Submitted:

17 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

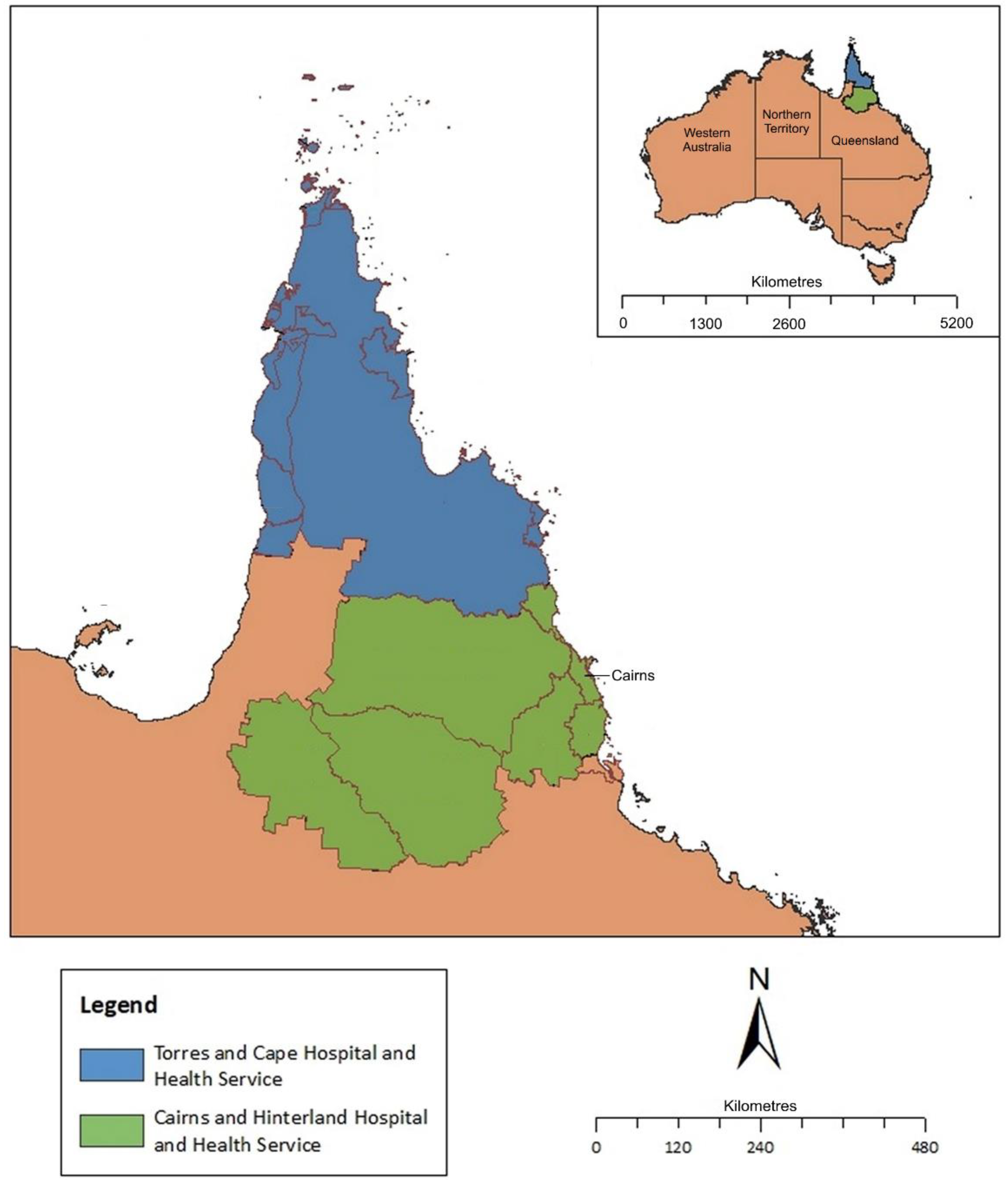

Methods

Statistical Analysis

Ethical Approval

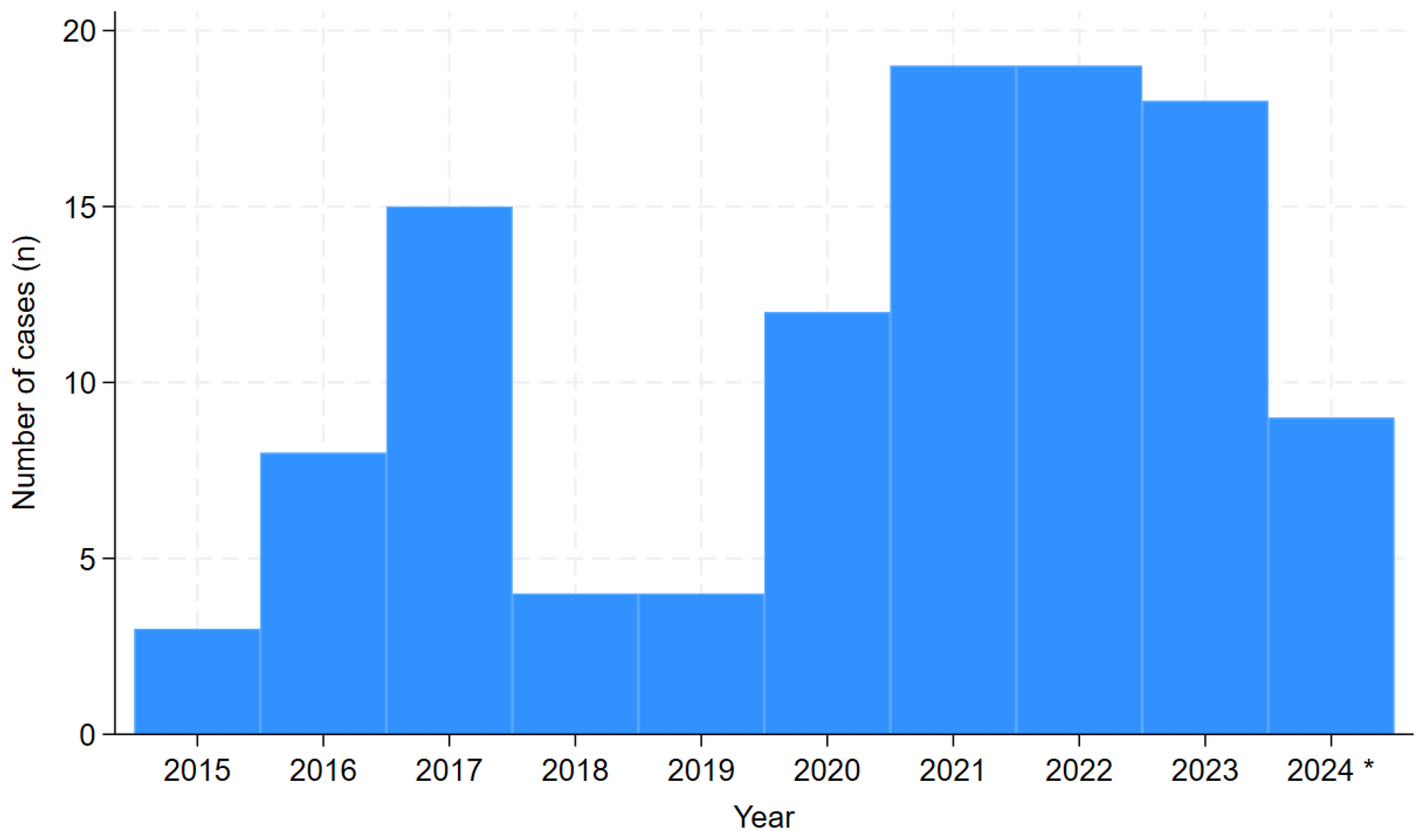

Results

Disease Severity and Clinical Course

