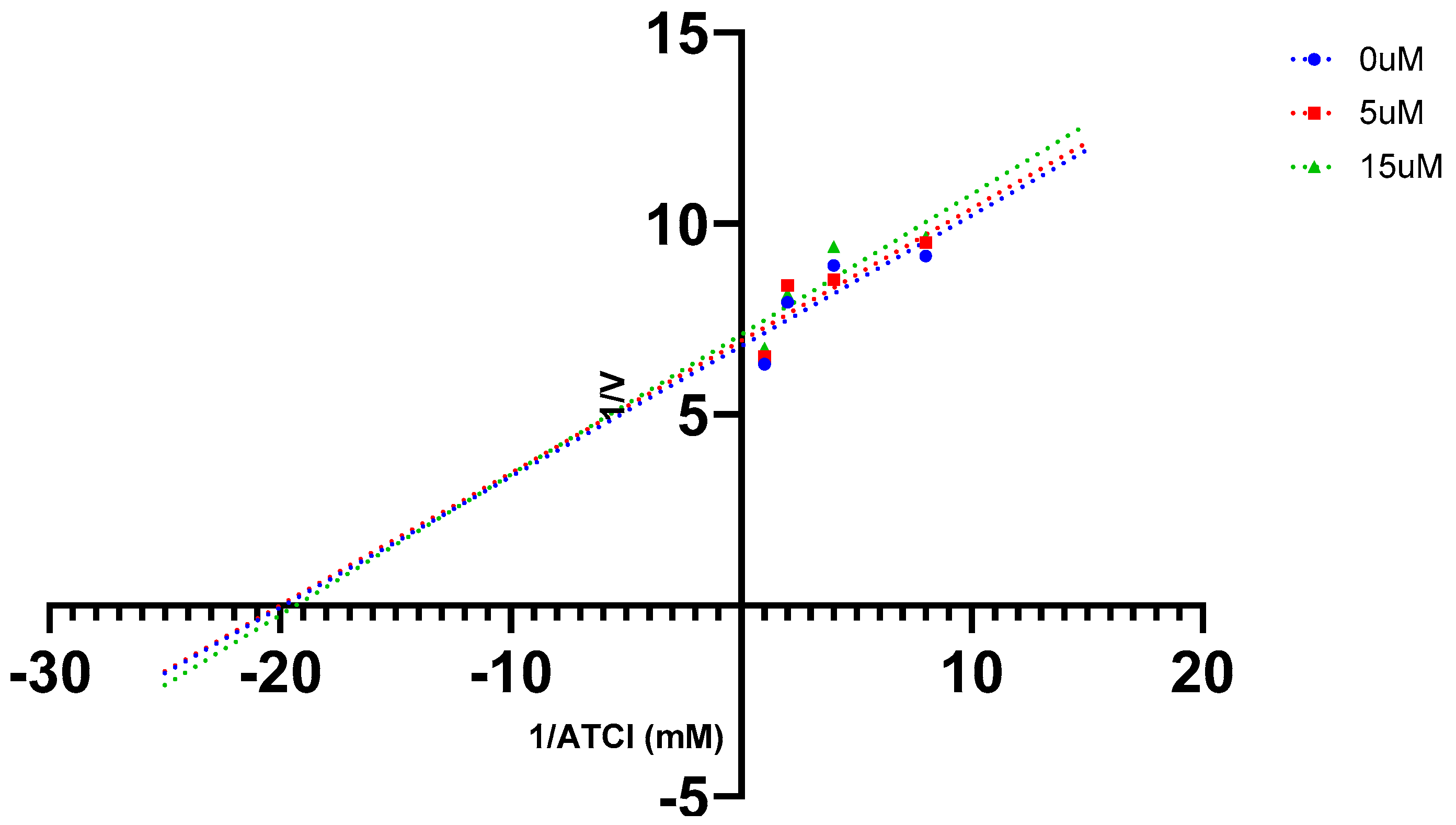

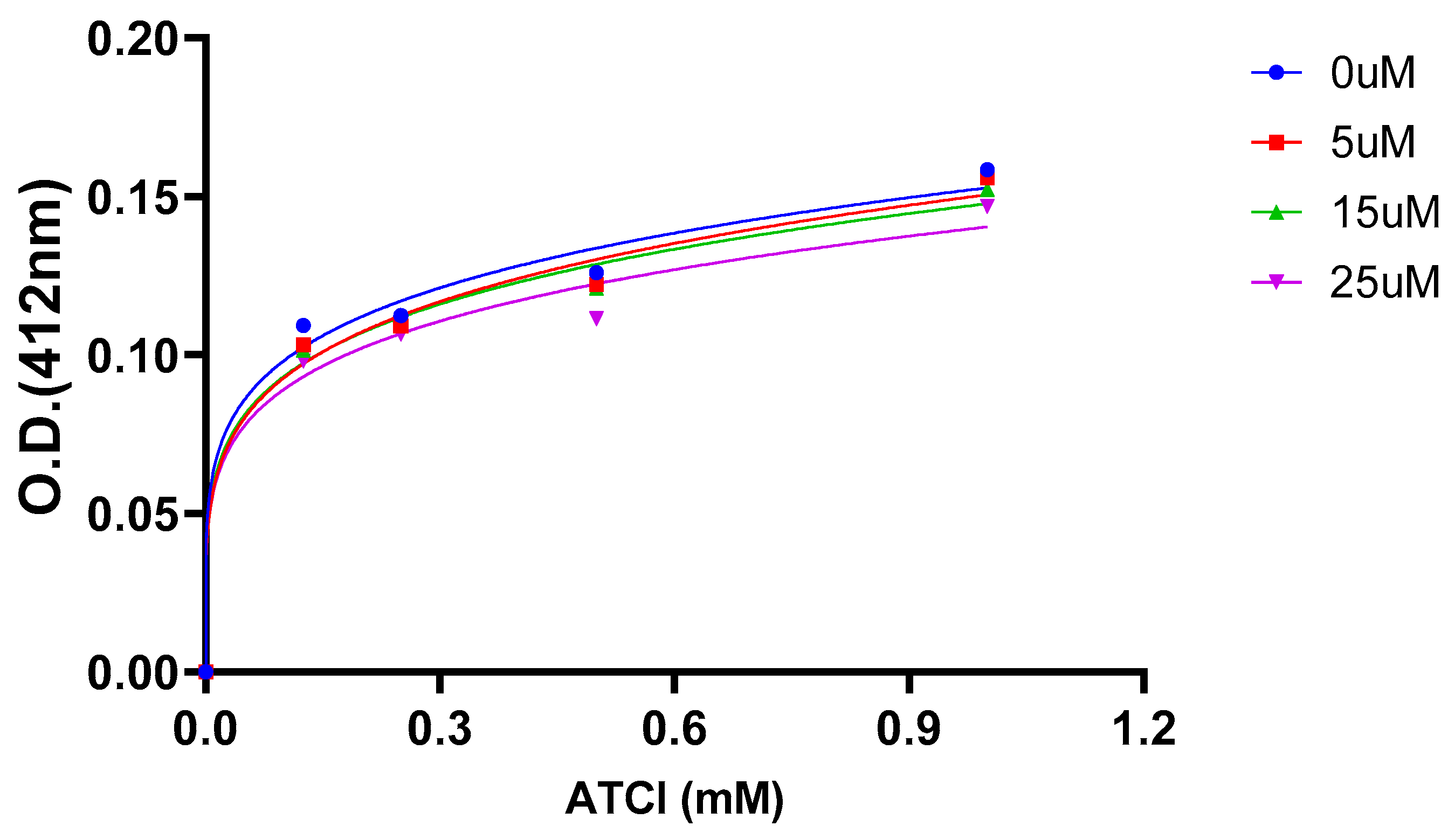

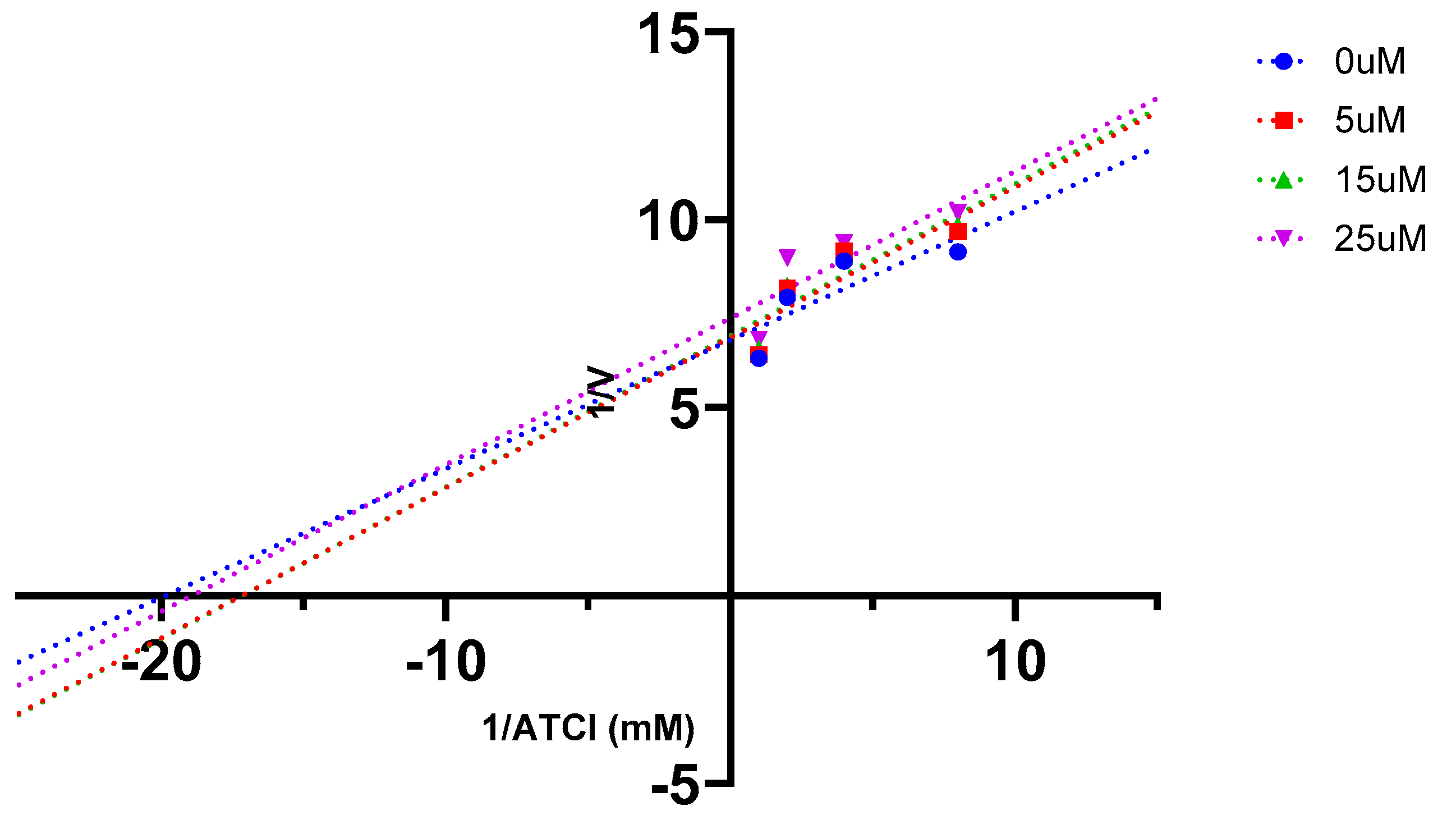

2.5. AChE Kinetics Studies

2.6. Antioxidant Activities

2.7. In silico physicochemical and ADMET evaluation

2.8. SARs

3. Materials and Methods

