Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

12 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Scoping Review

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Outcomes

2.5. Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.1.1. Age

3.1.2. Gender

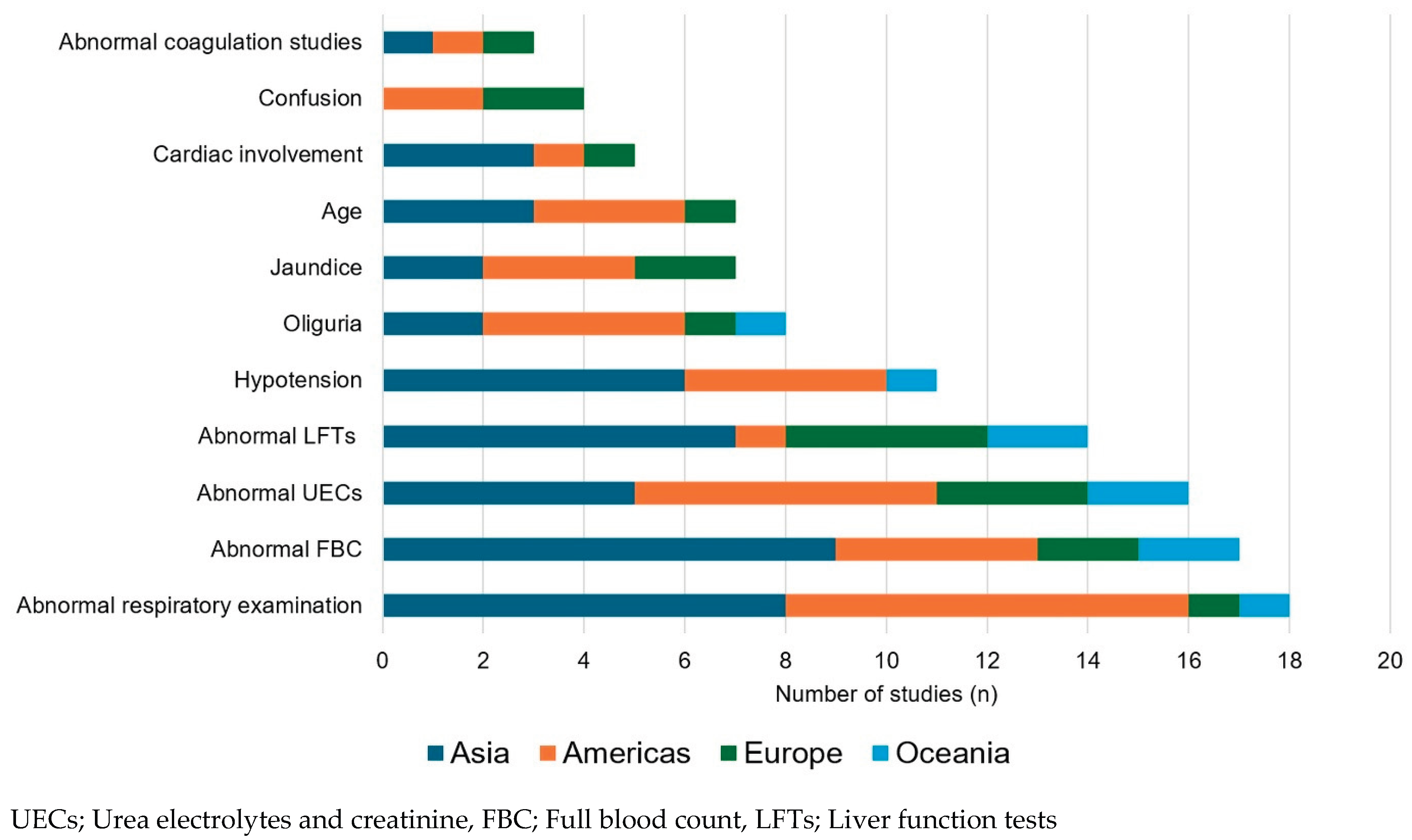

3.2. Clinical Findings

3.2.1. Comorbidities and Lifestyle Factors

3.2.2. Symptoms

3.2.3. Vital Signs

3.2.4. Bedside Examination Findings

3.3. Laboratory Findings

3.3.1. Haematology

3.3.2. Biochemistry

3.4. Other Investigations

3.4.1. Chest Radiological Findings

3.4.2. Electrocardiogram Changes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aPTT | activated partial thromboplastin time |

| AKI | Acute Kidney Injury |

| ALT | Alanine transaminase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| CKD | Chronic kidney Disease |

| FBC | Full blood count, |

| Hb | Haemoglobin |

| ICU | Intensive Care unit |

| IU | International units |

| LFTs | Liver function tests |

| NEWS2 | National Early Warning Score 2 |

| PCV | Packed Cell Volume |

| PT | Prothrombin time |

| RRT | renal replacement therapy |

| SIRS | Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome |

| SGOT | Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase |

| SOFA | Sequential organ failure assessment |

| UECs | Urea electrolytes and creatinine |

| ULN | upper limit of normal |

| UVA | Universal Vital Assessment |

| WBC | White blood cell |

References

- Rajapakse S, Fernando N, Dreyfus A, Smith C, Rodrigo C. Leptospirosis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2025;11(1):32.