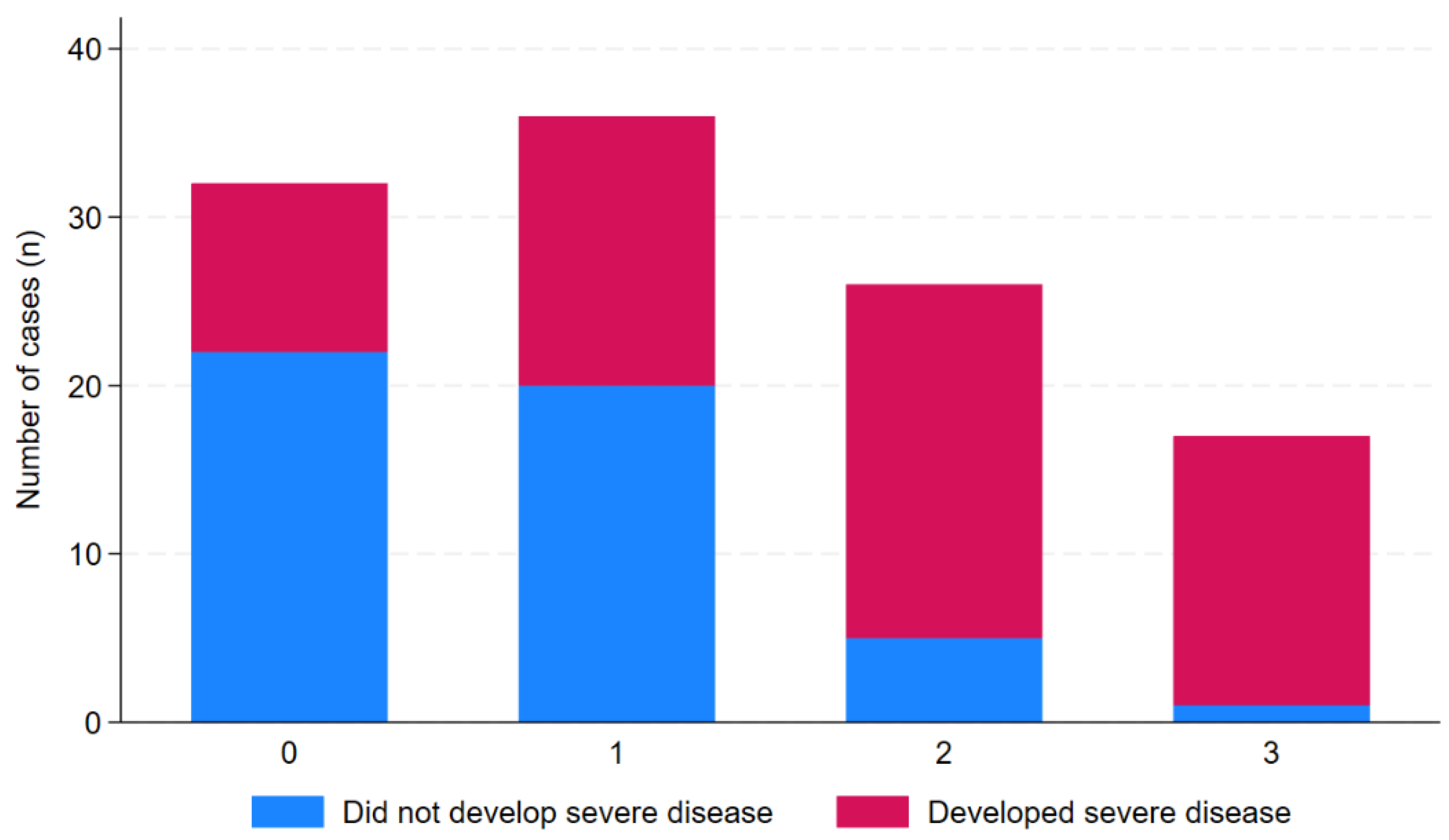

Age, Comorbidity and Correlation with Subsequent Clinical Course

Diagnosis of Leptospirosis

Clinical Signs and Symptoms at Presentation and Correlation with Subsequent Clinical Course

