1. Introduction

Globally, changing population dynamics have led to an unprecedented increase in the ageing population over the last few decades. According to estimates by the World Health Organization (WHO), the proportion of the global population aged 60 years and older is projected to rise from 12% in 2015 to 22% by 2050, posing substantial challenges to healthcare systems worldwide [

1]. In India, the elderly population is projected to triple by mid-century, emphasizing the urgent need for efficient strategies to manage age-related conditions and improve the quality of life for this vulnerable group [

2].

Frailty, a common geriatric syndrome, is one such condition that presents a significant challenge for healthcare systems. It is characterised by a decline in functional reserve in various organ systems and increased vulnerability to stressors that lead to higher risks of adverse outcomes like falls, disability, dependency, hospitalisations, and mortality [

3]. There is also an intermediate stage termed

pre-frailty, which, like frailty, is associated with adverse health outcomes [

4].

The prevalence of frailty varies globally, ranging from 12% to 24%, while pre-frailty is more common, with a prevalence of 46%, as reported in a systematic review covering 62 countries. Frailty and pre-frailty are generally more prevalent among older women compared to men [

5]. In a recent meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of frailty and pre-frailty among older adults aged 60 years or more in India was found to be 38.18% and 45.14%, respectively [

6]. Frailty prevalence was found to be increased with age, with rates of 4% among individuals aged 65–69 years, rising to 26% among those aged 85 years and older [

7]. In India, the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) Wave 1 data revealed an overall frailty prevalence of 55% among adults aged 50 years and older, with West Bengal exhibiting the highest prevalence at nearly 67% [

8]. In a prospective cohort study of 10 years involving community-dwelling older people, the most common condition leading to death was found to be frailty (27.9%), which is even more than organ failure (21.4%), cancer (19.3%), dementia (13.8%) and other causes (14.9%) [

9].

Frailty exists in a dynamic continuum, from robust to pre-frail to frail. Thus, it offers the potential to reverse health conditions to a non-frail or robust stage through timely identification and effective intervention measures. Several tools have been developed to assess frailty, each with varying degrees of complexity and focus. The most commonly used instruments in literature are Fried’s Physical Frailty Phenotype, which is based on unintentional weight loss, self-reported reduced energy level, decreased grip strength, slowed gait speed, and low level of physical activity [

10], and Rockwood’s Frailty Index that measures frailty based on the accumulation of deficits [

11]. However, culturally relevant, simple, and easily administered frailty assessment tools remain scarce in low- and middle-income countries like India. The Frailty Assessment and Screening Tool (FAST) are a concise, multi-dimensional instrument developed and validated specifically for the Indian population. FAST evaluates frailty across domains such as nutrition, memory, mobility, functional status, mood, physical performance, general health, medication use, multi-morbidity, continence, and pain [

4].

India has a highly diverse population, both socially and linguistically. Thus, cultural and linguistic adaptations are essential to ensure the effectiveness of the FAST questionnaire across such diversity. For example, no validated Bengali version of the FAST questionnaire is currently available, limiting its applicability in states like West Bengal, where a significant proportion of the population primarily speaks Bengali. This gap hinders the reliable assessment of frailty for this demographic, especially in community settings. Considering the distinct sociocultural and linguistic characteristics of the Bengali-speaking population, there is an urgent need to adapt and validate the FAST questionnaire in the Bengali language. This will facilitate appropriate screening and enable healthcare providers to identify at-risk older adults more effectively. In this context, the study was conducted to assess the reliability and validity of the Bengali version of the Frailty Assessment and Screening Tool (FAST) among older adults (≥ 60 years) in Kolkata, India.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study is part of a large project funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, to develop a frailty management model for community-dwelling older adults aged ≥ 60 years in India. The study was conducted by the Indian Council of Medical Research – Centre for Ageing and Mental Health (now ICMR-National Institute for Research in Bacterial Infections), Kolkata, West Bengal, India, from April 2025 to September 2025. The present study employed a cross-sectional design to evaluate the reliability and validity of the Bengali version of the Frailty Assessment and Screening Tool (FAST) for assessing frailty among older adults.

