Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

Ethical Approval

3. Results

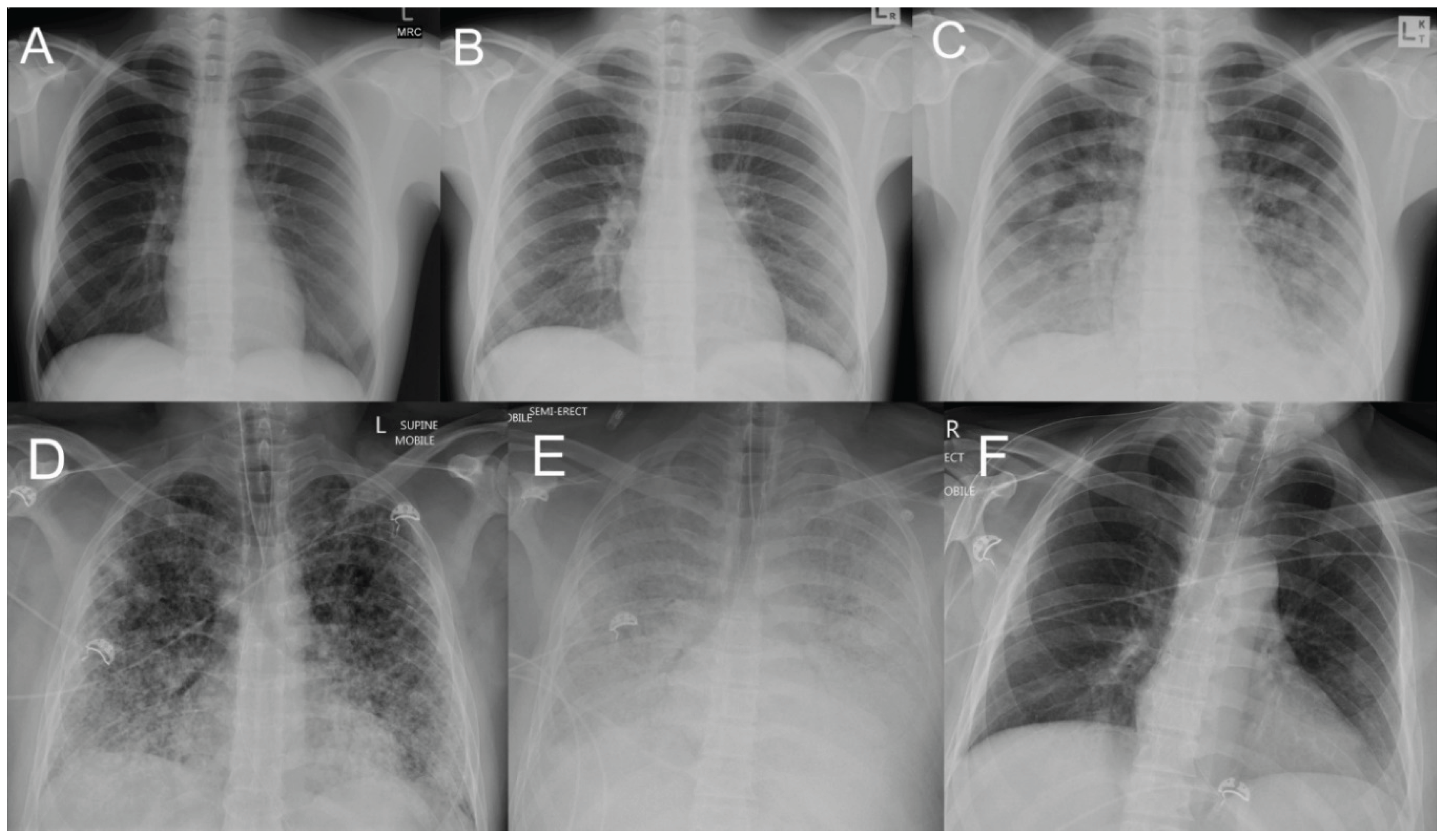

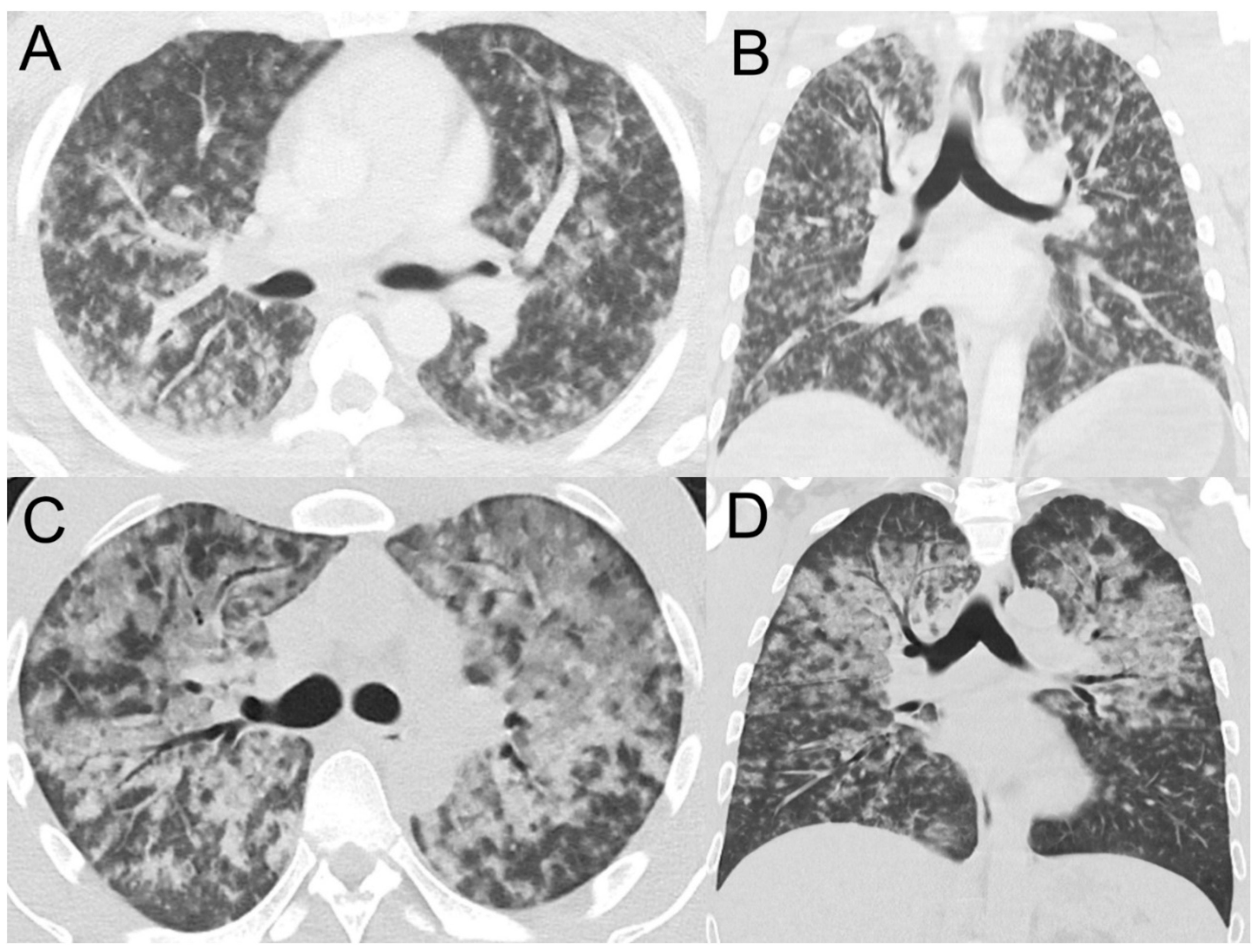

3.1. Lung Involvement

3.2. Pulmonary Haemorrhage

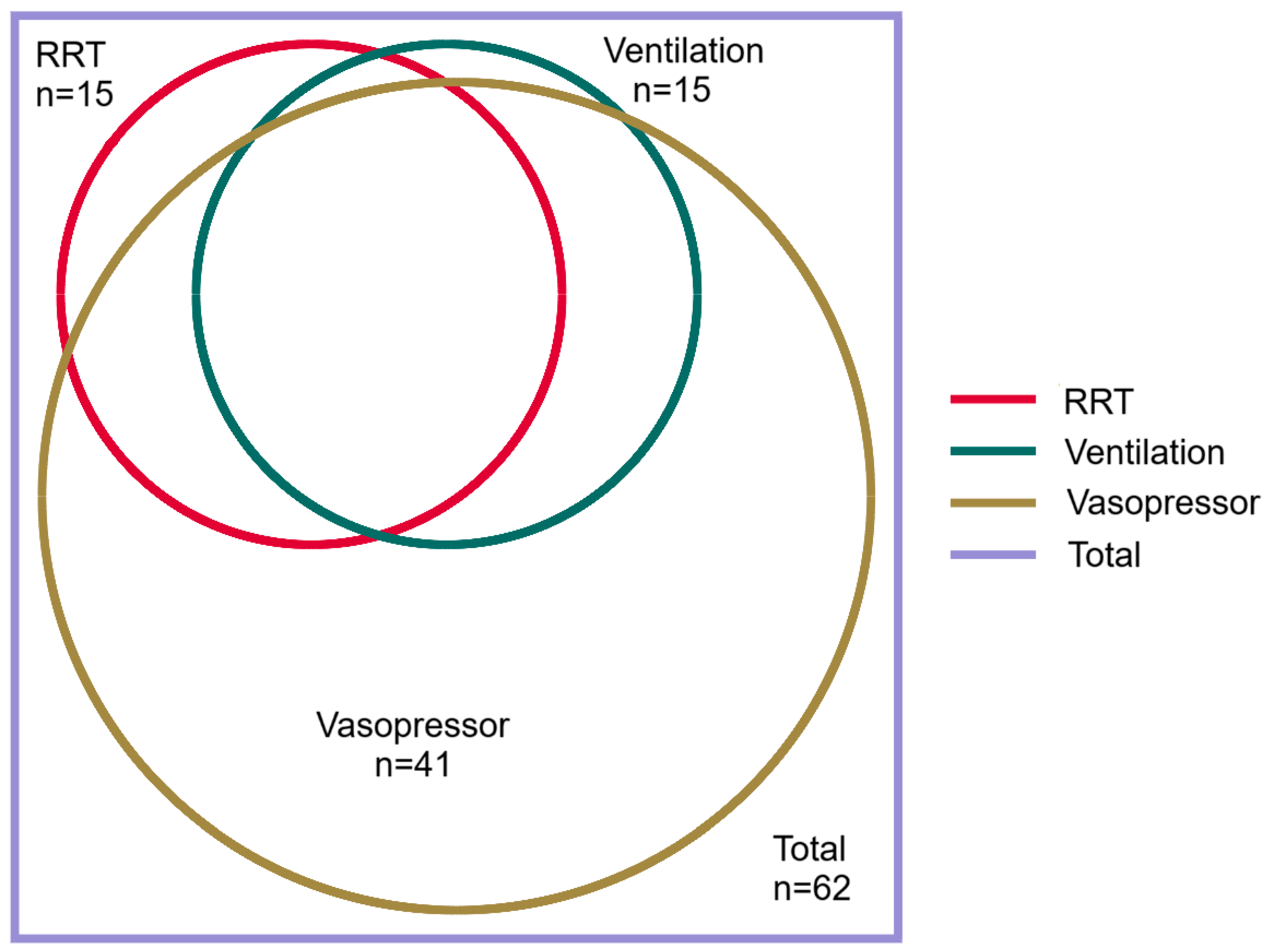

3.4. Clinical Course and Therapy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| ARDS | Acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| DIC | Disseminated intravascular coagulation |

| ECMO | Extracorporeal membranous oxygenation |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| RRT | Renal replacement therapy |

References

