Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cognitively Guided Instruction

2.2. Theoretical Basis of Cognitively Guided Instruction

2.3. CGI Classroom

2.4. CGI and Teachers

2.5. Conceptual Understanding

2.6. Mathematical Achievements

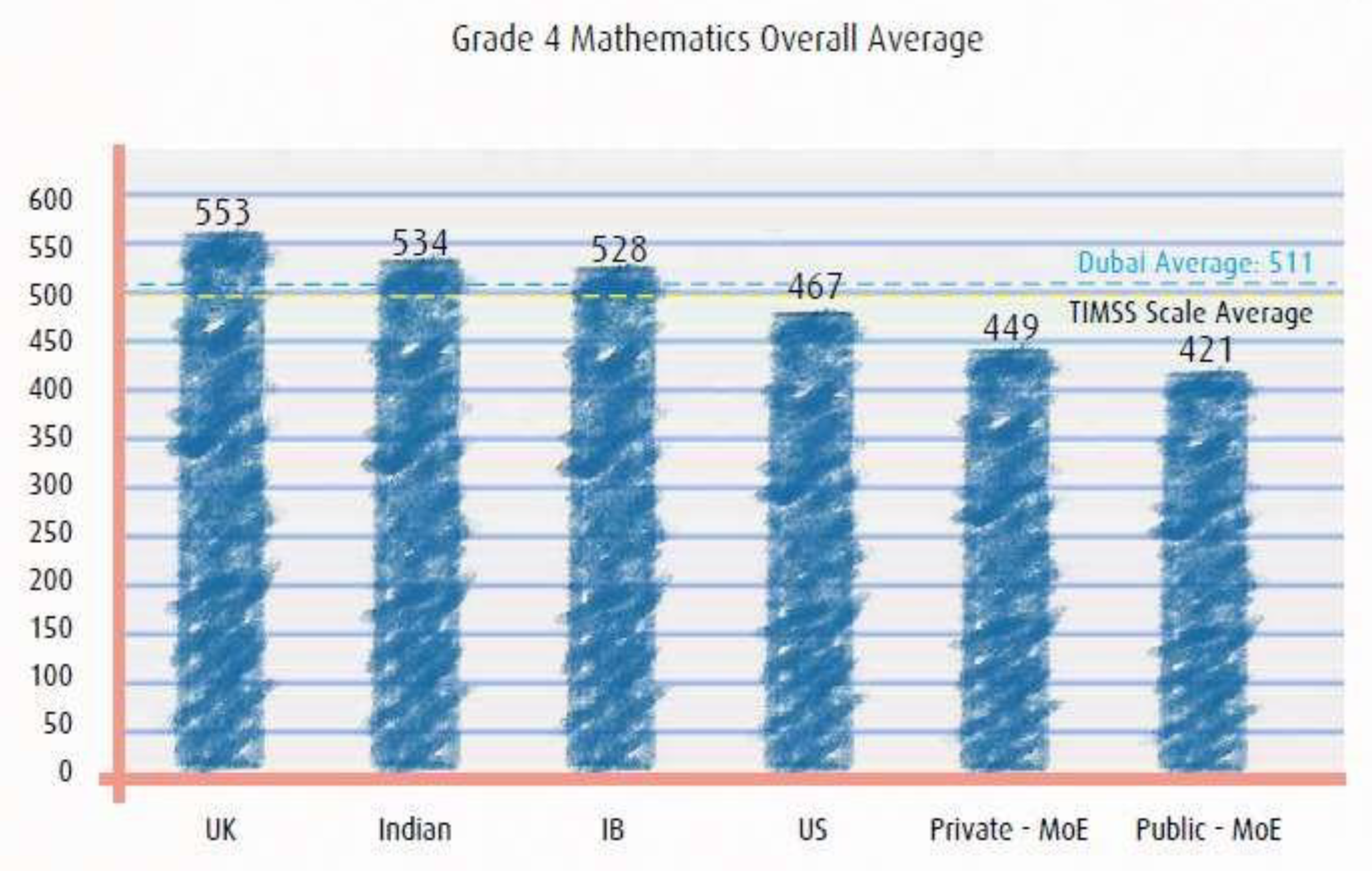

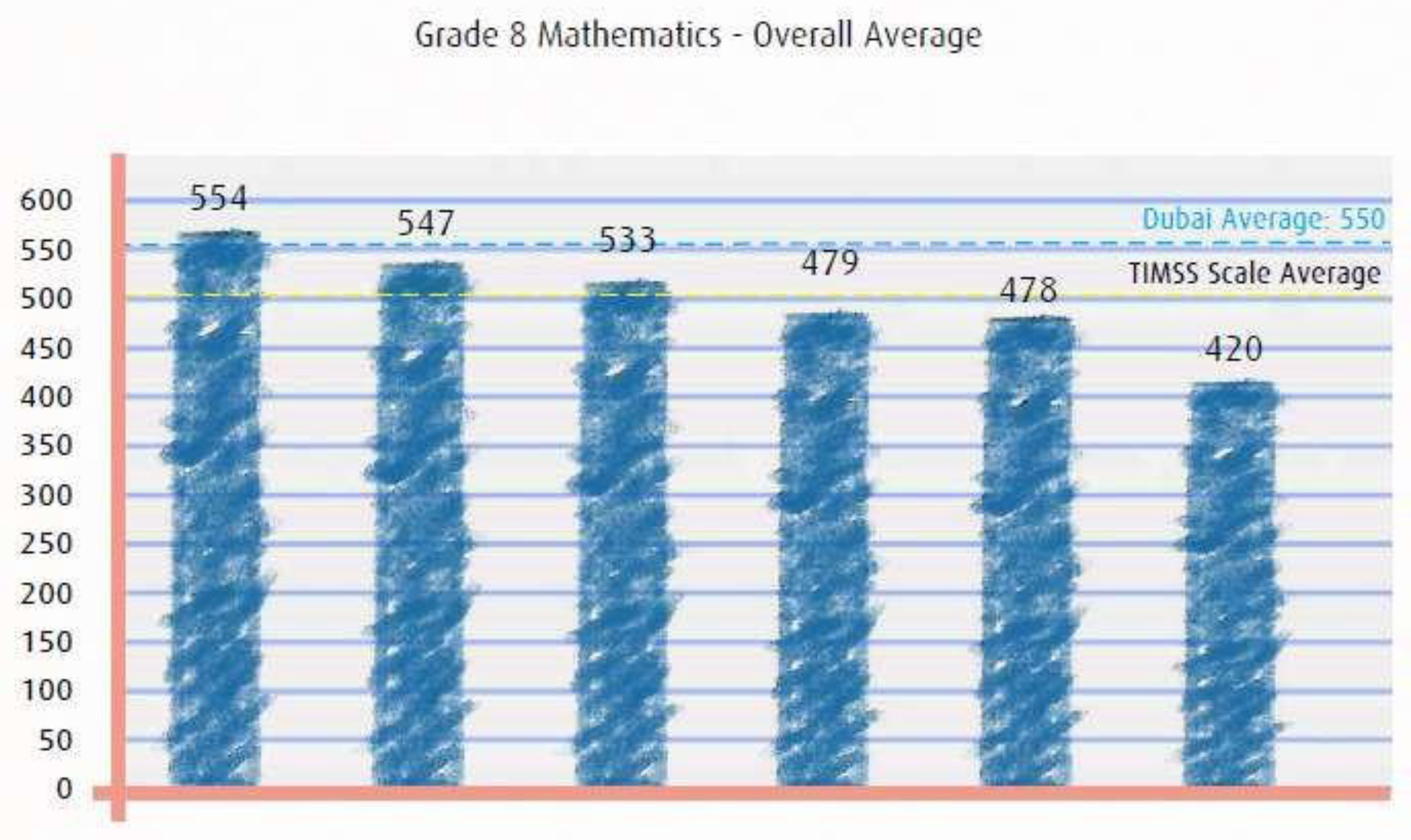

2.7. Potential Reasons for Low Achievements

2.8. The Effects of CGI on Students’ Conceptual Understanding

2.9. The Effects of Using CGI on Students’ Mathematical Achievements

2.10. CGI as a Strategy to Overcome Comprehension Problems to Improve Mathematical Achievements

2.11. CGI as a Strategy to Provide Students with Foundational Skills and Conceptual Knowledge to Improve Achievements

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design

3.2. The Population and Sample of the Study

3.3. Instrumentation

3.4. Pre-Test and Post-Test Assessment

- 1)

- Students’ ability to solve problems without being able to explain their work.

- 2)

- Students’ ability to solve problems and explain their thinking using any strategy, such as direct modeling, direct methods, or even invented strategies.

3.5. Direct Observations

3.6. Validity and Reliability

3.7. Data Collection Procedure

- 1)

- What is the effect of CGI practices on students’ mathematical achievements?