- Costa F, Hagan JE, Calcagno J, Kane M, Torgerson P, Martinez-Silveira MS, et al. Global Morbidity and Mortality of Leptospirosis: A Systematic Review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(9):e0003898.

- Chawla V, Trivedi TH, Yeolekar ME. Epidemic of leptospirosis: an ICU experience. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:619-22.

- Stratton H, Rosengren P, Kinneally T, Prideaux L, Smith S, Hanson J. Presentation and Clinical Course of Leptospirosis in a Referral Hospital in Far North Queensland, Tropical Australia. Pathogens. 2025;14(7):643.

- Katz AR, Ansdell VE, Effler PV, Middleton CR, Sasaki DM. Assessment of the clinical presentation and treatment of 353 cases of laboratory-confirmed leptospirosis in Hawaii, 1974-1998. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(11):1834-41.

- Berman SJ, Tsai CC, Holmes K, Fresh JW, Watten RH. Sporadic anicteric leptospirosis in South Vietnam. A study in 150 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79(2):167-73.

- Ko AI, Galvão Reis M, Ribeiro Dourado CM, Johnson WD, Jr., Riley LW. Urban epidemic of severe leptospirosis in Brazil. Salvador Leptospirosis Study Group. Lancet. 1999;354(9181):820-5.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467-73.

- Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analysis. 2011.

- Patra J, Bhatia M, Suraweera W, Morris SK, Patra C, Gupta PC, et al. Exposure to second-hand smoke and the risk of tuberculosis in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 observational studies. PLoS Med. 2015;12(6):e1001835; discussion e.

- Suwannarong K, Singhasivanon P, Chapman RS. Risk factors for severe leptospirosis of Khon Kaen Province: A case-control study. Journal of Health Research. 2014;28(1):59 EP - 64.

- Al Hariri YK, Sulaiman SAS, Khan AH, Adnan AS, Al-Ebrahem SQ. Determinants of prolonged hospitalization and mortality among leptospirosis patients attending tertiary care hospitals in northeastern state in peninsular Malaysia: A cross sectional retrospective analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:887292.

- Pongpan S, Thanatrakolsri P, Vittaporn S, Khamnuan P, Daraswang P. Prognostic Factors for Leptospirosis Infection Severity. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2023;8(2).

- Sandhu RS, Ismail HB, Ja'afar MHB, Rampal S. The Predictive Factors for Severe Leptospirosis Cases in Kedah. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2020;5(2).

- Rajapakse S, Weeratunga P, Niloofa MJ, Fernando N, Rodrigo C, Maduranga S, et al. Clinical and laboratory associations of severity in a Sri Lankan cohort of patients with serologically confirmed leptospirosis: a prospective study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2015;109(11):710-6.

- Lee N, Kitashoji E, Koizumi N, Lacuesta TLV, Ribo MR, Dimaano EM, et al. Building prognostic models for adverse outcomes in a prospective cohort of hospitalised patients with acute leptospirosis infection in the Philippines. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2017;111(12):531EP - 9.

- Panaphut T, Domrongkitchaiporn S, Thinkamrop B. Prognostic factors of death in leptospirosis: a prospective cohort study in Khon Kaen, Thailand. Int J Infect Dis. 2002;6(1):52-9.

- Goswami RP, Goswami RP, Basu A, Tripathi SK, Chakrabarti S, Chattopadhyay I. Predictors of mortality in leptospirosis: An observational study from two hospitals in Kolkata, eastern India. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2014;108(12):791-6.

- Li D, Liang H, Yi R, Xiao Q, Zhu Y, Chang Q, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of patient with leptospirosis: A multicenter retrospective analysis in south of China. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2022;12:1014530.

- Fonseka CL, Dahanayake NJ, Mihiran DJD, Wijesinghe KM, Liyanage LN, Wickramasuriya HS, et al. Pulmonary haemorrhage as a frequent cause of death among patients with severe complicated Leptospirosis in Southern Sri Lanka. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17(10):e0011352.

- Philip N, Lung Than LT, Shah AM, Yuhana MY, Sekawi Z, Neela VK. Predictors of severe leptospirosis: a multicentre observational study from Central Malaysia. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2021;21(1):1-6.

- Nisansala GGT, Weerasekera M, Ranasinghe N, Gamage C, Marasinghe C, Fernando N, et al. Predictors of severe leptospirosis on admission: a Sri Lankan study. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2023;134:S18-S9.

- Wang HK, Lee MH, Chen YC, Hsueh PR, Chang SC. Factors associated with severity and mortality in patients with confirmed leptospirosis at a regional hospital in northern Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53(2):307-14.