Laboratory Values on Admission and Correlation with Subsequent Clinical Course

Chest Imaging Findings on Presentation and During Admission

Echocardiography

Antibiotic Therapy

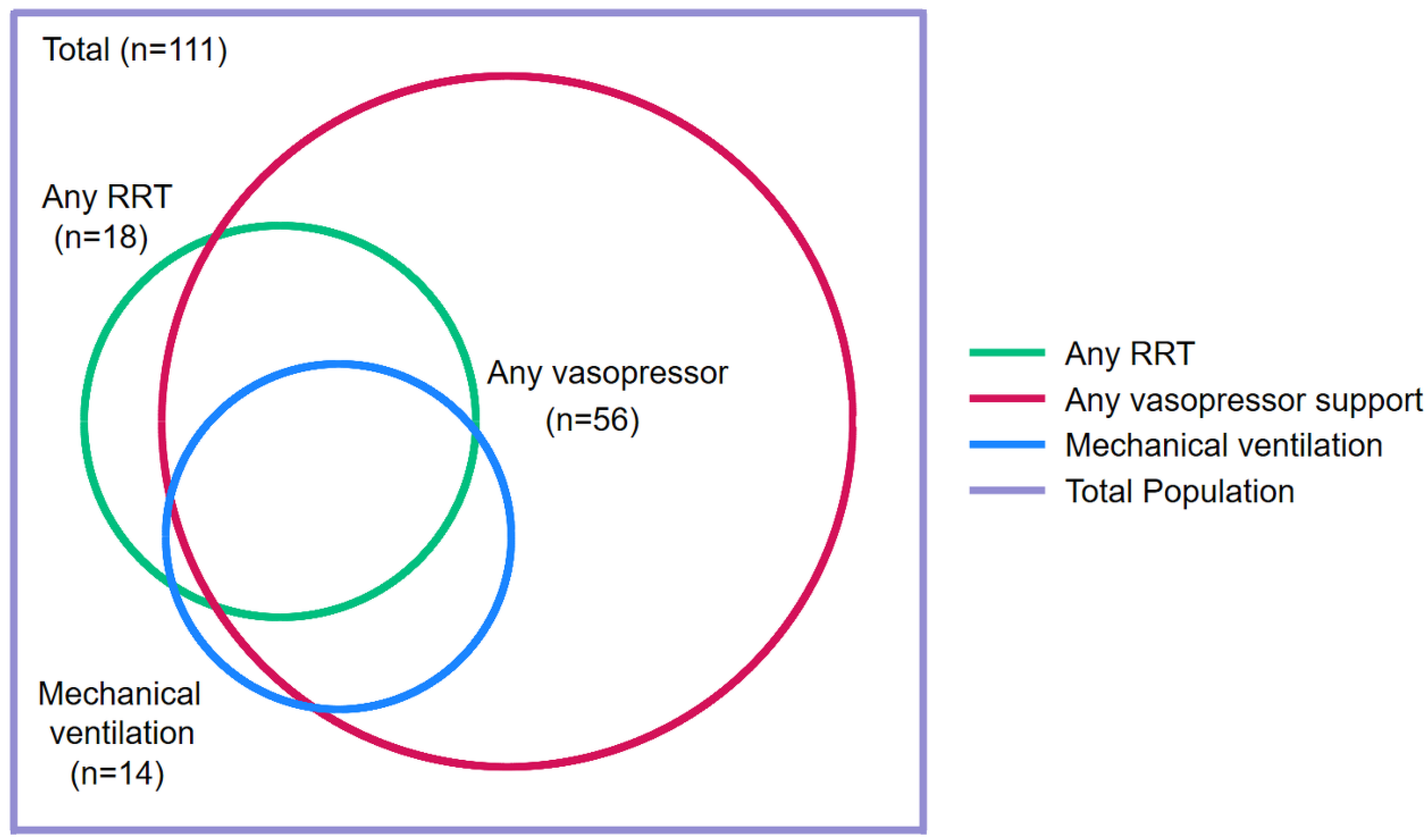

ICU Care

Other Management

Discussion

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rajapakse, S.; Fernando, N.; Dreyfus, A.; Smith, C.; Rodrigo, C. Leptospirosis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2025, 11, 32. [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.; Hagan, J.E.; Calcagno, J.; Kane, M.; Torgerson, P.; Martinez-Silveira, M.S.; Stein, C.; Abela-Ridder, B.; Ko, A.I. Global Morbidity and Mortality of Leptospirosis: A Systematic Review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9, e0003898. [CrossRef]

- Torgerson, P.R.; Hagan, J.E.; Costa, F.; Calcagno, J.; Kane, M.; Martinez-Silveira, M.S.; Goris, M.G.; Stein, C.; Ko, A.I.; Abela-Ridder, B. Global Burden of Leptospirosis: Estimated in Terms of Disability Adjusted Life Years. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9, e0004122. [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.L.; Smythe, L.D.; Craig, S.B.; Weinstein, P. Climate change, flooding, urbanisation and leptospirosis: fuelling the fire? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2010, 104, 631-638. [CrossRef]

- Obels, I.; Mughini-Gras, L.; Maas, M.; Brandwagt, D.; van den Berge, N.; Notermans, D.W.; Franz, E.; van Elzakker, E.; Pijnacker, R. Increased incidence of human leptospirosis and the effect of temperature and precipitation, the Netherlands, 2005 to 2023. Euro Surveill 2025, 30. [CrossRef]