- Costa F, Hagan JE, Calcagno J, Kane M, Torgerson P, Martinez-Silveira MS, et al. Global Morbidity and Mortality of Leptospirosis: A Systematic Review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(9):e0003898. [CrossRef]

- Chawla V, Trivedi TH, Yeolekar ME. Epidemic of leptospirosis: an ICU experience. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:619-22.

- Muñoz-Zanzi C, Dreyfus A, Limothai U, Foley W, Srisawat N, Picardeau M, et al. Leptospirosis—Improving Healthcare Outcomes for a Neglected Tropical Disease. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2025;12(2). [CrossRef]

- Cagliero J, Villanueva S, Matsui M. Leptospirosis Pathophysiology: Into the Storm of Cytokines. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:204. [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse S, Fernando N, Dreyfus A, Smith C, Rodrigo C. Leptospirosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2025;11(1):32. [CrossRef]

- Samrot AV, Sean TC, Bhavya KS, Sahithya CS, Chan-drasekaran S, Palanisamy R, et al. Leptospiral Infection, Pathogenesis and Its Diagnosis—A Review. Pathogens. 2021;10(2):145. [CrossRef]

- Evangelista KV, Coburn J. Leptospira as an emerging pathogen: a review of its biology, pathogenesis and host immune responses. Future Microbiol. 2010;5(9):1413-25. [CrossRef]

- Budiono E, Sumardi, Riyanto BS, Hisyam B, Hartopo AB. Pulmonary involvement predicts mortality in severe leptospirosis patients. Acta Med Indones. 2009;41(1):11-4.