- 2)

- What is the effect of CGI practices on students’ conceptual understanding?

- 3)

- Can CGI practices help students overcome the challenges they face while solving mathematical problems?

3.8. Data Analysis Procedure

3.9. Analysis of the Pre-Test and Post-Test

- 1)

- The arithmetic means of the pre-tests for both the control and experimental groups were compared to validate the analysis. A significant difference between the pre-test means has the potential to influence the post-test results(Campbell & Stanley, 1963). This comparison was performed utilizing the two-sample t-test available in the Data Analysis add-ins of Microsoft Excel.

- 2)

- Analyzing the difference between the arithmetic means of the pre-test and post-test for the experimental group using the paired t-test tool, which is built into Microsoft Excel Data Analysis add-ins. This was done to check the significance of the change in the arithmetic mean after using CGI practices.

- 3)

- Comparing the arithmetic means of the post-tests between the experimental and control groups to check whether there is a significant difference between their means. This was performed using the two-sample t-test tool built into the Microsoft Excel Data Analysis add-ins.

3.10. Analysis of Direct Observation

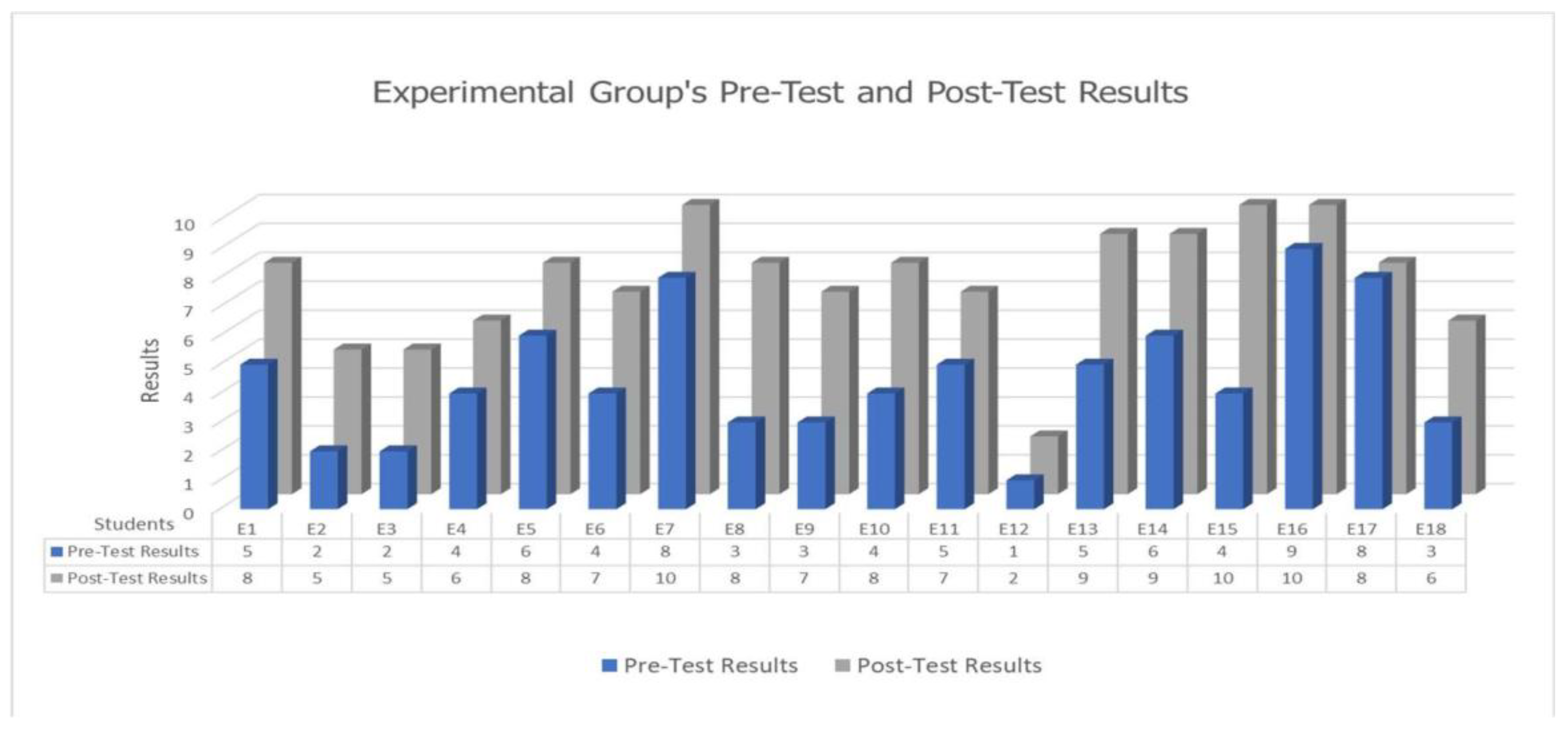

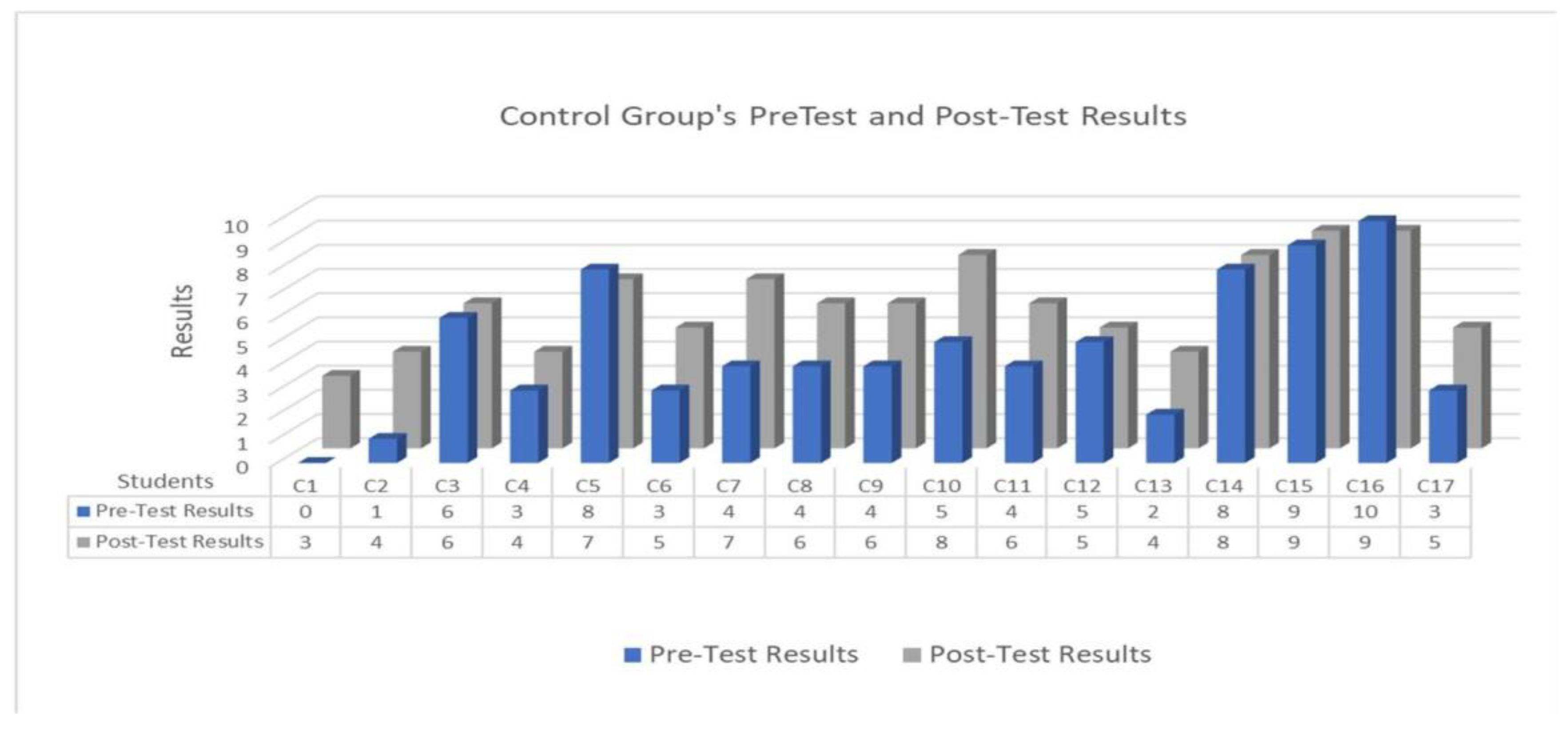

4. Results

4.1. Analysis and Results for the First Research Question

4.2. Comparing the Arithmetic Means of the Pre-Tests for the Control and Experimental Groups

4.3. Analysis and Results for the Second Question

4.4. Results of Part 2, Part 3, and the Unfamiliar Multiplication Sentences

4.5. Results of Direct Observations

4.6. Results of the First Observation

4.7. Results of the Second Observation

4.8. Analysis and Results for the Final Research Question

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

6.1. Conceptual Understanding and Mathematical Achievement

6.2. Integration of Mathematical Ideas and Problem-Solving

6.3. Addressing Challenges in Learning Mathematics

6.4. Enhancing Engagement and Collaboration

6.5. Broader Implications for Educational Practice

7. Recommendations

7.1. Expanding CGI Research Across Mathematical Operations