- Budiono E, Riyanto BS, Hisyam B, Hartopo AB. Pulmonary involvement predicts mortality in severe leptospirosis patients. Acta medica Indonesiana. 2009;41(1):11-4.

- Ajjimarungsi A, Bhurayanontachai R, Chusri S. Clinical characteristics, outcomes, and predictors of leptospirosis in patients admitted to the medical intensive care unit: A retrospective analysis. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(12):2055-61.

- Silva AFD, Figueiredo K, Falcao IWS, Costa FAR, da Rocha Seruffo MC, de Moraes CCG. Study of machine learning techniques for outcome assessment of leptospirosis patients. Scientific Reports. 2024;14(1):13929.

- Daher EF, Soares DS, Galdino GS, Macedo Ê S, Gomes P, Pires Neto RDJ, et al. Leptospirosis in the elderly: the role of age as a predictor of poor outcomes in hospitalized patients. Pathog Glob Health. 2019;113(3):117-23.

- Spichler AS, Vilaça PJ, Athanazio DA, Albuquerque JO, Buzzar M, Castro B, et al. Predictors of lethality in severe leptospirosis in urban Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79(6):911-4.

- Galdino GS, de Sandes-Freitas TV, de Andrade LGM, Adamian CMC, Meneses GC, da Silva Junior GB, et al. Development and validation of a simple machine learning tool to predict mortality in leptospirosis. Scientific Reports. 2023;13(1):4506.

- Daher Ede F, Soares DS, de Menezes Fernandes AT, Girão MM, Sidrim PR, Pereira ED, et al. Risk factors for intensive care unit admission in patients with severe leptospirosis: a comparative study according to patients' severity. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:40.

- Marotto PC, Ko AI, Murta-Nascimento C, Seguro AC, Prado RR, Barbosa MC, et al. Early identification of leptospirosis-associated pulmonary hemorrhage syndrome by use of a validated prediction model. J Infect. 2010;60(3):218-23.

- Herrmann-Storck C, Saint-Louis M, Foucand T, Lamaury I, Deloumeaux J, Baranton G, et al. Severe leptospirosis in hospitalized patients, Guadeloupe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(2):331-4.

- Hochedez P, Theodose R, Olive C, Bourhy P, Hurtrel G, Vignier N, et al. Factors Associated with Severe Leptospirosis, Martinique, 2010-2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(12):2221-4.

- Sharp TM, Rivera García B, Pérez-Padilla J, Galloway RL, Guerra M, Ryff KR, et al. Early Indicators of Fatal Leptospirosis during the 2010 Epidemic in Puerto Rico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(2):e0004482.

- Dupont H, Dupont-Perdrizet D, Perie JL, Zehner-Hansen S, Jarrige B, Daijardin JB. Leptospirosis: prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25(3):720-4.

- Miailhe A-F, Mercier E, Maamar A, Lacherade J-C, Le Thuaut A, Gaultier A, et al. Severe leptospirosis in non-tropical areas: a nationwide, multicentre, retrospective study in French ICUs. Intensive Care Medicine. 2019;45(12):1763-73.

- Delmas B, Jabot J, Chanareille P, Ferdynus C, Allyn J, Allou N, et al. Leptospirosis in ICU: A Retrospective Study of 134 Consecutive Admissions. Critical Care Medicine. 2018;46(1):93-9.

- Petakh P, Isevych V, Griga V, Kamyshnyi A. The risk factors of severe leptospirosis in the Transcarpathian region of Ukraine – search for „red flags”. Archives of the Balkan Medical Union. 2022;57(3):231-7.

- Gancheva G. Age as prognostic factor in leptospirosis. Ann Infect Dis Epidemiol 2016; 1 (2). 2016;1006.

- Esen S, Sunbul M, Leblebicioglu H, Eroglu C, Turan D. Impact of clinical and laboratory findings on prognosis in leptospirosis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2004;134(23-24):347-52.

- Abgueguen P, Delbos V, Blanvillain J, Chennebault JM, Cottin J, Fanello S, et al. Clinical aspects and prognostic factors of leptospirosis in adults. Retrospective study in France. Journal of Infection. 2008;57(3):171-8.

- Smith S, Kennedy BJ, Dermedgoglou A, Poulgrain SS, Paavola MP, Minto TL, et al. A simple score to predict severe leptospirosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(2):e0007205.

- Craig SB, Graham GC, Burns MA, Dohnt MF, Smythe LD, McKay DB. Haematological and clinical-chemistry markers in patients presenting with leptospirosis: a comparison of the findings from uncomplicated cases with those seen in the severe disease. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2009;103(4):333-41.

- Tubiana S, Mikulski M, Becam J, Lacassin F, Lefèvre P, Gourinat AC, et al. Risk factors and predictors of severe leptospirosis in New Caledonia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(1):e1991.