- Spichler AS, Vilaça PJ, Athanazio DA, Albuquerque JO, Buzzar M, Castro B, et al. Predictors of lethality in severe leptospirosis in urban Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79(6):911-4.

- Rajapakse S, Rodrigo C, Haniffa R. Developing a clinically relevant classification to predict mortality in severe leptospirosis. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3(3):213-9. [CrossRef]

- So RAY, Danguilan RA, Chua E, Arakama MI, Ginete-Garcia JKB, Chavez JR. A Scoring Tool to Predict Pulmonary Complications in Severe Leptospirosis with Kidney Failure. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7(1). [CrossRef]

- Win TZ, Han SM, Edwards T, Maung HT, Brett-Major DM, Smith C, et al. Antibiotics for treatment of leptospirosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024;3(3):CD014960. [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Thompson BT, Hayden D, deBoisblanc B, et al. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2564-75. [CrossRef]

- Smith S, Liu YH, Carter A, Kennedy BJ, Dermedgoglou A, Poulgrain SS, et al. Severe leptospirosis in tropical Australia: Optimising intensive care unit management to reduce mortality. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(12):e0007929. [CrossRef]

- Karnik ND, Patankar AS. Leptospirosis in Intensive Care Unit. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2021;25(Suppl 2):S134-s7. [CrossRef]

- Kularatne SA, Budagoda BD, de Alwis VK, Wickramasinghe WM, Bandara JM, Pathirage LP, et al. High efficacy of bolus methylprednisolone in severe leptospirosis: a descriptive study in Sri Lanka. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87(1023):13-7. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo C, Lakshitha de Silva N, Goonaratne R, Samarasekara K, Wijesinghe I, Parththipan B, et al. High dose corticosteroids in severe leptospirosis: a systematic review. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;108(12):743-50. [CrossRef]

- Trivedi SV, Vasava AH, Bhatia LC, Patel TC, Patel NK, Patel NT. Plasma exchange with immunosuppression in pulmonary alveolar haemorrhage due to leptospirosis. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:429-33.

- Fonseka CL, Dahanayake NJ, Mihiran DJD, Wijesinghe KM, Liyanage LN, Wickramasuriya HS, et al. Pulmonary haemorrhage as a frequent cause of death among patients with severe complicated Leptospirosis in Southern Sri Lanka. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17(10):e0011352. [CrossRef]

- Milovanovic L, Singh G, Townsend D, Nagendran J, Sligl W. Extracorporeal Life Support for Severe Leptospirosis: Case Series and Narrative Review. J Assoc Med Microbiol Infect Dis Can. 2024;9(3):173-82. [CrossRef]

- Zhang P, Zheng J, Shan X, Zhou B. Advances in the study of nebulized tranexamic acid for pulmonary hemorrhage. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2025;81(2):237-46. [CrossRef]

- National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System Canberra: Australian Government. Department of Health Disability and Aging; 2025 [Available from: https://nindss.health.gov.au/pbi-dashboard/.

- Smith S, Kennedy BJ, Dermedgoglou A, Poulgrain SS, Paavola MP, Minto TL, et al. A simple score to predict severe leptospirosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(2):e0007205. [CrossRef]

- Stratton H, Rosengren P, Kinneally T, Prideaux L, Smith S, Hanson J. Presentation and Clinical Course of Leptospirosis in a Referral Hospital in Far North Queensland, Tropical Australia. Pathogens. 2025;14(7). [CrossRef]

- Fairhead LJ, Smith S, Sim BZ, Stewart AGA, Stewart JD, Binotto E, et al. The seasonality of infections in tropical Far North Queensland, Australia: A 21-year retrospective evaluation of the seasonal patterns of six endemic pathogens. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022;2(5):e0000506. [CrossRef]

- Climate statistics for Australian locations. Summary statistics Cairns Aero.: Bureau of Meterology; 2025 [Available from: https://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_031011.shtml.

- Leptospirosis – Laboratory case definition Canberra: Public Health Laboratory Network; 2007 [Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/leptospirosis-laboratory-case-definition?language=en.

- Leptospirosis Reference Laboratory. Accreditations, certifications and terms of reference. Brisbane: Queensland Government; [Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/public-health/forensic-and-scientific-services/testing-analysis/disease-investigation-and-analysis/leptospirosis-reference-laboratory/laboratory-accreditation-and-certification.

- Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. Jama. 2012;307(23):2526-33. [CrossRef]

- Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Hayden DL, Schoenfeld DA, Ware LB. Comparison of the SpO2/FIO2 ratio and the PaO2/FIO2 ratio in patients with acute lung injury or ARDS. Chest. 2007;132(2):410-7. [CrossRef]

- Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(11):1181-247. [CrossRef]

- Silva JJ, Dalston MO, Carvalho JE, Setúbal S, Oliveira JM, Pereira MM. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features of the severe pulmonary form of leptospirosis. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2002;35(4):395-9. [CrossRef]

- Matos ED, Costa E, Sacramento E, Caymmi AL, Neto CA, Barreto Lopes M, et al. Chest radiograph abnormalities in patients hospitalized with leptospirosis in the city of Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. 2001;5(2):73-7. [CrossRef]

- Tanomkiat W, Poonsawat P. Pulmonary radiographic findings in 118 leptospirosis patients. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005;36(5):1247-51.

- Marchiori E, Lourenço S, Setúbal S, Zanetti G, Gasparetto TD, Hochhegger B. Clinical and imaging manifestations of hemorrhagic pulmonary leptospirosis: a state-of-the-art review. Lung. 2011;189(1):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Dolhnikoff M, Mauad T, Bethlem EP, Carvalho CR. Pathology and pathophysiology of pulmonary manifestations in leptospirosis. Braz J Infect Dis. 2007;11(1):142-8. [CrossRef]

- Nicodemo AC, Duarte MI, Alves VA, Takakura CF, Santos RT, Nicodemo EL. Lung lesions in human leptospirosis: microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural features related to thrombocytopenia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56(2):181-7. [CrossRef]

- Arean VM. The pathologic anatomy and pathogenesis of fatal human leptospirosis (Weil's disease). Am J Pathol. 1962;40(4):393-423.

- Dolhnikoff M, Mauad T, Bethlem EP, Carvalho CR. Leptospiral pneumonias. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2007;13(3):230-5. [CrossRef]

- Nicodemo AC, Duarte-Neto AN. Pathogenesis of Pulmonary Hemorrhagic Syndrome in Human Leptospirosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;104(6):1970-2. [CrossRef]

- Thammakumpee K, Silpapojakul K, Borrirak B. Leptospirosis and its pulmonary complications. Respirology. 2005;10(5):656-9. [CrossRef]

- Tubiana S, Mikulski M, Becam J, Lacassin F, Lefèvre P, Gourinat AC, et al. Risk factors and predictors of severe leptospirosis in New Caledonia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(1):e1991. [CrossRef]

- Andrade L, Rodrigues AC, Jr., Sanches TR, Souza RB, Seguro AC. Leptospirosis leads to dysregulation of sodium transporters in the kidney and lung. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292(2):F586-92. [CrossRef]

- Segura ER, Ganoza CA, Campos K, Ricaldi JN, Torres S, Silva H, et al. Clinical spectrum of pulmonary involvement in leptospirosis in a region of endemicity, with quantification of leptospiral burden. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(3):343-51. [CrossRef]

- Marotto PC, Nascimento CM, Eluf-Neto J, Marotto MS, Andrade L, Sztajnbok J, et al. Acute lung injury in leptospirosis: clinical and laboratory features, outcome, and factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29(6):1561-3. [CrossRef]

- Gulati S, Gulati A. Pulmonary manifestations of leptospirosis. Lung India. 2012;29(4):347-53. [CrossRef]

- Haake DA, Levett PN. Leptospirosis in humans. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;387:65-97. [CrossRef]

- Ioachimescu OC, Stoller JK. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage: diagnosing it and finding the cause. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(4):258, 60, 64-5 passim. [CrossRef]

- Donaghy M, Rees AJ. Cigarette smoking and lung haemorrhage in glomerulonephritis caused by autoantibodies to glomerular basement membrane. Lancet. 1983;2(8364):1390-3. [CrossRef]

- National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–2023. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health Welfare; 2025.