7.2. Exploring CGI’s Influence on Mathematical Beliefs and Attitudes

7.3. Investigating CGI Across All Elementary Grades

7.4. Increasing Sample Size and Diversity

7.5. Extending the Duration of CGI Implementation

7.6. Addressing Educator Perspectives and Professional Development

7.7. Informing Educational Practices and Policies

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdallah, A. K., and M. B. Musah. 2021. Effects of teacher licensing on educators’ professionalism: UAE case in local perception. Heliyon 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroody, A. J. B. A. 2001. Early Childhood Corner. Early Number Instruction 8, 3: 154–158. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, T. E. 2017. The Effects of Cognitively Guided Instruction and Cognitively Based Assessment on Pre-Service Teachers. Thesis, Ohio Dominican University. [Google Scholar]

- Bognar, B., S. M. Horvat, and L. J. Matic. 2025. Characteristics of Effective Elementary Mathematics Instruction_ A Scoping Review of Experimental Studies _ Enhanced Reader. Education Sciences. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D. T., and J. Stanley. 1963. Experimental and Quasi-experimental Designs for Research on Teaching. Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, T. P. 1999. Children’s mathematics: Cognitively guided instruction. Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, T. P., E. Fennema, M. L. Franke, L. Levi, and S. B. Empson. 1996. Children’s mathematics: Cognitively guided instruction. Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, T. P., E. Fennema, M. L. Franke, L. Levi, and S. B. Empson. 2014. Children’s Mathematics: Cognitively Guided Instruction, 2nd ed. Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, T. P., E. Fennema, P. L. Peterson, C.-P. Chiang, and M. Loef. 1989. Using Knowledge of Children’s Mathematics Thinking in Classroom Teaching: An Experimental Study. American Educational Research Journal 26, 4: 499–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, T. P., M. L. Franke, and L. Levi. 2003. Thinking Mathematically: Integrating Arithmetic & Algebra in Elementary School. Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, S. K., W. W. L. Chan, and R. W. Fong. 2024. Mechanisms underlying the relations between parents’ perfectionistic tendencies and young children’s mathematical abilities. British Journal of Educational Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, D. H., and J. Sarama. 2011. Early Childhood Mathematics Intervention. Science 333, 6045: 968–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Common Core State Standards Ini. 2019. Common Core State Standards for Mathematics. Common Core State Standards Initiative: Available online: https://ccsso.org/resource-library/ada-compliant-math-standards.

- Creswell, John W., and J. David Creswell. 2018. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., and V. L. P. Clark. 2019. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Decristan, J., A. L. Hondrich, G. Büttner, S. Hertel, E. Klieme, M. Kunter, A. Lühken, K. Adl-Amini, S.-K. Djakovic, S. Mannel, A. Naumann, and I. Hardy. 2015. Impact of Additional Guidance in Science Education on Primary Students’ Conceptual Understanding. The Journal of Educational Research 108, 5: 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogbey, J. 2025. Supporting elementary school teachers enhance their mathematics instruction through invented strategies and classroom discourse. Asian Journal for Mathematics Education 4, 1: 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, C. G. 1995. Methods for Direct Observation of Performance. In Evolution of human work; a practical ergonomics methodology. Edited by R. Wilson and E. N. Corlett. Taylor and Francis: pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds, W. A., and T. D. Kennedy. 2017. An Applied Guide to Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Egara, F. O., and M. Mosimege. 2024. Effect of flipped classroom learning approach on mathematics achievement and interest among secondary school students. Education and Information Technologies 29, 7: 8131–8150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empson, S. B. 2015. What Does a CGI Classroom Look Like? An introduction to cognitively guided instruction. Professional Development. Available online: https://cdnsm5-ss16.sharpschool.com/UserFiles/Servers/Server_27053187/File/Curriculum/Math%20Cognitively%20Guided%20Instruction/Home%20Page/What%20Does%20a%20CGI%20Classroom%20Look%20like_.pdf.