- Dreesman, J.; Toikkanen, S.; Runge, M.; Hamschmidt, L.; Lusse, B.; Freise, J.F.; Ehlers, J.; Nockler, K.; Knorr, C.; Keller, B.; et al. Investigation and response to a large outbreak of leptospirosis in field workers in Lower Saxony, Germany. Zoonoses Public Health 2023, 70, 315-326. [CrossRef]

- Pages, F.; Larrieu, S.; Simoes, J.; Lenabat, P.; Kurtkowiak, B.; Guernier, V.; Le Minter, G.; Lagadec, E.; Gomard, Y.; Michault, A.; et al. Investigation of a leptospirosis outbreak in triathlon participants, Reunion Island, 2013. Epidemiol Infect 2016, 144, 661-669. [CrossRef]

- Baharom, M.; Ahmad, N.; Hod, R.; Ja'afar, M.H.; Arsad, F.S.; Tangang, F.; Ismail, R.; Mohamed, N.; Mohd Radi, M.F.; Osman, Y. Environmental and Occupational Factors Associated with Leptospirosis: A Systematic Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23473. [CrossRef]

- Fairhead, L.J.; Smith, S.; Sim, B.Z.; Stewart, A.G.A.; Stewart, J.D.; Binotto, E.; Law, M.; Hanson, J. The seasonality of infections in tropical Far North Queensland, Australia: A 21-year retrospective evaluation of the seasonal patterns of six endemic pathogens. PLOS Glob Public Health 2022, 2, e0000506. [CrossRef]

- Casanovas-Massana, A.; Pedra, G.G.; Wunder, E.A., Jr.; Diggle, P.J.; Begon, M.; Ko, A.I. Quantification of Leptospira interrogans Survival in Soil and Water Microcosms. Appl Environ Microbiol 2018, 84. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Liu, Y.H.; Carter, A.; Kennedy, B.J.; Dermedgoglou, A.; Poulgrain, S.S.; Paavola, M.P.; Minto, T.L.; Luc, M.; Hanson, J. Severe leptospirosis in tropical Australia: Optimising intensive care unit management to reduce mortality. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019, 13, e0007929. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, V.; Trivedi, T.H.; Yeolekar, M.E. Epidemic of leptospirosis: an ICU experience. J Assoc Physicians India 2004, 52, 619-622.

- Smith, S.; Hanson, J. Improving the mortality of severe leptospirosis. Intensive Care Medicine 2020, 46, 827-828. [CrossRef]

- Miailhe, A.F.; Mercier, E.; Maamar, A.; Lacherade, J.C.; Le Thuaut, A.; Gaultier, A.; Asfar, P.; Argaud, L.; Ausseur, A.; Ben Salah, A.; et al. Severe leptospirosis in non-tropical areas: a nationwide, multicentre, retrospective study in French ICUs. Intensive Care Med 2019, 45, 1763-1773. [CrossRef]

- Fonseka, C.L.; Dahanayake, N.J.; Mihiran, D.J.D.; Wijesinghe, K.M.; Liyanage, L.N.; Wickramasuriya, H.S.; Wijayaratne, G.B.; Sanjaya, K.; Bodinayake, C.K. Pulmonary haemorrhage as a frequent cause of death among patients with severe complicated Leptospirosis in Southern Sri Lanka. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2023, 17, e0011352. [CrossRef]

- Pongpan, S.; Thanatrakolsri, P.; Vittaporn, S.; Khamnuan, P.; Daraswang, P. Prognostic Factors for Leptospirosis Infection Severity. Trop Med Infect Dis 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.; Smythe, L.; Weinstein, P. Leptospirosis: an emerging disease in travellers. Travel Med Infect Dis 2010, 8, 33-39. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Kennedy, B.J.; Dermedgoglou, A.; Poulgrain, S.S.; Paavola, M.P.; Minto, T.L.; Luc, M.; Liu, Y.H.; Hanson, J. A simple score to predict severe leptospirosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019, 13, e0007205. [CrossRef]

- Salaveria, K.; Smith, S.; Liu, Y.H.; Bagshaw, R.; Ott, M.; Stewart, A.; Law, M.; Carter, A.; Hanson, J. The Applicability of Commonly Used Severity of Illness Scores to Tropical Infections in Australia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2021, 106, 257-267. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.J.; Paris, D.H.; Newton, P.N. A Systematic Review of the Mortality from Untreated Leptospirosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9, e0003866. [CrossRef]

- Guzman Perez, M.; Blanch Sancho, J.J.; Segura Luque, J.C.; Mateos Rodriguez, F.; Martinez Alfaro, E.; Solis Garcia Del Pozo, J. Current Evidence on the Antimicrobial Treatment and Chemoprophylaxis of Human Leptospirosis: A Meta-Analysis. Pathogens 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Jian, M.; Su, X.; Pan, Y.; Duan, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhong, L.; Yang, J.; Song, J.; Wu, X.; et al. Efficacy and safety of antibiotics for treatment of leptospirosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Syst Rev 2024, 13, 108. [CrossRef]

- Win, T.Z.; Han, S.M.; Edwards, T.; Maung, H.T.; Brett-Major, D.M.; Smith, C.; Lee, N. Antibiotics for treatment of leptospirosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2024, 3, CD014960. [CrossRef]

- Trott, D.J.; Abraham, S.; Adler, B. Antimicrobial Resistance in Leptospira, Brucella, and Other Rarely Investigated Veterinary and Zoonotic Pathogens. Microbiol Spectr 2018, 6. [CrossRef]

- Guerrier, G.; Lefevre, P.; Chouvin, C.; D'Ortenzio, E. Jarisch-Herxheimer Reaction Among Patients with Leptospirosis: Incidence and Risk Factors. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017, 96, 791-794. [CrossRef]