- Levett PN. Leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14(2):296-326. [CrossRef]

- Abdulkader RC, Daher EF, Camargo ED, Spinosa C, da Silva MV. Leptospirosis severity may be associated with the intensity of humoral immune response. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2002;44(2):79-83. [CrossRef]

- Shenoy VV, Nagar VS, Chowdhury AA, Bhalgat PS, Juvale NI. Pulmonary leptospirosis: an excellent response to bolus methylprednisolone. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(971):602-6. [CrossRef]

- Luks AM, Lakshminarayanan S, Hirschmann JV. Leptospirosis presenting as diffuse alveolar hemorrhage: case report and literature review. Chest. 2003;123(2):639-43. [CrossRef]

- Niwattayakul K, Kaewtasi S, Chueasuwanchai S, Hoontrakul S, Chareonwat S, Suttinont C, et al. An open randomized controlled trial of desmopressin and pulse dexamethasone as adjunct therapy in patients with pulmonary involvement associated with severe leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(8):1207-12. [CrossRef]

- Petakh P, Oksenych V, Kamyshnyi O. Corticosteroid Treatment for Leptospirosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2024;13(15). [CrossRef]

- Bagshaw RJ, Stewart AGA, Smith S, Carter AW, Hanson J. The Characteristics and Clinical Course of Patients with Scrub Typhus and Queensland Tick Typhus Infection Requiring Intensive Care Unit Admission: A 23-year Case Series from Queensland, Tropical Australia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(6):2472-7. [CrossRef]

- Price C, Smith S, Stewart J, Hanson J. Acute Q Fever Patients Requiring Intensive Care Unit Support in Tropical Australia, 2015-2023. Emerg Infect Dis. 2025;31(2):332-5. [CrossRef]

- Izurieta R, Galwankar S, Clem A. Leptospirosis: The "mysterious" mimic. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2008;1(1):21-33. [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra F, Riphagen-Dalhuisen J, Wijers N, Hak E, Van der Sande MA, Morroy G, et al. Antibiotic therapy for acute Q fever in The Netherlands in 2007 and 2008 and its relation to hospitalization. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139(9):1332-41. [CrossRef]

- Biggs HM, Behravesh CB, Bradley KK, Dahlgren FS, Drexler NA, Dumler JS, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Tickborne Rickettsial Diseases: Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and Other Spotted Fever Group Rickettsioses, Ehrlichioses, and Anaplasmosis - United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(2):1-44. [CrossRef]

- Gavey R, Stewart AGA, Bagshaw R, Smith S, Vincent S, Hanson J. Respiratory manifestations of rickettsial disease in tropical Australia; Clinical course and implications for patient management. Acta Trop. 2025;266:107631. [CrossRef]

- Hanson JP, Lam SW, Mohanty S, Alam S, Pattnaik R, Mahanta KC, et al. Fluid resuscitation of adults with severe falciparum malaria: effects on Acid-base status, renal function, and extravascular lung water. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(4):972-81. [CrossRef]

- Casey JD, Semler MW, Rice TW. Fluid Management in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;40(1):57-65. [CrossRef]

- Naorungroj T, Prajantasen U, Sanla-Ead T, Viarasilpa T, Tongyoo S. Restrictive fluid management with early de-escalation versus usual care in critically ill patients (reduce trial): a feasibility randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2025;29(1):405. [CrossRef]

- Warrell DA, Looareesuwan S, Warrell MJ, Kasemsarn P, Intaraprasert R, Bunnag D, et al. Dexamethasone proves deleterious in cerebral malaria. A double-blind trial in 100 comatose patients. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(6):313-9. [CrossRef]

- Nedel WL, Nora DG, Salluh JI, Lisboa T, Póvoa P. Corticosteroids for severe influenza pneumonia: A critical appraisal. World J Crit Care Med. 2016;5(1):89-95. [CrossRef]

- Losonczy LI, Papali A, Kivlehan S, Calvello Hynes EJ, Calderon G, Laytin A, et al. White Paper on Early Critical Care Services in Low Resource Settings. Ann Glob Health. 2021;87(1):105. [CrossRef]

- Schultz MJ, Dunser MW, Dondorp AM, Adhikari NK, Iyer S, Kwizera A, et al. Current challenges in the management of sepsis in ICUs in resource-poor settings and suggestions for the future. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(5):612-24. [CrossRef]

- Katz AR, Ansdell VE, Effler PV, Middleton CR, Sasaki DM. Assessment of the clinical presentation and treatment of 353 cases of laboratory-confirmed leptospirosis in Hawaii, 1974-1998. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(11):1834-41. [CrossRef]

- Berman SJ, Tsai CC, Holmes K, Fresh JW, Watten RH. Sporadic anicteric leptospirosis in South Vietnam. A study in 150 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79(2):167-73. [CrossRef]

- Trevejo RT, Rigau-Pérez JG, Ashford DA, McClure EM, Jarquín-González C, Amador JJ, et al. Epidemic leptospirosis associated with pulmonary hemorrhage-Nicaragua, 1995. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(5):1457-63. [CrossRef]