- Fennema, E., T. P. Carpenter, M. L. Franke, L. Levi, V. R. Jacobs, and S. B. Empson. 1996. A Longitudinal Study of Learning to Use Children’s Thinking in Mathematics Instruction. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education 27, 4: 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, M. L., N. M. Webb, A. G. Chan, M. Ing, D. Freund, and D. Battey. 2009. Teacher questioning to elicit students’ mathematical thinking in elementary school classrooms. Journal of Teacher Education 60, 4: 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funa, A. A., J. D. Ricafort, F. G. J. Jetomo, and N. L. Lasala, Jr. 2024. Effectiveness of Brain-Based Learning Toward Improving Students’ Conceptual Understanding: A Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Instruction 17, 1: 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyfe, E. R., M. S. DeCaro, and B. Rittle-Johnson. 2014. An alternative time for telling: When conceptual instruction prior to problem solving improves mathematical knowledge. British Journal of Educational Psychology 84, 3: 502–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokulan, D. 2018. Education in the UAE: Then, now and tomorrow. Alkhaleej Times. May 15. Available online: https://www.khaleejtimes.com/uae/education-in-the-uae-then-now-and-tomorrow.

- Gunasekare, U. L. T. P. 2015. Mixed Research Method as the Third Research Paradigm: A Literature Review. International Journal of Science and Research 4, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Hayati, R., Asmayanti, and W. Prima. 2024. Revitalizing Math Education: Unveiling the Impact of Holistic Mathematics Education Based “Sistem Among” in Elementary Classrooms. Al - Ishlah: Jurnal Pendidikan 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayatullah, A., and C. Csíkos. 2023. Exploring Students’ Mathematical Beliefs: Gender, Grade, and Culture Differences. Journal on Efficiency and Responsibility in Education and Science 16, 3: 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., P. Wouters, M. van der Schaaf, and L. Kester. 2024. The effects of achievement goal instructions in game-based learning on students’ achievement goals, performance, and achievement emotions. Learning and Instruction 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H., S. Osman, and A. H. Abdullah. 2024. Exploring the Roots of Poor Mathematics Performance: A Stakeholder Perspective in Adamawa State, Nigeria. International Journal of Education 16, 1: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illa, T. O. A., H. Mondoh, and J. Kwena. 2019. Effect of Cognitively Guided Instruction on Primary School Teachers’ Perceptions of Learners’ Conceptual Understanding of Mathematics: Mombasa County, Kenya. International Journal of Education and Research 7, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, V. R., M. L. Franke, T. P. Carpenter, L. Levi, and D. Battey. 2001. Professional development focused on children’s algebraic reasoning in elementary school. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education 38, 3: 258–288. [Google Scholar]

- Jadeja, R. 2019. External Benchmarks Tests CAT4, MAP, CPAA and UAE National Agenda Priorities. February 16. [Google Scholar]

- Jamil, M., T. Batool Bokhari, and J. Iqbal. 2024. Incorporation of Critical Thinking Skills Development: A Case of Mathematics Curriculum for Grades I-XII. Journal of Asian Development Studies 13, 1: 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamii, C., and J. Rummelsburg. 2008. Arithmetic for First Graders Lacking Number Concepts. Teaching Children Mathematics 14, 7: 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanive, R., P. M. Nelson, M. K. Burns, and J. Ysseldyke. 2014. Comparison of the effects of computer-based practice and conceptual understanding interventions on mathematics fact retention and generalization. Journal of Educational Research 107, 2: 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowledge and Human Development Authority. 2017. Dubai TIMSS 2015. Available online: https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2015/encyclopedia/benchmarking-participants/dubai-uae/.

- Lavrakas, P. J. 2008. Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods. SAGE Research Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, J. 2019. Making maths fun, easy. Gulf News. February 16. Available online: https://gulfnews.com/uae/education/making-maths-fun-easy-1.60650019.

- Li, P. H., D. Mayer, and L. E. Malmberg. 2024. Student engagement and teacher emotions in student-teacher dyads: The role of teacher involvement. Learning and Instruction 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machaba, F., and C. Mangwiro. 2024. Teacher Follow-up on Learners’ Initial Response to Teacher Questions. African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 28, 1: 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M. S. bin, and A. Y. bin Mustafa Bakri. 2024. The Integration of Robotics in Mathematics Education: A Systematic Literature Review Type of the Research: Review Article. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. 2019. UAE School Inspection Framework. UAE Ministry of Education. Available online: https://web.khda.gov.ae/en/Resources/Publications/School-Inspection/UAE-School-Inspection-Framework-2015-16.