2.2. Study Setting and Participants

The present study was conducted among community-dwelling older adults in their settings residing in Ward numbers 57 and 58 of the Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC), West Bengal, India. The required sample size was estimated using the

10-item, which recommends recruiting at least 10 participants per item in the scale [

12,

13]. As the FAST questionnaire consisted of 14 items, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be 140 participants. Allowing for a 20% anticipated dropout rate, the final target sample size was increased to 168. Finally, 217 participants were included in the study. A systematic random sampling technique was adopted to recruit the participants from the sampling frame. Eligible participants included both males and females aged 60 years or above in the community setting who consented to participation in the study. Individuals with severe cognitive or psychological impairments, as well as those with significant physical disabilities, were excluded from the study.

2.3. Data Collection

For this study, the English version of the FAST questionnaire underwent a rigorous translation process. First, it was translated into Bengali by an independent bilingual expert unaffiliated with the research team. To ensure linguistic accuracy and conceptual equivalence, another expert, also independent of the study team, performed a back-translation of the Bengali version into English. The research team then systematically reviewed and compared the original English version with the back-translated version to identify and resolve any discrepancies [

14]. Based on this process, the final Bengali version of the FAST questionnaire was prepared for use in the study. The questionnaire comprised 14 items with dichotomous response options (“yes” or “no”). A response of “yes” was scored as 1, while “no” was scored as 0. The total FAST score was used to classify participants, with a cut-off score of ≥7 indicating frailty, ≥5 indicating pre-frailty, and <5 indicating robust or free from any frailty symptom [

15]. In addition to FAST, participants were also assessed for frailty and pre-frailty by the Fried Frailty Phenotype, which served as the gold standard in this study [

16]. In Fried Frailty Phenotype, the participants were evaluated based on five criteria: (i) unintentional weight loss, (ii) self-reported reduced energy level, (iii) reduced grip strength, (iv) slowed gait speed and (v) low level of physical activity. The presence of 3 or more of the above-stated criteria denoted frailty, 1–2 criteria denoted pre-frail condition, and the absence of any criterion denoted robust state for Fried Frailty Phenotype [

16,

17].

Initially, participants were surveyed to obtain demographic information such as age, gender, educational status, occupational status, monthly family income, socio-economic status, household size, and marital status (living with spouse). In addition, clinical history was recorded, which included associated diseases, medication use, and polypharmacy. Anthropometric measurements, including standing height and body weight, were obtained using standard procedures. Body Mass Index (BMI) was subsequently calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m²) and classified as underweight (<18.5 kg/m²), normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m²), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m²) and obese (≥30.0 kg/m²) [

18].

2.4. Ethical Clearance

The Institutional Ethics Committee approved the study (19th IEC/CAM/1.5 dated 03-12-2024), and the study was also registered in CTRI (CTRI/2025/01/079470). Prior to data collection, informed written consent was obtained from each participant. The questionnaire was administered to each participant by trained project staff, and privacy & confidentiality were maintained.

2.5. Operational Definition

Fried’s frailty criteria was considered the gold standard in the present manuscript. Criteria of frailty and pre-frailty depended on the presence of five criteria in an individual: (i) unintentional weight loss, (ii) self-reported reduced energy level, (iii) reduced grip strength, (iv) slowed gait speed, and (v) low level of physical activity. The presence of 3 or more of the above-stated criteria denoted frailty, and 1–2 criteria denoted a pre-frail condition [

17]. The FAST scale was tested against this gold standard test. The FAST scale had 14 criteria. FAST scores had a cut-off of ≥7/14 for frail and ≥5/14 for pre-frail elderly [

15].

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Descriptive Statistics

The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants were summarised using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, while means and standard deviations (SD) were reported for continuous variables.

