1. Introduction

With the advancement of rail transit towards higher speeds, greater density, and enhanced intelligence, the complexity of train operation control systems has significantly increased. Against this backdrop, train coordinated operation control technology has emerged as a core research field for improving overall system performance. This technology is generally categorized into two key spatial dimensions: single-train internal coordination [

1] and multi-train system coordination [

2]. The former treats each carriage as an independent subsystem that collaboratively accomplishes operational tasks through coordinated control. The latter focuses on achieving global optimization objectives such as safety, punctuality, and energy efficiency at the train formation level, for instance, through distributed algorithms for speed tracking and cooperative scheduling.

However, ideal coordinated control strategies often encounter challenges in practical engineering due to physical limitations, among which actuator saturation is a prevalent constraint. Saturation nonlinearity can lead to performance degradation or even system instability, prompting the development of numerous robust control methods. To address issues such as input saturation, parameter uncertainties, and resource constraints, researchers have developed approaches including adaptive control [

3], self-triggered model predictive control [

4], and multi-agent reinforcement learning-based resource allocation algorithms [

5]. Furthermore, studies such as [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] introduced mechanisms such as disturbance observation, iterative learning, and event triggering, collectively enhancing the control system’s adaptability under non-ideal conditions. These efforts demonstrate that integrating coordinated control theory with robustness design is an effective approach to addressing practical engineering constraints.

In ensuring system reliability, fault-tolerant control is crucial for maintaining safe operation under component failures. If key components such as actuators malfunction or degrade without effective fault-tolerant mechanisms, operational safety can be directly compromised. Current research in this area has branched into several technical routes. One category focuses on passive fault tolerance, enhancing the controller’s inherent robustness through methods such as sliding mode control [

11,

12,

13], stochastic system modeling [

14], and composite anti-disturbance designs [

15,

16]. Another stream emphasizes active fault tolerance, which maintains performance via fault estimation and system reconfiguration, exemplified by neural network-based adaptive iterative learning fault-tolerant control [

17] and active fault-tolerant schemes for partial actuator failures [

18,

19]. In recent years, model-free adaptive fault-tolerant control [

20,

21] has also shown promise by adopting data-driven approaches that reduce dependence on precise mathematical models and improve applicability in complex failure scenarios.

A synthesis of existing research reveals that train coordinated control, robust anti-saturation design, and high-performance fault-tolerant mechanisms have formed an interconnected technological framework. Nevertheless, faced with increasingly complex operational environments and higher intelligence requirements, the challenge remains to deeply integrate these technologies and develop comprehensive control solutions that combine high precision, strong adaptability, high resource efficiency, and inherent operational resilience. Inspired by the aforementioned research, this paper investigates the problem of precise tracking control for high-speed trains with simultaneous actuator faults, parametric uncertainties, and input saturation. The main contributions are as follows:

1. The development of a distributed adaptive fault-tolerant control scheme for a heterogeneous multi-agent train model, explicitly considering both multiplicative and additive actuator faults.

2. The design of a novel second-order auxiliary system to dynamically compensate for input saturation constraints, ensuring closed-loop stability.

3. Rigorous stability analysis via Lyapunov theory and comprehensive simulations demonstrating superior tracking performance and resilience compared to a centralized control approach.

1.1. Dynamic Model

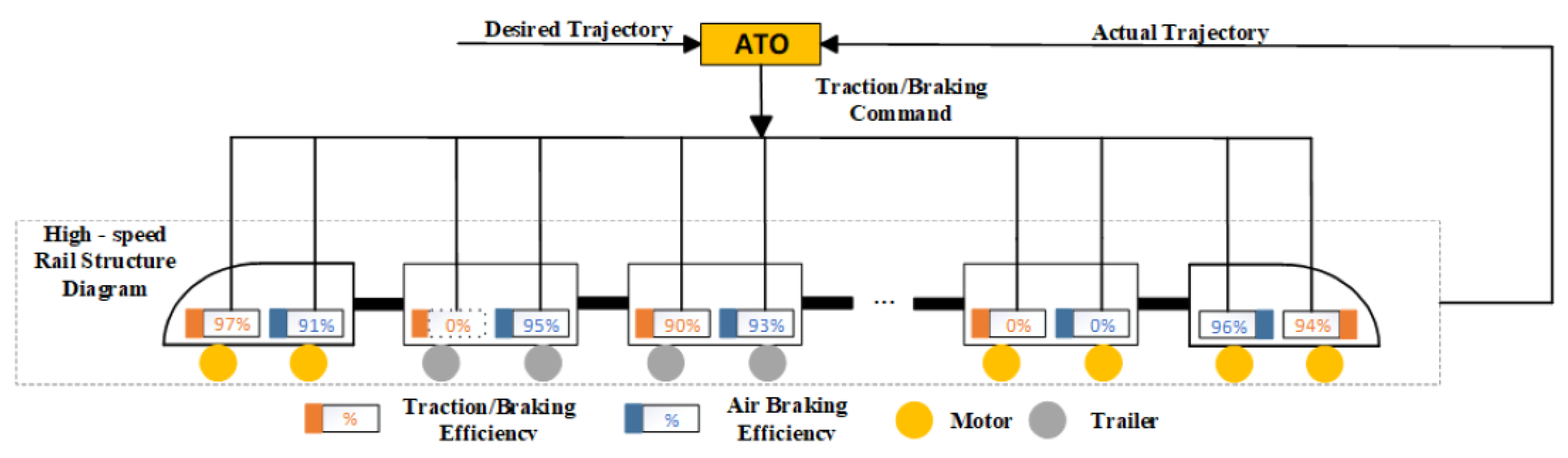

A high-speed train typically comprises both motor cars, equipped with independent power systems, and trailer cars, which provide emergency braking capability only. This hybrid composition is modeled as a heterogeneous multi-agent system. As illustrated in

Figure 1, an eight-carriage train configuration is presented, where motor cars and trailer cars are distinguished by yellow and gray tires, respectively. Based on Newton’s second law, the longitudinal dynamics of the

k-th carriage can be expressed as follows:

where

t denotes time, the subscript

k represents the carriage number,

represents the total weight of the

k - th carriage, and represents the acceleration of the

k - th carriage.

represents the traction/braking force of the

k - th carriage,

represents the basic resistance of the

k - th carriage,

I represents the internal force between adjacent carriages, and

represents the unknown interference of the external environment on the

k - th carriage.