- Moore, S., and J. A. Cuevas. 2022. The effects of cognitively guided phonetic instruction on achievement and self-efficacy in elementary students in a response to intervention program. Journal of Pedagogical Research 6, 4: 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munday, K. S. 2016. Effectiveness of Cognitively Guided instruction Practices in Below Grade-Level Elementary Students [Hamline University]. Available online: https://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/hse_all/4249.

- National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, C. C. S. S. O. 2010. Common Core State Standards for Mathematics. Education Resources Information Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Okanda, P., C. Olemo, and K. Akumu. 2023. Impact, Successes, Challenges and Recommendations: A Multinational e-Learning Partnership and Initiative. Authorea 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, B. 2017. A study of mathematical achievement of secondary school students. International Journal of Advanced Research 5, 12: 1951–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, C., and J. Wren. 2007. Exploring Reliability in Academic Assessment. Available online: https://www.uni.edu/chfasoa/reliabilityandvalidity.htm.

- Piaget, J. 1970. Science of Education and the Psychology of the Child. Orion Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaila, S. 2025. Cognitively guided instruction in education: a review of research trends and classroom applications. Cogent Education 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saparbayeva, E., M. Abdualiyeva, Y. Torebek, N. Madiyarov, and A. Tursynbayev. 2024. Leveraging digital tools to advance mathematics competencies among construction students. Cogent Education 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, R. C., C. Rhoads, A. L. Perez, A. M. Tazaz, and W. G. Secada. 2022. Impact of Cognitively Guided Instruction on Elementary School Mathematics Achievement: Five Years After the Initial Opportunity. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, R., W. Bray, C. Riddell, C. Buntin, N. Iuhasz-Velez, W. Secada, and E. Yujia Li. 2024. Looking Inside the Black Box: Measuring Implementation and Detecting Group-Level Impact of Cognitively Guided Instruction. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education 55, 4: 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schukajlow, S., G. Kaiser, and G. Stillman. 2023. Modeling from a cognitive perspective: theoretical considerations and empirical contributions. Mathematical Thinking and Learning 25, 3: 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U., and R. Bougie. 2016. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach, 7th ed. Willey. [Google Scholar]

- Shone, E. T., F. M. Weldemeskel, and B. N. Worku. 2024. The role of students’ mathematics perception and self-efficacy toward their mathematics achievement. Psychology in the Schools 61, 1: 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siller, H. S., and S. Ahmad. 2024. Analyzing the impact of collaborative learning approach on grade six students’ mathematics achievement and attitude towards mathemat. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The United Arab Emirates’ Government portal. 2018. Raising the standard of education. Retrieved from The United Arab Emirates’ Government porta. December 17. Available online: https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/leaving-no-one-behind/4qualityeducation/raising-the-standard-of-education.

- Vista, A. 2013. The role of reading comprehension in maths achievement growth: Investigating the magnitude and mechanism of the mediating effect on maths achievement in Australian classrooms. International Journal of Educational Research 62: 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C., W. G. Secada, and H. Ran. 2025. The effects of cognitively guided instruction on how teachers support the development of student agency. Discover Education 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, N. M., M. L. Franke, M. Ing, A. Chan, T. De, D. Freund, and D. Battey. 2008. The role of teacher instructional practices in student collaboration. Contemporary Educational Psychology 33, 3: 360–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, K. A., A. Renkl, A. Eitel, and I. Glogger-Frey. 2024. Digital re-attributional feedback in high school mathematics education and its effect on motivation and achievement. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 40, 2: 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, T. T., W. Hidayat, N. Hermita, J. A. Alim, and C. A. Talib. 2024. Exploring contributing factors to PISA 2022 mathematics achievement: insights from Indonesian teachers. Infinity Journal 13, 1: 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S. M., and J. Berne. 1999. Teacher Learning and the Acquisition of Professional Knowledge: An Examination of Research on Contemporary Professional Development. Source: Review of Research in Education 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wistrom, E. 2011. An Introduction to Teaching Cognitively Guided Instruction Math to Your Students. Available online: https://www.brighthubeducation.com/lesson-plans-grades-3-5/6935-introduction-tocognitively-guided-instruction-math/#comment-333894878.