- Mikulski M, Boisier P, Lacassin F, Soupe-Gilbert ME, Mauron C, Bruyere-Ostells L, et al. Severity markers in severe leptospirosis: a cohort study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34(4):687-95.

- Rajapakse S, Weeratunga P, Niloofa MJR, Fernando N, Rodrigo C, Maduranga S, et al. Clinical and laboratory associations of severity in a Sri Lankan cohort of patients with serologically confirmed leptospirosis: A prospective study. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2015;109(11):710EP - 6.

- Suwannarong K, Singhasivanon P, Chapman RS. Risk factors for severe leptospirosis of Khon Kaen Province: A case-control study. Journal of Health Research. 2014;28(1):59 - 64.

- Puca E, Pipero P, Harxhi A, Abazaj E, Gega A, Puca E, et al. The role of gender in the prevalence of human leptospirosis in Albania. J Infect Dev Ctries 2018.

- Lee N, Kitashoji E, Koizumi N, Lacuesta TLV, Ribo MR, Dimaano EM, et al. Building prognostic models for adverse outcomes in a prospective cohort of hospitalised patients with acute leptospirosis infection in the Philippines. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2017;111(12):531-9.

- Petakh P, Kamyshnyi O. Oliguria as a diagnostic marker of severe leptospirosis: a study from the Transcarpathian region of Ukraine. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2024;14:1467915.

- Rajapakse S, Rodrigo C, Haniffa R. Developing a clinically relevant classification to predict mortality in severe leptospirosis. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3(3):213-9.

- Dolhnikoff M, Mauad T, Bethlem EP, Carvalho CR. Leptospiral pneumonias. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2007;13(3):230-5.

- Nicodemo AC, Duarte MI, Alves VA, Takakura CF, Santos RT, Nicodemo EL. Lung lesions in human leptospirosis: microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural features related to thrombocytopenia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56(2):181-7.

- Andrade L, Rodrigues AC, Jr., Sanches TR, Souza RB, Seguro AC. Leptospirosis leads to dysregulation of sodium transporters in the kidney and lung. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292(2):F586-92.

- Casey JD, Semler MW, Rice TW. Fluid Management in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;40(1):57-65.

- Jubran A. Pulse oximetry. Critical Care. 2015;19(1):272.

- Herbert LJ, Wilson IH. Pulse oximetry in low-resource settings. Breathe. 2012;9(2):90-8.

- Daher Ede F, de Abreu KL, da Silva Junior GB. Leptospirosis-associated acute kidney injury. J Bras Nefrol. 2010;32(4):400-7.

- Sethi A, Kumar TP, Vinod KS, Boodman C, Bhat R, Ravindra P, et al. Kidney involvement in leptospirosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infection. 2025;53(3):785-96.

- Andrade L, Cleto S, Seguro AC. Door-to-dialysis time and daily hemodialysis in patients with leptospirosis: impact on mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(4):739-44.

- Smith S, Liu YH, Carter A, Kennedy BJ, Dermedgoglou A, Poulgrain SS, et al. Severe leptospirosis in tropical Australia: Optimising intensive care unit management to reduce mortality. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(12):e0007929.

- Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(11):1181-247.

- Day NPJ. Leptospirosis: Epidemiology, microbiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. UpToDate [Internet]. 2025 22 October 2025. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/leptospirosis-epidemiology-microbiology-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis.

- Trevejo RT, Rigau-Pérez JG, Ashford DA, McClure EM, Jarquín-González C, Amador JJ, et al. Epidemic leptospirosis associated with pulmonary hemorrhage-Nicaragua, 1995. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(5):1457-63.

- Smythe L, Dohnt M, Norris M, Symonds M, Scott J. Review of leptospirosis notifications in Queensland 1985 to 1996. Commun Dis Intell. 1997;21(2):17-20.

- Niwattayakul K, Homvijitkul J, Niwattayakul S, Khow O, Sitprija V. Hypotension, renal failure and pulmonary complications in leptospirosis. Renal Failure. 2002;24(3):297-305.

- Izurieta R, Galwankar S, Clem A. Leptospirosis: The "mysterious" mimic. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2008;1(1):21-33.

- Haake DA, Levett PN. Leptospirosis in humans. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;387:65-97.

- Moore CC, Hazard R, Saulters KJ, Ainsworth J, Adakun SA, Amir A, et al. Derivation and validation of a universal vital assessment (UVA) score: a tool for predicting mortality in adult hospitalised patients in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2(2):e000344.

- National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2: Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2017.

- Mar Minn M, Aung NM, Kyaw Z, Zaw TT, Chann PN, Khine HE, et al. The comparative ability of commonly used disease severity scores to predict death or a requirement for ICU care in patients hospitalised with possible sepsis in Yangon, Myanmar. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;104:543-50.

- Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101(6):1644-55.