As shown in

Figure 1, the traction/braking efficiencies of different carriages of high - speed trains vary, and the actuators of motor cars and trailer cars also differ. The forward direction of the train is regarded as the reference direction. The expressions of

and

are as follows. Among them,

, where

and

are the internal forces of the train acting on the

k - th carriage from adjacent vehicles respectively.

Among them,

n represents the total number of carriages in the train, and

l represents the length of a carriage. The elastic coefficient and damping coefficient of the coupler are denoted as

and

respectively.

represents the total weight of the entire train, which can be calculated by summing the weights of each carriage, where

represents the weight of the

k - th carriage. In addition,

and

are mechanical resistance coefficients, and

represents the air resistance coefficient. Usually, the air resistance only affects the first carriage of the train. It should be noted that the uncertain parameters handled by the controller are

and

.

1.2. Actuator Failure Model

Actuator faults, inevitably arising from long-term cyclic operation in high-speed train traction systems, can lead to issues such as overheating and severe vibration. These anomalies may result in partial or complete failure of traction/braking actuators, manifesting as over-voltage in the traction transformer, over-current in the traction converter, or over-heating of the asynchronous motor. When a fault occurs in the actuator during the operation of a high - speed train, the actual force

applied to the train can be equivalently expressed as:

Among them,

represents the traction/braking force expected to be input by the controller,

is the health factor of the actuator, that is, the multiplicative fault coefficient of the

k - th carriage, and

is the additive fault coefficient, where

is an unknown upper bound.

The maximum allowable operating speed of a high - speed train directly determines the maximum traction capacity of the traction system and its redundant design. However, in the input saturation state, the high - speed train will not be able to maintain normal operating performance. Therefore, based on the input limitation conditions of the traction motor, the traction/braking force of the high - speed train needs to meet the following constraint requirements:

Among them,

represents the maximum traction/braking force that the traction motor can provide, and

represents the minimum traction/braking force that the traction motor can provide. Since the traction/braking force provided by the motor is converted from the input power,

and

are functions related to the train speed. The established traction force model (

6) captures the uncertainties inherent in the train’s actuators. Define the input error as:

1.3. Multi-Body Dynamics Model of the Train

Based on formulas (

1) - (

4), the multi - agent system model of the high - speed train is constructed as follows:

Among them:

Among them, the known parameter vector of the train is denoted as

,

,

and

. There are slowly-varying unknown parameters in the train dynamics model.

,

,

,

,

,

represent the matrix or vector composed of unknown slow-time-varying parameters.

,

represents the sum of the unknown external disturbances of the carriages and the unknown disturbances of the internal actuators, and this part of the parameters is fast-time-varying.

U is the control input calculated by the controller, and

is the diagonal matrix operator.

Assumption A1. The desired states of each carriage of the train are unknown, the speed trajectory is continuously differentiable, and the desired acceleration of the carriages is known.

The calculation process of the desired operation trajectory of the high - speed train’s Automatic Train Operation (ATO) system is to obtain the speed and position by integrating the desired acceleration. In this way, the problem of calculation expansion caused by multiple differentials of will not occur.

Assumption A2. The external disturbance vector is bounded, i.e., is a known vector.

Assumption A3. , , , , , is an unknown slow-time-varying parameter. For example, its derivative is 0, i.e., .

, , , , , are related to the carriage structure, coupler coefficient, characteristics and materials of the traction/braking system, and its rate of change is extremely small.

2. Controller Design and Analysis

2.1. Design of Distributed Fault-Tolerant Controller for Trains

An auxiliary system is constructed to address stability issues arising from actuator saturation. To design a controller in the presence of actuator faults and saturation, a second - order secondary system is introduced as follows:

Among them,

,

,

,

p,

q are design parameters.

and

are the states of the auxiliary system.

is the input signal of the system.

Based on the above analysis, an n×n matrix is constructed with an n - dimensional vector as the diagonal elements of the matrix. The following tracking error is defined:

Among them,

and

are the column vectors of the actual position and speed of the train, and

and

are the column vectors of the desired position and desired speed. It is worth noting that if

,

, then

and

are still zero. By constructing the auxiliary system, the influence of input saturation on the stability of the closed-loop control system can be solved. From the perspective of train control, the speed change of the auxiliary system can be adjusted through the parameters

,

,

,

p,

q. By introducing the auxiliary system states

and

into the tracking errors

and

, the problem of the rapid increase of the tracking error caused by actuator faults can be corrected.

A sliding surface is introduced as follows:

where

. Aiming at the faults, saturation and uncertainties of the actuators of high-speed trains, the adaptive distributed fault-tolerant controller is designed as follows:

The adaptive rate of the design parameters is as follows:

Proof. To prove the convergence of the proposed controller, the Lyapunov function is constructed as follows:

Among them,

represents the estimation error.

have the same definition.

represents the operator of the matrix trace, which is the sum of the diagonal elements of the matrix. Taking the derivative of (

19), we have:

The derivative of formula (

11) yields:

Substituting Formula (

9)- Formula (

12) into Formula (

21) yields the result:

Substituting the controller (

12) into (

22) yields:

Then, substituting (

23) into (

20) leads to:

where

.