- Bagshaw, R.J.; Stewart, A.G.A.; Smith, S.; Carter, A.W.; Hanson, J. The Characteristics and Clinical Course of Patients with Scrub Typhus and Queensland Tick Typhus Infection Requiring Intensive Care Unit Admission: A 23-year Case Series from Queensland, Tropical Australia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2020, 103, 2472-2477. [CrossRef]

- Price, C.; Smith, S.; Stewart, J.; Hanson, J. Acute Q Fever Patients Requiring Intensive Care Unit Support in Tropical Australia, 2015-2023. Emerg Infect Dis 2025, 31, 332-335. [CrossRef]

- Susilawati, T.N.; McBride, W.J. Undiagnosed undifferentiated fever in Far North Queensland, Australia: a retrospective study. Int J Infect Dis 2014, 27, 59-64. [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, F.; Riphagen-Dalhuisen, J.; Wijers, N.; Hak, E.; Van der Sande, M.A.; Morroy, G.; Schneeberger, P.M.; Schimmer, B.; Notermans, D.W.; Van der Hoek, W. Antibiotic therapy for acute Q fever in The Netherlands in 2007 and 2008 and its relation to hospitalization. Epidemiol Infect 2011, 139, 1332-1341. [CrossRef]

- Gavey, R.; Stewart, A.G.A.; Bagshaw, R.; Smith, S.; Vincent, S.; Hanson, J. Respiratory manifestations of rickettsial disease in tropical Australia; Clinical course and implications for patient management. Acta Trop 2025, 266, 107631. [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.; Rhodes, A.; Alhazzani, W.; Antonelli, M.; Coopersmith, C.M.; French, C.; Machado, F.R.; McIntyre, L.; Ostermann, M.; Prescott, H.C.; et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med 2021, 47, 1181-1247. [CrossRef]

- Fonseka, C.L.; Lekamwasam, S. Role of Plasmapheresis and Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in the Treatment of Leptospirosis Complicated with Pulmonary Hemorrhages. J Trop Med 2018, 2018, 4520185. [CrossRef]

- Rygård, S.L.; Butler, E.; Granholm, A.; Møller, M.H.; Cohen, J.; Finfer, S.; Perner, A.; Myburgh, J.; Venkatesh, B.; Delaney, A. Low-dose corticosteroids for adult patients with septic shock: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Intensive Care Med 2018, 44, 1003-1016. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, C.; Lakshitha de Silva, N.; Goonaratne, R.; Samarasekara, K.; Wijesinghe, I.; Parththipan, B.; Rajapakse, S. High dose corticosteroids in severe leptospirosis: a systematic review. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2014, 108, 743-750. [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, V.V.; Nagar, V.S.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Bhalgat, P.S.; Juvale, N.I. Pulmonary leptospirosis: an excellent response to bolus methylprednisolone. Postgrad Med J 2006, 82, 602-606. [CrossRef]

- Pitre, T.; Drover, K.; Chaudhuri, D.; Zeraaktkar, D.; Menon, K.; Gershengorn, H.B.; Jayaprakash, N.; Spencer-Segal, J.L.; Pastores, S.M.; Nei, A.M.; et al. Corticosteroids in Sepsis and Septic Shock: A Systematic Review, Pairwise, and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Explor 2024, 6, e1000. [CrossRef]

- National Sepsis Program. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/national-sepsis-program (accessed on 21 March ).

- Leptospirosis. Available online: https://www.tg.org.au (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Franklin, R.C.; King, J.C.; Aitken, P.J.; Elcock, M.S.; Lawton, L.; Robertson, A.; Mazur, S.M.; Edwards, K.; Leggat, P.A. Aeromedical retrievals in Queensland: A five-year review. Emerg Med Australas 2021, 33, 34-44. [CrossRef]

- Klement-Frutos, E.; Tarantola, A.; Gourinat, A.C.; Floury, L.; Goarant, C. Age-specific epidemiology of human leptospirosis in New Caledonia, 2006-2016. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0242886. [CrossRef]

- Spichler, A.; Athanazio, D.A.; Vilaca, P.; Seguro, A.; Vinetz, J.; Leake, J.A. Comparative analysis of severe pediatric and adult leptospirosis in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012, 86, 306-308. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.G.A.; Smith, S.; Binotto, E.; Hanson, J. Clinical Features of Rickettsial Infection in Children in Tropical Australia-A Report of 15 Cases. J Trop Pediatr 2020, 66, 655-660. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.A.; Costa, E.; Costa, Y.A.; Sacramento, E.; de Oliveira Junior, A.R.; Lopes, M.B.; Lopes, G.B. Comparative study of the in-hospital case-fatality rate of leptospirosis between pediatric and adult patients of different age groups. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2004, 46, 19-24. [CrossRef]

- Levett, P.N. Leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2001, 14, 296-326. [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, K.V.; Coburn, J. Leptospira as an emerging pathogen: a review of its biology, pathogenesis and host immune responses. Future Microbiol 2010, 5, 1413-1425. [CrossRef]

- Katz, A.R.; Ansdell, V.E.; Effler, P.V.; Middleton, C.R.; Sasaki, D.M. Assessment of the clinical presentation and treatment of 353 cases of laboratory-confirmed leptospirosis in Hawaii, 1974-1998. Clin Infect Dis 2001, 33, 1834-1841. [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, S.; Rodrigo, C.; Haniffa, R. Developing a clinically relevant classification to predict mortality in severe leptospirosis. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2010, 3, 213-219. [CrossRef]

- Marotto, P.C.; Ko, A.I.; Murta-Nascimento, C.; Seguro, A.C.; Prado, R.R.; Barbosa, M.C.; Cleto, S.A.; Eluf-Neto, J. Early identification of leptospirosis-associated pulmonary hemorrhage syndrome by use of a validated prediction model. J Infect 2010, 60, 218-223. [CrossRef]