- Stewart AGA, Smith S, Binotto E, McBride WJH, Hanson J. The epidemiology and clinical features of rickettsial diseases in North Queensland, Australia: Implications for patient identification and management. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(7):e0007583.

- Price C, Smith S, Stewart J, Hanson J. Acute Q Fever Patients Requiring Intensive Care Unit Support in Tropical Australia, 2015-2023. Emerg Infect Dis. 2025;31(2):332-5.

- Lal S, Luangraj M, Keddie SH, Ashley EA, Baerenbold O, Bassat Q, et al. Predicting mortality in febrile adults: comparative performance of the MEWS, qSOFA, and UVA scores using prospectively collected data among patients in four health-care sites in sub-Saharan Africa and South-Eastern Asia. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;77:102856.

- Ye Lynn KL, Hanson J, Mon NCN, Yin KN, Nyein ML, Thant KZ, et al. The clinical characteristics of patients with sepsis in a tertiary referral hospital in Yangon, Myanmar. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2019;113(2):81-90.

- Felzemburgh RD, Ribeiro GS, Costa F, Reis RB, Hagan JE, Melendez AX, et al. Prospective study of leptospirosis transmission in an urban slum community: role of poor environment in repeated exposures to the Leptospira agent. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(5):e2927.

- Khalil H, Santana R, de Oliveira D, Palma F, Lustosa R, Eyre MT, et al. Poverty, sanitation, and Leptospira transmission pathways in residents from four Brazilian slums. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(3):e0009256.

- Adamu S, Neela V. SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIOECONOMIC FACTORS OF LEPTOSPIROSIS TRANSMISSION. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2023;130:S139.

- Teles AJ, Bohm BC, Silva SCM, Bruhn FRP. Socio-geographical factors and vulnerability to leptospirosis in South Brazil. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1311.

- Navinan MR, Rajapakse S. Cardiac involvement in leptospirosis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106(9):515-20.

- Fox J, Patkar V, Chronakis I, Begent R. From practice guidelines to clinical decision support: closing the loop. J R Soc Med. 2009;102(11):464-73.

- Wickramasinghe M, Chandraratne A, Doluweera D, Weerasekera MM, Perera N. Predictors of severe leptospirosis: a review. Eur J Med Res. 2025;30(1):445.

- Singh C, Roy-Chowdhuri S. Quantitative Real-Time PCR: Recent Advances. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1392:161-76.

- Muñoz-Zanzi C, Dreyfus A, Limothai U, Foley W, Srisawat N, Picardeau M, et al. Leptospirosis—Improving Healthcare Outcomes for a Neglected Tropical Disease. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2025;12(2).

- Cagliero J, Villanueva S, Matsui M. Leptospirosis Pathophysiology: Into the Storm of Cytokines. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:204.

- Samrot AV, Sean TC, Bhavya KS, Sahithya CS, Chan-drasekaran S, Palanisamy R, et al. Leptospiral Infection, Pathogenesis and Its Diagnosis—A Review. Pathogens. 2021;10(2):145.

- Evangelista KV, Coburn J. Leptospira as an emerging pathogen: a review of its biology, pathogenesis and host immune responses. Future Microbiol. 2010;5(9):1413-25.

- Petakh P, Oksenych V, Kamyshnyi O. Corticosteroid Treatment for Leptospirosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2024;13(15).

| Article | Location | Number of patients | Primary or referral hospital | Type of study | Definition of severe disease | Variables associated with severe disease | Odds Ratio |

| Suwannarong et al. 2014 [11] | Thailand | 2188 | Both | Retrospective multicentre | Death OR Renal dysfunction OR Jaundice OR Haemorrhagic manifestations OR Leucocytosis OR Cardiac involvement OR Pulmonary involvement |

Age >36 years | 1.27 |

| Residence in rural area | 0.67 | ||||||

| Late initiation of treatment (>2 days vs. ≤2 days after symptom onset) | 5.36 | ||||||

| Al Hariri et al. 2022 [12] | Malaysia | 525 | Referral | Retrospective multicentre | Death | Age >40 years | Not reported |

| CKD | Not reported | ||||||

| Tachypnoea (RR>28/min) | Not reported | ||||||

| AKI | Not reported | ||||||

| Rhabdomyolysis | Not reported | ||||||

| Multiple organ dysfunction | Not reported | ||||||

| Respiratory failure | Not reported | ||||||

| Pneumonia | Not reported | ||||||

| Sepsis | Not reported | ||||||

| T-wave changes on ECG | Not reported | ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | Not reported | ||||||

| Conducting abnormality | Not reported | ||||||

| Venous acidosis | Not reported | ||||||

| Elevated AST or ALT | Not reported | ||||||

| Hypoalbuminemia | Not reported | ||||||

| Severe thrombocytopenia | Not reported | ||||||

| Prolonged PT | Not reported | ||||||

| Prolonged aPTT | Not reported | ||||||

| Pulmonary infiltrate | Not reported | ||||||

| Pongpan et al. 2023 [13] | Thailand | 480 | Primary | Retrospective multicentre | Death OR Serum creatinine > 3 mg/dL OR Respiratory failure |