By subtracting adaptive law (

13) from (

18), we can obtain:

Among them, all the matrices involved in (

25) are diagonal matrices. The operations of diagonal matrices satisfy the commutative law, that is:

Therefore, under the control of the controller

u and the adaptive law, the system will eventually reach the sliding mode surface, i.e.,

, and then

and

will approach zero. When the actuators of the system have sufficient power,

and the auxiliary system converges. will approach zero within a bounded time. After that, the tracking errors of the train’s speed and position will approach zero, and finally, each carriage will achieve state-consistent tracking of the desired operation trajectory. □

3. Simulation Verification

3.1. Simulation Environment Description

In this section, a numerical simulation experiment is designed to verify the control effect of the designed Distributed Adaptive Fault - Tolerant Control (DAFTC) method. The simulation adopts a high - speed train formation of four motor cars and four trailer cars, that is, each train consists of four motor cars and four trailer cars. Among them, the motor cars can provide traction force, electric braking force, and air braking force, while the trailer cars can only provide air braking force. At the same time, a centralized adaptive fault - tolerant control (CAFTC) method is designed. This control method also takes into account actuator uncertainties and input saturation. Different from distributed control, centralized control calculates the total traction/braking force required for the whole train’s operation and then evenly distributes the total traction/braking force to each motor - car carriage. In distributed control, the traction/braking forces among different motor cars are different, and its expression is as follows:

Among them,

represents the first element of the column vector

. Similarly,

,

,

,

have the same definition.

The carriages are assumed to be strongly coupled. Therefore, due to the coupler effects, the relative displacements and speeds between carriages remain minimal under normal operation. Therefore, the operation trajectories of each carriage are basically the same. Based on the above analysis, only the operation trajectory of the first carriage is shown in the simulation operation trajectory diagram to keep the graph concise.

The parameters of the high - speed train and the ATO controller are set as shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Result Analysis

The situation where the actuator efficiency of each carriage during train operation decreases and is inconsistent is set, and a comparative simulation is carried out between the DAFTC proposed in this paper and CAFTC.

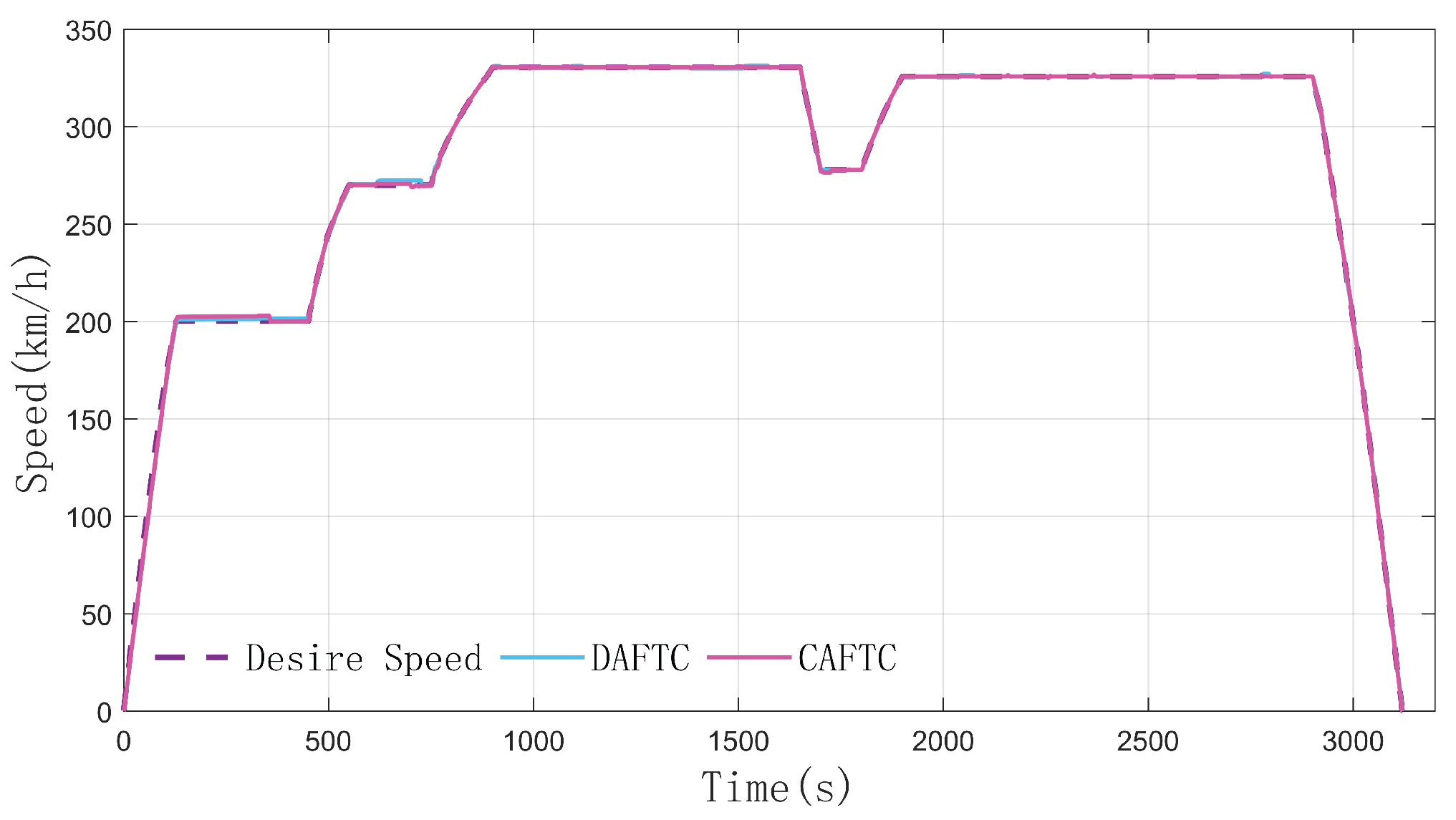

Figure 2 shows the speed - tracking trajectory diagrams of DAFTC and CAFTC.