- Seijo A, Coto H, San Juan J, Videla J, Deodato B, Cernigoi B, et al. Lethal leptospiral pulmonary hemorrhage: an emerging disease in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(9):1004-5. [CrossRef]

- Vijayachari P, Sugunan AP, Sharma S, Roy S, Natarajaseenivasan K, Sehgal SC. Leptospirosis in the Andaman Islands, India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102(2):117-22. [CrossRef]

- Vinetz JM. Leptospirosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2001;14(5):527-38. [CrossRef]

- Smythe L, Dohnt M, Norris M, Symonds M, Scott J. Review of leptospirosis notifications in Queensland 1985 to 1996. Commun Dis Intell. 1997;21(2):17-20. [CrossRef]

| Variable | All n=109 |

No lung involvement a n=47 |

Lung involvement a n=62 |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38 (24-56) | 33 (21-53) | 42 (26-62) | 0.07 |

| Child (age <16 years) | 6 (6) | 3 (6) | 3 (5) | 1.0 |

| Male sex | 93 (85) | 39 (83) | 54 (87) | 0.55 |

| Rural or remote residence b | 87 (80) | 36 (77) | 51 (81) | 0.47 |

| Wet season presentation | 65 (60) | 28 (60) | 37 (60) | 0.99 |

| Leptospirosis in initial differential diagnosis | 70 (64) | 32 (68) | 38 (61) | 0.46 |

| Duration of symptoms prior to antibiotic therapy (days) | 4 (3-5) | 3 (2-5) | 5 (4-6) | 0.001 |

| Any comorbidity c | 13 (12) | 6 (13) | 7 (11) | 1.0 |

| Diabetes mellitus c | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1.0 |

| Cardiac failure c | 3 (3) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 0.58 |

| Ischaemic heart disease c | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1.0 |

| Chronic kidney disease c | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Chronic lung disease c | 5 (5) | 2 (4) | 3 (5) | 1.0 |

| Liver disease c | 5 (5) | 3 (6) | 2 (3) | 0.65 |

| Malignancy c | 2 (2) | 0 | 2 (3) | 0.51 |

| Autoimmune disease c | 0 | - | - | - |

| Immunosuppressed c | 0 | - | - | - |

| Hazardous Alcohol use c | 29 (27) | 13 (28) | 16 (26) | 0.83 |

| Current smoker d | 40 (37) | 14 (30) | 26 (42) | 0.19 |

| PCR positive d | 88/98 (90) | 33/40 (83) | 55/58 (95) | 0.09 |

| Culture positive d | 30/47 (63) | 15/21 (71) | 14/26 (54) | 0.25 |

| Either PCR or culture positive d | 92/101 (91) | 35/41 (85) | 57/60 (95) | 0.15 |

| Serovar Zanoni d | 24/62 (39) | 7/29 (24) | 17/33 (52) | 0.04 |

| Serovar Australis d | 12/62 (19) | 5/29 (17) | 7/33 (21) | 1.0 |

| Variable | All n=109 |

No lung involvement a n=47 |

Lung involvement a n=62 |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective symptoms | ||||

| Headache | 79 (72) | 36 (77) | 43 (69) | 0.40 |

| Fevers | 104 (95) | 46 (98) | 58 (94) | 0.39 |

| Rigors | 40 (37) | 16 (34) | 24 (39) | 0.62 |

| Confusion | 8 (7) | 2 (4) | 6 (10) | 0.46 |

| Fatigue | 43 (39) | 16 (34) | 27 (44) | 0.32 |

| Abdominal pain | 42 (39) | 19 (40) | 23 (37) | 0.72 |

| Myalgia | 82 (75) | 35 (74) | 47 (76) | 0.87 |

| Arthralgia | 46 (42) | 21 (45) | 25 (40) | 0.65 |

| Diarrhoea | 39 (36) | 13 (28) | 26 (42) | 0.12 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 73 (67) | 33 (70) | 40 (65) | 0.53 |

| Chest pain | 9 (8) | 3 (6) | 6 (10) | 0.73 |

| Dyspnoea | 16 (15) | 5 (11) | 11 (18) | 0.30 |

| Cough | 32 (29) | 9 (19) | 23 (37) | 0.04 |

| URTI symptoms | 15 (14) | 7 (15) | 8 (13) | 0.79 |

| Haemoptysis | 12 (11) | 0 | 12 (19) | 0.001 |

| Abnormal bleeding or bruising | 11 (10) | 4 (9) | 7 (11) | 0.75 |

| Objective examination findings | ||||

| Hepatomegaly | 11 (10) | 3 (6) | 8 (13) | 0.35 |

| Splenomegaly | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Lymphadenopathy | 6 (6) | 1 (2) | 5 (8) | 0.23 |