Haemoptysis | 25.8 |

| Hypotension (BP < 90/60mmHg) | 17.33 | ||||||

| Jaundice | 3.11 | ||||||

| Thrombocytopaenia < 100,000/µL | 8.37 | ||||||

| Leucocytosis > 14,000/µL | 5.12 | ||||||

| Haematocrit ≤ 30% | 3.49 | ||||||

| Sandhu et al. 2020 [14] | Malaysia | 456 | Both | Retrospective multicentre | Jaundice OR Renal dysfunction OR Haemorrhaging OR Myocarditis OR Arrhythmia OR Pulmonary haemorrhage with respiratory failure OR Meningitis/Meningoencephalitis |

Abnormal respiratory auscultation | 3.07 |

| Hypotension | 2.16 | ||||||

| Hepatomegaly | 7.14 | ||||||

| Leucocytosis | 2.12 | ||||||

| Low haematocrit | 2.33 | ||||||

| Increased ALT | 2.12 | ||||||

| Rajapakse et al. 2015 [15] | Sri Lanka | 232 | Referral | Prospective multicentre | Death OR ICU admission OR Hospital stay > 10 days OR Evidence of major organ dysfunction (liver, kidney, lung or heart) |

Age >40 years | Not reported |

| Highest recorded fever >38.8°C | Not reported | ||||||

| Myalgia | Not reported | ||||||

| PCV <29.8% | 3.750 | ||||||

| PCV >33.8 | Not reported | ||||||

| Hb <10.2 g/dL and >11.2 g/dL | Not reported | ||||||

| ALT >70 IU/L | 2.639 | ||||||

| Hyponatremia <131 mEq/L | 6.413 | ||||||

| WBC >12 350/mm3 and <7900mm3 | Not reported | ||||||

| Thrombocytopaenia <63 500/mm3 | Not reported | ||||||

| Lee et al. 2017 [16] | Philippines | 203 | Referral | Prospective single centre | AKI OR Dialysis OR Pulmonary haemorrhage OR Liver dysfunction (2.5× ULN AST and ALT or presenting with jaundice). |

Male sex | 3.29 |

| Duration of symptoms prior to antibiotic therapy | 1.28 | ||||||

| Death | Neutrophilia | 1.38 | |||||

| Thrombocytopenia | 0.99 | ||||||

| Panaphut et al. 2002 [17] | Thailand | 121 | Referral | Prospective single centre | Death | Hypotension | RR=10.3 |

| Oliguria | RR=8.8 | ||||||

| Hyperkalaemia | RR=5.9 | ||||||

| Pulmonary rales on auscultation | RR=5.2 | ||||||

| Goswami et al. 2014 [18] | India | 101 | Referral | Retrospective multicentre | Death | Duration of symptoms prior to antibiotics | 1.30 |

| AST/ALT ratio | 1.20 | ||||||

| Li et al. 2022 [19] | China | 95 | Referral | Retrospective multicentre | ICU admission | Dyspnoea | 29.05 |

| Neutrophilia | 1.61 | ||||||

| Fonseka et al. 2023 [20] | Sri Lanka | 88 | Referral | Prospective single centre | Death | Pulmonary haemorrhage | 9.3 |

| Hypotension (BP <90/60) | 12.2 | ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 4.7 | ||||||

| Acute haemoglobin reduction | 5.3 | ||||||

| High AST level | 5.3 | ||||||

| Philip et al. 2021 [21] | Malaysia | 83 | Referral | Prospective multicentre | Hospitalisation AND Jaundice OR AKI OR pulmonary involvement |

AKI | 10.4 |

| ALT > 50 IU | 8.1 | ||||||

| Thrombocytopaenia < 150 × 109/L | 7.3 | ||||||

| Nisansala et al. 2023 [22] | Sri Lanka | 79 | Referral | Prospective multicentre | Acute kidney injury OR Pulmonary haemorrhage OR Myocarditis OR Liver failure |

Dyspnoea | 7.1 |

| Icterus | 6.45 | ||||||

| Oliguria | 5.22 | ||||||

| Cardiac arrythmias | 5.92 | ||||||

| WBC >11,000 mm3 | 3.64 | ||||||

| Neutrophil >75% | 13.41 | ||||||

| SGOT >40 U/L | 5.89 | ||||||

| Serum creatinine >120 μmol/L | 29.14 | ||||||

| Blood urea >6.5 mmol/L | 15.00 | ||||||

| Total bilirubin >21 μmol/L | 15.20 | ||||||

| Wang et al. 2020 [23] | Taiwan | 57 | Referral | Retrospective multicentre | RRT OR Mechanical ventilation OR Vasopressors OR Blood transfusion OR Meningitis or meningoencephalitis OR Myocarditis |