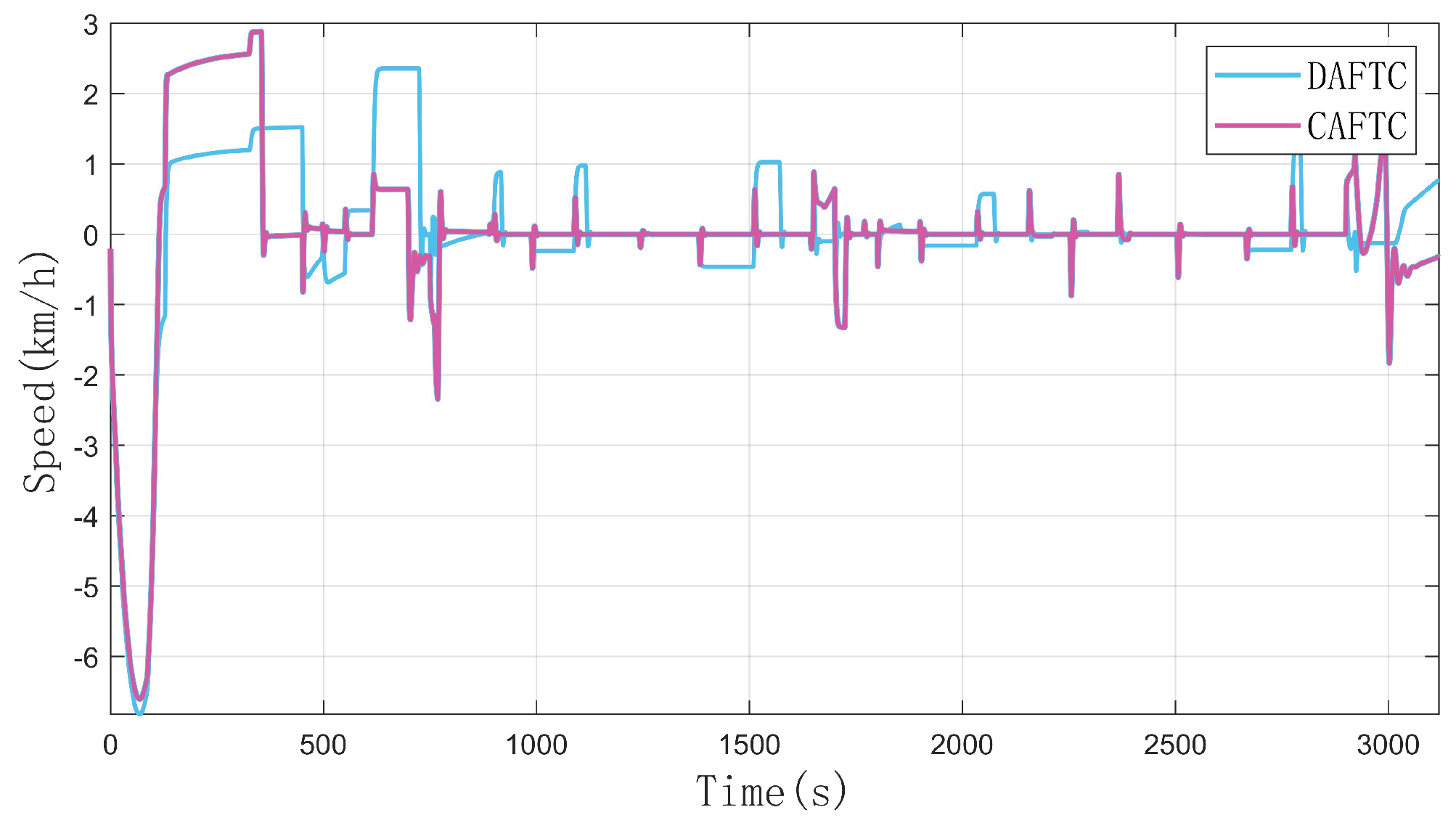

Figure 3 shows the corresponding speed - tracking errors of the two controllers. A transient speed-tracking error is observed during the initial traction phase. This is because actuator faults, saturation limitations, and the need for a certain time to adjust the parameters through adaptive control lead to an increase in the train’s error in a short time, but it can converge quickly. When the actuator efficiency is low and inconsistent, the train’s speed - tracking error increases significantly, but it will also converge to a certain range subsequently.

By comparing the speed - tracking errors of the two controllers, it can be seen that DAFTC has higher control accuracy and a faster recovery speed of the train’s tracking state when short - term execution faults occur. At the same time, from the speed - tracking error curve, it can be seen that after the speed - tracking error converges, it is always controlled within km/h. When the train’s operating conditions change, there will be a small - degree fluctuation, but it always fluctuates within a small range and can converge quickly, which has a very small impact on the riding comfort.