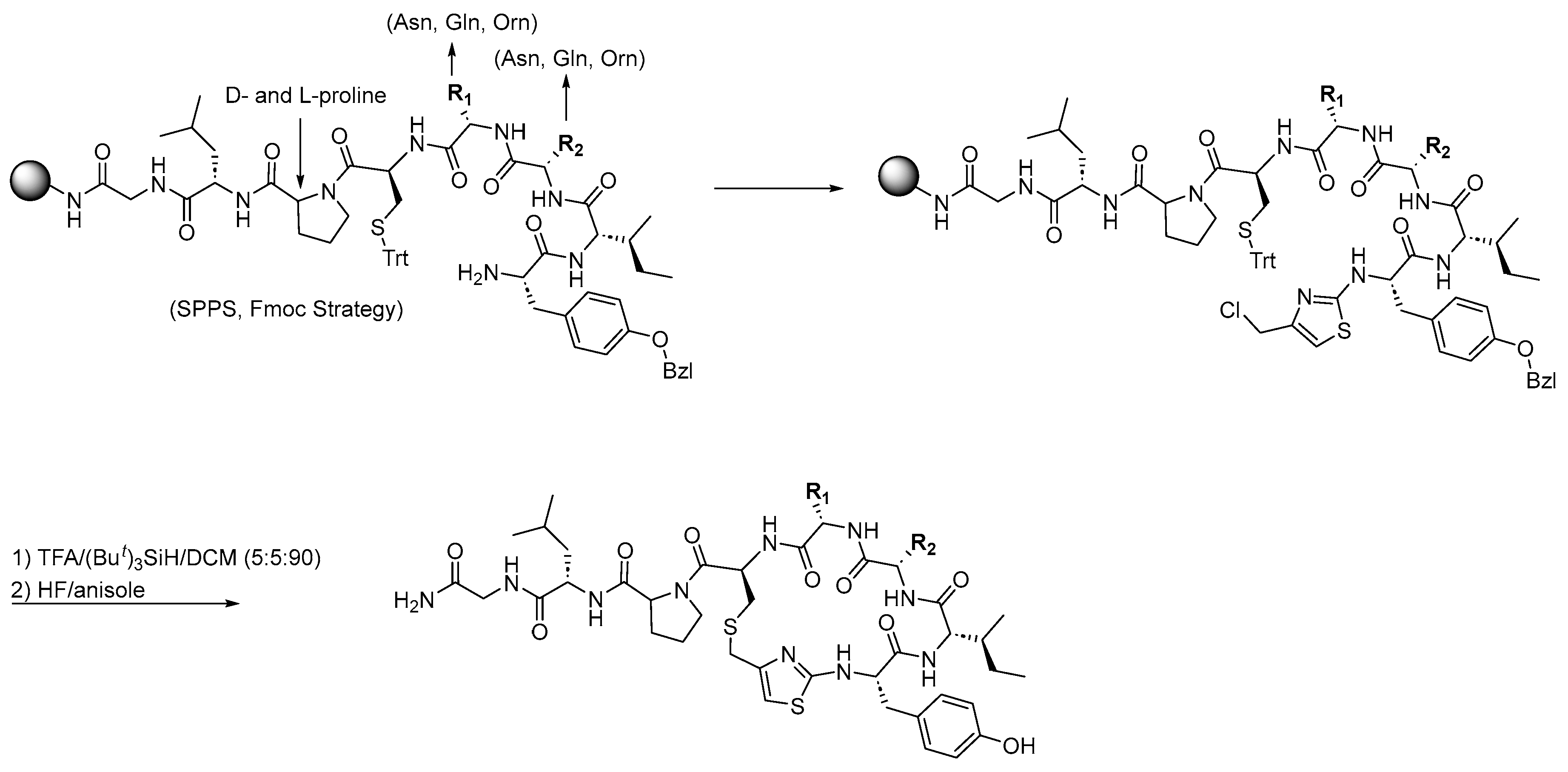

3.1. Synthesis of Oxytocin Analogues: As Outlined in Scheme 1, a 100 mg Sample of p-Methylbenzhydrylamine Hydrochloride (MBHA·HCl) Resin (CHEM-IMPEX INTERNATIONAL, 1.15 mequiv/g, 100–200 mesh, 1% DVB) Was Used per Peptide and Enclosed in a Sealed Polypropylene Mesh Bag for the Parallel Synthesis of 16 Different Compounds (Table 1). Prior to Synthesis, the Resin Was Neutralized with 50 mL of 5% Diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) in Dichloromethane (DCM)