- Galdino, G.S.; de Sandes-Freitas, T.V.; de Andrade, L.G.M.; Adamian, C.M.C.; Meneses, G.C.; da Silva Junior, G.B.; de Francesco Daher, E. Development and validation of a simple machine learning tool to predict mortality in leptospirosis. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 4506. [CrossRef]

- Jaureguiberry, S.; Roussel, M.; Brinchault-Rabin, G.; Gacouin, A.; Le Meur, A.; Arvieux, C.; Michelet, C.; Tattevin, P. Clinical presentation of leptospirosis: a retrospective study of 34 patients admitted to a single institution in metropolitan France. Clin Microbiol Infect 2005, 11, 391-394. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.G.A.; Smith, S.; Binotto, E.; McBride, W.J.H.; Hanson, J. The epidemiology and clinical features of rickettsial diseases in North Queensland, Australia: Implications for patient identification and management. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019, 13, e0007583. [CrossRef]

- Mar Minn, M.; Aung, N.M.; Kyaw, Z.; Zaw, T.T.; Chann, P.N.; Khine, H.E.; McLoughlin, S.; Kelleher, A.D.; Tun, N.L.; Oo, T.Z.C.; et al. The comparative ability of commonly used disease severity scores to predict death or a requirement for ICU care in patients hospitalised with possible sepsis in Yangon, Myanmar. Int J Infect Dis 2021, 104, 543-550. [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J.; Lee, S.J.; Mohanty, S.; Faiz, M.A.; Anstey, N.M.; Price, R.N.; Charunwatthana, P.; Yunus, E.B.; Mishra, S.K.; Tjitra, E.; et al. Rapid clinical assessment to facilitate the triage of adults with falciparum malaria, a retrospective analysis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e87020. [CrossRef]

- Niriella, M.A.; Liyanage, I.K.; Udeshika, A.; Liyanapathirana, K.V.; A, P.D.S.; H, J.d.S. Identification of dengue patients with high risk of severe disease, using early clinical and laboratory features, in a resource-limited setting. Arch Virol 2020, 165, 2029-2035. [CrossRef]

- Sreevalsan, T.V.; Chandra, R. Relevance of Polymerase Chain Reaction in Early Diagnosis of Leptospirosis. Indian J Crit Care Med 2024, 28, 290-293. [CrossRef]

- Win, T.Z.; Perinpanathan, T.; Mukadi, P.; Smith, C.; Edwards, T.; Han, S.M.; Maung, H.T.; Brett-Major, D.M.; Lee, N. Antibiotic prophylaxis for leptospirosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2024, 3, CD014959. [CrossRef]

- Lingappa, J.; Kuffner, T.; Tappero, J.; Whitworth, W.; Mize, A.; Kaiser, R.; McNicholl, J. HLA-DQ6 and ingestion of contaminated water: possible gene-environment interaction in an outbreak of Leptospirosis. Genes Immun 2004, 5, 197-202. [CrossRef]

- Agampodi, S.B.; Matthias, M.A.; Moreno, A.C.; Vinetz, J.M. Utility of quantitative polymerase chain reaction in leptospirosis diagnosis: association of level of leptospiremia and clinical manifestations in Sri Lanka. Clin Infect Dis 2012, 54, 1249-1255. [CrossRef]

- Hochedez, P.; Theodose, R.; Olive, C.; Bourhy, P.; Hurtrel, G.; Vignier, N.; Mehdaoui, H.; Valentino, R.; Martinez, R.; Delord, J.M.; et al. Factors Associated with Severe Leptospirosis, Martinique, 2010-2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2015, 21, 2221-2224. [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Zanzi, C.; Dreyfus, A.; Limothai, U.; Foley, W.; Srisawat, N.; Picardeau, M.; Haake, D.A. Leptospirosis-Improving Healthcare Outcomes for a Neglected Tropical Disease. Open Forum Infect Dis 2025, 12, ofaf035. [CrossRef]

- Tshokey, T.; Ko, A.I.; Currie, B.J.; Munoz-Zanzi, C.; Goarant, C.; Paris, D.H.; Dance, D.A.B.; Limmathurotsakul, D.; Birnie, E.; Bertherat, E.; et al. Leptospirosis, melioidosis, and rickettsioses in the vicious circle of neglect. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2025, 19, e0012796. [CrossRef]

- Bird, K.; Bohanna, I.; McDonald, M.; Wapau, H.; Blanco, L.; Cullen, J.; McLucas, J.; Forbes, S.; Vievers, A.; Wason, A.; et al. A good life for people living with disability: the story from Far North Queensland. Disabil Rehabil 2024, 46, 1787-1795. [CrossRef]

| Variable | All n=111 | No severe disease n=48 | Severe disease n=63 | P |

| Age (years) | 38 (24-55) | 32 (19-48) | 41 (26-63) | 0.03 |

| Child (age <16 years) | 6 (5%) | 3 (6%) | 3 (5%) | 1.00 |

| Male sex | 94 (85%) | 38 (79%) | 56 (89%) | 0.19 |

| Remote residence a | 17 (15%) | 6 (12%) | 11 (18%) | 0.60 |

| Rural residence b | 89 (80%) | 36 (75%) | 53 (84%) | 0.23 |

| Wet season presentation c | 67 (60%) | 31 (63%) | 36 (58%) | 0.44 |

| Days of symptoms before presentation | 4 (2-5) | 4 (2-5) | 5 (3-6) | 0.07 |

| Any comorbidity d | 13 (12%) | 3 (6%) | 10 (16%) | 0.15 |

| Diabetes mellitus d | 2 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1.0 |

| Cardiac failure d | 3 (3%) | 0 | 3 (5%) | 0.26 |

| Ischaemic heart disease d | 2 (2%) | 0 | 2 (3%) | 0.51 |

| Chronic kidney disease d | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Lung disease d | 5 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (6%) | 0.39 |

| Liver disease d | 5 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (6%) | 0.39 |