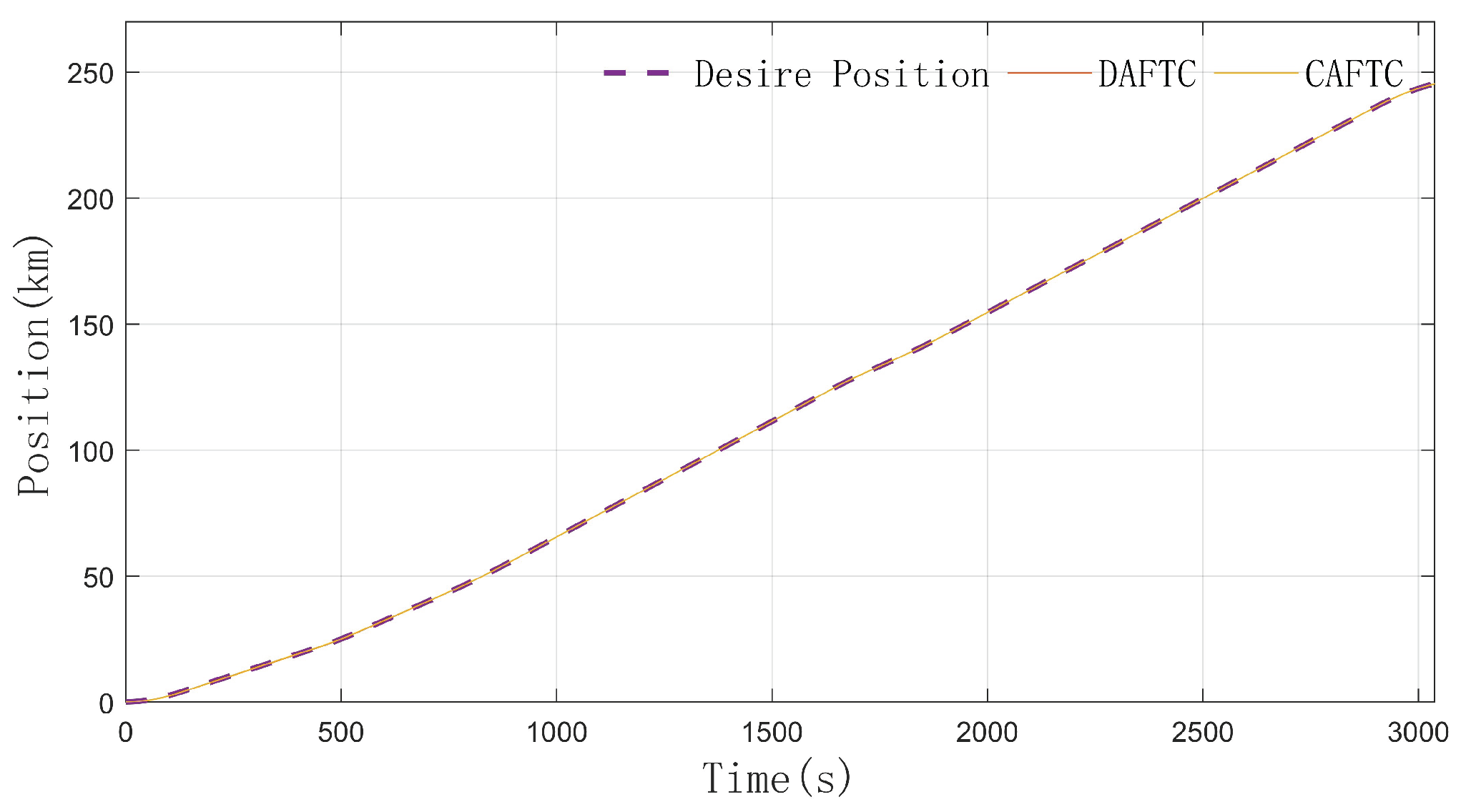

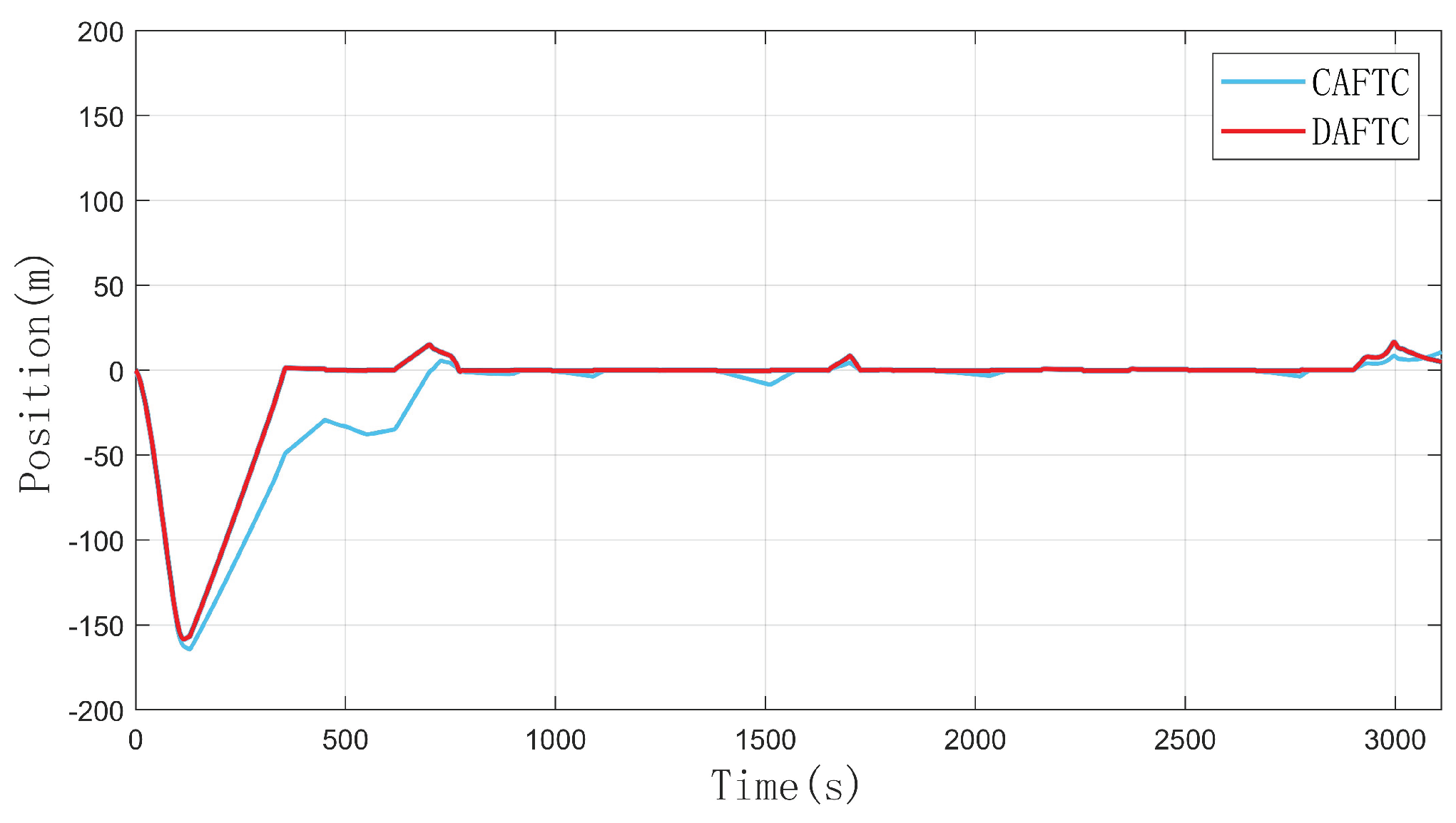

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the position - tracking trajectories and position - tracking errors of DAFTC and CAFTC respectively. By comparing the position errors of the two controllers, it can be seen that DAFTC, which adopts the distributed control strategy, can make the error converge in a relatively short time. In contrast, for CAFTC, which adopts the centralized control strategy, the position error fails to converge. The reason is that in the centralized control mode, when there are differences in the execution of each carriage, a carriage with low efficiency will always be affected by the forces from adjacent carriages to maintain the speed consistency of the whole train. Moreover, DAFTC can adaptively adjust the control parameters during the differential control of carriages. Therefore, DAFTC has higher position - tracking accuracy and stronger anti - interference ability on the line.

Table 2 present the analysis results of the control performance indicators of the two controllers.