2.6.2. Reliability Testing

The internal consistency of the FAST questionnaire was assessed in the overall sample using Cronbach’s alpha, with values above 0.70 considered acceptable [

19]. For reliability testing, both inter-rater and intra-rater reliability were examined. Inter-rater reliability was evaluated in a sub-sample of 20 older adults, independently assessed by two raters. Intra-rater reliability was measured in a sub-sample of 17 older adults, assessed at two different time points one month apart. Intra-class Correlation Coefficients (ICC) were calculated for both inter- and intra-rater reliability, with values greater than 0.75 indicating good stability [

20]. Additionally, Cohen’s Kappa coefficient (κ) was computed to assess the level of agreement between the two raters, beyond that expected by chance. A kappa (κ) value approaching +1 was considered as strong agreement [

19].

2.6.3. Construct Validity

A single factor Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) model was hypothesized based on the FAST questionnaire to test the construct validity. Here, the ‘latent construct’ (interchangeably used as ‘dimension’ or ‘factor’) was

frailty, and all the items of the questionnaire were loaded against this construct. Considering the dichotomous response format of the items, the Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimation method was applied. Prior to fitting the CFA model, multicollinearity was checked using the variance inflation factor (VIF). The analysis shows that VIF values ranging from 1.2 to 2.3, which were below the recommended threshold (VIF > 5), indicating no multicollinearity concerns [

21]. Model fit was evaluated using multiple indices, including Chi-square statistic (χ²), CMIN/DF, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). The criteria for acceptable model fit were: a lower χ² statistic, CMIN/DF ≤ 5, CFI ≥ 0.90, TLI ≥ 0.90, SRMR ≤ 0.08, and RMSEA ≤ 0.08 [

22]. Items with standardized factor loadings (λ) ≥ 0.40 were considered acceptable [

23]. Further, construct validity and reliability were evaluated using Ordinal Cronbach’s alpha (based on tetrachoric correlations), Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). The required thresholds were: Ordinal Cronbach’s alpha ≥ 0.70, CR ≥ 0.70, and AVE ≥ 0.50 [

24].

2.6.4. Criterion Validity

To evaluate the criterion validity of the FAST Bengali version against the Fried Frailty Scale (gold standard), Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed. The ROC curve allowed estimation of the Area Under the Curve (AUC), which provides a measure of the overall discriminative ability of the FAST in distinguishing frail from robust individuals. In addition, sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (true negative rate) were calculated to assess the accuracy of the scale [

15,

19].

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 24.0, while Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted in R software (version 4.5.1). For all analyses, a 95% confidence interval (CI) was applied, and a p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Table 1 describes the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants. The mean age was 64.27 ± 5.02 years, with the majority aged between 60 to 69 years (82.9%), and most were females (67.3%). Nearly all of the participants were Hindu (98.2%), and 61.3% were non-literate. Home makers (30.4%), retired (26.3%), and self-employed (25.8%) formed the largest occupational groups. Most of the participants (36.45%) belonged to middle socio-economic status (INR 2824–4706). Nearly 41.5% of the older participants lived with their spouse, the most commonly reported cause of not living with spouses was due to widowhood (47.5%). Associated diseases were reported by 74.2% of participants, and 71.0% consumed at least one medicine daily. The mean weight and height were 53.18 ± 11.96 kg and 1.51 ± 0.08 m, respectively. The majority of participants had a normal Body Mass Index (BMI) (51.6%), followed by 26.3% who were classified as overweight.

Table 2 presents the reliability statistics of the Bengali version of the FAST scale. The internal consistency was good, with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.806. The test–retest reliability demonstrated strong intra-rater agreement (ICC = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.623–0.945, p < 0.001). Additionally, inter-rater reliability was also acceptable (ICC = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.507–0.927, p < 0.001), and the Cohen’s kappa coefficient indicated substantial agreement (κ = 0.602, p < 0.001) among the two raters.