3.2. Computational Studies

3.3. In Silico Prediction

3.4. In Vitro Enzyme Inhibition Assays

3.5. Enzyme Kinetics Assays

3.6. Antioxidant Assays

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Takahashi, J.; Yamada, D.; Nagano, W.; Saitoh, A. The Role of Oxytocin in Alzheimer's Disease and Its Relationship with Social Interaction. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimpl, G.; Fahrenholz, F. The oxytocin receptor system: structure, function, and regulation. Physiol Rev 2001, 81, 629–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, W. W.; Kahloon, M.; Fakhry, H. Oxytocin role in enhancing well-being: a literature review. J Affect Disord 2011, 130, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosfeld, M.; Heinrichs, M.; Zak, P. J.; Fischbacher, U.; Fehr, E. Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature 2005, 435, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, S.; Kent, M.; Bardi, M.; Lambert, K. G. Enriched Environment Exposure Enhances Social Interactions and Oxytocin Responsiveness in Male Long-Evans Rats. Front Behav Neurosci 2018, 12, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, J.; Karimi, M.; Soltanpour, N.; Moharrerie, A.; Rouhzadeh, Z.; Lotfi, H.; Hosseini, S. A.; Jafari, S. Y.; Roudaki, S.; Moeeini, R.; et al. Oxytocin-mediated social enrichment promotes longer telomeres and novelty seeking. Elife 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumsta, R.; Heinrichs, M. Oxytocin, stress and social behavior: neurogenetics of the human oxytocin system. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2013, 23, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A. Oxytocin and human social behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 2010, 14, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamrani-Sharif, R.; Hayes, A. W.; Gholami, M.; Salehirad, M.; Allahverdikhani, M.; Motaghinejad, M.; Emanuele, E. Oxytocin as neuro-hormone and neuro-regulator exert neuroprotective properties: A mechanistic graphical review. Neuropeptides 2023, 101, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, D. M.; Fallon, D.; Hill, M.; Frazier, J. A. The role of oxytocin in psychiatric disorders: a review of biological and therapeutic research findings. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2013, 21, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceanga, M.; Spataru, A.; Zagrean, A. M. Oxytocin is neuroprotective against oxygen-glucose deprivation and reoxygenation in immature hippocampal cultures. Neurosci Lett 2010, 477, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karelina, K.; Stuller, K. A.; Jarrett, B.; Zhang, N.; Wells, J.; Norman, G. J.; DeVries, A. C. Oxytocin mediates social neuroprotection after cerebral ischemia. Stroke 2011, 42, 3606–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Martínez, F.; Uvnäs-Moberg, K.; Petersson, M.; Olausson, H. A.; Jiménez-Estrada, I. Neuropeptides as neuroprotective agents: Oxytocin a forefront developmental player in the mammalian brain. Prog Neurobiol 2014, 123, 37–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Mesulam, M. M.; Cuello, A. C.; Farlow, M. R.; Giacobini, E.; Grossberg, G. T.; Khachaturian, A. S.; Vergallo, A.; Cavedo, E.; Snyder, P. J.; et al. The cholinergic system in the pathophysiology and treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2018, 141, 1917–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, C. A.; Hardy, J.; Schott, J. M. Alzheimer's disease. European Journal of Neurology 2018, 25, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twarowski, B.; Herbet, M. Inflammatory Processes in Alzheimer's Disease-Pathomechanism, Diagnosis and Treatment: A Review. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weller, J.; Budson, A. Current understanding of Alzheimer's disease diagnosis and treatment. F1000Res 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soria Lopez, J. A.; González, H. M.; Léger, G. C. Alzheimer's disease. Handb Clin Neurol 2019, 167, 231–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellani, R. J.; Perry, G. Pathogenesis and disease-modifying therapy in Alzheimer's disease: the flat line of progress. Arch Med Res 2012, 43, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantzavinos, V.; Alexiou, A. Biomarkers for Alzheimer's Disease Diagnosis. Curr Alzheimer Res 2017, 14, 1149–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbodo, J. O.; Agbo, C. P.; Njoku, U. O.; Ogugofor, M. O.; Egba, S. I.; Ihim, S. A.; Echezona, A. C.; Brendan, K. C.; Upaganlawar, A. B.; Upasani, C. D. Alzheimer's Disease: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Interventions. Curr Aging Sci 2022, 15, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akıncıoğlu, H.; Gülçin, İ. Potent Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors: Potential Drugs for Alzheimer's Disease. Mini Rev Med Chem 2020, 20, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadharajan, A.; Davis, A. D.; Ghosh, A.; Jagtap, T.; Xavier, A.; Menon, A. J.; Roy, D.; Gandhi, S.; Gregor, T. Guidelines for pharmacotherapy in Alzheimer's disease - A primer on FDA-approved drugs. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2023, 14, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldmacher, D. S. Treatment of Alzheimer Disease. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2024, 30, 1823–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athar, T.; Al Balushi, K.; Khan, S. A. Recent advances on drug development and emerging therapeutic agents for Alzheimer's disease. Mol Biol Rep 2021, 48, 5629–5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasasty, V.; Radifar, M.; Istyastono, E. Natural Peptides in Drug Discovery Targeting Acetylcholinesterase. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zare-Zardini, H.; Tolueinia, B.; Hashemi, A.; Ebrahimi, L.; Fesahat, F. Antioxidant and cholinesterase inhibitory activity of a new peptide from Ziziphus jujuba fruits. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2013, 28, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siano, A.; Garibotto, F. F.; Andujar, S. A.; Baldoni, H. A.; Tonarelli, G. G.; Enriz, R. D. Molecular design and synthesis of novel peptides from amphibians skin acting as inhibitors of cholinesterase enzymes. J Pept Sci 2017, 23, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asen, N. D.; Okagu, O. D.; Udenigwe, C. C.; Aluko, R. E. In vitro inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity by yellow field pea (Pisum sativum) protein-derived peptides as revealed by kinetics and molecular docking. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 1021893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, P.; Gupta, V.; Das, G.; Pradhan, K.; Khan, J.; Gharai, P. K.; Ghosh, S. Peptide-Based Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitor Crosses the Blood-Brain Barrier and Promotes Neuroprotection. ACS Chem Neurosci 2018, 9, 2838–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, K.; Finnman, J.; Flipo, M.; Galyean, R.; Schteingart, C. D. On the mechanism of degradation of oxytocin and its analogues in aqueous solution. Biopolymers 2013, 100, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, K. Design of Oxytocin Analogs. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 2001, 235–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremsmayr, T.; Schober, G.; Kaltenböck, M.; Hoare, B. L.; Brierley, S. M.; Muttenthaler, M. Oxytocin Analogues for the Oral Treatment of Abdominal Pain. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2024, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshanski, I.; Shalev, D. E.; Yitzchaik, S.; Hurevich, M. Determining the structure and binding mechanism of oxytocin-Cu(2+) complex using paramagnetic relaxation enhancement NMR analysis. J Biol Inorg Chem 2021, 26, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocyigit, U. M.; Taşkıran, A.; Taslimi, P.; Yokuş, A.; Temel, Y.; Gulçin, İ. Inhibitory effects of oxytocin and oxytocin receptor antagonist atosiban on the activities of carbonic anhydrase and acetylcholinesterase enzymes in the liver and kidney tissues of rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2017, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Ou, Y.; Feng, Z.; Xiong, Z.; Li, K.; Che, M.; Qi, S.; Zhou, M. Oxytocin attenuates hypothalamic injury-induced cognitive dysfunction by inhibiting hippocampal ERK signaling and Aβ deposition. Transl Psychiatry 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ganainy, S. O.; Soliman, O. A.; Ghazy, A. A.; Allam, M.; Elbahnasi, A. I.; Mansour, A. M.; Gowayed, M. A. Intranasal Oxytocin Attenuates Cognitive Impairment, β-Amyloid Burden and Tau Deposition in Female Rats with Alzheimer's Disease: Interplay of ERK1/2/GSK3β/Caspase-3. Neurochem Res 2022, 47, 2345–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Huang, G. The biological activities of butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 146, 112556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colović, M. B.; Krstić, D. Z.; Lazarević-Pašti, T. D.; Bondžić, A. M.; Vasić, V. M. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: pharmacology and toxicology. Curr Neuropharmacol 2013, 11, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H. J.; Park, J. H.; Jeong, Y. J.; Hwang, J. W.