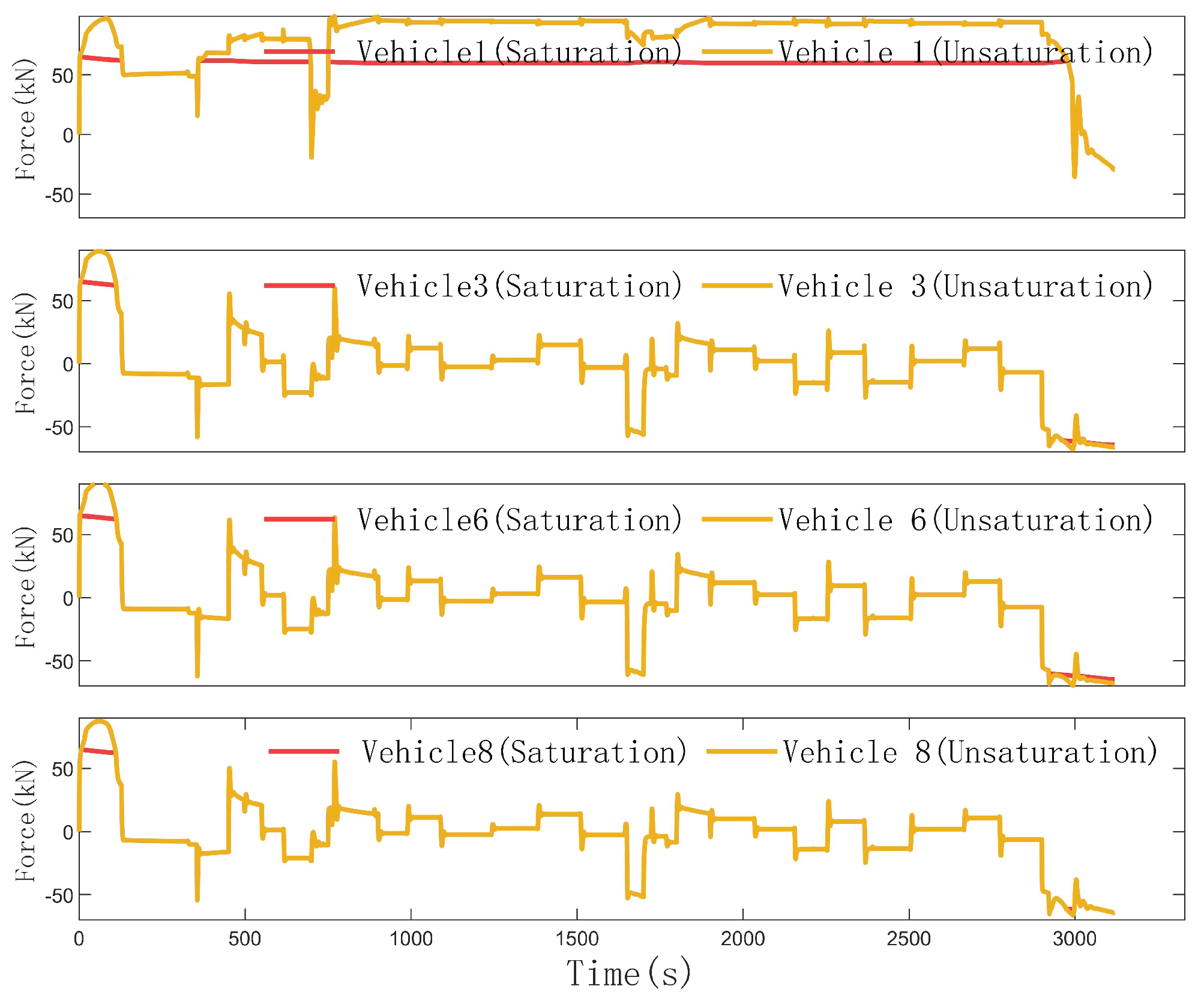

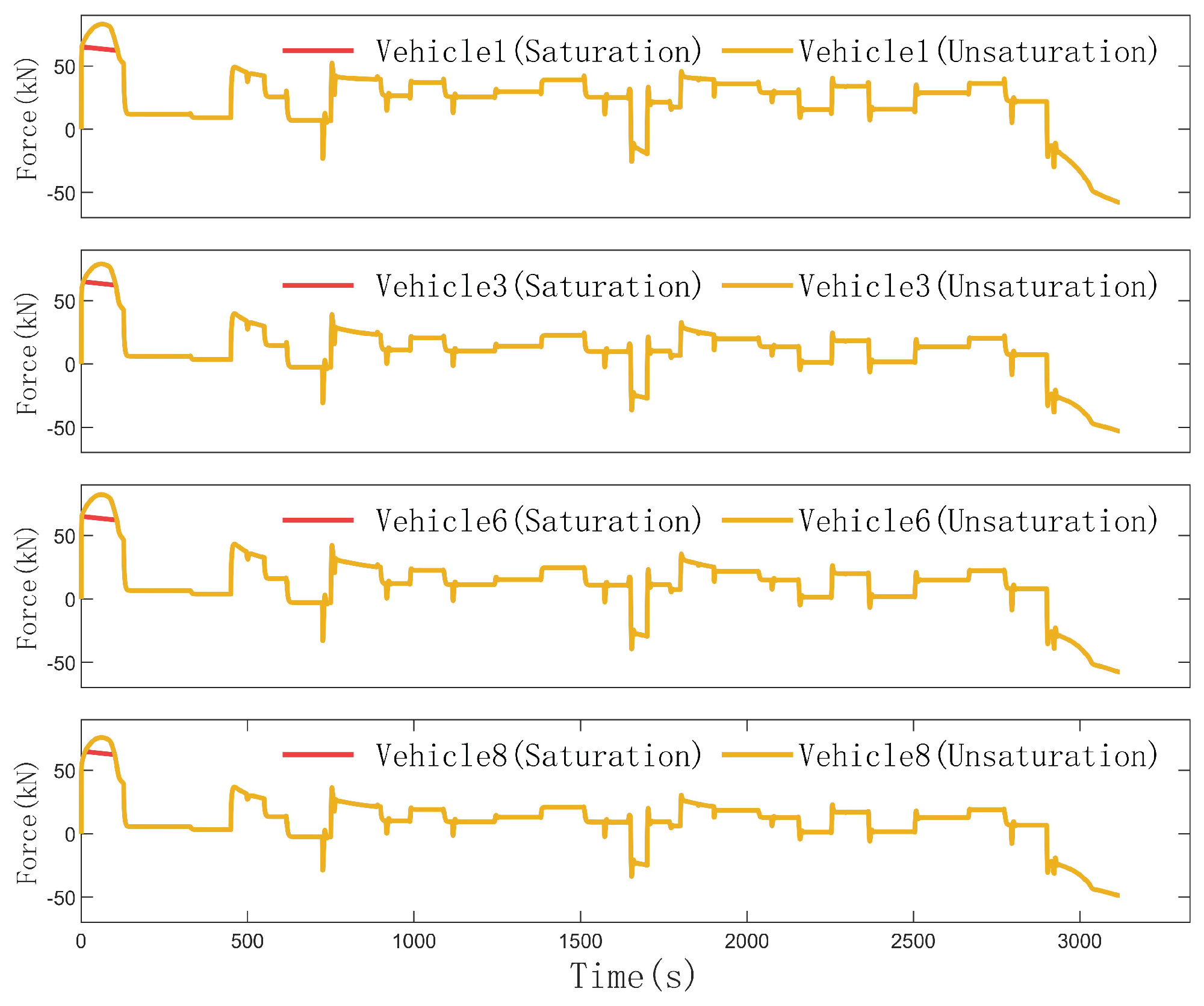

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the carriage control inputs of DAFTC and CAFTC respectively. It can be seen that there are differences in the traction/braking forces among carriages in DAFTC. Due to the low efficiency of the actuators, the traction/braking forces calculated by the train controller cannot be achieved under the condition of input saturation. In summary, DAFTC can still achieve precise dual - closed - loop tracking of speed and position when the train actuators malfunction and the actuator efficiencies among different units are inconsistent.

4. Discussion

The simulation results demonstrate that the proposed DAFTC effectively addresses the challenges of actuator faults, input saturation, and parameter uncertainties in high-speed train systems. Compared to the CAFTC, DAFTC exhibits superior performance in both speed and position tracking, with faster convergence and smaller steady-state errors. This improvement can be attributed to the distributed control structure, which allows for individualized force allocation among carriages and adaptive parameter tuning in real time.