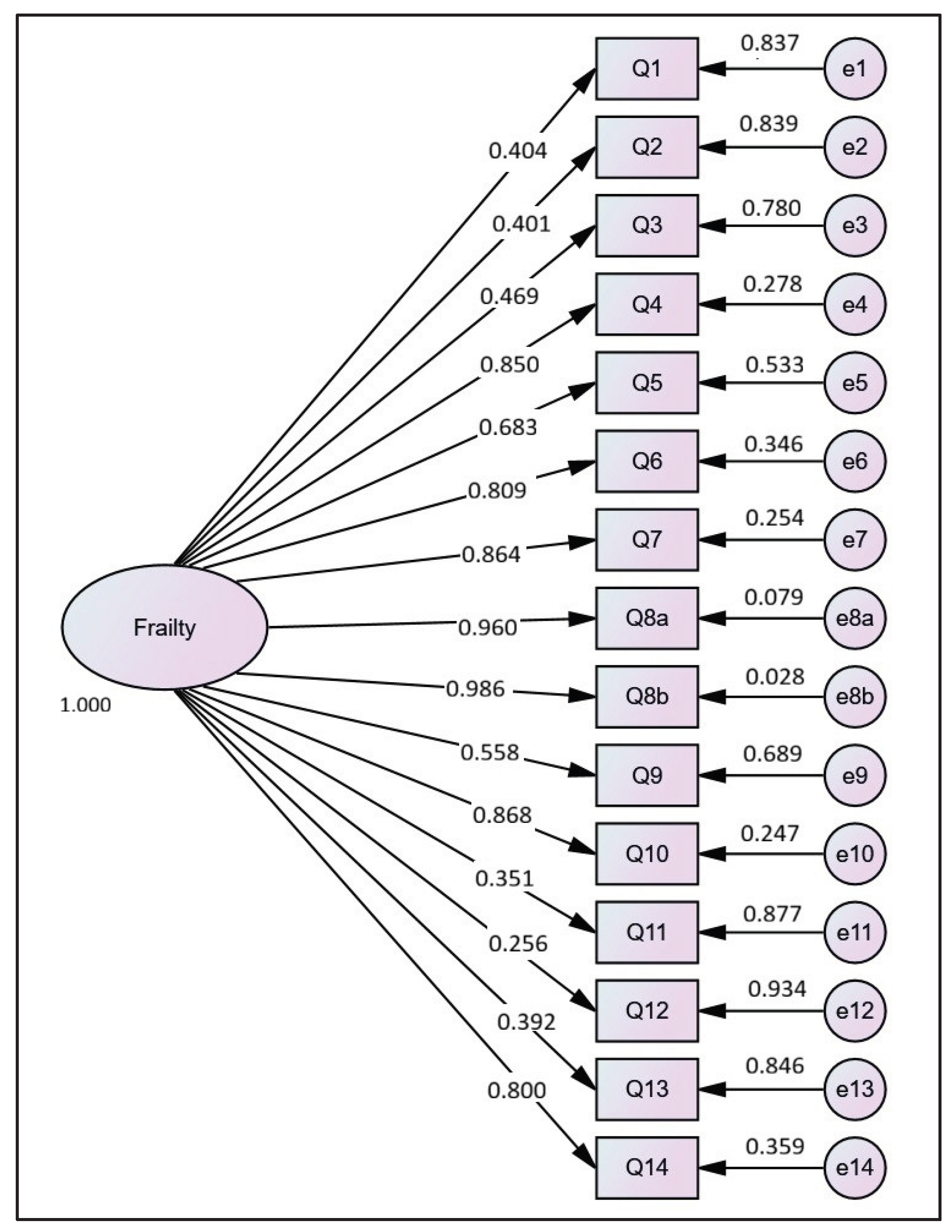

Table 3a shows the result of CFA of the items in the Bengali version of the FAST under the latent construct of frailty. It was found that the factor loadings ranged from 0.256 (Q12) to 0.986 (Q8b), with most items demonstrating strong and statistically significant loadings (

p < 0.05), indicating good association with the latent factor. Notably, items Q8a (λ = 0.960) and Q8b (λ = 0.986) showed the highest loadings. The items Q13 (λ = 0.392), Q12 (λ = 0.256) and Q11 (λ = 0.351) loaded relatively lower on the factor, though these questions were retained in the questionnaire as were clinically relevant.