Shock | 14.8 |

| Death | Previous corticosteroid use | 20.2 | |||||

| Haemorrhage | 71.2 | ||||||

| Budiono et al. 2009 [24] | Indonesia | 55 | Referral | Retrospective single-centre | Death | Pulmonary involvement | 9.9 |

| Meningismus | |||||||

| Ajjimarungsi et al. 2020 [25] | Thailand | 46 | Referral | Retrospective single-centre | ICU admission | SOFA score >6 | 1.8 |

| Thai lepto score>6 | 1.3 | ||||||

| Mechanical ventilator support | 63.2 | ||||||

| Inotrope or vasopressor requirements | 53.5 |

| Article | Location | Number of patients | Primary or referral hospital | Type of study | Definition of severe disease | Variables associated with severe disease | Odds Ratio |

| Silva et al. 2024 [26] | Brazil | 1,319 | Both | Retrospective multicentre | Death | Delay in medical attention | Not reported |

| Headache | Not reported | ||||||

| Calf pain | Not reported | ||||||

| Vomiting | Not reported | ||||||

| Jaundice | Not reported | ||||||

| Renal insufficiency | Not reported | ||||||

| Respiratory alterations | Not reported | ||||||

| Daher Ede et al. 2019 [27] | Brazil | 507 | Referral | Retrospective multicentre | Death OR RRT |

Age >60 years | Death: 3.52 RRT: 2.049 |

| Spichler et al. 2008 [28] | Brazil | 378 | Both | Retrospective multicentre | Death | Age > 40 years | 2.36 |

| Oliguria | 7.1 | ||||||

| Pulmonary involvement | 9.1 | ||||||

| Thrombocytopenia < 70,000/µL, | 2.6 | ||||||

| Creatinine > 3 mg/dL | 4.16 | ||||||

| Galdino et al. 2023 [29] | Brazil | 295 | Referral | Retrospective multicentre | Death | Age >40 years | Not reported |

| Lethargy | Not reported | ||||||

| Respiratory symptoms | Not reported | ||||||

| Mean Arterial Pressure < 80 mmHg | Not reported | ||||||

| Haematocrit < 30% | Not reported | ||||||

| Daher Ede et al. 2016 [30] | Brazil | 206 | Referral | Retrospective single centre | ICU admission | Tachypnoea | 13 |

| Hypotension | 5.27 | ||||||

| AKI | 14 | ||||||

| Marotto et al. 2010 [31] | Brazil | 203 | Referral | Retrospective single centre | Pulmonary haemorrhage | Respiratory rate | 1.1 |

| Presenting in shock | 20.1 | ||||||

| Glasgow Coma Scale Score <15 | 7.7 | ||||||

| Hyperkalaemia | 2.6 | ||||||

| Serum creatinine | 1.2 | ||||||

| Herrmann-Storck et al. 2010 [32] | Guadeloupe | 168 | Referral | Retrospective single centre | Death OR RRT OR Mechanical ventilation |

Chronic hypertension | 30.9 |

| Chronic alcoholism | 16.8 | ||||||

| Duration of symptoms prior to antibiotics | 4.8 | ||||||

| Abnormal respiratory auscultation | 8.7 | ||||||

| Jaundice | 5.9 | ||||||

| Oliguria | 5.6 | ||||||

| Altered consciousness | 3.8 | ||||||

| AST > 102 IU/L | 4.3 | ||||||

| Amylase > 285 IU/L | 18.5 | ||||||

| Leptospira interrogans serovar Icterohemorrhagiae | 5.3 | ||||||

| Hochedez et al. 2015 [33] | Martinique | 102 | Referral | Retrospective single centre | Death OR Vasopressors OR Dialysis OR Mechanical ventilation OR Blood transfusion |

Hypotension | Not reported |

| Chest auscultation abnormalities | Not reported | ||||||

| Icterus | Not reported | ||||||

| Oligo/anuria | Not reported | ||||||

| Thrombocytopenia | Not reported | ||||||

| PT <68% | Not reported | ||||||

| High levels of leptospiremia | Not reported | ||||||

| L. interrogans serovar Icterohemorrhagiae | Not reported | ||||||

| L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni | Not reported | ||||||

| Sharp et al. 2016 [34] | Puerto Rico | 73 | Referral (controls did not have leptospirosis) | Retrospective multicentre | Death | Decreased serum bicarbonate | Not reported |

| Elevated serum creatinine | Not reported | ||||||

| Leucocytosis | Not reported | ||||||

| Thrombocytopenia | Not reported | ||||||

| Dupont et al. 1997 [35] | French West indies | 68 | Referral | Retrospective single centre | Death | Oliguria | 9 |

| Dyspnoea | 11.7 | ||||||

| Leucocytosis >12,900/mm3 | 2.5 | ||||||

| Repolarization abnormalities on ECG | 5.9 | ||||||

| Alveolar infiltrates on chest x-ray | 7.3 |

| Article | Location | Number of patients | Primary or referral hospital | Type of study | Definition of severe disease |