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Seol, E.; Kim, I. W.; Cha, B. Y.; Seo, J.; et al. Donepezil ameliorates Aβ pathology but not tau pathology in 5xFAD mice. Mol Brain 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Haertel, C.; Maelicke, A.; Montag, D. Galantamine slows down plaque formation and behavioral decline in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Chen, X.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Y. Galantamine attenuates amyloid-β deposition and astrocyte activation in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Exp Gerontol 2015, 72, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ayllón, M. S.; Small, D. H.; Avila, J.; Sáez-Valero, J. Revisiting the Role of Acetylcholinesterase in Alzheimer's Disease: Cross-Talk with P-tau and β-Amyloid. Front Mol Neurosci 2011, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danta, C. C.; Chaudhari, P.; Nefzi, A. Targeting Acetylcholinesterase with Oxytocin: A New Avenue in Alzheimer's Disease Therapeutics. ACS Chem Neurosci 2025, 16, 2336–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, M. D.; Shine, C.; Scanlan, E. M.; Petracca, R. Thioether analogues of the pituitary neuropeptide oxytocin via thiol-ene macrocyclisation of unprotected peptides. Org Biomol Chem 2022, 20, 8192–8196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, N.; Bizimana, T.; Kayumba, P. C.; Khuluza, F.; Heide, L. Stability of Oxytocin Preparations in Malawi and Rwanda: Stabilizing Effect of Chlorobutanol. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2020, 103, 2129–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nefzi, A.; Ostresh, J. M.; Yu, Y.; Houghten, R. A. Combinatorial chemistry: libraries from libraries, the art of the diversity-oriented transformation of resin-bound peptides and chiral polyamides to low molecular weight acyclic and heterocyclic compounds. J Org Chem 2004, 69, 3603–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghten, R. A. General method for the rapid solid-phase synthesis of large numbers of peptides: specificity of antigen-antibody interaction at the level of individual amino acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1985, 82, 5131–5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nefzi, A. Hantzsch based macrocyclization approach for the synthesis of thiazole containing cyclopeptides. Methods Mol Biol 2013, 1081, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantak, M. P.; Rayala, R.; Chaudhari, P.; Danta, C. C.; Nefzi, A. Synthesis of Diazacyclic and Triazacyclic Small-Molecule Libraries Using Vicinal Chiral Diamines Generated from Modified Short Peptides and Their Application for Drug Discovery. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, R.; White, P.; Offer, J. Advances in Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis. J Pept Sci 2016, 22, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, G. B. Methods for removing the Fmoc group. Methods Mol Biol 1994, 35, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, D. M. M. Thirteen decades of peptide synthesis: key developments in solid phase peptide synthesis and amide bond formation utilized in peptide ligation. Amino Acids 2018, 50, 39–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P. R.; Oddo, A. Fmoc Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis. Methods Mol Biol 2015, 1348, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nefzi, A.; Arutyunyan, S.; Fenwick, J. E. Two-Steps Hantzsch Based Macrocyclization Approach for the Synthesis of Thiazole Containing Cyclopeptides. J Org Chem 2010, 75, 7939–7941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, H. M.; Eans, S. O.; Ganno, M. L.; Davis, J. C.; Dooley, C. T.; McLaughlin, J. P.; Nefzi, A. Antinociceptive activity of thiazole-containing cyclized DAMGO and Leu-(Met) enkephalin analogs. Org Biomol Chem 2019, 17, 5305–5315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H. M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T. N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I. N.; Bourne, P. E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dileep, K. V.; Ihara, K.; Mishima-Tsumagari, C.; Kukimoto-Niino, M.; Yonemochi, M.; Hanada, K.; Shirouzu, M.; Zhang, K. Y. J. Crystal structure of human acetylcholinesterase in complex with tacrine: Implications for drug discovery. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 210, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallakyan, S.; Olson, A. J. Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. Methods Mol Biol 2015, 1263, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellman, G. L.; Courtney, K. D.; Andres, V., Jr.; Feather-Stone, R. M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol 1961, 7, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khunnawutmanotham, N.; Sooknual, P.; Batsomboon, P.; Ploypradith, P.; Chimnoi, N.; Patigo, A.; Saparpakorn, P.; Techasakul, S. Synthesis, Antiacetylcholinesterase Activity, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Aporphine-benzylpyridinium Conjugates. ACS Med Chem Lett 2024, 15, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asen, N. D.; Aluko, R. E. Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activities of antioxidant peptides obtained from enzymatic pea protein hydrolysates and their ultrafiltration peptide fractions. J Food Biochem 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkis, A.; Khoa, T.; Lee, Y. Z.; Ng, K. Screening Flavonoids for Inhibition of Acetylcholinesterase Identified Baicalein as the Most Potent Inhibitor. Journal of Agricultural Science 2015, 7, 26–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, P. J. The use of Dixon plots to study enzyme inhibition. Biochim Biophys Acta 1972, 289, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, F.; Wu, G.; Gui, F.; Li, H.; Xu, L.; Hao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ding, X.; Qin, X. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of sesquiterpenoids isolated from Laggera pterodonta. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1074184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M. A.; Hassan, M.; Aziz Ur, R.; Siddiqui, S. Z.; Shah, S. A. A.; Raza, H.; Seo, S. Y. Synthesis, enzyme inhibitory kinetics mechanism and computational study of N-(4-methoxyphenethyl)-N-(substituted)-4-methylbenzenesulfonamides as novel therapeutic agents for Alzheimer's disease. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanarro, C. M.; Gütschow, M. Hyperbolic mixed-type inhibition of acetylcholinesterase by tetracyclic thienopyrimidines. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2011, 26, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepetkin, I. A.; Nurmaganbetov, Z. S.; Fazylov, S. D.; Nurkenov, O. A.; Khlebnikov, A. I.; Seilkhanov, T. M.; Kishkentaeva, A. S.; Shults, E. E.; Quinn, M. T. Inhibition of Acetylcholinesterase by Novel Lupinine Derivatives. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malomo, S. A.; Aluko, R. E. Kinetics of acetylcholinesterase inhibition by hemp seed protein-derived peptides. J Food Biochem 2019, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, I. H.; Ozkul, B.; Erisik Tanriover, D.; Ozkul, O.; Elgormus, C. S.; Gur, S. G.; Sogut, I.; Uyanikgil, Y.; Cetin, E. O.; Erbas, O. Protective effect of oxytocin through its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant role in a model of sepsis-induced acute lung injury: Demonstrated by CT and histological findings. Exp Lung Res 2021, 47, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilic-Kurt, Z.; Konyar, D.; Okur, H.; Kaplan, A.; Boga, M. Some heterocycles connected to substituted piperazine by 1,3,4-oxadiazole linker: Design, synthesis, anticholinesterase and antioxidant activity. Journal of Molecular Structure 2025, 1321, 139854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güngör, S. A.; Şahin, İ.; Güngör, Ö.; Tok, T. T.; Köse, M. Synthesis, Biological Evaluation and Docking Study of Mono- and Di-Sulfonamide Derivatives as Antioxidant Agents and Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors. Chem Biodivers 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Waterbeemd, H.; Gifford, E. ADMET in silico modelling: towards prediction paradise? Nat Rev Drug Discov 2003, 2, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, L. Strategic approaches to optimizing peptide ADME properties. Aaps j 2015, 17, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okella, H.; Okello, E.; Mtewa, A. G.; Ikiriza, H.; Kaggwa, B.; Aber, J.; Ndekezi, C.; Nkamwesiga, J.; Ajayi, C. O.; Mugeni, I. M.; et al. ADMET profiling and molecular docking of potential antimicrobial peptides previously isolated from African catfish, Clarias gariepinus. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 9, 1039286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, W. S.; Battersby, J. E. A new micro-test for the detection of incomplete coupling reactions in solid-phase peptide synthesis using 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulphonic acid. Anal Biochem 1976, 71, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postma, T. M.; Albericio, F. N-Chlorosuccinimide, an Efficient Reagent for On-Resin Disulfide Formation in Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis. Organic Letters 2013, 15, 616–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Scientific Reports 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Ketkar, R.; Tao, P. ADMETboost: a web server for accurate ADMET prediction. J Mol Model 2022, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