Figure 1 illustrates the path diagram of the Bengali version of the FAST scale, showing standardized factor loadings of each item onto the latent frailty construct. The threshold values (τ) varied across items, reflecting some items (such as Q2, Q4, Q6) were endorsed even at comparatively low frailty levels, while others (such as Q9, Q11) were endorsed only at comparatively high frailty levels. This spread suggests that the FAST Bengali version was well-calibrated to differentiate participants across the full range of frailty severity. Overall, the findings support the factorial validity of the Bengali FAST scale.

Table 3b presents the model fit indices and psychometric validity of the FAST Bengali version. The model fit indices demonstrated an acceptable fit, with CFI (0.966) and TLI (0.960) exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.95, indicating a good comparative and incremental fit. The chi-square statistic was also significant (χ² = 449.19, df = 90, p < 0.001), while the CMIN/df ratio (4.99) fell within the acceptable range. However, the SRMR (0.157) and RMSEA (0.130, 95% CI: 0.118–0.143) were above conventional standards, suggesting some degree of model misfit. Reliability analysis showed strong internal consistency with ordinal alpha (0.898) and composite reliability (0.942) exceeding recommended values. The Average Variance Extracted (0.472) was marginally below the threshold, although it indicated acceptable convergent validity given the high factor loadings observed.

Table 4 summarizes the diagnostic accuracy of the FAST Bengali Version against the Fried Frailty Scale as the gold standard. The FAST scale demonstrated good sensitivity (0.810) that ndicates correct identification of the majority of frail individuals. The ROC curve analysis showed that the FAST scale had good overall discriminatory ability, with an AUC of 0.843 (p = 0.002, 95% CI: 0.755–0.930).

4. Discussion

Frailty has increasingly been recognized as a major public health concern globally in recent decades due to its strong association with functional dependence, falls, disability and frequent coexistence with multimorbidity among older adults. This situation is even more concerning in developing countries like India, where the ageing population is expanding rapidly, yet the available resources and healthcare infrastructure have not evolved proportionately to meet the growing needs. A systematic review encompassing frailty related studies from India have reported that the prevalence of frailty is the highest among hospitalized older adults (44.99%), followed by those attending geriatric centres (37.65%) and community-dwelling elderly (34.16%). Older adults with chronic diseases also face a considerably higher risk of frailty (40.83%), underscoring the importance of routine frailty screening in this group [

6]. Early identification and management of frailty are therefore crucial to achieving the objectives of the National Programme for Health Care of the Elderly (NPHCE), which emphasizes preventive and promotive health strategies for India’s ageing population.

Several frailty assessment tools exist, including the Groningen Frailty Indicator [

25], Edmonton Frail Scale [

26], Tilburg Frailty Indicator [

27], Kihon Checklist [

28] and FRAIL Scale [

29], each incorporating different aspects of geriatric evaluation in their design. However, many of these instruments have been criticized for not encompassing all essential domains of frailty, and for lacking cultural adaptability and psychometric robustness when applied to non-English-speaking populations. To address these gaps, [

15] developed the FAST scale with 14 items relevant for the Indian context, and added some novel components such as pain, the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test and multimorbidity. The scale was validated in Hindi and designed for ease of administration by trained healthcare workers. Building on this, the present study enhances the cultural and linguistic relevance of this FAST scale by validating its Bengali version, thereby extending its applicability for community-based programs to tertiary care frailty screening among older adults in Eastern India, where Bengali is the predominant language.

The Bengali version of FAST scale was validated among community dwelling older adults with a mean age of 64.27 ± 5.02 years, mostly aged 60–69 (82.9%). Majority were Hindu (98.2%), non-literate (61.3%), widow (47.5%) and belonged to the middle socio-economic class, with home makers, retired, and self-employed individuals forming the largest occupational groups.