- Zhang, Y., T. Li, J. Xu, S. Chen, L. Lu, and L. Wang. 2024. More homework improve mathematics achievement? Differential effects of homework time on different facets of students’ mathematics achievement: A longitudinal study in China. British Journal of Educational Psychology 94, 1: 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H., J. Zhang, H. Li, B. Huang, H. Feng, C. Liu, and J. Si. 2024. Independent and joint effects of perceived teacher support and math self-efficacy on math achievement in primary school student: Variable-oriented and person-oriented analyses. Learning and Individual Differences 112: 102445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Students | Frequency | Percent |

| Total number of students in both the control group and experimental group | 35 | 100% |

| Total number of female students | 17 | 49% |

| Total number of male students | 18 | 51% |

| Total number of English learning students | 33 | 94% |

| Total number of SEND students | 2 | 0.05% |

| Total number of Emirati students | 12 | 34% |

| Multiplication Sentence | Frequency |

| Multiplication sentence that can be solved using existing knowledge | 3 |

| Multiplication sentence that can be solved using strategies that will be taught during the period of the study | 2 |

| Multiplication sentences that will not be taught during the period of the study | 1 |

| Question | Data Resource | Week addressed |

| What is the effect of CGI practices on students’ mathematical achievements? |

1) Pre-test results | First day of the First week of the study |

| 2) Post-test results | Fifth day of the sixth week of the study | |

| What is the effect of CGI practices on students’ conceptual understanding? |

1) Pre-test (Part two and part 3 of the test unfamiliar multiplication sentence) | First day of the First week of the study |

| 2) First Observation | Second week of the Study | |

| 3) Second Observation | Fifth week of the Study | |

| 4) Post-test (Part two and part 3 of the test and unfamiliar multiplication sentence) | Fifth day of the sixth week of the study | |

| Can CGI practices help students to overcome the challenges that they face while solving mathematical problems? | 1) Second Observation | Fifth week of the Study |

| t-Test: Two-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances | ||

| Exp-PRE-TEST | Con-PRE-TET | |

| Mean | 4.555555556 | 4.647058824 |

| Observations | 18 | 17 |

| Hypothesized Mean Difference | 0 | |

| P(T<=t) one-tail | 0.457564124 | |

| P(T<=t) two-tail | 0.915128248 | |

| t-Test: Paired Two Sample for Means | ||

| PRE-TEST | POST-TETS | |

| Mean | 4.555555556 | 7.388888889 |

| Observations | 18 | 18 |

| Hypothesized Mean Difference | 0 | |

| P(T<=t) one-tail | 1.29365E-07 | |

| P(T<=t) two-tail | 2.5873E-07 |

| t-Test: Two-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances | ||

| Exp- POST-TETS | Con- POST-TETS | |

| Mean | 7.388888889 | 6.00 |

| Observations | 18 | 17 |

| Hypothesized Mean Difference | 0 | |

| P(T<=t) one-tail | 0.020602783 | |

| P(T<=t) two-tail | 0.041205566 |

| Criteria | Number of Students Answering before CGI | Number of Students Answering After CGI |

Change |

| Ability to solve part two (story problems) without explaining. | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| Ability to solve part two (story problems) with explaining using direct modeling or any other strategy. | 6 | 13 | 7 |

| Ability to solve part three (multi-step problems) without explaining. | 3 | 7 | 4 |

| Ability to solve part three (multi-step problems) with explaining using direct modeling or any other strategy. | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Ability to solve unfamiliar multiplication sentences. | 2 | 5 | 3 |

| Control group | |||

| Criteria | Number of Students Answering before Traditional Instruction |

Number of Students Answering after Traditional Instruction |

Change |

| Ability to solve part two (story problems) without explaining. | 4 | 7 | 3 |

| Ability to solve part two (story problems) with explaining using direct modeling or any other strategy. | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| Ability to solve part three (multi-step problems) without explaining. | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| Ability to solve part three (multi-step problems) with explaining using direct modeling or other strategies. | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ability to solve unfamiliar multiplication sentences. | 2 | 1 | -1 |

| Criteria | Increment of the students after CGI in the Experimental Group |

Increment of the Students after Traditional Teaching in the Control group |

| Ability to solve part two (story problems) without explaining. | 1 | 3 |

| Ability to solve part two (story problems) with explaining using direct modeling other strategies. | 7 | 0 |

| Ability to solve part three (multi-step problems) without explaining. | 4 | 2 |

| Ability to solve part three (multi-step problems) with explaining using direct modeling or other strategies. | 3 | 0 |

| Ability to solve unfamiliar multiplication sentences. | 2 | -1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).