| Conjunctival suffusion | 22 (20) | 9 (19) | 13 (21) | 1.0 |

| Skin rash | 19 (17) | 8 (17) | 11 (18) | 1.0 |

| Abnormal chest auscultation | 44 (40) | 10 (21) | 34 (55) | <0.001 |

| Vital signs at presentation | ||||

| Oliguria b | 42 (39) | 12 (26) | 30 (48) | 0.02 |

| Temperature ° Celsius | 37.1 (36.8-37.6) | 37.2 (36.8-37.8) | 37.1 (36.8-37.6) | 0.62 |

| Supplemental oxygen given | 23 (21) | 3 (6) | 20 (32) | 0.001 |

| SpO2/FiO2 | 462 (450-471) | 467 (457-471) | 462 (296-467) | 0.008 |

| Respiratory rate | 20 (18-24) | 20 (18-24) | 20 (18-25) | 0.54 |

| Heart rate | 99 (80-115) | 97 (78-107) | 104 (83-116) | 0.24 |

| Systolic blood pressure c | 111 (100-124) | 111 (99-124) | 111 (104-124) | 0.40 |

| Vasopressors administered | 42 (39) | 11 (23) | 31 (50) | 0.005 |

| Impaired consciousness | 6 (6) | 0 | 6 (10) | 0.04 |

| Disease severity score | ||||

| SPiRO score d | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-1) | 2 (1-2) | 0.001 |

| All n=109 n (%) |

ICU admission n=56 Odds ratio (95% CI) |

p | Pulmonary haemorrhage n=26 Odds ratio (95% CI) |

p | Mechanical ventilation n=15 Odds ratio (95% CI) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multilobar changes | 50 (46) | 2.59 (1.19 - 5.54) | 0.02 | 26.31 (5.78 - 119.71) | <0.001 | 22.56 (2.84 - 178.92) | <0.001 |

| Alveolar changes | 54 (50) | 5.81 (2.55 - 13.27) | <0.001 | 21.20 (4.68 - 96.01) | <0.001 | 18.9 (2.39 - 149.71) | 0.005 |

| Only interstitial changes | 8 (7) | 0.29 (0.06 - 1.51) | 0.14 | 0.43 (0.05 - 3.79) | 0.45 | 0.89 (0.10 - 7.78) | 0.91 |

| No imaging changes | 47 (43) | 0.24 (0.11 - 0.54) | 0.001 | 0.03 (0.00 - 0.25) | 0.001 | - a | - a |

| All n=109 |

No lung involvement n=47 |

Lung involvement n=62 |

p | No pulmonary haemorrhage n=83 |

Pulmonary haemorrhage n=26 |

p | No mechanical ventilation n=94 |

Mechanical ventilation n=15 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to antibiotics (days) | 4 (3-5) | 3 (2-5) | 5 (4-6) | 0.001 | 4 (3-5) | 5 (4-6) | 0.10 | 4 (3-5) | 5 (4-6) | 0.12 |

| ICU admission | 56 (51) | 15 (32) | 41 (66) | <0.001 | 37 (45) | 19 (73) | 0.01 | 41 (44) | 15 (100) | <0.0001 |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 3 (2-5) | 1 (1-3) | 3 (2-6) | 0.002 | 2 (1-3) | 6 (3-11) | <0.0001 | 2 (1-3) | 9 (6-15) | <0.0001 |

| Received RRT | 18 (17) | 3 (6) | 15 (24) | 0.01 | 9 (11) | 9 (35) | 0.01 | 8 (9) | 10 (67) | <0.0001 |

| Received vasopressors | 56 (51) | 15 (32) | 41 (66) | <0.001 | 37 (45) | 19 (73) | 0.01 | 41 (44) | 15 (100) | <0.0001 |

| Steroids prescribed | 19 (17) | 3 (6) | 16 (26) | 0.01 | 8 (10) | 11 (42) | <0.0001 | 6 (6) | 13 (87) | <0.0001 |

| Received ECMO | 2 (2) | 0 | 2 (3) | 0.51 | 0 | 2 (8) | 0.06 | 0 | 2 (13) | 0.02 |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 6 (3-8) | 4 (3-6) | 7 (5-11) | <0.001 | 5 (3-7) | 7 (6-14) | <0.0001 | 5 (3-7) | 18 (10-21) | <0.0001 |

| Died | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).