The psychometric properties of the FAST Bengali version showed high internal consistency, where the total items had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.806; thereby confirming that the items reliably assessed the intended construct. The test–retest reliability showed significantly strong intra-rater (ICC = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.623–0.945, p < 0.001) and inter-rater reliability (ICC = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.507–0.927, p < 0.001), indicating that the tool provides stable and consistent results over time and assessors. According to established benchmarks, an ICC above 0.75 indicates good reliability, and above 0.80 indicates excellent reliability, supporting the instrument’s robustness in repeated measurements [

30]. Additionally, Cohen’s kappa coefficient indicated substantial agreement (κ = 0.602, p < 0.001) between the two raters, aligning with [

31] benchmarks, where values from 0.61 to 0.80 reflect substantial agreement. Overall, these results confirm that the instrument produces reliable and consistent results across different raters and over time.

The construct validity of the Bengali FAST was supported by the confirmatory factor analysis, demonstrated that the items were generally well-aligned with the latent construct of frailty. Most items exhibited strong and statistically significant factor loadings (p < 0.05), indicating that they reliably measured the underlying frailty construct. Notably, items related to “mood” (i.e., Q8a and Q8b) showed loading values above 0.9, suggesting that these items were particularly effective indicators of frailty in the target population. In contrast, items related to “medication and multimorbidity” (i.e., Q12 and Q11) loaded relatively lower indicating that these items are less strongly associated with the overall construct or that they capture more specific aspects of frailty not as central to the latent factor. The variability in threshold values further highlights that the items related to “nutrition” (Q2), “mobility” (Q4), and “functional status” (Q6) were endorsed at lower levels of frailty, whereas items like “physical performance” (Q9) and “medication” (Q11) were endorsed primarily at higher frailty levels. This spread suggests that the Bengali FAST is sensitive across a wide range of frailty severity, making it suitable for both early identification of pre-frailty and detection of more severe frailty. Overall, these findings provide strong evidence of the factorial validity of the Bengali FAST scale. The scale appears to be both conceptually coherent and psychometrically sound, supporting its use in clinical and community settings to assess frailty among Bengali-speaking older adults. research could further explore the predictive validity of the scale and examine whether the lower-loading items (Q11, Q12) could be revised or complemented to improve overall measurement precision.

Also, the psychometric evaluation of the Bengali FAST scale showed mostly good model fit and high reliability. The comparative fit index (CFI = 0.966), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI = 0.960) and CMIN/df ratio of 4.99 surpassed the recommended thresholds indicating strong comparative and incremental fit. However, the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR = 0.157) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.130, 95% CI: 0.118–0.143) exceeded typical cutoff values, suggesting a minor degree of model misfit that may be due to sample features or item-specific variation. Additionally, the tetrachoric correlation showed excellent internal consistency, with an ordinal alpha of 0.898 and a composite reliability of 0.942, both surpassing recommended thresholds. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE = 0.472) was just below the typical 0.50 cutoff, but acceptable convergent validity is indicated by the high factor loadings for most items. Overall, these results establish that the Bengali FAST has a solid psychometric structure, capable of capturing the multidimensional nature of frailty across physical, functional, and psychosocial domains.

In terms of criterion validity, the Bengali version of the FAST scale also showed good diagnostic accuracy compared to the Fried Frailty Scale, which served as the gold standard. The sensitivity of 0.810 indicates that the scale effectively identified most frail and pre-frail individuals, demonstrating its usefulness in screening environments. ROC curve analysis further confirmed the scale’s performance, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.843 (p = 0.002, 95% CI: 0.755–0.930), indicating strong overall discriminatory ability. These results suggest that the FAST Bengali version is a dependable and efficient tool for detecting frail and pre-frail conditions in older adults, suitable for both clinical and community assessments.

The results of the present study are not directly comparable with previous research findings due to its distinct objective of culturally adapting and validating the FAST scale specifically in the Bengali language for use among Bengali-speaking older adults. However, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The study sample was confined to two urban wards of Kolkata, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to rural populations or other sociocultural contexts. Moreover, the cross-sectional study design limits the ability to assess predictive validity; therefore, future longitudinal studies are recommended to evaluate whether FAST scores can predict adverse health outcomes, such as hospitalization, disability, and mortality. Further refinements to the scale may also be considered to improve item-level performance and model fit indices.