| Malignancy d | 2 (2%) | 0 | 2 (3%) | 0.51 |

| Autoimmune disease d | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Immunosuppressed d | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Hazardous Alcohol use d | 29 (26%) | 12 (24%) | 17 (27%) | 0.81 |

| Smoker d | 41 (37%) | 14 (29%) | 27 (43%) | 0.14 |

| Serovar Zanoni | 21/59 (37%) | 7/30 (23%) | 14/29 (48%) | 0.06 |

| Serovar Australis | 12/59 (20%) | 6/40 (20%) | 6/29 (21%) | 0.72 |

| Variable | Number with data | All n=111 | No severe disease n=48 | Severe disease n=63 | P |

| Subjective symptoms | |||||

| Headache | 111 | 80 (72%) | 40 (83%) | 40 (63%) | 0.02 |

| Fevers | 111 | 106 (96%) | 45 (94%) | 61 (97%) | 0.65 |

| Rigors | 111 | 40 (36%) | 18 (38%) | 22 (35%) | 0.78 |

| Confusion | 111 | 8 (7%) | 3 (6%) | 5 (8%) | 1.00 |

| Fatigue | 111 | 43 (39%) | 14 (29%) | 29 (47%) | 0.07 |

| Abdominal pain | 111 | 42 (38%) | 20 (41%) | 22 (35%) | 0.47 |

| Myalgia | 111 | 83 (75%) | 34 (71%) | 49 (79%) | 0.40 |

| Arthralgia | 111 | 48 (43%) | 17 (35%) | 31 (49%) | 0.15 |

| Diarrhoea | 111 | 41 (37%) | 14 (29%) | 27 (43%) | 0.14 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 111 | 74 (67%) | 35 (73%) | 39 (62%) | 0.14 |

| Chest pain | 111 | 9 (8%) | 4 (8%) | 5 (8%) | 1.00 |

| Dyspnoea | 111 | 16 (14%) | 2 (4%) | 14 (22%) | 0.01 |

| Cough | 111 | 33 (30%) | 11 (23%) | 22 (35%) | 0.17 |

| URTI symptoms | 111 | 15 (14%) | 6 (12%) | 9 (15%) | 1.00 |

| Haemoptysis | 111 | 12 (11%) | 0 | 12 (19%) | 0.001 |

| Abnormal bleeding or bruising | 111 | 11 (10%) | 3 (6%) | 8 (13%) | 0.34 |

| Objective examination findings | |||||

| Hepatomegaly | 111 | 11 (10%) | 4 (8%) | 7 (11%) | 0.75 |

| Splenomegaly | 111 | 0 | - | - | - |

| Lymphadenopathy | 111 | 6 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 5 (8%) | 0.23 |

| Conjunctival suffusion | 111 | 23 (21%) | 11 (23%) | 12 (19%) | 0.62 |

| Skin rash | 111 | 19 (17%) | 11 (23%) | 8 (13%) | 0.21 |

| Abnormal chest auscultation | 111 | 44 (40%) | 13 (27%) | 31 (49%) | 0.02 |

| Vital signs at presentation | |||||

| Oliguria a | 111 | 42 (38%) | 9 (19%) | 33 (52%) | <0.001 |

| Fever > 38.0° Celsius | 111 | 21 (38%) | 7 (15%) | 14 (22%) | 0.34 |

| Supplemental oxygen administered | 111 | 23 (21%) | 2 (4%) | 21 (33%) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory rate ≥ 22 beaths/minute | 111 | 44 (40%) | 14 (29%) | 30 (48%) | 0.049 |

| Heart rate ≥ 100 beats/minute | 111 | 54 (49%) | 17 (35%) | 37 (59%) | 0.02 |

| Systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg | 111 | 56 (50%) | 12 (25%) | 44 (70%) | <0.001 |

| Disease severity score | |||||

| SPiRO score b | 111 | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-1) | 2 (1-3) | <0.001 |

| Variable | Units | Number with data |

All n=111 |

No severe disease n=48 |

Severe disease n=63 |

P |

| Haemoglobin initial | g/dL | 111 | 134 (111-147) | 139 (129-150) | 131 (120-145) | 0.02 |

| Haemoglobin lowest | g/dL | 111 | 112 (98-123) | 122 (110-129) | 103 (86-119) | <0.0001 |

| White cell initial | x109/L | 111 | 9.3 (6.8-11.9) | 8.2 (6.3-11.0) | 9.8 (7.2-12.8) | 0.046 |

| White cell highest | x109/L | 111 | 12.8 (9.5-18.3) | 10.6 (8.1-13.3) | 15.9 (11.9-22.1) | <0.0001 |

| White cell lowest | x109/L | 111 | 5.7 (4.2-7.8) | 5.5 (4.2-6.9) | 6.1 (4.2-8.4) | 0.32 |

| Platelet initial | x109/L | 111 | 119 (72-165) | 146 (113-197) | 84 (47-141) | <0.0001 |

| Platelet count lowest | x109/L | 111 | 84 (33-121) | 115 (90-147) | 54 (24-90) | <0.0001 |

| Neutrophil initial | x109/L | 111 | 8.2 (5.5-10.6) | 6.7 (4.6-9.3) | 8.5 (6.3-11.7) | 0.02 |

| Neutrophil highest | x109/L | 111 | 10.7 (8.1-14.2) | 9.0 (6.1-11.8) | 12.8 (10.0-19.9) | <0.0001 |

| Neutrophil lowest | x109/L | 111 | 3.5 (2.7-5.6) | 3.4 (2.5-4.6) | 4.0 (2.8-6.1) | 0.10 |

| Lymphocyte initial | x109/L | 111 | 0.5 (0.3-0.7) | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | 0.005 |

| Lymphocyte lowest | x109/L | 111 | 0.3 (0.2-0.5) | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | 0.3 (0.2-0.4) | 0.0001 |