These findings align with and extend previous studies on distributed train control and fault-tolerant systems. The integration of a second-order auxiliary system successfully mitigates the adverse effects of input saturation, while the adaptive laws ensure robustness against uncertain dynamics and actuator degradation. The results also highlight the importance of considering heterogeneity among carriages—a factor often oversimplified in centralized designs. Future work could explore the integration of communication delays between carriages, more complex fault scenarios, and the application of data-driven methods to further enhance the adaptability and scalability of the proposed control framework.

5. Conclusions

This paper has proposed a distributed adaptive fault-tolerant control (DAFTC) scheme for high-speed trains based on a carriage-level multi-body dynamics model. The scheme effectively handles system nonlinearities, parametric uncertainties, and external disturbances. Rigorous theoretical analysis using Lyapunov methods guarantees the stability of the closed-loop system under actuator faults. Numerical simulations demonstrate that the proposed controller achieves consistent cooperative tracking and outperforms a centralized control approach in accuracy and resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.H.W. and W.X.Y.; methodology, W.H.W., W.X.Y. and G.Y.X.; software, G.Y.X. and S.P.F.; validation, W.H.W., W.X.Y., G.Y.X., S.P.F., L.G.L and D.W.J.; formal analysis,W.X.Y. and G.Y.X.; investigation, W.X.Y., G.Y.X. and S.P.F.; resources, W.H.W., L.G.L and D.W.J.; data curation, W.X.Y., G.Y.X. and S.P.F.; writing—original draft preparation, W.H.W.; writing—review and editing, G.Y.X. and S.P.F.; visualization, W.X.Y.; supervision, S.P.F.; project administration,W.H.W.; funding acquisition, W.H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Research and Development Program of China grant number 2022YFB4301105.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao Y, Wang T. Distributed control for high-speed trains movements[C]. 2017 29th Chinese Control And Decision Conference (CCDC), 2017: 7591-7596.

- Bai W, Lin Z, Dong H, et al. Distributed cooperative cruise control of multiple high-speed trains under a statedependent information transmission topology[J]. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2019, 20(7): 2750-2763. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Yang L, Gao Z. Adaptive coordinated control of multiple high-speed trains with input saturation[J]. Nonlinear Dynamics, 2015, 83(4): 2157-2169.

- Xun J, Yin J, Liu R, et al. Cooperative control of high-speed trains for headway regulation: A self-triggered model predictive control based approach[J]. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2019, 102: 106-120. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Zhang Y, Nie Y, et al. Intelligent resource allocation for train-to-train communication: a multi-agent deep reinforcement learning approach[J]. IEEE Access, 2020, 8, 8032-8040. [CrossRef]

- Yao X, Wu L and Guo L. Disturbance-observer-based fault tolerant control of high-speed trains: A Markovian jump system model approach[J]. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man,and Cybernetics: Systems, 2018, 50(4): 1476-1485. [CrossRef]

- Yao X, Zhao B, Li X, et al. Distributed formation control based on disturbance observers for high-speed trains with communication delays[J]. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2024, 25(5): 3457-3466. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Huang D, Huang T, et al. Tracking control via iterative learning for high-speed trains with distributed input constraints[J]. IEEE Access, 2019, 7: 84591-84601. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Le J, Wang Z, et al. Event-triggered consensus control for high-speed train with time-varying actuator fault[J]. IEEE Access, 2020, 8: 50553-50564. [CrossRef]

- Kou L, Fan W, Song S. Multi-agent-based modelling and simulation of high-speed train[J]. Computers & Electrical Engineering, 2020, 86: 106744. [CrossRef]

- Dong H, Lin X, Gao S, et al. Neural networks-based sliding mode fault-tolerant control for high-speed trains with bounded parameters and actuator faults[J]. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 2019, 69(2): 1353-1362. [CrossRef]

- Najafi Amin, Mobayen Saleh, Rouhani Seyed Hossein, et al.Robust adaptive fault-tolerant control for MAGLEV train systems: a nonsingular finite-time approach[J]. IEEE Transactions on transportation electrification, 2025, 11(1): 3680-3690. [CrossRef]

- Zhang T, Kong X. Adaptive fault-tolerant sliding mode control for high-speed trains with actuator faults under strong winds[J]. IEEE Access, 2020, 8: 143902-143919. [CrossRef]

- Yao X, Li S, Li X. Composite adaptive anti-disturbance fault tolerant control of high-speed trains with multiple disturbances[J]. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2022, 23(11): 21799-21809. [CrossRef]

- Guo Y, Wang Q, Sun P, et al. Distributed adaptive fault-tolerant control for high-speed trains using multi-agent system model[J]. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 2024, 73(3): 3277-3286. [CrossRef]

- Lin X, Bai W, Wang Q, et al. Virtual coupling-based H ∞ active fault-tolerant cooperative control for multiple high-speed trains with unknown parameters and actuator faults[J]. IEEE Journal on Emerging and Selected Topics in Circuits and Systems, 2023, 13(3): 780-788. [CrossRef]

- Liu G, Hou Z. Cooperative adaptive iterative learning fault-tolerant control scheme for multiple subway trains[J]. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, 2020, 52(2): 1098-1111. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Chen Z. Fault estimation and tolerant control of a class of nonlinear systems and its application in high-speed trains[J]. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology, 2023, 31(6): 2903-2911. [CrossRef]

- Guo X G and Ahn C K. Adaptive fault-tolerant pseudo-PID sliding-mode control for highspeed train with integral quadratic constraints and actuator saturation[J]. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2020, 22(12): 7421-7431. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Jin S, Hou Z. Cooperative MFAILC for multiple subway trains with actuator faults and actuator saturation[J]. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 2022, 71(8): 8164-8174. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Hou Z. Model-free adaptive fault-tolerant control for subway trains with speed and traction/braking force constraints[J]. IET Control Theory & Applications, 2020, 14(12): 1557-1566. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).