5. Conclusions

The present study established the Bengali version of the Frailty Assessment and Screening Test as a reliable and valid tool for assessing frailty among community-dwelling older adults in Kolkata, India. The brevity, multidimensional structure, and cultural adaptability of the tool make it suitable for use in both clinical and community settings. Incorporating the Bengali FAST into routine geriatric care can facilitate early detection and preventive actions, thereby further delaying disability and reducing healthcare costs. Addressing frailty not only cuts expenses but also improves quality of life, making it a crucial focus in India’s growing healthcare system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization I.S., A.T., B.K.R. and A.C.; methodology, A.G., I.S., P.D. and K.M.; formal analysis, A.G.; data curation, A.G., P.D. and K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G. and I.S.; writing—review and editing, P.D., K.M., S.D., P.G., A.T., B.K.R., A.S. and A.C.; supervision, I.S., S.D., P.G., B.K.R., A.S. and A.C; investigation, S.D., P.G., A.T., B.K.R., A.S. and A.C.; administrative, S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, grant number INTR-IG/ICAM/05/2023 dated 14/08/2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Institutional Ethics Committee approved the study (19th IEC/CAM/1.5 dated 03-12-2024), and the study was also registered in CTRI (CTRI/2025/01/079470).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data analysed during this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Arpita Santra and Samarpita Debnath for their expertise and assistance in the translation and cultural adaptation of the study tool. The authors also express sincere appreciation to the local resource persons for their cooperation during data collection and to all the study participants for their time, trust and invaluable contribution to this research. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Mental health of older adults. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults (accessed on 09 October 2025).

- Leng, S.; Chen, X.; Mao, G. Frailty syndrome: an overview. Clin Interv Aging, 2014, 433. [CrossRef]

- Clegg, A.; Young, J.; Iliffe, S.; Rikkert, M. O.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in elderly people. The Lancet, 2013, 381 (9868), 752–762. [CrossRef]

- Collard, R. M.; Boter, H.; Schoevers, R. A.; Oude Voshaar, R. C. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2012, 60 (8), 1487–1492. [CrossRef]

- Gill, T. M.; Gahbauer, E. A.; Han, L.; Allore, H. G. Trajectories of disability in the last year of life. New England Journal of Medicine, 2010, 362 (13), 1173–1180. [CrossRef]

- Saha, I.; Majumder, J.; Bagepally, B.; Das, S.; Kalita, M.; Devraja, M.; Das, D.; Ghosh, A.; Ghosh, P.; Talukdar, A.; Ray, B.K.; Saha, A.; Chakrabarti, A. Burden and determinants of frailty among older adults (≥60 years) in india: a systematic review & meta-analysis. Aging Medicine and Healthcare, 2025, accepted.

- Yu, R.; Tong, C.; Ho, F.; Woo, J. Effects of a multicomponent frailty prevention program in prefrail community-dwelling older persons: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2020, 21 (2), 294.e1-294.e10. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Liu, M.Y.; Chen, N.F. Frailty prevention care management program (fpcmp) on frailty and health function in community-dwelling older adults: a quasi-experimental trial protocol. Healthcare, 2023, 11 (24), 3188. [CrossRef]

- Serra-Prat, M.; Sist, X.; Domenich, R.; Jurado, L.; Saiz, A.; Roces, A.; Palomera, E.; Tarradelles, M.; Papiol, M. Effectiveness of an intervention to prevent frailty in pre-frail community-dwelling older people consulting in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, S. H.-F.; Travers, J.; Shé, É. N.; Bailey, J.; Romero-Ortuno, R.; Keyes, M.; O’Shea, D.; Cooney, M. T. Primary care interventions to address physical frailty among community-dwelling adults aged 60 years or older: a meta-analysis. PLoS One, 2020, 15 (2), e0228821. [CrossRef]

- Das, S. Cognitive frailty among community-dwelling rural elderly population of west bengal in india. Asian J Psychiatr, 2022, 70, 103025. [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, J.; Marzilli, C.; Aungsuroch, Y. Establishing appropriate sample size for developing and validating a questionnaire in nursing research. Belitung Nurs J, 2021, 7 (5), 356.