| INR initial | - | 85 | 1.1 (1.1-1.3) | 1.1 (1.1-1.1) | 1.1 (1.1-1.3) | 0.02 |

| INR highest | - | 85 | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | 1.1 (1.1-1.1) | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) | 0.0002 |

| APTT initial | seconds | 111 | 31 (29-34) | 31 (29-33) | 31 (28-34) | 0.52 |

| APTT highest | seconds | 111 | 32 (30-36) | 31 (29-33) | 33 (30-39) | 0.004 |

| Variable | Units | Number with data | All n=111 | No severe disease n=48 | Severe disease n=63 | P |

| Initial serum sodium | mmol/L | 111 | 133 (129-135) | 134 (130-137) | 132 (128-135) | 0.01 |

| Lowest serum sodium | mmol/L | 111 | 132 (129-135) | 133 (130-136) | 131 (126-134) | 0.001 |

| Initial serum potassium | mmol/L | 111 | 3.7 (3.4-4.0) | 3.7 (3.4-4.0) | 3.6 (3.4-4.0) | 0.55 |

| Lowest serum potassium | mmol/L | 111 | 4.4 (4.0-4.9) | 4.2 (3.8-4.7) | 4.6 (4.2-4.9) | 0.0003 |

| eGFR initial | mL/min/1.73 m2 | 99 | 64 (25-90) | 77 (27-90) | 54 (25-78) | 0.12 |

| eGFR lowest | mL/min/1.73 m2 | 99 | 38 (14-78) | 76 (18-90) | 25 (14-54) | 0.002 |

| Initial serum creatinine | µmol/L | 111 | 113 (88-205) | 100 (81-197) | 124 (93-232) | 0.04 |

| Highest serum creatinine | µmol/L | 111 | 179 (102-382) | 107 (85-337) | 211 (142-433) | 0.0008 |

| Initial serum bicarbonate | mmol/L | 111 | 23 (21-25) | 24 (22-26) | 23 (21-25) | 0.07 |

| Lowest serum bicarbonate | mmol/L | 111 | 20 (17-22) | 22 (19-23) | 19 (16-21) | 0.0001 |

| Initial serum bilirubin | µmol/L | 111 | 18 (12-28) | 16 (10-26) | 19 (13-29) | 0.19 |

| Highest serum bilirubin | µmol/L | 111 | 26 (19-48) | 20 (12-45) | 29 (21-50) | 0.004 |

| Initial serum ALT | IU/ml | 111 | 68 (27-115) | 68 (26-126) | 67 (27-110) | 0.91 |

| Highest serum ALT | IU/ml | 111 | 121 (68-208) | 131 (69-189) | 120 (68-220) | 0.66 |

| Initial serum AST | IU/ml | 111 | 63 (34-135) | 67 (32-113) | 59 (34-143) | 0.37 |

| Highest serum AST | IU/ml | 111 | 131 (74-210) | 102 (67-166) | 153 (80-287) | 0.02 |

| Initial serum GGT | IU/ml | 111 | 51 (22-120) | 52 (23-159) | 48 (22-103) | 0.66 |

| Highest serum GGT | IU/ml | 111 | 135 (70-235) | 142 (69-297) | 135 (70-217) | 0.57 |

| Initial serum SAP | IU/ml | 111 | 98 (67-171) | 113 (70-164) | 89 (64-174) | 0.49 |

| Highest serum SAP | IU/ml | 111 | 146 (109-208) | 143 (114-221) | 152 (91-208) | 0.88 |

| Initial serum LDH | IU/ml | 111 | 296 (236-359) | 295 (238-358) | 296 (234-386) | 0.66 |

| Highest serum LDH | IU/ml | 111 | 400 (327-534) | 359 (280-401) | 480 (377-690) | <0.0001 |

| Initial serum CK | IU/ml | 83 | 281 (104-1020) | 124 (73-438) | 486 (118-1160) | 0.01 |

| Highest serum CK | IU/ml | 83 | 350 (114-1020) | 124 (73-438) | 621 (124-1225) | 0.004 |

| Initial serum CRP | mg/L | 107 | 190 (138-287) | 156 (102-234) | 233 (165-323) | 0.002 |

| Highest serum CRP | mg/L | 107 | 227 (159-323) | 187 (137-238) | 258 (195-353) | 0.0002 |

| Initial serum lactate | mmol/L | 105 | 1.5 (1.1-2.3) | 1.3 (1.0-1.8) | 1.7 (1.2-2.4) | 0.02 |

| Highest serum lactate | mmol/L | 105 | 2.0 (1.4-2.7) | 1.5 (1.2-2.3) | 2.2 (1.8-3.6) | 0.0001 |

| Elevated initial serum troponin a | - | 111 | 25/111 (23%) | 2/48 (4%) | 23/63 (37%) | <0.0001 |

| Elevated serum troponin during hospitalisation a | - | 111 | 2/48 (4%) | 27/63 (43%) | <0.0001 |

| Variable | Number with data | All n=111 | No severe disease n=48 | Severe disease n=63 | P |

| Abnormal initial chest imaging | 109 | 37/109 (34%) | 10/46 (22%) | 27 (43%) | 0.02 |

| Any abnormal chest imaging during hospitalisation | 109 | 63/109 (58%) | 17/46 (37%) | 46 (73%) | <0.001 |

| Multilobar involvement | 109 | 49/109 (45%) | 12/46 (26%) | 38 (60%) | <0.001 |

| Alveolar changes | 109 | 54/109 (49%) | 10/46 (22%) | 44 (70%) | <0.001 |

| Interstitial changes | 109 | 25/109 (23%) | 6/46 (13%) | 19 (30%) | 0.04 |

| Pleural effusion | 109 | 19/109 (17%) | 8/46 (17%) | 12 (19%) | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).