Variables associated with severe disease |

Odds Ratio |

| Miailhe et al. 2019 [36] | France | 160 | Referral |

Retrospective multicentre | Death |

Increasing age | Not reported |

| Chronic alcohol abuse | Not reported | ||||||

| High SOFA score | Not reported | ||||||

| Need for invasive ventilation or renal replacement therapy within 48 h after ICU admission; | Not reported | ||||||

| Jaundice | Not reported | ||||||

| Confusion | Not reported | ||||||

| Higher blood bilirubin level | Not reported | ||||||

| Leucocytosis | Not reported | ||||||

| Delmas et al. 2018 [37] | Réunion island (France) | 134 | Referral |

Prospective single centre | Death | Mechanical Ventilation | Not reported |

| Vasopressors or inotropic support | Not reported | ||||||

| Neurologic and respiratory impairment | Not reported | ||||||

| Transfusion | Not reported | ||||||

| SOFA score | Not reported | ||||||

| SAPS II | Not reported | ||||||

| Acidosis | Not reported | ||||||

| Lower base excess | Not reported | ||||||

| Lactatemia | Not reported | ||||||

| Hyperkalaemia | Not reported | ||||||

| Total bilirubin at admission | Not reported | ||||||

| Intra-alveolar haemorrhage in the first 7 days in ICU | Not reported | ||||||

| Petakh et al. 2022 [38] | Ukraine | 102 | Referral | Retrospective single centre | Death | Oliguria | 13.5 |

| Elevated serum creatinine | Not reported | ||||||

| Elevated serum urea | Not reported | ||||||

| Direct and total bilirubin | Not reported | ||||||

| Thrombocytopenia | Not reported | ||||||

| Leucocytosis | Not reported | ||||||

| Gancheva et al. 2016 [39] | Bulgaria | 100 | Referral | Retrospective single centre | Severe indication OR jaundice with severe hepatic dysfunction OR skin haemorrhages and visceral bleeding OR myocarditis OR dialysis OR respiratory and CNS involvement |

Age | Not reported |

| Esen et al. 2004 [40] | Türkiye | 72 | Referral | Retrospective single centre | Death | Altered mental status | 8.9 |

| Hepatomegaly | Not reported | ||||||

| Haemorrhage | Not reported | ||||||

| Increased AST + ALT | Not reported | ||||||

| Prolonged PT | Not reported | ||||||

| Hyperkalaemia | 4.2 | ||||||

| Abgueguen et al. 2008 [41] | France | 62 | Referral | Retrospective single centre | ICU admission OR RRT |

Jaundice | 10.1 |

| Cardiac damage (clinical or electrocardiographic) | 31.2 |

| Article | Location | Number of patients | Primary or referral hospital | Type of study | Definition of severe disease | Variables associated with severe disease | Odds Ratio |

| Smith et al. 2019 [42] | Australia | 402 | Both | Retrospective multicentre | ICU admission OR RRT OR Mechanical ventilation OR Vasopressor support OR Pulmonary haemorrhage |

Oliguria | 16.4 |

| Hypotension | 4.3 | ||||||

| Abnormal respiratory auscultation | 11.2 | ||||||

| Craig et al. 2009 [43] | Australia | 239 | Both | Retrospective multicentre | ICU admission | Elevated serum urea | Not reported |

| Elevated serum creatinine | Not reported | ||||||

| Hypoalbuminemia | Not reported | ||||||

| Haematocrit | Not reported | ||||||

| Anaemia | Not reported | ||||||

| Thrombocytopenia | Not reported | ||||||

| Leucocytosis | Not reported | ||||||

| Tubiana et al 2013 [44] | New Caledonia | 176 | Referral | Retrospective multicentre | Death OR RRT OR Mechanical ventilation OR Vasopressor support OR Alveolar haemorrhage OR Blood transfusion |

Current cigarette smoking | 2.94 |

| Delay >2 days between the onset of symptoms and the initiation of antibiotic therapy | 2.78 | ||||||

| Thrombocytopenia ≤50,000/µL | 6.36 | ||||||

| Serum creatinine >200 µmol/L | 5.86 | ||||||

| Serum lactate >2.5 mmol/L | 5.14 | ||||||

| Serum amylase >250 IU/L | 4.66 | ||||||

| Leptospiremia >1000 leptospires/mL | 4.31 | ||||||

| Icterohaemorrhagiae serovar | 2.75 | ||||||

| Mikulski et al. 2014 [45] | New Caledonia | 47 | Referral | Prospective single centre | Death OR Mechanical ventilation OR Dialysis |

LDH ≥390 IU/L | 5.8 |

| Increased total bilirubin | 5.0 | ||||||

| AST/ALT ratio ≥2 | 7.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).