- White, M. Sample size in quantitative instrument validation studies: a systematic review of articles published in scopus, 2021. Heliyon, 2022, 8 (12), e12223. [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.; Royse, C. F.; Terkawi, A. S. Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia. Medknow Publications May 1, 2017, pp S80–S89. [CrossRef]

- De, K.; Banerjee, J.; Rajan, S. P.; Chatterjee, P.; Chakrawarty, A.; Khan, M. A.; Singh, V.; Dey, A. B. Development and psychometric validation of a new scale for assessment and screening of frailty among older indians. Clin Interv Aging, 2021, Volume 16, 537–547. [CrossRef]

- Fried, L. P.; Tangen, C. M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A. B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W. J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2001, 56 (3), M146–M157. [CrossRef]

- Le Pogam, M.-A.; Seematter-Bagnoud, L.; Niemi, T.; Assouline, D.; Gross, N.; Tr€, B.; Rousson, V.; Peytremann-Bridevaux, I.; Burnand, B.; Santos-Eggimann, B. Development and validation of a knowledge-based score to predict fried’s frailty phenotype across multiple settings using one-year hospital discharge data: the electronic frailty score. EClinicalMedicine, 2022, 44, 101260. [CrossRef]

- Abarca-Gómez, L.; Abdeen, Z. A.; Hamid, Z. A.; Abu-Rmeileh, N. M.; Acosta-Cazares, B.; Acuin, C.; Adams, R. J.; Aekplakorn, W.; Afsana, K.; Aguilar-Salinas, C. A.; et al. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. The Lancet, 2017, 390 (10113), 2627–2642. [CrossRef]

- Saha, I.; Paul, B. Essentials of Biostatistics & Research Methodology, 4th ed.; Academic Publishers: Kolkata, 2023.

- Koo, T. K.; Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med, 2016, 15 (2), 155–163. [CrossRef]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R; Springer: Springer Science+Business Media, 2017.

- Hair, J. F.; Black, W. C.; Babin, B. J.; Anderson, R. E.; Tatham, R. L. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson Education, 2009.

- Ashley, L.; Smith, A. B.; Keding, A.; Jones, H.; Velikova, G.; Wright, P. Psychometric evaluation of the revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R) in cancer patients: confirmatory factor analysis and rasch analysis. J Psychosom Res, 2013, 75 (6), 556–562. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, H.; Aleem, S. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Psychometric Validation of Healthy Lifestyle and Personal Control Questionnaire (HLPCQ) in India. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 2023, 48 (3), 430–435. [CrossRef]

- Steverink, N. Measuring Frailty: Developing and testing the GFI (Groningen Frailty Indicator). Gerontologist, 2001, 41, 236.

- Rolfson, D. B.; Majumdar, S. R.; Tsuyuki, R. T.; Tahir, A.; Rockwood, K. Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age Ageing, 2006, 35 (5), 526–529. [CrossRef]

- Gobbens, R. J. J.; van Assen, M. A. L. M.; Luijkx, K. G.; Wijnen-Sponselee, M. Th.; Schols, J. M. G. A. The Tilburg Frailty Indicator: psychometric properties. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2010, 11 (5), 344–355. [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, M.; Yabushita, N.; Kim, M.; Matsuo, T.; Seino, S.; Tanaka, K. Assessment of vulnerable older adults’ physical function according to the Japanese Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI) System and Fried’s Criteria for Frailty Syndrome. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 2012, 55 (2), 385–391. [CrossRef]

- Morley, J. E.; Malmstrom, T. K.; Miller, D. K. A Simple Frailty Questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging, 2012, 16 (7), 601–608. [CrossRef]

- Koo, T. K.; Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med, 2016, 15 (2), 155–163. [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.; Koch, G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 1977, 33 (1), 159–174.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).