| Cmpds. | Binding affinity (Kcal/mol) | No. of H-bonding: (Interacting residues of AChE) |

AChE inhibition IC50 (µM)* |

Antioxidant IC50 (µM)* |

| 1 | -6.7 | 4: (V73, W286, G345, F346) | 4.6 ± 3.8 | 54.63 ± 1.2 |

| 2 | -6.8 | 6: (V340, W286, G342, F346, Y341, S293) | 4.9 ± 4.2 | 73.19 ± 2.3 |

| 3 | -5.9 | 4: (V73, W286, Q279, H287) | 4.9 ± 4.1 | 48.92 ± 1.6 |

| 4 | -5.3 | 1: (Q279) | 4.9 ± 5.6 | 76.93 ± 1.6 |

| 5 | -6.3 | 3: (T75, L76, S293) | 5.4 ± 4.0 | 76.30 ± 2.4 |

| 6 | -7.8 | 8: (V282, V288, W286, H287, L289, G342, A343, F346) | 4.4 ± 3.9 | 46.74 ± 9.1 |

| 7 | -7.4 | 5: (Y72, L339, G342, A343, F346) | 3.6 ± 4.5 | 100.5 ± 8.5 |

| 8 | -6.0 | 2: (T75, L76) | 10.83 ± 6.7 | No inhibition |

| 9 | -6.5 | 4: (D74, S293, V340, G342) | 60.46 ± 5.1 | 47.24 ± 5.4 |

| 10 | -6.9 | 5: (P88, N87, N89, R90, D131) | 5.9 ± 3.9 | 4.8 ± 6.3 |

| 11 | -7.5 | 6: (V73, N283, H287, E292, F346) | 10.11 ± 4.7 | 22.1 ± 4.3 |

| 12 | -7.1 | 6: (T75, W286, S293, Y341, F346) | 19.71 ± 2.6 | 31.15 ± 3.3 |

| 13 | -6.4 | 7:(Y341, E292, G342, A343, F346) | 4.74 ± 2.1 | 25.82 ± 3.1 |

| 14 | -7.5 | 3: (L76, G342, F346) | 4.34 ± 1.5 | 27.41 ± 2.4 |

| 15 | 83.9 | 3: (T75, V282, W286) | 25.36 ± 3.7 | 25.27 ± 6.2 |

| 16 (Oxytocin) |

-7.3 | 5: (D74, T83, Q291, S293, Y337) | 8.5 ± 4.5 | 29.00 ± 2.8 |

| Galantamine | -5.0 | 1: (Q279) | 0.32 ± 5.6 | … |

| Rivastigmine | -5.7 | 2: (R296, H405) | 3.4 ± 22.7 | … |

| Trolox | … | … | … | 9.38 ± 0.42 |

| Ascorbic acid | … | … | … | 5.47 |

| Cmpds. | Inhibition constant (Ki) (µM) | Mechanism of inhibition |

| 7 | 6 | Mixed type |

| 16 (Oxytocin) | 45 | Mixed type |

| Galantamine | 5.2 | Uncompetitive |

| Rivastigmine | 0.6 | Uncompetitive |

| Compounds | OXT | Cmpd.7 | Improvement in Cmpd.7 than OXT | |

| Physicochemical properties | Mol. Wt. (kg/mol) | 1006.44 | 1000.46 | … |

| Log p o/w (iLog p) | 1.72 | 2.61 | 1.5-fold higher | |

| Drug-likeness | Caco-2 permeability log(cm/s) | -5.86 | -5.72 | 0.98-fold higher |

| Human intestinal absorption (%) | 51.93 | 57.84 | 1.1-fold higher | |

| BBB permeability (%) | 16.15 | 16.69 | 0.54% higher | |

| Oral bioavailability (%) | 37.37 | 38.85 | 1.48% higher | |

| Acute toxicity (LD50) -log(mol/kg) |

2.87 | 3.0 | approximate | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).